US-China Education Review 2015(1A)

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

5 -

download

0

Transcript of US-China Education Review 2015(1A)

US-China

Education Review

A

Volume 5, Number 1, January 2015 (Serial Number 44)

David Publishing Company

www.davidpublishing.com

PublishingDavid

Publication Information: US-China Education Review A (Earlier title: US-China Education Review, ISSN 1548-6613) is published monthly in hard copy (ISSN 2161-623X) by David Publishing Company located at 240 Nagle Avenue #15C, New York, NY 10034, USA. Aims and Scope: US-China Education Review A, a monthly professional academic journal, covers all sorts of education-practice researches on Higher Education, Higher Educational Management, Educational Psychology, Teacher Education, Curriculum and Teaching, Educational Technology, Educational Economics and Management, Educational Theory and Principle, Educational Policy and Administration, Sociology of Education, Educational Methodology, Comparative Education, Vocational and Technical Education, Special Education, Educational Philosophy, Elementary Education, Science Education, Lifelong Learning, Adult Education, Distance Education, Preschool Education, Primary Education, Secondary Education, Art Education, Rural Education, Environmental Education, Health Education, History of Education, Education and Culture, Education Law, Educational Evaluation and Assessment, Physical Education, Educational Consulting, Educational Training, Moral Education, Family Education, as well as other issues. Editorial Board Members: Asst. Prof. Dr. Güner Tural Associate Prof. Rosalinda Hernandez Prof. Aaron W. Hughey Prof. Alexandro Escudero Prof. Cameron Scott White Prof. Deonarain Brijlall Prof. Diane Schwartz Prof. Ghazi M. Ghaith Prof. Gil-Garcia, Ana Prof. Gordana Jovanovic Dolecek Prof. Grigorios Karafillis Prof. James L. Morrison Prof. Käthe Schneider Prof. Lihshing Leigh Wang Prof. Mercedes Ruiz Lozano Prof. Michael Eskay Prof. Okechukwu Sunday Abonyi Prof. Peter Hills Prof. Smirnov Eugeny Prof. Yea-Ling Tsao Manuscripts and correspondence are invited for publication. You can submit your papers via Web submission, or E-mail to [email protected] or [email protected]. Submission guidelines and Web submission system are available at http://www.davidpublishing.com. Editorial Office: 240 Nagle Avenue #15C, New York, NY 10034, USA Tel: 1-323-984-7526, 323-410-1082 Fax: 1-323-984-7374, 323-908-0457 E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] Copyright©2015 by David Publishing Company and individual contributors. All rights reserved. David Publishing Company holds the exclusive copyright of all the contents of this journal. In accordance with the international convention, no part of this journal may be reproduced or transmitted by any media or publishing organs (including various Websites) without the written permission of the copyright holder. Otherwise, any conduct would be considered as the violation of the copyright. The contents of this journal are available for any citation. However, all the citations should be clearly indicated with the title of this journal, serial number and the name of the author. Abstracted/Indexed in: Database of EBSCO, Massachusetts, USA Chinese Database of CEPS, Airiti Inc. & OCLC Chinese Scientific Journals Database, VIP Corporation, Chongqing,

P.R.C. Ulrich’s Periodicals Directory ASSIA Database and LLBA Database of ProQuest Excellent papers in ERIC Norwegian Social Science Data Service (NSD), Norway Universe Digital Library Sdn Bhd (UDLSB), Malaysia Summon Serials Solutions Polish Scholarly Bibliography (PBN) CNKI Google Scholar J-GATE Scribd Digital Library Airiti

Academic Key Electronic Journals Library (EZB) CiteFactor, USA SJournal Index Scientific Indexing Services New Jour Pubicon Science Sherpa Romeo Scholarsteer Turkish Education Index World Cat Infobase Index Free Libs Pubget CrossRef

Subscription Information: Price (per year): Print $600 Online $480 Print and Online $800 David Publishing Company 240 Nagle Avenue #15C, New York, NY 10034, USA Tel: 1-323-984-7526, 323-410-1082 Fax: 1-323-984-7374, 323-908-0457 E-mail: [email protected]

David Publishing Companywww.davidpublishing.com

DAVID PUBLISHING

D

US-China Education Review

A Volume 5, Number 1, January 2015 (Serial Number 44)

Contents Curriculum and Teaching

Constructing Choreography—A Transdisciplinary Challenge: Children’s Constructing

the Choreography of the “Dance of the Dinosaurs” 1

Ingrid Lindahl

The Influence of Web-based Intelligent Tutoring Systems on Academic Achievement and Permanence of Acquired Knowledge in Physics Education 15

Mustafa Erdemir, Şebnem Kandil İngeç

Design of an Arabic Spell Checker Font for Enhancing Writing Skills: A Self-learning Prototype Among Non-Arabic Speakers 26

Muhammad Sabri Sahrir

An Investigation About Misconceptions in Force and Motion in High School 38

Azita Seyed Fadaei, César Mora

Using Systems Thinking Strategy in an Environment Course 46

Li-Ting Cheng, Jeng-Fung Hung, Shiang-Yao Liu

Teacher Education

What Factors “Work” for Teacher Organizational Learning in Shanghai Middle Schools? A Grounded Theory Approach 52

Liu Sheng-nan, Feng Da-ming

Understanding Class Teaching Authority From a Feminism Perspective 67

Hu Bai-yun, Ma Cheng, Li Sen

US-China Education Review A, January 2015, Vol. 5, No. 1, 1-14 doi: 10.17265/2161-623X/2015.01.001

Constructing Choreography—A Transdisciplinary Challenge:

Children’s Constructing the Choreography of the

“Dance of the Dinosaurs”

Ingrid Lindahl

Kristianstad University, Kristianstad, Sweden

The aim of this study is to contribute to the understanding of the transdisciplinary exploration of children in

constructing the choreography of the “Dance of the Dinosaurs”, with mathematics being one of the disciplines used.

Central questions explored were: 1. What form did the children’s transdisciplinary exploration take? 2. What could

be learned about the mathematical understanding of the children? and 3. What problems emerged during the

process and how did the children respond to these? The study is an example of dialogical research, providing a

bridge between post-modern and modern theories and approaches. Deconstructive dialogue, imagination, and

rhizomatic thinking are central concepts in the theoretical framework. The empirical material consists of six-hour

video-taped material. The study found that the children explored and identified new problems, which they then

critically reflected and called in question. Time, space, shape, size, numbers, and patterns emerged in their

mathematical work. The children cooperated with each other during the problem-solving process and looked for

further challenges.

Keywords: transdisciplinary exploration, mathematical work, cooperation

Introduction

Recent educational steering documents have highlighted the mathematical ability of children and their way

of learning mathematics and using mathematics in different contexts (Swedish National Agency for Education,

1998). Today, there is much evidence suggesting that children do not explore the world by subject, but rather

create meaning through different “languages”—such as writing, reading, dancing, and movement—involving

all senses (Dahlberg & Moss, 2005; Lenz-Taguchi, 2010). The focus of this study is the transdisciplinary

cooperation between children, in which mathematics constitutes one of these “languages”. Kress (1997) refered

to the transdisciplinary exploration of children as “multi-modality”, which means that children apply a number

of different means of expression to communicate, and Deleuze and Guattari (1987) called it “rhizomatic

thinking”, i.e., learning and thinking where different disciplinary and verbal phenomena cooperate in a complex

and dynamic way.

This study aims to contribute to the understanding of the transdisciplinary exploration of children in

constructing the choreography of their own “Dance of the Dinosaurs”, where mathematics was one of the

disciplines used. The question posed was: What form did the transdisciplinary exploration of children take in

Ingrid Lindahl, Ph.D., senior lecturer, School of Education and Environment, Kristianstad University.

DAVID PUBLISHING

D

CONSTRUCTING CHOREOGRAPHY—A TRANSDISCIPLINARY CHALLENGE

2

the “Dance of the Dinosaurs”? Other questions were: 1. What could be grasped about the mathematical

understanding of children through studying their method of application? and 2. What problems emerged during

the process and how did the children respond to these?

Theoretical Framework

Dialogical Research—A Field of Tension Between Different Paradigms of Learning

The theoretical position of the study, which can be referred to as “dialogical research” (Alvesson & Deets,

2000), as applied to pedagogical investigation, was that the suppositions and theories of modernity, indicating a

difference between humans and the environment, subject and object, internal and external, and theoretical and

practical, are being avoided. “Dialogical research” also enables researchers to incorporate different theories,

including older ones. Hence, a possibility is to comment on parts of the cultural historical theories of Vygotskij

(1987; 1995), and concurrently turn to the post-modern and post-structural perspectives presented in Derrida

(1998; 2005), Levinas (2005), and Deleuze and Guattari (1987). Common to these perspectives is that they

question the dichotomies created between the individual and society, the internal and external, and the aesthetic

and the rational. Vygotskij (1987) chose to talk about dialectical relationships, while the post-modern theories

talk about complexity and multiplicity.

As in the post-modern perspective, Vygotskij (1987) showed how the created knowledge can never be a

reflection of factual circumstances. The conscious is dynamic and changeable and the process is dialectic in

constant movement between the internal and the external. This study turns to Vygotskij’s theory of “making

unfamiliar”, the role of the imagination in creating knowledge, and the theory of activity. At the same time, the

investigation is based on the post-modern and post-structural creation of theory according to Derrida’s theory

of deconstructive conversation (Derrida, 1998; 2005) and Deleuze’s concept of knowledge—“rhizomatic

thinking” (Deleuze & Guattari, 1987). In these perspectives, knowledge is not seen as something universal,

unchanged, and absolute. Consequently, teaching cannot be directed towards general ideals as this would make

the child into an object, as opposed to a subject in its own process of creating the subject and meaning. Rather,

the aim is for teachers to listen to children and try to identify their questions, theories, and hypotheses about the

surrounding world. These questions and theories then become the basis of teachers’ considerations on their own

attitudes and on how to meet and challenge the children in the exploratory process. How the process will end

and what course it will take, are open.

Making Unfamiliar, Deconstruction, and Ethics

Malaguzzi (1981) created the metaphor “A child has a hundred languages”, suggesting that children are

“fortunate”, worth listening to, taking seriously, and showing respect to. The acts of children and their

questions and problems they seek to solve become the focal point of teachers’ considerations. Using the

concept of “zone of proximal development” (here called “the development zone”), Vygotskij (1995) has shown

that children possess a rich potential for development. Play and exploration are described as activities that are

an integral part of the life of a child. A child’s actions are directed towards the goal of the activity and through

these goal-oriented actions, the child surpasses the current level of understanding and works within the

development zone.

Lindahl (2002) showed what happens when a teacher guides a child from the perspective of his/her own

goals but not those of the child: These conversations are called “reproductive” and are characterized by the

CONSTRUCTING CHOREOGRAPHY—A TRANSDISCIPLINARY CHALLENGE

3

child reproducing knowledge, instead of mainly producing something new of his/her own. The space allowed

for children’s own initiatives and “side issues” is restricted; children in this learning situation are stopped in

their own thinking and imitate each other in solving problems. To imitate each other’s solutions to problems is

regarded, in Reggio Emilia discourse, as one part of the exploration of children. In the context of exploration, it

is about testing the ideas of others to see if these can offer a different way of looking at a phenomenon (Rinaldi,

Giuchi, & Krechevsky, 2001). To Vygotskij (1987; 1995), imitation can also be a way for children to develop

an understanding of their own and create meaning. For example, children use the words of other people before

they comprehend the full significance of the words. Simultaneously, a dialectic process of interpretation starts

at the crossroads between the words of other people and the own thinking, significance, and meaning.

In reproductive conversation, imitation as matter of course emerges in a different way. To imitate each

other becomes a solution that children choose as an answer to the situation, created by the teacher, for example,

when they are constantly being interrupted in their own thinking and communication with their companions.

Thinking in a reproductive conversation loses its personal depth and the conversation ends up on the surface.

When a teacher fails to keep the goals of the children in focus, his/her guidance appears not to create

prerequisites for the children to operate in the development zone. The interpretation being made of the

development zone suggests that children have competence, thoughts, and ideas far beyond what can easily be

measured. Always, there is something “more” in the children, in the context, and in the presence, that cannot

see and certainly do not know anything about (Lindahl, 2002). This is an interpretation of the development

zone which can be compared to Malaguzzi’s (1981) metaphor of a child’s “hundred languages”, expressing a

strong humility towards the child and his/her inherent richness.

In shedding light on the role of art and the imagination in creating knowledge and meaning, Vygotskij

(1924/1971) turned to the Russian formalists and their conception of “making unfamiliar”. The rules of

everyday language are broken in poetry, which gives rise to “making unfamiliar”, as the poetry works in a

deautomatized way, according to the formalists. Thus, the evolution of literary history represents a constant

breach of ingrained conventions. When a new notion becomes convention, it loses its “unfamiliar making”

effect. This effect appears in the description by Vygotskij of how a child interprets his/her experiences and

creates something new, a meaning of its own through transforming exaggeration in a creative, narrative act.

The imagination, which Vygotskij termed the “combinatory ability” of the mind, plays a pivotal part in this act,

and is characterized by transformations, condensation, shrinkage, and exaggeration. If the role of the

imagination in the creation of knowledge is denied in teaching, understanding is put at risk of becoming barely

reproductive and not being as creatively productive, as Vygotskij considered desirable (Vygotskij, 1987;

Lindahl, 2002). This productive, creative, and variable way of regarding creation of knowledge and meaning,

described by Vygotskij (1987), has points of contact with the theory of Derrida (1998) concerning

deconstruction and deconstructive conversations. Deconstruction is often associated with text; however,

Derrida made it clear that deconstruction is equally about dialogical and living conversations. Deconstruction

as communication almost becomes a moment of non-understanding, of not knowing, insecurity, and somewhat

losing the self to the Other. Derrida endorsed the ethics of Levinas (2005) and his view of the Other and the

Other’s otherness to show how respect of the Other is basic in all communication. For example, one cannot

force his/her way of thinking and understanding of the world on the Other. Levinas emphasized that respect is

about the right to be different. It is through the presence of the Other that the subject is created. These ethics

could be regarded as implicitly present in all human relations, according to Levinas (2005). Prerequisites for an

CONSTRUCTING CHOREOGRAPHY—A TRANSDISCIPLINARY CHALLENGE

4

ethical meeting are openness towards the Other’s infinite otherness, a welcoming attitude, hospitality, and that

meeting the Other as an enigma.

Vygotskij’s (1924/1971; 1995) theory of “making unfamiliar” could be considered as having similarities

with the deconstruction theory of Derrida (1998). Vygotskij showed how the activity of the imagination is a

prerequisite for knowledge not to become reproductive but productive and creative, i.e., to lead to new

creations. Derrida (1998) spoke in a similar way about how a shift in meaning, a “difference”, occurs in the

reconsideration of given “assumptions”, and how it opens the way to something completely new or different.

“Differences” emerge in deconstructive conversations, also characterized by openness towards the otherness of

the Other. In this perspective, the view of the Other becomes central, as it will be decisive for whether the

conversation will lead to “differences” or merely allow recreation of already given “assumptions”. The

intention is not to agree in the sense of all thinking in the same way, but to enable differences to emerge, which

could create something new beyond ingrained conceptions of how things can be understood.

Rhizomatic Thinking—Escape Routes and Sidetracks

Philosophers Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari coined the metaphor “rhizome” or “rhizomatic thinking” to

stand for an image of thought and show how thinking emerges among people in tangled ramifications (Deleuze

& Guattari, 1987). “Rhizome” is a term derived from botany and refers to the stems of certain plants, which can

produce new shoots and root systems. These are often plants that are hard to root out, thanks to the rhizomatic

growth; that spread unpredictably in all directions. Instead of regarding the creation of knowledge as a linear

path, Deleuze and Guattari (1987) argued that the process can start at several points and move rhizomatically.

One follows new threads of roots to localize other nodes or clusters, pointing in other directions. In that way,

and through conceptual inventiveness rather than logic, an “escape route” can be created, an opening for the

flight of thought from what else limits creativity.

In studying children’s philosophical exploration of ethical dilemmas (Lindahl, 2010; 2011; 2013), it can

be noticed how children use the language creatively in describing grown-ups’ disinterest in playing with

smaller children, whom they described as “small as an earlobe”. The conversations between children and

teachers contained a playful element. For instance, making fun of things was important using known words as

well as creating new ones. “Sidetracking” could be perceived as taking winding “escape routes”. It provided

openness towards the unknown, which characterizes rhizomatic thought processes. In a Vygotskian perspective,

the “routes of escape” can be perceived as the imagination of children, including breaking boundaries, “making

unfamiliar”, and testing new perspectives.

Mathematics, Dance, and Transdisciplinary Exploration

Children and mathematics have previously been studied from a constructive perspective, in relation to

problem-solving. These studies focused largely on understanding of concepts, as well as on establishing what

environments create the best conditions for mathematical learning, such as ordering and grouping based on size,

form, and geometrical patterns (Clements & Sarana, 2007; Dienes, 1960; Reis, 2012). Further, the focus in

these studies was on the competence of children, competence development, and learning of mathematics. A

conclusion they all arrived at is that teachers should learn to discover how children use mathematics in their

play and other activities of their own choice, and take these insights as a starting point to challenge the further

use of mathematics. Reis (2012) suggested that the theory of variation (Marton & Tsui, 2004) could be used

together with the pedagogy of development (Pramling-Samuelsson & Asplund-Carlsson, 2003) in making

CONSTRUCTING CHOREOGRAPHY—A TRANSDISCIPLINARY CHALLENGE

5

development models for how the work with mathematical learning of children can be pursued.

Based on transdisciplinary thinking, Palmer (2010) showed how children learn mathematics through the

body, the room, objects, and impulses from medial discourses in a transdisciplinary learning process. The

language of dance, expressions, and materializing becomes productive in connection with the concepts and

material of mathematics. Here, the interest lies in the mere process. The research question evolves from “What

does this mean?” to “What happens after this?”. Learning occurs both between individuals and between people

and the context of the discourse of the environment. Time and place become agents, like concepts and ideas

(Barad, 2007; 2008). Also, it is impossible to draw any clear lines between different kinds of bodies, human or

non-human, the material, and the discourse. However, one danger with this approach may be that the role and

responsibility are diminished in space, material, social media, etc.. If the enquiry and interest of children will

remain in focus, all pedagogical choices must be based on an ethical position about the Other and the otherness

of the Other. In this study, transdisciplinary exploration is based on the notion that everything is connected to

everything. The understanding of a certain act or phenomenon cannot be reduced to one aspect and exclude

others within a complex context. However, in the context of the preschool or school, a teacher must be given a

special significance as being utmost responsible for the Other and the otherness of the Other to be allowed

space and be treated within the totality of the complex situation. Based on the preschool or school he/she is

working in, it is the teacher who creates the spatial, material, and dialogical prerequisites for transdisciplinary

exploration; it is the teacher who interprets what is important for these specific children here and now in this

situation.

Teachers’ ability to interpret the situation has been described, based on the concept of “situational

sensitivity” (Lindahl, 2010; 2011; 2013). This includes teachers’ trust in the own ability to interpret the

situation and critically reflect upon both the own acts and those of the children. There is an acceptance that

there is no “right way”, that you simply have to trust the situation and the outcome, and to try to feel secure

despite uncertainty. Situational sensitivity is not a mystical feeling; it just appears in certain people with a

special ability for interpretation. By contrast, developed situational sensitivity is based on reflected experiences,

which in turn demand knowledge and education, Bildung. This type of situational sensitivity creates images of

how responsible meetings can be made possible and “otherness” can be welcomed, and is based on a

philosophy about the child (the Other), values, the world, and Bildung in its discursive and emancipated sense.

Situational sensitivity makes many options possible, including the option of more easily following children in

their unpredictable exploring.

To sum up, the theoretical framework of this study is based on Vygotskij’s theory of making unfamiliar, a

process in which the imagination, the creative ability, and a productive view of knowledge are highlighted. The

theoretical framework is further based on Derrida (1998; 2005) and Levinas (2005) concerning the

understanding of deconstructive conversations, how children create something new in these, and how they

respect the otherness of Others, as discussed by Levinas. All pedagogy has an ethical starting point, based on

how the subjects regard the Other. The view that knowledge and learning are rhizomatic, resembling the

growths of a tangled root, as proposed by Deleuze and Guattari (1987), is also part of the framework.

According to this, transdisciplinary exploration can be regarded as a way children learn, where nobody knows

where the exploration is heading or where it originates from. This study tries to find points of contact with both

Vygotskij’s theory (1987; 1995) and post-modern and structural theories. The theoretical position of the study

could be referred to as the field of tension between modern and post-modern structural approaches.

CONSTRUCTING CHOREOGRAPHY—A TRANSDISCIPLINARY CHALLENGE

6

Method

Before the dance project was put in stage initiated, the children dramatized how they believed the

dinosaurs moved. They made drawings, wrote down observations, and built three-dimensional dinosaurs. In

conversations with the children in one of the smaller groups, the question arose regarding how dinosaurs moved

and, if they could dance, what music they would have liked. This made the teacher ask the children: If

dinosaurs could dance, what do you think it would look like? Could you do a dinosaur dance? Together, the

children chose music for the dinosaur dance from the Office of Multi-media. The initial group consisted of five

children, all of them were girls: Alva, Isabelle, Agnes, Annabelle, and Elvira. The question which was later to

occupy the children was: “Can we draw the movements of the dance?”. The problem, jointly formulated by the

children, was whether they would be able to draw the movements of the dance. The first step in

problem-solving was to create movements suitable for the chosen music, and the second, to shape the

movements of the dance on paper.

The children dancing the “Dance of the Dinosaurs” all attended a preschool class. Their interest in the

exploration of dinosaurs led to a dance project involving a few groups of three to four children per group. The

exploration of the children was discussed with the teacher. The children participate in different exploratory

projects at the school. The project here studied was titled “the dance project”.

The empirical work consists of digital film recordings, altogether six hours of film, and diary notes.

Totally, 26 children aged from six to seven came to participate in the project including dance and

choreography. The group of children who introduced the project and who participated in the study consists of

five girls aged six to seven. They are Alva, Isabelle, Agnes, Annabelle, and Elvira. Ethical issues were

taken into consideration according to the guidelines of the Swedish Research Council. This means that all

the participating children’s parents, including the children themselves, have given their permission to the

study.

The method of processing the object of inquiry and analysing the data from a theoretical framework point

of view resembles what Patton (1990) called “orientational qualitative inquiry”. The knowledge drawn from

this method of interpretation is put in perspective. In this regard, the method of analysis differs from the

deliberate marked unconditionality usually associated with hermeneutical attempts. A number of excerpts have

been chosen from the transcribed films to illustrate the exploratory process. After every sub-section, the events

and their significance from the point of view of the theoretical framework are commented. Different possible

ways of interpretation are pointed out with the purpose of “inviting” the reader to make different interpretations.

Finally, summary of findings is presented in the “Conclusion” part of this reseach.

Children’s Exploration—An Infinite Adventure

The work starts when the children are given different tools to help them, such as a roll of paper, a CD

player, and music of their own choice. They place the roll of paper, or the “map” as they call it, on the floor.

Gradually, as they determine what movement goes with the music, they draw symbols, describing the order the

movements come in and writing their respective number. The children test out different movements, and they

draw symbols on the communal piece of paper they call “map” (see Figure 1). This is repeated time after time;

they dance, show each other, everybody is trying together, and then they sit down to draw. The process is

described below.

CONSTRUCTING CHOREOGRAPHY—A TRANSDISCIPLINARY CHALLENGE

7

Figure 1. The communal “map”.

Alva and Isabelle (turn around and say simultaneously): One, two, and three. (Then, they sit on the floor and continue to draw. Isabelle raises her hands and shows what they will do, and how to

do it.) Annabelle: Slap. Annabelle and Elvira (stand up and jump as they simultaneously say): One, two, jump, jump, one two, jump, jump.

We will do this twice, check it out. Elvira: How many times? Alva: One, two, three, eh... two, three, one jump, jump. We will do it twice, here.

One movement is followed by a number and then again by another number indicating the number of times

it will be performed. Movement one will be repeated twice, movement two six times, and so on.

Annabelle: How do you make a 9? (Elvira takes her own pencil and shows her. In the margin, Elvira writes her own 9.) Elvira: Like this. Let me show you! Annabelle: Is not that a “P”? Agnes (turns to Annabelle): If it is going to be a 9, should it be like this? (Agnes writes a new 9. Annabelle traces Agnes’ 9 with her pencil and then writes a 9 of her own.)

Children imitate and support each other, solving problems that come up. The teacher remains in the

background, but is present in the exploration of the children. When she sees Annabelle having a problem in

writing the number 9, she could have chosen to step in to “help” and show how it is done, or start explaining to

Annabelle. However, she chooses to wait and see what will happen in the group when Annabelle expresses her

problem. This could be regarded as an expression of “situational sensitivity”. It shows that she trusts the

children in the group, who apparently give Annabelle what she asks for and needs.

Dealing With a New Problem

But a new problem emerges in the group: The dance ends before the music is over.

Isabelle: But the music lasts longer than our dance? (A big discussion starts during which everyone talks simultaneously. They cannot match time with the movement.) Alva: Oh, it lasts a long time, and we danced so well. It was because we danced so fast. We have to do more because

the music lasts longer. What can we do?

CONSTRUCTING CHOREOGRAPHY—A TRANSDISCIPLINARY CHALLENGE

8

Annabelle: But if we do like this, twice, instead of once, like this, see, like this. One, two, three, slow. You know, like this ... one, two, three.

(The children think it over. They test a few more advanced moves and some gymnastic moves.) Alva: Then we have to draw more movements, to make the dance last longer. Up and down, up and down, it is from

the side. We need one (movement) between the eighth and the ninth (movement). Annabelle: Twelve, it will be the last one, so it has to be number 13. Alva: This, yes, that we should use at the end.

Alva shows with her body and draws a picture to illustrate a split (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Alva’s demonstration and drawing of the split.

The drawing is followed by a digit, for the number of the movement, and yet another digit for the number

of times the movement will be executed. The children get up and jump.

That the dance ends sooner than the music is a hard problem to solve, different suggestions are put

forward and discussed. Eventually, the group decides to include more movements to match the length of the

dance with that of the music. The children show with their whole bodies how the movement will be seen, and

this may be regarded as a “perception of space”—position and direction.

Alva: Up and down, up and down. It is from the side. We need one (movement) between the eighth and the ninth. No, it should be the last, so it must be number 13. This one, Annabelle is choosing, it should be number 12, we will have it at the end.

Annabelle: One foot forwards, one foot backwards, one foot to the side, one, two (jumps twice).

To find a solution to the problem, the children test different movements and rhythms simultaneously. They

are demonstrating and talking at the same time, but also listening to each other’s suggestions. After some

discussion, the children decide to create more movements, to be put after movement number 12. Thus, they

connect time with movement, which is noted as a form of “perception of time”.

From Common Ground to the Personal/Communal

From having made a drawing jointly, the children each want to create their own private “map”, or

schematic drawing, of the dance from movement 1 to movement 13 (see Figure 3).

Annabelle (points to her map): It looks like a Nintendo. (Elvira draws her map in three parts. She places the parts in order, beginning with number 6 instead of 1 (see Figure 4).) Annabelle (regarding it): But I wonder, look, 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 comes in the middle, it becomes another dance (giggles

twice).

CONSTRUCTING CHOREOGRAPHY—A TRANSDISCIPLINARY CHALLENGE

9

Elvira (also laughs, and then she realizes her mistake and corrects it): Oops, it became a little wrong.

Figure 3. Part of Annabelle’s “map”, or schematic drawing of the dance.

Figure 4. Elvira’s schematic drawing in three parts.

CONSTRUCTING CHOREOGRAPHY—A TRANSDISCIPLINARY CHALLENGE

10

The exploration of the children also includes size and form. They create a pattern when they jump, while

at the same time showing awareness of the number of jumps: “How many times? One, two, three, two, three,

one, two, jump, jump. One, two, jump, jump. We must do it twice”. The children record their movements,

reducing them, while sometimes they create symmetry in the movements. Figure 5 shows a symmetrical

movement in the shape of a heart, drawn by Annabelle.

Annabelle: We shall start small and then grow and get bigger and bigger. (At the same time, Annabelle and Elvira both suggest that movement number five will grow (increase in size) and be

executed six times.) Alva: What shall we have? Can we use what Annabelle and Elvira said? Elvira: Yes, alright. That will be fine. Like… Annabelle: Look here, grow bigger and bigger, it lasts for four beats laps. (The teacher nods, smiles, and looks at Annabelle and the other children.)

The exploration of the children therefore appears to include beat and tempo. The number of each

individual movement, and their form and the number that each is performed are put on paper in order. Elvira is

the first to decide to draw the movements from left to right. The children use symbols, formal as well as

informal, to represent the movements of the dance. Informal symbols are constructed to represent different

movements communally in the group.

Figure 5. Symmetrical movement in the shape of a heart.

There exists an allowing climate in the group, with the children listening to each other and giving each

other space. One possible explanation could be that the common goal, the end they want to achieve, is very

important to them, shaping their behaviour. They turn towards each other and often ask their friends what they

think should be done to achieve that goal: “What shall we have? Cannot we do what Annabelle and Elvira

said?”. They all seem to enjoy the common exploration. They listen to each other, participate, and each

contributes to the common project to create a dinosaur dance. The children appear to “own” the question.

But Why Should It Be a Dinosaur Dance of All Things?

In later conversations with the children, the children said that the dance project has been fun and that they

have learned a lot about dance and making maps. One question arises, however:

Elvira: But why does it have to be a dinosaur dance of all things? Dinosaurs would not have applauded over their heads. The movements are not like dinosaurs make.

CONSTRUCTING CHOREOGRAPHY—A TRANSDISCIPLINARY CHALLENGE

11

Sofie (teacher): Would you like to do a new dance? Elvira: Yes, but not about dinosaurs, not a song like that. We should have a song where they sing from YouTube.

Like Lady Gaga. Sofie: Would a map help you, then? Alva: Yes, but we would make it more carefully. Sofie: Mmmm, more carefully, what do you mean? Alva: Well, not like a draft, a map lengthwise.

The question remains. Why is it a dinosaur dance? Why not a dance for something other than dinosaurs?

In thinking back on their project, the children have almost abandoned all thoughts about dinosaurs. At the

forefront is the dance, the music, and the making of a “map”. All five children answered that they would use a

“map” again, but that next time they would design the map horizontally, i.e., with the paper in landscape

orientation.

The concept of a map was suggested by Elvira early on in the process. The making of the “map” became a

tool for the children’s choreography of the dance. It became a tool of communication and problem-solving,

formulated by the children, in their effort to draw the movements.

When planning their second dance project, not about dinosaurs, but with the dance itself in focus, the

group draws a combined map first, as a “draft”. Then, everybody wants to make his/her own. The children feel

that they cooperate well, but have problems in agreeing. When they eventually do agree, they have found a

movement that is so good that everyone is really satisfied.

Annabelle: It was hard to find dance steps that everybody wants to have. In the end, when we managed something good, everybody liked it.

Elvira: We learned to make maps of the dance, so we did not have to remember everything in our heads. Alva: It was hard to find a good song, this was not so good. … Elvira taught us to do a split, though I still cannot do

it. Elvira: I have practised since I was three. Annabelle: We learned how to move quickly, though we already knew it. Elvira: We learned how to dance to the beat of the music. Sofie: Mmmm (nods and looks at the children).

When the children talk about what they have learned, they mainly talk about what they have used in the

learning process. They also talk about the body, as they have explored the possibilities and boundaries of the

body.

A “Contagious” Interest

The interest in the dance is “contagious” both within and outside the class of children. It is this interest that

the researcher now continues to work on, looking for new questions, and so on. An interesting question is

whether the children use the experiences from the dinosaur dance in the process of designing a new dance. The

investigation shows that the children use the “map” as a natural tool in creating new dances. Those children

who were involved in the first project have been able to contribute their learning and experience to the

communal learning process. The other children in the class turn to them as experts.

Different groups differ in the amount of time they need for getting started. One group has run into great

difficulties and has really had a “struggle” in dividing the work-up among their members. Spending a lot of

time early on in the process helped them to get started in the long run. One member of the group said, when the

process was finally flowing, “Now dance for me, so I can draw”. In this group, the roles became very obvious:

CONSTRUCTING CHOREOGRAPHY—A TRANSDISCIPLINARY CHALLENGE

12

One member asked questions, wrote down, organized, and structured the group dance on paper, while another

took responsibility for the music and the third created new dance steps.

One discovery was the emphasis the groups put on working closely together. For some children, it seemed

very important to visit other groups from time to time to see the work of others. Maybe was it to get inspiration,

impulses, and new ideas. When the dance steps ended, a teacher got the children to ask other groups questions,

and they usually turned to one of the “experts” from the original dance project.

Conclusion

Describing complicated processes and doing them justice is an almost impossible task. What happened

when the children encountered problems, discovered new materials, and met with other people is so much more

complex than can be recorded linguistically and observed from certain theoretical perspectives. This project,

which still continues in new configurations and with new variants, should be regarded as an attempt to show

something of the complexity in the transdisciplinary exploration of children. Even if the children themselves

constitute the “engine” in the process, there is a teacher present (in this study, Sofie) who offers the children

access to an allowing surrounding and exploratory tools, such as tape-recorders, paper, and drawing materials.

However, the teacher needs to take an entirely different position from a teacher in a reproductive conversation

(Lindahl, 2002). In a learning environment as described in the present study, the teacher identifies the goals of

the children and supports them in reaching these goals. Thus, from a Vygotskian perspective (Vygotskij, 1987),

the teacher acts within a zone of development. Also, characteristically, the teacher shows situational sensitivity,

for example, as she chooses to act when the children run into problems with the length of the music and the

number of movements they have drawn. She is ever present in the “doing” of the children, which is detectable

in her body language, for example, when she says “Mmm”, smiles, and so on.

In the present investigation, the children have expressed the wish to create more projects, such as the

dinosaur dance project. The dance project is “contagious” to the other groups in the school and from time to

time, the children in the first dance project take on the role of mentors to the new dance groups. Here,

transdisciplinary exploration emerges between the common and the concrete goal of the children, i.e., to create

a dance with a map of the dance. This is no longer an entirely unprejudiced exploration where nobody knows

how it will end. However, nobody knows anything about what will happen along the way in the process of

exploration and solving problems. Regarded from a Vygotskian perspective (Vygotskij, 1987), the children

realize and reach the goals of their activity, namely, to create a dinosaur dance where movement, timing, and

the beat are held together and rendered understandable by their choreography. The children act in the proximal

zone of development and create learning. To some extent, the exploration of dance, made by the children, can

be regarded as the tangled root system of “rhizomes” growing into different directions and shaped by what has

arisen between them. This is a completely different process to step-by-step, linear learning.

What could be learned about the mathematical comprehension of children through their method of

application? The language, expression, and putting on of dance moves rely on mathematical concepts and

symbols. The children learn something about mathematics through the body, reflection, and the combining

ability of the imagination. Every movement takes its time, must be adapted to the beat, and represents a special

image. Every new movement is a new experience, something new to explore with the body and in dialogue

with each other. The children engage in deconstruction and create a difference, something new.

CONSTRUCTING CHOREOGRAPHY—A TRANSDISCIPLINARY CHALLENGE

13

Beats and tempi are explored, and new movements and rhythms are created and tested. The order, form,

and number of the movements become visible on paper. One child was uncertain of how to write the number 9,

but learned from another child, who showed her and explained to her, whereupon she tried over and over again

until she got it right. Symbols, both formal and informal, emerged in the map making. Informal symbols

emerged, constituting an “unfamiliar making” process through the changes and exaggerations of the children.

Description of position, direction, and sequence was a constant part of the process.

When encountering a problem, for example, when the music lasts longer than the movements for

their dance, the children are prepared to listen to proposals from others, which is basic for both an ethical and

a deconstructive conversation. They now connect time with movement, which could be regarded as a

perception of time. The map of the dance, being both the tool and the goal of the children, consists of numbered

symbols for the dance steps, and has emerged in combination with time, beat, and melody music. It may be

seen to resemble a tangled root system consisting of different thread-like roots to hold on to and further

pursue. “But why a dinosaur dance of all things?” is a question the children have posed in conversation with

the teacher. One possible answer is that the attention of the children has been revolving around the concrete

problems and the goal they have wanted to achieve. However, the children express eagerness to design

another dance, which they will do by creating a new, more precise dance map. The children already have the

experience of creating a dance map, which experience and learning they can contribute to making a new dance.

As with every learning situation, there will be new challenges and new problems that will need to be solved.

The dance will continue, but there will be new events, new challenges, and new explorations: an infinite

adventure.

References Alvesson, M., & Deets, S. (2000). Kritisk samhällsvetenskaplig metod (Critical methodology of social science). Lund, Sweden:

Studentlitteratur. Barad, K. (2007). Meeting the universe halfway: Quantum physics and the entanglement of matter and meaning. Durham: Duke

University Press. Barad, K. (2008). Posthumanist performativity: Toward an understanding of how matter comes to matter. In S. Alaimo, & S.

Hekman (Eds.), Material feminisms (pp. 120-154). Bloomington, I.N.: Indiana University Press. Clements, D. H., & Sarana, J. (2007). Early childhood mathematics learning. In F. K. Lester (Ed.), Second handbook of research

on mathematics teaching and learning (Vol. 1, pp. 461-556). Charlotte, N.C.: Information Age. Dahlberg, G., & Moss, P. (2005). Ethics and politics in early childhood education. London, U.K.: Routledge/Falmer. Deleuze, G., & Guattari, F. (1987). A thousand plateaus: Capitalism and schizophrenia. (B. Masumi, Trans.). Minneapolis, M.S.:

University of Minnesota Press. Derrida, J. (1998). Of grammatology. Baltimore, M.D.: John Hopkins University Press. Derrida, J. (2005). Rouges: Two essays on reason. Stanford, C.A.: Stanford University Press. Dienes, Z. P. (1960). Building up mathematics. London, U.K.: Hutchington Educational. Kress, G. (1997). Before writing: Rethinking the paths to literacy. London, U.K.: Routledge. Lenz-Taguchi, H. (2010). Rethinking pedagogical practices in early childhood education: A multidimensional approach to

learning and inclusion. In Y. N. Maidenhead (Ed.), Contemporary perspectives on early childhood education. Maidenhead, U.K.: Open University Press.

Levinas, E. (2005). Totality and infinity: An essay on exteriority. Pittsburg, P.A.: Duquesne University Press. Lindahl, I. (2002). Att lära i mötet mellan estetik och rationalitet—Pedagogers vägledning och barns problemlösning genom bild

och form (Learning encountering aesthetics and rationality—Teacher’s guidiance and children’s problemsolving through art and form). Malmö, Sweden: Högskolan i Malmö.

Lindahl, I. (2010, September 6-8). Wondering together—Children’s philosophizing upon ethical issues. Paper presented at The European Early Childhood Education Association (EECEA) Conference, Birmingham, UK.

CONSTRUCTING CHOREOGRAPHY—A TRANSDISCIPLINARY CHALLENGE

14

Lindahl, I. (2011). Sharing values and doing democracy—Children, educators, companies in collaboration for sustainable development—a narrative study. In CICE Lifelong Learning and Citizenship. London: Institute for Policy Studies in Education, London Metropolitan University.

Lindahl, I. (2013). Interacting with the child in preschool—A crossroad in early childhood education. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal (accepted for publication).

Malaguzzi, L. (1981). Intervju med Loris Malaguzzi av Karin Wallin. I. K. Wallin, mfl. Ett barn har hundra språk. Om den skapande pedagogiken på de kommunala daghemmen i Reggio Emilia Italien (Interview with Loris Malaguzzi by Karin Wallin in I. K. A child has got hundred languages. About the creative pedagogy in the daycare centers in Reggio Emilia) Stockholm, Sweden: Sveriges Utbildningsradio AB.

Marton, F., & Tsui, A. B. (2004). Classroom discourse and the space of learning. Mahwah, N.J.: Erlbaum. Palmer, A. (2010). “Let’s dance”: Theorizing feminist and aesthetic mathematical learning practice. Contemporary Issues in Early

Childhood, 11(2), 130-143. Patton, M. Q. (1990). Qualitative evaluation and research methods. London, U.K.: Sage. Pramling-Samuelsson, I., & Asplund-Carlsson, S. (2003). Det lekande lärande barnet i en utvecklingspedagogisk teori (The

playing and learning child in a pedagogical development theory). Stockholm, Sweden: Liber. Reis, M. (2012). Att ordna från ordning till ordning: Yngre förskolebarns matematiserande (From ordering to ordering: Preschool

children’s mathematisation). Göteborg, Sweden: Acta Universitatis Gothoburgensis. Rinaldi, C., Giuchi, C., & Krechevsky, M. (Eds.). (2001). Project zero: Making learning visible: Children as individual and

group learners. Reggio Emilia, Italy: Tipolografia la Reggiana. Swedish National Agency for Education. (1998). Läroplan för föskolan (Curriculum for preschool). Stockholm, Sweden:

Skolverket & CE Fritzes Förlag. Vygotskij, L. S. (1924/1971). The psychology of art. Cambridge, M.A.: MIT. Vygotskij, L. S. (1987). Thought and word. In R. Rieberg, & A. S. Carton (Eds.), The collection of works of L. S. Vygotskij (Vol. 1

Problems of general psychology, including the Volume 1. Thinking and speech). New York, N.Y.: Plenum Press. Vygotskij, L. S. (1995). Fantasi och kreativitet i barndomen (Imagination and creativity in childhood). Göteborg, Sweden:

Daidalos.

US-China Education Review A, January 2015, Vol. 5, No. 1, 15-25 doi: 10.17265/2161-623X/2015.01.002

The Influence of Web-based Intelligent Tutoring Systems on

Academic Achievement and Permanence of Acquired

Knowledge in Physics Education*

Mustafa Erdemir

Kastamonu University, Kastamonu, Turkey

Şebnem Kandil İngeç

Gazi University, Ankara, Turkey

This study aims to determine the influence of distance asynchronous teaching of Physics-I topics via intelligent

tutoring systems (ITSs) on academic achievement and permanence. A Web-based learning environment was

created by use of an ITS called “Turkish Intelligent Tutoring System” (TURKZOS) for such Physics-I units as

work, energy, and conservation of energy. The experimental group of the study consisted of 26 students who had

computer and Internet access and participated in the study voluntarily. The achievement test developed by the

researchers was used for collecting data. This test was conducted as pre-test and post-test before and after the

experimental procedure respectively. The same test was administered to measure permanence 45 days later

following the performance of the post-test. The obtained data were analyzed via paired t-test. Mean pre-test score

was found to be 23.88, and mean post-test score was found to be 73.80. Mean permanence test, on the

other hand, was found to be 71.88. When mean pre-test and post-test scores were compared, a significant

difference was identified in favor of the mean post-test score (p < 0.05). In addition, a significant difference was

detected between mean permanence test and pre-test scores (p < 0.005). The mean permanence test score was

higher than the mean pre-test score. It was concluded that intelligent learning environments created through

Web-based tutoring systems have a positive influence on academic achievement and permanence in physics

teaching.

Keywords: physics education, distance education, Web-based intelligent tutoring system (ITS), academic

achievement and permanence

Introduction

Lifelong learning has become one of the primary goals of education. Education has always been a main

issue since the start of humanity. Studies and research on learning and teaching existed in the past, exist now,

and will continue to exist in the future. Educational experts carry out studies and research in order to adapt

developments in science and technology to learning and teaching situations. Attempts are made to introduce

technological developments to teaching.

Education continues until death to improve both individual and social life quality. Continuous learning

* This paper is presented at The 2nd International Instructional Technologies & Teacher Education Symposium (ITTES2014, 20-22 May 2014, Afyonkarahisar-Turkey).

Mustafa Erdemir, M.A., lecturer, Faculty of Education, Kastamonu University. Şebnem Kandil İngeç, Ph.D., associate professor, Faculty of Education, Gazi University.

DAVID PUBLISHING

D

THE INFLUENCE OF WEB-BASED INTELLIGENT TUTORING SYSTEMS

16

brings about a democratic improvement in economic growth, social welfare, and life (Derrick, 2003). Since

learning cannot be achieved in the classroom environment at every age, it sometimes takes place from distance,

through technology use and via interactions with the environment. Furthermore, institutions and organizations

turn to distance education in order to inform and train their target groups. Distance education refers to a

synchronous or asynchronous learning process involving the use of such teaching tools as technological

instruments, written materials, and printed materials when students and information source are at a physical

distance.

Distance education utilizes various techniques, such as virtual classroom, e-learning, m-learning,

Web-based distance education, online learning, and blended education. The improvement of these techniques

and the increase of their productivity in educational processes depend on technological developments. For

example, advancements in artificial neural networks have enabled more efficient use of computers in

educational activities and have contributed to the creation of intelligent tutoring systems (ITSs). Among

primary educational technologies are communication technologies, computer technologies, and artificial neural

network programmes. Today, studies on education mainly focus on these subjects. In this context, two

important fields of study are improving the productivity of computer-supported education and integrating

computer programmes, like ITSs into educational processes.

Developments in artificial neural networks have led to the birth of intelligent learning environments, and

the combination of these environments with computer-supported education has brought about ITSs. Being new

learning environments, ITSs allow the individualization of learning processes, the elimination of time and space

obligations, and the systematic access of many people to educational activities. This makes the use of ITSs in

education widespread. Moreover, ITSs are the programmes involving processes that are most similar to the

behaviors displayed by teachers in teaching processes. ITSs, which refer to an advanced educational approach,

offer lesson content to every student through adaptation and imitating teachers. ITSs perceive every student’s

knowledge level and decide on the next teaching situation to make them reach the maximum level as normal

(regular) education does (Jerinic, 2013).

According to Doğan (2006), ITSs are regarded as future’s teaching systems, and thus, many studies are

carried out in this field. Intelligent teaching systems are the teaching systems that are most similar to the

traditional classroom environment. ITSs are quite successful in comparison to other systems (Doğan & Kubat,

2008).

ITSs can adapt to the individual needs of students and the acts of teachers. They aim to achieve teachers’

acts. ITSs can provide students with flexible teaching materials, a one-to-one teaching environment, and

feedback (Moundridou & Virvou, 2000).

There are some question marks regarding how sensibly information provided in the virtual environment is

received and treated by individuals. According to Gustafsson (2002), students cannot complete their learning

processes through distance education, which uses technological teaching techniques, and it is difficult to inspect

students in this approach. In formal education, social communication among students encourages the

continuance of educational activities.

Socialization, group work, and face-to-face interaction in formal education improve achievement and

continuity. However, the importance of learning processes based on distance ITSs is undeniable, too.

Technological education must create awareness within the context of social content and influence.

Educators need to be prepared for this change. Thus, information environments should be created rapidly.

THE INFLUENCE OF WEB-BASED INTELLIGENT TUTORING SYSTEMS

17

ITSs aim to imitate normal (regular) teachers by adapting to individuals’ (students’) strengths, weaknesses,

and other characteristics. As students use ITSs, their deficiencies are noticed. Such deficiencies may be

overcome by use of different teaching strategies. This brings a big convenience to teachers and students by

providing them with a flexibility to eliminate these deficiencies.

The Web-based ITS used in the present study offers a time and space independent asynchronous learning

process, which provides those people who cannot receive formal education with an educational opportunity. In

addition, it can be used for supporting in-class training. Students employ processes unique to themselves in

learning something new or recalling a piece of knowledge acquired beforehand, but such individuality is not

taken into consideration enough in the classroom environment.

Web-based ITSs provide students with an educational opportunity that is both time and space independent

and free from any problems caused by the Internet environment (İstanbul, 2003). Today, education and

technology are intertwined. Although there are already some common educational approaches (e.g.,

behaviorism, cognitivism, and constructivism), a new theory has been introduced by Siemens (2006) as a

learning theory for the digital age: the Connectivism Theory. This theory emphasizes that knowledge is in the

external word; it is consumed very fast; the process of reaching it continues for life time; developing digital

technology is required for reaching it; and for all these reasons, there is a need for such a theory.

Achievement and Permanence

Curricula and teaching and assessment processes of educational institutions focus on students’

achievement. However, students at the same age may have different learning processes and perceptional states.

Some students may learn very rapidly, while some others learn or reach learning tools very slowly. To improve

achievement and permanence, non-common states (characteristics) of students must be taken into consideration

when preparing and implementing curricula and teaching and assessment processes. It is quite difficult to use

learning environments that are made up of non-common states in normal (regular) education. In

classroom-oriented education, lesson contents and learning processes are created by assuming that a general

perception level prevails among students. In normal (regular) classrooms, learning environments cannot be

created based on non-common states (e.g., time, space, individual perception, and the number of students), and

learning can be achieved only through adaptable teaching states, which decrease overall achievement. This has

a negative influence on permanence because it is related to the continuity of achievement.

Teaching lessons via adaptive Web-based ITSs may provide advantages about time, space, individual

perception, the number of students reached, creation of a rich content, and navigational support. These

advantages may eliminate problems emerging in the classroom, allow offering individualized lesson contents,

and enhance overall achievement.

The use of technology in educational activities is undeniable. One of the primary tools used in education is

computer. It is reported that computer-supported education has a considerable influence on student achievement

because teachers use computers as an auxiliary tool to concretize abstract concepts (Güven & Sülün, 2012).

Time and space independence is one of the most important benefits of Web-based education, which is

considered to have a positive influence on enhanced performance (Demirel, Seferoğlu, & Yağcı, 2001).

ITSs

ITSs are a class of computer-based education systems that allow adaptivity at a certain level. As students

THE INFLUENCE OF WEB-BASED INTELLIGENT TUTORING SYSTEMS

18

use these systems, teaching strategies are changed and adapted depending on students’ progress. Such systems

identify the strengths and weaknesses of students, and teachers continue teaching activities in the classroom

environment based on such identification, which allows doing necessary updates in these systems (Doğan,

2006).

ITSs allow shaping learning processes according to individuals’ needs, affective characteristics, like

learning style, and cognitive knowledge levels (Dağ, 2011). ITSs consist of several components for design and

conceptualization purposes.

According to Woolf (1992), ITSs are composed of the following four basic components:

(a) The student module;

(b) The tutoring module;

(c) The domain (expert knowledge) module;

(d) The user interface (communication) module.

The Student Module

It stores the information unique to each student. It monitors how well students do in learning situations.

The objective of this module is to collect information for the tutoring module and to make the expert use such

information.

While some student modules contain short-term information (i.e., valid for one session), some others make

use of long-term information. Short-term information is used for instant assistance. Long-term information, on

the other hand, can be used for selecting the best problem or topic appropriate to the student in pedagogical

actions (Suraweara, 2004).

Short-term student module. Model monitoring module and constraint-based student module are

examples of this module.

Long-term student module. Overlay student module, stereotypes tudent module, Bayes student module,

case-based student module, and agent-based student module are examples of this module. The short-term

student module is usually used for updating the long-term student module (Mayo, 2001).

The Overlay Student Module Used in the Study

It involves differences between the expert’s knowledge of the topic and the student’s knowledge of it. The

student’s domain knowledge is considered a subset of the expert’s knowledge (Stankov, 1996).

The objective of this module is to eliminate deficiencies or wrong knowledge of students and to make

them reach the expert’s knowledge. It is not approved that students have the knowledge that is not possessed by

the expert. The domain knowledge is divided into sections, such as rules, events, and concepts. The degrees to

what these sections are known are expressed by ranges. For instance, when the range “0” to “100” is used, “0”

demonstrates lack of knowledge, while “100” indicates that the topic is known perfectly. The beginning level of

a student is considered “0”, and his/her level changes dynamically depending on his/her behaviors (Suraweara,

2004).

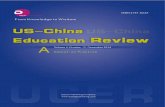

ITS General Algorithm Used in the Study

The Web-based ITS used in the study was developed by Karacı (2013). Figure 1 presents the algorithm of

the ITS used in the study. After students study all the topics and pages in the related unit at the learning level

determined by the teacher and calculated via artificial neural networks, they can enter the exam page. The

learning levels of students entering the exam page are calculated based on the assessment method determined

THE INFLUENCE OF WEB-BASED INTELLIGENT TUTORING SYSTEMS

19

by the teacher. If the calculated learning levels are equal to or higher than the level determined by the teacher,

students are directed to the unit or units meeting the requirement for moving up. If the learning level is not

enough, the pages in which students have problems are given to students as feedback, and students are

requested to study such pages again. If students want to take the exam again without studying these pages, they

are not allowed to do so. The above-mentioned procedures are conducted and repeated until students learn all

units at the learning level determined by the teacher (Karacı, 2013).

Figure 1. General algorithm of the ITS used.

All units arefinished?

Level of Learning at the desired

level?

Directed to the appropriate unit

Begin

Introduction to System

Does the unit havebeen left

incomplete?

Directed to the appropriate unit

Check the session information

Learning level, store-level student learning

Y

NH

Y

Level of Learning at the desired

level?

Y

NY Finish.

N

Students entering this the first

A preliminary test

N

YE

Work unit

N

Implementation E

Is the desired level has been studied in the

Y

H

The lack Detection

1

1

THE INFLUENCE OF WEB-BASED INTELLIGENT TUTORING SYSTEMS

20

According to this algorithm, if a student enters for the first time, the first topic titles are opened. If the

student entered and studied some topics beforehand, the system directs him/her to the page he/she left off.

Those students who enter for the first time study the content including figures, formulas, animations, examples,

activities, and lectures prepared by the teacher as well as the links about the related topic and answer the

questions on activity pages. Students finishing a topic proceed to another topic. The same study method is

employed for each topic in the unit. After students study all of the topics in the unit, they take the end-of-unit

exam for moving up. To take this exam, students need to study each content page for a time determined by the

teacher. If a student has not studied content pages enough, he/she is directed by the system to relevant pages.

The Intelligence Features Used in the Study

The intelligence features used in the study are explained below.

Remembering the page left off. If a student leaves the page or closes the browser directly, the system

directs him/her to the last page visited when he/she enters the system again. When he/she enters the system,

he/she continues with the last page displayed.

Stating learning levels. The system reports a student’s learning level to him/her (he/she definitely does

not know; he/she most probably does not know; he/she possibly does not know; he/she may know; he/she

possibly knows; he/she most probably knows; he/she definitely knows; etc.).

Determining the topics in which individuals have deficiencies and directing them to such topics. The

system determines the concepts, topics, and pages in which students have deficiencies, directs them to such

concepts, topics, and pages, and makes suggestions.

Detecting reviewing situations and directing. When a student does not review the pages which the

system recommends him/her to do so, it detects it, prevents the student from proceeding to a new page, and

directs him/her to pages in which he/she has learning deficiencies.

Ensuring proper proceeding to new topics. When a student does not satisfy the learning level

determined by the teacher as a condition for proceeding, the system prevents him/her from proceeding to the

themes established by the teacher.

Opening topics to those who satisfy the conditions for proceeding. When a student satisfies the learning

level determined by the teacher as a condition for proceeding, the system brings the themes to which the student

can proceed into use and directs him/her by informing him/her of the themes to which he/she may proceed.

Monitoring the answers given. The system allows monitoring the answers given by students to

end-of-topic exam questions.

Monitoring students in the learning process. The system prevents students from proceeding to another

page before monitoring a page, hides activity answers, monitors the number of entrances of students and

duration of remaining on pages, and determines the pages that are monitored, that are allowed to be monitored,

and that are not allowed to be monitored.

Page monitoring level. The system determines the page monitoring levels (page study levels) of students

as “Good”, “Moderate”, and “Bad” and prevents those students who have not reached the requested level from

proceeding (The page monitoring level is calculated based on the number of entrances by students in pages and

duration of remaining there).

Navigation. The system determines the pages which can be entered by students and directs them to such

pages. It also provides navigational adaptation.

THE INFLUENCE OF WEB-BASED INTELLIGENT TUTORING SYSTEMS

21

The Teaching Method Employed in the Study

The teaching method of the Web-based ITS used in the present study was implemented in the

experimental process. This teaching method is programmed instruction, which refers to ordered or programmed

arrangement of learning tools and materials to make students reach the related behavioral goals (Çağıltay &

Göktas, 2013).

The principles which the programmed instruction is built upon are presented below.

Principle of small step. Topics are presented to a student through division into sub-topics. Topics are

from simple to complex. The student proceeds to the work performed by the varying force after he/she

completes the work performed by the constant force. The student has to achieve the passing grade in the

end-of-unit exam determined by the teacher in order to proceed to a new unit. If this condition is not satisfied,

the system does not allow the student to proceed to a new unit.

Principle of active responding. The Web-based ITS is a learning system based on the interaction

between students and computer. Thus, there is a continuous interaction between the system and students. The

system monitors students, addresses questions to check whether or not knowledge has been acquired, and

ensures active responding by enabling students to answer such questions. It also contributes to active

responding by giving instant feedback to the answers of students.

Principle of immediate confirmation. Immediate feedback (i.e., true or false and in red color) is given to

students in regard to results. The Web-based ITS immediately reports as feedback whether the responses of

students to activities and end-of-unit questions are true or false. The teacher can see such responses and

feedback, too.

Principle of self-pacing. The Web-based ITS used in the study is an adaptive system and does not bring

any limitation to students in the learning process. They may reach the lesson content whenever and wherever

they want. This allows students who use the system to receive a free and individualized education.

Principle of correct answers. Whether or not the answers given by the students using the Web-based ITS

are true is immediately reported to them as feedback. Students can re-answer by reviewing what they have done

or the topics they have covered. If they cannot reach correct answers, they may obtain information by sending

the teacher an e-mail or using social communication tools. Furthermore, the teacher sees the pages studied by

his/her students as well as their responses to the activities. The teacher writes suggestions and comments as

feedback so that students can find the correct answers.

The intelligence features of the system used in the study overlap with the programmed instruction.

Although printed materials are used in the programmed instruction, instructional design theory is widely used

in the computer environment. According to Jonassen (1996), computer-based teaching is a practice developed

based on the programmed instruction.

Method

Scope

The present study involves the pre-tests, post-tests, and permanence tests of 26 students from the

Mathematics Teaching Program, Department of Primary Education, Faculty of Education, Kastamonu

University, who learned such Physics-I units as work, energy, and conservation of energy via a Web-based

ITS.

THE INFLUENCE OF WEB-BASED INTELLIGENT TUTORING SYSTEMS

22

Limitation

The study is limited to the pre-tests, post-tests, and permanence tests of 26 students using a Web-based

ITS.

Significance

ITSs are regarded as future’s teaching systems. It is considered that examining the influence of a

Web-based ITS developed for contributing to physics education and making it effective, productive, and

interesting may contribute to the related literature.

Study Group

The study group consists of 26 students from the Mathematics Teaching Program, Department of Primary

Education, Faculty of Education, Kastamonu University, who are receiving the Physics-I course in the

2012-2013 academic year.

Research Model

“One-way repeated measures test”, which is a semi-experimental design, was employed in the study. After

the students’ knowledge of the lesson content was measured via the achievement test, which was developed by

the researchers as a pre-test before the experimental procedure, the students were informed about the adaptive

ITS named “Turkish Intelligent Tutoring System” (TURSOZ) developed by Karacı (2013). Then, they used the

system online for four weeks. The achievement test was administered to the students as a post-test after the

experimental procedure. The same test was conducted as a permanence test 45 days later following the

administration of the post-test.

Data Collection Tool

The academic achievement test was developed on such Physics-I topics as work, energy, and conservation

of energy. The achievement test comprising of 25 questions was administered to 35 students who had received

the above-mentioned course before. Six questions that were found to have low reliability in item analysis were

removed. Thus, the achievement test consists of 19 questions including concept and problem questions. The

achievement test was administered as a pre-test, as a post-test, and as a permanence test to measure the

knowledge levels of the students in the beginning, to determine the increase in their knowledge through the

experimental procedure, and to see the permanence of such knowledge.

Data Analysis

The data obtained through the experimental procedure were analyzed via the one-way repeated measures

test. Repeated measures are carried out to determine the difference between a categorical variable that has

minimum three sub-dimensions and continuous variables (Pallant, 2011). The dependent variable of this study

is a continuous variable. It is the progress scores of the pre-service primary school mathematics teachers