An anthropological perspective on Marianas prehistory, including Guam

Transcript of An anthropological perspective on Marianas prehistory, including Guam

AN ANTHROPOLOGICAL PERSPECTIVE ONMARIANAS PREHISTORY, INCLUDING GUAM

Rosalind Hunter-Anderson

Introduction to an Archaeological Narrative

As an archaeologist who has been studying theMicronesian archaeological record (and trying to make senseof it!) for more than 20 years, and as a resident of Guam thatlong, I have often been asked about the origins and develop-ment of the Chamorro culture of the Marianas. I usually replythat there are no hard and fast answers to such questions; wearchaeologists have some ideas based on our current under-standing of the relevant and available facts, but no certainty.

Usually archaeologists are recognized as representing asubfield within the overarching field of anthropology, thereforeI prefer to use “anthropological” in my chapter’s title. Actually,archaeology shares the characteristic of uncertainty with othersciences, where progress in understanding the natural world isalways being sought (we are never satisfied!).

A key difference between archaeology and many othersciences, however, is that their findings have proven helpful insolving practical problems for society, such as locating new oilfields, stopping an insect pest, making a vaccine, predicting ahurricane’s landfall. How different are the results of archaeo-logical research! Although occasionally fascinating, theyhardly seem important in the context of everyday life.

This difference between archaeology and many othersciences seems to determine how our results are judged–byone another, by other scientists, and by the public. Thus formany it is not really important whether our interpretations areinadequate scientifically, as long as they tell a coherent story.It is generally known that archaeology has not spawned any

20

10.03 Perspective Vol 2 2/15/04 11:04 AM Page 20

practical applications as have chemistry and physics, fields inwhich interpretive principles have been discovered throughcontrolled experimentation. In the absence of a well estab-lished, widely accepted, and reliable set of explanatory princi-ples for our data, archaeologists describe and interpret them ina variety of ways, some better than others from a scientificstandpoint.

Regardless of its relative impracticality at this point,archaeology is a publicly supported enterprise for the mostpart, especially here in Guam and the other Mariana Islands.This support seems to reflect contemporary society’s interest inthe remote, unwritten past. Historic preservation laws havebeen passed which require archaeological assessments (andfield research or other site treatments) of public and privateland before construction projects are implemented, especiallygovernment-funded ones such as highway improvements butalso commercial developments like hotels and golf courses.These legally mandated (though often privately funded)archaeological studies generally conform to what the publicexpects from archaeology: coherent narratives that describe thearchaeological findings and provide plausible interpretations ofthem. Such work fits within our overall scientific mission and,after all, is a practical contribution too.

The technical language in archaeological reports isunfamiliar and difficult for most non-archaeologists, and ourresults often need to be “translated” for public consumption.Sometimes journalists do this, less often we do it ourselves.Whether couched in technical or non-technical language, ourwork product tends to be descriptive rather than explanatoryand seems to focus more upon objects than upon scientificproblems determined by competing theories and hypotheses.

We seem to be held to a different standard, and perhapsthis is because archaeological data are notoriously difficult toaccess, being buried in the ground or located far from “civi-lization.” Just being able to travel to a remote archaeologicalsite, retrieve its contents, and write something about them to

21

10.03 Perspective Vol 2 2/15/04 11:04 AM Page 21

some readers already qualifies as a scientific achievement,whereas in reality the scientific work has just begun. Whilearchaeologists attract public attention by finding interestingthings (defined by uniqueness, beauty, or some other appealingtrait), we gain little recognition for proving or disproving a sci-entific theory or hypothesis. Society asks us only to tell our sto-ries as clearly as possible, so that members of the public canmake up their own minds.

In the following pages I have written such an archaeolog-ical narrative. It makes no claim on “the truth,” if by that ismeant the one true way to understand the archaeologicalrecord. In the cultural realm there are many truths.Archaeology, like other historical sciences, provides cluesabout how it was in the past, but as scientists our interpretiveframeworks are designed to account for the observations thatwe have at hand, not for those we do not. This is not to say wecannot make predictions about what we will find next; indeedif our theories are correct our predictions will be borne out.This prospect is what makes our work especially exciting.

As to the editors’ request to provide a perspective onGuam’s prehistory, I believe it is unwise to try to understandthat part without considering the whole. Guam is part of alarger region, the Mariana archipelago, beyond that, of westernOceania, and beyond that, of the Pacific basin. Beyond thatstill, Guam has played a role in the peopling of the earth in thesense that the very first human habitation (if only part-time) ofthe relatively inhospitable Pacific “biome,” the last one onearth to be inhabited by our species, occurred in the Marianaarchipelago nearly four thousand years ago.

We will begin by discussing the earliest archaeologicalsites and proceed to other topics that reflect anthropology’sbroad subject matter: how and why cultures vary, no matterwhere or when they occur. The focus is on the prehistoricChamorro culture, and Guam examples are included, alongwith those of the neighboring islands.

22

10.03 Perspective Vol 2 2/15/04 11:04 AM Page 22

Initial Human Occupation of the Marianas

So far, the Marianas archaeological record has yieldedconsistent evidence for human presence beginning about 3,500years ago (one site in Saipan, Achugao, may be even earlier,dating to about 3,700 years ago) from sites in the four largestislands in the southern and geologically oldest portion of theMariana archipelago (Guam, Rota, Tinian, and Saipan). Too lit-tle is known about the archaeological record of the small islandsnorth of Saipan to say when they were first occupied, or in whatways, but limited surveys indicate that intensive use of theselocales occurred relatively late in the prehistoric sequence.

The earliest known Marianas artifacts–tools and imple-ments of stone, bone and shell, shell beads and bracelets, andpottery fragments – are found in small concentrations buried inthe sands along the coasts of Guam, Rota, Tinian, and Saipan.These artifact assemblages have been dated indirectly by asso-ciation in the same soil layer with bits of “dateable” charcoal,and by associated marine shells and fish bones thought to rep-resent food remains.

Marianas archaeologists send their finds of shell, bone,and charcoal to specialized dating laboratories on the U.S.mainland, Japan, or New Zealand. In the labs, each sample isanalyzed for radioactive carbon (C-14), and a dating estimateis made from the amount of radioactive C-14 left in the sample.This estimate is expressed as the probable number of yearssince the organism whose remains have been analyzed ceasedliving. Usually the dating estimate has a margin of error of sev-eral decades on either side of the estimated date (this margin oferror is sometimes in the hundreds of years), so that in the sci-entific literature a C-14 date may be given, for example, as a 95per cent probability that the true date of the specimen is 1350years plus or minus 50 years before present (BP).

This means that the true date could be anywhere withinthat range of years, not just at the midpoint. The midpoint ofthe dating range is usually given as a convenience but this is

23

10.03 Perspective Vol 2 2/15/04 11:04 AM Page 23

only shorthand and does not give the whole story. If archaeol-ogists want to emphasize the antiquity of a site, they mayselectively state only the oldest part of the range, but anywherealong that range is equally probable, statistically speaking. Thedecision to accept or reject radiocarbon dating results is some-times complicated and difficult but ultimately it is up to thejudgment of the archaeologist, who knows the site best and thecircumstances of the particular find being dated.

The earliest known sites in the Marianas include theformer lagoon-edge site of Chalan Piao,the Laulau Bayrockshelter, and the beachside site of Achugaoin Saipan; the beach-side sites of Unai Chuluin Tinian; and of Matapang, Tarague,and Nomna Bay in Guam. Rota’s earliest dated culturaldeposits, at Mochong Beach, are somewhat later than theothers, possibly because coastal areas were slower to developthere. The artifacts at the early sites occur in sandy soils, inareas that were once closer to the shore than they are now. Thisis because the beaches have widened over time since these siteswere first occupied. The beach widening, or shoreline progra-dation, is due to a relative decline in sea level which took placebetween 4,000 and 3,000 BP. Geologists estimate the relativesea level decline has been on the order of six feet and wascaused by geological uplift in the southern Marianas and bypost-Ice Age adjustment of sea level throughout the oceans ofthe world [see chapter one for more on this].

The earliest Marianas cultural materials tend to be buriedmore than a meter below the present ground surface. Sometimeslater prehistoric cultural layers cover the older deposits. Forexample, the Chalan Piaosite in Saipan was found by diggingtest excavations through a surface scatter of prehistoric arti-facts, revealing deep deposits. Beneath the upper layer, whichrepresented the late prehistoric period, was exposed an olderlayer which contained cultural materials also, but the artifactslooked different from the ones in the layer above. As the dig-ging proceeded, the deposit became harder to excavate andpicks were used to break it up. The deepest artifacts were

24

10.03 Perspective Vol 2 2/15/04 11:04 AM Page 24

encrusted in sand, due to tidal wetting over many centuries. Anoyster shell from this older, lower layer yielded a radiocarbondate of 3479 +/- 200 years BP. Recent work at the site obtainedcharcoal dates which indicate this shell date is still acceptable.

Similarly ancient occupation sites have not been found inthe interior parts of the islands, although none has beensurveyed completely. The apparent lack of very early interiorsites suggests light use of inland areas at first. Recent archaeo-logical surveys in central Guam have located rock shelters withcultural deposits that began to accumulate around 2,000 yearsBP, that is, some 1,500 years after the coastal areas were firstused. Maybe by then Guam’s human population was largeenough to require more intensive use of the island’s naturalresources, many of which are located in the interior. Anotherpossibility is that use of the Marianas had changed from occa-sional visits to obtain items useful in the vast trading systemsof Indonesia to permanent settlement supported by agriculture.

Upland forests contain hardwoods, and there are smallwetlands useful for agriculture, medicinal plants, and clays formaking pottery. Year-round demand for these resources wouldrequire more frequent inland forays and/or longer visits. Witha more intensive pattern of inland resource use, more culturaldeposits would be created (for archaeologists to find muchlater!). With enough day-long trips and overnight stays, thearchaeological record deposited in Guam’s interior would bemore “visible” than before.

Where Did the Earliest Settlers Originate,and Why Did They Come to the Marianas?

These questions are, like ones about the timing of initialsettlement of the Mariana Islands, not easily answered butsome ideas appear to be better than others from a scientificstandpoint. For instance, we can eliminate the notion that theycame from outer space (yes, this has been suggested in the pop-ular literature regarding other archaeological sites!) as an

26

10.03 Perspective Vol 2 2/15/04 11:04 AM Page 26

unnecessarily complex explanation which is not supported bythe facts. We can also eliminate the idea that the Marianas werefirst populated from South America. A South American originis unlikely because of the distances involved; also, physicalanthropology (which includes the study of human bones andhuman genetics) does not support it.

Comparative studies of the shapes and other characteris-tics of ancient human bones and modern peoples from manydifferent Pacific islands show that the islanders are mostclosely related to contemporary Southeast Asian people.Another line of evidence, from comparative analysis of bloodtypes and genes of modern Mariana Islanders, points to ancientconnections with Southeast Asia as well. Furthermore, histori-cal linguistic studies suggest that Chamorro, the indigenouslanguage of the Marianas, is a member of the superfamilycalled Austronesian, to which many Southeast Asian and all theother Pacific island languages belong.

Based on present information, it is not possible to pin-point a single geographic or cultural origin for the earliest set-tlers of the Marianas, and there may not have been just one. Amore realistic way to think about the settlement of this remoteisland chain, lying about 1,500 miles from the nearest largeland mass (the Philippines) is as a long-term process of migra-tion and cultural adaptation to new environmental settings, notas a single migration event.

This conception of Marianas settlement as part of a largerprocess, a major bio-cultural radiation into the western Pacificthat brought the first human occupants of all the remote Pacificislands that straddle the equator, implies the possibility of con-tinuing contributions from western sources, such as thePhilippines, even later in prehistory. Human movement into thetropical western Pacific islands seems to have been triggeredby the build-up of agricultural populations occupying the fer-tile river valleys of southern China.

Archaeology shows that Asian wild grasses were har-vested at the end of the last Ice Age c. (approximately) 12,000

27

10.03 Perspective Vol 2 2/15/04 11:04 AM Page 27

years BP, that by 8,000 years BP millet had been domesticatedin the Yellow River basin of China and that by at least 7,000years BP (there is even earlier evidence), people were grow-ing domesticated rice (Oryza sativa)in the Yangtze River val-ley of China. This information comes from collaborativestudies among archaeologists, soil scientists, agronomists,and botanists.

Botanists have identified the cereals’ pollen, phytoliths(silica bodies which develop inside plant cells and indicatewhat kind of plant it is), and the cereal grains themselves,which have been found at ancient living sites in these areas.Rice grains and husks have been observed embedded in someof the pottery at these sites. Although it may not be obvious justhow, these are some of the facts that pertain to an explanationof Marianas settlement. Ideas about the past can come frommany sources; mine are generally derived from my backgroundas an anthropologist.

An anthropological theory, confirmed by ethnographicstudies, predicts that when people are dependent upon seasonalplant harvests (such as wild grains), they tend to stay longer inone place, to complete the harvest, and then to consume thestored food during the non-growing season. With less freedomto move to new areas when local resources have been used up orare dwindling, these populations increase beyond what the localresources can support. This in turn creates pressure on people toproduce more food and for them to become even more sedentarybecause they must spend more time farming, taking care of theirland, and living from stored food. Under more sedentarylifestyles, people tend to have larger families, and they mayneed larger families to help with the farm work. Again, this addsto the growing population and so on in a continuing cycle. Thisis what may have happened in the fertile river valleys of China.

Under increasingly crowded conditions, people mustwork harder to maintain an adequate food supply. Good farmland becomes the focus of competition. A typical response tothis situation, at least on the part of those who have the poorest

28

10.03 Perspective Vol 2 2/15/04 11:04 AM Page 28

lands or not enough land, is to move away to less populatedareas rather than stay and work harder and perhaps have tofight for enough land.

In the case of rice cultivators in southern China, the direc-tion of emigration would have been south, toward subtropicaland tropical areas where people were less densely settled onthe land. These less densely settled people were practicinghunting and gathering. An ecologically important effect ofpeople moving into a new area is to challenge the existing sub-sistence system (the way the local people have been makingtheir living) to produce an adequate amount of food and othernecessities for what becomes a larger population. In this casethe pressure to produce more led to the adoption of agricultureby the current residents as well as the newcomers.

In tropical areas, cereals are not the most appropriatecrops because they originated in cooler temperate climates,where the storability of grain for winter consumption is crucialfor human survival. In fact archaeologists have determined thatthe earliest use of cereals in temperate latitudes was as storedharvests of wild grasses (the wild ancestors of rice and millet).Later these grains were domesticated, which increased theirease of cultivation and storability. In contrast, the earliest trop-ical cultivated plants were tubers, such as yams and taro, andfruits from trees (such as bananas and breadfruit), which pro-duce well under high rainfall climatic regimes. In the tropics,which are warm year round, stored harvests are not needed tofeed people over a winter.

However, when the pressure is on to increase yields,people can decide to control the life cycle of the plants withwhich they are already familiar, in order to make them moreproductive. In the model proposed here, wild yams and tarogrowing naturally on hillsides and wetlands of the tropicswould be selected for desirable traits (like size and taste) andcarefully planted and tended in favorable settings. The resultwould be that more people could be supported within a givenarea, and the demographic growth process would continue.

29

10.03 Perspective Vol 2 2/15/04 11:04 AM Page 29

Perhaps this is what happened in southern China andexplains how agriculture arose in Taiwan, Korea, and thePhilippines. But what does it have to do with settlement of theMarianas? One answer is that relentless pressure to increaseyields or to acquire new lands provides a context for Pacificexploration and settlement. Human population growth thatbegan in northern China and continued to provide impetus forpeople to practice agriculture in more southerly latitudes, pro-duced wave after wave of out-migrating families who left areasof high population density for areas without so many peopleand problems of crowding and competition for land. Underthese conditions, it was just about inevitable that people wouldfind the Marianas, although many may have perished in thesearch, and survival on the island was certainly not guaranteed.

Just when people learned of the existence of the Marianaswill never be known for sure, but probably it was not until theyhad reason to go looking for new land and learned that alterna-tives in the larger land masses were few to none. Just when thiscritical threshold was approached (and perhaps it was a fluctu-ating one) is not known. Archaeologists may be able to findclues about the timing of this process of out-migration throughcareful work at agricultural sites in the Philippines. Clueswould include evidence of intense competition for crop land(e.g., ownership markers, boundary walls, etc.) and evidence ofefforts to improve crop yields through use of irrigation, terrac-ing, and other water and soil fertility control measures. Theearliest dates of these features would suggest when pressure forout-migration was being felt strongly.

Another plausible model for exploratory voyages on thewestern fringe of the Pacific Basin posits searches for exoticitems to be used in the trading systems of Indonesia. Seanomads traveling by sailing canoe, the descendents of the thou-sands of people who lost their land during the great glacialmeltwater flooding of Sundaland after the Ice Age, may havesought new sources of trade items in the uninhabited islandseast of the Philippines. In this model, the Marianas offered sea

30

10.03 Perspective Vol 2 2/15/04 11:04 AM Page 30

shells and other things that were valued highly but were gettingscarce in the Philippines. With sea levels dropping, the beachesof the Marianas could have hosted these seasonal visitors.

Archaeological evidence indicates the Marianas were thefirst group of the “remote” Pacific Islands (east of theSolomons, which are near New Guinea and were occupied dur-ing the Pleistocene era) to be visited by people, earlier than thePolynesian islands by about 500 years. Also the Marianas arethe farthest of any of these island groups from large landmasses, that is, farther from the crowded areas from which thevisitors probably came.

In contrast, the source areas for the earliest settledPolynesian islands are less distant, but first settlement occurredlater! This puzzle may be solved by considering the geographicposition of the Marianas, which are approximately the samelatitudes as the area of earliest population pressure in SoutheastAsia, namely, the southeastern edge of the great Asian conti-nent. No such large land mass, which could act as a “peoplepump,” exists south of the equator. If Asian population growthpulsed southward, pressure for significant out-migrationshould have been experienced first in large land masses such asTaiwan and the Philippines and only later affected areas southof the equator.

Contrary to what many might think, making a living onsmall tropical Pacific islands is quite precarious for a numberof reasons. Small size means there is not much farming land (ifany), there are few useful wild plants, and no large animals.The sea may be rich in fish, but they are naturally dispersed andmoving all the time. They have to be captured in their ownelement, the sea, which is not the natural element of people;therefore this is quite difficult and risky unless fishing can beconducted in quiet shallow waters.

Consider island size and its effects. The largest island inthe Marianas (and in all of Micronesia) is Guam, at 212 squaremiles. Rota (32.9 square miles), Tinian (39.3 square miles),and Saipan (47.5 square miles) are considerably smaller. Such

31

10.03 Perspective Vol 2 2/15/04 11:04 AM Page 31

small tropical Pacific islands tend to have nutrient-poor soils,especially compared with the rich river valleys and deltas onthe edges of continents or even compared with the largestislands in the Philippines. Together small size and remotenessfrom large land masses mean that fewer species can surviveover the long term. Biologists call this “species poverty.” Forpeople living on islands, species poverty means fewer subsis-tence options and a less reliable resource base.

Add to these drawbacks that the Marianas lie at the east-ern edge of the Asian monsoon climate, with its frequentdroughts and within the pathways of destructive tropicalcyclones (called typhoons in the western Pacific), and theislands appear to be a less-than-optimal destination for farmersfrom tropical Southeast Asia. While we have tentative answersfor why they came, we still must ask, were the Mariana Islandsalways available for settlement by out-migrating farminggroups, or was there a time when they were not?

Marine geologists have established that throughout thefirst half of the Holocene (the geological epoch that beganwhen the last Ice Age ended c. 10,000 years BP), global sealevel rose rapidly as glaciers in the north and south hemispheresretreated toward the poles. This melting released huge amountsof water into the oceans, a pattern recorded throughout theworld. At mid-Holocene levels, the tropical north Pacific wasextraordinarily warm because perihelion (the time of year whenthe earth is closest to the sun) occurred in the summer months(now it occurs in the winter months in the northern hemi-sphere). The hotter summers of those days would have warmedthe ocean considerably more than now; scientists estimate thewarming was by 5 to 10 degrees centigrade. Warm water swells,and some of the height of the sea may have been caused by this.

Holocene sea level apparently peaked in the Marianas atabout six feet higher than present and began to recede to cur-rent levels between 4,000 and 3,000 years BP. When the sealevel was six feet higher than now, Guam, Rota, Tinian, andSaipan had no beaches as we know them, and most shorelines

32

10.03 Perspective Vol 2 2/15/04 11:04 AM Page 32

were steep cliffs. There were marine embayments with muddy,mangrove-lined shorelines in a few places, such as the nowfreshwater marsh at Agana, Guam. An even larger lagoon waspresent on the west coast of Saipan; now it is a brackish inlandmarsh separated from the shore by hundreds of feet of sand.While mid-Holocene environmental conditions in the islandsare poorly known, it is likely that typhoons and droughtsoccurred as well as earthquakes (the Marianas are part of theearthquake-prone “Pacific ring of fire”). Paleo-climatologistsare finding evidence that the El Ninoweather system (bringingsevere drought and low tides to the western Pacific every fourto seven years) was established by at least 5,000 years BP.

These conditions are not auspicious for successful humansettlement, but perhaps people did try if the out-migrationoption was being taken as early as the mid-Holocene. Oceanvoyaging capability at that time (sailing canoes) is not in dis-pute. People could do it. Mid-Holocene inter-island move-ments are indicated archaeologically in the Taiwan straits andeven earlier within the New Guinea/Solomons area. To date,archaeological remains of a mid-Holocene human presence inthe Marianas have not been found but that is not to say theywill not be someday.

We need better tools to help us locate the earliest sites, butfor the sake of efficiency, we also need a better idea of when tothink the Marianas would have become a target for settlementfrom crowded areas on the larger land masses to the west. This,in turn, means we need to learn more about the demographichistory and related cultural developments in likely source areassuch as the Philippines. In northern Luzon, the Philippines,archaeologists have found sites dating to c. 4000 years BP whichcontain pottery very similar to that in the earliest Marianas sites.Such similarities could be evidence of cultural connections butare insufficient to prove actual population movements.

Clearly more work needs to be done at coastal Philippinesites with Marianas settlement in mind. Archaeologists alsomust think about how to identify sites that were occupied

33

10.03 Perspective Vol 2 2/15/04 11:04 AM Page 33

seasonally or occasionally, as opposed to sites occupied per-manently. Just digging up more sites will not help us here; weneed to know what patterns to look for so we can analyze ourdata to answer these sorts of questions.

What Was the Ancient Chamorro Culture Like?

First of all, archaeologists have learned from studying thematerial culture of the Marianas that the artifacts from Guamsites closely resemble artifacts from sites in the large islandsjust to the north of Guam, regardless of the time period duringwhich the materials were made and used. The material culturesimilarities across the islands and through time imply that thenon-material parts of culture, such as language, religiousbeliefs, social groupings, and kinship systems were also sharedwidely. From these facts it makes sense to think of the ancientChamorro culture as a system of adaptation which developedand evolved throughout the archipelago while adjusting to thespecific geographic variations within it.

Nonetheless, it is important to ask about actual findingsfrom archaeological research. What have we learned from theMariana Islands archaeological record about life in the archi-pelago, how people made a living from the land and sea, theirhealth and nutritional status, their amusements, difficulties, andso on? At a very basic level, the Marianas settlers and theirdescendants grew tropical crops, caught fish (and gatheredshellfish), and collected wild resources from the land, usingtools and facilities which they fashioned from local materials.Their tools included implements that could cut, carve, scrape,crush, and grind plant and animal tissue.

They also made tools with which to make other artifacts,such as drills, hammerstones, and polishers. They relied upona variety of fishing gear made from bone, marine shell, andstone. They fished from lines using hooks and gorges and usedharpoons as well. Archaeologists have found grooved stone netsinkers and specialized stones called poio in Chamorro which

34

10.03 Perspective Vol 2 2/15/04 11:04 AM Page 34

historic records indicate were used to lure and habituate fish toreturn to the same fishing spot.

That fighting between local groups occurred is clear fromevidence at late prehistoric sites which yield slingstoneweapons of stone and clay, sometimes buried in small caches.Other contexts in which slingstones have been found includeopen, grassy slopes in the island interior. From historicaccounts we know stones were used as weapons against theSpanish, and perhaps the open sites with numerous slingstoneswere the scenes of battles and/or practice areas.

Because of the lack of burials from earliest times, wehave no clues about the health and nutritional status of the first

35

10.03 Perspective Vol 2 2/15/04 11:04 AM Page 35

settlers, but skeletal remains from late prehistoric populationsare common. Several of these have been studied by physicalanthropologists. Their studies indicate that people were rela-tively healthy and strong. Still, it was a fact of life that manychildren did not live past eight or nine years of age. Death ininfancy was not uncommon. A large proportion of female buri-als are of women of child-bearing age. Among teenaged femaleburials, several were buried with an infant each, probably casu-alties of childbirth.

Teeth tend to be quite worn down in older individuals(some persons lived well over 50 years), but the overall rate ofcavities is low, suggesting a healthy diet. On the other hand,some individuals experienced periods of hunger and nutritionalstress, as revealed in growth patterns in the bones and teeth.Sub-lethal diseases such as yaws and leprosy, which leavelesions on the bones, were not uncommon.

The very robust bones of Chamorro men and women tes-tify to a physically demanding life. Several of the male skele-tons have healed bone fractures, perhaps from falls and otheraccidents. The range of variation in height, as estimated bymeasuring the leg bones and applying a formula derived fromliving Maori (natives of New Zealand), indicates that adultmales ranged in height from about 5'5" to 5'11" and adultfemales from 5'2" to 5'6". Thus, the story of Chamorro giants,like rumors of Mark Twain’s death while he was still alive, aresomewhat of an exaggeration. That Chamorros appeared largeand robust to early European travelers is not in doubt; however,it is also true that at that time the Europeans were rather shortand not in good health after long sea journeys.

While no skeletal remains have been found at the earliestsites, chemical analysis of human bones from sites dating tolate prehistoric times indicates that the Marianas diet was pri-marily vegetarian and that mainly inshore fish were consumed.As with skeletal remains, we have no physical evidence of theearliest subsistence practices, such as what crops were grownor collected, perhaps because such items have not been pre-

36

10.03 Perspective Vol 2 2/15/04 11:04 AM Page 36

served in the ancient deposits. However, younger prehistoricsites are yielding subsistence data, thanks to new laboratorytechniques.

Burned organic residues on pot sherds have been ana-lyzed microscopically and found to contain the distinctivelyshaped molecules of cooked taro starch. There is also micro-scopic evidence of domesticated rice in agricultural soils,which contain tiny silica particles from the cells of rice plants.Additionally rice grain impressions have been found in potsherds from sites in Guam, Rota, Tinian, and Saipan. Judgingfrom the type of pottery in which the impressions occur, and insome cases based on the radiocarbon dates on charcoal in thesame deposit as the grain-impressed pot sherds, it appears thatrice cultivation was part of a complex of traits adopted late inMarianas prehistory (c. A.D. 1,300 or 700 years BP).

37

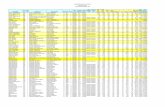

Figure 2.3 Rice spikelet impressions (arrows point tothem) in Marianas pottery sherds (MARS photo)

10.03 Perspective Vol 2 2/15/04 11:04 AM Page 37

Archaeological studies of artifacts from sites occupiedduring different time periods reveal changes in Marianas mate-rial culture over time. These changes include site locations, theway people made houses and pottery, and how they utilizedisland resources. The earliest evidence for house structurecomes from theUnai Chulusite in Tinian, a series of post holeswhose size and shape conform to wood posts. Later sites alsocontain post hole features, some in addition to stone posts (lattestones, discussed below) indicating that the use of wood forhouse supports continued throughout the prehistoric sequence.

The Marianas archaeological record shows that through-out prehistory wood pole-supported houses were built; theywere probably thatched with grass, palm fronds, or Pandanusleaves, as described in early historic accounts. Because thesematerials generally do not preserve well in the tropics, theyhave not been observed in the field, but microscopic study ofsoils in or near former structures might reveal such evidence.

It is legitimate to suppose that Marianas houses did notdiffer significantly in form or materials from those of othertropical Pacific island cultures, which all share the architecturalproblems of keeping the rain out, blocking the wind, and pro-viding privacy. These problems have been solved in similarways by converting local raw materials such as wood, stones,and leaves into suitable forms for roofing, walls, and flooring.Frequent replacement of organic house components wasprobably necessary due to the warm, wet climate and insectinfestation. Sites with several series of post holes in the samearea suggest such a process.

For longer-occupied structures (houses as opposed tosimple windbreaks and shelters) in the tropical Pacific, roofsare peaked, not domed, to minimize rain leaking through theporous thatch. Often the long ends of the roof extend beyondthe house ends to provide shade and to increase protected openspace. Floors of such structures are rarely flush with theground; rather they are elevated on stone and sand foundationsor on wood or stone posts. Elevating a house floor allows free

38

10.03 Perspective Vol 2 2/15/04 11:04 AM Page 38

flow of air beneath, prevents direct contact with any occupantsof the ground below the house, and provides additional livingand storage space there while keeping the building’s “foot-print” the same size.

Outdoor gravel work surfaces are sometimes created nearstructures and may be sheltered from the wind or sun byupright woven mats. These areas are used for visiting, generalhousehold work, tool making, and food preparation. Suchephemeral structures leave few physical traces but occasionallya gravel layer suggesting a floor or work surface is found at lateprehistoric sites in the Marianas. An early flooring or groundpreparation technique, found at Unai Chulu in Tinian, was tospread a hard, dense layer of clay over sand. It is not clearwhether the clay surface served as the floor of a structure or toseal the ground surface beneath an elevated structure. Suchclay floors have not been observed in later prehistoric sites,hinting at house design or space use differences at Marianasbeach sites over time.

As mentioned above, time differences have been found indifferent types of site locations; coastal areas contain all theearly sites whereas later sites have been found in interior set-tings as well. Even within coastal settings, the later sites areoften seaward of the early ones as beach areas grew with sealevel decline. Archaeologists are beginning to document otherenvironmental changes, through analysis of paleo-environmen-tal data such as fossil pollen and spores and identification ofancient wood used in hearths and house posts. Marine shellhabitats can be inferred from the types of mollusks present atarchaeological sites.

Archaeologists work with paleo-environmental special-ists and use these kinds of information (see above) to helpreconstruct the environmental setting of a site. For example,some marine food shellfish species grow in deep silty sand,while others flourish when their habitat is hard and firm, suchas a reef flat or reef edge. From analyzing the marine shells atcoastal archaeological sites, we are learning about shifts over

39

10.03 Perspective Vol 2 2/15/04 11:04 AM Page 39

time in the inshore habitats of ancient Chamorros because themarine shells they gathered reflect local conditions. A recentfinding from the identification of the marine food shells andancient wood from a 2,000 year-old site at Tumon Bay, Guam,suggests that mangroves were present then.

From comparative studies archaeologists have learnedalso that the kinds of pots made by the early settlers were dif-ferent from the pottery made in later times. The early potteryhas been termed Marianas Redware, after the red clay that

40

10.03 Perspective Vol 2 2/15/04 11:04 AM Page 40

was applied to the exterior surface of the pots. The vessels weretempered with coral beach sand and fired (baked) at a hightemperature. Laboratory reconstructions using pot fragmentsindicate they were relatively small vessels with flat or roundbottoms and vertical or slightly flaring rims.

A very small proportion of the pottery was decorated withfinely incised geometric designs filled with white lime. At firstthis decorated pottery was thought to be “trade ware” broughtin from elsewhere, but microscopic identification of the temperin the analyzed pottery indicates that it was made locally. It isstill possible that some of the Redware was imported; moreanalyses are needed to verify the earlier identifications. It is notclear whether food was cooked in these pots, which tend to be

41

10.03 Perspective Vol 2 2/15/04 11:04 AM Page 41

small, or whether they were used as containers for other itemsor materials.

42

Figure 2.6 Chart showing changes in Marianas pottery vesselforms through time (after drawing by Moore and Hunter-Anderson)

10.03 Perspective Vol 2 2/15/04 11:04 AM Page 42

Around 2,500 years BP, a new kind of pottery was addedto the Marianas repertory, represented by very robust vesselswith wide openings and short, vertical sides. Most were round,some were oval. The walls on these pan-like vessels were muchthicker than Marianas Redware; some of them were more thanan inch thick! The tempering material is coral beach sand, as inRedware, but these vessels appear to have been less durable,possibly because they were fired at a lower temperature. Therobust pans are undecorated, but the exterior surface of some ofthese vessels has woven mat impressions, as if they had beenwrapped in a mat before the clay hardened and the firing began.

It has been suggested that the robust pans were used inearth-ovens, covered or wrapped in leaves to protect the con-tents. The wide opening would let steam diffuse outward butthe bottom and sides would keep food in. A recent analysis ofancient organic residue on one of the robust pot sherds identi-fied cooked taro. The robust pans may also have been used toevaporate salt from sea water. An early account of salt makingin Guam states that canoes were used to evaporate much of thewater in the sun, and then it was boiled in pots to reduce theliquid still more. The wide opening in the robust pans couldhave helped to evaporate sea water quickly as it boiled. Madefor about 1,000 years, this robust pottery (as yet unnamed) andMarianas Redware were replaced by Marianas Plainware,which continued to be used into Spanish times.

Marianas Plainware, as its name implies, is plain,unslipped (without a special exterior surface), and usuallyundecorated. The exterior surfaces of many pots have variouspatterns of grooves and striations made by wiping or brushingthe damp clay prior to firing. Pottery analysts call this “surfacetreatment” but its function is unclear; was it decorative or prac-tical, or both? The tempering material in Plainware is usuallyeither volcanic sand or a mixture of volcanic sand and coralbeach sand. Vessels tend to be large, some over two feet indiameter. Bowl shapes are common, and they have slightlyincurving, very thick rims. Most Plainware pots were round

43

10.03 Perspective Vol 2 2/15/04 11:04 AM Page 43

with relatively high sides, but at the Taga site in Tinian oneunusual bowl has been found, which resembles the carvedwooden bowls of the Caroline Islands.

Chemical analysis of the food residues remaining onsome of the Marianas Plainware pot fragments confirms thatthey were cooking pots used to boil or steam taro over an openfire. Other Plainware vessel types include tall jars, probablyfor storing water. Why water storage would become moreimportant late in prehistoric times is not known, but changes inthe pattern of land use may have been involved. If people beganto stay longer in areas that lacked nearby surface water, forexample, in Guam’s northern forests, perhaps storing rainwaterfor site occupants became necessary. Longer stays would haveoccurred in the summer months when rainfall was most reliableand plentiful. Precisely when and why people stopped makingpottery in the Marianas is unknown. Perhaps, in part, it wasreplaced by metal pots and kiln-fired jars when they becamewidely available imports during Spanish times.

Non-ceramic artifacts such as shell and stone tools,fishing gear, and ornaments were made throughout prehistorictimes, but the types of artifacts and use of raw materials differover time. For example, in the early assemblages (before c.1,500 BP) shell ornaments (beads, armlets, and bracelets) aretypical; these items were fashioned mainly from cone shells. Inlate prehistoric assemblages (after c. 1,000 BP), beads are oftenpresent but bracelets and armlets are less common. Mainly thebeads are made from the orange shell of the spiny oyster(Spondylus). Carved shell pendants (probably from the giantclam,Tridacna), though rare, have been found at some sites.

It is not known whether the changes in the kinds of shellsused and in the types of ornaments made reflect changes in thekinds of shells available, or a difference in the social contextof ornamentation (for example, were the ornaments made bythe wearers or were they gifts; did they first mark kin groupmembership and later social status within the group?) or someother factor.

44

10.03 Perspective Vol 2 2/15/04 11:04 AM Page 44

Changes have been observed also in the raw materialsused for tools and implements from early to late prehistoricassemblages. For example, oyster (Isognomon) shell and giantclam shell artifacts are quite rare in early coastal assemblagesbut are common in late ones. At the late sites, a variety ofadzes, or axes, were made from giant clam shells and fromother hard mollusk shells. Probably these tools were used tomake canoes and to carve wood boxes and bowls. Often thesame sites yield knives, fish hooks, and gorges made fromIsognomon. Sometimes these items are unfinished, revealingthe various stages of the manufacturing process.

45

10.03 Perspective Vol 2 2/15/04 11:04 AM Page 45

Artifacts of hard volcanic stone are rare in the early siteassemblages and when they occur, are usually struck from alarger piece of rock so they could retain relatively sharp edges.The function of these items is unknown but probably was cut-ting or scraping. In contrast, late assemblages contain manymore items of hard volcanic stone, mostly basalt, some withsharp edges, but most of these artifacts are pecked and ground(hence the term, ground stone artifact) into cylindrical androunded forms. From their size and shape, they appear to havebeen used as sinkers, pounders, and adzes. Probably the largeststone adzes were used to fell trees; they are found at bothcoastal and inland sites. Also stone bowls and small mortars areamong common late prehistoric ground stone tools.

Other material domains whose study has revealeddifferences between early and late prehistoric sites are humanburials and above-ground features such as latte stones and largestone mortars. Human burials have not been observed in theMarianas earlier than c. 2,000 BP, and these cases are extremely

46

Figure 2.8 Stone adzes from Guam (MARS photo)

10.03 Perspective Vol 2 2/15/04 11:04 AM Page 46

rare. Later in prehistory, c. 1,000 BP, burial pits containing thegraves of adults and children are quite common, especially atcoastal sites. These sites usually contain evidence that latte stonestructures had been built in the same area as the burials. Largestone mortars occur frequently with latte stones and burials.

Many of the above temporal changes in ceramics andother types of prehistoric technology and cultural practiceswere first noticed and outlined systematically by AlexanderSpoehr, who worked in Rota, Tinian, and Saipan shortly afterWorld War Two. Spoehr suggested the terms “Pre-LattePeriod” and “Latte Period” to characterize the sequence ofmajor differences between early and late sites with their differ-ent artifact assemblages. Later surveys and excavations inGuam and in the other southern Marianas have confirmed thecontrasts found by Spoehr, and have provided more details.

In Spoehr’s two-part scheme, which is still in use today,the Pre-Latte Period began with human settlement of theislands, c. 3,500 BP, and ended c. 800 BP, if the inception oflatte stone architecture is used as the marker for the beginningof the Latte Period. Not all the traits associated with the LattePeriod appear in the archaeological record simultaneously,however. For example, changes that differentiate the Pre-LattePeriod pottery from LattePeriod pottery began to occur at least300 years earlier than lattestones, and while a large variety andgreat quantities of ground stone tools are typically found atLatte Period sites, ground stone tools began to be used withinthe Pre-LattePeriod.

A date for the “official end” of the prehistoric era andthus the “official beginning” of historic times (with some writ-ten record) is often taken to be the year of Magellan’s landing,1521 (dated from written reports by Pigafetta and others). Yetthis date for when history supposedly “began” in the Marianasis questionable because it applies obliquely to the aboriginalculture only. Writing was not even a common or significantmode of communication among Europeans in the islands untilperhaps 1668, when the Spanish established a colony at Agana

47

10.03 Perspective Vol 2 2/15/04 11:04 AM Page 47

(Hagåtña), and it is unlikely that any Chamorros were literateat that time.

When it is proper to say historic times began in theMarianas is less important for archaeology than to know whensignificant European contacts with local people occurred andwhat their effects were upon the local culture and its physicalremains (our subject matter!). For this, partially we can rely uponwritten accounts, but generally these documents contain littleinformation of use in explaining archaeological observations.

Archaeologists are especially challenged to recognize andinterpret sites utilized or occupied during the period of earlyEuropean/Chamorro interactions. For about a century afterLegazpi’s expedition in 1565, the Manila galleon trade broughtforeign goods to the Marianas but it is unclear how much ofthis material remained in the islands. Early accounts state thatiron in all its forms was highly desired by the Chamorros. Theywere able to work barrel hoops into cutting tools and nails intofish hooks, and knives and axes were prized especially.

At a few sites in Guam we have found small pieces of rustyiron and kiln-fired ceramics along with Latte Period ceramicsand other prehistoric features. When this association of materi-als is undisturbed at a site, we think it may represent an earlyhistoric simultaneous occupation. Interpreting these associa-tions is sometimes complicated by the presence of more recentmaterials such as ceramic roofing tiles and even glass, porcelain,and aluminum. These mixed deposits have been observed in theGuam coastal villages of Agana, Anigua, Asan, and Agat, wheremodern trenching for roadside utility lines has revealed them.

The various artifacts in these mixed deposits indicateresidential and commercial use of these coastal areas from theLatte Period through historic and into modern times. WhileLattePeriod occupations were residential, the historic activitiesrepresented by more recent artifacts relate to use of the westcoast of Guam for a major transportation route which wasperiodically upgraded and repaired. The disturbed nature of thesoils in and near the coastal road (due to World War Two battles

48

10.03 Perspective Vol 2 2/15/04 11:04 AM Page 48

and subsequent construction and rebuilding) does not allowdating of the artifacts by their stratigraphic position (in intact,non-mixed layers, lower items would be older than higher ones).

In many parts of the world, archaeology merges with his-tory in dealing with sites that are only 50 years old. In theMarianas, World War Two presently marks such a juncture.Historical archaeology is a specialty within the field. Thesespecialists work closely with historians and historic documentsto aid in the interpretation of their finds. The younger anarchaeological deposit or site is, the more likely that localarchives such as the Micronesian Area Research Center at theUniversity of Guam, as well as oral history, can help in itsinterpretation. Oral accounts of the experiences of long-timeresidents of the islands have been especially enlightening asarchaeologists seek a more comprehensive understanding ofour subject matter.

What is the Meaning of Latte Stones?

The lattestone symbol or motif, an upright pillar taperingtoward the top and supporting a globular, flat-topped capstone,is ubiquitous in the Marianas today. This motif is incorporatedinto public and private architecture, landscaping, clothing, jew-elry, toys, souvenirs, and graphic art. It symbolizes, to many,Chamorro culture past and present. That meaning granted,archaeologists still need to explain the rise and persistence oflatte stones during prehistoric times.

Latte stones were made from a variety of materials: reefrock near the shore (some beachside quarries have been found);older limestone from cliffs and terraces (a large inland quarry,the As Nievessite in Rota, is well known); tuffaceous sandstonefrom upland areas of southern Guam; and andesite, volcanicsandstone, and basalt boulders (the same materials from whichmost large stone mortars were fashioned). Generally, the stonesused in a latteset came from outcrops in the vicinity of the site,reflecting local geology. Sometimes more than one kind of

49

10.03 Perspective Vol 2 2/15/04 11:04 AM Page 49

stone was used in the same set, and we find latte sets withstones missing, perhaps recycled elsewhere. Occasionally anelongated mortar stone was used as a latte pillar; this wasobserved at the Alaguansite in Rota.

In their original configuration,latte stones were arrangedin sets of two parallel rows, each pillar with its own capstone.The two rows enclosed a rectangular space varying in sizeaccording to the number of pillars. Archaeologists have foundthat most lattesets had four or five pillars in each row, althoughsome had as many as seven pillars on a side. As the number ofpillars increased, the total enclosed space was increased, withthe width remaining the same. Among the lattesets which havebeen measured, most enclose about 600 square feet.Apparently the thickness of the capstones varied in order toadjust for slight differences in pillar height, bringing the entirestructure to about the same height.

While typically the pillars range from about three to fivefeet tall, some are very short (less than two feet high), others

51

10.03 Perspective Vol 2 2/15/04 11:04 AM Page 51

are exceptionally tall. The tallest lattes recorded in theMarianas are in Tinian at the House of Tagasite and in Rota attheAs Nievesquarry site, where many of the stones were neverremoved from the ground. The pillars at these sites range from14 to 17 feet tall and the capstones are about five feet thick andnine to eleven feet in diameter. Thus the total height of thesetallest combined pillars and capstones would have beenapproximately 20 feet. In contrast, most latte sets (pillar andcapstone combined) were only five to seven feet tall.

Clues to a practical function for lattestones are containedin some of the Spanish eyewitness accounts of the Marianaswhich indicate their use as house foundation-posts. The earliestreference to stone pillars supporting wood houses is from 1565,in an account of the Legazpi expedition at Guam. A later, morelengthy and detailed European account of life in Rota in 1602confirms the use of stone pillars as house supports. A mission-ary account from 1668 states that Chamorro houses rested onstone pillars. Thus, the purpose of latte stones as house sup-ports is not really mysterious; and it is not surprising that theyceased to be used under Spanish rule. By the early 1700s, peo-ple had been forced to abandon their traditional villages andlands and to adopt a new set of religious beliefs and practices.In the new parish villages, composed of families from all overthe Marianas, perhaps the customs associated with latte stonehouse construction and use could no longer be practiced.

The 1602 account of Rota describes the practice ofhuman burial near a latte house, and the close physical associ-ation of latte stones and human burials is well established byarchaeological field work. The association of human bones andlatte stones was noticed first by Hans Hornbostel, who exca-vated several latte sites at Tumon Bay, Guam. His interpreta-tion of latte stones was not informed by the historic literature,however, which clearly states their function as house supports.

Hornbostel supposed the latte features were monumentsor temples where cannibalistic rites took place involving thenewly deceased. Such a sensational view of ancient Chamorro

52

10.03 Perspective Vol 2 2/15/04 11:04 AM Page 52

culture was not unusual among Westerners in the 1920’s andevidently caused no stir or objection. Perhaps the idea that can-nibal feasts had taken place at lattesites seemed plausible fromthe following observations of the sandy soil surrounding theburials: it was stained dark and contained charcoal, ashes, andburned rocks. Many of the bones were darkened, someappeared burned, and not all the skeletons were found intact;some skulls and leg bones were missing.

Today, archaeologists recognize Marianas burials withmissing bones and non-articulated skeletons as secondaryinterments, which resulted from deliberate bone retrieval (fortool making and ancestor worship) and subsequent re-interment of the remains. These practices are in fact describedin Spanish missionary accounts of Guam, and are knownamong agricultural groups in southeast Asia where deceasedrelatives are venerated and current kinship ties are validatedthrough mortuary rituals. Multiple interments at the same loca-tion over time produce disturbance to earlier burials.

As for the dark, fire-affected soil surrounding the Tumonburials, archaeological analyses of similar soils from otherlatte sites at Tumon and elsewhere indicate they are theremains of outdoor cooking events (both above-ground hearthsand earth-ovens) combined with broken tools and discardeditems that accumulate normally in and near domestic struc-tures. Bones left in this soil environment for hundreds of yearsare likely to become stained and closely associated with ashesand charcoal, and some could be affected directly by fires.Some houses burned and were rebuilt, and cooking areasshifted over time within households at long-occupied sites.These activities could have disturbed old burial areas whoseprecise location has been forgotten.

More careful excavation techniques than those used byHornbostel in the 1920s have revealed that during the LattePeriod, the deceased were first placed in round or oval pits duga few feet into the ground. The bodies were laid on the side orback; some were flexed with knees bent. The pits were often

53

10.03 Perspective Vol 2 2/15/04 11:04 AM Page 53

lined with a layer of white beach sand. Sometimes large stoneswere placed over or around the head. The spatial proximity ofburials and dwellings, at least at coastal latte sites, suggests asocial context in which it was important to demonstrate clearlythe affiliations of the deceased with the lattestones. Burial cer-emonies held at the place of interment, near or in the latte set,whether for primary burial or secondary burial after boneretrieval, would call attention to this affiliation.

An archaeological discussion of latte stones cannot beconsidered comprehensive without an account of why theybegan to be used so late in prehistory, and of some otherintriguing aspects of their occurrence. For example,latte setshave been found in interior areas of Guam, Rota, Tinian, andSaipan but the cultural deposits associated with most of theseinterior sites are shallow and contain very few artifacts. Burialsare rare at these sites, another puzzling contrast with coastallatte sites. The inland latte sites often occur near freshwatersources, such as springs or wetlands. Some of these latte sets,like those at coastal sites, have large stone mortars nearby.

The simple interpretation of latte stones as house founda-tion stones does not explain why this architectural form wasadopted in addition to the previous house building mode, whichused wood house posts. Wood posts can elevate a structure justas stone posts can, and they are easier to handle (though lesslong lasting than stone in the tropical climate). Many of thelattestones are big, heavy, difficult to move, and perhaps not asstable as they appear. The wide base of the pillar was insertedinto the ground and kept upright in a shallow hole by a ring ofsmall rocks and dirt or sand. The combination of a wide andheavy capstone atop the tapering pillar would wobble and tendto fall over, and would seem vulnerable to earthquake damage.Perhaps the weight of a wooden superstructure on the latte sethelped to stabilize the stones.

To avoid these problems capstones may have been setatop the pillars only when a house was in place; otherwise theylay nearby. A practical function has been suggested for the

54

10.03 Perspective Vol 2 2/15/04 11:04 AM Page 54

hemispherical design of the capstone: the outward curve hasbeen likened to the wood disc “rat guard” that encircles the topof each wooden post of the elevated rice granaries used in thePhilippines. Capstones as rat guards in turn implies that lattehouses were used for storage of grain. Perhaps this is true, atleast for some of them; a 1669 account of Guam states that peo-ple kept “their seeds and precious things” in houses “raisedfrom the ground on top of big, round stones.” Still, given thedifficulties of obtaining, transporting, erecting, and maintain-ing latte stones, one has to wonder why people took so muchtrouble just to build a house or a granary using stone supports.The key to this puzzle may lie in the demographic and socialcircumstances of late prehistoric times in the Marianas.

The size of the Marianas human population c. 800 BP, thedate of the earliest known latte set, is unknown, but it ispossible that population had been increasing and was stilldoing so due to favorable crop growing conditions. Accordingto paleoclimatic studies of the period from c. 1,200 BP to 600BP, there was the Little Climate Optimum (LCO) era whenclimate was good for tropical agriculture and thus for MarianaIslanders who depended upon this mode of subsistence. Duringthe LCO , temperatures were higher and rainfall more reliablein comparison with earlier and later centuries. With relativelyhigh human settlement densities in the Marianas during theLCO , possibly augmented by new in-migrants from southeastAsia or elsewhere in Micronesia, productive land and specificresources such as forest tracts, interior wetlands, andproductive bays and lagoons would have become objects ofintense competition.

A general principle that helps us imagine what mighthave happened under these circumstances pertains to occupy-ing land physically as proof of ownership. Sometimesexpressed as “possession is nine-tenths of the law,” this meansthat there is little room for argument about ownership of a pieceof land when people are already occupying it and are preparedto defend it. But what if they cannot always be present on the

55

10.03 Perspective Vol 2 2/15/04 11:04 AM Page 55

lands they claim, because they are elsewhere in their territory,just when another group helps themselves to some of the unat-tended resources? Once or twice such an intrusion might betolerated, particularly if the intruders are relatives, but if suchevents become frequent, trouble is inevitable. Undesirable tres-passing events like these will increase as human densities rise.

A pertinent Marianas scenario under conditions ofincreasing human densities during the LCO includes settle-ment expansion into interior regions on the larger islands suchas Guam and into the smaller northern islands, the addition ofnew crops, and more intensive use of wild resources.Territories would become better defined as those areas wereused habitually within a seasonal round or over longer periods,such as decades. With keener competition for resources, main-taining territorial integrity would become increasingly prob-lematic. The defensive tactic of stationing people throughout agroup’s territory would not suffice because not all areas withinit were equally productive. A few people in each locale mightnot be effective defenders against a larger group.

Underlying such tensions is the subsistence effort thresh-old beyond which people would be hesitant to work in order toimprove yields. This threshold is determined by the operationof the law of diminishing returns. In agriculture, ecologistshave shown that usually each increment of increased effortresults in a smaller gain. Thus, people hesitate to intensify theirefforts when they see little payoff for doing so. The alternative,of increasing the size of the group’s territory but remaining atthe same level of effort, is more attractive.

The implication here is that once the subsistence effortthreshold was approached, there would be a simultaneous pres-sure to increase group territories, and all land-holding groupswould have to remain vigilant to deter land grabs by otherswhile trying to increase their own holdings. But if people spendmuch time defending and trying to take others’ land, there is notime actually to make a living from it! Given this reality, cul-tural conventions are adopted which regulate the near-constant

56

10.03 Perspective Vol 2 2/15/04 11:04 AM Page 56

competition for land and its resources and yet permit life to goon without nearly constant fighting.

A typical cultural convention that has been developedamong many tropical agriculturalists is the formation of shift-ing defensive and offensive alliances between land-holdinggroups. Because these alliances are unstable, fluctuating withgroup size and local circumstances, they need to be tested con-stantly, and ideally the tests do not interfer with “normal life.”

Such testing and validating of current alliances is accom-plished by holding periodic regional festivals which provideopportunities for groups to show their strengths and worthinessas current and potential alliance partners. These importantgroup characteristics can be gauged by participants who notethe amount and variety of foods and valuables displayed andexchanged during the festivals. In Yap these events are calledmit-mit. Early historic accounts of the Marianas mention simi-lar regional gatherings. Varying with the local customs, theycan include contests and displays of strength and cohesivenesssuch as wrestling matches between youths, spear-throwingcontests, and group singing and dancing.

Festivals not only entertain onlookers and challengeperformers but also provide a compelling reason to work harderduring the times between these events, which require partici-pants to present specific kinds and amounts of food and valu-ables. Thus, the festival system raises the level of productivework in a region, discouraging the resort to violent clashes overland. The system provides a venue for discussions and othersocial interactions to redress local people/land imbalances.

The festival system of regulating competition favors theinvention and production of “extras,” things that are not reallynecessary in a strict functional sense but which are greatlyadmired and appreciated. Items of value represent hard workand/or scarcity, and they are often perceived as beautiful.Impressive dance performances, weavings, even well preparedfood are “valuables” in this context because they are difficult toproduce and exhibit great skill. Even the commodity rice would

57

10.03 Perspective Vol 2 2/15/04 11:04 AM Page 57

have been such an item in the prehistoric Marianas where it isvery difficult to grow, requires great care and special soil con-ditions, and is subject to insect and rodent damage. It is inter-esting to note that archaeological evidence for its prehistoricpresence, while rare, dates no earlier than the LattePeriod.

Like rice, lattestones may have been added to the ancientChamorro culture as a “valuable” that proved the groupresponsible for obtaining the stones and erecting a house uponthem was strong, with an impressive command of labor andmaterials. If building a structure atop a latte set required evenmore wood and other materials than did simple pole houses,group strength to do it would be especially noteworthy. By thesize and number of latte sets with which a group or alliance ofgroups was associated, potential rivals and allies could gaugetheir strength. If it seemed great, probably rivals would desistfrom attempting to take their lands. By the geographic place-ment of the latte sets near claimed resources, people couldknow which areas were being claimed. Thus, with this under-standing of latte stones, we can expect them to have beenerected wherever important resources were contested and towhich specific groups laid continuing claims.

Under the Latte Period settlement system, it is unlikelythat every area in a group’s territory had year-round residents.The larger coastal sites, such as Tumon Bay in Guam, wereprobably occupied constantly, at least by some families, butmany inland areas could not sustain more than a few people,and probably not every year, due to droughts and typhoons.Inland areas may have been occupied by small numbers of peo-ple (caretakers) representing the larger land-claiming group,but their numbers would be insufficient to deter overt landgrabs by a larger competing group. With such a symbolic sys-tem as described here, the latte stones in such areas wouldspeak silently of the legitimacy of group claims to these areasand of the group’s ability to defend their claims if necessary.

A resource-claiming function for latte stones wouldexplain why many latte sites in the island interiors have little

58

10.03 Perspective Vol 2 2/15/04 11:04 AM Page 58

or no build-up of domestic midden. Actually people did notneed to live permanently on a given piece of land to be able toclaim it; the stones did that for them. For such a symbolic sys-tem to work, all have to adhere to it, and this seems to be thecase from limited archaeological data available. Latte stonesmade their appearance more or less simultaneously rather thanfirst in Guam and later in Saipan, and latte sets have beenobserved in the far northern island of Pagan.

The latte stone custom may have been one of severalwhich helped to solve social problems associated with highhuman densities during the LCO . As indicated above,lattestones were most likely not an isolated practice but one thatwas closely integrated with others, such as the festival system,primary and secondary burial of relatives in house areas, ricecultivation, and the use of large stone mortars. Someresearchers have suggested that the different sizes of latte setsindicated social differences within and between groups. Socialranking may be one more aspect of the late prehistoric culturalsystem which relates to the regulation of competition for land.

Clearly there is much, much more to the story of theancient Chamorros of the Marianas. Archaeology is but oneavenue we have just begun to travel for the purposes of describ-ing and explaining this history. Another avenue is linguistics, thestudy of languages and their inter-relationships. Archaeologistsconsult the findings of historical linguistics and vice versa, informulating scenarios about the past. Progress is being made inall these fields, and the learning journey has started in earnest.

For those who would embark on these studies, rememberour subject will remain mysterious if we forget to use ourimaginations in the presence of clues which are all around!Also remember that in science, imagination is tempered bylogic and the need to test our ideas in the real world of physi-cal facts. For this reason, students interested in the past needopen access to the archaeological record, which is a very spe-cial kind of archive that must be curated responsibly, as well asto the other empirical domains into which our ideas may lead.

59

10.03 Perspective Vol 2 2/15/04 11:04 AM Page 59