The bioinvasion of Guam: inferring geographic origin, pace, pattern and process of an invasive...

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

4 -

download

0

Transcript of The bioinvasion of Guam: inferring geographic origin, pace, pattern and process of an invasive...

ORIGINAL PAPER

The bioinvasion of Guam: inferring geographic origin, pace,pattern and process of an invasive lizard (Carlia)in the Pacific using multi-locus genomic data

Christopher C. Austin • Eric N. Rittmeyer •

Lauren A. Oliver • John O. Andermann • George R. Zug •

Gordon H. Rodda • Nathan D. Jackson

Received: 15 October 2010 /Accepted: 27 April 2011 / Published online: 22 May 2011! Springer Science+Business Media B.V. 2011

Abstract Invasive species often have dramatic

negative effects that lead to the deterioration andloss of biodiversity frequently coupled with the

burden of expensive biocontrol programs and sub-

version of socioeconomic stability. The fauna andflora of oceanic islands are particularly susceptible to

invasive species and the increase of global move-ments of humans and their products since WW II has

caused numerous anthropogenic translocations and

increased the ills of human-mediated invasions. Weuse a multi-locus genomic dataset to identify geo-

graphic origin, pace, pattern and historical process of

an invasive scincid lizard (Carlia) that has beeninadvertently introduced to Guam, the Northern

Marianas, and Palau. This lizard is of major impor-

tance as its introduction is thought to have assisted inthe establishment of the invasive brown treesnake

(Boiga irregularis) on Guam by providing a food

resource. Our findings demonstrate multiple waves of

introductions that appear to be concordant withmovements of Allied and Imperial Japanese forces

in the Pacific during World War II.

Keywords Boiga ! Brown Treesnake ! Marianas !Micronesia ! New Guinea ! Palau ! World War II

Introduction

Invasive species affect the ecological co-evolutionary

cohesion of ecosystems with the potential to causedramatic declines in biodiversity over short ecolog-

ical and evolutionary time scales (Rodda et al. 1999).

Invasive species can have extreme negative effects onhuman economic development especially for agricul-

ture and tourism. The economic cost is compounded

by the necessity of establishing and maintainingbiocontrol programs. The seemingly exponential

growth of global movements of humans and theirproducts since World War II has caused numerous

anthropogenic translocations and increased the prob-

lems of human-mediated invasions (Kraus 2009).Species introduced to islands often have a greater

ecological impact than those introduced to mainland

areas (Case and Bolger 1991). Biodiversity lossassociated with invasive species is most easily

studied on islands, and the oceanic islands in the

C. C. Austin (&) ! E. N. Rittmeyer ! L. A. Oliver !J. O. Andermann ! N. D. JacksonDepartment of Biological Sciences, Museum of NaturalScience, 119 Foster Hall, Louisiana State University,Baton Rouge, LA 70803-3216, USAe-mail: [email protected]

G. R. ZugDepartment of Vertebrate Zoology, National Museumof Natural History, Washington, DC 20013, USA

G. H. RoddaUSGS Fort Collins Science Center, 2150 Centre Ave.,Bldg. C, Fort Collins, CO 80526, USA

123

Biol Invasions (2011) 13:1951–1967

DOI 10.1007/s10530-011-0014-y

Pacific offer striking examples of ecosystem altera-tions resulting from biological invasion (Rodda et al.

1991; McKeown 1996; Ota 1999; Urban et al. 2008).

Arguably the best-studied island invasive is thebrown treesnake, Boiga irregularis. This invasive

snake has decimated Guam’s native wildlife and is

responsible for a dramatic decline and extinction ofbird species (Rodda et al. 1999).

Boiga irregularis is assumed to have arrived on

Guam from the Admiralty Islands following WW II(Rodda et al. 1999). Boiga irregularis, however, isnot the only species to arrive on Guam post WW II.

Other presumed post-WWII species colonizing Guamare: the musk shrew (Suncus murinus), the black

drongo (Dicrurus macrocercus), the green anole

(Anolis carolinensis), and the Admiralty brown skink(Carlia ailanpalai) (Fritts and Rodda 1998). This

latter invasive species has received little attention

even though it is hypothesized that C. ailanpalaiindirectly aided the decline and extinction of Guam’s

native birds by providing a stable food source for

juvenile brown treesnakes (Fritts and Rodda 1998). Inaddition, Carlia is invasive on the islands of the

Northern Marianas and the Palau archipelago (Crom-

bie and Pregill 1999).The genus Carlia is composed of more than 40

species with a center of diversity in Australia and New

Guinea (Zug 2004). The Carlia fusca complex is agroup of 18 morphologically similar species found

mainly on New Guinea and surrounding islands (Zug

2004; Zug and Allison 2006; Donnellan et al. 2009).Although the invasive populations of Carlia belong tothe Carlia fusca complex, the morphological unifor-

mity and taxonomic inattention to this group led toconfusion on the specific identity of the invasive

populations (Zug 2004). In 2004, Zug delineated

species boundaries in the fusca complex based ondetailed morphological analysis and assigned species

identity to the invasive populations. He proposed

Carlia ailanpalai (native range, Admiralty Islands) asthe source for the Guam and Northern Marianas

populations and Carlia tutela (native range, Halma-hera) as the source for the Palau populations.

In this study, we use a holotypic and topotypic

multi-locus genomic dataset to identify the species ofintroduced Carlia (Fig. 1; Appendix). These data

reveal the source populations for introduced Carlia ofGuam, the Northern Marianas, and Palau and allowus to examine and correct the taxonomic confusion of

the introduced and native populations (Fig. 1). Inaddition to the pattern of invasion, we address the

mode and timing of translocations and compare the

genetic diversity of various introduced populationswith populations from the native range.

Materials and methods

Sampling

A total of 147 individuals of Carlia were sampled,

including 79 samples from New Guinea and adjacentislands representing potential source populations, and

59 samples from the introduced populations of Guam

and the Northern Marianas Islands (including sam-ples from three major islands: Saipan, Tinian and

Rota), and 9 from the introduced populations from

Palau. Samples were stored in 95% ethanol prior toextraction. Lizards were caught by hand and vou-

chered and deposited in the Texas Natural History

Museum (TNNM), South Australian Museum(SAM), or Louisiana State University Museum of

Zoology (LSUMZ). Outgroup sequences of Carliarhomboidalis, Lygisaurus curtus, Menetia timlowi,and Lampropholis coggeri were selected based on

previous phylogenetic studies involving Carliaskinks (Dolman and Hugall 2008; Donnellan et al.2009), and were obtained from GenBank (Accession

numbers available in Appendix).

DNA isolation, amplification, and sequencing

Whole genomic DNA was extracted from either liveror muscle tissue using an ammonium acetate salt

extraction protocol (Fetzner 1999) or a QiagenDNeasy

Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Inc. Valencia, CA) followingmanufacturer’s instructions. Tissues (*100–200 mg)

were digested overnight with 20 ll proteinase K, andfinal extraction concentrations of DNA were stored inAE Buffer at -20"C prior to amplification.

Two mitochondrial gene regions, including cyto-chrome oxidase b (cyt b) and NADH dehydrogenase

subunit 4 (ND4), and one nuclear locus, Beta-globin

(B-glob), were selected for sequencing based on theutility of these loci in similar groups (primer

sequences and references are available in Table 1).

Target gene regions were amplified by PCR on an MJPTC-200 thermocycler (annealing temperatures

1952 C. C. Austin et al.

123

available in Table 1) using previously published

protocols (Austin et al. 2010b). Amplified PCR

products were purified with 5 units Exonuclease Iand 1.25 units Antarctic Phosphotase (New England

Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) as in Austin et al. (2010a), and

sequenced in both directions using BigDye v. 3.1

Terminator Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems,

Foster City, CA) via previously published protocols(Austin et al. 2010b) on an ABI 3100 automated

capillary sequencer.

Fig. 1 Sampling localities of Carlia fusca group skinks inNew Guinea, Palau, and the Marianas Islands. Symbolscorrespond to clades in Fig. 2: open square, C. ailanpalai;closed circle, C. pulla; open triangle, C. mysi, Huon Peninsula;

closed square, C. mysi, Oro, Morobe Provinces; open diamond,C. eothen; closed triangle, C. sp. Northern Milne Bay; opencircle, C. sp. Southern Milne Bay; X, C. sp. Eastern Central;closed diamond, C. luctuosa; ?, C. aenigma

The bioinvasion of Guam 1953

123

Phylogenetic analysis

Sequences were visually verified to check for basedouble-calls or other misreads and complementary

strands were assembled into contigs using Sequencher

v4.7 (Gene Codes Corp., Ann Arbor, MI, USA) andaligned using ClustalX2 (Larkin et al. 2007) under

default settings (Gap opening penalty = 15, Gap

extension penalty = 6.66). All protein-coding regionswere translated to amino acid sequences using Mes-

quite v2.73 (Maddison and Maddison 2010) to verify

that no premature stop codons disrupted the readingframe. Maximum likelihood and Bayesian inference

were used to estimate the phylogeny of Carlia fuscagroup skinks, and to identify the sources of introducedpopulations. Several partitioning schemes, including

partitioning by genome (mitochondrial vs. nuclear),

locus, and codon position, were tested and the optimalpartitioning scheme was selected by comparing the

likelihoods of the resulting topologies using the

Akaike information criterion [AIC] (Akaike 1974).The best fit models of nucleotide substitution for each

partition were selected using the corrected AIC

(Akaike 1974) in jModelTest ver. 0.1.1 (Posada2008). Maximum Likelihood analyses were imple-

mented in using the partition testing version of

GARLI-part v. 0.97 (Zwickl 2006). GARLI analyseswere run under default settings with 50 search

replicates to ensure the maximum likelihood phylog-

eny was identified. Maximum likelihood support forthe optimal partitioning scheme was estimated using

100 bootstrap pseudoreplicates under default settings

with a single search replicate per bootstrap pseudo-replicate. The partitioned Bayesian inference analysis

was implemented in Mr. Bayes v. 3.1.2 (Huelsenbeck

and Ronquist 2001; Ronquist and Huelsenbeck 2003).For all models, the prior nucleotide state frequencies,

transition/transversion ratio, and substitution ratepriors were set as flat Dirichlet distributions, and the

proportion of invariable sites was set as a uniform

(0.0–1.0) prior distribution. Rate priors were set tovariable to allow the nucleotide substitution rates to

vary among partitions. Analyses consisted of two runs,

each of 4 chains with default heating and samplingevery 1,000 generations for 2,50,00,000 generations.

We discarded the first 15,000 topologies as burn-in,

and verified convergence using the program Tracerv1.5 (Rambaut and Drummond 2007) by examining

the posterior probability, log likelihood, and all model

parameters for stationarity and by examining theeffective sample sizes (ESSs), all of which were

substantially greater than 200 at run completion. We

also used Are We There Yet (AWTY) (Nylander et al.2008) to compare the posterior probabilities of all

splits between runs to further verify convergence. At

run completion, the plot comparing posterior proba-bilities of splits between runs was linear, indicating

that the two runs had converged and were sampling the

posterior distribution.To further investigate relationships among intro-

duced Carlia populations and source populations

identified via phylogenetic analyses, we constructedmultilocus haplotype networks for islands containing

introduced populations. Individuals for which we

could not obtain sequence data for all three loci wereexcluded from haplotype network analyses. Genetic

distance matrices were calculated for each locus using

uncorrected p distances and maximum likelihooddistances in Paup* v4.0b10 (Swofford 2003), and

combined to a single genetic distance matrix using

Pofad v.1.03 (Joly and Bruneau 2006). Multilocushaplotype networks were then constructed using the

NeighborNet algorithm (Bryant and Moulton 2004) in

SplitsTree v4.11 (Huson and Bryand 2006).

Table 1 Primers and annealing temperatures used in this study

Locus Primers Primer sequence Temp.("C)

Reference

Cyt B H15149 50-AAA CTG CAG CCC CTC AGA ATG ATA AA-30 48 Kocher et al. (1989)

L14841 50-AAA AAG CTT CCA TCC AAC ATC TCA GC-30 Kocher et al. (1989)

ND4 ND4.light 50-CAC CTA TGA CTA CCA AAA GCT CATGTA GAA GC-30

55 Arevalo et al. (1994)

Leu3.heavy 50-GAA TTA GCA GTT CTT TRT G-30 Stuart-Fox et al. (2002)

b-globin

Bglo1CR 50-GCG AAC TGC ACT GYG ACA AG-30 59 Dolman and Phillips (2004)

Bglo2CR 50-GCT GCC AAG CGG GTG GTG A-30 Dolman and Phillips (2004)

1954 C. C. Austin et al.

123

Genetic diversity

Due to the founder effect associated with introduction,many invasive populations show decreased genetic

diversity relative to native populations. To investigate

this in Carlia, we calculated nucleotide diversity (p)for both native and introduced populations of Carliausing the pegas package ver. 0.3-2 (Paradis 2010) in R

v. 2.11.0. Populations for the calculation of nucleotidediversity were defined as those samples collected with

5 km of one another. Both mitochondrial loci (cyt b

and ND4) were concatenated and samples for whichwe could not obtain sequence for one mitochondrial

locus were excluded; sites with missing data in one or

more samples were also excluded from the calculationof nucleotide diversity.

Results

Phylogenetic analyses

The final aligned dataset was a total of 1603 bp.

Lengths of each partition, numbers of variable sites,and models of nucleotide substitution (selected using

AIC) are provided in Table 2. In both maximum

likelihood and Bayesian inference, a scheme of sevenpartitions was selected as optimal using AIC: B-glob,

cyt b 1st, 2nd, and 3rd codon positions, and ND4 1st,

2nd, and 3rd codon positions. Tracer plots of allparameters, posterior probabilities, and likelihood

were stationary at similar values after the burnin

period for both Bayesian inference analyses, and allESSs were substantially greater than 200 at run

completion. Additionally, AWTY plots comparingthe posterior probabilities of all splits were linear,

indicating that Bayesian inference analyses had

reached convergence.The phylogenetic reconstructions (Fig. 2) strongly

support (Bayesian posterior probability, PP = 1.0,

maximum likelihood bootstrap support, BS = 100)distinct clades that correspond to species. All of the

invasive Carlia populations fall within a clade that

corresponds to C. ailanpalai (holotypic and topotypicmaterial included). Within this C. ailanpalai clade,three major clades are recovered: (A) the Northern

Marianas Islands (Saipan, Tinian and Rota) and theAdmiralty Islands (PP = 0.99, BS = 57), (B) Palau

and New Britain (PP = 1.0, BS = 81), and

(C) Guam, New Ireland, Halmahera and the Admi-ralty Islands (PP = 1.0, BS = 77). These subclades

are all strongly supported in Bayesian analyses

(PP[ 0.99), and, with the exception of subclade A,are strongly supported in maximum likelihood anal-

yses (BS = 57, 81, and 77 for clades A, B, and C,

respectively). Results of the haplotype networks fornative and introduced populations of C. ailanpalaiwere similar between the two methods of genetic

distance calculation, and corroborate the results of thephylogenetic analyses. Samples cluster into three

clades in the haplotype network, corresponding to the

three clades recovered within C. ailanpalai in thephylogenetic analyses (Figs. 2, 3). Genetic diver-

gence among these clades (maximum p distance is

0.0153 for cyt b and 0.0346 for ND4) is lower thanthose among other clades that are currently recong-

nized as good species and indicate at least three

introduction events from three genetically identifiablesource populations for the introduced Pacific popu-

lations of C. ailanpalai: New Britain as the source

population for Palau, the Admiralty Islands as thesource population for the Northern Marianas Islands

(Tinian, Saipan and Rota), and the Admiralty Islands,

New Ireland, or Halmahera as the source populationfor Guam.

Genetic diversity

Nucleotide diversity for the concatenated mitochon-drial dataset is shown in Fig. 4. Despite the larger

sample sizes for the introduced populations relative

to the native populations (Appendix), nucleotidediversity within each of the introduced populations

Table 2 Lengths and number of parsimony informative sitesfor each partition in the optimal partitioning scheme

Partition Length(bp)

Parsimonyinformative sites

Model

cyt b pos. 1 111 25 SYM ? G

cyt b pos. 2 111 7 F81 ? I

cyt b pos. 3 112 92 GTR ? G

ND4 pos. 1 246 79 GTR ? I ? G

ND4 pos. 2 246 34 HKY ? I ? G

ND4 pos. 3 246 206 GTR ? I ? G

B-globin 531 247 GTR ? G

The bioinvasion of Guam 1955

123

is zero, with only single haplotypes recovered for

each sampled population. In contrast, all of the native

populations show expected levels of nucleotidediversity based on previous scincid studies (Smith

et al. 2001; Fuerst and Austin 2004; Austin et al.

2010a; Jackson and Austin 2010). In addition to

nucleotide diversity, nucleotide divergence is alsohigh among native populations and species.

Fig. 2 Maximum likelihood phylogeny of Carlia fusca groupskinks. Numbers on nodes indicate maximum likelihoodbootstrap proportions and Bayesian posterior probabilities,respectively, asterisks indicate bootstrap support of 100 or

posterior probability support of 1.0. The holotype of C.ailanpalai is indicated with an H; paratypes of C. ailanpalaiare indicated with P’s; topotype samples are indicated with T’s

1956 C. C. Austin et al.

123

Discussion

From a broad taxonomic standpoint, some speciesdelimitations of Zug (2004) conflict with the molec-

ular phylogeographic data presented here. Zug (2004)

considered C. ailanpalai as restricted to the Admi-ralty archipelago (Fig. 1); however, our molecular

data demonstrates that C. ailanpalai occurs morewidely including the Bismarck Archipelago, popula-

tions that Zug (2004) assigned to C. mysi, a presumed

widely occurring species distributed along the northcoast of New Guinea. Further, his Halamahera

species, C. tutela, despite being known from pre-

WWII collections (MCZ R-7674, 1907, Patani,Halmahera; RMNH 8659, 3–7 June, 1930 Morotai)

appears to be another invasive population of

C. ailanpalai. Our sampling, however, was limited(n = 2); further sampling from Halmahera and re-

examination of the type series is needed to better

understand the status of the Halmahera population.Our results demonstrate that the uniform morphology

of the C. fusca species group hides considerable

genetic diversity and we are currently investigatingthe apparent decoupling of morphological and

molecular evolution in Carlia.Because of the genetic diversity and divergence

within and among populations of C. ailanpalai acrossits native range, it is possible to trace the geographic

origins of the invasive populations. Interestingly, thethree separate invasions herein identified appear to

track the occupation and movements of Allied and

Imperial Japanese forces in this region during WorldWar II. First, Palau was invaded by Imperial Japanese

forces early in the war as the Japanese forces movedsouth and eastward culminating with their occupation

of northern New Guinea and various Pacific islands.

Fig. 3 Network ofmultilocus data from Carliaailanpalai samplesconstructed using theNeighbornet algorithm inSplitsTree. Clade names(A, B, C) correspond tothose indicated in Fig. 2

Fig. 4 Histogram of intra-population nucleotide diversitycalculated from 1,072 bp of mitochondrial DNA (includingboth cyt b and ND4) for native and introduced populations ofCarlia fusca group skinks. Populations with no bars (includingall introduced populations and some native populations)indicate that a single mitochondrial haplotype was recoveredfrom that population

The bioinvasion of Guam 1957

123

The natural harbor of Rabaul on the northern end ofNew Britain was a major Japanese stronghold, and

the Allies decided to bypass and isolate it in their

campaign to recapture New Guinea and in theirmovement to retake the Philippines (Gailey 2004).

The invasive Palau population is part of a well-

supported clade of samples from New Britainsuggesting that translocation of military materiel

from the Japanese forces on New Britain to Palau

could have resulted in the introduction of C. ailanp-alai from New Britain to Palau. Second, the Guam

populations are part of a well-supported clade from

New Ireland and the Admiralty archipelago, the laterof which was a major base for Allies’ operations and

support the introduction of C. ailanpalai onto Guam

via the transport of Allied military materiel (Morison1953). Finally, the invasive populations from the

Northern Marianas islands of Saipan, Tinian and Rota

are nested in a clade from the Admiralty archipelagoindicating an introduction independent from the

Guam introduction. Thus, the Marianas populations

show the genetic signature of two separate invasions:one invasion of Guam, and a second invasion of the

Northern Marianas Islands of Saipan, Tinian and

Rota.The exact timing of the introductions, however,

remains uncertain. The Bismarck-Palau introduction

presumably occurred during the latter days of theJapanese occupation of Rabaul and their movement

of military materials back to Palau to re-enforce their

Palauan base. The general assumption for the intro-duction of Carlia into the Marianas was post-WWII

removal of military supplies from New Guinea to

permanent bases within the Marianas as there wassubstantial postwar salvage movement of ships and

materiel between Manus and other Pacific islands.

Supporting an hypothesis of WW II era transloca-tions, the first collections of Carlia from these regions

are: Guam 1968 (USNM 192894, CAS 139825-7),

Palau 1968 (MCZ R-104514-6, 104518-24, 111930-73,113491, 114600-40, 118591), and Northern Marianas

(Saipan) 1962 (FMNH 17641-3). Although all thesedates are well past the end of WWII, the initial

propagules may have needed time to become estab-

lished to reach sufficient population densities to attractattention and be collected and deposited in museum

collections.

The broad geographic distribution of C. ailanpalaialong with the corresponding phylogeographic struc-

ture has allowed us to tease out the genetic signature

of the origin, mode and tempo of invasion. Theidentification of the species and specific source

population has the ability to identify potential bio-

control methods such as population-specific parasites.Further, if our hypothesized timeline of WWII

introductions is correct, this suggests that this species,

and possibly other invasive lizards, may require asignificant establishment time (*20–30 years)

before becoming widely abundant. This lag in

establishment, even for species that use secondarygrowth habitats like C. ailanpalai, means that with

appropriate long-term sampling programs there may

be sufficient time to identify, control and eliminateany future island introductions. Vigilant monitoring

and continued museum vouchered collections, there-

fore, are imperative for sound conservation manage-ment. Our data also demonstrates that large

movements of military materiel can transport exotic

invasive species. Given the large scale transport ofmilitary materiel to and from the US and Iraq and

Afghanistan appropriate controls should be imple-

mented to preclude transport of invasive species.

Acknowledgments We thank the people from the manydifferent village communities where we were given theprivilege to conduct fieldwork on their land. We thank B.Roy, V. Kula, and B. Wilmot from the PNG Department ofEnvironment and Conservation, J. Robins from the PNGNational Research Institute. Jim Animiato, Ilaiah Bigilale, andBulisa Iova from the PNG National Museum provided researchassistance in Papua New Guinea. Robert Reed kindly providedsamples from the Marianas and Ben Evans and Iqbal Setiadikindly provided samples from Halmahera. Ken Tighe providedinformation on dates of first collections and discussions withRon Crombie provided valuable information. This manuscriptwas improved from comments from the Austin lab group andLeslie Austin. Fieldwork by GZ in PNG was supported by theSmithsonian Research Awards Program and subsequentmuseum studies of Carlia by the Smithsonian’s ScholarlyStudies Program and Research Opportunities Awards.Research was carried out under LSU IACUC protocol06-071. This research was funded by National ScienceFoundation grants DEB 0445213 and DBI 0400797 to CCA.

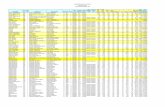

Appendix

See Table 3.

1958 C. C. Austin et al.

123

Tab

le3

Vou

cher

catalognu

mbers,collection

localities,andGenbank

accessionnu

mbers

forspecim

ensinclud

edin

thisstud

y

Species

Catalog

ueno

.ID

Locality

Latitud

eLon

gitude

GenBankaccessionnu

mbers

cytb

ND4

B-glob

Carliaaenigm

aLSUMZ94

741

Sob

o1

PNG:GulfProv.:WaboVillage

-6.97

9736

145.06

9213

HQ17

3045

HQ17

3187

HQ17

3330

Carliaaenigm

aLSUMZ94

747

Sob

o2

PNG:GulfProv.:WaboVillage

-6.97

9736

145.06

9213

HQ17

2980

HQ17

3122

HQ17

3267

Carliaailanp

alai

LSUMZ92

042

Guam

1Guam:Guam

NationalWildlifeRefug

e13

.653

367

144.86

1983

HQ17

2907

HQ17

3046

–

Carliaailanp

alai

LSUMZ92

043

Guam

2Guam:Guam

NationalWildlifeRefug

e13

.653

367

144.86

1983

HQ17

2908

HQ17

3047

HQ17

3188

Carliaailanp

alai

LSUMZ92

044

Guam

3Guam:Guam

NationalWildlifeRefug

e13

.653

367

144.86

1983

HQ17

2909

–HQ17

3189

Carliaailanp

alai

LSUMZ92

045

Guam

4Guam:Guam

NationalWildlifeRefug

e13

.653

367

144.86

1983

HQ17

2910

HQ17

3048

HQ17

3190

Carliaailanp

alai

LSUMZ92

046

Guam

5Guam:Guam

NationalWildlifeRefug

e13

.653

367

144.86

1983

HQ17

2911

HQ17

3049

HQ17

3191

Carliaailanp

alai

LSUMZ92

047

Guam

6Guam:Guam

NationalWildlifeRefug

e13

.653

367

144.86

1983

HQ17

2912

HQ17

3050

HQ17

3192

Carliaailanp

alai

LSUMZ92

048

Guam

7Guam:Guam

NationalWildlifeRefug

e13

.653

367

144.86

1983

HQ17

2913

HQ17

3051

HQ17

3193

Carliaailanp

alai

LSUMZ92

049

Guam

8Guam:Guam

NationalWildlifeRefug

e13

.653

367

144.86

1983

–HQ17

3052

HQ17

3194

Carliaailanp

alai

LSUMZ92

050

Guam

9Guam:Guam

NationalWildlifeRefug

e13

.653

367

144.86

1983

HQ17

2914

HQ17

3053

HQ17

3195

Carliaailanp

alai

LSUMZ92

051

Guam

10Guam:Guam

NationalWildlifeRefug

e13

.653

367

144.86

1983

HQ17

2915

HQ17

3054

HQ17

3196

Carliaailanp

alai

LSUMZ93

369

Guam

11Guam:Guam

NationalWildlifeRefug

e13

.653

367

144.86

1983

–HQ17

3092

HQ17

3233

Carliaailanp

alai

LSUMZ93

370

Guam

12Guam:Guam

NationalWildlifeRefug

e13

.653

367

144.86

1983

HQ17

2949

HQ17

3093

–

Carliaailanp

alai

LSUMZ93

371

Guam

13Guam:Guam

NationalWildlifeRefug

e13

.653

367

144.86

1983

HQ17

2950

HQ17

3094

HQ17

3234

Carliaailanp

alai

LSUMZ93

372

Guam

14Guam:Guam

NationalWildlifeRefug

e13

.653

367

144.86

1983

HQ17

2951

HQ17

3095

HQ17

3235

Carliaailanp

alai

LSUMZ93

373

Guam

15Guam:Guam

NationalWildlifeRefug

e13

.653

367

144.86

1983

HQ17

2952

HQ17

3096

HQ17

3236

Carliaailanp

alai

LSUMZ93

374

Guam

16Guam:Guam

NationalWildlifeRefug

e13

.653

367

144.86

1983

HQ17

2953

HQ17

3097

HQ17

3237

Carliaailanp

alai

LSUMZ93

375

Guam

17Guam:Guam

NationalWildlifeRefug

e13

.653

367

144.86

1983

HQ17

2954

HQ17

3098

HQ17

3238

Carliaailanp

alai

LSUMZ93

376

Guam

18Guam:Guam

NationalWildlifeRefug

e13

.653

367

144.86

1983

HQ17

2955

HQ17

3099

HQ17

3239

Carliaailanp

alai

LSUMZ93

377

Guam

19Guam:Guam

NationalWildlifeRefug

e13

.653

367

144.86

1983

–HQ17

3100

HQ17

3240

Carliaailanp

alai

LSUMZ93

378

Guam

20Guam:Guam

NationalWildlifeRefug

e13

.653

367

144.86

1983

–HQ17

3101

HQ17

3241

Carliaailanp

alai

LSUMZ93

379

Guam

21Guam:Guam

NationalWildlifeRefug

e13

.653

367

144.86

1983

–HQ17

3102

HQ17

3242

Carliaailanp

alai

LSUMZ93

380

Guam

22Guam:Guam

NationalWildlifeRefug

e13

.653

367

144.86

1983

HQ17

2956

HQ17

3103

HQ17

3243

Carliaailanp

alai

BJE

1146

tutela

1Indo

nesia:

Halmahera:

1.00

2512

8.00

2222

HQ17

2957

HQ17

3104

HQ17

3244

Carliaailanp

alai

BJE

1156

tutela

2Indo

nesia:

Halmahera:

1.00

2512

8.00

2222

HQ17

2958

HQ17

3105

HQ17

3245

Carliaailanp

alai

LSUMZ92

052

Saipan1

NorthernMariana

Is.:Saipan:

BirdIsland

TrailHead

15.262

278

145.81

508

HQ17

2916

HQ17

3055

HQ17

3197

Carliaailanp

alai

LSUMZ92

053

Saipan2

NorthernMariana

Is.:Saipan:

BirdIsland

TrailHead

15.262

278

145.81

508

–HQ17

3056

HQ17

3198

Carliaailanp

alai

LSUMZ92

054

Saipan3

NorthernMariana

Is.:Saipan:

BirdIsland

TrailHead

15.262

278

145.81

508

HQ17

2917

HQ17

3057

HQ17

3199

The bioinvasion of Guam 1959

123

Tab

le3

continued

Species

Catalog

ueno

.ID

Locality

Latitud

eLon

gitude

GenBankaccessionnu

mbers

cytb

ND4

B-glob

Carliaailanp

alai

LSUMZ92

055

Saipan4

NorthernMariana

Is.:Saipan:

BirdIsland

TrailHead

15.262

278

145.81

508

–HQ17

3058

HQ17

3200

Carliaailanp

alai

LSUMZ92

056

Saipan5

NorthernMariana

Is.:Saipan:

BirdIsland

TrailHead

15.262

278

145.81

508

–HQ17

3059

HQ17

3201

Carliaailanp

alai

LSUMZ92

057

Saipan6

NorthernMariana

Is.:Saipan:

BirdIsland

TrailHead

15.262

278

145.81

508

HQ17

2918

HQ17

3060

HQ17

3202

Carliaailanp

alai

LSUMZ92

058

Saipan7

NorthernMariana

Is.:Saipan:

BirdIsland

TrailHead

15.262

278

145.81

508

HQ17

2919

HQ17

3061

HQ17

3203

Carliaailanp

alai

LSUMZ92

059

Saipan8

NorthernMariana

Is.:Saipan:

BirdIsland

TrailHead

15.262

278

145.81

508

HQ17

2920

HQ17

3062

HQ17

3204

Carliaailanp

alai

LSUMZ92

060

Saipan9

NorthernMariana

Is.:Saipan:

BirdIsland

TrailHead

15.262

278

145.81

508

HQ17

2921

HQ17

3063

HQ17

3205

Carliaailanp

alai

LSUMZ92

062

Saipan10

NorthernMariana

Is.:Saipan:

BirdIsland

TrailHead

15.262

278

145.81

508

HQ17

2922

HQ17

3064

–

Carliaailanp

alai

LSUMZ92

064

Saipan11

NorthernMariana

Is.:Saipan:

BirdIsland

TrailHead

15.262

278

145.81

508

HQ17

2923

HQ17

3065

HQ17

3206

Carliaailanp

alai

LSUMZ92

065

Saipan12

NorthernMariana

Is.:Saipan:

BirdIsland

TrailHead

15.262

278

145.81

508

HQ17

2924

HQ17

3066

HQ17

3207

Carliaailanp

alai

LSUMZ92

066

Saipan13

NorthernMariana

Is.:Saipan:

BirdIsland

TrailHead

15.262

278

145.81

508

HQ17

2925

HQ17

3067

HQ17

3208

Carliaailanp

alai

LSUMZ92

067

Saipan14

NorthernMariana

Is.:Saipan:

BirdIsland

TrailHead

15.262

278

145.81

508

HQ17

2926

HQ17

3068

HQ17

3209

Carliaailanp

alai

LSUMZ92

068

Saipan15

NorthernMariana

Is.:Saipan:

BirdIsland

TrailHead

15.262

278

145.81

508

HQ17

2927

HQ17

3069

HQ17

3210

Carliaailanp

alai

LSUMZ92

069

Saipan16

NorthernMariana

Is.:Saipan:

BirdIsland

TrailHead

15.262

278

145.81

508

HQ17

2928

HQ17

3070

HQ17

3211

Carliaailanp

alai

LSUMZ92

070

Saipan17

NorthernMariana

Is.:Saipan:

BirdIsland

TrailHead

15.262

278

145.81

508

HQ17

2929

HQ17

3071

HQ17

3212

Carliaailanp

alai

LSUMZ92

071

Saipan18

NorthernMariana

Is.:Saipan:

BirdIsland

TrailHead

15.262

278

145.81

508

HQ17

2930

HQ17

3072

HQ17

3213

Carliaailanp

alai

LSUMZ92

072

Saipan19

NorthernMariana

Is.:Saipan:

BirdIsland

TrailHead

15.262

278

145.81

508

HQ17

2931

HQ17

3073

HQ17

3214

Carliaailanp

alai

LSUMZ92

073

Saipan20

NorthernMariana

Is.:Saipan:

BirdIsland

TrailHead

15.262

278

145.81

508

HQ17

2932

HQ17

3074

HQ17

3215

1960 C. C. Austin et al.

123

Tab

le3

continued

Species

Catalog

ueno

.ID

Locality

Latitud

eLon

gitude

GenBankaccessionnu

mbers

cytb

ND4

B-glob

Carliaailanp

alai

LSUMZ92

074

Saipan21

NorthernMariana

Is.:Saipan:

BirdIsland

TrailHead

15.262

278

145.81

508

HQ17

2933

HQ17

3075

HQ17

3216

Carliaailanp

alai

SAMR

4800

2Palau

9Palau:Ang

aur

6.91

6667

134.12

4167

HQ17

2979

HQ17

3121

HQ17

3266

Carliaailanp

alai

SAMR

4770

7Palau

1Palau:Babeldaob

7.39

113

4.51

1433

HQ17

2971

–HQ17

3258

Carliaailanp

alai

SAMR

4770

8Palau

2Palau:Babeldaob

7.39

113

4.51

1433

HQ17

2972

–HQ17

3259

Carliaailanp

alai

SAMR

4775

4Palau

5Palau:Koror

7.33

3333

134.47

HQ17

2975

HQ17

3120

HQ17

3262

Carliaailanp

alai

SAMR

4790

0Palau

6Palau:Koror

7.33

7513

4.47

3333

HQ17

2976

–HQ17

3263

Carliaailanp

alai

SAMR

4790

1Palau

7Palau:Koror

7.33

7513

4.47

3333

HQ17

2977

–HQ17

3264

Carliaailanp

alai

SAMR

4797

5Palau

8Palau:Koror

7.33

7513

4.47

3333

HQ17

2978

–HQ17

3265

Carliaailanp

alai

SAMR

4773

3Palau

4Palau:Malakal

7.32

1833

134.44

1667

HQ17

2974

HQ17

3119

HQ17

3261

Carliaailanp

alai

SAMR

4772

9Palau

3Palau:Ngerm

alik

7.33

6667

134.45

5HQ17

2973

HQ17

3118

HQ17

3260

Carliaailanp

alai

THNM

5138

8New

Britain

1PNG:EastNew

Britain

Prov.:Rabaul

-4.19

5914

152.17

2903

HQ17

2959

HQ17

3106

HQ17

3246

Carliaailanp

alai

THNM

5138

9New

Britain

2PNG:EastNew

Britain

Prov.:Rabaul

-4.19

5914

152.17

2903

HQ17

2960

HQ17

3107

HQ17

3247

Carliaailanp

alai

LSUMZ93

933*

Manus

4PNG:Manus

Prov.:Los

NegrosIs.:Lon

iuVillage

-2.07

0167

147.34

0833

HQ17

2988

HQ17

3130

HQ17

3275

Carliaailanp

alai

LSUMZ93

934*

Manus

5PNG:Manus

Prov.:Los

NegrosIs.:Lon

iuVillage

-2.07

0167

147.34

0833

HQ17

2989

HQ17

3131

HQ17

3276

Carliaailanp

alai

USNM

5600

85**

*Manus

8PNG:Manus

Prov.:Los

NegrosIs.:Peyon

Village

-2.03

2667

147.43

4167

HQ17

2992

HQ17

3134

HQ17

3279

Carliaailanp

alai

USNM

5600

87**

Manus

6PNG:Manus

Prov.:Los

NegrosIs.:Rio

Rio

Village

-2.04

9167

147.41

8667

HQ17

2990

HQ17

3132

HQ17

3277

Carliaailanp

alai

LSUMZ93

941

Manus

7PNG:Manus

Prov.:Los

NegrosIs.:Rio

Rio

Village

-2.04

9167

147.41

8667

HQ17

2991

HQ17

3133

HQ17

3278

Carliaailanp

alai

LSUMZ93

925

Manus

1PNG:Manus

Prov.:Manus

Is.:Kaw

aliap

Village

-2.11

147.06

7667

HQ17

2981

HQ17

3123

HQ17

3268

Carliaailanp

alai

LSUMZ93

926

Manus

2PNG:Manus

Prov.:Manus

Is.:Kaw

aliap

Village

-2.11

147.06

7667

HQ17

2982

HQ17

3124

HQ17

3269

Carliaailanp

alai

LSUMZ93

927

Manus

3PNG:Manus

Prov.:Manus

Is.:Kaw

aliap

Village

-2.11

147.06

7667

HQ17

2983

HQ17

3125

HQ17

3270

Carliaailanp

alai

USNM

5600

88**

Manus

9PNG:Manus

Prov.:Manus

Is.:Tingau

Village

-2.09

614

7.10

55HQ17

2993

HQ17

3135

HQ17

3280

Carliaailanp

alai

USNM

5600

89**

Manus

10PNG:Manus

Prov.:Manus

Is.:Tingau

Village

-2.09

614

7.10

55HQ17

2994

HQ17

3136

HQ17

3281

The bioinvasion of Guam 1961

123

Tab

le3

continued

Species

Catalog

ueno

.ID

Locality

Latitud

eLon

gitude

GenBankaccessionnu

mbers

cytb

ND4

B-glob

Carliaailanp

alai

USNM

5600

90**

Manus

11PNG:Manus

Prov.:Manus

Is.:Tingau’

Village

-2.09

614

7.10

55HQ17

2995

HQ17

3137

HQ17

3282

Carliaailanp

alai

LSUMZ93

942

Manus

12PNG:Manus

Prov.:Ram

butyoIs.:Penchal

Village

-2.34

0514

7.79

45HQ17

2996

HQ17

3138

HQ17

3283

Carliaailanp

alai

USNM

5601

37Manus

13PNG:Manus

Prov.:Ton

gIs.

-2.05

8333

147.75

8333

HQ17

2997

HQ17

3139

HQ17

3284

Carliaailanp

alai

THNM

5146

8New

Ireland3

PNG:New

IrelandProv.:Kavieng

-2.56

6496

150.79

8547

HQ17

2963

HQ17

3110

HQ17

3250

Carliaailanp

alai

THNM

5146

9New

Ireland4

PNG:New

IrelandProv.:Kavieng

-2.56

6496

150.79

8547

HQ17

2964

HQ17

3111

HQ17

3251

Carliaailanp

alai

THNM

5140

6New

Ireland1

PNG:New

IrelandProv.:Lelet

Plateau

-3.43

0352

151.99

8138

HQ17

2961

HQ17

3108

HQ17

3248

Carliaailanp

alai

THNM

5141

1New

Ireland2

PNG:New

IrelandProv.:Lelet

Plateau

-3.43

0352

151.99

8138

HQ17

2962

HQ17

3109

HQ17

3249

Carliaailanp

alai

LSUMZ93

363

Rota1

Rota:

Tenetu

14.137

019

145.15

4436

HQ17

2943

HQ17

3086

HQ17

3227

Carliaailanp

alai

LSUMZ93

364

Rota2

Rota:

Tenetu

14.137

019

145.15

4436

HQ17

2944

HQ17

3087

HQ17

3228

Carliaailanp

alai

LSUMZ93

365

Rota3

Rota:

Veteran’s

Mem

orialPark

14.167

714

145.17

5692

HQ17

2945

HQ17

3088

HQ17

3229

Carliaailanp

alai

LSUMZ93

366

Rota4

Rota:

Veteran’s

Mem

orialPark

14.167

714

145.17

5692

HQ17

2946

HQ17

3089

HQ17

3230

Carliaailanp

alai

LSUMZ93

367

Rota5

Rota:

Veteran’s

Mem

orialPark

14.167

714

145.17

5692

HQ17

2947

HQ17

3090

HQ17

3231

Carliaailanp

alai

LSUMZ93

368

Rota6

Rota:

Veteran’s

Mem

orialPark

14.167

714

145.17

5692

HQ17

2948

HQ17

3091

HQ17

3232

Carliaailanp

alai

LSUMZ92

724

Tinian1

Tinian

14.993

603

145.63

3328

HQ17

2934

HQ17

3076

HQ17

3217

Carliaailanp

alai

LSUMZ92

725

Tinian2

Tinian

14.993

603

145.63

3328

HQ17

2935

HQ17

3077

HQ17

3218

Carliaailanp

alai

LSUMZ92

726

Tinian3

Tinian

14.993

603

145.63

3328

HQ17

2936

HQ17

3078

HQ17

3219

Carliaailanp

alai

LSUMZ92

727

Tinian4

Tinian

14.993

603

145.63

3328

–HQ17

3079

HQ17

3220

Carliaailanp

alai

LSUMZ92

728

Tinian5

Tinian

14.993

603

145.63

3328

HQ17

2937

HQ17

3080

HQ17

3221

Carliaailanp

alai

LSUMZ92

729

Tinian6

Tinian

14.993

603

145.63

3328

HQ17

2938

HQ17

3081

HQ17

3222

Carliaailanp

alai

LSUMZ92

732

Tinian7

Tinian

14.993

603

145.63

3328

HQ17

2939

HQ17

3082

HQ17

3223

Carliaailanp

alai

LSUMZ92

733

Tinian8

Tinian

14.993

603

145.63

3328

HQ17

2940

HQ17

3083

HQ17

3224

Carliaailanp

alai

LSUMZ92

734

Tinian9

Tinian

14.993

603

145.63

3328

HQ17

2941

HQ17

3084

HQ17

3225

Carliaailanp

alai

LSUMZ92

735

Tinian10

Tinian

14.993

603

145.63

3328

HQ17

2942

HQ17

3085

HQ17

3226

Carliaeothen

THNM

5149

6Fergu

sson

1PNG:Milne

Bay

Prov.:D’Entrecasteaux

Arch.:Fergu

sson

Is.

-9.66

4622

150.79

2103

HQ17

2968

HQ17

3115

HQ17

3255

Carliaeothen

THNM

5149

7Fergu

sson

2PNG:Milne

Bay

Prov.:D’Entrecasteaux

Arch.:Fergu

sson

Is.

-9.66

4622

150.79

2103

HQ17

2969

HQ17

3116

HQ17

3256

Carliaeothen

THNM

5150

1Fergu

sson

3PNG:Milne

Bay

Prov.:D’Entrecasteaux

Arch.:Fergu

sson

Is.

-9.66

4622

150.79

2103

HQ17

2970

HQ17

3117

HQ17

3257

1962 C. C. Austin et al.

123

Tab

le3

continued

Species

Catalog

ueno

.ID

Locality

Latitud

eLon

gitude

GenBankaccessionnu

mbers

cytb

ND4

B-glob

Carliaeothen

LSUMZ94

750*

Trobriand

s1

PNG:Milne

Bay

Prov.:Trobriand

Is.:

KiriwinaIs.

-8.54

2208

151.07

9164

HQ17

2984

HQ17

3126

HQ17

3271

Carliaeothen

LSUMZ94

248*

Trobriand

s2

PNG:Milne

Bay

Prov.:Trobriand

Is.:

KiriwinaIs.

-8.54

2208

151.07

9164

HQ17

2985

HQ17

3127

HQ17

3272

Carliaeothen

LSUMZ94

249*

Trobriand

s3

PNG:Milne

Bay

Prov.:Trobriand

Is.:

KiriwinaIs.

-8.54

2208

151.07

9164

HQ17

2986

HQ17

3128

HQ17

3273

Carliaeothen

LSUMZ94

250*

Trobriand

s4

PNG:Milne

Bay

Prov.:Trobriand

Is.:

KiriwinaIs.

-8.54

2208

151.07

9164

HQ17

2987

HQ17

3129

HQ17

3274

Carlialuctuo

saLSUMZ93

564

luctuo

sa1

PNG:Central

Prov.:Kon

eVillage

-8.41

5183

146.95

865

HQ17

3015

HQ17

3157

HQ17

3301

Carlialuctuo

saLSUMZ93

565

luctuo

sa2

PNG:Central

Prov.:Kon

eVillage

-8.41

5183

146.95

865

HQ17

3016

HQ17

3158

HQ17

3302

Carliamysi

THNM

5130

1Huo

n1

PNG:Morob

eProv.:Huo

nPeninsula:near

Oligadu

-6.70

9008

147.57

2558

HQ17

2965

HQ17

3112

HQ17

3252

Carliamysi

THNM

5133

6Huo

n2

PNG:Morob

eProv.:Huo

nPeninsula:near

Oligadu

-6.70

9008

147.57

2558

HQ17

2966

HQ17

3113

HQ17

3253

Carliamysi

THNM

5133

8Huo

n3

PNG:Morob

eProv.:Huo

nPeninsula:near

Oligadu

-6.70

9008

147.57

2558

HQ17

2967

HQ17

3114

HQ17

3254

Carliamysi

LSUMZ93

547

Morob

e1

PNG:Morob

eProv.:Kam

ialiVillage

-7.30

0514

7.13

3667

HQ17

3006

HQ17

3148

HQ17

3292

Carliamysi

LSUMZ93

549

Morob

e2

PNG:Morob

eProv.:Kam

ialiVillage

-7.30

0514

7.13

3667

HQ17

3007

HQ17

3149

HQ17

3293

Carliamysi

LSUMZ93

552

Oro

3PNG:Oro

Prov.:Baseof

Mt.Victory

-9.23

9067

149.05

43HQ17

3009

HQ17

3151

HQ17

3295

Carliamysi

LSUMZ93

553

Oro

4PNG:Oro

Prov.:Baseof

Mt.Victory

-9.23

9067

149.05

43HQ17

3010

HQ17

3152

HQ17

3296

Carliamysi

CCA

2157

Oro

1PNG:Oro

Prov.:KoreafVillage,near

Wanigela

-9.33

7667

149.14

HQ17

2999

HQ17

3141

HQ17

3286

Carliamysi

LSUMZ93

551

Oro

2PNG:Oro

Prov.:KoreafVillage,near

Wanigela

-9.33

7667

149.14

HQ17

3000

HQ17

3142

–

Carliamysi

LSUMZ93

554

Oro

5PNG:Oro

Prov.:Sarad

Mission

,Wanigela

-9.33

914

9.15

8833

HQ17

3011

HQ17

3153

HQ17

3297

Carliapu

lla

LSUMZ93

556

Sandaun

2PNG:Sandaun

Prov.:near

Warom

oVillage

-2.66

6283

141.23

8783

HQ17

3013

HQ17

3155

HQ17

3299

Carliapu

lla

LSUMZ93

557

Sandaun

3PNG:Sandaun

Prov.:near

Warom

oVillage

-2.66

6283

141.23

8783

HQ17

3014

HQ17

3156

HQ17

3300

Carliapu

lla

LSUMZ93

117

Sandaun

4PNG:Sandaun

Prov.:Vanim

o-2.68

4433

141.30

4883

HQ17

3019

HQ17

3161

HQ17

3305

Carliapu

lla

LSUMZ92

712

Sandaun

5PNG:Sandaun

Prov.:Vanim

o-2.68

4433

141.30

4883

HQ17

3020

HQ17

3162

HQ17

3306

Carliapu

lla

LSUMZ92

713

Sandaun

6PNG:Sandaun

Prov.:Vanim

o-2.68

4433

141.30

4883

HQ17

3021

HQ17

3163

HQ17

3307

Carliapu

lla

LSUMZ93

118

Sandaun

7PNG:Sandaun

Prov.:Vanim

o-2.68

4433

141.30

4883

HQ17

3022

HQ17

3164

HQ17

3308

Carliapu

lla

LSUMZ93

555

Sandaun

1PNG:Sandaun

Prov.:Warom

oVillage

-2.66

8214

1.24

42HQ17

3012

HQ17

3154

HQ17

3298

The bioinvasion of Guam 1963

123

Tab

le3

continued

Species

Catalog

ueno

.ID

Locality

Latitud

eLon

gitude

GenBankaccessionnu

mbers

cytb

ND4

B-glob

Carliasp.‘‘Amau

fuscagrou

p’’

LSUMZ94

695

Amau

1PNG:Central

Prov.:Amau

Village

-10

.036

814

8.56

4633

HQ17

3037

HQ17

3179

HQ17

3323

Carliasp.‘‘Amau

fuscagrou

p’’

LSUMZ94

696

Amau

2PNG:Central

Prov.:Amau

Village

-10

.036

814

8.56

4633

HQ17

3038

HQ17

3180

HQ17

3324

Carliasp.‘‘Amau

fuscagrou

p’’

LSUMZ94

697

Amau

3PNG:Central

Prov.:Amau

Village

-10

.036

814

8.56

4633

HQ17

3039

HQ17

3181

HQ17

3325

Carliasp.‘‘Amau

fuscagrou

p’’

LSUMZ94

719

Amau

4PNG:Central

Prov.:Amau

Village

-10

.036

814

8.56

4633

HQ17

3040

HQ17

3182

HQ17

3326

Carliasp.‘‘Milne

Bay

North

Coast’’

LSUMZ93

156

MB

12PNG:Milne

Bay

Prov.:Eastern

Cape

-10

.230

083

150.87

45HQ17

3031

HQ17

3173

HQ17

3317

Carliasp.‘‘Milne

Bay

North

Coast’’

LSUMZ92

880

MB

11PNG:Milne

Bay

Prov.:Huh

unaVillage

-10

.284

817

150.60

105

HQ17

3030

HQ17

3172

HQ17

3316

Carliasp.‘‘Milne

Bay

North

Coast’’

USNM

5601

07MB

1PNG:Milne

Bay

Prov.:Iapo

a#2

Village

-10

.258

667

150.57

35HQ17

3001

HQ17

3143

HQ17

3287

Carliasp.‘‘Milne

Bay

North

Coast’’

USNM

5601

08MB

2PNG:Milne

Bay

Prov.:Iapo

a#2

Village

-10

.258

667

150.57

35HQ17

3002

HQ17

3144

HQ17

3288

Carliasp.‘‘Milne

Bay

North

Coast’’

USNM

5600

99MB

3PNG:Milne

Bay

Prov.:NetuliIs.

-10

.234

333

150.59

7667

HQ17

3003

HQ17

3145

HQ17

3289

Carliasp.‘‘Milne

Bay

North

Coast’’

LSUMZ92

877

MB

10PNG:Milne

Bay

Prov.:Top

uraVillage

-10

.193

315

0.33

705

HQ17

3029

HQ17

3171

HQ17

3315

Carliasp.‘‘Milne

Bay

Sou

th’’

LSUMZ93

128

MB

6PNG:Milne

Bay

Prov.:NapatanaLod

gegrou

nds,Alotau

-10

.305

867

150.43

7183

HQ17

3025

HQ17

3167

HQ17

3311

Carliasp.‘‘Milne

Bay

Sou

th’’

LSUMZ93

129

MB

7PNG:Milne

Bay

Prov.:NapatanaLod

gegrou

nds,Alotau

-10

.305

867

150.43

7183

HQ17

3026

HQ17

3168

HQ17

3312

Carliasp.‘‘Milne

Bay

Sou

th’’

LSUMZ92

874

MB

8PNG:Milne

Bay

Prov.:NapatanaLod

gegrou

nds,Alotau

-10

.305

867

150.43

7183

HQ17

3027

HQ17

3169

HQ17

3313

Carliasp.‘‘Milne

Bay

Sou

th’’

LSUMZ92

875

MB

9PNG:Milne

Bay

Prov.:NapatanaLod

gegrou

nds,Alotau

-10

.305

867

150.43

7183

HQ17

3028

HQ17

3170

HQ17

3314

Carliasp.‘‘Milne

Bay

Sou

th’’

LSUMZ93

102

MB

13PNG:Milne

Bay

Prov.:Oilpalm

plantation

,westof

Alotau

-10

.399

283

150.09

1617

HQ17

3032

HQ17

3174

HQ17

3318

Carliasp.‘‘Milne

Bay

Sou

th’’

LSUMZ93

103

MB

14PNG:Milne

Bay

Prov.:Oilpalm

plantation

,westof

Alotau

-10

.399

283

150.09

1617

HQ17

3033

HQ17

3175

HQ17

3319

Carliasp.‘‘Milne

Bay

Sou

th’’

CCA

4802

MB

16PNG:Milne

Bay

Prov.:PadiPadiVillage

-10

.402

115

0.06

2717

HQ17

3035

HQ17

3177

HQ17

3321

1964 C. C. Austin et al.

123

Tab

le3

continued

Species

Catalog

ueno

.ID

Locality

Latitud

eLon

gitude

GenBankaccessionnu

mbers

cytb

ND4

B-glob

Carliasp.‘‘Milne

Bay

Sou

th’’

LSUMZ92

583

MB

17PNG:Milne

Bay

Prov.:PadiPadiVillage

-10

.402

115

0.06

2717

HQ17

3036

HQ17

3178

HQ17

3322

Carliasp.‘‘Milne

Bay

Sou

th’’

USNM

5601

36MB

4PNG:Milne

Bay

Prov.:SagaAHO

River

-10

.544

167

150.11

5167

HQ17

3004

HQ17

3146

HQ17

3290

Carliasp.‘‘Milne

Bay

Sou

th’’

USNM

5601

01MB

5PNG:Milne

Bay

Prov.:SagaAHO

River

-10

.544

167

150.11

5167

HQ17

3005

HQ17

3147

HQ17

3291

Carliasp.‘‘Milne

Bay

Sou

th’’

LSUMZ95

752

MB

15PNG:Milne

Bay

Prov.:Takwatakwai

Village

-10

.325

617

150.03

765

HQ17

3034

HQ17

3176

HQ17

3320

Outgrou

ps:

Carliabicarina

taLSUMZ93

542

bicarinata

1PNG:NCD:PortMoresby

,National

Museum

grou

nds

-9.42

5565

147.19

0129

HQ17

3008

HQ17

3150

HQ17

3294

Carliabicarina

taLSUMZ93

545

bicarinata

2PNG:NCD:PortMoresby

,2Mile

-9.47

3283

147.17

76HQ17

3017

HQ17

3159

HQ17

3303

Carliabicarina

taLSUMZ93

546

bicarinata

3PNG:NCD:PortMoresby

,2Mile

-9.47

3283

147.17

76HQ17

3018

HQ17

3160

HQ17

3304

Carliabicarina

taLSUMZ92

680

bicarinata

4PNG:Central

Prov.:Boo

tlessBay

-9.50

9333

147.29

0183

HQ17

3023

HQ17

3165

HQ17

3309

Carliabicarina

taLSUMZ92

681

bicarinata

5PNG:Central

Prov.:Boo

tlessBay

-9.50

9333

147.29

0183

HQ17

3024

HQ17

3166

HQ17

3310

Carliasp.‘‘Amau

bicarinate’’

LSUMZ94

724

Amau

bicarinate

1PNG:Central

Prov.:Amau

Village

-10

.036

814

8.56

4633

HQ17

3041

HQ17

3183

HQ17

3327

Carliasp.‘‘Amau

bicarinate’’

LSUMZ94

731

Amau

bicarinate

2PNG:Central

Prov.:Amau

Village

-10

.036

814

8.56

4633

HQ17

3042

HQ17

3184

HQ17

3328

Carliasp.‘‘Amau

bicarinate’’

LSUMZ94

732

Amau

bicarinate

3PNG:Central

Prov.:Amau

Village

-10

.036

814

8.56

4633

HQ17

3043

HQ17

3185

HQ17

3329

Carliasp.‘‘Amau

bicarinate’’

LSUMZ94

526

Amau

bicarinate

4PNG:Central

Prov.:Amau

Village

-10

.036

814

8.56

4633

HQ17

3044

HQ17

3186

–

Carliarhom

boidalis

AJ406

203

DQ35

0070

DQ34

9566

Lygisau

ruscurtus

HQ17

2998

HQ17

3140

HQ17

3285

Menetia

timlowi

–AJ290

552

AY50

8895

Lam

prop

holiscogg

eri

–FJ379

463

AY50

8900

*Indicatestopo

types

**Indicatesparatypes

***Indicatesho

lotypes

The bioinvasion of Guam 1965

123

References

Akaike H (1974) A new look at the statistical model identifi-cation. IEEE Trans Autom Control 19:716–723

Arevalo E, Davis SK, Sites JW Jr (1994) Mitochondrial DNAsequence divergence and phylogenetic relationshipsamong eight chromosome races of the Sceloporus gram-micus complex (Phrynosomatidae) in Central Mexico.Syst Biol 43:387–418

Austin CC, Rittmeyer EN, Richards SJ, et al (2010a) Phylog-eny, historical biogeography and body size evolution inPacific Island Crocodile skinks Tribolonotus (Squamata;Scincidae). Mol Phylogenet Evol 57:227–236

Austin CC, Spataro M, Peterson S, et al (2010b) Conservationgenetics of Boelen’s python (Morelia boeleni) from NewGuinea: reduced genetic diversity and divergence ofcaptive and wild animals. Conserv Genet 11:889–896

Bryant D, Moulton V (2004) Neighbor-Net: an agglomerativemethod for the construction of phylogenetic networks.Mol Biol Evol 21:255–265

Case TJ, Bolger DT (1991) The role of introduced species inshaping the distribution and abundance of island reptiles.Evol Ecol 5:272–290

Crombie RI, Pregill GK (1999) A checklist of the herpetofaunaof the Palau islands (Republic of Belau), Oceania. Her-petol Monogr 13:29–80

Dolman G, Hugall AF (2008) Combined mitochondrial andnuclear data enhance resolution of a rapid radiation ofAustralian rainbow skinks (Scincidae: Carlia). MolPhylogenet Evol 49:782–794

Dolman G, Phillips BP (2004) Single copy nuclear DNAmarkers characterized for comparative phylogeography inAustralian wet tropics rainforest skinks. Mol Ecol Notes4:185–187

Donnellan SC, Couper PJ, Saint KM, et al (2009) Systematicsof the Carlia ‘fusca’ complex (Reptilia: Scincidae) fromnorthern Australia. Zootaxa 2227:1–31

Fetzner FWJ (1999) Extracting high-quality DNA from shedreptile skins: a simplified method. BioTechniques 26:1052–1054

Fritts TH, Rodda GH (1998) The role of introduced species inthe degradation of island ecosystems: a case history ofGuam. Annu Rev Ecol Syst 29:113–140

Fuerst GS, Austin CC (2004) Population genetic structure ofthe prairie Skink (Eumeces septentrionalis): nested cladeanalysis of post Pleistocene populations. J Herpetol38:257–268

Gailey HA (2004) MacArthur’s victory: the war in New Gui-nea, 1943–1944. Presidio Press, New York

Huelsenbeck JP, Ronquist F (2001) MRBAYES: Bayesianinference of phylogeny. Bioinformatics 17:754–755

Huson DH, Bryand D (2006) Application of phylogeneticnetworks in evolutionary studies. Mol Biol Evol23:254–267

Jackson ND, Austin CC (2010) The combined effects of riversand refugia generate extreme cryptic fragmentation withinthe common ground skink (Scincella lateralis). Evolution64:409–428

Joly S, Bruneau A (2006) Incorporating allelic variation forreconstructing the evolutionary history of organisms from

multiple genes: an example from Rosa in North America.Syst Biol 55:623–636

Kocher TD, Thomas WK, Meyer A, et al (1989) Dynamics ofmitochondrial DNA evolution in animals: amplificationand sequencing with conserved primers. Proceedings ofthe National Academy of Sciences of the United States ofAmerica 86:6196–6200

Kraus F (2009) Alien reptiles and amphibians: a scientificcompendium and analysis. Springer Science, New York

Larkin MA, Blackshields G, Brown NP, Chenna R, McGetti-gan PA, McWilliam H, Valentin F, Wallace IM, Wilm A,Lopez R, Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Higgins DG (2007)Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics23:2947–2948

Maddison WP, Maddison DR (2010) Mesquite: a modular sys-tem for evolutionary analysis. Version 2.73 http://mesquiteproject.org

McKeown S (1996) A field guide to reptiles and amphibians ofthe Hawaiian islands. Diamond Head Publishing, LosOsos

Morison SE (1953) History of United States naval operations inworld war II volume 8: New Guinea and the Marianas,March 1944–August 1944. University of Illinois Press,Urbana

Nylander JAA, Wilgenbusch JC, Warren DL, Swofford DL(2008) AWTY (are we there yet?): a system for graphicalexploration of MCMC convergence in Bayesian phylog-enetics. Bioinformatics 24:581–583

Ota H (1999) Introduced amphibians and reptiles of the Ry-ukyu Archipelago, Japan. In: Rodda GH, Sawai Y, Chis-zar D, Tanaka H (eds) Problem snake management: theHabu an the brown treesnake. Comstock PublishingAssociates, Ithaca, pp 439–452

Paradis E (2010) pegas: an R package for population geneticswith an integrated-modular approach. Bioinformatics26:419–420

Posada D (2008) jModelTest: phylogenetic model averaging.Mol Biol Evol 25:1253–1256

Rambaut A, Drummond AJ (2007) Tracer v1.4. Available fromhttp://beast.bio.ed.ac.uk/Tracer

Rodda GH, Fritts TH, Reichel JD (1991) Distributional pat-terns of reptiles and amphibians in the Mariana Islands.Micronesica 24:195–210

Rodda GH, Sawai Y, Chiszar D, Tanaka H (1999) Problemsnake management: the Habu an the brown treesnake.Comstock Publishing Associates, Ithaca

Ronquist F, Huelsenbeck JP (2003) MRBAYES 3: Bayesianphylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinfor-matics 19:1572–1574

Smith SA, Austin CC, Shine R (2001) A phylogenetic analysisof variation in reproducive mode within an Australianlizard (Saiphos equalis, Scincidae). Biol J Linn Soc74:131–139

Stuart-Fox DM, Hugall AF, Moritz C (2002) A molecularphylogeny of rainbow skinks (Scincidae: Carlia): taxo-nomic and biogeographic implications. Aust J Zool 50:39–51

Swofford DL (2003) PAUP*. Phylogenetic analysis usingparsimony (*and Other Methods). Version 4. SinauerAssociates, Sunderland

1966 C. C. Austin et al.

123

Urban MC, Phillips BL, Skelly DK, Shine R (2008) A toadmore traveled: the heterogeneous invasion dynamics ofcane toads in Australia. Am Nat 171:134–148

Zug GR (2004) Systematics of the Carlia ‘‘fusca’’ lizards ofNew Guinea and nearby islands. Bishop Museum Press,Honolulu

Zug GR, Allison A (2006) New Carlia fusca complex lizards(Reptilia: Squamata: Scincidae) from New Guinea,Papua-Indonesia. Zootaxa 1237:27–44

Zwickl DJ (2006) Genetic algorithm approaches for the phy-logenetic analysis of large biological sequence datasetsunder the maximum likelihood criterion. Ph.D. disserta-tion, The University of Texas, Austin. Available from:http://www.bio.utexas.edu/faculty/antisense/garli/Garli.html

The bioinvasion of Guam 1967

123