‘Annotations on the Book of Zambasta, I’, in Literarische Stoffe und ihre Gestaltung in...

Transcript of ‘Annotations on the Book of Zambasta, I’, in Literarische Stoffe und ihre Gestaltung in...

BEITRÄGE ZUR IRANISTIKGegründet von Georges Redard, herausgegeben von Nicholas Sims-Williams

Band 31

Literarische Stoffe und ihre Gestaltung in mitteliranischer Zeit

Herausgegeben von

Desmond Durkin-Meisterernst, Christiane Reck und Dieter Weber

WIESBADEN 2009DR. LUDWIG REICHERT VERLAG

Literarische Stoffe und ihre Gestaltung

in mitteliranischer Zeit

Kolloquium anlässlich des 70. Geburtstages von Werner Sundermann

Herausgegeben von

Desmond Durkin-Meisterernst, Christiane Reck und Dieter Weber

WIESBADEN 2009DR. LUDWIG REICHERT VERLAG

Bibliografische Information der Deutschen NationalbibliothekDie Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind

im Internet über http://dnb.ddb.de abrufbar.

© 2009 Dr. Ludwig Reichert Verlag WiesbadenISBN: 978-3-89500-671-5

www.reichert-verlag.de

Das Werk einschließlich aller seiner Teile ist urheberrechtlich geschützt.Jede Verwertung außerhalb der engen Grenzen des Urheberrechtsgesetzes ist ohne

Zustimmung des Verlages unzulässig und strafbar.Das gilt insbesondere für Vervielfältigungen, Übersetzungen, Mikroverfilmungen

und die Speicherung und Verarbeitung in elektronischen Systemen.Gedruckt auf säurefreiem Papier (alterungsbeständig pH7 –, neutral)

Printed in Germany

Förderung der Tagung und die Drucklegung des Tagungsbandes

durch die Fritz Thyssen Stiftung

Veranstaltung der Tagung:Berlin-Brandenburgische Akademie der Wissenschaften

VII

Inhalt Seiten

Peter Zieme

Laudatio . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1

François de Blois

On the sources of the Barlaam Romance, or

How the Buddha became a Christian saint . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7

Iris Colditz

„Autorthema“, Selbstproklamation und Ich-Form

in der alt- und mitteliranischen Literatur . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 27

Desmond Durkin-Meisterernst

The literary form of the Vessantaraj¡taka in Sogdian . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 65

With an appendix by Elio Provasi: The names of the prince . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 80

Philippe Gignoux

Les relations interlinguistiques de quelques termes de la pharmacopée antique . . . . . 91

Almuth Hintze

The Return of the Fravashis in the Avestan Calendar . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 99

Manfred Hutter

Das so genannte Pandn¡mag £ Zardušt: Eine zoroastrische Auseinandersetzung

mit gnostisch-manichäischem Traditionsgut? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 123

Maria Macuch

Gelehrte Frauen – ein ungewöhnliches Motiv in der Pahlavi-Literatur . . . . . . . . . 135

Mauro Maggi

Annotations on the Book of Zambasta, I . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 153

Enrico Morano

Sogdian Tales in Manichaean Script . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 173

Antonio Panaino

Ahreman and Narcissus . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 201

Christiane Reck

Soghdische manichäische Parabeln in soghdischer Schrift

mit zwei Beispielen: Parabeln mit Hasen . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 211

Kurt Rudolph

Literarische Formen der mandäischen Überlieferung . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 225

VIII

Shaul Shaked

Spells and incantations between Iranian and Aramaic . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 233

Nicholas Sims-Williams

The Bactrian fragment in Manichaean script (M 1224) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 245

Prods Oktor Skjærvø

Reflexes of Iranian oral traditions in Manichean literature . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 269

Alois van Tongerloo

A Nobleman in Trouble, or the consequences of drunkenness . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 287

Dieter Weber

Ein Pahlavi-Fragment des Alexanderromans aus Ägypten? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 307

Jens Wilkens

Ein manichäischer Alptraum? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 319

Yutaka Yoshida

The Karabalgasun Inscription and the Khotanese documents . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 349

Stefan Zimmer

Vom Kaukasus bis Irland — iranisch-keltische Literaturbeziehungen? . . . . . . . . . . 363

TAFELN

1 E (1933–1936); Konow 1934 and 1939; Bailey 1937; Emmerick 1968a. If not otherwise indicated, I quotethe text of Z according to Emmerick's edition.

2 Skazanie (1965).

3 M. Leumann in E 385–530; Emmerick 1966, 1967 and 1969.

4 KT 6 with the review article by Emmerick 1969.

5 SGS.

6 See Maggi 2004b.

Annotations on the Book of Zambasta, I

Mauro Maggi, Napoli

Of the literary works written in the Khotanese language, the Book of Zambasta (Z) is one of

the most important and it is presumably the most widely known among Iranian and Buddhist

scholars. This is due to a number of reasons: it is written in Old Khotanese, a variety of the

language that is less ambiguous and more readily understood than the later stages of the

language; it is the longest Khotanese poem and is comparatively well preserved; it is an original

Khotanese composition; it has a long research tradition that goes from Ernst Leumann’s editio

princeps with German translation, continuing with Sten Konow’s and Harold W. Bailey’s

detailed review articles, to Ronald E. Emmerick’s authoritative and easy-to-use edition with

English translation;1 it is available in a virtually complete facsimile edition of the main

manuscript (Z1);2 lastly, it can be read with the help of complete, though partly outdated,

glossaries,3 as well as Bailey’s extensive treatment of the most difŸcult items of the vocabulary4

and Emmerick’s accurate, though not comprehensive, grammar.5

The importance of Z is made even greater by the age of the work: one folio from a variant

manuscript was copied in the Ÿfth or early sixth century (T III S 16 = bi 33 of the Berlin-

Brandenburgische Akademie der Wissenschaften) and shows that Z was composed no later

than the Ÿfth century and presumably marked the beginnings of Khotanese Buddhist literature.

Other peculiarities of the text — particularly its literary structure as a concentric composition,

traces of a tradition of some of its sources in Kharo™Þh£ script and the layout of its manuscripts

in columns re ecting the metrical divisions — point to an early date of composition.6 It may

be added that an early composition date of Z is also in agreement with its author’s need to

insist polemically on the excellency of the Mah¡y¡na over ancient Buddhism, the so-called

154 Mauro Maggi

7 Emmerick 1968b and SGS.

8 Nattier 1990 and 1991.

9 Degener 1989b.

H£nay¡na, which locates the work in a period that is comparatively near to the origin of the

Mah¡y¡na and its early diffusion in Central Asia.

As for the speciŸc importance of Z for our knowledge of the Khotanese language, this was

stressed in the 1960’s by Ronald Emmerick who, on account of the considerable length of this

Old Khotanese text, produced his masterful edition and translation and used it as a basis for

his studies on the grammar and metrics of Khotanese.7 On the other hand, Z is not the ideal

basis for our knowledge of the Khotanese vocabulary for the simple reason that it is an original

composition and not a translation. Although the author of Z conceived some parts of the work

as translations, other parts appear in reality to be fairly free recastings of Indian sources and

independent compositions, so that most of the work lacks real parallels in other languages and

this at times makes interpretation difŸcult and risky. Thus, progress in the way of a reŸned

interpretation and, in the end, of an improved knowledge of the language of Z can be expected

not so much from efforts on the philological side as from the identiŸcation of more or less

precise parallels to passages of the text and from a detailed analysis of its contents from the

viewpoint of Buddhist studies.

Unfortunately, in the forty years or so that have elapsed since Emmerick’s edition and

translation, Z has been largely ignored by Buddhist scholars, notwithstanding the apparent

signiŸcance of the text for Buddhist studies. The most remarkable exceptions are an article by

Jan Nattier on the translations of Buddhist texts into Central Asian vernaculars, where she

also comments on the well-known opening of Z 23 concerning the reception of Khotanese

translations of Buddhist texts, and her book on the prophecies of decline of the Buddhist

Doctrine, particularly the section on the tradition of the Candragarbhas¥tra in Buddhist

literatures, where she systematically takes into consideration, on the basis of Emmerick’s

translation, the Khotanese adaptation of the Candragarbhas¥tra in Z 24.8

On the other hand, some improvements on Emmerick’s translation have been made

possible by a better understanding of the doctrinal contents of some passages and by the

identiŸcation of parallel passages in other languages. One may refer, for instance, to Almuth

Degener’s reinterpretation, in the light of other Khotanese Buddhist texts and of the

Lank¡vat¡ras¥tra, of Z 4.103–104, that deals with the reŸnement of the tath¡gata-garbha, the

‘Buddha-germ’.9 More recently, Duan Qing identiŸed a Chinese version of the Maitr£-

bh¡van¡prakara÷a as a complete parallel to chap. 3 of Z and reinterpreted some passages in this

155Annotations on the Book of Zambasta, I

10 Duan 2007.

11 Maggi 2006.

12 Maggi 2004a.

13 Skazanie 126.

14 SDTV 6.79–80.

15 E 350–351.

chapter.10 Of course, improved readings and translations, mainly from a philological point of

view, have also been suggested occasionally by Almuth Degener, Hiroshi Kumamoto,

Nicholas Sims-Williams, Prods O. Skjærvø and myself. It is apparent that detailed study of

Z will allow a still better understanding of the text and its language. In particular, Degener’s

and Duan’s contributions from the standpoint of Buddhist studies as well as my recent

identiŸcation of N¡g¡rjuna’s quotation in Z 11.32 as Bodhisa¿bh¡ra 7 (TaishÚ 1660, vol. 32,

pp. 519b 21–22)11 are clear examples of the work which must still be carried out systematically

on Z, in order to identify its sources or at least recognise parallel passages in other Buddhist

literatures: this would ultimately contribute to a better understanding of the history of

Buddhism in Khotan and its diffusion outside of India.

A couple of years ago I translated into Italian a selection of Z (chapters 1–2, 5, 13–14 and

24) for an extensive anthology of Buddhist texts, and the opportunity to read afresh some

chapters of Z enabled me to introduce a number of reinterpretations.12 Because it is not

unlikely that they may escape the attention of colleagues who do not read Italian — all the more

so because my translation appeared in a publication aimed at the general readership, not in a

scholarly one —, I would like to present here a Ÿrst batch of annotations.

Z 1.44

The beginning of the verse can be restored as [nama]s£mä harbä››ä balysa ‘I worship all the

Buddhas’ (cf. Z 10.1, 11.62, 13.1, 14.1 and 23.1). A trace of the vowel diacritic -£ is still visible

in the facsimile.13 In the lacuna there is room for two more ak™aras that must have belonged

to the preceding lost hemistich.

Z 1.80–81

In his re-edition of the fragmentary f. 150 of Z1 (= Or 9614/4),14 Skjærvø reads, between two

lacunae, Z 1.80 ha¿tsa h£ñe jsa pva’ (r2) instead of Leumann’s ha¿tsa h£ñe jsa nva’ ‘… mitsamt

dem Heere …’15 and Emmerick’s ha¿tsa h£ñe jsa tva’ ‘… with the army …’. The new,

improved reading allows the easy restoration ha¿tsa h£ñe jsa pva’[stä] ‘… frightened with his

156 Mauro Maggi

16 Cf. Maggi 2005, 19.

17 In SGS 298 he has “hvanau ‘speech’ Z 1.189”.

18 Similarly in Dict. 501 s.v. hvatana-.

19 For the language adverb cf. Si [13.41] 103r3 KT 1.38 hva¿no and P 2786.248 KT 2.101 hva÷au. As pointedout by Degener 1989a, 121–122, hva¿n£ in P 2782.44 KT 3.60 hva¿n£ hauna ‘in Khotan speech’ (Bailey)

is from the newly created LKh. stem hva¿nia-.

army’, a reference to M¡ra and his army of demons who, frightened of the morality and

imperturbability of the Buddha, took ight at his awakening.16

Skjærvø also provides the new reading Z 1.81a ]™™¡ yäðe aysmya by¡ta — that can be

translated ‘. . . recalled to the mind’ — instead of Leumann’s ] ™™a yäðe aysmya h¥na ‘. . . hat

er gemacht im Geiste Träume’ and Emmerick’s ] ™™u yäðe aysmya by¡na ‘. . . made reins on

the mind’.

Z 1.189

Towards the end of chap. 1 we read:

1.189 cu aysu tt¥ hvanau by¥ttaimä kye käðe batä bv¡mata d£ra

bi››ä gyasta balysa k™amev£—mä cu mara bvatemä arthu

‘Since I have translated this into Khotanese, however extremely small (and) poor my

knowledge, I seek pardon from all the Lord Buddhas for whatever meaning I have distorted

here’ (Emmerick).

Emmerick’s translation is at variance with the one by Leumann, who understood — I think

correctly — the word hvanau as ‘LehrstoÙe [teaching]’ (E 4). The equation of Z 23.372

hvatänau by¥ttaimä ‘I translated into Khotanese’ with Z 1.189 hvanau by¥ttaimä, that was

adopted by Emmerick in his translation — but not in his SGS —,17 had already been introduced

by Bailey in KT 6.432: “A comparison of 1189 cu aysu tt¥ hvanau by¥ttaimä with 23372 cu aysu

tt¥ hvatänau by¥ttaimä shows that hvanau is here into the Hvatana language”.18 Such an

equation presupposes that hvanau in v. 189 is a Late Khotanese spelling for Old Khotanese

hvatänau ‘in Khotanese language’, an adverb formed with the language sufŸx -au from the

adjective hvatana- ‘Khotanese’. The development of the adjective from Old to Late Khotanese

is as follows: OKh. hvatana- > OKh. hvatäna- > LKh. hva¿na- > LKh. hvana-, the short form

without anusv¡ra occurring only in the latest stages of the language.19 In principle, the

occurrence of a Late Khotanese form in Z is not impossible because the main manuscript of

Z, that was copied by speakers of Late Khotanese in the seventh century, occasionally contains

spellings that reveal Late Khotanese in uence. However, it is surprising to Ÿnd here the very

late spelling hvana- without anusv¡ra. For ‘Khotanese’ Z has elsewhere only the Old Khotanese

157Annotations on the Book of Zambasta, I

20 hvatana-/hvatäna-: Z 5.19 (2×), 5.114, 15.9, 23.2, 23.4 (3×), 23.6, 23.372.

21 hvanau/hvano: Z 1.188, 1.189, 5.6, 5.8, 5.l13, 15.133, 22.334, 23.2. Cf. Dict. 503 s. v. hvanaa- where

bilingual evidence is also given.

22 1 light syllable; 3 pretonic unaccented heavy syllable counting as a light syllable (see E xxxiii–xxxiv); 2 heavy

syllable; 4 stressed heavy syllable; a comma separates feet within a cadence; | caesura; || p¡da boundary.

spellings hvatana- and hvatäna- for a total of ten occurrences,20 whereas hvanau and the variant

spelling hvano occur eight times and always as the acc. sg. of the substantive hvanaa- ‘speech,

preaching’, as the contexts clearly show.21 There is in reality no compelling reason for

assuming, only in this passage, a Late Khotanese spelling that never occurs elsewhere in Z, so

that Leumann’s interpretation should be kept in this case. In actual fact, careful comparison

of the two verses containing the clauses that were equated by Bailey shows that they are

metrically different. In particular, the Ÿrst p¡da of Z 1.189 has a regular internal cadence of

seven morae, while the Ÿrst p¡da of Z 23.372 has a long internal cadence of nine morae, which

is comparatively common and is compensated, in the second p¡da, by a shorter opening of

three instead of Ÿve morae. In both verses, the total number of morae is thus twenty-four:22

5 morae 7 morae 5 morae 7 morae = 24 morae

1 1 1 2 | 1 2 3, 2 1 || 1 1 1 1 1 | 4 1 1, 4 1

1.189 cu aysu tt¥ hvanau by¥ttaimä kye käðe batä bv¡mata d£ra

‘Since I have translated this teaching (hvanau), however extremely small (and) poor my

knowledge, . . .’ (after Emmerick with modiŸcations);

5 morae 9 morae 3 morae 7 morae = 24 morae

1 1 1 2 | 1 1 2, 2 2 1 || 1 1 1 | 4 1 1, 4 1

23.372 cu aysu tt¥ hvatänau by¥ttai—mä ava››ä balysä häm¡ne

‘Since I have translated this into Khotanese (hvatänau), may I surely become a Buddha

(Emmerick)’.

It should be noted that the same metrical pattern of v. 1.189 with hvanau ‘teaching’ is also

found in two similar verses, that employ alternatively the metrically equivalent synonyms dh¡tu

‘law, doctrine’ (21) and hvanau ‘teaching’ (12), both counting three morae:

2.244 cu aysu tt¥ dh¡tu hvatai—mä param¡rthä s¥ttryau ›¥stä

‘Since I have proclaimed this Law, the supreme meaning, furnished with s¥tras …’

(Emmerick);

5.l13 cu aysu tt¥ hvanau hvatai—mä ttyau puñyau ava››ä ma d¡ru

‘Since I have told this story, through these merits may I surely before long …’ (Emmerick).

158 Mauro Maggi

23 Emmerick 1990, 101.

24 Emmerick in Sander 1988, 536.

25 See Falk 2000.

26 E 8–9.

Z 1, colophon

Emmerick’s Ÿrst translation of the Late Khotanese colophon of chap. 1 ¡›ä’r£ puñabhadrrä

byaude mai jve h¡ysa bar£ ba’ysä p¥ryau ™i’nau ‘The �c¡rya Pu÷yabhadra has received (this).

May it not be far from him while alive. May it bring the Buddha’s favour, (my) sons’ was

retouched by him on two occasions to obtain: ‘The �c¡rya Pu÷yabhadra has received (this).

May no one take it far from him!23 (It is) the Buddha’s favour, (my) sons’.24 This colophon

displays, thus, a protective formula comparable to those found in Sanskritised G¡ndh¡r£

inscriptions on private Buddhist monastic implements, e.g. na kenaci hartthavya¾ (= Sanskrit

na kenacid dhartavya¾) ‘It must not be taken away by anyone!’.25

However, the interpretation of the colophon can be further improved. In ba’ysä p¥ryau

™i’nau, it is more natural to understand ba’ysä as a speciŸcation of the immediately following

voc. pl. p¥ryau ‘sons of the Buddha (i.e. monks)’ rather than of ™i’nau ‘the Buddha’s favour’

(OKh. ™™änauma-). On the other hand, here ™i’nau is most likely short for ™i’nau yan- mid. ‘to

ask a favour’ (cf. Iledong 026a3 SDTV 6.566 vaña ¡¿ tt¡ ™i÷au yani ‘now I am asking a favour

of you’) and is used as a polite form of request, i.e. ‘please!’ (cf. German bitte, Italian prego).

Accordingly, the last part of the colophon is better translated ‘May no one take it far from him,

sons of the Buddha, please!’ and gives us a glimpse of the everyday life in a Khotanese

monastery.

Z 2.15

As was already suggested by Leumann,26 the second hemistich can be fairly safely restored as

ku samu pharu karya u st¡ma [ne ju ye par›tä dukhyau jsa] ‘in which there is merely much effort

and exertion, (and yet) one does not escape from woes’ (cf. Z 24.173 ku samu pharu st¡ma ne

ju ye par›tä dukhyau jsa).

Z 2.75, 77, 4.18 and 56

The Old Khotanese word t¬™÷a- occurs four times in Z only. The Ÿrst two occurrences (Z 2.75

and 77) are found in a passage where the Buddha explains the miracles which a Buddha can

accomplish:

159Annotations on the Book of Zambasta, I

27 On the three kinds of miracles of the Buddha see BHSD 392 s.v. pr¡tih¡rya.

28 E 16: ‘durstig (regsam)’; Emmerick 1968a, 22. Bailey rendered t¬™÷a-indryau jsa (sic) ‘with the thirsty-sensed’

(KT 6.169–170 s.v. parvacha) and ‘with those of the desire-faculty’ (Dict. 220 s.v. parvac-).

29 See CDIAL 339 s.vv. and CDIALAdd 49 s.v. t¬™÷aka-.

30 See e.g. Sanghabhedavastu 1.129 (reference from Francesco Sferra) and Mah¡vyutpatti 1257–1259 forSanskrit, and Nettippakara÷a 63 (ed. 99–102) and Visuddhimagga 23.55 (ed. 611) for P¡li with majjhindriya-

and majjhimindriya- respectively (references from Claudio Cicuzza). See also BHSD 254 s.v. t£k™nendriya,SWTF 2.377 s.v. t£k™nendriya-, and PED 301 s.v. tikkha- and 537 s.v. mudu-.

31 Degener 1987, 49, and 1989a, 272 s.v. ttraik™yera-. A similar classiŸcation, but apparently in a social sense,is found in Late Khotanese texts: P 2787.65 KT 2.103 ›aryai d£ryai my¡n£ ysama›adai ‘good, bad, middlepeople’; JS 3r4 (8) ›ira d£ra my¼nya … hv¼÷ðä ‘the good, the low, the middle men’; and JS 36v3 ›ere d£re

my¼n¡ ‘the good, the low, the middle (beings)’.

… drraya p¡rh¡liya balysi . 3

2.74 kye mä ttä vainaiy¡ aniru—ddha kye stura bv¡mata mulysga

idryau jsa nv¡ta u murkha irdi-pr¡h¡l£ tt¡nu 74

2.75 kye my¡n¡-indryiya hva’ndä ttä mamä grati £ñi prayseindi

t¬™÷a indryau jsa ut¡ra parvacha ni bv¡mata rräsca 5

2.76 d¡tu gga¿bh£ru pyuv¡’re hu-hvatu käðe rra™Þu agga¿jsu

tt¡nu vara hämäte prays¡—tu balys¡nu ››¡›anu v£ri 6

2.77 bad¬ käðe indriya t¬™÷a tr¡mu bi››ä ™™¡v¡ rraysgu

‘(73) . . . Three are the Buddha’s miracles. (74) For those who are to be my pupils, Aniruddha,

whose understanding is thick, small, who are restricted and simple in senses, there is the

miracle due to supernatual powers. (75) Those who are men of middling senses believe on

account of my instruction. As for the t¬™÷a- in senses, noble, mature is their understanding,

sharp. (76) They hear the profound Law, well-spoken, very true, faultless. In them arises

thereat belief in the teaching of the Buddha. (77) Bhadra’s senses are very t¬™÷a-. He will

quickly surpass in every way today all the Hearers …’ (after Emmerick with modiŸcations).27

Leumann and Emmerick translated t¬™÷a- as ‘thirsty’28 as if it went back to an unattested

Sanskrit *t¬™÷a- to be connected to Skt. t¬™÷¡- ‘thirst’ and its derivative t¬™÷aka- ‘desirous, eager

for’ recorded only in lexicographical works but continued in New Indo-Aryan languages.29

However, a translation ‘thirsty’ raises semantical difŸculties because a thirsty mind is in

principle a negative attitude from a Buddhist point of view. In reality, various Buddhist texts

classify living beings into beings ‘of dull senses’ (Skt. m¬dvindriya-, P¡li mudindriya-), beings

‘of middling senses’ (Skt. madhyendriya-, P¡. majjh(im)indriya-) and beings ‘of sharp senses’

(Skt. t£k™nendriya-, P¡. tikkhindriya-).30 There can scarcely be any doubt that Kh. t¬™÷a indryau

jsa in the passage under consideration corresponds to Skt. t£k™÷endriya- ‘sharp in senses’, as

Almuth Degener suggested.31 The development -k™÷- > -™÷- with simpliŸcation of the

160 Mauro Maggi

32 See SWTF 2.118–119.

33 Degener 1989a, 272 s.v. ttraik™yera-.

34 CDIAL 332 s.v. t£k™÷á-.

35 Ed. Bacot 1930, 51; see Bailey 1946, 769, and in CDIAL 332 s.v. t£k™÷á-.

36 Brekke 2000, 57; omitted by the editor in his translation on p. 61.

37 Bailey 1946, 768 (‘harsh, sharp, grievous’); CDIAL 333 s.v. t£k™÷á-. Cf. the three P¡li outcomes with partially

different senses: tikkha- ‘sharp, clever, acute, quick (only Ÿg. of the mind)’; tikhi÷a- ‘pointed, sharp, pungent,acrid’; and ti÷ha- ‘sharp (of swords, axes, knives, etc.)’ (PED 301–302).

38 CDIAL 333 s.v. t£k™÷á-. See also Fussmann 1972, 48–49 (with an addendum on p. 440) and 58–59.

39 CDIALAdd 48 s.v. t£k™÷á-.

40 Bailey 1946, 768–769; see also Dresden 1955, 475 s.vv. ttrik™a- and ttrikha-, and cf. KT 6.107–108 s.v.

tt¬¿khe.

consonant cluster by loss of the occlusive is paralleled in Z by e.g. 13.16 k¬sn¡yana- from Skt.

k¬tsn¡yatana- ‘domain of completeness’32 with -tsn- > -sn-.

It must be noted that Kh. t¬™÷a- does not go back directly to Skt. t£k™÷a- ‘sharp, acute’ but

to its allotrope tr£k™÷a- with -r- in the Ÿrst syllable,33 a con ation of t£k™÷a- and t¬™Þa- ‘rough,

harsh, rugged’.34 Skt. tr£k™÷a- occurs in the Tibetan-Sanskrit dictionary by Tshe ring Dbang

rgyal, where it is equated with Tib. rno byed ‘sharpened’ (f. 98a3),35 and is re ected in the

languages of Northwest India. For Middle Indo-Aryan we have Buddhist Sanskrit tri÷ha

‘clever’ in a manuscript of the Ca¿g£s¥tra from Gandh¡ra now kept in the Schøyen collection

(SC 2376/1/3r1)36 and presumably G¡ndh¡r£ tri(¿)k™a- ‘hard, difŸcult (?)’ in a document from

Niya.37 For New Indo-Aryan, the following outcomes are recorded: Tir¡h£ tr£Ðna ‘sharp’,

Bashkar£k lich ‘bitter’, Kashmiri tricher m. ‘sharpness’ (and tr(y)ukhu ‘acute, clever’ – non-

Dardic Indo-Aryan), Lahnd¡ trikkh¡ ‘sharp, quick’, Dogr£ dialect of Panj¡b£ trikkhan¡

‘pungent’38 and KoÞgarh£ dialect of West Pah¡r£ tríkkh÷ø ‘to taste (esp. something pungent)’.39

As well as in Kh. t¬™÷a-, Middle Indo-Aryan outcomes of Skt. tr£k™÷a- are also re ected in

Kh. ttri¿k™a- ‘harsh, cruel, sharp’ and t¬¿kha- ‘peak’.40

The interpretation of Kh. t¬™÷a- as ‘sharp, acute’ also Ÿts the other two occurrences of the

word in Z:

4.18 ™a v¡ parikalpa cu härä k™a—mäte u ne ju hämäte ne n¡—

ju ku nai v£v¡tä u nai a—ysmya ››au-n¥hä ¡tä tt¬™÷ä 18

4.19 kho ju dukhäte nyanau kei’tä o ttarrai ¥tco puv¡vo

o bin¡sai hve’ kh¡ysu o mara÷i ysä™Þä ye hv¼’ndä

‘(18) Or this is false assumption: if a thing pleases and it is not to be got hold of when one has

no maturation (of actions entailing it) and is not concentrated, sharp (tt¬™÷ä) in one’s mind,

161Annotations on the Book of Zambasta, I

41 My translation of Z 4.18ab, where I regard n¡ju as a present inŸnitive (cf. SGS 218 for the ending -u), is inline with Bailey’s (KT 6.130 s.v. n¡ju) rather than Emmerick's. The correct translation of Z 4.18cd was putforward by Degener 1987, 49, while Emmerick, Studies 3.143 s.v. ›ä-nauhya-, kept the translation ‘thirsty’for tt¬™÷ä, thus improving only in part on his earlier translation. I divide Z 4.19d ysä™Þä ye instead of ysä™Þäyeas Leumann, Emmerick and Bailey (KT 6.294 s.v. ysä™Þä).

42 I take Z 4.56c ni as 1 pl. enclitic pronoun, not as the negation ‘not’ as Emmerick.

43 KT 6.43 s.v. ka›ta.

44 KT 6.10 s.v. ahäna.

45 Dict. 57 s.v. kas-.

46 See Hitch 1990, 182–183.

(19) as when a poor man thinks about treasure or one thirsty about cool water or a hungry man

about food or someone about the death of a hated man’;41

4.55 karma-v£v¡täna hv¼’ndi o gyasta pr£yo bh¥ta .

ttr¡mu samu daindi mah¡rbh¥—ta hävya tt£y£ daiyä 5

4.56 tt¡r¡÷u aysm¥ tt¬™÷ä cu m¡ parikalpäte r¥vä

o ttaura tt£nu ni ts£ndä bi››e nuva’ys¡re vikalpe 6

‘(55) According to the maturation of (their) actions, so only do men or gods, ghosts or spirits

see the great elements. Then one sees one’s own. (56) The mind of those (gods, ghosts and

spirits) is sharp (ttª֊) when it assumes our forms or they go through our walls. All

discriminations stream forth (after Emmerick with modiŸcations).42

See also below on Z 14.74.

Z 2.120

2.120 b¡tä ahäna ka›ta hämäte v¡tä bi››ä

‘the wind, on attachment by a noose, can all be held’ (Emmerick).

In the translation of the problematic hapax legomenon ka›ta ‘on attachment’, Emmerick

followed Bailey, who compared the Khotanese passage with Lalitavistara 21.172 (ed. 245)

›akyo v¡yu¾ p¡›air baddhu¿ ‘the wind can be bound with nooses’ and, chiefly on etymological

grounds, regarded ka›ta as “inst sg to ka™Þi- attaching” from an OIr. root *kas- ‘to attach’: ‘the

wind after capture with a noose can be wholly held’.43 Notwithstanding his analysis as instr.-

abl. sg., Bailey also translated ka›ta as a past participle: ‘wind is caught by a noose, it is all

held’.44 Later he suggested seeing in ka›ta a “noun loc. sing.” but again translated it as a past

participle: ‘can all the wind, being caught in a noose, be held?’.45 Bailey’s suggestions are not

convincing: ka›ta cannot be inst.-abl. sg. (-ie/-iä (jsa)) or loc. sg. (-ia) of *ka™Þi- because one

would expect the cluster -™Þ- to absorb palatalisation, not to be palatalised to -›t-;46 nor can it

162 Mauro Maggi

47 See Degener 1989a, 219.

48 Konow 1934, 55, and 1939, 73.

49 Degener 1989, 320–322, esp. § 55.4.

50 Translation by Masefield 1994, 77.

be a past participle from *kas- since one would expect *ka™Þa-, as was clear to Bailey himself.

In fact, no past participle can end in °›ta-.47

I wonder whether it is at all possible to Ÿnd an Iranian etymology of ka›ta-: I would be

tempted, in view of the similarity of the letters t and n and of their occasional interchange in

the manuscripts, to regard ka›ta as a copying mistake for *ka›na ‘by a bridle’, instr.-abl. of a

loanword *ka››a- from Skt. ka›a- ‘whip, thong’. Such an emendation would give the translation

‘the wind can all be held by a noose, a thong’. However, since the suggested emendation is

almost as risky as Bailey’s etymological interpretation and could only be conŸrmed by new

manuscript evidence, it is presumably wiser to suspend judgment.

Z 2.138, 200, 24.649

The phrase Z 2.138, 200, 24.649 ys£ra ho was translated ‘harsh words’ by Bailey. In principle,

he followed the translation ‘den rauhen Antrieb (Z 2.138), heftigen Wortschwall (Z 24.649)’

offered by Leumann who regarded ys£ra-ho as acc. sg. of a compound. Emmerick, on the other

hand, preferred to follow the interpretation by Konow who read ys£raho as one word derived

from ys£ra- ‘rough, harsh’ with the sufŸx -h¡- and meaning ‘roughness, harshness’.48 In her

work on the Khotanese sufŸxes, Almuth Degener pointed out that the rare sufŸx -h¡- is found

with certainty only in three Indian loanwords and preferred Bailey’s interpretation.49 That

Leumann and Bailey were right is conŸrmed by a passage in P¡li that I have been able to

identify in the Ÿnal verses of Ud¡na 4.8:

tudanti v¡c¡ya jan¡ asaññat¡ |

sarehi sang¡magata¿va kuñjara¿ ||

sutv¡na v¡kya¿ pharusa¿ ud£rita¿ |

adhiv¡saye bhikkhu aduÞÞhacitto ||

‘Folk who are uncontrolled goad (others) with speech as is the battle-gone elephant with

arrows; the monk of unblemished heart should, upon hearing it, put up with harsh speech

uttered’.50

This is a fairly close parallel to Z 2.138:

2.138 aysu hastä m¡ñämä jau—ysä kyeri halci p¥rnyau bitte

163Annotations on the Book of Zambasta, I

51 See Emmerick, Studies 2.173–174 for the etymology.

52 Translation by Régamey 1938, 103 § 122. In addition, the Tibetan version subsequently says that ‘Bhadra

descended from the skies’ (p. 107 § 132). According to Régamey, the Chinese translations agree on the wholewith the Tibetan.

53 I prefer to regard tt¤yä as the adverb ‘then’referring to the future Buddhahood of Bhadra rather than the

bi››u sahyätä tta aysu sahy£mä ys£raho panye uysnaurä

‘I am like a Ÿghting elephant: however much anyone pierces it with arrows, it endures all. So

I endure the harsh words (ys£ra ho) of every being’ (after Emmerick with modiŸcations).

In particular, the P¡li phrase v¡kya¿ pharusa¿ ‘harsh speech’ is a perfect match for the

Khotanese phrase ys£ra ho ‘harsh words’ with ho nom.-acc. pl. of hau- ‘word, speech’.51

Z 2.240

At the end of the story of Bhadra’s conversion, after the Buddha has preached the Doctrine to

him, Bhadra realises the doctrine of non-origination of dharmas (Z 2.231), the Buddha smiles

(Z 2.232–234), �nanda asks the reason for the smile (Z 2.235–236), the Buddha explains that

Bhadra will become a Buddha (Z 2.237–239), �nanda marvels at the announcement (Z

2.240), the Buddha rises up (Z 2.240), the Buddha explains the reason for Bhadra’s future

Buddhahood (Z 2.240–241) and Bhadra honours the Buddha (Z 2.242).

It is apparent that it would be more natural for Bhadra to rise up, not the Buddha. In fact,

the Tibetan version of the story conŸrms this, although it arranges the narration slightly

differently in that Bhadra rises up immediately after realising the non-origination of dharmas:

‘When the Lord had expounded these 4 achievements, the juggler Bhadra attained the

acceptance of the doctrine that all the dharmas are without origination and was pleased,

delighted, enraptured, rejoiced and very satisŸed and, as a result of this great joy, he rose up

to the skies to the height of seven palm-trees’.52

Accordingly, the manuscript reading balysi is a corruption for *bhadri, a lectio facilior that

was favoured by the identical metrical value of the two forms (2 1), so that the passage should

be emended as follows:

2.240 ¡nandä du™karu sastu käðe thatau panamäte *bhadri (ms. balysi)

ttai hv¡ñäte balysä se tt£yä param¡rthä d¡tä ™™ä÷aumä 3

‘It seemed a marvel to �nanda. Very quickly *Bhadra rises up. Thus the Buddha speaks to him:

“It will be the favour of the supreme meaning of the Law then (tt£yä)”’ (after Emmerick with

modiŸcations).53

164 Mauro Maggi

contracted gen.-dat. sg. of the reduplicated demonstrative pronoun (tt¤ye).

54 Restoration by Leumann, E 197.

55 E 196.

56 Cf. E xxxiii–xxxiv.

Z 14.11–12

Chap. 14 is defective in that the fourth p¡da of most of the lines is lost, which at times raises

difŸculties in the way of interpretation. Verse 11 is made particularly obscure not only by the

Ÿnal gap but also by its elliptical wording, so that its connection with verse 12 is not clear:

14.11 ››ar£rai b¥ta u dama-r¡›a padanda

pa¿jyau jsa uspurrä ™ätä — [. . . .]

14.12 ttäna cu aysm¥na mulysga mulysga nä hauta

balys¡na saittä mah¡y¡[ni ™a hauta] 54

‘(11) “His relics were distributed, and dharmar¡jik¡s were built”. The (‰r¡vakay¡na) is full of

the Ÿve (elements), (12) because their ability in mind is very limited. The Buddha(-power)

seems thus to the Mah¡y¡na’ (Emmerick).

The relics that are referred to here are the relics of the historical Buddha. Of the two

supplements in the translation of v. 11, ‘(‰r¡vakay¡na)’, i.e. the Vehicle of the Hearers, Ÿlls the

gap at the end of the line, whereas ‘(elements)’ is intended to bridge the elliptical wording of

the text that has only pa¿jyau jsa instr.-abl. pl. ‘Ÿve’. The restoration ‘(‰r¡vakay¡na)’ was

already suggested in his translation by Leumann, who pointed out, however, that the gap is

preceded by a fragment of the letter y- or l- and therefore cannot contain the compound

›r¡vakay¡nä.55 This difŸculty is overcome if, instead of the compound, one supplements the

phrase y[¡nä ™™¡v¡nu] ‘the Vehicle of the Hearers’, a Khotanese translation of the Sanskrit

compound that Ÿts both the context and the metre.56

Emmerick’s supplement ‘(elements)’, if correct, would be a translation of Skt. (mah¡)dh¡tu-

or (mah¡)bh¥ta- ‘gross elements’, i.e. earth, water, Ÿre, air and ether. However, one would

expect that, if the ‘Ÿve elements’ were meant, the ‘elements’ would be explicitly mentioned and

the numeral ‘Ÿve’ only implied, and not vice versa, all the more so because *dh¡ttyau or

*bh¥ttyau would be metrically equivalent to pa¿jyau (2 2) and because the reference to the

‘elements’ cannot be deduced from the context. In reality, because chap. 14 presents the

transcendental view of Mahayanist Buddhology, according to which ‘the pupils in the same

place see the Buddha in many ways as a result of their own (karmas)’ (Z 14.20 — Emmerick),

and because the verse under consideration comes immediately after some summary references

to the traditional view of the historical Buddha’s life offered by the ‰r¡vakay¡na and precedes

165Annotations on the Book of Zambasta, I

57 See E 31 and Skazanie 297.

the exposition of the Mahayanist view, it is probable that the verse under consideration refers

implicitly to the Ÿve Buddhas that have appeared or are to appear in the Bhadrakalpa, the

present age of the world, according to ancient Buddhism: the mythical Buddhas

Krakucchanda, Kanakamuni and K¡›yapa, as well as the historical Buddha ‰¡kyamuni, have

already appeared, whereas the Ÿfth, future Buddha will be Maitreya. Accordingly, I suggest the

following restoration and translation of the verse under consideration:

14.11 ››ar£rai b¥ta u dama-r¡›a padanda

pa¿jyau jsa uspurrä ™ätä y[¡nä ™™¡v¡nu]

‘(11) “His relics were distributed and monuments were built (to contain them)”. SatisŸed with

(just) Ÿve (Buddhas) is the V[ehicle of the Hearers]’.

As for verse 12, it is now clear that it is syntactically separated from the preceding verse and

that it contains a concluding remark on the inferiority of the Buddhology of ancient Buddhism

and a sentence introducing the exposition of Mahayanist Buddhology:

‘(12) Because they (i.e. the ‰r¡vakas) are limited in mind, the Buddha’s power seems limited

to them. For the Mah¡y¡[na this (is his) power]’.

Z 14.74

Leumann’s and Emmerick’s restoration of the beginning of verse 74 needs to be revised:

14.74 [kye my¡n¡-]indriya aysm¥na ut¡ra

¡››aina vasuta mah¡y¡nu pyuv¡’re

14.75 [kye v¡] aysm¥na u indriyo nuv¡ta

batu nu käðä mulysdä u sa¿ts¡rä puva’lsta .

14.76 [ttätä tta¿]du pyu’v¡’re kho ¡tamuvo’ pada¿ja

‘(74) (Some, of middling) sense, noble in mind, pure in heart, hear about the Mah¡y¡na. (75)

(Some) are restrained in mind and senses — they have very little compassion and are frightened

of sa¿s¡ra — (76) (these) hear so much as there is a description of in the �gamas’ (Emmerick).

Actually, Leumann read [kye my¡n]¡-indriya, but the facsimile shows just a scanty trace of

the ak™ara preceding indriya.57 It is theoretically possible that a trace of a postvocalic -¡ was still

visible when Leumann read the folio, but it is equally possible that his reading -¡ was

in uenced by the occurrence of the compound my¡n¡-indria- at the beginning of Z 2.75 kye

my¡n¡-indryiya hva’ndä with the regular Ÿve morae before the cadence (1 2 2 | 2 1 1 2 1). On

166 Mauro Maggi

58 See above on Z 2.75 etc.

59 See E xxxiv.

60 See the facsimile in Konow 1914, pl. xxxv, f. 369b (recte 269).

the other hand, it is strange that ‰r¡vakay¡na and Mah¡y¡na are correlated with the lower and

middle terms rather than with the lower and higher terms of the classiŸcation of beings into

Skt. m¬dvindriya- ‘of dull senses’, Skt. madhyendriya- ‘of middling senses’ and Skt. t£k™nendriya-

‘of sharp senses’.58 In fact, one would expect that, if the followers of the ‰r¡vakay¡na are

qualiŸed as beings of dull senses (Z 14.75 indriyo nuv¡ta), the followers of the Mah¡y¡na be

qualiŸed as beings of sharp senses (Kh. *t¬™÷a-indria-), the qualiŸcation as beings of middling

senses (Kh. my¡n¡-indria-) being reserved to the Pratyeka-buddhas. Support is lent to this

hypothesis by the statement found in Z 13.5: ‘What are these three Vehicles in the s¥tra? The

Mah¡y¡na is the chief one, the Pratyekay¡na is the second Vehicle, and the third is the

‰r¡vakay¡na’ (Emmerick). Accordingly, the text in the lacuna of Z 14.74 should be restored

as [kye t¬™÷a-]indriya. Like Leumann’s and Emmerick’s restoration kye my¡n¡°, the suggested

restoration also constitutes a regular p¡da onset of Ÿve morae preceding the caesura because the

pronoun kye can count as either a light or a heavy syllable.59

Z 14.89

Following Leumann, Emmerick tentatively read balysä ‘Buddha’ at the end of Z 14.89:

14.88 tt¡vatr£›¡nu patäna närmäte brahma cerä

tt¡va tr£›a panye pa—täna nita’stä . 88

14.89 pani tt¡va tr£›ä pa—täna brahmu vajsä™ðe

mamä patäna ¡ste muho jsa hv¡ñite balysä

‘(88) In the presence of the tr¡yastri¿›a-gods, he [i.e. Brahm¡] created Brahma-gods. As many

as are the tr¡yastri¿›a-gods, one (Brahma-god) sat down before each. (89) Each tr¡yastri¿›a-

god sees a Brahma-god before him: “The Buddha sits before me, talks with me”’ (Emmerick).

It is apparent, however, that the context requires brahmä (i.e. brahmä, not clearly visible)

to obtain: ‘Brahm¡ sits before me, talks with me’. A conŸrmation, if necessary at all, is

provided by Z 4.11: ‘Brahm¡ conjured up thirty-two Brahma-gods in a group. To the

tr¡yastri¿›a-gods (and) to Brahm¡ they seemed (to exist)’ (Emmerick). Unfortunately, the

manuscript is damaged and virtually illegible here, so that both readings seem possible.60

Should the manuscript have the reading balysä, this should be regarded anyway as a lectio

facilior as in Z 2.240 (see above) and emended accordingly.

167Annotations on the Book of Zambasta, I

61 SDTV 6.361.

62 Leumann1967, 373. Cf. Maggi 2004b, 187 for the arrangement of the text.

63 Since the folio lacks both its left end (that should have contained the folio number on the obverse) and itsright end (that could have contained the verse numbering), it is impossible to determine the obverse of thefragment or the verse numbers.

64 For the iconographical features of ‰¡kyamuni and Amit¡bha (that are only distinguished by the golden andred colour) see Schumann 1995, 132, 157, 159 and 162, and Wikramagamage 1993. For seated ame-shouldered Buddhas from Central Asia see Rhie 1999, 71–94, esp. 91–92, on the so-called Harvard ame-shouldered Buddha, that is identiŸed by her as ‰¡kyamuni; see also pp. 79 with n. 123 (Near-Eastern originof the ame motif), 223–224 ( ame-shouldered Buddha from B¡miy¡n), 267–268 (possible relation of the

Harvard Buddha with Khotan) and 307–308 ( ame-shouldered Buddhas from Rawak).

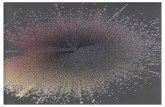

Z 24.126–161

In the Ÿrst part of chap. 24, which consists of an account of the world before the Buddha

‰akyamuni and of his birth and early life until his Ÿrst sermons, vv. 126–161 are missing in the

main manuscript (Z1). However, it is likely that the fragment IOL Khot 161/4 (= H. 143a NS

99 KT 5.45; Ÿg. 1), which belongs to a variant manuscript and was recently re-edited with a

translation by Prods O. Skjærvø,61 belongs to this lacuna. Manu Leumann tentatively

assigned this fragment to Z on the basis of the arrangement of the text into columns that is

characteristic of the manuscripts of this work.62 That the fragment may belong to Z 24 and

particularly to the present lacuna is suggested, notwithstanding the fragmentary context, by

several details and particularly by the mention of the god N¡r¡ya÷a. Just a few verses before the

lacuna in the main manuscript, N¡r¡ya÷a is said to have defeated the demons (r¡k™asa) that

threatened mankind (Z 24.115–117) and immediately after the lacuna he is said to be no

longer able to remedy the damages that were being caused by the kle›as (anger, passion,

ignorance etc.) personiŸed as demons (kle›a-r¡k™asa; Z 24.162–163).

The hypothesis that the fragment belongs to the present lacuna, which precedes the

Buddha’s decision to be born into the world (Z 24.182Ù.), is strengthened by the presence of

a Buddha image inside a double circle on side a of the fragment (Ÿg. 2).63 The depicted

Buddha is sitting with crossed legs (Skt. paryank¡sana) on a lotus seat (padm¡sana), his hands

are in meditation position (dhy¡namudr¡) and hold an alms bowl (p¡tra), while a halo

(vy¡maprabh¡) surrounds the body, an aureole irradiates from the head, and ames issue from

behind his shoulders. These iconographical traits, especially the bowl, suggest that the depicted

Buddha be identiŸed with the historical Buddha ‰¡kyamuni himself or, theoretically, with

Amit¡bha, the celestial Buddha associated with him.64

168 Mauro Maggi

References

Abbreviations of Khotanese texts are in line with those suggested in Emmerick 1992.

Bacot, J. (1930): (ed.) Dictionnaire tibétain-sanscrit par Tse-Ring-Ouang-Gyal (Che riª dbaª rgyal):

reproduction phototypique. Paris 1930.

Bailey, H.W. (1937): “Hvatanica, II.” Bulletin of the School of Oriental Studies 9.1 (1937), 69–78 (=

Bailey 1981, 1.351–360).

—— (1946): “G¡ndh¡r£.” Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 11 (1946), 764–797 (=

Bailey 1981, 2.293–326).

—— (1981): Opera minora: articles on Iranian studies, ed. M. Nawabi. Shiraz 1981, 2 vols.

BHSD = F. Edgerton: Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit grammar and dictionary. 2: Dictionary. New Haven

1953.

Brekke, T. (2000): “The Ca¿g£s¥tra of the Mah¡sa¿ghika-Lokottarav¡dins.” In: J. Braarvig (ed.):

Buddhist manuscripts. 1. Oslo 2000 (Manuscripts in the Schøyen Collection 1), 53–62.

CDIAL = R.L. Turner, A comparative dictionary of the Indo-Aryan languages. London 1966.

CDIALAdd = R.L. Turner, A comparative dictionary of the Indo-Aryan languages. Addenda and

corrigenda, ed. J.C. Wright. London 1985.

Degener, A. (1987): “Khotanische Komposita.” Münchener Studien zur Sprachwissenschaft 48 (1987),

27–69.

—— (1989a): Khotanische SufŸxe. Stuttgart 1989.

—— (1989b): “Läuterung im ‘Book of Zambasta’.” Studien zur Indologie und Iranistik 15 (1989),

51–58.

Dict. = H.W. Bailey: Dictionary of Khotan Saka. Cambridge 1979.

Dresden, M.J. (1955): The J¡takastava or ‘Praise of the Buddha’s former births’: Indo-Scythian

(Khotanese) text, English translation, grammatical notes and glossaries. Philadelphia 1955 (Transactions

of the American Philosophical Society n.s. 45.5).

Duan Qing (2007): “The Maitr£-bh¡van¡-prakara÷a: a Chinese parallel to the third chapter of the Book

of Zambasta.” In: M. Macuch, M. Maggi, W. Sundermann (eds.): Iranian languages and texts from

Iran and Turan: Ronald E. Emmerick memorial volume. Wiesbaden 2007, 39–58.

E = E. Leumann: Das nordarische (sakische) Lehrgedicht des Buddhismus: Text und Übersetzung, aus dem

Nachlaß hrsg. von M. Leumann. Leipzig 1933–1936 (Abhandlungen für die Kunde des Morgen-

landes 20).

Emmerick, R.E. (1966): “The nine new fragments from the Book of Zambasta.” Asia Major n.s. 12.2

(1966), 148–178.

—— (1967): “The ten new folios of Khotanese.” Asia Major n.s. 13.1–2 (1967), 1–47.

169Annotations on the Book of Zambasta, I

—— (1968a): The book of Zambasta, a Khotanese poem on Buddhism. London 1968 (London Oriental

series 21).

—— (1968b): “Khotanese metrics.” Asia Major n.s. 14.1 (1968), 1–20.

—— (1969): “Notes on The book of Zambasta.” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society 1969, 59–74.

—— (1990): “Khotanese ma ‘not’.” In: G. Gnoli, A. Panaino (eds.): Proceedings of the Ÿrst European

Conference of Iranian Studies held in Turin, September 7th-11th, 1987 by the Societas Iranologica

Europaea. 1: Old and Middle Iranian studies. Rome 1990, 95–113.

—— (1992): A guide to the literature of Khotan, 2nd ed. Tokyo 1992 (Studia philologica Buddhica.

Occasional paper series 3).

Falk, H. (2000): “Protective inscriptions on Buddhist monastic implements.” In: C. Chojnacki, J.-U.

Hartmann, V.M. Tschannerl (eds.): Vividharatnakara÷ðaka: Festgabe für Adelheid Mette. Swisttal-

Odendorf 2000 (Indica et Tibetica 37), 251–257.

Fussman, G. (1972): Atlas linguistique des parlers dardes et kaŸrs. 2: Commentaire. Paris 1972.

Hitch, D.A. (1990): “Old Khotanese synchronic umlaut.” Indo-Iranian Journal 33.3 (1990), 177–198.

Konow, S. (1914): “Fragments of a Buddhist work in the ancient Aryan language of Chinese

Turkestan.” Memoirs of the Asiatic Society of Bengal 5.2 (1914), 13–41, pls. xxxiii–xxxv.

—— (1934): “The late Professor Leumann’s edition of a new Saka text[, I].” Norsk tidsskrift for

sprogvidenskap 7 (1934), 5–55.

—— (1939): “The late Professor Leumann’s edition of a new Saka text, II.” Norsk tidsskrift for

sprogvidenskap 11 (1939), 5–84.

KT 1–7 = H. W. Bailey: Khotanese texts. Cambridge: vol. 1, 1945; vol. 2, 1954; vol. 3, 1956 (vol. 1–3:

2nd ed. in one vol. 1969; repr. 1980); vol. 4, 1961 (repr. 1979); vol. 5, 1963 (repr. 1980); vol. 6:

Prolexis to the Book of Zambasta, 1967; vol. 7, 1985.

Lalitavistara = P.L. Vaidya (ed.): Lalitavistara. Darbhanga 1958 (Buddhist Sanskrit texts 1).

Maggi, M. (2004a): “Il Grande veicolo in Asia Centrale: il buddhismo di Khotan e il Libro di

Zambasta”; “Il libro di Zambasta: capitoli 1–2, 5, 13–4, 24.” In: R. Gnoli (ed.): La rivelazione del

Buddha. 2: Il Grande veicolo, introd. ai testi tradotti di C. Cicuzza e F. Sferra con contributi di M.

Maggi e C. Pecchia. Milano 2004 (I meridiani. Classici dello spirito), pp. clii–clxv, ccxv–ccxviii,

1193–1285.

—— (2004b): “The manuscript T III S 16: its importance for the history of Khotanese literature.” In:

D. Durkin-Meisterernst et al. (eds.): Turfan revisited: the Ÿrst century of research into the arts and

cultures of the Silk Road. Berlin 2004 (Monographien zur indischen Archäologie, Kunst und

Philologie 17), 184a–190b, 457.

—— (2005): Abstract n. 28. Abstracta Iranica 26 (2003 [2005]), 18–19.

170 Mauro Maggi

—— (2007): “N¡g¡rjuna’s quotation in the Khotanese Book of Zambasta.” Annual report of the

International Research Institute for Advanced Buddhology at Soka University 10 (2006 [2007]), 533–535.

Mah¡vyutpatti = R. Sakaki (ed.): Mah¡vyutpatti. Honýyaku myÚgi taish¥: Bon-ZÚ-kan-Wa yonýyaku taikÚ.

Kyoto 1916.

Masefield, P. (1994) (tr.): The Ud¡na. Oxford 1994 (Sacred books of the Buddhists 42).

Nattier, J. (1990): “Church language and vernacular language in Central Asian Buddhism.” Numen

37 (1990), 193–219.

—— (1991): Once upon a future time: studies in a Buddhist prophecy of decline. Berkeley 1991 (Nanzan

studies in Asian religions 1).

Nettippakara÷a = E. Hardy (ed.): The Nettipakara÷a: with extracts from Dhammap¡la’s commentary.

Oxford 1902.

PED = T.W. Rhys Davids, W. Stede: The Pali Text Society’s Pali-English dictionary. Oxford

1921–1925.

Régamey, K. (1938): The Bhadram¡y¡k¡ravy¡kara÷a: introduction, Tibetan text, translation and notes.

Warsaw 1938 [repr. Delhi 1990].

Rhie, M.M. (1999): Handbuch der Orientalistik. 4: China. 12: Early Buddhist art of China and Central

Asia. 1: Later Han, Three Kingdoms and Western Chin in China and Bactria to Shan-shan in Central

Asia. Leiden 1999.

Sander, L. (1988): “Auftraggeber, Schreiber und Schreibeigenheiten im Spiegel khotansakischer

Handschriften in formaler Br¡hm£”. In: P. Kosta (ed.): Studia Indogermanica et Slavica: Festgabe für

Werner Thomas zum 65. Geburtstag. München 1988, 533–549.

Sanghabhedavastu = R. Gnoli (ed.): The Gilgit manuscript of the Sanghabhedavastu, being the 17th and

last section of the Vinaya of the M¥lasarv¡stiv¡din, with the assistance of T. Venkatacharya. Roma

1977–1978 (Serie orientale Roma 49.1–2), 2 vols.

Schumann, H.W. (1995): Mah¡y¡na-Buddhismus: das Große Fahrzeug über den Ozean des Leidens,

überarbeitete Neuausg. München 1995.

SDTV 6 = P.O. Skjærvø: Khotanese manuscripts from Chinese Turkestan in the British Library: a

complete catalogue with texts and translations, with contributions by U. Sims-Williams. London 2002

(Corpus Inscriptionum Iranicarum. 2: Inscriptions of the Seleucid and Parthian periods and of

Eastern Iran and Central Asia. 5: Saka. Texts 6).

SGS = R.E. Emmerick: Saka grammatical studies. London 1968 (London Oriental series 20).

Skazanie = V.S. Vorob’ëv-Desjatovskij, M.I. Vorob’ëva-Desjatovskaja: Skazanie o Bhadre: novye

listy sakskoj rukopisi “E”: faksimile teksta, transkripcija, perevod, predislovie, vstupitel’naja stat’ja,

glossarij i priloženie. Moskva 1965 (Pamjatniki pis’mennosti Vostoka 1).

Studies 1–3 = R.E. Emmerick, P.O. Skjærvø: Studies in the vocabulary of Khotanese. Wien: 1, 1982;

2, 1987; 3, ed. R.E. Emmerick, contributed by G. Canevascini et al., 1997.

171Annotations on the Book of Zambasta, I

SWTF = H. Bechert (ed.): Sanskrit-Wörterbuch der buddhistichen Texten aus den Turfan-Funden und

der kanonischen Literatur der Sarv¡stiv¡da-Schule, begonnen von E. Waldschmidt. Göttingen 1973–.

TaishÚ = J. Takakusu, K. Watanabe (eds.): TaishÚ shinsh¥ daizÚkyÚ. The TripiÞaka in Chinese. Tokyo

1924–1935, 100 vols.

Ud¡na = P. Steinthal (ed.): Ud¡na. Oxford 1885.

Visuddhimagga = H. C. Warren (ed.): Visuddhimagga of Buddhaghosâcariya, rev. D. Kosambi.

Cambridge (Mass.) 1950 (Harvard Oriental series 41).

Wikramagamage, C. (1993): “Iconography.” In: Encyclopaedia of Buddhism, vol. 5.4. Colombo 1993,

499–504.