Some Observations about the Form and Settings of the Basilica of Bargala

Transcript of Some Observations about the Form and Settings of the Basilica of Bargala

EDITORIAL BOARD:

Boban PETROVSKI, University of Ss. Cyril and Methodius, Macedonia (editor-in-chief)Nikola ŽEŽOV,University of Ss. Cyril and Methodius, MacedoniaDalibor JOVANOVSKI,University of Ss. Cyril and Methodius, MacedoniaToni FILIPOSKI,University of Ss. Cyril and Methodius, MacedoniaCharles INGRAO,Purdue University, USABojan BALKOVEC,University of Ljubljana,SloveniaAleksander NIKOLOV,University of Sofia, BulgariaĐorđe BUBALO,University of Belgrade, SerbiaIvan BALTA,University of Osijek, CroatiaAdrian PAPAIANI,University of Elbasan, AlbaniaOliver SCHMITT,University of Vienna, AustriaNikola MINOV,University of Ss. Cyril and Methodius, Macedonia (editorial board secretary)

ISSN: 1857-7032© 2012 Faculty of Philosophy, University of Ss. Cyril and Methodius, Skopje, Macedonia

University of Ss. Cyril and Methodius - SkopjeFaculty of Philosophy

Macedonian

Historical

Review

vol. 32012

Please send all articles, notes, documents and enquiries to:

Macedonian Historical ReviewDepartment of HistoryFaculty of PhilosophyBul. Krste Misirkov bb

1000 SkopjeRepublic of Macedonia

http://mhr.fzf.ukim.edu.mk/

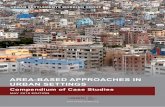

Nathalie DEL SOCORROArchaic Funerary Rites in Ancient Macedonia: contribution of old excavations to present-day researchesWouter VANACKERIndigenous Insurgence in the Central Balkan during the PrincipateValerie C. COOPERArcheological Evidence of Religious Syncretism in Thasos, Greece during the Early Christian PeriodDiego PEIRANOSome Observations about the Form and Settings of the Basilica of BargalaDenitsa PETROVALa conquête ottomane dans les Balkans, reflétée dans quelques chroniques courtesElica MANEVAArchaeology, Ethnology, or History? Vodoča Necropolis, Graves 427a and 427, the First Half of the 19th c.Dimitar LJOROVSKI VAMVAKOVSKIGreek-Macedonian Struggle: The Reasons for its OccurrenceStrashko STOJANOVSKINational Ideology and Its Transfer: Late Ottoman and Austro-Hungarian RelationsNikola MINOVThe War of Numbers and its First Victim: The Aromanians in Macedonia (End of 19th – Beginning of 20th century)Сергей Иванович МИХАЛЬЧЕНКОКоролевство Сербов, Хорватов и Словенцев глазами русского эмигранта:традиции и политикаBorče ILIEVSKIThe Ethnic and Religious Structure of the Population in the Vardar part of Macedonia according to the Censuses of 1921 and 1931Irena STAWOWY-KAWKAAlbanians in the Republic of Macedonia in the years 1991-2000

7

15

41

65

85

95

117

133

153

193

203

219

TABLE OF CONTENTS

УДК 904:726.54(497.731)

Some Observations about the Form and Settings of the Basilica of Bargala

Diego PEIRANO

Casa Città, Politecnico di TorinoTurin, Italy

Some years ago, in a survey about the barriers between nave and aisles,Urs Peschlow quoted the Basilica of Bargala as an example of a Church withside aisles screened from the nave (fig. 1). This article was, as stated by the au-thor, the “first attempt to assemble the material evidence and to raise questionsabout the purpose of constructing barriers between the nave and aisles”1. Infact, as the author himself observes, despite the large number of basilicas keep-ing traces of these devices, such arrangements have never caught the attentionof scholars, and these churches had never been analysed as a group2.

With respect to the first assertion, I would point out as in recent years,my researches about the form and settings of some Early Christian churches ofAsia Minor led me to me to investigate similar arrangements of a wider area thathas his barycentre in the Aegean sea; all these basilicas are included in a data-base3. So, afar from the examples advanced by Peschlow, the catalogue of basil-icas provided with barriers can be greatly increased: of 469 churches recordedin database 71 had certainly such dividers.

1 Urs PESCHLOW, “Dividing Interior Space in Early Byzantine Churches: The Barri-ers between the Nave and Aisles”, in Thresholds of the Sacred, ed. Sharon E.J. Gerstel, (Washington D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks, 2006), 54.

2 PESCHLOW, “Dividing Interior Space,” 54.3 The database was created with the intention to define – as much as possible and col-

lecting data on distributive aspects, furnishings, materials and decorations – theperception of the Aegean Early Christian basilicas in the various actors of theliturgy. This work is still under preparation by a group coordinated by the pres-ent writer.

Diego PEIRANO

The transennae dividing the interior of basilicas were assembled in twodifferent ways: using insertion slots cut into the bases (fig. 2) or leaving an un-finished strip on the moulding4, and modelling thus the low angles of slabs. Oc-casionally, some chiselled strips are visible on the stylobate where the slabs areplaced.

As underlined by Peschlow, the division of churches, by means of clo-sure slabs, is the main evidence that the faithful within the church was set apartfrom one another5. But which kind of laypeople? Historical sources referred ofmany faithful categories kept separated, because of gender, initiation stage, agesand even more6. Other sources reported some troubles to orchestrate the move-

66

4 These two systems are both attested in the Beyazit basilica at Constantinople.PESCHLOW, “Dividing Interior Space,” 54.

5 PESCHLOW, “Dividing Interior Space,” 54.6 Constitutiones apostolorum. II, 57, 3 ff: The lector shall stand in the middle, on an

eminence, and read the books of Moses and Joshua, son of Nun, of the Judgesand the Kings. [...] 10. The janitors shall stand guard at the entrances [reserved]for men, and the deacons at those [reserved] for women, in the guise of ship'sstewards: indeed, the same order was observed at the Tabernacle of Witness.[...] 12. The church is likened not only to a ship, but also to a sheepfold (man-dra). [...] Richard Hugh Connolly, trans., Didascalia apostolorum (Oxford:Clarendon Press, 1929), 119-20, quoted on: Cyril Mango, The Art of theByzantine Empire 312-1453 (Toronto, Buffalo, London: University of TorontoPress, 1986), 24-25. Testamentum Domini I, 19: Let the church have a housefor the catechumens, which shall also be a house of exorcists, but let it not beseparated from the church, so that when they enter and are in it they may hearthe readings and spiritual doxologies and psalms. Then let there be the thronetowards the east; to the right and to left places of the presbyters, so that on theright those who are more exalted and more honoured may be seated, and thosewho toil in the word, but those of moderate stature on the left side. And let thisplace of the throne be raised three steps up, for the altar also ought to be there.Now let this house have two porticoes to right and to left, for men and forwomen. [...] And as for the Commemoration let a place be built so that a priestmay sit, and the archdeacon with readers, and write the names of those who areoffering-oblations, or of those on whose behalf they offer, so that when theholy things are being offered by the bishop, a reader or the archdeacon mayname them in this commemoration which priests and people offer with sup-plication on their behalf. For this type is also in the heavens. And let the placeof the priests be within a veil near the place of commemoration. Let the House

Some Observations about the Form and Settings of the Basilica of Bargalaments of so many groups7; and, in addition to that, we should remember thatChurch fathers firmly insisted on the careful development of the rites, againstover-enthusiastic faithful attitudes8.

The diffusion of these screens appears extremely wide: only limited tothe mentioned east Mediterranean areas, we can find evidence of intercolum-nar screens in continental Greece9 and in the Islands10, Asia Minor11, Cyprus12,

67

of Oblation (chorbanas) and treasury all be near the diakonikon. And let theplace of reading be a little outside the altar. And let the house of the bishop benear the place that is called the forecourt. Also that of those widows who arecalled first in standing. That of the priests and deacons also behind the baptis-tery. And let the deaconesses remain by the door of the Lord's house. Quotedon: MANGO, “Art of Byzantine Empire,” 25.

7 Paul Silentiarius in his description of the ambo S. Sofia (563 AD) offers an evocativeparallel between the solea, against which presses the crowd trying to touch thebook, and an isthmus, hit by the waves on every side. Paulus Silentiarius, “De-scriptio ecclesiae sanctae Sophiae et ambonis”, in Leontii Byzantini, Operaomnia. Accedit Evagrii Scholastici Historia ecclesiastica, vol. 86.2 of Patrolo-gia Graeca, ed. Jacques Paul Migne (Paris: 1863), 250.

8 Iohannes Chrysostomus, “In Matthaeum homilia”, in Johannis Chrysostomi opera,vol. 58 of Patrologia Graeca, ed. Jacques Paul Migne (Paris: 1862), 744-46; Io-hannes Chrysostomus, “In epistolam I ad Corinthios homilia XXVIII”, in Jo-hannis Chrysostomi opera, vol. 61 of Patrologia Graeca, ed. Jacques PaulMigne (Paris: 1859), 231.

9 We find these arrangements in Attica at Athens (basilicas built in the Parthenon,Erechtheum, Olympeion, Ascleipieion), Alimos, Brauron, Gliphada, Eleusis(Ay. Zacharias); in Corinthia in some basilicas of Corinth (St. Codratos,Lechaion) and neighbouring centres as Sycione; in Argolid at Argo (Aspis basil-ica), Nemea (basilica of sanctuary), Epidauros, Hermione; in Thessaly atDemetrias (basilica A) and Nea Anchialos (basilicas A and G). In addition tothese we must remember: in Laconia the basilica of Tigani; in Elis, at Olympia,the Basilica in the Pheidias’ workshop.

10 In Spetses at Vrousti. At Delos in the basilica of St. Kyriakos. In Crete at Kolokythia,Olous-Spinalonga (Island basilica), Eleutherna. In Lesvos in the basilicas ofMesa, Skala Eressos (Ay. Andreas, Aphentelli), Ypselometopes. In Kos in theGabriel basilica, and in the churches of Zipari, “of Stephanos” (basilica north)and Mastichari. At Paros in the basilicas of Ekatontapyliani and Tris Ekklesies.

11 In Constantinople in St. John of Studios, Beyazit (basilica A). In Ionia in the basilicaof St. John in Ephesus and in Priene. In Phrygia in Laodicea (basilica behindthe Temple A), and in the Bishop’s church of Phrigian Hierapolis. In Lycia at

Diego PEIRANO

Balkans13; then adding – of course – some Macedonian examples that we willanalyse in the following lines as well. Despite the lack of basilicas reliably dated,the number of attestations made some scholars believe that this practice wasborn in Greece14.

According to Peschlow, the bases intended for receiving the slabs wereprefabricated; this clearly demonstrates that the division had been previouslyplanned15. I would even say that in building then adapted as basilicas, we can findthe same arrangements16.

Peschlow draws out that as these devices could make a distinction in theuse of the interior space of a basilica, a very common plan indeed17; further-

68

Andriake (basilica B), Xanthos (basilica behind the agora), Alakilise. In Pam-phylia at Perge. In Caria at Aphrodisia (cathedral), Iasos (agora basilica), Bar-gylia (basilica A and B), Knidos (basilica on the Dionysos temple, basilica A),Kaunos (domed basilica), Labraunda (west basilica). The last two had inter-columnar screens made with raw blocks. Jasper BLID, Olivier HENRY, LarsKARLSSON, “Labraunda 2010, preliminary report,” Opuscula. Annual of theSwedish Institutes at Athens and Rome, 4 (2011): 39.

12 At Kourion (Cathedral) and in Marathovouno.13 In Dardania at Caricin Grad (Transept basilica) and a Bregovina. On these: Tamara

OGNJEVIĆ, “Ikonografija i simbolizam podnog mozaika glavnog brodajužne bazilike u Caričinom gradu,” Leskovački zbornik, 47 (2007): 49-72;Miroslav JEREMIĆ, “La sculpture architecturale de l’église de Bregovina (Vies. ap. J.C.) en Serbie du Sud,” Starinar 53-54 (2004): 111-137.

14 Thomas MATHEWS, The Early Churches of Constantinople. Architecture andLiturgy (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1971), 125;Peschlow, “Dividing Interior Space,” 56.

15 PESCHLOW, “Dividing Interior Space,” 54. Later the same author gives an examplewith different mean with the basilica extra muros in Philippi. Here, the churchof mid-fifth century allowed passages between nave and aisles, but during a re-construction in early Justinianic times a stylobate (height 0.65 m) was built inthe intercolumns. Something similar happen in museum basilica of the samecity and in the Cathedral of Stobi. See: Peschlow, “Dividing Interior Space,” 68and note 35; below note 56 and the corresponding text. Demetrios PALLAS,Les monuments paléochreétiens de Grèce découverts de 1959 à 1973 (Roma:Pontificio Istituto di Archeologia Cristiana, 1977), 110.

16 For example the Athenian basilicas of Parthenon, Erechthieum, Olympeion, Ascle-pieion, and in Olympia in the basilica built in the Pheidias’ workshop.

17 PESCHLOW, “Dividing Interior Space,” 54.

Some Observations about the Form and Settings of the Basilica of Bargalamore, these barriers seem – along with others divisors – intended for charac-terizing some churches’ interior spaces where floors, revetments, choices of ma-terials, are very different18. Nevertheless, we should take into account that bar-riers, chancels and curtains, prevented people from clearly seeing, so their per-ception of the building could be quite different, as if there were differentchurches within the same basilica.

The use of barriers not only characterizes traditional basilicas but alsothose one provided with transept19, some central churches20 or baptisteries21.

These divisors are not visible in the smaller Byzantine basilicas where thelack of space should limit the use of inner separations. In these devices, peoplecould move from nave to aisles by an entrance placed in the stylobate; this latterhad a greatly varied height but mainly form 0.2 and 0.3 meters22. These passages

69

18 The partial publication of excavations data and the poor state of conservation formany of these examples are the main obstacles to understanding these features.Nevertheless naves with large presence of marbles elements and aisles deco-rated with painted plaster are recognizable in Argolid at Hermione, at Kos(Mastichari), in Ionia at Priene, in Caria in the domed basilica of Kaunos, in theAgora basilica of Iasos, in the terrace basilica of Knidos, in Phrygia in theCathedral of Hierapolis.

19 In addition to side barriers amidst nave and aisles, here we find these separation alsobetween the main sector and the sides of transept: see for examples the basili-cas of St. John at Ephesus, A in Perge and A in Philippi.

20 Maybe in the so-called “Rotunda” of Konjuh (Macedonia). On this: Reallexikon zurByzantinische Kunst, s.v. “Makedonien”, 1069-1071; Carolin S. SNIVELY,“Archaeological Investigation at Konjuh, Republic of Macedonia, in 2000”,Dumbarton Oaks Papers 56, (2003): 297-306, especially 302-305; LjubinkaDŽIDROVA, “Art, Form and Liturgy in the Rotunda at Konjuh”, in Niš andByzantium 5, ed. Miša Rakocija (Niš: 2007), 149-178. The last two contributesdoesn’t mention these separations.

21 As in the church – former baptistery – of St. George in Kos. On this: Hermes BAL-DUCCI, Basiliche protocristiane e bizantine a Coo (Egeo), (Pavia: 1936), 47-51 and fig. 40. Here these separations seems hinder the access to some of theradial niches. Two transennae were also provided in front of the pool in theEpiscopal basilica of Kourion. On this: Arthur Stanley MEGAW, Kourion. Ex-cavation in the Episcopal Precint, (Washington D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Stud-ies, 2007), 110.

22 Anastasios ORLANDOS, E xylostegos palaiochristianike. Basilike tes mesogliakeslekanes: melete peri tes geneseos, tes katagoges, tes architektonikes morphes

Diego PEIRANO

were usually limited in the west and east extreme of colonnade. These latterspaces seem to be connected to Communion administration. In fact, in thebiggest churches, where the bema frequently assumes the “Π” shape detachingfrom stylobates, these passages correspond to the chancel placed on the pres-bytery’s sides; as we can see in many basilicas in different areas: Greece23, AsiaMinor24, Cyprus25, but also in Macedonia. In the following passages we willanalyse these last examples.

These devices were also sometimes supported by different pavementlevels giving a sort of naves’ hierarchy. By comparing the side aisles, Peschlownoted that – in terms of both floor height and decorative treatment – it was oftengiven great attention to the north aisle26; this despite the common believe thatthe this latter was only for women and, thus, less important: among these ex-amples we can find the Basilica of Bargala that we see better later27. What I’drather want to point out is that north aisle was not only intended for women; inthe Phrygian Hierapolis bishop church – where I’ve been working since 2002 upto 2008 – there was an asymmetric disposition with barriers placed only betweennave and south aisle (fig. 3-4). So everybody could move from the nave to thenorth aisle. This had some consequence on the dispositions of the bema, pre-senting the “Π” shape, quite common among medium-large dimension basili-cas indeed: while the south side had a chancel allowing the administration ofCommunion, the north side keeps a round hollow that seems to be related to atable foot.

70

kai tes diakosmeseos ton christianikon oikon latreias apo ton apostolikonchronon mechris Iustinianon (Athen: Archaiologikes Etaireias, 1952-1956)264. Orlandos remarks how the height of these varied from as low as 0.06 m inthe Acheiropoietos in Thessaloniki to 0.60 m in the church in the workshop ofPheidias at Olympia. This last for others authors measures 0.85 m height. C. J.A. C. PEETERS, De liturgische dispositie van het vroegchristelijk kerkgebouw(Assen: Van Gorcum, 1969 ), 131.

23 In the basilicas A, C and probably “of Martyrs” in Nea Anchialos, and in the Aphen-telle basilica of Skala Eressos in Lesbos.

24 In Constantinople in St. John of Studios and in S. Euphemia. At Bishop’s church ofPhrygian Hierapolis. In Lycia in the cathedrals of Lymira and Xanthos.

25 At Salamina in the Campanopetra basilica. On this: Georges ROUX, La basilique dela Campanopetra (Paris: De Boccard, 1998).

26 PESCHLOW, “Dividing Interior Space,” 66.27 PESCHLOW, “Dividing Interior Space,” 66.

Some Observations about the Form and Settings of the Basilica of BargalaAccording to Pallas28 the presence of secondary altars seems related to

the existence of entrances in the east wall of the church: from there, before themass, the male faithful could have delivered the Eucharistic offerings to pres-byters29 (fig. 4). So, the north aisle and the nave seem to be intended for malefaithful. Anyway, this is a very particular, the only one I noticed, where the sep-aration between nave and aisles is asymmetrical, at least in its first phase30.

Yet, in the Bargala basilica Aleksova and Mango tried to interpret thepresence of an ambo on the south side of the nave with the following explana-tion: “The position of the ambo indicates that the lections and sermons wereaddressed more to the men than to the women.”31 We should also highlight that,as if usual, they are equally attested ambos placed on the north side32. Conse-quently, it seems that the disposition for male and female faithful was quite vari-able and related to local tradition.

We can observe the most impressive use of different pavement levels inthe St. Demetrios church at Thessalonike, where the north aisle lies 0.47 m underthe nave, but settlements like this are widely attested33. In St. Demetrios appar-ently lack barriers between columns but, as asserted by Peschlow the column’s

71

28 Dimitrios PALLAS, “L'édifice cultuel chrétien et la liturgie dans l'Illyricum oriental”,in Actes du Xe Congrès international d'archéologie chrétienne (Città del Vati-cano: 1984), 141. See also: Euthychia Kourkoutidou-Nikolaidou, EuterpiMarki, “Des innovations liturgiques et architecturales dans la basilique duMusée de Philippes,” Jahrbuch für Antike und Christentum Ergänzungsband20 (1995-97), 954.

29 We find similar arrangements, always as circular cavities, on both sides of the Nikopo-lis basilica B and that of Léchainon at Korinth; as bases in Epidaurus.

30 See note 56 and related text.31 Blaga ALEKSOVA and Cyril MANGO, “Bargala: A Preliminary Report,” Dumbar-

ton Oaks Papers 25 (1971): 268. The same authors points out how particularwas also the disposition to west of stairs. Sodini compares this disposition toanother Macedonian example, those of the Rotunda of Thessalonica. JeanPierre SODINI, “L’ambon de la rotonde Saint Georges remarques sur la ty-pologie et le décor,” Bulletin de correspondance hellénique 100 (1976): 497.

32 In Attica in Alimos and Lavreotic Olimpus; in Elis in Olympia and Philiatra; in Cretein Halmyrida and Eleutherna; in Korinthia at Sicyone; in Argolid at Hermione;in Delos (Hagios Kyriakos) and in Caria in the basilica A of Bargylia.

33 We find the same phenomenon in the Lechainon church near Corinth, at Brauron inAttica, in Asia Minor at the Cathedral of Hierapolis and others.

Diego PEIRANO

pedestal “were parts of a low, stone-built wall that gave the impression of a sty-lobate at a height of ca. 0.80 m when seen from the perspective of the aisle 34”.This, along with different floor’s height gave an apparent height of 1.30 m forthe stylobate observed by the north aisle35.

Even without similar variations, the displacement of different floors lev-els between the naves is a quite common feature, obviously emphasizing the ap-pearance of these barriers36.

Nevertheless, St. Demetrios Basilica is not the only church where loftystylobates built up with stone blocks seem replacing the sides’ barriers. Thesedevices are also attested in Elis, in the church built in the workshop of Pheidiasat Olympia (0.85 m); in some Cretan or Lesbian basilicas as Knossos Sanatorio(0.93 m37), Aphentelli (0.70 m), Skala Eressos (0.65 m), Halidanos (0.60 m), Ar-gala (0.60 m), Ypselometopes (0.51 m), Vyzari (0.55 m); in Agios Kyrikos atDelos (0.98 m38); in Kos at Mastichari (0.62 m); in Caria at the basilica D ofKnidos (0.50 m). Other attestations can be also found in Greek area, in Thes-saly within the basilicas C and D of Nea Anchialos (each 0.50 m); in Attica in theErechtheum basilica in Athens (0.50 m); in Laconia in Ayos Petros at Kainepo-lis-Kyparissos (0.56 m); in Kodratos basilica at Corinth (0.50 m). In Asia Minorin the cathedral of Carian Aphrodisia (0.50 m).

These devices, at least the loftiest, had to replace the traditional separa-tions with closure slabs.

Anyway, besides the height reached by lofty stylobate, we have also totake into account the presence of second separation level preventing commu-nication between nave and aisles; these devices were made up wooden latticeworks or closure slabs which left grooves on columns. This kind of arrangement

72

34 PESCHLOW, “Dividing Interior Space,” 60.35 PESCHLOW, “Dividing Interior Space,” 60.36 See for example the Cathedral of Phrygian Hierapolis where from an height of ca

0.80 m of slabs, was added to these the quote of stylobate, reaching the eleva-tion of 1.08 m. This quote became quite impressive from the nave, 0.12-0.15m lower than the south aisle. This arrangement should hinders the view offaithfuls in the aisle from the nave.

37 Rebecca J. SWEETMAN, “Late Antique Knossos. Understanding the City: Evidenceof Mosaics and Religious Architecture,” The Annual of the British School atAthens, 99 (2004), 345.

38 Anastasios ORLANDOS, “Delos Chrétienne,” Bulletin de correspondance hel-lénique 60 (1936): 73-74.

Some Observations about the Form and Settings of the Basilica of Bargalacan be found in Asia Minor in the cathedral of Aphrodisia in Caria39, in the greatchurch in Priene40, probably also in the St. John of Ephesus41 and in the VirginKyriotissa church in Constantinople (now Kalendarhane Camii)42; surely inCrete in the Eleutherna basilica43. While in the first two examples, the whole sys-tem reaches a height of almost 1.60-1.80 m44, in the last one, as highlighted byThemelis45, the transennae arrangement reaching capital’s height. According toPeschlow this type of barriers prevents both physical and visual contact betweenpeople staying in the nave and aisles46.

Consequently some of the basilicas which adopted these devices ap-pear divided quite strongly. To this we must add the different choice of ma-terials as said above: Phrygian Hierapolis cathedral had the nave clad with mar-ble pavements and wall as well, while in the aisle there were brick tiles for thefloor and fresco panels on the walls. Something similar can be found withinthe Agora basilica of Carian Iasos where I worked in the 2010, even thoughthe material used there was less lavish; anyway these examples are quite com-mon47.

73

39 Laura HEBERT, “The Temple-Church at Aphrodisias” (PhD diss., New York Uni-versity 2000), 165-172; quoted in PESCHLOW, “Dividing Interior Space,” 61.

40 Stephan WESTPHALEN, “Die Basilika von Priene. Arkitektur und liturgischeAusstattung,” Istanbuler Mitteilungen, 48 (1998): 313; Peschlow, “Dividing In-terior Space,” 62.

41 PESCHLOW, “Dividing Interior Space,” 62. It is not clear if the plug holes today vis-ible on the columns, above those referable to transennae, belonged to fixedarrangements or to curtains.

42 PESCHLOW, “Dividing Interior Space,” 62.43 Petros THEMELIS, “Eleutherna. The Protobyzantine City”, in Mélanges Jean-Pierre

Sodini, (Paris: Centre de recherche d'histoire et civilisation de Byzance, 2005),347.

44 PESCHLOW, “Dividing Interior Space,” 61 and further references. WEST-PHALEN, “Die Basilika von Priene,” 313.

45 THEMELIS, “Eleutherna,” 347.46 Again, these uses resembles some devices used to conceal to men looks the women

in the gallery. This use is attested in an episode of life of John Chrysostom:Symeon Metaphrastes, “Vita et conversio S. Ioannis Chrysostomi”, in Symeo-nis Logothetae Metaphrasteae opera omnia, vol. 114 of Patrologia Greca, ed.Jacques Paul MIGNE (Paris: 1864), 1113.

47 The database ΒΑΣΙΛΙΚΗ (see note 3) shows how, from the 71 basilicas where are at-tested sides barriers, 15 had surely differentiations in the floors of the naves.

Diego PEIRANO

Peschlow wonders about what kind of liturgy held within specificchurches could necessitate of barriers between the naves48; besides the basil-icas where it was necessary to divide the religious procession from laypeople,the given example - the memorial churches- appears quite persuasive.

Also within bigger churches, faithful community and pilgrims canmove from aisle reaching the relics under the altar or elsewhere49 and then walk-ing out without disturbing worship at all. Some examples of this type of struc-ture can be the St. John at Ephesus and the St. Demetrius at Thessalonike.

Apart from the fact that some memorial churches haven’t any traces ofbarriers50, the articulated paths created within them were not, however, appli-cable in the smaller basilicas. So, we must agree with Peschlow when stating that“neither the type of community that used the church nor the rank of the cele-brant necessarily influenced the division of the building’s internal space51”.

The use of dividers in Macedonian basilicasSide barriers were common features in Macedonian basilicas; we can find

such arrangements in Macedonia Prima at Thessalonica (Acheiropoietos),Philippi (basilicas A and C), Edessa (Longos basilica) and in Thassos island (inthe church of city agora52 and in the north and south Aliki basilicas53) and againin Macedonia Secunda in the Episcopal basilica at Stobi (fig. 5), in the church of

74

Obviously these data must deal with the lost of pavements or of part of these.In addition to the quoted examples had these differentiations the followingbasilicas: in Argolid Epidauros and Hermione; in Attica Brauron; in Caria thechurches of Kaunos (domed basilica) and Knidos (basilica A); in Crete Eleuth-erna; in Elis Olympia; in Lesvos Skala Eressos (Ay. Andreas); in MacedoniaPrima the basilica A of Amphipolis and in Phrygia at Laodicea (basilica behindthe Temple A). To these we must add the second phase of the Bargala basilica.

48 PESCHLOW, “Dividing Interior Space,” 69.49 In the St. Demetrios at Thessalonike the ciborium, the focal point of the cult was in

the mid of nave, toward the north aisle. Charalambos Bakirtzis, “Pilgrimage toThessalonike: The Tomb of St. Demetrios” Dumbarton Oaks Papers 56(2002): 176.

50 See the examples quoted by Peschlow: PESCHLOW, “Dividing Interior Space,” 69.51 PESCHLOW, “Dividing Interior Space,” 69.52 Reallexikon zur Byzantinische Kunst, s.v. “Makedonien”, 1036.53 On these: Jean Pierre SODINI and Kostas KOLOKOTSAS, Aliki II. La basilique

double (Paris: 1984).

Some Observations about the Form and Settings of the Basilica of BargalaBargala and maybe in Kamenica and Konjuh54.

Comparing the two areas we can realise there’s a reduced use of these el-ements in the Macedonia Secunda; but, except for Stobi, probably due to de-creased dimension dimensions of local basilicas compared to those of Thessa-lonike or Philippi.

Peschlow recognizes in these examples, as a common feature, to preventthe view from the aisle into the nave55; he refers mainly to Macedonia Prima, par-ticularly to Thessalonike and Philippi. We can find a similar arrangement in thesecond phase of Museum Basilica of Philippi, where – on the north side – it wasbuilt a second stylobate carrying a templon-like barrier; this latter was probablykept closed with curtains. This particular arrangement, according to Kourk-outidou-Nikolaidou and Marki was temporary and was used – in place of thenarthex – to host cathecumens or penitents56. However, both stylobates andslabs reach 1.50 meters height, so preventing the vision through the aisles. Alsothe Episcopal basilica of Stobi had similar adjunct barriers57, but the pre-exis-tence of high type stylobate (0.77 meters height), of the type that replaced thesame transennae, leaves some doubts about the purpose of this device58.

75

54 On Kamenica: Ivan MIKULČIĆ, “Frühchristlicher Kirchenbaum in der S. R. Make-donien,” in Corsi di cultura sull’arte ravennate e bizantina 33 (Ravenna: 1986),abb. 9. On Konjuh see note 20.

55 PESCHLOW, “Dividing Interior Space,” 61.56 KOURKOUTIDOU-NIKOLAIDOU, Marki, “Des innovations liturgiques,” 954-

957; PESCHLOW, “Dividing Interior Space,” 65. Also the basilica A had ananalogous second stylobate carrying however low type barriers; this unusualfeature was explained by Lemerle with the need of places to sit. Paul LEMER -LE, Philippes et la Macédoine Orientale à l'époque chrétienne et byzantine.Recherches d'histoire et d'archéologie (Paris: De Broccard, 1945), 351-352.Here, however, the north stylobate is the only kept in satisfactory manner.

57 Carolyn SNIVELY, “Transepts in the Ecclesiastical Architecture of Eastern Illyricumand the Episcopal Basilica at Stobi,” in Niš and Byzantium 6, ed. Miša Rakocija(Niš: 2008), 70; Carolyn SNIVELY, “Dacia mediterranea and Macedonia Se-cunda in the Sixth Century: A Question of Influence on Church Architecture,”in Niš and Byzantium 3, ed. Miša Rakocija (Niš: 2005), 219; Carolyn SNIVELY,“Articulation of Space in the Episcopal Basilica: the Colonnades,” in Studiesin the Antiquities of Stobi 3, ed. Blaga Aleksova and James Wiseman, (TitovVeles: 1981) 163-170.

58 PESCHLOW, “Dividing Interior Space,” 65.

Diego PEIRANO

The basilica of Bargala and its liturgical featureBuilt at the turn of 5th and 6th century59, the basilica of Bargala has two

main phases of construction. The partition inside it was made up using transen-nae placed between the two rows of seven columns each one dividing nave fromaisles. Every pair of slabs was connected by a square post embedded on a mas-sive stone support substituting the stylobate. It is not clear if these devices wereintended to allow the passage of clergy or faithful during celebrations, there arealso some visible interruptions corresponding quite always to lacunas in thefloor.

As we have seen, these intercolumnar screens had usually two passagesfrequently placed at both east and west end of each stylobate, in order to permitsome movements and participation of the faithful to the Eucharist. The pres-ence of passages in the east end of basilicas is related to particular kind of bema,that was not coterminous with colonnade, assuming the Π shape; this can beconsidered a feature of basilicas with medium or great dimension. Here the twodoors are situated on the sides of bema chancel, each one corresponding to theopenings in the intercolumnar barriers: local examples can be found in Mace-donia Prima in the basilica A in Amphipolis60, in the double basilica of Aliki61

and the cross-church in Thasos62, but a similar example is also inside the Mace-donia Secunda at Stobi63.

Anyway, the basilica of Bargala had no great dimensions. As reportedthe bema shows two building stages: the first one was less extended to west than

76

59 ALEKSOVA and MANGO, “Bargala preliminary report,” 273, Florin CURTA, Themaking of the slavs: history and archaeology of the Lower Danube Region(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), 135.

60 Alessandro TADDEI, “I monumenti protobizantini dell’acropoli di Amphipolis,”Annuario della Scuola Archeologica Italiana ad Atene, 8 (2008): 273

61 Openings in the north and south sides of the bema are attested each in the two basil-icas, at least in their last phases. Reallexikon zur Byzantinische Kunst, s.v.“Makedonien”, abb. 15-16; on the phases of these enclosures: SODINI andKOLOKOTSAS, Aliki II, 26-34, 151-156.

62 ORLANDOS, Basilike, 527-528.63 At least in the second phase of presbyterium. See: James WISEMAN and Djordje

MANO-ZISSI, “Excavations at Stobi, 1973-1974,” Journal of Field Archae-ology, 3-3, (1976), 291-293.

Some Observations about the Form and Settings of the Basilica of Bargalathe second one and detached from the colonnades64, which, only in a secondtime, became the presbytery barriers65. A small passage retrieved in the last sideof south colonnade can be related to first phase: from there faithful situated inthe south aisle can get Eucharist; nothing similar is visible on the opposite side,which characterizes an access asymmetry between the two places. In the fol-lowing passages I’ll try to debate about this uncommon feature.

In the second phase, in the basilica of Bargala the side barriers of bemacorrespond to intercolumnar ones; at that moment the lateral openings couldbe not useful: as in other medium sized basilicas the communion could be stilldirectly administered through the side devices indeed. The remodelling of syn-thronon was connected to this variation. As reported by excavators, the first stageof this furniture was a flight of stairs leading to a platform, where stayed thebishop; the west wall of this structure was plastered and frescoed imitating theveined marble66. The platform was flanked on both its north and south side bytwo seats. These were removed together with the podium.

It seems quite probable that this second arrangement of synthronon washigher than the first one. The excavators noted how the entrance to bema had awestward projection, and they supposed that was completed by two columnssupporting an arch67. This structure, surely made in order to monumentalize theEntrance of clerics in the bema, would have hidden the bishop place, unless thesynthronon would have been raised up too. These trends can be found also inGreek and Constantinopolitan areas68.

How were these barriers made up? The researchers have found some

77

64 On these changes: ALEKSOVA and MANGO, “Bargala preliminary report,” 269-270. See also: Blaga ALEKSOVA, “The Presbyterium of the Episcopal Basil-ica at Stobi and Episcopal Basilica of Bargala,” in Studies in the Antiquities ofStobi III, Blaga ALEKSOVA and James WISEMAN, eds., (Titov Veles: 1981)29-46. We found the same trend in the Episcopal basilica of Stobi. BlagaALEKSOVA, “The early Christian basilicas at Stobi,” in Corsi di cultura sul-l’arte ravennate e bizantina 33 (Ravenna: 1986), 14.

65 Aleksova and Mango tried to explain these change suggesting that the original shapeof the bema was not conforming to the changing liturgical requirements andwas thus modified. Blaga ALEKSOVA and Cyril MANGO, “Bargala prelimi-nary report,” 270.

66 ALEKSOVA and MANGO, “Bargala preliminary report,” 270.67 ALEKSOVA and MANGO, “Bargala preliminary report,” 269.68 ORLANDOS, Basilike, 526 ff.

Diego PEIRANO

parapet slabs and some stone grilles69; this establishes the problem of the mu-tual arrangement of these kinds of separations. Looking at a wider context, wecan observe how the open works transennae, in the hierarchy typical of thesebuildings, were placed in the bema enclosure70.

If the choice to use barriers between the aisles is quite common, it ap-pears even more particular to set some different floor types among the corri-dors. If the south aisle had the same slabs flooring of the nave, the north onewas paved with a mosaic made up of large tesserae representing some crosses anddifferent geometric shapes.

It seems that the division created by side barriers could have some con-sequence on the decoration: in fact Aleksova and Mango remember how thelower parts of the walls were decorated with frescos simulating marble pan-elling71; while the nave seems characterized by the “accumulation” of marble el-ements as synthronon72, slabs, ambo and pavements of the bema.

Aleksova and Mango stated that the north aisle was reserved to women73,but probably in the last phase74 it was intended – sometimes – for some partic-ular office, maybe baptism. This hypothesis can be strengthened observing theposition of nave (fig. 1), directly connected to the baptistery and the innernarthex. Through the latter, the aisle was then connected to the first of the tworooms that preceded from the west the sacred pool. This room, accessible from

78

69 ALEKSOVA and MANGO, “Bargala preliminary report,” 268.70 Attested in Daphnousia, Olympia, Eleutherna. On these: ORLANDOS, Basilike,

526, fig. 490; Friedrich ALDER and Ernst CURTIUS, Olympia II, (Berlin: A.Asher & co., 1892): 93-105; THEMELIS, Eleutherna, 351. The excavators hada different opinion and put here a figurative parapet slab consisted of three pan-els on basis of more elaborate character respect to those between nave andaisles. ALEKSOVA and MANGO, “Bargala preliminary report,” 271.

71 ALEKSOVA and MANGO, “Bargala preliminary report,” 272.72 ALEKSOVA and MANGO, “Bargala preliminary report,” 270, note 34.73 ALEKSOVA and MANGO, “Bargala preliminary report,” 268.74 According to excavators the Baptistery was constructed shortly after the basilica.

ALEKSOVA and MANGO, “Bargala preliminary report,” 271. At Bargala thesecond phase of the baptistery may be one of the latest features of the Epis-copal complex. Located at the northeast corner of the basilica, it replaced anearlier and smaller baptistery with a font located further to the west. On thissee also: Blaga ALEKSOVA, “Novi istražuvanja na baptisteriumot vo Bargala”,in Zbornik posveten na Boško Babić, (Prilep: 1986), 29-38.

Some Observations about the Form and Settings of the Basilica of Bargalathe outside towards the north facade, seems to have had a distributive role: it waslinked to the narthex on south, to the vestibule of the baptistery on the east sideand to a room for the offerings of congregation to the west wall75. So, the cate-chumens can enter there from outside, leaving their clothes in the vestibule, re-ceiving the exorcisms and then the baptism, so dressing the new garment, andfinally entering the church by the north aisle. To a closer look another detail cansupport this hypothesis: apparently the ambo was taken out of the axis of thechurch but, if we make abstraction of the north aisle, the pulpit results perfectlyin axis.

Out of the baptism liturgy the north aisle was probably for women, assuggested by Aleksova and Mango76, or for other groups of faithful like the cat-echumens; they were asked to leave at the end of the Liturgy of the Word withno disturbance: they can move away right from that way, without mingling withother groups. The same can be done from the galleries, whose existence is at-tested by the discovery of column shafts of two different sizes77. So, the ques-tion were was the place of catechumens is open.

Concerning other liturgical features we could observe how the basilicashares with other Macedonian examples the out-of-axis placement of theambo78; according to Sodini, this characteristic is probably intended right to fa-cilitate the procession entry into bema79. But that’s not the only reason: the men-tioned passage of Aleksova and Mango, for lections and sermons addressedmore to men than women80, finds in this area a lot of references: here the ambos

79

75 On the room and his furniture: ALEKSOVA and MANGO, “Bargala preliminary re-port,” 271; Eugenia CHALKIA, Le mense paleocristiane. Tipologia e funzionidelle mense secondarie nel culto paleocristiano (Roma: Pontificio Istituto diArcheologia Cristiana 1991), 85; Jean-Pierre SODINI, Jean SERVAIS, “Lescarrières de marbre”, in Études Thasiennes IX, Aliki I: les deux sanctuaires,(Paris: 1980), 144.

76 ALEKSOVA and MANGO, “Bargala preliminary report,” 268.77 ALEKSOVA and MANGO, “Bargala preliminary report,” 268.78 Of 16 Macedonian examples found in the database ΒΑΣΙΛΙΚΗ 11 had their posi-

tion determined; of these 9 are out of axis.79 Jean-Pierre SODINI, Les dispositif liturgiques des basiliques paleochretiennes en

Grece et dans les Balkans, in Corsi di Cultura sull’Arte Ravennate e Bizantina31 (Ravenna: 1984), 453

80 ALEKSOVA and MANGO, “Bargala preliminary report,” 268.

Diego PEIRANO

out-of-axis are always on the right side81. The pulpit of Bargala is the only ac-cessible from west side, a feature that has no other references in Macedonia,where, anyway, ambos with a single flight of steps are quite unusual82.

The presence of an inner and an outer narthex is a quite uncommon fea-ture83 that can be explained with the necessity to conceal the sacred mysteriesfrom outside; that’s the same also for the misalignment of the entrances fromouter to inner narthex.

Some provisional conclusionsAs highlighted in this paper, the use of side barriers is widespread in a

large area around the Aegean and his leading Episcopal sees, Thessalonica andCorinth moreover, which occupies a great role in the definition of some liturgi-cal features84. On the other hand, in Constantinople these separations arescarcely attested. As concerning the influences of these and others centres, weshould underline the various distribution of this kind of churches in the differ-ent areas. While, the coexistence of coeval large basilicas adopting or not thesedevices in the same city, signifies that this choice was connected to communityneeds.

These barriers seem to define functional areas where many activitiestook place Their main functions are the separation of clerics and laypeople, andbetween the different kinds of faithful; all these divisions were related to the or-derly development of the rite. Except for this, it is not clear the role of side bar-riers in some examples, especially where these latter were doubled in time. The

80

81 Examples in Filippi (basilicas A, Octagon), Amphipolis (basilicas A and D, Exagon),Thasos (cross shaped basilica and Aliki south), Stobi (Cathedral).

82 The arrangement closer to this one is that of Eleutherna (Crete) where a single stairambo, accessible from west, lie near the stylobate, even though the north one.See THEMELIS, “Eleutherna,” 351. Ambo with a single stair ladder are at-tested in Thessalonica at the basilicas of Acheiropoietos, St. Sophia, St. Mena.Orlandos, Basilike, 545-548.

83 Of the quoted 469 churches inserted in database, 40 had exonarthex; of these 24 arewithout any atrium. These data suggests that for the littler, or lesser monu-mental basilicas, the exonarthex was considered alternative to atrium.

84 Jean-Pierre SODINI, “Note sur deux variantes régionales dans la basilique Grèce etdes Balkans. Le tribèlon et l’emplacement de l’ambon,” Bulletin de correspon-dance hellénique 99 (1975): 581-588, especially 587.

Some Observations about the Form and Settings of the Basilica of Bargalastructure of the basilica of Bargala, and the similar of the Museum basilica ofPhilippi, seem to introduce a time factor in the use of some separations. In thefirst one the same barrier could divide different kind of faithful in ordinary andspecial rite (i.e. Baptism), while in the second new enclosures were probably builtfor temporary necessity and then removed.

For a great amount of the example mentioned above, it seems quite wor-thy to note how the barriers prevented the faithful – or part of them – to clearlylook at celebration rites and the building that hosted them. So, particular sur-faces treatment, i.e. the use of marble and others lavish materials on the naveand their imitation with painted plaster on the aisles were specifically related tothe presence of some categories. At the moment we can say nothing more about,except this last aspect seems crucial in order to understand the perception ofthe basilicas by various actors moving inside it. This, beyond the typological clas-sifications we made extensive use here, can be a development and a purpose forthese researches.

81

Some Observations about the Form and Settings of the Basilica of Bargala 83

Fig. 3: Hierapolis, Bishop's Church (drawing by E. Garberoglio, D. Peirano)

Fig. 2: Agora basilica of Carian Iasos, base and column of north colonnade (photo by author)