dipinti, alto antiquariato e oggetti d'arte fine art, paintings ...

"I dipinti"

Transcript of "I dipinti"

October 11, 2022

The Paintings Trade, 1450-1650

Neil De Marchi

With contributions by Louisa C. Matthew*

Prepared for Il Rinascimento Italiano e l’Europa: Commercio e cultura mercantile

* Our thanks to Isabella Cecchini, Maria Gilbert and Filip

Vermeylen, each of whom supplied detailed answers to what at times

must have seemed like an unending stream of questions. We are even

more indebted to Miguel Falomir who, over many months, shared his

1

extensive knowledge of Italian paintings and painters in Spain and

how they came to be there. All these friends saved us from errors,

but they are not responsible for the uses to which we have put the

information we extracted from them. Thanks too, to Jeroen

Puttevils, who generously allowed us to refer to research in

progress that is part of his master’s thesis. We are also grateful

to the editors, who discussed with us, suggested references and

rendered helpful advice.

Task and Method

We bring to this essay a shared interest in the economic

circumstances of paintings in the early modern period, plus

specialist knowledge of Venetian sixteenth-century painting and of

art markets in the Southern Netherlands (fifteenth-seventeenth

centuries) and the Dutch Republic (seventeenth century). Neither

is expert in Italian or European economic history. These

admittedly patchy competencies interact in this instance with what

searches suggest may be an almost total dearth of interest by past

economic historians in the export trade in Italian paintings.

Italian and other art historians, by contrast, have identified

flows of paintings, though normally their interest extends to

“significant” paintings only, and does not encompass the overall

volume or mechanisms involved. Moreover, the information they

2

provide is spread across a huge number of monographic studies. In

the short time available to us we could not hope to create a

database of exports or imports of Italian paintings from such

sources.1 That would have required a team effort and several years.

In lieu, therefore, of an empirical statement about numbers

and cross-border flows – though there will be probes of that sort

– we propose to focus on the mechanisms, illustrating with

specific examples. This yields an array of mechanisms for moving

Italian paintings that can be compared with, and assessed against,

what is known to have worked in the comparatively well-studied

international traffic in early modern Netherlandish paintings, in

particular exports from Antwerp.

Northern export-marketing mechanisms, of course, did not

develop in a vacuum; those that emerged did so in contexts where

output was high relative to local demand. Moreover, for cities

that appear to have been sustained net exporters of paintings –

Mechelen (Malines) and Antwerp, for example – there were

collateral circumstances that facilitated exporting. To take just

Antwerp, for much of the sixteenth century in that city there was

a resident population of foreign merchants and agents from various

places, a population that may have doubled temporarily at the

1 Our charge is to discuss trade, but we will focus rather more on exports to facilitate comparison with Antwerp.

3

times of the city’s two annual fairs. For a long time too local

dealers in Antwerp needed only to perform as sedentary suppliers

and intermediaries, for the city authorities in Antwerp took

special measures to ensure healthy exports of paintings by linking

local dealers with foreign merchant buyers in the physical

environment of a new Exchange (borsa, or in Flemish, beurs), which

opened in 1540. The upper floor of the beurs comprised stalls, 100

in all, devoted exclusively to the display and sale of pictures

(paintings plus prints, which were often hand-painted). The

Exchange was the last of a series of panden or cloister-like

structures used for selling paintings. In the final one-third of

the sixteenth century, largely because of religious strife, the

foreign merchants left Antwerp and the beurs pand lost its

rationale. At the same time a transformation among dealers began,

appropriate to their altered circumstances. Antwerp dealers became

less sedentary, many in the seventeenth century undertaking annual

or at least frequent forays by land into markets such as those of

the Dutch Republic, Paris, Lille and its neighboring cities, and

cities in southern Germany, in concert with artists and other

dealers. Others set up as exporters, by land and sea, and their

businesses had something of the character of vertically-integrated

enterprises. Those we know about were family firms and used family

4

capital, hence were not large; they maintained their own stables

of artists, though on a need-only basis; and they depended on

contacts abroad (friends, family or commission agents on a short

leash) to feed them orders and to sell the paintings shipped in

fulfilment thereof.

We shall try to establish, using illustrative exports of

paintings from Italy to Spain, whether these occurred in

conjunction with a stable marketing infrastructure such as the

sixteenth-century Antwerp beurs pand, or according to the

seventeenth-century Antwerp models involving dealers as merchants

who more or less specialized in paintings. Since we will confine

ourselves to instances of exporting from Italy to Spain and have

no way of knowing whether these were representative, our results

must be viewed as tentative. Our purpose in short is modest: we

offer the structures just sketched and which facilitated the

export of paintings from the Southern Netherlands on a sustained

basis as a point of reference in relation to which to consider the

situation in Italy. This approach, we hope, will serve future

researchers.

The study of Netherlandish, or Northern, art markets by

economists and economic historians has

5

been pursued, as one might expect, partly by way of quantifying

key parameters. We will ask what sorts of quantification, in

principle, would aid future investigators of our subject in the

Italian context, comparing the answers with what is available for

the Dutch Republic and the Spanish Netherlands. Then we will

explore illustrative instances of the export of paintings from

Italy to Spain, focusing on the mechanisms involved. Lastly, we

will examine more closely the trade in paintings to and – mostly -

from one city, Venice, as a check on our inferences from our

assembled instances of exports from Italy to Spain. To give a

somewhat more complete picture, mention will also be made of known

exports of cheap imagery from some other places, and of imports of

paintings from Bruges to Florence in the fifteenth century. But

our essay is primarily a methodological exercise, not a factual

overview.

Parameters for understanding Italian exports of paintings

As a first step, it would be helpful to have a rule of thumb

for distinguishing net importer from net exporter cities. A rule

that seems to work fairly well for the North is that cities with a

ratio of artists to population ('000) consistently and

significantly greater than 1.0 were net exporter cities. Economic

6

historian Michael Montias examined the principal city of work of

artists to whom paintings were attributed in seventeenth-century

Amsterdam inventories. This revealed Amsterdam to have been a

consistent importer and, since Montias judged exports to have been

small, in effect a net importer. In connection with comparative

work on artist-to-population ratios in Dutch cities, Montias also

showed that Amsterdam did not have a ratio greater than 1.0 even

in its most productive years. By contrast, cities in the Southern

Netherlands such as Mechelen and Antwerp which, on other grounds, are

known to have been strong exporters, had ratios for the sixteenth

and seventeenth centuries in the ranges 3.5 to 5.3 and 1.3 to 2.4,

respectively. Formidable problems in deriving such ratios include

settling on a meaningful definition of “artist” and deciding who

met the criteria. Tentative steps have been taken to derive ratios

for sixteenth and seventeenth-century Venice, seventeenth-century

Rome, seventeenth-century Paris, and late-fifteenth-century

Florence. Preliminary results suggest that the latter two were net

importers and Rome a net exporter, using as cut-off for a net

exporter a ratio somewhat in excess of 1.0. Venice almost

certainly exceeded that cut-off in the late fifteenth and early

sixteenth centuries, but whether it was a net exporter in the

seventeenth and eighteenth centuries is not clear. In fact the

7

measurement problems have not been resolved for any of the three

Italian cities, and the results for them will certainly undergo

revision.2 A team project underway and led by Richard Spear,

covering Italian cities in the seventeenth century, promises to

improve our understanding and our estimates considerably. For now,

little weight should be put on the preliminary results noted for

the Italian cities; those for the Dutch Republic and the Southern

Netherlands, however, are reliable enough for our purposes here.

Just why is such a distinguishing rule important? A city

which consistently produces more paintings than are needed to

satisfy local demand must of necessity develop roles and

2 Ratios are given in a table in the apppendix to Neil De Marchi and Hans J. VanMiegroet, “The History of Art Markets,” chapter 3, volume 1 of Handbook of the Economics of Art and Culture, V. Ginsburgh and D. Throsby eds., Amsterdam, Elsevier, 2006. That table, however, is to be used with caution. Documents that seem likely sources for the numbers of artists – guild records, for example – oftenare incomplete, may give only annual registrations of new artists rather than total numbers year by year, frequently include painters of many sorts other thanfigural artists, and so on. Alternative sources sometimes exist: occupational censuses or tax rolls, for example, but definitional issues arise there too, anduncertainty surrounds the coverage. Official counts, therefore, and for simlar reasons lists recorded by contemporary observers, ordinarily require checking person by person for one to feel confident that one has grasped their construction and can assess their usefulness. But that can take years and the process often never ends. In the circumstances and for many cities there is no such thing as a single best estimate. Moreover, consistency across cities is virtually impossible to achieve. Nor are the problems all documentary. Instead, local cultures and clashes of interest are involved. Differences in the mix between craft, commercial and consumer interests necessarily affect who should be called artist. Our hope was that, these difficulties notwithstanding, if artist to population ratios could be arrived at for a wide range of cities, across time, a clear pattern might emerge which could be compared with what one would expect based on known economic circumstances. In other words, the ratios themselves are to be viewed as reflections of underlying economic conditions. Asindicated, the ratios are more reliable for Netherlandish cities than for Italian, and the match with economic circumstances clearer.

8

mechanisms, including elements of infrastructure, to facilitate

exports: shipping and insurance capabilities, credit arrangements,

networks of factors, agents, or partners abroad, and so on. These

must be in place if an export trade is to be maintained over time,

and they should be visible to historians.

Numbers of artists – the numerators in the ratios referred to

– are important also in getting at the total production of

paintings in a city. Total output matters because with larger

scale comes the opportunity to specialize. We would not expect

quasi-specialist dealers of the sort that emerged in Antwerp in

cities where few paintings were made.

Knowing total output matters as well because production minus

local demand = the exportable surplus; knowing output is thus a

step towards ascertaining by an independent route whether a city

was indeed a net exporter. In principle, calculating local demand

is straightforward. Inventory studies will reveal the average

number of paintings held per household, generation by generation.

Those numbers combine new demand and surviving old stock. The two

can be distinguished if we impose a rate of loss from inherited

stock. The number of new paintings added in each generation then

follows by combining the observed holdings of each generation with

9

the loss rate (see notes 24 and 26, and the descriptive appendix,

below).

Total production, of course, will reflect the population of

artists and productivity per artist. If these numbers, adjusted

for unregistered foreigners, are known from guild records, and

from artist’s contracts, respectively, or if productivity can be

inferred from known annual incomes of artists and the average

prices of paintings, then we have total new supply and can compare

this with demand. As noted, an excess implies an exportable

surplus. These calculations have all been attempted for the Dutch

Republic and some of them, using similar methods, for the

Mechelen-Antwerp production complex. An appendix outlines the

methods applied to the Dutch Republic.

There is a particular value for us in being able to connect

surviving paintings with earlier totals by way of a rate of

“depreciation” or loss. For, in the specific case of the traffic

in paintings from Italy to Spain we know, from the Getty Spanish

Inventories database, the numbers of paintings attributed to

Italian artists and surviving in private Spanish inventories,

1601-1773. By postulating a beginning stock and applying what

seems to us an appropriate rate of loss – we use 20 percent for

each generation (assumed to be of twenty years) or roughly 40

10

percent survival after four generational changes (100→80→64→51→41)

– plus some numbers for shipments each generation, we reach a

total number for surviving paintings that roughly comports with

that in the Getty database. This number can then be adjusted

upwards to allow for attributions to Italian painters in non-

private holdings. Having even a tentative estimate for total

shipments from Italy to Spain gives us a sense of the scale of

such exports relative to shipments from the Southern Netherlands,

and thus a hint, from yet another direction, as to what we might

expect to have been present in Italy in the way of mechanisms to

facilitate exports. The question for our section on Venice thus

becomes, is there direct evidence in that city for the presence of

such mechanisms?

As noted, we shall begin by exploring instances of exports to

Spain, from Italian cities. Our interest here, remember, is

confined to the mechanisms involved. The examples cover the period

1570-1650, though the period of greatest in Italian paintings in

Spain really extends to 1700.

How did paintings move from Italian cities to Spain?

We may start with a shipment noted by Isabella Cecchini: from

Venice to Cadiz, in 1647, by the

11

merchant in beads Maffio Marinoni.3 In this particular shipment

Marinoni included combs and fans along with beads, plus some

chests containing small paintings. Those paintings for which a

subject was given were of individual saints, which was a popular

sort of devotional image in Spain. The cost of paintings shipped

by this merchant is known in two other instances, and the monetary

amounts are trifling. From that and the very sparseness of

archival records relating to such shipments, Cecchini concludes

that the traffic was not very significant, perhaps more occasional

and opportunistic than regular or large in volume. It is hard to

judge this without knowing more, but we can add something by

comparing aspects of Marinoni’s shipment to Cadiz with others,

from Florence, Rome and Naples.

Christopher Marshall, for example, notes that in 1623 a

certain Spaniard, Jusepe de Torcalina, temporarily in Naples,

contracted with the little-known Neapolitan painter Dominico

d’Aquino to execute in one month 100 paintings on copper, each to

contain the figure of a saint. The rate of production was 25

paintings per week at ½ a ducat each, less expenses.4 We are not 3 “Troublesome Business: Dealing in Venice, 1600-1750,” in Neil De Marchi and Hans J. Van Miegroet eds., Mapping Markets for Paintings in Europe, 1450-1750, Turnhout, Brepols, 2006, pp. 116-122. See also Cecchini, Quadri e commercio a Venezia durante il Seicento. Uno studio sul mercato dell’arte, Venezia, Marsilio, 2000, p. 230. 4 ? Marshall, “Dispelling Negative Perceptions: Dealers Promoting Painters in Seventeenth-century Naples,” in De Marchi and Van Miegroet eds., Mapping Markets, cit., pp. 363-380. Note that this contract gives us one observation of

12

told the destination of these paintings, but the similarity to the

Venetian shipment – in terms of subject matter and likely cost per

painting – suggests that the two were part of a larger traffic in

dirt cheap, serially made, small devotional images. We know also

of a Flemish painter in Rome, Pieter Vlerick (1539-1581), who is

said by an informed contemporary to have made cheap works on

copper in great quantity, for export to the Iberian peninsular.5

And we know of a shipment in 1605 of two crates of paintings from

Florence, by Raphael de Ciaperoni, to Valladolid, temporary home

of the Spanish Hapsburg court. There were 170 paintings in these

two crates, all but six of them single-figure devotionals. After

more than seven years only 85 of the paintings had sold, at an

average price of just under 14 reales, or one and a half to two

times the daily wage of a construction worker in Seville. The

seller’s wife deducted costs, which reduced the price owed the

consignor to 8.6 reales, or, allowing for transport costs, perhaps

not much more than the half ducat cost of the paintings mentioned

above from Venice and Naples (0.5 ducat = 5.5 reales).

productivity at the low end of the primary market. Another, from a contract madein Seville, in July 1600, is discussed below. 5 This, and the information on the shipment from Florence, is from Miguel Falomir, “Artists’ Responses to the Emergence of Markets for Paintings in Spain., c.1600,” in De Marchi and Van Miegroet eds, Mapping Markets, pp. 135-161, in the case of Vlerick (p. 144, n. 45), citing Karel Van Mander, author of the first lives of Netherlandish painters, Het Schilderboek, Haarlem, 1604.

13

The original selling agent in this instance was court artist

Bartholomé Carducho (1560-1608), whose wife assumed the task of

selling the paintings after he died. Carducho hailed from

Florence; he was brother to Vicente Carducho (ca. 1576/78-1639),

who settled in Seville and authored a seventeenth-century treatise

on painting. Bartholomé Carducho is known as a maker of copies and

for dealing in imported paintings, in both cases at prices between

14 and 16 reales, though some of his own originals were priced

much higher. His clients, for both cheap and costly paintings,

included nobles, among them the prominent collector, the Duke of

Lerma.6

A difference between the Venetian and the Florentine

shipments is that the one from Venice went to Cadiz. This tells us

that it was probably intended for the Americas; for, from around

the middle of the century, Cadiz replaced Seville as the port of

shipment and transhipment to the vice-royalties of New Spain,

Mexico and Peru. It was also exceptional for paintings to be

shipped from Venice to Cadiz.7 Paintings from Italy for Spanish

domestic markets were normally shipped to Cartagena. Early in the

6 Falomir, “Artists’ Responses,” cit., pp. 129, 131, 133-134; and Falomir, “The Value of Painting in Renaissance Spain,” in Economia e Arte. Secc. XIII-XVIII, Atti della “trentatreesima Settimana di Studi”, Istituto Internazionale di Storia Economica “F. Datini”, Prato, 30 Aprile-4 Maggio, 2001, S. Cavaciocchi ed., Florence, Le Monnier, 2002, pp. 231-260; esp. p 243, and pp. 255-260. 7 Information from Miguel Falomir.

14

seventeenth century, for example, we find the Florentine painter

Pietro Sorri sending paintings to Bartholomé Carducho, with

Sorri’s nephew Salustio Lucchi in Cartagena likely acting as

intermediary.8

The Americas trade was high volume. At its peak, in 1600, we

find one Gonzalo de Palma contracting with the Sevillian painter

Miguel Vàzquez to produce not 100 but 1,000 “portraits” of secular

figures, all of the same size (0.75 varas high and 0.5 varas wide

= 63cm x 42), at the rate of 25 per week, for a price – 4 reales

each – even lower than the serial paintings on copper commissioned

in Naples in 1623.9 As noted, Seville at the time being the port of

exit for New Spain, these portraits probably were meant for the

vice-royalties. Cecchini may be right in thinking that the volume

of exports of cheap paintings from Venice to Cadiz was not very

great, but it fed into a more considerable flow across the

Atlantic.

What do we have so far? (a) There was a trade in small

paintings from Spain to the Americas, and there is circumstantial

8 Falomir, “Artists’ responses,” cit., p. 134, citing José C. Agüera Ros, “El comercio de cuadros Italia-España a través del Levante español a comienzos del siglo XVII,” Imafronte (1990-1991), pp. 11-18.9 For details of the Vasquez contract see Falomir, “Artists’ Responses,” cit., p. 127. Falomir (ib. p. 128) observes that 4 - 6.5 reales was the norm for “small” paintings (63cm x 42 or 0.75 varas x 0.5), whereas standard larger canvases (103cm x 84.5 or 1.23 varas x 1.0) sold for between 14 and 16 reales.

15

evidence that shipments contributing to it came from Venice,

Naples and Rome, even if possibly only on an occasional basis. (b)

Paintings commissioned for this low-end trade were predominantly

serial devotional images, mainly of individual saints. (c) From

knowledge of the terms of contracts for serial work in both

Seville and Naples, we infer that the going price for such

paintings was around half a ducat apiece. (d) Some of these

paintings were made on copper, a support rarely used by painters

in Spain, though it was frequently employed by artists in Antwerp

for paintings to be shipped to Spain and the vice-royalties of

Mexico and Peru. (e) This, together with the information that at

least some of these cheap paintings originated in Venice, Naples

and Rome, in all three of which there were colonies of Flemish

painters, raises the possibility that exports of these low-end

paintings from Italy was in effect an extension of the large-scale

export trade from Antwerp itself.10 Subject, size, price and, as

far as we can tell, methods of acquisition and shipment in the

cases cited were all similar to those used by trader-dealers in

10 Miguel Falomir raised this possibility with us, though not quite in these terms, on the basis of the shipments from Naples and Rome. We elect to extend the coverage to Venice. The Flemish artists’ colony there may have been less extensive, but just as in the Naples case, paintings “alla fiammenca” were plentiful (to judge from inventories) whether or not made by Flemish artists. Falomir informs us that such paintings are recorded as “a la Flamenca” in Spanish inventories; though some originated in Italy they are hardly ever identified as Italian.

16

Antwerp in the early seventeenth century, and it may be that the

practice and mechanism were simply transplanted to Italy, whether

or not Flemish artists were directly involved in all cases.

Of course Antwerp practice was not secret and Italian dealers

and merchants could easily have copied its basic elements:

commissioning serial devotional work from artists, and shipping in

bulk. Antwerp was part of a joint production complex with nearby

Mechelen and there were Italians in Mechelen in the sixteenth

century involved in the art trade. This suggests that Antwerp

methods could have reached Italy via Italians abroad and become

part of a trade originating in Italian cities well before the

early- and mid-seventeenth century shipments we are able to cite.11

As far as we know, however, there is no strong evidence for the

existence, before the eighteenth century, of Italian dealer-

traders who were more or less specialized in exports of paintings

which they also commissioned and financed in the first instance.

In two of the four cases cited above the key figures were not

Italian, and in the other two, where the principals were Italian,

it is not known whether their shipments were part of a regular

traffic. During the sixteenth century, and earlier, there was a

flow of Flemish paintings into Spain; these sold mainly at fairs,

11 See Neil De Marchi and Hans J. Van Miegroet, “The Antwerp-Mechelen Production and Export Complex,” forthcoming.

17

such as that of Medina del Campo, and the merchants involved dealt

principally in more valuable art objects, such as tapestries,

sculptures, musical instruments, though also prints.12 Not only was

there nothing like the same flow of low-end paintings from Italy

to Spain in this era – the exception is Byzantine icon types, on

which more below – but Italian merchants importing paintings from

Antwerp to Italy appear to have gone through Flemish dealers

rather than commissioning direct from artists, especially when

buying in quantity, and to have used Flemish shippers.13 This

points away from such merchants having been vertically integrated

in the same way as Flemish merchants in paintings were in the

seventeenth century and possibly earlier.

Up to this point we have been discussing mainly low-end,

devotional images. Now we turn to high-end acquisitions. Within

the high-end trade it is useful for some purposes to distinguish

between acquisitions by the Royal Court, Church-related buying and

acquisitions by private Spanish collectors. As Miguel Falomir has

reminded us, Spanish Hapsbug acquisitions involved methods similar

12 Information from Miguel Falomir; see examples in his “The Value of Painting”, cit., p. 234; also Filip Vermeylen, Painting for the Market. Commercialization of Art in Antwerp’s Golden Age, Turnhout, Brepols, 2003, pp. 79-99. 13 Lorne Campbell, “The Art Market in the Southern Netherlands in the Fifteenth Century,” The Burlington Magazine, 118 (1976), pp. 188-198, esp, p, 197; Vermeylen, Painting for the Market, cit., p. 83. Vermelyen reports that, according to the Antwerpexport registers, 1543-1545, just 9 percent of paintings went to Italy versus 34percent to Spain and Portugal: ib., p. 82. See below for a discussion of shipments involving paintings to Italy from Antwerp in 1544.

18

to those of many other courts: gift, persuasion and outright

claims on others’ property under a variety of pretexts. He also

points out that what was acquired depended heavily on the taste of

the monarch of the moment. Since, however, our concern is to

discover what we can about Italian trading in paintings where

there was regular shipment and significant numbers were involved –

in other words, with paintings as commodity – we have little to

say about Royal acquisitions.14 Institutional Church acquisitions

were also special – altarpieces or paintings of particular

subjects for pre-designated placement – and they too fall outside

our painting-as-commodity scope. For the rest we know most about

aristocratic collectors: they used means ranging from employing an

agent to direct purchase from an artist. Our purpose, recall, is

to identify mechanisms by which Italian paintings moved to Spain.

The instances we will now list collectively enable us to supply a

fairly extensive typology of ways of dealing, or mechanisms for

moving paintings from Italy to Spain.

(1) Private individuals and other Spaniards in Italy on

official business bought Italian paintings or commissioned them,

14 See, however, the excellent and detailed discussion in Jonathan Brown, Kings & Connoisseurs. Collecting Art in Seventeenth-Century Europe, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1995.

19

direct and for their private use, or for official despatch. The

Spanish court

collections over an extended period benefited from the latter type

of purchase. Among officials

acquiring and despatching paintings back to Spain for the court

there was Guzmàn de Silva,

ambassador to Venice, 1569-78. In 1574, just four years after

Philip II settled the Hapsburg court in Madrid, Guzmàn shipped a

“Story of Jacob” by Jacopo Bassano, intended for El Escorial.

Falomir, who discusses this, supposes that the ambassador followed

up with further shipments, and that his successors continued to do

the same.15 An instance of acquisition possibly for private use is

provided by Juan de Tasis y Peralta, 2nd Count of Villamediana, who

was in Italy from 1611 to 1615, and spent 20,000 escudos in Rome

(1 escudo = 400 maravedis = 11.7 reales, or somewhat

more than a ducat) and another 10,000 (= 117,300 reales) in

Venice.16

(2) Not all Spanish collectors bought directly in Italy; many

acquired through intermediaries who were there. Example: the 5th

Duke of Infantado (died 1601); his 349 paintings at death included15 Miguel Falomir, Los Bassano en la España del siglio de oro, Salamanca, Museo Nacional Del Prado, 2001, pp. 177-179. Falomir reminds us that the Bassano workshop was orientated towards exporting and produced large numbers of paintings that found their way to Spain. Some 40 Bassanos are in the Prado alone.16 Falomir, “Artists’ Responses,” cit., p. 131.

20

many from Rome, among them 30 of hermits sent him by the Duke of

Feria and other paintings provided by the Cardinal Mendoza.17

(3) Some Italian paintings reached the Spanish court as

gifts. Falomir suggests that many of the Bassano originals that

ended up in Spain came via Florence. One Florentine channel

originated with Ferdinand I (Ferdinando de Medici, 1549-1609); he

regularly sent gifts of paintings to the Spanish court, including,

in 1590, “the twelve months” by Francesco Bassano.18 It is probable

that official couriers were employed to accompany such paintings

from Italy. The Medici gifts were not unique; the Dukes of Urbino

and of Mantua also sent gifts of paintings.19

(4) The considerable flow of Bassanos to Spain was augmented

by lively copying there. The

same applies to paintings by other Italian artists. And at the

forefront of this copying were transplanted Italian artists. Among

such artists were the court painters Bartholomé Carducho and

Angelo Nardi (1584-1665). Another, not attached to the court, was

17 Falomir, ib. p. 134; details of the inventory are given in Marcus R. Burke andPeter Cherry, Collections of Paintings in Madrid, 1601-1755. Documents for the History of Collecting: Spanish Inventories 1, Maria L. Gilbert ed., Los Angeles, The J. Paul Getty Foundation, 1997, pp. 199-203.18 Falomir, Los Bassano, cit., p. 180. For Medici gifts see E.L. Goldberg, “Artistic relations between the Medici and the Spanish Courts, 1587-1621. Parts I and II,” The Burlington Magazine, 138 (1996), pp. 111-114 and 529-540. 19 Falomir, “Value of Painting,” cit., p. 242, n. 53. As to couriers, a consignment from Mantua in 1603 was delivered by Rubens: see John. H. Elliott, “Royal Patronage and Collecting in Seventeenth-Century Spain,” in Economia e Arte, cit., pp. 551-565, at p. 557.

21

Antonio Ricci (c.1560-1632), from Ancona, who moved to Spain with

Federico Zuccaro. He set up a workshop in Madrid as early

as 1582.20

(5) Certain of the Italian artists who removed to Spain

engaged in dealing. Perhaps the prime example here is Carducho,

who traded in paintings by Pietro Sorri in Florence, but also

works by the contemporary Florentines Passignano (Sorri’s teacher)

and Pagani, and possibly some older masters as well.21 The Carducho

model was emulated by the Milanese sculptor Pompeo Leoni (1530-

1608), by Ricci and, under the prodigious collector Philip IV

(1602-1665), by Giovanni Battista Crescenzi (1577-1635), all four

transplanted Italians.22

Spanish collectors bought paintings of all sizes and quality,

and for prices that ranged widely. As to sizes, paintings could

range from very small to standard “larger” size, plus select works

of very large dimensions. Prices, as we have seen (note 9), ranged

from 4 reales to 14-16 for the small and “larger” standard-size

works, respectively, but could be up to several hundred reales.

20 See Falomir, Los Bassano, cit., pp. 180-181; Falomir, “Artists’ Responses,” cit., pp. 131, 133; and Burke and Cherry, Collections, cit., p. 33 n. 231. On Nardisee Pérez Sanchez, Borgianni, Cavarozzi y Nardi en España, Madrid, C.S.I.C, 1964. We owe this reference to Miguel Falomir.21 Burke and Cherry, Collections, cit., p. 5, citing Pérez Sanchez, Pintura italiana del siglio XVII en España, Madrid, Fundación Valdecilla-Universidad de Madrid, 1965. 22 Falomir, “Artists’ Responses”, cit., p. 133. On Philip IV as collector see Brown, Princes & Connoisseurs, cit.

22

Copies abounded, both imported and made in Spain. Italian artists

exported to Spain, but many also settled in Spain, temporarily or,

in key instances, permanently, either as court painters or in

business for themselves. Mechanisms of exchange involving Italians

and Italian paintings encompassed commission and gift, as well as

direct private purchase, or purchase through an agent, and through

artist-dealers in Spain. Cities of purchase or shipment in Italy

in our instances include Naples, Rome, Venice, Florence, Urbino,

and Mantua.

How large was the trade from Italy to Spain?

One indication as to the volume of this trade is the number

of paintings attributed to Italian painters in private collections

in Spain. The Getty Provenance Index database of such paintings,

1601-1773, currently contains 18,452 records. Of this number 2,890

works are attributed to known artists, 1,271 of them, or 44

percent, Italian.23 In the subgroup of Madrid inventories assembled 23 This and related information kindly provided by Maria Gilbert. The numbers given differ from those in Burke and Cherry, Collections, cit., p. 6, note 37. One significant difference is that the footnote included the collections formed in Italy of Gaspar de Haro, Marqués del Carpio, who was successively Ambassador to Rome (1674-1682) and Viceroy of Naples (1682-1687): see Burke and Cherry, ib., pp. 726-786 and 815-829 for inventories taken in Rome, 1682-1683 and Naples, 1687-1688, respectively. Gilbert’s current counts refer strictly to Italian paintings in Spain, attributed to known artists. Not counting Gaspar de Haro’s paintings, but imposing a 0.75 attributions rate on 200 unspecified paintings hesent to Madrid (Burke and Cherry, ib., p. 815) reduces to about 57% the overall percentage of Italian attributions for paintings in Spain for the period 1651-1700. Our figure of 63% in the illustrative table of note 26 represents a

23

by Burke and Cherry in the mid-1990s, which accounts for almost

all of the attributions to Italian artists in the Getty database,

somewhat more than 70 percent of the Italian paintings attributed

to a known Italian artist appear in inventories from the period

1651-1700. This concentration makes it problematic to apply a

constant rate of loss across generations, as has been done for the

Dutch Republic (see appendix). Nonetheless, in the illustrative

exercise below (note 26), we have imposed the constant 20 percent

loss rate mentioned earlier.24 We have also assumed 1,500 paintings

sent in the initial period 1571-1600. This number, as well as

those for paintings newly shipped in each twenty-year period

thereafter, is invented, though not wholly arbitrary. Very

broadly, we have constructed the table to capture something like

the percentage of Italian paintings among attributed works in

Madrid inventories dating from the second half of the seventeenth

century: our number is 63 per cent, for the period 1641-1700. In

addition, we have tried to end with a number for surviving

compromise between the percentages with and without the Marqués del Carpio’s paintings.24 The rate of loss used in the main Dutch study (see Appendix) is 50 percent across generations, or roughly 90 percent over a century including four generational changes (100→50→25→12.5→6.25). Our much lower assumed rate of loss reflects two considerations. First, the drier conditions in Spain must have favored physical survival. Second, the Italian paintings that reached and remained in Spain probably were, on average, more precious than the average Netherlandish painting there, and were primarily collected by prominent nobles and valued for their artistic properties. During the seventeenth century, moreover, the most valuable of them were added to the mayorazgo or family patrimony, which secured them from resale (information from Miguel Falomir).

24

paintings in the last twenty-year period, 1681-1700, not too far

off the number of Italian paintings in private collectons in Spain

in the Getty database: 1,271. Our end-number (bottom right, table

in note 26) is in fact about a third higher, and that for a

shorter period than covered by the Getty database. To close that

gap we invoke the possibility of losses between 1700 and 1773, the

end date of the Getty database, and we postulate that there were

inventories containing paintings but which did not survive, or are

not known, and which therefore have not entered the Getty

records.25 In any case, the purpose of our exercise is not to

produce a point-accurate estimate of total shipments, but one that

appears to be of the right order of magnitude, given what is known

of mechanisms for exporting in Italy and the southern Netherlands,

on the one hand, and the relation between these and known numbers

of paintings exported from Mechelen and Antwerp to Spain, on the

other. We reach a total number for Italian paintings shipped to

Spain – the sum of the numbers on the diagonal in our table – of

3,500, or 27 per year.26

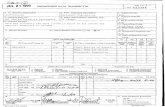

25 Miguel Falomir warns that the Getty total may be somewhat inflated because of paintings that passed from collector to collector through the regular estate auctions and appear in more than one inventory. 26 Here is an illustrative exercise, based on one possible combination of assumptions, to generate a figure for imports of Italian paintings to Spain. 1571-1600 1601-20 1621-40 1641-60 1661-80 1681-1700____________________________________________________________________

25

We stress that this number is no more reliable than the

assumptions on which it is based. It also requires one obvious

adjustment. As indicate above, the Getty databases cover paintings

held in private Spanish collections; as well as allowing, as we

have, for inventories that did not survive or are not known, we

need to add in paintings in the Royal Collection. We have taken

1700 as end-point. It is not known precisely how many Italian

paintings were in the Royal Collection at that time, but it is

thought to have been close to 1,000.27 By way of partial

substantiation, it is known that in 1688, in the Alcazar (former

royal palace) alone, there were 338 eligible paintings: 262

attributed to Italian masters, plus 39 to Italian imitators and 37

to the Spanish artist Ribera, who spent his working life in

Naples. The Alcazar was just one of twelve places where royal

1,500* 1,200 960 768 614 492 500* 400 320 256 205 500* 400 320 256 500*400 320 250* 200 250*Totals: 1,500 1,700 1,860 1,988 1,840 1,723____________________________________________________________________* New shipments. Totals include new shipments for the period plus surviving paintings from earlier shipments. 27 This estimate and the related information kindly supplied by Miguel Falomir. See also Brown, Kings and Connoisseurs, cit., Chapter III.

26

paintings hung. If we take the grand total to have been 1,000,

acquired over 130 years, 1570-1700, the annual

average is approximately 8. This raises our estimate of annual

average imports from Italy to 35.28

That number may still seem small, especially in the light of

known shipments of pinturas ordinarias. However, probably the bulk of

exports of that kind during our period were intended for the

Americas trade,29 most of which paintings would not have ended up

in Spanish inventories, our point of reference here. Again, if the

number 27 – the private component of our estimate – seems

inappropriately low, one could instead derive a range that

included 27 at its lower end, simply by imposing a higher loss

rate and compensating with higher assumed shipments.

Unfortunately, too little is known at present to anchor any set of

assumptions very firmly in facts.

For what it is worth, the number 27 – or the larger one 35 –

can be compared with the

28 It is worth bearing in mind that many Italian paintings acquired by the Spanish Hapsburgs were not expressly exported from Italy to Spain but came into the Royal Collection indirectly. We have not tried to adjust for this.29 This would not have been true before the mid-sixteenth century, when small religious images from Italy, most of them “alla greca”, arrived in large numbersfor domestic consumption (information from Miguel Falomir). This is in line withthe mention below (note 43) of 700 icons of the Madonna commissioned in Candia –then Venetian – in 1499, 200 of them “in forma alla greca”.

27

information available on exports from Antwerp to Spain and

Portugal combined. Filip Vermeylen has extracted from the export

tax registers for Antwerp for a two-year period, 1543-1545, and,

for the single year 1553, the number of shipments of paintings and

their value.30 The total value rose from 1,012 guilders to 17,543

guilders, a rise that reflects population growth and, more

particularly, a sharp rise in the numbers of painters (from an

average of 130 in the earlier period to maybe 150 in 1553, on its

way to a peak of perhaps180 in the mid- to late-1550s.)31 Rents

collected from artists and dealers selling paintings at the beurs

pand in Antwerp display roughly comparable increases over this

period.32 For four shipments in 1553 for which individual paintings

were valued, the average price was 39 guilders apiece.33 If this

were the overall average, there would have been 450 paintings

exported to Spain and Portugal in that year. That is a one-year

total that is almost certainly well above those prevailing later

in the sixteenth century and for much of the seventeenth century.

30 Vermeylen, “The Commercialization of Art: Painting and Sculpture in Sixteenth-Century Antwerp,” cit., and “Further Comments on Methodology,” in Early Netherlandish Painting at the Crossroads. A Critical Look at Current Methodologies, Maryan W. Ainsworth ed., New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2001, pp. 46-61 and 66-69, esp. pp. 50 and 68.31 Preliminary calculations by De Marchi, based on annual registrations of new master painters to the St Luke’s guild. Raw numbers for the 15th century were generously made available by Filip Vermeylen, and for the 16th century by NatasjaPeeters and Maximiliaan Martens.32 Vermeylen, “Further Comments,” cit., p. 68.33 Our thanks to Filip Vermeylen for this information.

28

All indications are that the 1550s and 1560s were extraordinary

years for production and exports from Antwerp. A more balanced

picture emerges from later information.

The Antwerp merchant in textiles and diamonds Paul du Jon, in

1610-11 sent to Seville 5 cases and 1 chest of paintings

comprising 339 paintings in all. Eight of the 339 were valued

collectively at 300 reales (18.75 ducats).34 Most of the

paintings, however, were said to have been very small and

presumably were intended for the Americas rather than for

consumers in Seville.

The Antwerp merchant partnership of Chrisostomo Van Immerseel

and Marie de Formestraux, much more specialized in paintings, to

our knowledge shipped 47 cases of paintings to Spain between 1622

and 1646. Seven of these shipments averaged 161 paintings. If that

average applied to all 47 shipments, the couple would have sent

from Antwerp to Spain at least 7,567 paintings. In four shipments

examined in detail the individual paintings averaged 6.55 guilders

apiece (about 1.17 ducats or 12.9 reales).35 In other words, Van

Immerseel and de Fourmestraux shipped paintings worth considerably34 Eddy Stols, De Spaanse Brabanters of de Handelsbetrekkingen der Zuidelijke Nederlanden met de Iberische Wereld, 1598-1648, 2 vols, Ledeberg/Ghent, Erasmus, 1971, vol. 2, p. 200. 35Neil De Marchi and Hans J. Van Miegroet, “Exploring Markets for Paintings in Spain and Nueva España,” in Kunst voor de markt/art for the market, 1500-1700, Reindert Falkenburg, Jan de Jong, Dulcia Meijers, Bart Ramakerrs and Mariët Westerman eds., Netherlands Yearbook for History of Art 1999, vol. 50, Zwolle, Wanders, 2000, pp. 81-111.

29

more than the cheapest serial copper plates at 4 reales or so

apiece but somewhat less than the many made by Carducho at 14-16

reales. This dealership, over a 25-year period, sent an average of

303 paintings per year. This too is much greater than our estimate

of 35 paintings a year shipped from Italy, but most of the Van

Immerseel-de Fourmestraux paintings were meant for America and

that flow may not be compared with our estimate of 35 per year

from Italy for retention in Spain.36

Turning to the second half of the seventeenth century, when

the Americas trade in general was in sustained decline, we find

another Antwerp husband-wife partnership, that of Matthijs Musson

and Maria Fourmenois, quasi-specialist dealers in paintings,

shipping, to our knowledge, some 730 paintings to Cadiz in the

years 1650-1668.37 This translates into 40.6 paintings a year. 36 There were also large numbers of Flemish paintings sent to and retained in Spain. However, these are known primarily from Antwerp export documents. Unlike Italian paintings, they were acquired by ordinary people and Churchmen as well as nobles, and are to be found everywhere in Spain, not only in Madrid, whence come almost all the known private inventories of paintings. Since most of the surviving inventories are those of noble or at least wealthy and prominent families it is not surprising that attributions to Flemish artists in the Getty database of paintings in private collections in Spain are fewer than to Italian:22 percent compared with 44.37 The number is culled from a set of documents published originally by J. Denucé, Na Peter Pauwel Rubens. Documenten uit den kunsthandel te Antwerpen in de XVIIe eeuw van Matthijs Musson, Antwerp, De Sikkel, 1949. The dating and transcriptions in this collection are not always certain. A more reliable edition of many of the same documents is by E. Duverger, Nieuwe gegevens betreffende de kunsthandel van Matthijs Musson en Maria Fourmenois te Antwerpen tussen 1633 en 1681, reprinted from Gentse Bijdragen tot de Kunst Geschiedenis en de Oudheidkunde, XXI (1969). The overlap between these two sources, however, is not complete, and it is difficult to be sure that there is no double counting in our total. It is likely that neither source covers the complete record of the Musson-Fourmenois business.

30

Again, this may not be compared directly with our estimate of 35

per year from Italy, though the c. 645 paintings the partners also

sent to other cities in Spain in the period 1657-1677 may be, and

that amounts to 32 per year. So, if our estimate of 35 per year

from Italy is of the right order of magnitude, a mid-seventeenth

century Antwerp dealership single-handedly supplied almost as many

paintings to Spain.

The Musson-Fourmenois partnership drew on upwards of 45

painters in each decade of the

period 1650-1670, though nowhere near that number for their

Spanish trade alone. Along with other known numbers of paintings

the partners exported – Paris received from them about the same

number as Cadiz – this too attests to the scale on which Antwerp

traders in paintings operated.

Were the mechanisms for exporting paintings comparable between Italy and the North?

The Van Immerseel-de Fourmestraux and Musson-Fourmenois

partnerships provide us with complementary models for trading

internationally in paintings. Van Immerseel moved back and forth

between Seville and Antwerp, where he ordered or bought ready-made

paintings direct from various artists, while his wife stayed in

Seville and saw to the business at that end, including final sale

31

or transshipment for America. For their exports to “the Indies”

the pair depended on shippers and captains but a far as we know

did not otherwise employ agents.

Musson and Fourmenois scarcely moved; their base was Antwerp,

where basically they filled orders for paintings from others who

in turn sold them in Spain or shipped them on to America.

Sometimes they sold in Antwerp to a business relation who normally

resided in Spain; in such instances they received payment on the

spot. They also shipped to associates or agents in Spain,

expecting to be paid by bill of exchange following eventual sale.

This, of course, involved accepting delays and the inevitable

exchange risk, not to mention having to trust their agents. They

limited their risks, however, by not shipping to America.

As indicated earlier, both couples used their own capital.

Van Immerseel and de Fourmestraux sometimes had to borrow small

amounts, while Musson and Fourmenois enlarged their capital by

going shares in shipments with co-principals in Antwerp or at the

other end. It is not clear that they were more risk-averse than

Van Immerseel and de Fourmestraux, though they assigned risks

differently.

All these elements are common to early modern distance trade,

wherever it originated. What we wish to emphasize therefore are

32

three characteristics that seem to be differentiating. First, as

noted, both our Antwerp firms were quasi-specialized in paintings.

Musson and Fourmenois shipped escritorios and small cabinets,

mirrors and frames, as well as paintings; Van Immerseel and de

Fourmestraux shipped textiles, gloves, and lace as well as

paintings. But for both firms paintings (along with hand-painted

prints) comprised their principal export; they were not a

sideline. Second, both firms survived as merchants in paintings

for extended periods: Musson-Fourmenois following their marriage

for about thirty years, Van Immerseel and de Fourmestraux for

roughly twenty-five. Third, these firms were vertically

integrated. We have noted these characteristics before, when

discussing the low-end traffic in paintings; but by the

seventeenth centuryit is clear that some Flemish merchant-dealers

were shipping not only cheap paintings in bulk but also better

quality pictures.

As noted above, our question at this point thus becomes: were

there comparable firms in Italy, equally specialised and similarly

vertically integrated, and engaged in the export of paintings and

exporting on a regular basis ove a sustained period? Or, since we

will concentrate on Venice, there?

33

Exports and imports of paintings: the case of Venice

Venice of course was a major entrepôt in our period. Many

imported goods were promtly re-

expored, but raw materials were also transformed on the spot into

a wide variety of items for which the city was renowned, including

soap, printed books, pigments, glass, dyed silks and velvets.38

These locally manufactured products, as well as imported luxury

goods, were offered for sale in the city’s famed retail emporia,

but, since they were also exported widely Venice, not

surprisingly, also possessed much of the Northern infrastructure

and regulatory environment needed to facilitate international

trade. It had warehousing, shipping, financing and insurance

capabilities. There were also Venetian trading outposts abroad,

hence factors. As to facilities to promote paintings exports,

however, there were none: no Exchange (borsa) where foreign

merchants could view displays of local paintings, and no annual

fair comparable to Antwerp’s two, which were longer and where

cheap works were as prominent as those of high quality and price.

38 Ugo Tucci, “Venezia nel Cinquecento: Una città industriale?” in Crisi e rinnovamento nell’autunno del Rinascimento a Venezia, V. Branca and C. Ossola, eds., Florence, Olschki, 1991, pp. 61-83; Luca Molà, “Le vie delle spezie e della seta. Il commercio d’esportazione dale Venezie tra XIV e XVI secolo” in L’Europa e le Venezie, G. Barbieri ed., Cittadella, Biblos, 1997; Eliyahu Ashtor, Levant Trade in the Later Middle Ages, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1983.

34

Paintings produced by Venetian artists were in demand

throughout Europe. Since, however, so much of what is known about

paintings concerns high-end pictures by famous painters, our

challenge is both to determine whether Venice was a net exporter

of paintings, and to widen the investigation to cover the cheaper,

often non-commissioned, and sometimes serially-produced pictures

that almost certainly were being made in the city. Research along

those lines, unfortunately, is only just beginning, especially for

the period before 1550, and so far has been hampered by a paucity

of documents.39

What can be said in terms of desired parameters? Can we, for

example, determine the ratio of artists to population? A

transcription exists of the list of members in 1530 of the

Venetian guild to which painters belonged.40 However, in only 77 of

230 cases is a craft specified. Matthew is working to increase the

number for which a craft is known. The aim is to determine who

were the “easel” painters as distinct from painters of furniture,

cards, fans, and so on. The three crafts most closely linked to

easel paintings were those of figure painter, miniaturist and 39 Isabella Cecchini frequently notes the limitations of the documentary record even for the period post-1550. Cecchini, Quadri e commercio, cit. For one beginning, however, see Louisa Matthew, “Were there open markets for pictures inRenaissance Venice?” in The Art Market in Italy 15th-17th Centuries, M. Fantoni, L.C. Matthew, S.F. Matthews-Grieco, eds., Modena, Panini, 2003, pp. 263-261.40 The transcript is reproduced in Elena Favaro, L’Arte dei pittori in Venezia e i suoi statuti,Florence, Olschki, 1975.

35

gilder. Work to date points to there having been a significant

number of easel painters thus defined, though perhaps fewer than

painters of furniture, etc.

The 1530 list records the names of very few foreign artists.

Guild protests, however, point to unregistered foreigners as a

problem. One complaint was made in 1479. Another, in 1513,

resulted in a modified regulation requiring Venetian masters

henceforth to register foreign masters whom they employed for more

than three days or face a stiff fine.41Additional names of foreign

painters are in fact coming to light, culled from tax records,

which often state who was renting shops and residences, from

records of property ownership, from death entries, and from the

enrollment lists of confraternities. Still more names might emerge

from the close study of Venetian household inventories, which

exist in large numbers from the 1530s through the seventeenth

century. Up till now, however, the same quantitative analysis has

not been applied to Venetian inventories as to those of the Low

Countries.42

41 Favaro, L’Arte, cit., pp. 58-59, 70. See also Matthew, “Working Abroad: NorthernArtists in the Venentian Ambient,” in Bernard Aikema and Beverly Louise Brown eds., Renaissance Venice and the North. Crosscurrents in the Time of Bellini, Dürer and Titian, Cinisello Balsamo (Milan), Bompiani, 1999, pp. 61-69.42 The richest source for inventories from sixteenth-century Venice is the fondoat the Archivio di Stato in Venice entitled Miscellanea Notai Diversi. For more on household inventories see Patricia F. Brown, Private Lives in Renaissance Venice, New Haven and London, Yale University Press, 2004.

36

Returning to the ratio of painters to population, of the 77

guild members whose craft was specified in the 1530 list, 37 of

them, or 48 percent, were easel painters (by the definition

above). If the same ratio applied to all 230 members, there would

have been 110 easel painters in 1530. This translates into 0.8

painters per thousand residents. That is about the same as for

Amsterdam c.1630, a city, recall, known to have been a net

importer of paintings. However, the ratio for Venice probably

undercounts foreign artists working there, and it ignores

altogether artists in Venetian territories such as Crete. If just

15-20 foreign easel painters were working in Venice at the time it

would raise the ratio to about 1.0; and it would rise considerably

above 1.0 if the painters of Candia (the future Heraklion) on

Crete, were included.

Under Venetian control since 1203, Candia became an important

center for icon production after the fall of Constantinople in

1453. The city had 120 painters in a population of 15,000 during

the second half of the fifteenth century – an extraordinarily high

ratio of 8 artists per 1,000. There is a document involving two

merchants who in 1499 commissioned a large number of icons in

Candia, presumably destined for foreign markets.43 Such goods would

43 Nano Chatzidakis, Da Candia a Venezia. Icone Greche in Italia, XV-XVI Secolo, Athens, Fondazione per la cultura greca, 1993, pp. 1-3. Chatzidakis notes details of the

37

have first passed through Venice and might have been dutiable.

However that may be, Candian icons were judged in Venice to be of

high quality,44 and it seems appropriate to count them and their

makers as domestic.

Allowing the count for Venice to include both foreign easel

painters and those from Candia, the artist to population ratio in

the late-fifteenth and early sixteenth-century (including the

population of Crete) was considerably in excess of 1.0. Later,

however, this probably was not the case. In the early 1640s, tax

records for the so-called “imperceptible” naval contribution

required of guilds and levied on members in proportion to their

income – the tansa insensibile – show an average of 108 registered pittori

plus gilders and miniaturists, out of a population of around

120,000. Later still, there are separate tax records for pittori

alone. A three-year average for 1684-1686, shortly after the

painters had separated off from the larger guild to form their own

college, indicates that there were 136 painters (including some

artist-dealers), in a total population of perhaps 140,000.45 The

narrow measure of the ratio of artists to population thus appears

1499 contract: two merchants, one identified as Italian, who was likely to have been a Venetian, and one from the Peloponnese, contracted with three Candian painters to produce icons of the Madonna, 500 “in forma alla Latina” and 200 “informa alla greca,” all to be completed within 45 days.44 Favaro, L’Arte, cit., p. 75.45 Tax lists, 1640 through 1644, with craft of guild members specified, from Favaro, ib., pp. 163-194, and for the Collegio, 1684-1686, ib., pp. 195-211.

38

to have remained stable at between 0.8 and 1.0 though, as noted,

if allowance is made for foreigners and, in the earlier years for

Candian artists, it was above 1.0 in the late fifteenth and early

sixteeth centuries.

We turn now to direct evidence on exports of paintings from

Venice over and above the Candian

contract of 1499 and the Morinoni shipment of 1647. Additional

documentation is thin. We will

therefore speculate a little as to whether these fragments are

just the fortuitous surviving indications of a larger underlying

trade. We will also include bits of information relating to other

places.

Guild regulations in Venice mention work intended for export

as early as the 1280s, and rules allowing painters to work on

feast days if they were producing items for export were

reconfirmed as late as the sixteenth century.46 Types of work are

rarely defined, though ancone are mentioned – for instance a

regulation of 1322 allowed non-members of the guild to sell

painted ancone only during the feast of the Sensa, and another rule

in the same year, reconfirmed in 1409, stated that ancone were only

46 Favaro, L’Arte, cit., pp. 25 and 75-76. The rules ratified in 1537 and 1542 mention only extending the permission to the painters of boxes (casseleri).

39

to be sold from a master’s workshop.47 The term ancona is often

taken to mean an altarpiece painted on wood, but the regulations

of 1457 also mention large and small ancone, and it is very likely

that devotional pictures were comprehended. Imports of paintings,

as everywhere, were restricted, although exceptions were made, as

in the mid-fifteenth century when a permission was granted to

allow in ancone de extra Culphum, which probably meant icons from

Crete.48

Can more be made of the 1499 contract for icons from Candia?

No doubt these were for export, but unfortunately we do not know

the intended destination(s), nor whether this was a sporadic

occurrence or part of a regular trade. It seems likely that there

was substantial, sustained production of images of the Madonna and

Child, both in Candia and in Venice, though the only evidence for

it is (a) that such paintings survive, (b) that motifs and copies

related to this sort of image were used in well-known Venetian

workshops, and (c) that many such paintings are recorded in

sixteenth-century Venetian inventories; these include a number of

Madonnas described as “alla greca”.49 Was there also an export 47 Favaro, ib., pp. 28 and 72.48 Favaro, ib., p.75. Presumably here permission had been sought to sell in Venice, as distinct from shipping to Venice for transshipment to other destinations, for which no permission would have been required. 49 Matthew, “The Painter’s Presence: Signatures in Venetian Renaissance Pictures,” The Art Bulletin LXXX (1998), p. 645, n. 54 gives references on the situation in Venice. Chatzidakis notes that there were “quite a few” icons in

40

trade in such images? Yes, if we accept the traces of icons “alla

greca” that reached Spain. Yes, too, if it is implausible that 700

such images, “alla Latina” and well as “alla greca”, as called for

in the 1499 contract, could be needed in a single year for the

Venetian market alone.

Another source of small, serially-made images, frequently

Marian in subject matter, in the second half of the fifteenth

century, was Florence. These images included free-standing

pictures as well as painted tabernacles. They used relatively

cheap materials, were derived from paintings by famous

Florentines, such as Fra Filippo Lippi and Francesco Cesellino,

and came in standard sizes.50 A wide variety in appearance and in

cost was available, and this sort of business helped some

churches in Venice and that their numbers increased after the Greek community was established there in 1498. He also notes that there was a demand for these pictures “all around the Eastern Mediterranean and the Adriatic”. Da Candia, cit., pp. 18-21. Lorenzo Lotto painted two small pictures for a Greek Orthodox patron in Ancona “in the Greek manner”, for which see Floriano Grimaldi and KatySordi, Lorenzo Lotto 1480-1556 Libro di Spese Diverse, Loreto, Delegazione Pontificia per il Santuario della Santa casa di Loreto, 2003, ff.136v-137, pp. 192-193.50 Megan Holmes, “Copying Practices and Marketing Strategies in a Fifteenth-Century Florentine Painter’s Workshop” in Artistic Exchange and Cultural Translation in the Italian Renaissance City, S.J. Campbell and S.J. Milner eds., Cambridge and New York, Cambridge University Press, 2004, pp. 38-74. See also Megan Holmes, “Neri di Bicci and the Commodification of Artistic Values in Florentine Painting (1450-1500),” and Rita Commanducci, “Produzione seriele e mercato dell’arte a Firenze tra Quattro e Cinquecento,” both in Fantoni, Matthew and Matthews-Grieco eds., The Art Market in Italy, cit., pp. 213-23 and 105-113. At least one scholar has begun to consider the evidence for such activity in Siena during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries: see Gaudenz Freuler, “The Production and Trade of Late Gothic Pictures of the Madonna in Tuscany,” in Italian Panel Painting of the Duecento and Trecento, V.M. Schmidt ed., Washington, National Gallery of Art, 2002, pp. 427-440.

41

painters, such as Neri di Bicci, to become very successful.51

Neri’s account books reveal that some products of this type were

sent by merchants to Rome, but there is not enough evidence to

reveal whether or not this was a regular component of his

business.

Some fifteenth-century Roman customs documents indicate that

large numbers of cheap images of the Madonna were being imported

into that city, but this evidence too is fragmentary.52 It seems

reasonable to speculate that the demand for small, inexpensive

religious images would have been particularly strong in pilgrimage

centers such as Rome and Loreto, and indeed this demand and the

response of merchants and artists may have spawned fifteenth-

century enterprises such as those described above. It is likely

too that enterprising individuals used newly available

reproductive technology to produce and market both single leaf

prints and books thereof, though it is difficult to document the

history of the strictly reproductive print and best estimates put

it no earlier than

1530, in Rome, which quickly became the home of “postcards”.53

51 Neri di Bicci, Le Ricordanze 1453-1475, B. Santi ed., Pisa, Marlin, 1976; Anabel Thomas, The Painter’s Practice in Renaissance Tuscany, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1995; Michelangelo Muraro, Il libro secondo di Francesco e Jacopo dal Ponte, Bassano del Grappa, Verci, 1992. See also note 37. 52 The Roman customs document is cited in Thomas, The Painter’s Practice, cit., p. 290.53 See the careful discussion in David Landau and Peter Parshall, The Renaissance print, 1470-1550, New Haven and London, Yale University Press, 1994, pp. 162-168.

42

Aside from small devotional images it is known that Venetian

painters shipped works of art to foreign destinations in the

fifteenth century, though documents invariably deal only with

large works, usually altarpieces, produced on commission. Shipping

arrangements are sometimes spelled out in the written contracts

for these relatively expensive works, but destinations may also be

inferred from the places where Venetian works are still to be

found. Altarpieces by Carpaccio, the Vivarini family, Giovanni

Bellini, Lorenzo Lotto, and Titian are known in Istria and Ragusa

along the eastern coast of the Adriatic, in Ancona and the

Marches, and in towns along the coast of Apulia on the Italian

Adriatic coast, during the later fifteenth and early sixteenth

century. Many such shipments are known, even if they involved only

single works of art.54

In adddition to contracts and shipping documents, known

sources include a Venetian document of 1524 that lists export and

import tariffs. This document mentions altarpieces (“pale

d’altar”), painted canvasses (“tele depente”) and paintings on

panel (“quadri di legno”), in addition to sculptures made of

marble, wood, gesso and clay.55 It is unclear whether the 54 Peter Humfrey, The Altarpiece in Renaissance Venice, New Haven and London, Yale University Press, 1993, provides an overview of this activity.55 This document, from A. Morosini, Tarifa del pagamento di tutti i dacii di Venetia, 1524, is cited, in slightly differing form, in Cecchini, Quadri e commercio, cit., p. 210 and by Michel Hochmann, Peintres et commanditaires a Venise, 1540-1628, Rome, Ecole

43

government was deriving income from the export and/or import of

these works of art. Lorenzo Lotto, whose account book between 1538

and 1556 provides us with the only concrete information we have

about the daily operation of a Venetian painter’s workshop during

the first half of the sixteenth century, sporadically sent small

works to be sold in Rome, Loreto, and Messina.56 In 1549, for

instance, he sent an unknown number of little images depicting the

miraculous transfer of the Holy House of the Virgin to Loreto to a

merchant in that city.57 That we possess mentions of paintings

being sent to these places is understandable, since they lay on

the routes normally traveled by the merchants andartisans who

acted as agents for the painters during this period and, in some

cases, for patrons

desirous of obtaining a work by a Venetian painter.58

Lotto’s marketing activities on his own behalf are a further

reminder that painters in Venice and surrrounds – recall the

Bassano family enterprise in Bassano del Grappa – played an active

française de Rome, 1992, p. 75 citing M.A. Muraro, “Studiosi, collezionisti e opere d’arte veneta dalle lettere al Cardinale Leopoldo de’ Medici”, Saggi e memorie di storia dell’arte, vol. 4, 1965, p. 68.56 Louisa Matthew, “Painters Marketing Paintings in Fifteenth and Sixteenth-Century Florence and Venice,” in De Marchi and Van Miegroet eds., Mapping Markets,cit., pp. 312-313 (p. 321 for Loreto and Rome). 57 Grimaldi and Sordi, Lorenzo Lotto. 1480-155. Libro di Spese Diverse, cit., f. 15v, p. 14. 58 Ashtor, Levant Trade and Ugo Tucci, “Traffici e navi nel Mediterrraneo in età moderna” in La Peninsola Italiana e il mare. Costruzioni, navali, trasporti e commerci tra XV e XX secolo,T. Fanfani ed., Naples, Edizione scientifiche italiane, 1993, pp. 52-70.

44

role in promoting their own business, even on the international

stage, a role that Venetian painters would continue to play

throughout the entire period we are considering. Merchants also

acted as agents in foreign transactions involving altarpieces and,

judging by the few instances we know of from the period before

1550, even in the shipping and sale of less expensive pictures.59

This too is unsurprising, since merchants were the quintessential

travelers of Renaissance society, while they seem to have taken on

extra tasks quite readily on behalf of family or community

institutions.60 It was also easy for a traveling merchant to accept

additional merchandise to be sold at his destination for a share

in the profits. This arrangement, the commenda, was retained in

Venice from a medieval Eastern trading tradition that persisted

into the Renaissance and according to which a merchant (or

occasionally a ship’s captain), received merchandise, to be

shipped at the risk of the creditor, for one quarter of the

eventual profit.61

59 For painters in fifteenth century Florence see Thomas, The Painter’s Practice, cit.,pp. 201-204 and Suzanne Kuberski-Piredda, “Immagini devozionali nel Rinascimento fiorentino: produzione, commercio, prezzi” in Fantoni, Matthew and Matthews-Grieco eds., The Art Market in Italy, cit., pp. 116-118.60 Lorenzo Lotto’s account book provides a very explicit example from 1542. The painter was commissioned to make an altarpiece for a small community near Bari, and the contract was negotiated by a merchant acting on its behalf. Grimaldi andSordi, Lorenzo Lotto.1480-1556. Libro di Spese Diverse, cit., ff. 2v-3, pp. 8-9. 61 Ashtor, Levant Trade, cit., p. 379.

45

Italian merchants and bankers resident in foreign ports also

helped with the acquisition of, payment for and shipping of art.

In the fourteenth century, for example, the merchant of Prato,

Francesco Datini, had his agents abroad occasionally purchase and

ship paintings back to him. And Medici agents at the family’s

Bruges bank branch a hundred years later also shipped paintings on

linen to Florence for use in the family’s country residences. Of

142 paintings in the possession of the Medici in the inventory

taken on the death of Lorenzo the Magnificent in 1492, one-third

were Netherlandish, at least 20 of them, on linen, in the family’s

villa at Careggi. 62 Agents, family or friends abroad were employed

by numerous other Florentine families, including the Strozzi,

Portinari, Tani, Baroncelli, Pagagnotti, and Morelli, but the

62 Paula Nuttall, “’Panni Dipinti di Fiandra’: Netherlandish Painted Cloths in Fifteenth-Century Florence” in The Fabric of Images. European Paintings on Textile Support in theFourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries, C. Villiers, ed., London, Archetype Publications, 2000, pp. 109-117. The author speculates on p. 114 that such painted cloths may have been available in Pisa “on the open market,” but she provides no evidence. See also Nuttall, From Flanders to Florence. The Impact of Netherlandish Painting, 1400-1500, NewHaven and London, Yale University Press, 2004, pp. 106 and Appendix 1. An outstanding source for tracing Flemish paintings in Florence is Michael Rohlmann, “Flanders and Italy, Flanders and Florence. Early Netherlandish painting in Italy and its particular influence on Florentine art: an overview,” in Italy and the Low Countries – Artistic relations. The fifteenth century, Victor M. Schmidt, Gert Jan van der Sman, Marilena Vecchi and Jeanne van Waadenoijen, eds., Florence, Centro Di for the Istituto Universitario Olandese di Storia dell’Arte, Firenze, 1999. We might note that the collection of the Genovese collector Giovanni Agostino Balbi, at his death in 1621, comprised 154 paintings, of which 63 were Flemish: Richard Goldthwaite, “L’economia del collezionismo,” in Piero Boccardo,ed.., L’Eta di Rubens, Genoa-Milan, Skira, 2004, pp. 13-20 at p. 17. There must be more such examples, and a comparative study of all of those known would yield valuable insight into how they came to be acquired and whether they were shippedas one commodity among many by non-specialists or formed part of a specialized traffic.

46

paintings acquired travelled as occasional, additional cargo;

there is nothing to suggest that they were a regular item, much

less that certain Italian merchants specialised in paintings.63

Agents played comparable roles in facilitating the export of

paintings from Venice, though once again on an ad hoc basis. For

example, in the 1680s the pupil, business agent and occasional

dealer of Luca Giordano in Naples, Carlo della Torre, was

supplying paintings by Giordano to the Venetian merchant Simon

Giogali. Some of these Giogali forwarded to the elector of

Bavaria, using his agent in Munich, Bartolomeo Piazza, to manage

the deal and remit payment at that end.64

Returning to Northern paintings in Venice, there appear with

increasing frequency in household inventories from the sixteenth

century and later paintings described as “alla Fiandra”. Were

these copies made in Venice or originals imported from Flanders?

Evidence relating to Flemish imports exists from the fifteenth

century, though most of it is unequivocal only for works by well-