COURTSHIP BEHAVIORS, RELATIONSHIP VIOLENCE, AND BREAKUP PERSISTENCE IN COLLEGE MEN AND WOMEN

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

0 -

download

0

Transcript of COURTSHIP BEHAVIORS, RELATIONSHIP VIOLENCE, AND BREAKUP PERSISTENCE IN COLLEGE MEN AND WOMEN

http://pwq.sagepub.com/Psychology of Women Quarterly

http://pwq.sagepub.com/content/29/3/248The online version of this article can be found at:

DOI: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2005.00219.x

2005 29: 248Psychology of Women QuarterlyStacey L. Williams and Irene Hanson Frieze

Courtship Behaviors, Relationship Violence, and Breakup Persistence in College Men and Women

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

On behalf of:

Society for the Psychology of Women

can be found at:Psychology of Women QuarterlyAdditional services and information for

http://pwq.sagepub.com/cgi/alertsEmail Alerts:

http://pwq.sagepub.com/subscriptionsSubscriptions:

http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.navReprints:

http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.navPermissions:

What is This?

- Sep 1, 2005Version of Record >>

at UNIVERSITAS GADJAH MADA on October 11, 2013pwq.sagepub.comDownloaded from at UNIVERSITAS GADJAH MADA on October 11, 2013pwq.sagepub.comDownloaded from at UNIVERSITAS GADJAH MADA on October 11, 2013pwq.sagepub.comDownloaded from at UNIVERSITAS GADJAH MADA on October 11, 2013pwq.sagepub.comDownloaded from at UNIVERSITAS GADJAH MADA on October 11, 2013pwq.sagepub.comDownloaded from at UNIVERSITAS GADJAH MADA on October 11, 2013pwq.sagepub.comDownloaded from at UNIVERSITAS GADJAH MADA on October 11, 2013pwq.sagepub.comDownloaded from at UNIVERSITAS GADJAH MADA on October 11, 2013pwq.sagepub.comDownloaded from at UNIVERSITAS GADJAH MADA on October 11, 2013pwq.sagepub.comDownloaded from at UNIVERSITAS GADJAH MADA on October 11, 2013pwq.sagepub.comDownloaded from at UNIVERSITAS GADJAH MADA on October 11, 2013pwq.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Psychology of Women Quarterly, 29 (2005), 248–257. Blackwell Publishing. Printed in the USA.Copyright C© 2005 Division 35, American Psychological Association. 0361-6843/05

COURTSHIP BEHAVIORS, RELATIONSHIP VIOLENCE,AND BREAKUP PERSISTENCE IN COLLEGE MEN

AND WOMEN

Stacey L. WilliamsUniversity of Michigan

Irene Hanson FriezeUniversity of Pittsburgh

This study assessed college men’s (n = 85) and women’s (n = 215) courtship persistence behaviors (approach, surveillance,intimidation, mild aggression), which have been linked to stalking, and examined their relations to initial courtshipinterest, relationship development, and future violence and persistence, while also exploring the role of gender inthese relations. Findings showed individuals performed surveillance when initially more interested than the other.Whereas approach behaviors were positively associated with relationship establishment, surveillance and intimidationwere negatively associated. As predicted, results showed continuity in persistence and violence over the course of datingrelationships. For both genders, courtship mild aggression predicted relationship violence, and persistence behaviorspredicted similar persistence at breakup. Early behaviors may foreshadow violence and stalking-related behaviors inboth men and women.

Intimate partner violence takes various forms, althoughmuch research has focused on physically violent acts duringthe relationship (as can be seen in the majority of articlesin this special issue). Other forms of partner violence in-clude initial relationship persistence, or prestalking, andstalking during relationship breakup (see Davis & Frieze,2002). Few studies have asked the question of how behav-iors at various stages of the relationship might be relatedand if the same pattern of relations exists for women andfor men. In this article, we examine persistence or prestalk-ing behaviors performed during early courtship and theirrelation to future violence and persistence. More specif-ically, we look at the behaviors of approach, surveillance,intimidation, and mild aggression used by female and malecollege students to express initial romantic interest andhow these behaviors may relate to physical violence dur-ing the relationship and persistence behaviors at breakup.Many of the behaviors we are labeling as persistence havebeen previously classified by other researchers as indica-tions of stalking, although some are also generally classifiedas normal expressions of romantic interest (Davis & Frieze,2002). We believe that examining precisely such a range

Stacey L. Williams, Institute for Social Research, University ofMichigan; Irene Hanson Frieze, Department of Psychology, Uni-versity of Pittsburgh.

Address correspondence and reprint requests to: StaceyL. Williams, Institute for Social Research, University ofMichigan, 426 Thompson Street, Ann Arbor, MI 48106. E-mail:[email protected]

of behaviors, from regular courtship to clearly aggressivebehaviors, may provide insights into how relationship vi-olence and stalking-type breakup behaviors develop fromthe initial stage of courtship interest. For example, althoughsome of the courtship behaviors we examine may be con-sidered regular or benign, they may foreshadow behaviorsthat could be interpreted as mild forms of stalking withinthe context of breakup. Indeed, other researchers have ar-gued that, in another context, many of the activities in therepertoire of the stalker would be classified as courtly orromantic (Spitzberg & Cupach, 2003).

Persistence and Stalking Behaviors

Recent research has demonstrated that unwanted pursuitbehaviors, or stalking-type behaviors, can occur prior torelationship development (Emerson, Ferris, & Gardner,1998; Hall, 1998; Langhinrichsen-Rohling, Palarea, Cohen,& Rohling, 2002; Sinclair & Frieze, 2002). In fact, ini-tial courtship persistence or prestalking behaviors may berelatively common occurrences. Sinclair and Frieze stud-ied the stalking-related behaviors of individuals involvedin courtship experiences in which the love interest did notreciprocate love. In their study, they identified six typesof such courtship behaviors: approach, surveillance, intim-idation, hurting the self, mild and verbal aggression, andphysical violence. The majority of their college student sam-ple had performed courtship approach and surveillancebehaviors. In addition, many performed more severe be-haviors of intimidation and aggression. Although extreme

248

Courtship and Persistence Behaviors 249

aggressiveness was relatively uncommon, it still existed.This approach to persistence or prestalking is differentthan the traditional conceptualization of relational stalk-ing, which has focused on violent and harassing behaviorsperformed and experienced during relationship breakup(Tjaden & Thoennes, 1998). In general, rates of stalkingrange from 2% to 33%, depending on how stalking is de-fined and the sample characteristics (Spitzberg & Cupach,2003). Definitions of stalking, including legal ones, that relyon targets’ perceptions of fear result in rates of stalking con-siderably lower (8% of females and 2% of males; Tjaden &Thoennes, 1998) than reports of prerelationship persistencebehaviors. Rates of reported stalking tend to be higher whenvictims are asked if they feel they have been stalked than ifstrict legal definitions are used (Tjaden & Thoennes, 2002).

In the present study we use some of the behavioral in-dicators put forth by Sinclair and Frieze (2002) to examinea range of courtship and breakup persistence. That is, weexamine college students’ reports of performing these per-sistent or mild stalking actions toward the relationship tar-get. We chose to use behavioral-specific items rather thanlegal definitions because the goal of this article is to examinethe range of behaviors as they relate to future mild, as wellas more aggressive relationship and postrelationship behav-iors. Reliance on legal definitions, with their requirement ofvictim perception of fear would limit the scope of behaviorsto the most severe, leaving out the potential variation in be-haviors performed in everyday relationships. In addition, wepresume that the same behaviors could be labeled by the re-cipient as stalking or as normal courtship, regardless of theintent of the person performing the behaviors. Behaviorslegally classified as stalking include many actions that occurin everyday intimate relationships (Emerson et al., 1998).Common stalking-type behaviors include spying, sendingnotes or gifts, unannounced visits or calls, attempting toscare or harass the person being stalked, and actual vio-lence (Davis & Frieze, 2002). In their construction of theirstalking-related behavior scales, Sinclair and Frieze con-sulted previous scales that were based on legal definitionsof stalking, in addition to other sources of personal stalkingaccounts.

Courtship Behaviors in Relation to Future Violenceand Persistence

One of the main goals of this study is to address the unan-swered question of whether persistence behavior at the be-ginning of a relationship relates to relationship violence andend-of-relationship persistence or stalking-type behavior.Despite the “processual” approach taken in the study ofbreakup stalking, with some researchers stating that suchbehaviors can be predicted from prior behaviors or a con-tinuum of stages (e.g., Emerson et al., 1998), the relationbetween early courtship behaviors and future relationshipviolence and stalking behaviors has not been consideredin prior research. This absence from the literature is sur-

prising given that stalking behaviors are often preceded byprior violent acts during the relationship (Coleman, 1997).In addition, an examination of the correlates of relationshipviolence that occur during courtship may provide informa-tion to enhance violence prevention, before higher levelsof intimacy are attained (Sinclair & Frieze, 2002). Duringthe earliest stages of relationships, the level of acceptabilityfor future violence may be established (Billingham, 1987).Minor acts of aggression and related threats may even beviewed as normal in the early part of a relationship (Straus,Gelles, & Steinmetz, 1980). In the context of courtship,some individuals may view the use of violence as a signof caring. These types of positive views can result in vio-lence leading to a higher level of intimacy in the couple(Billingham, 1987). As such, we believe that seemingly be-nign types of courtship behaviors or even mildly aggressivebehaviors may be associated with various types of violenceduring and following the ensuing relationship. In this arti-cle, we begin our examination by assessing persistence be-haviors performed during initial courtship and then studytheir relation with later relationship violence and breakupstalking. We predict that persistence behaviors during ini-tial courtship will be positively related to violence duringthe relationship and to persistence behaviors during thebreakup of the relationship.

Contexts of Initial Interest, Relationship Development,and Gender

Deeper understanding of the context in which stalking-related behaviors or, in our case, persistence or prestalkingbehaviors, are performed may be helpful in the even-tual predictions of such behaviors. Overall, “the dynamiccharacteristic of most cases of what ultimately come tobe recognized as stalking involve efforts to establish (orreestablish) a relationship in the face of the other’s resis-tance” (Emerson et al., 1998, p. 289). In the context of un-requited love, one person’s attempt to love the other is metwith failure, resulting in a profound blow to self-esteem,followed by distress and erratic behavior in the person re-jected (Baumeister, Wotman, & Stillwell, 1993). Previousresearch has evidenced various types of stalking-type behav-iors in the context of an unrequited love scenario (Sinclair& Frieze, 2002). During the earliest stages of courtship,a one-sided initial interest (i.e., a scenario in which onepotential partner is more interested than the other) may re-flect this unrequited love scenario and result in intensifiedinitial courtship behaviors. Behaviors used to attract thepotential partner may include stalking-related behaviors.The present study systematically examines levels of initialinterest (i.e., self more interested than other, other moreinterested, mutual interest) and the use of initial courtshippersistence. We predict that initial interest, particularly aone-sided attraction, will predict the use of initial persis-tence behaviors, including more regular types of courtshipbehaviors and more aggressive or violent behaviors.

250 WILLIAMS AND FRIEZE

In addition, our interest in how early persistence be-haviors relate to later relationship violence and breakuppersistence behaviors assumes that relationships do de-velop despite the presence of these behaviors. That rela-tionships still develop highlights the possibility that somepersistence behaviors during early courtship are “success-ful.” Although it may be intuitive that targets of such be-havior would respond negatively to attempts of the actorto establish a relationship, several commonly held culturaland relationship beliefs support the possibility of success-ful prestalking behaviors. First, it is generally known thatWestern culture emphasizes hard work, determination, andreward for persistence (Rodgers, 1978), which are often ap-parent in depictions of love and relationship pursuit (Lloyd,1991). Such persistent efforts are often rewarded. Second,dating scripts involve approach behaviors, persistence, andromantic ideation (Lloyd, 1991; Rose & Frieze, 1993). In-dividuals on the receiving end of such romantic pursuitmay not interpret persistence or prestalking behaviors asinappropriate, but instead may be flattered and, in turn,return the affection. Finally, because minor acts of vio-lence and threats may be viewed as normal occurrencesearly in a relationship (Straus et al., 1980), these behav-iors might not be viewed as harmful or threatening, butinstead may bring the relationship to a higher level of inti-macy, as has been found with dating violence more generally(Billingham, 1987). In this way, minor acts of persistencebehaviors may enhance the pursuit effort leading to rela-tionship development. In this study, we explore the relationbetween courtship persistence behaviors and relationshipdevelopment. We predict that courtships with some formof these initial persistence behaviors will be more likely todevelop into dating relationships than those without thesebehaviors.

Another major question addressed in this work iswhether gender plays a role in the development and processof violent relationships. Findings regarding gender differ-ences in relationship violence and stalking behaviors areequivocal. Although controversial, researchers find overallsimilarities in frequency of violent behaviors between menand women (Archer, 2000; Makepeace, 1986), while ac-knowledging that women’s violent behaviors often are per-ceived by men as less serious than men’s and are less likely toinvolve injury threat (Sinclair & Frieze, 2002). Consideringstalking behaviors, some have found a higher prevalence ofbeing victimized in women than men (Tjaden, Thoennes, &Allison, 2002; White, Kowalski, Lyndon, & Valentine, 2002),whereas others have found minimal gender differences instalking behaviors (e.g., Sinclair & Frieze, 2002). Wheregender differences in behaviors do exist, they are usuallyfound in studies assessing specific types of stalking-relatedbehaviors. For example, Sinclair and Frieze found evidencethat males perform more approach, or regular courtshipbehaviors, whereas females are more likely to perform actsof surveillance, that is, attempts to make indirect contactwith the love interest by way of (seeming) serendipity. Ad-

ditional findings suggest that men persist longer in theirrelationship pursuit efforts (Baumeister et al., 1993), andsome researchers have argued that women may feel morecomfortable being aggressive within relationships than inother contexts (Frieze, 2000). Because research on initialcourtship persistence and prestalking behaviors is in its in-fancy, and no prior research has examined its relation toviolence at later stages of relationships, the present studyexplores the role of gender in the occurrence of such be-haviors and in the relations between the different forms ofpersistence and aggression. In line with prior research, wepredict gender differences in relationship violence, suchthat women will display more acts of mild violence thanmen.

The Present Study

To reiterate, in this investigation we examine persistencebehaviors performed by college men and women to at-tract a potential dating partner during early courtship byusing a list of behaviorally specific items. We assess the oc-currence of these behaviors in one-sided and mutually at-tractive courtships, and in courtships that have developedinto relationships versus those that have not. Finally, we ex-amine the relation between early courtship behaviors withviolence during the relationship and persistence at rela-tionship breakup. Based on the rationale provided above,we offer the following hypotheses, exploring the impact ofgender within each: (a) One-sided initial courtship interest,in which one is more interested than the potential partner,will predict the use of initial courtship persistence behav-iors by the person who is more interested; (b) relationshipswith some form of initial persistence behaviors will be morelikely to develop into dating relationships than those not in-volving these behaviors; (c) initial persistence behaviors willbe positively related to relationship violence; and (d) initialpersistence behaviors will be positively related to breakuppersistence behaviors.

METHOD

Participants

Study participants were 326 University of Pittsburgh intro-ductory psychology students. The final sample consisted of215 women and 85 men, after excluding those who hadnever been in a dating relationship or courtship (n = 6),were homosexual (n = 8), or indicated that neither theynor their courtship partner were initially attracted to eachother (n = 12; see Measurement below). Although therewere many fewer men than women, this gender ratio is typ-ical of the introductory psychology classes at the Universityof Pittsburgh. The majority of the sample was Caucasian(77%) and under age 21 (84%). There was some repre-sentation of other races, with 13% African American, 5%Asian, 4% mixed race, and 2% other. Participants also de-scribed their romantic/dating partners. Analyses of partner

Courtship and Persistence Behaviors 251

descriptions indicated partners were similar to participantsdemographically; the majority were Caucasian (78%) andunder age 21 (76%).

Procedure

Anonymous surveys were administered to students ingroups of 10 to 30. Students participated as partial fulfill-ment of a requirement to serve as a study participant for anIntroduction to Psychology course. The students selectedthe studies in which they wanted to participate. This studywas described as a study of “Loving When Your PartnerDoesn’t Love Back.” Students were informed that the sur-vey’s intent was to examine the courtship process and thatthey would answer questions about their feelings of lovingsomeone and how they demonstrated this love, as well asquestions about the relationship and breakup. If partici-pants had had more than one dating partner, they were toldto provide information about their longest relationship.

Measurement

Initial interest. Participants responded to one item ask-ing about their initial interest at the beginning of their re-lationship with the partner. Participants reported who wasinitially more attracted: them, their partners, both, or nei-ther. As stated previously, those indicating that neither per-son was attracted were dropped from analysis, as we believethese partners were qualitatively different than the others.

Persistence behaviors. The list of 24 persistence be-haviors (taken from Sinclair & Frieze, 2002) consisted ofboth nonviolent (e.g., sending notes) and potentially violent(physically harming) tactics used during courtship and afterrelationship breakup. These behaviors, which were origi-nally generated by considering legal definitions of stalkingand other descriptions of anecdotal stalking, represent arange of acts from normal courtship to persistent or violentbehaviors (see Sinclair & Frieze, 2002). We chose to usethis scale because it permitted an initial investigation intothe relation of relatively benign forms of behavior to morepersistent or violent behaviors. In the present study, partic-ipants were asked to report the frequency with which theyperformed each behavior to express interest in the otherperson and the frequency with which they performed thebehaviors during the breakup of the relationship or whenthey were considering doing so. Participants responded toeach item using a frequency scale to indicate how oftenthey performed the behaviors: 1 = never, 2 = rarely (onceor twice), 3 = occasionally (three or four times), 4 = repeat-edly (five or more times), and 5 = frequently (more than10 times).

Separate categories of persistence behaviors were cre-ated based on results of a factor analysis and according tothe distinctions made by Sinclair and Frieze (2002). A meanscore for each category was then created. Several of thescales were quite skewed and were therefore dichotomized

(i.e., 1 = any, 0 = none). Approach and surveillance mea-sures were more normally distributed and were kept asmean scores. The four categories are: (a) approach be-haviors such as sending notes, doing unrequested favors,attempting to communicate, asking the person out as afriend and asking the person out as a date (combined alphafor behaviors during courtship and after breakup = .74);(b) surveillance behaviors such as waiting where the per-son would be, going by the residence, showing up at eventswhere the person would be, doing an activity to be closerto the person, asking friends about the person, and ask-ing friends to talk to the person (combined alpha = .82);(c) intimidation-related behaviors such as following the per-son, taking the person’s belongings, trying to manipulate theperson into dating you, and spying on the person (combinedalpha = .61); (d) mild aggression such as trying to scarethe person, making threats, threatening to hurt emotion-ally, threatening to damage belongings, threatening to hurtsomeone else, threatening to hurt oneself, verbally abus-ing the person, physically harming slightly, and physicallyharming more than slightly (combined alpha = .67).

Relationship development. Participants also respondedto one item, developed for this study, that assessed whatbest described what happened during the initial courtshipstage and afterward to determine whether or not a relation-ship began after these initial stages (1 = they had expressedinterest but it was not returned, 2 = the other expressedinterest in them but they were not interested, 3 = theyboth became interested and began a relationship, and 4 =other). For the purposes of analysis, a two-category vari-able was created with a “0” indicating a relationship did notdevelop, and a “1” that a relationship developed. Becausethe meaning of the response of “other” was unclear, partici-pants with an “other” response were excluded from analysis(n = 20). Participants also rated the level of seriousness oftheir relationship (1 = casual dating, 2 = serious dating, 3 =engaged to marry or living with your partner, 4 = married,and 5 = other). For the purposes of analysis, we collapsedthe categories such that a “0” indicates casual dating, anda “1” indicates that the relationship was more serious innature (i.e., serious dating, engaged or living together, mar-ried). Again, we omitted those with a response of “other”from analysis (n = 15). Finally, participants answered oneitem about the current status of that particular relationship(1 = broken up, 2 = considering breaking up, 3 = partnerconsidering breaking up, 4 = both considering breaking up,and 5 = still happily together). We collapsed the categoriesto signify whether the couple was still together (even if con-sidering breaking up) as “0” or whether they had broken upas “1.”

Relationship violence behaviors. The revised versionof the Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS2; Straus, Hamby,Boney-McCoy, & Sugarman, 1996) was used to assess thefrequency with which participants performed minor (e.g.,

252 WILLIAMS AND FRIEZE

slapped, threw something at the partner that could hurt)and severe (e.g., punched or hit partner with something thatcould hurt, used knife or gun) physically violent behaviorstoward the partner during their relationship. Participantsresponded to each item using a frequency scale to indicatehow many times during the last 6 months of their relation-ship they had performed the behaviors (1 = none, 2 = onetime, 3 = two or three times, 4 = 4 to 10 times, and 5 = morethan 10 times). Prior to scale construction, we analyzedthe individual items. Because these items had relativelylow frequencies, we took Straus’s (2004) recommendationand created a dichotomous variable of dating violence thatreflected no dating violence as “0” versus any dating vio-lence as “1.” We constructed separate dichotomous scoresfor mild violence and severe violence. The alpha for mildrelationship violence was .73 and for severe violence was.60.

RESULTS

General Description of Courtshipand Dating Relationships

Participants’ responses to questions regarding their rela-tionships revealed that all participants either had been ina relationship at some point in their lives or had been in-terested in someone or had someone interested in them.During the beginning stages of courtship, approximately50% of participants reported that there had been a mu-tual interest, while the other half indicated an imbalancein interest between them and their potential partners. Achi-square analysis indicated that men were relatively morelikely to report that they were more interested initially (26%of men vs. 14% of women), while women were more likelyto report that the partner was more interested initially (37%

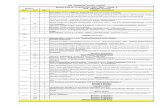

Table 1

Occurrence of Courtship Persistence, Relationship Violence, and Breakup Persistence

Total Sample Men WomenM (SE) M (SE) M (SE) F

Courtship (N = 300)Approach 2.76 (.76) 3.10 (.64) 2.63 (.77) 25.58∗∗∗Surveillance 2.26 (.71) 2.28 (.76) 2.25 (.69) .09Intimidation .34 (.48) .44 (.50) .31 (.46) 4.49∗Mild aggression .23 (.42) .27 (.45) .22 (.41) .92

Relationship (n = 237)Mild relationship violence .35 (.48) .23 (.42) .40 (.49) 6.59∗Severe relationship violence .11 (.32) .05 (.21) .14 (.35) 4.29∗

Breakup (n = 148)Approach 2.19 (.78) 2.32 (.76) 2.15 (.78) 1.34Surveillance 1.84 (.77) 1.63 (.67) 1.91 (.79) 3.93∗Intimidation .25 (.44) .26 (.44) .25 (.43) .01Mild aggression .30 (.46) .23 (.43) .32 (.47) 1.12

Note. Although the total sample size is N = 300, the sample representing relationship violence and breakup behaviors was reduced due to courtshipsdissolving and some relationships not breaking up. All initial scales ranged from 1 to 5 (with 5 being high). Because of skewness, scales for relationshipviolence, intimidation and mild aggression were dichotomized (1 = any, 0 = none).∗p < .05. ∗∗∗p < .001.

of women’s partners vs. 21% of men’s partners), χ2 (2,N = 300) = 10.49, p < .01. Overall, 79% of men and womenin the study had relationships develop out of these initialcourtships. Couples that had indicated a mutual initial in-terest were more likely to develop a formal couple relation-ship, χ2 (2, N = 280) = 29.18, p < .001. Relationships wereequally likely to develop for men and women regardless ofwho was more attracted. Of the total relationships that haddeveloped over time, the majority (72%) were describedas serious dating situations. Other data indicated that themajority (62%) of dating couples had already broken up atsome later point.

Courtship Persistence, Relationship Violence,and Breakup Persistence

Descriptive analysis of the courtship persistence behaviorsubscales indicated that the majority of men (100%) andwomen (99%) performed one or more approach behaviorsduring initial courtship. Similar findings were indicated forsurveillance behaviors (96% and 99%, respectively). Manymen (44%) and women (31%) performed intimidation-typebehaviors, and similar findings were found for mild aggres-sion behaviors (27% and 22%, respectively). Means for thefour types of expressions of initial interest are shown inTable 1. To examine potential gender differences in ini-tial courtship behaviors, a multivariate analysis of variance(MANOVA) was conducted using gender as the indepen-dent variable and the initial courtship behavior subscalesas dependent variables. The overall F was significant forgender, F(4, 295) = 8.65, p < .001. As shown, men reportedsignificantly more approach and intimidation behaviors atinitial courtship than women.

Descriptive analysis of the relationship violence scalesshowed that physical violence, particularly mild, was

Courtship and Persistence Behaviors 253

relatively frequent. Overall, 23% of men and 40% of womenreported engaging in one or more of the mild violenceitems, while 4% of men and 14% of women reported per-forming one or more severe violence items. Results of aMANOVA indicated the overall F was significant for gender,F(2, 234) = 3.82, p < .05. As shown in Table 1, women re-ported performing the mild and severe physically violentbehaviors more than men during the relationship.

Descriptive analysis of the breakup persistence behav-ior subscales revealed similar frequencies to those at initialcourtship. Of those who had broken up, the majority of men(97%) and women (94%) performed approach behaviorsduring the breakup. Surveillance behaviors also were com-mon (72% and 86%, respectively). Although intimidation(26% and 25%, respectively) and mild aggression behaviors(23% and 32%, respectively) were less common than otherbehaviors, they were still somewhat frequent. Means for thefour types of expressions at breakup are shown in Table 1.Potential gender differences in breakup persistence behav-iors were examined using a MANOVA, with gender as theindependent variable and the breakup subscales as depen-dent variables. The overall F for gender was significant,F(4, 143) = 3.58, p < .01. As shown, women performedmore surveillance behaviors at breakup than men.

Initial Interest, Courtship Behaviors,and Relationship Development

To test the first hypothesis, that a one-sided initial in-terest would predict courtship persistence behaviors, weconducted a series of regression analyses with the threedichotomous initial interest variables, gender, and theirinteractions as independent variables and the four initialcourtship behaviors as dependent variables. Because ap-proach and surveillance behaviors were on a continuousscale, we conducted linear multiple regression. For the di-chotomous outcomes of intimidation and mild aggression,we conducted logistic regression. As shown in Table 2, re-sults revealed that one-sided initial courtship interest inwhich participants were more interested than the part-ner was significantly and positively related to performingsurveillance behaviors during courtship. In addition, mutualattraction was linked with performing approach as well as

Table 2

Results of Regression Models of Initial Courtship Interest Predicting Courtship Persistence Behaviors

Approach Surveillance Intimidation Mild Aggression

b (SE) β b (SE) β b (SE) Odds b (SE) Odds

Initial interest (self) .03 (.13) .01 .36∗∗ (.12) .19 .50 (.36) 1.66 .36 (.42) 1.44Initial interest (mutual) .23∗ (.10) .15 .29∗∗ (.09) .20 .06 (.28) 1.06 .41 (.32) 1.51Gender −.46∗∗∗ (.10) −.27 .03 (.09) .02 −.49 (.27) .61 −.23 (.30) .80

R2 = .10 R2 = .04 R2 = .03 R2 = .01

Note. N = 300. The reference group for initial interest is a one-sided courtship in which the potential partner is more initially interested. For logisticmodels we used the Nagelkerke2 fit index to represent R2 .∗p < .05. ∗∗p < .01. ∗∗∗p < .001.

surveillance behaviors. Finally, there was a significant ef-fect of gender for courtship behaviors; in further support ofour preliminary analyses, men performed more approachbehaviors than women. Because the interactions of initialinterest and gender were not statistically significant, theirresults are not reported in Table 2.

The second hypothesis predicted that relationships withsome form of initial courtship persistence would be morelikely to develop into serious dating relationships than ini-tial contacts not involving these behaviors. To test this hy-pothesis, we conducted a logistic regression analysis withthe four initial courtship behavior subscales, gender, andtheir interactions as independent variables and courtshipresult as the dependent variable. Results, summarized inTable 3, showed that relationships were three times morelikely to evolve from courtships when approach behaviorswere present, but less likely to develop when surveillanceand intimidation occurred during courtship. In addition,women’s relationships were two times more likely to de-velop than men’s. Because the interactions of persistencebehaviors and gender were not statistically significant, theirresults are not reported in Table 3.

Association of Courtship, Relationship,and Breakup BehaviorsWe next tested the third hypothesis, that initial courtshippersistence behaviors would predict violence during the re-lationship, by conducting a logistic regression analysis withthe four initial persistence behavior subscales, gender, andtheir interactions as independent variables and mild and se-vere relationship violence as dependent variables. As shownin Table 3, results revealed that mild relationship violencewas approximately five times more likely to occur and severeviolence was 3.5 times more likely to occur when there hadbeen initial mild aggression persistence during courtship.Consistent with descriptive analyses revealing higher fre-quency of violence by women, results showed that womenwere two times more likely than men to perform mildly vio-lent actions and almost four times more likely to perform se-vere violence (although only marginally significant) duringthe relationship. Because the interactions of persistencebehaviors and gender were not statistically significant, theirresults are not reported in Table 3.

254 WILLIAMS AND FRIEZE

Table 3

Results of Regression Models of Initial Courtship Behaviors and Gender Predicting Courtship Resultand Relationship Violence

Mild Relationship Violence Severe Relationship ViolenceCourtship Result (n = 237) (n = 237)

b SE Odds b SE Odds b SE Odds

Approach 1.09∗∗∗ (.30) 2.99 −.41 (.23) .66 −.48 (.35) .62Surveillance −.60∗ (.30) .55 .02 (.26) 1.02 .27 (.38) 1.31Intimidation −.81∗ (.40) .44 .00 (.37) 1.00 .54 (.52) 1.72Minor Aggression .25 (.44) 1.29 1.68∗∗∗ (.38) 5.35 1.26∗∗ (.48) 3.53Gender .82∗ (.40) 2.27 .84∗ (.38) 2.30 1.28+ (.66) 3.61

R2 = .12 R2 = .18 R2 = .15

Note. For logistic models we used the Nagelkerke2 fit index to represent R2 .+p = .053. ∗p < .05. ∗∗p < .01. ∗∗∗p < .001.

To test our fourth and final hypothesis that initialcourtship stalking would predict persistence behaviors atbreakup, we conducted a series of regression analyses ofthe four initial courtship behavior subscales, gender, andtheir interactions as independent variables and their com-parable breakup subscales as dependent variables. In theseanalyses, we also included relationship violence as inde-pendent variables due to the potential relation betweensuch violence and persistence behaviors. Because approachand surveillance breakup behaviors were on a continuousscale, we conducted linear multiple regression. For thedichotomous outcomes of breakup intimidation and mildaggression, we conducted logistic regression. The results(summarized in Table 4) revealed, with only one excep-tion, that persistence behaviors performed during courtshipwere consistently related to performing those same behav-iors at breakup. Specifically, initial approach and surveil-lance behaviors were significantly and positively relatedto performing these behaviors at breakup. Breakup mild

Table 4

Results of Regression Models of Courtship Behaviors, Relationship Violence, and Gender PredictingBreakup Persistence

Breakup MinorBreakup Approach Breakup Surveillance Breakup Intimidation Aggression

b SE β b SE β b SE Odds b SE Odds

Approach .30∗∗ (.10) .28 −.04 (.09) −.04 −.05 (.38) .95 −.42 (.36) .66Surveillance .28∗∗ (.10) .25 .61∗∗∗ (.09) .55 .72 (.40) 2.06 .32 (.36) 1.38Intimidation −.09 (.15) −.05 .09 (.13) .06 .86 (.52) 2.37 −.47 (.54) .62Minor Aggression −.21 (.15) −.12 −.30∗ (.14) −.17 −.99 (.55) .37 1.34∗∗ (.51) 3.82Mild Relationship Violence .20 (.14) .12 .42∗∗ (.12) .26 1.85∗∗∗ (.49) 6.34 1.43∗∗ (.45) 4.20Severe Relationship Violence −.05 (.21) −.02 −.20 (.18) −.09 .45 (.66) 1.57 .78 (.65) 2.19Gender −.04 (.15) −.02 .21 (.13) .12 −.40 (.55) .54 −.18 (.53) .84

R2 = .20 R2 = .38 R2 = .28 R2 = .31

Note. N = 148. For logistic models we used the Nagelkerke2 fit index to represent R2 .∗p < .05. ∗∗p < .01. ∗∗∗p < .001.

aggression was four times more likely to occur if such ag-gression had been present at courtship. The one excep-tion was that courtship intimidation did not significantlypredict breakup intimidation. Additional findings revealedthat initial surveillance behaviors were positively relatedto approach behaviors at breakup. Further, although wedid not hypothesize an association between relationshipviolence and breakup persistence, we nevertheless foundthat mild relationship violence was positively related tosurveillance behaviors at breakup and to an increased like-lihood of performing intimidation and mild aggression atbreakup (approximately six and four times greater likeli-hood, respectively).

DISCUSSION

This study extended past research by addressing the ques-tion of how persistence and violence behaviors at early andlater stages of dating relationships are related and if the

Courtship and Persistence Behaviors 255

same patterns of relations exist for women and men. Morespecifically, we looked at the behaviors of approach, surveil-lance, intimidation, and mild aggression used by female andmale college students to express initial romantic interest,how these behaviors related to mild and severe physicalviolence during the relationship, and their relationship topersistence behaviors at relationship breakup. In addition,we examined this courtship persistence in relation to initialrelationship interest, that is, whether the initial interest wasone-sided or mutual, and to later relationship development.An overarching goal of this study was to better understandthe role of gender in the links between early and later datingbehaviors.

In line with our main predictions, the present study pro-vided strong evidence that persistence behaviors and vio-lence performed at differing points in a dating relationshipare indeed related. Our study, as with past studies (e.g.,Emerson et al., 1998; Sinclair & Frieze, 2002), showedthat persistence behaviors were quite common occurrencesduring early courtship, a finding not particularly surpris-ing due to general dating scripts themselves involving theidea of persistence (e.g., Rose & Frieze, 1993). More im-portant, our results showed that some early forms of per-sistence are related to future violence and persistence (orattempts to reestablish the relationship during breakup).Specifically, mild aggression during courtship was associ-ated with a greater likelihood of performing violence duringthe relationship. Further, courtship persistence behaviorswere significantly related to identical behaviors at breakup,with the exception of intimidation, implying a consistencyin the types of behaviors performed when initiating andending dating relationships. Taken together, these find-ings indicate that early behaviors may foreshadow behav-iors during later stages in the relationships, which supportsmore general findings of prior research on the continuity ofphysical aggressiveness in relationships (e.g., Schumaker &Leonard, 2005) and extends this continuity to include morebenign persistence behaviors performed during courtship.

Additional findings of this study suggested that particularcharacteristics of early courtships, such as level of initial in-terest, may predict specific courtship persistence behaviors.We examined initial courtship interest as a way of tappingthe asymmetry between two parties in their relationshipexpectations (or lack thereof). This asymmetry in initial in-terest has been the focus of the work on unrequited love andstalking-type behaviors. We found that both genders actedin indirect ways, such as using spying-type techniques, toindicate interest when faced with an asymmetric attraction.The choice of indirect methods may serve a self-protectivefunction when individuals are aware of the asymmetry inattraction. Thus, choice of courtship persistence behaviorsmay be better understood by considering contextual char-acteristics, such as initial courtship attraction and whethersuch interest is asymmetric or mutual.

Results revealed that the majority (79%) of reportedcourtships developed into dating relationships, but initial

courtship behavior did affect this finding. Statisticallyspeaking, courtships were more likely to develop into dat-ing relationships when initial approach behaviors were per-formed and less likely to develop when surveillance andintimidation behaviors were present. Although we had ex-pected all types of persistence behaviors to be positivelyassociated with relationship development, only initial ap-proach behaviors predicted the establishment of a relation-ship. However, the fact that dating relationships ensued inmost cases implies that persistence behaviors are often notseen as threatening and that relationships develop despitetheir presence. Future research should establish the inter-pretation by the recipient of particular persistence behav-iors during dating to more fully understand why so manyrelationships develop out of these courtships. It may bethat the context in which behaviors are performed (i.e.,courtship vs. breakup) determines whether or not more orless insidious behaviors become a nuisance to recipients orlead to fear or unease. Overall, it appears that characteris-tics of early courtships, such as initial romantic interest andinitial courtship behavior, may provide insight into futurebehavior and relationship development.

We also sought to better understand the role of genderin both the frequency with which persistence and violencebehaviors were reported and in the relations between earlyand later behaviors. Men and women in our study showeddifferences in their use of particular behaviors during thecourse of dating. Findings revealed that men reported moreinitial approach and intimidation behaviors than women butwomen reported engaging in more relationship violencethan men, although much of this violence was at a verylow level. These differences replicate those found in paststudies on gender differences in stalking and relationshipviolence (e.g., Sinclair & Frieze, 2002; Archer, 2000, re-spectively). However, no gender differences in the relationsbetween early and later behaviors emerged in the presentstudy. That is, both men’s and women’s initial behaviorswere significantly related to behaviors during the relation-ship and at breakup. This presence of gender differencesin the frequency of particular behaviors and the absence ofgender differences in their relations with future behaviorshighlights the need for more research on women’s receiptof violence and persistence from male partners, as well astheir perpetration of such behaviors.

Several implications for future research and advocacy inthe area of dating persistence and violence can be drawnfrom the general pattern of findings for both men andwomen. Overall, this study suggests that early behaviorsmay foreshadow potentially violent and aggressively persis-tent behaviors in the future relationship. This continuity ofpersistence and violence over the course of dating relation-ships may be better understood when one considers that it isduring the earliest stages of relationships when acceptabilityof violence is established (Billingham, 1987). The develop-ment of full-fledged dating relationships despite the pres-ence of persistence behaviors during courtship may in fact

256 WILLIAMS AND FRIEZE

reward persistence behaviors, deeming them acceptable foruse during later stages of the relationship. When threatenedwith the demise of a romantic relationship, men and womenseem to perform the behaviors at breakup that had demon-strated “success” during courtship (i.e., behaviors that at-tracted the other partner) in an attempt to reestablish thedating relationship. These ideas regarding the evolution ofviolence and stalking-type behaviors need systematic test-ing in future research. Based on these ideas and the findingsof the present study, intervening during the courtship pro-cess when particular persistence behaviors may be presentbut before high levels of intimacy are attained seems tobe the most obvious avenue for violence prevention efforts(Sinclair & Frieze, 2002). This suggestion appears to be ap-propriate for both men and women. Although gender differ-ences emerged in the frequency of behaviors, the relationsbetween early and later behaviors were not significantly dif-ferent for men and women. These results suggest that bothmen and women should be informed about the potentialharm of accepting or normalizing persistence behaviors asa part of courtship.

Limitations

There are several caveats of the present study. First, thestudy sample is neither representative of all college stu-dents nor of all college dating relationships. The sampleincludes only a small proportion of males. In addition, itis possible that the study procedure could have created abias in the specific relationships that participants reported.Participants self-selected to participate in the study, whichwas entitled “Loving When Your Partner Doesn’t LoveBack,” and were instructed to report on their longest dat-ing relationship, which may have increased the numbersof “successful” courtships reported. Given that most of thecourtships developed into dating relationships, this bias islikely. However, our results showed that courtships that hadentailed initial surveillance and intimidation behaviors wereless likely to develop into dating relationships than thosethat had not included such behavior. Thus, it is difficultto know the precise extent of selection bias. Nevertheless,these sampling-related issues may limit the findings andimplications drawn.

Initial submission: September 16, 2004Initial acceptance: March 22, 2005Final acceptance: May 11, 2005

REFERENCES

Archer, J. (2000). Sex differences in aggression between heterosex-ual partners: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin,126, 651–680.

Baumeister, R. F., Wotman, S. R., & Stillwell, A. M. (1993). Unre-quited love: On heartbreak, anger, guilt, scriptlessness andhumiliation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,64, 377–394.

Billingham, R. E. (1987). Courtship violence: The patterns of con-flict resolution strategies across seven levels of emotionalcommitment. Family Relations: Journal of Applied Family& Child Studies, 36, 283–289.

Coleman, F. L. (1997). Stalking behavior and the cycle of do-mestic violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 12, 420–432.

Davis, K., & Frieze, I. H. (2002). Research on stalking: What dowe know and where do we go? In K. E. Davis & I. H. Frieze(Eds.), Stalking: Perspectives on victims and perpetrators(pp. 353–375). New York: Springer.

Emerson, R. M., Ferris, K. O., & Gardner, C. B. (1998). On beingstalked. Social Problems, 45, 289–314.

Frieze, I. H. (2000). Violence in close relationships–developmentof a research area: Comment on Archer (2000). Psycholog-ical Bulletin, 126, 681–684.

Hall, D. M. (1998). The victims of stalking. In J. R. Meloy (Ed.),The psychology of stalking (pp. 115–136). San Diego, CA:Academic Press.

Langhinrichsen-Rohling, J., Palarea, R. E., Cohen, J., & Rohling,M. L. (2002). Breaking up is hard to do: Pursuit behaviorsfollowing the dissolution of romantic relationships. In K. E.Davis & I. H. Frieze (Eds.), Stalking: Perspectives on vic-tims and perpetrators (pp. 212–236). New York: Springer.

Lloyd, S. A. (1991). The dark side of courtship: Violence and sexualexploitation. Family Relations, Interdisciplinary Journal ofApplied Family Studies, 40, 14–20.

Makepeace, J. M. (1986). Gender differences in courtship violencevictimization. Family Relations: Journal of Applied Family& Child Studies, 35, 383–388.

Rodgers, D. T. (1978). The work ethic in industrial America: 1850–1920. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Rose, S., & Frieze, I. H. (1993). Young singles’ contemporarydating scripts. Sex Roles, 28, 499–509.

Schumaker, J. A., & Leonard, K. E. (2005). Husbands’ and wives’marital adjustment, verbal aggression, and physical aggres-sion as longitudinal predictors of physical aggression in earlymarriage. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology,73, 28–37.

Sinclair, H. C., & Frieze, I. H. (2002). Initial courtship be-havior and stalking: How should we draw the line? InK. E. Davis & I. H. Frieze (Eds.), Stalking: Perspectiveson victims and perpetrators (pp. 186–211). New York:Springer.

Spitzberg, B. H., & Cupach, W. R. (2003). What mad pur-suit? Obsessive relational intrusion and stalking relatedphenomena. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 8, 345–375.

Straus, M. A. (2004, July). Scoring the CTS2 and CTSPC.Retrieved March 21, 2005 from http://pubpages.unh.edu/∼mas2/CTS28a3.pdf

Straus, M. A., Gelles, R. J., & Steinmetz, S. K. (1980). Behindclosed doors: Violence in the American family. New York:Anchor.

Straus, M. A., Hamby, S. L., Boney-McCoy, S., & Sugarman, D.B. (1996). The revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2): De-velopment and preliminary psychometric data. Journal ofFamily Issues, 17, 283–316.

Tjaden, P., & Thoennes, N. (1998). Stalking in America: Findingsfrom the National Violence Against Women Survey. Wash-ington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice.

Courtship and Persistence Behaviors 257

Tjaden, P., & Thoennes, N. (2002). The role of stalking in domesticviolence crime reports generated by the Colorado SpringsPolice Department. In K. E. Davis & I. H. Frieze (Eds.),Stalking: Perspectives on victims and perpetrators (pp. 330–350). New York: Springer.

Tjaden, P., Thoennes, N., & Allison, C. J. (2002). Comparing stalk-ing victimization from legal and victim perspectives. In K.

E. Davis & I. H. Frieze (Eds.), Stalking: Perspectives onvictims and perpetrators (pp. 9–30). New York: Springer.

White, J., Kowalski, R. M., Lyndon, A., & Valentine, S. (2002). Anintegrative contextual developmental model of male stalk-ing. In K. E. Davis & I. H. Frieze (Eds.), Stalking: Perspec-tives on victims and perpetrators (pp. 163–185). New York:Springer.