Ridge–hotspot interaction: the Pacific–Antarctic Ridge and the foundation seamounts

The Archaeology of Archaeology: 2012 Excavations at Alkali Ridge Site 13

Transcript of The Archaeology of Archaeology: 2012 Excavations at Alkali Ridge Site 13

The Archaeology of Archaeology: 2012 Excavations at Alkali Ridge Site 13

James R. Allison Department of Anthropology

Brigham Young University

Draft April 2013

Paper presented at the 78th Annual Meeting of the Society for American Archaeology, Honolulu, Hawaii

PLEASE DO NOT CITE IN ANY CONTEXT WITHOUT PERMISSION OF AUTHOR

Alkali Ridge Site 13 is one of the largest and most extensively excavated Pueblo I villages

in the Northern Southwest. It also is one of the earliest Pueblo I villages in the Mesa Verde

region, dating to the late A.D. 700s. The site was first excavated in 1932 and 1933 by J.O. Brew

of Harvard University, who dug all or part of 118 storage rooms, 11 pit houses, and 25 surface

habitation rooms belonging to the early Pueblo I component (SLIDE 1, site map).

Brew’s excavation methods were crude by modern standards, but his report was n many

respects ahead of its time. There is much to criticize about 1930s excavation and

documentation methods, but they allowed a broader view of the site than is usually possible

with modern (slower and more detailed) excavation techniques.

In 2012, with the help of students and volunteers, I returned to the site to reexcavate

several storage rooms and do limited testing into previously undisturbed rooms. One goal of

this paper is simply to report our findings, but the new excavations also provide the opportunity

to compare the results of modern excavation techniques and those used in the 1930s.

We began our excavation in a series of five store rooms near the south end of the site,

Rooms 73-77 in Brew’s report (SLIDE 1.1[Animation to show location of rooms]). These rooms

were not backfilled after Brew excavated them, and the slab walls were poorly preserved and in

need of stabilization (SLIDE 2 Rob in rooms in 2009). The excavated store rooms are not

individually described in the report, and I had several questions about these particular rooms

and adjacent areas. So, rather than just backfilling the rooms, we decided to reexcavate them

first.

I hoped to answer several specific questions. First, were the rooms built all at once, or

were some added accretionally to earlier ones? The original excavation map shows only the

insides of the walls, depicting each room as an isolated unit, although the rooms clearly shared

walls. Therefore, I wanted to look at the ways walls met in order to understand the

construction sequence. Second, in some parts of the site Brew had excavated surface

habitation rooms in front of (that is south or east of) the rows of storage rooms. In other parts

of the site, including where we were working, he apparently made little or no effort to excavate

the surface habitation rooms, but depicted their inferred presence on the site map with a

dashed line in front of the excavated store rooms. But why didn’t he excavate them? The ones

he did excavate had shallow floors and relatively insubstantial walls, so maybe they were too

poorly preserved to excavate. Or, were they not really there at all?

Finally, the map shows some of the store room walls with dashed lines, including the

majority of Rooms 73 and 77. This apparently was because those two rooms were incompletely

excavated, but there was no clear documentation of how much was left unexcavated in those

rooms.

Brew’s 1932 field notes (SLIDE) were not much help in answering these questions; this is

all there is for those five rooms. A couple of things are notable here: Brew notes that, contrary

to his expectations, the rooms were not just post and adobe construction, but were slab-lined

with posts in the corners to help support the roof. He also notes that the “plaster burned, and

[the rooms] have much corn.”

The notes make little mention of the artifacts, although they do note that there is no

corrugated pottery (a significant observation for understanding the the site’s chronology, as

indicated by the underlining), and that most of the pottery is “red and buff”. The red and buff

pottery that Brew refers to is what later came to be called Abajo Red-on-orange (SLIDE), which

is the predominant painted pottery on the site. No mention is made in the notes of

reconstructible vessels (SLIDE), although Brew recovered two Abajo Red-on-orange vessels

from Room 75: a squash effigy and a very large bowl (which I think is literally the largest early

Pueblo I bowl anyone has ever found).

The 1932 field photos (SLIDE) are a bit more helpful than the notes. This photo, for

instance, shows Rooms 74, 75, and 76 after excavation--- note the backdirt piled on either side

of the rooms, and the irregular trench south of Rooms 75 and 76, paralleling their south wall.

That trench is never mentioned in either the field notes or the report, but it’s right where a

surface habitation room should be.

Here’s a photo taken from about the same location (standing on Room 73) just prior to

the start of our 2012 work (SLIDE), and again after we removed the sage brush (SLIDE). The

1932 backdirt piles on either side of the rooms are still visible, although much of the backdirt

had washed back into the rooms. As this profile shows (SLIDE) the fill was surprisingly well

consolidated and not obviously recent, even though we know the room was completely

excavated in 1932.

We found a few surprises when we reexcavated Rooms 74-76. For one (SLIDE), the

postholes had clearly not been excavated, and this mano was left on the floor of Room 74. Not

only were the postholes not excavated(SLIDE), but one still had a post sticking out of it, and

there were several other small pieces of wood (probably from posts) in the rooms.

Reexcavation of the store rooms exposed the slab walls and, although the walls were

poorly preserved (SLIDE), it is clear that the five store rooms were built as a unit, with the long

parallel north and south walls built first and cross walls added in later. This was clearest in a few

cases (SLIDE) where the cross wall intersected the outer wall in the middle of a slab, but it

appears to be true for all four of the cross walls we were able to examine.

In Room 73, one of the rooms where the extent of excavation was unclear, this photo

(SLIDE) shows a small, irregular excavation in the northwest corner of the room. We were able

to find and reexcavate the 1932 pit(SLIDE), which had relatively well-defined edges despite its

irregular shape, and confirm that, in fact, that was all that was excavated in that room. For

Room 77, the other room for which the extent of excavation was unclear, photos were less

helpful (SLIDE) although again they suggest a relatively informal, irregularly shaped test into the

southeast corner of the room. Here too (SLIDE) we were able to follow the edges of the 1932

excavation and confirm that the majority of the room was unexcavated. In Room 77 we

expanded our excavation into previously undisturbed fill (SLIDE) and found that the room

clearly burned.

So what about the possible surface habitation rooms (SLIDE) to the south of these

storage rooms?; and what was going on with this trench?. The trench also appears in this view

(SLIDE) of Room 75, although neither photo shows the size or shape of the trench very clearly.

One other photo (SLIDE) shows a reconstructible jar in situ in what must be the same trench

(here’s a recent photo of the reassembled jar, which is at Harvard); this suggests something

south of the storage rooms, but leaves unanswered the question of whether habitation rooms

are really present there.

To explore these questions(SLIDE), we ran a 1- m wide trench here, south from the cross

wall between Rooms 75 and 76. (SLIDE) The stratigraphy in the excavated trench presents a

relatively clear picture: the 1932 ground surface is at the top of a thin layer of windblown sand;

above that is what is apparently backdirt from the 1932 excavations; the edge of the 1932

trench is clear near the north end of our trench; and below the windblown sand is a layer of

(mostly) burned adobe and charred material, which is apparently the fill of a burned room.

At the bottom of the trench we uncovered what appears to be a floor with a metate

resting on it, and a mano directly on top of the metate. (SLIDE) From a different angle (in an

earlier photo with the profile across the trench still intact), you can see that the metate and

mano are sitting next to a (partially uncovered) slab-lined hearth. All this suggests that at least

one surface habitation room is in fact present south of Rooms 75 and 76, with artifacts left is

situ on the floor.

(SLIDE everything excavated) So, through reexcavating a few of Brew’s old excavations

and a very limited amount of new excavation, we were able to answer the three questions I

started with: the store rooms in this part of the site were not added accretionally but were all

built in a single episode; Brew’s excavations into Rooms 73 and 77 were very limited, leaving

most of the fill of those rooms still intact; and there almost certainly is at least one surface

habitation room south of these rooms, underneath backdirt from the 1932 excavations.

We also learned a few things about Brew’s collection (and non-collection) strategies. As

I noted earlier, his field notes say these rooms contained “much corn”, but the report makes no

mention of maize from here. We only excavated limited amounts of the 1932 backfill, but

where we did we found so much charred maize that it was impossible to pick it out of the

screen. In particular, this little bit of excavation yielded many thousands of kernels and a few

cob fragments. Clearly there was a lot of maize in the rooms when they burned.

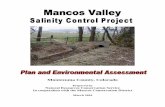

It’s also interesting to look at the ceramics. Brew collected 412 potsherds from the area

we worked in: 46 percent were red ware, 2 percent white ware, 52 percent rest gray ware. He

says in the report that red ware outnumbers white ware 1000 to 1 at the site; I don’t think that

was meant to be taken literally, but that ratio is 24 to 1 in Brew’s collections from this area. We

recovered almost 1800 sherds from our excavations, most of which came from screening

Brew’s backdirt. Over 70 percent of our sherds were gray ware, 28 percent red ware, and less

than 1 percent white ware (red/white ratio about 49:1). If you put the two samples together,

the red/white ratio is something like 36 to 1. Brew’s collection is clearly not representative; it’s

biased toward decorated sherds and although he collected only a few white ware sherds, the

red/white ware ratio is much lower than in the overall sample.

What is the point of all this? It isn’t to complain about Brew’s excavation methods; they

were good for the time even though (I hope) no professional archaeologist today would

emulate them. By carefully focusing on a specific part of the site, we were able to learn quite a

bit about it, including things not noticed (or at least not recorded) when the site was first

excavated. But, while the modern-day focus on careful excavation is important and almost

always appropriate, it’s also important to notice that it sometimes channels our attention and

thinking in unproductive or misleading ways; as archaeologists squeeze more and more

information from small data sets we risk losing site of the bigger picture. Or worse,

archaeologists either misperceive the big picture by extrapolating from small, well studied, but

completely unrepresentative samples; or they confuse very detailed pollen studies,

reconstructions of diet, or elegant models of foraging behavior, or whatever, with the big

picture when they are often just high resolution thumbnails.

Brew collected biased samples, or no samples, of ceramics, maize, chipped stone and

other common artifact types, he collected no flotation or pollen samples, and very little faunal

bone, and he recorded limited information about the architecture of the site. But even so Brew

still seems to have gotten the big picture right. He saw Site 13 as a village housing people with

diverse backgrounds that was destroyed by fire before the inhabitants had a chance to recover

food and other belongings from their store rooms. And he collected data that I have used to

examine, for instance, (SLIDE) the strong spatial patterning within the village of different store

room construction techniques, the extent of the burning that destroyed the village (SLIDE)(all

the black rooms and probably the gray ones), or (SLIDE) the diversity of designs on Abajo Red-

on-orange bowls and the similarity of those designs to ceramic designs from the southern part

of the Southwest.

These are things we could never learn from our small, carefully excavated sample; with

our methods it would take decades (at least) to see as many walls, burned rooms, or ceramic

designs as Brew did. He was able to get many things right in his interpretation of Site 13 not in

spite of what we might today see as shoddy excavation techniques, but because of them. They

allowed quick excavation of many rooms and allowed recovery of large samples of uncommon

artifacts.

To be clear, I am not arguing for a return to faster, less controlled field methods or less

detailed documentation. What I am saying is that to really understand what happened in

prehistory we need to think beyond the confines of our high quality, but potentially narrow and

unrepresentative data sets. It is easy to point out the weaknesses of older data, but more

difficult to see the weaknesses of our own methods. It’s also important to recognize that the

scale of that early research--- the ability to dig a lot rapidly and to see a lot--- was a great

strength. Ethical and practical considerations will usually keep archaeologists today from

digging as quickly and as much as Brew and others of his era were able to, but we must find

ways to see as much as, or more than, they saw. That means we must pay attention to museum

and archival collections, and to the history of archaeology, and we must be willing to work with

poor quality data, if necessary, as a supplement to new data collection.

The Archaeology of Archaeology2012 Excavations at Alkali Ridge Site 13

James R. AllisonBrigham Young University

1932 Trench 1932 Backdirt1932 Ground Surface

Floor

MetateOn Floor

Excavation stopped above floor(to be completed 2013)

Mano on Metate

Roof Fall/Wall Melt

Aeolian Sand

Combined2012 Excavations1932 ExcavationsWhiteRedGrayWhiteRedGrayWhiteRedGray

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

Perc

ent