International Progress in Marine Spatial Planning

Transcript of International Progress in Marine Spatial Planning

© 2013 Koninklijke Brill NV ISBN 978 90 04 25045 1

<UN>

LEIDEN • BOSTON2013

OCEANYEARBOOK 27

Edited byAldo Chircop, Scott Coffen-Smout, and Moira McConnell

Sponsored by theInternational Ocean Institute

Sponsored by the Marine & Environmental Law Institute

of the Schulich School of Law

© 2013 Koninklijke Brill NV ISBN 978 90 04 25045 1v

<UN>

Contents

Peter Serracino Inglott (1936–2012): In Memoriam ixJon Markham Van Dyke (1943–2011): In Memoriam xvThe International Ocean Institute xixMarine & Environmental Law Institute, Schulich School of Law xxvAcknowledgements xxvii

Issues and Prospects

Carbon Dioxide Storage in the Sub-seabed and Sustainable Development: Please Mind the Gap, Chiara Armeni 1

Addressing Ocean Acidification as Part of Sustainable Ocean Development, Sarah R. Cooley and Jeremy T. Mathis 29

UNCLOS at Thirty: Open Challenges, Tullio Treves 49

Rio+20

Rio+20 and the Oceans: Past, Present, and Future, Susan Lieberman and Joan Yang 67

Indigenous Knowledge in Marine and Coastal Policy and Management, Monica E. Mulrennan 89

Rio+20: Indigenous Knowledge and Intellectual Property in Coastal and Ocean Law, Chidi Oguamanam 121

Coastal and Marine Spatial Planning

Improving Sea-Land Management by Linking Maritime Spatial Planning and Integrated Coastal Zone Management: French and Belgian Experiences, Betty Queffelec and Frank Maes 147

International Progress in Marine Spatial Planning, Stephen Jay, Wesley Flannery, Joanna Vince, Wen-Hong Liu, Julia Guifang Xue, Magdalena Matczak, Jacek Zaucha, Holger Janssen, Jan van Tatenhove, Hilde Toonen, Andrea Morf, Erik Olsen, Juan Luis Suárez de Vivero, Juan Carlos Rodríguez Mateos, Helena Calado, John Duff and Hanna Dean 171

© 2013 Koninklijke Brill NV ISBN 978 90 04 25045 1

<UN>

vi Contents

Protecting Marine Spaces: Global Targets and Changing Approaches, Mark D. Spalding, Imèn Meliane, Amy Milam, Claire Fitzgerald and Lynne Z. Hale 213

Living Resources and Aquaculture

Fisheries Management and Governance: Forces of Change and Inertia, Anthony Charles 249

Fishing for Self-determination: European Fisheries and Western Sahara – The Case of Ocean Resources in Africa’s Last Colony, Jeffrey Smith 267

Sustainability in Aquaculture: Present Problems and Sustainable Solutions, Michelle Allsopp, David Santillo and Cat Dorey 291

Maritime Transport and Security

Migrant Smuggling by Sea: Tackling Practical Problems by Applying a High-level Inter-agency Approach, Jasmine Coppens 323

Recent Developments and Continuing Challenges in the Regulation of Greenhouse Gas Emissions from International Shipping, James Harrison 359

Implementation of the 2004 Ballast Water Management Convention in the West African Region: Challenges and Prospects, Sabitiyu Abosede Lawal 385

Law of the Sea and Maritime Boundaries

Recalling the Falkland Islands (Malvinas) Sovereignty Formula, Vasco Becker-Weinberg 411

Navigating between Consolidation and Innovation: Bangladesh/Myanmar (International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea, Judgment of 14 March 2012), Erik Franckx and Marco Benatar 435

Polar Oceans Governance

The European Union and the North: Towards the Development of an EU Arctic Policy?, Mar Campins Eritja 459

Arctic Council Observer: The Development and Significance of Poland’s Approach towards the Arctic Region, Michał Łuszczuk 487

© 2013 Koninklijke Brill NV ISBN 978 90 04 25045 1

<UN>

Contents vii

Sustainable Ocean Development in the Arctic: Making a Case for Marine Spatial Planning in Offshore Oil and Gas Exploration, Jens-Uwe Schröder-Hinrichs, Henrik Nilsson and Jonas Pålsson 503

Book Reviews

Darren S. Calley, Market Denial and International Fisheries Regulation: The Targeted and Effective Use of Trade Measures Against the Flag of Convenience Fishing Industry (Gordon Munro) 531

David Grinlinton and Prue Taylor, eds., Property Rights and Sustainability: The Evolution of Property Rights to Meet Ecological Challenges (Diane Rowe) 533

Warwick Gullett, Clive Schofield and Joanna Vince, eds., Marine Resources Management (Richard Kenchington) 536

Igor V. Karaman, Dispute Resolution in the Law of the Sea (Philippe Gautier) 537

James Kraska, Contemporary Maritime Piracy: International Law, Strategy, and Diplomacy at Sea (Charles H. Norchi) 539

Myron Nordquist, Satya N. Nandan and James Kraska, eds., United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea 1982: A Commentary, Volume VII (Caitlyn L. Antrim) 543

Clive R. Symmons, ed., Selected Contemporary Issues in the Law of the Sea (Alexander Proelss) 545

Helmut Tuerk, Reflections on the Contemporary Law of the Sea (Tullio Scovazzi) 551

Bibi van Ginkel and Frans-Paul van der Putten, eds., The International Response to Somali Piracy: Challenges and Opportunities (Hugh R. Williamson) 556

Jorge A. Vargas, Mexico and the Law of the Sea: Contributions and Compromises (Alejandro Yáñez-Arancibia) 560

Davor Vidas and Peter Johan Schei, eds., The World Ocean in Globalisation: Climate Change, Sustainable Fisheries, Biodiversity, Shipping, Regional Issues (Frank Müller-Karger) 565

Appendices

A. Annual Report of the International Ocean Institute 569 1. Report of the International Ocean Institute, 2011 569B. Selected Documents and Proceedings 591 1. Oceans and the Law of the Sea Report of the

Secretary-General, 2012 591

© 2013 Koninklijke Brill NV ISBN 978 90 04 25045 1

<UN>

viii Contents

2. United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea Report of the Twenty-Second Meeting of States Parties, 4–11 June 2012 621

3. Report on the Work of the United Nations Open-ended Informal Consultative Process on Oceans and the Law of the Sea at Its Thirteenth Meeting, 29 May–1 June 2012 643

4. The Future We Want, Draft Resolution Submitted by the President of the General Assembly 659

5. The Oceans Compact: Healthy Oceans for Prosperity 717 6. Commonwealth Maritime Boundaries and Ocean Governance

Forum: Benefiting from the Ocean Economy, Proceedings of the First Commonwealth Maritime Boundaries and Ocean Governance Forum, 17–19 April 2012 725

Contributors 757

Index 771

© 2013 Koninklijke Brill NV ISBN 978 90 04 25045 1Ocean Yearbook 27: 171–212

171

<UN>

† This article has been edited by the first two authors, who also wrote the introductory sections, the discussion, conclusions and the sections on the UK and Canada. The other authors wrote the other national sections, as indicated by their affiliation; they contributed equally, and are listed simply in order of the nations as they appear in the article. Thanks to Jan Schmidtbauer Crona from the Swedish Authority for Marine and Water Management and Sten Jerdenius from the Ministry of the Environment for their helpful comments on the section on Sweden.

1. Agenda 21, adopted at UNCED Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 3 to 14 June 1992, available online: <http://www.un.org/esa/sustdev/documents/agenda21/english/Agenda21.pdf>.

Coastal and Marine Spatial Planning

International Progress in Marine Spatial PlanningStephen Jay,a Wesley Flannery,b Joanna Vince,c Wen-Hong Liu,d Julia Guifang Xue,e Magdalena Matczak,f Jacek Zaucha,f Holger Janssen,g Jan van Tatenhove,h Hilde Toonen,h Andrea Morf,i Erik Olsen,j Juan Luis Suárez de Vivero,k Juan Carlos Rodríguez Mateos,k Helena Calado,l John Duffm and Hanna Deanm†

aUniversity of Liverpool, UK; bNational University of Ireland Galway, Ireland; cUniversity of Tasmania, Australia; dNational Kaohsiung University, Taiwan; eOcean University of China, Qingdao, China; fMaritime Institute, Gdańsk, Poland; gLeibniz Institute for Baltic Sea Research, Germany; hWageningen University, The Netherlands; iSwedish Institute for the Marine Environment, Sweden; jInstitute of Marine Research, Norway; kUniversity of Seville, Spain; lUniversity of the Azores, Portugal; mUniversity of Massachusetts, USA

INTRODUCTION

In June 2012, the United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development, com-monly referred to as Rio+20, took place in Rio de Janeiro. Rio+20 marked the 20th anniversary of the first Earth Summit, the 1992 United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) in Rio de Janeiro, and the 10th anniver-sary of the second Earth Summit, the 2002 World Summit on Sustainable Development (WSSD) in Johannesburg. Integrated marine governance was a key issue at all three summits. At UNCED, the states adopted Agenda 21, which emphasized the adoption of a holistic, systems approach to marine governance.1 At WSSD, states adopted the Johannesburg Plan of Implementation (JPoI) which re-emphasized the need to adopt an integrated, ecosystem approach to marine gov-ernance. The JPoI also promoted the adoption of integrated, multidisciplinary, and

© 2013 Koninklijke Brill NV ISBN 978 90 04 25045 1

172 Coastal and Marine Spatial Planning

<UN>

2. Johannesburg Plan of Implementation, available online: <http://www.un.org/esa/sustdev/documents/WSSD_POI_PD/English/POIToc.htm>.

3. Id.4. L. Veitch, N.K. Dulvy, H. Koldewey, S. Lieberman, D. Pauly, C.M. Roberts, A.D. Rogers

and J.E.M. Baillie, “Avoiding empty ocean commitments at Rio+20,” Science 336 (2012): 1383–1385.

5. Id.6. Report on the work of the United Nations Open-ended Informal Consultative

Process on Oceans and the Law of the Sea at its twelfth meeting, A/66/186, available online: <http://daccess-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N11/431/39/PDF/N1143139.pdf? OpenElement>.

7. Id.8. Rio+20: The Future We Want, available online: <http://www.uncsd2012.org>.9. Global Partnership and Capacity Building for Ecosystem-Based Management of

Oceans and Coasts – Pursuing Compatible Objectives for Sustainable Development through Integrated Spatial Planning, Management and Policies, available online: <http://www .uncsd2012.org/index.php?page=view&type=1006&menu=153&nr=501>.

multisectoral coastal and ocean management at the national level.2 In contrast to Agenda 21, the JPoI set target dates for the implementation of its commitments. For example, states agreed to establish national networks of Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) by 2012.3 However, a recent review of the implementation of commitments at the Earth Summits concluded that many of them will not be met by their target dates.4 For example, although there has been an increase in the number of MPAs implemented, the 2012 target will not be met at the current rate of designation.5

Prior to the Rio+20 conference, a number of delegations stated that for it to be successful it must set realistic targets and goals of ocean management.6 They argued that states should take bold actions at Rio+20, reaffirming existing commitments, but also developing new initiatives.7 Unfortunately, the major output of Rio+20, The Future We Want,8 mainly reasserts commitments made at the previous summits and does little to build upon innovative approaches in marine management, such as marine spatial planning (MSP), which have come to the fore in the last decade. A number of states have, however, entered into a voluntary agreement to advance sustainable ocean development through integrated spatial planning, management and policies; this represents a clear recognition of MSP as a means of achieving the wider goals set out earlier.9

Moreover, a number of maritime nations have already begun to implement spa-tial planning initiatives in their marine environments. In this article, we present a picture of the state-of-play of MSP development globally, illustrating how rapidly progress has been made in the adoption of this significant new approach to manag-ing waters under national jurisdiction, especially since Johannesburg. This is not to say that MSP systems are being comprehensively adopted in many nations; the pic-ture remains one of partial uptake, with uncertainties remaining about the extent to which MSP will be implemented in some contexts. But given how recently the con-cept of MSP has emerged, the current level of progress represents a promising start and a proactive application of the ocean management principles emerging since the Rio Summit.

© 2013 Koninklijke Brill NV ISBN 978 90 04 25045 1

International Progress in Marine Spatial Planning 173

<UN>

10. F. Douvere, “The importance of marine spatial planning in advancing ecosystem-based sea use management,” Marine Policy 32 (2008): 762–771.

11. N. Schaefer and V. Barale, “Maritime spatial planning: Opportunities and challenges in the framework of the EU integrated maritime policy,” Journal of Coastal Conservation 15 (2011): 237–245.

12. S. Jay, “Built at sea: Marine management and the construction of marine spatial planning,” Town Planning Review 81 (2010): 173–191.

13. J. Day, “Zoning: Lessons from the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park,” Ocean and Coastal Management 45 (2002): 139–156.

14. W. Flannery and M. Ó Cinnéide, “Stakeholder participation in marine spatial plan-ning: Lessons from the Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary,” Society and Natural Resources 25 (2012): 727–742.

15. P. Gilliland and D. Laffoley, “Key elements and steps in the process of developing ecosystem-based marine spatial planning,” Marine Policy 32 (2008): 787–796.

This article provides an overview of how MSP is being developed in a number of geographical and institutional contexts. This is not intended to be a thorough empirical analysis of the progress of MSP. Rather, the article aims to provide an indi-cation of how MSP is developing in a number of leading maritime nations, the legis-lative and institutional arrangements these nations are adopting, the provisional outcomes of these processes and likely future challenges. The article begins by reviewing the origins of MSP and how it relates to other marine management pro-cesses. This is followed by a review of 13 national MSP initiatives, leading to conclu-sions about some of the factors currently at work in the uptake of MSP.

THE RISE OF MARINE SPATIAL PLANNING

MSP is coming to prominence as a new approach for contributing to the governance and management of the seas and oceans.10 Drawing on long-standing practices of terrestrial, or land-use, planning, MSP seeks to bring a more spatially-specific dimen-sion to the regulation of marine activities, by setting out, for example, preferred geo-graphical patterns of sea uses within a given area. This should be done with the optimum configuration of interests in mind, so that conflicts between maritime activities are avoided, the most efficient use is made of marine resources, and valu-able marine ecosystems are not threatened.11 MSP is intended to bring about much more coherent and integrated patterns of sea use than has resulted from the typi-cally ad-hoc and sectoral approach to regulating marine activities that has domi-nated marine management until now.12

MSP has its roots in marine nature conservation, as an extension of the logic of establishing MPAs. Indeed, Australia’s system of zoning for the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park is often cited as the pioneering example of MSP, dating from the 1980s (see also Sweden’s leading role, below).13 Subsequent initiatives in the USA and Canada have also been strongly led by environmental concerns,14 and a key theme of MSP thinking is that it should adopt an ecosystem approach,15 by which human

© 2013 Koninklijke Brill NV ISBN 978 90 04 25045 1

174 Coastal and Marine Spatial Planning

<UN>

16. S. Kidd, A. Plater and C. Frid, eds., The Ecosystem Approach to Marine Planning and Management (London: Earthscan, 2011).

17. H. Smith, F. Maes, T. Stojanovic and R. Ballinger, “The integration of land and marine spatial planning,” Journal of Coastal Conservation 15 (2011): 291–303.

18. W. Flannery and M. Ó Cinnéide, “Marine spatial planning from the perspective of a small seaside community in Ireland,” Marine Policy 32 (2008): 980–987; Natura 2000, an EU conservation policy which consists of the EC Birds Directive and the Habitats Directive which require Member States to designate Special Protection Areas for rare, vulnerable or regularly occurring migratory species, and to designate Special Areas of Conservation to pro-tect certain natural habitats or species of plants or animals.

19. G.W. Allison, J. Lubchenco and M.H. Carr, “Marine reserves are necessary but not sufficient for marine conservation,” Ecological Applications 8 (1998): S79–S92.

20. Directive 2008/56/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 June 2008 establishing a framework for Community action in the field of marine environmental policy (Marine Strategy Framework Directive), OJ L 164, (2008): 19–40.

21. Douvere, n. 10 above; E.M. De Santo, “Whose science? Precaution and power-play in European marine environmental decision-making,” Marine Policy 34 (2010): 414–420.

22. OSPAR is the Commission for the Protection of the Marine Environment of the Northeast Atlantic; HELCOM is the Baltic Marine Environment Protection Commission.

23. European Commission, Study on the Economic Effects of Maritime Spatial Planning (Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2011).

intervention is sensitive to ecological constraints.16 The need to protect marine bio-logical diversity and to establish national networks of MPAs by 2012 were two of the major drivers of MSP.17 In the European Union (EU), for example, MSP is viewed as an effective means of implementing Natura 2000 in the marine environment.18 However, it is now recognized that MPAs on their own are insufficient for marine conservation and that they must be implemented within a broader place-based management system.19 Furthermore, the EU has recently developed new marine protection legislation in the form of its Marine Strategy Framework Directive (MSFD) that encourages the adoption of MSP.20 The aim of the MSFD is to promote sustainable use of the sea, conserve marine ecosystems, and achieve ‘good environ-mental status’ of the European marine environment by 2020, drawing on the princi-ple of ecosystem-based MSP.21 It is envisaged that implementation of the Directive will address all activities impacting the marine environment and lead to the estab-lishment of protected areas. MSP is likely to have an important role in achieving these objectives, especially as it will assist in dealing with the diversity of conditions and issues across marine regions and sub-regions, as recognised in the MSFD. A high degree of coordination between states will also be required, in view of the trans-boundary and interconnected nature of the marine environment, with an important role for regional sea conventions, such as OSPAR and HELCOM.22

Moreover, the more recent uptake of MSP, especially in Europe, has been char-acterized by a broader range of objectives, including maximizing the economic opportunities presented by the sea,23 via a better organization of maritime activi-ties. This includes traditional uses, such as fishing and navigation, and newer uses, such as renewable energy and mariculture. This is reflected in the EU’s Integrated

© 2013 Koninklijke Brill NV ISBN 978 90 04 25045 1

International Progress in Marine Spatial Planning 175

<UN>

24. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: An Integrated Maritime Policy for the European Union, Brussels 10.10.2007, COM(2007)575 final.

25. C. Ehler and F. Douvere, Visions for a Sea Change, Report of the First International Workshop on Marine Spatial Planning, Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission and Man and the Biosphere Programme, UNESCO, Paris, 2007, available online: <http://ioc3 .unesco.org/icam/images/stories/SEA%20CHANGE%20VISION%20.pdf>.

26. P. Drankier, “Embedding maritime spatial planning in national legal frameworks,” Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 14 (2012): 7–27.

27. HELCOM & OSPAR, Towards an Ecosystem Approach to the Management of Human Activities, statement of the first joint ministerial meeting of the Helsinki and OSPAR Commissions, Bremen 25–26 June, 2003, available online: <http://www.ospar.org/ documents/02-03/JMMC03/SR-E/JMM%20ANNEX05_Ecosystem%20Approach%20Statement.doc>; H. Backer, “Transboundary maritime spatial planning: A Baltic Sea perspec-tive,” Journal of Coastal Conservation 15 (2011): 279–289.

28. Commission of the European Communities (CEC), Roadmap for Maritime Spatial Planning: Achieving Common Principles in the EU, COM 791 (Brussels: CEC, 2008), available online: <http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:2008:0791:FIN:EN :PDF>.

29. Smith et al., n. 17 above.

Maritime Policy (IMP) that is designed as a framework for coordinating European marine management,24 with the economic potential of the seas in view. The IMP regards MSP as a fundamental tool for the sustainable development of marine areas and coastal regions in the EU, a means of supporting integrated policy-making across marine sectors. A similar approach, which views MSP as a means of support-ing the maritime economy, is developing in China and Taiwan. These varied geo-graphical contexts will be explored further below. Other examples of MSP-type initiatives around the world have also been documented.25

The spread of MSP is due, in part, to its being actively promoted by inter- governmental bodies, non-governmental organizations, stakeholder organizations, and marine scientists and managers. Coastal nations are being encouraged to adopt systems of MSP for the waters under their jurisdiction, and legislation is being devel-oped in various ways to enable this.26 Different administrative patterns are also emerging; for example, internal and territorial waters are being planned at a sub-national level in some contexts, while exclusive economic zones (EEZ) tend to come under the purview of national governments. Some regional sea organizations are also advocating a collaborative approach to MSP between their members,27 while the EU is taking significant steps to encourage the uptake of MSP by relevant mem-ber states and ensure cooperation between them,28 especially in relation to cross-border sea areas. Emphasis is also being placed on the need to link MSP with integrated coastal zone management (ICZM) initiatives and existing terrestrial planning arrangements.29 In addition to these wider management strategies, it is also clear that MSP uptake is being driven by specific spatial needs, such as to permit

© 2013 Koninklijke Brill NV ISBN 978 90 04 25045 1

176 Coastal and Marine Spatial Planning

<UN>

30. F. Douvere and F. Maes, “The contribution of marine spatial planning to imple-menting integrated coastal zone management,” in Coastal Zone Management, D. Green, ed., (London: Thomas Telford, 2009), pp. 13–30.

31. Id.32. Id.33. A. Schultz-Zehden, K. Gee and K. Scibior, Handbook on Integrated Maritime Spatial

Planning, available online: <http://www.plancoast.eu/files/handbook_web.pdf>; Smith et al., n. 17 above.

34. Douvere and Maes, n. 30 above.35. Id.36. Maritime Spatial Planning in the EU: Achievements and Future Development,

available online: <http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:2010:0771 :FIN:EN:PDF>.

37. C. Ehler and F. Douvere, Marine Spatial Planning: A Step-by-Step Approach Toward Ecosystem-based Management, (Paris: Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission and

the development of offshore wind energy schemes and to protect highly valued hab-itats from harm.

During the policy development of MSP, there has been discussion of its relation to ICZM. Both processes aim to address problems arising from sectoral and frag-mented governance in the marine environment.30 Both concepts have common planning principles, such as stakeholder participation and the adoption of a holistic approach. However, while ICZM traditionally focuses on achieving integration across management agencies and marine sectors, MSP focuses on effi-cient allocation of marine space to different marine activities, including nature con-servation.31 The allocation of coastal space is rarely, if ever, a feature of ICZM processes.32

Given that these processes share similar aims and principles, it has been argued that one could be used to implement the other. For example, ICZM has been advanced by a number of programs and influential documents as a means of facilitating MSP.33 On the other hand, MSP could lead to better implementation of ICZM principles by representing them spatially and temporally for a given planning area.34 Some argue that by emphasizing the spatial and temporal aspects of marine management, MSP has greater potential than ICZM to success-fully address common problems, such as fragmented governance.35 As such, ICZM is likely to become a sub-component of MSP in many coastal states, particularly in the EU where the adoption of ICZM has been promoted as a key principle of MSP.36

Generic principles and practical guidelines for MSP have been put forward,37 but it is clear that a wide variety of practical approaches is developing, reflecting different political contexts and objectives and traditions of planning. These varia-tions are partly reflected in the range of terminology that is being used, as illustrated in the national descriptions below; however, marine spatial planning remains the most widely recognized term.

© 2013 Koninklijke Brill NV ISBN 978 90 04 25045 1

International Progress in Marine Spatial Planning 177

<UN>

REVIEW OF NATIONAL MSP INITIATIVES

Thirteen nations that are currently active in developing MSP have been chosen for this review. This is not a comprehensive list; some other nations are also active in the field, or are carrying out related processes of marine conservation and management. However, these 13 represent the key regions in the world where MSP is becoming clearly established, and include the nations that are most prominent in its develop-ment at present.

The nations selected here vary considerably in the extent to which they are car-rying out MSP and their manner of doing so. In these accounts, the focus is upon a number of key issues that illustrate the differences in approach and potential out-comes. Some of the key lessons are also drawn out, as are challenges to be faced in ensuring that MSP contributes fully to the future well-being of the world’s seas and oceans. In particular, the following issues are considered:

• Legislative and administrative developments;• Implementation of MSP;• Outcomes for maritime activities and the marine environment, and an

assessment of progress since the Rio and Johannesburg Summits; and• Challenges faced and likely future directions.

The sections below have been contributed by national experts, as indicated in the list of authors to the article. Contributors were at liberty to adopt their own approach in describing MSP in their national contexts, though comparisons have been made possible by means of the common format outlined above. The journey begins in Australia and follows (approximately) the sun.

NATIONAL PROFILES

Australia

Legislative and Administrative Developments

Australia’s Constitution divides the responsibility for its oceans between the Commonwealth, states and territories. A state’s jurisdiction extends from the low watermark to 3 nautical miles (NM), and the Commonwealth’s from three to 200 NM. The 1979 Offshore Constitutional Settlement reinforced these boundaries.38

Man and the Biosphere Programme, UNESCO, 2009), available online: <http://www.unesco -ioc-marinesp.be/uploads/documentenbank/d87c0c421da4593fd93bbee1898e1d51.pdf>.

38. Department of the Attorney General, The Offshore Constitutional Settlement: A Milestone in Cooperative Federalism (Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service, 1980).

© 2013 Koninklijke Brill NV ISBN 978 90 04 25045 1

178 Coastal and Marine Spatial Planning

<UN>

39. Commonwealth of Australia, Australia’s Oceans Policy: Caring, Understanding and Using Wisely (Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service, 1998).

40. EPBC Act, Act No. 91 of 1999, ComLaw Authoritative Act C2012C00685.41. J. Vince, “The South East Regional Marine Plan: Implementing Australia’s Oceans

Policy,” Marine Policy 30 (2006): 420–430.42. TFG International, Review of the Implementation of Oceans Policy (Hobart: TFG

International, 2006).43. South-east Marine Region, available online: <http://www.environment.gov.au/

coasts/mbp/south-east/index.html>.44. See map online: <http://www.environment.gov.au/coasts/mbp/reserves/pubs/

map-national.pdf>.45. R. Kenchington and J. Day, “Zoning, a fundamental cornerstone of effective marine

spatial planning: Lessons learnt from the Great Barrier Reef, Australia,” Journal of Coastal Conservation 15 (2011): 271–278.

Australia’s Oceans Policy 1998 provided the framework for MSP for Common-wealth waters, with an overarching goal to achieve full integration across sectors and jurisdictions.39 It called for the establishment of Regional Marine Plans (RMPs) based on large ecosystems rather than constitutional borders. In 2005, RMPs were changed to Marine Bioregional Plans (MBPs) and given statutory recognition through the Commonwealth’s Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation (EPBC) Act (1999).40 Several institutions were created to implement the Oceans Policy. Today, only the Oceans Policy Science Advisory Group remains, while the Commonwealth Department of Sustainability etc., manages MBPs.

Implementation

The implementation of the Oceans Policy became problematic when it failed to receive formal state and territorial support. The first and only RMP to be completed covered the South-east region of Australia;41 however, Australia’s largest network of temperate marine reserves was established in this region.

A 2002 review of the Oceans Policy saw the holistic approach to MSP replaced with a narrow, environmentally focused one.42 The EPBC Act provides for the estab-lishment of MBPs with a focus on conservation issues and regional priorities.

Outcomes and Assessment of Progress

Draft MBPs have been released for three regions. The fourth South East RMP has not yet been converted to an MBP.43 In 2012, the Commonwealth government proposed the final Marine Reserves Network including zoning measures for marine activities based on IUCN categories.44 Once proclaimed, the Coral Sea will be the largest Marine Reserve in the network. The Great Barrier Reef Marine Park (GBRMP) is part of the network, but has been excluded from the MBP process as it has unique juris-dictional arrangements and is managed by the GBRMP Authority. The Park was rezoned in 2004 to effectively manage conservation and sustainable resource use.45

© 2013 Koninklijke Brill NV ISBN 978 90 04 25045 1

International Progress in Marine Spatial Planning 179

<UN>

46. J.T. Hatton, S. Cork, P. Harper, R. Joy, P. Kanowski, R. Mackay, N. McKenzie and T. Ward, State of the Environment 2011, Department of Sustainability, Water, Population and Communities (Department of Sustainability, Water, Population and Communities: Canberra, 2011).

47. A. McMeekin, “Australia’s ocean to be protected under a Gillard Government plan to add 44 large-scale marine reserves,” The Daily Telegraph (June 14, 2012).

48. L.K. Chien, W.Y. Chiu and H.C. Li, Sea Area Functional Zoning and Management Works (Taipei: Construction and Planning Agency, 2008); C.C. Chu, Ocean Zoning and Planning (Beijing: Ocean Press, 2008).

The results have been positive and have become the benchmark for MSP in Australia and elsewhere.

Australia has attempted to honor commitments made in Rio de Janeiro and Johannesburg by developing an Oceans Policy applying an ecosystem-based approach to MSP. However, full integration has not been achieved and the Oceans Policy no longer appears to be a government priority. Nevertheless, the EPBC Act provides the legislative framework for oceans sustainability and the development of networks of MPAs.

Challenges and Future Directions

Because the EPBC Act is focused on environmental matters, it cannot generate a holistic approach to MSP. A recent State of the Environment Report suggests that there is “continued loss of biodiversity, duplication of effort, inefficiencies, an over-all lack of effectiveness, and distrust… A vertically and horizontally integrated national system for marine conservation and management is widely seen as a criti-cal gap in management.”46 It is hoped that Rio+20 will provide the incentive for Australia to recommit to a national approach, supported by adequately resourced institutional arrangements for MSP. For example, in the lead-up to Rio+20 the Australian government announced the plans to add 44 large-scale marine reserves to its national network.47

Taiwan

Legislative and Administrative Developments

Although Taiwan is a maritime nation, neither the coastal zone nor sea areas have yet been properly planned. A draft Coastal Act, developed in 1991, was sent to the Legislative Yuan in 1997, 2000, 2002, and 2008, but has been rejected each time. To deal with competition for sea uses, the Construction and Planning Agency of the Ministry of the Interior included sea areas and coastal regions in the 2009 review of regional planning.48 Recently, the government has also included marine resources in the draft of the National Land Planning Act. Following the reform of the Executive

© 2013 Koninklijke Brill NV ISBN 978 90 04 25045 1

180 Coastal and Marine Spatial Planning

<UN>

49. Id.50. W.H. Liu, C.C. Wu, H.T. Jhan and C.H. Ho, “The role of local government in marine

spatial planning and management in Taiwan,” Marine Policy 35 (2011): 105–115.51. S.J. Boyes, M. Elliott, S.M. Thomson, S. Atkins and P. Gilliland, “A proposed multiple-

use zoning scheme for the Irish Sea: An interpretation of current legislation with GIS-based zoning approaches and effectiveness for the protection of nature conservation interests,” Marine Policy 31 (2007): 287–298.

52. W.Y. Chiau, “Marine territory planning: Vision, scope, and key issues,” City and Planning 34 (2007): 241–272.

Yuan in 2012, an Ocean Affairs Council will be established for the integration, coor-dination, and promotion of marine affairs. In this context, MSP and management will be an excellent tool for integrating, planning and coordinating marine manage-ment for the council.

Implementation

The proposed marine zoning schemes in Taiwan fall into two types. The first is spe-cific use schemes; researchers consistently adopt the Chinese ocean functional zon-ing approach.49 The second type is a simple zoning scheme. Liu et al.50 employed the method proposed by Boyes et al.,51 in which the sea is divided into four use types: general use, conservation priority, exclusive, and protected.

Outcomes and Assessment of Progress

According to the present system, there are only conservation priority areas and pro-tected zones in Taiwan, and these zones are quite small. Even though coral reef and wetland habitats abound, few are included in MPAs. It is important to add these valuable habitats into conservation priority areas or protected zones. Consequently, Taiwan is still far from reaching the 2010 goal of designating MPAs that account for 10 percent of the territorial surface area. The most serious conflicts relate to exclu-sive fishing rights that originated in the Japanese colonial era as a measure of pro-tecting conventional coastal fisheries, as well as between fisheries and military use. If fishermen can be encouraged to support MPA zoning, sustainable fisheries devel-opment and marine resource conservation can be achieved.

The uptake of MSP in Taiwan has been remarkably rapid in response to sea use conflicts. These resulted from regulations for individual marine activities, dispersed among numerous laws operating at different scales, based on different mapping methods and implemented by various government agencies.52 The National Council for Sustainable Development established in 1997 set up a Sustainable Development Action Plan that emphasized MSP based on the ecosystem approach advanced at Rio de Janeiro and Johannesburg.

© 2013 Koninklijke Brill NV ISBN 978 90 04 25045 1

International Progress in Marine Spatial Planning 181

<UN>

53. W.H. Liu and C.C. Wu, Marine Spatial Planning and Management in Taiwan (II) (Taipei: National Science Council, 2009).

54. Boyes et al., n. 51 above.55. Liu and Wu, n. 53 above.56. H. Li, “China’s Sustainable Ocean and Coastal Development Strategy in 21st Cen-

tury,” available online: <http://iwlearn.net/abt_iwlearn/events/iwc2002/26sept/welcome _plenary/lhaiqing_iwckeynotespeech.ppt>.

57. Y. Liu, A. Feng and S. Wu, “Assessment methods and case study of the implementa-tion of marine functional zoning,” Ocean Development and Management (in Chinese) 26 (2009): 12–17.

58. Technical Guidelines for Marine Functional Zoning GB17108 (1997), GB/T17108 (2006), available online: <http://www.tsinfo.js.cn/inquiry/gbtdetails.aspx?A100=GB/ T%2017108-2006>.

59. Law of PRC on the Use of Sea Areas (Beijing: China Ocean Press, 2001).

Challenges and Future Directions

The government agencies still perform poorly in negotiation, leading to competition between sea uses.53 The development of appropriate administrative and legislative mechanisms is required for the implementation of a zoning scheme, within an a priori MSP system.54 According to the draft National Land Planning Act Regulations, the Ministry of the Interior is responsible for MSP in Taiwan, and sea areas will be included in territorial planning via the regional plan. However, the Act faces objec-tions from fishermen who consider that they will lose their rights. The government (i.e., Ocean Affairs Council or the Ministry of the Interior) should set up a reasona-ble timing and spatial arrangement for sea uses to integrate so that fishermen can still earn a living.55

China

Legislative and Administrative Developments

MSP in China is called Marine Functional Zoning (MFZ), and has been practiced since the late 1980s. It was originally conducted by the leading agency for marine affairs in China, the State Oceanic Administration (SOA), with some pilot projects and ministerial regulations.

From 1989 to 1995, SOA completed the first MFZ scheme on a small scale (1:200,000). In 1997, the SOA began to revise the MFZ scheme on larger scales for normal (1:50,000) and special areas (1:10,000).56 The SOA also announced legisla-tion to direct the operation, and in 1997 proposed a national law to manage sea area use.57 Meanwhile, the State Bureau of Technical Supervision promulgated the Technical Guidelines for Marine Functional Zoning (1997), which were replaced in 2006 by an updated version.58 In 2002, a national law governing MFZ, the Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Use of Sea Areas (Sea Areas Law), came into force.59

© 2013 Koninklijke Brill NV ISBN 978 90 04 25045 1

182 Coastal and Marine Spatial Planning

<UN>

60. National Marine Functional Zoning (2001–2010), available online: <http://www .sdpc.gov.cn/zcfb/zcfbqt/qt2003/t20050614_7337.htm>.

61. W. Luan and D.A. “The fundamental programs of marine functional zoning of China,” Human Geography (in Chinese) 17 (2002): 93–95.

62. National Marine Functional Zoning (2011–2020), available online: <http://www .china.org.cn/environment/2012-04/26/content_25238317.htm>.

63. H. Li, “The impacts and implication of the legal framework for sea use planning and management in China,” Ocean and Coastal Management 49 (2006): 717–726.

64. Liu and Wu, n. 53 above.

Implementation

The implementation of the MFZ system is conducted primarily by the SOA in con-sultation with other relevant ministries and coastal provinces, autonomous regions, and municipalities, under the overall supervision of the State Council. This follows comprehensive guidelines on zoning and the responsibilities of the various govern-mental organizations for ocean management. To implement the MFZ scheme, the SOA adopted the Regulations on Marine Functional Zoning, 2007.60

In 2002, the National Marine Functional Zoning Scheme was announced with the approval of the State Council. As required by the Sea Areas Law, the Scheme was based on extensive data collection, intensive research and consultations with marine-related industries, and designated ten types of functional zones.61 The coastal provinces were required to adjust their individual zoning categories and operating systems accordingly, for submission to the State Council for approval. The new National Marine Functional Zoning scheme (2011–2020) was approved in 2012.62 This scheme classifies China’s sea areas according to eight types of func-tional zoning.

Outcomes and Assessment of Progress

Since the initiation of the sea use planning and zoning system three decades ago, many positive changes have been observed.63 The system has been applied in the whole ocean area as an instrument to handle sea use conflicts. All of the national and provincial marine development plans must be based on the zoning scheme. The system has become the legal basis of the management of sea use and for marine resources conservation and environmental protection.64

The implementation of the MFZ scheme marks the establishment of a planning system and an integrated policy framework for ocean development and management in China. The system has been largely driven by sustainability concerns, and sets out the goal of the rational development and sustainable use of the sea.

© 2013 Koninklijke Brill NV ISBN 978 90 04 25045 1

International Progress in Marine Spatial Planning 183

<UN>

65. P. Wang, Y. Liu, L. Zhang, W. Chen and H. Hong “Discussion on Legislation of Marine Functional Zoning in China,” Marine Environmental Science (in Chinese) 25 (2006): 89–91.

66. Li, n. 63 above.67. Liu and Wu, n. 53 above.68. Act of 21 March 1991 on the Maritime Areas of Poland and Maritime Administration

(Journal of Laws 2003, No. 153, item. 1502, as amended).69. A. Cieślak, K. Ścibior, P. Jakubowska, A. Staśkiewicz and J. Zaucha, eds.,

Compendium on Maritime Spatial Planning Systems in the Baltic Sea Region (Gdańsk: Maritime Institute, 2009), available online: <http://www.im.gda.pl/images/ksiazki/2009 _compendium.pdf>.

Challenges and Future Directions

China is facing problems implementing MFZ due to the lack of implementation of the zoning system.65 Issues include the consolidation of the legal system needed to support the regulations; tracking, assessment and monitoring of the zoning scheme; and enforcing the order of sea use by eliminating activities that go beyond approved zones.66 China also needs to improve its design standards in zoning and integrate natural ecosystems, environmental economics, and socio-economic considerations into the functioning of zones.67

Poland

Legislative and Administrative Developments

Legislation for spatial planning covers all sea areas in Poland. Regulations concern-ing MSP (added in 2003) are contained in the 1991 Act on Maritime Areas of Poland and Maritime Administration.68 The agency responsible for drafting the plans is the Maritime Office under the Ministry for the Maritime Economy.69 The legislation does not establish a requirement to plan, and only general provisions are in place concerning the role of the plans and their regulatory importance. There is also a lack of regulations for implementing these provisions, although these are currently under preparation.

Implementation

Three pilot plans have been prepared to date, which are subject to full planning procedures, including public participation and public hearings. The pilot plans include the following:

© 2013 Koninklijke Brill NV ISBN 978 90 04 25045 1

184 Coastal and Marine Spatial Planning

<UN>

70. J. Zaucha, ed., Pilot Draft Plan for the West Part of the Gulf of Gdańsk. First Maritime Spatial Plan in Poland (Gdańsk: Maritime Institute, 2009), available online: <http://www .im.gda.pl/images/ksiazki/2010_pilot-draft-plan_zaucha.pdf>.

71. J. Zaucha and M. Matczak, Developing a Pilot Maritime Spatial Plan for the Southern Middle Bank (Gdańsk: Maritime Institute, 2011), available online: <http://www.baltseaplan .eu>.

72. B. Käppeler, S. Toben, G. Chmura, S. Walkowicz, N. Nolte, P. Schmidt, J. Lamp, C. Göke and C. Mohn, “Developing a Pilot Maritime Spatial Plan for the Pomeranian Bight and Arkona Basin,” (2011), available online: <http://www.baltseaplan.eu>.

• Spatial plan for part of the internal sea waters of the Gulf of Gdańsk (40,550 ha of the sea area adjacent to the Gdańsk metropolitan area and tourist resorts of the Hel Peninsula);70

• Pilot maritime spatial plan for the Southern Middle Bank (1,751 km2 of the Polish and Swedish EEZ);71 and

• Pilot maritime spatial plan for the Pomerania Bight and Arkona Basin (14,110 km2 of the waters off Poland, Sweden, Germany and Denmark).72

For the Gulf of Gdańsk plan, a pilot strategic environmental assessment (SEA) report has also been prepared. Due to their pilot character, the plans have no formal stand-ing, but they are being used by the Maritime Administration as the source of best available knowledge in guiding decisions on the use of sea space (e.g., issuing per-mits, establishing use restrictions, etc.). The pilots have also enabled Poland to explore how transboundary cooperation can be achieved with neighboring mari-time nations. Sea areas have been included in the National Spatial Development Concept approved by the Polish government in 2011.

Overall and Assessment of Progress

The pilot plans have been developed in line with the concept of ecosystem services, and the protection of the marine environment and navigation have been given top priority. The delimitation of sea sub-areas (for which different use priorities and restrictions have been formulated) was based on ecological criteria. In addition to assigning the conservation of ecologically valuable areas as a leading function, the plans established areas for fisheries well-being and protection of underwater cul-tural heritage. Commercial use is allowed only if not in conflict with shipping and nature conservation. In the case of insufficiently precise information, the precau-tionary principle has been applied (e.g., scientific research should be carried out to determine whether areas should be opened to commercial uses).

Poland has now gained experience in MSP in EEZ and territorial waters. The first pilot plans and the SEA report have been prepared (some of them in collabora-tion with neighboring countries) and publicly discussed. Existing legislation has been checked, gaps have been detected, and work on legislative improvements has begun. The possible contribution of MSP to the development of ecosystem services

© 2013 Koninklijke Brill NV ISBN 978 90 04 25045 1

International Progress in Marine Spatial Planning 185

<UN>

73 Directive 2008/56/EC, n. 20 above.74 M. Schubert, “Rechtliche Aspekte der maritimen Raumordnung unter besonderer

Berücksichtigung der Fischerei,” in Marine Raumordnung – Interessenkonflikt mit der Fischerei oder Werkzeug für das Management, M. Lukowicz and V. Hilge, eds., (Hamburg: Arbeiten des Deutschen Fischerei-Verbandes, 2009), pp. 51–82.

75 M. Kment, “Raumordnungsgebiete in der deutschen Ausschließlichen Wirtschaftszone – Ein Plädoyer für eine Novelle nach der Novelle,” Die Verwaltung 40 (2007): 53–74.

76 N. Nolte, “Nutzungsansprüche und Raumordnung auf dem Meer,” Hansa International Maritime Journal 9 (2010): 79–83.

has been outlined, as well as the limits to and opportunities for the use of MSP in implementing the EU’s MSFD.73 Obstacles to MSP, including governance problems and information and stakeholder participation gaps, have also been identified and necessary measures have been proposed.

Challenges Faced and Future Directions

The main challenge is the need to integrate MSP more into the national spatial plan-ning system as set out in the National Spatial Development Concept. Improved leg-islation is required to implement this. Also, financial constraints on MSP beyond the pilot areas are a major challenge. Finally, increasing demand for Polish sea space in the absence of maritime spatial plans may result in the development of maritime activities on a case-by-case permit basis.

Germany

Legislative and Administrative Developments

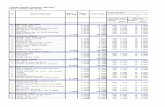

Germany has a strong legal and administrative framework for MSP. Different legal backgrounds and administrative bodies need to be considered due to the federal organization of the country (Figure 1). Within territorial waters (i.e., 12-NM zone) spatial planning has long been possible under the same terms as on land.74 The legal basis is provided by Bundesraumordnungsgesetz (Federal Spatial Planning Act) and the supplementary Landesplanungsgesetze (State Spatial Planning Acts) of the three coastal states Niedersachsen, Schleswig-Holstein, and Mecklenburg-Vorpommern. These states are responsible for MSP in their territorial waters and all of them have established MSP plans. Significance and the level of detail, however, differ from state to state.

For the EEZ, the federal government received jurisdiction over MSP by Europarechtsanpassungsgesetz Bau (European Law Adaptation Act) in 2004.75 MSP ordinances for Germany’s EEZ waters in the North Sea and the Baltic Sea have been in force since 2009.76

© 2013 Koninklijke Brill NV ISBN 978 90 04 25045 1

186 Coastal and Marine Spatial Planning

<UN>

77. W. Erbguth, M. Schubert, C. Grünwald, W. Hülsmann, H. Janssen, A. Kannen, J. Lamp, N. Nolte and R. Wenk, Maritime Raumordnung – Interessenlage, Rechtslage, Praxis, Fortentwicklung (Hannover: ARL, 2012).

Implementation

In Germany’s territorial waters MSP was always legally possible, but it was only in 2001 that the Conference of Ministers for Spatial Planning requested the coastal states to develop MSP. A first plan was implemented by Mecklenburg-Vorpommern in 2005. The other coastal states followed by mainly mapping existing uses in their MSP plans, arguing that marine space in their waters is very limited and additional uses (e.g., wind farms) should be approved only for test and demonstration pur-poses. This, along with intense coastal tourism, means that wind farms have become a major issue for the EEZ plans, but only play a minor role in the coastal marine plans.

In general, spatial planning in territorial waters is still limited to state-wide planning with a more strategic perspective. This is partly explained by large MPAs which set the framework for MSP, especially in the territorial North Sea waters (Wadden Sea World Heritage Site). For territorial waters it is disputed whether MSP should be more detailed.77 Revisions of initial MSP plans will be carried out

Source: Compiled by the authors.

Figure 1.—German spatial planning system

© 2013 Koninklijke Brill NV ISBN 978 90 04 25045 1

International Progress in Marine Spatial Planning 187

<UN>

78. S. Jay, T. Klenke, F. Ahlhorn and H. Ritchie, “Early European experience in marine spatial planning: Planning the German exclusive economic zone,” European Planning Studies (2012): (in press).

79. Interdepartementaal Directeurenoverleg Noordzee, Integraal Beheerplan Noordzee 2015, (The Hague: Interdepartementaal Directeurenoverleg Noordzee, 2008).

periodically. Mecklenburg-Vorpommern plans to publish a new marine plan in 2013. In all cases stakeholder consultations are important, including cross-border consultations.

Outcomes and Assessment of Progress

Despite their wide geographical scope, especially in the EEZ, plans legally cover only a limited number of uses. They do not provide a framework for the designation of zones for mineral extraction, fisheries, mariculture, defense, tourism or MPAs.78 This may be seen in the context of Germany’s energy policy, where the development of offshore wind farm capacity plays a major role.

In Germany, spatial planning is generally understood as a tool for achieving sustainable development. The sustainability principles of the Rio 1992 and Johan-nesburg 2002 Summits are reflected by the Bundesraumordnungsgesetz (Federal Spatial Planning Act). MSP follows this tradition. Nevertheless, it needs to be further developed and accompanying tools are necessary to safeguard sustainable develop-ment in marine areas.

Challenges and Future Directions

MSP in Germany covers a variety of spaces and policy frameworks due to the federal structure of the country. Common to all plans is the question of whether MSP will be able to coordinate and balance the development of marine space. This is espe-cially true for the ecosystem approach where more knowledge about the marine environment and the impacts of anthropogenic activities is needed. This calls for a better integration of science and planning as well as for enhanced cross-border stakeholder consultation procedures.

The Netherlands

Legislative and Administrative Developments

In 2005, the Dutch government addressed MSP in the national spatial planning pol-icy paper (Nota Ruimte), which included a North Sea paragraph for the first time. This was complemented with the Integrated Management Plan for the North Sea 2015 (IMPNS2015).79 IMPNS2015 builds on three pillars as it aims for a healthy, safe, and profitable sea. A legal basis for the plan was lacking until 2008 when the new

© 2013 Koninklijke Brill NV ISBN 978 90 04 25045 1

188 Coastal and Marine Spatial Planning

<UN>

80. Ministry of Housing, Spatial Planning and the Environment (2008) Spatial Planning Act (Wet ruimtelijke ordening). (The Hague: Ministry of Housing, Spatial Planning and the Environment); Ministry of Transport, Public Works and Water Management (2009) Water Act (Waterwet). (The Hague: Ministry of Transport, Public Works and Water Management). Drankier, n. 26 above.

81. Interdepartementaal Directeurenoverleg Noordzee, Integraal Beheerplan Noordzee 2015 Herziening, (The Hague: Interdepartementaal Directeurenoverleg Noordzee, 2011).

82 F. Douvere and C. Ehler, “Ecosystem-based marine spatial planning: An evolving paradigm for the management of coastal and marine places,” Ocean Yearbook 23 (2009): 1–26.

83. Id.84. Interdepartementaal Directeurenoverleg Noordzee, n. 81 above.85. S. Jay, “Planners to the rescue: Spatial planning facilitating the development of off-

shore wind energy,” Marine Pollution Bulletin 60 (2010): 493–499; J. Van Leeuwen, “Who

Spatial Planning Act (and in 2009 the new Water Act) came into force, extending jurisdiction to the territorial sea and the Dutch EEZ.80 In November 2011, a revised IMPNS2015 was adopted.81

Planning within the territorial sea is the shared responsibility of municipal, provincial and national authorities. For the EEZ, sectoral interests and marine envi-ronmental protection are taken up by the national government (13 departments under five ministries). Since 1998, the Interdepartmental Directors’ Consultative Committee North Sea (IDON) has served as a coordinating body and is the main player in MSP.82

Implementation

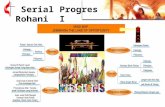

In the first IMPNS2015 (2008), the design of opportunity maps was a key tool in MSP, wherein the private sector was given scope to develop initiatives.83 In the new IMPNS2015 (2011), a stronger steering role for government in site selection is empha-sized, particularly for activities of national importance (e.g., offshore wind park development and sand extraction for coastal defense). If feasible, multiple use is preferred. The integrated framework contains five assessments: 1) defining the spa-tial claim with attention to the precautionary approach; 2) choice of location and evaluation of use of space (the expected interactions between activities are indi-cated in Figure 2); 3) proof of the “usefulness and necessity” for planning an activity in a particular location; 4) mitigation measures; and 5) assessing compensation measures.84

Outcomes and Assessment of Progress

In December 2008, five MPAs were designated in accordance with Natura 2000. Three years later, a fishery management plan for the coastal MPA was also agreed upon. Indications are that other activities such as shipping and gas and oil extraction will increasingly need to take into account the spatial claims of other activities, particularly those of national importance.85

© 2013 Koninklijke Brill NV ISBN 978 90 04 25045 1

International Progress in Marine Spatial Planning 189

<UN>

Nature

Gas Fountains

Central Oyster Grounds

Cleaver Bank

Interactions

Shipping

Oil and gasextraction

Fishing

Mineralretrieval /mining

Dredging

Windenergy

Cabling andpipelines

Recreation

Military use

LegendNatura 2000

Designated areasAreas to beselectedAreas with specialecological valueMilitary areasWind parksShipping lanesReserved areas forsand extraction

0 50 km

Coastal Sea

Voordelta

Adapted from IDON (2011)original is in Dutch

Vlakte vande Raan

ZeeuwseBanks

N

Frisian Front

North Seacoastal zone

BorkumseStones

Dogger Bank

Brown Bank

Figure 2.—Interactions between Dutch NATURA 2000 areas and maritime activities

Source: Interdepartmental Directors Consultative Committee (IDON) (2011) Integraal Beheerplan Noordzee 2015 Herziening. IDON, Den Haag, p. 29. Used with permission from IDON.

© 2013 Koninklijke Brill NV ISBN 978 90 04 25045 1

190 Coastal and Marine Spatial Planning

<UN>

greens the waves? Changing authority in the environmental governance of shipping and off-shore oil and gas production,” (Ph.D. diss., Wageningen University, 2010); J. van Tatenhove, “The Tide is Turning: The Rise of Legitimate EU Marine Governance,” (Lecture, Wageningen University, 27 October 2011).

86. E.K. Van Haastrecht and H.M. Toonen, “Science-policy interactions in MPA site selection in the Dutch part of the North Sea,” Environmental Management 47 (2011): 656–670.

87. The Swedish Planning and Building Act (SFS 1987:10).88. SOU 2010:91, Governmental Inquiry on MSP: Planning In Depth – Marine Spatial

Planning (Stockholm: SOU, 2010).

International sustainability obligations have accelerated MSP in the Dutch area of the North Sea.86 This not only concerns MPA site selection but also addressing negative impacts of climate change. Offshore wind energy is considered a promising renewable energy form, while sand extraction is important for coastal defense to counter sea-level rise.

Challenges and Future Directions

Challenges for the implementation of MSP in the Dutch EEZ include finding solu-tions for conflicting spatial claims of activities, and involving different stakeholders in the planning process. Another challenge is developing a strategy of regional coop-eration with neighboring states in order to find solutions for cross-border conflicts.

Sweden

Swedish MSP has long been merely coastal, with both geographical and institutional gaps, but it is currently developing. Marine management is conducted at two main levels: national, which is centralist and sector based; and local, via municipalities’ more integrative spatial planning. Actual MSP has so far only taken place at the municipal level and in territorial waters, but this is set to change.

Legislative and Administrative Developments

Since 1987, municipalities have been responsible for MSP in territorial waters, via municipal comprehensive planning (MCP) according to the Planning and Building Act.87 In addition, national authorities can designate sector priority areas under the Environmental Code, to be integrated into municipal planning. The County Administrative Boards (CABs) (regional bureaus of national authorities) coordinate municipal planning.

A complementary national system for the EEZ is now underway.88 Since 2011, the new Swedish Agency for Marine and Water Management (SwAM) has united previously separate functions. Its tasks comprise management of marine and

© 2013 Koninklijke Brill NV ISBN 978 90 04 25045 1

International Progress in Marine Spatial Planning 191

<UN>

89. Visit SwAM online: <http://www.havochvatten.se/en/start/marine-planning .html> for progress on marine plan areas.

90. Id.91. H. Ackefors and K. Grip, The Swedish Model for Coastal Zone Management, Report

4455 (Stockholm: Swedish EPA, 1995).92 A. Morf, “Participation and Planning in the Management of Coastal Resource

Conflicts: Case Studies in West Swedish Municipalities,” (Ph.D. diss., University of Gothenburg, 2006).

93. SOU 2010:91, n. 88 above.

freshwater environments, including MSP in the EEZ and the outer territorial waters. This also covers the implementation of international agreements such as the Baltic Sea Action Plan and relevant EU directives.

The Ministry of the Environment is preparing MSP legislation to be presented to the parliament by the end of 2012, with the ecosystem approach as a point of departure. The national marine plans should identify the most appropriate uses of sea areas, based on an appraisal of national and other public interests and may also contain binding provisions, such as conditions on certain activities subject to licens-ing. They are to be prepared for three basins: Gulf of Bothnia, Baltic Sea Basin, and Öresund to Skagerrak. For better cross-municipal coordination, there will be an overlap in the outer territorial waters.89 The process will be led by SwAM, in collabo-ration with the CABs and municipalities, and imply consultative participation, including at a transboundary level.90

Implementation

Sweden became a forerunner of MSP after the UN Stockholm Conference in 1972, with national priority areas and MCP for the integrated management of territorial waters, codified in 1987. Planning was seen as an important tool for addressing increasing pressures on coastal resources.91 Subsequently, the development of MSP slowed down, partly due to struggles between government levels and sectors. Municipal-level MSP slowed due to a lack of resources, capacity, and political inter-est.92 In 2010, only four out of 80 coastal municipalities included territorial waters in their MCP, while 27 had partial plans.93

Outcomes and Assessment of Progress

The focus of planning and evaluation has been onshore. The effects of MSP on marine uses and environment have yet to be evaluated systematically. Both the municipal and future national plans are, or will be, mainly directional in character, with the national plans being expected to give guidelines for licensing and manage-ment. MSP is also regarded as an important tool to implement the Marine Strategy Framework Directive, by improving the connectivity of protected areas, for

© 2013 Koninklijke Brill NV ISBN 978 90 04 25045 1

192 Coastal and Marine Spatial Planning

<UN>

94. Morf, n. 92 above; A. Morf, National and Regional Strategies with Relevance for Swedish Maritime Space, BaltSeaPlan Report 7 (Gothenburg: Swedish Institute for the Marine Environment, 2012).

95. E. Olsen, H. Gjøsæter, I. Røttingen, A. Dommasnes, P. Fossum and P. Sandberg, “The Norwegian ecosystem-based management plan for the Barents Sea,” ICES Journal of Marine Science 64 (2007): 599–602; G. Ottersen, E. Olsen, G.I. van der Meeren, A. Dommasnes and H. Loeng, “The Norwegian plan for integrated ecosystem-based management of the marine environment in the Norwegian Sea,” Marine Policy 35 (2011): 389–398.

96. Ministry of Environment, St.meld.nr. 8 (2005–2006) Helhetlig forvaltning av det marine miljø i Barentshavet og havområdene utenfor Lofoten ( forvaltningsplan) (Oslo: Ministry of Environment, 2006); Ministry of Environment, Meld.St.10 (2010–2011) Oppdatering av forvaltningsplanen for det marine miljø i Barentshavet og havområdene uten-for Lofoten (Oslo: Ministry of Environment, 2011).

97. Ministry of Environment, Helhetlig forvaltning av det marine miljø i Norskehavet ( forvaltningsplan) (Oslo: Ministry of Environment, 2009).

example. Authorities expect that there will be stronger guidance for steering devel-opment to appropriate areas, while users expect better-defined rights of use, such as in regard to licensing.

Challenges and Future Directions

Today, Sweden is progressing again, driven by increasing conflicts between marine uses and conservation, poor environmental status in the Baltic, and related EU and regional initiatives.94 National MSP is expected to start right after adoption of the legislation, and the first plans may be ready by 2017.

Norway

Legislative and Administrative Developments

MSP in Norway is being developed by means of integrated management plans. These can be traced to the 1992 Rio Declaration, the 1995–2002 North Sea Ministerial Conferences, and the 2002 Johannesburg Declaration, all of which have sustainable development and ecosystem-based management of ocean ecosystems as funda-mental aims.

So far, two management plans have been developed: for the Lofoten-Barents Sea and the Norwegian Sea.95 The process began in the north (Lofoten-Barents Sea) as this area has only one border (with Russia) and there was a push from the petro-leum industry to gain access to this region. Stortinget (parliament) approved the plan in 2006 and revised it in 2011.96 The Norwegian Sea plan was approved in 2009 and is due for revision in 2014.97 A plan for the North Sea is under development for 2013 (Figure 3). Rather than being implemented through new legislation, the plans

© 2013 Koninklijke Brill NV ISBN 978 90 04 25045 1

International Progress in Marine Spatial Planning 193

<UN>

are sanctioned through soft-law; the documents are government white papers (reports to Stortinget) that have been discussed and approved by a bipartisan majority.

Implementation

The planning process was initiated top-down by creating a ministerial steering group led by the Ministry of Environment, which tasked their institutions with

Figure 3.—Norway’s integrated management plan areas

Source: Institute of Marine Research and Norwegian Directorate for Nature Conservation (author).

© 2013 Koninklijke Brill NV ISBN 978 90 04 25045 1

194 Coastal and Marine Spatial Planning

<UN>

developing the plans. The process consisted of: 1) scoping and base-lining of human activities, the ecosystem and biologically valuable areas; 2) environmental impact assessment for shipping, petroleum, fishing, and external influences; and 3) aggre-gated analysis of impacts, definition of management goals, and knowledge gaps. Public consultation and meetings were held at various stages. Three cross-sectoral follow-up groups were created: 1) a monitoring group reporting on the state of the ecosystem; 2) a forum for environmental risk from human activities (e.g., oil spills); and 3) an advisory group reporting on achievement of goals and development of knowledge.

Outcomes and Assessment of Progress

The Barents Sea and Norwegian Sea plans have the same strategic objective: “to facilitate economic development through sustainable use of resources and goods … and … maintain the structure, functioning, productivity, and biodiversity of ecosys-tems.” Their main effect has been an area-based management framework (zoning plan) for the petroleum sector and International Maritime Organisation-approved shipping lanes. The plans have also created new cross-sectoral meeting places at ministerial and institutional levels.

MSP development has been initiated with strict delivery dates determined by Norway’s ambition to reach the goals set by the Rio and Johannesburg declarations. These are directly reflected in the plans’ goals and objectives.

Challenges and Future Directions

The plans were developed under strict deadlines with no scope for developing new methods or conducting research; hence, the plans identified gaps in current knowledge. The lack of empirical methods for assessing the total and cumulative impacts from multiple human pressures remains a major challenge. Achieving continued cross-sectoral cooperation also remains an ongoing challenge, as an inte-grated planning process requires some sectoral decisions to give way to joint deci-sion making.

The Norwegian plans have been quite successful in achieving results within just three to four years. They need to be developed further to accommodate expanding industries like renewable energy, but are a good framework to handle new and com-plex future challenges to the marine environment.

The United Kingdom

Legislative and Administrative Developments

MSP in the United Kingdom (generally referred to as marine planning) enjoys a strong regulatory framework thanks to landmark legislation. The Marine and Coastal

© 2013 Koninklijke Brill NV ISBN 978 90 04 25045 1

International Progress in Marine Spatial Planning 195

<UN>

98. Marine and Coastal Access Act 2009 c. 23 (Norwich: The Stationary Office); Marine (Scotland) Act 2010 asp 5 (Norwich: The Stationary Office).

99. Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs, Safeguarding Our Seas: A Strategy for the Conservation and Sustainable Development of our Marine Environment (London: DEFRA, 2002); Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs, A Sea Change: A Marine Bill White Paper, Cm 7047, (London: DEFRA, 2007); HM Government, Draft Marine Bill, Cm 7351, (Norwich: The Stationary Office, 2008); MSPP Consortium (2006) Marine Spatial Planning Pilot: Final Report, unpublished document.

100. S. Jay, “Mobilising for marine wind energy in the United Kingdom,” Energy Policy 39 (2011): 4125–4133.

101. HM Government, Northern Ireland Executive, Scottish Government & Welsh Assembly Government, UK Marine Policy Statement (Norwich: The Stationary Office, 2011).

102. See map online: <http://www.marinemanagement.org.uk/marineplanning/areas/index.htm>.

103. Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs, Implementing Marine Planning (London: DEFRA, 2009); Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs, A Description of the Marine Planning System for England (London: DEFRA, 2011).

Access Act 2009 and the Marine (Scotland) Act 2010 made provision for MSP through-out UK waters, as far as international boundaries permit.98 This followed a period of scientific discussion and policy development that received wide support, partly in response to EU and international treaty obligations.99 Moreover, recent public spending cuts have not deflected the MSP program.

The implementation of MSP has been devolved to the UK’s four constituent parts, with planning for the largest areas delegated to two new agencies: Marine Scotland and England’s Marine Management Organisation (MMO). The Northern Ireland and Welsh administrations have responsibility for planning their waters. Sectoral initiatives are also underway, including plans for offshore wind energy and marine conservation zones.100

Implementation

Planning activity started at a strategic level, with a national statement of marine policy that provides overarching objectives for the sea and general guidance for mar-itime interests.101 Marine plans must conform to this statement. As far as the situa-tion in England is concerned, the MMO has begun a rolling program of plan-making for the ten areas into which waters have been divided,102 beginning with North Sea areas that are under particular pressure for expanding sectors, such as offshore wind energy and ports and shipping.

The plan-making process places a strong emphasis on stakeholder consulta-tion.103 Also notable is the policy-focused approach, in line with UK terrestrial plan-ning practice. Rather than work towards a strict zoning system, as is frequently advocated for MSP, marine plans in the UK will provide guidance to inform marine licensing and give broad indications of suitable locations for particular activities.

© 2013 Koninklijke Brill NV ISBN 978 90 04 25045 1

196 Coastal and Marine Spatial Planning

<UN>

104. T. Appleby and P. Jones, “The Marine and Coastal Access Act: A hornets’ nest?,” Marine Policy 36 (2012): 73–77.

105. Id.106. Act on the Protection of the Marine Environment: Act 41/2010 of December 29, BOE

n° 317 December 30, 2010.

Outcomes and Assessment of Progress

Although no statutory marine plans have yet reached completion, the indications are that MSP in the UK will serve a wide range of interests, including emergent eco-nomic activities. But questions have been raised about the extent to which environ-mental aspirations will be met, such as habitat protection.104

The uptake of MSP in the UK has been remarkably rapid, partly driven by the ongoing sustainability concerns expressed at the Rio and Johannesburg Summits, to which direct reference was made during policy development. These are reflected in the high-level objectives at the heart of the UK’s marine policy statement.

Challenges and Future Directions

Despite MSP’s statutory standing in the UK, questions remain about its effective-ness. Marine plans, in line with the UK’s discretionary planning tradition, will not be the only factor when decisions are made about sea uses, and could be overridden by other considerations.105 Tensions and lack of integration between sectors and insti-tutions could still arise. Nonetheless, MSP is now established as a means of structur-ing marine activities in the UK and active stakeholder participation may be the key to ensuring real improvements in the marine environment and its governance.

Spain

Legislative and Administrative Developments

MSP, which enables the best use to be made of marine space, is developing into a working tool suitable for coordinating current sectoral issues in coastal zone man-agement. Spain has recently provided itself with this tool through the Act on the Protection of the Marine Environment (2010).106 This regulates the general principles and mechanisms for planning in the marine environment. It also transposes into Spanish legislation the EU MSFD, which sets out a framework for marine environ-mental policy.

Implementation

In the Act, the expression MSP only appears in an annex listing the type of measures that can be adopted in order to “achieve or maintain a good environmental status.”

© 2013 Koninklijke Brill NV ISBN 978 90 04 25045 1

International Progress in Marine Spatial Planning 197

<UN>

107 J.L. Suárez and J.C. Rodríguez, “The Spanish approach to marine spatial planning: Marine Strategy Framework Directive vs. EU Integrated Maritime Policy,” Marine Policy 36 (2012): 18–27.

108 Art. 7. Each strategy must contain: i) an initial assessment of the state of the marine environment; ii) establishment of good environmental status; iii) environmental aims; iv) monitoring programs; and v) a measures program (a total of 12 possible manage-ment measures are mentioned in general terms, one of which is marine spatial planning). Marine strategies will be approved by the government through a Royal Decree.

Allusions to “planning” seem to have a more generic meaning that can be identified with the planning of various sectors of activity. In other words, at no time does the law specify, detail or develop MSP, although in its wording there are elements that can be interpreted in this sense.107

The instrument that the law establishes for achieving the objective of good environmental status is that of strategies that will be drawn up for each of the areas into which the jurisdictional waters are divided. The law divides Spanish maritime space into five areas (Figure 4) called “demarcations” that correspond to what the MSFD calls “subdivisions.” Marine strategies are at the core of the Act on the Protection of the Marine Environment and constitute “the general framework with which the various sectoral policies and administrative actions that affect the marine environment must comply.”108

Source: Compiled by the authors.

Figure 4.—Subdivisions for implementing Spain’s Act on the Protection of the Marine Environment

© 2013 Koninklijke Brill NV ISBN 978 90 04 25045 1

198 Coastal and Marine Spatial Planning

<UN>

109. Revista Ambienta, N° 94, marzo 2011. Madrid, Ministerio de Agricultura, Alimentación y Medio Ambiente.

110. J.L. Suárez and J.C. Rodríguez, “Factores geopolíticos de la planificación espacial marina: territorio y política marítima,” in La ordenación jurídica del medio marino en España. Estudios sobre la Ley 41/2010 sobre protección del medio marino, E. Arana and F.J. Sanz Larruga, eds., (Madrid: Cívitas-Thomson Reuters, 2012), pp. 601–646.

111. C.F. Santos, Z.G. Teixeira, J. Janeiro, R.S. Gonçalves, R. Bjorkland and M. Orbach, “The European Marine Strategy: Contribution and challenges from a Portuguese perspec-tive,” Marine Policy 36 (2012): 963–968.

Outcomes and Assessment of Progress

Although the Spanish alternative energy sector is considered to be pioneering from an international perspective, marine energy projects have as yet not entered the construction phase, as a result of which MSP linked to these projects has hardly been developed.

Taking the Rio and Johannesburg Summit landmarks as its reference, the most important legislative initiative in Spain is Law 42/2007, which concerns natural her-itage and biodiversity. This law includes MPAs as a legal environmental concept that warrants protection for the first time.109

Challenges and Future Directions

The text of Law 41/2010 includes taking into consideration the formulation of maritime policy in a holistic fashion. It also suggests rethinking ocean strategy in keeping with the deep-rooted changes that are taking place in the marine domain and the need for laying the foundation for a new maritime economy. The type of planning linked to this law may not be the most suitable for driving the develop-ment of the maritime sectors, and although the goal of protecting the marine envi-ronment is today unquestioned, the law is insufficient for ensuring that it will be achieved.110

Portugal

Legislative and Administrative Developments