A. PANE, Crapolla: a cultural landscape on the Amalfi Coast, in Landscape as architecture. Identity...

Transcript of A. PANE, Crapolla: a cultural landscape on the Amalfi Coast, in Landscape as architecture. Identity...

Architectureand restoration

pathscrossesexperiences

Architetturae restauro

percorsiintrecciesperienze

Paesaggio come architetturaIdentità e conservazione del sito culturale di Crapolla

edited by | a cura di

Valentina Russo

NARDINI EDITORE

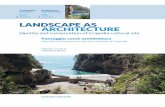

LANDSCAPE ASARCHITECTURE

Identity and conservation of Crapolla cultural site

▶ ▶ ▶ ▶

Landscape as ArchitectureIdentity and conservation of Crapolla cultural site

Paesaggio come architetturaIdentità e conservazione del sito culturale di Crapolla

Starting from the urgent problems and complex challenges for the conservationof stratified landscapes, places of the synthesis between human activity andnature, the volume presents the results of a research project that involved since2008 the cultural site of Crapolla, located on the southern slope of the Sorrento-Amalfi Peninsula and within the Punta Campanella Marine Protected Area.

Paradigm of landscapes where a thousand year old history has settled andwhere the emotional values emerge with strength, because of the presence ofspring waters and of hills jutting into the sea, of the etymological allusion toancient myths and gods, the site of Crapolla is full of a dense sense of thesacred. With it, the deep cracks of the rocks and the dizzying height of the lat-ter assure a romantic aura to the whole. The deep “gorge” includes impressivebuildings referable to ancient usages of the place, a port for sailors, site for thestorage of food and for the supply of fresh water. The forms of architecture ofthe monazeni embedded into the rocks, the ruins of a Medieval abbey, theimposing mass of a sixteenth-century tower witness all the high strategic signi-ficance that the cove has assumed in the historical landscape of the Peninsulaover the centuries.

In the symbiosis between sublime nature and architecture, the landscapeof Crapolla is, at the same time, very "fragile" and at risk of oblivion. The resear-ch here published, together with the numerous studies and experiences carriedout in Italian and European contexts, face with rigor of analysis and activeapproach many issues related to the understanding of the intangible values −i.e. anthropological, literary and social ones − and of the physical and construc-tion characteristics of the artifacts and the landscape.

This is in order to highlight, through an integrated methodology of resear-ch, a coherent approach from the small to the large scale for a programmedpreservation of the cultural landscape so as to prevent, through restoration andwith the involvement of the local communities, the irreversible loss of preciousvestiges of the past.

A partire dalle cogenti problematiche e sfide complesse connesse alla conser-vazione dei paesaggi stratificati, luoghi di sintesi tra azione umana e natura, ilvolume presenta i risultati di un percorso di ricerca che ha interessato dal 2008il sito culturale di Crapolla, posto sul versante meridionale della Penisola sor-rentino-amalfitana ed entro l'Area Marina Protetta Punta Campanella.

Paradigma di paesaggi nei quali è sedimentata una storia ultramillenariae nei quali le valenze emozionali emergono con forza, per la compresenza diacque sorgive e di rilievi strapiombanti verso il mare, per l'allusione etimologi-ca ad antichi miti e divinità, il sito di Crapolla è intriso di un denso senso delsacro. Con esso, le profonde spaccature nelle rocce e l'altezza vertiginosa diqueste ultime conferiscono un'aura romantica all'insieme. La profonda "forra"accoglie fabbriche imponenti riferibili ad usi antichi del luogo, approdo per inaviganti, sito per la conservazione di derrate alimentari e per il rifornimento diacque dolci. Le architetture dei “monazeni” incastonati nelle rocce, le rovine diun'abbazia medievale, la possente massa di una torre cinquecentesca testimo-niano tutti dell'elevato significato strategico che l'insenatura ha assunto nelpaesaggio storico della Penisola attraverso i secoli.

Nella simbiosi tra natura sublime e architettura, il paesaggio di Crapolla è,al contempo, particolarmente "fragile" e a rischio di oblio. Le ricerche che sipresentano, intrecciate a molteplici studi ed esperienze condotte in contestiitaliani ed europei, affrontano con rigore analitico e slancio propositivo molte-plici questioni connesse alla comprensione delle valenze intangibili − antropo-logiche, letterarie e sociali −, nonché delle caratteristiche fisiche e costruttivedei manufatti e del paesaggio.

Ciò con l'obiettivo di evidenziare, attraverso una metodologia integrata diricerca, una coerenza di approccio dalla piccola alla grande scala per la conser-vazione programmata del paesaggio culturale allo scopo di prevenire, attraver-so il restauro e con il coinvolgimento delle comunità locali, la perdita irreversi-bile di preziose testimonianze del passato.

▶ ▶▶ ▶

Valentina Russo, Architect, Ph.D. in Conservation of Architectural Heritage, isAssociate Professor in Restoration at the University of Naples Federico II (Departmentof Architecture). Professor in the Postgraduate School of Specialization of Architecturaland Landscape Heritage and in the Ph.D. Board of Architecture (Univ. of Naples),she is currently the scientific coordinator of the international Agreements among theUniversity of Naples Federico II and the Izmir Institute of Technology (Turkey), theÉcole Nationale Supérieure d’Architecture of Lyon (France), the Artesis UniversityCollege of Antwerp (Belgium) and the Polytechnic University of Valencia (Spain). She coordinates and carries on funded research programs concerning the historical,methodological and design issues in architectural and landscape restoration andhas edited the organization of exhibitions and conferences, with the publication ofcatalogues and Proceedings. She is the author of monographs, numerous essays involumes and articles in scientific journals that focus specific attention on the relationsamong interpretative, constructive and planning aspects in Restoration.

With contributions by:

Lucio Amato, Geologist, Tecno In S.p.A. Technical DirectorGiovanni Antonucci, Geologist, Tecno In S.p.A.Marleen Arckens, Archaeologist, Artesis University College of AntwerpAldo Aveta, Full Professor in Restoration, University of Naples Federico IIStella Casiello, Full Professor in Restoration, University of Naples Federico IIGiovanna Ceniccola, Architect, Ph.D. in Conservation of Architectural and Landscape

Heritage, University of Naples Federico IIValentina Cristini, Assistant Professor in Restoration, Polytechnic University of ValenciaFrancesco Delizia, Ministry of the Cultural Heritage and Tourism, Regional Directorate

for Cultural and Landscape Heritage of Emilia-RomagnaGianluigi de Martino, Assistant Professor in Restoration, University of Naples Federico IIFrancesco Doglioni, Associate Professor in Restoration, University IUAV of VeniceDaniela Esposito, Full Professor in Restoration, University of Rome La SapienzaGiuseppe Fiengo, Full Professor in Restoration, Second University of NaplesRossana Gabrielli, Archaeologist, Partner and Chief of the Analysis area of Leonardo

S.r.l. (Bologna)Giovanna Greco, Full Professor in Archaeology and History of Greek and Roman Art,

University of Naples Federico IIMine Hamamcıoğlu-Turan, Assistant Professor in Restoration, İzmir Institute

of TechnologyDonato Iaccarino, Councillor for Culture, Tourism and Promotion of the Paths,

Municipality of Massa LubrenseMaria Leus, Professor in Restoration and Conservation of monuments, Artesis

University College of AntwerpMario R. Losasso, Full Professor in Technology of Architecture, University of Naples

Federico IIBianca Gioia Marino, Associate Professor in Restoration, University of Naples Federico IIPasquale Miano, Associate Professor in Architectural Planning, University of Naples

Federico IIStefano F. Musso, Full Professor in Restoration, University of GenuaAndrea Pane, Assistant Professor in Restoration, University of Naples Federico IIGiulio Pane, Full Professor in History of Architecture, University of Naples Federico IIPatrizio Pensabene, Full Professor in Classical Archaeology, University of Rome

La SapienzaRenata Picone, Associate Professor in Restoration, University of Naples Federico IIStefania Pollone, Architect, Ph.D. student in History and Conservation of Architectural

and Landscape Heritage, University of Naples Federico IIEmanuele Romeo, Associate Professor in Restoration, Polytechnic of TurinJosé Ramón Ruiz-Checa, Associate Professor in Construction and Patrimonial

managing, Polytechnic University of ValenciaStefano Ruocco, President of Archeoclub d'Italia-Massa LubrenseEnrica Santaniello, Architect, Specialist in Architectural and Landscape HeritageGianluca Vitagliano, Architect, Ministry of the Cultural Heritage and Tourism,

Superintendence for the Archaeological Heritage of Pompeii Herculaneumand Stabia

Paesaggio come architetturaIdentità e conservazione del sito culturale di Crapolla

LANDSCAPE AS Identity and conservation of Crapolla cultural site

▶ ▶

Architectureand restoration

pathscrossesexperiences

Architetturae restauro

percorsiintrecciesperienze▶ ▶

ISBN 978-88-404-0042-6

€ 40,00

Paesaggio come architetturaIdentità e conservazione del sito culturale di Crapolla

LANDSCAPE AS ARCHITECTUREIdentity and conservation of Crapolla cultural site

▶ ▶▶ ▶

Architettura e restauro | Architecture and restorationpercorsi intrecci esperienze | paths crosses experiences

Direttore editoriale | publishing directorAndrea Galeazzi

Direzione scientifica | scientific directionValentina Russo

LANDSCAPE AS ARCHITECTUREIdentity and conservation of Crapolla cultural site

© 2014 Nardini Editorewww.nardinieditore.it

Edited by | a cura diValentina Russo

Texts by | contributi diLucio Amato, Giovanni Antonucci, Marleen Arckens, Aldo Aveta, Stella Casiello,Giovanna Ceniccola, Valentina Cristini, Francesco Delizia, Gianluigi de Martino,Francesco Doglioni, Daniela Esposito, Giuseppe Fiengo, Rossana Gabrielli, Giovanna Greco,Mine Hamamcıoğlu-Turan, Donato Iaccarino, Maria Leus, Mario R. Losasso, Bianca Gioia Marino,Pasquale Miano, Stefano F. Musso, Andrea Pane, Giulio Pane, Patrizio Pensabene,Renata Picone, Stefania Pollone, Emanuele Romeo, José Ramón Ruiz-Checa,Stefano Ruocco, Enrica Santaniello, Gianluca Vitagliano

Photos | fotografieAll the photos in the texts are due to the Authors and date to the research period 2008-2013, except for those where it is specified otherwise and for the ones in the separatingpages, whose references are at the end of the volume.

Translations | traduzioniThe translation of all the texts from Italian to English − together with the quotationsand their English revision − is due to Prof. John Crockett, Università degli Studi di NapoliFederico II (University Language Centre - Centro Linguistico di Ateneo).The text by D. Iaccarino and S. Ruocco has been translated by Dr. Ruth Peake.

Layout | progetto graficoEnnio Bazzoni

Comitato scientifico internazionale | International scientific committeeAldo Aveta, Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II Stella Casiello, Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II Maria Ida Catalano, Università degli Studi della Tuscia Maurizio De Vita, Università degli Studi di Firenze Carolina Di Biase, Politecnico di Milano Donatella Fiorani, Università degli Studi di Roma La Sapienza Maria Adriana Giusti, Politecnico di Torino Giacinta Jean, Scuola Universitaria Professionale della Svizzera Italiana Pamela S. Jerome, Columbia University Paulo Lourenço, University of Minho Randall Mason, University of Pennsylvania Camilla Mileto, Universidad Politécnica de Valencia Renata Picone, Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II Marco Pretelli, Università di Bologna Emanuele Romeo, Politecnico di Torino Fernando Vegas López-Manzanares, Universidad Politécnica de Valencia

Tutti i volumi pubblicati nella Collana sono sottopostia procedura di referaggio esterno esercitato in forma anonima.All volumes published in the Series are subjected toexternal blind peer-review process.

On the cover page:Crapolla (Massa Lubrense).The cove from ground (photo V. Russo 2013).

The volume is published withthe financial support of:

Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II

Dipartimento di Architettura

with:

Comune di Massa Lubrense

Comune di Sorrento

Area Marina ProtettaPunta Campanella

Paesaggio come architetturaIdentità e conservazione del sito culturale di Crapolla

edited by | a cura di

Valentina Russo

NARDINI EDITORE

LANDSCAPE ASARCHITECTURE

Identity and conservation of Crapolla cultural site

FOREWORDS

Gaetano Manfredi, Rector of the University of Naples Federico II . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . pag. 7

Mario R. Losasso, Director of the Department of Architecture . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ” 8

Leone Gargiulo, Mayor of Massa Lubrense . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ” 10

Davide Gargiulo, President of Punta Campanella Marine Protected Area . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ” 10

LANDSCAPE AS ARCHITECTURE

Valentina Russo

Apollo’s landscape, risk, interpretation, conservation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ” 13

CRAPOLLA. LANDSCAPE, ARCHAEOLOGY, ARCHITECTURE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ” 33

Stella Casiello

Landscapes as relation between man and nature: protection and enhancement . . . . . . . . . . . . ” 35

Andrea Pane

Crapolla: a cultural landscape on the Amalfi Coast . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ” 41

Gianluigi de Martino

The archaeological evidence of the Sorrento Peninsula and Crapolla . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ” 57

Francesco Doglioni

The ancient cisterns. Stratigraphic observations and interpretation of building processes . . . . . . ” 65

Valentina Russo

Memory and conservation of fragile ruins. The Abbey of St. Peter at Crapolla . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ” 73

Daniela Esposito, Patrizio Pensabene

Two cases of reuse in Campania: the church of St. Peter in Crapolla

and the bell tower of the Pietrasanta in Naples . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ” 97

Lucio Amato, Giovanni Antonucci

Geophysical survey with magnetometric techniques in the Abbey of St. Peter at Crapolla . . . . . ” 113

Gianluca Vitagliano

Rural architecture in Crapolla fjord: a heritage to protect . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ” 117

Francesco Delizia

St. Peter’s Tower at Crapolla. An example of the defensive system

of the Sorrentine Peninsula in the Viceroyal Age . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ” 123

Enrica Santaniello

The cantieri masonry of St. Peter's Tower.

Building techniques and similarities in the peninsular context . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ” 129

Rossana Gabrielli

Ancient mortars in the archaeological site of Crapolla: laboratory analysis . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ” 137

Contents

Donato Iaccarino, Stefano Ruocco

From tangible to intangible values. Traditions in Crapolla . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . pag. 149

CRAPOLLA LAB REPORTS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ” 159

Linda Miedema, Alfredo Roccia, Riccardo Rudiero, Alberto Maria Talarico, Sara Varanese

The environmental context . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ” 161

Thijs Bennebroek, Agostino Buonomo, Licia Genua, Clorinda V. Grande,

Teresa Laudonia, Michelle Smets

The archaeological heritage . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ” 169

Sonia Colletta, Lucia Ganoza, Jose Antonio López Salas, Romina Muccio, Laura Paone, Lia Romano

The monazeni permanence . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ” 179

Maria Antonia Aldarelli, Giuseppe Camarda, Federica Comes, Romana Fialová,

Chiara Ficarra, Lynn Rongé, Giovanna Russo Krauss, Giuseppina Vitiello, Federico Zoni

St. Peter's Abbey as palimpsest . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ” 187

Elisabetta Candeloro, Angela D’Anna, Ioanna Fragkaki, Marina Martinez Sanchis, Julie van de Velde

The architecture of St. Peter's Tower . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ” 195

Valentina Russo, Stefania Pollone

The stratigraphical interpretation of St. Peter's Tower. Dimensional survey results . . . . . . . . . . . ” 203

PARALLELS

ARCHITECTURE AND MEMORY OF THE ANTIQUE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ” 209

Giovanna Greco

Peoples in the Sorrentine Peninsula, between myth and reality . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ” 211

Patrizio Pensabene

Architectural spolia between Late-Antiquity and the Middle Ages . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ” 223

Daniela Esposito

The reuse building site in the Roman area through the Middle Ages and contemporary times . . ” 233

Emanuele Romeo

Temple, church, mosque: transformation over the centuries . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ” 241

ETHICS AND SUSTAINABILITY IN CONSERVATION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ” 247

Aldo Aveta

Historic urban landscape and integrated conservation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ” 249

Giuseppe Fiengo

Conservation and enhancement of ruined monuments in the Amalfi Coast . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ” 255

Renata Picone

A sustainable architecture. Rustic dwellings in the area between Capri

and the Amalfi-Sorrentine Coast . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . pag. 265

Giovanna Ceniccola

Interpretation and preservation of the architectural surfaces: the lapillus coverings . . . . . . . . . . ” 275

Bianca Gioia Marino

Landscape and image: perception of authenticity and identity of places . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ” 281

Stefania Pollone

Landscape conservation and ancient routes. Historical traces in Massa Lubrense land . . . . . . . . ” 289

CONSERVATION, PROTECTION AND ENHANCEMENT:

A COMPARISON OF EXPERIENCES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ” 309

Mario R. Losasso

Technologies and environmental design for the recovery of sensitive contexts . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ” 311

Giulio Pane

Fuenti, Jeranto, Ravello auditorium: three equivocal cases of landscape protection . . . . . . . . . . . ” 321

Pasquale Miano

From panorama to landscape. The case of Punta Corona in Agerola . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ” 329

Stefano Francesco Musso

The destiny of the built landscapes, between nature and culture. The Cinque Terre in Liguria . . . ” 339

Valentina Cristini, José Ramón Ruiz Checa

Interpretation of building processes and material decay phenomena in some examples

of Spanish traditional architecture . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ” 351

José Ramón Ruiz Checa, Valentina Cristini

A methodological proposal for a territorial analysis: watchtowers

of 12th-13th centuries in Spain . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ” 357

Maria Leus, Marleen Arckens

The dilemma between preservation and experience of archaeological heritage . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ” 363

Mine Hamamcıoğlu-Turan

Contemporary applications for documentation of historical buildings and landscapes . . . . . . . . ” 367

ITALIAN SUMMARIES | SINTESI . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . “ 375

AUTHORS OF REPORTS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . “ 418

REFERENCES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . “ 419

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . “ 419

INDEX OF THE NAMES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . “ 420

Introduction

As Michael Jakob has recently argued «this is definitely the landscape era», highligh-

ting the risks of an extensive approach, which he describes as «omni-landscape», where

the authentic experience of real life is likely to be replaced by speeches and images1. Thus,

for the purpose of this study, it is crucial to provide a clear definition of “landscape” befo-

re turning the attention to the fjord of Crapolla within the framework of the Sorrento-

Amalfi Peninsula.

Firstly, it is important to highlight that the word “landscape”, in Italian paesaggio,

means something very different from the two similar terms “territory” and “environ-

ment”2. An opposition is marked between an anthropocentric and ecocentric concept of

“landscape”. In this respect, Rosario Assunto’s work Il paesaggio e l’estetica (1973)3

(Landscape and Esthetics) emphasizes the aesthetic and cultural component of the land-

scape, in open opposition to the stance of ecologists and environmentalists.

After a long debate which lasted over a century, the concept of “landscape” has regai-

ned the prominent position it had partially lost during the second half of the 20th century,

when the concept of “environment” had taken over as it was closer to the environmental

sensitivity of the time4. The approval of the European Landscape Convention in 2000, rati-

fied in Italy in 2006, seems to fully emphasize the subjective and anthropogenic compo-

nent of landscapes, recalling collective perception and the presence of human factors as

key in all definitions of landscape5. This interpretation has been almost fully implemented

by means of the recent (2008) amendments to the Italian Codice dei Beni Culturali e del

Paesaggio (Cultural Heritage and Landscape Code), which defines the landscape as a «ter-

ritory expressing an identity, whose character derives from natural and human factors and

their interrelations»6.

41

Crapolla: a cultural landscapeon the Amalfi Coast

LANDSCAPE AS ARCHITECTURE

1. M. Jakob, Il paesaggio, Il Mulino, Bologna 2009, pp. 7 and foll.2. See L. Scazzosi, Leggere e valutare i paesaggi. Confronti, in Id. (ed.), Leggere il paesaggio. Confronti interna-

zionali, Gangemi, Roma 2002, p. 21.3. R. Assunto, Il paesaggio e l’estetica, Giannini, Napoli 1973.4. P. D’Angelo, Estetica della natura. Bellezza naturale, paesaggio, arte ambientale, Laterza, Roma-Bari 2001,

20032.5. «”Landscape” means an area, as perceived by people, whose character is the result of the action and inte-

raction of natural and/or human factors» (European Landscape Convention, Florence, 20 October 2000,ratified by the Italian government with L. 9 January 2006 n. 14).

6. Art. 131 comma 1 and 4, Codice dei Beni Culturali e del Paesaggio, D. Lgs. 22 January 2004 n. 42 and followingupdates.

Andrea Pane

This is the perspective adopted when approaching Crapolla, intended as a significant

cultural landscape, where by landscape we mean the «aesthetic identity of the sites», to

quote philosopher Paolo D’Angelo. However, far from neglecting the geographical, geo-

morphological, biological, environmental, historical, and cultural factors that characterise

this site, this point of view summarizes them in an overview that is enriched with such

expertise, without which the perception of landscapes would definitely risk to be poorer

and partial, in analogy with what happens in other fields such as art history, where know-

ledge of philological data contributes to the formulation of aesthetic judgments7.

The historical aspects and cultural elements characterising the entire Italian landsca-

pe8 must be taken into due consideration. In the specific case of Crapolla, these consist of

material and immaterial documents, among which a particular role is played by literary

evidence, objects of material culture, ethno-anthropological elements, and the symbolic

importance of the places, which are significant, as will be seen, for the mythological and

religious issues concerning the fjord of Crapolla.

The characters of the land

«Between Sorrento and Salerno, one can see sheer drop cliffs, dreadful splits among

the mountains, houses embedded in rocks, from which the colour only stands out, falls of

vineyards over impassable slopes, and the monasteries-fortresses in the middle of the

coast». This short description, written by Guido Piovene in his famous Viaggio in Italia,

published in 19589, clearly depicts the general elements of Sorrentine peninsula’s landsca-

pe, particularly the renowned Amalfi Coast facing the Gulf of Salerno.

Another description, provided later on by Aldo Sestini in 1963, seems to specifically

highlight the essential traits of the landscape surrounding the fjord of Crapolla, which

appears as an epitome of landscape in the whole peninsula:

The ridges of limestone and dolomite that drop down from the Lattari mountains,

often with irregular lines, break through large terraces over the dark blue of the

Tirrenian Sea. They form many steep nesses, like different following scenes, among

which wild gorges flow to the sea or small beaches stretch, where the fishermen

pull up multi-coloured boats10.

There are only two sites in the entire Amalfi Coast, from Punta della Campanella to

Salerno, that display all the above mentioned characteristics: the fjords of Furore and

Crapolla.

On a geomorphologic level, the peninsula area, «based on the complex of the Lattari

mountains, provides an example of extremely complicated and asymmetrical orography,

42

7. See P. D’Angelo, Estetica della natura, cit., p. 163.8. For the historical aspects of landscapes, see C. Tosco, Il paesaggio come storia, Il Mulino, Bologna 2007.9. G. Piovene, Viaggio in Italia, (I edit. Mondadori 1958), Baldini & Castoldi, Milano 2003, p. 475.10. A. Sestini, Conosci l’Italia. Il Paesaggio, Touring Club Italiano, Milano 1963, p. 147.

LANDSCAPE AS ARCHITECTURE

which bears the marks of a remote hydrography and an equally ancient erosion»11. From

the geological point of view, as it is well known, the Sorrento peninsula is mainly compo-

sed of a calcareous blocks dating back to the Cretaceous-Miocene age, followed upwards

by an arenaceous complex12.

The area of the Crapolla fjord, corresponding to a fault, is generally composed of a

limestone complex, with dolomite rocks particularly evident at the highest altitudes of the

walls of the gorge. The latter presents Karst caves on both sides, some of which are very

large and deep and would deserve appropriate investigation to detect possible traces of

prehistoric human settlements. The analysis of the geological map also shows the presen-

ce of a small area corresponding to an ancient flood, located between 100 and 200 meters

on the eastern side and an outcrop of sandstone on the area of the village of Torca.

From the geographical point of view, the fjord of Crapolla is located about two miles

East of the extreme offshoot of the Sorrento peninsula, named Punta della Campanella,

known as Athenaion during the ancient times due to the presence of the sanctuary of

Athena, which will be discussed later. The fjord is therefore located on the southern end of

the peninsula. It is morphologically and scenically very different from the northern side,

where the two towns of Sorrento and Massa Lubrense are. Unlike the areas just mentioned,

here the landscape is characterised by far more extreme conditions, which have always

made human settlements particularly difficult: steep or sheer slopes, deep water with

Fig. 1

Crapolla. View of the fjord

and the gorge from south,

about half a mile away from

the coast.

43

11. Piano Territoriale di Coordinamento e Piano Paesistico dell’area Sorrentino – Amalfitana. Proposta, workgroupformed by R. Pane, L. Piccinato, G. Muzzillo, A. Dal Piaz, A. Filangieri, G. Vitolo, G. Gallo, A. Marsiglia, G.Francese, reprint by Italia Nostra and Istituto Italiano per gli Studi Filosofici, Napoli 2007, p. 26.

12. M. Civita, R. de Riso, P. Lucini, E. Nota d’Elogio, Studio delle condizioni di stabilità dei terreni della penisola sor-rentina (Campania), in «Geologia applicata e idrogeologia», vol. X, part I, Bari 1975, pp. 134-138.

1

almost no beaches, and difficult access to the sea from the hills.

However, the stretch of coast between Punta della Campanella and the

Crapolla fjord is an exception compared to what has been described

above, mainly because of the presence of a long beach called Marina

del Cantone located between the headlands of Montalto and

Recommone.

Continuing eastwards, after the headland of Recommone and pas-

sing the island of Isca, one can see a deep gorge in the rock, whose

access by the sea can be seen only when getting very close to the coast.

It reveals a true fjord with tall side walls, which penetrates from the

north to the south for more than 50 meters from the outer coastline.

Entering the fjord, visitors reach a small beach, on the side of which

there are some masonry vaulted buildings, used as shelters for boats

and fishermen. On the right side there is a water channeling system,

which feeds the Iarito (or Viarito) river − or better the brook − into the

sea. It is originated from the above hamlet of Torca (and invisible from

the beach). Higher up, on the right side, one can immediately detect

the presence of structures from the Roman period, with sections in

opus reticulatum and partially collapsed vaults. Here, a long staircase

with steps in limestone climbs up and after a few bends it leads to a

natural terrace located at the mouth of the fjord, directly overlooking

the islands of Isca, Vetara on its eastern side and Li Galli from far away,

south-east. Here there are the ruins of the religious complex of the

Benedictine Abbey of Saint Peter in Crapolla.

As will be discussed later, the very special character of the site has always fascinated

travelers and writers, as well as archaeologists such as Mingazzini and Pfister, who first

studied the structures of the fjord in the twentieth century. In 1946, Pfister wrote: «The

marina of Crapolla lies at the bottom of a narrow creek enclosed by rocks overhanging

cliffs, which gives the bank a horridly picturesque image»13. The image of a «marine maw»

is found also in Amedeo Maiuri’s pages, who carefully visited the site in 1949, noting how

Crapolla was «the deepest crack into the compact wall of the coast, along with the fjord

of Furore»14.

The parallel with Furore is particularly important, since even the latter, much wider and

deeper, has a marina with fishermen houses, though more architecturally articulated and

complex than those of Crapolla. Moreover, the theme of fjords and gorges is quite common

in the landscape of the Sorrento peninsula, although only in the case of Crapolla and Furore

they are associated with such an intense relationship between nature and architecture. An

interesting example is the inlet of Portiglione, less than a quarter of a mile from Crapolla,

devoid of artifacts and located almost in front of the islet of Isca, less deep than Crapolla

44

13. P. Mingazzini, F. Pfister, Formae Italiae. Regio I Latium et Campania, vol. II, Surrentum, Sansoni, Firenze 1946,p. 157.

14. A. Maiuri, La capitale degli agrumi e la capitale degli ulivi. Variazoni sul “tema” dai taccuini inediti, in Id.,Passeggiate sorrentine, B. Iezzi ed., Franco di Mauro, Sorrento 1990, p. 86.

LANDSCAPE AS ARCHITECTURE

Fig. 2

Crapolla. View of the Viarito

River’s water jetty, at the

bottom of the gorge, one of

the main characters of the

site and one of the reasons

for its continuous use over

the centuries.

2

but also characterised by the presence of a rivulet of water. It

is also worth mentioning two additional tiny inlets, located

just to the west side, corresponding to the two rivulets

Scrivanessa and Comunaglia, as evidenced by the carto-

graphic references of the Military Geographic Institute.

As previously mentioned, the fjord is closely related to

the overlying settlement of Torca, although separated by a

vertical drop of over 300 meters. It is its natural outlet to the

sea, thus giving the small village the character of a hamlet of

«fishermen who live in the mountains», similarly to other

coastal towns. Already in ancient times, fishing was accom-

panied by agricultural and pastoral activities, though now

these are barely visible. According to Maiuri, the very origin

of the name of Torca seems to recall the ancient presence of

olive trees, which have almost disappeared today15.

Today the landscape surrounding the fjord of Crapolla is

mostly bare and characterised only by Mediterranean scrub

and bushes, with a few isolated trees at higher altitudes

where, according to several witnesses, once dwelt an oak

forest, while lower below there were olive trees and carobs16.

In the fields surrounding the fjord there are no traces of ter-

races, which are rather evident on the nearby fjord of

Portiglione. At the beach level, the vegetation at the bottom

of the gorge is quite different. Here, the presence of fresh

water from the Iarito brook, which forms a small waterfall, has allowed the formation of a

much more dense vegetation, with a few trees of high stalk. This is also due to the greater

distance from the sea and shady conditions for several hours a day.

The use of the site over the centuries

Since ancient times, the fjord of Crapolla has been destined to a variety of uses. This is

what makes the term “cultural landscape” more than appropriate for this site. It is not easy

to summarize millennial and articulate events in a few lines, but wanting to single out the

most important aspects, we must start from the mythological theme, linked to the cult of

the Sirens.

As is well known, the most famous and solemn reference to the myth of the Sirens is

found in the Odyssey, already introduced by the words that Circe says to Ulysses departing

from the island of Eea, which has been traditionally connected to the island of Ponza17. The

45

CRAPOLLA: A CULTURAL LANDSCAPE ON THE AMALFI COAST

15. Ibidem, p. 89.16. Ibid., p. 86.17. «First you will come to the Sirens who enchant all who come near them. If anyone unwarily draws in too

close and hears the singing of the Sirens, his wife and children will never welcome him home again, for theysit in a green field and warble him to death with the sweetness of their song. There is a great heap of deadmen's bones lying all around, with the flesh still rotting off them» (Homer, Odyssey, XII, 36-45, publicdomain).

Fig. 3

Sorrento Peninsula, detail of

Sorrento and Massa in the

Aragonese Maps of

Principato Citra, second half

of fifteenth century (BNF,

Cartes et Plans, GE AA 1305-

5, published in F. La Greca,

V. Valerio, Paesaggio antico

e medioevale nelle mappe

aragonesi di Giovanni

Pontano. Le terre del

Principato Citra,

Acciaroli 2008).

3

presence of the cult of the Syrens in the Sorrento peninsula and the identification of the

islands of the Sirens with the islands of Li Galli is subsequently confirmed by Strabo in The

Geography. In his work, following the detailed delineation of the Crater (the bay between

Cape Miseno and the Athenaion, today Punta della Campanella), the sites are described as

follows:

Next after Pompaia comes Surrentum, a city of the Campani, whence the

Athenaeum juts forth into the sea, which some call the Cape of the Sirenussae.

There is a sanctuary of Athene, built by Odysseus, on the tip of the Cape. It is only a

short voyage from here across to the island of Capreae; and after doubling the cape

you come to desert, rocky isles, which are called the Sirens18.

Actually, the controversial location of the temple of the Sirens has given rise to much

debate19, which is still unresolved, although recent studies seem to confirm its presence in

the bay of Ieranto20. Whatever the exact location of the temple is − probably impossible to

circumscribe − the close proximity of the fjord of Crapolla with the area of the Sirens’ wor-

ship is particularly evident, even more so when we consider the direct relationship between

the fjord and the Sirenuse islands.

Little is known about the prehistoric anthropization of the peninsula, although

Amedeo Maiuri considered that «the whole Amalfi coast, extraordinarily rich in recesses,

caves, easily reachable landing and sheltering shores, spring waters and forests, must have

been inhabited since prehistoric times»21. However, the Sorrento peninsula has had a fun-

damental role since ancient times, due to its geographical location and its key position in

the maritime trade of the Tyrrhenian coast. Not surprisingly, in the famous Tabula

46

18. Strabo, The Geography. Italy, V, 8, public domain.19. In the first book of his work, Strabo himself wrote something different about the location of the temple:

«(Eratostene says) that some of them put the Sirens on Cape Pelorias, while others put them more than twothousand stadia distant on the Sirenussae, which is the name given to a three-peaked rock that separatesthe Gulf of Cumae from the Gulf of Poseidonia. But neither does this rock have three peaks, nor does it runup into a peak at all; instead it is a sort of elbow that juts out, long and narrow, from the territory ofSurrentum to the Strait of Capreae, with the sanctuary of the Sirens on one side of the hilly headland, whileon the other side, looking towards the Gulf of Poseidonia, lie three uninhabited rocky little islands, calledthe Sirens, and on the Strait of Capreae itself is situated the sanctuary of Athene, from which the elbowtakes its name» (Strabo, The Geography. Italy, I, 2, public domain, quoted also in P. Mingazzini, F. Pfister,Formae Italiae, cit., p. 45). This last observation has led Mingazzini e Pfister to imagine the location of theSirens’ worship in the Ieranto bay, definitely overcoming the opinion by Beloch, who thought more proba-bly the location of the temple near Marina della Lobra, recalling the toponym “de-lubrum” (J. Beloch,Campanien. Geschichte und Topographie des antiken Neapel und seiner Umgebung, Breslau 1890; Ital. transl.Campania. Storia e topografia della Napoli antica e dei suoi dintorni, C. Ferone and F. Pugliese Carratelli eds.,Bibliopolis, Napoli 1989, p. 312). The hypothesis proposed by Mingazzini-Pfister was discussed by A. Maiuri,Surrentum, review to P. Mingazzini, F. Pfister, Formae Italiae, cit., in «La parola del passato», vol. I, 1946, pp.391-394, now in Id., Passeggiate sorrentine, cit., p. 53.

20. Later on Bonghi Iovino has highlighted that the description which Strabo’s wanted to refute seems to coin-cide with the “three tops” that end still today the Ieranto bay towards East, confirming therefore its truth-fulness (M. Bonghi Iovino, Mitici approdi e paesaggi culturali. La penisola sorrentina prima di Roma, NicolaLongobardi editore, Castellammare di Stabia 2008, pp. 31-33).

21. A. Maiuri, Le vicende dei monumenti antichi della costa amalfitana e sorrentina alla luce delle recenti alluvioni,in «Rendiconti dell’Accademia di Archeologia Lettere e Belle Arti di Napoli», vol. XXIX, 1955, now in Id.,Passeggiate sorrentine, cit., p. 57.

LANDSCAPE AS ARCHITECTURE

Peutingeriana – a medieval copy of a Roman map, likely attributable to Agrippa – the

peninsula is drawn with accuracy and well-situated as a watershed between the Gulf of

Naples and Salerno22.

It has been often observed that the geological and geomorphological features that

qualify the Peninsula – making it undoubtedly one of the most important landscapes in

Campania – constitute a substantial part of the identity of this area, with very significant

reflections regarding the history of its uses. The very presence of the promontory of Punta

della Campanella, or Athenaion, was undoubtedly an element of great importance for

navigation, and it introduced the sailors to the great Crater mentioned by Strabo23. Thus,

in this sense, the close proximity of the Crapolla fjord to the headland lent itself well to

quick stops, before tackling the difficult sailing through the “small mouth” (Bocca piccola)

of Capri24.

Moreover, the natural vocation of the fjord as a harbour is evident at first glance. Due

to its sinuous shape, with a slight curve to the north-west, the creek is totally protected

from the northern winds (Mistral, North, North-West winds), which are prevalent in the

medium Tyrrhenian. Thus, the fjord is configured as an extraordinary natural port, protec-

ted and well hidden. On the contrary, its opening to the south makes the fjord very expo-

sed to southern winds, frequent in the case of storms. However, this condition is balanced

by the presence of the beach, which certainly allowed the rapid and safe putting up of the

boats.

Mingazzini and Pfister’s archaeological research, supported by Maiuri’s reflections, has

highlighted its character of a home port, used to supply the Roman villas located on the

island of Isca and the islands of Sirenuse. In particular, according to Maiuri, «the Crapolla

Marina seems to be placed just there to serve as a place of landing or embarkation for the

islands of the Sirens»25. Certainly, the presence of the water coming from the Iarito brook

was an inestimable added value to supply the villas but also, more generally, for all navi-

gation between the Gulf of Naples and Salerno.

Little is known about the sudden interruption of the use of the site in the Early Middle

ages, which Maiuri considered due to a natural extraordinary event, such as a flood, able to

erase any sign of Roman settlements from all over the Amalfi coast, though documented

by multiple sources. According to Maiuri, this stage was followed by a repopulation pro-

cess that began in the caves again, as happened during the primitive era, but this time with

the presence of monks, hermits, and then religious settlements, which started to return to

the mountains. This resulted in a dual and ambiguous relationship between the inhabi-

tants of the coast and of the hilly areas, in a «life of the mountains and of a life of the sea».

In some way, this phenomenon survives even today, which undoubtedly marks the identity

47

CRAPOLLA: A CULTURAL LANDSCAPE ON THE AMALFI COAST

22. M. Bonghi Iovino, Mitici approdi e paesaggi, cit., p. 14.23. «We know well that the role of the headlands was important because they served as reference points. The

ancients had the perception of distances and sailing times» (ibid., p. 36). On the relevance of the water sour-ces for sailing see also F. Russo, Le torri anticorsare vicereali con particolare riferimento a quelle della costacampana, in «Castella», n. 74, Istituto Italiano dei Castelli, Piedimonte Matese 2001.

24. M. Bonghi Iovino, Mitici approdi e paesaggi, cit., p. 37.25. A. Maiuri, La capitale degli agrumi, cit., p. 88.

of the Amalfi coast landscape26. The landscape that marks the fjord of Crapolla in this

period – during which the first nucleus of the Benedictine Abbey of St. Peter was probably

built – seems to recall the characteristics of the medieval Italian landscape, well illustrated

by Emilio Sereni since 1961. This is what he called the «village perched on the agricultural-

pastoral landscape of the Italian Middle Ages»27, attributed to the need for defense again-

st barbarian invasions and raids, which is particularly suitable to describe the living envi-

ronment of Torca and its relationship with its pastoral and agricultural hills sloping down

to the sea.

Therefore, as mentioned above, the Abbey marks the use of the site for ages after the

twelfth century, when, according to Filangieri, there is the first evidence of the religious

settlement, which in 1111 state the existence of a monastery called Capreolae in the terri-

tory of Massa28. The name of Crapolla itself deserves some reflections. Some attribute it to

the Greek ’'ATYWV 'AXóUU[VWZ, related to a cliff sacred to Apollo, so that historian Julius

Beloch quoted that origin for the name of Crapolla in 189029. For Maiuri, however, the

name stems from the

Fishermen’s mouths; Crapolla as already Capaccio thought of Crapeolae, with the

metathesis of Capri in Crapa (while) the etymology which the scholars of the eigh-

teenth century came up with, assuming an Akra Apollonos, only witnesses the inven-

tive acuity of some good Neapolitan philologist of the 18th century, stimulated by

the near Promontorium Minervae30.

Returning to the abbey, in spite of the aforementioned documentary evidence of 1111,

it should be noted that no mention of the religious complex, or landing, can be found in

one of the most detailed geographical descriptions of the Middle Ages that have survived,

the one by Edrisi (or al-Idrisi), a plenipotentiary of the Norman king Roger II, author of the

Book of King Roger, written between 1139 and 1154 in Arabic31. In fact, after a long descrip-

tion of Sorrento and a note to the headland of Minerva, the text directly passes to refe-

rence to the next port of Positano32.

48

26. A. Maiuri, Le vicende dei monumenti antichi, cit., pp. 71-72.27. E. Sereni, Storia del paesaggio agrario italiano, Laterza, Roma-Bari 1961, 19723.28. R. Filangieri di Candida, Storia dei Massa Lubrense, Napoli 1910 (reprint Napoli 1991), p. 647.29. J. Beloch, Campanien, cit., p. 314.30. A. Maiuri, La capitale degli agrumi, cit., p. 88.31. The original title of the work, commonly known as Geography or “The Book of King Roger”, was Opus geo-

graphicum, sive Liber ad eorum delectationem qui terras peragrare studeant, edited today in integral versionby the University of Naples “L’Orientale”.

32. «E chi si propone [di andare ad Amalfi lungo] il litorale, va costeggiando da Stabia alla città di surr.nt(Sorrento) per trenta miglia. Sorrento giace su di una punta di terra che si protende in mare; è città popola-ta, con belle case, ricca di prodotti e d’alberi. Ha vicino un canale di difficile accesso, nel quale, durante l’in-verno, le navi non possono [entrare a] gettar l’ancora, ma vi sono rimorchiate. Vi si costruiscono navigli.Dalla città di Sorrento al râs m.ntîrah (Capo Minerva, oggi Punta della Campanella) dodici miglia. Da questaa b.s.tânah (Positano), piccolo porto, quindici miglia» (Edrisi (al-Idrisi), L’Italia descritta nel “Libro del reRuggero”, Arabic text published with version and notes by M. Amari and C. Schiaparelli, Tip. Salviucci, Roma1883, pp. 95-96).

LANDSCAPE AS ARCHITECTURE

We need to wait until the first half of the 16th century to find a more ample descrip-

tion of the site of Crapolla by Theophilus Folengo, who spent about three years in the

abbey of St. Peter with his brother. In fact, revealing unusual landscape accents, around

1533, he wrote the following words:

Crisogono: To satisfy your curiosity, I will talk about Caprolla again. However, I

would call it more willingly Caprona, like mane that that goes down from a head.

This is how they interpret this name. Raise your eyes for a moment, please, from the

bottom of this hill, step by step, to the top edge of the mountain and look careful-

ly if you can imagine something else that is more similar. Watch that steep ridge

that protrudes from the top, like a human face, a gentle face. From that ridge to the

fence of the houses, on a gentler slope, they spread through as on a man’s face, for-

ming a beautiful mane; olive trees first and then a myrtle grove growing intertwined

with a variety of shrubs. Then there is the mountain, leaning a little in itself, crea-

ting a really pleasant depression and fertile plains, where there are beautiful houses

and fields, covered with the green of the olive trees again. From there, a steep pro-

montory opens, which suddenly runs down to the cavernous beach. This, jagged and

sinuous on both sides, causes frightening sounds because of the continuous clash of

waves33.

Still at the beginning of the 18th century, in Parrino’s guide, the site is mentioned as a

sort of landing jetty, a «little port, where many boats come together on Easter day, then

they have a rich fishing and then they go back singing litanies»34. However, a century later,

with the final suppression of the abbey and the destruction that occurred during the

Napoleonic wars, the site was only relegated to fishing, as evidenced by Mariana Starke’s

1836 description, in which the ruins of the abbey, though abandoned, are still visible, while

the fjord is referred to as a «port daily used by the fishermen of Sant'Agata providing the

fish market of Naples»35.

From the end of the 19th century, we can find many literary references of travelers and

writers who paid more attention to the landscape of the peninsula, among which, Francis

Marion Crawford and Norman Douglas, at different intervals. Both contributed to associa-

te the myth of the Sirens to the fjord of Crapolla, and collected further evidence and

legends about the site, which gave a varied and complex framework, focussing – for the

first time – on the fishermen’s activities. Thus, in his famous Coasting by Sorrento and

Amalfi, published in an American magazine in 1894, Crawford describes the hidden aspects

49

CRAPOLLA: A CULTURAL LANDSCAPE ON THE AMALFI COAST

33. Ioan. Bapti. Chrysogoni Folengii Mantuani Anachoritate Dialogi..., [1533], ital. ed. by C.F. Goffis, Torino 1958,also in E. Puglia, Due eremiti nella Terra delle Sirene: Giambattista Folengo, Pomilio XIII, in «La Terra delleSirene», 2, 1980, pp. 40-41.

34. D.A. Parrino, Nuova guida de' forastieri per l'antichità curiosissime di Puzzuoli..., [Della città di MassaLubrense e dell'antico Ateneo, o Capo di Minerva], in Napoli presso Domenico Antonio Parrino, 1715, vol. II,p. 255.

35. M. Starke, Travels in Europe for the use of travellers on the Continent, and likewise in the Island of Sicily: wherethe Author had never been, till the year 1834..., Paris 1836.

of the fjord, referring the practice of quail hunting

with hand-nets on the heights, which led to many

violent deaths:

Then rocks again, and then the hidden gorge of

Crapolla, scarcely distinguishable from the sea,

an abrupt and almost perpendicular cleft in the

enormous rock wall facing the Isles of the Sirens.

There are ghosts, too, in plenty, of men and boys

who, in the pursuit of quails with hand-nets, have

fallen some fifteen hundred feet to the bottom of

the gorge36.

Crawford also introduces the issue of fishermen

for the first time, described as night visitors of the

fjord, who «descend from Sant’Agata at night and

most of them go back in the morning, taking with

them what they have caught to the market there».

Among these, there is the character of Garibaldi,

who spends most of the year in the fjord: «Here also

lives a solitary old man, a sort of familiar spirit of the

place, nicknamed Garibaldi for his supposed resem-

blance to the national hero (...) [who] gets a pretty

fair livelihood by setting night-lines, with which he

catches the big bass so highly prized in Naples»37.

The character of “Garibaldi” returns in more detail

also in Norman Douglas’ famous Siren Land, publi-

shed in 1911, where he states that «no one knows better how to catch the wary cernia as it

lies hidden among the rocks». In Douglas’ description, night fishing is only for summerti-

me: «In wintertime, Crapolla is uninhabited; the boats are drawn up out of reach of the

waves which thunder in between the encircling precipices» and only old Garibaldi «lives

here throughout this wild season»38.

However, the mythological and landscape-related aspects turn out to be particularly

effective in Douglas’ work. He devotes an entire chapter to the Cove of Crapolla, defined as

«one of the quaintest spots in Siren Land». The text summarizes many of the elements of

landscape value that still strike visitors today, along with brief historical notes that discuss

the evolution of the use of the land, as well as a note to the presence of oak trees, which

Fig. 4

First page of F. M. Crawford,

Coasting by Sorrento and

Amalfi, in «The Century

Magazine», vol. 48, n. 3,

July 1894.

50

36. F.M. Crawford, Coasting by Sorrento and Amalfi, in «The Century Magazine», 48, 3, July 1894, pp. 325-336;ital. translation In barca a vela da Sorrento ad Amalfi ed altre storie, A. Contenti ed., Edizioni La Conchiglia,Capri 2004, pp. 33-34.

37. Ibid., p. 34.38. N. Douglas, Siren Land, London-New York 1911; ital. translation La terra delle Sirene, ESI, Napoli 1972; Edizioni

La Conchiglia, Capri 2002, p. 134. All the quotations here are taken from the original English text.

LANDSCAPE AS ARCHITECTURE

4

were still recognizable in those days in scattered groups along the slopes:

One of the quaintest spots in Siren Land is the inlet of Crapolla on the south coast.

A rugged path, frequented by fishermen who bring their produce over the ridge to

Sorrento and by a few bathing enthusiasts of Sant'Agata, leads down the incline,

becoming more precipitous as it breaks away, perforce, from the stream which

flows alongside, and which ends in a cascade at the back of the inlet. This is no walk

for a summer morning when the glare from the shameless limestone rock is terrific,

and one wonders how those old monks who lived in the abbey of San Pietro di

Crapolla close by the sea were able to endure it. Likely enough, the road was shaded

in those days by oaks, single groups of which may still be seen along this slope in iso-

lated spots39.

But it is perhaps the night description of the site, placed by Douglas at the end of the

chapter, that better expresses the spirit of Crapolla, part of which still survive for all those

who come today to the fjord:

On a night of full moon, for all discords dissolve in the mellow sheen of a Southern

night (…). At such an hour the twin rocks guarding the entrance to Crapolla might

well be mistaken for the portal of some Ossianic realm (…). It is a picture that you

see, not a palpable cliff of limestone; a picture that floats past you; some enormous,

silver-tinted cartoon conceived by William Blake, in the mad moments betwixt sleep

and waking40.

After Douglas’ fascinating pages, a long description of Crapolla with literature accents

is due to the aforementioned Maiuri, in his book Passeggiate Campane, where he alterna-

tes archaeological reflections with careful observations about the character of the land-

scape, its uses by the inhabitants of Torca, the fishermen’s customs, providing a lively fra-

mework of the fjord in 1949. The most interesting pages are dedicated to the access trail

from Torca:

From the land you can reach it almost sliding down headlong from the last houses

of Sant’Agata through a valley that once had to be a big oak wood with a few scat-

tered farmhouses and today sparse olive groves and glades of scarcely sown fields.

The last two-hundred meters from the edge of the cliff and the sea seem to disper-

se in rocky steps that compete with the Phoenician steps of Anacapri (...) the steps

and the terraces of rock are so shiny and worn that they make you think of the con-

sumption that only the bare feet of the fishermen who go up and down with the

loads of fish can do41.

51

CRAPOLLA: A CULTURAL LANDSCAPE ON THE AMALFI COAST

39. Ibid., p. 133.40. Ibid., pp. 153-154.41. A. Maiuri, La capitale degli agrumi, cit., pp. 86-87.

Similarly, Maiuri describes the access to the fjord by the sea, revealing feelings still lar-

gely perceived by the contemporary visitor:

Today one enters the Bay of Crapolla above a sea of turquoise and opal between two

rock walls that close down in an inaccessible gully amid a tangle of weeds. No pier

or landing stage, keels run aground in the gravel with a metallic rustle and the boats

are pulled out of the water onto the shore one after the other. They are the most

brilliant and happy thing in that shady cave42.

Finally, Maiuri’s reflections also help better define the specific aspects of the fishing

activity in the fjord, summarised by an effective expression: «Neither women nor family: a

Crapolla fisherman’s life is still like one’s of the survivors of the islands of the Sirens. They

go fishing at night, and then they sleep at dawn»43.

Some evocative pictures of fishing also appear in short frames taken from the docu-

mentary Miti e paesaggi della penisola sorrentina (Myths and Landscapes of Sorrento

Peninsula) directed in 1955 by Roberto Pane, shot in close relation to his volume Sorrento e

Fig. 5

Crapolla. The beach with the

small wooden boats of the

fishermen, in a photo taken

in the early 1950s by Roberto

Pane for his book Sorrento e

la costa, 1955 (R. Pane

Photo Fund, University of

Naples Federico II).

52

42. Ibid., p. 91.43. Ibidem.

LANDSCAPE AS ARCHITECTURE

5

la costa, published in the same year. The film shows the beach entirely occupied by rowing

fishing boats, all made in wood, with some men intent to order their equipment. As

regards the instruments used for fishing and the preys, in 1949 Maiuri signaled the risk of

depletion of fish in Crapolla, due to the careless use of dynamite44.

The most recent evidence of the surviving fishermen in Crapolla, all resident in Torca,

emerges from Antonino de Angelis’ recent book entitled Contatti (Contacts, 2003), which

describes a «beach only frequented at night», while during the day, «the fishermen are

away from the shore, intent to treat olives and hoe their vineyards»45. A quick note, at the

end, about the fish of Crapolla, drawn from eyewitness accounts of the last fishermen. If

Crawford mentions the «perches» and Douglas the «groupers» (in Italian cernia), it is also

important to mention St. Peter’s fishes among the most famous and abundant preys,

whose name recalls the homonymous Benedictine abbey. By the way, the same fish is com-

monly called in Italian pesce gallo, suggesting further and curious similarity with the

toponym Li Galli.

The fiord of Crapolla in planning and protection regulations

Before ending this short description of the many issues regarding the site of Crapolla

intended as a cultural landscape, it is necessary to highlight the present regulations in

planning and protection that affect the whole area. Generally, we can say that the regula-

tory framework concerning the fjord of Crapolla is rather complex, at both urban-landsca-

pe and environmental level. On the contrary, the protection of cultural heritage is much

attenuated, and there are no specific regulations for the architectural heritage in Crapolla.

Proceeding in hierarchical order, the largest legal instrument that covers the whole

area is the Piano Urbanistico Territoriale della Penisola Sorrentino – Amalfitana, drawn up in

the early 1970s by a study group led by Roberto Pane and Luigi Piccinato and approved, with

substantial variations compared to the original, with a Regional Act in 1987. In the defini-

tion of this plan, called PUT, the fjord of Crapolla is included as part of the landscape

«marked by dominant tectonic morphology» in which «for the observer, the aforementio-

ned geological structures presents a dominating importance compared to rear insertions

of natural vegetation and agricultural and human settlements»46.

Therefore, the geological and tectonic elements, classified as “erosion” in the specific

case of Crapolla, are the prevailing elements in the system for the protection of the land-

scape:

These landscapes, regardless of their aesthetic value, witness to aparticular phases

of formation of the Earth’s surface, and as such they should be preserved in their ori-

ginal conditions. No intervention, even of simple reforestation can find justification

for these environments, because it would alter their documentary function47.

53

CRAPOLLA: A CULTURAL LANDSCAPE ON THE AMALFI COAST

44. Ibid., p. 96.45. A. de Angelis, Contatti. Persone e personaggi nella terra delle sirene, Edizioni La Conchiglia, Capri 2003, pp.

48-49.46. Piano Territoriale di Coordinamento e Piano Paesistico dell’area Sorrentino – Amalfitana, cit., pp. 63-64.47. Ibid., p. 100.

It therefore follows that the entire stretch of coast that includes the fiord of Crapolla

is included into the “Territorial Zone 1A − Protection of the natural environment − first

degree”. The plan reserves the utmost discipline of protection of the natural environment

to this area, particularly relevant considering the presence of «major tectonic and morpho-

logical emergencies that occur mainly with rock outcrops or sometimes natural vegeta-

tion». The boundaries of the area follow the outline of the Iarito brook, penetrating a few

hundred meters within the «Territorial Zone 1B - Protection of the natural environment -

2nd degree».

The regulations just mentioned have been fully transposed into the town plan of Massa

Lubrense, designed by a group including authoritative members such as Guido Clemente,

Alessandro Dal Piaz and Arrigo Marsiglia in 1992. The zoning plan for the area of the fjord

follows the perimeter of the Territorial Zone 1A of the PUT, assigning it to the E1 area «pro-

tection of the natural environment - first degree»48.

Fig. 6

Crapolla. View of the

entrance of the fjord from

the tower’s path towards

west. In the distance, the

islet of Isca and the “Tre

Pizzi” in the background.

54

48. By prohibiting any earthwork or changing of the current agricultural settlement, they are allowed, «theordinary and extraordinary maintenance and restoration of conservative buildings documented as existingin 1955, the reconstruction of dry stone walls of local limestone in support of terraces with height not excee-ding 1.5 meters and width not less than 2.5 meters, the system of trees and shrubs not contrast to the tra-ditional local flora green spaces pertaining to existing residences, the compositional organization of whichcannot be changed. It is compulsory the conservation of natural vegetation and the accommodation, main-tenance or restoration of footpaths that allow public access to the sea or scenic places or courses of brooksand environmental areas attached, as shown in the plans» (art. 39 of Norme Tecniche di Attuazione del PianoRegolatore Generale di Massa Lubrense, approved by Decree of the President of the District of Naples on 21May 1992).

LANDSCAPE AS ARCHITECTURE

6

Finally, we have to mention that the fjord is included, for most of its length, among the

landscape assets protected ipso jure by the Cultural Heritage and Landscape Code, Article

142, which incorporates what was provided by the so called Galasso law (n. 431) in 1985. In

fact, the area of Crapolla is almost entirely comprised within 300 meters from the shore

line49. Therefore, in addition to the rules imposed by the PUT, it configures a specific land-

scape restriction for all the parts included within the cited range of 300 meters.

The last aspect in chronological order, though very relevant for the protection and

enhancement of the fjord, is related to the issue of the protection of the marine environ-

ment and, in particular, to the discipline imposed by the Regulations of the Protected

Marine Area of Punta Campanella (approved by Decree of the Ministry of the Environment

in December 1997), in which the whole area of Crapolla rests entirely for all its shoreline.

More specifically, the Protected Marine Area applies, in addition to sea waters, even to the

«coastal areas belonging to the maritime domain»50. It follows that, for the specific case

of Crapolla, the Protected Marine Area also regulates the stretch of the beach and the sea

Fig. 7

Crapolla. View of the beach

and the masonry vaulted

buildings, used as shelters

for boats and fishermen.

55

CRAPOLLA: A CULTURAL LANDSCAPE ON THE AMALFI COAST

49. «They are however of scenic interest and are subject to the provisions of this title: a) the coastal areas inclu-ded in a range of depth of 300 meters from the shore line, even for the high land on the sea» (Art. 142comma 1 of the Codice dei Beni Culturali e del Paesaggio, D. Lgs. 22 January 2004 n. 42 and following upda-tes, which confirms the regulations of art. 1 L. 8 August 1985 n. 431).

50. The maritime domain is defined by art. 28 of the Codice della Navigazione (Navigation Code): «They are partof the maritime domain: a) the shore, the beach, ports, bays, b) the lagoons, the mouths of the rivers thatflow into the sea, and the basins of salt water or brackish water that at least part of the year shall freelywith the sea, c) channels can be used for public use maritime».

7

in the outlet of the Iarito brook. In the Regulations, the entire area of the fiord of Crapolla

is included in the B2 zone of general reserve, including the Scruopolo rock to the west of

the Matera cave, which only allows the «transit of motor boats with a maximum length of

7.50 meters if motorboat or 10 meters if sailing boat». Finally, at the edge of the area, the

Regulation provides an area for mooring buoys, called “Isca”. The access arrangements and

the activities permitted in the fjord of Crapolla are subject to a specific article of the

Regulation, concerning the fiord and Ieranto Bay51.

Conclusion

The brief framework outlined above shows how appropriate the definition of “cultural

landscape complex” is for the fjord of Crapolla. The aspects involved (spatial, morphologi-

cal, natural, historical, literary, symbolic) are so varied that any conservation project

should be carefully examined in order not to favour or 'single out' any of these aspects, as

their close connection finds expression in the site itself. The fact that those aspects are clo-

sely intertwined is immediately perceived when approaching the fjord, whether by boat, or

walking down the stone steps from the hill of Torca. A richness of signs and suggestions

that requires a certain sensibility to be perceived and understood. The final result is a soul-

gripping site at the heart of a sustainable project.

Fig. 8

Crapolla. View from

St. Peter’s Abbey towards

south-east, with the tower

and the three islets named

Li Galli on the left and the

islet of Vetara on the right.

56

51. «Access to Ieranto Bay and Fjord of Crapolla is allowed to service units, commercial fishing and units enga-ged in activities of guided tours diving. Access to the fjord Crapolla is in the hallway UNO and is permittedonly to craft legitimately in storage existing prior authorization from the Entity Manager. It is permitted toland in the beaches of the Bay of Ieranto and Fjord of Crapolla for visits of natural interest to a maximumof 100 people per day divided into groups of no more than 25 units. It is forbidden the sale of food and beve-rages» (art. 39 of the Regulations of AMP Punta della Campanella, approved by Decree of the Ministry ofEnvironment on 12 December 1997).

CRAPOLLA: A CULTURAL LANDSCAPE ON THE AMALFI COAST

8

379

ITALIAN SUMMARIES

mano dell’uomo può avere modificato l’assetto originario determinan-do una nuova configurazione e quindi un nuovo equilibrio tra natura einsediamenti dallo stesso realizzati. Per conservare tale equilibrio ènecessario un continuo lavoro di manutenzione delle testimonianzelasciate nel corso dei secoli per evitare che deperiscano. Mentre per ilpassato le aggiunte di opere architettoniche erano discrete e dialogava-no con la natura, integrandosi con essa, negli ultimi anni si è assistitoalla realizzazione di interventi molto più invasivi per cui non ci trovia-mo solo a dovere affrontare problemi di tutela e conservazione, maperfino di “restauro” del paesaggio. Per concludere, nell’area di Crapolla, a valle del casale di Torca, nelcorso dei secoli si è assistito ad una spontanea stratificazione cherispondeva ad un particolare tipo di vita in comune, prevalentementedi pescatori. Qualora oggi si volesse proporre di considerare l’areacome un “museo diffuso”, si dovranno coinvolgere in modo imprescin-dibile le comunità locali, prime depositarie della memoria e della cultu-ra materiale dei luoghi, nei quali si sono accumulate tracce storiche,più o meno decifrabili, tradizioni, culti, mestieri e volontà di adatta-mento nel tempo ad un territorio morfologicamente difficile. Gli studiche sono stati condotti hanno avuto lo scopo non solo di produrrerisultati scientifici con indagini dirette sui manufatti che ricadono nel-l’area di Crapolla, ma anche di sensibilizzare le comunità locali e ren-derle consapevoli che saranno loro a dover difendere questi beni cheappartengono all’intera umanità e di cui loro sono depositarie. La dife-sa di questi beni sarà più facilmente realizzabile se le comunità locali sirenderanno conto che la loro conservazione potrà produrre ricaduteeconomiche per la collettività, vale a dire che ai costi che questa dovràsostenere corrisponderanno sia benefici economici che sociali.

► Pag. 41

Andrea PaneCrapolla: a cultural landscape on the Amalfi CoastCrapolla: un paesaggio culturale in Costa d’Amalfi

Parlare di paesaggio culturale, nel caso di Crapolla, richiede una neces-saria premessa di ordine metodologico, utile a chiarire il concetto stes-so di “paesaggio”, anche alla luce della corposa letteratura apparsa sultema in anni recenti. Dopo aver ripercorso l’alterno successo della locu-zione di “paesaggio” in rapporto a quella di “ambiente” nel corso delNovecento, Paolo D’Angelo, nel suo Estetica della natura (2001), ha sot-tolineato come, ancora oggi, si determini un frequente confronto trauna visione antropocentrica ed una ecocentrica del paesaggio.La prima, simbolicamente rappresentata dal volume di RosarioAssunto Il paesaggio e l’estetica (1973), ribadisce la componente esteti-ca e culturale del paesaggio, in antitesi con le posizioni degli ambienta-listi. La seconda, al contrario – che accomuna biologi, ecologi, geografi– tende a negare la componente soggettiva insita nel paesaggio, propo-nendone una lettura “oggettiva”. Oggi, a distanza di oltre trent’anni datale dibattito, il concetto di paesaggio è ritornato decisamente in auge,divenendo oggetto della relativa Convenzione Europea del 2000, ratifi-cata dall’Italia nel 2006. La definizione di paesaggio contenuta nellaConvenzione sembra pienamente rivendicarne la componente soggetti-va ed antropica, richiamando la percezione collettiva e la presenza deifattori umani come elementi determinanti. Tale definizione è stata inseguito quasi integralmente recepita nella legislazione italiana, con lerecenti modifiche (2008) al Codice dei Beni Culturali e del Paesaggio. za partire da quest’approccio metodologico, dunque, che si è procedutoall’analisi del paesaggio del fiordo di Crapolla, aderendo all’interpreta-zione proposta da D’Angelo, che definisce il paesaggio come «identità

bilità di management per le autorità pubbliche». Le “mappe cognitive”diventavano uno strumento di lettura anche per le popolazioni chaavevano così una “percezione ambientale”. Il rischio ancora oggi risiedeperò nel fatto che le ricerche di psicologia ambientale si riferiscano alpaesaggio così come si presenta allo stato attuale, trascurando le stra-tificazioni storiche che hanno contribuito a definirlo. Dunque, la ricercadei segni lasciati sul territorio, siano essi dovuti a fenomeni naturali(terremoti, mareggiate, ecc.), siano essi il risultato dell’intervento del-l’uomo, insieme con la ricerca del significato che questi assumonosotto il profilo storico dovrà costituire la fase propedeutica per la con-servazione e valorizzazione del paesaggio.Ciascun luogo ha una sua identità estetica che si avvale anche dellaconoscenza delle sue caratteristiche specialistiche, dagli aspetti geologi-ci, geomorfologici, biologici oltre che storico-culturali che vanno inda-gati e valutati a scala territoriale. A proposito dell’area in cui insiste infiordo di Crapolla, numerose sono le descrizioni che alcuni scrittori tragli anni Cinquanta e Sessanta ci hanno lasciato. Basti citare Viaggio in

Italia di Piovene del 1958 o Conosci l’Italia di Sestini del 1963. Occorreanche ricordare quanto Roberto Pane scriveva nel 1955 nel volumeSorrento e la costa nel quale è documentata con splendide foto unasituazione che oggi purtroppo si presenta molto diversa. Infatti, a parti-re dal dopoguerra la ricostruzione ha interessato gran parte delle cittàd’Italia e ha consentito di alterare con costruzioni invasive il paesaggio,ivi compreso quello della penisola di cui ci occupiamo e soprattutto dallato della costiera sorrentina. Per quanto riguarda la costiera amalfita-na, alcuni centri, come Maiori e Minori, hanno subito l’invasione di edili-zia nuova e diversi episodi singoli hanno contribuito a peggiorare i rap-porti tra natura e ambiente. È questo il caso dell’albergo di Fuenti, defi-nito “eco-mostro” che a distanza di anni è stato demolito seppure quel-la parte di territorio, malgrado i progetti che sono stati elaborati e soloin parte realizzati, ancora oggi non è stata restaurata.Consapevole dei danni arrecati a un contesto paesaggistico di tale pre-gio, la Regione Campania commissionò, tra il 1974 e il 1977, a RobertoPane e Luigi Piccinato il Piano territoriale paesistico della penisola sor-rentina. Le scelte del piano si ponevano come obiettivo non solo la dife-sa del territorio da manomissioni, ma anche di mantenerlo, “restaurar-lo” e valorizzarlo rendendolo fruibile. Dalle scelte non è esclusa la rea-lizzazione di nuove infrastrutture o insediamenti necessari per farsopravvivere alcune aree; insediamenti che non dovevano mai interessa-re zone costiere. Si trattava di uno strumento per lo sviluppo sostenibileper un territorio di grande pregio, basato sulla tutela e valorizzazione. Acirca quarant’anni dall’elaborazione dello strumento il cui iter si è pro-tratto nel tempo, è stata ratificata in Italia la Convenzione Europea sulPaesaggio (2006) in cui è scritto: «Paesaggio designa una determinataparte di territorio, così come percepita dalle popolazioni, il cui caratterederiva dall’azione di fattori naturali e/o umani e dalle loro interrelazio-ni». Tale definizione verrà ripresa in maniera quasi identica nell’art. 131del Codice dei Beni Culturali e del Paesaggio che riporta: «Per paesaggiosi intende il territorio espressivo di identità, il cui carattere deriva dall’a-zione di fattori naturali, umani e dalle loro interrelazioni». Il rapportotra uomo e natura diventa, quindi, un elemento fondamentale per laconservazione e trasformazione del paesaggio. Il paesaggio naturale ecostruito è il risultato di una stratificazione di elementi che vanno dal-l’archeologia, anche quella sottomarina come nel caso di Crapolla, aidiversi periodi, medioevali, vicereali, fino ai giorni nostri. Proprio talestratificazione è stata in parte indagata nel fiordo di Crapolla anche alloscopo di intervenire non solo conservando e proteggendo l’esistente,ma anche individuando tutto ciò che va progettato per valorizzare ilpaesaggio e per renderlo maggiormente fruibile. In sostanza, il paesaggio va definito come un territorio sul quale la

380

LANDSCAPE AS ARCHITECTURE