Superficial Necrolytic Dermatitis (Necrolytic Migratory Erythema) in Dogs

Necrolytic migratory erythema: a classical cutaneous presentation of the glucagonoma syndrome

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

1 -

download

0

Transcript of Necrolytic migratory erythema: a classical cutaneous presentation of the glucagonoma syndrome

ELSEVIER Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology Venereology

9 (1997) 68-73

Case report

ADV

Necrolytic migratory erythema: a classical cutaneous presentation of the glucagonoma syndrome

S.A. Vaughan Jones a'*, M.G.S. Dunnill a, J. Wilding d, K. Liddell b, A.N. Gorsuch c, S.R. Bloom d, M.M. Black a

aSt. John's hlstitute of Dermatology, London, UK bBexhill Hospital, Sussex, UK

CConquest Hospital, Sussex, UK aHammersm#h Hospital, London, UK

Abstract

We report a case of necrolytic migratory erythema secondary to an underlying pancreatic glucagonoma causing the glucagonoma syndrome. We discuss the differential diagnosis of necrolytic migratory erythema and the importance of recognising this rare endocrine tumour with its marked cutaneous features. Patients with glucagonoma syndrome can present late in a debilitated state and often require much nutritional support. Treatment with a new long-acting somatostatin analogue, Lanreotide (Somatuline S.R.) 30 mg once weekly, has in our case so far produced encouraging results. We would like to emphasise the importance of the insidious onset of this syndrome and the high incidence of metastatic disease at presenta- tion. © 1997 Elsevier Science B.V.

Keywords: Glucagonoma syndrome; Necrolytic migratory erythema; Lanreotide

1. In t roduct ion

Pancreatic glucagonoma is a tumour of pancreatic islet alpha ceils which produces a combination of classical features both cutaneously and systemically, referred to as the glucagonoma syndrome. The cuta- neous features, referred to as necrolytic migratory erythema, with predilection for the flexures and peri- neum, are highly pathognomonic of this condition. The systemic features consist of painful glossitis, vari- able glucose tolerance, anaemia, thromboembolic ten- dency, weight loss with cachexia and depression.

* Corresponding aud~or.

There is also an increased tendency towards throm- boembolism. Our case, a 52 year old female, pre- sented to the general physicians with all these features and subsequent investigation revealed a pan- creatic glucagonoma with liver metastases.

2. Case report

The patient, a 52 year old female, first developed an erythematous patch of skin following a deep vein thrombosis on the right lower leg in 1994. Later her rash became more generalised to involve her scalp, face, trunk and limbs. Her other symptoms included weight loss, anorexia, a painful glossitis, diarrhoea with pale stools ,and paraesthesiae of the fingers.

0926-9959/97/$17.00 © 1997 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved PII S0926-9959(97)00602-8

S.A. Vaughan Jones et al. /J. Eul: Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 9 (1997) 68-73 69

folate. Plasma glucagon was elevated at 1129 pmol/l (normal <50), chromogranin elevated at 421 pmol/1 (normal <200) and pancreatic polypeptide elevated at 472 pmol/1 (normal <300). Serum VIP, gastrin, soma- tostatin and neurotensin were all within the normal ranges. An ultrasound and computerised tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen revealed liver metastases and a prim,u3, lesion in the pancreas. An ultrasound- guided liver biopsy showed histological evidence of a glucagonoma with characteristic islet cell architec- ture. Electron microscopy confirmed this with promi- nent Golgi apparatus and secretory granules within pancreatic islet neuroendocrine cells. An l lllndium - labelled Pentreotide scan showed multiple lesions throughout the liver consistent with multiple liver sec- ondaries from a neuroendocrine tumour and also iden- tified the 2 cm diameter pancreatic mass seen on the

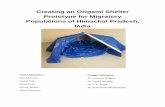

Fig. 1. Beefy red tongue with angular cheilitis before treatment.

General examination revealed clinical pallor and cachexia, with a marked beefy red tongue and angular cheilitis (Fig. 1). She had a widespread scaly eroded erythematous eruption in a seborrhoeic distribution, particularly involving the hands, elbows, right lower leg, perianal area and groins with secondary intertrigo (Figs. 2 and 3). Individual lesions had a definite crus- ted serpiginous edge with scattered smaller peripheral papules. She also had marked thinning of her scalp hair.

A preliminary skin biopsy had been unhelpful. Two further biopsies of the right leg were performed, the second of which revealed histology typical of necro- lyric migratory erythema with overlying parakerato- sis, intraepidermal cell vacuolation in the region of the granular cell layer and an upper demaal lymphohistio- cytic infiltrate (Fig. 4). Other investigations showed a normochromic normocytic anaemia with a haemoglo- bin of 9.2 g/dl but a normal ferritin, vitamin B12 and

Fig. 2. Patient's face showing marked cachexia and superficial necrolysis of perioral skin.

70 S.A. Vaughan Jones et al. / J. Eur. Acad. DermatoL Venereol. 9 (1997) 68-73

duced a dramatic resolution of her rash within a few days and enabled her other topical medication to be stopped completely. This response was reflected by her plasma glucagon levels which fell dramatically to between 80 and 120 pmol/l (normal <50) and have remained at that level in the 9 months since starting treatment. Unfortunately, she developed Clostridium difficile infection requiring enteral feed- ing via a nasogastric tube, and also needed a blood transfusion for persistent anaemia. She also went on to develop recurrent deep venous thromboses despite an INR only just below the therapeutic range.

During her admission she also became acutely con- fused with paranoid ideas and depressive symptoms and was therefore commenced on Lofepramine 70 mg nocte. Despite these complications her general condi-

Fig. 3. Characteristic involvement of the perianal area before treat- ment with serpiginous edge of crusted erythematous skin.

CT scan (Fig. 5). Her clinical signs and investigations were fully

compatible with a metastatic glucagonoma. Initial treatment consisted of oral supplementation with zinc, multivitamins, a high protein diet and Ampho- tericin mouth lozenges for oral muco-cutaneous can- didiasis. Her skin partially improved following the application of topical Fucibet and Canesten to the groins and perineum, but more importantly with improved nutrition. In view of the high risk of throm- boembolism in this condition long term warfarin was continued.

She was entered into a clinical trial of a new long- acting somatostatin analogue, Lanreotide (IPSEN). This is an intramuscular injection with the advantage over Octreotide [1] in that the frequency of adminis- tration is every 7-14 days instead of three times daily. This treatment, initially given every 2 weeks, pro-

- e

. ~ P

Fig. 4. Skin biopsy showing intra-epidermal cell vacuolation with overlying parakeratosis and an upper dermal perivascular lympho- cytic infiltrate pathognomonic of necrolytic migratory erythema ( x I00).

S.A. Vaughan Jones et al. / J. Eul: Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 9 (1997) 68-73 71

Fig. 5. H~Indium-labelled Pentreotide scan of upper abdomen showing several focal areas of radioactivity in the liver and a single ,area in the pancreas.

tion continued to improve and she was eventually discharged 10 weeks later. She is currently receiving Lanreotide 30 mg weekly. The frequency of injections was increased because her rash and glossitis began to recur several days before the next injection was due when fortnightly treatment was first initiated.

3. Discuss ion

The glucagonoma syndrome describes the constel- lation of signs which accompany a tumour of pancrea- tic islet alpha cells. Apart from the characteristic rash of necrolytic migratory erythema which shows marked predilection for the flexures and perianal area, patients also typically experience a painful glos- sitis, variable glucose tolerance, anaemia, throm- boembolic tendency, weight loss and depression. These features were all present in our case and should alert one to this unusual diagnosis. Glucagonomas can, however, occur with or without the syndrome [2]. The different subtypes of glucagonoma have been classified previously but for practical purposes two divisions are important: (1) sporadic glucagono- mas and (2) glucagonomas associated with multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN). The incidence of the glu- cagonoma syndrome is estimated to be between 1 in

20 million and 1 in 30 million per year with a female preponderance [3]. Affected individuals are usually aged between 45 and 65 years and present with a protracted history of a dermatitis with accompanying weakness, weight loss and invariably a painful glossi- tis [4]. In 1974 Mallinson reported nine cases detail- ing the full syndrome [3]. The cardinal feature is the necrolytic migratory erythematous eruption which occurs in over 90% of cases [2], starting in the groins and then spreading to the limbs, buttocks and peri- neum. Individual lesions are erythematous and scaly, then become vesicopustular and eventually bul- lous. Erosion and crusting then occur with healing normally 10-15 days after the onset of the rash [5]. The rash typically relapses and remits, and is nearly always associated with angular cheilitis and atrophic glossitis. A similar necrolytic rash is also seen in asso- ciation with chronic pancreatitis [6], carcinoma of the pancreas [7], zinc deficiency [8] and kwashiorkor [9]. Other cutaneous features of the glucagonoma syn- drome include hair thinning, onycholysis, vulvovagi- nitis and urethritis. Other systemic features which may be present include glucose intolerance, low total plasma amino acids, weight loss, anaemia, clin- ical depression and abdominal pain [9], all of which were clearly seen in our patient. There is also a high incidence of thromboembolism (with 50% mortality from pulmonary embolism) which can be prevented by treatment with long term anticoagulation. The mechanism for this coagulopathy has been suggested to be an increase in factor X produced by pancreatic alpha cells [ 10].

Elevated fasting plasma glucagon levels are also characteristic of, though not specific for, this syn- drome. Glucagon is a single chain pancreatic polypep- tide of 29 amino acids with a molecular weight of 3485 [ 11 ] produced in the alpha cells of the pancreatic islets. It is a hormone that elevates blood glucose by promoting glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis in the liver [ 12]. High plasma glucagon levels are associated with low plasma amino acid levels, and correction of this has led to a significant improvement in the rash in some cases despite no reduction in serum glucagon levels [13], although in other cases the rash is unchanged. Elevation of serum glucagon levels occurs in a number of other situations, notably trauma, bums, diabetic ketoacidosis [14], starvation [15] and cirrhosis of the liver [16], none of which have an

72 S.A. Vaughan Jones et aL / J . Eur. Acad. DermatoL Venereol. 9 (1997) 68-73

associated rash. In 80% of cases the primary pancreatic tumour is

malignant with metastases to the liver, lymph nodes and, rarely, to the bones. These metastases are usually slow growing and may respond to surgical debulking or selective hepatic arterial embolisation. In our patient an HIIndium-labelled Pentreotide scan was performed to identify the site of any further metas- tases. Many glucagonomas present relatively late, as in our case, and there is often good correlation between total tumour bulk, serum glucagon levels and severity of the rash. Unfortunately, the median length of survival is only between 2 and 3 years from the time of diagnosis [17].

The histological findings on skin biopsy are highly specific for glucagonoma but several biopsies may be required at the edge of new lesions before the typical appearances are seen. Sweet, in 1974, used the term superficial epidermal necrosis to describe the lesions [18]. Kheir further described a variety of findings in this condition which included epidermal necrosis, subcorneal pustules, confluent pa/akeratosis, epider- mal hyperplasia and marked papillary dermal angio- plasia [19]. With the use of electron microscopy, a variable number of specific spherical secretory gran- ules can be found in both normal and neoplastic pan- creatic islet cells. The secretory granules may be entirely atypical, particularly in malignant tumours.

Treatment of this condition is largely unrewarding as the majority present late with metastases. Surgery offers a complete cure for only 5% of glucagonomas because of the high incidence of secondary spread [5]. As the metastases are slow-growing, non-curative sur- gical debulking may improve symptoms but does not alter long term survival. Excision of the primary tumour with liver transplantation for metastatic liver disease has been attempted in four glucagonoma cases, three of whom are still alive and disease-free at 3 years [20]. Selective hepatic embolisation pro- vides an alternative treatment, and can be performed using 5-fluorouracil which has an additional che- motherapeutic effect. Streptozocin and 5-fluorouracil are reasonably successful as a palliative therapy with a response rate between 60 and 70% [21].

The mainstay of therapy is the somatostatin analo- gue, Octreotide. This is normally given subcuta- neously on a daily basis, but Lanreotide, a newer analogue may be given once per week or fortnight,

as a deep intramuscular injection, depending on the clinical response. Chronic therapy with Octreotide reduces the severity of the rash, but a larger dose may be required later in treatment as resistance to Octreotide occurs. Once this has occurred, disease activity escalates and death may rapidly ensue. Despite the extensive nature of our patient's disease, these tumours tend to grow slowly and long term sur- vival is still possible once symptomatic control is achieved.

Our patient remains well, having been on weekly Lanreotide injections for 9 months, and will continue on this therapy for the time being. If in the future she fails to respond to the somatostatin analogue then other therapeutic options such as arterial hepatic embolisation, chemotherapy with streptozocin and 5-fluorouracil and, as a last resort, liver transplanta- tion will be considered.

References

[1] Jockenhovel F, Lederbogen S, Olbricht T et al. The long- acting somatostatin analogue octreotide alleviates symp- toms by reducing post-translational conversion of preproglu- cagon to glucagon in a patient with malignant glucagonoma but does not prevent tumour growth. Clin Invest 1994;72(2):127-133.

[2] Ruttman E, Kloppel G, Bommer Get al. Pancreatic glucago- noma with and without syndrome: immunocytochemical study of 5 tumour cases and review of the literature. Vireh- ows Arch (Abteilung) 1980;388:51-67.

[3] Mallinson CN, Bloom SR, Warin AP et al. A glucagonoma syndrome. Lancet 1974;2:1-3.

[4l Lewis AE. The glucagonoma syndrome. Int J Dermatol 1979;18:17-22.

[5] Wynick D, Hammond PJ, Bloom SR. The glucagonoma syn- drome. Clin Dermatol 1993;11:93-97.

[6] Polak JM, Bloom SR, Adrian TE et al. A glucagonoma syn- drome. Lancet 1976;1:328-330.

[7] Wilkinson DS. Necrolytic migratory erythema with carci- noma of the pancreas. Trans St. John's Hosp Dermatol Soc 1973;59:244.

[8] Thivolet J. Necrolytic migratory erythema without glucago- noma (letter). Arch Dermatol 1981;117:4.

[9] Chong LY, Cham-Fal L, Woo CH et al. Necrolytic migratory erythema in glucagonoma syndrome. J Dermatol 1992;19:369-374.

[10] Bordi C, Yu JY, Girolami A et al. Immunohistochemical localisation of factor X-like antigen in pancreatic islets and their tumours. Virehow's Arch (Abteilung) 1990;416:397- 402.

S.A. Vaughan Jones et al. / J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 9 (1997) 68-73 73

[11] Bromer W, Staub A, Diller ER et al. The amino acid sequence of glucagon. Amino acid composition and terminal amino acid analysis. J Am Chem Soc 1957;79:2794.

[12] Kahan RS, Perez-Figaredo RA, Neimanis A. Necrolytic migratory erythema, destructive dermatosis of the glucago- noma syndrome. Arch Dermatol 1977;113:792-797.

[13] Norton JA, Kahn RC, Schiebinger R et al. Amino acid defi- ciency and the skin rash associated with glucagonoma. Ann Int Med 1979;91:213-215.

[14] Mallinson C, Bloom SR. The hyperglycaemic, cutaneous syn- drome: pancreatic glucagonoma. In: Friesen SR, Bolinger RD, eds. Surgical Endocrinology: Clinical Syndromes. Phila- delphia: Lippincott 1978:171-201.

[15] Aguilar-Parada E, Eisenstraut AM, Unger RE. Effects of star- vation on plasma pancreatic glucagon in normal man. Dia- betes 1969;18:717.

[16] Marco J, Diego J, Villaniceva ML et al. Elevated plasma glucagon levels in cirrhosis of the liver. N Engl J Med 1973;289:1107.

[17] Wynick D, Anderson JV, Williams SJ et al. Resistance of metastatic pancreatic endocrine tumours after long term treat- ment with the somatostatin analogue octreotide (SMS 201- 995). Clin Endocrinol Oxford 1988;30:385-388.

[18] Sweet RD. A dermatosis specifically associated with a tumour of pancreatic cells. Br J Dermatol 1974;90:301- 308.

[19] Kheir SM, Omura EF, Grizzle WE et al. Histologic variation in the skin lesions of the glucagonoma syndrome. Am J Surg Pathol 1986;10:445-453.

[20] Alsina AE, Bartus S, Hull D et al. Liver transplantation for metastatic neuroendocrine tumour. J Clin Gastroenterol 1990;12:533-537.

[21] Moertel CG, Lefkopoulo M, Lipsitz S e t al. Streptozocin- doxorubicin, streptozocin-fluorouracil, or chlorozotocin in the treatment of advanced islet-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 1992;316:519-523.