The Ecological Validity of Photographic Slides and ...

-

Upload

khangminh22 -

Category

Documents

-

view

1 -

download

0

Transcript of The Ecological Validity of Photographic Slides and ...

The Ecological Validity of Photographic Slides and Videotapes in Simulating the Service Setting

JOHN E. G. BATESON MICHAEL K. HUI*

In the study of consumers' evaluation of the service setting, laboratory experiments using environmental simulations provide researchers with a level of control that can otherwise be difficult to achieve in field studies. This article demonstrates that photographic slides and videotapes, used as environmental simulations in testing a theory of crowding, have ecological validity. The same theoretical model is tested with data obtained from a field quasi-experimental study and with data from a laboratory study that used photographic slides and videotapes to simulate the service setting. Conditions that may constrain the applications of various kinds of environmental simulations in consumer research on services are also discussed.

T here is a general consensus that services can be viewed as the output of an interactive process in

which the consumer is an active or passive participant (Langeard et al. 1981). It is from the interpersonal (consumer and contact personnel) and person-environment (consumer and physical service setting) interactions that consumers attempt to get their needs and wants satisfied. We draw the distinction here between the service experience, which is defined as the consumer's emotional and behavioral responses to his/her interaction with the service setting and personnel, and the service encounter, which is commonly defined as the dyadic interaction between the consumer and the server (Czepiel, Solomon, and Surprenant 1985).

A growing number of researchers have become interested in understanding the service experience. Alternative theories have emerged to explain the experience (see, e.g., Bitner 1990; Czepiel et al. 1985). Researching the service experience, however, poses a key methodological issue. It has long been argued within operations management that it is virtually impossible to standardize the service experience (Chase and Tansik 1983). The high people content of the process, involving both service personnel and consumers, introduces too

* John E. G. Bateson is senior vice president, MAC-Gemini, 22 Grafton Street, London WIX 3LD, England. Michael K. Hui is assistant professor of marketing, Concordia University, 1455 de Maisonneuve Blvd. West, Montreal, Quebec H3G 1M8, Canada. Both authors contributed equally to this article and they are listed alphabetically. The authors are indebted to the editor and the three anonymous reviewers, who provided detailed and constructive comments on this article.

271

much uncertainty. The variability in mood of all parties and the frailty of operating systems both compound this problem. For services, unlike the situation for goods, it is impossible to remove this variability in the "manufacturing" process before it reaches the consumer. Because services are real-time experiences, quality control cannot occur at the "factory gate."

Under such circumstances, testing theories in actual service settings poses real problems because each respondent may have a different set of interactions. The noise that is introduced into the results in this manner may preclude the accurate assessment of the impact of different features and events and, hence, the theory testing. One possible solution is to measure the potential confounding variables and control statistically their effects on the dependent variables (Cook and Campbell 1979). Given the current level of understanding and the complex nature of the interaction between the consumer and the service setting, this alternative may require an extremely large sample size to produce any significant, systematic effects.

At first sight, laboratory experiments would seem to be ideally suited to researching the service experience, especially when one's objective is theory testing (Calder, Phillips, and Tybout 1981). Experimental design offers high levels of control and the ability to manipulate variables individually. However, laboratory experiments should be conducted only when (a) researchers can effectively create realistic service settings in a laboratory and (b) the simulated service setting can produce the same experience as the actual service setting. In environmental psychology, a similar set of arguments has been made and labeled as "ecological validity"

© 1992 by JOURNAL OF CONSUMER RESEARCH, Inc .• Vol. 19. September 1992 All rights reserved. 0093·5301/93/1902.()()()9$2.00

by guest on September 12, 2016

http://jcr.oxfordjournals.org/D

ownloaded from

272

(McKechnie 1977). Theorists in this field have long realized that the determination of the "media of representation," that is, how an environment should be presented to respondents, is one of the key methodological considerations in the study of person-environment interactions (Craik 1971).

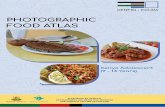

This article reviews the various types of environmental simulations and discusses the advantages of using this technique to test theories of the service experience. We also report the findings of a study that examines whether photographic slides and videotapes can adequately represent a simple service setting (a railway-station ticket office) in testing a theoretical model concerning the effects of consumer density (the number of consumers that are present in the setting) on the service experience. The theoretical model is first tested in a laboratory experiment using slides and videotapes as environmental simulations. The ecological validity of the instruments is then determined by comparing these results with those obtained from a field quasi experiment designed to test the same theoretical model. Conditions that may constrain the applications and ecological validity of various kinds of environmental simulations in consumer research on- services are also discussed.

ENVIRONMENTAL SIMULATIONS A common methodological problem facing environ

mental psychologists is the need to investigate human responses to environments that have not yet been built (Bosselmann and Craik 1987; Hershberger and Cass 1974). For instance, a hospital may want to know the reactions of their patients toward the design of a new casualty ward before it is built so that they can modify their plan if necessary. The best means by which to examine responses is to bring respondents to the actual setting, but this approach is obviously unfeasible because the setting does not yet exist. To overcome this difficulty, environmental simulations have been extensively employed "for replicating-or more precisely, previewing or otherwise anticipating-in the laboratory everyday environments that have not yet been built, modified, or otherwise actualized" (McKechnie 1977, p. 1(9).

McKechnie (1977) has suggested that environmental simulations can be classified according to two different dimensions. The first dimension refers to the fact that the information provided can be either perceptual or conceptual. Perceptual simulations are "concrete replicas or isomorphs or environments" (McKechnie 1977, p. 174), and they are intended to portray as much as possible the noticeable features of the actual environment. Examples of perceptual simulations include photographic slides and videotapes. By contrast, there are simulations such as maps and floor plans that convey primarily functional and operational information (e.g., a highway network), which is usually difficult for

JOURNAL OF CONSUMER RESEARCH

a person to visualize, even when s/he is in the realworld setting.

The second dimension delineates dynamic (e.g., videotapes and film produced from scale models of places) I or static (e.g., photographs) simulations. Static simulations portray only a single, unchanging description (static-conceptual) or view (static-perceptual) ofthe environment. On the other hand, dynamic simulations allow continuously changing descriptions (dynamicconceptual) or views (dynamic-perceptual) of the environment. For example, an architectural model of hospital premises was made in a study that determined where a new entrance to the parking deck of a hospital should be built (Carpman, Grant, and Simmons 1985). A videotape was produced by moving a specially adapted videocamera around the model. The videotape, when shown on a monitor, gave images as if one were driving toward the parking deck. Respondents, while watching the videotape, were asked a number of questions regarding the parking deck.

Environmental simulations not only resolve the methodological difficulty in predicting human responses to "not yet existing" environments, they also provide a number of other advantages. First, it becomes possible to study person-environment interactions in laboratory settings, and this allows researchers to exert tighter control on any possible confounding variables (McKechnie 1977). Second, environmental simulations increase the cost-effectiveness of person-environment research (Eroglu and Machleit 1990; Surprenant and Solomon 1987). For example, it took only two weeks to complete the hospital parking-deck study mentioned earlier, even though the responses of a large number of respondents were processed. Last, researchers may also study human reactions to some potentially dangerous or unpleasant environments. Without environmental simulations, these types of studies might raise serious ethical concerns.

Three types of simulations-written descriptions or scenarios, audio simulations, and photographic slides and pictures-have been used in consumer research on services. Written scenarios and audio simulations are used primarily to manipulate various social and situational features of the service encounter. Researchers have used written scenarios to study how the explanations that contact personnel provide affect consumers' reactions to service failure (Bitner 1990). Researchers have also used audio simulations, in the form of a taped transaction, to manipulate service personalization (Surprenant and Solomon 1987). Photographic slides and pictures, on the other hand, are employed primarily to study consumers' reactions to the physical features of the retail or service setting (Bitner 1990; Eroglu and

'The technique originates from the Berkeley Environmental Simulation Laboratory at the University of California, Berkeley. A more detailed description of the technique and the laboratory can be found in McKechnie (1977) and Bosselmann and Craik (1987).

by guest on September 12, 2016

http://jcr.oxfordjournals.org/D

ownloaded from

ECOLOGICAL VALIDITY

Machleit 1990; Hui and Bateson 1991). The employment of these visual simulations allows researchers to manipulate environmental features such as consumer density (i.e., the number of consumers in a service setting; see H ui and Bateson 1991).

Drawing from the field of visual sociology (e.g., Becker 1981), researchers also rely heavily on various audiovisual tools in the naturalistic inquiry of consumer behavior (e.g., Belk, Sherry, and Wallendorf 1988). However, these tools are no longer used as environmental simulations. In these studies, pictures, slides, and videotapes are treated as raw data (Wallendorf and Arnould 1988) and are used to explore and investigate the sociocultural aspects of consumption behavior.

ECOLOGICAL VALIDITY

The use of environmental simulations, however, is justified only when they can adequately represent the environments (Craik 1971). Ecological validity, as defined by McKechnie (1977, p. 169), refers to "the applicability of the results oflaboratory analogues to nonlaboratory, real life settings." The development and validation of environmental simulations are important for the rapprochement of internal and external validity. Researchers should pay particular attention to factors that may influence the ecological validity of the various types of environmental simulations. For example, under what conditions can the use of slides and videotapes as environmental simulations be considered as appropriate and demonstrate sufficient ecological validity? When environmental simulations of high ecological validity are employed, laboratory experiments can be performed with reasonable internal and external validity.

In reviewing the whole area of ecological validity research, Bosselmann and Craik (1987) have reported substantial congruence between direct and simulation presentations. Perhaps the most complete test of validity was the study conducted by Hershberger and Cass (1974) to compare the ecological validity offive different representative media: 35-mm single-color slides, 35-mm multiple-color slides, super-8-mm color film, super-8-mm black-and-white film, and black-and-white videotape. One hundred and twenty architectural students were randomly divided into six equally sized groups. One respondent group was brought to 12 prototypical housing examples and was asked to evaluate the houses on 30 semantic differential items, which primarily captured the respondents' perceptual and emotional responses. Each of the other five respondent groups was asked to evaluate the same 12 housing examples, but this time they were exposed to one of the five environmental simulations. Results of the study indicated that item ratings obtained from the real-environment group and the five environmental simulation groups were highly correlated, ranging from. 72 for color film to .79 for color slides.

273

However, in environmental psychology, the primary interest is not in testing theories but in measuring reactions. The typical measures used include descriptiveevaluative dimensions, free descriptions, evaluative judgments, behavioral intentions, and judgments of objecti ve properties. None of the studies performed to date have attempted to examine whether a theoretical relationship can be tested just as well with simulation presentations as with actual settings. Given the fact that such simulations are becoming more common in theory testing in consumer research, especially in the study of consumer reactions to the retail or service setting, it is essential to test the ecological validity of these tools before they can be used legitimately and before their utility in consumer research can be fully exploited.

AN EMPIRICAL STUDY

The purpose of this study is to test the ecological validity of two kinds of visual environmental simulations, slides and videotapes, in testing theories related to interactions between the consumer and the service setting. The same theoretical model is tested in three different manners, using slides, videotapes, and a field quasi experiment. Slides are included because they have been one of the most widely employed environmental simulations in consumer research on services. The inclusion of videotapes allows us to test whether a slightly more dynamic representation of the service setting would produce different emotional and behavioral outcomes.2

The model was developed by Hui and Bateson (1991). It was selected because (a) one of the key exogenous variables of the model (consumer density, see our explanation later) is concerned with a physical dimension of the service setting and because (b) it is a model of reasonable complexity, so that the confirmation of the same model by three procedures would provide strong evidence for the ecological validity of the two types of environmental simulations in theory testing. Although the focus is on the ecological validity of slides and videotapes, it is necessary first to outline the model being tested.

As shown in Figure 1, the detailed model to be tested suggests that two variables will influence the consumer's perceived control, a crucial dimension underlying the service experience. The first is the availability of consumer choice or, more precisely, whether the consumer has an alternative means to acquire the service. This is rooted in Averill's (1973) categorization of the different

2McKechnie (1977) has suggested that the dynamic-static dimension in the classification of environmental simulations is a continuum. The videotapes used in this study, although not as dynamic as those produced by moving a videocamera around the real-world setting or a model of the setting, do show some motions and are therefore considered to be relatively more dynamic than slides.

by guest on September 12, 2016

http://jcr.oxfordjournals.org/D

ownloaded from

274 JOURNAL OF CONSUMER RESEARCH

FIGURE 1

THE HYPOTHESIZED MODEL

Consumer Choice

(~)

types of control, of which perceived choice is one. The second factor is the density of people within the service setting. Stokols (1972), in an attempt to reconcile conflicting experimental evidence on the impact of crowding on individual response, drew the distinction between density and crowding. Density refers to the physical condition, "in terms of spatial parameters" (Stokols 1972, p. 275). On the other hand, crowding is a psychological experience characterized by stress. It has been argued in the literature that the incidence of the psychological state of crowding is determined by the individual's perception of control in the setting (Schmidt and Keating 1979). The model hypothesizes that (a) density influences crowding both directly and indirectly through perceived control, hence testing the control theory of crowding, and (b) perceived control and crowding determine the consumer's emotional and behavioral responses to the service setting. A more detailed

E 7

description of the model can be found in Hui and Bateson (1991).

RESEARCH DESIGN Three different sets of data are necessary for testing

the ecological validity of slides and videotapes. The model just described must be tested using slides and videotapes to simulate the service setting. The model must also be tested in the actual service setting. Slides and videotapes can be judged to have ecological validity if the results obtained using them are similar to results obtained in the actual setting.

A Laboratory Study Using Slides and Videotapes

Consumer choice and consumer density were manipulated independently using photographic slides and

by guest on September 12, 2016

http://jcr.oxfordjournals.org/D

ownloaded from

ECOLOGICAL VALIDITY

written scenarios. In addition to slides, we also used videotapes to simulate the chosen service setting-the ticket office of a major railway station in London, England. The slides and videotapes were taken between 4 P.M. and 7 P.M. on two weekdays. This period covered the peak rush hour, and large variations in the number of people in the setting were, therefore, available. On the first day, a photo camera with a 24-mm lens was fixed at one corner of the ticket office. On the average, one picture was taken every four to five minutes, and a total of 35 usable slides were obtained. Because the slides were shot by the same camera from the same location, the only difference between them is the number of passengers present in front of the ticket office. On the second day, 25 90-second, silent video sequences were taken by a videocamera, fixed at the identical spot.

The number of consumers shown in each slide and in each video sequence was then counted. Because consumers were continuously entering and exiting from the setting, the number of consumers shown by a video sequence varied over the 90-second period. Hence, the mean number of consumers (over the beginning, the middle, and the end of the period) was used. The three slides that showed the highest, the average, and the lowest number of consumers were used to simulate the high, medium, and low consumer density settings, respectively. Pictures developed from the three slides are shown in Figure 2. Three video sequences that showed the same consumer density levels as the three slides did were also selected. The position for the camera, in each case, gave a view as if one were just entering the setting.

The subjects consisted of 123 individuals, recruited from passersby on the streets of a coastal city in the south of England. These subjects were then divided into 24 groups of five to six people. Respondents were asked to participate in a study of "individual responses to daily social situations" and were paid the equivalent of $15 each for their participation. Each group was randomly assigned to one of the slides or video sequences. Before the subjects watched the slide (on a screen) or the video sequence (on a 21-inch color monitor), they were asked to read a scenario that described a situation occurring at the ticket office. Half of the subjects within a group were given a high-choice scenario, while the other half were given a low-choice scenario.

The high-choice scenario was as follows: "It is 10 o'clock in the morning and Mr. Y is going by train to visit his friend. Tickets are sold in the railway station through the ticket office and through an automatic machine located next to the office. Mr. Y decides to buy the ticket from the ticket office. Of course, he can always change his mind and go for the machine. However, he sticks to his original decision throughout the process. The video/slide we are going to show you depicts the setting of the ticket office while Mr. Y is there."

The low-choice scenario was: "It is 10 o'clock in the morning and Mr. Y is going by train to visit his friend. Tickets are sold in the railway station through the ticket

275

office and through an automatic machine located next to the office. However, the machine only sells normal fare tickets. Since Mr. Y wants a cheap day return, he can only buy it from the ticket office. The slide/video we are going to show you depicts the setting ofthe ticket office while Mr. Y is there."

As revealed by the content of the scenarios, the highchoice consumer can use the machine to get his ticket and, therefore, staying in the ticket office is the consumer's own choice. On the other hand, the low-choice consumer does not have the alternative and must use the ticket office, whether he likes it or not. Finally, roletaking scenarios (using a hypothetical figure, Mr. Y) were used because they are more effective in inducing respondent involvement and are more commonly used in consumer research than role-playing scenarios are (Eroglu 1987).

After reading the scenario and viewing the slides or video, respondents completed a questionnaire that measured all the key dependent variables included in Figure 1. A total of 119 usable cases resulted (60 for slides and 59 for videotapes).

A Field Quasi-experimental Study Passengers were intercepted for interviews between

1 :30 P.M. and 7:00 P.M. on three weekdays, when they exited the same ticket office used in the slides and videotapes. Respondents were asked to complete a questionnaire regarding their experience in the ticket office. If, however, they were unable to participate because of time pressure, they were asked to complete the questionnaire on the train and mail it back to the researchers. Among the 92 useful cases, 19 of them were acquired through the latter mail method.

The number of people at the ticket office was recorded during the interview. This was categorized into three different levels and treated as an indicator of consumer density. As in the laboratory study, consumer choice is defined as whether a respondent could have used the ticket-vending machine in the station. However, in the field study, the variable was measured directly from the respondent rather than operationalized by experimental manipulations.

No significant difference in the gender of respondents was found across the three procedures: slides, videotapes, and field (X2 = 4.62, dj = 2, NS). This was particularly important because gender has been shown to influence reactions to crowding (see, e.g., Baum and Koman 1976). Minor but significant differences were found in age, education, and income level among the three groups.

Questionnaire The dependent variables were measured by the same

set of scales used in the laboratory and the field studies. Perceived control was measured with two different

by guest on September 12, 2016

http://jcr.oxfordjournals.org/D

ownloaded from

FIGURE 2

PICTURES REPRESENTING THE THREE LEVELS OF CONSUMER DENSITY

A. Low-Density Situation

B. Medium-Density Situation

by guest on September 12, 2016

http://jcr.oxfordjournals.org/D

ownloaded from

ECOLOGICAL VALIDITY 277

C. High-Density Situation

scales. The first (CTLl, a = .77) was a seven-point semantic differential scale consisting of six items selected from the "dominant" scale of Mehrabian and Russell (1974) and the "helplessness" scale of Glass and Singer (1972). Three of the nine items contained in the "dominant" and "helplessness" scales were excluded either because the item was inappropriate to the context of our study or because it had a negative contribution to the reliability (Cronbach's a) of the scale. The second perceived control scale (CTL2, a = .61) contained three seven-point Likert-type items ("I would feel that everything is under my control"; "I would feel it difficult to get my own way"; and "I would feel able to influence the way things were").

Perceived crowding was also measured by two different scales: (a) Bateson and Hui's (1987) semantic differential scale of perceived crowding (CRD1, a = .86) and (b) a three-item Likert-type scale (CRD2; a = .75; "I would not feel crowded"; "I would feel that there are too many people in the setting"; and "I would feel that there is no space for me in the setting"). Pleasure was measured with Mehrabian and Russell's (1974) semantic differential scale (PLE 1, a = .86). Respondents were also asked to evaluate the service experience (on a seven-point scale ranging from "not at all" to "extremely so") according to a list of 27 emotional terms. A second pleasure score (PLE2) was computed from

the respondents' ratings and the pleasure/displeasure value of each emotional term, determined by Bush's (1972) successive interval scales of adjectives denoting feelings. 3 Approach/avoidance was measured by asking respondents to report their degree of preference (PREF) for the situation (Mehrabian and Russell 1974). One additional question, "Could you have used the ticket machine for the service?" was added to the field-study questionnaire to operationalize self-reported consumer choice.

RESULTS The hypothesized relationships and the given mea

surement procedures can be represented by the structural equation model shown in Figure 1. In the laboratory setting, consumer density and consumer choice are experimentally manipulated variables, and, in the field setting, consumer density is operationalized by field observation and consumer choice is measured by a questionnaire item.

3The equation that we used in the computation was PLE2 = r.Ri · Pi, where Ri is the respondent's rating of the ith emotional term, and Pi is the pleasure or displeasure value of the ith emotional term, determined by the Bush (1972) successive interval scale.

by guest on September 12, 2016

http://jcr.oxfordjournals.org/D

ownloaded from

278 JOURNAL OF CONSUMER RESEARCH

TABLE 1

CORRELATION MATRICES OBTAINED FROM THE THREE PROCEDURES

CRDl CRD2 CTLl CTL2

Slides (n = 60): CRDl 1.000 CRD2 .710 1.000 CTLl -.582 -.592 1.000 CTL2 -.424 -.428 .666 1.000 PLEl -.656 -.597 .785 .460 PLE2 -.560 -.515 .659 .537 PREF -.657 -.517 .424 .338 Density -.449 .493 -.204 -.134 Choice -.201 -.118 .230 .071

Videotapes (n = 59): CRDl 1.000 CRD2 .729 1.000 CTLl -.710 -.569 1.000 CTL2 -.548 -.527 .714 1.000 PLEl -.699 -.623 .785 .607 PLE2 -.642 -.713 .700 .568 PREF -.517 -.384 .673 .524 Density .423 .423 -.332 -.255 Choice -.032 -.219 .319 .325

Field (n = 92): CRDl 1.000 CRD2 .655 1.000 CTLl -.440 -.372 1.000 CTL2 -.401 -.521 .417 1.000 PLEl -.577 -.624 .605 .488 PLE2 -.530 -.630 .536 .432 PREF -.465 -.446 .274 .312 Density .353 .311 -.173 -.181 Choice -.070 -.094 .076

Ecological validity requires a test of comparability; that is, the data obtained from the three different procedures should confirm or disconfirm the same theoretical model. Three different correlation matrices of all the independent and dependent variables, one from each of the three procedures (slides, videotapes, and field), were first computed (Table 1). Multigroup LISREL analysis was first used to test the equality of the three correlation matrices (Joreskog and Sorbom 1989, p. 256). The analysis produced a chi-square value of 96.58 with 90 df (p = .299). In other words, the hypothesis that the three correlation matrices are equal could not be rejected. Consistent with this result, when multigroup LISREL analysis was again used to test the hypothesized model, all the measurement and structural parameters were specified to be invariant across the three procedures. Despite the rigor of the constraints, the LISREL results indicate a reasonable fit. The model produced a chi-square value of 139.01 with 115 df(p = .063), and, as shown in Table 2 (the three-group analysis), all the estimated parameters were significant and in the direction hypothesized by Hui and Bateson (1991).

The three correlation matrices, when used separately to test the theoretical model, produced chi-square values of 35.86 (slide), 33.34 (videotape), and 32.98 (field), all

.146

PLEl PLE2 PREF Density Choice

1.000 .650 1.000 .637 .457 1.000

-.242 -.174 -.205 1.000 .371 .213 .272 .042 1.000

1.000 .698 1.000 .629 .622 1.000

-.378 -.328 -.358 1.000 .163 .236 .118 .042 1.000

1.000 .663 1.000 .611 .455 1.000

-.318 -.106 -.327 1.000 .122 .059 .105 -.097 1.000

of which had 25 df and indicated reasonable fit (p = .074, .123, and .131, respectively). The estimated values of the key measurement and structural parameters are given in Table 2. The magnitudes and signs are largely consistent across the three procedures. The only exception is that two parameters ({j31 and 1'22) obtained with the field data, although in the expected direction, are not significantly different from 0 at the .05 level (t-value = -1.21 and 1.00, respectively). Relaxing the equality constraint on these two parameters in the multigroup analysis, however, did not significantly improve the fit of the model. When the two parameters were allowed to vary under the field-procedure condition, the chi-square value was reduced by 3.55 but had 2 df less (chi-square difference test: X2 = 3.55, df = 2, NS).

DISCUSSION

Our findings suggested that the two environmental simulations, photographic slides and videotapes, that we used to simulate the service setting and to manipulate consumer density did evoke the same psychological and behavioral phenomena as the actual service setting did. The three different procedures supported the same theoretical model, and the hypothesis that they

by guest on September 12, 2016

http://jcr.oxfordjournals.org/D

ownloaded from

ECOLOGICAL VALIDITY 279

TABLE 2

ESTIMATES OBTAINED FROM SINGLE- AND MULTIGROUP LlSREL ANALYSIS

Parameters Slides Videotapes Field Three group

AYll 1.000 1.000 1.000 1.000 AY21 .967 (7.45) .919 (7.50) 1.059 (7.69) .977 (12.94) Ay32 1.000 1.000 1.000 1.000 AY42 .715 (5.91) .783 (7.24) .897 (5.00) .794 (9.74) Ay53 1.000 1.000 1.000 1.000 Ay63 .814 (6.92) .937 (7.96) .866 (8.55) .883 (13.57) Ay74 1.000 1.000 1.000 1.000 {312 -.584 (-5.25) -.657 (-5.80) -.862 (-3.95) -.689 (-8.20) {331 -.423 (-2.65) -.403 (-2.37) -.387 (-1.21)8 -.430 (-3.81) {332 .565 (3.63) .547 (3.36) .843 (1.97) .625 (4.97) {343 .725 (5.80) .825 (6.49) .716 (6.58) .750 (10.69) I'll .349 (3.99) .221 (2.40) .157 (1.79) .245 (4.68) 1'21 -.202 (-1.65) -.349 (-3.03) -.181 (-2.13) -.218 (-3.49) 1'22 .263 (2.15) .324 (2.82) .078 (1.00)8 .195 (3.20)

Goodness-of-fit index .882 .898 .929 .873 b

.860 e

.896d

Root mean square residual .059 .047 .047 .068 b

.088e

.082 d

x2 35.86 33.34 32.98 139.01 df 25 25 25 115 P .074 .123 .131 .063

NOTE.-Maximum likelihood estimates. For the sake of simplicity, only the estimated values of the Ay , f3, and "y parameters are presented. Numbers inside the parentheses are the t-values of the estimates. Estimates without a t-value are fixed parameters. A t-value beyond ±1.64 indicates that the parameter is significantly different from zero (one-tailed test).

a The t-value indicates that the parameter is not significantly different from zero (p > .10). b Value given is for slides. e Value given is for videotapes. d Value given is from field.

produced identical estimates for all the parameters could not be rejected. This finding is all the more powerful given the presence of some minor variations in the demographic characteristics (age, education, and income) between the three groups of respondents. Moreover, the nature of the questioning varied, with respondents being asked to project for another individual in the laboratory experiment and answering for themselves in the quasi-experimental study. As a result, we can claim that the findings obtained from using slides or videotapes have both internal and external validity, at least in this study. The large number of benefits that come from laboratory studies can thus be gained without apparently jeopardizing external generalizability.

The value of experimental control is actually shown in our findings. In the field study, when consumer choice was operationalized by a self-report measure, the relationship between consumer choice and perceived control (1'22), although in the expected direction, became nonsignificant. This finding is not unexpected because, in addition to choice, many other situational factors, such as waiting time, may also influence perceived control. Lack of experimental control also provides an alternative explanation to the insignificance of the relationship between perceived crowding and pleasure ({131).

In the field setting, pleasure may be influenced by many factors other than perceived crowding and perceived control (e.g., the friendliness of the ticket seller).

Limitations and Future Research To the extent that the results of this study are gen

eralizable to other settings and theories, the development and validation of environmental simulations can help to solve the often conflicting demands of internal and external validity in consumer research on services. A number oflimitations of this study do, however, need to be pointed out.

The variable manipulated in our study, consumer density, is one that readily lends itself to visual representation. Consumer density can be easily depicted by a static view of the service setting; hence, either the slides or videotapes, both of which were used largely as static-perceptual simulations in our study, are adequate to produce the expected effects of consumer density. A more rigorous test would depict true interactions between the consumer and the service setting or personnel. Under such situations, the ability of videotapes to capture movement from a number of angles might make it a more appropriate choice. Such an approach would,

by guest on September 12, 2016

http://jcr.oxfordjournals.org/D

ownloaded from

280

however, introduce an additional variable, in the form of the skill of the cameraman and/or editor. Replication of this type of study is clearly needed to test such propositions.

Static-perceptual simulations are also expected to be less effective than dynamic-perceptual simulations in representing large, complex service settings. For example, it will be difficult, if not impossible, to represent even a regular-sized supermarket with one or a few pictures. A videotape tour is likely to give the viewer a better understanding of the design and layout of the supermarket.

The two kinds of environmental simulations examined in this study convey only visual images and eliminate all other human sensory modes (Belk 1984). Research findings have suggested that a number of nonvisual cues, such as sound level and smell, will also influence human reactions to density (Eroglu and Harrell 1986). Nonvisual environmental simulations (e.g., sound could have been included in our videotapes) would be another logical direction for future research.

In short, slides and videotapes are appropriate and ecologically valid when (a) researchers want to manipulate one or a few visible dimensions of a simple service setting and (b) researchers are not interested in studying ongoing interactive behaviors between the consumer and the service setting. For example, the simulations can be used when one wants to study the consumer's psychological and behavioral reactions to a simple retail or service setting (e.g., Bitner 1990; Eroglu and Machleit 1990).

For interactive simulations, many advanced techniques, such as sequences of photomontages, videotapes produced from models, and computer-driven simulations, have been used in environmental psychology (McKechnie 1977). Any study that requires the presentation of actions and motions or requires that the decisions of the consumer be reflected in the subsequent images can benefit significantly from these kinds of simulations (see, e.g., Carpman et al. 1985; Winkel and Sasanoff 1976). In researching the service encounter, one can explore the possibility of simulating the interactions between the consumer and the contact personnel using the techniques mentioned above. These techniques can also be useful when researchers want to examine the movement of the consumer in a complex service setting, for example, studying the effects of consumer density and signs (Wener and Kaminoff 1983) on the movement of the consumer in a supermarket. The development and validation of these alternative visual simulation approaches deserve future attention from consumer researchers studying services.

Testing New Services

Simulations may also be useful in the development of new service offerings that are primarily experiential in nature. For many service firms, building a test outlet

JOURNAL OF CONSUMER RESEARCH

is a common practice in the development of new services. In fact, until recent times, service firms had little choice: this was the only alternative available. The employment of environmental simulations, such as photographs of mock-ups or models, should enable the consumer aspects of the setting to be improved without engendering the cost of building an outlet. Even if it is necessary to build a test outlet to perfect the operating procedures, the use of environmental simulations can still be valuable. For example, instead of having to build a number of outlets, the firm could produce simulations from a single test unit and obtain the same effects. The firm will then be able to test a new service nationally or even overseas without needing to build multiple test outlets. More research effort is essential to further explore the contribution that the various kinds of simulations can make to new services development. This may be a fruitful avenue to explore, because our findings suggest that these "pretests" could be generalizable to real settings.

[Received March 1991. Revised December 1991.]

REFERENCES Averill, James R. (1973), "Personal Control over Aversive

Stimuli and Its Relationship to Stress," Psychological Bulletin, 80 (4), 286-303.

Bateson, John E. G. and Michael K. Hui (1987), "A Model for Crowding in the Service Experience: Empirical Findings," in The Service Challenge: Integrating for Competitive Advantage, ed. John A. Czepiel et aI., Chicago: American Marketing Association, 85-90.

Baum, Andrew and Stuart Koman (1976), "Differential Response to Anticipated Crowding: Psychological Effects of Social and Spatial Density," Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 34 (3), 526-536.

Becker, Howard S. (1981), Exploring Society Photographically, Evanston, IL: Northwestern University.

Belk, Russell W. (1984), "Applications of Mood Inducement in Buyer Behavior," in Advances in Consumer Research, Vol. 11, ed. Thomas C. Kinnear, Provo, UT: Association for Consumer Research, 544-547.

---, John F. Sherry, Jr., and Melanie Wallendorf (1988), "A Naturalistic Inquiry into Buyer and Seller Behavior at a Swap Meet," Journal of Consumer Research, 14 (March), 449-470.

Bitner, Mary Jo (1990), "Evaluating Service Encounters: The Effects of Physical Surrounding and Employee Responses," Journal of Marketing, 54 (2), 69-82.

Bosselmann, Peter and Kenneth H. Craik (1987), "Perceptual Simulations of Environments," in Methods in Environmental and Behavioral Research, ed. Robert B. Bechtel et aI., New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 162-190.

Bush, Lynn E., II (1972), "Successive Intervals Scaling of Adjectives Denoting Feelings," JSAS Catalog of Selected Documents in Psychology, 2 (ms. no. 262), 140.

Calder, Bobby J., Lynn W. Phillips, and Alice M. Tybout (1981), "Designing Research for Applications," Journal of Consumer Research, 8 (September), 197-207.

by guest on September 12, 2016

http://jcr.oxfordjournals.org/D

ownloaded from

ECOLOGICAL VALIDITY

Carpman, Janet R., Myron A. Grant, and Deborah A. Simmons (1985), "Hospital Design and Wayfinding: A Video Simulation Study," Environment and Behavior, 17 (3), 296-314.

Chase, Richard B. and David A. Tansik (1983), "The Customer Contact Model for Organizational Design," Management Science, 29 (9), 1037-1050.

Cook, Thomas C. and Donald T. Campbell (1979), Quasi-Experimentation: Design & Analysis Issues/or Field Settings, Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Craik, Kenneth H. (1971), "The Assessment of Places," in Advances in Psychological Assessment, Vol. 2, ed. P. McReynolds, Palo Alto, CA: Science & Behavior.

Czepiel, John A., Michael R. Solomon, and Carol F. Surprenant (1985), The Services Encounter: Managing Employee/Customer Interaction in Service Businesses, Lexington, MA: Lexington.

Eroglu, Sevgin (1987), "The Scenario Method: A Theoretical, Not Theatrical, Approach," in 1987 AMA Educators' Proceedings, ed. Susan P. Douglas et aI., Chicago: American Marketing Association, 236.

--- and Gilbert D. Harrell (1986), "Retail Crowding: Theoretical and Strategic Implications," Journal o/Retailing, 62 (4), 347-363.

--- and Karen A. Machleit (1990), "An Empirical Study of Retail Crowding: Antecedents and Consequences," Journal 0/ Retailing, 66 (2), 201-221.

Glass, David C. and Jerome E. Singer (1972), Urban Stress: Experiments on Noise and Social Stressors, New York: Academic Press.

Hershberger, Robert G. and Robert C. Cass (1974), "Predicting User Responses to Building," in Man-Environment Interactions: Evaluations and Applications, Pt. 2, ed. D. H. Carson, Stroudsbury, PA: Dowden, Hutchinson & Ross, 117-134.

Hui, Michael K. and John E. G. Bateson (1991), "Perceived Control and the Effects of Crowding and Consumer Choice on the Service Experience," Journal o/Consumer Research, 18 (September), 174-184.

281

Joreskog, Karl G. and Dag Sorbom (1989), LISREL 7 User's Re/erence Guide, Mooresville, IN: Scientific Software.

Langeard, Eric, John E. G. Bateson, Christopher H. Lovelock, and Pierre Eiglier (1981), Services Marketing: New Insights/rom Consumers and Managers, Boston: Marketing Science.

McKechnie, George E. (1977), "Simulation Techniques in Environmental Psychology," in Perspectives on Environment and Behavior: Theory, Research and Applications, ed. Daniel Stokols, New York: Plenum, 169-189.

Mehrabian, Albert and James A. Russell (1974), An Approach to Environmental Psychology, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Schmidt, Donald E. and John P. Keating (1979), "Human Crowding and Personal Control: An Integration of Research," Psychological Bulletin, 86 (4), 680-700.

Stokols, Daniel (1972), "On the Distinction between Density and Crowding: Some Implications for Future Research," Psychological Review, 79 (3), 275-278.

Surprenant, Carol F. and Michael R. Solomon (1987), "Predictability and Personalization in the Service Encounter," Journal 0/ Marketing, 51 (April), 86-96.

Wallendorf, Melanie and Eric J. Arnould (1988), "'My Favorite Things': A Cross-cultural Inquiry into Object Attachment, Possessiveness, and Social Linkage," Journal o/Consumer Research, 14 (March), 531-547.

Wener, Richard E. and Robert D. Kaminoff (1983), "Improving Environmental Information: Effects of Signs on Perceived Crowding and Behavior," Environment and Behavior, 15 (1), 3-20.

Winkel, Gary H. and Robert Sasanoff (1976), "Analysis of Behaviors in Architectural Space," in Environmental Psychology: People and Their Physical Settings, 2d ed., ed. Harold M. Proshansky et aI., New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 351-363.

by guest on September 12, 2016

http://jcr.oxfordjournals.org/D

ownloaded from