Diplomacy - Springer LINK

-

Upload

khangminh22 -

Category

Documents

-

view

0 -

download

0

Transcript of Diplomacy - Springer LINK

“Probably the most prolific contemporary writer on diplomacy is Professor Geoff R. Berridge. Each of his many books is impeccably well written and full of insights into the fascinating formation of modern diplomacy.”

—Robert William Dry, New York University, USA, and Chairman of AFSA’s Committee on the Foreign Service Profession and Ethics

“I discovered Geoff Berridge’s book on diplomacy after serving as a diplomat for over 30 years. It is well-researched, sophisticated, inspiring and, where the subject invites it, suitably ironic. I used the 4th edition with my students and will now continue working with the 5th edition.”—Dr Max Schweizer, Head Foreign Affairs and Applied Diplomacy, ZHAW School of

Management and Law, Switzerland

“Berridge’s Diplomacy is an enlightening journey that takes the student, the practitio-ner and the general reader from the front to the backstage of current diplomatic practice. The thoroughly updated and expanded text—also enriched with a stimulat-ing new treatment of embassies—is an invaluable guide to the stratagems and out-comes, continuities and innovations, of a centuries’ long process.”

—Arianna Arisi Rota, Professor of History of Diplomacy at the University of Pavia, Italy

“This is an excellent text-book which fills a gap in the current writing on diplomacy.”—Lord Wright of Richmond, Permanent Under-Secretary of State at the Foreign

Office (UK), 1986–91

“This book remains the best introduction to the subject.”—Alan Henrikson, Director of Diplomatic Studies, The Fletcher School of Law and

Diplomacy, USA

“Berridge is the leading authority on contemporary diplomatic practice.”—Laurence E. Pope, former US ambassador and senior official at the Department

of State

“Berridge’s study of diplomacy is the standard text on the subject—succinct yet sub-stantial in content, lucid in style.”

—John W. Young, Professor of International History, University of Nottingham, UK

Diplomacy

Note: the first edition was published by another publisher.ISBN 978-3-030-85930-5 ISBN 978-3-030-85931-2 (eBook)https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-85931-2

© The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s), under exclusive licence to Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2022. 2015, 2010, 2005, 2002This work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed.The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use.The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, expressed or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. The publisher remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

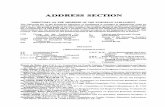

Cover illustration: The front cover shows a meeting in Geneva in 2016 of the World Health Assembly, the main decision-making body of the World Health Organization. Credit: Xinhua / Alamy Stock Photo.

This Palgrave Macmillan imprint is published by the registered company Springer Nature Switzerland AG.The registered company address is: Gewerbestrasse 11, 6330 Cham, Switzerland

G. R. BerridgePolitics and International RelationsUniversity of LeicesterLeicester, UK

DiploFoundationGeneva, Switzerland

Also by G. R. BerridgeBRITISH DIPLOMACY IN TURKEY, 1583 TO THE PRESENT: A Study in the

Evolution of the Resident EmbassyBRITISH HEADS OF MISSION AT CONSTANTINOPLE, 1583–1922

THE COUNTER-REVOLUTION IN DIPLOMACY and Other EssaysDIPLOMACY AND SECRET SERVICE: A Short Introduction

DIPLOMACY AT THE UN (co-editor with A. Jennings)THE DIPLOMACY OF ANCIENT GREECE: A Short IntroductionDIPLOMATIC CLASSICS: Selected Texts from Commynes to Vattel

DIPLOMATIC THEORY FROM MACHIAVELLI TO KISSINGER (with Maurice Keens-Soper, and T. G. Otte)

A DIPLOMATIC WHISTLEBLOWER IN THE VICTORIAN ERA: The Life and Writings of E. C. Grenville-Murray

ECONOMIC POWER IN ANGLO-SOUTH AFRICAN DIPLOMACY: Simonstown, Sharpeville and After

EMBASSIES IN ARMED CONFLICTGERALD FITZMAURICE (1865–1939), CHIEF DRAGOMAN OF THE

BRITISH EMBASSY IN TURKEYINTERNATIONAL POLITICS: States, Power and Conflict since 1945,

Third EditionAN INTRODUCTION TO INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS (with D. Heater)THE PALGRAVE MACMILLAN DICTIONARY OF DIPLOMACY: Third

Edition (with Lorna Lloyd)THE POLITICS OF THE SOUTH AFRICA RUN: European Shipping and

PretoriaRETURN TO THE UN: UN Diplomacy in Regional Conflicts

SOUTH AFRICA, THE COLONIAL POWERS AND ‘AFRICAN DEFENCE’: The Rise and Fall of the White Entente, 1948–60

TALKING TO THE ENEMY: How States without ‘Diplomatic Relations’ Communicate

TILKIDOM AND THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE: The Letters of Gerald Fitzmaurice to George Lloyd

ix

This edition of Diplomacy: Theory and Practice has been updated throughout and—despite the excision of some long passages that I concluded were either out of place or no longer important—considerably expanded. With the Covid-19 pandemic in mind and because I had ignored it in previous edi-tions, health diplomacy finds a major place for illustrative purposes. Among other subjects new to this edition are capacity-building in following up, embassy branch offices, the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, interpreters at summits, and—unavoidably—the diplomatic implications of former US President Donald J. Trump. Subjects covered in the previous edi-tion but to which increased attention is given in this one include the use of embassies for transnational repression, video-conferencing, Twitter, intelli-gence officers on special missions, and the variation in representative offices by degree of diplomatic status.

An innovation to which I must give special notice is the addition at the end of each chapter of a list of ‘Topics for seminar discussion or essays’. This draws not only on my teaching career but also on my long experience of vetting draft exam questions while an external examiner at five British universities. A good question should be short and clear—and provoke thought, which is therefore what I have tried to achieve on these lists. A few cautions: first, very few of these questions can be answered well by reliance on this book alone, hence the ‘Further reading’; second, some questions overlap, which does not matter unless they are used by a lecturer setting an exam; and third, most lists feature a comparative question (e.g., ‘Compare the roles of Austria and

Preface and Acknowledgments

x Preface and Acknowledgments

Switzerland in conflict resolution’ in the chapter on mediation), for advice on answering which, as well as on other points, see ‘7 common pitfalls to avoid in writing essays and dissertations’ on my website.

In order to give better guidance on further reading at the end of each chap-ter, here and there I have annotated the works listed. Other things being equal, I have also given preference to sources freely available on the Internet. As in earlier editions, I have avoided providing URLs for such sources, partly because they are often so long, partly because they tend to change or disap-pear, and partly because it is usually easy enough to find a web resource via a search engine; I simply add ‘[www]’ to a reference available on the Internet at the time of writing, although a few might be behind paywalls.

I do not believe that footnotes or endnotes are appropriate for a textbook. However, sources for quotations must be provided and I do this by means of in-text citations of full references to be found at the end of the book. Also, where a box relies chiefly on primary sources I provide these at the foot of the box itself.

The sources for unreferenced recent events are usually serious news agencies such as Reuters, news websites such as Politico, and online versions of newspa-pers such as The Guardian (which has no paywall). For many points in the text, the sources are my own earlier writings or works listed in ‘Further read-ing’ that should be fairly obvious. Works listed in ‘References’ at the end of the book include all those cited in the text, together with the more important among those on which I have drawn that are not listed in ‘Further reading’. In providing book titles, it is an idiosyncrasy of mine that I put the name of the publisher before place of publication, because I find this intuitive and because publishers have been doing the same thing on the title pages of their own books for well over half a century. (Students beware! You will probably incur the wrath of your tutors if you follow my example.)

As usual, I have prepared the Index myself. Due to production difficulties and space limitations, it is much shorter than before and I have concentrated the entries on diplomatic activity, procedures and institutions at the expense of countries and—with notable exceptions—persons. I believe the Index is not seriously the worse for its relative brevity.

For valuable observations on parts of the text of this edition, I am grateful to Christiaan Sys, Petru Dumitriu, John W. Young, Keith Hamilton, and my daughter Willow Berridge. For sharing with me raw data from her research on health attachés, I am in debt to Sabrina Luh. I must also mention Jelena

xi Preface and Acknowledgments

Jakovljevic, who has for many years expertly managed my website, on which the book is updated. Finally, I wish to thank most warmly the two anony-mous readers of my proposal for this edition for giving me valuable ideas that have shaped the final draft and Anne-Kathrin Birchley-Brun of the publisher for her patient and prompt support throughout. The responsibility for all remaining deficiencies is mine alone.

Leicester, UK G. R. Berridge May 2021

xiii

For each chapter in the book there is a corresponding page on my website, which is hosted by DiploFoundation. These pages contain further reflections, any corrections needed, and details of recent developments. Among other things, the website also has pages on ideas for dissertation and thesis topics, primary sources for study, recommended reading, and advice on essay and dissertation writing. Please visit http://grberridge.diplomacy.edu/ Links to other sites/organizations made to the content of this book by the publisher do not necessarily reflect the views of the author.

Online Updating

xv

1 The Foreign Ministry 1Staffing and Supporting Missions Abroad 5Policy-Making and Implementation 6Coordination of Foreign Relations 12Dealing with Foreign Diplomats at Home 15Building Support at Home 16Summary 17Further Reading 17

Part I The Art of Negotiation 21

2 Prenegotiations 23Agreeing the Need to Negotiate 24Agreeing the Agenda 27Agreeing Procedure 29

Secrecy 30Format 30Venue 33Delegations 36Timing 38

Summary 39Further Reading 39

3 ‘Around-the-Table’ Negotiations 41The Formula Stage 41The Details Stage 45

Contents

xvi Contents

Difficulties 46Negotiating Strategies 47

Summary 50Further Reading 50

4 Diplomatic Momentum 53Deadlines 55

Self-imposed Deadlines 55External Deadlines 56Symbolic Deadlines 58Overlapping Deadlines 59

Metaphors of Movement 60Publicity 63Raising the Level of the Talks 65Summary 66Further Reading 67

5 Packaging Agreements 69International Legal Obligations at a Premium 70Signaling Importance at a Premium 71Convenience at a Premium 73Saving Face at a Premium 74

Both Languages, or More 75Small Print 76Euphemisms 78‘Separate but Related’ Agreements 79

Summary 80Further Reading 81

6 Following Up 83Early Methods 84Monitoring 87Review Meetings 90Capacity-Building 94Summary 95Further Reading 95

xvii Contents

Part II Diplomacy with Diplomatic Relations 99

7 Embassies 101The Normal Embassy 105The Fortress Embassy 115The Mini-Embassy 118The Militarized Embassy 119Summary 121Further Reading 122

8 Telecommunications 125Telephone Diplomacy Flourishes 126Video-Conferencing Peaks 133Summary 137Further Reading 138

9 Consulates 141Consular Functions 146Career Consuls 149Honorary Consuls 152Consular Sections 154Summary 155Further Reading 155

10 Secret Intelligence 159Ambassadors as Agent-Runners 160Service Attachés 161Intelligence Officers 163Cuckoos in the Nest? 169Summary 175Further Reading 176

11 Conferences 179International Organizations 181Procedure 183

Venue 183Participation 184Agenda 189Public Debate and Private Discussion 190Decision-Making 191

xviii Contents

The ‘New Multilateralism’ 195Summary 196Further Reading 197

12 Summits 199Professional Anathemas 200General Case for the Defense 203Serial Summits 204Ad hoc Summits 206The High-Level Exchange of Views 208Secrets of Success 209Summary 212Further Reading 213

13 Public Diplomacy 215Rebranding Propaganda 215The Importance of Public Diplomacy 217The Role of the Foreign Ministry 219The Role of the Embassy 222Summary 225Further Reading 226

Part III Diplomacy Without Diplomatic Relations 229

14 Embassy Substitutes 231Interests Sections 231Consulates 236Representative Offices 238Front Missions 242Summary 243Further Reading 244

15 Special Missions 247The Advantages of Special Missions 247The Variety of Special Missions 249

Unofficial Envoys 249Official Envoys 251

To Go Secretly or Openly? 255Summary 257Further Reading 258

xix Contents

16 Mediation 261The Nature of Mediation 262Different Mediators and Different Motives 264

Track One 264Track Two 267Multiparty Mediation 268

The Ideal Mediator 270The Ripe Moment 273Summary 274Further Reading 275

Conclusion: The Counter-revolution in Diplomatic Practice 277

References 281

Index 295

xxi

AU African Union [formerly Organization of African Unity]BCE Before the Common Era [aka ‘BC’]CGTN China Global Television NetworkCHOGM Commonwealth Heads of Government MeetingCOP Conference of the Parties [as in COP21, the twenty-first conference of

the parties to the UNFCCC]CSCE Conference on Security and Cooperation in EuropeCSO Civil Society OrganizationsDFAT Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and TradeEU European UnionFAC Foreign Affairs Committee [British House of Commons]FAO UN Food and Agriculture OrganizationFAOHC The Foreign Affairs Oral History Collection of the [US] Association

for Diplomatic Studies and TrainingFARA Foreign Agents Registration Act [US]FCO Foreign and Commonwealth OfficeFCDO Foreign, Commonwealth & Development OfficeFRUS Foreign Relations of the United StatesFOIA Freedom of Information ActG7 Group of SevenG20 Group of 20GAVI Global Alliance for Vaccines and ImmunizationGCHQ Government Communications Headquarters [British]GRU Glavnoye Razvedyvatelnoye Upravleniye [Russian—formerly Soviet—

military intelligence]HHS Health and Human Services, US DepartmentHumint human intelligence-gathering

Abbreviations

xxii Abbreviations

IAEA International Atomic Energy AgencyICJ International Court of JusticeICRC International Committee of the Red CrossILC International Law CommissionIMF International Monetary FundISC Intelligence and Security Committee [British]JCPOA Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action [for Iran’s nuclear program]KGB Komitet Gosudarstvennoy Bezopasnosti [Committee for State

Security]KRG Kurdish Regional GovernmentMIRV multiple independently targetable re-entry vehicleMOU memorandum of understandingMSF Médecins sans Frontières [Doctors without Borders]NGO non-governmental organizationNPT Nuclear Non-Proliferation TreatyNSA National Security Agency [US]OAS Organization of American StatesOECD Organization for Economic Co-operation and DevelopmentOHCHR Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, UNOIG Office of Inspector General [US Department of State]OSCE Organization for Security and Co-operation in EuropeP5 Permanent 5 [on the UN Security Council: Britain, France, PRC,

Russia, United States]P5+1 P5 plus GermanyPCO Passport Control OfficerPLO Palestine Liberation OrganizationPNA Palestinian National AuthorityPNGed declared persona non grata—no longer welcomePRC People’s Republic of ChinaQDDR Quadrennial Diplomacy and Development Review [US]SALT I Strategic Arms Limitations Talks [first negotiations, 1969–72]S&T Science and TechnologySigint Signals intelligenceSIS Secret Intelligence Service [British; also known as MI6]SVR Sluzhba Vneshney Razvedki [successor to the KGB—Russian

External Intelligence Service]TECRO Taipei Economic and Cultural Representative OfficeTPO trade promotion organizationUNESCO UN Educational, Scientific and Cultural OrganizationUNFCCC UN Framework Convention on Climate ChangeUNICEF UN Children’s Fund, formerly UN International Children’s

Emergency Fund

xxiii Abbreviations

UNMOVIC UN Monitoring, Verification and Inspection CommissionUNSCOM UN Special Commission [on Iraq]USIA United States Information AgencyUSINT US Interests Section CubaUSIP United States Institute of PeaceVCCR Vienna Convention on Consular Relations (1963)VCDR Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations (1961)WMD weapons of mass destructionWHO World Health OrganizationWTO World Trade Organization [formerly General Agreement on Tariffs

and Trade]

xxv

Box 1.1 ‘Department of Foreign Affairs’ to ‘Department of State’ 2Box 1.2 Communications with Embassies 3Box 1.3 Foreign Ministries: Formal Titles Making a Point, and Some

Metonyms 4Box 1.4 Crisis Management 7Box 1.5 Should the Foreign Ministry Control Development Aid? 14Box 2.1 The Geneva Conference Format for Middle East Peace

Negotiations 32Box 3.1 Formula for an Anglo–Turkish Alliance, 12 May 1939 42Box 3.2 Nuclear Talks with Iran: The Details Stage 45Box 3.3 The Cost of Making Major Concessions Too Early 49Box 4.1 The Non-paper 54Box 4.2 The Chinese ‘Deadline’ on Hong Kong 56Box 4.3 The Good Friday Agreement, 1998 59Box 5.1 Treaty Registration with the UN 71Box 5.2 The ‘Treaty’ So-called 72Box 5.3 A Peace Treaty in the Wrong Language 75Box 6.1 Thai Tribute to the People’s Republic of China 85Box 6.2 Special Group on Visits to Presidential Sites: Iraq, 26 March–2

April 1998 88Box 6.3 The International Commission 91Box 7.1 Locally Engaged Staff and Diplomatic Immunity 106Box 7.2 Embassy Branch Offices 107Box 7.3 The Economic and/or Commercial Section 107Box 7.4 The Health Attaché 108Box 7.5 Embassies and Transnational Repression 114Box 8.1 The White House–10 Downing Street Hotline 126Box 8.2 The Reagan–Assad Telephone Call 130

List of Boxes

xxvi List of Boxes

Box 9.1 The Main Differences Between Diplomatic and Consular Privileges and Immunities 145

Box 9.2 European Convention on Consular Functions (1967) 146Box 9.3 Disgusted in Ibiza 148Box 9.4 Consular Districts 151Box 10.1 The British Secret Intelligence Service (SIS) 164Box 10.2 SIS and Passport Control Officer Cover 164Box 10.3 British Consulate-General Hanoi During the Vietnam War 166Box 10.4 Sigint Bases in Soviet Diplomatic and Consular Posts in the

Cold War 168Box 10.5 The State–CIA ‘Treaty of Friendship’, 1977 170Box 10.6 The Raymond Davis Affair, Pakistan 2011 171Box 10.7 The Five Eyes’ Alliance 174Box 11.1 The International Sanitary Conferences, 1851–1938 180Box 11.2 GAVI, the Vaccine Alliance 186Box 11.3 The UN Security Council: Question of Reform 188Box 11.4 Inflated ‘Delegations’ to the World Health Assembly, 2019 194Box 12.1 Philippe de Commynes 201Box 12.2 The Funeral Summit 207Box 12.3 The Role of the Interpreter 211Box 13.1 Twitter 218Box 13.2 ‘News Management’: Correcting Foreign Diplomatic

Correspondents 220Box 14.1 Protecting Powers and the VCDR (1961) 232Box 14.2 Protecting Powers: When the Old System Lingers 233Box 14.3 Diplomatic Acts and the VCCR (1963) 237Box 14.4 The Consulates in Jerusalem 238Box 14.5 The US/PRC Liaison Offices, 1973–1979 239Box 15.1 The New York Convention on Special Missions (1969) 248Box 15.2 About Lord Levy: Tony Blair’s Personal Envoy to the Middle

East and Latin America 249Box 15.3 James Clapper’s Secret Mission to North Korea, November 2014 254Box 16.1 Good Offices, Conciliation, and Arbitration 262Box 16.2 Dr Bruno Kreisky 266Box 16.3 Armand Hammer: Citizen-Diplomat 268Box 16.4 Action Group for Syria 269

xxvii

Diplomacy is an essentially political activity and, well resourced and skillful, a major ingredient of power. Its chief purpose is to enable states to secure the objectives of their foreign policies without resort to force, propaganda, or law. It achieves this mainly by communication between professional diplomatic agents and other officials designed to secure agreements. Although it also includes such discrete activities as gathering information, clarifying inten-tions, and engendering goodwill, it is thus not surprising that, until the label ‘diplomacy’ was affixed to all of these activities by the British parliamentarian Edmund Burke in 1796, it was known most commonly as ‘negotiation’—by Cardinal Richelieu, the first minister of Louis XIII of France, as négociation continuelle. Diplomacy is not merely what professional diplomatic agents do; it is carried out by other officials and by private persons under the direction of officials. As we shall see, it is also carried out through many different channels besides the traditional resident mission. Together with the balance of power, which it both reflects and reinforces, diplomacy is the most important institu-tion of our society of states.

The remote origins of diplomacy are probably to be found in the relations between the ‘Great Kings’ of the Near East in the second, or possibly even in the late fourth, millennium BCE. Its main features in these centuries were the dependence of communications on messengers and merchant caravans, of diplomatic immunity on codes of hospitality to strangers, and of the obser-vance of treaties on terror of the gods under whose unforgiving gaze they were confirmed. However, although apparently adequate to the times, diplomacy during these centuries remained rudimentary. In the main this would seem to be because it was not called on very often and because communications were slow, laborious, insecure, and unpredictable.

Introduction

xxviii Introduction

Not so much later but more varied and probably more effective in its meth-ods seems to have been the diplomacy of ancient China. As early as the last two decades of the eighth century BCE, in a large region of some hundreds of independent political entities well before the empire emerged in 221 BCE, there is evidence of what were probably already well-established diplomatic customs. Rulers themselves met in twos or threes, for example, to form mili-tary plans, affirm friendly relations, make peace, or settle a marriage alli-ance—although they convened ‘in the open, generally by lakes or on hills at more or less sacred spots’, a practice probably born in times ‘when rulers dared not open their capitals or cities to other rulers accompanied by retinues’ (Britton: 619). (However, princes in some friendly relationships made court visits of a highly ceremonial nature in order to solidify their friendships.) More numerous contacts were made by envoys of high rank enjoying the ‘extra-clan immunity’ of nobles; their missions were designed for similar pur-poses but also included the delivery of gifts and preparations for the princes’ conferences (Britton: 634). Treaties were solemnized by blood oaths, and mediation—uninvited as well as encouraged—was also a customary practice.

In the Greek world of the fifth and fourth centuries BCE, which included over 1000 city-states, conditions both demanded and favored an even more sophisticated diplomacy, and great advances were made. First and foremost, city-states appointed resident representatives to look after their interests abroad, albeit not from their own people but instead from citizens of the for-eign city-state, who for this reason bear a superficial resemblance to the mod-ern honorary consul (see Chap. 9). The proxenos, as he was known, who was usually an influential politician or judge, differed from the honorary consul in so far as he was expected to handle any high-level political matters that came up as well as the more mundane business of looking after visitors from the city he served. Even small city-states appointed many proxenoi. The ancient Greeks also employed large special missions, invented the oratorical techniques required to gain popular acceptance of a bad as well as a good argument (the art of rhetoric), publicized important treaties by inscribing them on stone or bronze pillars (stelai) located in temples or other sacred places, practiced mul-tilateral diplomacy in religious and military ‘leagues’, and employed media-tion more or less thinly disguised as arbitration in the settlement of many territorial disputes.

In late medieval Europe, the Byzantine Empire’s contribution in its declin-ing centuries was to what would now be called public diplomacy, turning its genius to ‘maintaining the illusion of world domination’ (Wozniac). Thus other rulers were treated as junior members of the Emperor’s ‘family of kings’; by means of elaborate ceremonial and extraordinary artifice, foreign envoys

xxix Introduction

and minor rulers visiting Constantinople were overawed by the Emperor’s power; and treaties were dressed up as unilateral decrees (‘golden bulls’), so that even the most humiliating concessions—including the payment of trib-ute to powerful barbarians on the Empire’s retreating frontiers—were made to appear as acts of imperial grace.

Toward the end of the Middle Ages and over the following centuries, the Republic of Venice had begun to set the pace, establishing new standards of honesty and technical proficiency in diplomacy; the relazioni, the detailed reports on all aspects of the country where ambassadors had served that were presented to the Senate at the end of their tours, became famous.

It was in the Italian city-states’ system—of which Venice was a prominent member—that in the late fifteenth century the recognizably modern system of diplomacy first made its appearance. The hyper-insecurity of the rich but poorly defended Italian states induced by the repeated invasions of their pen-insula by the powers beyond the Alps after 1494, made essential a diplomacy that was both continuous and conducted with less fanfare. Fortunately, no great barriers were presented by language or religion, and although communi-cations still depended chiefly on messengers on horseback, the relatively short distances between city states made this less of a drawback. It is not surprising, therefore, that it was this period that saw the birth of the genuine resident embassy; that is to say, in contrast to the proxenos, a resident mission headed by a citizen of the prince or republic whose interests it served.

The Italian system, the spirit and methods of which are captured so well in the despatches of Niccolò Machiavelli to the Florentine Ten of War, was later named the ‘French system of diplomacy’ by the British scholar-diplomat Harold Nicolson (Nicolson 1954: Ch. 3). He did this with some justification because it was Frenchmen—notably Cardinal Richelieu and François de Callières—who were so influential in refining its practice and developing its theory, and because French gradually replaced Latin as the working language of diplomacy. The French system was the first fully developed system of diplo-macy and the basis of the modern—essentially bilateral—system (see Chap. 7).

In the early twentieth century the French system was modified but not, as some hoped and others feared, transformed. The ‘open diplomacy’ of ad hoc and permanent conferences—notably the League of Nations—was simply grafted onto the existing network of bilateral communications, which weath-ered the attacks on it by the Communist regimes in Soviet Russia and, later, China, as it had done those of the French revolutionaries of the late eigh-teenth century. Why did diplomacy survive these assaults and continue to develop to such a degree and in such an inventive manner that, at the begin-ning of the twenty-first century, we can speak with some confidence of a

xxx Introduction

world diplomatic system of unprecedented strength? The reason is that the conditions that first encouraged the development of diplomacy have for some decades obtained perhaps more fully than ever before. These are a balance of power between a plurality of states, mutually impinging interests of an unusu-ally urgent kind, efficient and secure international communication, and rela-tive cultural toleration—the rise of radical Islam notwithstanding.

As already noted, diplomacy is an important means by which states pursue their foreign policies, and in many states these are still shaped in significant degree in a ministry of foreign affairs. Such ministries also have the major responsibility for a state’s diplomats serving abroad and for dealing (formally, at any rate) with foreign diplomats at home. It is for this reason that this book begins with the foreign ministry. Following this, it is divided into three parts. Part I considers the art of negotiation, the most important activity of the world diplomatic system as a whole. Part II examines the channels through which negotiations, together with the other functions of diplomacy, are pur-sued when states enjoy normal diplomatic relations. Part III looks at the most important ways in which these are carried on when they do not.

Further Reading

Adcock, F. and D. J. Mosley, Diplomacy in Ancient Greece (Thames and Hudson: London, 1975). Part 2, by Mosley.

Berridge, G. R. (ed.), Diplomatic Classics: Selected texts from Commynes to Vattel (Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, 2004).

Berridge, G. R., The Diplomacy of Ancient Greece: A short introduction (DiploFoundation: Geneva, 2018). Available on the ISSUU platform.

Berridge, G. R. et al (eds), Diplomatic Theory from Machiavelli to Kissinger (Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, 2001).

Britton, Roswell S., ‘Chinese interstate intercourse before 700 BC’, American Journal of International Law, vol. 29(4), 1935.

Bull, Hedley and Adam Watson (eds), The Expansion of International Society (Clarendon Press: Oxford, 1984).

Cohen, Raymond and Raymond Westbrook (eds), Amarna Diplomacy: The beginnings of international relations (Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, 2000).

Eilers, Claude (ed), Diplomats and Diplomacy in the Roman World (Brill: Leiden, 2009). Introduction and ‘Roman perspectives on Greek diplo-macy’ by Sheila L. Ager.

xxxi Introduction

Frey, Linda and Marsha Frey, ‘“The reign of the charlatans is over”’: the French revolutionary attack on diplomatic practice’, The Journal of Modern History, vol. 65(4), Dec., 1993.

Frodsham, J. D. (transl. and ed.), The First Chinese Embassy to the West: The Journals of Kuo Sung-T’ao, Liu Hsi-Hung and Chang Te-Yi (Clarendon Press: Oxford, 1974).

Hamilton, Keith and Richard Langhorne, The Practice of Diplomacy, 2nd edn (Routledge: London, 2011). Chs 1–4.

Jones, Raymond A., The British Diplomatic Service, 1815–1914 (Colin Smythe: Gerrards Cross, Bucks., 1983).

Liverani, Mario, International Relations in the Ancient Near East (Palgrave: Basingstoke, 2001). Intro. and ch. 10.

Machiavelli, Niccolò, trsl. by Christian E. Detmold, The Historical, Political, and Diplomatic Writings of Niccolo Machiavelli, (James R. Osgood: Boston, 1882), vol. III (‘Missions’) and vol. IV (‘Missions continued’). More com-monly known as the ‘Legations’, these are Machiavelli’s diplomatic des-patches sent back to Florence. Detmold’s English translation of the complete works is highly regarded and still, as far as I know, the only one available of the ‘Legations’.

Mack, William, Proxeny and Polis: Institutional networks in the Ancient Greek World (Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2015).

Mack, William (Project Director), Proxeny Networks of the Ancient World (a database of proxeny networks of the Greek city-states) [www].

Mattingly, G., Renaissance Diplomacy (Penguin: Harmondsworth, 1965).Meier, S. A., The Messenger in the Ancient Semitic World (Scholars Press:

Atlanta, GA, 1988).Mösslang, M, and T. Riotte (eds), The Diplomats’ World: A cultural history of

diplomacy, 1815–1914 (Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2008).Munn-Rankin, J. M., ‘Diplomacy in Western Asia in the early second millen-

nium B.C.’, Iraq, Spring 1956, vol. 18(1).Nicolson, Harold, The Evolution of Diplomatic Method (Constable:

London, 1954).Peyrefitte, Alain, The Collision of Two Civilisations: The British expedition to

China 1792–4, trsl. from the French by J. Rothschild (Harvill: London, 1993).

Queller, Donald E., The Office of Ambassador in the Middle Ages (Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, 1967).

Queller, Donald E., ‘The development of ambassadorial relazioni’, in J. R. Hale (ed), Renaissance Venice (Faber and Faber: London, 1974).

xxxii Introduction

Selbitschka, Armin. ‘Early Chinese diplomacy: “Realpolitik” versus the so- called tributary system’, Asia Major, vol. 28(1), 2015.

Sharp, Paul and Geoffrey Wiseman (eds), The Diplomatic Corps as an Institution of International Society (Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, 2007).

Skinner, Quentin, Machiavelli (Oxford University Press: Oxford, 1981). Ch. 1, The Diplomat.

Victoria Tin-bor Hui, ‘Toward a dynamic theory of international politics: insights from comparing ancient China and early modern Europe’, International Organization, vol. 58(1), Winter, 2004.

Wozniak, E. E., ‘Diplomacy, Byzantine’, in Dictionary of the Middle Ages, vol. 4 (Scribner’s: New York, 1984).