The Construction of Normal Expectations

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

0 -

download

0

Transcript of The Construction of Normal Expectations

R E S E A R C H A N D A N A LYS I S

The Construction of NormalExpectationsConsumption Drivers for the DanishBathroom Boom

Maj-Britt Quitzau and Inge Røpke

Keywords:

normalitybathroomsustainable consumptionindustrial ecologysocial constructionlifestyle

Summary

The gradual upward changes of standards in normal everydaylife have significant environmental implications, and it is there-fore important to study how these changes come about. Theintention of the article is to analyze the social constructionof normal expectations through a case study. The case con-cerns the present boom in bathroom renovations in Denmark,which offers an excellent opportunity to study the interplaybetween a wide variety of consumption drivers and socialchanges pointing toward long-term changes of normal expec-tations regarding bathroom standards. The study is problem-oriented and transdisciplinary and draws on a wide range ofsociological, anthropological, and economic theories. The em-pirical basis comprises a combination of statistics, a reviewof magazine and media coverage, visits to exhibitions, andqualitative interviews. A variety of consumption drivers areidentified. Among the drivers are the increasing importanceof the home as a core identity project and a symbol of theunity of the family, the opportunities for creative work, theconvenience of more grooming capacity during the busy fam-ily’s rush hours, the perceived need for retreat and indulgencein a hectic everyday life, and the increased focus on body careand fitness. The contours of the emerging normal expectationsare outlined and discussed in an environmental perspective.

Address correspondence to:Maj-Britt QuitzauDepartment of Civil EngineeringTechnical University of DenmarkBrovej, Building 1182800 Kgs. Lyngby, [email protected]

c© 2008 by Yale UniversityDOI: 10.1111/j.1530-9290.2008.00017.x

Volume 12, Number 2

186 Journal of Industrial Ecology www.blackwellpublishing.com/jie

R E S E A R C H A N D A N A LYS I S

Introduction

Since the mid-1990s, the interest in consump-tion and environment has increased immensely.As part of this wave, the issue of consumptionhas made its way into the transdisciplinary andpartly overlapping fields of ecological economicsand industrial ecology (for overviews, see workby Reisch and Røpke [2004]; Hertwich [2005];Røpke [2005]; and Jackson 2006).1 The contri-butions to these fields span a variety of perspec-tives, from the measurement of environmentalimpacts of consumption to consumption driversand the questionable relationship between con-sumption and well-being. A particular perspec-tive focuses on the gradual changes of standardsin normal everyday life, the background for thesechanges, and their environmental implications(Shove 2003; Jackson [2005] related this to otherperspectives). The main point of this perspectiveis that much environmentally costly consump-tion is related to ordinary and routinized practicesthat are taken for granted and seldom consideredin an environmental perspective by either con-sumers or politicians. “Green” behavior is relatedto selected practices (the choice of labeled goods,etc.), and although the range of such practices isextending over time, they still constitute a minorpart of the consumption-related environmentalimpact. Therefore, it is important to take an in-terest in the long-term changes of daily life—thesocial construction of what is taken to be justthe normal standard that most people can expectto achieve. The importance of this issue is em-phasized by the current diffusion of the Westernlifestyle to the rapidly increasing group of “newconsumers” in Asia and elsewhere (Myers andKent 2004): When new standards are developedin the industrialized countries, there will be evenmore to aspire to.

The present article reports on a case studywithin this perspective of the social constructionof normality. We were inspired to take up thechange of bathroom standards, because in Den-mark we seem to be in the middle of a bath-room boom that offers an excellent opportunityto study the driving forces that point towardlong-term changes in normal expectations. Re-sponses to presentations of our preliminary resultsat conferences suggest that related trends can be

identified in many other industrialized countries,so we expect the findings to be quite generallyapplicable.

The environmental implications of bathroomarrangements and activities appear in relationto other issues in the environmental literature.Several studies have dealt with water usage andpossibilities for water savings in relation to toi-lets, in particular (e.g., Lazarova et al. 2003);other studies have dealt with the wastewater as-pect, including the handling of nutrients (Larsenet al. 2001; Magid et al. 2006); and life cycleassessment (LCA) studies have been carried outfor bathroom products (Takada et al. 1999; Xuand Galloway 2003). The trend toward increas-ing bathroom standards and the related environ-mental impacts does not seem to have attractedmuch interest, however. This is the gap that weintend to fill.

The increasing interest in bathroom improve-ments follows a longer period with much fo-cus on kitchen improvements. Since the mid-1980s, investments in refurbishing and renovat-ing kitchens have continued to be at a high level.Since the mid-1990s, bathrooms have attractedmore interest, with increasing investments in re-furbishing and renovating existing bathrooms aswell as installing more bathrooms in existingdwellings, codeveloping with a substantial in-crease in media coverage (Quitzau 2004; Institutefor Business Cycle Analysis 2005).2

Studies on kitchen renovations have demon-strated that renewals and aesthetic upgradinghave codeveloped with changes in the status andfunctions of the kitchen space—from being thehousewife’s workplace to being the social cen-ter of family life (Lupton and Miller 1992; Silva2000; Cieraad 2002; Hand and Shove 2004). Thedevelopment of a room thus reflects the interplaybetween broader social changes and the workingsof different consumption drivers. In this article,we intend to follow this interplay for the case ofthe bathroom. The main questions are as follows:

• Which consumption drivers are active inthis boom?

• Which social changes are reflected in thepresent changes of the bathroom?

• Can the contours of new normal expecta-tions be outlined?

Quitzau and Røpke, The Construction of Normal Expectations 187

R E S E A R C H A N D A N A LYS I S

• What are the environmental implicationsof the present changes?

The article covers a relatively short time pe-riod, mainly from the mid-1990s to the mid-2000s. We draw some lines back in history, but fora more elaborate analysis of the historical trans-formation of the bathroom from the late 19thcentury till today, we must refer readers to an-other article (Quitzau and Røpke forthcoming).Although the longer time perspective of that arti-cle calls for an explicitly coevolutionary approachinspired by social and historical studies on tech-nological change, the coevolutionary approachis more implicit in the present article, wherepresent consumption trends constitute the mainfocus and inspiration is drawn from consump-tion theories. We thus apply the term consump-tion drivers, but these should not be interpretedas factors mechanically leading to predeterminedoutcomes. The drivers are historically and situa-tionally specific, and the resulting consumptionpatterns emerge from the complex interplay of avariety of forces.

The article is structured as follows: In thesecond section, we introduce the backgroundby briefly describing renovation expenditures inkitchens and bathrooms. In the third section,we summarize the methodological basis of thestudy. The fourth section focuses on drivers be-hind housing renovations in general, whereas thefifth section addresses specific drivers in relationto bathrooms, including reflections on the so-cial changes that seem to influence the presentprocess. In the sixth section, the contours ofnormal expectations and environmental implica-tions are discussed, and the concluding remarksdeal with the possibilities for counteracting thedevelopment of an environmentally costly newnormality.

The Bathroom Boom

Danish housing standards are among the high-est in the world, with a living area of about55 square meters3 per person (calculations arebased on data from StatBank Denmark, 2006),and nearly all dwellings have their own toiletand bath/shower (Statistics Denmark 2001). Thehigh priority given to housing is reflected in the

distribution of household consumption: Housingconstituted 21% of consumption expenditures in2003, followed by transport and communication(14%) and food (11%; Bach et al. 2005).

Installation of new kitchens has constitutedan important part of renovation expendituresduring the last 20 years, and the accumulatedresult is that Danish households have installedaround 2 million new kitchens during this pe-riod (Institute for Business Cycle Analysis 2005).A market survey shows that the interest in hav-ing new kitchens has been high during the last10 years, as 1.1 million out of a total numberof 2.49 million households have installed newkitchens. This survey paints a bleak picture ofthe future, seen from a commercial point of view,as there will be no more old kitchens to replaceapproximately 6–7 years from now, if kitchen re-placements continue at the high rate of the last5 years. The survey provides some consolation,however, in the fact that fashions change quicklyand that some of the installed kitchens are soinexpensive that their economic life can be ex-pected to become shorter than the present aver-age of 19 years. The survey concluded,

It is a challenge for the trade to make surethat the media continue to focus on the homeand the kitchen. In this way, quicker replace-ments can be encouraged and the kitchentrade can maintain its turnover. (Institute forBusiness Cycle Analysis 2005, 49, our trans-lation)

The relative satiation with regard to kitchen re-placements may lead to increasing interest inbathroom renovations.

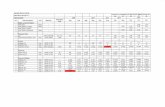

Since the mid-1990s, bathrooms have becomean increasingly important part of renovation ex-penditures, and current trends suggest that mucheffort and money are being invested in renewalof this specific room. According to a represen-tative poll carried out by Rassing and Thulstrup(2004), 5.2% of Danish households installed anew bathroom in 2004. During the last decade,an investment trend has been developing, as il-lustrated in figures 1 and 2.

Figure 1 shows that bathroom market demandhas increased, with the rate of renewal of existingbathrooms rising at the beginning and middle ofthe 1990s and stabilized at present at a relatively

188 Journal of Industrial Ecology

R E S E A R C H A N D A N A LYS I S

0,0

1,0

2,0

3,0

4,0

5,0

6,0

7,0

8,0

Sep.9

0

Mar

.91

Sep.9

1

Mar

.92

Sep.9

2

Mar

.93

Sep.9

3

Mar

.94

Sep.9

4

Mar

.95

Sep.9

5

Mar

.96

Sep.96

Mar

.97

Sep.9

7

Mar

.98

Sep.98

Mar

.99

Sep.99

Mar

.00

Sep.0

0

Mar

.01

Sep.01

Mar

.02

Sep.0

2

Mar

.03

Sep.0

3

Mar

.04

Sep.0

4

Mar

.05

Sep.0

5

Perc

en

t o

f h

ou

seh

old

s

Figure 1 Purchase (black line) and planned purchase (gray line) of new bathrooms.Source: IFKA (2005). The original data source for the graph (including more recent data) have also beenprovided by Nielsen (2006).

high level (Institute for Business Cycle Analysis2005). Figure 2 illustrates that the number of sup-plied sanitary appliances (e.g., toilets and sinks,which are mainly used in bathrooms) has, in to-tal, increased 58% from 1998 to 2004 (which is

0

2.000

4.000

6.000

8.000

10.000

12.000

14.000

16.000

1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004

To

ns

0

2.000

4.000

6.000

8.000

10.000

12.000

14.000

16.000

18.000

20.000

Nu

mb

er

of

dw

ellin

gs

Supply Development in housing

Figure 2 Developments in the supply of sanitary commodities (left axis) and the numbers of dwellings inDenmark (right axis). Source: Commissioned work by Statistics Denmark, based on industrial commoditystatistics of sanitary commodities (import + production – export = supply to Danish bathrooms in weight)and occupied dwellings by time, area, type, and construction year.

significantly more than the increase in new hous-ing). This indicates that bathrooms have turnedinto a more significant consumption area in Den-mark; a similar trendhas been observed in otherWestern countries, such as the United States and

Quitzau and Røpke, The Construction of Normal Expectations 189

R E S E A R C H A N D A N A LYS I S

the United Kingdom (Shove 2003). The focuson bathrooms has come later than the interestin kitchens, so fewer households have already re-placed their bathrooms. Furthermore, more bath-rooms can be added in each dwelling, which is notusual for kitchens (except for the recent trend to-ward establishment of outdoor kitchens). Bath-rooms thus represent a potential area of furthergrowth in consumption and further escalation ofnormal standards of everyday life.

Methodological Approach

The present study is based on a problem-oriented, transdisciplinary approach, with the in-tention to achieve an understanding of the bath-room boom and a deeper insight into the va-riety of drivers involved in a specific consump-tion boom and in the construction of new nor-mal standards over time. The emergence of newnormal consumption standards is a complex pro-cess, with economic, social, and cultural dimen-sions that cut across macro, meso, and micro lev-els. In accordance with this complexity, we drawon a wide range of theories that help us to in-terpret and organize our empirical observations.The main theoretical inspiration comes from var-ious sociological and anthropological theories onconsumption and everyday life, combined withinsights from economics.

The empirical data are provided through acombination of methods, from reviewing exist-ing statistical material to gathering various typesof primary qualitative data concerning bathroomconsumption:

• Review of existing statistical material. Thesources include both official statistics andmarketing analyses, whenever available.This material provides various details aboutbathroom consumption.

• Review of the magazine Bo Bedre (in En-glish, Live Better). This monthly maga-zine covers interior decoration and is theoldest Danish magazine within this field(first published in 1961 and still a coremagazine). Our sample included 2 yearsper decade (1961, 1965, 1970, 1976, 1983,

1986, 1993, 1996, 2000, and 2002). Weread through each of these issues of the mag-azines to collect articles and advertisementsconcerning bathrooms. This material pro-vides insight into changing ways of perceiv-ing, arranging, and furnishing bathrooms inDenmark.

• General observations on current coverage ofbathrooms. This involved materials gath-ered from various media (magazines, news-papers, radio, television), visits to exhibi-tions and shops, and contact with bath-room suppliers. This material provides in-sight into current trends.

• Qualitative interviews on bathrooms. We car-ried out six semistructured qualitative inter-views to investigate how individuals reno-vate, arrange, and use their bathrooms. Theinformants were chosen to provide insightinto various ways of life and various bath-room experiences. Common for all infor-mants was that they were families with (orexpecting) children and that they had re-cently experienced changes in relation totheir bathroom setting. The informants var-ied in relation to age, educational back-ground, type of residence, and geographicalresidential area. Each of the interviews tookplace at the family’s home and was carriedout as a semistructured conversation abouttheir everyday life and their way of arrang-ing and using their bathroom. This mate-rial provides in-depth insight into the spe-cific setting in which bathroom renovationsoccur.

The following two sections are based on in-terplay between, on the one hand, theoreticaland empirical insights from other studies and, onthe other, a presentation of our own empiricalobservations. We start by considering the moregeneral consumption drivers related to housingrenovation and furnishing, and in this section ofthe article we draw mainly on existing studies,supplemented with examples from the bathroomcase. Then we turn to the consumption dynamicsrelated specifically to renovation and furnishingof bathrooms, and here we mainly draw on ourempirical observations.

190 Journal of Industrial Ecology

R E S E A R C H A N D A N A LYS I S

General ConsumptionDynamics Related to HousingRenovation and Furnishing

Basically, of course, housing quality and hous-ing renovation depend on economic growth andthe relatively high income elasticity of housingexpenditures. Furthermore, the general trend to-ward better housing standards has been heavilysubsidized in Denmark by political measures sincethe welfare state first emerged. In the years fol-lowing the Second World War, there was a se-vere housing shortage, and the building of newhousing was supported both through public sup-port for social rental housing and through taxallowances for homeowners. When the housingsubsidies and tax allowances were in place, it be-came politically impossible to change the systemfundamentally because of vested interests and thedelicate balance between the interests of home-owners and tenants. In spite of minor changes,housing is thus still a subsidized part of con-sumption, which obviously contributes to the in-creasing number of square meters per person overtime.

Consumption is also high with regard to ren-ovation, in decoration and furnishings. Throughthese consumption activities, the resident bothincreases his or her standards and personalizesthe house or apartment by transforming it intoa home. The interest in these activities has along history, but recent years have seen an up-surge of this interest. This is reflected by the in-creasing attention to activities related to reno-vation, refurbishing, and interior decoration inthe public media. Prime time television is de-voted to a large number of programs displayingindividuals who undertake renovation projectsunder the guidance of interior decorators andother professionals (TV2 2006), and such pro-grams receive great attention. For instance, pro-grams such as Roomservice (in English, ChangingRooms) and Huset (translates into The House),broadcast on the public service channel TV2,were viewed by an average of 15.5% of the Dan-ish population over 12 years (corresponding toabout 800,000 viewers) for all the seasons theseprograms were shown, which often placed themon the top-ten list of the week’s programs onTV24 (TNS Gallup TV-Meter 2006).

In the following, we discuss why home decora-tion is so important and is becoming increasinglyso. First, we concentrate on consumption driversthat apply to modern societies in general and,in some cases, to the Scandinavian countries inparticular, and then we add a few drivers that arespecific for the recent period when the bathroomboom has emerged. The following outline drawson different Scandinavian studies, particularlysome by Marianne Gullestad (1992, 1989), a Nor-wegian cultural anthropologist who has studiedNorwegian households in the 1970s and 1980s.Her observations are supported by Swedish andmore recent Danish studies (Lofgren 1984, 1990;Gram-Hanssen and Bech-Danielsen 2004, 2000;Winther 2004) and by more general theoreticaldiscussions on modernity (Beck 1992). The out-line is combined with a presentation of some ofour own observations from the bathroom case.

Drivers in Modern Societies

Identity formation is often pointed out as animportant aspect of consumption and a strongdriver behind increasing consumption (Røpke1999). As commonly observed in studies of late-modern societies, individuals’ social roles are nolonger given factors established by tradition andsocioeconomic circumstances; therefore, individ-uals face the challenge of forming their own iden-tity. In the process of identity formation, individ-uals cannot choose whatever they like, as they aredependent on having their identity confirmed byothers in a process of symbolic communication.For instance, through the way a person dresses,he or she sends out visual messages that otherpeople respond to, by either confirming or re-jecting the self-image that the sender intendsto communicate. These conditions imply thatthe expressive side of everyday activities becomesmore important and that the symbolic value be-comes detached from the practical use value forsuch consumer goods as textiles, food, and holi-day travels. Gullestad (1992) argued that this hasalso happened for the home, and this develop-ment is intensified when economic growth andincreasing incomes are accompanied by increas-ing possibilities for choice. When a rich variety ofitems and materials for furnishing and decorating

Quitzau and Røpke, The Construction of Normal Expectations 191

R E S E A R C H A N D A N A LYS I S

the home is supplied, the home becomes an ex-pressive manifestation of ever more subtle andcomplex messages (Gullestad 1992).

Working on the home has a special status, be-cause the home is the base for everyday life—thepoint of departure for integrating the activitiesof everyday life (Gullestad 1992; Bech-Jørgensen1994). A person’s life is closely related to thehomes in which he or she has lived, so whenpeople are asked to tell the story of the placeswhere they have lived, they tell their life sto-ries (Gullestad 1992; Gram-Hanssen and Bech-Danielsen 2004). Forming the house (or apart-ment) and forming the life are closely related,and forming the home is a core identity project—inrelation to family relationships, social referencegroup, and lifestyle: “People create themselves asindividuals and as families through the processesof objectification involved in creating a home”(Gullestad 1992, 79). For persons living alone,the home can be an important expression of free-dom and independence, because it is a product oftheir own choices and abilities (Gullestad 1992;Christensen 2001), and for families, home im-provements can be a joint project that unitesthe family. Through the project of building thehome, the family is constantly being repaired andrenovated, so building the home is about building thefamily (Lofgren 1990). Home improvements bothcreate and express unity, as the physical home be-comes a visible framework for the existence of thefamily and symbolizes the emotional closeness ofthe family members.

Both a move to different dwelling and morethorough renovations within a given dwellingare often related to life phase changes when de-mands arise for different spaces and changed ar-rangements. No longer do such life phase changesoccur only due to the traditional pattern of start-ing a family that gradually develops. The highnumber of divorces and the establishment ofnew marriages, confirmed by new children, mul-tiply the number of life phase changes, and thesechanges call for rearrangements at both the prac-tical and the symbolic levels. When people re-marry, they can rarely accept moving into roomsdesigned by others—a new family needs a newsymbolic framework (Christensen 2001).

The symbolic unity of the family expressed inthe home has become even more important con-

currently with the increasing fragility of the fam-ily’s solidarity (Gullestad 1992). The centripetalforce related to the individualization projectsof family members, women’s economic indepen-dence, and the like imply strong pressures onthe family, leading to high divorce rates (Beck1992; Dencik 1996). There is thus a strong needfor continuous confirmation of the relationshipthrough cooperative and symbolic efforts. Thisneed is further strengthened by the increasingemotional importance of families. Whereas familyhouseholds are no longer necessary as basic eco-nomic and productive units in society, they areemotionally more important than ever. In sec-ularized societies, religion no longer offers inte-gration and meaning, and for many “the homeand the sphere of intimacy have become sourcesfor deeper meanings” (Gullestad 1992, 82). Beck(1992) argued along the same lines, stating thatthe loss of God, traditions, and bonds to socialclass and neighbors imply that ever more hope isvested in the relationship to partner and childrenas the last defense against loneliness. When thehome is seen in this perspective, it is not surpris-ing that so much is invested in this key symbol ofcommunity.

The act of undertaking projects to decoratethe home—or specifically the bathroom—can initself also represent an important driving force forconsumption. Some find renovation and decora-tion activities in the home particularly enjoyable,as they offer an opportunity for creativity and man-ual work in an industrialized society where muchcreative and skilled artisan’s work has disappearedfrom work life. In a study of home decoration inDenmark (Gram-Hanssen and Bech-Danielsen2000, 2004), some of the informants chose tobuy an old house in need of repair because theyliked to do the work. Work related to home im-provements still often reflects a traditional gen-der division of labor, whereby the couple plans to-gether what to do, the woman takes care of theaesthetic aspects, and the husband does the prac-tical work (Gullestad 1992; Gram-Hanssen andBech-Danielsen 2004). In modern Scandinavianfamilies, the division of tasks cannot be takenfor granted and must constantly be negotiated.In these negotiations, men often prefer to un-dertake tasks related to renovation and redecora-tion rather than cleaning and other traditionally

192 Journal of Industrial Ecology

R E S E A R C H A N D A N A LYS I S

female tasks, and this division of labor is often ac-cepted by the wife. Gullestad (1992) formulatedit this way: “Making home improvements is in aspecial way an expression of a man’s love for hiswife” (85).

In addition to social and cultural considera-tions, it is important to emphasize an economicmotivation for homeowners: Renovation activi-ties in the home—particularly, modernization ofkitchens and bathrooms—are considered to be in-vestments rather than consumption, as they willbe reflected in a higher price should the houseor apartment be sold. Therefore, this category ofconsumption is considered much more legitimatethan most other ways of spending money—alsoin families with reminiscences of old-fashionedthrift. Furthermore, the capitalization of renova-tion expenditures in the price of the house impliesthat it is easier to fund such activities with loansthan it is to fund other forms of consumption.

The above observations make sense in mostof Western Europe and North America, but theScandinavian countries offer particularly strongexamples of home-centered cultures. One reasonis the climate, which limits the possibilities forsocializing outside. And, at least until recently,pub and restaurant culture was not very well de-veloped, so the home has been and still is animportant setting for social life. Another reasonis that modernization processes related to secu-larization and disintegration of traditional gen-der roles have advanced particularly far in Scan-dinavia. Finally, Gullestad (1992) argued thathome improvement gives Norwegians “the op-portunity to carry out creative and playful activ-ities camouflaged as serious useful things which‘must’ be done” (80). This fits well with a cultureof modesty, but, given that this culture is losingground, this form of legitimization is probably notso important anymore. The idea of somethingthat “must” be done has survived, however.

These observations on identity formation,building the family, creative activities, and eco-nomic considerations are clearly reflected in ourmaterial on bathrooms. It is a relatively recentphenomenon that the arrangement and deco-ration of bathrooms have acquired a richer po-tential for symbolic messages. In the early his-tory of bathrooms in the late 1900s, just to havea bathroom was a sign of social status (Lupton

and Miller 1992), and later, when bathroomsbecame standard, the symbolic messages weremainly related to hygiene and cleanliness—withshining white tiles and metallic taps. The firststeps toward increasing interest in bathroom dec-oration were taken in the early 1960s (Quitzauand Røpke, forthcoming), but, after a slow start,the present potential is overwhelming. The mag-azine Bo Bedre (Live Better) increasingly focuseson personalization and individualization in re-lation to bathroom decoration and renovation,and the variety of materials, objects, and arrange-ments that can be used in the identity-formationproject has increased immensely. Current mag-azines tend to divide bathroom accessories intodifferent styles (e.g., masculine, feminine, freshand colorful, romantic sensations, and ethnicbrushes) when they guide readers through variousmessages (Boligmagasinet 2003 54–57). Similarly,producers attempt to single out their products bydifferentiating them, for instance, through ex-clusive or romantic designs (Grohe 1970; SphinxSilica 1983; Cadazzo 1993; Vola 1996; Strømberg2003). Some of our informants clearly drew onsuch messages when they decorated their ownbathrooms and created what they associated withpersonal expression.

The importance of the home-building projectwas relevant for all the informants, and someenjoyed the creative work involved. In partic-ular, a couple in their 50s with one son livingat home truly enjoyed undertaking a variety ofprojects in their home—often in a way that il-lustrates the traditional gender division of labor.The wife, who was mostly absorbed by interior de-sign activities, rearranged the home and pursuednew ideas about decoration (to such an extentthat her husband had given up the idea of fas-tening any wires). In relation to the bathroom,she could only rearrange the fixtures to a lim-ited extent, but she had made certain improve-ments, such as removing a cupboard door andplacing free-standing baskets on the cupboardshelves instead. The husband, being more ab-sorbed by do-it-yourself (DIY) projects, enjoyedrepairing things that were broken or fabricatingthe things they would like to have. He had takenon several DIY projects in the bathroom—forexample, installing speakers and producing fittedcabinets—and he had planned new projects, such

Quitzau and Røpke, The Construction of Normal Expectations 193

R E S E A R C H A N D A N A LYS I S

as mounting a roof window. Although this cou-ple expressed practical reasons for taking on suchprojects, it was clear that the opportunity for cre-ativity and manual work represented enjoymentin itself.

The identity issue was clearly relevant for oneof our informants in particular, a young womanliving with her son. She emphasized that forher the task of renovating a new apartment wasalso a means of getting through a recent divorce.Concurrent with the renovation, the identity ofthe family was reestablished, and the work con-tributed to a closer bonding between this singleparent and her child, as they proudly spoke ofthe renovated apartment—and not least the nicebathroom—as an achievement.

Period-Specific Drivers

The arguments above can explain why hous-ing renovation and furnishing are popular activi-ties that people plunge into when they can affordit, thus relating the specific timing of these activ-ities to the economic possibilities. The upsurge inrenovation activities in Denmark during the last10–15 years is strongly correlated with incomegrowth and especially the dramatic escalation ofproperty values. New types of loans were intro-duced in the mid-1990s and early 2000s (loanswith variable interest rates in 1996, and loanswithout amortization in 2003), which meant thata buyer could afford to pay a higher price. Obvi-ously, because such new possibilities become cap-italized in property prices over some years, alreadyestablished owners earned fortunes that could becashed in for consumption. This was also encour-aged by low real interest rates.

As already mentioned, the increasing con-sumer interest in renovation activities hasdeveloped in interplay with increased com-mercial supply of materials, equipment, consul-tancy services, magazines for inspiration, and,not the least, a proliferation of television pro-grams broadcast on both commercial and pub-lic service channels covering different aspectsof housing, renovation, and decoration. Thesetelevision programs can be seen as part of thebroader trend toward provision of light en-tertainment at the expense of more informa-tive and educational programs that followedin the wake of the commercialization of televi-

sion and the increasing number of competingchannels. Since the end of the 1980s, all thesechannels have provided new possibilities for ad-vertising, so that retailers have better opportu-nities to reach more consumers, but even moreimportant was the influence of advertising on thesupply of programs. Although Denmark has strictregulations about advertising on sponsored pro-grams (which is less the case in the United States,where sponsors, such as Sears on the ABC net-work show Extreme Makeover Home Edition, havemore freedom5), companies are probably more in-terested in spending their advertising money onchannels with programs that both attract manyviewers and integrate the companies’ productswith their advice to consumers (e.g., when pro-grams such as Roomservice feature a detailed prod-uct list on their Web site; Roomservice 2006).

Specific ConsumptionDynamics Related to BathroomRenovation and Furnishing

Whereas the previous section dealt with thegeneral drivers related to housing renovation andfurnishing, in this section we turn to the morespecific drivers behind the increasing focus onbathrooms. First we discuss the trend toward anincreasing number of bathrooms in the home, andthen we address the trend toward altered ways ofperceiving and using the bathroom.6

The Multiplication of Bathrooms

Usually, Danish dwellings have only one bath-room. During the 1970s and 1980s, however, itbecame popular to have a guest toilet, and sincethe 1990s a trend toward having two bathroomsfor daily use has emerged. It is not possible toobtain precise statistical information on thesechanges over time, but in January 2006, 19.7% ofall detached houses, terraced houses, and doublehouses had two bathrooms (based on informationfrom Statistics Denmark and Bolius, a knowl-edge center for homeowners in Tre badeværelser[2006], and own calculations). Presently, severalDanish builders of standard housing mostly of-fer detached houses with two bathrooms, onein connection with the master bedroom andone in connection with the children’s rooms(Bulow and Nielsen 2006; Eurodan 2006; Lind

194 Journal of Industrial Ecology

R E S E A R C H A N D A N A LYS I S

og Risør 2006). Allan Dahl, managing director ofSkovbo,7 observed that the once-popular guesttoilet has been replaced by a guest bathroom andthat the main bathroom of the house has to con-tain both a shower and a spa/bath (Danske husehar vokseværk 2006). Consequently, the builders(e.g., Skovbo and Eurodan) have observed an in-creasing demand for more square meters devotedto bathrooms (Danske huse har vokseværk 2006).

An important part of bathroom investmentsthus consists of adding more bathrooms to ex-isting dwellings and including more bathroomsin newly built dwellings. Informants often com-plain about congestion and capacity problems inthe bathroom, especially when the household in-cludes teenagers, and this argument is decisive forthe addition of new bathrooms or for choosinga dwelling with more bathrooms when a familymoves.

The capacity problems arise from several dif-ferent trends. The most important is the chang-ing showering practice—from the weekly bathor shower to the daily (or twice daily) shower.It is not easy to date this change, but the in-formation we have gathered, both from inter-views and from informal discussions with families,friends, and colleagues, indicates that the changetook place during late 1960s and the 1970s. Suchchanges do not involve everybody, but since the1980s the daily shower has been a norm for theyounger and middle-aged generations. There areno data to substantiate this claim, but a recentqualitative study on teenage cleanliness (Gram-Hanssen 2007) indicates the strength of thisnorm. Another indication is the widespread in-dignation when old people in need of care arenot offered a daily shower (a much-debated is-sue during the Danish general election campaignin 2007). Hand and colleagues (2005) identifiedthe same trend in the United Kingdom and triedto explain it within a longer historical perspec-tive than we apply here. In relation to recenthistory, the British account includes some tech-nical aspects that are less relevant in a Danishcontext, where the change took place during aperiod with little technical progress with regardto bathroom installations. More people gainedaccess to bathrooms during this period, whichwas characterized by much new building, but inmany households the change took place within

a basically unaltered physical framework. First ofall, it was a change in standards and expectations,with less tolerance of bodily smells and stricterdemands for freshly washed hair. An importantchange during the period that might have hadan impact on norms was the rapid increase inwomen’s participation in the workforce and therelated wish to be “presentable.” The increase inshowering might also have codeveloped with thediffusion of the washing machine, which helpedprovide clean clothes at shorter intervals and thuscalled for bodily cleanliness as well.

Whatever the reasons behind the changingshowering practice, it has contributed to capacityproblems in the bathroom. As Danish women, in-cluding women with small children, now have al-most the same level of participation in the work-force as men and usually work full time, the com-mon pattern is that the whole family leaves thehouse in the morning, and all family membershave to get ready within a relatively short slotof time. Coordinating activities in the bathroommay be especially challenging, compared to otherrooms in the house, as the bathroom is a place ofintimacy and privacy. Family members may wishto be on their own when using this particularroom. Of course, families find practical solutionsto this coordination problem (e.g., making useof the bathroom one by one or using it simulta-neously), but the calls for relieving the problemthrough increased capacity are strong.

This pattern is reinforced by the general trendtoward individualization in modern societies:Each individual seeks independence and findsit unacceptable to have to wait his or her turnor to share. This is also reflected in the acqui-sition of multiple televisions, video players, andother devices. This pursuit of increased capacity isalso supported by new ideas of personalized bath-rooms, illustrated, for instance, by images of bothintimate and remote parental bathrooms (e.g., indirect connection to the master bedroom) andcolorful and playful children’s bathrooms, or byfeminine and masculine bathrooms for wife andhusband, respectively (Grey et al. 1998; Boligma-gasinet 2003). In this trend, the objective is tohave a private bathroom in connection to eachbedroom—besides, of course, one for the guests.

In a study on British house extensions (i.e., ad-ditions to dwelling space), Hand and colleagues

Quitzau and Røpke, The Construction of Normal Expectations 195

R E S E A R C H A N D A N A LYS I S

(2007) also observed the trend toward themultiplication of bathrooms, and their respon-dents also mentioned congestion problems in thefamily and the interest in having toilets bothdownstairs and upstairs (a more obvious consid-eration in a British multistory dwelling than inthe Danish housing tradition). Besides, some oftheir respondents emphasized that they wantedadditional bathrooms and toilets because it isconvenient when they have guests—some housesare simply transformed into guesthouses, whereguests have facilities they can think of and use as“their own” (Hand et al. 2007, 14–15). The ideaof guest toilets is also found in Danish households,but our observations indicate that this was morefashionable in the 1970s, whereas the presentmultiplication of bathrooms is mainly motivatedby congestion and timing problems.

In some cases, the installation of new bath-rooms in relation to home extensions, conver-sion of basements, and the like makes it possibleto establish a more independent accommodationunit within the household, so grown-up childrenstay with their parents a little longer. After along period when children left home at an everyounger age—concurrent with improvements inthe housing situation—the trend has turned inrecent years (Carlsen 2005). Parents have be-come less restrictive, and young people enjoy theconvenience of staying at home.

The Multifunctioning of Bathrooms

Besides multiplying bathrooms, much invest-ment is related to the arrangement and up-grading of bathrooms. In the British study onhome extensions mentioned earlier, Hand andcolleagues (2007) distinguished between thetrends for kitchens and bathrooms, observing thatbathrooms are multiplying, whereas the spatialchanges in the kitchen appear to be related tomultifunctioning. Our study suggests that mul-tifunctioning is also an important element ofbathroom renovations in Denmark and thus con-tributes to the increased focus on bathrooms. Theinvestments go beyond simply renewing outdatedbathrooms, as the functions of the room are beingdeveloped in new directions.

The changing functions are indicated by thechanging images that drive bathroom renova-

tions. As Hand and Shove (2004) observed intheir study of kitchens, “investments in new ap-pliances and in kitchen makeovers were com-monly desired, anticipated or justified as a meansof bridging between the dissatisfactions of thepresent and an image of a better, more appropri-ate future” (4). They emphasized that the imageincludes not only the potential pleasures relatedto changing material possessions but also the per-formance of specific practices related to the ma-terial changes. In our analysis of our interviewmaterial, magazines, advertisements, and othermaterial, the focus is thus not only on aestheticchanges but also on the changing practices andreinterpretations of old practices that the imagesimply.

The importance of images as a driver of con-sumption was emphasized by Campbell (1987),who identified a modern form of hedonism that ispursued through daydreaming: Pleasure is derivedfrom imagining a future situation that one couldachieve by acquiring various consumer goods.When the consumer succeeds in acquiring thegoods, the reality often falls short of the imag-ined pleasure, and the consumer ventures intonew dreams and a ceaseless search for novelty.

More recently, related ideas have been elabo-rated by others who study modern time-pressuredfamilies and the impact of busyness on consump-tion. Hochschild (1997) described in The TimeBind (see also Wilson and Lande 2005) one ofthe coping strategies applied by busy families: Aparent who is not able to live up to her (or his)ideal of being a good parent can cope with this bydistinguishing between her “potential self”—theperson she would be if only she had time—andher “real self” with limited time. Objects can thenfunction as totems to the potential self, as theyrepresent a potential future when the ideals canbe realized. Families are thus motivated to buy,for instance, fishing equipment that can be usedin an imagined future when the family has timeto go fishing.

Sullivan and Gershuny (2004) elaborated onthis observation and identified a particular formof consumption whereby expensive leisure goodsare purchased and stored away due to lack oftime. By owning the goods, a person can sig-nal to himself or herself what sort of person heor she is (e.g., a person actively participating in

196 Journal of Industrial Ecology

R E S E A R C H A N D A N A LYS I S

outdoor activities) and thus strengthen his or herself-image, and although the goods are seldom ornever used, satisfaction may be obtained by themere consciousness of possession. Such consider-ations can also be relevant for the bathroom case:Sometimes consumers succeed in realizing theirdreams and carrying out the imagined practices,but sometimes the goods remain as symbols of animagined future.

In the following, we aim at identifying someof the dominant images in relation to how a bet-ter and more appropriate future is represented inrelation to bathrooms. Of course, in each of theindividual stories told by our informants, severalof these images are combined, but for analyti-cal purposes we identify the different dimensionsseparately.

Taking care of the body has from the begin-ning been a core activity in the bathroom, anddaily practices such as washing and preparing thebody are still viewed as central bathroom func-tions. In a symbolic sense, this employs the bath-room as a setting for backstage preparation thathas to do with relations between self and so-ciety, with individuals conveying certain mes-sages to the surrounding world through thesetypes of performances—for example, ensuringproper front-stage appearance (Goffman 1959;Shove 2003). Currently, these preparation activ-ities seem more important than ever. Accordingto a Danish time use study, an increasing amountof time is used for taking care of the body. In2001, Danish women spent almost an hour wash-ing and dressing on an average day, which rep-resents an increase of half an hour since 1987,whereas men spent around three quarters of anhour in 2001, an increase of 20 min since 1987(Bonke 2002). The variety of specialized productscurrently found in supermarkets and special storesis impressive, offering consumers a wide varietyof options for customizing aspects of themselves(skin, hair, and scent) after having stripped thebody of its natural odors (Shove 2003). Spendingtime on taking care of the body is not new, as hu-mans have always modified and ornamented theirbodies, sometimes in highly painful ways, but itis a relatively new phenomenon that such a largepart of the population spends so much time on theprocess. Present demands concerning body care

were effectively summarized in the novel BridgetJones’s Diary (Fielding 1996):

6. p.m. Completely exhausted by entire dayof date-preparation. Being a woman is worsethan being a farmer—there is so much har-vesting and crop spraying to be done: legsto be waxed, underarms shaved, eyebrowsplucked, feet pumiced, skin exfoliated andmoisturized, spots cleansed, roots dyed, eye-lashes tinted, nails filed, cellulite massaged,stomach muscles exercised. The whole per-formance is so highly tuned you only need toneglect it for a few days for the whole thing togo to seed. Sometimes I wonder what I wouldbe like if left to revert to nature. . . . Is it anywonder girls have no confidence? (30)

At a general level, this can be seen in theperspective of identity formation in postmod-ern societies, where also the body is viewed asa vehicle of self-expression, and where the com-mercial supply of means for constructing andmaintaining bodily appearance is larger than ever(Howson 2004). The theoretical discussion of thebackground and implications of the preoccupa-tion with bodily appearance and body fitness andhealth is to be found in a variety of literaturethat we must omit here, but we wish to empha-size that the developing preoccupation with bodycare influences the visions of the bathroom andcontributes to its changed status.

Demands on the bathroom are escalating aspreparation activities become more demandingand require more and more time. The bathroomis turned into a kind of beauty salon, providing theright conditions: a multitude of body care prod-ucts (shampoos, balms, and cremes) and tools(razors, nail file, scissors) and a proper setting(with mirrors, storage capacity, and a nice at-mosphere). The current fitness trend, wherebypeople exercise their body as a part of body careactivities, may also influence the future status ofthe bathroom, as it can develop into a settingfor fitness activities in the home. Many peoplego to fitness centers, but we can observe an in-creasing supply of home-fitness equipment fromboth ordinary supermarkets and specialist stores.It is plausible that the bathroom can turn intoa kind of fitness center, especially given the on-going trend toward enlarging the room, which

Quitzau and Røpke, The Construction of Normal Expectations 197

R E S E A R C H A N D A N A LYS I S

will make it more appropriate for such activities.Furthermore, it seems plausible that fitness fa-cilities in the home can be an example of thephenomenon whereby objects function as totemsto a potential self and as a device for developingself-identity—unless, of course, the facilities pro-voke a bad conscience when they are not used asmuch as expected.

Another aspect of body care is the widespreadtendency to associate body care with wellness,pampering, and self-indulgence. Some people ex-perience body care activities, such as bathing orshowering, moisturizing the skin, and applyinghair balm as enjoyable, interpreting them as bodytreats, whereas others consider them to be labori-ous duties. In a historical perspective, bathing haslong been a valued and pleasant experience dueto the curative properties of water. Immersion inwater has been widely believed to benefit bothhealth and well-being (Shove 2003). The appre-ciation of this experience has shifted over time,however, and in many Danish homes, bathtubshave been gradually replaced with showers (moreappropriate for a quick wash), as daily shower-ing has become more commonplace. In 1979 aspokesperson from Max Sibbern, one of the mainsuppliers of sanitary appliances in Denmark, ex-plained that the bathtub was on its way out com-pared to the shower, which was considered moreefficient for daily use (Albertsen 1979).

Currently, the bath is experiencing a renais-sance in Denmark, as the idea of enjoying a nicebath regains momentum, but now as a supple-ment to the shower. It is worth noting, as someof our informants did, that the idea of health andpampering applies not only to bathing but also toshowering:

I think it [her evening shower] is just so nice.It is so relaxing. Ahh, then I relax. And I alsothink it provides such calm when I have takena bath. I feel such a pffff [exhales], not tiredbut relaxed. I get such a feeling of calm in mybody. And it’s lovely, oh ahh, you smell good.It’s also lovely to smell good in the morning,but then you still do for a little while yet.And ahh, then you are clean and lovely whenyou go to bed. (Katrine, aged 33, cleaningsupervisor)

Then [when you don’t have to consider oth-ers in relation to the warm water], I love to

take a very long, boiling hot shower. Withoutthinking about anything else at all than thatit is just wonderful. . . . It’s just, if there istime for it, such a luxury. Something enjoy-able that is just pleasant and terrific. (Betina,aged 34, self-employed animation instructor)

Often, the association between pleasure andshowering or bathing is related to accounts ofstress and hard work and, hence, a wish to delveinto body care once in a while, enjoying theopportunity to pamper oneself (Alt for Damerne1999; Boligmagasinet 2004; Tidens Bolig 2004). En-joying a relaxing bath is often portrayed as a wayof reacting against stress and as a healthy way torecover from a hard day’s work:

A bath can provide a feeling of being reborn,a gift in a busy everyday life. No matter howworn out you are, a 20-minute soak can giveextra energy. (Alt for Damerne 1999, 121)

The bathroom is definitely becoming thehome’s new room for enjoyment. The placewhere you relax and gather new energy fora hectic everyday life. (Boligmagasinet 2003,35)

Such tendencies contribute to the escalatingdemands on the bathroom, as the room becomesstaged as a place where people can find goodrecreational experiences. The bathroom comesto represent a kind of sanatorium, where morerecreational activities are located. This encour-ages the installation of more luxurious fixturesin the bathroom, such as freestanding bathtubsor spas, and other features—for example, trans-forming the shower into a massage shower—havealso become more popular (Bo Bedre 1993b; Bolig-magasinet 2003; Familieliv i badeværelset 2003;Byggecentrum 2004). Figure 3 shows an exampleof a bathroom sanatorium.

It has not been possible to collect data todocument this development, because bathroomsuppliers and producers are reluctant to revealtheir sales figures. Nevertheless, wellness is animportant issue for customers, noted the salesand marketing director of HansGrohe, ThomasLeth. According to Leth, the increasing focus onwellness is supported by the fact that the RainDance showerhead, which has a wellness fea-ture of providing huge amounts of water, nowrepresents 10% of the turnover of HansGrohe

198 Journal of Industrial Ecology

R E S E A R C H A N D A N A LYS I S

Figure 3 A private bathroom with a spa.Photograph of a friend’s bathroom, taken by theauthors.

(Sørensen 2007). The trend also influences theoverall arrangement of the room. For example,one of our informants described a romantic at-mosphere in the bathroom as being central tothe experience of a relaxing bath. Similarly, atypical illustration in the press is that of a personlying in a bathtub with foamy suds and a romanticsetting, with beautiful colors and lighted candles(Alt for Damerne 1999; Boligmagasinet 2004).

A special element of this well-being themeis the wish for retreat; the bathroom is increas-ingly presented as an oasis where individual fam-ily members can find peace and take care of them-selves. This develops further the idea of privacythat has long characterized the bathroom. Tradi-tionally, the room is considered to be a privatespace, placed relatively remotely, and with activ-ities being carried out behind a locked door andfrosted windows. This makes the bathroom oneof the few places in the home where individu-als can—without question—withdraw for a shorttime and be themselves. This symbolic status ofthe bathroom has probably contributed to nur-turing the current idea of making more conscioususe of the bathroom as a place for retreat, an ideathat is often put forward in media coverage:

Now, it is the bathroom that is the centreof the home. It is not here we gather, butit is here family members can find peace tocare for themselves. Pampering themselves inbeautiful surroundings. (Byggecentrum 2005)

Now, extra focus is being directed towardcontentment and well-being in the only room

where we can withdraw and be ourselves inpeace and quiet, the bathroom. (Spabad i storstil 2006)

As with well-being, retreat is linked to thehectic pace of people’s lives, as stress and hardwork give rise to a need not only for relaxing butalso for withdrawing. In several of our bathroomcases, husbands explained that they found reliefin the possibility of retreating from the hullabalooof everyday life by spending some time aloneon the toilet, reading. Other activities, such asbathing or showering, reflect the similar pleasureof having the possibility to enjoy a brief timealone. The current idea of retreat affects the sta-tus of the bathroom, as it is interpreted as a kind ofsanctuary, especially when it is linked to images ofpampering oneself and relaxing. Obviously, suchuse contributes to the demand for multiple bath-rooms so there is room for everyone.

The opposite idea to the idea of retreat wasalso present in the material we reviewed. Somepersons express the wish to enjoy each other’s com-pany in the bathroom. In general, the home isan important setting for socializing within thefamily, and recent developments in the kitchenreflect the increasing need for socializing in busyfamilies: It has become popular to arrange thekitchen as a “kitchen for conversation” (Sam-taleKøkken), where family members can be to-gether while they are preparing dinner (KVIK2006). Although bathrooms are not developinginto rooms for conversation, the idea of the bath-room as a private place is subject to change:

The bathroom is becoming the family’s mostpopular room to be in. Here, you shall be ableto use more time to care for your body in beau-tiful surroundings, and maybe entertain eachother while doing so. (Baderummet ændrerstatus 2004, 30)

One way of enjoying each other’s company isby taking care of daily routines together, interact-ing in the bathroom while preparing for the day.This was illustrated by one of our informants:

It was something we wanted—a bathroomwith two sinks. And we have it now, so we canbrush our teeth at the same time. That way,we can be together in the bathroom muchmore than we could before. Now, people

Quitzau and Røpke, The Construction of Normal Expectations 199

R E S E A R C H A N D A N A LYS I S

might say, yes, but brushing teeth takes only aminute, but it can take three or four minutesfor us both, with dental floss and all. So it ac-tually means a lot. (Henrik, aged 40, lawyer)

There are two aspects to this bathroom idea.One has to do with congestion problems in thebathroom (e.g., during the rush hour in the morn-ing). In order for daily preparation activities inthe family to go smoothly, it may be a possibility(or a necessity) to be together in the bathroomrather than have multiple bathrooms.

The other aspect has to do with finding timeto be together in a situation where many familiesexperience stressful lives.The bathroom and itsrelated activities thus become linked to ideas ofproximity, finding time to be together in stress-ful family lives. The proximity aspect also ex-plains why the bathroom may also, to a greaterextent, be used to perform recreational activi-ties together (e.g., enjoying a bath together), asthis provides yet another opportunity for qualitytime together. The status of the bathroom canthus be envisioned as a family room, or a kindof “living room,” on the same footing as otherrooms in the home where the family enjoy be-ing together. This image implies new demandswith regard to the physical layout of the room,as more space is typically necessary and some fix-tures have to be multiplied in order for severalpeople to use the room simultaneously. Also, wehave observed a tendency to develop bathroomproducts for more than one user. This is currentlythe case with spas, which are also designed for twoor more people (Jysk Spabad 2006; Westerbergs2006). Figure 4 illustrates a bathroom for two.

Two final issues that we want to emphasizeare convenience and aesthetics, as these havebecome more central in connection with currentdevelopments of the bathroom. With regard toconvenience, we observe that many new types ofappliances and accessories are making their wayinto the bathroom in connection with the ear-lier described development of bathroom activi-ties. This is also connected with new standardsand expectations in the home in general. For ex-ample, common products such as radios, televi-sions (even waterproof versions), and telephonesare now appearing in the bathroom (Familieliv ibadeværelset 2003; Boligkataloget Eksklusiv 2004;

Tidens Bolig 2004) to entertain the bathroom useror keep the busy bathroom user in contact withthe surroundings.

It had to come. The shower stall with built-in telephone. Who hasn’t been in the situa-tion where the telephone rings just as you arestanding there with your hair full of soapsuds.Instead of rushing out of the shower, you cannow push a button and redirect the call tothe shower. The same model also containsa built-in radio and a connection for a CDplayer. (Byggecentrum 2004, 5)

This suggests that the bathroom is beingturned into a high-tech room, with much effortbeing put into arranging the room in appropriateways with regard to facilities. This kind of con-sumption often requires more room, for practicalreasons (e.g., to make room for more storage orlarge equipment).

With regard to aesthetics, the private, hy-gienic, and utilitarian room has developed intoa presentable, beautiful, and impressive room,where individual styles and personal accessoriesreplace the standard bathroom picture (Luptonand Miller 1992; Bo Bedre 1996b, 2004; Baderum-met ændrer status 2004). The consumption trendsrelated to the rest of the home have diffusedto the bathroom, as this is now designed andequipped in the same way as the living room.In the coverage of bathrooms in Bo Bedre, thereis an increased interest in aesthetics. The issue ofdecoration is taken up in a larger number of arti-cles than in earlier years, and decoration is por-trayed as a more central element of the bathroom(Quitzau 2004). Characteristically, the aestheticsof bathrooms mainly concern the atmosphere ofthe room rather than such details as colors andaccessories:

The home’s wet room can easily breathewarmth, coziness and personality. We havechosen three bathrooms that resolutely turntheir backs on the white streamlined styleand are instead fashioned with colored walls,golden metals and dark woods. (Bo Bedre1993a, 68–71)

Providing good atmosphere involves both anice physical environment (e.g., heat and humid-ity) and a pleasurable aesthetic experience (e.g.,style). More tolerable and pleasant conditions are

200 Journal of Industrial Ecology

R E S E A R C H A N D A N A LYS I S

Figure 4 A room for two. Commercial picture from Westerbergs homepage (Westerbergs 2007).

expected because of the prolonged stays in thebathroom. As one informant put it, “one learnsto make many demands for the bathroom” whenone spends so much more time there. Centralthemes in the media coverage relate to notionsof well-being and of having a good experiencein the bathroom (Bo Bedre 1993b, 1996a, 1996b;Badeland 1996; Bo Bedre A-Z 2000; Boligmagasinet2004). The bathroom is staged as an oasis whereatmosphere and ambiance have high priority. Ithas emerged as a front-stage room: The bathroomdoor is, to a greater extent than earlier, left openfor visitors to take a peek. According to trendresearcher Kirsten Poulsen, the bathroom has be-come a showroom that reflects the identity of itsowner, and this only makes sense if the room isvisible (Sørensen 2007).

New Normal Expectations andTheir EnvironmentalImplications

The present bathroom boom is not only inter-esting as a consumption boom here and now, withthe immediate environmental implications con-nected with the renovation activities. Even moreimportant are the implications that the boom

might have for the long-term expectations re-garding the standards of bathrooms. Of course,the higher standards do not materialize across thewhole population over a short period, and eco-nomic crises may well curb the process of diffusion(it is illustrative that it took many decades to im-plement the simplest bathrooms in the majorityof dwellings), but the emerging expectations forma new aspiration level that many people will aimat and try to realize over time.

The present trends point toward emergingnormal expectations in Denmark that are char-acterized by the following:

• more than one bathroom in each dwelling,preferably more than two;

• more spacious bathrooms• with more functions• and more equipment related to the various

functions;• more focus on the personal appropriation of

the room through creative processes, moreinfluence from fashion,

• and thus more frequent replacements andrenovations of a room

• that has developed into a real front-stageroom merging aspects of various kinds of

Quitzau and Røpke, The Construction of Normal Expectations 201

R E S E A R C H A N D A N A LYS I S

rooms, such as the beauty salon, fitnesscenter, sanatorium, sanctuary, high-techroom, and family room.

These trends are not special for Denmark—rather, Danish developments are lagging a littlebehind changes in the United States. Accord-ing to a U.S. survey on bathroom habits, for in-stance, enlargement of bathrooms is the numberone bathroom design trend, and in general, theidea of having luxurious bathrooms with morefixtures (including spas, armoires for storage, mu-sic and television, and chaise lounges) is empha-sized (Grey et al. 1998; “Pleasant dreams” 2003;A Bathroom Guide 2005).

The increasing standards of bathrooms havevarious environmental implications. The multi-plication and enlargement of bathrooms implygreater use of energy and materials, both in theconstruction process (the bathroom is often moredemanding with regard to construction materialscompared to other rooms of the dwelling) and inenergy consumption (e.g., for heating and light-ing), and in the long term, bathroom develop-ment contributes to the increase in the overallsize of dwellings. In general, large houses con-sume more resources—both in construction andduring operation—as calculations by Wilson andBoehland (2005) demonstrated. These authorseven argued that increasing size may lead to amore than proportional increase in resource con-sumption, if the geometry of the house becomesmore complex.

The larger bathrooms make room for moreequipment and accessories, from sinks to TV sets,again with related environmental impacts in pro-duction, use, and disposal. An example is theintroduction of electronic equipment in bath-rooms, which adds to the known environmen-tal problems related to electronics—energy con-sumption, consumption of scarce raw materials,flame retardants, and problematic waste, for in-stance. In some cases, new equipment, such asfitness gear and spas, in private bathrooms cantransfer the use of certain services from the pub-lic to the private sphere. This can imply increaseduse of resources, as fewer resources are required toshare facilities than to multiply them—althoughless transport counteracts the increase.

The increased rate of replacement diminishesthe life span of bathroom elements and leads toincreased amounts of waste as the old elementsare disposed of. Local recycling stations in Den-mark have thus already noted the increased dis-posal load from kitchens and bathrooms (From2004). A particular concern in relation to therate of renovation is if people are so preoccupiedwith renewal that they choose to install facili-ties of poorer quality (which was the case withkitchens; Institute for Business Cycle Analysis2005), as this would contribute to the reductionof the life span of bathroom elements and demandquicker replacements.

The previous arguments are mostly directedtoward the implications of the changing mate-rial structures, without much consideration of thechanging practices that coevolve with materialchange. Including the bathroom’s usage in theequation tends to aggravate the environmentalimpacts, as the new infrastructure scripts prac-tices that are more water and energy intensive.It is difficult to predict whether people actuallywill follow the scripts of the new infrastructure(e.g., they may not have the time)—but if thepleasurable practices become increasingly popu-lar, even people without the most recent materialarrangements may try to enact them. Bathroom-related pleasurable and recreational activities of-ten involve increased use of hot water (e.g., along shower, bath, or spa). A Rain Dance Rain-fall overhead shower from Hans Grohe has aflow rate of 40 liters (L)8 of water per minute,according to product details, whereas a regu-lar hand shower, common in Denmark, has aminimum flow rate of approximately 9 L of wa-ter per minute (Hans Grohe 2007). When itcomes to pleasure, people tend to give priorityto a good bathing experience rather than takingsteps to minimize the use of water and energy.Danish authorities have achieved positive resultswith regard to decreased water consumption sincethe early 1990s, as many people have installedwater-saving toilets and other devices inspiredby campaigns and higher water taxes (Hoffmannet al. 2005; StatBank Denmark 2005); how-ever, the current developments in recreationalbathroom practices might undermine theseefforts.

202 Journal of Industrial Ecology

R E S E A R C H A N D A N A LYS I S

Concluding Remarks

When people plan their new bathrooms dur-ing the present boom, they may well have greatexpectations regarding the pleasures to be ex-perienced from the new aesthetic arrangementsand the practices they intend to indulge in—andsometimes these expectations will be fulfilled.When viewed from just a slightly longer perspec-tive, however, the present boom is seen to be in-tegrated in a process that generates new normalexpectations—new standards for how a decentbathroom should look and how many bathroomsare needed in a household. The bathroom casethus exemplifies the development of new normalexpectations—a development that takes place inmany other fields of practice and consumption aswell.

The case demonstrates the complexity ofdrivers and other aspects involved in the con-struction of new normality. The changing ma-terial standards coevolve with a variety of so-cial trends and a broad range of consumptiondrivers—for instance, the increasing importanceof the home as a core identity project and a sym-bol of the unity of the family, the opportunities forcreative work, the convenience of more groom-ing capacity during the busy family’s rush hours,the perceived need for retreat and indulgence ina hectic everyday life, and the increased focuson body care and fitness. The case also illustratesthat when people have the economic possibili-ties for increasing consumption, they will havemany ideas that are closely integrated with theirprevailing everyday concerns.

Because environmental concerns in consump-tion are still mainly related to various symbolicactions, the gradual development of new nor-mal expectations is seldom considered in anenvironmental perspective. There is an obvi-ous need to bring this issue higher up on theagenda for both citizens and politicians. Proba-bly, only few consumers are willing to go againstdominant trends, but if their civic responsibilitywere invoked more people might be willing tocounteract the process of rising standards.AsShove (2003) pointed out, the complex dy-namics of this process open up a variety ofintervention points that can be used, if the po-litical will exists. For instance, through collec-

tive decisions, we can constrain our economicpossibilities through various forms of taxation—including taxes on increased property value—andby reducing general housing subsidies. Anotherwell-known suggestion is to restrict advertising,particularly on television, and thus reduce the in-spiration for consumption. Simultaneously, thecomplex consumption drivers call for consider-ing everyday concerns in ways that do not en-courage material consumption. For instance, anobvious approach is to take steps to reduce busy-ness through shorter working hours. With lesstime pressure and more attractive collective fa-cilities, it might be less tempting to acquire allkinds of equipment and facilities individually. Atough challenge is determining how to encour-age more immaterial ways of identity formation.Maybe more of people’s time can be opened forengagement in less resource-intensive and moretime-consuming activities that can contribute toconstituting identity.

Acknowledgements

Maj-Britt Quitzau gratefully acknowledgeseconomic support from the Department ofPolicy Analysis within the National Envi-ronmental Research Institute of Denmark,Roskilde, Denmark, and the Danish Re-search Centre for Organic Farming, Tjele,Denmark. A previous version of this articlewas presented at The International Society forEcological Economics conference in Montreal,Canada, in July 2004. The article has benefitedfrom comments from participants at this confer-ence. We are also grateful to the referees for care-ful comments on a previous version.

Notes

1. Editor’s note: See the special issue of the Journalof Industrial Ecology on consumption and industrialecology, volume 9, numbers 1–2, for an extensivecollection of articles on this topic.

2. In this article, the term bathroom refers to a roomthat typically includes a toilet, a sink, and a facilityfor either showering or bathing.

3. One square meter (m2, SI) ≈ 10.76 square feet (ft2).4. E-mail correspondance with Lone Bjerring, who is

a viewer analyst at TV2, regarding statistics on

Quitzau and Røpke, The Construction of Normal Expectations 203

R E S E A R C H A N D A N A LYS I S

numbers of viewers of Roomservice and Huset (28June 2006). The TV meter is based on registersof all TV viewing among 1,000 selected house-holds, thus representing the total population inDenmark.

5. See, for example, the Web site of the Americantelevision program Extreme Makeover Home Edition(http://abc.go.com/primetime/xtremehome/index?pn=index).

6. In this study, we have chosen not to deal with issuesrelated to the body, including aspects of nudity andexcretion, although these are important aspects ofsocial norms that influence the design and use ofbathrooms. This is because the topic opens up awhole new literature.

7. Skovbo is a construction firm that specializes inwooden standard houses.

8. One liter (L) = 0.001 cubic meters (m3, SI) ≈ 0.264gallons (gal).

References

Albertsen, E. H. 1979. Badeværelset i 60erne og 70erne[The bathroom in the 1960s and 70s]. Internalworking paper. Herlev, Denmark: Max SibbernA/S.

Alt for Damerne [Everything for the ladies]. 1999. Is-sue 50, December 16, 1999, pp. 120–122. EgmontMagasiner A/S.

Bach, H., N. Christensen, H. Gudmundsson, T. S.Jensen, and B. Normander, ed. 2005. Natur ogMiljø 2005. Pavirkninger og tilstand. [Nature andenvironment 2005, effects and state]. TechnicalReport nr. 550. Roskilde, Denmark: National En-vironmental Research Institute of Denmark.

Badeland. 1996. Bo Bedre [Copenhagen] 3 March.Baderummet ændrer status [The status of the bathroom

is changing]. 2004. Hallo, Holbæk & Opland [Hol-baek] 9 October, 30.

A bathroom guide. 2005. www.abathroomguide.com/html/bathroom-design2-htm. Accessed January2006.

Bech-Jørgensen, B. 1994. Nar hver dag bliver hverdag[When every day becomes everyday]. Copen-hagen, Denmark: Akademisk Forlag.

Beck, U. 1992. Risk society—Towards a new modernity.First edition. London: Sage.

Bo Bedre [Live Better]. 1993a. No. 1 January 1993.Bo Bedre. 1993b. No. 2 February 1993.Bo Bedre. 1996a. No. 1 January 1996.Bo Bedre. 1996b. No. 3 March 1996.Bo Bedre. 2004. No. 2 February 2004.Bo Bedre A-Z. 2000. 1999–2000. No. 1/2000.

Boligkataloget Eksklusiv [Dwelling catalogue Exclusive].2004. No. 16 March/April 2004.

Boligmagasinet [The dwelling magazine]. 2003. No. 36February 2003.

Boligmagasinet. 2004. No. 49 March 2004.Bonke, J. 2002. Tid og velfœrd [Time and welfare]. Re-

port 02:26. Copenhagen, Denmark: Danish Na-tional Institute of Social Research.

Bulow and Nielsen. 2006. About products of standardhouse producer. www.bulownielsen.dk. AccessedJuly 2006.

Byggecentrum. 2004. Byg om & Forny [Renovate andrenew] [Denmark].

Byggecentrum. 2005. Byg om & Forny [Renovate andrenew] [Denmark].

Cadazzo. 1993. Bo Bedre, No. 2, February, 16.Campbell, C. 1987. The romantic ethic and the

spirit of modern consumption. Oxford, UK: BasilBlackwell.

Carlsen, J. M. 2005. Boomerangbørn: Ungerne venderhjem [Boomerang children: The young ones arereturning home]. Jyllands-Posten [Aarhus], 10 July,Section ‘Brunch,’ 4.

Christensen, T. H. 2001. Bolig, samlivsform og forbrug.Boligens brug og betydning for eneboende [Dwelling,living arrangements and consumption—Use andmeaning of the dwelling for singles]. Lyngby, Den-mark: Technical University of Denmark.

Cieraad, I. 2002. Out of my kitchen! Architecture, gen-der and domestic efficiency. Journal of Architecture7: 263–279.

Dencik, L. 1996. Familjen i valfardsstatensforvandlingsprocess [The family in the trans-formation process in the welfare state]. DanskSociologi 7(1): 52–82.

Eurodan. 2006. About products of a standard house pro-ducer. www.eurodan.dk. Accessed July 2006.

Familieliv i badeværelset [Family life in the bathroom].2003. Søndagsavisen/Region 2, 31 August.

Fielding, H. 1996. Bridget Jones’s diary. London: Pi-cador.

From, L. 2004. Genbrugspladser drukner i gamlekøkkener [Recycling stations are filled with oldkitchens]. Jyllands-Posten [Aarhus], 18 October,Section 1, 2.

Goffman, E. 1959. The presentation of self in everydaylife. New York: Doubleday.

Gram-Hanssen, K. 2007. Teenage consumption ofcleanliness: How to make it sustainable? Sus-tainability: Science, Practice, & Policy 3(2).http://ejournal.nbii.org. Accessed May 4, 2007.

Gram-Hanssen, K. and C. Bech-Danielsen. 2000. Ren-overing af enfamiliehuset. Holdninger til arkitek-tur og økologi [Renovation of the single family

204 Journal of Industrial Ecology

R E S E A R C H A N D A N A LYS I S

house—attitudes to architecture and ecology].Hoersholm, Denmark: Statens Byggeforskn-ingsinstitut.

Gram-Hanssen, K. and C. Bech-Danielsen. 2004.House, home and identity from a consumptionperspective. Housing, Theory and Society 21: 17–26.

Grey, J., S. Ardley, D. Hall, S. Katz, S. Gaventa, andB. Weiss. 1998. The complete home design book.London: Dorling Kindersley.

Grohe. 1970. Bo Bedre, No. 11, November, 103.Gullestad, M. 1989. Kultur og hverdagsliv. Pa sporet

av det moderne Norge [Culture and everydaylife—exploring the modern Norway]. Oslo, Nor-way: Universitetsforlaget.

Gullestad, M. 1992. The art of social relations. Essayson culture, social action and everyday life in modernNorway. Oslo, Norway: Scandinavian UniversityPress.

Hand, M. and E. Shove. 2004. Orchestrating concepts:Kitchen dynamics and regime change in GoodHousekeeping and Ideal Home, 1922–2002. HomeCultures 1, 235–257.

Hand, M., E. Shove, and D. Southerton. 2005. Ex-plaining showering: A discussion of the ma-terial, conventional, and temporal dimensionsof practice. Sociological Research OnLine, 10.www.socresonline.org.uk/10/2/hand.html. Acce-ssed January 7, 2006.