Clavio, il cosmo, il tempo, in Magistri astronomiae dal XVI al XIX secolo, catalogo della mostra,...

Transcript of Clavio, il cosmo, il tempo, in Magistri astronomiae dal XVI al XIX secolo, catalogo della mostra,...

Galileo: “tanti oggetti nobilissimi et occulti”

Nel novembre 1609, quando, puntando il te-lescopio verso il cielo, trasformò un giocattoloolandese in uno strumento astronomico, cam-biando per sempre il modo di vedere e di imma-ginare il cielo, Galileo aveva 46 anni e un oscu-ro curricolo (FIG. 1).

Nato a Pisa nel 1564, aveva alle spalle studi dimedicina presto interrotti e una già lunga carrie-ra di matematico. Nella prima età moderna era,questa, una professione niente affatto prestigio-sa o remunerativa. Tra i professori universitari imatematici erano tra i meno pagati, una condi-zione sociale che rispecchiava lo status episte-mologico della materia. Nella gerarchia dei sa-peri tracciata da Aristotele e rimasta in vigore at-traverso il Medioevo, la disciplina era subordi-nata alla filosofia e alla teologia, in maniera ta-le che essa non poteva in alcun modo trattare ladimensione fisica dei fenomeni naturali. Per dipiù, essa aveva a che fare con la meccanica e lemacchine, materia da schiavi, che non si addice-va, come invece la filosofia, a uomini liberi.

Malgrado ciò, Galileo aveva perseguito la suastrada con passione e determinazione. Dopo averseguito le lezioni di Ostilio Ricci nell’Accademiadel disegno di Firenze e dopo alcuni anni di in-segnamento privato e di studio originale della tra-dizione (Euclide, Archimede, centrobarica, idro-statica), nel 1589 era stato chiamato all’Univer-sità di Pisa. Vi era rimasto dal 1589 al 1591, pre-sto insofferente allo scarso stipendio, alle cattivecondizioni di lavoro e al clima culturale spento econservatore della città e dello Studio (che ave-va pure satireggiato in un poemetto intitolatoContro il portar la toga).

31

CLAVIO, IL COSMO, IL TEMPO

FEDERICA FAVINO *

CLAVIUS, THE COSMOS, THE TIME

FEDERICA FAVINO *

Galileo: “many highest and hidden objects”

In November 1609, when Galileo pointed histelescope at the sky – turning a Dutch toy intoan astronomical instrument and changig foreverthe way of seeing and imagine the universe – hewas already 46 year-old and an hardly knownmathematicians (FIG. 1).

He was born in Pisa in 1564, had given uphis early medical studies, and had already beena mathematician for a long time. In the firstmodern era, this was not a prestigious or wellpaid profession at all. Mathematicians were thelowest-paid of all university professors, a so-cial status that reflected the epistemologicalstanding of the subject. In the hierarchy ofknowledge outlined by Aristotle and still fol-lowed throughout the Middle Ages, this disci-pline was subordinate to philosophy and the-ology to the extent that it was prevented fromcommenting upon the physical dimensions ofnatural phenomena. Moreover, mathematicshad to do with mechanics and machines, mat-ter of slaves, unlike philosophy which was bet-ter suited to free men.

In spite of this, Galileo followed his path withpassion and determination. After attending class-es with Ostilio Ricci in the Accademia del dis-egno in Florence and after a few years of privatetuition and of critical exam of the traditionaltextbooks (Euclid, Archimedes, centrobarics, hy-drostatics), in 1589 he obtained a lectureship atthe University of Pisa. He spent two years therefrom 1589 until 1591, quickly losing patiencewith the meagre salary, the poor working con-ditions and the uninspiring and conservative cul-tural atmosphere of the city and its academic life

� Jan Vermeer, L’Astronomo, (1668) olio su tela. Parigi, Musée du Louvre.Jan Vermeer, The Astronomer, (1668) oil on canvas. Paris, Musée du Louvre.

duti ovunque in Europa. Il doge e i senatori diVenezia, ai quali egli offrì uno strumento capacedi mostrare dall’alto del campanile di San Mar-co “vele e vasselli in mare” con un anticipo didue ore rispetto alla loro visione ad occhio nudo(FIG. 2) gli conferirono in cambio una nomina avita alla cattedra di matematica dello Studio diPadova, con uno stipendio record di 1000 fiori-ni l’anno. Non bastava ancora. Allo scopo di ot-tenere la protezione del suo sovrano per nascita,il Granduca di Toscana, e di tornare a Firenze,Galileo decise di dedicare a Cosimo II de’ Medi-ci il Sidereus Nuncius (marzo 1610), il libretto incui dava conto delle scoperte astronomiche che,grazie all’uso del suo cannocchiale, aveva com-piuto tra gli ultimi mesi del 1609 e i primi del1610.

Puntato al cielo, il suo telescopio aveva infat-ti rivelato fenomeni straordinari: in aperto con-trasto con la tradizione aristotelica che voleva icorpi celesti perfettamente sferici e levigati, la su-perficie lunare, osservata al cannocchiale, pre-sentava avvallamenti e protuberanze. Era facilepoi dimostrare che i punti luminosi osservabilinella parte oscura del disco lunare in prossimitàdel terminatore (la linea di separazione tra la par-

rope. He presented to the Doge and senatorsof Venice a telescope which from the top ofSaint Mark’s belltower showed “sailboats andvessels in the sea” two hours before they couldbe spotted with the naked eye (FIG. 2). In re-turn he was appointed to the chair of mathe-matics for life at Padua, with a record salaryof 1000 fiorini per year. But this still wasn’tenough. In order to gain the patronage of hissovereign by birth, the Grand Duke of Tuscany,and to return to Florence, Galileo decided todedicate to Cosimo II de’ Medici his pamphletSidereus Nuncius (March 1610), in which hegives an account of the astronomical discover-ies made with his telescope between late 1609and early 1610.

By pointing his telescope at the sky he haddiscovered extraordinary phenomena: in com-plete contrast to the Aristotelian tradition thatheld that celestial bodies were perfectly smoothand spherical, the surface of the moon, whenobserved through the telescope, showed hol-lows and protuberances. It was easy to demon-strate that the light spots seen in the dark partof the moon’s disc close to the terminator (theboundary between the illuminated part and the

33

(which he even satirized in a short poem, Againstthe wearing of the toga).

In 1592, he managed to be transferred to theUniversity of Padua, where he spent, as he him-self notes, “the eighteen best years of my life”.He earned more the longer he served, and sup-plemented his earnings through private tuition,by offering board and lodging to students, as wellas through the sale of instruments and tools, suchas geometric and military compasses, that hemade in the workshop attached to his house. InPadua and Venice he also had an opportunity tofrequent the salons – such as those of GiovanVincenzo Pinelli or Antonio Quarenghi – wheremany of the most erudite Europeans both localand foreign met. And it was in these very set-tings where his support of a heliocentric view de-veloped and matured, arising from his astro-nomical and cosmological research, closelybound up in those years with his studies on themotion of falling bodies.

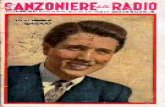

However, this was not enough for Galileo. Hewanted to find a patron so that he could stopteaching and use his time to complete what he

considered his “great”works (Dialogue con-cerning the two chiefworld systems andDis-courses and Mathe-matical Demostrationsrelating to two newsciences). An opportu-nity arose in the sum-mer of 1609 when helearned in Venice that“a certain Flemish manhad made an eye-glass,through which visibleobjects, however dis-tant from the observ-er’s eyes, could be seenclearly as if they wereclose”. In a very shorttime and without anyparticular knowledgeof optics, Galileo man-aged to develop amuch more powerfultelescope than any ofthe other models thathad been made andsold throughout Eu-

32

Nel 1592 aveva cercato ed ottenuto il trasferi-mento all’Università di Padova, dove avrebbetrascorso – come ebbe poi a ricordare – “li di-ciotto anni migliori della mia vita”. Lo stipendioera cresciuto con l’anzianità di servizio, con i pro-venti dell’insegnamento privato e degli studentia pensione, e con i guadagni derivati dalla ven-dita degli strumenti e dei dispositivi che costrui-va nella bottega attigua alla sua abitazione (co-me il compasso geometrico e militare). A Pado-va e a Venezia egli aveva inoltre avuto la possi-bilità di frequentare i salotti – come quello di Gio-van Vincenzo Pinelli o di Antonio Quarenghi –in cui si riunivano eruditi locali e stranieri, tra iprimi d’Europa. Ed era proprio in questi ambientiche egli era andato maturando una consapevoleadesione alla teoria eliocentrica, nata nell’ambi-to di ricerche astronomico-cosmologiche stretta-mente intrecciate a quelle degli stessi anni sul mo-to e sulla caduta dei gravi.

Per Galileo, però, tutto questo non era ancoraabbastanza. Il suo intento, infatti, era quello ditrovare un mecenate che gli consentisse di lasciarel’insegnamento e di usare il suo tempo per com-pletare quelle che con-siderava le sue opere“grandi” (il Dialogosopra i due massimi si-stemi del mondo e iDi-scorsi e dimostrazionimatematiche intorno adue nuove scienze).L’occasione gli si pre-sentò nell’estate 1609,quando a Venezia sivenne a sapere che «uncerto Fiammingo avevafrabbricato un occhia-le, mediante il quale glioggetti visibili, perquanto molto distantidall’occhio dell’osser-vatore, si vedevano di-stintamente come fos-sero vicini». In brevetempo, infatti, e senzaparticolari cognizionidi ottica, Galileo riuscìa mettere a punto untelescopio assai più po-tente di tutti quelli al-lora fabbricati e ven-

Fig. 1. Ottavio Leoni, Ritratto di Galileo Galilei, disegno,1624. Firenze, Biblioteca Marucelliana.Fig. 1. Ottavio Leoni, Portrait of Galileo Galilei, drawing,1624. Florence, Biblioteca Marucelliana.

Fig. 2. Luigi Sabatelli, Galileo presenta il telescopio al Senato veneziano radunato sul campanile diSan Marco a Venezia, 1840, affresco. Firenze, Palazzo Torrigiani, Tribuna di Galileo.Fig. 2. Luigi Sabatelli, Galileo presents the telescope to the Venetian Senate on the Saint Mark’s belltowerin Venezia, 1840, fresco. Florence, Palazzo Torrigiani, Tribuna di Galileo.

bili all’internodella manieratradizionale diconcepire l’uomoe il cosmo. Esse,infatti, smenti-vano la millena-ria convinzionenella eterogenei-tà sostanziale dimateria celeste emateria terrestre(non era forse laLuna identica al-la Terra?); pre-mettevano di im-maginare un uni-verso potenzial-mente infinito;rafforzavano lacredibilità dellateoria eliocentri-ca (di cui il siste-ma Giove-satelli-ti offrivano un modello), minacciando, in questomodo, le basi stesse della visione antropocentri-ca e finalistica dell’Occidente cristiano (FIG. 4).

L’assenso sulla verità delle osservazioni tele-scopiche era dunque il primo passo da compiereper persuadere chi deteneva allora il controllo del-le istituzioni culturali, essenzialmente la Chiesa,a recepire e veicolare una proposta cosmologica,ma anche antropologica, alternativa a quella of-ferta dall’aristotelismo e ratificata dai dogmi ec-clesiastici. Nel marzo 1611, Galileo progettò ecompì un lungo soggiorno a Roma (cfr. schedan. 3), per convincere i membri della corte e del-la Curia del papa Paolo V a modificare il loropunto di vista personale e ufficiale, ma prima an-cora coloro che rappresentavano allora la più au-torevole fonte locale di autorità tecnica (ancheper le congregazioni ecclesiastiche): CristoforoClavio e i matematici del Collegio Romano del-la Compagnia di Gesù (FIG. 5).

Non era questa la prima volta che Galileo ri-correva all’autorevolezza di Clavio per consoli-dare la sua reputazione. Dopo averlo conosciutonel 1587, in occasione del suo primo soggiornoromano ed essendo allora alla ricerca di un la-voro, aveva cercato dal gesuita – onorato dai con-temporanei come «l’Euclide dei tempi nostri» –una valutazione sui propri studi sul centro di gra-

and the cosmos.They belied thethousand yearold belief in thesubstantial het-erogeneity of ce-lestial matter andearthly matter(the moon iden-tical to the earth,isn’t it?); they of-fered a glimpseof a potentiallyinfinite universe;they reinforcedthe credibilityof the heliocen-tric theory (withJupiter’s satellitesystem providinga model), thusthreatening thevery foundationsof the Western

Christian finalist and anthropocentric view(FIG. 4).

Consensus regarding the truth of the tele-scope observations was therefore the first stepin persuading those who controlled the cultur-al institutions of the time – essentially theChurch – to accept and disseminate a cosmo-logical (but also anthropological) theory as analternative to the Aristotelian one and ratifiedby ecclesiastic dogma. In March 1611, Galileowent on an extended visit to Rome (cf. cata-logue no. 3) to persuade the members of thecourt and the Curia of Pope Paul V to changetheir personal and official point of view; evenmore important for him was to persuade thehighest local scientific authority (also for theecclesiastical congregations): Christopher Clav-ius and the mathematicians of the Collegio Ro-mano of the Society of Jesus (FIG. 5).

It was not the first time Galileo had lookedto Clavius’ authority to consolidate his repu-tation. After meeting him in 1587 during hisfirst visit to Rome, Galileo had asked Clavius– honoured by his contemporaries as the “Eu-clid of our times” – to evaluate his studies onthe centre of gravity in solids. Looking for ajob, the scientist thought that Clavius’ state-ment on his own work would have worked as

35

te illuminata e quellain ombra), non eranoaltro che la cima dimontagne del tutto si-mili a quelle presentisulla crosta terrestre(cfr. scheda n. 2). Ga-lileo aveva poi scoper-to l’esistenza di unaquantità di stelle benmaggiore di quelle os-servabili a occhio nu-do (80 nella sola co-stellazione di Orione) eaveva potuto chiarirela vera natura della viaLattea: un ammasso diinnumerevoli stelle,impossibili da distin-guere singolarmente aocchio nudo. Nel gen-naio 1609 aveva poiscoperto quattro astriin rotazione attorno aGiove che egli, inomaggio ai suoi futuripadroni, aveva chia-mato “pianeti medicei” (FIG. 3). Alla fine di lu-glio 1610, – il Messaggero delle Stelle era già inlibreria – aveva osservato “un’altra stravagan-tissima meraviglia”: l’apparenza di Saturno co-me un corpo sferico centrale affiancato da duepiccoli globi laterali (“l’anello” per come si po-teva presentare ad un telescopio a bassa risolu-zione). E nel dicembre successivo – quando si eragià trasferito a Firenze come “matematico e fi-losofo del Granduca”, con lo stipendio di millescudi annui, senza obblighi di insegnamento econ la possibilità di pronunciarsi, in quanto fi-losofo, sulla dimensione fisica della realtà – ave-va annunciato alla comunità scientifica, per mez-zo di un complesso anagramma, una clamorosascoperta astronomica: esattamente come la Lu-na, il pianeta Venere presenta delle fasi. La sco-perta presentava importanti implicazioni co-smologiche: il pianeta, infatti, in base alla posi-zione che gli spettava nello schema tolemaico,non avrebbe mai potuto mostrare ad un osser-vatore posto sulla Terra l’intera gamma delle fa-si, come invece accadeva.

Si trattava di osservazioni suffragate dalla “sen-sata esperienza” della vista e tuttavia inammissi-

dark part of themoon), were nothingmore than the sum-mits of mountains justlike those found onthe earth’s surface(cf. catalogue no. 2).Galileo then went onto discover the exis-tence of a much larg-er number of starsthan could be seenwith the naked eye(80 just in the con-stellation of Orion)and had discoveredthe true nature of theMilky Way – a massof countless stars, im-possible to make outindividually with thenaked eye. In January1609, he discoveredfour stars orbitingaround Jupiter whichhe called the “Mediceanplanets” after his fu-

ture employers (FIG. 3). By the end of July 1610– the Messenger of the Stars was already inbookshops – he had observed “another moststrange marvel”: the appearance of Saturn as acentral spherical body flanked by two small lat-eral globes (“the ring” as seen through a lowresolution telescope). And the following De-cember – when he had already moved to Flo-rence as “the Grand Duke’s mathematician andphilosopher”, with a salary of a thousand scu-di per year, no teaching duties and an oppor-tunity to comment, insofar as he was a philoso-pher, on the physical dimensions of reality – hehad announced to the scientific community, bymeans of a complex anagram, an astonishingastronomical discovery: the planet Venus hadphases exactly like the moon. The discovery hadimportant cosmological implications: in fact,based on its allocated position in the Ptolema-ic system, Venus would never have been ableto show to an observer positioned on earth thefull range of the that it actually showed.

These observations were supported by the“sense experiences” of seeing and yet were inad-missible in the traditional way of conceiving man

34

Fig. 3. Galileo presenta il suo telescopio alle Muse, antiportain Opere di Galileo Galilei, 2 voll., Bologna 1655-56.Fig. 3.Galileo presents his telescope to theMuses, frontispiecein Opere di Galileo Galilei, 2 vol., Bologna 1655-56.

Fig. 4. Esempio di cartografia lunare inaugurata dal Sidereus Nuncius diGalilei (da J. Hevelius, Selenographia, sive Lunae descriptio. Danzig 1647).Fig. 4. Example of lunar cartography begun by Sidereus Nuncius of Galilei(from J. Hevelius, Selenographia, sive Lunae descriptio. Danzig 1647).

«l’Euclide dei tempi nostri»

Clavio (FIG. 6) aveva allora 73 anni (era natoa Barberga, in Franconia, nel 1538), 40 dei qua-li trascorsi nella città del papa. Vi era giunto nel1561, subito dopo avere conseguito la laurea infilosofia nel Collegio gesuitico di Coimbra, e dal1565 (l’anno prima aveva preso gli ordini sa-cerdotali) vi teneva l’insegnamento della mate-matica.

Negli anni passati, Clavio aveva condotto unadura battaglia all’interno dell’Ordine per accre-scere l’importanza delle matematiche nell’offer-ta formativa dei collegi gesuitici e dare così aisuoi membri gli strumenti per intervenire (conl’insegnamento o con la ricerca) anche sul terre-no della scienza. Aveva così ottenuto l’introdu-zione nella Ratio studiorum di un corso di ma-tematica obbligatorio per tutti i seminaristi el’istituzione di un’accademia superiore di mate-matiche riservata a un’élite di studenti prove-nienti da tutte le province della Compagnia e de-stinati poi a disper-dervisi. La sua catte-dra fu il centro dacui si sprigionaronoforze e saperi capacidi penetrare capillar-mente nella società ascala nazionale, eu-ropea e perfino glo-bale (Matteo Riccifu tra i suoi allievi)già nel corso di unagenerazione.

Questo progettopedagogico dominòanche tutta la sua at-tività editoriale. Nelcorso della sua lungaattività, pubblicò ungran numero di ope-re, non prive di ori-ginalità, ma espres-samente elaborateper munire le scuoledella Compagnia diGesù dei manuali ne-cessari all’insegna-mento di tutte lebranche della disci-plina.

“the Euclid of our time”

In 1611 Clavius (FIG. 6) was 73 (he was bornin Barberg, in Franconia in 1538), and had spent40 years in the papal city. He came to Rome in1561, immediately after gaining a degree in phi-losophy from the Jesuit College of Coimbra, andfrom 1565 (a year after taking holy orders) hetaught mathematics.

In previous years, Clavius had fought hardwithin the Order to raise the profile of mathe-matics in the curriculum of the Jesuit colleges andthus give its members the instruments to partic-ipate (through teaching or research) also in thefield of science. Through his efforts a mathe-matics course, compulsory for all the seminar-ists, was added to the Ratio studiorum and anadvanced academy of mathematics was createdfor the top students from all the provinces of theOrder. His lecture hall was the centre from whichenergy and knowledge radiated to penetrate deepinto society on a national, European and even

global scale (MatteoRicci was one of hispupils) already in thecourse of a genera-tion.

This educationalproject also domi-nated his publishingactivities. In thecourse of his long ca-reer, he published agreat number ofworks, not withoutoriginality, but ex-pressly developed toequip the schools ofthe Society of Jesuswith the necessaryteaching textbooksfor all branches inthe discipline.

Following his rig-orous commentaryon Euclid’s Elements(1574), in 1583 hepublished the Epi-tome arithmeticaepracticae, with manyre-editions, whichincluded an exposi-

37

vità dei solidi che gli valesse come un attestato divalore presso la comunità scientifica nazionale;tanto era il credito di cui Clavio godeva allorapresso i contemporanei. Partito da Padova, e ve-nutogli quindi meno l’impedimento di trattare coni gesuiti dovuto all’Interdetto, nell’autunno del1610 si era subito affrettato a rompere il silen-zio che lo aveva tenuto per anni lontano dal ge-suita. Lui, così restio a stringere relazioni episto-lari con il protestante Keplero, non esitava inve-ce ad insistere affinché il gesuita Clavio appog-giasse l’occhio al suo telescopio ed accreditassele sue scoperte presso la comunità cattolica uni-versale.

a recommendations into the national scientificcommunity, as the Jesuit was held in such highregard among his contemporaries at the time.Having left Padua, and therefore escaped therestrictions of the Interdict, in the autumn of1610 he hastened to break the silence that hadfor years kept him at a distance from the JesuitClavius. Galileo, who was so unwilling to cor-respond with the protestant Kepler, did not hes-itate to exhort Clavius to look through his tel-escope and confirm his own discoveries to theuniversal Catholic community.

36

Fig. 6. Anonimo, Cristoforo Clavio, XIII secolo. Roma, Bibliotecadella Pontificia Università Gregoriana.Fig. 6. Anonymous, Cristoforo Clavio, 13th century. Rome,Library of Pontifical Gregorian University.

Fig. 5. Giuseppe Vasi, Prospetto principale del Collegio Romano, stampa 1761. Roma, Archivio storico della PontificiaUniversità Gregoriana, Fondo stampe.Fig. 5. Giuseppe Vasi, Prospetto principale del Collegio Romano, print 1761. Rome, Historical Archives of the PontificalGregorian University, Print collection.

tolemaica (FIG. 8) e un fiero oppositore dell’ipo-tesi eliocentrica, che considerava assurda, “in di-saccordo con la dottrina dei filosofi e degli astro-nomi” e contraria alle cose “che le sacre scrittu-re insegnano in molti luoghi”. D’altro canto, eglifu un tipico rappresentante dell’Aristotelismo ri-nascimentale: tentò, cioè, di mantenere in piediun sistema fondamentalmente aristotelico maadattato, per così dire, alle nuove scoperte astro-nomiche. Ne è un esempio il modo in cui, nel-l’edizione del 1581, spiegò la “nuova stella” ap-parsa nel 1572 nella costellazione di Cassiopea(in realtà una ‘supernova’), che egli aveva osser-vato dal Collegio Romano. Tra l’auctoritas di Ari-stotele, che pretendeva i cieli immutabili, e i da-ti forniti dall’osservazione, egli scelse una via dimezzo: il nuovo astro, non c’era dubbio, era si-tuato proprio nel cielo delle stelle fisse (non eracioè una cometa effimera e neppure una delle stel-le di Cassiopea mai osservata prima, come altricredevano); le sostanze celesti, pertanto, non è ve-

the other hand, he was a typical representativeof Renaissance Aristotelianism: that is, he at-tempted to maintain the fundamentally Aris-totelian system but adapting it to the new as-tronomical discoveries. The way he explained the“new star” which appeared in 1572 in the con-stellation of Cassiopeia (actually a “supernova”)and which he had observed from the CollegioRomano, is an example of this. He navigated amiddle way between the auctoritas of Aristotle,who held thate the heavens were immutable, andthe data provided by the observations: the newstar was without a doubt situated in the sphereof the fixed stars (that is, it was not an ephemer-al comet and nor was it one of Cassiopeia’s starsthat had never before been observed, as othersbelieved); therefore it was not true that celestialmatter was not corruptible, but, according toClavius, it was less corruptible than those in theelementary sphere. In the same way he then ex-plained the appearance of novae in 1600 and

39

Dopo un rigorosocommento agli Ele-menti di Euclide(1574), nel 1583 pub-blicò la Epitome ari-thmeticae practicae,con molte riedizio-ni, che comprendeval’esposizione di tuttal’aritmetica dei numeriinteri e frazionari (peri quali introdusse lamoderna notazione),oltre alla presentazionedelle regole utili per larisoluzione dei variproblemi posti dallapratica. Nel 1604 fu lavolta della Geometriapractica – in cui, a par-tire dalla descrizionedegli strumenti di mi-sura, illustrava la solu-zione trigonometrica diproblemi di topografiae geodesia – e nel 1608quella dell’Algebra,un’esposizione dell’in-tera algebra dei nume-ri interi, razionali e ir-razionali, apprezzata intutta Europa.

Grande diffusione ebbe soprattutto il suo InSphaeram Ioannis de Sacro Bosco commentarius(1570) (FIG. 7), che conobbe ben sette edizioni ri-vedute e corrette (anche Galileo la utilizzava peri suoi corsi universitari) per un totale di sedici ri-stampe. L’opera consisteva in un’esposizione ecommento di quello che era allora il testo baseper l’insegnamento dell’astronomia nelle univer-sità e nei collegi: il trattato De Sphera mundi.Scritto nel XIII secolo dall’inglese Giovanni di Sa-crobosco (John of Holywood), si trattava a suavolta di una riesposizione elementare delle dot-trine dell’Almagesto di Tolomeo e del compendioche ne aveva fatto Alfragano.

L’evoluzione del testo della Sfera di Clavio nel-le diverse edizioni rispecchia chiaramente la suavisione dell’astronomia e le sue trasformazioni.Come astronomo teorico, vuoi per la sua forma-zione culturale, vuoi per il suo stato di religioso,Clavio fu un convinto assertore dell’astronomia

tion of the arithmeticof whole numbers andfractions (for which heintroduced the modernnotation), in additionto rules for solving var-ious problems arisingfrom practical applica-tions. In 1604 cameGeometria practica.Based on the descrip-tion of measuring in-struments, he illustrat-ed the trigonometricsolution to topograph-ic and geodesic prob-lems. In 1608 Algebrawas in print an exposi-tion of the algebra ofwhole rational andirrational numbers,much praised through-out Europe.

His commentary onJohn of Holywood’sspheres (In SphaeramIoannis de Sacro Boscocommentarius, 1570)(FIG. 7) was particularypopular (Galileo alsoadopted it for his uni-

versity courses), running to seven revised and cor-rected editions and sixteen reprints. The bookconsisted of an exposition of and commentaryon what was then the fundamental textbook forthe teaching of astronomy in the universities andcolleges, De Sphera mundi. Written in the 13thcentury by the Englishman John of Holywood,De Sphera was an elementary exposition of thedoctrines of Ptolemy’s Almagest and Alfragan’scompendium based on it.

Changes in the text of Clavius’s Spheres overits various editions clearly reflects his view of as-tronomy and the evolution of his ideas. As a the-oretical astronomer, whether due to his culturalbackground, or his religious vocation, Claviuswas firmly on the side of the Ptolemaic system(FIG. 8), firmly opposing the heliocentric hy-pothesis, which he considered absurd, “in dis-agreement with the doctrine of philosophers andastronomers” and contrary to the things “thatthe sacred scriptures teach in many places”. On

38

Fig. 7. Cristoforo Clavio, In Sphaeram Ioannis de SacroBosco commentarius, frontespizio, Roma 1570. Roma,Biblioteca dell’Osservatorio Astronomico di Roma.Fig. 7. Cristophorus Clavius, In Sphaeram Ioannis de SacroBosco commentarius, frontispiece, Rome 1570. Rome,Library of the Astronomical Observatory of Rome.

Fig. 8. Andreas Cellarius, Orbium Planetarum Terram Complectentium Scenographia (da HarmoniaMacrocosmica Seu Atlas Universalis Et Novus, Totius Universi Creati Cosmographiam Generalem,Et Novam Exhibens, Amsterdam 1661).Fig. 8. Andreas Cellarius, Orbium Planetarum Terram Complectentium Scenographia (fromHarmoniaMacrocosmica Seu Atlas Universalis Et Novus, Totius Universi Creati Cosmographiam Generalem,Et Novam Exhibens, Amsterdam 1661).

Clavio e il tempo

Clavio compose molti altri libri sulla geome-tria della sfera (ad esempio, un commento allaSfera di Teodosio Tripolita, I a.C.) e sul complessodelle discipline inerenti l’astronomia, come lagnomonica e la costruzione di strumenti per lamisurazione del tempo e della posizione degli astri(Gnomonices libri octo […], 1581; Fabrica et ususinstrumenti ad horologiorum descriptionem pe-ropportuni, 1586; In Astrolabium Lemmata,1593; Horologiorum nova descriptio, 1599 e ilCompendium brevissimum describendorum ho-rologiorum […], 1603) (cfr. scheda n. 4). Anchequesti libri-guida erano in qualche modo conce-piti per servire all’apostolato della Compagnia nelcampo dell’istruzione. L’astrolabio, ad esempio,era allo stesso tempo uno strumento per facilita-re il calcolo e un modello didattico (vale a direuno strumento per simulare la configurazione del-la volta celeste in un determinato momento), e lemeridiane un interessante settore di impiego pergiovani matematici. D’altro canto, la connota-

Clavius and time

Clavius wrote many other books on the geom-etry of the sphere (for example, a commentaryon Sphaerics by Theodosios of Bithynia, 1 BC)and on the disciplines related to astronomy, suchas gnomonics and making instruments for meas-uring time and the position of the stars (Gno-monices libri octo […], 1581; Fabrica et usus in-strumenti ad horologiorum descriptionem per-opportuni, 1586; In Astrolabium Lemmata,1593); Horologiorum nova descriptio, 1599, andCompendium brevissimum describendorumhorologiorum […], 1603) (cf. catalogue no. 4).In a way, these guides were designed as aids tothe Jesuit’s educational ministry. The astrolabe,for example, was both an instrument to facili-tate calculation and a teaching aid (that is, aninstrument for simulating the configuration ofthe skies at a given time), while the meridianswere an interesting area of application for youngmathematicians. On the other hand, the emi-nently practical connotations of Clavius’s stud-

41

ro che non siano corruttibili, ma sono meno cor-ruttibili – così spiegava il gesuita – di quelle del-la sfera elementare. Allo stesso modo spiegò poile novae apparse nel 1600 e nel 1604, che osser-vò a Roma con i suoi studenti da tetti e terraz-ze, con l’aiuto dei suoi strumenti portatili (astro-labi, quadranti, globi celesti).

Nel 1610, Clavio accolse inizialmente le nuo-ve scoperte telescopiche con un certo scetticismo.«Questi Clavisi – scriveva ai primi di ottobre daRoma il pittore Ludovico Cardi da Cigoli – chesono tutti, non credono nulla; et il Clavio fra glialtri, capo di tutti, disse a un mio amico, dellequattro stelle, che se ne rideva, et che bisognieràfare uno occhiale che le faccia e poi le mostri, etche il Gallileo tengha la sua oppinione et egli terràla sua». Al contrario, già ai primi di dicembre egliscriveva allo scienziato tributandogli grandi lodi,avendo potuto osservare “distintissimamente”(grazie ad un più potente telescopio) i satelliti diGiove, alcune stelle “nelle Pleiadi, Cancro, Orio-ne et Via Lactea”, la figura allungata di Saturnoe, sempre con grande meraviglia, “l’inequalità etasprezza» della Luna «quando non è piena”.

La sua convinzione nella certezza delle osser-vazioni telescopiche si rafforzò durante i ripetu-ti incontri che egli, insieme ai suoi allievi, ebbe aRoma con Galileo nella primavera del 1611. In-sieme a loro (Christopher Grienberger, Odo VanMaelcote, Giovanni Paolo Lembo) ebbe anche oc-casione di rendere pubblica la sua attestazione difiducia nella veridicità dei dati osservativi pro-posti da Galileo, in un parere ‘ufficiale’ richiestoallora dal cardinale gesuita Roberto Bellarmino.Il quella risposta, Clavio concordava con i suoiallievi sulla figura di Saturno, le fasi di Venere ei satelliti di Giove (anche se non sulle loro im-plicazioni cosmologiche) e ne condivideva la cau-tela a proposito della natura della Via Lattea. Sene dissociava invece riguardo alla composizionedel corpo lunare, secondo lui non realmente sca-bro e accidentato, ma piuttosto composto di par-ti di diversa densità. Si trattava, ancora una vol-ta, di una posizione di compromesso, per non ab-bandonare l’idea aristotelica di una gerarchia me-tafisica entro l’universo. Allo stesso tempo, però,nell’ultima edizione della Sphera, edita a Meinznella sua Opera mathematica proprio nel 1611,Clavio dava conto delle scoperte galileiane ed am-moniva gli astronomi a riconsiderare la disposi-zione delle stelle e dei pianeti, in modo da ren-derla compatibile con esse.

1604, which he observed with his students onthe roofs and terraces in Rome, using portableinstruments (astrolabes, quadrants, celestialglobes).

In 1610, Clavius was initially quite skepticalabout the telescope discoveries: “These follow-ers of Clavius – wrote the painter Ludovico Car-di da Cigoli in Rome at the beginning of Octo-ber – don’t believe any of it; and among themClavius, head of them all, told a friend of mineof the four stars, while laughing, that a specialtelecope would have to built which would cre-ate the stars and then reveal them, and thatGalileo can keep his opinion and he will keephis”. In contrast, by early December he had writ-ten to the scientist full of praise that he had beenable to observe “most clearly” (thanks to a morepowerful telescope) Jupiter’s satellites, a few stars“in the Pleiades, Cancer, Orion and the MilkyWay”, the stretched shape of Saturn and, to hisgreat wonder, “uneveness and harshness” of themoon “when it isn’t full”.

His belief in the reliability of the observationsvia telescope was reinforced during frequentmeetings between himself and his pupils withGalileo in Rome in the spring of 1611. He andhis pupils (Christopher Grienberger, Odo VanMaelcote, Giovanni Paolo Lembo) also had anopportunity to make public a testimonial as tothe veracity of the observed data proposed byGalileo, in an ‘official’ opinion requested by theJesuit Cardinal Roberto Bellarmino. In re-sponding to the cardinal, Clavius agreed withhis pupils regarding Saturn, the phases of Ve-nus and Jupiter’s satellites (even if there was noagreement on their cosmological implications)and he shared their cautious approach to thecomposition of the Milky Way. He did, howev-er, disassociate himself from opinions regardingthe compositoin of the moon, the surface ofwhich he thought was not really rugged and un-even, but rather composed of areas of differentdensity. Once again, his was a position of com-promise, dictated by reluctance to abandon theAristotelian idea of a metaphysical hierarchy inthe universe. At the same time, however, in thelast edition of the Sphera, published in Mainzin his Opera mathematica in 1611, Clavius tookaccount of Galileo’s discoveries and advised as-tronomers to reconsider the arrangement of thestars and the planets, in order to ensure its com-patibility with them.

40

Fig. 9. Anonimo italiano, Papa Gregorio XIII presiede la Commissione per la riforma del Calendario romano (1582-1583), XVI secolo. Siena, Archivio di Stato di Siena.Fig. 9. Anonimous, Pope Gregory XIII officiates the Commission for the Reform of the roman Calendar (1582-1583),16th century. Siena, Archivio di Stato di Siena.

no per convergere i pa-reri di tutti.

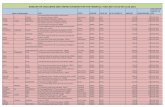

I lavori procedetteroin fasi diverse. Alla finedel 1577, la Commis-sione elaborò un com-pendio del progetto diriforma che il papa in-viò, per mezzo dei nun-zi pontifici, ai principi ealle Università del mon-do cattolico, affinchéquesti a loro volta lomandassero ai matema-tici più competenti neiloro territori. Sulla ba-se dei pareri così otte-nuti, la commissioneelaborò poi una relazio-ne (14 settembre 1580),in cui proponeva di in-traprendere le necessa-rie correzioni nell’otto-bre del 1581, anche sel’entrata in vigore delnuovo calendario ritar-dò di un anno. Il 24 feb-braio 1582, il papaemanò la bolla Intergravissimas con la qua-le stabiliva che, in quel-l’anno, il giovedì 4 ottobre fosse seguito dal ve-nerdì 15 ottobre e che non fossero da conside-rarsi bisestili gli anni centenari non multipli di400.

Clavio non ebbe solo il compito di eseguire icomplessi calcoli per l’attuazione del progetto.Ebbe anche l’incarico ufficiale di pubblicare ilnuovo calendario, di spiegare la genesi, i princi-pi e il funzionamento della riforma (cfr. Romanicalendarii a Gregorio XIII restituti explicatio, Ro-ma 1603, cfr. scheda n. 11 e FIG. 10) e di difen-derla contro gli attacchi di teologi e scienziati pro-testanti. La principale ispirazione dell’iniziativadi Gregorio XIII era stata infatti una preoccupa-zione di carattere religioso: far coincidere il ca-lendario solare con il calendario ecclesiastico.Questa decisa “affermazione del potere ecclesia-stico sul tempo” aveva un forte significato sim-bolico, che i paesi protestanti non erano affattodisposti ad accettare. Tra i più duri oppositori del-la riforma ci fu l’astronomo tedesco Michael Më-

rugia, seemed to gaineveryone’s support.

Work proceeded invarious stages. At theend of 1577, the com-mission produced acompendium of the re-form project, which thepope sent through hispapal nuncios to theleading figures and uni-versities in the Catholicworld, so that theycould in turn pass it onto the most competentmathematicians in eachterritory. Based on theopinions thus gathered,the commission thenproduced a report (14September 1580), inwhich it proposed toundertake the necessarycorrections in October1581, although thelaunch of the new cal-endar was delayed by ayear. On 24 February1582, the papal bull In-ter gravissimas was is-sued, which stated that

in that year, Thursday, 4 October, would be fol-lowed by Friday, 15 October and that centenni-al years that could not be divided by 400 wereno longer to be leap years.

Clavius not only had the task of carrying outthe complex calculations for the project, he wasalso officially responsible for publishing the newcalendar, explaining its genesis, the principlesgoverning the reform and how it worked (cf. Ro-mani calendarii a Gregorio XIII restituti expli-catio, Rome 1603, cf. catalogue no. 11 and FIG.

10). He was also tasked with defending it againstcriticism from protestant theologians and scien-tists. The principal inspiration underpinning Gre-gory XIII’s initiative was a concern of a religiousnature. This resolute “affirmation of ecclesiasti-cal power over time” had a powerful symbolicmeaning, which the protestant countries were notat all inclined to accept. Among the most hard-line opponents of the reform was the Germanastronomemr Michael Mëstlin (1550-1631), who

43

zione eminentemente pratico-applicativa deglistudi di Clavio rientrava nella gerarchia aristote-lica delle scienze in vigore nel Collegio, che vie-tava al matematico di pronunciarsi sulla vera co-stituzione della realtà, compito del fisico.

E tuttavia, Clavio non aveva ancora rivelatoqueste straordinarie competenze quando divenneprotagonista di uno degli eventi più clamorosi nel-la storia della misurazione del tempo.

Tra il 1572 e il 1575, papa Gregorio XIII con-vocò una Commissione per il Calendario (FIG. 9).Obiettivo della congregazione era quello di indi-viduare requisiti e metodi da adottare per la co-struzione di un nuovo calendario. Già da tempo,infatti, gli esperti sapevano che l’errore nella sti-ma della durata dell’anno su cui si basava il ca-lendario giuliano (in vigore dal 1 gennaio del 45a.C.), comportava un ritardo dell’anno civile ri-spetto all’anno solare. Nella seconda metà delCinquecento la differenza aveva ormai raggiun-to i dieci giorni, e quindi l’equinozio di prima-vera – in relazione al quale il Concilio di Nicea(325 d.C.) aveva imposto di fissare la data dellaPasqua – cadeva l’11 marzo (e non più il 21).

La Commissione istituita dal papa compren-deva tre eminenti prelati (il cardinal GuglielmoSirleto, che sostituiva Tomaso Giglio, il vescovoVincenzo Lauri di Mondovì, il Patriarca Ignaziodi Antiochia), tre esperti di arabo, diritto, patri-stica e storia ecclesiastica, tre matematici e astro-nomi: Antonio Lilio (Giglio), Ignazio Danti e Cri-stoforo Clavio. La critica si è molto interrogatasulla ragione del reclutamento per un compito co-sì importante di uno studioso gesuita allora re-lativamente giovane, che, per di più, non avevaancora pubblicato alcun lavoro teoretico. La ra-gione è stata individuata, da una parte, nella man-canza di matematici altrettanto qualificati attiviallora in altre istituzioni educative romane, comela Sapienza (la matematica non era allora inse-gnata nel seminario di nessun altro ordine reli-gioso), dall’altra nella reputazione personale cheClavio aveva allora già acquistato sulla base delsuo lavoro matematico e della sua attività entroil Collegio Romano.

Clavio, probabilmente, ebbe l’incarico di esa-minare e spiegare ai commissari le diverse solu-zioni alternative che erano emerse negli anni cheprecedettero l’istituzione della commissione. Traqueste, quella elaborata dal medico calabreseLuigi Giglio (Aloisius Lillius), (1510-1576), let-tore all’Università di Perugia, sulla quale finiro-

ies came under the Aristotelian hierarchy of thesciences adopted in the Collegio Romano, whichdid not permit mathematicians to make any pro-nouncements on the true nature of reality, thisbeing the domain of physicists.

And yet, Clavius had not yet revealed theseextraordinary skills when he came to the fore inone of the most sensational events in the histo-ry of the measurement of time.

Between 1572 and 1575, Pope Gregory XIIIconvened a Commission for the Reform of theCalendar (FIG. 9). The congregation’s aim was toidentify the requirements and methods to beadopted in creating a new calendar. For sometime experts had been aware that the error in es-timating the length of the year on which the Ju-lian calendar (in use since 1 January 45 BC) wasbased, meant that the civil year lagged behindthe solar year. By the second half of the 16th cen-tury the difference had reached ten days, andtherefore the spring equinox – in relation towhich the Council of Nicaea (325 AD) had de-cided to establish when Easter would fall – nowfell on 11 March (instead of 21 March).

The Commission set up by the pope includedthree eminent prelates (Cardinal Guglielmo Sir-leto, who replaced Tomaso Giglio, Bishop Vin-cenzo Lauri of Mondovì, Patriarch Ignazio ofAntioch), three experts in Arabic, law, patristicsand Church history, three mathematicians andastronomers: Antonio Lilio (Giglio), IgnazioDanti and Christopher Clavius. Many questionshave been asked as to why a relatively young Je-suit academic, who moreover had not yet pub-lished any theoretical work, was recruited forsuch an important task. According to scholars,the answer lies on the one hand in the lack ofsimilarly qualified mathematicians in other edu-cational establishments in Rome, such as theSapienza (mathematics was not then taught inthe seminaries of any other religious orders); andon the other in the personal reputation that Clav-ius had already built up based on his mathe-matical work and his other activities in the Col-legio Romano.

Clavius was probably given the task of exam-ining and explaining to other members of thecommission the various alternative solutions thathad emerged in the years prior to its setting up.In the end, the solution worked out by the Cal-abrian doctor Luigi Giglio (Aloisius Lillius),(1510-1576), who taught at the University of Pe-

42

Fig. 10. Cristoforo Clavio, Romani Calendari a GregorioXIII P.M. restituti explicatio, frontespizio, Roma, 1602.Roma, Archivio storico della Pontificia UniversitàGregoriana (Inv. APUG 774).Fig. 10. Cristophorus Clavius, Romani Calendari aGregorio XIII P.M. restituti explicatio, frontispiece,Rome, 1602. Rome, Historical Archives of the PontificalGregorian University (Inv. APUG 774).

tosto apportare correzioni al sistema geocentri-co, portando da nove a undici il numero dei cie-li. In questo modo, infatti, riusciva a spiegare iquattro movimenti dell’ottava sfera scoperti e mi-surati da Niccolò Copernico, senza doverne adot-tare l’ipotesi eliocentrica. Ancora una volta il ge-suita – vincolato, come tale, al voto solenne diobbedienza al papa – aveva la meglio sul mate-matico.

* Federica Favino, Dipartimento di Storia Cultura Religioni,Università degli Studi di Roma, “Sapienza”

Bibliografia:

BALDINI U., Legem impone subactis: studi su filosofia escienza dei Gesuiti in Italia: 1540-1632, Roma, Bulzoni,1992.BIEN R.,Viète’s Controversy with Clavius over the Truly Gre-gorian Calendar, in Archive for History of Exact Sciences61, 2007, pp. 39-66.BUCCIANTINI M., CAMEROTA M., GIUDICE F., Il telescopio diGalileo: una storia europea, Torino, Einaudi, 2012.CAMEROTA M., Galileo Galilei e la cultura scientifica nel-l’età della controriforma, Roma, Salerno, [2004].Christoph Clavius e l’attività scientifica dei gesuiti nell’etàdi Galileo: atti del Convegno internazionale (Chieti, 28-30aprile 1993), a cura di U. Baldini, Roma, Bulzoni, ©1995.GATTO R., Clavio, Cristoforo, in Il contributo italiano al-la storia del pensiero. Le scienze, a cura di A. Clericuzio,S. Ricci, Roma 2013, s.v.GATTO R., Cristoforo Clavio e l’insegnamento delle mate-matiche nella Compagnia di Gesù, in Il Rinascimento ita-liano e l’Europa, 5° vol. Le scienze, a cura di A. Clericuzio,G. Ernst, con la collab. di M. Conforti, Treviso-Costabis-sara 2008, pp. 437-54.Gregorian reform of the calendar: proceedings of the Vat-ican conference to commemorate its 400th anniversary,1582-1982, edited by G. V. Coyne, M. A. Hoskin and O.Pedersen, Città del Vaticano: Specola Vaticana, 1983.LATTIS J., Between Copernicus and Galileo: Cristoph Clav-ius and the collapse of Ptolemaic cosmology, Chicago; Lon-don: The University of Chicago press, c1994.MAIELLO F., Storia del calendario: la misurazione del tem-po, 1450-1800, Torino, G. Einaudi, 1994.REEVES E., VAN HELDEN A., Verifying Galileo’s Discoveries:Telescope-Making at the Collegio Romano, in Hamel J.,Keil, I., Der Meister und die Fernrohre: Das Wechselspielzwischen Astronomie und Optik in der Geschichte, 2007,pp. 127-141.ROMANO A., La contre-réforme mathématique: constitutionet diffusion d’une culture mathématique jésuite à la Re-naissance, 1540-1640, Rome, École française de Rome,1999.ROMMEVAUX S., Clavius: Une clé pour Euclide au XVIe siè-cle, Paris: Vrin 2005.TORRINI M., Galilei, Galileo, in Il contributo italiano allastoria del pensiero. Le scienze, a cura di A. Clericuzio, S.Ricci, Roma, IEI, 2013, s.v.

preferred to make corrections to the geocentricsystem, increasing the number of heavens fromnine to eleven. He thus managed to explain thefour movements of the eighth sphere discoveredand measured by Nicolaus Copernicus, withouthaving to adopt the heliocentric hypothesis. Onceagain the Jesuit – bound, as such, by a solemnvow of obedience to the pope – won out overthe mathematician.

* Federica Favino, Department of History, Culture, Religions,at the “Sapienza” University of Rome

Bibliography:

BALDINI U., Legem impone subactis : studi su filosofia escienza dei Gesuiti in Italia: 1540-1632, Rome, Bulzoni,1992.BIEN R., Viète’s Controversy with Clavius over the TrulyGregorian Calendar, in Archive for History of Exact Sci-ences 61, 2007, pp. 39-66.BUCCIANTINI M., CAMEROTA M., GIUDICE F., Il telescopio diGalileo: una storia europea, Turin, Einaudi, 2012.CAMEROTA M., Galileo Galilei e la cultura scientifica nel-l’età della controriforma, Rome, Salerno, [2004].Christoph Clavius e l’attività scientifica dei gesuiti nell’etàdi Galileo: Conference proceedings (Chieti, 28-30 April1993), edited by U. Baldini, Rome, Bulzoni, 1995.GATTO R., CLAVIO, CRISTOFORO, in: Il contributo italianoalla storia del pensiero. Le scienze, edited by A. Clericuzio,S. Ricci, Rome 2013, s.v.GATTO R., Cristoforo Clavio e l’insegnamento delle mate-matiche nella Compagnia di Gesù, in: Il Rinascimento ita-liano e l’Europa, 5th vol. Le scienze, edited by A. Clericu-zio, G. Ernst, and M. Conforti, Treviso-Costabissara 2008,pp. 437-54.Gregorian reform of the calendar: proceedings of the Vat-ican conference to commemorate its 400th anniversary,1582-1982, edited by G. V. Coyne, M. A. Hoskin and O.Pedersen, Vatican City: Specola Vaticana, 1983.LATTIS J., Between Copernicus and Galileo: Cristoph Clav-ius and the collapse of Ptolemaic cosmology, Chicago; Lon-don: The University of Chicago press, c1994.MAIELLO F., Storia del calendario: la misurazione del tem-po, 1450-1800, Turin, G. Einaudi, 1994.REEVES E., VAN HELDEN A., Verifying Galileo’s Discoveries:Telescope-Making at the Collegio Romano, in: HAMEL J.,KEIL I., Der Meister und die Fernrohre: Das Wechselspielzwischen Astronomie und Optik in der Geschichte, 2007,pp. 127-141.ROMANO A., La contre-réforme mathématique: constitutionet diffusion d’une culture mathématique jésuite à la Re-naissance, 1540-1640, Rome, École française de Rome,1999;ROMMEVAUX S., Clavius: Une clé pour Euclide au XVIe siè-cle, Paris: Vrin 2005.TORRINI M., Galilei, Galileo, in Il contributo italiano allastoria del pensiero. Le scienze, edited by A. Clericuzio, S.Ricci, Rome, IEI, 2013, s.v.

45

stlin (1550-1631), che nel suo Alterum examennovi pontificalis Gregoriani Kalendarii (1586) de-nunciò gli errori e le incongruenze del nuovo si-stema. Sollecitato da autorevoli amici tedeschi,Clavio gli indirizzò una Novi Calendarii Roma-ni Apologia (1588), in cui lo presentava come“persona infetta dalla peste dell’eresia ubiquita-ria” e lo accusava di aver mentito per attentareall’unità della Chiesa cattolica. Clavio ribatté ne-gli stessi termini anche alle accuse di Joseph Ju-stus Scaliger (1540-1609) e François Viète (1540-1603).

Resta da domandarsi se il contenuto di questeopere ufficiali corrispondesse effettivamente alpensiero del matematico gesuita, se, cioè, le sueidee astronomiche coincidessero con i principi fat-ti valere nell’emanazione della Bolla e da lui di-fesi con tale veemenza. Le opere apologetiche, let-te a fronte, ancora una volta, delle diverse edi-zioni della Sfera e del suo epistolario, rispecchianouna situazione analoga a quella tracciata a pro-posito delle osservazioni telescopiche: primatodella verità dei dati osservativi ma rifiuto di mo-dificarne la tradizionale cornice teorica.

Chiamata a decidere se basare il nuovo calen-dario sui movimenti veri del sole e della luna, op-pure sui loro movimenti medi, la commissioneaveva scelto per la seconda ipotesi, in ossequioalla tradizione (infatti, il calendario giuliano so-lare e quello ecclesiastico luni-solare erano basa-ti su questi ultimi). Sappiamo, invece, che alme-no inizialmente, Clavio pensava che fosse megliobasarsi sui moti reali. Lo scriveva chiaramente nel1580 a Giuseppe Moleto, professore di matema-tica a Padova e sostenitore, come molti altri va-lenti astronomi, della prima impostazione (1580):“io veggo ben che importarebbe assai più per ri-storar l’astronomia, e tenerla in conto, se si pi-gliasse il moto vero, ma questi Signori non lo vo-gliono intendere per molte ragioni, le quali V. S.un altro tempo intenderà”.

Ancora più eloquente, poi, la posizione da luiassunta a proposito della lunghezza dell’anno tro-pico e della spiegazione della precessione degliequinozi. Le diverse edizioni della Sfera docu-mentano chiaramente il suo progressivo abban-dono della teoria tradizionale della trepidazione(ossia della presunta oscillazione annuale dei pun-ti equinoziali) e l’adesione ai parametri di Co-pernico rispetto a tale fenomeno. Egli, però, allostesso tempo non alterò mai la struttura teoricadel libro per “salvare i fenomeni”. Preferì piut-

in his Alterum examen novi pontificalis Grego-riani Kalendarii (1586) denounced the errorsand inconsistencies of the new system. Pressedby authorative German friends, Clavius re-sponded with Novi Calendarii Romani Apolo-gia (1588), in which he described him as a “per-son infected with the plague of the ubiquitarianheresy” and accused him of having lied in an at-tempt to harm the unity of the Catholic church.Clavius also replied in a similar fashion to theaccusations of Joseph Justus Scaliger (1540-1609) and François Viète (1540-1603).

The question remains as to whether the con-tent of these official publications effectively cor-responded to the Jesuit mathematician’s ideas:that is, did his ideas about astronomy coincidewith the principles upheld in the papal bull anddefended so vehemently by him? The apologias,read in parallel in the various editions of theSphere and in his collected letters, once again re-flect a situation similar to that of the telescopeobservations: the primacy of the truth of the ob-served data combined with a refusal to modifythe traditional theoretical framework.

Called on to decide whether to base the newcalendar on the true movements of the sun andthe moon, or on their average movements, thecommission opted for the second hypothesis, ina gesture of respect for tradition (in fact, the Ju-lian solar calendar and the ecclesiastical lunar-solar calendar were based on the latter). Weknow, in contrast, that at least initially, Claviusthought that it was better to be based on realmotion. He said so clearly in 1580 to GiuseppeMoleto, professor of mathematics at Padua anda supporter, like many other able astronomers,of the first option (1580): “In my opinion to re-new and enhance astronomy it would be muchbetter to consider true motion, but these gentle-men choose not to understand this for reasonsthat your lordship will understand hereafter.”

Even more eloquent, then, is the position headopted regarding the length of the tropical yearand the explanation of the precession of theequinoxes. The various editions of the Spheresclearly document his progressive abandonmentof traditional theory on trepidation (that is thealleged yearly swinging of the equinoctial points)and his support of Copernicus’s parameters inrespect of such phenomenon. However, at thesame time he did not alter the theoretical struc-ture of the book to “save the phenomena”. He

44