Morphological productivity measurement: Exploring qualitative versus quantitative approaches

Transcript of Morphological productivity measurement: Exploring qualitative versus quantitative approaches

This article was downloaded by: [Jesús Fernández-Domínguez]On: 30 June 2013, At: 08:55Publisher: RoutledgeInforma Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registeredoffice: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

English StudiesPublication details, including instructions for authors andsubscription information:http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/nest20

Morphological ProductivityMeasurement: Exploring Qualitativeversus Quantitative ApproachesJesús Fernández-DomínguezPublished online: 18 Jun 2013.

To cite this article: Jesús Fernández-Domínguez (2013): Morphological Productivity Measurement:Exploring Qualitative versus Quantitative Approaches, English Studies, 94:4, 422-447

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0013838X.2013.780823

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Anysubstantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing,systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden.

The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representationthat the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of anyinstructions, formulae, and drug doses should be independently verified with primarysources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings,demand, or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly orindirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

Morphological ProductivityMeasurement: Exploring Qualitativeversus Quantitative ApproachesJesús Fernández-Domínguez

Morphological productivity was originally described as the property of word-formationprocesses whereby new words are created to satisfy a naming need, a definition laterenhanced with Corbin’s classical distinction between availability and profitability. Despitethe importance of these two concepts, they have been traditionally overlooked in the designand discussion of productivity computations. Moreover, no thorough exploration has beenmade of the implications they have in existing models of productivity measurement. Thispaper examines the treatment given to this notional pair in the mainstream productivitymethods by, first, examining their theoretical background and, second, discussing theirpractical implications in their application to a BNC-derived corpus. Subsequently, anumber of suggestions are provided, and an alternative unifying method is proposedwhich is able to provide insights into both availability and profitability in thecomputations of morphological productivity of word-formation processes.

1. Introduction

Morphological productivity, according to the seminal definition by Henk Schultink,is the property of word-formation processes whereby new words are unintentionallycreated to satisfy a naming need.1 Traditional work on productivity had beengenerally grounded on intuitions,2 while in the seventies a number of proposals toempirically measure productivity emerged. The earliest reported attempt to computeproductivity was designed by Helmut Berschin who, under the label Besetzungsgrad(“degree of exhaustion”), proposed to compare the number of possible derivatives ofan individual process with the derivatives which it has actually created.3

Jesús Fernández-Domínguez is affiliated with the University of Valencia, Spain. Email: [email protected], 113.2E.g. Hockett, 15–16; Marchand, 139–40, 263.3In his view, because some processes have more bases to which they attach than others, it seems more accurate tomeasure each process individually by considering its own scope of application (cf. Berschin, 44–5).

English Studies, 2013Vol. 94, No. 4, 422–447, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0013838X.2013.780823

© 2013 Taylor & Francis

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Jesú

s Fe

rnán

dez-

Dom

íngu

ez]

at 0

8:55

30

June

201

3

Since Berschin, two well-differentiated trends can be distinguished. There are, on theone hand, scholars who understand productivity measurement as a fluctuation of thenumber of attested words and, on the other, scholars for whom a process is either pro-ductive or unproductive. This two-fold demarcation reflects Danielle Corbin’s classicaldistinction between availability and profitability,4 which has become a milestone inensuing works due its sheer weight for the theory of morphological productivity. Avail-ability relates to whether a given word-formation process is able to develop new deriva-tives productively, and is hence a qualitative notion, an all-or-nothing matter, that is, aprocess is either available or unavailable. Profitability, by contrast, is a question of gra-dation, a quantitative concept, so one available process may create more derivativesthan another one, that is, some processes are more profitable than others. The impor-tance of these two terms is vital for a proper understanding of productivity and,because both are hyponyms of morphological productivity, it has been emphasisedthat they should be aseptically kept apart to avoid terminological misunderstandings.5

Notwithstanding the unquestionable relevance of availability and profitability, thefact is that the seed of this notional pair was ascertained only in 1986 with DieterKastovsky’s distinction between “scope of a rule” (i.e. availability) and “its actual util-isation in performance” (i.e. profitability), followed by Corbin’s actual labelling of bothnotions as such. Precisely because availability and profitability are relatively youngterms, some authors had previously spoken of productivity sometimes meaning avail-ability, and sometimes meaning profitability.6 To add to the terminological confusion,the great majority of current studies on productivity still refer to productivity as awhole, while their proposals sometimes deal with availability and others withprofitability.7

The above opposition is also ignored in the design and discussion of productivitycomputations. One could intuitively say that, traditionally, a marked tendency existstowards profitability-oriented productivity models, although no thorough examin-ation has been carried out in the literature regarding the stance of existing modelstowards availability or profitability. Surprisingly enough, scholars have rarely explicitlydeclared the orientation of their models in this respect, probably owing to generalisedlack of knowledge of the topic. However, and this is one of the main points of thisarticle, the underlying postulates of such models can be discovered from their meth-odology and procedures.This paper examines how profitability and availability are treated in the most repre-

sentative word-formation productivity models, namely type and token frequency

4Corbin, 177.5Danielle Corbin’s distinction contemplates, in fact, three sides to morphological productivity: availability, profit-ability and regularity. Today, regularity is not analysed on a par with availability and profitability, even if it is stillperceived as a property of morphological processes (cf. Bauer, Morphological Productivity, 54–6). The reader isreferred to the following references for further details: Kastovsky, 586; Spencer, 48–9; Plag, Morphological Pro-ductivity, 34.6Zandvoort, 44; and Lyons, 76, respectively.7Sproat and Shih; Baayen, “Probabilistic Approaches”; Nishimoto.

Morphological Productivity Measurement 423

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Jesú

s Fe

rnán

dez-

Dom

íngu

ez]

at 0

8:55

30

June

201

3

(2.1.1), the probabilistic models by R. Harald Baayen (2.1.2) and Jennifer Hay (2.1.3),Pavol Štekauer’s onomasiological approach (2.2) and a new proposal (2.3). To do so, Iprovide details on the theoretical foundations of each proposal and then illustrate theirprinciples by applying them to a BNC-derived corpus.8

2. Approaches for Productivity Measurement: Description and Application

As explained in the previous section, Berschin’s is often taken to be the first proposaltowards productivity measurement. This method, however, was overlooked until MarkAronoff’s relativised approach,9 which is essentially based on the same tenets asBerschin’s method but is framed within a generative conception of word-formation.The formulation of the relativised approach was undertaken years later by Baayenand Rochelle Lieber who, following Aronoff, suggest the formula below, where I isthe index of productivity, V is the number of actual words of a given process, and Sthe number of possible words of that process:10

I = V/S

The highest possible value for I is 1, and occurs when an affix has exhausted all its poss-ible bases (S) by creating the maximum possible number of derivatives (V). Thisformula pioneered work in productivity measurement but it was soon abandonedgiven the difficulties in its application, especially when it comes to providing an unam-biguous figure for S, the number of possible words.11

More recent proposals have preserved some ideas from the above models (forinstance, the heritage of a performance lexicon from lexicalism, as in 2.1.2 and2.1.3) and, as a rule, have turned to the pioneers of productivity measurement usingmore advanced techniques. In this context, this paper looks at eight productivitymodels through a threefold division made based on the qualitative or quantitativeorientation of each proposal. Accordingly, I deal first with proposals of a quantitativekind (2.1), then go on to examine qualitative models (2.2) and conclude by presentinga method with features of both trends (2.3).The data used for the application of the productivity methods comes from BNC fre-

quency word-lists of two types. The first type covers the highest frequency ranges in theBNC, and therefore it is suitable for computations in most of the productivitymethods, namely those under 2.1.1, 2.1.3, 2.2 and 2.3. This word-list type is identifiedwith the ten frequency lists by Geoffrey Leech, Paul Rayson and AndrewWilson, whichcover a frequency range from 61,847 to 10. There is one list for each word-class and5,891 words in all. The second word-list type covers lowest frequency ranges in the

8The British National Corpus, version 2.9Aronoff, Word Formation, 36.10Baayen and Lieber, 802–6.11Cf. Aronoff, “Potential Words”; Plag, Morphological Productivity, 24; Bauer, Morphological Productivity, 145–6.

424 J. Fernández-Domínguez

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Jesú

s Fe

rnán

dez-

Dom

íngu

ez]

at 0

8:55

30

June

201

3

BNC corpus, and therefore complies with the needs of methods based on computationof hapaxes, namely the proposals by Baayen (see 2.1.2). This second type is identifiedwith Adam Kilgarriff’s list, which covers a frequency range from 6,187,267 to 1 andcontains 6,318 words.Affixation is the most productive word-formation process in Modern English.12

Perhaps for this reason, most of the methods have been designed and applied tomeasure the morphological productivity of affixes, in this study those in 2.1.Accordingly, the illustration of the internal theoretical mechanisms of the pro-ductivity methods is based on the computation of the ten most frequent affixes inthe corpus. However, this is applicable only to methods where measurement isassociated with morphological forms, but not to ones based on meanings, whichis the case of the onomasiological method. For the latter case, therefore, compu-tations will be not of affixes but of one conceptual field indicated in the productivitymethod.Previous preparation of the data was necessary before actual application of the

different productivity models. In the case of quantitative methods, the relevantword-lists were examined for affixed units. For easier computation of affixes, thelatter were classified in a tripartite categorisation system, exemplified in (1) below,which contains the affix and the syntactic categories of the base and of the resultingderivative.13 This allows classification of various affixes with the same external formunder separate entries, one according to each variant in the syntactic category of thebase or the resulting derivative.

(1) helpful NN− ful.AJ

For the onomasiological method, the ten high-frequency lists were examined for allderivatives in the conceptual field INSTRUMENT which is one of the possible fieldslisted for the method. As mentioned above, being based on meaning and not onform, this method will cover not just affixation but all word-formation processes rep-resented in the corpus. To verify directionality in cases of conversion the OxfordEnglish Dictionary (OED) was used.14

2.1 Quantitative Approaches

Morphological productivity has been understood by many as an oscillation in thenumber of coinages so that, broadly speaking, a process is more or less productivedepending on how often it is put into action. Various proposals exist for a quantitativeassessment of productivity, all of them sharing the assumption that a process is more

12Bauer and Huddleston, 1666.13The labels used for the syntactic categories are AJ for adjective, AV for adverb, DT for determiner, NN for noun,OR for ordinal and VB for verb. All examples come from the study corpus unless otherwise stated.14OED.

Morphological Productivity Measurement 425

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Jesú

s Fe

rnán

dez-

Dom

íngu

ez]

at 0

8:55

30

June

201

3

productive as it shows the capacity to coin more lexemes, hence their close associationwith profitability.

2.1.1 Type and token frequency. Within quantitative methods, the most widespreadtechnique consists in counting up the number of different words created by a word-formation process (i.e. types), with the result that the higher the figure, the higherthe productivity of the process. This operation is called type frequency (V) and isused in most works dealing with productivity measurement, partly due to its pro-cedural simplicity, partly because it can be combined with other data for morerefined formulae (see 2.1.2, 2.1.3 and 2.3). This method is relatively straightforwardto apply, since one just has to count up the different lexemes of a process and theresulting figure is V. Table 1 shows the results from the corpus:15

As could be expected, the results from V are directly determined by the attested formsof each affix because this model intends to echo the overall number of derivatives bythat process. The values in Table 1, therefore, are a clear reflection of how manylexemes in the corpus have been coined by these affixes.One of the main problems of V is that it may include in its computations figures

from already unproductive rules, such as VB-ment>NN, which they may rank ashighly productive (in seventh position in the case of VB-ment>NN).16 This is a signifi-cant downside of this model, and one which turns it into a blind one as far asavailability is concerned, because it utterly ignores the synchronic status of word-formation processes.A variant of V is token frequency (N), where the productivity figure is attained by

adding up not the different lexemes from a process, but all their occurrences, be itin different words or in repeated occurrences of the same word (i.e. tokens). Forinstance, if the word educational appears four times in a text and it is the only one

Table 1 Type Frequency (V)

Affix V

1 AJ-ly>AV 1932 VB-ing>NN 1043 VB-ed>AJ 954 VB-er>NN 675 VB-ing>AJ 546 NN-al>AJ 307 VB-ment>NN 228 NN-ful>AJ 169 un-AJ>AJ 1610 VB-al>NN 13

15Affixes are sorted out from more to less productive hereafter unless otherwise stated.16Cf. Bauer, Morphological Productivity, 205, for a claim of the unavailability of the suffix.

426 J. Fernández-Domínguez

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Jesú

s Fe

rnán

dez-

Dom

íngu

ez]

at 0

8:55

30

June

201

3

featuring the suffix -al, this suffix would have a V value 1 (because only one differentword in the text contains that suffix) and an N value 4 (because that word appears fourtimes). Application of N to the study corpus implies adding up all occurrences of theaffixes under study (Table 2).These results provide a very similar ranking of processes compared to those in Table 1,

AJ-ly>AV leading the list, followed by VB-ing > NN, VB-ed > AJ and VB-er > NN, theranking among the rest of affixes being practically identical.Another difference between the models is that it seems easier to compare the pro-

ductivity of different processes using the N figures, as finer nuances can be observedthanks to the higher figures it provides. Compare, as a token, the figures of VB-ing>AJ and NN-al>AJ in type frequency (54 and 30) and in token frequency (1,359and 1,082). Even if VB-ing>AJ is regarded more productive in both models, the Vfigures do not allow appreciation of the difference between the two processes indetail because of the numerical proximity of 54 and 30. By contrast, Table 2 showsthat these two processes differ considerably in their productivity, and that NN-al>AJis not as far down the productivity scale as it initially seems.A central feature of V and N is that they tell about the degree of generalisation of a

process, but they do not indicate whether it is available or not. As a result, these modelsmay embrace items which look like complex lexemes but are not, as may be the case oflexicalised units or loans from French.17 Moreover, not all morphologically complexunits are necessarily relevant as derivatives of a given affix because some may haveexisted for even longer than the process itself, with the consequence that “a straightcount may capture forms which were in use before any word-formation process hadarisen”.18

Table 2 Token Frequency (N)

Affix N

1 AJ-ly>AV 8,7422 VB-ing>NN 3,3893 VB-ed>AJ 2,7394 VB-er>NN 2,4185 VB-ment>NN 1,7476 VB-ing>AJ 1,3597 NN-al>AJ 1,0828 AJ-ness>NN 6489 NN-ful>AJ 61810 NN-ship>NN 449

17Dieter Kastovsky exemplifies this by arguing that not every word ending in -ion or -ive is synchronically relevantfor English word-formation, and that sometimes the units existed individually in French. This is the case of theseries deceive > deception > deceptive, where no word-formation has taken place in English, and which rules out anybase > derivative relationship (cf. Kastovsky, 589).18Bauer, Morphological Productivity, 144.

Morphological Productivity Measurement 427

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Jesú

s Fe

rnán

dez-

Dom

íngu

ez]

at 0

8:55

30

June

201

3

All in all, type and token frequency are relatively straightforward methods to applyand represented an initial stage when more sophisticated alternatives were not at hand.They are useful as complementary figures for other computations (see 2.1.2), and thishas set them as unavoidable methods for any productivity formula.

2.1.2 Baayen’s measure. By contrast to methods which focus on the attestation oflexemes, productivity has been approached also from a probabilistic-statistical per-spective, for example by Baayen, Ingo Plag and Hay.19 These lay emphasis on theidea that productivity is about possibility,20 so their goal is to achieve figures whichindicate the likeliness for a process to create new words in the future.These models differ from previous proposals in their reading of corpus figures

because, even if the values used are essentially the same in both cases (see below inthis section), their interpretations are totally different. For the models in 2.1.1, typesand tokens merely reproduce the productivity of a process up to the present withno further implications; they are descriptions of past productivity. Probabilisticapproaches are also based on corpus values but, in opposition to other models, theybelieve that proper mathematical operations can provide prospective accounts of pro-ductivity, calculating how possible it is for future coinages to be created by a given affix.Thus, probabilistic models go one step further because they are not restricted to a por-trayal of current trends, but they try to predict future tendencies.The first probabilistic proposals were devised by Baayen who, following Aronoff,

claims that productivity can be indirectly linked to N and assumes that the morecommon an item is, the fewer the chances for word-formation to operate. Accordingto Baayen and Lieber, the figures of hapax legomena can be used as evidence to perceivethe productivity rates of derivational affixes, if they are modulated together with severalother values.21 The grounds for this belief are that, according to psycholinguistic views,frequency favours that items get stored in the mental lexicon and be accessed as wholesrather than through parsing, which means that speakers fail to perceive the internalcomposition of lexemes (bases, suffixes, prefixes, etc.).22 This is typical of high-fre-quency units and, in turn, of unproductive processes; in fertile processes, by contrast,so many lexemes are created that the frequency is shared among all of the units, withthe result that the ratio of frequency per unit is lower. That is why lower frequencies aretypical of productive processes, which explains the central role of hapaxes in Baayen’smodels: if they are units which are seldom accessed, they symbolise those words thatare not frequent and are parsed to be understood (for a similar proposal, see 2.1.3).Various formulae have been devised following the above postulates, the first of

which is productivity in the strict sense (P), obtained by dividing the number of

19Baayen, “On Frequency”; Plag, Morphological Productivity; Plag, Dalton-Puffer and Baayen; Hay, Causes andConsequences.20Cf. Schultink, 113.21Hapax legomena are words that occur only once in a corpus, that is where N = 1 (cf. Baayen and Lieber, 809).22Aronoff, “Potential Words”; McQueen and Cutler.

428 J. Fernández-Domínguez

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Jesú

s Fe

rnán

dez-

Dom

íngu

ez]

at 0

8:55

30

June

201

3

hapaxes of the process in question (n1) by the token frequency of that process (N), andwhere the higher the figure the higher the productivity of the process. This is formu-lised as follows:

P = n1/N

According to Baayen, P is not intended as a straight measurement of productivity,but as an indirect indication of how likely it is to find a previously unknown itembased on existing data.23 Given that words tend to have higher frequencies as theyendure in the language, coinages are assumed to be, in general, infrequent items,which naturally links them up with hapaxes due to the frequency 1 of the latter. There-fore, if a process is regarded as productive when it creates new derivatives steadily,having a high value for n1 denotes that the process in question contains many low-fre-quency units which, in turn, automatically means that there is a high probability offinding more low-frequency items (i.e. neologisms) from that process in the future.This is one of the pros of this model because, despite being based on attested data,it is in theory able to predict future productivity rates. These are the results after appli-cation of P to the corpus (Table 3).24

A remarkable fact in Table 3 is that nine of the affixes are noun-creating rules, andonly NN-ed>AJ, the most productive of the set, gives rise to lexemes of a differentword-class (observe that, as in some cases of type and token frequency, this suffixcan be argued to be an inflectional one). With regard to the productivity ranking,the figures displayed by P here are very high if compared to the experiments byBaayen, which may be caused by the requirement of these models to be operated ona large-size sample (the author uses an eighteen-million-word corpus). This

Table 3 Productivity in the Strict Sense (P)

Affix n1 N P

1 NN-ed>AJ 224 1,800 0.12442 NN-y>NN 99 1,000 0.09903 AJ-er>NN 101 1,200 0.08414 NN-y>NN 99 2,200 0.04505 VB-y>NN 99 3,500 0.02826 AJ-s>NN 472 19,000 0.02487 in-NN>NN 21 1,100 0.01908 VB-tion>NN 26 1,300 0.02009 NN-s>NN 472 26,100 0.018010 VB-s>NN 472 29,900 0.0157

23Baayen, “On Frequency,” 183.24Given the different frequency ranges of the two word-lists used here (61,847 to 10 vs. 6,187,267 to 1, see section2), the N values of the former were multiplied by 10,000 to make the frequencies compatible with Kilgarriff’sword-list (cf. Leech, Rayson, and Wilson, for further details on this point).

Morphological Productivity Measurement 429

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Jesú

s Fe

rnán

dez-

Dom

íngu

ez]

at 0

8:55

30

June

201

3

particularity of Baayen’s models, reported also in other studies,25 makes one uncertainif the above results are triggered by a variable corpus size only or if they represent thedifferent productivity of affixes with accuracy.Baayen’s models have undergone a number of modifications along the years, always

giving hapaxes a central position. One of these revisions is the hapax-conditioned degreeof productivity (P∗), which tries to account for the productivity of affixes by dividing thenumber of hapaxes containing the affix under study (n1, E, t) by the total number ofhapaxes in the corpus (ht):

P∗ = n1,E,t/ht

The underlying idea in P and P∗ is essentially the same as the previous proposal, namelythat hapaxes provide hints of morphological activity but, while the former dis-tinguishes between productive and unproductive rules, the latter is “particularlysuited to ranking productive processes according to their degree of productivity”.26

Accordingly, P and P∗ are to be applied complementarily, since they play differentroles in productivity measurement. The ten top productive affixes for P∗ are givenin Table 4.As with P, most of the affixes considered very productive by P∗ are noun-forming

rules, with the exception of VB-ed>AJ and NN-ed>AJ, which is in principle a signof agreement between both models. Similarly, all the items in Table 4 are suffixes,which was also the case in Table 3 with a nine out of ten ratio.Even if, as Baayen argues, the effectiveness of P∗ lies in that it contrasts the hapaxes of

an affix with the hapaxes from the whole corpus (ht), we cannot appreciate the ultimatedifference between including the latter figure in the computation and leaving it aside. Inmy view, the ht figure (here 411,573) loses its significance because it is constant for all

Table 4 Hapax-Conditioned Degree of Productivity (P∗)

Affix n1, E, t ht P∗

1 AJ-s>NN 47,226 411,573 0.11472 NN-s>NN 47,226 411,573 0.11473 VB-s>NN 47,226 411,573 0.11474 VB-ed>AJ 22,418 411,573 0.05445 NN-ed>AJ 22,418 411,573 0.05446 VB-er>NN 10,109 411,573 0.02457 NN-er>NN 10,109 411,573 0.02458 AJ-er>NN 10,109 411,573 0.02459 NN-y>NN 9,968 411,573 0.024210 NN-y>NN 9,968 411,573 0.0242

25Cf. Bauer, Morphological Productivity, 148–9; Gaeta and Ricca.26Baayen, “On Frequency,” 205.

430 J. Fernández-Domínguez

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Jesú

s Fe

rnán

dez-

Dom

íngu

ez]

at 0

8:55

30

June

201

3

affixes, and this means that, where there is a high number of hapaxes (n1, E, t), the figuresfor P∗ will be correspondingly high, and vice versa. This can be observed in Table 4,where the ranking provided by the column P∗ is mirrored by that provided by thecolumn of the hapaxes of affixes (n1, E, t). If, in Baayen’s words, P∗ is useful to rankaffixes according to their productivity,27 one cannot but wonder whether there is some-thingmore to these computations than the figures of hapaxes themselves or, if not, whatis the role played by the ht figure here.The third major proposal by Baayen is global productivity (P∗) and is represented on

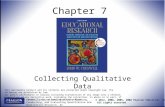

a graph with the figures of V and P by placing the former on the vertical axis of a chartand the latter on the horizontal one. The major characteristic of P∗ is that, because highvalues of V and P cause affixes to move up and towards the right on the chart, the moretowards the top right-hand corner an affix appears the more productive it can beregarded, and vice versa. Figure 1 stems from application of P∗ to the corpus.The main asset of P∗ is that it allows examination of the values of V and P simul-

taneously and, in turn, assesses their productivity jointly, which should mean a defini-tive method to measure the productivity of affixes. Part of the motivation to include Vas a figure here is that it serves to disambiguate the productivity rates between twoaffixes when their P values are very close together;28 theoretically, then, P∗ meets allrequirements to be an all-embracing model.The model’s undeniable pros, however, collapse because the format of Figure 1 does

not allow drawing definitive conclusions about affixes. Despite the advantages of dis-playing V and P simultaneously, it proves unfeasible to compare the productivity ofvarious processes, because it is impossible to assess both figures separately in practice.

Figure 1 Global Productivity (P∗).

27Ibid.28Baayen and Lieber, 809.

Morphological Productivity Measurement 431

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Jesú

s Fe

rnán

dez-

Dom

íngu

ez]

at 0

8:55

30

June

201

3

It is hence unviable to pick up the top-ten productive affixes from Figure 1, as P∗ doesnot supply the required tools to do so.These difficulties may be illustrated by comparing the positions of three affixes, NN-

al>AJ, NN-y>AJ and in-NN>AJ in Figure 1. According to the model’s postulates, itseems evident that NN-al>AJ is more productive than NN-y>AJ because it occurshigher on the chart, and that in-NN>AJ is more productive than NN-y>AJ becauseit appears more towards the right. The positions of these affixes are sufficient proofof their productivity value. However, Figure 1 does not reveal whether NN-al>AJ ismore productive than in-NN>AJ or if the situation is the opposite, since P∗ favoursthe former regarding the V axis and it favours the latter regarding the P axis. As aresult, no decision can be taken on this issue without a certain degree of uncertaintyor, at least, running the risk of making uncertain assumptions about productivity.The above represents a serious obstacle, caused by the different values of both axes,

whose figures derive from different numerical measures (namely V and P) but areforced here to fit within the same visual parameters. The resulting output, as can beexpected, is a chart where the positions of affixes are relative among themselves and,for this reason, the guesses about Figure 1 ultimately depend on the separate figuresof V and P. In consequence, one has to be cautious when interpreting the resultsfrom P∗ because, despite the apparent simplicity of their layout, most affixes are notdirectly comparable among themselves, and only those with close positions (e.g.NN-al>AJ vs. NN-y>AJ, or in-NN>AJ vs. NN-y>AJ) enable an unequivocal appraisalof productivity.All in all, Baayen’s models have taken a decisive role in productivity measurement

thanks to their ability to connect a generative conception of word-formation(namely, Aronoff’s) with a probabilistic-statistical approach to morphology. Theseproposals, nevertheless, are not without problems, which come mainly from the meth-odology they employ. For example, the condition of large-size corpora of Baayen’smodels comes on top of the impossibility of contrasting the outcome of thesemodels if different corpora have been used because, as pointed out by LaurieBauer,29 the N figures are too sensitive to corpus size, and this necessarily reducesthe reliability of any comparison. Moreover, as noted in the literature,30 Baayen“seems to assume perfectly prepared corpora” despite the fact that current corporacontain an important number of errors which very often occur only once. Preciselybecause these errors happen once, they count as hapax legomena in Baayen’s formulaeand, in turn, have a dramatic effect on the final results.Furthermore, it sometimes seems that Baayen’s models lack the support of a suffi-

ciently consistent morphological theory to fully account for some of the results theyprovide, for example the unawareness of the notion of availability. These facts makethe above models a perfectly valid option, but one must be aware that they are apt

29Bauer, Morphological Productivity, 148.30Lüdeling, Evert, and Heid, 3.

432 J. Fernández-Domínguez

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Jesú

s Fe

rnán

dez-

Dom

íngu

ez]

at 0

8:55

30

June

201

3

for computations on quantitative productivity only because, given their methodology,they simply ignore the qualitative side of the phenomenon.

2.1.3 Hay’s measure. Besides Baayen’s proposals, an innovative alternative is the rela-tive frequency model by Hay which, although enclosed also within a probabilistic-stat-istical approach, takes a slightly different stance to productivity.31

In examining a given affix, Hay takes into consideration not only the frequency of itsderived words, but also that of their lexical bases, based on the belief that listedness inthe lexicon makes lexemes indivisible as regards morphological processes. Hay claimsthat productivity is higher in processes where the derivatives are less frequent than thebases and vice versa, because when a derivative is repeatedly employed (e.g. illegible)speakers learn its semantics by heart, so they do not need to parse the lexeme (herei- + legible) for understanding. The figure for relative frequency (RF) is obtained bydividing the N figure of the derivatives (Nd) by that of the lexical bases (Nb):

RF = Nd/Nb

As with all proposals reviewed up to this point, the relative frequency model is essen-tially aimed at affixation. In this case, the most important step is the identification ofthe lexical bases of all corpus entries, which is relatively straightforward in suffixation,prefixation or back-formation, as the identification of the base and derivative relation-ship is apparent on most occasions, for example vocation > vocational, appropriate >inappropriate or body > embody. For these purposes, all lexical bases are located,their frequencies retrieved from Kilgarriff’s list and the formula is applied.Once the criterion for the recovery of lexical bases was settled, the above operation

was undertaken on all corpus entries, after which the N figure of all lexical bases isavailable. Now, using these figures together with the N of the derivatives, it is possibleto execute the relative frequency model. In this case, given that the model presupposesan inverse relationship between the bases and their derivatives, the most productiveprocesses are those with a lower RF figure, and vice versa (Table 5).A number of unexpected details emerge from the application of Hay’s model to the

study corpus, the first of them that the top-ten ranking includes four prefixes, a highfigure compared to the results of other models. The first positions of the table are occu-pied by elements where the lexical base is much more common than the derivative, forexample AV-er > AJ, where the base (out) has a much higher frequency than thecomplex lexeme (outer). The same happens with AJ-ism > NN (national >nationalism).On the lower part of the table appear the prefix un-AV > AV (usually > unusually)

and AJ-hood > NN (likely > likelihood), where the derivative/base ratio is favourable tothe derivative. It must be stated, in relation to these figures, that the majority of these

31Hay, “Lexical Frequency”; Hay, Causes and Consequences; Hay and Baayen.

Morphological Productivity Measurement 433

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Jesú

s Fe

rnán

dez-

Dom

íngu

ez]

at 0

8:55

30

June

201

3

affixes comprise very few derivatives in the study corpus, which causes the frequency ofthe base to play an even greater role in the computations than it usually does. As a con-sequence, the figure obtained from the above formula is very low, and this explains thelow N figures in the Nd column in Table 5.Overall, Hay’s proposal stands as an original improvement in the field of pro-

ductivity, and has as its chief innovation the fact that it includes not only the frequencyof the derivatives but also that of their lexical bases. In this way, the author has devel-oped a model based on morphological theory in combination with a psycholinguisticapproach to the lexicon, also providing insights to the field of phonotactics.32 Onepossible problem of the model, besides its limitation to affixation, is how to accountfor diachronic changes in productivity, as the frequencies of lexemes experienceongoing changes in time, and this would naturally affect the statistics of the relativefrequency model.33 It is to be expected that Hay’s ratio would adapt to thesechanges, but this will be checked once her formula is applied in diachronic studies.

2.2 Qualitative Approaches

As opposed to scholars who identify productivity with the number of new formationsof a process in absolute terms, an alternative viewpoint judges that there is more to thephenomenon than straight counts. Specifically, qualitative views believe that pro-ductivity is not a matter of only frequency, but also of factors like the limitations onthe lexical bases of morphological processes, a stance which stands close to thenotion of potentiality, intrinsic to many definitions of productivity.34

Although various scholars have raised awareness of the qualitative features of pro-ductivity,35 no explicit proposal for its measurement has been made besides Štekauer’s

Table 5 Relative Frequency

Affix Nd Nb RF

1 AV-er>AJ 2,400 150,958 0.01582 AJ-ism>NN 1,000 37,221 0.02683 OR-ly>AV 6,600 171,594 0.03844 out-NN>AJ 1,100 25,360 0.04335 NN-ful>NN 1,500 34,357 0.04366 fore-NN>NN 1,400 31,925 0.04387 en-NN>VB 1,200 25,043 0.04798 NN-less>AJ 5,500 106,107 0.05189 un-AV>AV 1,000 19,151 0.052210 AJ-hood>NN 1,200 22,592 0.0531

32Hay, Causes and Consequences, 160–80.33Cf. Cowie; Bauer, “Productivity: Theories,” 328.34Schultink, 113; Plag, Morphological Productivity, 22; Bauer, Morphological Productivity, 14.35Booij, 121; Spencer, 48; Dressler and Ladányi, 119.

434 J. Fernández-Domínguez

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Jesú

s Fe

rnán

dez-

Dom

íngu

ez]

at 0

8:55

30

June

201

3

model.36 This work is framed within an onomasiological conception of word-for-mation and is aimed at highlighting the semantics of derivatives, by contrast to preced-ing works, which have habitually focused on their formal structure. In Štekauer’stheory, the speaking community motivates all coinage and, depending on its particularneeds, either a new lexeme is produced or an existing one is used. This implies athorough dissection of the naming process which takes into consideration all stepsin the coinage of a unit and keeps a connection between “the ever-changing extra-linguistic reality and the related language requirements of the particular speechcommunity”.37

According to the onomasiological model, when a speaker has a naming need, one oftwo alternatives comes up: the required concept may be appropriately expressedthrough an existing naming unit (hereafter NU) or, otherwise, word-formation is acti-vated and a new derivative is created.38 This is, hence, a lexicon-based theory in that allnew NUs are formed based on existing material from the lexicon, and no use is made ofsyntax or the speech level for new constructions.As for word-formation rules, Štekauer deems them to be 100 per cent productive as

far as cognitive notions are concerned, as opposed to views which perceive syntax asfully productive versus word-formation as hindered by constraints of varioustypes.39 This feature allows this model to dispose of the delicate demarcation pro-ductivity versus creativity which, although discernible in the theory, is not easy topin down in practical terms.40

The theoretical schema of the onomasiological model proves to be of major signifi-cance when it comes to productivity measurement because, as has been said, Štekauer’sproposal focuses on the semantic side of NUs rather than on their structural make-up.It is for this reason that the process of productivity counts takes here a different coursethan in other models and, instead of analysing units based on types of word-formationprocesses (affixes, compounds, converted units, etc.), productivity is here computedwithin clusters of meaning, for example AGENT, INSTRUMENT, PATIENT, LOCATION,

FACTITIVE and so forth.Productivity measurement of the label [+AGENT], for example, implies scanning all

NUs that bear an agentive sense, regardless of whether the unit has been derivedthrough compounding, affixation or any other word-formation process. As aresult, a list is obtained with all the NUs with the label [+AGENT], which Štekauer

36Štekauer, Onomasiological Theory; Štekauer, “Fundamental Principles”; Štekauer, “Onomasiological Approach”;Štekauer et al.37Štekauer, “Fundamental Principles,” 5.38In this theory, the term naming unit is equivalent to word, lexeme or lexical unit (cf. Štekauer, “OnomasiologicalApproach”; Štekauer et al.).39Chomsky; Baayen and Lieber.40Productivity has been claimed to include rule-governed coinages, while creativity takes in any other kind ofoutput, for example literary texts, playful formations or terminological units (cf. Dressler and Ladányi, 105;Bauer, Morphological Productivity, 62–71). However, to the best of my knowledge, no study has clearly separatedthem in practical terms.

Morphological Productivity Measurement 435

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Jesú

s Fe

rnán

dez-

Dom

íngu

ez]

at 0

8:55

30

June

201

3

calls a Word-Formation Type Cluster (hereafter WFTC) and, depending on theirstructure, each NU is allocated to one of the onomasiological types into which eachWFTC is internally divided. The five existing onomasiological types are establishedbased on the formal structure and distribution of the constituents of lexemes,which is the closest equivalence between traditional word-formation processes andthe onomasiological theory. Type I is the closest to explicitness of expression (e.g.landowner), and occurs in units which encompass, for instance, an OBJECT (land),an ACTION (own) and the corresponding agent (-er), while type V is the closest toeconomy of speech, represented by the process of conversion (e.g. intellectualN

derived from intellectualAJ); the remaining three types take intermediate positions.Thus, type II and III occur when the right-hand or the left-hand constituent is leftunexpressed, respectively. In the former case, it is the so-called determined constituentof the onomasiological mark that is elided: an item such as writer comprises ACTION

(write) and AGENT (-er). In the latter case, that is type III, the missing element is thedetermining constituent of the onomasiological mark: in honeybee, only the OBJECT

(honey) and the AGENT (bee) are present. As to type IV, it includes items where theonomasiological mark cannot be analysed into the determining and determinedparts, and are hence regarded as simple structures in this model, as in lionhearted.A central characteristic of WFTCs is that, in accordance to the model’s postulates,

each of them is 100 per cent productive, which means that productivity is computedwithin WFTCs, that is for semantic labels, and not across word-formation processes.This is one of the pioneering features of the present model and one which makesthe difference between it and traditional approaches to productivity.It is precisely the fact that WFTCs are always 100 per cent productive that settles this

model as a qualitative one because, if productivity never falls below 100 per cent, prof-itability is not a pertinent question and everything becomes a matter of availability. Inthis case, it was determined to search for NUs of the WFTC INSTRUMENT to illustratehow this model is operated (Table 6).As can be seen on top of Table 6, there are forty-one NUs in the study corpus with

the label [+INSTRUMENT], which are then distributed among the five onomasiologicaltypes (the areas shaded grey). In this case, the highest productivity index is displayed bytype III (73.170%), followed by type II (21.951%) and then type IV (4.878%), while noNU is reported for types I and V. Even if it is difficult to establish formal comparisonbetween traditional word-formation processes and the onomasiological types, it can besaid that type III includes root compounds (aircraft, desktop, railway, timetable) and, ingeneral, units where the action is omitted (booklet, bowler, inland, leaflet). According tothe results, this is the most productive structural combination when creating a newlexeme with an instrumental meaning. Also observe that NUs are distributed notonly into the five onomasiological types, but that, within each of these, there arefurther subdivisions according to the specific semantics of the unit, for exampleACTION, LOCATIVE, MANNER, QUALITY and so forth.From the above, it becomes evident that the onomasiological approach requires a

much closer inspection of the data than statistics-oriented views like Baayen’s by

436 J. Fernández-Domínguez

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Jesú

s Fe

rnán

dez-

Dom

íngu

ez]

at 0

8:55

30

June

201

3

reason of its focus on the semantics of word-formation. As has been shown, Štekauer’sanalysis is conducted by seeking specific semantic content across NUs, and thisdemands a one-by-one examination of lexemes, which explains why this model isoften operated on medium-size samples.41 This is in fact a natural consequence ofthe meaning-oriented analysis which the onomasiological theory looks for, andentails that the results obtained are highly reliable because the previous scrutiny ofNUs is careful and very detailed.

2.3 Hybrid Approaches

In view of the tendencies of the existing models, an alternative is described by JesúsFernández-Domínguez which proposes a measurement of productivity based on thecombination of qualitative and quantitative factors.42 Here, a number of theoreticalassumptions serve as the basis for operating a corpus-based formula of productivityvalues.

Table 6 Productivity of the WFTC INSTRUMENT

Total number of NUs 41 100%

Type NUs Productivity

Onomasiological Type I – –

Onomasiological Type II 9 21.951%1. ACTION – SUBSTANCE(a) Action – Instrument 9 21.951%

Onomasiological Type III 30 73.170%1. SUBSTANCE – SUBSTANCE(a) Object – (Action) – Instrument 8 19.512%2. CONCOMITANT CIRCUMSTANCE – SUBSTANCE(a) Locative – (Action) – Instrument 16 39.024%(b) Locative – Action 2 4.878%(c) Quality – Instrument 1 2.439%3. QUALITY – SUBSTANCE(a) Instrument – (Act) – Quality 2 4.878%(b) Quality – Instrument 1 2.439%

Onomasiological Type IV 2 4.878%1. CONCOMITANT CIRCUMSTANCE – SUBSTANCE(a) Manner – Instrument 2 4.878%

Onomasiological Type V – –

41Cf. Štekauer, Onomasiological Theory; Fernández-Domínguez, Díaz-Negrillo, and Štekauer; Štekauer, “Funda-mental Principles”; Štekauer et al. In these studies, the study sample never exceeds 350 naming units. Note thesharp contrast between this figure and R. Harald Baayen’s habitual eighteen-million-word corpus (Baayen andLieber, 801–5).42Fernández-Domínguez, 147–69.

Morphological Productivity Measurement 437

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Jesú

s Fe

rnán

dez-

Dom

íngu

ez]

at 0

8:55

30

June

201

3

One of the cornerstones of this model is the denial of productivity prediction.Similarly to other views,43 naming needs are here set as the motivating force forword-formation so, if no naming need exists, no productive word-formation cantake place.44 It naturally follows, therefore, that calculating future productivity ratesis no less than a fallacy for a theory like this, because productivity is here linked tothe necessities of the speech community, and foretelling these needs seems at leastimprobable. The consequence is that, unlike the work by Baayen or Hay, this modeldoes not go beyond a description of the present trends of productivity, regardless ofwhether they may remain constant in the future or not.In this case, the differentiation availability versus profitability is made based on a

careful examination of the word-formation process under discussion. As has beenshown, frequency figures can hardly offer hints about the availability of word-formation processes because they reflect attestation of units and, hence, pointtowards the quantitative and not towards the qualitative aspect of productivity.Bearing this in mind, a two-step analysis is proposed for computations on productivitywhere the first stage looks at qualitative productivity and the second one at quantitativeproductivity. This ensures that only relevant processes are considered for the definitiveanalysis:

i) Detection of the synchronic status of the process under study in terms of avail-ability.45 Only processes with the feature [+AVAILABLE] are considered for phaseii), while those which are proved to be inactive are set aside and their productivityindex automatically set to zero.

ii) Measurement of the productivity index based on corpus frequencies. Here, theprocesses preserved from step i), that is those confirmed to be available, are ana-lysed and their productivity compared, so a ranking can be established.

This second stage entails the application of the indicator of profitability (π) which, as itsname indicates, focuses on the quantitative side of productivity, as its qualitative sidehas already been accounted for in phase i).The figures required for π are type frequency (V) and token frequency (N), under the

assumption that V represents the number of different lexemes coined by a process,while N symbolises the total number of occurrences of that process. The hypothesisof π is that V tends to be high in productive processes because the more productivea process has been, the more different units it has (and hence higher V); the oppositehappens for less productive processes. By contrast, it is a well-known fact that N tendsto be higher for unproductive than for productive processes, since the same units are

43Kastovsky; Štekauer, “Fundamental Principles.”44See fn. 40.45Even if this model is here applied only to affixation for the purposes of this article, its scope makes it possible toapply it to any word-formation process. Cf. Fernández-Domínguez for an application of the model to N + Ncompounding.

438 J. Fernández-Domínguez

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Jesú

s Fe

rnán

dez-

Dom

íngu

ez]

at 0

8:55

30

June

201

3

repeatedly used in the former but not in the latter (given that in productive processesnew units are regularly created and frequency disperses).46

If so, it can be argued that the relationship between V and N will be favourable to Vin productive processes and favourable to N in less productive processes, a hypothesiswhich is formulised as:

p = V/N

where the highest possible value of π is 1, and occurs when one type (V value 1) hasbeen used as infrequently as possible (N value 1), thus denoting the morphological fer-tility of the process.47

One requirement of π is that there needs to be a sufficient number of types of theprocess under study for reliable results, a figure called the Minimal V-Input (hereafterMVI). In the study corpus, for instance, many affixes have a V value of 1 and 2 and, ifthe above formula is applied straightforwardly, the figure obtained is often high due totheir proportionally low N value. But, despite this high π figure, these affixes have to beset at the bottom of the ranking because the fact of having a too low V already meansthat the process is not profitable, and it is unnecessary to take any further step in thecomputations. The MVI is dependent on the number of tokens analysed (the larger thecorpus the lower the MVI) and, in this case, it represents 0.05 per cent of the overallcorpus size. Once the previous steps have been taken, π can be applied to obtain the tenmost productive affixes (Table 7).48

Table 7 Indicator of Profitability (π)

Affix V N π

1 AJ-ance>NN 3 35 0.08572 NN-ate>VB 3 39 0.07693 AJ-en>VB 4 53 0.07544 NN-less>AJ 4 55 0.07275 NN-er>NN 5 74 0.06756 AJ-al>AJ 4 73 0.05477 NN-an>AJ 4 74 0.05408 AJ-ic>AJ 3 56 0.05359 NN-ise>VB 7 137 0.051010 VB-ive>AJ 4 81 0.0493

46Cf. Aronoff, “Potential Words”; Bauer, Morphological Productivity.47The use of V and N for productivity measurement was declined in 2.1.1 given their objectionable use as straightcounts. However, it should be emphasised that such a rejection refers to the use of type and token frequency inisolation, that is as direct computations of productivity. The present proposal, by contrast, is to modulate suchfigures in order to obtain a sign of what they may indicate about a given morphological process, regardless ofthe implications that V and N may individually carry.48Note that π is an approximation towards the profitability of word-formation processes and not towards theirproductivity in global terms. Precisely for this reason, it can be applied only to available processes (cf. Fernán-dez-Domínguez, 154–6).

Morphological Productivity Measurement 439

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Jesú

s Fe

rnán

dez-

Dom

íngu

ez]

at 0

8:55

30

June

201

3

As can be seen, the ranking of affixes is dependent on the V/N ratio and not onindividual figures, which is advantageous in that having a high V or N value does notnecessarily entail a high π figure. This is evident in affixes like AJ-ic>AJ (eighth position)orAJ-en>VB (third position), because the fact that the former has a lowVdoes not implythat it has a high π value, and the fact that the latter has a highN does not entail a low π.It is remarkable that the results in Table 7 display a preponderance of adjective- and

verb-creating affixes, while nouns are here a minority, as opposed to what happens inother models. Also note that all the items are suffixes, which contrasts with the resultsof other models, where prefixation is always present to some extent.Observe that the values displayed by affixes are quite close together among them-

selves and the difference between the top and the bottom of the list is only 0.04,which theoretically points at similar degrees of profitability among these affixes.This implies that, even if AJ-ance > NN is the most productive affix of the set, thesecond and third (NN-ate > VB and AJ-en > VB) are placed very close to it, so onemust be careful when assessing their overall profitability values.

3. Discussion

Section 2 has described the core aspects of eight productivity models and has justifiedtheir qualitative or quantitative orientation by assessing their tenets and methodology.I will at this point tackle the availability–profitability divide from a broader perspectiveand discuss to which extent each proposal is able to measure these two notions.Profitability seems to be a rather tangible concept, a relatively concrete feature of

word-formation. According to the definition in section 1, it has to do with howmany derivatives a process creates so, if we abide by this description, one simply hasto add up the number of new lexemes of a process and the resulting figure is its profit-ability. Following such a procedure has the advantage that it tallies with a rigorous viewof profitability as a quantitative notion, since the oscillation in the number of lexemesdirectly indicates the degree of profitability of the process and, furthermore, it allowscomparison between various rules (see 2.1.1).As seems evident, the models which come nearest to the above view of profitability

are type and token frequency, since they limit themselves to straight counts to reflectthe activity of a process, which is clearly noticeable from Tables 1 and 2. Albeit showingdifferences in their methodology, both V and N are directly based on the number ofderivatives of word-formation, and this automatically sets them as quantitativemethods which, however, pose certain shortcomings. Procedural precautionsapart,49 the main weakness of these models is that they assume that the past profitabil-ity of processes is kept constant in the present, an association which is by no means thecase.50 This gives away not only the unawareness of V and N productivity as composed

49See fn. 17.50Hay and Baayen, 101; Plag, Word-Formation in English, 205–6.

440 J. Fernández-Domínguez

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Jesú

s Fe

rnán

dez-

Dom

íngu

ez]

at 0

8:55

30

June

201

3

of availability and profitability, but also an invariable, and hence simplistic, view ofquantitative word-formation.Baayen’s and Hay’s measures, in the second place, are clearly positioned towards

quantitative productivity computations as well, and they have in common with Vand N their all-encompassing lexeme counts, that is an affix is chosen and thecorpus is scanned for formally matching units. Probabilistic models, however, differfrom earlier measures in essentially two aspects. One is that corpus figures are heremodulated in different ways. For example, in P the number of hapaxes of theprocess is divided by its N; in P∗ the formula is identical to P but it replaces the Nvalue with the total of hapaxes in the corpus (n1, E, t); in the relative frequencymodel, the N of the derived (Nd) and the base lexemes (Nb) are processed correspond-ingly too. None of these models, therefore, is restricted to a single corpus-derivedfigure, but they always adjust values depending on their specific purposes, a featurewhich distances them from straight counts like V and N (and, consequently, from anarrow conception of profitability).The second basic difference between statistical approaches and previous proposals

lies in their opposite interpretation of results. Because Baayen and Hay operate froma statistical-probabilistic perspective, the values from their models are to be interpretedas predictions of productivity rates, not as mere indicators of past activity. Thus, havinga high P value does not imply only that a given affix has a propitious n1/N ratio asregards attestation of units, but also that the chances for that affix to produce futurecoinages are strong. Similarly, low figures in Hay’s model reveal that speakers find iteasy to parse lexemes that contain the affix in question, which in turn leads to highchances of future productivity for that affix.Bearing the above in mind, it seems safe to regard statistical-probabilistic models as

quantitative, while being conscious that they do not portray so restricted a view of prof-itability as type and token frequency do. At this point, it may be worth noting a tra-ditionally disregarded differentiation whereby Corbin perceives two subtypes ofprofitability: generalisation and potential profitability.51 Generalisation concerns thedegree to which a process has spread its derivatives in language, while potential profit-ability is related to the capacity of a process for future creations; put simply, the formerentails looking at past profitability from a present perspective, and the latter impliesforeseeing future coinages. With this in mind, it can be asserted that Baayen’smodels focus not only on profitability in general terms but, moreover, that P and P∗

complement each other insofar as P measures generalisation, while P∗ focuses onpotential profitability. This is a connection which, to my knowledge, remains disre-garded in the literature and one which could confirm that these two formulae assessprofitability by operating jointly.All in all, a conclusion about the models reviewed up to now is that V andN embody

profitability seen from a primary point of view, that is by equating it with plain

51Cf. Corbin, 177; Bauer, Introducing Linguistic Morphology, 61.

Morphological Productivity Measurement 441

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Jesú

s Fe

rnán

dez-

Dom

íngu

ez]

at 0

8:55

30

June

201

3

attestation of forms, while statistical models present a more refined view, that is theyalso seek quantitative computations but they use formulae and adjust the figures formore polished analyses. Nevertheless, the models above may lend themselves to anerroneous interpretation of results because, even if they are theoretically capable ofestimating profitability, the notion of profitability itself is highly dependent on avail-ability. This becomes clear because, when measuring the profitability of a process,we do not normally wish to retrieve each and every one of its coinages since it hasexisted (at least not in synchronic studies), but we select a given lapse of time, andthis limitation of time inevitably brings in the notion of availability.Availability, by contrast to profitability, is a rather abstract concept, an idealised

notion of when processes can or cannot be operated. An initial problem with theidea of availability can be found in the use of processes itself. On the one hand,there is no doubt that when coinages occur in a representative text, the word-for-mation process involved therein is available, not in vain is its creative powershowing. Nevertheless, what is the situation of processes which seem to have been inac-tive for a relatively short period of time, for example the suffix -nik?52 In cases like this,the morphological activity of the process is recent, and the boundaries of the avail-ability/unavailability division become fuzzy. Two options are at hand here: the firstone is to assume that a process is available only when there is evidence that it iscoining new items; the second is to state that all processes are constantly available(even if they are not producing lexemes), arguing that they are latent, waiting to beemployed.None of the above alternatives seems to be totally satisfactory, the first one because it

makes availability synonymous with profitability (since coinages would determine the[un-]availability of processes), the second one because, if we claim that processes arealways accessible, this would make of availability a futile notion (why have a featurewhich says nothing about the status of rules?). Moreover, one must be cautiousabout coinages which apparently represent productive word-formation but are infact cases of creativity (bearhood, cathood, cubhood, doghood, etc.) or individualcoinages, not really representative of the trends of the speech community.53 All thisillustrates the complexity of qualitative productivity, a fuzzy notion which has notbeen unanimously characterised in theoretical terms and which, for that reason, is dif-ficult to gauge in the present state of things.According to this, it can be understood why the onomasiological model is a highly

availability-oriented one. First of all, Štekauer explains that when a process cannot coina NU, this is not particularly relevant because it may be that speakers prefer to use adifferent process on that occasion, and this does not have tragic consequences for

52Bogdan Szymanek explains that there are, in fact, two homophonous -nik suffixes, one of which stopped beingproductive in the sixties, the other being still productive in Yiddish-English. However, despite its current activity,the latest record of this affix in the OED was attested in 1975, which brings problems when providing an author-itative source for the present availability of the affix (cf. Bauer, English Word-Formation, 255–66).53Cf. Marchand, 293; Bauer, Morphological Productivity, 62–71; Bauer, “Productivity: Theories,” 329–30.

442 J. Fernández-Domínguez

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Jesú

s Fe

rnán

dez-

Dom

íngu

ez]

at 0

8:55

30

June

201

3

this theory. In effect, such a view follows naturally from the conception of WFTCs as100 per cent productive and the emphasis of this model on the semantics of word-for-mation, as the relevance of NUs lies not in which process generates them, but in thefact that the pertinent semantic label becomes materialised and speakers’ namingneeds are fulfilled.54

The qualitative traits of Štekauer’s proposal are present also in the fact that the con-ception of the naming process involves a view of word-formation as competitionamong processes. This derives from the belief that, when a naming need exists, anumber of word-formation processes compete for the generation of the unit butonly one of them succeeds, given that derivation happens only once per lexeme.This feature, often referred to as type-blocking,55 becomes manifest in Table 6, wherethe distribution of NUs reveals that a given NU appears under one and only one ono-masiological type.Given the characteristics of availability and profitability depicted above, Fernández-

Domínguez suggests an identification of availability and profitability with Ferdinand deSaussure’s two fundamental axes of language: the syntagmatic axis and the paradig-matic axis.56 Availability, first, belies a paradigmatic nature because it implies aneither/or choice between a series of word-formation processes; whenever a newconcept needs to be designated, one of the available processes is picked up and alexeme created. Hence, this axis provides a number of possible options, out ofwhich only one can be finally selected for the coinage. Profitability, by contrast, corre-sponds to the syntagmatic axis because, when a process is accessible from the avail-ability axis, it is able to create derivatives with a parallel morphosemantic structure(e.g. nouns expressing [AGENT], adjectives expressing [QUALITY], etc.); the syntagmaticaxis, then, has to do with the chain of similar units which have been produced usingone of the available processes. This system is illustrated in Figure 2 with a number ofword-formation processes for the creation of non-agentive nominals in Present-DayEnglish.The aim of the above proposal is to underline the different features of availability

and profitability while reinforcing their connection by enclosing them within thesame notional system. In this scheme, all existing processes are listed on the paradig-matic axis, but only those which are synchronically available display lexemes on thesyntagmatic axis. In opposition to these, processes which cannot be expanded atpresent (e.g. -ment or -th) are listed on the paradigmatic axis but cannot serve thenaming function of language, hence the Ø symbol.The above scheme is beneficial to the study of productivity in two basic senses. On

the one hand, it accurately reflects that profitability has to do with a sequence of unitsplaced on the syntagmatic axis, that is, units formed in an analogous way which are

54Štekauer, Onomasiological Theory, 82–5.55Aronoff, 30; Bauer, Morphological Productivity, 138; Plag, Word-Formation in English, 67–8.56Saussure, 221–37; Fernández-Domínguez, 63–5.

Morphological Productivity Measurement 443

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Jesú

s Fe

rnán

dez-

Dom

íngu

ez]

at 0

8:55

30

June

201

3

analysable applying the same morphosemantic principles. This axis emphasises theregular nature of productivity and is particularly pertinent to quantitative views of pro-ductivity (see 2.1). On the other hand, the few proposals which have addressed thenotion of availability (2.2 and 2.3) are reflected in Figure 2 in that its paradigmaticaxis shows the limited membership of the available processes, only one of which ispicked up upon naming.

4. Conclusions

The availability–profitability divide was established by Corbin in 1987 and has meant afundamental distinction for word-formation studies ever since, in that it introduceda crucial insight into morphological productivity and its two complementary sub-attributes. There is, on the one hand, a qualitative side of productivity, concernedwith whether it is possible to coin new lexemes through a given process or not; thiswe know as availability. Profitability, on the other hand, involves observing word-formation from a quantitative perspective, as some processes have the capacity tocoin more lexemes than others, that is some processes are more profitable than others.The above separation, originally developed with theoretical purposes, is also present

in the proposals for productivity measurement because, as illustrated in section 2, anyattempt at quantifying the output of word-formation necessarily has to opt for a quan-titative or a qualitative attitude to it. According to this background, this article hasreviewed eight approaches to productivity measurement and has confirmed that,even if all such models claim to assess productivity, their methodology evidences afocus on either availability or profitability. Specifically, most of the methods reviewedfocus on quantitative productivity, with only two proposals, that is, the onomasiologi-cal approach (in 2.2) and the hybrid approach (in 2.3) displaying qualitative traits—asituation which seems to stem from the theoretical stance of each model. Nevertheless,and despite particular viewpoints, it seems clear that most models pay attention to onlyone of the sides of productivity, thus presenting a biased/partial view of the phenom-enon and neglecting the intricate nature of word-formation.

Figure 2 Paradigmatic and Syntagmatic Axes of Productivity.

444 J. Fernández-Domínguez

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Jesú

s Fe

rnán

dez-

Dom

íngu

ez]

at 0

8:55

30

June

201

3

In view of the outcome of this study, it seems that this area of research requires anurgent clarification as regards morphological productivity and its two hyponyms, inparticular when it comes to their practical application. In this sense, the hybridapproach (in 2.3) is an attempt at a joint treatment of qualitative and quantitative pro-ductivity, as it first examines word-formation processes based on their availabilitystatus, and then ranks the available ones according to their degree of profitability,and in consistence with their synchronic condition. This means a step forward inthat this is at present the only model to add availability to traditional profitability-oriented counts, thus pioneering in a perception of productivity measurement as atwo-sided phenomenon, which will, hopefully, pave the way for future contributionson this issue.It may prove beneficial at this point to recall Plag’s assertion that productivity is in

fact an epiphenomenon, that is “a property that derives from other mechanisms”, andnot a indivisible force per se.57 This suggests that notions like availability and profitabil-ity come together for a unified conception of word-formation, and that it is theiraddition that endows productivity with its creative potential. Therefore, if the scholarlycommunity intends to be consistent with the theoretical view of productivity as amultifaceted phenomenon, a series of operations may be needed to measure it,rather than an all-embracing formula, as has been traditionally done. This study isintended to contribute to the clarification of this issue both by ascribing the existingmodels to a qualitative or quantitative trend, and by making a proposal that takesinto account both availability and profitability for its computations.

References

Aronoff, Mark. “Potential Words, Actual Words, Productivity and Frequency.” In Proceedings of the13th International Congress of Linguists, edited by Shiro Hattori and Kazuko Inoue. Tokyo:Tokyo Press, 1983.

———.Word Formation in Generative Grammar. Linguistic Inquiry Monographs Series. Cambridge,MA: MIT Press, 1976.

Baayen, R. Harald. “On Frequency, Transparency and Productivity.” In Yearbook of Morphology 1992,edited by Geert E. Booij and Jaap van Marle. Dordrecht: Kluwer, 1993.

———. “Probabilistic Approaches to Morphology.” In Probabilistic Linguistics, edited by Rens Bod,Jennifer Hay, and Stefanie Jannedy. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2003.

Baayen, R. Harald, and Rochelle Lieber. “Productivity and English Derivation: A Corpus-BasedStudy.” Linguistics 29 (1991): 801–44.

Bauer, Laurie. English Word-Formation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983.———. Introducing Linguistic Morphology. 2d ed. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2003.———. Morphological Productivity. Cambridge Studies in Linguistics. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press, 2001.———. “Productivity: Theories.” In Handbook of Word-Formation, edited by Pavol Štekauer and

Rochelle Lieber. Dordrecht: Springer, 2005.

57Plag, Morphological Productivity, 12.

Morphological Productivity Measurement 445

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Jesú

s Fe

rnán

dez-

Dom

íngu

ez]

at 0

8:55

30

June

201

3

Bauer, Laurie, and Rodney D. Huddleston. “Lexical Word-Formation.” In The Cambridge Grammarof the English Language, edited by Rodney D. Huddleston and Geoffrey K. Pullum. Cambridge:Cambridge University Press, 2002.

Berschin, Helmut. “Sprachsystem und Sprachnorm bei spanischen lexikalischen Einheiten derStruktur KKVKV.” Linguistische Berichte 12 (1971): 39–46.

Booij, Geert E. Dutch Morphology. A Study of Word Formation in Generative Grammar. Dordrecht:Foris, 1977.

The British National Corpus, version 2 (BNC World), http://www.natcorp.ox.ac.uk. Distributed byOxford University Computing Services on behalf of the BNC Consortium (accessed July 21,2011).

Chomsky, Noam. “Remarks on Nominalization.” In Readings in English Transformational Grammar,edited by Roderick A. Jacobs and Peter S. Rosenbaum. Waltham, MA: Ginn, 1970.

Corbin, Danielle. Morphologie derivationelle et structuration du lexique. Tübingen: Max Niemeyer,1987.

Cowie, Claire S. “Diachronic Word-Formation: A Corpus-Based Study of Derived Nominalizationsin the History of English.” PhD diss., University of Cambridge, 1999.

Dressler, Wolfgang U., andMaria Ladányi. “Productivity inWord Formation (WF): AMorphologicalApproach.” Acta Linguistica Hungarica 47 (2000): 103–44.

Fernández-Domínguez, Jesús. Productivity in English Word-Formation. An Approach to N+NCompounding. Bern: Peter Lang Verlag, 2009.

Fernández-Domínguez, Jesús, Ana Díaz-Negrillo, and Pavol Štekauer. “How is Low MorphologicalProductivity Measured?” Atlantis 29 (2007): 29–54.

Gaeta, Livio, and Davide Ricca. “Productivity in Italian Word-Formation: A Variable-CorpusApproach.” Linguistics 44 (2006): 57–89.

Hay, Jennifer. Causes and Consequences of Word Structure. New York: Routledge, 2003.———. “Lexical Frequency in Morphology: Is Everything Relative?” Linguistics 39 (2001): 1041–70.Hay, Jennifer, and R. Harald Baayen. “Phonotactics, Parsing and Productivity.” Revista di Linguistica

15 (2003): 99–130.Hockett, Charles F. “The Problem of Universals in Language.” In Universals of Language, edited by

Joseph H. Greenberg. 2d ed. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1966.Kastovsky, Dieter. “The Problem of Productivity in Word-Formation.” Linguistics 24 (1986):

585–600.Kilgarriff, Adam. “BNC Frequency List.” 1996. [cited 16 November 2010]. Available from http://

www.kilgarriff.co.uk/BNClists/all.num.gz.Leech, Geoffrey, Paul Rayson, and Andrew Wilson. “Rank Frequency Lists of Words within Word

Classes (Parts of Speech) in the Whole Corpus.” 2004. [cited 23 February 2011]. Availablefrom http://ucrel.lancs.ac.uk/bncfreq/flists.html.

Lüdeling, Anke, Stefan Evert, and Ulrich Heid. “On Measuring Morphological Productivity.” InKONVENS-2000 Sprachkommunikation, edited by Ernst G. Schukat-Talamazzini andWerner Zühlke. Berlin: VDE-Verlag, 2003.

Lyons, John. Introduction to Theoretical Linguistics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1968.Marchand, Hans. The Categories and Types of Present-Day English Word-Formation. 2d ed. München:

Carl Beck, 1969.McQueen, James M., and Anne Cutler. “Morphology in Word Recognition.” In The Handbook of

Morphology, edited by Andrew Spencer and Arnold M. Zwicky. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1998.Nishimoto, Eiji. “Measuring and Comparing the Productivity of Mandarin Chinese Suffixes.” Journal

of Computational Linguistics and Chinese Language Processing 8 (2003): 49–76.Oxford English Dictionary on CD-ROM, version 3.1. 2d ed. Edited by John A. Simpson. Oxford:

Oxford University Press, 2002.

446 J. Fernández-Domínguez

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Jesú

s Fe

rnán

dez-

Dom

íngu

ez]

at 0

8:55

30

June

201

3

Plag, Ingo.Morphological Productivity: Structural Constraints on English Derivation. Berlin: Mouton deGruyter, 1999.

———. Word-Formation in English. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003.Plag, Ingo, Christiane Dalton-Puffer, and R. Harald Baayen. “Morphological Productivity across

Speech and Writing.” English Language and Linguistics 3 (1999): 209–28.Saussure, Ferdinand de. Cours de linguistique generale. Paris: Payot, 1916.Schultink, Henk. “Produktiviteit als Morfologisch Fenomeen.” Forum der Letteren 2 (1961): 110–25.Spencer, Andrew. Morphological Theory: An Introduction to Word Structure in Generative Grammar.

Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1991.Sproat, Richard, and Chilin Shih. “Corpus-Based Methods in Chinese Morphology.” In Proceedings of

the 19th International Conference on Computational Linguistics (COLING 2002). Taipei, 2002.Štekauer, Pavol. “Fundamental Principles of an Onomasiological Theory of English Word-