ICZM and coastal defence perception by beach users: Lessons from the Mediterranean coastal area

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

4 -

download

0

Transcript of ICZM and coastal defence perception by beach users: Lessons from the Mediterranean coastal area

(This is a sample cover image for this issue. The actual cover is not yet available at this time.)

This article appeared in a journal published by Elsevier. The attachedcopy is furnished to the author for internal non-commercial researchand education use, including for instruction at the authors institution

and sharing with colleagues.

Other uses, including reproduction and distribution, or selling orlicensing copies, or posting to personal, institutional or third party

websites are prohibited.

In most cases authors are permitted to post their version of thearticle (e.g. in Word or Tex form) to their personal website orinstitutional repository. Authors requiring further information

regarding Elsevier’s archiving and manuscript policies areencouraged to visit:

http://www.elsevier.com/copyright

Author's personal copy

ICZM and coastal defence perception by beach users: Lessonsfrom the Mediterranean coastal area

E. Koutrakisa,*, A. Sapounidisa, S. Marzettib, V. Marinc, S. Rousseld, S. Martinof, M. Fabianoc, C. Paolic,H. Rey-Valettee, D. Povhg, C.G. Malvárezh

aNational Agricultural Research Foundation, Fisheries Research Institute (FRI), Nea Peramos, Kavala 64 007, GreecebUniversity of Bologna, Economics Faculty, Department of Economics, Bologna, ItalycUniversity of Genoa, Department for the Study of Territory and its Resources (DIP.TER.IS.), Genoa, ItalydUniversité Montpellier 3 Paul Valéry, LAMETA, Montpellier, FranceeUniversité Montpellier 1, LAMETA, Montpellier, FrancefDepartment of Ecology and Sustainable Economic Development, DECOS, Viterbo, Italyg Priority Action Programme/Regional Activity Center (PAP/RAC), Split, CroatiahArea Geografía Física, Universidad Pablo de Olavide, Sevilla, Spain

a r t i c l e i n f o

Article history:Available online 20 September 2011

a b s t r a c t

Member States of the European Union and the Mediterranean Regional Sea need to elaborate nationalstrategies for coastal management according to ICZM principles and to undertake national stock-taking,which must consider major actors, laws and institutions influencing the management of their nationalcoastal zone. However, different approaches to coastal management and defence and various degrees ofdevelopment and implementation of national ICZM strategies can be found. The research presented inthis article aims to analyze the different situations and to contribute to the further development ofa common approach in terms of methodology to establish stakeholder and users participation in ICZM.An extensive survey was conducted in five pilot sites along the European Mediterranean coastal zone(Greece, Italy and France) show beach visitors’ perception of ICZM, coastal erosion and coastal defencesystems, and beach visitors’ Willingness To Pay (WTP) for beach defence. The survey yielded importantinformation for coastal and beach managers. Surprisingly, the level of awareness about generic CoastalZone Management was found to be rather low in all regions except Riccione Southern beach, Emilia-Romagna Region. In the Languedoc-Roussillon Region, this is justified by the fact that most of therespondents were not local people or beach visitors (other than recreational day-visitors). As regardscoastal erosion it appears significant that, despite the lack of awareness demonstrated overall bystakeholders in the Region of East Macedonia and Thrace, visitors respond very positively to definitionsand show awareness of the erosion process in their coastal system. In conclusion, in order to raise publicawareness about ICZM, erosion and coastal defence systems, it is suggested that education, training andpublic awareness should be promoted as well as identification of local needs for the implementation ofspecific demand-driven studies.

� 2011 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

1.1. Context

Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM) has achieveda significant level of maturity as far as theoretical concepts areconcerned and its role as a key paradigm for the sustainable

development of coastal zones is no longer in question (Billé, 2007).In particular, at European level, ICZM has been widely recognizedand promoted as “the most appropriate process for dealing with long-term challenges”, being a “proactive policy process aimed ataddressing conflicts, interests for coastal space and resources” (EEA,2006). The reference document within the European Union (EU)is the Recommendation 2002/413/EC issued by the EuropeanParliament and the European Council. This document asks EUMember States to elaborate national strategies for coastalmanagement according to ICZM principles and to undertakenational stock-taking, which must consider major actors, laws and

* Corresponding author. Tel.: þ30 25940 29037; fax: þ30 25940 22222.E-mail addresses: [email protected], [email protected] (E. Koutrakis).

Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect

Ocean & Coastal Management

journal homepage: www.elsevier .com/locate/ocecoaman

0964-5691/$ e see front matter � 2011 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.doi:10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2011.09.004

Ocean & Coastal Management 54 (2011) 821e830

Author's personal copy

institutions influencing the management of their national coastalzone (Pickaver et al., 2004). Nonetheless, varying interpretations ofthe ICZM concept and different understanding of the Recommen-dation has emerged across Europe (EC, 2007; Deboudt et al., 2008).

Along the European Mediterranean coasts, different approachesto coastal management and various degrees of development andimplementation of ICZM national strategies can be found. Today,several coastal areas have been (or soon will be) affected by ICZMprojects, which however have often been carried out at a local leveland with a narrow scope. The Mediterranean area plays a pivotalrole within the definition of regional strategies for ICZM and theneed for a system ensuring a coordinated approach at regional(basin) level has become evident. Over the last few years, the issuehas been addressed within the framework of the MediterraneanAction Plan (MAP), a UNEP Regional Seas Program which consti-tutes the cooperative effort of 21 Mediterranean countries, and theEuropean Commission for the achievement of the objectives of theBarcelona Convention, themajor legal framework for the protectionof the Mediterranean environment (www.unepmap.org). Inparticular, in 2001 the Contracting Parties of the Conventionprepared “a feasibility study of a regional legal instrument onsustainable coastal area management” (PAR/PAC, 2002). This processled to the drawing up of the ICZM Protocol for the Mediterranean,adopted in 2008 after a lengthy consultation process carried outwith the support of PAP/RAC (Priority Actions Programme/RegionalActivity Centre) and which constitutes the seventh Protocol, thuscompleting the set of legal instruments of the Convention (UNEP/MAP/PAP, 2008). The Protocol reflects the regional sea-basedapproach envisaged by the EU and includes the basic principlesand objectives of the EU ICZM Recommendation, considering thesupport for the sustainable development of Mediterranean coastalzones as its main objective.

Public participation and stakeholders’ involvement are crucial inestablishing sound sustainable development practices. The centralrole of participation in ICZM has been widely recognized in litera-ture, since it allows a more equitable and transparent process,reduces conflicts and makes final decisions more effective andlegitimate (Edwards et al., 1997; Cicin-Sain and Knecht, 1998;Johnson and Dagg, 2003; Buanes et al., 2005; Peterlin et al., 2005;Stead, 2005; Chaniotis and Stead, 2007). Furthermore, participationhas been definitively sanctioned as a key principle of ICZM by theEU Recommendation, which states that “Appropriate governanceallowing adequate and timely participation in a transparent decision-making process by local populations and stakeholders in civil societyconcerned with coastal zones shall be ensured”, as well as by theMediterranean Protocol, which dedicates Article 14 to the issue.“Participation is not only a democratic right, but also an importantcondition for success in instrumental terms” (Jentoft, 2000).However, to ensure active public participation it is necessary tounderstand people’s perception of specific issues and to be aware oftheir knowledge, feeling and behaviour (Stead, 2005; Tran et al.,2002; Tran, 2006). In fact, consensus and acceptability regardingcoastal governance depends on local needs and thus, in order toensure effective strategy implementation, community participationapproaches should be tailored to local characteristics (Edwardset al., 1997; Chaniotis and Stead, 2007).

Beach visitors’ analysis is an important component in definingbeach management policies and in establishing administrativepriorities (Dahm, 2003; Santos et al., 2005). Numerous examples ofthe analysis of beach visitors’ perception can be found in theliterature and this kind of study has increased over the last decades,to fulfil the need to better understand their behaviours and pref-erences and their views on different beach-related aspects, such asenvironmental and water quality, marine litter, and other issuessuch as the awarding of the Blue Flag (Nelson et al., 2000a,b;

Pendleton et al., 2001; Blakemore et al., 2002; Macleod et al.,2002; Pereira et al., 2003; Shivlani et al., 2003; Turbow et al.,2004; Santos et al., 2005). Results from these studies have some-times been considered for assessing beach quality or rating bea-ches, and beach user opinions and preferences have beenconsidered in beach management frameworks (Micallef andWilliams, 2004; Villares et al., 2006; Gore, 2007; Cervantes andEspejel, 2008; Roca and Villares, 2008; Marin et al., 2009; Phillipsand House, 2009). However, beach visitors’ perception of coastalerosion has rarely been studied and has evenmore rarely been usedas a contribution to management (Breton et al., 1996; Dahm, 2003;Marzetti, 2007; Marzetti et al., 2009). In this context, a socio-economic approach to beach management involves an end-usersconsultation, also including the assessment of WTP for beachdefence projects by applying the Contingent Valuation Method(CVM) (Mitchell and Carson,1998). This technique has been appliedin several case studies in order to estimate the variation in recre-ational value of the beaches under several hypothetical alternativescenarios regarding different coastal defences (McConnell, 1977;Bell, 1986; Silberman and Klock, 1988; King, 1995; Whitemarshet al., 1999; Polomé et al., 2005; Marzetti, 2007, 2009) and wasalso applied in the beach visitors’ surveys conducted for thisresearch.

One of the key objectives in order to analyze and assess the stateof the art in local authorities administrative and managementorganisation as well as the level of public information/participationregarding ICZM process implementation (in particular focussing oncoastal erosion management) can be achieved through fieldsurveys. Two were carried out in the context of the research con-ducted for this article: one aimed at coastal zone practitioners andstakeholders to analyze the way ICZM processes are currentlydesigned locally (Koutrakis et al., 2010) and the other aimed atbeach visitors (residents, day-visitors and tourists), with regard totheir perception of beach erosion, coastal defence policies, ICZM aswell as beach value. Results from the beach visitors’ survey are thefocus of this paper.

The wider context and aim of this paper are to present anddiscuss the results of the surveys conducted in five pilot sites alongthe EuropeanMediterranean coastal zone (Greece, Italy and France)in order to evaluate beach visitors’ perception of ICZM, coastalerosion and coastal defence systems. After a brief description of themain characteristics of the study areas, the methodology used isdescribed and the results from the common questionnaire aboutICZM and coastal erosion perception are presented. Finally,proposals to overcome the problems are suggested.

1.2. The study areas

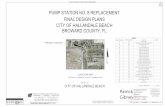

Five pilot sites were selected in three countries, each site withdifferent characteristics (Greece: Nestos Delta coastal zone; Italy:Riccione on the coast of the Emilia-Romagna Region, Tarquiniabeach in the Lazio Region, Riviera del Beigua in the Liguria Region,France: Languedoc-Roussillon Region) (Fig. 1).

1.2.1. Greece1.2.1.1. East Macedonia & Thrace Region: Nestos Delta coastalzone. The Delta of the River Nestos is situated on the east side of theKavala Gulf, which is subject to beach erosion. The whole NorthAegean coastal zone is affected by southeast, south, southwest andwest winds and the corresponding sea waves and currents(Xeidakis et al., 2006). Both the natural environment and humanactivities have already been affected by erosion on the eastern sideof the Kavala Gulf. This phenomenon is more intense in the sandyislands separating the lagoons from the sea, causing a decrease in

E. Koutrakis et al. / Ocean & Coastal Management 54 (2011) 821e830822

Author's personal copy

the width over the last 30 years, as well as in areas near the estuaryof the River Nestos.

The Nestos Delta, with an extent of 2226 km2, is a “Wetland ofInternational Importance”, according to the Ramsar Convention,a Natura 2000 area, and constitutes part of the National Park ofEastern Macedonia and Thrace that also includes lakes Vistonidaand Ismarida (Pavlikakis and Tsihrintzis, 2006). Residents are about22,000. Over 60% of the local population is employed in agricultureand tourist activities are underdeveloped (Pavlikakis andTsihrintzis, 2003). Regarding management actors, apart from thecurrent regulatory framework (a management body was firstinstituted in 1999 for the National Park), non-governmental orga-nizations have been intensely involved in the park management,also implementing environmental education projects(Dimitrakopoulos et al., 2010). There are eleven organised beachesin the area, managed by private stakeholders. Access to all thebeaches is free. No coastal erosion defence project has been con-structed in the area and it is the first time that such a perceptionapproach has been conducted.

1.2.2. Italy1.2.2.1. Emilia-Romagna Region: Riccione and Misano Adriaticobeaches. Riccione and Misano Adriatico are well-developed touristresorts in the Emilia-Romagna Region, near Rimini, on the North-West Adriatic Sea. Residents are about 34,800 in Riccione, and10,000 in Misano Adriatico. The Riccione and Misano Adriaticobeaches are of light fine sand. From the recreational point of view,this coastal area has the usual traits of beaches in the Emilia-Romagna region, where sunbathing facilities are available on thebeach. Those who visit this beach area for ‘sun and sea’ activities

mainly rent sun umbrellas and loungers, and use bar services.Tourists mainly stay in hotels. They stay on average 6 days mainly inspring/summer. Most of the foreigners come fromGermany, France,Switzerland and former USSR countries. According to the dataprovided by the Emilia-Romagna Region (Osservatorio turisticoregionale), tourist arrivals were on average about 720,000 per yearin Riccione and Misano Adriatico between 1999 and 2006. Day-visitors are not officially recorded, but they are numerous, partic-ularly during the week-end. They come from nearby denselypopulated areas, and a result of the Riccione/Misano Adriaticosurvey is that about 24% of beach visitors are day-visitors. There-fore, according to these data, also considering residents (about44,800), we estimate that about 1 million of people may visit thesesites per year. Both the Riccione and Misano Adriatico beaches areunder erosion and are already artificially defended through hardstructures and nourishment. Nevertheless, re-nourishment isneeded to maintain this sandy beach area and is implementedevery 5 years in quantity and quality such as to restore the beach.The cost of this re-nourishment project is about 3,500,000 V.

1.2.2.2. Lazio Region: Tarquinia beach. The pilot site chosen in theLazio Region for testing beach users’ perception on coastal anderosion management is the beach of Tarquinia Lido, on the Tyr-rhenian coast 90 km north of Rome. Tarquinia Lido is part of theMunicipality of Tarquinia situated 5 km inland, famous for itsEtruscan archaeological tombs. The Municipality of Tarquinia has15,162 inhabitants (Istat, 2001) and extends over 279 km2. Thepopulation density is very low, just 54 inhabitants/km, lower thanthe figure recorded for the whole province (75 inhabitants/km)(Provincia di Viterbo, 2006). The economy is mainly based on the

Fig. 1. Map presenting the 5 pilot sites that were selected in the 3 Mediterranean countries. (1) Greece: Nestos Delta coastal zone in the East Macedonia and Thrace Region (N40.957447�; E 24.526208�), (2) Italy: Riccione and Misano Adriatico on the coast of the Emilia-Romagna Region (N 43.991522�; E 12.678621�), (3) Italy: Tarquinia beach in LazioRegion (N 42.223019; E 11.703615�), (4) Italy: Riviera del Beigua in Liguria Region (N 44.371300�; E 8.622395�) and (5) France: Languedoc-Roussillon Region (N 43.429861�; E3.769758�).

E. Koutrakis et al. / Ocean & Coastal Management 54 (2011) 821e830 823

Author's personal copy

services sector (66%), even though the proportion of farmers is stillhigh (15%) compared to other areas of the Lazio Region. In partic-ular, tourism is not very developed. Statistics shows that, though inthe mid-1990s, arrivals and night stays in hotels were 17,000 and39,000 respectively, these figures fell to 5720 and 19,463 in 2004,respectively (APT, 2004).

Tarquinia Lido has a wide fine sandy beach extending fora length of 2 km. The sand is black due to the presence of volcanicelements. The area is subject to high erosion that determines thelinear realignment of the beach, with average erosion (common tothe whole northern shore) of 1e2 m per year. As a consequence theLazio Region has implemented several programs of defence(Dipartimento Territorio Regione Lazio, 2006). During the 1990sthree interventions were implemented (1990, 1996, 1999), con-sisting of beach nourishment and groynes. A total of 138,000 m3 ofsand was used to fill in the shore. However the high persistenterosion caused the beach almost to disappear in 2002. Thereforefurther intervention was required in 2004. The volume of the sandfor the re-nourishment project was 485,000 m3, for a total cost ofV 5,900,000.

1.2.2.3. Liguria Region: Riviera del Beigua. The third pilot area inItaly is a coastal district made up of 6 small-mediumMunicipalities,situated between the cities of Genoa and Savona in the LiguriaRegionandnamedRivieradel Beigua (RdB). The23kmof coastlineofthe RdB is typical of the Liguria Region: a narrow strip of landcharacterized by rocky coasts alternating with sandy and sandy-gravel beaches and cobble pocket beaches and subjected to heavyhuman pressure, mainly urbanization and tourism activities. Themarine and coastal environment is considered of medium-lownatural value in the whole area, due to the poor degree of naturalconservation of marine habitats and to the high degree of humanalterations, with the exclusion of a small area of well-preservedrocky coastline and two marine Sites of Community Importancedue to the presence ofmeadows of Posidonia oceanica. The sea of theRdB is also protected as the Cetacean Sanctuary of the Mediterra-neanSea. Theenvironmental qualityof theRdBhasbeenparticularlyaffected by two important episodes: i) the extensive and chronicpollution by heavy metals from a chemical industrial plant, nowclosed and subjected to a reclamation plan, and ii) the accidental oilspills of 1991, one of theworst to occur in theMediterranean, causedby the sinking of the tanker “Haven”, whose definitive reclamationended recently. The RdB is a well-known resort and recreationalbeach tourism plays a key role in the local economy. The tourist flowin thearea is high (more thanonemillion tourists/year)witha strongseasonality showing apeak in JulyandAugust. Local bathing tourismis mostly domestic and family-oriented, composed by tourists fromthe neighbouring regions. High tourist presence during the peakseason often causes tension due to the additional pressure on localresources (water, sewage treatment plants, etc.) and facilities(parking, traffic, etc). In the RdB, over the last few years, localauthorities have undertaken several initiatives to pursue an inte-grated and sustainable management of the whole area, aimingtowards a new territorial development.

1.2.3. France1.2.3.1. Languedoc-Roussillon Region: Hérault district (Valras-Plage,Sète and Villeneuve-lès-Maguelone to Palavas-les-Flots beaches). Thecoastal zone of the Languedoc Roussillon Region is located on thewestern part of the French Mediterranean area and encompassesfour administrative districts (“Département”). It extends about230 km from the Rhône Delta (east) to the Spanish border (west).Beaches are mainly sandy (160 km) with wide dunes. These dunesare considered “Wetlands of International Importance” accordingto the Ramsar Convention, regarding several endangered species

(flora and fauna). Its 70 beaches can be divided into natural beaches(51%) urban beaches (33%) and half urban/half natural (16%).

The construction of harbours and dikes in the 1960s and 1970shas reduced sediment supply from the Rhône River and increasedcoastal erosion. Between 1945 and 1996, there has been a net loss of260 ha (ACT Ouest and SCE Montpellier, 2006). As a consequence,a regional strategic management scheme was designed in 2003 tocope with coastal erosion through the combination of hard struc-tures and soft systems and promote proactive coastal policymanagement.

The pilot sites are located in the Hérault district and are Valras-Plage, the lido from Sète to Marseillan, the lido of Villeneuve-lès-Maguelone and Palavas-les-Flots. These pilot sites were selected inorder to cover a range of natural and urban beaches and areincluded in the regional strategic management scheme set up in2003. Two of these sites have river outlets: the Orb River on Valras-Plage beach and the Lez River in Palavas-les-Flots. The local pop-ulation is 4360 inhabitants in Valras-Plage, 43,665 inhabitants inSète and 6046 inhabitants in Palavas-les-Flots. These figures morethan double in summer since recreational beach tourism is veryattractive, and nearby towns provide flows of day-visitors. The localeconomy is mainly based on the services sector, which generatesbetween 80% and 90% of its gross domestic product. Furthermore,local and regional authorities have been carrying out ICZM initia-tives for several years.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Questionnaires and interviews

A survey by questionnaire was carried out with the samemethodology in all the pilot areas. This investigation was aimed atbeach visitors, including residents, day-visitors and tourists, aged18 plus. It was implemented through face-to-face interviews, ofapproximately 15 min. At the beginning of the interview a briefintroduction was given to introduce the context of the overallresearch project, including its international nature and itspurposes, emphasizing the role of ICZM and of coastal defence fromerosion. In these areas a total of 1462 questionnaires werecompleted during July/August 2007. The questionnaire consists oftwo parts. The first part consists of questions on ICZM, coastalerosion and coastal defence perception, common to all five casestudies. The second part consists of questions about visitors’ WTPfor beach defence. As regards this part, questions differed only forthe Emilia-Romagna Region since it was the only region interestedin estimating the WTP for beach non-use values; while the otherregions were interested in beach use value alone. More analyticallythe two parts include:

a) First part: Beach users’ perception about ICZM, coastal erosionand coastal defence. This part is first of all composed of ques-tions about interviewees’ profile, such as gender, age, level ofeducation and profession. Secondly, there are questions, whichaim to identify the degree of awareness about ICZM, coastalerosion and finally coastal defence perception. This part isjustified by the fact that end-users’ perception about thesetopics plays a pivotal role for the definition of beach manage-ment policies (Dahm, 2003).

b) Second part: WTP for beach defence from erosion. TheContingent Valuation Method (CVM) is the most appliedmethod for estimating that part of the beach value which is notestablished by the market. Through a questionnaire thismethod creates a hypothetical market, which permits respon-dents to express a monetary value for a beach change (Arrowet al., 1993). The elicitation question can be phrased as WTP

E. Koutrakis et al. / Ocean & Coastal Management 54 (2011) 821e830824

Author's personal copy

for a benefit or for avoiding a loss, or Willingness To Accept(WTA) for suffering a loss or for renouncing a benefit. Experi-ence shows that respondents tend to elicit higher WTA valuesthan WTP values for the same public good. Nevertheless,respondents seem to find it difficult to elicit a WTA valuebecause they do not find it plausible. CVM in theWTP version isthemost suitable method for estimating beach values (Mitchelland Carson, 1998). It needs the specification of a paymentvehicle, such as entrance fee, new tax and donation. During theresearch, in the Region of East Macedonia and Thrace, the LazioRegion, the Liguria Region and the Languedoc-RoussillonRegion the direct use value (such as sunbathing and swim-ming) of a beach defended from erosionwas evaluated, and thepayment vehicle used is a daily entrance fee. The Emilia-Romagna Region, instead, was interested in estimating theindirect use value (storm protection and flood control) andnon-use values, such as option value (having the option to visitthe beach in the future), bequest value (preservation for futuregenerations) and existence value (a person may be willing topay only for knowing that the beach exists), about a beachdefence project. These values are benefits different to theenjoyment from direct beach use, and for these, visitors may bewilling to pay a further amount other than the amount spentfor direct beach use. A donation every five years is the paymentvehicle. Even if a voluntary contribution should be used withcaution, the Emilia-Romagna Region established that it wouldhave been the chosen payment vehicle if visitors had actuallybeen asked to contribute.

3. Results

3.1. (a) Perception of ICZM, coastal erosion and coastal defencepractices and (b) Willingness To Pay (WTP) and ContingentValuation Method (CVM)

The main results regarding the beach visitors’ perception ofICZM, coastal erosion and coastal defence practices in the five casestudies are shown Table 1. The main results regarding the estimateof the WTP for beach defence in the five case studies are shown inTable 2.

In the East Macedonia & Thrace Region it can be assumed thatvisitors were well aware of the aspects of the coastal zone itself buton the other hand there is a lack of knowledge about the aspects ofICZM (Table 1). The majority of the visitors said that they wereunsatisfied with the way that the regional and local authoritiesmanage the coast. Regarding knowledge of coastal erosion, morethan half of the interviewees believed that coastal erosion is “Lossof sand/land from coasts” and “Coastal ecosystem degradation”.However, they were not aware of any coastal erosion problem intheir area, despite being familiar with possible erosion problems.Regarding coastal defence perception, the majority of the inter-viewees knew none of the suggested defence systems. The majorityof the interviewees preferred the soft system and compositeinterventions, as the best ways to protect the coastal zone fromerosion, instead of the hard structures. In particular with regard tothe hard structures and less to the soft systems, they believed thatpollution and alteration of the landscape and the impact on animals

Table 1Common questions about ICZM and coastal erosion perception: results in percentages, according to the different pilot sites.

Question Greece e NestosDelta coastalzone

Italy e

RiccioneBeach

Italy e

Tarquiniabeach

Italy e Rivieradel Beigua

France e

Languedoc-Roussillon

201 606 84 270 301

1. Do you know what ICZM is? Yes 21.9 98.7 20.0 21.1 6.0No 78.1 0.0 80.0 78.9 94.0No Answer 0.0 1.3 0.0 0.0 0.0

2. Are you satisfied with the way theregional and local authorities manage the coast?

Yes 33.3 71.3 7.0 43.7No 66.2 25.9 93.0 50.4No Answer 0.5 2.8 0.0 5.9

3. Do you know what "coastal erosion" is? Loss of Sand/Land from Coasts 24.4 42.7 40.0 46.7 37.8Coastal Ecosystem Degradation 7.5 23.1 7.0 11.1 10.4Both 67.7 28.1 53.0 41.1 50.3No Answer 0.5 5.9 0.0 1.1 1.5

4. Have you ever noticed any problemlinked to coastal erosion problem in this area?

Yes 44.3 70.0 87.0 43.3 70.2No 55.2 30.0 13.0 51.9 13.9No Answer 0.5 0.0 0.0 4.8 15.9

5. Which of the following coastaldefence system do you prefer?

Parallel hardstructures emerged

11.0 20.0 33.0 9.2 16.2

Parallel hardstructures submerged

22.9 25.9 33.0 12.4 16.2

Soft systems 30.4 17.7 20.0 23.3 22.2Perpendicular hardstructures emerged

11.0 7.6 0.0 24.7 16.2

Composite interventions 21.4 6.9 7.0 10.6 22.2Other 1.0 0.0 0.0 2.8 6.7None 14.4 22.0 6.7 6.7 0.3

6. Why do you prefer it? Aesthetic reason 56.7 47.7 22.6 12.3Best way to defend the beach 63.2 40.3 23.9 35.8The quality of thewater is better

33.3 20.6 7.2 3.6

Safer for swimmers 48.8 25.8 6.0 2.3More suitable for boats 29.4 13.7 0.0 1.7Lower environmental impact 56.7 16.8 17.3 32.1Other 5.0 0.0 7.9 0.7None 5.0 0.0 15.1 11.5

7. Coastal defence systems may costs morethan 1,000,000 V/km Do you thinkthis cost is justified?

Yes 36.3 72.6 80.0 54.8 96.7No 63.7 25.7 20.0 33.7 1.3No Answer 0.0 1.7 0.0 11.5 2.0

E. Koutrakis et al. / Ocean & Coastal Management 54 (2011) 821e830 825

Author's personal copy

and plants are their main drawbacks. The majority of the inter-viewees believed that protection of the coastal zone is of highimportance or a priority.

As regards voluntary financial contribution (WTP) of the visitorsfor the protection of the coast from erosion, 91% of the respondentsbelieve that the protection of coastal areas is a very important ora priority issue (Table 1). Themajority of visitors (39%) arewilling topayV 0.5e1.5, and 24% of visitors are unwilling to pay. As shown inTable 2, the mean WTP is V 1.49 when visitors unwilling to pay areconsidered as zero values; while it isV 1.99 when visitors unwillingto pay are excluded from the mean computation. A certain numberof respondents suggested that only tourists should pay for theprotection of the beach.

The results in the Emilia-Romagna Region show that 18% ofrespondents gave a correct answer about what a coastal zone is,while the rest a partially correct definition. As regards the ICZM,26.1% of respondents gave a correct definition, while 70.6%a partially correct definition. The great majority of respondents aresatisfied with the coastal management of the area. Concerningcoastal erosion, 28.1% of interviewees gave a correct definition, andthe rest a partially correct definition (Table 1). The great majority ofthem are aware of erosion problems, and believe that they aremainly the loss of a natural environment (48%), and the loss of sand(39.8%). The main erosion problems are loss of sand and deterio-ration of the coastal ecosystem, while 30% did not notice anyproblem. The majority of respondents are familiar with defencestructures (Marzetti, 2007). The most preferred structure isparallel-submerged breakwaters; the second preferred is emergedbreakwaters and the third preferred is nourishment. Main motivesof preference are: aesthetic impact, more suitable for beacherosion, and safer for bathers. As regards the drawbacks about hardstructures (such as emerged and submerged breakwaters, groynesand composite intervention) respondents mainly highlightedpollution, aesthetics/landscape, and high cost; while as regards softstructures (such as nourishment), quality of sand, pollution, andhigh cost. 72.6% of respondents believe that the cost for defendingthe beach from erosion is justified.

The vast majority (87.3%) of respondents are in favour of thedefence project, but the majority (54.8%) of them are unwilling todonate to a non-profit agency for the implementation of thisdefence project every 5 years. Amongst respondents willing todonate (45.2%), only 34.3% of them state how much. 54.6% of visi-tors are unwilling to donate, and 2% did not answer. Respondentswho are willing to donate give values from V 1 to V 9, and thosewho are unwilling to donate are considered as zero values. Asregards the whole sample (zero included, and ‘no answers’excluded) the mean WTP, is V 1.1 (median V 0); while for the sub-sample of those who are willing to donate (zero values excluded), itis V 2.86 (Table 2). The payment will be made every 5 years whenthe project is implemented. These respondents are 89% certain topay if actually asked. Main motives of donation are option value(33% of respondents), indirect use value (28%), bequest value(24.4%), and existence value (4.4%). A certain number of

respondents (27.7%) are willing to donate for indirect use value. Asregards the means of payment, 31.4% prefer to pay at a post office,25.6% by text message, 12% to the non-profit agency, 15.7% by banktransfer and credit card, and 3.3% on the beach. Amongst non-donation motives 34.74% of respondents unwilling to donateanswer that the State should pay for beach defence and 22.36% thatthey already pay enough taxes.

In the Lazio Region just 20% said they had a basic idea of what anICZM is, or should be, but none gave a definition. This result showsthat this topic is too recent for coastal users frequenting the beachof Tarquinia (and maybe other beaches of the Region), even thoughthe regional ICZM Commission has set up seminar and discursiveplatforms, such as fora. It appears that the success of awarenessrising during a tentative project carried out by the regionaladministration to implement an ICZM strategy in the past in thesethree pilot areas of the Lazio Region was limited. As regards theperception of what the coastal zone is, just 33% considered it to bean area including both beach and sea. Therefore it seems thatpeople have a limited perception of what a coastal zone is. Nearlythe whole sample (93%) considered the way of managing the beachto be unsatisfactory, but none provided explanation about prob-lems and solutions to better improve management. As regardserosion and its perception, the survey shows that people are wellaware of what erosion is (more than half of the sample considerserosion to be the loss of land and degradation of habitats), eventhough the majority (87%) has not noticed any consequences linkedto erosion. Moreover none gave a convincing explanation for theconsequences of planning and management of the local coastalarea. It seems also that hard structures, especially emerged andsubmerged breakwaters (66%), are considered to perform better interms of sand retention and environmental impact. Although Tar-quinia beach was subject to several successful and durable nour-ishments over the last few years, just 20% of users said theyappreciated this solution because of some changes in the quality ofthe new beach (too fine with respect to the sand before theerosion). Moreover, even if the majority of the sample (80%)perceives a limited quality of the beach and the foreshore after thenourishment in terms of environmental concerns, they claim thathard structures should be more impacting on sea quality, inparticular for water stagnation. This idea may be justified consid-ering that that beach nourishment is the only coastal defence thatbeach users at Tarquinia Lido have experienced.

The subject of this survey is the justification of the high costsustained by the Region for coastal defence. To the general questionwhether it is justifiable to spend more than 1 million euro(remembering that the Tarquinia beach nourishment cost wasmore than 2 million euro per km in 2004), 80% of the samplereplied in a positive way. The recognized importance of the defencefor beach users is then assessed also in terms of maximumWTP perday to contribute to the financing of nourishment of the beach byan additional charge to the sunbathing establishments fee.Considering that 43% of the people are unwilling to pay, i.e. pro-tested (WTP¼ 0 for 36 persons), the meanWTP isV 0.50, while the

Table 2Mean Willingness To Pay (WTP) in the five Mediterranean sites under study. (Survey time: July/August 2007).

Country Greece Italy Italy Italy France

Region East Macedonia & Thracea Emilia Romagnab Lazioa Liguriaa Languedoc-Roussillona

Site Nestos Delta Riccione/Misano beach Tarquinia beach Riviera del Beigua Hérault District

Number of valid interviews 200 539 84 215 273Mean WTP (zero values included) V 1.49 V 1.1 V 0.50 V 1.36 V 0.77Mean WTP (zero value excluded) V 1.99 V 2.86 V 0.96 V 2.85 V 3.94

a Use value.b Non-use value.

E. Koutrakis et al. / Ocean & Coastal Management 54 (2011) 821e830826

Author's personal copy

median is much lower,V 0.10. Excluding zero values, the maximumdaily mean WTP is V 0.96, while the median is V 0.56. The highnumber of zero values seems to suggest that beach defence shouldbe guaranteed by public funding and no private intervention shouldbe required in terms of beach charges to sustain the nourishmentproject, or that interviewees behave as free riders. However asregards the payment vehicle, among those declaring a positiveWTP, the preferred payment method is a higher entry fee to thesunbathing establishment (24%), followed by a tax increase forcommercial activities (18%) and for house owners (18%).

Coastal zone perception in the Liguria Region, 48% of respon-dents picked the correct answer from four suggested definitions,while 42% selected a partially correct one, showing unsatisfactoryawareness of this topic. Concerning ICZM perception, respondentsshowed scarce knowledge and low awareness. 79% of intervieweesdo not know what ICZM is and even among those who claimed tohave heard of ICZM or know what ICZM deals with, only 58%answered correctly. However, half of the interviewees said theywere partially or totally satisfied with Ligurian authorities’ coastalzone management. As regards coastal erosion perception, beachusers showed a good level of awareness: 47% defined coastalerosion loss of sand or of land; 11% coastal ecosystem degradation;and 41% both (i.e. loss of land and coastal ecosystem degradation).About half of respondents (49%) identified the loss of naturalenvironments as the most important problem related to coastalerosion. However, more than half (52%) did not notice any problemrelated to coastal erosion, even if the area periodically experiencederosion problems and numerous hard defence systems (i.e.,groynes) are spread along the beaches. Of those who stated thatthey noticed problems, a great part (44%) claimed they found thebeach to be narrower than in the past. Concerning coastal defencesystems, overall perpendicular hard emerged systems and softsystems are the most well-known (29% and 24% respectively) andpreferred (respectively 25% and 23%). Efficacy (24%) and aestheticfeatures (23%) of selected coastal defence systems are the mainreasons behind users’ choices, together with low environmentalimpact (17%).

The majority (55%) of respondents considered the costs thatauthorities have to face for coastal defence systems to be justified,while the percentage of those stating the contrary is not negligible(34%). However, the vast majority of interviewees defined beachprotection as an important issue (75%) or even a priority (23%). Themean WTP for respondents who are willing to pay a daily fee toprotect and save beaches from coastal erosion is V 2.85 and 44%would offer a fee lower thanV 5. Nonetheless, a significant numberof respondent declared they were unwilling to pay (41%), thereforethe mean WTP is V 1.36 when zero values are considered. 37% ofrespondents think that everyone must deal with coastal protectionissue, and beach protection should be paid with public funds.Nonetheless the majority (60%) thinks that only beach users shouldpay for coastal protection, and funds should be half public and halfprivate. None of these respondents state that residents should pay,while 50% of them think that tourist and sunbathing establishmentmanagers should pay, and 26% state that all users of coastal zonesshould pay for their protection.

In the sites in France, most people do not know what ICZM is(94% of people answer “No” to the question “Do you know whatICZM is?”). However, in general people are aware of most sustain-able development public policies (water, waste, energy, etc.)through media broadcasts. As a consequence, ICZM misperceptionis associated with a lack of or misguiding government communi-cation. Beach visitors define coastal erosion either as “a loss in sandand coastal land” (37.8% of respondents), or a “coastal ecosystemdegradation” (10.4% of respondents), or both of these processes(50.3% of the respondents). Results on perception show that

people’s perceptionwith regard to coastal erosion depends on howlong they have been living on the coastal zone as well as their age.Tourists seem less concerned by coastal erosion and beach loss.Moreover it seems that people are not sufficiently informed aboutcoastal risks and defence schemes. Coastal erosion is primarilyperceived by its consequences on beach surfaces; driving forces arenot identified. Regarding the set of hard structures and softmethods, beach visitors do not rank them clearly. As shown inTable 1, Question 5, 16.2% of respondents prefer emerged parallelhard structures, 16.2% prefer submerged structures and 16.2%perpendicular emerged; while 22.2% prefer soft methods. Hardstructures and soft methods are complementary and alsocontribute to sustainable development practices when they arecombined; 22.2% of people therefore prefer beach realignmentmethods in terms of “composite interventions”. 98.3% of respon-dents believe that the protection of coastal areas is a very importantor a priority issue (Table 1, Question 8). As regards the cost ofdefence systems (question 7: “Coastal defence systems may costmore than 1,000,000 V/km. Do you think this cost is justified?”),96.7% of beach visitors agree that this cost is justified; while 82.7%think that “protection towards coastal erosion is a priority”.

As regards the WTP question, there were 273 valid interviews(Table 2). The meanWTP for respondents who are willing to pay forthe coastal erosion protection project is V 3.94. Regarding thewhole sample (where people unwilling to pay are considered aszero values), the mean WTP is about V 0.77. 39.5% of respondentsprefer a local tax as payment vehicle; while a direct payment on thebeach to a non-profit agency is preferred by only 17.5% of respon-dents. As integration of the previous results, wemay add that 73.9%of people think that “Funds for beach protection are currentlypublic and should remain public” whilst 22.6% of people considerthat “Funds should be half public, half private (beach users)” (seeTable 1).

4. Discussion

Surveying preferences and opinions of beach visitors is anexercise that could yield important information for coastal andbeach managers (Dahm, 2003). However, it is very important thatwe are cautious in interpreting the results of such surveys sincethey are greatly conditioned by variables such as: time of the year(Cervantes and Espejel, 2008); proximity of city or metropolitanarea; main characteristics of the enclave (resort or other); and thefact that the use of coastal areas should not only be identified withbeach recreational use. In the survey it appears that beach visitorsare mostly holiday makers, although sites such as Nestos Delta(Greece)may be also visited by local people and other visitors for itsnatural environment. Beach visitors generally have an under-standing of management which is naturally biased towards tourismand the need of further facilities for a better use of the beach.Nevertheless, this is not always a good recommendation formanagers since visitors coming by road, for example, mightdemand a shorter and faster route, while a motorway througha National Park is not always the best option.

Surprisingly, the level of awareness about generic Coastal ZoneManagement was found to be rather low in all regions exceptEmilia-Romagna Region. In the Languedoc-Roussillon Region, thisis justified by the fact that most of the respondents were not localpeople or beach visitors (other than recreational day-visitors). Inaddition, in three regions out of four (see Table 1) the majority ofrespondents are not satisfied with coastal management by publicauthorities. In particular, as regards Italy, the fact that on Tarquiniabeach, Lazio Region, the vast majority of respondents (93%) are notsatisfied with actions taken by public authorities contrasts with thehigh consensus about public coastal management of respondents

E. Koutrakis et al. / Ocean & Coastal Management 54 (2011) 821e830 827

Author's personal copy

on Riccione Southern beach, in the Emilia-Romagna Region. Thisseems to show that there is a great difference in regional coastalmanagement due to the role played by authorities, which should bemore oriented towards the creation of expertises on ICZM.

As regards the role played by public authorities, Koutrakis et al.(2010) has shown that, in order to overcome the lack of informationand coordination between the institutions responsible for coastalzones, coordination and administrative integration of strategiesshould be promoted. Similar considerations can be found inGonzalez-Riancho et al. (2009) about the coastal managementassessment of other Mediterranean countries. These authorshighlight that the results of a recent survey on national coastalmanagement initiatives show a number of problems with theimplementation of ICZM strategies, and suggest that promotingpublic participation and administrative integration strategiesshould be the most active role played by public authorities. Thecomplexity introduced by the principle of subsidiary managementrecommended by the EU in documents such as the ESDP (EuropeanSpatial Development Perspective) is greatly challenging when co-ordinating a regional approach to local practice. In general, itseems that the integration of administration level competenciesand responsibilities requires further efforts from all stakeholders.

As regards coastal erosion it is significant that, despite theoverall low awareness demonstrated from stakeholders from theRegion of East Macedonia and Thrace (Koutrakis et al., 2010), visi-tors respond very positively to definitions and awareness of theerosion process in their coastal system. In contrast, the response tothe question “Have you ever noticed any problem linked to coastalerosion problem in this area?” shows a gap in awareness for NestosDelta beaches, East Macedonia and Thrace Region, and Riviera delBeigua, Liguria Region, where visitors are significantly mis-informed. This could be justified by the fact that visitors knowwhatbeach erosion is from the theoretical point of view but fail torecognise erosion effects and symptoms on the beach they use,particularly the consequences for people living on the seafront. Asregards this last point, several studies in Europe have highlightedthat residents have little awareness of the risks associated withcoastal erosion and there is often an expectation that engineeringstructures paid for from public funds should be implemented toprotect private properties (Carvalho and Coelh, 1998; Corrina DahmEconomos, 2002). This expectation could be modified by localauthorities or stakeholders who could (perhaps should) promotenot only a better and more responsible use of coastal resources butalso a lower demand for these resources.

As regards preferences about coastal defence structures, respon-dents are presented with a wide range of coastal defence structures(question 5: Which of the following coastal defence system do youprefer?). From the results it seems clear that respondents perceivecoastal defences to be necessary, even though no significant signs oferosion are easily visible in the Nestos Delta area. According toCarvalho and Coelh (1998), respondents’ preference about thedifferent coastal defence structures could be related to the type(natural versusurban) and the status (reflective versusdissipative) ofthe beach, and to respondent’s residence (along the coast or not).Even though the cost of these structuresmay be perceived as high, infour Regions out of five, themajority of respondents believe that it isjustified. In particular, we highlight the contrast between 80% ofvisitors to the Tarquinia beach, Lazio Region e a site which hadbenefits fromthe implementationofdefence structuresewhostatedthat expenditure for coastal defence is justified, and 63% of visitors toNestos Delta, East Macedonia and Thrace Region e an unspoiltnatural area where there is no perception of severe erosion e whostated that this cost is unjustified.

As regards the WTP, our results show that respondents recog-nise the need to fund the management of beaches (especially

coastal defence structures). Table 2 shows that the daily meanWTPs (zero included) ranges from V 0.5 to V 1.49 per day in theregions who estimated use values. By comparing these values, wesee that the Lazio Region (V 0.5) and the Languedoc-RoussillonRegion (V 0.77) have quite similar mean values, as do the EastMacedonia & Thrace Region (V 1.49) and the Liguria Region (V1.36). We highlight that the highest mean use value per day wasfound for Nestos Delta in the East Macedonia & Thrace Region. Ahigh WTP for the conservation and proper management of theprotected areas in the East Macedonia & Thrace Region was alsofound by Pavlikakis and Tsihrintzis (2006), who in their question-naire asked respondents to express their WTP per year for theprotection and management of the park area, and the weightedaverage WTP was found to be V 36.15.

As regards non-use values, in the Emilia-Romagna Region,visitors are willing to donate e other than the amount spent fordirect beach use e on average V 1.1 every five years for a beachdefence project.

More specifically, in Languedoc-Roussillon Region visitorsappear to be well focused on how much should be spent (over 85%indicate V 0.5e1.5); while as regards the Tarquinia beach, LazioRegion and the Riviera del Beigua, Liguria Region, more than 40% ofrespondentswouldnotpayanythingeven though theyare siteswithsomeexperience in costing shorelinemanagement andbeach accessfees. In this same line, visitors in Languedoc-Roussillon Regionwould place more pressure on the public sector to participate andfund the process, and want to keep beach access free of charge; justas in the Emilia-Romagna Region the majority of beach visitors aresatisfiedwith thewaypublic authoritiesmanage thecoast;while themajority of respondents unwilling to pay believe that publicauthorities should pay for beach defence. In the Liguria Region themajority of beach visitors are in favour of a private contribution tocoastal protection funding, even though they are more cautiouswhen directly asked about the potential role of beach users in thisissue, since to the question “According to you, which kind of paymentcould involve visitors’ participation to protect beaches?” half ofrespondents answered that beach managers should pay. A similarconsideration may be made from the results of Lazio Region survey.

It appears that when private properties, such as sunbathingestablishments, are present on the beach, they should not neces-sarily be defended as happens with public facilities. This is the newperspective of social justice (Novak, 2002; Barry, 1995) applied tocoastal erosion that pertainsmainly in caseswhere private propertyis threatened. In short, from this perspective, not onlymay residentsand property owners face direct financial loss from coastal erosion,but the general public may also incur losses other than purelyfinancial due to a public intervention for defending private proper-ties. More specifically, at societal scale, a society may perceive someconsequences of coastal defence structures as a loss of welfare ifintergenerational equity, non-coastal resident preferences, climateand sea level change, and environmental changes are not consideredin their implementation (Cooper and McKenna, 2008).

5. Conclusions

The results described in this paper show that there is low publicawareness as regards ICZM, erosion and coastal defence systemsissues in all of the European Mediterranean areas where the surveywas carried out. In order to overcome these problems, promotion ofthe following is recommended:

� Education, training and public awareness: The promotion ofeducation, training and public awareness is a key issue asregards the Mediterranean coastal zones. Countries/regionsaround the Mediterranean need a commitment to train

E. Koutrakis et al. / Ocean & Coastal Management 54 (2011) 821e830828

Author's personal copy

experts, educate children and promote public awareness. Theexample of the Coast Day (24th October) is positive and mayalso lead to other efforts.

� Identification of local need for the implementation of demand-driven specific studies: The need for detailed analysis andstudies on coastal issues is generally recognized. Particularattention should be given to the relationship between localauthorities and academia, and to territorial and visitors’ needs,assessed through specific surveys, in order to increase effi-ciency in coastal management (i.e. the application of a sub-regional spatial e land and marine e planning approach).

According to an ICZM perspective, the involvement of privatestakeholders (residents, visitors, etc.) is necessary to create a dia-logue towards a concerted management of coastal zones. None-theless, since beaches are not really perceived as dynamic coastalsystems, people do not perceive coastal use as contributing tocoastal erosion. As a consequence, there is a need to designcommunication tools between public stakeholders and populationtowards a change in people’s attitude towards, and an evolution oftheir perception of, beaches as natural areas. This should contributeto a greater awareness of coastal erosion, an increased acceptabilityof its consequences and a realignment of public policies.

Acknowledgements

The research was carried out in the framework of an INTERREGIIIC Sud BEACHMED-e sub-project entitled: “ICZM-MED: Concertedactions, tools and criteria for the implementation of the IntegratedCoastal Zone Management in the Mediterranean”, co-financed bythe EU under the auspices of the Regional Framework OperationBEACHMED-e (Strategic management of beach protectionmeasures for the sustainable development of Mediterraneancoastal areas (2006e2008), http://www.beachmed.eu). We wouldlike to thank Prof. Jane Johnson for her valuable help in order toimprove the manuscripts’ language.

References

ACT Ouest, SCE Montpellier, 2006. Les plages du Languedoc-Roussillon un capital àpréserver, à quels coûts? Étude réalisée pour la MIAL-LR, pp. 75.

APT, 2004. Indagine sulla domanda turistica nella Provincia di Viterbo. Avail.Online: http://www.provincia.vt.it/turismo/domandaTuristica2004.htm.

Arrow, K., Solow, R., Portney, P.R., Learner, E.E., Radner, R., Shuman, H., 1993. Reportof the NOAA Panel on Contingent Valuation. Report to the general Counsel ofthe US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, US Department ofCommerce. Natural resource damage assessments under the Oil Pollution Act of1990. Federal Register 58 (10), 4601e4614.

Barry, A., 1995. Treatise on Social Justice. In: Justice as Impartiality, vol. II. ClarendonPress, Oxford, pp. 336.

Bell, F.W., 1986. Economic policy issues with beach nourishment. Policy StudiesReviews 6, 374e381.

Billé, R., 2007. A dual-level framework for evaluating integrated coastal manage-ment beyond labels. Ocean & Coastal Management 50, 796e807.

Blakemore, F., Williams, A.T., Coman, C., Micallef, A., Unal, O., 2002. A comparison oftourist evaluation of beaches in Malta, Romania and Turkey. Journal of WorldLeisure 2, 29e41.

Breton, F., Clapes, J., Marques, A., Priestle, G.K., 1996. The Recreational use of beachesand consequences for the development of new trends in management: the caseof the beaches of the Metropolitan Region of Barcelona (Catalonia, Spain).Ocean & Coastal Management 32 (3), 153e180.

Buanes, A., Jentoft, S., Maurstad, A., Søreng, S.U., Karlsen, G.R., 2005. Stakeholderparticipation in Norwegian coastal zone planning. Ocean & Coastal Manage-ment 48 (9e10), 658e669.

Carvalho, T.M.M., Coelh, C.O.A., 1998. Coastal risk perception: a case study in Avierodistrict, Portugal. Journal of Hazardous Materials 61, 263e270.

Cervantes, O., Espejel, I., 2008. Design of an integrated evaluation index for recre-ational beaches. Ocean & Coastal Management 51, 410e419.

Chaniotis, P., Stead, S., 2007. Interviewing people about the coast on the coast:appraising the wider adoption of ICZM in North East England. Marine Policy 31,517e526.

Cicin-Sain, B., Knecht, R.W., 1998. Integrated Coastal Management: Concepts andPractices. Island Press, Washington, D.C, p. 543.

Cooper, J.A.G., McKenna, J., 2008. Social justice in coastal erosion management: thetemporal and spatial dimensions. Geoforum 39 (1), 294e306.

CorrinaDahmEconomos, 2002. BeachUserValues andPerceptionsofCoastal Erosion.EnvironmentWaikato Technical Report. EnvironmentWaikato Regional Council.

Dahm, C., 2003. Beach User Values and Perception of Coastal Erosion, Reportcommissioned by the Environment Waikato. Technical Report, pp. 68.

Deboudt, P., Dauvin, J.-C., Lozachmeur, O., 2008. Recent developments in coastalzone management in France: the transition towards integrated coastal zonemanagement (1973e2007). Ocean & Coastal Management 51, 212e228.

Dimitrakopoulos, P.G., Jones, N., Iosifides, T., Florokapi, O.L., Paliouras, F.,Evangelinos, K.I., 2010. Local attitudes on protected areas: evidence from threeNatura 2000 wetland sites in Greece. Journal of Environmental Management 91(9), 1847e1854.

Dipartimento Territorio Regione Lazio, 2006. Attività di ricognizione della costalaziale, (recognition activity of Lazio coast) Regione Lazio.

Edwards, S.D., Jones, P.J.S., Nowell, D.E., 1997. Participation in coastal zonemanagement initiatives: a review and analysis of examples from the UK. Ocean& Coastal Management 36 (1e3), 143e165.

EEA (European Environment Agency), 2006. The Changing Face of Europe’s CoastalAreas, Report no 6. pp. 112.

European Commission (EC), 2007. Communication from the Commission - Report tothe European Parliament and the Council: An Evaluation of Integrated CoastalZone Management (ICZM) in Europe, COM 308, pp. 10. http://ec.europa.eu/environment/iczm/.

Gonzalez-Riancho, P., Sano, M., Medina, R., Garcıa-Aguilar, O., Areizaga, J., 2009.A contribution to the implementation of ICZM in the Mediterranean developingcountries. Ocean & Coastal Management 52, 545e558.

Gore, S., 2007. Framework development for beach management in the British VirginIslands. Ocean & Coastal Management 50, 732e753.

Istat, 2001. Censimento generale delle popolazioni e delle abitazioni. (GeneralCensus of populations and homes). www.istat.it (May 2006).

Jentoft, S., 2000. Commentary - co-managing the coastal zone: is the task toocomplex? Ocean & Coastal Management 43, 527e535.

Johnson, D., Dagg, S., 2003. Achieving public participation in coastal zone envi-ronment impact assessment. Coastal Conservation 48, 222e245.

King, O.H., 1995. Estimating the value of marine resources: a marine recreation case.Ocean & Coastal Management 27, 129e141.

Koutrakis, T., Sapounidis, A., Marzetti, S., Giuliani, V., Martino, S., Fabiano, M.,Marin, V., Paoli, C., Roccatagliata, E., Salmona, P., Rey-Valette, H., Roussel, S.,Povh, D., Malvárez, C.G., 2010. Public stakeholders’ perception on ICZM, coastalerosion and coastal defence systems. Coastal Management Journal 38, 354e377.

Macleod, M., Pereira Da Silva, C., Cooper, J.A.G., 2002. A comparative study of theperception and value of beaches in rural Ireland and Portugal: implications forcoastal zone management. Journal of Coastal Research 18 (1), 14e24.

Marin, V., Palmisani, F., Ivaldi, R., Dursi, R., Fabiano, M., 2009. Users’ perceptionanalysis for sustainable beach management in Italy. Ocean & Coastal Manage-ment 52 (5), 268e277.

Marzetti, S., 2007. Visitors’ preferences about beach defence techniques and beachmaterials. In: Burcharth, H.F., Hawkins, S.J., Zanuttigh, B., Lamberti, A. (Eds.),Environmental Design Guidelines for Low Crested Coastal Structures. Elsevier,Oxford, pp. 372e374.

Marzetti, S., 2009. Recreational demand functions for different categories of beachvisitors. Tourism Economics 15 (2), 339e365.

Marzetti, S., Franco, L., Lamberti, A., Zanuttigh, B., 2009. Socio-economic preferencesabout beaches defended from erosion: some Italian case-studies. In: Franco, L.,Tomasicchio, G.R., Lamberti, A. (Eds.), Proceedings of the 5th InternationalConference Coastal Structures, Venice (Italy), July 2e4, 2007. World Scientific,Singapore, pp. 442e453.

McConnell, K.E., 1977. Congestion and willingness to pay: a case study of beach use.Land Economics 53 (2), 185e195.

Micallef, A., Williams, A.T., 2004. Application of a novel approach to beach classi-fication in the Maltese Islands. Ocean & Coastal Management 47, 225e242.

Mitchell, R.C., Carson, R.T.,1998. Using Surveys to Value Public Goods: The ContingentValuation Method. Resources for the Future, Washington, D.C., pp. 463.

Nelson, C., Botterill, D., Williams, A.T., 2000a. The beach as a leisure resource:measuring beach user perception of beach debris pollution. Journal of WorldLeisure and Recreation 42, 38e43.

Nelson, C., Morgan, R., Williams, A.T., Wood, J., 2000b. Beach awards andmanagement. Ocean & Coastal Management 43, 87e98.

Novak, M., 2002. Defining Social Justice, vol. 108. First Things, pp. 11e13.PAR/PAC, 2002. Integrated coastal zone management in the Mediterranean: from

concept to implementation. In: MAP/METAP Workshop: CAMP: Improving theImplementation, Malta, January 17e19, pp. 252.

Pavlikakis, G.E., Tsihrintzis, V.A., 2003. A quantitative method for accounting humanopinion, preferences and perceptions in ecosystem management. Journal ofEnvironmental Management 68, 193e205.

Pavlikakis, G.E., Tsihrintzis, V.A., 2006. Perception and preferences of the localpopulation in eastern Macedonia and Thrace National Park in Greece. Land-scape and Urban Planning 77, 1e16.

Pendleton, L., Martin, N., Webster, D.G., 2001. Public perception on environmentalquality: a survey study of beach use and perception in Los Angeles County.Marine Pollution Bulletin 42 (11), 1155e1160.

Pereira, L.C.C., Jiménez, J.A., Medeiros, C., Marinho Da Costa, R., 2003. The influenceof the environmental status of Casa Caiada and Rio Doce beaches (NE-Brazil) onbeaches users. Ocean & Coastal Management 46 (11e12), 1011e1030.

E. Koutrakis et al. / Ocean & Coastal Management 54 (2011) 821e830 829

Author's personal copy

Peterlin,M., Kontic, B., Kross, B.C., 2005. Public perceptionof environmental pressureswithin the Slovene coastal zone. Ocean & Coastal Management 48 (2), 189e204.

Phillips, M.R., House, C., 2009. An evaluation of priorities for beach tourism: casestudies from South Wales, UK. Tourism Management 30, 176e183.

Pickaver, A.H., Gilbert, C., Breton, F., 2004. An indicator set to measure the progressin the implementation of integrated coastal zone management in Europe.Ocean & Coastal Management 47, 449e462.

Polomé, P., Marzetti, S., Van Der Veen, A., 2005. Economic and social demands forcoastal protection. Coastal Engineering 52, 10e11.

Provincia di Viterbo, 2006. Rapporto sullo stato dell’ambiente.Roca, E., Villares, M., 2008. Public perceptions for evaluating beach quality in urban

and semi-natural environments. Ocean & Coastal Management 51, 314e329.Santos, I.R., Friedrich, A.C., Wallner-Kersanach, M., Fillmann, G., 2005. Influence of

socio-economic characteristics of beach users on litter generation. Ocean &Coastal Management 48, 742e752.

Shivlani,M., Letson, D., Theis,M., 2003. Visitor preferences for public beach amenitiesand beach restoration in South Florida. Coastal Management 31, 367e385.

Silberman, J., Klock, M., 1988. The recreational benefits of beach renourishment.Ocean & Shoreline Management 11, 73e90.

Stead, S., 2005. A comparative analysis of two forms of stakeholder participation inEuropean aquaculture governance: self-regulation and integrated coastal zone

management. In: Grey, T. (Ed.), Participation in Fisheries Governance. Springer,Netherlands, pp. 179e192.

Tran, K.C., 2006. Public perception of development issues: public awareness cancontribute to sustainable development of a small island. Ocean & CoastalManagement 49, 367e383.

Tran, K.C., Euan, J., Islac, M.L., 2002. Public perception of development issues:impact of water pollution on a small coastal community. Ocean & CoastalManagement 45, 405e420.

Turbow, D., Lin, T.H., Jiang, S., 2004. Impacts of beach closures on perceptions ofswimming-related health risk in Orange County, California. Marine PollutionBulletin 48, 132e136.

UNEP/MAP/PAP, 2008. Protocol on Integrated Coastal Zone Management in theMediterranean, pp. 89.

Villares, M., Roca, E., Serra, J., Montori, C., 2006. Social perception as a tool for beachplanning: a case study on the Catalan coast. Journal of Coastal Research 48,118e123.

Whitemarsh, D., Northen, J., Jaffry, S., 1999. Recreational benefits of coastalprotection: a case study. Marine Policy 23 (4e5), 453e463.

Xeidakis, G.S., Delimanis, P.K., Skias, S.G., 2006. Sea cliff erosion in the eastern partof the north Aegean coastline, northern Greece. Journal of EnvironmentalScience and Health 41, 1989e2011.

E. Koutrakis et al. / Ocean & Coastal Management 54 (2011) 821e830830