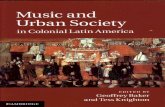

"Gold was music to their ears": Conflicting sounds in Santafe (Nuevo Reino de Granada), 1540-1590

Van Wolputte, S., Deprez, B. (2009). Guy Tachard, S.J. Reis na Siam (1687). In: Begheyn P., Deprez...

Transcript of Van Wolputte, S., Deprez, B. (2009). Guy Tachard, S.J. Reis na Siam (1687). In: Begheyn P., Deprez...

JESUIT BOOKS

IN THE LOW COUNTRIES1540-1773

A Selection from the Maurits Sabbe Library

MAURITS SABBEBIBLIOTHEEKFACULTEIT GODGELEERDHEID

PEETERS

LEUVEN

2009

Edited by

Paul Begheyn S.J., Bernard Deprez, Rob Faesen S.J., and Leo Kenis

With the collaboration of Eddy Put, Frans Chanterie S.J.,and Lieve Uyttenhove

V

Contents

Preface

Rob Faesen S.J. IX

The Maurits Sabbe Library and Its Collection of Jesuit Books

Leo Kenis XI

Jesuits in the Low Countries and Their Publications

Paul Begheyn S.J. XXI

Peter Canisius S.J., Catechismus (1558) (P. Begheyn S.J.) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1

Jan David S.J., Schild-wacht (1602) (D. Vanysacker) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4

Frans de Coster S.J., Libellus sodalitatis (1607) (M. King) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8

Pedro de Ribadeneira S.J., Vita beati/sancti patris Ignatii Loyolae (1610/n.d.)

(W.S. Melion) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12

Andries Schott S.J., Adagia sive Proverbia graecorum (1612) (G. Tournoy) . . . . . . . . . . . 18

Juan de Polanco S.J., Directorium breve (1613) (R. A. Maryks) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 22

Nicolas Trigault S.J., Litterae Societatis Iesu e regno Sinarum (1615) (N. Standaert S.J.) 26

Der Iesuiten negotiatie (1616) (P. Begheyn S.J.) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 30

Lodewijk Makeblijde S.J., Den berch der gheestelicker vreughden (1618)

(P. Begheyn S.J.) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 33

Annuae litterae Societatis Iesu anni M. DC. IV. (1618) (A. Delfosse) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 36

Frans de Coster S.J., Vierthien catholiicke sermoonen (1618) (G. Vanden Bosch) . . . . 40

Peter Wadding S.J., Disputatio theologica de praedestinatione et gratia (1621)

(M.W.F. Stone) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 44

Jean Bourgeois S.J., Leven lyden ende doodt (1623)/Vitae passionis et mortis mysteria

(1622) (R. Viladesau) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 48

José de Acosta S.J., Historie naturael en morael van de Westersche Indien (1624)

(J. Verberckmoes) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 54

Herman Hugo S.J., Obsidio Bredana (1626) (M. Gielis) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 58

Valentijn Bisschop S.J., Lof der suyverheydt (1626/1632) (M. Monteiro) . . . . . . . . . . . . . 64

Augustijn van Teylingen S.J., Devote oeffeninghe (1628) (P. Begheyn S.J.) . . . . . . . . . . . 67

Heribert Rosweyde S.J., Leven vande heylighe Maghet ende Moeder Godts Maria

(1629) (P. Begheyn S.J.) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 70

Carlo Scribani S.J., Christus patiens (1629) (P. Begheyn S.J.) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 72

VI

Virgilio Cepari S.J., Het leven van Ioannes Berchmans (1629) (R. Faesen S.J.) . . . . . . . . 74

Otto van Zijl S.J., Historia miraculorum B. Mariae Silvaducensis (1632) (B. Fahy) . 77

Willem Boelmans S.J., Theses mathematicae (1634) (A. De Bruycker) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 81

Corpus institutorum Societatis Jesu (1635) (S. Van Impe) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 86

Ignaas Derkennis S.J., Positiones sacrae (1638) (A.-É. Spica) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 92

Jerónimo Xavier S.J., Historia Christi Persice conscripta (1639) (T. Van Hal) . . . . . . . 96

Jean Vincart S.J., Sacrarum heroidum epistolae (1640) (A. Smeesters) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 100

Jacob Wijns S.J., De vita, et moribus R. P. Leonardi Lessii liber (1640) (T. Van Houdt) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 104

Jacques Damiens S.J., Tableau racourci (1642) (A. Delfosse) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 108

Jodok Kedd S.J., Statera veritatis (1646) (P. Begheyn S.J.) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 111

Maximilianus Sandaeus S.J., Societas Iesu amatrix, cultrix, imitatrix, Christi crucifixi

(1647) (R. Faesen S.J.) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 114

Carolus Werpaeus S.J., De raptu Manresano S. Ignatii libri IV (1647) (R. Faesen S.J.) 118

Famiano Strada S.J., De bello Belgico decas secunda (1648) (W. François) . . . . . . . . . . . 121

Gosuinus van Buytendyck, Den roemgierigen jesuyt (1648) (J. Roegiers) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 125

Joost Andries S.J., La perpetua croce (1650) (A. Catellani) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 129

Paul Rageneau S.J., Verhael van t’ gheen gheschiet is in de missie van de PP. der

Societeyt Iesu by de Hurons (1651) (J. Monet S.J., B. Deprez) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 133

Govert Henskens S.J., De episcopatu Traiectensi (1653) (M. Gielis) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 137

Jacob van der Straeten S.J., Practijcke van een particulier examen (1654) (J. Haers S.J., B. Deprez) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 140

Hendrik Engelgrave S.J., Lux evangelica (1654) (M. Van Vaeck) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 144

Antoon van Torre S.J., Dialogi familiares (1657) (E. Put) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 150

Blaise Pascal, Les provinciales (1659) (J. Roegiers) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 153

Adriaen Poirters S.J., Het heyligh herte (1659) (L. Roggen) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 157

Henry More S.J., Historia missionis anglicanae Societatis Iesu (1660) (M. Whitehead) 162

Martino Martini S.J., Novus atlas Sinensis (1662) (N. Golvers) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 166

Jan van Sambeeck S.J., Het geestelyck jubilee (1663) (P. Begheyn S.J.) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 170

Athanasius Kircher S.J., Mundus subterraneus (1665) (P. Begheyn S.J.) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 173

Sidronius Hosschius S.J., Elegiarum libri sex (1667) (D. Sacré) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 177

Cornelis Hazart S.J., Kerckelycke historie (1669) (J. van Gennip) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 182

Francis Line S.J., Explicatio horologii (1673) (P. Davidson) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 187

Friedrich Lamberts S.J., Septimana sancta (1673) (P. Begheyn S.J.) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 191

VII

François de Rougemont S.J., Historia Tartaro-sinica nova (1673) (N. Golvers) . . . . . . . 193

Ignatius of Loyola S.J., Geestelycke oeffeninghen (1673) (M.M. Mochizuki) . . . . . . . . . 196

Petrus Franciscus de Smidt, Hondert-jaerigh jubilé-vreught (1685) (G. Marnef) . . . . . 202

Guy Tachard S.J., Reis na Siam (1687) (S. Van Wolputte, B. Deprez) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 206

Daniël Huysmans S.J., Kort begryp (1690) and Leven ende deughden (1691)

(M. Monteiro) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 212

Philip Couplet S.J., Historie van mevrouw Candida Hiu (1694) (N. Golvers) . . . . . . . . 216

Koenraad Janning S.J., Apologia pro actis sanctorum (1695)

(B. Joassart S.J., B. Deprez) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 220

Onderwysinghe om te houden thien vrydaghen ter eeren van den H. Franciscus

Xaverius (1698) (F. Chanterie S.J.) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 224

Paolo Segneri S.J., Grouwelyckheyt der doodt-sonde (1702) (J. Jans) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 229

Appendix augustiniana (1703) (A.S.Q. Visser) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 233

André Tacquet S.J., Opera mathematica (1707) (J. Riche) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 237

Frans Nerrincq S.J., De Goddelycke voorsienigheydt (1710) (P. van Dael S.J.) . . . . . . 244

Jacques Coret S.J., Engel bewaerder (1711) (H. Geybels, B. Deprez) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 249

Thomae Philippo de Alsatia de Boussu gratulatur Societas Jesu (1716/1719) (G. Proot) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 252

Joseph-François Lafitau S.J., De zeden der wilden van Amerika (1731) (J. Verberckmoes) 257

Guillaume Hyacinthe Bougeant S.J., Le saint déniché (1732)

(A. Dabezies S.J., B. Deprez, E. Geleijns) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 261

Pierre de Charlevoix S.J., Histoire de l’isle Espagnole ou de S. Domingue (1733)

(W. Thomas) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 266

Wilhelm Nakatenus S.J., Hemels palmhof (1694/1740) (T. Clemens) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 270

De plafonds, of gallerystukken uit de kerk der Jesuiten te Antwerpen (1751)

(R. Dekoninck) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 277

Korte levensbeschryvingen van de heiligen der Societeit van Jesus (1761)

(F. Chanterie S.J.) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 280

Manuel Álvares S.J., Syntaxis (1776) (G. Tournoy) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 284

Abbreviations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 287

Index of Persons . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 288

Index of Printers . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 298

Index of Places . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 300

Contributors . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 305

207

Guy Tachard S.J., Reis na Siam (1687)

Reis na Siam, gedaan door den ridder de Chaumont, gezant van zyn allerchristelykste majesteit aan den koning van Siam. In ’t Fransch beschreeven door den vader Guy Tachard reisgenoot van den gemelden gezant; en uit die taal in ’t Nederduitsch gebracht door G. V. Broekhuizen. Vercierd met schoone kopere figuuren. t’Amsterdam: by Aart Dirksz. Oossaan, 1687. *-**, A-Pp4, Qq2, A-L4;

[16], 294, [14], 83, [5] p.: ill. // 4° [19,9 × 15].Provenance: several initials of names (ms); Sig. conv. Lokeren FF. Minorum; Conventus Lokerensis FF. MM. Recoll. (stamps); Bibliotheek Franciskanen Vaalbeek (bookplate). Binding: contemporary, calfskin, restored spine. Bound with: Verhaal van het gezantschap des ridders de Chaumont aan het hof des konings van Siam […], (t’ Amsterdam: Aart Dirksz. Oossaan 1687) and Drie seer aenmercklijcke reysen na een door veelerley gewesten in Oost Indien; gedaen van […] Frikius, […] Hesse […] Schweitzer vertaeld door S. de Vries, (Utrecht: Willem vande Water 1694). P910.4/Q°* TACH Reis

IN 1685, Jesuit Guy Tachard embarked upon his first journey to

Siam (present-day Thailand). That same year, in Europe, reli-

gious and political tensions reached another climax after Louis XIV

revoked the Edict of Nantes, making Protestantism illegal in France

and hence fuelling the conflict with the Dutch Republic under

William of Orange. Despite this war with France (and the conflict

with England), the world’s first private corporation, the Dutch East

India Company (Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie, or VOC),

was on the eve of its most lucrative period, setting the example for

similar companies in Britain and France. While the different actors

in Europe were competing for wealth and power, Europe was

reaching beyond its received boundaries. Also, in science, in 1687,

the same year this Dutch translation of Tachard’s travelogue was

printed in Amsterdam, Isaac Newton published his Principia Mathe matica, in which he outlined the law of gravity and the gen-

eral principles of modern physics.

Some twenty-five years before, Jan van Riebeeck had arrived at

Table Bay. He established the first buildings of what would later

become Cape Town. Indeed, despite the unfavourable navigational

circumstances of ‘the Cape of Storms’, this settlement was originally founded as a halfway station

that provided the ships of the Dutch East India Company and other European vessels with

water and fresh supplies on their long journey to Asia. This was probably the reason why Father

Tachard and his company spent some time in the Cape.

Soon, however, the employees of the Dutch East India Company would be joined by German

and Dutch settlers and by the first French and Belgian Huguenot refugees, fleeing persecution in

Europe, in the course of 1687. In this original settlement, Anthony Thomas wrote, “Dutch was

imposed as the official language in schools, in commerce, in churches and in the conduct of public

affairs. The only form of Christian worship and doctrine tolerated in the settlement was the

‘sombre and stern Calvinism of the seventeenth century, hostile to all new light, thoroughly

208

imbued with the spirit of the Hebrew records of the Old Testament, and with but little of the

Christian spirit of kindness and mercy taught in the New’ (F.F. Hilder).” In view of the above,

Hilder’s statement may sound ironical. Yet, it highlights the complex set of political rivalries,

economic competition, and religious tensions that, together with a spirit of discovery and the

excitement of exploration, make up the background against which to read Tachard’s travelogue.

The warm welcome bestowed upon the French Jesuits by Commander Simon van der Stel

(1639-1712, r. 1679-1699), founder of, among other places, Stellenbosch, and VOC Commis-

sioner Hendrik Adriaan van Rheede (1636-1691) apparently did surprise Tachard. They were

allowed to put up an observatory in a pavilion in the garden of the VOC, but, stealthily, equally

used this permission to hear the confessions of the Catholics present.

Guy Tachard was born in 1648 near Angoulême (France). A novice at the age of twenty, he was

ordained a priest in 1679 and was preparing the publication of a French-Latin dictionary when he

joined in 1685 a royal mission towards the Kingdom of Siam in the company of the French envoy

Alexandre, chevalier de Chaumont (1640-1710). The frontispiece (see p. 205) shows Chaumont

handing the official letter from Louis XIV to the King of Siam. Other travel companions were abbé

François-Timoléon de Choisy (1644-1724) and five Jesuit scientists, who had Peking as destina-

tion. He was to shuttle nine times between France and Asia. On the second trip in 1687, he took

fourteen Jesuit scientists with him to Siam, as requested by the Siamese King. Throughout this

period, he was at the service of both the French King and King Phra Narai, the Great (1656-1688),

who pursued a policy of openness towards the West, and had shown an interest in Christianity –

which would eventually turn against him. In 1689, Tachard was sent to Bengal, where he died in

1712. His heart, however, remained with the Siamese people.

The volume under review deals with his first trip. First published in French in 1686 (in-4°,

Paris: Arnould Seneuze and Daniel Horthemels) with smaller editions following, “suivant la copie de Paris imprimée,” in 1687 and 1688 (in-12°, 2 variants, Amsterdam: Pieter I Mortier), it was

translated into Dutch by Gotfried van Broekhuizen (fl. 1681-1708), author of a few books and

translator of mainly travel literature, and into

Italian (Milan 1693). In an eight-page long

Letter to the Reader, Van Broekhuizen

complains about serious mistakes made in

an earlier translation by Willem Calebius

(fl. 1684-1687), Reis van Siam. […] Gedaan door de vaders jesuieten (“Journey to Siam, […] by the Jesuits;” in-4°, Utrecht: Johannes

Ribbius, 1687).

Since the final destination of the other

Jesuits was China, the volume contains a

letter written by François de La Chaize, S.J.

(1624-1709), confessor of Louis XIV and

instrumental in obtaining the needed royal

permissions for the French Jesuit mathemati-

cians to leave their country, and for joining

Ferdinand Verbiest in Peking, who had

requested their help.

209

Reis na Siam was not the only written account of this overseas journey to Siam; one could also

read the account of Chaumont himself; the many editions of Abbé de Choisy’s Journal du voyage de Siam; the Mémoires of the count de Forbin, marine officer; those of Fr. Bénigne Vachet (Mis-

sions Étrangères); and, lastly, the notes of travel companion Joachim Bouvet, S.J., on which

Tachard relied heavily. Yet, Tachard’s descriptions of the stopovers in the Cape and in Batavia

(Indonesia) and the ceremonies at the royal court and the barge procession in Ayuttaya, the then

Thai capital, captured and fed the imagination of the Western world for centuries. Its engravings,

moreover, have proven to be very resourceful to historians, geographers, zoologists, and anthro-

pologists, dealing with Siam but equally with South Africa.

Tachard’s second trip would provide the content for a new book, Second voyage du père Tachard et des Jésuites (Paris: Daniel Horthemels, 1689), which equally saw three editions published.

Whichever trip is described, the Cape of Good Hope is always in the picture. This ‘pit stop’

in Africa which the Catholic missionary Tachard would visit four times, is the place where

we find him faced with a number of African groups, next to communities of Dutch and French

Protestant colonizers. In the following pages, we will delve deeper into Tachard’s observations at

the Cape.

All too often, colonization is represented as a struggle between two clearly bounded, homo-

genous groups such as, Europeans and Africans, ‘colonizer’ and ‘colonized’. Reality, however, was

far more complex. Just as the former were divided into several factions and actors, each with

their own agenda, motives, and interests, so were the latter. Also, the Khoisan-speaking popula-

tion of the Cape were subject to internal and external rivalries, political friction, and economic

competition. Like the Europeans at the Cape, the different Khoisan groups and clans Tachard

refers to (Namaqua, Sonqua, and Ubiqua), and individual actors, sometimes allied in the face of

210

a common rival, opponent or enemy, or on the basis of a shared worldview. On other occasions,

however, they competed with one another in order to further their own needs and interests. To

an important extent, colonialism was an ongoing process of negotiation and provocation, of

friction and cooperation, often across the divides of stereotypical representation. Of course, these

processes also included the threat and use of violence. For instance, the original inhabitants of

Table Bay, the coastal Khoi (the so-called Strandlooper), were exterminated in what could be

regarded as the first in a series of genocides that took place in southern Africa during the eigh-

teenth and nineteenth centuries.

During these initial years, however, race relations in the Cape were less stringent than they

would become from the second half of the eighteenth century onwards. Even though the Cape

settlement employed slaves, imported after 1658 from East Africa and from the Dutch colonies in

the East, free Malayans and Africans enjoyed full citizen’s rights. During these first three decades

of the Dutch settlement, marriage between European settlers or employees and the various other

groups in the Cape micro-society were rather common. In fact, Simon van der Stel happened to

be of mixed descent himself. Only in the course of the eighteenth century, the descendants of these

mixed marriages would be attributed a distinct ‘racial’ status in between ‘black’ and ‘white’.

Nevertheless, one can assume that these relatively relaxed relations and attitudes were inspired by

pragmatic motives rather than by ideology. However, they were about to change, mainly under the

influence of the shortage of land and labour, and because of the rise of industrial capitalism in

England, which resulted in an immigration of mostly underprivileged workers into the Cape.

Who were the Sonqua, Namaqua, Ubiqua, Gouriqua, Illasiqua or Gririqua, that Tachard men-

tions in his description of the Cape? Rather than to different peoples, these names refer to social

and political entities, sometimes clans, grouped around a leader or Kaptein, speaking a similar,

though different, Khoisan language (a group of languages,

the most typical characteristic of which is the use of clicks,

probably the reason why the early Dutch named them Hot-tentot). They herded cattle and sheep, hunted, and worked

on the farm. Trading livestock and hunting produce with

the Dutch, they also acted as middlemen between the latter

and the more distant groups in the interior. One of the

other economic activities they engaged in was raiding live-

stock to trade with the expanding Cape economy, a practice

that was encouraged because of the growing demand for

meat in the Cape economy. Also, because of the growing

overseas demand for ivory, ostrich feathers and skins, guns

would become increasingly important as a means of produc-

tion in the course of the eighteenth century. Except for guns

and ammunition, livestock and hunting produce was also

bartered for tobacco, clothes, alcohol, and horses.

At the time of Tachard’s passage in the Cape, these

Khoisan-speaking groups found themselves caught between

an expanding settler society in the West (and later, South)

and an equally rapid encroachment of Bantu-speaking pas-

toralists and agriculturalists in the North and East. Whereas

211

also the relationship with their Bantu-speaking neighbours could take on many forms (ranging

from cooperation to employment, serfdom, and hostility), some of the Khoisan groups ended up

deprived of their land and animals, sometimes resorting to holdups and violence to make

ends meet. They were referred to by the Dutch name Bossiesman or Bushmen, meaning ‘brigands’

or ‘bandits’. In the context of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century racism, these groups were

hunted down mercilessly. In the words of Robert Gordon: “I feel that it is important to make

social banditry respectable again, for all of the southern African people exposed to the colonial

onslaught, those labeled ‘Bushmen’ have the longest, most valiant, if costly, record of resistance

to colonialism.”

In the course of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, many Khoisan speakers lived in

the emerging settlements and farms in the Cape. As racial tensions grew, however, some decided

to migrate across the Orange River, to Namibia. These Oorlam, as they were called, were well-

organised, well-armed and often literate. They even brought their own missionaries. In southern

Namibia, they merged with the local Nama population. Organised into independent polities,

these mixed Nama-Oorlam groups dominated the political landscape in southern and central

Namibia for most of the nineteenth and early twentienth century. Eventually they clashed with

neighbouring pastoralists and with European adventurers an settlers over the monopoly of the

lucrative Cape livestock trade.

This particular copy of Reis na Siam is the first part of a composite volume additionally contain-

ing (1) the report of Chaumont about his mission to Siam, equally translated by Van Broekhuizen

and (2) a typical example of seventeenth-century travel literature. According to the provenance

marks, it has always belonged to one or another community of the Franciscan family in Flanders.

Steven Van Wolputte & Bernard Deprez

Lit.: Sommervogel VII, 1802-1805, esp. 1802/1; DHCJ 4 (2001): 3685-3686 (J. Dehergne); NNBW 4 (1918): 309

(Ruys); STCN (Tachard, van Broekhuizen); Voiage de Siam du pere Bouvet précédé d’une introduction avec une bio graphie et une bibliographie de son auteur par J.C. Gatty (Leiden: Brill, 1963), XIV-XXIII; R.J. Gordon, The Bushman Myth: The Making of a Namibian Underclass (Boulder/San Francisco/Oxford: Westview Press, 1992), 6; B. Lau, Namibia in Jonker Afrikaner’s Time (Windhoek: National Archives of Namibia, 1994 [1987]); Ronald S. Love, “Rituals of Maj-

esty: France, Siam, and Court Spectacle in Royal Image-building at Versailles in 1685 and 1686,” Canadian Journal of History 31 (1996): 171-198; N. Thomas, Colonialism’s Culture: Anthropology, Travel and Government: A Study in Black and White (Oxford: Polity Press, 1994); A. Thomas, Rhodes: The Race for Africa (Harare: African Publishing

Group, 1996), esp. 48, citing F.F. Hilder, “British South Africa and the Transvaal,” National Geographic Magazine, March 1900, 88; J.-B. Gewald, Herero Heroes: A Socio-political History of the Herero of Namibia 1890-1923 (Oxford:

James Currey, 1999); Florence Hsia, “Jesuits, Jupiter’s Satellites, and the Académie Royale des Sciences,” in The Jesuits: Cultures, Sciences, and the Arts, 1540-1773, ed. John W. O’Malley et al. (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1999),

1: 241-257; Michael Smithies and Luigi Bressan, Siam and the Vatican in the Seventeenth Century (Bangkok: River

Books, 2001); François-Xavier Fauvelle-Aymar, L’invention du Hottentot: Histoire du regard occidental sur les Khoisan (XVe-XIXe siècle) (Paris: Publications de la Sorbonne, 2002); Steven Van Wolputte and Gustaaf Verswijver, eds., At the Fringes of Modernity: People, Animals, Transitions, African Pastoralists Studies, 2 (Tervuren: Royal Museum for Cen-

tral Africa, 2004); Margarita Peña, “En nombre de San Francisco Javier: El viaje del padre Tachard y los jesuitas del

Reino de Siam,” in San Francisco Javier entre dos continentes, ed. Ignacio Arellano et al. (Frankfurt/Madrid: Vervuert-

Iberoamericana, 2007), 177-187; http://www.sjthailand.org/english/historythai1.htm (access 10.03.2009).