Arterial Injury in Total Knee Arthroplasty

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

1 -

download

0

Transcript of Arterial Injury in Total Knee Arthroplasty

The Journal of Arthroplasty Vol. 25 No. 8 2010

Review Article

From thStockport, M

SubmitNo benReprint

Hill Hospit© 20100883-5doi:10.1

Arterial Injury in Total Knee Arthroplasty

Usman Butt, MB, ChB (Hons), MRCS,Rohit Samuel, BSc (Hons), MB, ChB, MSc (Orth Eng), FRCS (Orth),Ajay Sahu, MBBS, MS, MRCS, Imran S. Butt, BSc, MB, ChB, MRCS,

David S. Johnson, MB, ChB, FRCS (Tr and Orth), and Philip G. Turner, FRCS

Abstract: Arterial complications associated with knee arthroplasty are relatively rare, althoughprobably underreported, complications of knee arthroplasty that carry a risk of significantmorbidity. Thorough preoperative assessment and close liaison with a vascular surgeon, combinedwith an appreciation of common anatomical variants or distorted anatomy, may help prevent boththromboembolic and direct injuries from occurring. Clinical features of arterial complicationsfollowing knee arthroplasty may vary significantly from acute hemorrhage or ischemia in theimmediate postoperative period to chronic pain and swelling presenting even months followingthe procedure. There is potential for diagnostic confusion and delay that may adversely affectoutcome. Early diagnosis along with vascular surgical review and intervention is key to successfulmanagement. Keywords: arterial injury, vascular injury, total knee arthroplasty complications,arthroplasty complications, vascular complications in knee arthroplasty.© 2010 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Arterial injury associated with total knee arthroplasty(TKA) is a relatively rare but potentially devastatingcomplication. There are a variety of ways in whicharterial injuries and complications may present, withconsequences ranging from transient bleeding to limbloss and even death. With the rising number of bothprimary and revision TKA being performed on an agingpopulation, the potential for arterial injuries must notbe underestimated.Aconsiderableportionof the literature surrounding this

topic consists of individual case reports, case series, andsurveys,althoughafewlargestudiesdoexistwithvariableincidences reported. In one large multicenter study,Abularrage et al [1] reported an incidence of 0.09%lower extremity arterial injuries from a sample of 26 106TKA, including 2077 revision procedures. The study didnot accurately define the nature of the vascular injuriessustained. In the largest single-center series,Calligaroet al

e Stockport NHS Foundation Trust, Stepping Hill Hospital,anchester, UK.

ted October 14, 2008; accepted May 3, 2010.efits or funds were received in support of the study.requests: Usman Butt, MB, ChB (Hons), MRCS, Steppingal, Stockport, SK2 7JE Manchester, UK.Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

403/2508-0023$36.00/0016/j.arth.2010.05.018

131

[2] demonstrated an overall incidence of 0.17% arterialcomplications during TKA. From their sample of 13 618(including 1665 revisions), therewere 24 arterial compli-cations, of which 3 were popliteal artery transections, 5were popliteal artery pseudoaneurysms, and 16 weresolely ischemic complications. Rand reported 3 cases ofarterial ischemia secondary to thrombosis from a sampleof 9022 knee arthroplasties between 1971 and 1986(incidence 0.03%) [3,4]. Parvizi et al [5] produced datafromasingle centeron15383hipandkneearthroplasties.They described 16 vascular injuries, of which 11 wererelatedtokneearthroplasty(1revision).Theproportionofknee arthroplasties was not given, making a specificincidence impossible to calculate. Arterial thrombosisoccurred in 9 patients, with direct injury being themechanism in the other 2 patients. Wilson et al [6]reviewedasampleof4350electiveorthopedicproceduresincluding hip, knee, and ankle arthroplasties. Arterialinjuries occurred during 21 procedures, of which twothirds were associated with TKA. The mechanisms ofinjury were not stratified according to which joint wasreplaced, and the exact number of TKAs performed wasnot stated. Da Silva and Sobel [7] conducted a surveyin which 13 of 190 vascular surgeons provided informa-tion regarding their experiences of popliteal vascularinjury associated with TKA. They reported a total of19 complications, of which 12 were direct arterial

1

1312 The Journal of Arthroplasty Vol. 25 No. 8 December 2010

lacerations. Rush et al [8] contacted 470 surgeons inAustralia, fromwhich 100 replied. Of these, there were 5reportsofdirectarterial injuryand7ofarterial thrombosis.Kumaretal [9] surveyed147Britishorthopedic surgeons.From 107 responses plus their own case, there were14 reports of vascular complications, which includedarterial transection, thrombosis, arteriovenous fistula, oraneurysm formation.

MechanismThere are 4 principal mechanisms responsible for the

arterial complications encountered in TKA. In patientswith preexisting vascular disease, atheromatous plaquesmay fracture secondary to mechanical pressure, leadingto emboli and arterial insufficiency. This is largelyassociated with the use of a pneumatic tourniquet andmay occur at the level of the superficial femoral artery(SFA) [3,8-12].Arterial thrombosis occurring at the level of the SFA or

popliteal artery may be implicated as a second mecha-nism. Fixation of the SFA by a tourniquet andsubsequent manipulation of the knee can lead to tearsin the arterial intimal wall. These intimal tears,compounded by the low-flow state induced by tourni-quet use, favor the formation of occlusive thrombus andsubsequent ischemia [3,8-13].Release of severe flexion contractures and subsequent

traction on the popliteal artery may likewise cause

Fig. 1. System for preoperative assessm

intimal tears, but can also lead to compression of theartery against bony or musculotendinous structures as athird mechanism [3,8-14]. Robson et al [14] reportedsuch a case whereby compression of the popliteal artery,following correction of a flexion deformity, necessitatedrelease of the musculofascial structures and surgicaldivision of arterial branches.The fourth mechanism involves direct puncture or

laceration injury to the perigeniculate vasculature. Thiscan occur with any form of instrumentation such as avibrating saw, scalpel blade, diathermy, or a misplacedretractor [12].

Preoperative Risk and AssessmentCareful preoperative assessment can help identify

those patients who are at higher risk of sustainingarterial complications during their knee arthroplasty(Fig. 1). A variety of strategies can then be used tominimize this risk. Important risk factors to considerinclude the following:

Preexisting Arterial DiseaseHistory or examination findings suggestive of arterial

insufficiency are among the most important factors toconsider if one is to avoid vascular complications duringTKA. Points in the history include tobacco use, hyper-tension, diabetes mellitus, claudication symptoms, restpain, previous transient ischemic attacks or stroke, or

ent of arterial disease before TKA.

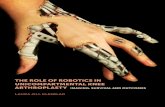

Fig. 2. Illustration of the major neurovascular structures atrisk during TKA (left knee). At the level of the joint line, thetibial nerve (TN), popliteal vein (PV), and popliteal artery (PA)are vulnerable to injury between 11 and 1 o'clock. Distal to thejoint line, the anterior tibial artery (ATA) and commonperoneal nerve (CPN) are vulnerable between 1 and 3 o'clock.P indicates posterior; A, anterior; M, medial; L, lateral.

Arterial Injury in TKA � Butt et al 1313

any previous cardiovascular surgery [1,2,4,6,10]. Forevery patient planned for TKA, the orthopedic surgeonshould make an assessment of the limb vascularity. As aminimum, this should include inspection for trophicchanges such as skin discoloration or absence of hair,skin ulceration (past or present), venous guttering, orsigns of previous surgery. The lower limb should bepalpated for temperature and pulses with comparisonmade to the contralateral limb. In particular, thepopliteal fossa should be examined for aneurysms [4],which are often bilateral. If present, these should beassessed by a vascular surgeon before TKA given thehigh risk of thrombosis or embolism [15].The presence of vascular calcification on plain radio-

graphs should further alert the surgeon to the presenceof arterial disease [10]. The ankle-brachial pressureindex is a useful and simple test that can be performed inthe clinic. A value of less than 0.9 suggests the presenceof arterial disease, although results should be interpretedwith caution in the presence of diabetes mellitus whereresults may be misleadingly high because of calcificationand inelasticity of the vessels. Values less than 0.5 areindicative of severe ischemia [1,4].Where concern exists regarding the vascularity of a

limb, a vascular surgeon should be consulted in thepreoperative phase. Any history or evidence of previousvascular intervention on the affected limb, includingendovascular techniques, mandates a preoperativevascular opinion [4]. More detailed Doppler ankle-brachial pressure index studies (including observation ofpulse waveforms) at different levels in the limb can act asa useful screening tool. Preoperative duplex ultrasoundscanning or angiography may subsequently be requiredto more formally assess flow in the native circulation,grafts, or across any stents. Where there is significantischemia, revascularization may be recommended be-fore TKA [2,4].The use of a tourniquet should be considered in the

preoperative phase. Tourniquets are often implicated orcontributory to the development of arterial complica-tions in TKA [2-4,7-11]. Although they do facilitate adry bone surface for the placement of cementedcomponents, their use is not essential in TKA andshould be rationalized. Certainly, where there are signsor symptoms of peripheral arterial disease, they shouldbe avoided. If any doubt exists, consultation with avascular surgeon is recommended. Where there hasbeen previous bypass surgery, a tourniquet should notbe used because of the risk of graft occlusion [4,10].

Anatomical ConsiderationsAnatomical variation or distortion increases the risk of

direct arterial injury during major knee surgery [16-20].In revision knee surgery, blood vessels may be firmlyadherent within fibrous scar tissue, rendering themmore vulnerable to the saw blade during tibial resection

[1,5,19]. A tethered artery is also more likely to bedamaged during manipulation of the knee joint [2,5,19].This is also likely to be the case in some complex primarysituations, for example, following previous knee trauma.Wilson et al [6] found that 71% of patients with arterialinjury during an elective orthopedic procedure hadpreviously had surgery and that 43% had a history ofsome bone or joint injury in proximity to the operativesite (with or without subsequent surgery). Calligaro et al[2] found that arterial complications were more thantwice as common following revision TKA comparedwith a primary procedure (0.36 vs 0.15%, P = .0112).As indicated earlier, the release of severe flexion

contractures during TKA carries the risk of arterialstretching or compression [3,8-14]. It is thereforeimportant that the operating surgeon notes the presenceof any contracture preoperatively and is aware of thispotential risk.Although anatomical distortions are extremely impor-

tant to consider in the preoperative phase, one shouldalso consider in detail the normal vascular anatomy andits variants before approaching TKA. Based on cadavericstudies, Rubash et al [16] used the analogy of a clock faceto describe the position of the neurovascular structuresaround the tibial surface. For a left knee, taking the6-o'clock position to be directly anterior, the poplitealvein would be at a 12-o'clock position, the poplitealartery at 1-o'clock, and the anterior tibial artery at2-o'clock (after bifurcation of the popliteal artery)

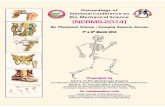

Fig. 3. Illustrations of the anterior tibial artery (ATA) branch-ing off the popliteal artery (left knee). (A) The ATA arisesbelow the level of the popliteus muscle. (B) The ATA arisesabove popliteus passing anterior to it near the posterior marginof the tibia.

1314 The Journal of Arthroplasty Vol. 25 No. 8 December 2010

(Fig. 2). A zone between 11 and 3 o'clock washighlighted as a risky area for neurovascular injury.The authors also concluded that extra caution be usedduring screw placement for the uncemented tibialknee arthroplasty components upon which the studywas originally based [16]. Extrapolating the findingsfrom this study, it is clear that these vessels would alsobe vulnerable during soft tissue retraction and proce-dures including meniscal or posterior cruciate ligamentresection, or during posterior capsular releases, forexample [17].Ninomiya et al performed intraoperative arteriograms

at the time of TKA on cadaveric specimens. They foundthat a posterior retractor placed the popliteal artery atrisk when it was inserted lateral to themidline or if it wasinserted more than 1 cm into the soft tissues [21].Farrington et al studied the position of the poplitealartery in the arthritic knee. They reported a meandistance of 0.96 to 3.15 mm of the artery to the posteriortibial cortex in flexing the knee from 0° to 90° [22].Tindall et al studied the prevalence of high-origin

anterior tibial arteries (proximal to popliteus) in asample of 100 knees [23]. They found 6 knees with ahigh-origin anterior tibial artery. The artery passedanterior to popliteus in direct contact with the posteriorcortex of the tibia in all these cases, putting it atsignificant potential risk during knee arthroplasty.Klecker et al studied the prevalence of this variation ofthe anterior tibial artery (described as the “aberrantanterior tibial artery”) using magnetic resonance imag-ing studies [18]. They found a prevalence of 2.1% (23 of1116 knees), again highlighting the significant risk ofinjury during orthopedic procedures (Fig. 3).

EthnicityAbularrage et al [1] found a higher incidence of arterial

complications in African Americans. It has previouslybeen shown that the black population tends to havelower ankle-brachial pressure indices [24] and moresevere occlusive arterial disease in the tibial and peronealarteries compared with the white population [25].

Presentation and ManagementThere are 4 principal ways in which arterial complica-

tions secondary to TKA can present. These include(a) intraoperative hemorrhage, (b) acute ischemia, (c)false aneurysm formation, and (d) arteriovenousfistula formation.

Intraoperative HemorrhageIf intraoperative vascular injury is suspected, the

tourniquet should be deflated before implantation ofcomponents to allow for adequate assessment. Excessivebleeding, an enlarging popliteal swelling, or absent pedalpulses (where previously present) are highly indicativeof arterial injury [12]. Releasing the tourniquet asroutine practice prior to wound closure to ensure

hemostasis has been suggested [26]. Although theoverall benefits of this remain unclear in terms ofpostoperative recovery and complications, it wouldclearly facilitate early diagnosis of a major vascularinjury [26]. Indeed, the routine use of a tourniquet inTKA has previously been questioned, with some studiesshowing no benefit or even delays in postoperativerecovery [4,27,28].

Arterial Injury in TKA � Butt et al 1315

If any concern exists regarding the possibility of asignificant vascular injury, an immediate vascularsurgical opinion should be sought. Primary repair orpatch angioplasty may be all that is required for themajority of arterial lacerations. Where complete arterialtransection has occurred, an end-to-end anastomosis isoccasionally possible, although an interposition graftmay be necessary where excess tension would be placedon the repair. Arterial ligation with a bypass procedure ismore commonly required [2,6]. These interventions areoften carried out through a separate medial incisionpermitting an extensile exposure of the SFA andpopliteal vessels with which most vascular surgeonsare familiar [7].

Acute IschemiaIn the immediate postoperative period, signs of acute

limb ischemia such as a cold and pale foot, absent orweak pedal pulses, excessive pain, paresthesia, or motorweakness may be difficult to appreciate because of theeffects of a spinal anesthesia, dressings, or venousthromboembolic deterrent devices [2]. However, anysuspicion in conjunction with an excessively swollenknee or, if used, a high drain output with fresh blood issuggestive of arterial laceration. The signs of acute limbischemia in isolation suggest thromboembolism ormechanical occlusion.Whether diagnosed immediately or early in the

postoperative period, an urgent vascular opinion isrequired. It is imperative that, immediately followingevery TKA, the operating surgeon examines thevascularity of the limb. This should be repeated infurther postoperative checks on the ward. A delay indiagnosis may lead to irreversible ischemia or compart-ment syndrome and potential limb loss [2,8].Once a clinical diagnosis has been made, further

investigation and management will be dictated by theclinical picture and severity of injury. Where indicatedand where the risk of further delay is deemed acceptable,the vascular surgeon may request angiography beforerevascularization surgery or as a therapeutic option inselect cases [1,2]. Hemorrhagic arterial complications aretreated in a similar fashion as if diagnosed intraopera-tively. In the case of arterial thrombosis, options includeangioplasty or thrombectomy, with or without conco-mitant intraarterial thrombolysis. Bypass grafting isoften carried out as the primary revascularizationprocedure [1,2,6,8,29]. Percutaneous aspiration ofthrombus material has also been performed [30,31].Where a revascularization procedure is undertaken

after TKA (regardless of etiology), there should be arelatively low threshold for prophylactic limb fascio-tomies [1]. In one study, fasciotomies were performedfor any patient suspected of having limb ischemia forgreater than 6 hours or where muscle swelling was seenat exploration [2].

False Aneurysm FormationFalse or pseudoaneurysms following popliteal arterial

injury during TKA have been described in the literature[2,15,32-42]. Time to presentation is variable, withreports ranging from 2 days postoperatively [33] to5 months [15] following TKA for popliteal arterypseudoaneurysms and up to 30 months for those of thegeniculate artery [43]. Often, pain is felt in the poplitealfossa or calf, whichmay be associatedwith swelling and apulsatile mass. Hemarthroses occur where there iscommunication between a perigeniculate or poplitealpseudoaneurysm and the joint capsule [36]. Thrombosisand/or distal emboli can lead to limb ischemia [36].There may be an associated neurologic deficit particu-larly in the peroneal nerve territory [33,34]. Thecondition may be confused with the more commoncomplication of deep venous thrombosis and investi-gated as such. Indeed, a deep venous thrombosis maycoexist and can occur secondary to venous compressionby mass effect of the pseudoaneurysm [37]. Earlyassessment with duplex ultrasound scanning will helpdistinguish the diagnoses. Management options includearterial embolization using coils or intraluminal throm-bin [36], endovascular stenting [35,38,39], oversewingof the aneurysm neck [34], or excision and repair/bypass, depending on the nature of the pseudoaneur-ysm and surgeon preference [15,33,39].

Arteriovenous Fistula FormationArteriovenous fistulae are a less reported complication

of TKA [4,32]. They may occur following injury to thepopliteal vessels [39,44,45] or to the medial or lateralgeniculate arteries [8,15,32,46]. Presentation of thiscomplication is variable. Pain is often felt around theknee, and there may be diffuse swelling in the lowerlimb [32,44]. There may be a pulsatile mass with apalpable thrill in the popliteal fossa [32]. As withpseudoaneurysms, recurrent hemarthroses are a poten-tial mode of presentation [8]. One reported casepresented with an acutely ischemic limb 6 monthspostoperatively [45]. Definitive diagnosis is made withultrasonography or angiography. The majority of caseswill require operative excision of the fistula and vascularrepair, although arteriovenous fistulae of the geniculatevessels have been reported to settle spontaneously [32].

OutcomeMortality and limb loss are fortunately quite infre-

quent occurrences. Calligaro et al [2] reported no deathswith limb salvage achieved in all 24 patients whosuffered arterial complications (13 618 TKA). Therewere 2 limbs lost from 20 patients (10%) in the study byAbularrage et al [1] (26 106 TKA). In neither study werethe individual mechanisms described in relation tooutcome. Parvizi et al [5] had no deaths, but oneabove-knee amputation in a patient who developedpopliteal artery thrombosis after TKA.

1316 The Journal of Arthroplasty Vol. 25 No. 8 December 2010

Da Silva and Sobel [7] reported the experience of13 vascular surgeons (6.8% survey response rate). Therewere 2 amputations, but no deaths, from a total of 19described arterial complications. Again, the exact mech-anism of initial arterial injury in the 2 patients whosubsequently lost their limbs is not clear.Rush et al [8] demonstrated 1 death and 5 amputa-

tions at varying levels in their survey reflecting thecombined experience of 100 Australian orthopedicsurgeons. Kumar et al [9] described the experience of107 members of the British Association of Surgeons ofthe Knee in addition to their own case; there were3 deaths and 6 amputations. All deaths and amputationsdescribed in these surveys were secondary to thrombosisof the popliteal or femoral artery. All those with directarterial injuries achieved limb survival following vascu-lar intervention.It is not possible to glean from the literature the relative

incidences of peripheral arterial disease in patients whosubsequently go on to develop thrombosis or suffer adirect arterial injury. It would be interesting to know, asthis could possibly provide further explanation for theworse observed outcomes after arterial thrombosis.What does seem clear is that ischemia secondary to

thrombotic occlusion tends to be diagnosed later thanhemorrhagic complications resulting from direct arterialinjury. This may be due to delayed manifestation butalso due to difficulties in diagnosis [2]. It is thought thatdelays of greater than 4 to 6 hours can lead toirreversible muscle and nerve ischemia and subsequentpoor outcomes [8,39].Wilson et al [6] found that 3 of 5 patientswith a delayed

diagnosis of arterial ischemia after lower limb arthro-plasty (including hip and ankle) ultimately requiredamputation. Although not achieving statistical signifi-cance, Calligaro et al [2] reported that where diagnosis isdelayed for more than 24 hours postoperatively, patientsmore frequently required fasciotomies and developedneuromotor complications including foot drop. Abular-rage et al [1] also reported a slightly higher proportion ofpatients requiring fasciotomy where vascular repairoccurred greater than 24 hours postoperatively (7/16 vs5/18). These findings were not however deemed clini-cally significant by the authors. Notably, of the 2amputees in this series, 1 had a thrombendarterectomyon day 12 and subsequently an amputation on day 19.The other patient had an amputation as a primaryprocedure on day 15 postoperatively.Several case reports are also available in the literature

regarding arterial thromboses after TKA with variedresults. Berger et al [30] described a good outcome for apatient who was promptly diagnosed and treated forarterial thrombosis by percutaneous aspiration. Belle-mans et al [31] performed a similar procedure in 2 casesdiagnosed 1 and 2 days postoperatively. Reperfusion wasachieved in both patients, although compartment syn-

drome requiring fasciotomies and a subsequent footdrop occurred in both. Matziolis et al [29] reported on2 cases of arterial thrombosis diagnosed within 2 hours,both of which were successfully treated with thrombec-tomies. Mureebe et al [47] also reported 2 cases wherediagnosis was made immediately postoperatively in onepatient and 1 day postoperatively in the other. Bothweresuccessfully treated with thrombectomy and bypassgrafting. Holmberg et al [39] reported on a selectionof arterial complications, 2 of which were due tothrombotic occlusion. They both went on to a successfulrecovery after thrombectomy, undertaken at 12 hourspostoperatively in one patient and at a week in the otherpatient. Hagan and Kaufman [48] reported one casewhere thrombectomy performed 1 day postoperativelyachieved a good result with no residual effects from thearterial occlusion. Hozack et al [15] described a casewhere a thrombectomy performed in the early postope-rative period was unsuccessful, with the patient subse-quently undergoing an above-knee amputation.Although results are mixed, there is a clear consensus

that early diagnosis and treatment are important. Thebest form of treatment remains contentious, however,particularly where thrombectomy or thrombendarter-ectomy is carried out as the sole primary revasculariza-tion procedure. Abularrage et al [1] found that morethan one half of patients who underwent thrombect-omy/thrombendarterectomy alone required furtherprocedures. Calligaro et al [2] found that arterialthrombectomy was successful as a sole procedure inonly one quarter of patients. Restricting thrombectomy/thrombendarterectomy to a few select cases and anaggressive approach to revascularization may improveoutcome in arterial thrombosis after TKA [1,2,6].Outcomes for pseudoaneurysm and arteriovenous

fistulae are generally only accounted in case reports,albeit with favorable results. Collating the results forpopliteal pseudoaneurysms shows the following: 3 hadexcision of their aneurysms with repair or bypass andwith no further complications reported [15,33,39];1 had patch angioplasty with no complications at1 year [37]; 1 had direct repair with oversewing of thepseudoaneurysm neck with no surgical complications,although there was no improvement in the reducedplantar sensation at 6 months [34]; 5 had endovascularstenting with no evidence of stent failure at follow-upranging from 12 to 24 months [35,38,40,41,49]; 1 hadembolization using an angioplasty balloon and intra-luminal thrombin injection and was asymptomatic at2 years [36]; and 1 had a similar procedure using anangioplasty balloon alone to induce thrombosis withinthe pseudoaneurysm, with good results at 2-monthfollow-up [42]. Calligaro et al [2] had 5 poplitealpseudoaneurysms in their study and Wilson et al [6]had 3, although neither described the outcome for thisgroup of patients in isolation.

Arterial Injury in TKA � Butt et al 1317

It is important to be aware that, although endovascularstenting for pseudoaneurysms after TKA has beencarried out with apparent success for both popliteal[26,35,38] and geniculate arteries [36,40,50,51], ongo-ing surveillance is required to detect any endoleaks,stent migration, fracture, or occlusion, given the highlymobile nature of the knee joint [35].Regarding arteriovenous fistulae of the popliteal and

perigeniculate vessels, good results are obtained aftersurgical excision and vascular repair. Thomas et al [44]reported complete resolution of symptoms after resec-tion of a fistula between the popliteal vessels 3 yearsfollowing TKA. Dennis et al [46] reported 2 cases oftraumatic arteriovenous fistula associated with falseaneurysms of the inferior medial geniculate artery.Surgical excision with ligation of the artery resolvedthe problem in both patients. From the survey by Rushet al [8], the single case of an arteriovenous fistula had agood result after surgical repair. Interestingly, Langka-mer [32] reported 1 case that settled spontaneously after3 months. Burger et al [45] described the percutaneousendovascular treatment of a thrombosed arteriovenousfistula 6 months after TKA with a polytetrafluoroethy-lene stent, with no complications at 3 months.

SummaryCareful preoperative risk assessment will help identify

those patients at increased risk of arterial complicationsassociated with TKA. Where there is significant anatom-ical distortion following previous surgery or trauma orwhere there is evidence of arterial disease, preoperativevascular consultation and angiography may be war-ranted. The use of a tourniquet should be consideredcarefully in light of the preoperative examinationfindings. A thorough understanding of normal andanatomical variants combined with careful intraopera-tive instrumentation and manipulation of the knee isessential. If all these factors are considered carefully, thenthe risks of arterial injury will hopefully be reduced.In the event that an arterial complication does occur,

prompt recognition is of paramount importance to limbsurvival and limiting patient morbidity. Postoperativediagnosis may be delayed by atypical presentations,although arterial compromise in any form must alwaysbe considered in the event of pain or swelling followingTKA, even in an outpatient setting. Once the diagnosisis suspected, a timely vascular surgical opinion shouldbe obtained to achieve the best possible outcome forthe patient.

References1. Abularrage CJ, Weiswasser JM, Kent JD, et al. Predictors

of lower extremity arterial injury after total knee or hiparthroplasty. J Vasc Surg 2008;47:803.

2. Calligaro KD, Dougherty MJ, Ryan S, et al. Acute arterialcomplication associated with total hip and knee arthro-plasty. J Vasc Surg 2003;38:1170.

3. Rand JA. Vascular complications after total kneearthroplasty. Report of three cases. J Arthroplasty1987;2:89.

4. Smith DE, McGraw RW, Taylor DC, et al. Arterialcomplications and total knee arthroplasty. J Am AcadOrthop Surg 2001;9:253.

5. Parvizi J, Pulido L, Slenker N. Vascular injuries after totaljoint arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2008;23:1115.

6. Wilson JS, Miranda A, Johnson BL, et al. Vascular injuriesassociated with elective orthopaedic procedures. Ann VascSurg 2003;17:641.

7. Da Silva MS, Sobel M. Popliteal vascular injury duringtotal knee arthroplasty. J Surg Res 2003;109:170.

8. Rush JH, Vidovich JD, Johnson MA. Arterial complica-tions of total knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg 1987;69-B:400.

9. Kumar SN, Chapman JA, Rawlins I. Vascular injuries intotal knee arthroplasty. A review of the problem withspecial reference to the possible effects of the tourniquet.J Arthroplasty 1998;13:211.

10. Delaurentis DA, Levitsky KA, Booth RE, et al. Arterial andischaemic aspects of total knee arthroplasty. Am J Surg1992;164:237.

11. McCauley CE, Steed DL, Webster MW. Arterial complica-tions of total knee replacement. Arch Surg 1989;119:260.

12. Saleh KJ, Hoeffel DP, Kassim RA, et al. Complications afterrevision total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg 2003;85-A(Suppl 1):71.

13. Ohira T, Fujimoto T, Taniwaki K. Acute artery occlusionafter total knee arthroplasty. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg1997;116:429.

14. Robson LJ, Walls CE, Swanson AB. Popliteal arteryobstruction following Shiers total knee replacement. ClinOrthop 1975;109:130.

15. Hozack WJ, Cole PA, Gardner R, et al. Popliteal aneurysmafter total knee arthroplasty. Case reports and review ofthe literature. J Arthroplasty 1990;5:301.

16. Rubash HE, Beregr RA, Britton CA, et al. Avoidingneurologic and vascular injuries with screw fixation ofthe tibial component in total knee arthroplasty. ClinOrthop Rel Res 1993;286:56.

17. Ayers DC, Dennis DA, Johanson NA, et al. Commoncomplications of total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Jt Surg[Am] 1997;79-A:278.

18. Klecker RJ, Winalski CS, Aliabadi P, et al. The aberrantanterior tibial artery: magnetic resonance appearance,prevalence, and surgical implications. Am J Sports Med2008;36:720.

19. Metzdorf A, Jakob RP, Petropoulos P, et al. Arterial injuryduring revision total knee replacement. A case report.Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 1999;7:246.

20. Bartlett RJ, Roberts A, Wong J. Risk to popliteal vessels inmajor knee surgery, an anatomical study and survey ofvascular surgeons. J Bone Joint Surg Br Proceedings 2004;86:468.

21. Ninomiya JT, Dean JC, Goldberg VM. Injury to thepopliteal artery and its anatomic location in total kneearthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 1999;14:803.

22. Farrington WJ, Charnley GJ, Harries SR, et al. Position ofthe popliteal artery in the arthritic knee. J Arthroplasty1999;14:800.

1318 The Journal of Arthroplasty Vol. 25 No. 8 December 2010

23. Tindall AJ, Shetty AA, James KD, et al. Prevalence andsurgical significance of a high-origin anterior tibial artery.J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 2006;14:13.

24. Aboyans V, Criqui MH, McClelland RL, et al. Intrinsiccontribution of gender and ethnicity to normal ankle-brachial pressure index values: the multi-ethnic study ofatherosclerosis (MESA). J Vasc Surg 2007;45:319.

25. Sidawy AN, Schweitzer EJ, Neville RF, et al. Race as a riskfactor in the severity of infragenicular occlusive disease:study of an urban hospital population. J Vasc Surg 1990;11:536.

26. Rama KR, Apsingi S, Poovali S, et al. Timing oftourniquet release in knee arthroplasty. Meta-analysisof randomized, controlled trials. J Bone Joint Surg Am2007;89:699.

27. Abdel-Salam A, Eyres KS. Effects of tourniquet duringtotal knee arthroplasty: a prospective randomised study.J Bone Jt Surg [Br] 1995;77-B:250.

28. Wakankar HM, Nicholl JE, Koka R. A prospectiverandomised study. J Bone Jt Surg [Br] 1999;81-B:30.

29. Matziolis G, Perka C, Labs K. Acute arterial occlusion aftertotal knee arthroplasty. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2004;124:134.

30. Berger C, Anzbock W, Lange A, et al. Arterial occlusionafter total knee arthroplasty. Successful management of anuncommon complication by percutaneous thrombusaspiration. J Arthroplasty 2002;17:227.

31. Bellemans J, Stocks L, Peerlinck K. Arterial occlusion andthrombus aspiration after total knee arthroplasty. ClinOrthop Rel Res 1999;336:164.

32. Langkamer VG. Local vascular complications after kneereplacement: a review with illustrative case reports. Knee2001;8:259.

33. Sandoval E, Ortega FJ, Garcia-Rayo MR, et al. Poplitealpseudoaneurysm after total knee arthroplasty secondaryto intraoperative arterial injury with a surgical pin.J Arthroplasty 2008;23:1239.

34. O'Connor JV, Stocks G, Crabtree JD, et al. Poplitealpseudoaneurysm following total knee arthroplasty. JArthroplasty 1998;13:830.

35. Vaidhyanath R, Blanshard KS. Insertion of covered stentfor treatment of a popliteal artery pseudoaneurysmfollowing total knee arthroplasty. Br J Radiol 2003;76:195.

36. Ibrahim M, Booth RE, Clark TW. Embolization oftraumatic pseudoaneurysms after total knee arthroplasty.J Arthroplasty 2004;19:123.

37. Karkos CD, Thompson GJL, D'Souza SP, et al. Falseaneurysm of the popliteal artery: a rare complication of

total knee replacement. Knee Surg Sports TraumatolArthrosc 2000;8:53.

38. Plagnol PH, Diard N, Bruneteau P, et al. Pseudoaneurysmof popliteal artery complicating a total knee replacement: asuccessful percutaneous endovascular treatment. Eur JVasc Endovasc Surg 2001;21:81.

39. Holmberg A, Milbrink J, Bergqvist D. Arterial complica-tions after knee arthroplasty: 4 cases and review of theliterature. Acta Orthop scand 1996;67:75.

40. Sloan K, Mofidi R, Nagy J, et al. Endovascular treatmentfor traumatic popliteal artery pseudoaneurysms after kneearthroplasty. Vasc Endovascular Surg 2009;43:286.

41. D'Angelo F, Carrafiello GP, Lagana D, et al. Popliteal arterypseudoaneurysm after revision of total knee arthroplasty:endovascular treatment with a stent graft. Emerg Radiol2007;13:323.

42. Cowell GW, Boom SJ, Ablett MJ. Thrombosis of poplitealartery pseudoaneurysm by deployment of angioplastyballoon after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2009;24:825.

43. Katsimihas M, Robinson D, Thornton M, et al. Therapeuticembolization of the genicular arteries for recurrenthemarthrosis after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty2001;16:935.

44. Thomas R, Agarwal M, Lovell M, et al. An unusualpresentationof apopliteal arteriovenous fistulaafter primarytotal knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2008;23:945.

45. Burger T, Meyer F, Tautenhahn J, et al. Percutaneoustreatment of rare iatrogenic arteriovenous fistulas of thelower limbs. Int surg 1998;83:198.

46. Dennis DA, Neumann RD, Toma P, et al. Arteriovenousfistula with false aneurysm of the inferior medialgeniculate artery. A complication of total knee arthro-plasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1987;255.

47. Mureebe L, Gahtan V, Kahn M. Popliteal artery injuryafter total knee arthroplasty. Am Surg 1996;62:366.

48. Hagan P, Kaufman E. Vascular complication of kneearthroplasty under tourniquet. Clin Orthop Rel Res 1990;257:159.

49. Hartford JM, Kwolek C, Circle B. Popliteal pseudoaneu-rysm after total knee arthroplasty: MRI of the vascularanatomy. Orthopedics 2002;25:187.

50. Moran M, Hodgkinson J, Tait W. False aneurysm of thesuperior lateral geniculate artery following total kneereplacement. Knee 2002;9:349.

51. Pritsch T, Parnes N, Menachem A. A bleeding pseudoa-neurysm of the lateral genicular artery after total kneearthroplasty—a case report. Acta Orthop 2005;76:138.