Dien Bien Phu: Development and Conservation in a Vietnamese cultural landscape

Transcript of Dien Bien Phu: Development and Conservation in a Vietnamese cultural landscape

1

Dien Bien Phu: Development and Conservation in a Vietnamese Cultural Landscape

WILLIAM S. LOGAN Deakin University

Melbourne Australia

Paper Presented at the Forum UNESCO University and Heritage 10th International Seminar

“Cultural Landscapes in the 21st Century” NewcastleuponTyne, 1116 April 2005

Revised: July 2006

It has been possible to nominate places for their cultural landscape values to the World Heritage List since December 1992. The Operational Guidelines (2005) define cultural landscapes as cultural properties that ‘represent the “combined works of nature and man” designated in Article 1 of the Convention’. They are illustrative of the evolution of human society and settlement over time, under the influence of the physical constraints and/or opportunities presented by their natural environment and of successive social, economic and cultural forces, both internal and external’ (Para 47). Refining this further, the World Heritage system recognises three categories of cultural landscapes:

1. Clearly defined landscapes designed and intentionally created by man; 2. Organically evolved landscapes of two subtypes:

• Relict or fossil landscapes in which an evolutionary process has come to an end but where its distinguishing features are still visible;

• Continuing landscapes which retain an active social role in contemporary society associated with a traditional way of life and in which the evolutionary process is still in progress and where it exhibits significant material evidence of its evolution over time;

3. Associative cultural landscapes where the outstanding universal value relates to the powerful religious, artistic, or cultural associations of the natural elements rather than the evidence of material culture.

The Cultural landscape category was introduced in response to concern that the World Heritage List was becoming increasing unrepresentative of the world’s diverse cultural heritage and was in danger of losing credibility. The principal point was that the World Heritage criteria, which had been revised in 1980 and remained unchanged until 1992, seemed to privilege sites of architectural and artistic value over sites whose significance lay in other less materialistic heritage values (see Labadi 2005:413). This meant that the World Heritage system was seen to be favouring nominations from Europe to the neglect of other parts of the world, such as Africa or the AsiaPacific, where the significance of places often lay, not in monumental structures or artistic arrangements of buildings, parks and gardens, but in the way that their natural features were charged with religious or symbolic meanings and associations.

By the end of 2004, however, there were only eight cultural landscapes inscribed on the World Heritage List from the whole of the vast and diverse AsiaPacific region, although the region had managed to win a total of 158 places on the List. In other

2

words, one of the key elements of the Global Strategy to achieve a more balanced, credible and representative World Heritage List seemed to have failed.

Table 1: World Heritage Listed Cultural Landscapes in the AsiaPacific 2004

Categories of cultural landscapes recognised by the World Heritage listing system:

Inscribed Sites: World Heritage Criteria

Date of Inscription

(1) Clearly defined landscapes designed and intentionally created by man

Gusuku Sites and Related Properties of the Ryuku Kingdom, Japan

C (ii) (iii) (vi) 2000

(2) Organically evolved landscapes:

(a) Relict or fossil landscapes in which an evolutionary process has come to an end but where its distinguishing features are still visible (b) Continuing landscape which retains an active social role in contemporary society associated with a traditional way of life and in which the evolutionary process is still in progress and where it exhibits significant material evidence of its evolution over time

Rice Terraces of the Philippine Cordillera, Philippines

Vat Pou and Associated Ancient Settlements within the Champasak Cultural Landscape, Lao PDR

Orkhon Valley Cultural Landscape, Mongolia

Cultural Landscape and Archaeological Remains of the Bamiyan Valley, Afghanistan

Bam and its Cultural Landscape, Iran

C (iii) (iv) (v)

C (iii) (iv) (v)

C (ii) (iii) (iv) CL

C (i) (ii) (iii) (iv) (v)

C (ii) (iii) (iv) (v) CL

1995

2001

2004

2003

2004

(3) Associative cultural landscapes where the outstanding universal value relates to the powerful religious, artistic, or cultural associations of the natural elements rather than the evidence of material culture

Tongariro, New Zealand

UluruKata Tjuta National Park, Australia

N (ii) (iii) C (vi)

N (ii) (iii) C (v) (vi)

1990 1993

1987 1994

Peter Fowler, in his Ferrara report (2003), showed that the dearth of cultural landscapes applies not just to the AsiaPacific but to the whole list where there were at that date a total for the world of only 30 inscribed cultural landscapes out of a total of over 700 places on the List at that time. He noted, however, that there were another hundred or so World Heritage properties that would be eligible for reinscription adding their cultural landscape values.

My own reading of the failure highlights problems with the concept itself, notably the geographic scale of cultural landscapes (as compared with the more conventional ‘monuments and sites’) and the fact that they are most commonly living places, with

3

consequent complexities in seeking to apply the notions of authenticity and integrity to them in standard ways.

Cultural landscapes are typically extensive places, larger in area than the monuments and sites the World Heritage and national systems focused on before the 1990s. They incorporate complex environments in which people, flora and fauna live. They result from dynamic processes of change – processes that need to continue to change into the future if the inhabitants are to improve their standards of living. The inhabitants have the right to do this and it is unethical on our parts to give primacy to the protection of cultural landscape values by freezing landscapes into fixed representations of a traditional and exotic past. A number of World Heritagelisted cultural landscapes where this has been attempted, such as the coastal terraces of the Cinque Terre or the mountainside rice terraces of the Philippines, show that such a strategy is doomed to failure: if the inhabitants are prevented from modernising within their cultural landscape, they will simply abandon it. Either way, the cultural landscape is unlikely to survive.

By contrast, in the case of the AsiaPacific region, as with Africa and parts of Latin America, the problem is often not one of stagnation but of rapid development fuelled by exploding birth rates and an unquenchable desire by the local population to achieve higher standards of living than the poverty they have know for so long. In such a context it is difficult enough to argue for the protection of individual monuments and small historic neighbourhoods; the ambition of conserving larger, more complex cultural landscapes is even more challenging, perhaps even too challenging.

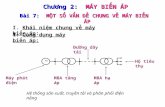

To demonstrate the dilemma I will use a Vietnamese case study – the cultural landscape of Dien Bien Phu in northwestern Vietnam. This is a cultural landscape of stunning beauty – bright green padi fields surrounded by forest and steep mountains that shelter the small settlements of local ethnic groups, the socalled montagnards or hill tribe people. Dien Bien Phu’s stunning beauty masks, however, a history of war that remains part of living memory: in this place historically significant events occurred relatively recently, being related not only to the First Indochina War 194654 but also to the collapse of European imperialism in Asia. Moreover, it is the site of a battle of a different kind that is being played out today. This battle – between the development of Dien Bien Phu town and the protection of its heritage, that is, between modernity and tradition –.is a metaphor for the wide and extremely difficult transformation of society that is currently taking place across Vietnam.

It is a cultural landscape that does not fit neatly into the 1993 World Heritage classifications. It comes closest to the Organic Cultural Landscape category, certainly fulfilling the requirements of a ‘Continuing landscape which retains an active social role in contemporary society associated with a traditional way of life and in which the evolutionary process is still in progress and where it exhibits significant material evidence of its evolution over time’. But there exists an ensemble of manmade war related sites within the landscape that are an integral part of the landscape’s recent evolution and contemporary meaning and which could be inscribed as monuments or as a heritage site in the more conventional way.

4

Photograph 1: A cultural landscape of stunning beauty and global historic significance.

Heritage significance: place, memory and identity What precisely are the heritage values of the place? Dien Bien Phu is one of the most significant cultural landscapes in Vietnam. According to local myths, the Muong Then (the ‘Land of Heaven’) was formed at the time earth and heaven were created. In 1841 under the Nguyen dynasty it was renamed Dien Bien (stable land in the border). Indigenous values are strong, but today its cultural heritage significance also lies in the way it represents the intersection of different cultural identities – the Vietnamese and the French – coming together 50 years ago in military conflict. Then, as mentioned, the ensuing half century has also added a layer that says much about modern Vietnam and in particular the role of the state in economic, social and cultural development. In this short paper I will focus on the heritage values deriving from the battle of 1954 and show how there are under threat from the subsequent processes of change in the valley, processes that are creating a new cultural landscape for the twentyfirst century.

The heritage values of Dien Bien Phu’s cultural landscape as perceived by the victorious Vietnamese and the defeated French of course vary sharply. For the Vietnamese soldiers involved in the 56 days and nights from 13 March to 7 May 1954 it was the site of the stunning Viet Minh military victory over the colonial French forces. Around 8,000 Viet Minh soldiers were killed and 15,000 wounded (Simpson 1994:169), yet Dien Bien Phu has a key place as a glorious milestone on the path to national. Moreover it has become crucial to the constructed identity of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam, a selective use of memories in support of state ideology – a task that becomes easier as memories fade and disappear along with the generation who experienced the battle of Dien Bien Phu firsthand.

For the 11,000 French soldiers garrisoned at Dien Bien Phu – 36 per cent Vietnamese, 19 per cent African, 26 per cent Foreign Legion, 19 per cent French mainland troops (Windrow 2004:647) – memories of the fear of annihilation were not assuaged by victory. Some 2,0003,000 French military personnel were killed in the fighting and 6,500 wounded.( Simpson 1994:169). About 11,000 were captured of whom perhaps more than 4,000 died in captivity. Sixtytwo French planes were destroyed and 30 canon, six tanks and 60,000 parachutes taken (Le Courrier du Vietnam 2004:9). The

5

‘Navarre Plan’, named after its architect General HenriEugène Navarre, had been to lure the Viet Minh troops into the northwest of Vietnam where they would be decimated by the superior technology and firepower of the French.

Dien Bien Phu valley had been converted to nine fortified strongholds on the rounded hills running along the eastern edge of the valley: Gabrielle in the north, AnneMarie in the northwest, Beatrice in the northeast, Isabelle in the south, and an inner ring of Huguette, Claudine, Dominique, Éliane and Françoise. But Navarre had not anticipated the Vietnamese tactics – the use of massive numbers of troops (some 49,000 according to Sagar 1991:25) and their determination to drag howitzers and mortars, antiaircraft guns and Katyusha sixtube rocket launchers onto the ridges overlooking the valley. In addition, the mobilisation of farmers by the introduction of land reform policies beneficial to them meant continuous delivery of supplies to the battlefield.

Although Viet Minh troop fatalities were high, the losses were quickly overlain by official messages of dedication and heroism. As Winphret Lulei, a Vietnam historian based in Berlin, noted recently, ‘The image of thousands of noncombatants pushing bicycles laden with food and ammunition to the front is a lasting symbol of the conflict’ (quoted in Tran Mach et al 2004:13). For the captured French troops it was a march of a totally different kind: divided into groups of 50, they were marched away to jungle prison camps in ThanhHoa Province (Simpson 1994:170). For France as a nation, the capitulation of the forces under de Castries was another symbol of acute soul searching following on from the 1940 fall to Nazi Germany, the establishment of Vichy puppet government and the collaboration with the Japanese in Indochina. It foreshadowed the loss of Algeria, the Suez debacle and the rapid decline of French imperial power in the world in the middle of the twentieth century.

Few people in the nonfrancophone West had heard much about Indochina before Dien Bien Phu (Logan 1997). But the battle prompted people to discuss Vietnam. They learned there was ‘a fullscale war going on, not just a small conflict that a few French gendarmes could quash, as France had led them to believe’ (Winphret Lulei, in Tran Mach et al 2004:13). Today, in retrospect, the battle is seen as one of the turning points not only in Vietnamese history but also in the broader history of Western intervention in Asia through colonisation and Cold War interference. The noted Vietnam scholar Stanley Karnow ranks it as ‘one of the great military engagements of history’ along with Agincourt, Waterloo and Gettysburg (quoted in Simpson 1994:xi ). The battle and the ground on which it occurred have transnational regional significance as major turning point in the French endeavour in Southeast Asia and the emergence of the modern states of Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia. Withdrawal of the French led the United States into direct engagement in what became variously known as the Second Indochina War, the Vietnam War and the American War.

If places are ever added to the World Heritage List under the theme of world colonisation and decolonisation, Dien Bien Phu must be a leading candidate for inscription. Moreover World Heritage listing would give international recognition to the place and lead to economic benefits to the region and Vietnam as a whole through cultural tourism. Such benefits might be jeopardised, however, by the modernisation and urbanisation policies that are rapidly changing the character of Dien Bien Phu and threatening its heritage values.

Evolution: conflicting uses of the cultural landscape By the time the battle was over, Dien Bien Phu was ‘little more than rubble, corpses and freezing mountain winds’. But it was at this point that the government of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam in Hanoi made the decision that some troops would

6

stay on, essentially for border security reasons. They lived ‘huddled in tattered thatched huts scattered across the valley’, mixing with the local indigenous peoples and surviving on sticky rice and wild vegetables collected deep in the forests (Hai Van 2004:8). Development in the area was slow until 1986 when the new doi moi (economic renovation) policy position breathed new life into Vietnam’s economy and local officials began to encourage residents to open private businesses. Dien Bien Phu was still a settlement of thatched huts, but the town’s traditional role in border security started to give way to broader economic development. Nevertheless what made Dien Bien Phu strategically important historically makes it a strategic area for economic development today – proximity to Lao border lands and the huge market of China.

In 2005 Dien Bien Phu city had a population of about 70,000 and is projected to grow to 100,000 by the year 2010 and 150,000 by 2020. Located 600 km from Hanoi, distance and isolation have been retarding factors and Dien Bien Phu Province is still one of the poorest regions of Vietnam. It is estimated that about 30 per cent of the provincial population live in poverty, while government subsidies represent more than 90 per cent of the provincial budget (Hai Van 2004:8, 10). But the number of flights from Hanoi to the city of Dien Bien Phu has increased to six a day in 2005, a new highway provides improved access to the north, and Dien Bien Phu is planned to become the major economic hub of Vietnam’s northwest.

The majority of tourists are Vietnamese, with French visitors a smaller although still significant group. Very few Vietnamese, even veterans, visited Dien Bien Phu before the 1990s, but more than 100,000 visitors came in 2003, contributing USD1.75M to the local economy (Hai Van 2004:9; Le Courrier du Vietnam 2004:9). A massive leap in numbers – ‘touristes de souvenirs’ – occurred in 2004, the fiftieth anniversary of the battle (Le Courrier du Vietnam 2004:9). While Hoang Van Be, Deputy Chairman of the Dien Bien People’s Committee, might argue that ‘We don’t want people to think Dien Bien is still the warravaged site of a battle that survives on charity’ (quoted in Hai Van 2004:9), economic growth is being spearheaded through the development of leisure, ecological and cultural (including heritage) tourism. There is some overlap in interests between the Vietnamese and French national groups but also some divergences. Both groups take in the sites of fierce fighting in Dien Bien Phu, such as the hills A1 (Éliane), C1, D1 and E1, the French command centre focused on the De Castries tunnel, the nearby areas of Him Lam (Béatrice), Doc Lap (Gabrielle) and Hong Cum (Isabelle), the bridge of Muong Thanh, and the Dien Bien Phu Museum. The Vietnamese visit General Giap’s campaign command headquarters at Muong Phang 40 kilometres away and the war graves and commemorative complexes in and around the town. The French, on the other hand, invariably make a special visit to the French memorial.

Management: balancing urbanisation and heritage protection For the Vietnamese, the battle sites are not just considered a valuable resource for the province but also for the nation as a whole and, as such, have been invested with a huge amount of capital from the state budget to upgrade the complex with the aim of attracting tourists. Because the rice fields are highly valued and reputed to produce the best rice in Vietnam, they cannot be converted to other uses and the town is developing as a series of fingers running into and around the hills that were the main sites of fighting during 1954. The principal axis, Boulevard 7 May, is a chief offender in this regard. Vietnamese political, administrative and legal structures exacerbate the problem. Dien Bien Phu was raised in 1992 from the status of Commune to Town and in 2003 to City and has its own city administration responsible, but the city planners are required to conform to the planning goals for urban growth in the 5,600 ha of provincial territory that it administers that are imposed from Hanoi.

7

Photograph 2: Dien Bien Phu town ends abruptly at the edge of the padicovered plain.

The urban population consists predominantly of immigrant Kinh Viet, especially coming from Thai Binh Province, and local ethnic minority people. Neither group projects its views strongly on how it wants Dien Bien Phu to develop. Public participation is limited in Vietnamese context. Never in history has there been a sustained practice of bottom up decisionmaking involving the common people, although the current regime argues that its articulated hierarchy of political structures ensure the representation of popular views (Logan 2002:172; McCarty 2001; HueTam Ho Tai 2001:9). A challenge of the future in Vietnam will be to broaden the understanding of citizenship to include taking greater control over one’s own life and local environment. There are signs of change and conflicts over heritage protection, as against environmentally insensitive development projects, have been important in forging an early path towards such a wider conception of citizenship (Logan 2002).

In assessing the likely success of management strategies, Vietnamese popular attitudes towards heritage and commemoration need to be taken into account. They differ significantly from their Western counterparts. Vietnamese people respect and commemorate heroes, ancestors and important historical incidents, including victories over enemies, and there is a strong feeling of obligation towards the fatherland. But the object of commemoration is often not the historical facts of people and events from the past but popular belief and mythical constructions of spiritual importance to current communities. Battle fields fall outside the traditional range of Vietnamese ‘heritage’ items and the memorialisation of Dien Bien Phu is not of great importance or interest to the general population. In the tussle between further economic and urban development and the protection of battle sites, the popular vote is likely to run strongly in favour of development. However Western approaches to heritage are well understood and supported by scholars and they are now being more widely diffused among the general population through the media, particularly in connection with the highly publicised national anniversary celebrations, such as the 50 th anniversary of Dien Bien Phu in 2004. That so many Vietnamese domestic tourists visited the battle sites reflects the

8

growing appreciation of places as heritage objects, at least among those strata of society with the discretionary spending power and leisure time to travel.

In other words, it may be expected that over time a proheritage conservation stance directed at a broader range of heritage items will gradually become normal in Dien Bien Phu and elsewhere. In the meantime the main concern of the general Vietnamese population is to modernise the country quickly. They prefer to forget the conflict and pain of the past and focus more on current problems. It is fortunate – for the conservationists – that Western attitudes to heritage place protection have become accepted in official planning policy frameworks and, with decision making still being topdown, the general public’s apathy towards heritage protection has reduced practical implications.

Nevertheless this divergence of attitudes produces a tension that is impossible to resolve to everyone’s satisfaction, although in cultural tourism there is at least a strong argument about the economic return that comes to the community through the maintenance of heritage sites. But this merely shifts the tension away from strategic planning arena and focusing it onto the management practices at the sites themselves. As HueTam Ho Tai (2001:1314) commented,

Commemorative sites such as these play a double function: as building blocks in the state’s narrative of glorious war and triumphant revolution, and as fodder for entertainment. In an uneasy combination of the epic and the ironic, they are expected to sustain memory and generate money all at once.

In general terms, the Dien Bien Phu People’s Committee is aware that it must offer more services to attract tourists and that greater attention needs to be paid to satisfying people who want to learn about Vietnam’s history through the provision of information desks at historical sites and brochures in English and Vietnamese. It is even encouraging ethnic groups in 15 villages around Dien Bien Phu to allow tourists to stay in their homes so that they can explore the culture and lifestyles (Hai Van 2004:9. Vietnamese governments were once afraid of contact between tourists and local people but are now more relaxed and able to exploit economic possibilities.

The Ministry of Culture and Information, the central authority responsible for heritage sites, sees the expansion of Dien Bien Phu town as the most direct and greatest danger to the integrity of the complex. It commissioned Professor Hoang Dao Kinh to consider and advise on the situation. His 2000 report to MOCI confirmed the urgent need for an urban conservation and enhancement plan for the whole complex, and for other socioeconomic and development plans to be adjusted to fit the conservation objectives (MOCI 2000:unpaginated). Professor Kinh advocated cultural tourism initiatives as a possible means of regenerating the cultural landscape, provided that this ‘great exploitative potential of the historic vestiges in Dien Bien Phu [is] enhanced and improved by suitable urban planning’.

By 2005, however, much destruction of warrelated heritage values of the cultural landscape has occurred. Roads now cut into the hills, and most trenches in the Nuong Thanh field are gone. Many historical objects have been incorrectly reconstructed, new monuments erected in the site, and rapid expansion of the city has changed the shape of the battlefield. In short, the cultural landscape is being radically reconfigured. Nevertheless, some important conservation victories have also been won. The government authorities in Dien Bien Phu, if not the general public, are now aware of the significance of the battle sites and recognise that their implementation plans need to take some degree of heritage protection into account. The most dramatic example of this has been the decision to halt the construction of a major road that was originally

9

designed to cut through a key battlefield precinct near the de Castries vault and Muong Thanh Bridge.

Photograph 3: Conservation concerns halted the continuation of this major road into the 1954 French army command precinct.

Wider implications: a battle site, metaphoric and actual Not only is Dien Bien Phu is a key place in terms of the formation of independent Vietnam, but it is also the site of a broader battle continuing into the twentyfirst century – a battle between tradition and national identity formation on the one hand, and modernity and urbanisation on the other, that is both an actuality for the local community in the town and district of Dien Bien Phu and a metaphor for the difficult transformation of postdoi moi Vietnamese society generally. But it is something of a confused metaphor, with the notions of celebrating history converging with calls for faster modernisation, and efforts to protect Vietnamese cultural identity sitting uncomfortably alongside the often priority given to redevelopment of historic areas.

Thus, on the one hand, General Vo Nguyen Giap, teachersoldier who led the Vietnamese to victory in 1954, can cry in his address in Hanoi at the celebrations marking the 50 th anniversary of the 5 May 1954 victory

Let today’s generations bring into play Dien Bien Phu’s spirit to act resolutely and creatively to accelerate the modernisation and industrialisation of Vietnam, to build and protect the motherland, to put a strong end to the current backward situation, so as to foster our country’s development (quoted in Viet Hung 2004:4).

On the other hand, Dien Bien Phu is also portrayed as a metaphor for Vietnamese identity under challenge – or at least the identity promoted by the political regime currently in power. As HueTam Ho Tai (2001:1) notes, commemorative fever is running high in ‘late Socialist Vietnam’ and ‘threatening to blanket the Vietnamese landscape with monuments to the worship of the past’. This fever, he adds (2001:3), is ‘not just a salvage operation designed to preserve traces of a fastvanishing past

10

before they obliterated by the forces of relentless capitaliststyle modernization’; the real answer lies in the need felt by the Vietnamese leadership to promote ‘a version of the past that inscribes it as the legitimate inheritor of the Vietnamese patriotic tradition and the dominant force in the recent history of the country’. The national and provincial authorities will continue to try to contain the metaphoric battle between heritage, socialist development and creeping capitalism.

The local effort to protect the heritage values of Dien Bien Phu cultural landscape while concurrently encouraging urban development represents a microcosmic and actual version of the larger ideological struggle. To balance the two objectives is clearly difficult and the case study suggests that the heritage may lose out. The next decade is likely to determine whether this actual struggle portends the resolution of the wider metaphoric battle, the eclipse of current ideological representations of the Vietnamese state and its people, and the emergence of a society that is less trammelled by official conceptions of heritage but impoverished in an increasing detachment from its historical roots and memories.

Conclusion Let us return to the question asked by Fowler: why have not more cultural landscapes been nominated in Asia? The concept seems to work well in Europe and indeed has been very popular there. As Tables 2 and 3 indicate, the proportion of European cultural landscapes on the World Heritage List is in fact higher than the proportion of European cultural heritage sites generally on the List. Only in the associative cultural landscape category does the balance clearly move away from Europe but the total number of inscriptions in this category remains very small.

Table 2: Euro centrism in Cultural Inscriptions

Cultural Inscriptions Cultural plus ‘Mixed’ Inscriptions

Total Inscrip tions World Europe World Europe

Period

No. No. No. % No. No. % 1978 1980

84 64 28 43.8 66 29 43.9

1981 1985

131 91 40 44.0 97 41 42.3

1986 1990

111 89 45 50.6 98 48 49.0

1991 1995

133 105 59 56.2 105 59 56.2

1996 2000

216 180 116 64.4 186 119 64.0

2001 2005

123 99 51 51.5 100* 52* 52.0

Total 798 628 339 54.0 652 348 53.4

* Includes St Kilda, UK, which was inscribed in 1986 as a Natural site but reinscribed as a Mixed site in 2005.

11

Table 3. World Heritage Listed Cultural Landscape, 2005

Europe Category Total no. inscri ption s

No. %

(1) Clearly defined landscapes designed and intentionally created by man

6 6 100. 0

(2) Organically evolved landscapes:

(a) Relict or fossil landscapes in which an evolutionary process has come to an end but where its distinguishing features are still visible

(b) Continuing landscape which retains an active social role in contemporary society associated with a traditional way of life and in which the evolutionary process is still in progress and where it exhibits significant material evidence of its evolution over time

7

32

5

20

71.4

62.5

(3) Associative cultural landscapes where the outstanding universal value relates to the powerful religious, artistic, or cultural associations of the natural elements rather than the evidence of material culture

6 1 16.7

Total Cultural Landscapes 51 32 62.7

Former World Heritage Centre director, Bernd Von Droste, has observed that cultural landscapes depend on agriculture continuing in the traditional way (Von Droste, ‘Heritage Education: Capacity Building in Heritage Management’, International Symposium, Brandenburg University of Technology, Cottbus, Germany, 1418 June 2006). Perhaps the protection of traditional forms of production and hence cultural landscapes is more achievable in Developed Countries where population numbers are stable, standards of living are high, and people are able to hold on to landscape aesthetics derived from the past. In Developing Countries exploding population numbers and the ambition to raise standards of living, shared by people and governments, provides a less favourable context for heritage protection.

In Vietnam, where a dominant slogan of the current political regime is ‘A wealthy people, a strong nation, an advanced , democratic and equitable society’, high on the list of most urgent tasks are ‘hunger eradication’ and enhancing the standard of living for ethnic people, especially those in remote areas. The Central Committee of the Communist Party in July 2003 defined this more closely as ‘settling pressing issues including the shortage of food, supply of safe water, removal of makeshift houses, [overcoming the] lack of means of production and basic living implements; [and] building infrastructure in the border and remote areas and areas under difficulties’ (Communist Party of Vietnam 2003:51). Dien Bien Phu is clearly a priority area, due particularly to its strategic location on the Lao border and close to China.

12

It is unlikely that the local authorities will be attracted to arguments about protecting traditional lifestyles and forms of production, especially over the broad swathes of land implied by the term cultural landscape. Indeed, the authorities do not feel the need to widen the range of difficulties already confronting them in order to encompass cultural landscape conservation concerns. This would lead to greater stakeholder conflict and make vastly more difficult their effort to satisfy the centrally imposed economic and social goals. The only way forward for advocates of cultural landscape protection under such circumstances is to make clear that this does not mean freezing people and places in the past and that the conservation of the key values of cultural landscapes can, with careful management, be consistent with modernisation and improved standards of living.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I am grateful to Nguyen Thanh Binh and Fiona Erskine, my research assistants in the Cultural heritage Centre for Asia and the Pacific at Deakin University, and to Mr Vu Quang Cac, Director, Planning and Investment Department, and Mr Nuong Phuong Cac, Director, Conservation Project Management Department, both in the Dien Bien Phu provincial administration, for their generous assistance during site visits in January 2005.

REFERENCES

Communist Party of Vietnam, Central Committee (2003). ‘Resolution on Ethnic Issues’, in Resolutions of the 7 th Plenum (9 th Tenure), The Gioi Publishers, Hanoi.

Fowler, P. (2003). World Heritage Cultural Landscapes 19922002. UNESCOWorld Heritage Centre, Paris.

Hai Van (2004). ‘War on poverty rages at historic battleground’, Outlook, Vol. 1, no. 4, April, pp. 810.

HueTam Ho Tai (ed.) (2001). The Country of Memory: Remaking the Past in Late Socialist Vietnam. University of California Press, Berkeley & Los Angeles.

Labadi, S. (2005). Questioning the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention, Unpublished PhD Dissertation, University of London.

Le Courrier du Vietnam (9 May 2004), p. 9 news items under heading ‘Le cinquantenaire de la victoire célébré sur l’ancien champ de bataille’ [Fiftieth anniversary of the victor celebrated on the former battlefield].

Logan, W. S. (1997). ‘The Angel of Dien Bien Phu: Making the AustraliaVietnam Relationship 19551995'. In M. McGillivray and G. Smith (eds), Australia and Asia, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1997; pp. 178202.

Logan, W. S. (2002). ‘Golden Hanoi, Heritage and the Emergence of Civil Society in Vietnam’. In W. S. Logan (ed.), The Disappearing Asian City: Protecting Asia’s Urban Heritage in a Globalizing World’, OUP, Hong Kong; pp. 16684.

13

McCarty, A. (2001). Governance Institutions and Incentive Structures in Vietnam, Building Institutional Capacity in Asia (BICA) Conference, Jakarta, 12 March 2001.

Ministry of Culture and Information (MOCI), Centre of Monument Design and Restoration (2000). Conservation, Repair, Embellishment and Improving the Value of the Heritage Complex of the Dien Bien Phu – Lai Chau Victory: Investment Project. Preliminary Research. Report Summary, unpublished report, Hanoi, September (in English).

Sagar, D. J. (1991). Major Political Events in IndoChina 19451990, Facts on File Inc, New York.

Simpson, H. R. (1994). Dien Bien Phu: The Epic Battle America Forgot, Brassey’s Inc., Washington DC.

Tran Mach, Duc Hap, Duy Hoang and Van Long (2004). ‘Memories of siege strong 50 years on’, Outlook, Vol. 1, no. 4, April, pp. 123.

UNESCO, World Heritage Centre (2005). Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention, UNESCO, Paris.

Viet Hung (2004). ‘The spirit of Dien Bien Phu lives on’, Vietnam Investment Review, 1016 May, p. 4.

Windrow, M. (2004). The Last Valley: Dien Bien Phu and the French Defeat in Vietnam, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London.

![[Dien Bien Phu, Military Casualties] Diên Bien Phu : les pertes militaires](https://static.fdokumen.com/doc/165x107/6313b9b385333559270c5e30/dien-bien-phu-military-casualties-dien-bien-phu-les-pertes-militaires.jpg)