GTZ MOAP Fruit Processing Manual - Market Oriented ...

-

Upload

khangminh22 -

Category

Documents

-

view

0 -

download

0

Transcript of GTZ MOAP Fruit Processing Manual - Market Oriented ...

PROCESSING MANUAL

Drying of fruit and vegetables and fruit juice extraction

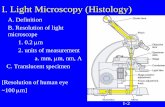

Indicative Process Flow Diagram for Fruit Juice Production

Tra

ns

po

rt -

tati

on

Pa

ck

ag

ing

Pa

ck

ag

ing

*P

roc

es

sin

g*

Re

ce

ivin

g

Flow

Interface

Flow

Interface

Flow

Interface

Flow

Raw Material

from

Suppliers

Final Processing

Flow

Quality Inspection

and

Receiving

Q u a r a n t i n e

Flow

Receipt Administration

Quality Inspection

and

Receiving

Storage

S t o r a g e

P a c k a g i n g ,

I n g r e d i e n t s ,

C h e m i c a l s

Flow

Flow

Fruit – Vegetables

from

Supplier

Flow

Flow

Pre processing

Dispatch StorageFlow

Quality Control

Quality AssuranceSecondary Packaging

Dispatch Documentation Completed

Flow

S t o r a g e

F r u i t

V e g e t a b l e sFlo

w

Dispatch Administration

Flow

Cleaning

& WashingSorting

Processing

Treatment

& RinsingBlending

Pulping

Pre-heating

Peeling &

Crushing

Flow

Flow

Interface

Pasteur-

izingFilling Sealing

Labeling

Tony Swetman, Olivier Van Buynder and Rob Moss

Prepared for GIZ Ghana

September 2011

2

Drying of fruit and vegetables and fruit juice extraction

Drying principles

Renewable energy dryers

Business planning

Factory management

Quality and hygiene

Relationships with farmers and ensuring a supply-base

Certification requirements for farm and factory

Tony Swetman, Olivier Van Buynder and Rob Moss

Prepared for GIZ Ghana

December 2010

3

Table of content

Foreword ................................................................................................................................... 6

Chapter 1: Introduction and Background .................................................................................. 8

Establishment of MOAP processing activities ...................................................... 9

Chapter 2: Market perspectives .............................................................................................. 10

Availability of dried fruit and vegetables in Ghana ............................................. 10

European market for dried fruit ........................................................................... 10

The juice market .................................................................................................. 11

Chapter 3: Ensuring a supply-base for fruit processing .......................................................... 12

Introduction – why worry about the supply-base? ............................................... 12

Types of supply base ............................................................................................ 13

Passive supply ...................................................................................................... 13

Managed outgrower schemes ............................................................................... 14

Contract farming with agri-businesses................................................................. 15

Own production ................................................................................................... 15

Planning and locating a factory............................................................................ 16

Information on areas of production ...................................................................... 17

Roles & responsibilities of the processing company when sourcing from farms 21

Farmers‟ responsibilities to processors and side-selling ...................................... 22

Establishing demonstration farms ........................................................................ 23

Out-grower selection ............................................................................................ 23

Technical and support services ............................................................................ 24

Financial services ................................................................................................. 25

Out-grower associations....................................................................................... 26

The cost of managing a supply base .................................................................... 27

Business management............................................................................................................. 29

Business plan ....................................................................................................... 29

Outline of the business plan ................................................................................. 29

Marketing Strategy............................................................................................... 30

Financial Plan....................................................................................................... 31

Staff grading - Paterson grading system.................................................................................. 35

Job evaluation or job grading involves the following:......................................... 35

How to apply the Paterson system ....................................................................... 36

Example of staff structure for a fruit-processing plant ........................................................... 37

Record keeping ........................................................................................................................ 38

4

Chapter 4 Fruit drying.............................................................................................................. 42

Basic principles of food drying ............................................................................ 42

Climatic conditions in Ghana............................................................................... 47

Mango harvesting season in Ghana ..................................................................... 49

Introduction of drying equipment in Ghana......................................................... 50

Solar Drying ......................................................................................................... 50

Equipment specifications for dried fruit processing ............................................................... 53

Cabinet dryer ........................................................................................................ 61

Process flow of a drying plant ............................................................................. 68

HACCP process for drying fruits .............................................................................................. 69

Post harvest handling and receiving of fresh fruit .................................................................. 76

Harvesting ............................................................................................................ 76

Pre processing fruit preparation ........................................................................... 77

Food hygiene management .................................................................................. 79

Good Manufacturing Practices - GMP ..................................................................................... 79

Dried fruit quality .................................................................................................................... 91

Chapter 5: Fruit juice production ............................................................................................ 95

Principles of Pasteurization ..................................................................................................... 97

Treatment of primary packaging material .......................................................... 101

HACCP process for fruit juice................................................................................................. 102

Chapter 6: Hygiene and control ............................................................................................ 109

Food factory hygiene and operation .................................................................. 109

Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Point system (HACCP) ......................... 109

HACCP Principles ................................................................................................................... 111

Hygiene in fruit juice and drying processing and products handling ................ 112

HACCP Auditing ..................................................................................................................... 114

Internal Audit by Department – Whole Production Line ...................................................... 114

Standard Operational Procedures (SOP) ............................................................................... 119

Chapter 7: Certification ......................................................................................................... 121

Farm certification: why is it necessary, what is it for? ...................................... 121

The complexities of certification: a brief overview ........................................... 121

Certification Standards .......................................................................................................... 123

5

Principals and criteria ........................................................................................ 124

The Inspection .................................................................................................... 126

Group Certification and Internal Control Systems ............................................ 127

Types of certification in West Africa................................................................. 131

Retail and supermarket agricultural good practice assurance standards ............ 131

Environmental impact and footprinting (e.g. Carbon and water footprinting) .................... 132

Fairtrade, social and ethical performance standards .......................................... 133

Organic, bio or biological certification .............................................................. 135

Voluntary sustainability standards (e.g. Rainforest Alliance) ........................... 137

Annex 1 Directory of certification standards ........................................................................ 138

Annex 2: List of supplier for parts to construct and repair the Solar 4 and TOBY dryers. .... 145

Annex 3: Material list for solar dryer .................................................................................... 146

Annex 4 Material list for TOBY cabinet dryer ........................................................................ 149

Annex 5 Standard operating procedures (SOP)..................................................................... 151

Standard operating procedures for receiving (deliv. by supplier or collection) 151

Standard operating procedures for receiving & storage .................................... 151

Standard operating procedures for pre - processing and handling of fruit ........ 152

Standard operating procedure for peeling and slicing ....................................... 152

Standard operating procedure for packing drying trays and drying ................. 153

Standard operating procedures packaging/storage and dispatch. ...................... 153

Standard operating procedures for receiving (delivery by supplier/collection) . 154

Standard operating procedures for receiving ..................................................... 154

Standard operating procedures for pre - processing and handling of fruit. ....... 155

Standard operating procedure for pulping ......................................................... 155

Standard operating procedure for filling, capping sealing ................................. 156

Standard operating procedures for packaging/storage and dispatch. ................. 156

Bibliography ........................................................................................................................... 157

6

Foreword

This handbook is from the field - for the field! It‟s content is based on demand,

encountered shortcomings and hands-on experience in developing agricultural value

chains in Ghana. Food processing was grossly underdeveloped and underrated in

policy approaches when we started in 2004 and still is by any international standards.

The dearth of data on the volumes of food processing in Ghana alone is testimony to

that. But in the new agricultural policies agro processing and value-chain approaches

feature prominently.

In fact food processing plays a crucial role in the development of agricultural value

chains and therefore in rural development and poverty alleviation. It became clear

very soon that access to markets is of course a key problem for rural producers. But

“access” is a summary formula for so many different problems or challenges. Still the

right quality, quantity and time of supply is a problem. And to get this right you have

to start on the field with the farmers and then follow through the chain to the end-user.

Linking so many actors and harmonising so many interests is indeed a great challenge

and on the way often key issues get lost. Chain facilitation is an important role to be

played. Ideally it should be played by a private sector representative who is in the

middle of the chain and has an interest to cover a greater segment of the chain.

Therefore processors are usually well situated to get engaged in chain facilitation.

Processors have a central position in an agricultural value chain since they are the

culmination point or nexus that links market demands and farmers‟ production

capacities. They not only provide a market to farmers, but to be successful, as this

manual shows, they also need to care about their supply base and provide services to

their farmers. At the same time they link to diverse markets and must understand

market forces and consumer demands. Because of these multiple functions they are so

important for value chain development and well deserve special attention of policy

makers and development agents.

But value chain actors tend to look either only on their own business disregarding the

forward and backward linkages or they look more on what others are doing and how

they could benefit from intruding into their business rather than to concentrate on

their part. But this is key: know you position in the value chain and play your role

well. Make sure you and your product meet all the demands. Don‟t even think of

expanding into other activities before you have your part absolutely under control and

right.

Quality is at the heart of matters and at the heart of quality is sound technical

knowledge and diligent management. It is here that this manual comes in. It provides

some of the technical details that are required to produce quality in food processing. It

enlightens on the meaning of quality management in processing. Quality management

covers the flow of processing activities but it extends beyond that. If the raw material

is not good your product will not be good. So you need to worry abut what farmers

deliver and what they are doing on the field because it affects the quality of the

processed product.

Yet another principle of quality management that we find neglected is: what is not

documented does not exist. There is no successful business without proper record

7

keeping. Record keeping is the basis for quality management but also for cost analysis

and cost control. In most cases you have little control over your selling price, i.e. the

market price, but you can control your costs. And more, quality control is linked to

cost control. It is usually the same points where things go wrong. So analysing your

process flow in detail by proper record keeping provides a lot insight for improvement

of the business.

But our experience is that processors grossly underestimate the efforts it takes to

ensure a quality supply of raw material at the right time. So this manual covers these

aspects too: linking to farmers, supporting group formation and quality assurance

trough certification processes. This is vital for successful processing operations and

requires considerable investments and attention. This manual probably provides a

unique overview of the challenges and costs of organising a good supply base.

This book covers some of the most important segments of the value chain and it pays

special tribute to the processors as providing a significant leverage for value chain

development.

There is a lot of different and detailed information in the manual. We do not suggest

to read this book cover to cover, but to study the table of content well and find what is

of interest to you.

In Ghana we say there is no easy enterprise – so true. We hope this book will help!

Lothar Diehl Rüdiger Behrens

Program manager Extension specialist and

MOAP chief editor of the manual

2004-2010 MOAP

8

Chapter 1: Introduction and Background

This manual is a product of the Market-Orientated Agriculture Programme (MOAP);

a programme of German Development Cooperation financed by the Federal Ministry

for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) and jointly implemented by

Ghana‟s Ministry of Food and Agriculture (MOFA), the German Technical

Cooperation (GTZ), and the German Development Service (DED). Since January

2011 the German Technical Cooperation organisations have been merged to form the

Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit or German International

Cooperation (GIZ).

MOAP aims to strengthen the agricultural sector‟s competitiveness on domestic and

foreign markets by capitalizing on the country‟s agricultural potential to generate

significant income for the rural population.

MOAP has used a three-component approach:

Component 1: Promotion of Value Chains

The value-chain concept views agriculture as agro-based business comprising:

Input provision

Primary production

Transformation and processing

Marketing and trade

Consumption

Commodities being supported are pineapple, mango, chilli-pepper, grasscutter,

guinea-fowl and fish and since the start of the second phase in 2010 also maize.

Typical MOAP activities are:

Value-chain and stakeholder analyses

Market studies

Increasing market power and access

Establishment of improved linkages along the value-chain

Development and introduction of good agricultural practices and quality

assurance

Development of nurseries

Introduction of small-scale processing technologies

Support of services along the value-chain

Providing guidance for business managers

Component 2: Improvement of service delivery from the public sector

Activities include mainstreaming trade regulatory and policy issues, supporting donor

co-ordination and providing policy advice

9

Component 3: Strengthening of agribusiness and their membership organizations

and institutions

Typical MOAP activities are:

Strengthening associations through institutional and organizational

development

Business and legal advice including advertising and promotion

Joint marketing and investment aid

Process facilitation

Market research and Information provision

Introduction of quality standards

Strengthening linkages between public and private sectors

Establishment of MOAP processing activities

More value can be added if the whole chain is more efficient and this is the premise

when MOAP entered into discussions with stakeholders along a particular value-

chain. For processed fruit products, for example, having more processors putting a

wider range of products on the market adds value to the sector as a whole.

Within the fruit sector in Ghana there are juice producers processing juice from

pineapple, mango and citrus. Some businesses are considering fruit pulp production

and others are keen to produce dried fruit. The production of dried pepper (chilli) is

also common within Ghana on a small scale. MOAP has worked with the range of

commodities and has looked at domestic, regional and international markets for

processors and helped develop production capacity and formulate recommendations

for interventions and support.

The authors of this manual have provided inputs to the MOAP since 2006. They have

helped to build up the programme in support of the processing industry. Through their

extensive experience of cooperation with many processors they have identified many

common bottlenecks and problems and have conducted training courses as well

individual support for some of the processing industries. Through this they brought

together information on local manufacture of processing procedures and equipment

mainly for fruit and vegetable drying and juice extraction. The collection of

information includes:

Organizing a raw material supply-base

Description of equipment

Factory layout

Product quality

Good manufacturing practice and markets

Workshop drawings

Other topics related to processing

This publication draws all these themes together to provide a source of information

for those entering agro processing businesses. The manual also covers the supply base

providing the raw materials from farms to a factory. The issue of obtaining the

minimum quality and quantity of raw materials for a factory to operate profitably is a

major problem encountered during MOAP‟s interaction with businesses in the

processing sector.

10

Chapter 2: Market perspectives

Availability of dried fruit and vegetables in Ghana

Many dried products are sold in markets in Ghana, including

whole and powdered dried red chilli,

dried powdered okra,

dried sorrel (whole hibiscus flowers),

dried powdered leaves.

Dried fruits, however, are not seen in street markets other than fry-dried plantain and

cocoyam, which are sold on the streets and in supermarkets and shops as snack food

items.

Dried mango, pineapple, banana, guava, papaya, and coconut strips have only recently

started to be produced and sold and, at the time of writing, are only marketed by three

or four companies. These are mainly packaged in either 100g sealed plastic bowls or

200g sachets. Other dried fruits found in shops are imported from South Africa or

South East Asia.

European market for dried fruit

Raisins (dried grapes), prunes (dried plums) and dates make up the majority of dried

fruits available in Europe. Other important dried fruits include apples, apricots,

bananas, cranberries, figs, mangoes, papaya, peaches, pineapples and tomatoes. Water

is usually removed by evaporation (air drying, sun drying, smoking or wind drying) or

by freeze-drying. Dried fruit has a long shelf life and can therefore provide a good

alternative to fresh fruit. Dried fruit is often added to baking mixes and breakfast

cereals and is valued for its intense flavour.

In 2008, a total of 2.65 million metric tonnes (mt) of dried fruit and vegetables with a

value of €3.1 billion were imported by EU countries – see table below. Around one-

third of this is from other EU countries. 47% is imported from Developing Countries

(DCs) and this share of imports is increasing.

EU Imports of dried fruit and vegetables 2004-2008,

value in € millions, volume in thousand mt

2004 2006 2008

Aver. Annual

Change % Value volume Value volume value volume in value

Total EU, 2,406 3,700 2,728 3,715 3,092 2,651 6.48% of which from Intra-EU 900 1,273 1,018 1,158 1,084 890 4.76% Extra-EU excl.

DC* 503 1,309 502 1,275 544 633 1.98%

DC* 1,003 1,118 1,208 1,281 1,464 1,128 9.93%

Source: Eurostat 2008 and 2009

*Developing Countries

11

The increase in imports of edible nuts and dried fruit and vegetables and the strong

position of DCs in this trade can be explained by a number of factors. First, EU

countries cannot produce much fruit and nuts cheaply themselves, so they are

imported. Secondly, consumption of dried fruits and exotic nuts is increasing due to a

number of trends including growing demand for luxury and convenience products and

growing markets in new member states. In addition it is also cheaper to import some

products, such as hazelnuts, walnuts and various dried fruit. Outsourcing is also a

trend, with European companies starting to invest in producing companies in other

countries (for instance Turkey), and then exporting the produce to the EU.

Dried fruit is used in consumer or food service packing, mainly consumed as a snack

and ingredient for breakfast cereals, healthy ready-to-eat snacks and desserts.

Bakeries and companies who prepare mixed breakfast cereals are two of the largest

end users of dried fruit.

The products are mostly imported in bulk to Europe, where they are packed - often

along with other dried fruit and nuts - as consumer products, or are sold as ingredients

for the processing industry.

The UK is the largest importer of dried fruit and vegetables in the EU, accounting for

19% of imports by value and by volume. Germany is the second largest importer;

France and Italy are the other main importers of vegetables. The four largest

importing countries account for 57% of the total import value. Import growth rates in

many new EU member states are higher than in older EU countries.

The above information is taken from CBI Market Survey – The Edible Nuts and Dried

Fruit and Vegetables Market in the EU (September 2009) compiled for CBI by

Mercado - http://www.cbi.eu/marketinfo

The juice market

The international market for juice is well researched and information can be obtained

from the web, e.g. http://www.macmap.org/ No attempt is made to reproduce this fast

changing market information here.

The juice market in Ghana unfortunately is not researched at all and very little to no

information is available. All we know is that juice is imported in considerable

quantities and that the production at the same time is slowly increasing. MOAP

conducted some market studies to test saleability of products and packaging. These

studies are not representative in any way, but they indicated that there is considerable

and growing demand for fresh juices particularly from the fast growing urban middle

income population. Hence MOAP felt safe to encourage juice processing. Obviously

those who invested in juice production in the recent past at considerable scale came to

the same conclusion.

However this manual is not about market opportunities but about specific aspects of

processing through juice manufacture and drying.

12

Chapter 3: Ensuring a supply-base for fruit processing

Introduction – why worry about the supply-base?

Some fruit processors have their own farms and produce their own raw materials, but

others rely partly or wholly on the fruit they buy. Whatever the supply strategy, the

supply of fruit is critical to the success of a processing company. Fruit needs to be

available to a processor in the Quantity, Quality and at the Time (QQT) the factory

needs in order to operate at a capacity that allows it to make a profit. It clearly would

be a bad business decision to put a factory where the cost of fruit is too high, even if

the QQT is good. Processing businesses need cheap raw materials, but factory-gate

prices must be high enough so that everyone, farmers, middlemen, truckers, the

factory and clients can all make money. Unless QQT+Cost are all within boundaries

that make it possible for all the actors in the value chain to make profit, the business is

not viable. This section is about the raw material supply issues that need to be

considered in planning a fruit processing business

What are the goals for a supply base?

A predictable supply of fruit in terms of meeting minimum quality requirements.

A predictable quantity that allows the factory to operate above its break-even

threshold for capacity utilization and allows it to meet orders from clients,

Supplies that are well organized to arrive at the factory in a steady and predicable

rate so that the factory does not get overwhelmed and nothing gets spoiled

unnecessarily; while at the same time avoiding days when the factory is fully

staffed but there is nothing to process.

The cost for fruit delivered at a fair price (so low enough for the factory to make

its profit but high enough for farmers supplying the fruit to make their profit).

The supply base should be able to expand if the processing company grows.

Farms and factory should have an interlocking relationship so that both benefit

from each other‟s success. Both sides should be able to continually improve

performance. This means farms can improve QQT and reduce costs of production

and factory can operate more efficiently and so be able to pay farmers adequately.

Both farms and factories operate without causing environmental damage or

engaging in unethical business practice so that future growth and long term

business sustainability is possible.

13

Types of supply base

There are four types of supply-base for a processing business

Passive Supply

Managed outgrower schemes

Contract Farming

Own Production

Type Characteristics Advantages Suitability

Passive

supply

Opportunistic buying,

where a processor

waits for fruit to be

become available.

Low investment. Works

well when there is a

surplus and fruit is

available and cheap.

Good for small processors with limited capital cost or

staff costs that can operate intermittently and at low

overall capacity without jeopardizing the business.

Managed

outgrower

schemes

Farmers in groups or

cooperatives

collaborating with a

processor to supply a

factory.

Capable of supplying

according to QQT

requirements; but with

some flexibility over

time

Suitable for many businesses that have clear QQT

requirements for fruit supply and the ability to manage

a scheme. Useful in places where land availability is

poor, or tenure arrangements uncertain so companies

cannot easily acquire their own farms. These schemes

can grow with the businesses they supply. Many oil-

palm processing factories have outgrower schemes.

Contract

farming

There are various ways

contract farming can be

managed. It depends on

the farmer being able

to manage their own

affairs and keep to a

contract

More formal and

generally more

potential for

professionalization than

cooperatives of small

farmers. Stronger and

more legally binding

relationship

Most common where farms are run as professional

agribusinesses. Suitable for processors that want to

have a small number of professionally managed farms

supplying them. High performance farm management

can be achieved more easily and farms are more likely

to make capital investments (e.g. in irrigation systems,

tractors etc) to reduce production costs, in order to

supply a factory.

Own

Production

Growing fruit on

company farms or on

leased land or in share-

cropping arrangements

Gives direct control of

the supply base.

Suitable for many processing businesses, especially

those with strong contractual commitments to their

markets as well as high QQT requirements. A company

must have the resources and technical expertise to do

this well. Even if the majority of raw material comes

from out-growers or contract farmers, a company may

still want its own farm for demonstration, training and

research purposes.

As processing businesses grow and they demand more supply and better performance

from their suppliers they will tend to move from passive supply towards a mixture of

the other options.

Passive supply

A processor waits for farmers to have fruit available at an affordable price, but does

not get directly involved in encouraging farmers to increase production or to produce

in one way or another. This approach is cheap, not needing any significant

investment, but with the disadvantage of the processor have little or no control. When

fruit is abundant, and therefore probably cheap, this works well as fruit is obtained at

a low cost. If the processing business is consistent and always buys fruit from the

same farmers, and pays promptly, then over time farmers will gain confidence and

loyal farmers will become reliable and regular suppliers to a factory. However, unless

the factory pays above market prices, or pays farmers promptly, or invests into the

14

farms then farmers will always look for the highest price and have no reason to

remain loyal to one buyer.

This approach is suitable for small processing operations that have limited investment

in equipment, for example, small family businesses selling small volumes of fresh

fruit juice. If such a small type of business stops operating for a few weeks or months,

or operates at low capacity then the survival of the business may not be jeopardized. If

fruit becomes too expensive, they simply wait for supply to increase and prices to

reduce. Big factories with a lot of capital equipment and overhead costs can only use

this approach to obtain relatively small amounts of their raw-material. They would

need to have the majority supplied by more certain and secure sources. This works

best for crops that are non perishable and which are produced throughout the year. A

good example is coconut. There are many coconut processing factories in South East

Asia processing coconut, and these often have relatively simple equipment. They do

not have out-grower schemes but rely on middle-men to bring fruit from farmers. For

a factory processing highly perishable fruits with a short season this can be a risky

strategy in years when supply is low and competition and prices high.

Managed outgrower schemes

A processor takes fruit from farmers with which the processor has a buyer/supplier

relationship. Normally outgrowers are grouped into outgrower associations set up by

the processor. Sometimes processors take fruit from pre-existing cooperatives or

associations; in the case of working with a cooperative the processor is not obliged to

take fruit from every member, they can choose which they would like to work with

within its outgrower scheme. Whatever the arrangement, an outgrower system should

deal with the farmers in a uniform way using the farmer organisation as a common

intermediary.

These schemes work best when the processor is actively involved in helping farmers

manage their production through advice, credit and other support, for this it is

necessary for the processor to have expertise and resources. The best known examples

come from the oil palm industry especially in South East Asia but also in West Africa

where processing mills supply farmers in schemes with seedlings, with technical

advice and provide inputs and training on credit, and may also handle harvesting and

transport of fruit from the farms. These schemes work well but are highly complex

and need a lot of expertise to manage.

A problem for many such schemes whether in West Africa or South East Asia is

„side-selling‟. This is where farmers take credit and technical support from one

processor, with whom they have a contract or some form of agreement, and then they

sell the fruit to someone else. Often this is done to avoid repaying the credit (which is

normally deducted from payments), but it may also be to get a higher purchase price

or faster payment. If this is common then it can make it impossible to recover money

invested in credit and technical support to farmers and is a common cause of collapse

for outgrower schemes set up by processors.

15

Contract farming with agri-businesses

It is an agreement between a farmer and a buyer. Contract farmers are not necessarily

supported by the factory; they should be competent to run their farms efficiently and

manage financing and technical issues themselves. Generally this applies to bigger

farms, but medium and small farms could also be contracted to supply a factory if

they are able to deliver according to the conditions of business–to-business contracts

competently. So for contract farming to work, the level of competence and business

skills of the two parties must be such that they can trust each other to stick to the

terms of their agreement.

Own production

The processor has control of its own farm and production system. This can include

forms of sharecropping arrangement where a farmer provides the land and labour but

the processing company has control of management and inputs. The key characteristic

is that the processing factory controls farm management decisions.

This approach gives a good level of control but is has some advantages and

disadvantages:

If land is hard to acquire then it may be hard to expand production.

The farm must good enough expertise in agronomic production. Most processors

lack sufficient expertise; so mush hire-in farm managers who really know how to

grow crops with low costs of production is difficult. Good farm managers with

real expertise and experience are often expensive and hard to find and recruit.

The processing company has to bear all costs of infrastructure and investment,

which may coincide with the peak of investment in the factory.

For some crops it takes a long time from starting a farm to getting large volumes

of fruit into the factory, so cash-flow calculations need to be realistic.

With a poor set-up and the wrong approach to farm management it may happen that

the production cost of the factory owned farm might be too high for the factory to

make a profit. There are several examples from West Africa where processing

factories have set up farms without checking that they can keep production costs low,

and so have lost money. However, a well managed farm can assure basic volumes to a

factory. If there is any doubt about expertise, technical performance or cost, then it is

best to plant only an acre or two and carefully measure costs and do trials and so build

experience slowly but surely. The key message for anyone interested in investing in a

processing business is: “If you do not know how to manage fruit production or do

not have partners who do, then you should probably stay out of fruit

processing.” Some factory owned farms produce enough fruit to supply a large percentage of the

factory‟s requirement. However processing businesses often have small farms that

only supply a small volume of the fruit the factory needs. However, these farms are

usually established for other purposes:

Having your own farm means you have first hand information about production

costs and about problems in managing QQT in the production system. This is very

useful when negotiating with farmers on prices and QQT issues.

16

All farm businesses need to continuously improve and test new techniques and be

able to tackle problems that arise (e.g. if a new pest or disease appears). Having

your own farm makes it possible to test new techniques and then pass on

information to the farmers who supply your factory.

The farm can be used for training your own technical field staff and also training

farmers from your outgrower scheme or for training any contract farmers.

Your own farm should be as close to your factory as possible, preferably adjacent

to it. When favourably located the farm can be used to recycle waste from the

factory. This not only solves a waste disposal problem cheaply, but may mean the

farm will not need to spend money on fertilizer. When the farm is right next to the

factory then careful spreading of waste direct onto land so that it causes no

problems can be cheaper than making compost (which is expensive to make).

A well managed farm that is profitable and generating good information for the

processor and for its suppliers projects an image of a competent and well managed

enterprise to the farmers that supply it, as well as to all other actors in the value

chain.

Planning and locating a factory

When considering the location of a new processing operation, the potential location of

the supply-base should be a key factor; as profitable factory operation is only possible

if raw material is available with the right cost and transport is a key component of the

cost at the factory gate.

It is surprisingly common to see processing operations located in urban areas. This

has a number of advantages, but it is generally much better to be as close to the

production of the raw material as possible. This has three main advantages:

1) The most important issue is that the cost of transport of fruit from farm to

factory is as low as possible; if this is too high it can change the balance

between a processing business being profitable or unprofitable.

2) The closer the processor is to its farmers, the easier it is to provide support and

supervision services. The cost and time for liaison staff getting to and from the

farms on a regular basis will be lower.

3) Production costs can be reduced through recycling factory waste back to farms

as bio-fertilizer and reduces the processor‟s waste disposal costs.

Finding a site near to an existing production zone will mean that farmer expertise in

the product to be processed; input supply and other requirements are likely to be

already available. But on the other hand there will be competition from the existing

market outlets of the farms. A new operator needs to assess the situation and decide

which one of the following options is appropriate:

establish where there is already fruit available and markets with buyers, but find

out if the farms can expand production on their own or invest money and expertise

into farms so that they can expand production through expanding their fields or

improving productivity

search for a new area where there is less competition and find farmers who want

to start producing and invest in their farms and/or set up company farms.

17

The importance of location: a comparison of two factories A fruit processing factory in Southern Africa processes 80,000 mt of fruit per year. The majority of fruit is produced close to the factory with the furthest fields 12 kilometers away. The area is flat and the road system almost perfect. The factory operates continuously and has been there since the mid 1950s. Fruit waste is sold to livestock farmers. The factory is by far the biggest employer in the area. A fruit factory in West Africa is located in the main city. Fruit has to be transported from farms to the factory from between 50 to 150 kilometers. Roads in and around the city are often congested and in rural areas where the fruit comes from, roads are poor. The cost of fruit transport adds nearly 20% to the cost of production. Disposing of the waste (50% of volume) is expensive in an urban environment. The factory was set up in the 1990s and has struggled to be consistently profitable and is often shut down. Managers blame the cost of raw material and QQT problems as the main cause of under performance of the business and employees are often paid late.

Information on areas of production

There are several examples in West Africa of factories being built to benefit from an

apparent surplus of underutilized fruit. Once the factory has been built, it turned out

that the volume of the surplus was overestimated, or that it only occurs in an

exceptional year. In Ghana for example, during the citrus harvest period buyers from

nearby countries such as Togo or Ivory Coast come into the country to buy, these

buyers are supplying very large markets so that there is seldom a crop that is so big

that it cannot be sold at all. One potential businessman planning a processing factory

was told that there are at times “thousands of tonnes of fruit rotting on the ground”.

While there may be some waste, these accounts are often exaggerated. Large amounts

of fallen fruit can be seen in all fruit producing areas of the world, but this is often

fruit dislodged by wind, and fruit that is diseased or insect-infested.

Judgment of the potential of an area also depends on understanding the crop and the

production potential. The table below shows the typical farm performance and the

potential production when farms have irrigation, use fertilizer, trees are properly

pruned and flower induction is used. Data from Brazil, a major competitor in the

mango market, show what is possible when farms are set up and managed using best

practice.

Yields of export mango

Current farmer

practice in

Mali

Improved

farms in Mali

Well-managed

farms in Brazil

Hi-tech farm

in South

Africa or Peru

Total yield

(mt/Ha/year)

3-5 12-15 25 Up to 40

Export quality 30% export

quality

70% export

quality

75% export

quality

75% export

quality

Personal communication 2010: Adama Zongo, Fruiteq, Burkina Faso.

18

Small farmers in Mali might be able to increase production from existing orchards but

this is expensive. Irrigation via a borehole with a pump and other infrastructure

requires an investment of $10-20,000. However, this can only be economic where

mango orchards are big enough to justify the investment. Therefore there are only a

limited number of places where there are enough orchards in the right place to justify

this improvement. This means that estimations of potential production can be made

only by understanding the costs and mapping the position of orchards and comparing

this with information on opportunities for installing boreholes.

Processors should be able to understand the basics of fruit production, even if they are

not intending to grow fruits themselves. They must know the investment and recurrent

costs and the risks that farmers face with their production. Only then they will be able

to know what is necessary in terms improvements to expand fruit production for a

reliable supply for their business.

Many orchards may be located in rural areas with poor roads a long way from a

proposed factory. Farms are often small and scattered. In addition many orchards may

be far away from the roadside. In the case of citrus in Ghana, the cost of moving fruit

to the roadside (usually by labourers „head-loading‟ the fruit) is a major cost for the

farmer and therefore for the value chain as a whole. Even if fruit is at the roadside, the

cost of sending a truck to pick up a small quantity can also be very high. For planning

a business, it is important to check the real cost of moving fruit from the tree to the

factory, as this may be much higher than expected and become a logistical nightmare

that the processing company will have to manage.

How cost-calculations can go wrong A company recently set up a small, but high quality oil palm mill in West Africa. They had worked out that the area had enough farmers with good quality palms to supply the factory. However, they had not considered that many of these fields were a long way from the road and this meant that the cost of harvesting had to include manually carrying the fruit to the nearest road for vehicle-transportation. This made harvesting over three times more expensive than for a large scale plantation. Harvesting is normally considered one of the biggest costs in production from mature palms. Not understanding the real situation meant that the calculations for the whole business were wrong. The mill was operated for less than a year before it had to be closed.

19

What happens if there is no secure supply-base? A West African business making dried fruit did not have a supply-base of raw material that it controlled and so it bought fruit opportunistically without any contracts from farmers. The business was located a long way from most of the farms supplying it so transport was an additional cost. Despite this it was able to calculate its expected cost-price and worked out that it could sell its products with a good profit margin. It sent samples and a quote for supplying fruit to a European importer who agreed to take an agreed monthly quantity at the quoted price. However, the processing business had trouble sourcing enough fruit at stable prices. Fruit could only be processed slowly in small batches that had to be transported from further and further away. The sale price should have left a 30% margin, but the cost of production ended up being much higher than the sale price. The importer agreed to raise the sale price to give its new business partner a chance. But the second time the European buyer was asked to do this, when deliveries were already behind schedule, they cancelled the order.

Mango and pineapple production in Ghana

This table shows estimates of actual pineapple production in Ghana

Real production (tonnes) 2006 2007 2008 2009

Total Ghana exports by sea and air 51,000 40,000 35,134 31,567

Sea-freight Pineapple Exporters of Ghana

(SPEG) exports 30,992 28,396 23,064 24,844

Number of SPEG farms exporting 22 21 15 15

This shows declining production. However, in 2006 it was predicted in a publication

that set out to showcase the growing pineapple industry that production of pineapple

in Ghana by 2009 and 2010 would have reached 116,000 tonnes and 126,000 tonnes

respectively. These data show how estimates, though prepared with good intentions,

can often be very wrong. In 2006 it looked as if the pineapple industry was going to

continue expanding rapidly. However, what actually happened was a fall in export.

Only the biggest and most professional farms survived. Large numbers of small and

medium farms stopped producing pineapple. Anyone who had used estimations of

future production in 2006 to plan a processing business would have found their

factory with little fruit to process (source: TIPCEE (USAID) 2006. Export data:

SPEG 2010).

Mapping of mango planted in Ghana provided data allowing an estimate of mango

production of 7,189mt in 2006. This figure was estimated to rise to over 57,000mt in

2010 as shown in the table below. With a projected incremental annual rise for mango

export, it was estimated that around 37,000mt mango would be available for

processing in 2010. While these data may have over-estimated production, the fact

that mango is a permanent tree crop means that processors can at least identify areas

where fruit will be produced. However, in the case of mango, relatively little has been

available for processing because of the strength of demand for fresh fruit consumption

from the local market (which has kept prices up) combined with poor farm practices

not allowing achieving optimal (high) yields.

20

Mango production estimated in 2006

(metric tonnes) 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010

Volta: Hohoe & Sogakope area 2,248 3,540 6,743 12,587 17,981

Eastern: Yilo, Manya & Asougyaman 2,351 3,703 7,053 13,166 18,808

Greater Accra: Dangme West 1,287 2,027 3,861 7,207 10,295

Brong Ahafo: Kintampo 290 457 870 1,624 2,320

Brong Ahafo: Atebubu 50 79 150 280 400

Brong Ahafo: Wenchi 38 60 114 213 304

Brong Ahafo: Techiman 25 39 75 140 200

Northern: Savelugu/Nanton 403 635 1,209 2,257 3,224

Northern: Integrated Tamale Fruit Company 900 1,418 2,700 5,040 7,200

Total 7,189 11,322 21,566 40,256 57,508

Available for local sale or processing 6,470 9,624 17,252 28,179 37,380

This is a second example of how data that appears to show that should be a lot of fruit

available as a raw material for processing can be misleading.

Managing a supply base from out-growers and contract farmers

New businesses must be prepared to work in partnership with farmers, either to help

them increase yields from existing orchards, or to establish new plantations. The

processing business will have to share in the investment cost if large amounts of fruit

are needed. If this is not done, there is a risk that the factory will have a weak supply

base with the following characteristics:

An uneven and insecure supply of raw material

Often running below break-even capacity

Constantly competing with other buyers for fruit, and so prices and costs fluctuate

widely and are uncertain.

Purchasing is unplanned and opportunistic.

Any savings made in paying a low price to farmers may be offset by the additional

cost of transporting small loads often over long distance and from having the

factory operating below capacity.

Reduced potential for gaining efficiencies by recycling waste to local contract

farms or out-growers or through improving farm production efficiency.

This results in a situation where neither the farms nor the factory can operate

optimally. When this happens, the cost of products ends up being too expensive and

unable to compete on either local or export markets. So it is necessary to plan and

make investments into the supply-base so that fruit is supplied to the factory with

QQT and cost profile that allows profitable operation. This section looks at how this

is done typically by businesses buying fruit from out-grower schemes or contract

farmers once the location of the factory has been decided.

21

A step-by-step approach to setting up a supply-base An oil palm business was set up in West Africa some years ago. It started by acquiring land and planting oil palms. It built a small ‘pilot’ factory after the first palm trees had started bearing. Two years later all the new palms were in full production the pilot factory was operating almost 24 hours per day seven days per week during the peak harvesting season. From the beginning of the project the company had started working with local farmers and by the time the pilot factory was being overwhelmed with too much fruit, the palms of the out-growers were also starting to bear. It was at this moment that the main factory was built and took over processing from the pilot factory. This meant that the main factory was not built until six years into the project. The disadvantage of having the cost of building two factories was more than compensated for by delaying the cost of building the main factory until a large enough supply-base was available to justify the investment. Now the pilot factory is still used as a back-up to take excess fruit in exceptional years during the peak months and is also used when the main factory is closed in the low season for maintenance.

Roles and responsibilities of the processing company when sourcing

from farms

Full commitment to a partnership relation with farmers is a prerequisite to a good

supply base. Many farmers in West Africa are suspicious about promises made to

them by new businesses coming into their areas. Under these circumstances it is better

to under-promise but over-deliver in what is agreed with farmers. New businesses

should be aware that it can take years of positive interaction to build a relationship

based on mutual trust.

Processors intending to buy fruit from farmers should be clear about expectations on

quality and quality parameters (what is acceptable and what is not acceptable) and

how prices will be calculated and how they will be paid. Messages on these matters

should be clear, consistent and put in writing (as well as communicated verbally).

It is strongly recommended that agreements with farmers, when these include farmers

who have little education and weak literacy skills, should be made and formalized in

writing with (literate) representatives of farmer organizations of the producers

present. These should also be explained verbally at farmer meetings in an open and

transparent way.

In many schemes the processor provides services that help farmers manage their land.

The services often involve the following:

Training and technical assistance in crop agronomy

Supplying planting material (e.g. tree seedlings etc) of the right variety and high

quality.

Field selection, soil sampling, laying out plots (for example a processor may want

to discourage farmers from establishing orchards where there is no road access

and where land is too steep).

On-farm support at planting by company technicians to ensure that

recommendations are followed

Supply of inputs, either for cash or credit.

22

Credit schemes usually linked to fruit purchasing contracts.

Monitoring visits and advisory services to farms on a regular basis.

Managing a training and demonstration farm

Scouting and checking on fruit availability and quality (e.g. helping with „D-leaf‟

weighing and de-greening in the case of pineapple).

Organizing (and sometimes paying for) harvesting teams.

Transport from the farm to the factory

Recycling of factory waste as fertilizer to the farms, sometimes through a compost

factory.

Organizing and paying for farm certification.

Coordinating support for the farmers from government agencies (e.g. for research

or extension) or from NGOs or internationally funded projects.

Helping farmers with their own business planning and cost assessment and

profit/loss calculations

Support to strengthen the capability of the farmers‟ producer associations.

Experience has shown that farmers who are provided with some services are more

reliable and more able to deliver fruit to a factory according to its needs. In ideal cases

both farmer and factory have a mutually beneficial relationship.

There should be agreements in place between each of the individual farmers and the

processor and a collective agreement between the farmer association representing

farmers and the company. Both types of agreements should be consistent with each

other and should be prepared at the same time in discussion with the farmer

association. All expected procedures and processes should be explained in detail and

any grievance procedures in the case of dispute should be formalized.

Things to avoid

Do not make promises that cannot be kept

Do not offer to buy fruit from any farmer

Do not offer to pay for transport of all fruit if you don‟t know where the

orchards are or what the real cost of transporting small volumes will be.

Do not put your own staff in positions of responsibility where they could have

conflicts of interest.

In the early years avoid promising extra benefits, such as interest free loans for

consumption (e.g. in the form of rice or other foodstuffs), or setting up savings

schemes linked to the factory). These are open to all kinds of abuse and make

the relationship more complex and more confusing than necessary.

Farmers’ responsibilities to processors and side-selling

Typical smallholder systems may be very inefficient compared to other supply

systems. Where a processor is competing with international markets, farmers should

be made aware that a processor cannot pay raw material costs (factory gate prices)

that make the factory uncompetitive. However, many farmers know little about world

prices and think that the processor can always pay a price that ensures the farmers a

profit regardless of how inefficient they are.

Farmers need to understand that contracts should be respected. Contract systems need

to be respected and if they are not then enforcement procedures need to be

23

undertaken, although this may be hard. These issues, outcomes and consequences

should be made clear in all discussions.

Respecting the role of middlemen

Organizations representing farmers should be fully aware of the reality of how value-

chains work. Often people working with farmers (including representatives of

international NGOs) will defend the position of smallholder farmers in a value chain

without being aware of other issues which are connected to the market prices and

costs along the chain.

Middlemen or intermediaries often have an important role in supplying fruit and these

people often have a lot of risk and work with relatively low margins. However, they

are sometimes dismissed as being people who exploit farmers unfairly. It is wrong to

discount their potential contribution and to accuse them of being exploitative without

being fully aware of the facts about the business of the middleman or intermediary.

Middlemen often provide transport, technical information, and give credit as well as

being traders. They are often part of the community and have long lasting

relationships with farmers. Working with middlemen can be an efficient way of

improving a value-chain (see next text box on Fruiteq‟s experience with middlemen).

Side-selling is a major problem for out-grower schemes throughout the world. Side-

selling occurs where farmers take services and credit from a company, but then sell

some of the product for cash to another buyer. This is a way for farmers to avoid

paying back the value of credit or services they have agreed to pay for. This issue

needs to be discussed openly with farmers. If the company intends to take legal action

against farmers who do side-selling, this has to be spelled out verbally and explained

clearly in contracts.

Establishing demonstration farms

If the processor has an own farm, care should be taken to set it up in the best way. It

should serve as example and demonstration to outgrower farmers. However, a good

farm is not one that gets the highest yield, but is one that produces high quality fruit

with optimum labour and land productivity while respecting social and environmental

requirements. .

The farm should be set up to be fully compliant with all certification needs so

that it can be used as a demonstration of good practice.

The company farm should ideally be within a short distance to the factory.

Efforts should be made to ensure that a legal land title can be properly

obtained.

If there are farmers using the land, proper procedures for compensation and

land acquisition in line with national law and international conventions must

be followed.

Out-grower selection

A set of criteria to guide the selection of outgrowers is required. It is advisable to

24

include people who are active members in a smallholder organization and

demonstrate commitment to their farm and their organization in the selection process.

In some cases there are farmers who are never likely to be able to keep up with the

demands that good farm management requires; and normally the farmer association as

a whole can help filter out these candidates but it is important to be clear from the

beginning that not all farmers will be able to join a scheme. It should also be clear that

the company has the final word on who can supply the factory and that bad

performers will be excluded from the scheme.

One important criterion is farm size. If, for example, a processor wants to process

10000 mt per year bought from pineapple out growers, it is much easier to work with

20 farmers who supply 500 mt each than with 200 who supply 50 mt. This assumes

that with high levels of production and good husbandry each farmer would need to

have a minimum of 15 hectares of land to be sure of keeping the number of the farmer

group below 20

GPS mapping can be used to map farms of prospective out-growers. Mapping farms

can also be used to quantify the amount of land in an outgrower scheme and to

provide evidence about the amount of tractor time or fertilizer needed, if these inputs

are provided on credit. GPS can also be used to get accurate data on the distance from

each orchard to a road.

GPS mapping can be used to check on the proximity of watercourses, forest reserves,

soil type and land steepness if these are criteria needed are important for some

certification standards (see section on certification).

If out-growers are to supply fruit from a pre-existing tree crop, for example oranges, it

is important that a crop inventory is done to record the age of the trees, the variety, the

state and condition and current farming practice. An experienced field technician will

be able to estimate actual and potential yield (if farming practices are improved). The

state and potential productivity of orchards can be used as the basis for selecting

farmers.

Technical and support services

Extension services may be supplied by the government, a qualified private service

provider working under contract to the government or the processing company itself.

Government services are usually focused on major cash crops like cocoa or food

crops like maize and cassava and are less able to work with horticultural crops.

However, it is always important to meet the district agricultural officer as they can

help with introductions to farmers and farmer associations. In most countries there is a

network of agricultural research stations and it is sensible to make contact with the

research system managers, visit the research farms and to assess the extent that a

partnership might be organized to assist farm production that might support the

processing business consolidate its supply base.

When a company is establishing its supply-base it is seldom enough to rely on

government organisations to provide extension services. A company must have the

capability of providing some services itself, either alone or in partnership with service

providers (e.g. with a competent consultant company, or within an industry

association in collaboration with other processors). Adequate resources and an

efficient technical management are essential elements. A manager with a university

25

degree but with no experience will struggle to establish a service without making

mistakes. It is important to hire someone who is a strong leader with experience in

working with farmers, but also has a good technical background and competency

level. This person should have the support and backing of a team who are energetic,

bright and motivated. Hiring the right technical team is one of the most important

factors for successful supply-base development for a processing company.

For most high-value fruit and vegetables there is often a lack of detailed and up-to-

date technical manuals. In many parts of West Africa export crops are now being

grown that have not been grown on a large scale before and are considered „exotic‟,

this means that technical recommendations may have to be worked-out by the

companies agricultural technical team. So, in addition to a good farmer services

manager, it may also necessary to seek information and expertise on what is done as

standard practice in other parts of the world as well as to be able to manage research

trials. For this it is necessary to screen the published literature on crops grown in

comparable regions, but where there is more experience and expertise.

Where a company may need to take fruit from large numbers of farmers then there are

new methods of managing communication with farmers such as using SMS text

messaging (from a single computer) to send messages to farmers and for farmers to

respond with information about their crops. These are currently tested in Ghana and

elsewhere. Even without these modern approaches, the spread of mobile phones

makes setting-up an out-grower scheme, coordinating and providing services, much

easier than in the past. In Ghana there is a tax on mobile phones that is used to fund

masts in remote places. If you are working with farmers in a place where there is poor

phone reception it may be possible to get phone companies to erect extra masts using

this fund.

Initially extension services need to organize the supply-base, but as time goes on, the

companies‟ technical teams should focus on the development of the out-growers' own

capacity to manage their farms and for services to be provided through the farmer

associations, rather than to individuals.

Financial services

Banking services may be required to process payments made by the processor to

farmers and this may also extended to the repayment of credit. The banking services

that are available in a district where a processing factory is planned should be

assessed if a large number of transactions are expected. Handling transactions though

banks ensures that there is a proper paper record of money paid and reduces the risk

of theft; farmers often appreciate using formal banking services, as handling large

amounts of cash is a security problem in some parts of West Africa. Finding a bank

that has competent branches in the area of operation is an important part of the

process of setting up an out-grower scheme. There are alternatives to banks emerging

that might also be considered; such as mobile-phone money transfers and other forms

of „branchless banking‟.

It is the responsibility of a company to make sure that payment receipts to farmers

clearly explain how payments have been calculated. Any deductions (e.g. to pay for

transport of fruit, to repay credit for fertilizer, or deductions for not meeting quality

standards such as minimum Brix level) should be clearly explained on payment

sheets.

26

If a company pays farmers later than promised it builds up a lot of resentment.

Rumours can quickly circulate that the company is not trustworthy and does not meet

its obligations. If the company intends to pay farmers only with a guarantee of

payment within, for example, one month of receiving fruit, then this should be clearly

spelled out in contracts and agreements so that there are no grounds for farmers not to

be aware of payment conditions.

Though the processor may have the final word, it is important that his decisions

should be consistent from case to case and action taken should be fair. This approach

will build up trust over time.

Newcomers to a region should also be aware that the legal and judicial systems in

many countries makes it difficult to prosecute farmers who default on the conditions

of contract or who engage in side-selling, despite agreements and contracts being in

place.

Out-grower associations

Outgrowers can be grouped in a pre-existing associations or cooperatives or, if there

is none, then a new organization can be formed. The processing company should

check that the association is properly registered and that the association has a proper

structure. In many countries there are consultancy firms providing services that can

help with the registration, coaching and organizational set-up of a farmer group.

There is a need for training on technical and administrative aspects to establish viable

self-reliant smallholder organizations. This includes training on rights and obligations,

and ensuring that farmers understand the rationale of their rights on agreements and

obligations. Farmers need to have trust and confidence in the farmer organization for

an out-grower project to function well. This needs long term and continuous training.

In some countries out-grower schemes for farmers to supply a processor should meet

basic criteria for success (see also Goldthorpe, C. G. 1995).

Associations need to meet some minimum requirements. They should:

Have a chairman, treasurer and secretary

meet regularly (e.g. monthly).

Have a constitution that outlines its purpose, financial management, criteria for

membership, rights of members and other issues.

Have criteria for membership and maintain a list of members.

Have members responsible for certain specific functions; for example for financial

control or certification support.

Be able to manage the support and services they provide to the farmers in the

association.

Have a transparent system for exit and entry to the scheme and for the association.

This should also spell out what should happen if a farmer wants to leave while he

owes money to the processor or to the association. It should be part of the

agreement between the association and the processing company.

Have clear rules that spell out how should be dealt with grievances; whether these

are between individual farmers and the company or the farmer association and the

company.

27

Working with mango middlemen in Burkina Faso, Mali and Ivory Coast

In 2005 a mango exporter was exporting not much more than one container per week

during the 12 week mango season. In 2010 it exported over 80 containers, with even

more orders for 2011. When it first started operating, it bought fruit directly from

farmers with its own staff harvesting. As it got bigger, it needed to work through

independent middlemen. These middlemen manage harvesting teams, who bring fruit

to the pack-house. They are only paid for export quality fruit. The grading is very

strict and rejected fruit is immediately returned to the middleman who brought it to

the packhouse. Before working through middlemen the exporter used their own

harvesters; at that time the quality of harvesting was bad and the reject rate was 40%.

With the middlemen taking responsibility for harvesting the rate fell to 15% or less.

The middlemen are trained in quality management by the staff of the company while

the fruit is being graded; they also handle all transport to the packhouse.

The export company pre-finances all the operations of the middlemen, but in return

has agreements that they do not work with their competitors. The fruit comes from

organic, fair-trade and GlobalGAP certified farmer associations. The exporter pays

the certification costs. The middlemen are responsible to ensure that the fruit is

separated into batches according to the farms it came from, so that traceability

required by the certification organisations is ensured.

The most successful middleman brought in 500 tonnes of export quality fruit in the

2010 season and is believed to have made a profit of between 10-15,000 Euros in 12

weeks. However, it is difficult work; he had to manage and train a large team of

harvesters making sure that they understand how to select and handle the fruit. He had

to pay the farmers, hire trucks and organize logistics. This has to be done perfectly in

order to get a good margin. Many inefficient middlemen do not make money and drop

out of the business. The export company meets with the middlemen regularly through

the seasons to analyze prices and costs so that they can make sure that the middlemen

are able to make a profit. If this is not possible then exports are stopped. To meet the

conditions of FLO (fair-trade) certification, the price middlemen pay to farmers has to

be above a minimum floor price so the company and the middlemen and the farmers