Hereditary Palmoplantar (Epidermolytic) Keratoderma: Illustration Through a Familial Report

Transcript of Hereditary Palmoplantar (Epidermolytic) Keratoderma: Illustration Through a Familial Report

323November • December 2004

H P P K : I l l u s t r a t i o n T h r o u g h a F a m i l i a l R e p o r t

Hereditary palmoplantar keratoderma, a well-known clinical entity, is illustrated through a familial report of an unmarried young man who is the product of a consanguineous marriage (paternal and maternal grandmothers were sis-ters). The lesions were characterized by immense yellow waxy thickening of the skin surrounded by erythematous border (halo) and fissures/cracks associated with extensive scaling of the palms and soles. The lesions were bilateral and symmetrical. These features were supported by orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis hypergranulosis and acanthosis in hematoxylin-eosin stained tissue sections pre-pared from the soles. Mycelia/spores could not be identified on Periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) reac-tion. An autosomal dominant trait was revealed through family pedigree. An abridged update to recap the current status is highlighted. (SKINmed. 2004;3:323–332) ©2004 Le Jacq Communications, Inc.

H ereditary palmoplantar keratodermas (HPPKs) are a group of heteroge-neous diseases unified/characterized

through consistently progressive, extraordi-nary thickening of the stratum corneum of the palms and soles with conspicuous pain-ful/discomforting fissures resulting in dis-ability.1 Ever since its initial clinical descrip-tion,2–4 the condition has established itself as an intriguing clinical entity. Accordingly, it has been the subject of detailed clinical studies supplemented by exploration of the genetic undertones on the limited clini-cal material available from time to time. Sporadic reports of its identification within a family—covering several generations—have

been the subject of periodic reports that enrich the existing literature. It is apparent from the information thus far available that HPPK is an entity that largely expresses itself as an autosomal dominant or (rarely) an autosomal recessive trait. A succinct review of the topic to define its current status and pinpoint, if possible, any vacuum is therefore warranted. The details of a case of familial HPPK are reported as an illustration.

Epidemiologic UndertonesEpidemiologic undertones are difficult to form because a population survey to scan for the condition has not been undertaken. Most of the available data are hospital based and may not precisely project the condition’s epidemiologic parameters. Nonetheless, it is imperative to take stock of the prevailing literature. A recent report from south India,5 where 31 cases of hereditary HPPK were found from among 59,490 persons attend-ing a preeminent dermatology clinic, states its prevalence as 5.2 per 10,000 population. At this clinic, HPPK was more frequently encountered in men than women (4.2:1). Its incidence was 67.7% in the younger age group (0–10 years). Unna-Thost syndrome (38.7%) was most frequent, followed by Greither’s disease (22.9%). Other uncommon variants—Vohwinkel (three patients) and idio-pathic punctate and ichthyosis vulgaris-asso-ciated palmoplantar keratodermas (PPKs) (two cases each) were also recorded.5 Furthermore, in a report from north Sweden,6 two differ-ent clinical and genetic types comprising

From the Dermato-Venereology (Skin/VD) Centre, Sehgal Nursing Home, Panchwati, Azadpur, Delhi, India;1 Department of Dermatology and Venereology, Lady Hardinge Medical College, New Delhi, India;2 Department of Pathology, Vallabhbhai Patel Chest Institute, University of Delhi, Dehli, India;3 Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Grant Medical College and Sir J. J. Group of Hospitals, Mumbai, India4

Address for correspondence: Virendra N. Sehgal, MD, A/6, Panchwati, Azadpur, Delhi -110 033, India E-mail: [email protected]

Hereditary Palmoplantar (Epidermolytic) Keratoderma: Illustration Through a Familial ReportVirendra N. Sehgal, MD;1 Kabir Sardana, MD;2 Sonal Sharma, MD;3 Dharmendra Raut, MBBS4

R e v i e w

www.lejacq.com ID: 3243

SKINmed: Dermatology for the Clinician (ISSN 1540-9740) is published bimonthly (Jan., March, May, July, Sept., Nov.) by Le Jacq Communications, Inc., Three Parklands Drive, Darien, CT 06820-3652. Copyright ©2004 by Le Jacq Communications, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. The opinions and ideas expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Editors or Publisher. For copies in excess of 25 or for commercial purposes, please contact Sarah Howell at [email protected] or 203.656.1711 x106.

324 November • December 2004

H P P K : I l l u s t r a t i o n T h r o u g h a F a m i l i a l R e p o r t

autosomal dominant and autosomal recessive traits of HPPK were studied. The clinical fea-tures of the former conformed to Unna-Thost, while the latter had features of diffuse PPKs of Gamborg Nielsen type. Family studies to support its probable recessive inheritance (i.e., a demographic mapping of the four fami-lies) were performed. It was shown that the families belonged to the same (index) family at different levels of generations; however, a common ancestor who connected these fami-lies was not found. Marital distance of het-erozygotes and birthplaces of probands were limited to an area that is generally known to harbor inherited disorders. According to a map of the origin of family members, it was shown that the major part originated from the same area and that the integration of family members had occurred in the same places. It was concluded that adoption of a demographic database for family studies in genetic research might contribute invaluable information about family relations.6

Subsequently, in 1967, the prevalence of the disease was found to be 0.55%. Fifteen years later, in 1982, it was possible to track half of the original propositi. It was possible to distin-guish a severe clinical form with a presumed recessive inheritance among these families. The details of clinical expression in relatives of the original propositi were outlined, and other associated diseases were pooled from other studies. Dermatophytosis was the common association. It was found in 36.2% of the cases, for a prevalence of 37.6%. Trichophyton menta-grophytes was the most frequent isolate; how-ever, Trichophyton rubrum7 and Epidermophyton floccosum8 were also incriminated. Blood group A, increased specific dermatophyte IgG antibodies, precipitating antibodies, and an immunological reaction in vitro to keratin was helpful in differentiating the distribution of dermatophytes. The quantity of keratin of the palms and soles was considered imperative for the affinity of dermatophytes. A vesicular eruption along the hyperkeratotic border and a mononuclear cell infiltrate were often report-ed and interpreted as immunologic reactions to dermatophytosis. Scaling and fissuring were considered their clinical signs rather than a part of the originally reported clinical picture, whereas their histopathology corresponded to previously reported descriptions of the Unna-Thost. The histopathologic features of the

latter were based on those of epidermolytic PPK. Accordingly, the existence of the Unna-Thost variety on the continent was challenged because epidermolytic PPK was not found in the county of Norrbotten, Sweden. Thus, “Diffuse HPPK-type Norrbotten” was pro-posed. Furthermore, the histopathology of the presumed recessive variety was similar to that of the dominant variety. Ultrastructural char-acteristics were handy to differentiate it from Mal de Meleda and the dominant variety.9

Histopathologic ConnotationLight microscopy of hematoxylin-eosin stained sections prepared from a represen-tative lesion is an essential ingredient of diagnosis. The histologic changes are largely nonspecific and/or confined primarily to the epidermis. The epidermal changes are in the form of prominent orthokeratosis and hyper-granulosis. The latter is studded with large, irregular keratohyalin granules. Large clear spaces in the cells of granular and upper spi-nous layers are other associated components. The clear areas of cytoplasm are filled with a fibrillar material and cellular organelles, abnormal clumps of tonofilaments, and kera-tohyalin granules.10–13 Electron microscopy is a useful adjunct to define the details of the features and might assist in differentiating clinical variants of HPPK. Histopathologic examination performed on 91 biopsies taken from the dominant form of HPPK revealed no case of epidermolytic PPK. This finding was in contrast to the results of a re-exami-nation of descendants of the original family published by Thost, whose members showed the characteristic features of epidermolytic PPK, and re-evaluation of biopsies from other families shows that it was the most frequent type. A dermoepidermal mononuclear cell infiltrate was considered typical of Unna-Thost PPK. Further, this cellular infiltrate was frequently recognized where there was simultaneous occurrence of HPPK and der-matophytosis. Relapsing, vesicular eruptions along the hyperkeratotic border were clini-cal signs of the severity of dermatophytosis. Spongiotic vesicles together with a mononu-clear cell infiltrate should be considered as a eczematous reaction to dermatophytosis.9,14

Clinical RepercussionsPPKs constitute a heterogeneous group of disorders characterized by thickening of the

SKINmed: Dermatology for the Clinician (ISSN 1540-9740) is published bimonthly (Jan., March, May, July, Sept., Nov.) by Le Jacq Communications, Inc., Three Parklands Drive, Darien, CT 06820-3652. Copyright ©2004 by Le Jacq Communications, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. The opinions and ideas expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Editors or Publisher. For copies in excess of 25 or for commercial purposes, please contact Sarah Howell at [email protected] or 203.656.1711 x106.

325November • December 2004

H P P K : I l l u s t r a t i o n T h r o u g h a F a m i l i a l R e p o r t

palms and soles. The condition may either be hereditary or acquired and in the form of associated syndrome(s), PPK being its pre-dominant component. Hereditary forms may be localized to the hands and feet or associ-ated with more generalized skin disorders.

Diffuse nonepidermolytic palmoplantar kera-toderma (NEPPK), Thost-Unna disease, and PPK diffusa circumscripta were first described by Thost2 and Unna3 and later delineated into clinical variants by Greither.4 NEPPK is characterized by diffuse hyperkeratosis of the palms and soles that usually becomes appar-ent between ages 3 months and 12 months. This autosomal dominant condition presents with thick, diffuse hyperkeratosis with an erythematous border affecting the palms and soles.2,3 Aberrant keratotic lesions may appear on the dorsum of the hands, feet, knees, and elbows.3,4 Hyperhidrosis,2,3 thickened nails,2 clinodactyly,15 low serum Vitamin A,2 der-matophytosis,16 cutaneous horns,17 contrac-tures,10 and dyskeratosis congenita18 are its other associated features. The incidence of dermatophytosis was found to be 35% with an almost complete therapeutic resistance, especially in Trichophyton rubrum.16 Histology was marked by nonspecific changes, such as orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis, hypergranulo-sis/normogranulosis, and associated moder-ate acanthosis.2,3,19 Linkage to type II keratin locus on 12q11-13 has been reported with K1 gene mutation in a single family.19 The resi-due involved, K741, is the most frequently

found in the cross-linking of the cornified cell envelope.19 Significantly, other families with NEPPK have been mapped outside the keratin cluster 12q11-13.19

Diffuse epidermolytic PPK (Vorner disease, PPK cum degeneration granulosa) is the most common type of hereditary PPK.20,21 Localized epidermolytic hyperkeratosis, first described by Vorner22 and Klaus et al.,23 demonstrat-ed dominant inheritance and male-to-male transmission, which was later substantiat-ed,11,24,25 although the inheritance is said to be autosomal dominant. Some researchers26 suggested the existence of an autosomal reces-sive form, but because of the high background frequency of consanguinity in Kuwait where the patients were observed and because of the possibility of gonadal mosaicism, the evidence

Table I. Allelic Variants of Vorner Epidermolytic Palmoplantar Keratoderma (EPPK)

NUMBER DESCRIPTION MUTATION

0001 EPPK KRT9, ARG162TRP

0002 EPPK KRT9, GLN171PRO

0003 EPPK KRT9, ASN160TYR

0004 EPPK KRT9, ASN160LYS

0005 EPPK KRT9, ARG162GLN

0006 EPPK KRT9, MET156VAL

0007 EPPK KRT9, ASN160SER

0008 EPPK KRT9, LEU167SER

0009 EPPK KRT9, LEU159VAL

0010 EPPK KRT9, MET156THR

KRT9=keratin 9

Table II. Clinical Features of Unna-Thost-Vorner Palmoplantar Keratoderma (PPK)

GENETIC FEATURES

Autosomal dominantRarely autosomal recessiveOften presents within the first 1–2 years of life

CLINICAL FEATURES

Diffuse hyperkeratosis over palms and solesRed band at the periphery of the keratosis is frequentAberrant keratotic lesions on the dorsum of the hands, feet, knees, and elbowsNails may be thickenedAssociations include clinodactyly, dermatophytosis, cutaneous horns, contractures, raised serum IgE, low serum vitamin A, knuckle

pads, clubbing, epidermolytic hystric nevus, and Ehlers-Danlos syndrome

HISTOLOGY

Overlap between orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis associated with hypergranulosis/normogranulosis, moderate acanthosis, and epider-molytic hyperkeratosis

MOLECULAR BIOLOGY

Linkage to type II keratin locus on 12q11-13 (nonepidermolytic PPK)Linkage to type I keratin locus on 17q21.1-q21.2 (epidermolytic PPK)Major gene mutation sites include K1-K741 (nonepidermolytic PPK); exon 6 splice donor site of keratin 1 (G4134A) (EPPK) and K9-

R162W, heterozygous missense mutations in exon 1, Q171P, asn160-to-tyr, asn160-to-lys, and N160I (epidermolytic PPK)

SKINmed: Dermatology for the Clinician (ISSN 1540-9740) is published bimonthly (Jan., March, May, July, Sept., Nov.) by Le Jacq Communications, Inc., Three Parklands Drive, Darien, CT 06820-3652. Copyright ©2004 by Le Jacq Communications, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. The opinions and ideas expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Editors or Publisher. For copies in excess of 25 or for commercial purposes, please contact Sarah Howell at [email protected] or 203.656.1711 x106.

326 November • December 2004

H P P K : I l l u s t r a t i o n T h r o u g h a F a m i l i a l R e p o r t

for recessive inheritance is not strong in this small family. Epidermolytic PPK is probably one of the most common keratin diseases, with an incidence of at least 4.4 per 100,000 in Northern Ireland.19 The condition presents in the first year of life and is phenotypically similar to NEPPK.21 Histology of the condition reveals epidermolytic hyperkeratosis, which was thought to differentiate it from NEPPK.20

In a large family with epidermolytic PPK of the Vorner-Unna-Thost type, one group27 mapped the gene to 17q11-q23. Other groups28,29 con-cluded by linkage analysis that the disease mutation maps to the same region as the type

1 (acidic) keratin gene cluster. One acidic kera-tin, keratin 9 (KRT9), is expressed only in the terminally differentiated epidermis of palms and soles; thus, the KRT9 gene is the most probable site of the mutation in epidermolytic PPK and this gene has been mapped to a chro-mosome.27–29 Five different KRT9 gene muta-tions (the R162W mutation) were found in five other apparently unrelated epidermolytic PPK families.20,29 All of these mutations are local-ized in the highly conserved coil-1A region of the rod domain, which is thought to be relevant for dimer formation in intermediate filaments.20,29 The R162W mutation is in the residue corresponding to that which is altered

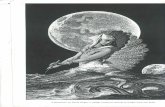

Figure 1. A family pedigree of palmoplantar keratoderma

Maternalgrandmother

Maternalgrandfather

Paternalgrandfather

Paternalgrandmother

Patient

- Died at the age of 4 years - Was suffering from

crippling paralysis - Not able to stand since

birth- Could utter only

“Allah & Amma” - Hearing, vision—Normal - Features on death

• Massive ascites • Wasting of all muscles

especially of limbs - Skin lesions—dermatitis

all over body started on abdomen and then became generalized and hyper-pigmented

Affected person

Woman

Status unknown

Man

- Cracks on soles and palms

SKINmed: Dermatology for the Clinician (ISSN 1540-9740) is published bimonthly (Jan., March, May, July, Sept., Nov.) by Le Jacq Communications, Inc., Three Parklands Drive, Darien, CT 06820-3652. Copyright ©2004 by Le Jacq Communications, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. The opinions and ideas expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Editors or Publisher. For copies in excess of 25 or for commercial purposes, please contact Sarah Howell at [email protected] or 203.656.1711 x106.

327November • December 2004

H P P K : I l l u s t r a t i o n T h r o u g h a F a m i l i a l R e p o r t

in keratins, KRT14 and KRT10 in epidermolysis bullosa simplex and epidermolytic hyperkera-tosis, respectively.20,28,29 Researchers30 refined the assignment of the KRT9 gene to 17q21.1-q21.2 by fluorescence in situ hybridization. Experimental evidence was obtained that the arg162-to-gln point mutation observed in patients with epidermolytic HPPK has a dominant-negative effect on keratin network formation.31 The same author group31 also summarized published reports of mutations in KRT9 associated with epidermolytic PPK and commented that amino acid residues 156-171, which correspond to the head of the KRT9 alpha-helical domain, may be crucial for kera-tin filament assembly and intermediate fila-ment network formation.31 Four Northern Irish kindreds with epidermolytic PPK were studied, and heterozygous missense mutations in exon 1 of KRT9 was found in all of the families.32

Recently, a novel mutation in the exon 6 splice donor site of keratin 1 (G4134A) has been noticed in three kindreds.33 This muta-tion appears to have a milder effect than previously described mutations in the helix initiation and termination sequence on the function of the rod domain, with regard to fil-ament assembly and stability. Affected persons

displayed only mild focal epidermolysis in the spinous layer of palmoplantar epidermis. A follow-up study34 of the family originally seen by Vorner in 1901 with clinical, histopatho-logic, and molecular investigations, revealed the typical features of the condition and a novel mutation in KRT9, N160I. The muta-tion in the coil-1A domain is thought to have a dominant negative effect on the assembly of keratin intermediate filaments, explaining the dominant inheritance of the phenotype.31,34 The various allelic types of epidermolytic PPK are indexed in Table I.

Associations of epidermolytic PPK include raised serum IgE,26 knuckle pads,35 clubbing,36 epidermolytic hystric nevus,37 Ehlers-Danlos syndrome,38 nail changes and periodonto-sis,39 malignancy,40 Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome, Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome, famil-ial atypical multiple mole melanoma syn-drome, hereditary tylosis, incontinentia pig-menti, supernumerary nipples,41 hereditary motor and sensory neuropathy,42 hereditary callosities with blisters,43 and adenocarci-noma of the colon.44

Figure 2. Soles affected by palmoplantar keratoderma showing immense and well circumscribed, waxy yel-low thickening of the skin surrounded by prominent erythematous border and fissures/cracks

Figure 3. Palms affected by palmoplantar keratoder-ma showing fissure/cracks with scaling

Figure 4. Hematoxylin-eosin stained section of palmoplantar keratoderma tissue depicting variable degree of hypergranulosis and acanthosis

SKINmed: Dermatology for the Clinician (ISSN 1540-9740) is published bimonthly (Jan., March, May, July, Sept., Nov.) by Le Jacq Communications, Inc., Three Parklands Drive, Darien, CT 06820-3652. Copyright ©2004 by Le Jacq Communications, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. The opinions and ideas expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Editors or Publisher. For copies in excess of 25 or for commercial purposes, please contact Sarah Howell at [email protected] or 203.656.1711 x106.

328

H P P K : I l l u s t r a t i o n T h r o u g h a F a m i l i a l R e p o r t

November • December 2004

Are Unna-Thost and Vorner the Same Entities?The Unna-Thost form of PPK is clinically iden-tical to localized epidermolytic hyperkeratosis of the palms and soles as described by Vorner.22 Although they were earlier thought to be his-topathologically distinguishable, reappraisal of the kindred originally analyzed by Thost2 and study of a descendant supported separate identities for the two conditions.11 By rein-vestigation of the family originally seen by Thost2 in 1880, the features of epidermolytic hyperkeratosis were found histologically, con-firming the diagnosis PPK by Vorner.11 This proves the identity of PPK type Thost with PPK of Vorner. Also, it should be noted that both epidermolytic and nonepidermolytic forms of PPK have been observed with vari-ous mutations in the keratin 1 gene.20 Indeed, mutations of the KRT1 and KRT9 genes that are associated with the epidermolytic form of PPK affect the central regions of the protein that are important for filament assembly and stability, and for that reason lead to cellular degeneration or disruption.19,20 On the other hand, the mutation of the KRT1 gene that was found in association with nonepidermolytic PPK involved the amino-terminal variable end region, which may be involved in supramo-lecular interactions of keratin filaments rather than stability.45 A recent molecular analysis gives further evidence that PPK of Vorner rep-resents the same entity as PPK of Thost.20

A recent re-evaluation of Thost’s original family revealed that the condition was caused by a similar mutation, R162W, in the same segment of KRT9 as in epidermolytic PPK. Studies29,30 demonstrated substitution of tryptophan for arginine-162 as the result of a mutation in exon 1 of the KRT9 gene in large German epidermolytic PPK kindred and in five other apparently unrelated families. The R162W mutation was seen in one of the five families originally described by Thost.11

This is convincing evidence that the disorder previously listed as a separate entity in these catalogs is in fact the same as epidermolytic hyperkeratosis. The clinical features of the Unna-Thost-Vorner syndrome are summa-rized in Table II.

TreatmentAlthough treatment of the condition is not sat-isfactory yet, various topical treatments (namely

6% and 12% salicylic acid in white soft paraf-fin,19–21 6% salicylic acid in 70% propylene gly-col,20,21 benzoic acid compounds,19,20 and cal-cipotriol46) have been tried. Systemic retinoids are a useful therapeutic option in disorder of cornification.47 It is, therefore, worthwhile to administer them in HPPK. It is paramount to monitor the results of treatment by liver function test, kidney function test, and lipid profile in addition to clinical examination. The retinoids have been sparingly tried in the past in this condition with the proviso to use with caution and in those where the condition is recalcitrant.20,24 Isotretinoin administration is a useful alternative at dosages of 0.5–1 mg/kg body weight/d up to 4–8 weeks with stringent monitoring.48 Itraconazole pulse comprising 400 mg/d in two equal divided dosages admin-istered with major meals is a useful adjunct in situations where the lesions are infested with dermatophytes vide supra.10,21 This may be repeated after a 3-week period.

An IllustrationA 21-year-old Muslim, the product of a con-sanguineous marriage (paternal and maternal grandmothers were sisters) developed pro-gressive papular and erythematosquamous rash over his abdomen on precisely his third day of life. A month after his birth, the patient’s mother observed fine cracks and scales over the boy’s palms and soles that had a yellowish hue. The patient was also irritable, possibly due to discomfort from the palms and soles. The rashes over the hands and feet considerably increased to alter the texture of the skin and to occupy their current position. Itching and/or pain were its preeminent features. Profuse sweating of the affected part was also an attribute. The patient preferred the winter season and cher-ished wandering in the cold. His only elder brother had similar, much more severe com-plaints and had succumbed to the disease at age four years. The boy’s parents had identi-cal palms and soles, the details of which are outlined in sequence in Figure 1.

Immense thickening of the skin might virtu-ally mask the creases, a “hallmark” in the examination of the soles of the foot. The thickening was well circumscribed and its margin was surrounded by a conspicuous ery-thematous (halo) border. It was waxy yellow in color. The skin was taut and had explicit

SKINmed: Dermatology for the Clinician (ISSN 1540-9740) is published bimonthly (Jan., March, May, July, Sept., Nov.) by Le Jacq Communications, Inc., Three Parklands Drive, Darien, CT 06820-3652. Copyright ©2004 by Le Jacq Communications, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. The opinions and ideas expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Editors or Publisher. For copies in excess of 25 or for commercial purposes, please contact Sarah Howell at [email protected] or 203.656.1711 x106.

329

H P P K : I l l u s t r a t i o n T h r o u g h a F a m i l i a l R e p o r t

November • December 2004

fissures/cracks (Figure 2). The latter were dirty yellow and fairly deep. Similar, less-pro-nounced morphologic changes were elicited on the palms (Figure 3). The symmetry of the lesions was cardinal. The changes in the nails were not that pronounced. The rest of the skin surface was somewhat dry and scaly.

Investigations, including total and differential leukocyte counts, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, random blood sugar, blood urea, serum electrolytes, and serum calcium were within norms. Hematoxylin-eosin stained sections prepared from fragile biopsy from the affected sole depicted conspicuous changes confined primarily to the epidermis. Orthokeratotic

hyperkeratosis was strikingly exquisite. Nonetheless, a variable degree of hypergranu-losis and acanthosis was noticeable (Figure 4). Periodic acid-Schiff reaction was unable to identify mycelia/spores in the tissue sections.

PPK, an interesting hereditary entity, has been studied from the day its clinical expres-sion was outlined. The condition has since been reported either sporadically or in a fam-ily.10,40,49–52 The recount of such cases is not only a reminder of the condition but also a way to enrich the knowledge base. In addition to the classic clinical expression, any devia-tion in its morphologic characteristics should be carefully recorded.

REFERENCES 1 Bonifas JM, Matsumura K, Chen MA, et al.

Mutations of keratin 9 in two families with pal-moplantar epidermolytic hyperkeratosis. J Invest Dermatol. 1994;103:474–477.

2 Thost A. Ueber Erbliche Ichthyosis Palmaris Et Plantaris Cornea. Dissertation. Heidelberg, Germany: University of Heidelberg; 1880.

3 Unna PG. Ueber das Keratoma palmare et plantare hereditarium. Arch Derm Syph. 1883;15:231–270.

4 Greither A. Keratosis extremitatum hereditaria progrediens mit dominantem Erbgang. Hautarzt. 1952;3:198–203.

5 Gulati S, Thappa DM, Garg BR. Hereditary palmo-plantar keratodermas in South India. J Dermatol. 1997;24:765–768.

6 Gamborg Nielsen P, Brandstrom A. Adoption of a demographic database for family studies of heredi-tary palmoplantar keratoderma type Gamborg Nielsen. Dermatology. 1994;188:194–199.

7 Maruyama R, Katoh T, Nishioka K. A case of Unna-Thost disease accompanied by Epidermophyton floccosum infection. J Dermatol. 1999;26:63–66.

8 Gamborg Nielsen P, Faergemann J. Dermatophytes and keratin in patients with hereditary palmo-plantar keratoderma. A mycological study. Acta Derm Venereol. 1993;73:416–418.

9 Nielsen PG. Hereditary palmoplantar kerato-derma and dermatophytosis in the northern-most county of Sweden (Norrbotten). Acta Derm Venereol Suppl (Stockh). 1994;188:1–60.

10 Sehgal VN, Kumar S, Narayan S. Hereditary palmoplantar keratoderma (four cases in three generations). Int J Dermatol. 2001;40:130–132.

11 Kuster W, Becker A. Indication for the identity of palmoplantar keratoderma type Unna-Thost with type Vorner. Thost’s family revisited 110 years later. Acta Derm Venereol. 1992;72:120–122.

12 Blasik LG, Dimond RL, Baughman RD. Hereditary epidermolytic palmoplantar keratoderma. Arch Dermatol. 1981;117:229–231.

13 Bernett J Jr, Honig P. Genodermatosis. In: Elder D, Elenitsal R, Jaworsky C, et al., eds. Lever’s Histopathology of the Skin. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 1997:120.

14 Gamborg Nielsen P, Hofer PA, Lagerholm B. The dominant form of hereditary palmoplantar kera-toderma in the northernmost county of Sweden (Norrbotten). Dermatology. 1994;188:188–193.

15 Anderson IF, Klintoworth GK. Hypovitaminosis-A in a family with tylosis and clinodactyly. BMJ. 1961;1:1293–1297.

16 Gamborg Nielsen P. Dermatophyte infections in hereditary palmo-plantar keratoderma. Frequency

and therapy. Dermatologica. 1984;168:238–241. 17 Sehgal VN, Thappa DM, Jain S. Palmoplantar ker-

atoderma with cutaneous horns. Int J Dermatol. 1992;31:369–370.

18 Sehgal VN, Thappa DM, Sharma RC, et al. Dyskeratosis congenita: a case report. J Dermatol. 1993;20:56–58.

19 Irvine AD, Paller AS. Molecular genetics of the inherited disorders of cornification: an update. Curr Probl Dermatol. 2002;14:84–86.

20 Kanitakis J, Tsoitis G, Kanitakis C. Hereditary epidermolytic palmoplantar keratoderma (Vorner type). Report of a familial case and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:414–422.

21 Hamm H, Happle R, Butterfass T, et al. Epidermolytic palmoplantar keratoderma of Vorner: is it the most frequent type of heredi-tary palmoplantar keratoderma? Dermatologica. 1988;177:138–145.

22 Vorner H. Zur Kenntniss des Keratoma heredi-tarium palmare et plantare. Arch Derm Syph. 1901;56:3–31.

23 Klaus S, Weinstein GD, Frost P. Localized epi-dermolytic hyperkeratosis: a form of kerato-derma of the palms and soles. Arch Dermatol. 1970;101:272–275.

24 Fritsch P, Honigsmann H, Jaschke E. Epidermolytic hereditary palmoplantar keratoderma, report of a family and treatment with an oral aromatic reti-noid. Brit J Dermatol. 1978;99:561–568.

25 Camisa C, Williams H. Epidermolytic variant of hereditary palmoplantar keratoderma. Brit J Dermatol. 1985;112:221–225.

26 Alsaleh QA, Teebi AS. Autosomal recessive epider-molytic palmoplantar keratoderma. J Med Genet. 1990;27:519–522.

27 Reis A, Kuster W, Eckardt R, et al. Mapping of a gene for epidermolytic palmoplantar keratoder-ma to the region of the acidic keratin gene cluster at 17q12-q21. Hum Genet. 1992;90:113–116.

28 Hennies HC, Zehender D, Kunze J, et al. Keratin 9 gene mutational heterogeneity in patients with epidermolytic palmoplantar keratoderma. Hum Genet. 1994;93:649–654.

29 Hennies HC, Kuster W, Langbein L, et al. Keratin 9 gene mutations in epidermolytic palmoplantar keratoderma (EPPK). Am J Hum Genet. 1993;53:A211.

30 Reis A, Hennies HC, Langbein L, et al. Keratin 9 gene mutations in epidermolytic palmoplantar keratoderma (EPPK). Nat Genet. 1994;6:174–179.

31 Kobayashi S, Tanaka T, Matsuyoshi N, et al. Keratin 9 point mutation in the pedigree of epidermolytic

SKINmed: Dermatology for the Clinician (ISSN 1540-9740) is published bimonthly (Jan., March, May, July, Sept., Nov.) by Le Jacq Communications, Inc., Three Parklands Drive, Darien, CT 06820-3652. Copyright ©2004 by Le Jacq Communications, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. The opinions and ideas expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Editors or Publisher. For copies in excess of 25 or for commercial purposes, please contact Sarah Howell at [email protected] or 203.656.1711 x106.

330 November • December 2004

H P P K : I l l u s t r a t i o n T h r o u g h a F a m i l i a l R e p o r t

hereditary palmoplantar keratoderma perturbs keratin intermediate filament network formation. FEBS Lett. 1996;386:149–155.

32 Covello SP, Irvine AD, McKenna KE, et al. Mutations in keratin K9 in kindreds with epider-molytic palmoplantar keratoderma and epide-miology in Northern Ireland. J Invest Dermatol. 1998;111:1207–1209.

33 Hatsell SJ, Eady RA, Wennerstrand L, et al. Novel splice mutation in keratin 1 underlies mild epi-dermolytic palmoplantar keratoderma in three kindreds. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;116:606–609.

34 Kuster W, Reis A, Hennies HC. Epidermolytic pal-moplantar keratoderma of Vorner: re-evaluation of Vorner’s original family and identification of a novel keratin 9 mutation. Arch Dermatol Res. 2002;294:268–272.

35 Nogita T, Nakagawa H, Ishibashi Y. Hereditary epidermolytic palmoplantar keratoderma with knuckle pad-like lesions over the finger joints. Brit J Dermatol. 1991;125:496.

36 Barraud-Klenovsek MM, Lubbe J, Burg G. Primary digital clubbing associated with palmoplantar keratoderma. Dermatology. 1997;194:302–305.

37 Hadlich J, Linse R. Keratoses with granular degeneration and their relations to each other. II. Heterophenotypic expression of hyperkeratosis (erythrodermia congenitalis ichthyosiformis bul-losa), naevus hystricoides and Vorner keratosis palmoplantaris cum degeneratione granulose. Dermatol Monatsschr. 1989;175:418–424.

38 Mofid MZ, Costarangos C, Gruber SB, et al. Hereditary epidermolytic palmoplantar keratoder-ma (Vorner type) in a family with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;38:825–830.

39 Miteva L, Dourmishev AL. Hereditary palmoplan-tar keratoderma with nail changes and periodon-tosis in a father and son. Cutis. 1999;63:65–68.

40 Stevens HP, Kelsell DP, Leigh IM, et al. Punctate palmoplantar keratoderma and malignan-cy in a four-generation family. Br J Dermatol. 1996;34:720–726.

41 Cohen PR, Kurzrock R. Miscellaneous genoder-matoses: Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome, Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome, familial atypical multiple mole melanoma syndrome, hereditary tylosis, incontinentia pigmenti, and supernumerary

nipples. Dermatol Clin. 1995;13:211–229. 42 Tolmie JL, Wilcox DE, McWilliam R, et al.

Palmoplantar keratoderma, nail dystrophy, and hereditary motor and sensory neuropa-thy: an autosomal dominant trait. J Med Genet. 1988;25:754–757.

43 Baden HP, Bronstein BR, Rand RE. Hereditary callosities with blisters. Report of a family and review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;11:409–415.

44 Bennion SD, Patterson JW. Keratosis punctata palmaris et plantaris and adenocarcinoma of the colon. A possible familial association of punctate keratoderma and gastrointestinal malignancy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;10:587–591.

45 Kimonis V, DiGiovanna JJ, Yang JM, et al. A mutation in the V1 end domain of keratin 1 in non-epidermolytic palmar-plantar keratoderma. J Invest Dermatol. 1994;103:764–769.

46 Lucker GP, van de Kerkhof PC, Steijlen PM. Topical calcipotriol in the treatment of epider-molytic palmoplantar keratoderma of Vorner. Br J Dermatol. 1994;130:543–545.

47 Sardana K, Sehgal VN. Retinoids: fascinat-ing up-and-coming scenario. J Dermatol. 2003;30:355–380.

48 Jain S, Sehgal VN. Itraconazole versus terbinafine in the management of onychomycosis: an over-view. J Dermatolog Treat. 2003;14:30–42.

49 Mayuzumi N, Shigihara T, Ikeda S, et al. R162W mutation of keratin 9 in a family with autoso-mal dominant palmoplantar keratoderma with unique histologic features. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 1999;4:150–152.

50 Requena L, Schoendorff C, Sanchez Yus E. Hereditary epidermolytic palmo-plantar kera-toderma (Vorner type)—report of a family and review of the literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1991;16:383–388.

51 Wachters DH, Frensdorf EL, Hausman R, et al. Keratosis palmoplantaris nummmularis (“hereditary painful callosities“). Clinical and histopathologic aspects. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;9:204–209.

52 Johansson EA, Kariniemi AL, Niemi KM. Palmoplantar keratoderma of punctate type: acrokeratoelastoidosis Costa. Acta Derm Venereol. 1980;60:149–153.

SKINmed: Dermatology for the Clinician (ISSN 1540-9740) is published bimonthly (Jan., March, May, July, Sept., Nov.) by Le Jacq Communications, Inc., Three Parklands Drive, Darien, CT 06820-3652. Copyright ©2004 by Le Jacq Communications, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. The opinions and ideas expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Editors or Publisher. For copies in excess of 25 or for commercial purposes, please contact Sarah Howell at [email protected] or 203.656.1711 x106.

331November • December 2004

1. Hereditary palmoplantar keratodermas (HPPKs) are most commonly transmitted as a/an:a) Sex-linked (x-linked) recessive traitb) Sex-linked (x-linked) dominant traitc) Autosomal dominant traitd) Autosomal recessive traite) Autosomal codominant trait

2. HPPKs are most commonly present: a) At birthb) At ages 0–10 yearsc) At pubertyd) At ages 10–30 yearse) During adulthood

3. The most common type of HPPK is:a) Unna-Thostb) Greitherc) Vohwinkeld) Idiopathic punctuate and ichthyosis

vulgaris-associatede) Mal de Maleda

4. Of the following, the most common type of HPPK has been found to be:a) Gamborg Nielsonb) Mal de Meledac) Greitherd) Vohwinkele) Idiopathic punctuate and ichthyosis

vulgaris-associated

5. Approximately what proportion of cases of HPPK is associated with dermatophy-tosis?a) 0.55%b) 5.5%c) 15%d) 35%e) 55%

6. The most common dermatophyte associ-ated with HPPK has been found to be:a) Trichophyton rubrumb) Trichophyton mentagrophytesc) Epidermophyton floccosum

7. Which of the following systemic factors has been found to be associated with der-matophytoses complicating HPPK?a) Blood group Ab) Increased specific anti-dermatophyte

IgG antibodiesc) Precipitating antibodiesd) An in vitro immunological reaction to

keratine) All of these

8. A mononuclear cell infiltrate, together with spongiotic vesicles, seen on histo-logical examination of a biopsy of a case of HPPK is indicative of:a) Unna-Thost type HPPKb) Greither type HPPKc) Vohwinkel type HPPKd) Gamborg Nielson type HPPKe) A reaction to dermatophytosis

9. Epidermolytic changes seen on histologic examination of biopsies of cases of HPPK are:a) Rareb) Present in descendants of the original

family published by Thost, but are uncommon in other families

c) Not found in descendants of the origi-nal family published by Thost, but are invariably found in other families

d) Found in the majority of cases of HPPK

e) Invariably found in HPPK

Address for correspondence: W. Clark Lambert, MD, PhD, Departments of Dermatology and Pathology, New Jersey Medical School, University of Medicine & Dentistry of New Jersey, 185 South Orange Avenue, Room C520, Medical Sciences Building, Newark, NJ 07103 E-mail: [email protected]

Review QuestionsHereditary Palmoplantar (Epidermolytic) Keratoderma: Illustration Through a Familial Report

S e l f - T e s t R e v i e w Q u e s t i o n s

W. Clark Lambert, MD, PhD Departments of Dermatology and Pathology, New Jersey Medical School, University of Medicine & Dentistry of New

Jersey, Newark, NJ

Instructions for Questions 1–9: For each ques-tion, select the single most appropriate response.

SKINmed: Dermatology for the Clinician (ISSN 1540-9740) is published bimonthly (Jan., March, May, July, Sept., Nov.) by Le Jacq Communications, Inc., Three Parklands Drive, Darien, CT 06820-3652. Copyright ©2004 by Le Jacq Communications, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. The opinions and ideas expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Editors or Publisher. For copies in excess of 25 or for commercial purposes, please contact Sarah Howell at [email protected] or 203.656.1711 x106.

332 November • December 2004

S e l f - T e s t R e v i e w Q u e s t i o n s

10. In the Unna-Thost type of HPPK, aberrant keratotic lesions may appear on (the):a) Dorsal aspects of the handsb) Dorsal aspects of the feetc) Elbowsd) Kneese) All of these sites

11. The Vorner type of HPPK is most closely related to (the):a) Unna-Thost type of HPPKb) Mal de Meledac) Vohwinkel type of HPPKd) Greither type of HPPKe) Gamborg Nielson type of HPPK

12. Vormer epidermolytic palmoplantar kera-toderma is associated with mutations in the gene encoding keratin:a) 1b) 2c) 3d) 7e) 9

13. Which of the following keratins is expressed only on the palms and soles?a) Keratin 1b) Keratin 3c) Keratin 4d) Keratin 7e) Keratin 9

14. The Unna-Thost type of HPPK is some-times associated with:a) Thickened nailsb) Cutaneous hornsc) Contracturesd) Clubbinge) Knuckle pads

15. The Vormer type of HPPK is sometimes associated with (the):a) Elevated serum levels of vitamin Ab) Decreased serum levels of IgEc) Ehlers-Danlos syndromed) Epidermolytic hystric nevuse) Dermatophytosis

Instructions for Questions 10–13: For each ques-tion, select the single most appropriate response.

1. c; 2. b; 3. a; 4. c; 5. d; 6. b; 7. e; 8. e; 9. d; 10. e; 11. a; 12. e; 13. e; 14. a, b, c, d, e; 15. c, d, e

Answers to Review Questions

Instructions for Questions 14 and 15: For each numbered item, choose as many lettered responses as apply. All, some, one, or none of the lettered responses may be appropriate.

SKINmed: Dermatology for the Clinician (ISSN 1540-9740) is published bimonthly (Jan., March, May, July, Sept., Nov.) by Le Jacq Communications, Inc., Three Parklands Drive, Darien, CT 06820-3652. Copyright ©2004 by Le Jacq Communications, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. The opinions and ideas expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Editors or Publisher. For copies in excess of 25 or for commercial purposes, please contact Sarah Howell at [email protected] or 203.656.1711 x106.