‘The city’ as developmental justification: claimsmaking on the urban through strategic planning...

Transcript of ‘The city’ as developmental justification: claimsmaking on the urban through strategic planning...

“The city” as developmental justification: claimsmaking on the urbanthrough strategic planning

John Lauermann*

Department of History, Philosophy, and the Social Sciences, Rhode Island School of Design,2 College St, Providence, RI 02903, USA

(Received 18 July 2014; accepted 10 March 2015)

Municipal governments produce a seemingly endless supply of urban strategic plans,which purport to define the city by making claims on its future development trajec-tories. Critics note that this claimsmaking on “the city” renders it conceptually vacuousand overextended. Yet it is essential to question the degree to which speculativepolicymaking is merely rhetorical. Discursive claimsmaking on the city throughstrategic planning documents is an important technique in urban politics—a form oftargeted simplification that benefits particular stakeholders by defining the city aroundsites in which they are invested. Bids to host sporting “mega-events” like the OlympicGames are a case in point: event planning corporations routinely make claims on thecity, which strategically simplify its forms and processes, often by defining the city inways that mediate between particular land investment projects and broad visions forcitywide development. The implication is that claimsmaking on the city through urbanstrategic planning is intentionally simplistic and acts as an ideological practice forjustifying urban development projects.

Keywords: strategic planning; discourse; performativity; urban land; mega-event

Introduction

Speculative long-term planning documents (e.g., strategy statements, urban “visions,”scenario planning, multidecade plans) have long been recognized as a means to definethe city of the present through strategic claims on its future (cf. Daffara, 2011; Shipley,2000). Core to this are oversimplified definitions of “the city,” which often describe it assingular and territorially discrete. These myopic references to “the city” and its futurenecessarily reflect policymakers’ political-economic commitments to, and ideological prac-tices in support of, local urban regimes (Addie, 2013; Olesen, 2014; Wachsmuth, 2014). Inaggregate this generalizes “the urban” in ways that echo older metanarratives of place like“the modern” or “the global” (Brenner & Schmid, 2014). Such attempts at defining cityidentity likewise evacuate its meaning, ontologically flattening “the word ‘city’, and con-cepts of ‘cityness’ [into] merely a sort of automatic reference in contemporary, entrepre-neurial and neo-liberal policy discourses” (Vigar, Graham, & Healey, 2005, p. 1406).

Yet however vacuous it may be, discursive claimsmaking on the city through strategicplanning documents is an important technique in urban politics. It is too simplistic tosuggest that policymakers are merely unable or unwilling to comprehend the definitionalcomplexities of the city. Nor are these visions of the city simply floating signifiers(Brenner, 2013, p. 90; Laclau, 2005, ch. 4), buzzwords deployed in support of any

*Email: [email protected]

Urban Geography, 2016Vol. 37, No. 1, 77–95, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2015.1055924

© 2015 Taylor & Francis

number of diverse political claims. Rather, strategic plans that define a narrow version ofthe city are a form of strategic simplification, by which nuance and complexity are tradedfor a targeted claimsmaking on urban resources. Strategic planning often defines the citywith reference to particular places within it—pilot projects, particularly successful ortroubled neighborhoods, zones subject to special legal or fiscal interventions—effectivelyallocating the right to define the city to the stakeholders who control those places.

In this sense the inevitable slippage introduced via simplified definitions of the city—the fact that cities are neither singular nor geographically self-contained, and that strategicplanning initiatives often fail to materialize—is something accounted for in advance. Thisslippage is produced in order to accomplish urban political work, as the above-mentionedvacuum is strategically refilled to facilitate special interest politics. Such streamlineddefinitions of the city are not intended to represent the broader city at all, but rather toarticulate a justification for local development narratives. In the case I explore in thisarticle, these narratives posit that urban development outcomes will “trickle out” geogra-phically from individual land investment sites to the broader city-region.

The implication is that critiques of hollow definitions of “the city” and “the urban”should shift emphasis. Many recent commentaries in critical urban theory have focused onshowing the territorial complexity of the urban: on showing that “the city” is actuallymultiple, relational, and unbounded. However, a closer reading of what policymakersaccomplish via simplistic definitions of the city signals a deeper layer of ideologicalpractice. These appeals to an oversimplified city are more strategic than myopic: policy-makers already know that they are presenting simplistic definitions of the city, and they doit anyway. Strategic claimsmaking on definitions of the city can be read as an ideological“category of practice” such that “its partiality helps obscure and reproduce relations ofpower and domination” (Wachsmuth, 2014, p. 76). The discursive simplification of thecity can be interpreted as a political-economic project that reinforces urban regimes bygeneralizing their development narratives, using “the production of solutions, explana-tions, and models that are universalizable; assembling diverse, dynamic arrays of parti-cular places, materials and people under capitalist regimes” (Lauermann & Davidson,2013, p. 1278). As such, analysis should not only deconstruct partial and flawed claims onthe city, but also probe why stakeholders pursue and benefit from those claims.

I contribute by tracing the political-economic dimensions of claimsmaking on “thecity” through an institutional analysis of these urban politics. The analysis that followscompares strategic planning initiatives around sports “mega-events.” Bids to host mega-events—especially bids to host Olympic Games, the largest such events in terms of costand footprint on urban landscapes—push the boundaries of urban policymaking reality.These bids offer long-term urban development strategies that promise far-reaching “lega-cies” on impossibly small budgets. Indeed, one comparative analysis of Olympic planningover a 50-year period finds that “every Games, without exception, has experienced costoverruns. . .in the Games the budget is more like a fictitious minimum that is consistentlyoverspent” (Flyvbjerg & Stewart, 2012, p. 11). The thinness of the bids is most apparentin the ways that bid corporations claim to represent “their” city: Olympic bidders routinelylay claim to their cities’ identities, marketing the city for a global audience through aseries of strategy statements and master plans. Yet like many uncomfortably abstractstrategic plans, these bids are important artifacts in urban politics. By articulating a visionfor the future Olympic city, bidders strategically simplify and redefine it, and mobilizeurban resources in the process.

In the following case I show that bidders’ references to their Olympic city arestatements about capacity. When a “city” is said to bid to host the Games, the bidding

78 J. Lauermann

corporation is often making a statement about its capacity to mediate between thespecifics of urban land investment projects and the abstractions implied in rhetoricpurporting various forms of event-led development. While the various branding strategiesand boosterish rhetoric that bidders employ necessarily refer to the city quite abstractly,the actual work of bidding requires planning corporations to leverage particular landinvestment sites. These sites become testing grounds for the aforementioned statement ofcapacity. Abstracting from plans for particular sites to claims about event-led developmentin the city is likewise a useful political maneuver, in that bidders are able to lay claim oncitywide governance challenges.

Interrogating “the city”

The rise of urban strategic planning paralleled the spread of neoliberal governancetechniques (see reviews in Healey, 2006; Olesen, 2014; Shipley, 2000), as state decen-tralization shifted long-term planning responsibilities onto urban stakeholders, and aspublic–private planning initiatives adopted the rhetoric of corporate strategic planning(Harrison, 2010; McCann, 2001). As such, strategic planning initiatives are often inter-twined with a broader political economy of urban branding, in which place marketing—asa general promotional strategy—was replaced by a more targeted form of place branding,“the self-conscious application of branding to places as an instrument of urban planningand management” (Kavaratzis & Ashworth, 2005, p. 507). In this way the brand comes topermeate definitions of the city. This “harder” form of branding marks an attempt to“extend brand life, geographically and symbolically. . .transform[ing] essentially privateconsumer products into places of collective consumption” (Evans, 2003, p. 417) through-out the city.

Critics have noted the irony of this fusion of neoliberalization practices and state-ledplanning, attributing it to a form of “roll-with-it-neoliberalization” (Keil, 2009) by whichstrategic planning practices mirror broader entrepreneurial governance logics in “seekingto install economic growth and competitiveness as common-sense policy objectives”(Olesen, 2014, p. 289). Others, especially comparative and Global South urbanists, havesuggested that this shift to “neoliberal” strategic planning indicates an inherently contra-dictory—and increasingly common—politics of using neoliberal practices (e.g., urbanbranding, municipal financialization) to facilitate state-led development initiatives (Parnell& Robinson, 2012; Roy & Ong, 2011). The empirical case that follows engages with thiscontradiction, delineating the parallels and (dis)continuities between entrepreneurial urbangovernance and state-led developmentalism.

Strategic planning documents—with their glossy, boosterish claims on the city’s future—are one method to accomplish this extension of urban brand from sites to city. Thepolicymaking tools associated with those strategies (templates, models, guidelines for bestpractice, etc.) are an important currency in constructing a city’s identity, as policymakers“sell” their expertise outside the city to build extra-local legitimacy in support of localprojects (Lauermann, 2014a). The point is that promoting the urban brand to localconstituencies is often accomplished by disseminating the same policy tools that areproduced by strategic planning, through extrospective “policy boosterism” by localauthorities in global knowledge circuits (McCann, 2013), city-to-city “policy tourism”by technocrats learning from each other (Cook & Ward, 2011), or “diplomatic entrepre-neurship” between municipal governments (Acuto, 2013, p. 490). This is seen promi-nently in bidding to host Olympics and other mega-events, a planning process that fusesstrategic planning (for the future event) with place branding (of the city for a global

Urban Geography 79

audience). The “Barcelona model” is a quintessential case (González, 2011): the planningmodels associated with the city’s regeneration efforts during and after the 1992 Olympicsare an important tool by which municipal leaders market themselves and the city.

The implication of making urban policy by promoting an urban brand is that the brandrequires a relatively coherent identity which can be owned and traded. Yet consolidating itrequires a hollowed-out definition of the city: a degree of parsimony is necessary forarticulating any brand’s identity, and simplified definitions of the city open up opportu-nities for including and excluding members who might benefit from it. Entrepreneurialclaimsmaking on “the city” thus often has the effect of evacuating meaning. One reviewof references to “the city” in strategic planning documents finds them vacuous, and notesthat the void provides a space for entrepreneurial governance maneuvers:

the concepts of the “city” that are invoked, reworked or constructed—either intentionally orunintentionally—tend to rely on a diffuse and extremely flexible series of iconic andhistorically grounded notions of cityness. While such discourses rely on the interpretiveflexibility that the word “city” clearly displays, the uses of the word become so loose anddiffuse that any real meaning rapidly evaporates. Thus the word “city”, and concepts of“cityness”, become merely a sort of automatic referent in contemporary, entrepreneurial andneo-liberal policy discourses. (Vigar et al., 2005, p. 1406)

Thus references to the city or the urban are conceptually hollowed out and geographicallyoverextended. As Brenner has repeatedly lamented in recent critiques of loose referencesto the urban, “in the early twenty-first century, the urban appears to have become aquintessential floating signifier: devoid of any clear definitional parameters, morphologi-cal coherence, or cartographic fixity, it is used to reference a seemingly boundless range ofcontemporary sociospatial conditions” (Brenner, 2013, p. 90). Indeed, ubiquitous invoca-tion of the city produces a narrative in which

The urban age appears, in short, to have become a de rigueur framing device or referencepoint for nearly anyone concerned to justify the importance of cities as sites of research,policy intervention, planning/design practice, investment or community activism. Much likethe notion of modernization in the 1960s and that of globalization in the 1980s and 1990s, thethesis of an urban age appears to have become such an all-pervasive metanarrative that earlytwenty-first century readers and audiences can only nod in recognition as they are confrontedwith yet another incantation of its basic elements. (Brenner & Schmid, 2014, p. 734)

This line of critique parallels a lineage of critics who contest simplistic ontologies of thecity by highlighting the territorial complexity of the urban: even within a relativelypragmatic arena like urban policymaking, “the city” can be neither discrete nor singularbecause urban governance is assembled from diffuse sources (Allen & Cochrane, 2014;Harrison, 2010; McCann & Ward, 2011) and mediated through regionalized coalitions(Cox, 2011; Soja, 2011).

While this territorial complexity critique has become paradigmatic, less is knownabout the political logics that belie this complexity:

the permeability of city boundaries. . .is now more or less taken for granted. That tightterritorial boundaries are rarely what they seem, however, has not diminished their signifi-cance as meaningful political entities through which institutional actors—from councils tomayors, chief executives to social workers, town planners to local community associations—define their day-to-day political practice. (Allen & Cochrane, 2014, p. 1610)

80 J. Lauermann

Indeed, in a recent critique of Brenner’s above-mentioned argument, Scott and Storperargue that while “the urban” label is undoubtedly overextended, this overextension doesnot erase the deeper political economies that define urban politics:

we still need to assert the status of the city as a concrete, localized, scalar articulation withinthe space economy as a whole, identifiable by reason of its polarization, its specialized landuses, its relatively dense networks of interaction. . .the city is to the space economy as amountain is to the wider topography in which it is contained. In neither the case of the citynor the mountain can a definite line be drawn that separates it from its wider context, but inboth instances, certain differences in intensity and form make it reasonable. . .to treat each asof them as separable entities. (Scott & Storper, 2015, p. 7)

Thus the critical question is not only “in what way” is the city label misused, but also“why.” Urban political work is accomplished through simplification: it is not simply anevacuation of meaning to render “the city” into a floating/empty signifier (Laclau, 2005,ch. 4) but also an ideological politics of reinscribing political-economic meaning into it(Davidson, 2010).

Vacuous though they may be, references to “the city” in strategic planning are none-theless powerful ideological tools that signal deeper development practices. Analyzing the“metropolitics” of regional policymaking identity, Addie (2013, p. 209) notes that“rescaled spatial imaginaries. . .can galvanize the collective agency of ruling elites at thecity-region scale.” Wachsmuth (2014, p. 77) goes further still, arguing that references tothe city function as a category of political practice, such that “the city is an ideologicalrepresentation of urbanization processes rather than a moment in them.” Attempts atdefining the city through speculative policy statements are performative: even thoughclaims about “the city” overlook its complexities, the act of overlooking serves to boundthe horizon of urban political conversation. For example, even though “smart city” modelsmay entail more technocratic vision than urban reality, the “labeling process” (Hollands,2008, p. 304) that policymakers use to define their city as “smart” has a self-reinforcingquality. Indeed, the simplified definition of a smart city as a series of technologicalsystems, and the role of corporations who sell those systems, relies on an “ontologicaltransformation” of the city, which is “the source of the model’s epistemological power. . .this transformation spares us the difficulties of interpretation: translated into data andsystems, the city seems to speak by itself, to be self-explanatory” (Söderström, Paasche, &Klauser, 2014, p. 314).

Thus strategic documents facilitate urban development trajectories not only in spite of,but also with assistance from, their conceptual thinness. As I document in the followingcase, elements of strategic plans like Olympic bids are often implemented even if theoverarching strategy is unsuccessful. This occurs both because they reflect existing logicswithin urban development regimes and because they establish new path dependencies forsubsequent policymaking. In the discussion that follows, my concern is with the politicalwork accomplished when Olympic bidders make claims on “the city” by designingstrategic visions for it through planning models, strategy statements, and event masterplans. Writing a bid is not so much an exercise in defining a city, but rather in definingwhat a city can do to deliver the bidders’ development agendas. An Olympic bid isperhaps best interpreted as a statement of capacity: claiming a mandate to re-vision thecity through individual land investments. As later cost overruns, construction delays, andpolitical contestations usually reveal, these claims are far from assured. However, strate-gically simplifying the city in this manner links particular land investment projects tobroader narratives about event-led development.

Urban Geography 81

Interrogating the Olympic “city”

Bids as strategic claimsmaking

Bidders’ claims about the types of urban development that they can deliver—and aboutthe type of city that is envisioned—present a narrow definition of “the city” extrapolatedfrom a small number of land investment sites. When bid planners simplify complexplanning questions through glossy urban visions, they are presumably aware of the scalarand sectoral complexities involved when a “city” hosts the Games. An Olympic hostingcontract must be signed by a municipal government, but Olympic projects rely onplanning coalitions that are intentionally multisector (often represented by a series ofpublic–private partnerships) and multiscalar (drawing selectively on transnational net-works of finance and expertise, while leveraging resources at the scale of the city-region).One consultant, whose clients are primarily municipal governments bidding to host mega-events, emphasized a constant attempt to simplify the city:

An event is kind of the opposite of how a city works. An event is short term: a high impact,high cost short term. And of course the city can use that in its long term development. But anevent is a project; cities are run by processes. An event is short term; cities are long term. Anevent is unstable but interesting; cities are all about stability. So the interesting thing is how tomerge the two parts: projects and processes. And that’s where strategic planning comes infor us.1

Thus while bids present visions of the host city that could easily be critiqued as vacuousand boosterish, those visions are designed to facilitate a political-economic project: theyleverage definitions of the city in largely the same way, using them to link particular landinvestment projects to broader development narratives. Bids reflect (and are often a meansfor formalizing) pre-existing local development strategies and often have long-termimplications as catalysts for speculative policymaking and investment. Bids are, further-more, legally binding documents that outline obligations if a bidder wins a hostingcontract. Indeed an International Olympic Committee program officer described theorganization’s city monitoring teams as “guardian[s] of what has been promised in thebid,” tasked with maintaining the scale and quality of infrastructure investment initiallypromised by bidders.2

Strategic visions articulated in these bids are typically statements about capacity:capacity to mediate between specific land investment projects and abstract rhetoricalclaims about event-led development agendas. The former are often detailed site plansand clear business models; the latter are amorphous goals like “regeneration”(González,2011), “sustainability” (Davidson, 2013), “social inclusion”(Edelson, 2011), or “pro-poordevelopment” (Pillay & Bass, 2008). Olympic land investment projects are often dis-cussed as urban experiments: testing grounds for the aforementioned statement of capa-city. This abstraction from plans for particular sites to claims about event-led developmentis a useful political maneuver, in that bidders are able to lay claim on citywide governancechallenges.

These strategic planning exercises have impacts beyond the immediate context ofbidding. Final outcomes will inevitably diverge from the original plan. The impact withwhich I am concerned is, rather, the politics of defining the parameters of urban devel-opment intervention in the first place. Specific elements of bids may or may not berealized in the long term, but they are effective in creating path dependencies in urbanpolitics: First, bidders construct interurban coalitions along the way (Cook & Ward, 2011;González, 2011; Surborg, VanWynsberghe, & Wyly, 2008), often mobilizing them for

82 J. Lauermann

future Olympic and non-Olympic mega-project planning. In fact individual bids for amega-event are relatively rare: strategic planning is typically a long-term project involvingmultiple bids for multiple types of events, allowing planning coalitions to construct partsof broader urban strategies along the way (Lauermann, 2014b). Second, bid plans areoften realized to some degree regardless of success or failure in actually securing a hostingcontract, a phenomenon observed through case studies in Berlin (Alberts, 2009), Doha(Scharfenort, 2012), Istanbul (Bilsel & Zelef, 2011), New York (Moss, 2011), and Toronto(Oliver, 2011).

A comparative review of Olympic bids provides an empirical starting point to interpretwhat bidders’ claims about “the Olympic city” entail for the places incorporated into astrategic planning exercise. In a formal, legal sense, Olympic bids are designed by “bidcommittees,” temporary entities (typically a limited-life corporation or nonprofit organi-zation) tasked with gathering political support, securing sponsorships and developing abusiness model, designing site plans and venue architecture, and writing the bid proposal.Each bid is unique, but a mixed-methods comparison highlights the interdependenciesbetween the types of institutions involved in strategic planning and the ways in which bidcommittees articulate definitions of “the Olympic city” (Table 1). This provides insightinto the political practices of claimsmaking on the city by exploring the ways throughwhich particular sites come to stand in—discursively, institutionally, and in policy—forthe broader city-region.

I compare bids over a 20-year period: 44 bids representing 31 cities to host SummerGames between 2000 and 2020 (the bid competitions date from 1991 to 2012).3 Analysisfocused on the type of institutions involved when a “city” bids to host the Games, and theimpact of these institutional configurations on the planning visions which bidders articu-late. A qualitative content analysis of the bids assessed how bidders discuss their cities:what they claim the city can deliver in support of event-led development projects andwhat they claim the event can deliver for the city.

Bidders’ engagements with “the Olympic city” occur on a spectrum of relevance inhow it—as a place—impacts their broader development agendas. (1) At one extreme, the

Table 1. Indicators for evaluating Olympic city visions.

Definitions of the “city” (qualitative contentanalysis)

Qualitative themes: bids discuss “the city” as anasset (10 bids) or opportunity (12 bids) forurban growth coalitions, or as a microcosm fornational ambitions (15 bids) or an experimentalsite for testing and up-scaling policy (sevenbids)

Bid characteristics (discriminant analysis)Institutions: bid sponsor, guarantor, and leaddeveloper

The type of institutions that fund the bidcommittee, guarantee the planning corporationin case of cost overruns, and own/finance theproposed Olympic Village project (typicallythe largest single land investment in anOlympic bid)

Investments: Bid corporation finances,proposed capital investments, overlap withother mega-events

Proposed investment on transportation projects,sports-specific infrastructure, and theirrespective ratios; % of capital investments thatis specific to the Olympic plan; bid committeeoperating budgets; related mega-event bidswithin 10 years of the bid date

Urban Geography 83

city is discussed in terms of opportunity for urban growth: for example to “raise Madrid’sprofile as the leading city of the Hispanic world. . .[and] to help develop a city model forsocial co-existence and inclusiveness that other cities can learn from” or to “contributefocus as no other single event can, to the transformation of Cape Town. . .transformation atthis depth and breadth is the sine qua non of South Africa’s peaceful transition todemocracy.”4 (2) Moving towards a more passive vision of the city, other bidders defineit as containing a set of assets that urban growth coalitions could leverage for their ownends. While the first group focuses on what the event can do for the city, these biddersfocus on how the event can leverage the city: for example an athlete’s housing complexbecomes “One of the last sites in Paris still to be redeveloped, it will become a newquarter of the French capital—the ‘Olympic quarter’—and a new benchmark of sustain-able development” or, when taking place “at the centre of a city [Tokyo] which is a matureyet always evolving big city. . .we can demonstrate to the world how a city can stepforward into the future while preserving assets from the past.”5

Both of these framings are typically designed by urban-scale stakeholders, while twoother framings are more often articulated by national stakeholders making claims on thecity. In these latter two framings the city—as an actual place—is less relevant in bidders’discourse, and is articulated instead as a site that might receive external intervention. (3) Anumber of bidders discussed the city as a site for testing and exporting developmentpolicy from the urban to the national: thus “[u]sing the Games as a catalyst, Baku aims tobe the leading city and benchmark on sustainability for the Caucasus region, and widerCentral Asia” or perhaps “the IOC [International Olympic Committee] and Doha have thechance to impact positively across a much wider social and cultural landscape. . .[as] thecatalyst for progressive change across the Middle East and North Africa region. . .openingup the Middle East to the Olympic Games also means opening up new markets.”6 (4)Finally, at the other extreme of the spectrum, “the city” does very little in governanceterms. It functions instead as a microcosm for the national state to realize its ambitions: forexample “İstanbul’s approach. . .transforms the entire city to a stage. The Games will beplanned and delivered as a key element of the existing 2023 Master Plan for Turkey. . .This will be the model for the extended rollout of the National Sports Plan. . .creating anetwork of new aspirational communities that promote and incentivise healthy living.”7

These four themes were compared against institutional characteristics of each bidcommittee with discriminant analysis, a commonly used technique for assessing non-linear, mixed qualitative/quantitative data.8 The characteristics were chosen to assess thetypes of stakeholders who participate in defining the Olympic city: those who lead orfinance bidding projects, and the scale and scope of the proposed budgets. All four themescorrelate with distinct institutional characteristics, but one vector in the data set wasespecially clear. This function suggests a statistically significant trend based on whethera municipal or national government is driving the bid, the magnitude of the land invest-ments posed in the bid, and the degree to which those investments are specific to theOlympic project (or part of related but independent infrastructure investment programs).9

Thus a simplified model was constructed by regrouping the bids into two qualitativecategories at the ends of the spectrum: the city as a local growth coalition project or as anexperimental site for national states (Table 2). Institutionally, the difference depends on thepublic-sector frugality (or lack thereof) in a given Olympic bid. (1) In growth coalitionprojects, municipal governments often play a dominant role, occupying senior managementroles in public-private bid committees, guaranteeing financial shortfalls with municipal funds,or leading Olympic Village housing projects (often owning and financing the project out-right). Bids that discuss the city as a growth coalition project have smaller total infrastructure

84 J. Lauermann

budgets (capital investment of $8.4 billion per bid on average, as opposed to $10.2 billion) butdevote a larger share of that to event-specific projects (62.4% of bid budgets on average, vs.43.9%). Both signal to a strategic integration of existing land assets into the event businessplan, minimizing investment in projects that are not specifically necessary for hosting theevent (this entails, especially, fewer transportation projects). (2) In the second group, nationalstate institutions play a dominant role, almost always sponsoring the bids, guaranteeingfinancial shortfalls, and taking responsibility for Olympic Village investments. Despite havinglarger total infrastructure budgets, less is planned specifically for the event, as the biddersclaim marginally relevant infrastructure investments on their balance sheets (often transporta-tion mega-projects: 56.5% of the bids’ capital investment budgets, as opposed to only 38.82%of the budgets proposed by the first group of bids). These bids are often used as a means tocatalyze subcomponents of broader national development strategies as part of a long-terminvestment portfolio (on average, they are linked to twice as many bids for other mega-eventsas the first group).

While there are a number of compelling cases that would deepen this comparison, forbrevity I focus on two in the discussion that follows. In the first (a failed bid to host the2012 Games in New York City) I show how urban growth coalitions leveraged strategicvisions of an Olympic city in order to integrate the Olympic plan with ongoing real estateprojects. In the second (a series of successful and failed bids to host a variety of mega-events in Doha) I document the ways in which the national state used mega-event bids topursue developmental agendas, relying on visions of the city as a set of experimental sitesfor testing policy. The cases were chosen as particularly pronounced examples of twostrategies discussed above. They highlight the urban political work that is accomplishedthrough speculative claimsmaking on the city at the early stages of strategic planning (thusboth emphasize bids that failed, but still had policymaking impacts). The patterns thesecases illustrate neither are mutually exclusive nor do they represent the full spectrum ofpossibility. But the cases draw out qualitative distinctions between bids that help explainwhy bidders’ institutional compositions lead them to particular types of claimsmaking ontheir respective cities.

Table 2. Comparison of bidders’ visions of their “city.”

Bidders discussed the city as. . .

Growth coalition projectExperimental site for

national states

N 22 22Most common bid sponsor* Municipal governments National governmentMost common shortfall guarantor* Municipal government National governmentMost common Olympic Villageowner

Municipal government or for-profit firms

National government

Bid writing budget 34.46 32.99Total capital investment* 8447.55 10217.4Event-specific capital investment* 3361.27 2231.82Number of related bids/eventswithin 10 years

0.86 2.05

Notes: Based on 44 bids from 31 cities to host the Summer Olympics, 2000–2020 (bids date 1991–2012).Investment amounts are mean per bid, standardized to USD 2012 million. *Significant discriminating variable at90% confidence.

Urban Geography 85

“The city” as a growth coalition project

In the first framing, the Olympic “city” is discussed as a project for growth coalitions: acollection of geographic sites that can be leveraged or that require intervention. Thisdefinition of the city brings particular sites to the policymaking foreground, to the benefitof bid coalition members and the detriment of others. For most of these bidders, eventplanning thus provides a platform for two strategies of claimsmaking on the city:describing “the city” in ways that demonstrate municipal governance opportunities (andlocal capacity to pursue them), or describing it as possessing a set of assets to be claimedby various stakeholders in a growth coalition. Both abstract from particular urban sites tobroad claims on the urban, by casting individual projects as crucial to solving citywidegovernance problems.

Drawing on urban regime theory (Burbank, Andranovich, & Heying, 2002; Cochrane,Peck, & Tickell, 1996), urban studies scholarship has long highlighted the role of mega-event planning in the portfolios of entrepreneurial urban governments. In their frequentlycited commentary on “mega-event strategy,” Andranovich and colleagues (2001, p. 127)describe this dynamic as one in which

City leaders see the Olympic Games in strategic terms, providing opportunities to gainregional, national, and international media exposure at low cost. Even submitting a bidpackage to the national Olympic committees is enough to warrant media exposure andprovide some claim to Olympic symbols to unify disparate stakeholders, however transitorythese claims might be.

That is, mega-event bidding and hosting are integrated into a growth coalition’s entrepre-neurial portfolio, especially by catalyzing local land investments (Andranovich &Burbank, 2011; Lauermann, 2014b). This is not to say, however, that the city is definedsolely in local terms. These bidding coalitions are often strategically multiscalar; theVancouver 2010 planning coalition, for instance, formed a “selectively transnationalizedlocal growth machine: its primary function [was] to balance the traditional political powerof locally-based growth coalitions with the need to respond to extra-territorial actors andcoalitions” (Surborg et al., 2008, p. 342).

Attempts to define “the city” as a growth coalition project were seen prominently in afailed bid on behalf of New York City to host the 2012 Olympics. The use of mega-eventsto politically abstract from site planning to citywide governance has a long history in NewYork. The city’s infamous modernist planner, Robert Moses, chaired the planning cor-porations of the 1940 and the 1965 World’s Fairs (cf. Caro, 1974, ch. 37). Locating theseevents at a single site in the quasi-suburban borough of Queens provided a geographicalcenter for his planned metropolitan highway system. Placing these events at a new“geographical and population center of New York” allowed Moses to define a moresuburban city, connected through auto networks (Figure 1).10 The effect was to shiftinfrastructure spending towards the suburbs by securing a $95 million highway expansiongrant ($760.9 million in 2014): widening and extending four highways was financed bythe federal-level (90%) and state-level (10%) governments, with the municipal govern-ment purchasing $700,000 of land for the project ($5.6 million in 2014 dollars).11

Thus the general principle of using a mega-event to invest in sites, and using thosesites as an opportunity to articulate claims on “New York” more broadly, was a familiarpractice when NYC 2012, Inc. planned its Olympic bid (from 1994 to 2005). The bidcorporation linked a broad vision of “the Olympic city” with particular land investmentprojects, all of which were owned by various bid coalition stakeholders. The bid focused

86 J. Lauermann

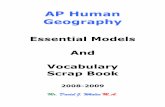

on the redevelopment of post-industrial sites, along the East and Hudson river waterfrontsand in “the yards,” rail-yards at the ends of subway lines which could be downsized and/or covered by overlying construction. The bid corporation linked these redevelopmentsites to a broader urban vision of increased cross-city connectivity via public transporta-tion. They branded this master plan as the “Olympic X,” a design concept in whichinvestment sites were planned over diagonally intersecting major subway corridors(Figure 2).

Politically, this accomplished two goals: First, the X-based vision for the city was ableto capitalize on long-term, but largely stalled, redevelopment projects. Each of the fivemain sites (one in the center and one at each terminus of the “X”) represented assets thatgrowth coalition stakeholders could mobilize through Olympic bidding. Each project hadpreviously stalled, and the Olympic bid was a means to finalize site plans and line up

Figure 1. Robert Moses’ vision for a more suburban city, centered on the World’s Fair.

Source: New York World’s Fair 1964–1965 Corporation (1960, p. 12).

Urban Geography 87

financing. The bid provided an impetus to draft new site plans and form several newmunicipal economic development corporations. For example, the bid corporation foundeda redevelopment coalition in support of its “Hudson Yards” project on the lower west sideof Manhattan. Within months the Mayor’s office asked the bidders to take over sitedesign; the bid committee fundraised and spent over $500,000 to redesign the entire 30-block zone.12 After the Olympic bid failed, the City quickly moved to formalize thecoalition through a public–private redevelopment corporation for the site.13

Second, the X-based vision for the city strategically abstracted away from the urbanlandscape to prioritize individual sites. Sites off of the X were not eligible for inclusion inthe strategic plan. For example, in one particularly contentious city planning meeting aseries of conflicts arose between the bid’s executive director and four separate city councilmembers, all protesting that potential sites in their districts had been excluded from thebid master plan. One council member, speaking about a potential gymnastics facility inHarlem, argued that “for ten years I’ve been preaching [the virtues of this site] and nowwe have this golden opportunity to see my dream come true, if you will, and you’veignored me.”

As with all three of the other dissenting council members, the bid director was able torebuff the critique by arguing their districts were not located on the Olympic X: “thedilemma of the Olympic bid is that it is a golden opportunity to do extraordinary thingsfor the city, but not to do everything. . .[your site] doesn’t work from a transportationstandpoint, and we are going to be rigorous in not violating the integrity of the bid.”14

As this conflict over site selection highlights, the process of abstraction from sites to“city” empowers growth entrepreneurs to substitute their real estate projects for broader

Figure 2. NYC2012, Inc vision for an “Olympic X.”

Source: NYC2012 Olympic Candidature File (2004, vol. 2, pp. 14–15); image provided by the Cityof New York Department of Records.

88 J. Lauermann

narratives of urban development. The original site selection was driven by the need toenroll bid coalition members, and subsequent technical requirements implied in thestrategic plan precluded broader conversations on city-scale development priorities. Inthis way the coalition members who controlled major real estate investments effectivelymonopolized the definition of “New York” in the strategic plan, through the transportimperatives which their sites built into the master plan. After the Olympic bid failed, thesesame growth entrepreneurs were able to implement many of their plans after havingsuccessfully convinced the city government to extend subway lines to the sites (Moss,2011). Thus in this first framing—the city as a growth coalition project—claimsmaking onthe city is conducted by building a strategic plan around existing coalition projects, andusing “the city” to define citywide governance challenges through those particular sites.

“The city” as an experimental site for national states

A second group of bids envision the “city” as a site for experimenting with nationaldevelopment planning. In this framing, the city is defined with reference to a series ofenclaves, established to address particular national development objectives. These enclavesare articulated through two overlapping development narratives: the Olympic city as amicrocosm into which the national state can downscale itself, or as an urban laboratory(Karvonen & Van Heur, 2014) for testing and subsequently upscaling policy from the city.In the latter framing, enclaves are discussed as sites for experimentation, used to producegovernance innovations rather than simply test national programs on a limited scale.

This type of national-to-urban policymaking is well documented: in an era of statedecentralization, urban spaces figure prominently in state spatial strategies (Brenner,2004) although the degree to which this reflects a will to decentralize or simply a lackof capacity to reach all of state territory is contested (Cox, 2009). Commentators on theoutsized role of national states in ostensibly urban-scale mega-events have noted thedivergence between this model and the growth coalition projects discussed previously,suggesting that the former is tied to a more diverse, non-Western geography. Müller notes,for instance, that Russian Olympic planning in Sochi “embodies a distinct model of statedirigisme that accords primacy to the national state, challenging conventional accounts ofstate rescaling and urban entrepreneurialism” (2011, p. 2092). These scholars note that, fornational planners, the political agendas of local boosterism, place competition, andentrepreneurial rent-seeking do not necessarily apply. Rather, these initiatives oftenparallel broader attempts by “developmental states” to reterritoralize themselves throughcities (Olds & Yeung, 2004; Parnell & Pieterse, 2010). For instance, Black and Peacockhave argued that in the context of East Asian “strong state” mega-event planning models,

a different kind of calculus of costs and benefits has applied in these cases, tied not to a morenarrowly economistic or material calculation of projected gains (however illusory these maybe in practice) but to a longer-term and more symbolic calculus of repositioning and re-imagining the country in the global hierarchy of states. (2011, pp. 2271–2272)

Mega-event planning in Doha (Qatar) exemplifies the articulation of the city as a series ofsites for national experimentation. Recent projects have included two unsuccessful bidsfor the 2016 and 2020 Olympics, along with hosting the 2005 West Asian Games, 2006Asian Games, 2011 Arab Games, and preparing to host the 2022 football World Cup.Mega-events figure prominently in national development planning (Scharfenort, 2012)and the Olympic bids were governed by five national strategic plans that focus on

Urban Geography 89

growing knowledge economies and green (especially solar) energy industries.15 TheQatari state relies heavily on real estate ventures to pursue developmental agendas:“establishing and funding publicly owned real estate companies, which are in turn taskedwith carrying forward multiple projects of modernity as defined by the state” is central toimplementing these national development strategies (Kamrava, 2013, p. 148). The resultis a patchwork of enclave development projects, “self-contained ‘cities within the city’”(Salama & Wiedmann, 2013, p. 84) under the direction of individual ministries or state-owned corporations, each focused on a particular policy goal (Figure 3).

Figure 3. State-led real estate projects in Doha.

Source: Constructed from Olympic bidding archives, fieldwork, and academic commentaries(Kamrava, 2013; Salama & Wiedmann, 2013).

90 J. Lauermann

Given the institutional and functional territorialization of these enclaves, national strategicplans are often designed to incorporate them, rather than the other way around. As a plannerwho advised multiple Doha mega-events and the national sports master plan put it,

There’s one set of plans in each place [enclave site]; there’s random stadiums and sportsclubs. So it’s kind of an organic growth, right? With no master plan. Then you arrive atsomething like the [2006] Asian Games, and people like us—globally-oriented designers—start redesigning the master plans but you can’t move the stadiums. In the case of Al Rayyan[the main Asian Games site] a lot of the venues for the Asian Games were completelytemporary and had to be designed from scratch. So you had to do a master plan around thisinitial organic growth. So over time this Al Rayyan site has changed, and changed, andchanged.

Each enclave site is thus relatively efficient at accomplishing the goals of the agency orstate-owned corporation in charge of its direction (e.g., the Al Rayyan site has beenrepurposed into a sports academy for elite athletes, and has anchored many subsequentmega-event bid plans). However, between enclaves

There’s no grand plan, and when we came to do the [2011 national] sports master plan wetook the sites and we re-planned, we re-master planned to make it work. In reality we saidyou need to demolish this, demolish that. . .but we were confronted by people who said“absolutely no way”. So all these things are happening, again, organically, with no masterplan even though there is a master plan.16

The enclaves are thus strategically integrated into a broader strategy for articulating Doha asa site for governance innovation: Olympic bidders, for instance, argued that their planningwould ensure “Doha will become a regional model for informed modernisation and newdevelopment.”17 The focus on enclaves frames the city as a series of urban laboratories inwhich real estate projects are used to test (trans)nationally relevant policy objectives, andexport the results. For example, the Qatar 2022 World Cup planners based their 2010 bid ona modular solar-powered stadium design concept. Contracts for these technologies wereawarded to firms based in the Qatar Science and Technology Park and “Energy City”enclaves, managed by the Qatar Foundation (a parastatal endowment) and Qatari Diar (asubsidiary of the sovereign wealth fund), respectively. Modular components from the nineWorld Cup stadiums will be used to construct 22 stadiums elsewhere, as part of the Qataristate’s international development aid packages (FIFA, 2010).

This case highlights the strategic dimension of abstraction from sites to “the city”: whilethe developmental enclaves are geographically in the city (or, more often, at the suburbanedge) they are functionally discrete territorial entities. In this way “Doha” comes to be definedas a passive ecosystem that hosts national state initiatives; indeed, many of the enclaves arefunctionally separate gated communities—“self-contained ‘cities within the city’” (Salama &Wiedmann, 2013, 84)—which are more proximate in institutional terms to (trans)nationalgovernance debates and policymaking communities. But this form of claimsmaking on thecity is effective in implementing the proposed land investments: construction has continuedon most of the enclaves planned around Doha’s mega-event bids, regardless of their finaloutcomes. And the success of national development initiatives is ultimately dependent on thesuccess of the enclaves as urban neighborhoods. Thus in this second framing—the city asexperimental site for national governance—claimsmaking on the city is a multidirectionalscalar politics: there is a top-down relationship between national and urban, but urban sitestake on political and policy significance at multiple scales.

Urban Geography 91

Conclusion

Urban policymakers produce a steady supply of strategic planning documents, makingproblematically simplistic claims on “the city” by defining its future. This has the effect ofontologically flattening the city as a policymaking space, as claims about particular sitesare extended conceptually to construct more generalizable governance narratives. Theresult is a vacuous definition of “the city” (Vigar et al., 2005) and an overextension of “theurban” to that of a floating signifier (Brenner & Schmid, 2014), practices that are routinelydeconstructed by urban theorists (e.g., Allen & Cochrane, 2014; Brenner, 2013; Harrison,2010; McCann & Ward, 2011; Parnell & Robinson, 2012; Roy & Ong, 2011; Scott &Storper, 2015; Wachsmuth, 2014).

But yet these claims on “the city” play a significant role in urban governance: suchsimplifications are often strategic, defining the city narrowly around particular urban sites,allocating claims on “the city” to those who control the sites. Strategic policy documents—and the thin definitions of the city they articulate—are a tool for linking plans forparticular sites to claims about citywide governance. In the case of Olympic bids, thismaneuver is attempted when strategic planning documents make statements about thecity’s capacity to mediate between specific urban land investment and broader goals forevent-led development.

There remains much to be discussed about the city as a politically constructedterritory, and about claimsmaking on “the city” as an ideological process of territor-ialization. It is certainly necessary to deconstruct discourses that oversimplify the city’sterritoriality, but “we still need to assert the status of the city as a concrete, localized,scalar articulation” (Scott & Storper, 2015, p. 7). The fact that “tight territorialboundaries [of the city] are rarely what they seem…has not diminished their signifi-cance as meaningful political entities through which institutional actors…define theirday-to-day political practice” (Allen & Cochrane, 2014, p. 1610). My contribution tothis project—of analyzing the ideological practices and institutional actors that driveattempts at defining the contemporary city—can be summarized in two points. First,there is an empirical impact of claimsmaking on the city despite (or perhaps becauseof) the conceptual limitations of those claims. Speculative claimsmaking on the city isundoubtedly simplistic; yet strategic planning has material effects on urban develop-ment as it formalizes pre-existing projects, as parts of strategic initiatives are recycledin subsequent policy, and as “failed” policymaking experiments establish political pathdependencies. Second, the simplified visions of the city articulated through future-oriented planning serve an ideological purpose: they are a form of strategic simplifica-tion to the benefit of particular political economic interests. As such, urban theorycritiques should both deconstruct vacuous, overextended definitions of the city, andassess the political-economic interests of those who mobilize those definitions.

AcknowledgmentsMark Davidson, Kevin Ward, and Seth Schindler provided helpful feedback on the paper, as didRichard Shearmur and two anonymous reviewers.

Disclosure statementNo potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

92 J. Lauermann

FundingThis work was supported by the National Science Foundation (Doctoral Dissertation ResearchImprovement Grant [#BCS1333402]) and the International Olympic Committee (PostgraduateResearch Fellowship Programme).

Notes1. Interview with CEO of a Swiss mega-event planning consultancy, June 2014.2. Interview with IOC host cities program officer, August 20133. Bidding materials and institutional records were obtained from archives of sports federations (the

US-based LA84 Olympic Legacy Foundation and the Swiss-based Olympic Studies Centre atIOC headquarters) and municipal archives in New York (Borough Councils in Brooklyn,Manhattan, and Queens, and the NYC 2012, Inc. Olympic bidding corporation) and Doha(Qatar University). These are interpreted using in-depth interviews with 30 sports sector con-sultants, program officers at international sports federations, and local planners in case studylocations.

4. Madrid 16 (2007) Madrid 2016 Olympic Candidature File (vol. 1, p. 17); Cape Town 2004(1996) Cape Town 2004 Olympic Candidature File (vol. 1, p. 5)

5. Groupment d’intérêt publique Paris 2012 (2003) Paris 2012 Olympic Candidature File (vol. 1,p. 33); Tokyo 2020 Olympic Bid Committee (2012) Tokyo 2020 Olympic Candidature File(vol. 1, p. 16)

6. Baku 2020 Applicant Bid Committee (2011) Candidature Acceptance Application for Baku tohost the Games of the XXXII Olympiad in 2020 (p. 7); Doha 2020 (2011) Doha 2020:Applicant City (p. 4)

7. Istanbul Olympic Games Preparation and Organisation Council (2012), Istanbul 2020 OlympicCandidature File (vol. 1, p. 23)

8. Canonical discriminant analysis defines vectors in a data set that best separate observationsinto categories (e.g., typological themes used to define “the city”), based on respective valueson the observations’ variables (e.g., institutional characteristics of each bid). These vectors aredefined as Fkm ¼ Constantk þ CpXpkm, where Fkm is the discriminant score for bid m in “city”theme k, Xpkm is the value of bid characteristic p for bid m in theme k, and Cp is the coefficientof each characteristic.

9. This function includes capital investment, the ratio of transportation to nontransportationinvestment, the amount of additional/Olympic-specific investment, the type of institutionsponsoring the bid, and the type of institution guaranteeing financial shortfalls on the project.It correctly classifies 77% of cases in each group and is significantly related to the groupclassifications at a 99% level of confidence (Wilks’ Lambda = 0.41).

10. Moses, Robert (3 June 1967), The Saga of Flushing Meadow, New York World’s Fair1964–1965 Corporation, Queens Library archives, Queensborough Library archives

11. Investment numbers are from New York World’s Fair 1964–1995 Progress Report, 15 August1960, New York World’s Fair 1964–1965 Corporation, Queensborough Library archives

12. NYC 2012 (various years), Bid committee fundraising reports, NYC 2012 records at the NewYork Municipal Archives

13. New York City Planning Commission meeting minutes, docket N060046(A)ZRM (7December 2005) & docket N080184(A)ZRM (2 July 2008); Hudson Yards DevelopmentCorporation meeting minutes (16 November 2005), http://www.hudsonyardsnewyork.com

14. Oliver Koppel and Jay Kriegel, in a New York city council hearing on “Land use issues relatedto the New York City proposal to host the Olympic Games in 2012” (29 April 2003), transcriptfrom the Laguardia and Wagner Archives.

15. Doha 2020 Applicant File, p 88; in reference to the Qatar National Vision 2030, QatarNational Master Plan 2032, Qatar National Development Strategy 2011–2016, the nationalTransport Master Plan, and the Qatar Sport Venue Master Plan

16. Interview with CEO of a Doha-based architecture firm, May 201417. Doha 2020 Applicant File, p 3

Urban Geography 93

ReferencesAcuto, Michele (2013). City leadership in global governance. Global Governance: A Review of

Multilateralism and International Organizations, 19(3), 481–498.Addie, Jean-Paul D. (2013). Metropolitics in motion: The dynamics of transportation and state

reterritorialization in the Chicago and Toronto city-regions. Urban Geography, 34(2), 188–217.Alberts, Heike C. (2009). Berlin’s failed bid to host the 2000 summer Olympic Games: Urban

development and the improvement of sports facilities. International Journal of Urban andRegional Research, 33(2), 502–516.

Allen, John, & Cochrane, Allan (2014). The urban unbound: London’s politics and the 2012Olympic Games. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 38(5), 1609–1624.

Andranovich, Greg, & Burbank, Matthew (2011). Contextualizing Olympic legacies. UrbanGeography, 32(6), 823–844.

Andranovich, Greg, Burbank, Matthew, & Heying, Charles (2001). Olympic cities: Lessons learnedfrom mega-event politics. Journal of Urban Affairs, 23(2), 113–131.

Bilsel, Cânâ, & Zelef, Halûk (2011). Mega events in Istanbul from Henri Prost’s master plan of 1937to the twenty-first-century Olympic bids. Planning Perspectives, 26(4), 621–634.

Black, David, & Peacock, Byron (2011). Catching up: Understanding the pursuit of major gamesby rising developmental states. The International Journal of the History of Sport, 28(16),2271–2289.

Brenner, Neil (2004). New state spaces: Urban governance and the rescaling of statehood. Oxford:Oxford University Press.

Brenner, Neil (2013). Theses on urbanization. Public Culture, 25(1 69), 85–114.Brenner, Neil, & Schmid, Christian (2014). The ‘Urban Age’ in question. International Journal of

Urban and Regional Research, 38(3), 731–755.Burbank, Matthew J., Andranovich, Greg, & Heying, Charles H. (2002). Mega-events, urban

development, and public policy. Review of Policy Research, 19(3), 179–202.Caro, Robert A. (1974). The power broker: Robert Moses and the fall of New York (1st ed.). New

York: Knopf.Cochrane, Allan, Peck, Jamie, & Tickell, Adam (1996). Manchester plays games: Exploring the

local politics of globalisation. Urban Studies, 33(8), 1319–1336.Cook, Ian R., & Ward, Kevin (2011). Trans-urban networks of learning, mega events and policy

tourism: The case of Manchester’s Commonwealth and Olympic Games projects. UrbanStudies, 48(12), 2519–2535.

Cox, Kevin R. (2009). ‘Rescaling the state’ in question. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economyand Society, 2(1), 107–121.

Cox, Kevin R. (2011). Commentary. From the new urban politics to the ‘New’ metropolitan politics.Urban Studies, 48(12), 2661–2671.

Daffara, Phillip (2011). Special issue: Alternative city futures. Futures, 43(7), 639–641.Davidson, Mark (2010). Sustainability as ideological praxis: The acting out of planning’s master-

signifier. City, 14(4), 390–405.Davidson, Mark (2013). The sustainable and entrepreneurial park? Contradictions and persistent

antagonisms at Sydney’s Olympic Park. Urban Geography, 34(5), 657–676.Edelson, Nathan (2011). Inclusivity as an Olympic event at the 2010 Vancouver Winter Games.

Urban Geography, 32(6), 804–822.Evans, Graeme (2003). Hard-branding the cultural city – from Prado to Prada. International Journal

of Urban and Regional Research, 27(2), 417–440.FIFA (2010) 2022 FIFA World Cup Bid Evaluation Report: Qatar. Zurich: Fédération Internationale

de Football AssociationFlyvbjerg, Bent, & Stewart, Allison (2012). Olympic proportions: Cost and cost overrun at the

Olympics 1960–2012. Saïd Business School working papers. Oxford: University of Oxford.González, Sara (2011). Bilbao and Barcelona ‘in motion’. How urban regeneration ‘models’ travel

and mutate in the global flows of policy tourism. Urban Studies, 48(7), 1397–1418.Harrison, John (2010). Networks of connectivity, territorial fragmentation, uneven development:

The new politics of city-regionalism. Political Geography, 29(1), 17–27.Healey, Patsy (2006). Urban complexity and spatial strategies: Towards a relational planning for

our times (1st ed.). New York, NY: Routledge.Hollands, Robert G. (2008). Will the real smart city please stand up? City, 12(3), 303–320.Kamrava, Mehran (2013). Qatar: Small state, big politics. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

94 J. Lauermann

Karvonen, Andrew, & Van Heur, Bas (2014). Urban laboratories: Experiments in reworking cities.International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 38(2), 379–392.

Kavaratzis, Mihalis, & Ashworth, Gregory J. (2005). City branding: An effective assertion ofidentity or a transitory marketing trick? Tijdschrift Voor Economische En Sociale Geografie,96(5), 506–514.

Keil, Roger (2009). The urban politics of roll-with-it neoliberalization. City, 13(2–3), 230–245.Laclau, Ernesto (2005). On populist reason. London: Verso.Lauermann, John (2014a). Competition through inter-urban policymaking: Bidding to host megae-

vents as entrepreneurial networking. Environment & Planning A, 46(11), 2638–2653.Lauermann, John (2014b). Legacy after the bid? The impact of bidding to host Olympic Games on urban

development planning. Lausanne: International Olympic Committee and Olympic Studies Centre.Lauermann, John, & Davidson, Mark (2013). Negotiating particularity in neoliberalism studies: Tracing

development strategies across neoliberal urban governance projects. Antipode, 45(5), 1277–1297.McCann, Eugene (2001). Collaborative visioning or urban planning as therapy? The politics of

public-private policy making. The Professional Geographer, 53(2), 207–218.McCann, Eugene (2013). Policy boosterism, policy mobilities, and the extrospective city. Urban

Geography, 34(1), 5–29.McCann, Eugene, & Ward, Kevin (2011). Mobile urbanism: Cities and policymaking in the global

age. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.Moss, Mitchell (2011). How New York city won the Olympics. New York, NY: Rudin Center for

Transportation Policy and Management, New York University.Müller, Martin (2011). State dirigisme in megaprojects: Governing the 2014 Winter Olympics in

Sochi. Environment and Planning A, 43(9), 2091–2108.New York World’s Fair 1964–1965 Corporation (1960, August 15). New York World’s Fair 1964–

1965: Man’s achievement in an expanding universe. New York, NY: Author.Olds, Kris, & Yeung, Henry (2004). Pathways to global city formation: A view from the develop-

mental city-state of Singapore. Review of International Political Economy, 11(3), 489–521.Olesen, Kristian (2014). The neoliberalisation of strategic spatial planning. Planning Theory, 13(3),

288–303.Oliver, Robert (2011). Toronto’s Olympic aspirations: A bid for the waterfront. Urban Geography,

32(6), 767–787.Parnell, Susan, & Pieterse, Edgar (2010). The ‘right to the city’: Institutional imperatives of a

developmental state. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 34(1), 146–162.Parnell, Susan, & Robinson, Jennifer (2012). (Re)theorizing cities from the global south: Looking

beyond neoliberalism. Urban Geography, 33(4), 593–617.Pillay, Udesh, & Bass, Orli (2008). Mega-events as a response to poverty reduction: The 2010 FIFA

world cup and its urban development implications. Urban Forum, 19(3), 329–346.Roy, Ananya, & Ong, Aihwa (2011). Worlding cities: Asian experiments and the art of being global.

Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.Salama, Ashraf, & Wiedmann, Florian (2013). Demystifying Doha: On architecture and urbanism in

an emerging city. Burlington, VT: Ashgate.Scharfenort, Nadine (2012). Urban development and social change in Qatar: The Qatar national

vision 2030 and the 2022 FIFA World Cup. Journal of Arabian Studies, 2(2), 209–230.Scott, Allen J., & Storper, Michael (2015). The nature of cities: The scope and limits of urban

theory. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 39(1), 1–15.Shipley, Robert (2000). The origin and development of vision and visioning in planning.

International Planning Studies, 5(2), 225–236.Söderström, Ola, Paasche, Till, & Klauser, Francisco (2014). Smart cities as corporate storytelling.

City, 18(3), 307–320.Soja, Edward W. (2011). Regional urbanization and the end of the metropolis era. In Gary Bridge &

Sophie Watson (Eds.), The new Blackwell companion to the city (pp. 679–689). Malden, MA:Wiley-Blackwell.

Surborg, Björn, VanWynsberghe, Rob, & Wyly, Elvin (2008). Mapping the Olympic growthmachine. City, 12(3), 341–355.

Vigar, Geoff, Graham, Stephen, & Healey, Patsy (2005). In search of the city in spatial strategies:Past legacies, future imaginings. Urban Studies, 42(8), 1391–1410.

Wachsmuth, David (2014). City as ideology: Reconciling the explosion of the city form with thetenacity of the city concept. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 32(1), 75–90.

Urban Geography 95