„von Humboldt, Alexander (1769–1859).“ In: James D. Wright (Hg.): International Encyclopedia...

Transcript of „von Humboldt, Alexander (1769–1859).“ In: James D. Wright (Hg.): International Encyclopedia...

Provided for non-commercial research and educational use only.Not for reproduction, distribution or commercial use.

This article was originally published in the International Encyclopedia of the Social& Behavioral Sciences, 2nd edition, published by Elsevier, and the attached copy

is provided by Elsevier for the author’s benefit and for the benefit of theauthor’s institution, for non-commercial research and educational use including

without limitation use in instruction at your institution, sending it to specificcolleagues who you know, and providing a copy to your institution’s administrator.

All other uses, reproduction and distribution, includingwithout limitation commercial reprints, selling orlicensing copies or access, or posting on open

internet sites, your personal or institution’s website orrepository, are prohibited. For exceptions, permission

may be sought for such use through Elsevier’spermissions site at:

http://www.elsevier.com/locate/permissionusematerial

From Kraft, T., 2015. von Humboldt, Alexander (1769–1859). In: James D. Wright(editor-in-chief), International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences,

2nd edition, Vol 25. Oxford: Elsevier. pp. 279–285.ISBN: 9780080970868

Copyright © 2015 Elsevier Ltd. unless otherwise stated. All rights reserved.Elsevier

Author's personal copy

von Humboldt, Alexander (1769–1859)Tobias Kraft, Institut für Romanistik, Universität Potsdam, Potsdam, Germany

� 2015 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Abstract

Alexander von Humboldt (1769–1859) made essential contributions to a variety of disciplines and branches of knowledge,namely astronomy, geography, mineralogy, electrophysiology, political sciences, cartography, colonial history, and culturalanthropology. Humboldt’s understanding of nature as a system of dynamic and interrelated phenomena, based on empiricalstudies, puts an end to natural history as a branch of philosophical speculation and stands at the threshold of modern science.Its roots can be traced from his American oeuvre until the Kosmos. His abundant reflections on the history of Europeancolonization as well as his attempt to develop global comparative studies of natural phenomena have recently been presentedas an important element in the history of globalization discourse.

Humboldt, Alexander von (1769–1859)

Alexander von Humboldt, likely the most famous Europeannaturalist and scientific traveler in the nineteenth century,made essential contributions to a variety of disciplines andbranches of knowledge, namely astronomy, physical andapplied geography, geodesy, mineralogy, electrophysiology,political sciences, cartography, colonial history, and culturalanthropology. Several fields of study emerge from Hum-boldt’s works: plant (or phyto-)geography, pre-Columbianstudies, political geography, and modern climatology. Hum-boldt’s understanding of nature as a system of dynamic andinterrelated phenomena, based on empirical studies, puts anend to natural history as a branch of philosophical specula-tion and stands at the threshold of modern science. Threetitles of Humboldt’s vast oeuvre stand out the most torepresent the literary and aesthetic significance of his works:the Relation historique (Personal Narrative) describes hisAmerican travels in the genre of scientific travel literature, andthe other two, namely Ansichten der Natur (Views of Nature)and Kosmos, are the key elements of his reformist efforts ofdemocratizing knowledge, inspiring a sway of popular sciencebooks in the second half of the nineteenth century.

Today, his reflections on the interconnectedness betweenhuman settlement and natural resources are gaining attentionof studies on historical climate change, biodiversity, andecocriticism. His abundant reflections on the history of Euro-pean colonization as well as his attempt to develop globalcomparative studies of natural phenomena have recently beenpresented as an important element in the history of global-ization discourse. Humboldt’s holistic model of science isconsidered as a precursor for today’s transdisciplinaryapproaches. It represents an intellectual practice of connectingand intertwining different norms and formations of knowl-edge, with a coherent pattern traceable from his Americanoeuvre until the Kosmos.

Youth, Education, and European Travels (1769–99)

Not all of this was evident right from the start. Born on 14September 1769 at Berlin, Humboldt’s youth was largelycharacterized by early failure, physical delicacy, and frustration.

Apparently less brilliant and less motivated than his olderbrother Wilhelm, Alexander had to endure the long hours ofinstruction from many of, indeed first class, private educatorsthat frequented Schloss Tegel in his early years. At the age of 16,the first visits to Henriette Herz’s progressive salons put an endto the deprivation Alexander had felt so strongly, and intro-duced both the brothers to the brightest minds of theenlightened Berlin. The following years were dedicated to thestudy of cameralism, economics, natural history, mathematics,anthropology, physics, and languages at Frankfurt/Oder, Göt-tingen, and Hamburg. Nevertheless, it was another discipline,botany, that attracted his main attention in these years. His firstmentor, the Berlin botanist Carl Ludwig Willdenow, intro-duced Alexander to his collection of exotic specimen from thetropics. Soon, the inspiring sessions with Willdenow boostedhis desire for expedition, travel, and first-hand experience.During a stay in Mainz he was introduced to Georg Forster,who would become his travel companion on a voyage throughEurope in 1790. It was with Forster, a member of the secondCook expedition, that Humboldt not only witnessed therevolutionary energy of Paris, but also the cosmopolitan spiritof London, where he met Sir Joseph Banks and attendedsessions at the Parliament. These weeks were to become crucialfor the initiation of the adventurous, the ambitious and thepolitical Humboldt – the restless traveler, prolific author, andfuture diplomat.

Back in Prussia and after completing his studies of miner-alogy at the famous Bergakademie Freiberg (1791–92), Hum-boldt was all prepared for a promising career as Prussianmining director. His instructive manuals and practical inven-tions soon led to major improvements in the productivity andworking conditions of the mines he supervised. Experiments inelectrophysiology and the chemistry of plants were to follow,spreading his name in the scientific community of his days. Insearch of the ‘forces of life’ (Lebenskräfte), Humboldt developedthe idea of the harmony of elements in the inner organizationof all living organisms, a concept that fully crystallized ina famous note he would jot down in his American travel diaryin 1800: ‘Everything is interrelated’ (Alles ist Wechselwirkung).This conviction marks the epistemic nucleus of the Hum-boldtian approach, which also shaped the Kosmos in the notionof ‘nature is unity in diversity’ (Natur ist Einheit in der Vielheit).Unsurprisingly, the first sketches for a ‘physical description of

International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, 2nd edition, Volume 25 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-097086-8.61218-7 279

International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, Second Edition, 2015, 279–285

Author's personal copy

the world’ (physique du monde/Physikalische Geographie) dateback to these days.

The year 1796 marked a turning point in Humboldt’s earlycareer. With the death of his mother, Alexander inheriteda large fortune, providing means for realizing his aspiration forscientific expedition. He immediately resigned from his publicoffices and from there on, his every activity was conceived aspreparatory: acquiring only the finest scientific instruments,networking in Paris (with Delamétherie, Borda, Delambre,Laplace, Lamarck, and Cuvier), finding a travel companion (theFrench physician and botanist Aimé Bonpland), measure-ments, travels through Spain, new measurements, and finally,soliciting a travel pass through the Americas from King CarlosIV. With diplomatic skill and the backing of the Spanishminister Urquijo, the petition succeeded. On 5 June 1799,Humboldt and Bonpland set off from the port of La Coruña toAmerican shores: the first independent travel expedition inmodern times was about to begin.

The American Voyage and the Yearsin Paris (1799–1829)

“We run around like fools; during the first three days, we didnot identify a thing, always dropping one object to pick upanother one. Bonpland claims that he will loose his mind if themarvels do not stop soon. But even more beautiful than each ofthese wonders by itself is the impression of the entirety of thispowerful, luxuriant and at the same time so light, cheerful, andmild plant life. I feel that I will be very happy here and thatthese impressions will continue to cheer me in the future”(Humboldt in Kutzinski et al., 2012).

In this first letter from the New Continent, as he liked tophrase it, Humboldt puts in a nutshell the fascination he wouldfeel for the tropics through his entire life. These lines, written tohis brother Wilhelm on 16 July 1799 from the Venezuelan portof Cumaná, seem to inscribe Humboldt into the tradition ofSpanish chronicles from the conquista days, when America’snature (and people) were miraculous, exotic, and exuberant.But Humboldt’s American Voyage was never aimed at‘marvelous possessions’ (Greenblatt). The gaze at beautifulwonders soon gave way to thorough science in the field –

countless measurements on ships and donkeys, in valleys andon mountain peaks, research in the colonial archives and atarcheological sites, and an ever-increasing specimen collectionof America’s flora and fauna.

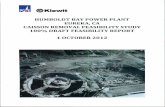

The 5-year voyage (1799–1804) had the travelers depart fromSpain for a stopover in the Canary Islands to land at the coast ofthe Venezuelan provinces, traverse the hinterland of New Gran-ada, Cuba, Cartagena, the South American Cordilleras, Bogotá,Quito, Lima, Guayaquil, New Spain, Cuba again, and for a lastbrief stop, the United States, before returning to Europe. He cameinto contact with all social classes of the Spanish colonial world:Spanish officials, European merchants, indigenous servants,workers and peasants, enslaved Africans, catholic missionaries,and creole elites from all branches of society: politics, economics,culture, and academia. He ascended many of the most prom-inent mountains and volcanic peaks of the continent, amongthem Mount Chimborazo near Quito, then considered thehighest summit in the world. In 75 days, he traveled 1500 miles

in a pirogue, up and down the Orinoco, Meta, and CasiquiareRivers, lending final proof to the older hypothesis of an intricateconnection between the Orinoco and Amazonas network. Hisinterests and research encompassed botany, zoology, clima-tology, geology, economy, cartography, political geography, andcultural history of the ‘New Continent’ (Figure 1).

After his return to Europe, Humboldt undertook severaljourneys to complete his American antiquarian research, amongthem a sojourn in Rome, where he would meet his brotherWilhelm and undertake a ‘voyage d’archive’ (Bourguet, 2011)through the Vaticane codices in search of Mesoamericanmanuscripts. Already an international star of science, Humboldtwas faced with a general public curiosity for his travel accountsand the EuropeanRépublique des lettres, awaiting the results of hisscientific findings. The very successful Ansichten der Natur(Tübingen 1808) fulfilled the expectations of the former. Theircolorful and vivid descriptions of the American landscapescombined literary composition with a naturalist framing,introducing Humboldt’s concept of a physiognomy of nature.

Publishing in Paris

Even though the 1st edition of Ansichten was all about hisAmerican journey, Humboldt did not consider them to be partof the 29 volumes that he would publish in the followingdecades upuntil 1838, when the last part of Humboldt’s historyof colonial discovery, the Examen critique, was to appear inParis. His American oeuvre was aimed at his peers and targetedtwo goals: to deliver specific studies, findings, and measure-ments to the specialized scholar, and to provide, at the sametime, a general and all-encompassing tableau of the physical,political, and cultural character of the tropics. Publishing mostof his American works from Paris also meant publishing themin French, a matter of course for Humboldt, who had beenraised bilingually from his earliest youth. Needless to say, it isthe French capital, where Humboldt’s scientific ambitions wereto find their most natural habitat. Paris would become thecenter of his life from 1809 to 1827 and a frequent place toreturn to, whether in private or on a diplomatic mission withassignments from the Prussian King. The city offered all heneeded: the most renowned institutions of science and culture,and the best publishing houses for his demanding task toproduce his findings in opulent quarto and folio volumes.Some of Humboldt’s plans were to fall short of his ownexpectations, especially his time frame: instead of 3 years, heneeded 30 years for the project, the simultaneous publicationof all his writings in both French and German had to beabandoned soon in favor of the French, his Relation historiquedespite taking almost 20 years in the making was nevercompleted, and several intents to publish revised editions ofsome of his titles failed in the light of more urgent matters.

In his times, only comparable to a work like the Descriptionde l’Égypte, Humboldt’s Voyage aux régions équinoxiales duNouveau Continent is abundant in its content and, at times,puzzling in its complex network of references. It can certainlybest be described by the impact its various publications left onthe contemporary academic and political landscape.

As one of its earliest outcomes, Humboldt’s Essay on theGeography of Plants (Paris, Tübingen 1807, Trans. Humboldtand Bonpland, 2009), became a founding document for the

280 von Humboldt, Alexander (1769–1859)

International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, Second Edition, 2015, 279–285

Author's personal copy

Equator

°0W°03W°06W°09W°021

30°N

0°

June-July 1799

Dec. 1800

Feb.-Mar. 1803

Mar. 1

804

May

180

4

July 1804

I

II

III

IV

V

VI

La Coruña

Santa Cruz

Cumaná Caracas

S. Carlos

Angostura

Havana Trinidad

Cartagena

Bogotá

Quito

Lima

Guayaquil

Acapulco

Mexico- City

Veracruz

Philadelphia Washington

Bordeaux

June 1799

July 16th 1799

June 5th 1799

May 1800

June-July 1800

Mar. 1801

July-Sep. 1801

Jan.-June 1802

Oct.-Dec. 1802

Mar. 22nd 1803

Jan. 1803

May-July 1804

Aug. 1st 1804

Canary Islands Gulf of Mexico

P a c i f i c O c e a n

A t l a n t i c O c e a n

U n i t e d S t a t e s

N e w - S p a i n

N e w -

G r a n a d a

P e r u

Azimuthal equidistant projection

Alexander von Humboldt's American expedition 1799–1804

I With the spanish corvette "Pizarro" from La Coruña over the Canary Islands to Cumaná

II 75-days journey with Bonpland, on the Orinoco and the Rio Negro

III With the ship from Nueva Barcelona to Havanna, 3-month sojourn on Cuba, over Trinidad to Cartagena

IV Through today's Colombia, Ecuador and Peru to Lima

V From Guayaquil to Acapulco, longer sojourn in Mexico City and back to Havanna over Veracruz

VI With the cargo ship "Concepción" to Phi- ladelphia, Washington, with the french Frigate "La Favorite" to Bordeaux

Expedition way City/Stopping place Spanish Viceroys and United States

Figure 1 Map of Humboldt’s American travel route. Original file from: Wikimedia Commons (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:AvHumboldts_Americatravel_map_en.svg) The file is licensed under the CreativeCommons Attribution-Share Alike 2.5 Generic license.

vonHum

boldt,Alexander

(1769–1859)281

Intern

ational

Encyclo

pedia

oftheSocial

&Behavio

ralScien

ces,Seco

ndEditio

n,2015,279–285

Author's personal copy

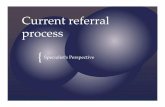

comparative study of plants in their spatial and climaticdistribution, articulating an integrative science of the earth,which encompasses most of today’s environmental sciences(Jackson, 2009). The iconic image of this newly drafted disci-pline – the ‘Physical Tableau of the Equitorial Regions’ � waslikely its main attraction (Figure 2). Much more than anillustration to the text, the ‘tableau’ functions as a visualizationof the discipline itself, its intellectual ambition, and (inter-)disciplinary scope. Both in the book and in the ‘tableau’ itself,Humboldt first experimented with a conceptual framing ofdialogue between text and image that later became thecornerstones of his geographic, political, and cultural atlases(Kraft, 2014). Together with applying geological profilesformerly used in mining to outline the physical character ofterritories like Spain and Mexico, these visual breakthroughsput Humboldt’s name among the most innovative examples ofdata visualization in the nineteenth century. Humboldt’s boththeoretical and visual concepts of isothermal lines providedcartographic representation to climate research, an innovationthat is still in use today. With Humboldt’s isotherms, world-wide comparative climatology became pictorial.

The Political Humboldt

Recently, more attention has been given to the political side ofHumboldt’s oeuvre. For a Latin American audience, this is, ofcourse, nothing new. His two major writings Political Essay onthe Kingdom of New Spain (Paris 1808–11/1825–27, Trans.Humboldt, in press) and Political Essay on the Island of Cuba(Paris 1826, Trans. Humboldt, 2011) played a major role in thestruggle for independence during the first decades of thecentury. For Humboldt’s voluminous text on New Spain, this iseven more true as he composed and published his writings andsubstantial cartographic material on New Spain on the eve ofits final decline, that is, just at the moment, when the creoleelites were to initiate national liberation from the Spanishdominion. Humboldt, in the history of his reception oftencoined as the ‘second,’ that is, the ‘scientific discoverer ofAmerica,’ was thereby enthroned as the programmaticprecursor of future Mexico. The Mexican historian and politi-cian Lucas Alamán left no doubt about the foundationalcharacter of Humboldt’s work when he wrote to Humboldtthat the constitutional assembly of 1824 used his Political Essayas inspiration and guidance for the tasks ahead. Clearly, bothtexts – as much his study on New Spain as the one on Cuba –

were to set new standards by their concise study, compositionand presentation of geography, politics, economics, demog-raphy, and social analysis of the colonies. Humboldt’s essaysgave way to new American self-awareness: up-to-date in itsdata – gained from proper measurements, from thorough workin the archives, and contributions from his countless corre-spondents – independent in its judgment and overwhelminglyprecise in its cartographical mapping.

In Cuba, matters were different: his work was censured onthe spot, and independence far away. The censorship waslargely due to Humboldt’s crystal clear stand on the issue ofslavery, undoubtedly the foremost topic in sociopolitical,economic, and ethical debates in nineteenth-century Cuba. In1791, the enslaved in the French colony of Saint-Dominguehad begun the first successful large-scale insurrection in

history, known as the Haitian Revolution (1791–1804). WithSaint-Domingue’s economy in ruins, the demand for Cubansugar increased, and so did Cuba’s demand for slaves. Inaddition to infusing the Cuban sugarcane industry with thou-sands of fleeing French planters and sugar engineers, theHaitian Revolution also generated widespread fears of anotherrevolution. During his two visits to the island (1800–01/1804),Humboldt gained a close impression of the shock-waves thatthe Haitian Revolution had left among the Cuban oligarchy.He mentions the ‘troubles in Saint-Domingue’ repeatedly inthe Political Essay on the Island of Cuba, pointing to theprogressive agenda that Havana’s merchant guild and PatrioticSociety had pursued in the 1790s and again in 1811. But thatdid not much improve the working conditions of Cuba’senslaved, whose fate – as Humboldt had argued – could onlylie in the complete abolition of slave labor. However, the bookwas to take another turn in its international reception. In 1856,the US journalist, pro-slavery activist, and intimate expert inCuban affairs, John S. Thrasher, published an English trans-lation of Humboldt’s text. In The Island of Cuba, Thrasher hadmade significant changes, omitting Humboldt’s section onslavery and making countless emendations that Humboldthimself saw as ‘politically motivated.’ In the eyes of the Englishreader, Humboldt had turned from a vehement abolitionist toa mild reformer with sympathies for the ruling oligarchy ofsugar planters. That same year, Humboldt complained aboutThrasher’s manipulations in a public letter that was immedi-ately translated to English and appeared in numerous news-papers across the U.S. The affair was even to influence publicopinion during the Presidential campaign between JamesBuchanan and the Humboldt admirer John C. Frémont.Humboldt’s fierce denials in this scandal should have restoredhis reputation, but in fact, the stain of political opportunism oreven reactionary blindness to social problems would remainwith the (English-speaking) readership until the recent times.

The Mesoamerican Cultures

What has been called Humboldt’s ‘imperial gaze,’ in otherwords his contribution to the imperial politics of the latenineteenth century, can also be read as late reflexes of this (attimes intentional) misreading. Yet it is not coherent with eitherhis political or his cultural-anthropological writings. On thecontrary: Humboldt’s political criticism went far beyond that ofmost of his contemporaries. In his Political Essay on the Kingdomof New Spain, he openly condemned the Mexican creole elitesand colonial administration for their complete lack of politicalvision and inaptness to guarantee legal equality to the indige-nous populations. In his Political Essay on the Island of Cuba, asoutlined in the preceding paragraphs he strongly rebuked theagroeconomic complex of mass slavery and monoculturalplantations. In both texts, as well as in countless politicalactivities during his lifetime, he argued for political reform bothin the Americas and in Europe, in favor of individual freedom,political participation, and liberal economics. Among the firstEuropeans in nineteenth century to thoroughly study thearcheological remains of Mesoamerican cultures, Humboldtmade seminal contributions to the cultural history, mythology,and archeoastronomy of the Americas in his ‘pittoresque atlas,’the Views of the Cordilleras and Monuments of the Indigenous

282 von Humboldt, Alexander (1769–1859)

International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, Second Edition, 2015, 279–285

Author's personal copy

Figure 2 Tableau physique des Andes et Pays voisins.; Humboldt, A. von, Bonpland, A., 1807. Essai sur la Géographie des Plantes accompagné d’un tableau physique des régions équinoxiales. Fondé surdes mesures exécutées, depuis le dixième degré de latitude boréale jusqu’au dixième degré de latitude australe, pendant les années 1799, 1800 1801, 1802 et 1803. Avec un planche. Schoell, Cotta, Paris,Tübingen. Original scan from: Biodiversity Heritage Library (http://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/9869921), Usage is free, since copyright is expired and/or not further specified, see http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/bibliography/9309#/summary and http://biodivlib.wikispaces.com/LicensingþandþCopyright.

vonHum

boldt,Alexander

(1769–1859)283

Intern

ational

Encyclo

pedia

oftheSocial

&Behavio

ralScien

ces,Seco

ndEditio

n,2015,279–285

Author's personal copy

Peoples of America (Paris 1813, Trans. Humboldt, 2012a). As anearly example of nineteenth century anthropology andethnology, Humboldt’s keen interest in indigenous cultureshelped to shed a new light not just on the remains of perishedsocieties, but also on the originality of Native American art,sparking “a movement to reconsider the aesthetic value of non-European art that eventually led to a new, ‘modern’ aesthetic’”(Kutzinski et al., 2012). Humboldt’s American nature, inconsequence, is not a vast territory of unpopulated land ready tobecome the object of European desires, as some have suggested,but a space of complex histories, layers of time, and language(s),that Humboldt not only reflects upon in his text, but alsovisually in his American cartography.

The American oeuvre, encompassing 29 volumes with over1400 copper plates, was to become the largest and the mostexpensive scientific work a single person had and has everpublished. Its impact reached two continents, ruined severalpublishing houses, and finally, Humboldt’s finances as well.This was one of the reasons why he saw himself forced to leavehis beloved Paris to return to Berlin in 1827 and take anappointment by his King, Friedrich Wilhelm III, to serve aschamberlain at the Prussian court.

The Russian–Siberian Voyage (1829)

By that time, his plans for an expedition through Russia andSiberia had become very determined. The first sketches of thisresearch program date back to 1812. Already then, Humboldtknew that the major tasks of his scientific masterplan were stillahead. In order to conceive the physical world as a cosmos offorces, natural phenomena, and relations, Humboldt needed anAsian counterpart to his American experience. But unlike duringhis travels through the ‘NewContinent,’Humboldt had becometoo famous and financially too dependent to undertake sucha mission on his own. As head of a group of naturalists(Humboldt, Christian Gottfried Ehrenberg, and Gustav Rose),Humboldt had to follow a predefined travel route, withwelcoming committees at every station, close surveillance byCossack horsemen and a clear division of labor, in which hisown contribution was strictly limited to mere scientific output.The reputation of Humboldt’s political stance over questions ofindividual liberty, peonage, and social reform seemed toomuchof a risk for the Russian Emperor Nicholas I. Humboldt’sacceptance of these hard-to-bear conditions can only beexplained by the credo of his global comparative project, forwhich the travels to Central Asia were essential. Already 60 yearsof age, he knew that such an opportunity was improbable tocome again. The travels became an Asian tour de force, with haltsin Königsberg, Riga, Saint Petersburg, Moscow, the Urals, AltaiMountains, a gaze at the Chinese borders, the great Siberianplanes, Omsk, the Caspian Sea, the return to Moscow, and,finally, Berlin. In just about 9 months, the expedition hadtraveled more than 10 000 miles, mostly at night. Restricted ashe was in his scientific endeavors, Humboldt focused onmagnetic, barometric, and astronomic findings, mining enter-prises, and comparative analyses between the American andAsian nature. In the 30 years between his first and the secondgreat voyage, much had changed. As Humboldt stated in a letterto Wilhelm from September 1829, the remarkable pace of hissecond grand tour correlated with the acceleration of modern

science, better instruments, and the refinement ofmethods in allbranches of knowledge. Yet despite the modern times, it wouldtake him another 14 years to complete his studies and accom-modate the results of the Russian–Siberian Voyage in the threevolumes of Asie Centrale (Paris 1843). They were to pioneer theera of modern geology on Inner Asia.

The Final Chapter: Scientific Networks andHumboldt’s Kosmos (1829–59)

Already in 1828, Humboldt had started to build new scientificnetworks in the Prussian capital. A conference under his directionbrought together 600 naturalists and physicians in Berlin, wherehe initiated numerous activities to propel the city’s academicculture and foster new scientific institutions. The goal was as clearas it was ambitious: Humboldt wanted Berlin to becomea centerpiece place of modern science. His ‘Kosmos lectures’ atthe University and the Singakademie were to attract crowds ofmore than 800 people eager to hear Humboldt’s lessons on thegeneral aspects of the physical world (‘Allgemeines Natur-gemälde’). Even though related to the successive appearance ofhis Kosmos from 1845 to (posthumously) 1862, the lectures haveto be seen more in the light of raising public awareness forscientific knowledge and education. The idea of the Kosmos asa stand-alone work in its own right dated back much earlier,envisioned decades before the lectures in his Geography of Plantsand fully conceptualized in a letter to his friend Karl AugustVarnhagen von Ense in 1834. The ‘work of my life’ was meant toembrace it all and “present an epoch in the mental developmentof man as regards his knowledge of nature” (Humboldt andVarnhagen von Ense, 1860). Humboldt’s goal was to satisfyboth: the specialist and the general public, the professor and thestudent. As the first tranches of Kosmos were to appear in 1845,readers’ expectations had risen to unprecedented levels. By thetime the second volume became available, German booksellerswere overrun by public demand and had to commissionmultiplereprints. British and US-American publishers competed withthree simultaneous editions, while rushing to present new andupdated translations of the Ansichten der Natur and the PersonalNarrative. Kosmos was to become the popular epitome of Hum-boldtian thinking: modeling nature in its inherent connectivity,its network-like, organic intertwinement, and, finally, in its rela-tion to man. “For the study of nature was, for Humboldt,inseparable from the study of themind in its material, social, andcultural context. This reflexivity of mind, society, and naturebecame his overriding argument” (Walls, 2005).

Humboldt was not to see the final volume of his Kosmospublished, when it finally came out in 1862. Quite literally withthe quill in his hands, he died on 6 May 1859, at the age of 89,in Berlin.

The Present: Proliferating Humboldt Studies, NewEditions, the American Travel Diaries

Current studies on the life, works, and scientific achievementsof Alexander von Humboldt encompass a wide array of disci-plines and scholarly fields (history of science, colonial history,postcolonial studies, art history, cultural studies, poetics ofscience, history of ideas, epistemology, environmental studies,

284 von Humboldt, Alexander (1769–1859)

International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, Second Edition, 2015, 279–285

Author's personal copy

and ecocriticism). What we might call a rather recent renaissanceof Humboldt studies is largely due to a decade-long effort(1997–2006) around the bicentennial of the American travels(1799–1804), when a series of large-scale Humboldt exhibitsand conferences around the globe (Mexico, Cuba, Venezuela,Germany, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Spain, England, and Aus-tria) reminded the scientific and general public of the historicand contemporary relevance of one of Europe’s most eminentfigures of the nineteenth century. These events set the floor fornumerous editorial projects (i.e., Humboldt, 1991, 1998,2004a,b, 2009b,c, 2011, 2012a,b, in press), which wereaimed at recovering the original Humboldtian text as a responseto a history of reception, in which Humboldt was largely readand commented upon based on highly abbreviated and oftenpoorly translated editions of his works. These new editions havegiven the international scientific community, mostly in theGerman-, Spanish-, and English-speaking world, a restoredtextual ground, an elevated awareness for the impact Humboldthad on his contemporaries, and for the significance his workshave for today’s readers. The recent acquisition of Humboldt’sAmerican Travel Diaries (December 2013) by a consortium ofGerman public and private institutions under the auspices ofthe Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin (Prussian Cultural HeritageFoundation) will certainly add to this, as it provides an essentialelement in fully understanding Humboldt’s place in the studyof scientific practices and travel literature in the nineteenthcentury.

See also: Anthropology: Overview; Cartography; Colonialism,Anthropology of; Colonization and Colonialism, History of;Environmental Sciences; Geography: Overview; Mesoamerica,Archaeology of; Nature and Society in Geography; PoliticalGeography; Science, History of; South America: SocioculturalAspects; von Humboldt, Wilhelm (1767–1835).

Bibliography

Beck, H., 1959. Alexander von Humboldt. In: Von der Bildungsreise zur For-schungsreise 1769–1804, Band 1. Franz Steiner Verlag, Wiesbaden.

Beck, H., 1961. Alexander von Humboldt. In: Vom Reisewerk zum “Kosmos”1804–1859, Band 2. Franz Steiner Verlag, Wiesbaden.

Bourguet, M.-N., Janvier-Mars 2011. Notes romaines. Le ‘voyage d’archive’d’Alexander von Humboldt (1805). Études germaniques 66 (1), 21–44.

Ette, O., Hermanns, U., Scherer, B.M., Suckow, C. (Eds.), 2001. Alexander vonHumboldt: Aufbruch in die Moderne. Akademie Verlag, Berlin.

Ette, O., 2001. The scientist as Weltbürger: Alexander von Humboldt and the beginningof cosmopolitics. HiN – Internationale Zeitschrift für Humboldt-Studien 2 (2). http://www.hin-online.de (accessed 13.12.13.).

Ette, O., 2009. Alexander von Humboldt und die Globalisierung: Das Mobile desWissens. Insel, Frankfurt am Main, Leipzig.

Fiedler, H., Leitner, U., 2000. Alexander von Humboldts Schriften: Bibliographie derselbständig erschienenen Werke. Akademie Verlag, Berlin.

Hein, W.-H. (Ed.), 1987. Alexander von Humboldt: Life and Work. C.H. BoehringerSohn, Ingelheim am Rhein.

Humboldt, A. von, Varnhagen von Ense, K.A.L.P., 1860. Letters of Alexander vonHumboldt, Written between the Years 1827 and 1858, to Varnhagen von Ense.Together with Extracts from Varnhagen’s Diaries, and Letters from Varnhagen andOthers to Humboldt. Authorized and translated from the German, with explanatorynotes and a full index of names. Trübner & Co., London.

Humboldt, A. von, Bonpland, A., 1971–1973. Voyage de Humboldt & Bonpland:Voyage aux régions équinoxiales du Nouveau Continent. Facsimilé intégrale duédition de Paris 1805–1834. Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, Amsterdam, New York.

Humboldt, A. von, 1991. Reise in die Äquinoktial-Gegenden des Neuen Kontinents. In:Herausgegeben von Ottmar Ette. Mit Anmerkungen zum Text, einem Nachwort undzahlreichen zeitgenössischen Abbildungen sowie einem farbigen Bildteil, Band 1.Insel, Frankfurt am Main, Leipzig.

Humboldt, A. von, 1998. Ensayo político sobre la Isla de Cuba (Edición de Miguel ÁngelPuig-Samper, Consuelo Naranjo Orovio, Armando García González). Edición DoceCalles, Junta de Castilla y León, Madrid.

Humboldt, A. von, 2004a. Kosmos: Entwurf einer physischen Weltbeschreibung. Ediertund mit einem Nachwort versehen von Ottmar Ette und Oliver Lubrich. Eichborn,Frankfurt am Main.

Humboldt, A. von, 2004b. Ansichten der Kordilleren und Monumente der eingeborenenVölker Amerikas. Aus dem Französischen von Claudia Kalscheuer. Eichborn,Frankfurt am Main. Ediert und mit einem Nachwort versehen von Oliver Lubrich undOttmar Ette.

Humboldt, A. von, 2009a. Mein vielbewegtes Leben: Der Forscher über sich und seineWerke. Ausgewählt und mit biographischen Zwischenstücken versehen von FrankHoll. Eichborn, Frankfurt am Main.

Humboldt, A. von, 2009b. Kritische Untersuchung zur historischen Entwicklung dergeographischen Kenntnisse von der Neuen Welt und den Fortschritten dernautischen Astronomie im 15. und 16. Jahrhundert: Mit dem geographischen undphysischen Atlas der Äquinoktial-Gegenden des Neuen Kontinents Alexander vonHumboldts sowie dem Unsichtbaren Atlas der von ihm untersuchten Kartenwerke.Mit einem vollständigen Namen- und Sachregister. Nach der Übersetzung aus demFranzösischen von Julius Ludwig Ideler ediert und mit einem Nachwort versehenvon Ottmar Ette. Insel, Frankfurt am Main, Leipzig.

Humboldt, A. von, Bonpland, A., 2009. Essay on the Geography of Plants. TheUniversity of Chicago Press, Chicago, London. Edited with an introduction byStephen T. Jackson (Sylvie Romanowski, Trans.).

Humboldt, A. von, 2011. Political Essay on the Island of Cuba: A Critical Edition. TheUniversity of Chicago Press, Chicago, London. Edited with an Introduction by VeraM. Kutzinski and Ottmar Ette. (J. Bradford Anderson, Vera M. Kutzinski, and AnjaBecker, Trans.) With Annotations by Tobias Kraft, Anja Becker, and Giorleny D.Altamirano Rayo.

Humboldt, A. von, 2012a. Views of the Cordilleras and Monuments of the IndigenousPeoples of the Americas: A Critical Edition. Edited with an Introduction by Vera M.Kutzinski and Ottmar Ette. (J. Ryan Poynter, Trans.) Annotations by GiorlenyAltamirano Rayo and Tobias Kraft. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago,London.

Humboldt, A. von, 2012b. Vistas de las Cordilleras y Monumentos de los PueblosIndígenas de América. Traducción de Gloria Luna Rodrigo y Aurelio RodríguezCastro. Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, Marcial Pons Historia, Madrid.

Humboldt, A. von. Political Essay on the Kingdom of New Spain: A Critical Edition.Edited with an Introduction by Vera M. Kutzinski and Ottmar Ette. The University ofChicago Press, Chicago, London, in press.

Jackson, S.T., 2009. Introduction: Humboldt, Ecology and the Cosmos, in: Essay on theGeography of Plants. Edited with an introduction by Stephen T. Jackson. (SylvieRomanowski, Trans.). The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, London, pp. 1–46(this is Humboldt 2009b).

Kraft, T., 2014. Figuren des Wissens bei Alexander von Humboldt. Essai, Tableau undAtlas im amerikanischen Reisewerk. De Gruyter, Berlin, Boston.

Kutzinski, V.M., Ette, O., Walls, L.D. (Eds.), 2012. Alexander von Humboldt and theAmericas. edition tranvía, Berlin.

Minguet, C., 1997. Alexandre de Humboldt: Historien et géographe de l’Amériqueespagnole (1799–1804). L’Harmattan, Paris, Montreal.

Päßler, U., 2009. Ein Diplomat aus den Wäldern des Orinoko: Alexander vonHumboldt als Mittler zwischen Preußen und Frankreich. Franz Steiner Verlag,Stuttgart.

Rupke, N.A., 2005. Alexander von Humboldt: A Metabiography. Peter Lang, Frankfurtam Main, Berlin, Bern u.a.

Sachs, A.J., 2006. The Humboldt Current: Nineteenth-Century Exploration and theRoots of American Environmentalism. Viking, New York.

Walls, L.D., 2005. Rediscovering Humboldt’s environmental revolution. EnvironmentalHistory 10 (4), 758–760.

Relevant Websites

http://www.avhumboldt.de – Alexander von Humboldt Informationen online (German,Spanisch, English, French).

http://www.bbaw.de/forschung/avh – Alexander von Humboldt Research Group at theBerlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences and Humanities.

http://www.avhumboldt.de/?page_id¼469 – Humboldt Digital – Online Bibliography ofdigital facsimiles of Humboldt’s works.

http://www.avhumboldt.net – The Humboldt Digital Library.http://sitemason.vanderbilt.edu/site/ld5WVy/hie – HiE – Alexander von Humboldt in

English. Project website.http://www.hin-online.de – HiN – Humboldt im Netz. International Review for

Humboldtian Studies (ISSN:1617-5239).

von Humboldt, Alexander (1769–1859) 285

International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, Second Edition, 2015, 279–285

Author's personal copy

![HiN : Alexander von Humboldt im Netz [III, 4 (2002)] - publish.UP](https://static.fdokumen.com/doc/165x107/6337acd740a96001d4010ca2/hin-alexander-von-humboldt-im-netz-iii-4-2002-publishup.jpg)