Characterization and Distribution of Colonic Dendritic Cells in Crohn’s Disease

Computed Tomography and Magnetic Resonance Enterography Findings in Crohn’s Disease: What Does the...

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

2 -

download

0

Transcript of Computed Tomography and Magnetic Resonance Enterography Findings in Crohn’s Disease: What Does the...

Abdominal Imaging / Imagerie abdominale

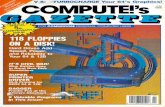

Computed Tomography and Magnetic Resonance EnterographyFindings in Crohn’s Disease: What Does the Clinician Need

to Know From the Radiologist?

Carolina Pesce Lamas Constantino, MDa,b,*, Rosana Souza Rodrigues, MD, PhDa,c,Jaime Araujo Oliveira Neto, MDc, Edson Marchiori, MD, PhDa,

Antonio Luis Eiras Araujo, MDa,c, Renata de Mello Perez, MD, PhDd,Daniella Braz Parente, MD, PhDa,c

aDepartment of Radiology, Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, BrazilbDepartment of Abdominal Imaging, Dimagem diagnostico por imagem, Rio de Janeiro, BrazilcDepartment of Radiology, D’Or Institute for Research and Education, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

dDepartment of Clinic and Hepatology, Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

AbstractThe purpose of this pictorial essay was to discuss and illustrate computed tomography and magnetic resonance enterography findings in

patients with Crohn’s disease. These noninvasive and easily performed methods for the evaluation of Crohn’s disease are useful fordifferentiating between active and fibrotic bowel disease, and can help to guide treatment (medical vs surgical). Although inflammatory andfibrostenotic findings of Crohn’s disease may overlap, computed tomography and magnetic resonance enterography can help to identify thepresence, extent, and severity of active inflammation that may respond to medical therapy, and the existence of fistulas and fibrostenosis thatmay benefit from surgical management.

R�esum�eCette pr�esentation vise �a explorer et illustrer les r�esultats de l’ent�erographie par tomodensitom�etrie et r�esonance magn�etique chez des

patients atteints de la maladie de Crohn. Ces modalit�es d’�evaluation de la maladie de Crohn, non effractives et facilement r�ealisables,permettent de diff�erencier le stade actif du stade fibreux de la maladie intestinale inflammatoire et peuvent aider �a orienter vers un traitementm�edical ou chirurgical. Les composantes inflammatoires et fibreuses de la maladie de Crohn ont parfois des apparences comparables. Dans cecontexte, l’ent�erographie par TDM ou r�esonance magn�etique est utile pour la d�etection des l�esions et l’�evaluation de l’�etendue et de la gravit�edurant la phase active, susceptible d’etre trait�ee m�edicalement, ainsi que pour la d�etection des fistules et des st�enoses fibreuses, dont letraitement sera de pr�ef�erence chirurgical.� 2014 Canadian Association of Radiologists. All rights reserved.

Key Words: Crohn’s; Enterography; Computed tomography; Magnetic resonance; Inflammation; Fibrostenosis

Computed tomography enterography (CTE) andmagnetic resonance enterography (MRE) are the mainimaging methods used to diagnose, stage, and monitorsmall bowel Crohn’s disease. These methods are used toevaluate transmural pathologic changes and extraluminal

complications [1e3]. Crohn’s disease has a wide spectrumof presentation and is often associated with active inflam-mation and fibrosis [4e6]. Imaging findings that indicateactive inflammation include mural thickening, submucosaloedema, contrast enhancement, prominent vasa recta,mesenteric oedema, and reactive lymphadenopathy. Otherfindings suggest fibrostenotic disease, such as wall thick-ening, with hypointense T1 and T2 signal intensity with noor slight inhomogeneous enhancement that becomes moreprominent in a delayed phase [1,3,7]. Fistulous tracts and

* Address for correspondence: Carolina Pesce Lamas Constantino, MD,

Rua Mario Covas Junior, 190, Apto 1301, Barra da Tijuca 22631-030, Rio de

Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

E-mail address: [email protected] (C. Pesce Lamas Constantino).

0846-5371/$ - see front matter � 2014 Canadian Association of Radiologists. All rights reserved.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.carj.2012.11.004

Canadian Association of Radiologists Journal 65 (2014) 42e51www.carjonline.org

abscess characterize the penetrating form of the disease[1,3,8].

This pictorial essay reviews the CTE and MRE findings ofpatients with Crohn’s disease by highlighting patterns that

aid in the characterization of active inflammation, fistulas,and fibrostenosis. The proper identification of these patternswill enable the clinician to select the most appropriatetreatment (clinical or surgical).

Figure 1. A 37-year-old man with fibrostenotic-predominant Crohn’s disease coexisting with active inflammation. Coronal (A) and axial (B) computed

tomography enterographic images, showing marked wall thickening associated with mural stratification (A, B, arrows). Note also the significant upstream

dilatation (A, arrowhead).

Figure 2. A 33-year-old man with Crohn’s disease. Axial T2 half-Fourier

acquisition single-shot turbo spin-echo (HASTE) images without (A) and

with (B) fat suppression, showing wall thickening with submucosal oedema

characterized by high signal intensity on the T2 image (A, arrow) that

persists on the T2 fat-suppressed image (B, arrow). Note also a small mural

ulceration (A, B, arrowhead).

Figure 3. A 55-year-old woman with mural fat deposition in long-standing

Crohn’s disease. Axial computed tomography enterographic section,

showing abnormally low attenuation of the bowel wall, a finding consistent

with fat deposition (arrows). Note the mucosal and serosal hyperenhance-

ment (arrowheads), which indicate a pattern of chronic disease with

activity.

43CT and MRE findings in Crohn’s disease / Canadian Association of Radiologists Journal 65 (2014) 42e51

Techniques

CTE and MRE are performed after the distention of thesmall bowel with a large volume of neutral contrast agent(1500-2000 mL) given orally 40-60 minutes before theexamination [1e3]. Polyethylene glycol electrolyte solution,3% mannitol, and 0.1% wt/vol low-concentration bariumwith sorbitol (Volumen; E-Z-EM, Westbury, NY) are avail-able as oral contrast agents. Patients undergoing CTE orMRE are requested to abstain from all food and drink for 4hours before scanning [9].

CTE

Neutral CTE oral contrast allows proper evaluation ofsmall bowel mural enhancement. Single-phase scanning is

performed from the diaphragm to the pubic symphysisduring the enteric phase, 45 seconds after the beginning ofintravenous contrast material injection (100-150 mL) ata rate of 3-4 mL/s. Images are acquired with a sectionthickness of 2.0-2.5 mm and a reconstruction intervalof 1.0-1.5 mm. Multiplanar reformatting helps thecharacterization of enteric and extraenteric abnormalities[3,9].

MRE

The most commonly used MRE enteric contrasts are thebiphasic agents, which have low signal intensity onT1-weighted images (T1WI) and high signal intensity onT2-weighted images (T2WI). The low signal intensity ofthese agents on T1WI improves the contrast between bowellumen and the inflamed hyperenhancing bowel wall afterintravenous contrast material administration. The use ofspasmolytics agents, such as hyoscine butylbromide andglucagon, are useful for reducing bowel peristalsis andmotion artifacts [1,10].

The MRE protocol includes a combination of axial andcoronal T2 half-Fourier acquisition single-shot turbo spin-echo (HASTE) (single-shot fast spin-echo [SSFSE]) with andwithout fat suppression, balanced steady-state free preces-sion (SSFP)(True fast imaging with steady-state precession[TrueFISP]) images, and pree and postecontrast-enhancedgradient-echo T1 3-dimensional sequences. T2 HASTE(SSFSE) sequences best demonstrate focal wall thickening,fold pattern changes, and ulceration but are susceptible tointraluminal motion and are often associated with intra-luminal low-signal-intensity artifacts. Balanced SSFP(TrueFISP) images best depict mesenteric adenopathy andprominent vasa recta in active Crohn’s disease (‘‘combsign’’) but are prone to susceptibility artifacts when air ispresent within the bowel lumen. Fat suppression may beadded for better detection of wall and mesenteric oedema aswell as for differentiation of focal submucosal fatty infiltra-tion from oedema. Postcontrast imaging is a very importantpart of the examination, performed 30, 70, and 90 secondsafter gadolinium intravenous injection (2 mL/s) and allowsthe assessment of bowel wall, nodal, and fistulas enhance-ment [1,10,11].

MRE and CTE have comparable accuracy in the evalu-ation of Crohn’s disease [1]. The lack of ionizing radiationis a major advantage of MRE over CTE, especially whenconsidering the young age of patients with Crohn’s disease,who will require multiple examinations during their life-times [7,11]. The superior tissue contrast of MRE may alsoallow differentiation among various pathologic changes inthe bowel wall that may show nonspecific low attenuationon CTE images. In addition, MRE uses a safer venouscontrast agent. However, CTE has higher temporal andspatial resolution, a shorter imaging time, less variability inexamination quality, and easy availability and lower cost[1,3,10,11].

Figure 4. A 65-year-old woman with mural fat deposition in long-standing

Crohn’s disease. Axial T2 half-Fourier acquisition single-shot turbo spin-

echo (HASTE) image (A), showing wall thickening of a small bowel

segment with high signal intensity within the submucosa that loses signal

intensity on an axial T2 fat-suppressed image (B), consistent with fat

deposition (arrows).

44 C. Pesce Lamas Constantino et al. / Canadian Association of Radiologists Journal 65 (2014) 42e51

Imaging Findings

Bowel-Wall Abnormalities

Bowel-wall thickeningBoth active inflammatory and fibrostenotic Crohn’s

disease usually present with bowel-wall thickening (>3mm), a finding with high sensitivity and specificity for thisdisease (83%-91% and 86%-100%, respectively) (Figure 1)[2,8,10,12,13] .

Submucosal oedemaSubmucosal oedema usually represents active inflamma-

tory Crohn’s disease and manifests as nonspecific lowattenuation on CTE images and high T2 signal intensity onMRE images. Oedema is more conspicuous on fat-suppressed images (Figure 2) [3,4,8,12].

Fat wall infiltration (fat halo sign)The presence of submucosal fat deposition in the bowel

wall is a sign of chronic Crohn’s disease. On CTE images,

such infiltration appears as very low attenuation (fat density)(Figure 3). On MRE, it is seen as high T2 signal intensity onnonefat-suppressed images that loses signal intensity on fat-suppressed images (Figure 4) [3,8,14].

FibrosisFibrotic wall thickening appears as nonspecific low

attenuation on CTE images and has low T1 and T2 signalintensity on MRE images. Both imaging methods show noenhancement or slight progressive enhancement thatbecomes more prominent in a very delayed phase (8 minutes)(Figure 5) [3,7,8,15]. Patients who present with this featurein addition to clinically significant stenosis are candidates forsurgical intervention [16].

Contrast enhancementMural enhancement is the most-sensitive indicator of

active Crohn’s disease [1e3]. Three different enhance-ment patterns have been described in Crohn’s disease:homogeneous, layered (stratified), and mucosal enhance-ment. The homogeneous pattern is characterized by

Figure 5. A 45-year-old woman with fibrostenotic-predominant Crohn’s disease and skip lesions. Axial T2 magnetic resonance (MR) image (A) and

axial fat-saturation T1 MR image obtained after contrast injection (B), showing a bowel-wall stricture with low T2 signal intensity (A, B, arrow),

transmural homogeneous enhancement (B, black arrowhead), and upstream dilatation (A, white arrowhead). Axial T2 MR image (C) and axial fat-

saturation T1 MR postcontrast image (D) of the same patient at another level, showing a bowel-wall stricture (C, D, large arrow) with submucosal

oedema (C, thin arrow), stratified enhancement (D, black arrowheads), and upstream dilatation (C, white arrowhead), which favor the diagnosis of active

disease.

45CT and MRE findings in Crohn’s disease / Canadian Association of Radiologists Journal 65 (2014) 42e51

diffuse enhancement of the entire wall thickness. Stratifiedenhancement shows mucosal, relatively poor submucosal,and serosal enhancement, which creates a target-like

appearance in cross-sectional imaging. In the mucosalpattern, enhancement of the innermost layer of the bowelwall is observed (Figure 6). In Crohn’s disease, allcontrast-enhancement patterns are associated with activeinflammation when compared with histopathologic find-ings and may be associated with fibrotic changes. Patientswith fibrotic changes in the bowel wall often have coex-istent active inflammation [4e7,13]. Although stratifiedenhancement has been reported to show a higher correla-tion with active inflammation than other enhancementpatterns [6,8], the clinical significance of each enhance-ment pattern has not been well established in the literature[13]. The absence of enhancement is useful for theexclusion of disease activity [15].

Skip Lesions

Patients with Crohn’s disease frequently have multipleinvolved small bowel segments separated by healthy bowel,which are referred to as skip lesions (Figure 7) [1,3,10,14].

Figure 6. Three enhancement patterns in Crohn’s disease. Axial fat-

saturation T1 magnetic resonance images obtained after contrast injection,

demonstrating (A) homogeneous enhancement of the entire wall thickness

(arrow), (B) layered (stratified) enhancement, characterized by mucosal

(arrowhead) and serosal (arrow) enhancement, and (C) mucosal enhance-

ment (arrow).

Figure 7. A 36-year-old woman with skip lesions in Crohn’s disease. Axial

computed tomography enterographic section, demonstrating 2 inflammatory

small bowel loops (arrows) separated by a normal segment, which is

a characteristic finding of Crohn’s disease.

Figure 8. A 28-year-old man with fibrostenotic-predominant Crohn’s disease

and coexisting active inflammation. Axial computed tomography entero-

graphic image, showing a very significant stricture with upstream dilatation

(arrowhead) and mucosal hyperenhancement (arrows).

46 C. Pesce Lamas Constantino et al. / Canadian Association of Radiologists Journal 65 (2014) 42e51

Bowel-Wall Stenosis and Bowel Obstruction

Bowel-wall stenosis in Crohn’s disease is invariablyassociated with a segment of thickened bowel wall, whereasadhesive strictures do not demonstrate this finding [10]and can be due to active inflammation (Figure 8). Thisdifferentiation is crucial to the choice of therapy. Diseaseactivity can be suggested by oedema, mucosal ulceration,and contrast enhancement. Although this distinction isvery important, it is not always clear on imaging studies[16]. When a prestenotic dilatation of >3 cm ispresent, the disease is probably chronic and clinicallysignificant [4e6].

Prominent Vasa Recta (Comb Sign)

Prominent vasa recta are caused by increased mesentericvascularity during active inflammation. The vessels penetratethe bowel wall perpendicular to the affected bowel lumenand are seen as parallel lines that enhance after contrastadministration (Figure 9) [1e3,10].

Mesenteric Oedema

Mesenteric oedema is seen as increased attenuation of themesenteric fat on CTE images and high T2 signal intensityon fat-suppressed MRE images, which corresponds to activedisease in the bowel wall (Figure 10) [3,7,10].

Ulcerations

Moderate and deep ulcerations appear as areas of muralirregularity on postcontrast CTE or MRE, and onT2-weighted images (Figure 11) [1,8,10,14]. The reportedsensitivity of MRE for the diagnosis of ulcers is 56%-90%[8,13].

Figure 9. A 21-year-old woman with Crohn’s disease. A coronal True fast imaging with steady-state precession (TrueFISP) image (A) and a coronal T1

postcontrast image (B), showing wall thickening of the distal ileum (A, white arrowhead) located a few centimetres from an ileocolic anastomosis (black

arrowheads), with homogeneous enhancement (B, white arrowhead). Note also the prominent vasa recta characterized by short low-signal-intensity parallel

lines on the T2 TrueFISP image (A), oriented perpendicular to the longitudinal axis (A, arrow), and high-signal-intensity parallel lines (B, arrow) due to

contrast enhancement of the vasculature (B).

Figure 10. A 55-year-old man with Crohn’s disease. Axial fat-saturated T2

magnetic resonance enterographic image, showing high signal intensity in

mesentery adjacent to the involved ileal segment (arrow). This finding is best

observed with fat suppression.

47CT and MRE findings in Crohn’s disease / Canadian Association of Radiologists Journal 65 (2014) 42e51

Sinuses and Fistulas

Sinuses (Figure 12) and fistulas indicate active diseaseand are seen as high-attenuation lines on CTE images and T2hyperintense lines that enhance after contrast administration,

which reflect their higher vascular flow and hyperemia [8].Complex internal fistulas usually have a stellate appearance,with multiple tracts and bowel loops that radiate from the

Figure 11. A 65-year-old woman with Crohn’s disease. A coronal T2 half-Fourier acquisition single-shot turbo spin-echo (HASTE) image (A) and a coronal

True fast imaging with steady-state precession (TrueFISP) image (B), showing wall thickening with deep ulceration (A, B, arrow) of the distal ileum. (C) Note

the wall ulceration (arrow), and also mucosal hyperenhancement (arrowhead) on a coronal T1 postcontrast image.

Figure 12. A 36-year-old woman with penetrating Crohn’s disease.

Coronal volume-rendered computed tomography enterographic section,

depicting a sinus tract (arrowhead) that originated from the terminal

ileum. Note other signs of active inflammation (wall thickening and

mucosal hyperenhancement) in the ileocecal valve and terminal ileum

(arrow).

Figure 13. A 42-year-old man with fibrostenotic-predominant Crohn’s

disease. A complex fistula with transmural inflammation and marked

upstream dilatation is evident. A coronal fat-suppressed T1 magnetic reso-

nance image obtained after intravenous contrast administration, showing

complex ileoileal (arrow) and ileocolonic (arrowhead) fistulas with diffuse

enhancement of the entire wall thickness (transmural inflammation), and

marked upstream dilatation.

48 C. Pesce Lamas Constantino et al. / Canadian Association of Radiologists Journal 65 (2014) 42e51

central portion that are associated with desmoplastic andfibrotic reactions in the surrounding mesentery. Fistulas inCrohn’s disease can be enteroenteric and enterocolonic(Figure 13), enterovesical (Figure 14), enterocutaneous(Figure 15), and perianal [1,4,10]. The reported sensitivity ofMRE and CTE for the detection of internal fistulas is 83%and the specificity is 100% [8].

Abscesses

Abscesses are seen as hyperintense on T2W MREimaging, with a corresponding hypodense appearance on CT,

with a capsule that enhances after contrast administration(Figure 16) [1,8,10]. These features are a sign of activedisease [4].

Pseudodiverticulum Formation

Pseudodiverticulum is the apparent dilatation of theantimesenteric border of the bowel wall. This conditionoccurs as a consequence of fibrosis of the diseased mesen-teric side and is usually associated with other signs ofchronic disease (Figure 17) [8,10].

Fibrofatty Proliferation

Fibrofatty proliferation occurs as increased mesenteric fatsurrounding chronically inflamed bowel loops and is a signof chronic disease (Figure 18) [1,2,8].

Reactive Lymphadenopathy

Reactive lymphadenopathy commonly occurs in associa-tion with active inflamed bowel loops [1,5,8].

Pitfalls

Fat wall infiltration, oedema, and fibrosisAbnormalities such as fatty wall infiltration, oedema, and

fibrosis appear as nonspecific low attenuation on CTE andare more readily characterized by MRE because of its highertissue contrast differentiation [3,7,10].

Figure 14. A 37-year-old man with an enterovesical fistula in Crohn’s disease. Sagittal (A) and coronal (B) computed tomography enterographic images,

depicting an ileovesical fistula (white arrows) with thickening and enhancement of the bladder dome (black arrowheads). A small amount of gas is visible

inside the bladder (A, white arrowhead). An ileoileal fistula with bowel-wall thickening and mural hyperenhancement is also visible (B, black arrow).

Figure 15. A 59-year-old man with Crohn’s disease. Axial computed

tomography enterographic image, depicting a complex enterocutaneous

fistula with a track from the rectum to the skin (arrows) and multiple foci of

cutaneous drainage (arrowheads). This patient also had ileocutaneous fistu-

lous tracks (not shown).

49CT and MRE findings in Crohn’s disease / Canadian Association of Radiologists Journal 65 (2014) 42e51

Inadequate bowel distentionInadequate bowel distention is an important problem that can

affect the assessment of wall thickness and enhancement.Nondistended loops can simulate or mask disease [3,10,11,14].

Conclusion

CTE and MRE are powerful tools in the management ofCrohn’s disease that can demonstrate small bowel mucosal

and mural inflammation as well as diagnose extraluminalcomplications. Mural thickening, submucosal oedema,wall enhancement, fat stranding, reactive lymphadenop-athy, and engorgement of the vasa recta characterize activedisease. Fibrostenotic disease is seen as nonspecific wallhypodensity on CTE and as mural hypointense signalingon T1- and T2-weighted images, with a lack of enhance-ment or progressive delayed enhancement. Findings thatindicate long-standing Crohn’s disease include submucosalfat deposition, pseudodiverticula, fibrofatty proliferation,and fibrotic strictures. CTE and MRE can also help toidentify the predominant disease type (active inflammatoryor fibrostenotic) and to guide and monitor treatment(medical vs surgical).

Figure 16. A 59-year-old man with known Crohn’s disease. Coronal (A) and axial (B) T2 magnetic resonance (MR) images and an axial gadolinium-enhanced

fat-saturated T1 MR image (C), showing a small fluid collection with a thick, irregular, and contrast-enhanced wall, within the lower abdomen, in the mesentery

adjacent to the cecum and terminal ileum, without communication with the bowel lumen (arrow). These findings are consistent with an abscess.

Figure 17. A 56-year-old man with multiple pseudodiverticula in Crohn’s

disease. Coronal computed tomography enterographic image, showing

pseudosacculations (arrowheads) produced by asymmetric thickening of the

terminal ileal mesenteric border. Also note the prominence of the vasa recta

(comb sign, arrows).

Figure 18. A 46-year-old woman with long-standing Crohn’s disease. Axial

computed tomography enterographic image, showing fibrofatty proliferation

encircling the involved bowel loops (arrows). Note also ileal segments that

display wall thickening and mural hyperenhancement, mainly in the mucosa

(arrowheads). A complex ileocolonic fistula was also noted in this patient

(not shown).

50 C. Pesce Lamas Constantino et al. / Canadian Association of Radiologists Journal 65 (2014) 42e51

References

[1] Fidler JL, Guimaraes L, Einstein DM. MR imaging of the small bowel.

Radiographics 2009;29:1811e25.

[2] Huprich JE, Fletcher JG. CT enterography: principles, technique and

utility in Crohn’s disease. Eur J Radiol 2009;69:393e7.

[3] Elsayes KM, Al-Hawary MM, Jagdish J, et al. CT enterography:

principles, trends, and interpretation of findings. Radiographics 2010;

30:1955e70.

[4] Zappa M, Stefanescu C, Cazals-Hatem D, et al. Which magnetic

resonance imaging findings accurately evaluate inflammation in small

bowel Crohn’s disease? A retrospective comparison with surgical

pathologic analysis. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2011;17:984e93.

[5] Chiorean MV, Sandrasegaran K, Saxena R, et al. Correlation of CT

enteroclysis with surgical pathology in Crohn’s disease. Am J Gas-

troenterol 2007;102:2541e50.[6] Punwani S, Rodriguez-Justo M, Bainbridge A, et al. Mural inflam-

mation in Crohn disease: location-matched histologic validation of MR

imaging features. Radiology 2009;252:712e20.

[7] Siddiki H, Fidler J. MR imaging of the small bowel in Crohn’s disease.

Eur J Radiol 2009;69:409e17.

[8] Sinha R, Verma R, Verma S, et al. MR enterography of Crohn disease:

part 2, imaging and pathologic findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2011;

197:80e5.

[9] Paulsen SR, Huprich JE, Fletcher JG, et al. CT enterography as

a diagnostic tool in evaluating small bowel disorders: review of clinical

experience with over 700 cases. Radiographics 2006;26:641e57;

discussion 57e62.[10] Tolan DJ, Greenhalgh R, Zealley IA, et al. MR enterographic

manifestations of small bowel Crohn disease. Radiographics 2010;30:

367e84.

[11] Sinha R, VermaR, Verma S, et al. MR enterography of Crohn disease: part

1, rationale, technique, and pitfalls.AJRAmJRoentgenol 2011;197:76e9.

[12] Steward MJ, Punwani S, Proctor I, et al. Non-perforating small bowel

Crohn’s disease assessed by MRI enterography: derivation and histo-

pathological validation of an MR-based activity index. Eur J Radiol

2012;81:2080e8.

[13] Ziech ML, Bipat S, Roelofs JJ, et al. Retrospective comparison of

magnetic resonance imaging features and histopathology in Crohn’s

disease patients. Eur J Radiol 2011;80:299e305.

[14] Lee-Elliott C, Ayer R. Small bowel MRI imaging in the DGH: are you

doing it yet? Clin Radiol 2012;67:605e12.

[15] Lawrance IC, Welman CJ, Shipman P, et al. Correlation of MRI-

determined small bowel Crohn’s disease categories with medical

response and surgical pathology.World JGastroenterol 2009;15:3367e75.

[16] VanAsscheG, Dignass A, Panes J, et al. The second European Evidence-

based Consensus on the Diagnosis andManagement of Crohn’s Disease:

definitions and diagnosis. J Crohns Colitis 2010;4:7e27.

51CT and MRE findings in Crohn’s disease / Canadian Association of Radiologists Journal 65 (2014) 42e51

Copyright of Canadian Association of Radiologists Journal is the property of Elsevier Scienceand its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv withoutthe copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, oremail articles for individual use.