US-China Foreign Language Volume 12, Number 3, March 2014 (Serial Number 126)

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

0 -

download

0

Transcript of US-China Foreign Language Volume 12, Number 3, March 2014 (Serial Number 126)

US-China

Foreign Language

Volume 12, Number 3, March 2014 (Serial Number 126)

David Publishing Company

www.davidpublishing.com

PublishingDavid

Publication Information: US-China Foreign Language is published monthly in hard copy (ISSN 1539-8080) and online (ISSN 1935-9667) by David Publishing Company located at 240 Nagle Avenue #15C, New York, NY 10034, USA.

Aims and Scope: US-China Foreign Language, a monthly professional academic journal, covers all sorts of researches on literature criticism, translation research, linguistic research, English teaching and other latest findings and achievements from experts and foreign language scholars all over the world.

Editorial Board Members: Yingqin Liu, USA Charmaine Kaimikaua, USA Annikki Koskensalo, Finland Jose Manuel Oro Cabanas, Spain Tamar Makharoblidze, Georgia Cecilia B. Ikeguchi, Japan Delia Lungu, Romania LOH Ka Yee Elizabeth, Hong Kong, China Shih Chung-ling, Taiwan Balarabe Zulyadaini, Nigeria Irina F. Oukhvanova, Belarus

Ivanka Todorova Mavrodieva Georgieva, Bulgaria Ali Nasser Harb Mansouri, Oman Anjali Pandey, Zimbabwe LEE Siu Lun, Hong Kong, China Sholpan K. Zharkynbekova, Kazakhstan Fawwaz Mohammad Al-Rashed Al-Abed Al-Haq, Jordan Shree Deepa, India Nektaria Palaiologou, Greece Lilit Georg Brutian, Armenia Elena Maryanovskaya, Russia

Manuscripts and correspondence are invited for publication. You can submit your papers via Web Submission, or E-mail to [email protected]. Submission guidelines and Web Submission system are available at http://www.davidpublishing.org, www.davidpublishing.com.

Editorial Office: 240 Nagle Avenue #15C, New York, NY 10034, USA Tel: 1-323-984-7526, 323-410-1082 Fax: 1-323-984-7374, 323-908-0457 E-mail: [email protected], [email protected]

Copyright©2014 by David Publishing Company and individual contributors. All rights reserved. David Publishing Company holds the exclusive copyright of all the contents of this journal. In accordance with the international convention, no part of this journal may be reproduced or transmitted by any media or publishing organs (including various websites) without the written permission of the copyright holder. Otherwise, any conduct would be considered as the violation of the copyright. The contents of this journal are available for any citation, however, all the citations should be clearly indicated with the title of this journal, serial number and the name of the author.

Abstracted/Indexed in: Database of EBSCO, Massachusetts, USA ProQuest Research Library, UK OCLC (Online Computer Library Center,Inc.), USA LLBA database of CSA (Cambridge Scientific Abstracts), USA Ulrich’s Periodicals Directory Chinese Database of CEPS, Airiti Inc., Taiwan Chinese Scientific Journals Database, VIP Corporation, Chongqing, P.R.C. Summon Serials Solutions Google Scholar J-Gate

Subscription Information: Price (per year): Print $520 Online $300 Print and Online $560

David Publishing Company 240 Nagle Avenue #15C, New York, NY 10034, USA Tel: 1-323-984-7526, 323-410-1082. Fax: 1-323-984-7374, 323-908-0457 E-mail: [email protected] Digital Cooperative Company: www.bookan.com.cn

David Publishing Companywww.davidpublishing.com

DAVID PUBLISHING

D

US-China Foreign Language

Volume 12, Number 3, March 2014 (Serial Number 126)

Contents Linguistic Research

A Contrastive Analysis of the Verb Phrase in English and Ɛŋgwo: Some Pedagogical Implications 177

Paul Mbufong, Fontem A. Neba, Abianji Emmanuel

Interpreting Semitic Protolanguage as a Conlag or Constructed Language I 183 Edouard G. Belaga

Teaching Theory & Practice

Teaching Effect of Contrasting Intonation Systems 193 Hanako Hosaka

On the Development of Novice English Teachers’ Practical Knowledge—A Case Study of Two Novices in Nanchong No. 1 Middle School in China 204

DENG Xiaofang, FENG Dan, YING Bin, CHEN Qian

Speed Reading: Theory, Practice, and Research 216 Binnan Gao

Translation Research

The Emotive Component in English-Russian Translation of Specialized Texts 226 Natalia Sigareva

Cultural Differences and C-E Advertising Translation 232 HU Chun-xiao

Literary Criticism & Appreciation

The Cutting Edge Between Nationalistic Commitment (Iltizām) and Literary Compulsion (Ilzām) in Palestinian “War” Literature 239

Dima M. T. Tahboub

US-China Foreign Language, ISSN 1539-8080 March 2014, Vol. 12, No. 3, 177-182

A Contrastive Analysis of the Verb Phrase in English and Ɛŋgwo:

Some Pedagogical Implications

Paul Mbufong University of Douala,

Douala, Cameroon

Fontem A. Neba University of Buea,

Buea, Cameroon

Abianji Emmanuel Government High School Ekona,

Ekona, Cameroon

This study sets out to perform a contrastive analysis of the verb phrase in English and Ɛŋgwo. This is because it is

suspected that the differences between the components of the verb phrase in both languages may account for some

of the errors that native speakers of Ɛŋgwo learning English as a second language commit. Special attention was to

verb phrase components and their placement in verb phrase structure. Sample verb phrases were collected from

recorded speeches, interviews, observations, and the researchers’ knowledge of both languages. The data were then

analyzed. The results of the research suggest that the components of the verb phrase in both languages pose few

problems but their placement in verb phrase structure and the modifications they undergo account for many of the

numerous errors that native speakers of Ɛŋgwo make when learning English as a second language.

Keywords: contrastive analysis, verb phrase, pedagogy

Introduction

The desire to learn English either as a second or foreign language is increasing in Cameroon. Cameroon is a country where English is learned as a second language by English speaking Cameroonians (Anglophones) and as a foreign language by French speaking Cameroonians (Francophones). The language is given a high coefficient in class and certificate examinations. It is also given a high premium in professional examinations.

There is an increasing effort made by learners to avoid errors in the target language. Despite these efforts, their utterances in the target language are not error free. The errors are numerous and varied. A study of these errors reveals that many of them result from the negative transfer of features from the learner’s mother tongue to the target language while others result from the learner’s attempt to reproduce the rules of the target language he or she has formulated or memorized.

Contrastive analysis, a term coined by Lado (1957), seeks to establish the similarities and differences between languages with the assumption that the areas of similarities will be easier to study in a target language while differences will pose learning difficulties (Bouton, 1970; Gradman, 1971; James, 1976, 1980).

This research seeks to perform a contrastive analysis of the verb phrase in English and Ɛŋgwo. It intends to

Paul Mbufong, lecturer, Department of English and Foreign Languages, University of Douala. Fontem A. Neba, lecturer, Department of English, University of Buea. Abianji Emmanuel, lecturer, Department of English, Government High School Ekona.

DAVID PUBLISHING

D

A CONTRASTIVE ANALYSIS OF THE VERB PHRASE IN ENGLISH AND ƐŊGWO

178

compare and contrast verb phrases in both languages, and to attempt to establish the areas which might pose problems to learners of English as a second language with Ɛŋgwo as a first language.

Ɛŋgwo is the native language spoken by the Ngwo people found in Njikwa Sub-Division in the Northwest Region of Cameroon. It is one of the 279 native languages spoken in Cameroon (Tanda, 2006).

Ɛŋgwo has co-existed with English for a long time. Ɛŋgwo also makes use of English words that have been borrowed and adjusted phonologically (see Example (1)).

Example (1) Pen εpεn Ball bɔrɔ Towel tawεt

The relationship between both languages can be felt even in the educational milieu. Ngwo students who are in the same school, at the same level of education and who are taught in school using English

often revise or discuss their school subjects among themselves in Ɛŋgwo though they will have to write the subjects in English.

It is for this reason that the present research seeks to find out if the similarities and differences between the verb phrase components in both languages can account for the numerous errors involving the verb phrase that

native Ɛŋgwo speakers make in learning English as a second language. The study is very necessary when one looks at the fact that very little has been written about Ɛŋgwo (Ntembe,

1987; Abianji, 1999).

Materials and Method

The main method of data collection is a form similar in nature to the Grammar Translation Method that was propounded by Johann Seidenstucker, Karl Plotz, H. S. Ollendorf, and John Meidinger in that “it approaches the language first through detailed analysis of its grammar rules followed by application of this knowledge to the task of translating sentences and texts into and out of the target language” (as cited in Richards & Rodgers, 1995).

This research is therefore based on a series of verb phrases that have been given in Ɛŋgwo, and then, translated into English and vice versa.

Because no previous attempt has been made to classify the components of the verb phrase in Ɛŋgwo, the components have thus been classified following the English classification. The components in Ɛŋgwo are therefore based on the English components to see how they can be realized in Ɛŋgwo. The other components in Ɛŋgwo that do not exist in English have also been considered. Data were then collected in both languages, placed side by side and contrasted.

Contrastive Analysis and Discussion of Results

This involves comparing and contrasting verb phrases in English and Ɛŋgwo and predicting the errors that are likely to occur.

Verb Phrases Containing Modal Verbs This involves verb phrases that make use of English modals such as may, might, can, could, will, would,

shall, etc. (see Example (2)).

A CONTRASTIVE ANALYSIS OF THE VERB PHRASE IN ENGLISH AND ƐŊGWO

179

Example (2a) He may eat He might eat εŋgo wunε ndε He can eat He would eat

Example (2b) They may eat They might eat aŋgo bənε ndε They can eat They would eat

Example (2c) I will sing a song εmε waŋgo kwon εtsa They will sing a song aŋgo baŋgo kwon εtsa

Example (2d) She could dance εŋgo anεnε bin They could dance aŋgo anεnε bin

Of the auxiliaries in English, may, might, would, will, and shall express the possibility of the action of the verb taking place now or in the future. Could is used to show the possibility of the action of the verb in the past. As can be seen from the data above, Ɛŋgwo has only two forms which can be used for may, might, can, and would which are wunε (see Example (2a)) if the subject is singular and bənε (see Example (2b)) if the subject is plural. Equally, will vary depending on whether the subject with which it is used is singular or plural. If the subject is singular, waŋgo (see Example (2c)) is used, and if the subject is plural, baŋgo (see Example (2c)) is used. Unlike the other auxiliaries that vary when used with singular or plural subjects, could remains the same anεnε (see Example (2d)) whether it is used in the singular or in the plural.

From the above data, one can predict that there may be semantic errors resulting from the misuse of modals since there are more modals in English than in Ɛŋgwo. The native Ɛŋgwo speakers may not be able to know the difference between the following sentences since they mean the same thing in Ɛŋgwo (see Example (3)).

Example (3) They look at me They may look at me aŋgo bənε kεdε aŋgu They might look at me They would look at me

Verb Phrases Containing Finite Verbs/Tenses The finite form of a verb is used to show agreement with the subject and to show agreement with the subject

and to indicate tense. It is the most widely used form of the verb. Example (4) English Ɛŋgwo

Write ŋwεʔrε I am writing English εmε wa ŋwεʔrε εkara (*1I am write English) We are writing English mbiə ba ŋwεʔrε εkara (*we are write English) She writes English εŋgo wa ŋwεʔrε εkara (*she is write English) They write English aŋgo ba ŋwεʔrε εkara (*they are write English) I ate rice εmε aa ndε aliʃi (*I [past tense marker] eat rice)

1 The star indicates that the structure is ungrammatical in standard English.

A CONTRASTIVE ANALYSIS OF THE VERB PHRASE IN ENGLISH AND ƐŊGWO

180

We ate rice mbiə aa ndε aliʃi (*we [past tense marker] eat rice) We will speak to him mbiə ba gama bo aŋgo (we will speak [pl] to him) I will speak to him εmε wa ga bo ŋgo (I will speak [sg] to him)

The sentences in Example (4) involve verb phrases that contain finite verbs/tenses in English and Ɛŋgwo. They have been carefully selected to show the various aspects of the verb phrase in both languages. When a verb is used in the infinitive in English, there is no problem to realize it in Ɛŋgwo. Problems arise when the verb is conjugated. This is because tenses are realized in Ɛŋgwo through the use of auxiliary verbs which most often vary depending on whether the subjects with which they are used are singular or plural. In the present continuous tense, we see that “is” in Ɛŋgwo is realized as “wa” and “are” is realized as “ba” and the verb that comes after any of them is not conjugated as seen in the cases of “wa ŋwεʔrε—is writing” and “ba ŋwεʔrε—are writing”.

With regards to the simple present tense in English, the verb is inflected for tense by the addition of an “s” to the verb if the subject is singular except when “I” is used as the subject. No “s” is added if the subject is singular. In Ɛŋgwo, this tense is realized in the same way like the present continuous tense as seen in Example (5).

Example (5) English Ɛŋgwo She writes εŋo wa ŋwεʔrε They write aŋgo ba ŋwεʔrε

Some verbs are inflected in Ɛŋgwo but this is for plurality as seen in the examples involving speak (see Example (6)).

Example (6) We will speak mbiə ba gama (gama = speak [plural]) I will speak εmε wa ga (ga = speak [singular])

We see here that if the subject is singular “I”, “ga = speak” which is not inflected for plurality is used. If the subject is plural “we”, “gama = speak” which is inflected for plurality id used. In the case of “ate” where the verb is conjugated in the past tense, the tense is realized through the position of “aa” (a tense marker) in front of the verb, and then, a verb in the infinitive.

From the data, it can be predicted that native Ɛŋgwo speakers may tend to use an auxiliary followed by a verb in the infinitive, since it is a structure common in their language, there by producing asyntactic English sentences as shown in Example (7):

Example (7) They have eat aŋgo ʃi ndε (ʃi ndε = have eat) She has go εŋgo ʃi ŋgo (ʃi ŋgo = has go)

They may tend to add the tense marker “s” or “es” to a verb thinking they are inflecting the verb for plurality since some verbs are inflected in Ɛŋgwo for plurality as in Example (8):

Example (8) They have gone aŋgo ʃi ŋgoro (ʃi ŋgoro = have goes) *They goes She has gone εŋgo ʃi ŋgo (ʃi ŋgo = has go) *She has go

Reduplication of Verbs Verbs in Ɛŋgwo are most often reduplicated. Almost all verbs in Ɛŋgwo can be reduplicated. The effect of

reduplication will depend on the intension of the speaker and what the hearer makes of the situation. This process is done for different reasons. It can be for encouragement, or to minimize the stress involved in the execution of the action of the verb. It can be for emphasis or to communicate the effect of the English “just”. Reduplication is

A CONTRASTIVE ANALYSIS OF THE VERB PHRASE IN ENGLISH AND ƐŊGWO

181

at times used to show the type of terrain one is moving on. Verbs may be reduplicated more than twice but this is most often to show that the action of the verb took place over a long period of time.

Example (9) dɔrɔ dɔrɔ ŋgo *run run go kwɔrɔ kwɔrɔ atsa fiε *sing sing two songs (just sing two songs) ga ga εna *speak speak to me (just speak to me) dara dara ŋgo (to walk on level land) kwaʔ kwaʔ zε *climb climb come (climb and come) εmε a ga ga ga *I spoke spoke spoke

The sentences in Example (9) have been used to show the reduplication of verbs. The verbs “dara dara” and “kwaʔ kwaʔ” are used to show the type of terrain on which one is moving but “dara dara” has not got an English equivalent as “walk” cannot sufficiently describe it. Together with the other verbs they are reduplicated to achieve any of the other reasons already stated.

Borrowed Auxiliaries Auxiliary verbs have been borrowed from English to Ɛŋgwo to be used in expressions needing auxiliaries

that Ɛŋgwo has no auxiliaries for. The main auxiliary that has been borrowed from English is must which is pronounced in Ɛŋgwo [mʌʃi]. “Get” is a verb that has been borrowed from English but is used as an auxiliary verb in Ɛŋgwo to stand for either “has to” or “have to” as seen in Example (10):

Example (10) You must eat ngwo wa mʌʃi ndε (*You have to must eat) Joe has to go dzo wu gεrε ŋgo (*Joe is get to go) They have to come aŋgo bu gεrε zεʔ (*They have get to come)

From the above data, it can be predicted that “must” will pose no problem to the learners since it is borrowed with its meaning in English, but “get” will pose a problem as the learners may tend to use it as an auxiliary, thereby producing asyntactic sentences as shown in Example (11):

Example (11) Ɛŋgwo equivalent Correct English form *You get to do the work ŋgwo wu gεrε fwεʔ a fwεʔ jεə You have to do the work *You get to do the assignment ŋgwo wu gεrε lε gʌment wεə You have to do the assignment

Conclusions: Pedagogical Implications

The above study focused on the differences that exist between the components of the verb phrase in English and Ɛŋgwo to predict the errors that are likely to be committed by a native Ɛŋgwo speaker learning English as a second language. Using sample verb phrases containing modal auxiliaries, finite verbs, and borrowed auxiliaries from English to Ɛŋgwo and reduplication of verbs in Ɛŋgwo, the study was able to relate the verb phrases to the likely errors that a native Ɛŋgwo speaker will commit when learning English as a second language. It is worth noting here that these are only predictions that are likely to occur. Some or all may occur with different learners. None of the errors may even be found with some of the learners since language study differs from learner to learner.

A teacher of English to these Ɛŋgwo native speakers should be expected to meet some of these errors and so should be better prepared to overcome them. Contrastive analysis can be used to predict the hierarchy of difficulty in learning English as a second language to a native Ɛŋgwo speaker. This will go a long way to help structure the English language lesson, beginning with the areas of similarities to the areas of differences. Even the

A CONTRASTIVE ANALYSIS OF THE VERB PHRASE IN ENGLISH AND ƐŊGWO

182

difficult areas can be structured from the less difficult to the most difficult to facilitate learning by the learners. These and other suggestions could help to reduce the learners’ difficulties.

References Abianji, E. (1999). The noun phrase: A contrastive study between Ngwo and English (Unpublished dissertation for D.I.P.E.S. II.

University of Yaounde 1, E.N.S. Yaounde). Bouton, L. F. (1970). The problem of equivalence in contrastive analysis. IRAL, 14(2), 143-163. Gradman, H. (1971). The limitations of CA predictions (PCCLLU papers, University of Hawaï). James, C. (1976). The exculpation of contrastive linguistics. In G. Nicke (Ed.), Papers in contrastive linguistics (pp. 53-68).

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. James, C. (1980). Contrastive analysis. London: Longman. Lado, R. (1957). Linguistics across cultures. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. Ntembe, P. (1987). Borrowing into the Ngwo language (Unpublished dissertation for the undergraduate diploma, University of

Yaounde 1, E.N.S. Annex Bambili). Richards, C., & Rodgers, S. (1995). Approaches and methods in language teaching: A descriptive analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press. Tanda, V. (2006). Sociolinguistic aspects of language loss: A case study of the language situation of Cameroon. In E. N. Chia, K. I.

Tala, & V. A. Tanda (Eds.), Perspectives on language study and literature in Cameroon. Limbe: ANUCAM.

US-China Foreign Language, ISSN 1539-8080 March 2014, Vol. 12, No. 3, 183-192

Interpreting Semitic Protolanguage as a

Conlag or Constructed Language I

Edouard G. Belaga Université de Strasbourg, Strasbourg, France

One of the most natural approaches to the problem of origins of natural languages is the study of hidden intelligent

“communications” emanating from their historical forms. Semitic languages history is especially meaningful in this

sense. One discovers, in particular, that BH (Biblical Hebrew), the best preserved fossil of the Semitic

protolanguage, is primarily a verbal language, with an average verse of the Hebrew Bible containing no less than

three verbs and with the biggest part of its vocabulary representing morphological derivations from verbal roots,

almost entirely triliteral—the feature BH shares with all Semitic and a few other Afro-Asiatic languages. For

classical linguists, more than hundred years ago, it was surprising to discover that verbal system of BH is, as we say

today, optimal from the Information Theory’s point of view and that its formal topological morphology is

semantically meaningful. These and other basic features of BH reflect, in our opinion, the original design of the

Semitic protolanguage and suggest the indispensability of IIH—Inspirational Intelligence Hypothesis, our main

topic—for the understanding of origins of natural languages. Our project is of vertical nature with respect to the

time, in difference with the vastly dominating today horizontal linguistic approaches.

Keywords: Semitic languages, protolanguage, verbal system, origins of natural languages, artificial intelligence,

conlagor constructed language, VBBH (Verbal Body of Biblical Hebrew), IIH (Inspirational Intelligence

Hypothesis)

Language is one of the hallmarks of the human species—an important part of what makes us human. Yet, despite a staggering growth in our scientific knowledge about the origin of life, the universe and (almost) everything else that we have seen fit to ponder, we know comparatively little about how our unique ability for language originated and evolved into the complex linguistic systems we use today. Why might this be?

Morten H. Christiansen & Simon Kirby, 2003, p. 300

Introduction: BH (Biblical Hebrew) Perceived by Classical Linguists

Triconsonantal Morphological Pervasiveness of BH BH, the best preserved fossil of the Semitic protolanguage (Huehnergard, 2011), could be seen as

primarily a verbal language (Bergen, 1994), with an average verse of the Hebrew Bible containing no less than three verbs and with the biggest part of its vocabulary representing morphological derivations from verbal roots (Joosten, 2012), almost entirely triliteral, or triconsonantal (Gesenius, 1813, 1952)—the feature BH shares with all Semitic and a few other Afro-Asiatic languages (Ehret, 1995).

The unique peculiarity of this triconsonantal morphological pervasiveness did not completely escape the

Edouard G. Belaga, doctor, Institut de Recherche Mathématique Avancée, Université de Strasbourg.

DAVID PUBLISHING

D

INTERPRETING SEMITIC PROTOLANGUAGE AS A CONLAG

184

attention of previous generations of Western linguists, as shows the following “methodological” warning opening a popular Hebrew grammar edited more than a century ago:

Hebrew, of course, has difficulties of its own, which must be frankly faced. … [In particular,] the roots are almost entirely triliteral, with the result that, at first, the verbs at any rate all look painfully alike—e.g., malak, zakar, lamad, harag, etc.—thus imposing upon the memory a seemingly intolerable strain. Compound verbs are impossible: there is nothing in Hebrew to correspond to the great and agreeable variety presented by Latin, Greek, or German in such verbs as exire, inire, abire, redire, … ausgehen, eingehen, aufgehen, untergehen, etc. Every verb has to be learned separately; the verbs to go out, to go up, to go down are all dissyllables of the type illustrated above, having nothing in common with one another and being quite unrelated to the verb to go. (Davidson, 1916, pp. 1-2)

Three Extraordinary Fundamental Linguistic Phenomena This amusing résumé has the merit to recognize, even if under the guise of an earnestly banal pedagogical

clueing in, three extraordinary fundamental linguistic phenomena common to all Semitic languages: First, the extreme parsimoniousness, one could say optimality, from the point of view of Information

Theory, of the triconsonantal representation of verbs: With more than one and less than 2,000 known BH verbs, two consonants would be not enough and four would be too much: The BH dictionary has about 1,700 verbs among about 8,000 words.

Second, the meaningful morphological topology of the body of BH verbs, a fundamental feature of the BH architecture. Two triconsonantal verbs are morphologically or, equivalently, topologically neighboring if they differ in just one consonant, with many pairs of topological neighbors having close, or similar, or related semantical values (Clark, 1999).

Third, even more surprising and subtle: This feature of BH of mixed morphologic-semantic nature manifests not only the pervasiveness of the phenomenon of topologically neighboring verbs having semantically meaningful correlations—such correlations are often relating to the type of the particular letters involved (Clark, 1999).

Thus, the verb to go, “he-lamed-kaph”, meaning to progress step by step toward a goal, is both semantically and morphologically neighboring the verb “he-lamed-qoph”, meaning divide and portion, and not the verbs to go out, to go up, and to go down, which are neighboring the verbs to extend, to master, and to scrape or scratch, respectively.

The Ancient Hebrew Vocabulary Must Have Been Markedly Larger These exquisite—combinatorial, topological, and communicative—precision, efficiency, and

evocativeness are the real source of the so much deplored above difficulty of mechanical memorization of BH verbs, the difficulty which, according to (Ullendorff, 1971), would be considerably aggravated if the quoted manual should be written somewhen in between the third and second millennium BC: “It has, of course, long been recognized that the ancient Hebrew vocabulary must have been markedly larger than that preserved in the OT [Old Testament, alias Hebrew Bible]” (Ullendorff, 1971, p. 242).

Communicative Awareness and Inspirational Intelligence Inspirational Intelligence Hypothesis

Summarizing the above observations, we arrive at the following central problem of our project: Main problem. What is the meaning and what are the origins of these unique and fundamental attributes

of BH, primarily verbal language, with most of words of its dictionary derived from verbal roots? We speak

INTERPRETING SEMITIC PROTOLANGUAGE AS A CONLAG

185

here of the highly innate, morphologically most parsimonious, semantically efficiently involved formal structure of its verbal system, displaying also a unique language-alphabet relationship, closely resembling in particular, and yet vastly superior in its expressive power to humanly designed assembler languages.

Our conclusion, stipulated and developed below, cannot be formulated otherwise than: IIH (Inspirational Intelligence Hypothesis). The assumption that the hypothetical protolanguage

preceding BH and other known Semitic languages, and called here Semitic protolanguage, has appeared or emerged, spontaneously and during a relatively short period of time, in and from a single person or a single family. In other words, its emergence is of inspirational nature, sort of a very personal “poem”, reflecting the innermost vital, moral, spiritual, and intellectual “architecture” and aspirations of certain human beings.

The real presence of inspirational creativity—related to physics or biological, linguistic, cultural, and social contexts—is somehow eluding today the scientific curiosity. To confirm the reality and the validity of our intuition in the linguistic and cultural context, it will suffice to mention the example of the Russian poetic genius Alexander Puchkin (1799-1837) who almost singlehandedly initiated the modern culture of Russian language and literature, better—the Russian modern culture tout court (Bethea & Dolinin, 2005) (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. The Hebrew alphabet.

Communicative Awareness The computational modeling is today the most powerful technical universe for playing in, around, and out

different scenarios of emergence and evolution of natural languages (Jurafsky & Martin, 2000). Pre-adaptation for emergence, biological and cultural apparatuses for evolution and natural selection, genetic and archaeological evidence, etc. (Pinker & Bloom, 1990): Those are global scientific concepts and ideological schemes dominating our linguistic field—unfortunately without much success (Christiansen & Kirby, 2003).

Our approach will be different. To simplify, if not caricature the matter, one can compare it to methods of SETI (Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence) (Swift, 1993), without attributing to this modern field the importance its protagonists aspire.

More precisely, we will restrict our attention to hidden intelligent “communications” emanating from evolving historical forms of Semitic protolanguage, as those forms are reflected in the structure of its best preserved fossil, BH. Then we will try to understand the meaning of these communications and its implications for the problem of emergence of our Semitic protolanguage.

Historical Role of the Semitic Protolanguage For those of our readers who might be doubting the value of constructing a research project on emergence

of natural languages around such a “rare poisson” as BH, let us remark that we are sharing the assumption,

INTERPRETING SEMITIC PROTOLANGUAGE AS A CONLAG

186

many times and in many ways demonstrated linguisticly, that its Semitic protolanguage was the principal source for all modern European and many Asia-African languages (Huehnergard, 2011).

Verbal Structure of BH and of Its Protolanguage Verbal Triliterality

The Hebrew verb is known for its remarkable linguistic “enigmas” (McFall, 1982). Ours start with a trivial observation that, with the exception of several dozen double two-letter cases, all Hebrew verbs are triliteral, or triconsonantal—three-letter combinations over the Hebrew alphabet of 22 letters (see Figure 1). In other words, about 1,700 of these verbs can be presented by points of the discrete cube BH Verbs, BHV = 22 x 22 x 22 = 10,648.

There is no doubt that, taking by itself, its notoriety notwithstanding, this unique linguistic phenomenon should arise today one’s scientific curiosity—be it just because of the striking similitude of the abstract perfection and parsimoniousness of such an alphabetical coding of verbs to the way machine codes (low level, or assembly programming languages) (Pratt & Zelkowitz, 2001) are traditionally represented—by mostly three Latin letters combinations (abbreviations), with a very few codes having two- and four-, or more-letter names.

Add to this surprising formal similarity, first, the well-known but still lacking any evolutionary explanation fact that “Hebrew grammar is essentially schematic and, starting from simple primary rules, it is possible to work out, almost mathematically, the main groups of word-building” (Lambek & Yanofsky, 2006; Weingreen, 1959); and the second, even more surprising, subtle, of a mixed morphologic-semantic nature feature of BH—the pervasiveness of the phenomenon of topologically neighboring (for example, differing in only one letter position) verbs having semantically meaningful correlations, often related to the type of the particular letters involved (Clark, 1999).

The very existence of such a semantically meaningful relationship represents a novel, and for that matter, giant conceptual leap from the pure phonetical role an alphabet—interpreted by modern evolutionary theories as a phonetically oriented dead end of a gradual random simplification of the hieroglyphical systems (Healey, 1990)—supposed to play, and the change of the linguistic perspective at least as radical as the passage from a hieroglyphical coding of words-notions to their phonetically meaningful alphabetic protocols.

Organismic Linguistics Let us think now back to the mentioned above classical appreciation of the difficulties of BH: “[Its]

roots are almost entirely triliteral, with the result that, at first, the verbs at any rate all look painfully alike—e.g., malak, zakar, lamad, harag, etc.—thus imposing upon the memory a seemingly intolerable strain” (Davidson, 1916, p. vi).

Thus, because “language is one of the hallmarks of the human species—an important part of what makes us human” (Christiansen & Kirby, 2003) (our epigraph), one can conclude that profound intimate linguistic preferences of English speaking people yesterday and today are different from those of people who spoke the other day BH and, before, its protolanguage.

In other words, to this second category of women and men, the BH verbs were not at all looking alike! In particular, we observe that some points of the “verbal body” of BH were connected between them by

the sensitive passages—change of only one consonant—to their neighbors: Thesis: Organismic BH Linguistics. The compact trilateral “verbal body” of BH is an extremely

sensitive organismic fundament of human proto-Semitic linguistic ability.

INTERPRETING SEMITIC PROTOLANGUAGE AS A CONLAG

187

Triliterality as an Essential Feature of Semitic Protolanguage Were these properties specifically BH or were they “projected” on BH from more ancient proto-Semitic

languages? The modern redaction of the cited above classical BH grammar (Davidson, 1916) creates an impression

that this verbal BH compactness was acquired later: “The roots, whatever may have been their original form, are in the Old Testament almost entirely triliteral” (Mauchline, 1978, p. 6).

However, all studies of Semitic languages, living and dead, demonstrate convincingly that verbal triliterality was an essential feature of Semitic protolanguage. And this feature does not imply either particular difficulty—compared to modern English—to learn and to use this protolanguage, or poverty of its expressive power.

Quite to the contrary—whereas in the above English example (see “Triconsonantal Morphological Pervasiveness of Biblical Hebrew” of section “Introduction: BH (Biblical Hebrew) Perceived by Classical Linguists”) the verbs to go, to go out, to go up, to go down achieve semantical variations by outward combinatorial means applied to the unanalyzable basic word go, BH verbs are referring by their triliteral structure—which is related by vicinages to similar verbs and which implies the immanence of an alphabet—to some innermost realities of the human being:

Thesis: Verbal Body of Semitic Protolanguage. (1) Verbal body of Semitic protolanguage was an organismic (Goldstein, 1939/1995) linguistic system with explicit and deep links to biological, psychological, intellectual, spiritual, and social aspects of human life; (2) Morphologically, this verbal body was absolutely dominant, implying an extremely dynamic appeal to women and men exercising this protolanguage; (3) We cannot characterize in the same way the verbal body of modern Hebrew, even if its creators were very sensible to the ancient origins of that language; (4) As to the verbal systems of modern natural languages, they should be characterized as verbal collections, without any substantial universal and unifying links between verbs; (5) Verbal body similar to that of BH cannot be expected to appear in a process of acquiring accidental improvements. Its existence is the result of a linguistic construction—Semitic protolanguage was a constructed language—Conlag (Okrent, 2009); and (6) One can expect to partially reconstruct this system by understanding the semantical meaning and the alphabetic references of verbal neighborhoods in the BH verbal body.

Getting out of the Natural Selection Stampede to Clean up Our Epistemic Act Charles Darwin vs. Johannes Kepler

The challenge of our BH problem has been from the very beginning complicated by a universal, unspoken, and yet not less bounding methodological assumption that any evolutionary solution should be consistent with, if not inspired by, the natural selection paradigm (Gould, 2002).

More generally, Charles Darwin fundamental idea—before and independently of his elaborated doctrine—that the biological reality is permanently in a natural movement, in a flow of renewal, accompanied by accidental mutations, with some of them leading to radical improvement of species—this popularity has finally eliminated from the scientific horizons all “theological” interest à la Johannes Kepler (Wolfenstein, 2003) in Why?, Thanks to what?, For what purpose?, and Who? (Kepler, 1619). Thus, for example, the only ambition of Optimality Theory (Prince & Smolensky, 1993/2002/2004) was, and remains, to introduce and to investigate some natural constrains on the linguistic flow of languages—the flow supposed to bring our languages from speechless vocality or manual nothing to their modern splendor.

INTERPRETING SEMITIC PROTOLANGUAGE AS A CONLAG

188

We believe that the truth, at least in our case, turned out to be different, and the vision elaborated in this study has been won out by the author—looking since about 20 years for a meaningful interpretation of the mysterious linguistic phenomena outlined above—over the considerable psychological pressure, and at the prize of a painstaking sorting out the enormous body of relevant emergence-and-evolution-by-natural-selection publications, with their characteristic authoritative—because emanating from this theory of everything (Laughlin & Pines, 2000)—and yet, to our great disappointment, absolutely unconvincing, even if often computer-oriented and -supported, claimed Gray and Atkinson (2003).

Does Design Come After Evolution? A typical sample—a veritable statement of metaphysical faith, publicly and solemnly delivered by Robert

Dawkins (2005) and having the merit to be short, clear, and uncompromising—could help an outsider to have a taste of, without acquiring it for, the prevailing atmosphere:

I believe, but I cannot prove, that all life, all intelligence, all creativity and all “design” anywhere in the universe, is the direct or indirect product of Darwinian natural selection. It follows that design comes late in the universe, after a period of Darwinian evolution. Design cannot precede evolution and therefore cannot underlie the universe. (p. 5)

And many, many, too many have tried to be faithful to this condemnation of the design creativity to work out accidentally as it were: (1) biology (Dawkins, 1986), cosmology (Smolin, 2004), behavioral psychology (Crawford & Krebs, 1998), and lingustics (Pinker & Bloom, 1990); (2) all progress of sciences at large (Weinberg, 2001) and even more radically; (3) all intellectual endeavors and failures (Dennett, 2006) of humanity, if not; and (4) the very existence in, and ultimately, of the Universe (Dawkins, 2005).

The Prototype of Laplacian Mechanics To begin with, let us remind the reader that, historically, there is nothing new or extraordinary when a

venerable (in our case, spelled out by a 19th century economist (Malthus, 1803)) scientific concept outlives its epistemological usefulness and becomes an epistemological burden for science. Two following well-known precedents should illustrate the point:

Laplacian Mechanics created more than two hundred years ago and universally admired ever since—that is, until the advent of Maxwell’s, Poincaré’s, and Einstein’s theories—has ultimately lost its epistemological value for physics, to acquire instead an enormous ideological prestige as an authentic and unsurpassed in its perfection instance of reductionist philosophy which, in particular, underlay the corresponding dogmatic distortions of otherwise valuable scientific discoveries of, say, Charles Darwin, Karl Marx, and Sigmund Freud.

This is how Einstein (1998) has summarized the post-Laplacian epistemological crisis in physics:

We must not be surprised, therefore, that, so to speak, all physicists of the last [19-th] century saw in classical mechanics a firm and final foundation for all physics, yes, indeed, for all natural science, and that they never grew tired in their attempts to base Maxwell’s theory of electromagnetism, which, in the meantime, was slowly beginning to win out, upon mechanics as well. (p. 73)

Little has Einstein known, delivering this post-mortem of a formerly omniscient theory, that he himself has fallen under the spell of the commonly accepted—at least, since Isaak Newton—Classical Causality Doctrine of Space and Time, the very conceptual ground on which Pierre-Simon Laplace has proudly erected his miniature mechanical universe.

INTERPRETING SEMITIC PROTOLANGUAGE AS A CONLAG

189

To his credit, Einstein was able to spell out himself his difficulty to understand some quantum micro-phenomena incompatible with the classical causality doctrine, by inventing his now famous Gedanken experiment exhibiting, as he called it, a “spooky action on a distance”.

We speak here about the well-known, systematically exploited, and yet as poorly understood today as in Einstein’s times phenomenon of quantum entanglement that, after being discovered according to the very scenario advanced by Einstein and his colleagues as improbable (Einstein, Podolsky, & Rosen, 1935), dominates the modern research in Quantum Information Processing (Nielsen & Chuang, 2000).

Computer Metaphor as the First, Best Hope of Materialism The subtlety of this pure physical phenomenon, of its philosophical and theoretical repercussions and

accommodations, and of related theoretical experimental discoveries which might one day lead to the creation of presently still even theoretically unconceivable Quantum Computer, most strikingly contrasts with the 19th century scientism still limiting and burdening the imagination of many cognitive scientists—as illustrated by the following recent credo (Hobbs, 2007), found in the mentioned above and otherwise very instructive compendium (Arbib, 2007) on the mirror system hypothesis on the linkage of action and language:

[T]he central metaphor of cognitive science, “The brain is a computer”, gives us hope. Prior to the computer metaphor, we had no idea of what could possibly be the bridge between beliefs and ion transport. Now we have an idea. In the long history of inquiry into the nature of mind, the computer metaphor gives us, for the first time, the promise of linking the entities and processes of intentional psychology to the underlying biological processes of neurones, and hence to physical processes. We could say that the computer metaphor is the first, best hope of materialism. (Hobbs, 2007, p. 50)

What physical processes have had the author in mind formulating this statement of scientific belief: only classical, or quantum, the “spooky” ones including, or some other, now either on the stage of preliminary studies, or as yet not discovered, eventually even more paradoxical ones? What sort of Materialism informs his scientific vision—Laplacian, or Einsteinian, or more modern, said Zeilingerian (Zeilinger, 2005) (which would not be recognized as “Materialism” neither by Laplace nor by Marx, and probably not even by Dennett), or its futurist version, not yet invented? And on what idea of Computer relies his metaphor—the abacus, Charles Babbage’s programmable mechanical computer, the modern transistor-based, integrated circuit computer, the futurist quantum computer project, or a future computing device based on new revolutionary philosophical, physical, chemical, or other scientific principles, today not even dreamt about?

Natural Languages Without Natural Selection

In fact, transposed to such fields as the studies of the emergence and evolution of natural languages, of science (Belaga, 2008), etc., from the strictly biological scene—with its immense variety of species, genera, etc., with its times of engagement ranging from at most hundred years of life expectancy for an individual organism to at least millions and even billions of years for evolutionary processes to bring this or that organism to existence, and with the fundamental scarcity of the material traces (fossils) of both biological organisms and their evolutionary changes—natural selection conjecture becomes for the first time verifiable and, if it should be eventually the case, falsifiable (Popper, 1963).

This eventuality, neither deals there with, nor bears directly on our proceedings or conclusions, has everything to do with the three following well-known linguistic (and more general, cognitive) (Belaga, 2008) facts of fundamental epistemological importance—with particular instances of the second and the third ones

INTERPRETING SEMITIC PROTOLANGUAGE AS A CONLAG

190

providing us, as it was already mentioned above (see “Three Extraordinary Fundamental Linguistic Phenomena” of section “Introduction: BH (Biblical Hebrew) Perceived by Classical Linguists”), with both the object and instruments of our enquiry:

First, the number of natural languages, living or dead, does not exceed several hundreds, with the life span of a typical natural language, our linguistic “organism”, varying from several hundred to several thousand years, compared to at most several million years of modern languages existence; respectively, the number of principal natural languages families (the linguistic genera) does not exceed several dozens.

Second, the linguistic “fossils” are relatively numerous, very well preserved, and mostly very good documented and studied—to faithfully testify both to the state of particular languages at particular historical junctures and to their evolutionary changes.

Third and last, but not least, linguistics is the theory of language used in materially preserved exchanges, sometimes very intelligent and detailed, between individuals and personal announcements, sometimes very deep and substantial. These exchanges and announcements bear in many cases some important information about the emergence of the language:

Thesis: Higher Memory Level of Linguistic Fossils. Alongside the traditionally studied first, or low, or material memory level of linguistic fossils extracted from preserved (and mostly archeologically retrieved) inscriptions and texts—the level corresponding to the one and only one known in the case of biological fossils—fossilized languages often possess a higher memory level: the stories told by preserved texts about the (history of the) very language in which they were written.

As in the case of the first level memory possessing by preserved inscriptions and texts, but on a different methodological basis, the stories which preserved the higher memory level need a careful and critical examination before being admitted as trusted testimonies to the history of the language in question. But if ultimately admitted, the extracted information, otherwise unavailable, might be of an extraordinary importance: Just imagine that, alongside our studies of fossils of an extinct dinosaur, we could also hear from him his generation’s story!

Conclusions Our approach reverses the only direction of research known today toward the origins and structural

meaning of natural languages. We believe that, similar to physical phenomena, we should learn a lot from their original and fully independent of simplistic evolutionary paradigms structures.

References Arbib, M. A. (Ed.). (2007). Action to language via the Mirror Neuron System. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Belaga, E. (2008). In the beginning was the verb: The emergence and evolution of language problem in the light of the big bang

epistemological paradigm. Rivistadi Filologia Cognitiva (Cognitive Philology), 1(1), 1-17. Bergen, R. D. (Ed.). (1994). Biblical Hebrew and discourse linguistics. Winona Lake, USA: Eisenbrauns. Bethea, D. M., & Dolinin, A. (2005). The Pushkin handbook. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. Christiansen, M. H., & Kirby, S. (2003). Language evolution: Consensus and controversies. TRENDS in Cognitive Sciences, 7(7),

1-15. Clark, M. (1999). Etymological dictionary of Biblical Hebrew: Based on the commentaries of Samson Raphael Hirsch. Jerusalem:

Feldheim Publishers. Crawford, C. B., & Krebs, D. L. (Eds.). (1998). Handbook of evolutionary psychology: Ideas, issues, and applications. Mahwah,

N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum Ass..

INTERPRETING SEMITIC PROTOLANGUAGE AS A CONLAG

191

Davidson, A. B. (1916). An introductory Hebrew grammar with progressive exercises in reading, writing and pointing. Edinburgh: Clark.

Dawkins, R. (1986). The blind watchmaker: Why the evidence of evolution reveals a universe without design. Bethesda, M.D.: Adler & Adler.

Dawkins, R. (2005, January 3). What do you believe is true even though you cannot prove it?. New York Times, p. 5. Dennett, D. (2006). Breaking the spell: Religion as a natural phenomenon. London: Penguin. Ehret, C. (1995). Reconstructing proto-Afroasiatic (proto-Afrasian): Vowels, tone, consonants, and vocabulary. Berkeley:

University of California Press. Einstein, A. (1998). Autobiographical notes. In P. A. Schilpp (Ed.), Albert Einstein: Philosopher-scientist (pp. 1-95). London:

Cambridge University Press. Einstein, A., Podolsky, B., & Rosen, N. (1935). Can quantum mechanical description of physical reality be considered complete?.

Phys. Rev., 47, 777. Gesenius, H. F. W. (1813). Hebraische grammatik. (E. Kautzsch Trans.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. Gesenius, H. F. W. (1952). A Hebrew and English lexicon of the old testament. USA: Oxford University Press. Goldstein, K. (1939/1995). The organism: A holistic approach to biology derived from pathological data in man. New York:

Zone Books. Gould, S. J. (2002). The structure of evolutionary theory. Cambridge (Massachusetts) and London: The Belknap Press of Harvard

University Press. Gray, R. D., & Atkinson, Q. D. (2003). Language-tree divergence times support the Anatolian theory of Indo-European origin.

Nature, 426, 435-439. Healey, J. F. (1990). The early alphabet (reading the past). Berkeley: University of California Press. Hobbs, J. R. (2007). The origin and evolution of language: A plausible, strong-AI account. In M. A. Arbib (Ed.), Action to

language via the Mirror Neuron System (pp. 48-88). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Huehnergard, J. (2011). Proto-Semitic language and culture. The American heritage dictionary of the English language (5th ed.,

pp. 2066-2078). Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Company. Joosten, J. (2012). The verbal system of Biblical Hebrew: A new synthesis elaborated on the basis of classical prose. Ein Kerem,

Jerusalem: Simor Ltd.. Jurafsky, D., & Martin, J. H. (2000). Speech and language processing: An introduction to natural language processing,

computational linguistics, and speech recognition. Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Prentice Hall. Kepler, J. (1619). Harmonices Mundi. In J. Field (Trans.), The harmony of the world. Philadelphia: The American Philosophical

Society. Lambek, J., & Yanofsky, N. S. (2006). A computational approach to Biblical Hebrew conjugation. Retrieved from

http://www.sci.brooklyn.cuny.edu/˜noson/hebrew1.pdf Laughlin, R. B., & Pines, D. (2000). Theory of everything. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States

of America, 97(1), 28-31. Malthus, T. R. (1803). An essay on the principle of population, or, a view of its past and present effects on human happiness, with

an inquiry into our prospects respecting its future removal or mitigation of the evils which it occasions (2nd ed.). London: Johnson.

Mauchline, J. (1978). Davidson’s introductory Hebrew grammar (26th ed.). Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark. McFall, L. (1982). The enigma of the Hebrew verbal system: Solutions from Ewald to the present day. Cambridge: The Almond

Press. Nielsen, M. A., & Chuang, I. L. (2000). Quantum computation and quantum information. Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press. Okrent, A. (2009). In the land of invented languages: Esperanto rock stars, Klingon poets, Loglan lovers, and the mad dreamers

who tried to build a perfect language. New York: Spiegel & Grau. Paty, M. (1993). Einstein philosophe: La physique commepratiquephilosophique (Einstein philosopher: Physics as a practical

philosophy). Paris: Presses Universitaires de France. Pinker, S., & Bloom, P. (1990). Natural language and natural selection. Behavioural and Brain Sciences, 13(4), 707-784. Popper, K. R. (1963). Conjectures and refutations: The growth of scientific knowledge. London: Hutchinson. Pratt, T. W., & Zelkowitz, M. V. (2001). Programming languages: Design and implementation (4th ed.). Upper Saddle River,

New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

INTERPRETING SEMITIC PROTOLANGUAGE AS A CONLAG

192

Prince, A., & Smolensky, P. (1993/2002/2004). Optimality theory: Constraint interaction in generative grammar. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers.

Smolin, L. (2004). Cosmological natural selection as the explanation for the complexity of the universe. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and Its Applications, 340(4), 705-713.

Swift, D. W. (1993). Seti pioneers—Scientists talk about their search for extraterrestrial intelligence. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

Ullendorff, E. (1971). Is Biblical Hebrew a language?. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, 34(2), 241-255.

Weinberg, S. (2001). Facing up: Science and its cultural adversaries. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. Weingreen, J. (1959). A practical grammar for classical Hebrew (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. Wolfenstein, L. (2003). Lessons from Kepler and the theory of everything. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of

the United States of America, 100(9), 5001-5003. Zeilinger, A. (2005). The message of the quantum. Nature, 438, 743.

US-China Foreign Language, ISSN 1539-8080 March 2014, Vol. 12, No. 3, 193-203

Teaching Effect of Contrasting Intonation Systems*

Hanako Hosaka Tokai University, Kanagawa Prefecture, Japan

Not many language learners have been taught the sound system systematically. Intonation is no exception. This

paper aims to show the effectiveness of contrasting TL (target language) and L1 (first language) intonation

systems for the learners to become aware of the TL intonation system as something new and different from what

they are familiar with. The Japanese-speaking subjects showed a better understanding of the English intonation

system after the instruction on the functions of the five-tone choices in English speech. While they were “aware”

of “intonation” as a phenomenon, they did not know “how intonation works”, nor were very aware of any

differences between TL intonation and the intonation they are familiar with, such as L1 and mother tongues.

Therefore, it is better not only to teach the technical rules in intonation, but also to develop the ability to use

intonation in TL appropriately in context. Teaching TL intonation system by contrasting with L1 can help the

learners to systematically learn how intonation works in TL.

Keywords: contrast, teaching effect, intonation system, English, Japanese

Introduction

It is not always easy for language learners to get the idea of the intonation system in other languages, and it is rarely the case that language learners have been taught the sound system systematically. For example, most of the English major students enrolled in the author’s “Introductory Phonetics Course” say that they had never learned the English sound system before the enrolment, and that they wished they had learned it earlier. Likewise, Nakagawa (1996, pp. 106, 115) pointed out that not many learners of Japanese have learned the Japanese sound system including accent and intonation, and she hoped for developing systematic teaching materials for the Japanese sound system. This paper shows that contrasting two intonation systems between TL (target language) and L1 (first language) is effective for the learners to become aware of the “new” intonation system they are acquiring.

The author applies the Discourse Intonation Model (Brazil, 1985, 1994; hereafter DI Model) to both English and Japanese to make a fair contrast. The DI Model is originally designed to capture the “communicative value” of intonation in English discourse contexts. It can be considered as a way of investigating intonation in the discourse analysis framework, looking at “the meaning of intonation” (Brazil, 1997, p. ix) functionally in a stream of natural speech. As shown in Hosaka (2004b, p. 207), the DI Model (originally proposed for English) is

* Acknowledgements: The author would like to acknowledge Prof. Yoshihiro Nishimitsu for his various kinds of contributions in the linguistics fields. His flexible approach and the idea of contrast in language have influenced the author in pursuing sound studies and applied linguistics.

Hanako Hosaka, associate professor, Department of English, School of Letters, Tokai University.

DAVID PUBLISHING

D

TEACHING EFFECT OF CONTRASTING INTONATION SYSTEMS 194

suitable in describing oral data in Japanese, as well as variations in L1/L2 (second language) English. Also Yamato (2000) evaluated the DI model as “the most appropriate system to utilise for intonation teaching”, because it “focuses on communication and discourse, as well as holding the balance in terms of simplicity of notation system”, whereas other existing intonation theories “focus on linguistic descriptions” (pp. 98-99). Hence, the author considers that it is possible to teach the basic patterns of discourse intonation in English to Japanese EFL (English as a foreign language) learners with the DI model.

In this study, the author gave a lesson focusing on the usage of Brazil’s five different tone choices in English to Japanese EFL learners at the undergraduate level, and introduced them to the differences of the tones and their meanings while letting them imagine their use of intonation in Japanese. For the purpose of teaching the basic intonation patterns, the author focused on the use of TUs (tone units) with one lexical item (e.g., “yes” and “well”) in context, and then let the students use the five tones in a little longer TUs. This method is motivated on the three points (Hosaka, 2004a, p. 13): (1) The pronunciation of lexical items needs to be dealt with in the stream of speech as well as in citation forms (as shown in dictionaries with International Phonetic Alphabets); (2) It is helpful to be aware of the L1 tendencies in discourse intonation at the lexical level (in comparison to TL tendencies); and (3) Non-native speakers can become aware of the communicative usage of TL intonation through appropriate instructions.

The author compared the students’ tone transcriptions before and after the lesson, and analyzed the effect of the lesson. This paper discusses the following points: (1) comparison between English and Japanese intonation systems; (2) teaching of basic English intonation to Japanese EFL learners by comparing the five different tone choices; and (3) the effect of teaching the English intonation system in contrast with the Japanese system.

This paper aims to show the effectiveness of the contrastive approach between TL and L1 in L2 acquisition and foreign language teaching.

Comparison Between English and Japanese Intonation

Characteristics of English and Japanese Intonation in Contrast In both English and Japanese, the intonation system helps to add an “extra” meaning to the original

dictionary meaning. We acquire it very early in the L1 acquisition process. According to Ogura (2005, pp. 32-35), from around five months before birth, fetuses can recognize patterns in intonation and stress from the mothers’ speech through the amniotic fluid; and infants’ babbling starts sounding with intonation after 0;10. According to Cruttenden (1979, as cited in Suganuma, 1993, pp. 5, 19), a child starts to discriminate and produce differences in pitches, loudness, length of sound, and voice qualities from neonates, and “during the one-word stage or early in the two-word stage he may begin to use the difference between a falling and a rising pitch pattern systematically” (p. 19). According to Guernsey’s (1928) research on 200 infants from 0;2 to 1;9 (as cited in Murata, 1968, p. 23), the influence of L1 discourse appears in infants’ intonation long before their speech starts sounding like L1. Since then they usually use it unconsciously in their L1 speech.

This means that L1 intonation would easily stay as part of the core of the “new” language system. Intonation is more likely to cause language transfer from L1 to TL (= L2) (Hosaka, 1996a, 1996b).

Because of this aspect, the author considers it is effective to make a clear contrast between TL and L1 in teaching TL, so that the learners can utilize the awareness of the TL-L1 contrast in using TL.

TEACHING EFFECT OF CONTRASTING INTONATION SYSTEMS 195

As for five-tone choices in the DI Model, while the majority of English tone use is p, r+, r, and o tones, that of Japanese tone use is p, r+, and o tones. Table 1 shows an example of tone choices in English and Japanese: Both languages have similar systems, with different frequencies in tones.

Table 1 Example of Tone Choices in English and Japanese (Percentages of Each Tone Choice Frequency)1 English // it is RAINing // (%)

Brazil’s five-tone choices Japanese // Ame desu ka // (%)

It is raining! (surprise, unexpected) 0.3 p+ rise-fall /\ 0.1 It is raining! (surprise, unexpected) It is raining. (statement) 47.8 p fall \ 74.5 It is raining. (statement) It is true it is raining. (expected and not interested)

11.3 o level _ 16.0 It is raining… (expected and not interested)

Is it raining? 30.5 r+ rise / 6.2 Is it raining? Is it really raining? 6.4 r fall-rise \/ 2.1 Is it raining? (more involved) Cf. // aME desu ka //

(= candy)2 Note. Adapted from Hosaka, 2004b, p. 206.

Table 2 is the summary of the characteristics of English and Japanese intonation (Hosaka, 2004b, p. 203).

Table 2 Intonational Comparison Between English and Japanese English Japanese Indo-European Group Non-Indo-European SVO (Subject+Verb+Object) Word order SOV (Subject+Object+Verb) Intonation language (determined by discourse structure) intonation + rhythm intonation > accent

Typology

Word-pitch language (determined by word accent structure) accent + pause accent > intonation

Prosodic & discoursal unit At least 1 primary accent (optionally with pause and/or lengthening)

TU Prosodic & pausing unit Boundary low tone + pause (often with pragmatic particles)

Discoursally various

Intonation patterns Fall = certainty Rise = uncertainty Level = continuation

Fairly fixed

Primarily for intonation purposes Pitch Mainly for accentual purposes “stress accent” movable depending on intonation and rhythm

Accent “pitch accent” immovable, predictable

Note. Adapted from Hosaka, 2004b: based on Hosaka, 1996a, 1996b, cf. Cruttenden, 1986; Kubozono, 1995; Beckman & Pierrehumbert, 1986.

As in Tables 1-2, it is possible to contrast the intonation systems of the two languages in the same DI Model. In addition, using the same model, it becomes easier to show the similarities and differences in the intonation system in different languages: in this case, teaching English to Japanese EFL learners.

1 The frequencies of each tone choice were analyzed in Hosaka (in progress) in the context of reading aloud. The total of the five tones in Table 1 does not make 100%, because 3.7% in the English data and 1.1% in the Japanese data did not have clear tones to be uniquely identified as one of them. 2 In Japanese, it is possible to distinguish meanings solely by the use of prominence in speech, as in // Ame // (rain) and // aME // (candy). This is similar to the distinction of // CONduct // (noun form) and // conDUCT // (verb form) in English.

TEACHING EFFECT OF CONTRASTING INTONATION SYSTEMS 196

The author considers the systematic teaching of intonation would help the L2 learners become more aware of the “new” intonation system in TL.

Research Questions In the author’s other ongoing research in teaching listening in English to Japanese EFL learners, she found

as follows: (1) Japanese EFL learners tend to be aware of their difficulty in “listening”; and (2) Nearly half of them can be successfully improved their listening skill in English by instruction in how to listen.

The research questions in this paper are: Could the same logic apply to teaching intonation? If we give the students instruction on English intonation systematically, would it improve their listening skill?

Teaching Basic English Intonation to Japanese EFL Learners by Contrasting the Five Different Tones

Subjects The author gave a lesson on the basic English intonation system with focus on the five tones as in Table 1 to

the total of 64 Japanese students in four regular English language classes for undergraduate focused on listening. The subjects were undergraduate Japanese EFL learners at two Japanese universities. Their English levels varied to some extent, mostly in the range of low- to high-intermediate. The author compared their tone choice perception at between pre- and post-instruction.

Teaching the English Tone Choice System In order to teach the tone choices, the author made a set of handouts (based on Utsu & Schaefer, 1989/2001,

pp. 30-36; Brazil, 1994, 1997; Bradford, 1988) as a teaching material. She designed it as one lesson to cover the five-tone differences in context sound-wise and meaning-wise. For data collection in this lesson, the author included a short dialogue in the handouts. Considering the subjects’ English level, the dialogue contains only p (\) and r+ (/) tones in the context, which are common in Japanese intonation as well.

The procedure of the English tone choice lesson goes as follows: (1) introduction of the five-tone choices in English. The author introduced each pitch move pattern and the simplified codes to transcribe it (using arrow signs to mark pitch moves); (2) explanation of the basic contrast between English and Japanese intonation; (3) listening to the model dialogue [ Pre-instruction]. The subjects listen to a short model conversation between a man and his wife, and try to transcribe the tones used in this dialogue3; (4) comparison of a simple dialogue with different tone choices. They are asked to compare a dialogue between A and B, and imagine how A would answer in the given different situations; (5) learning the differences in the use of intonation. Continued from (4), the handout presents the differences in the use of intonation—each tone and its meaning; (6) prosodic introduction to the five different tones in English. The author reads the same lexical item in the five different tones. The subjects focus on the tones and transcribe each tone; (7) guessing their meanings or functions. They are asked to guess the meaning or function of each tone; (8) explanation in context. The handout explains meanings for each tone in the same context; and (9) reviewing the model dialogue [ Post-instruction]. They listen to the same dialogue again, and transcribe the tones4.

3 In Pre-instruction, the author told the subjects, “Listen to the following conversation between a man and his wife. Try to transcribe the tones used in this conversation”. Then in Post-instruction, “Listen to the following conversation between a man and his wife AGAIN. Transcribe the tones used in this conversation”. 4 See the third footnote.

TEACHING EFFECT OF CONTRASTING INTONATION SYSTEMS 197

The data in this study are the two attempts in tone transcription of the model dialogue by the subjects in the lesson, i.e., Pre-instruction and Post-instruction ((3) and (9) above).

Results: Transcribing the Five-Tone Choices

Model Dialogue Used in the Data Collection As described earlier, the subjects were asked to try transcribing the tones used in the model dialogue as the

data source material before and after the instruction on the basic English intonation system. The author asked them to write the tones using arrow signs, so they could easily visualize what they heard in the context.

The model dialogue used in the lesson (added the DI transcription on the original dialogue used in Utsu & Schaefer, 1989/2001, p. 31):

[Imagine the context5: The husband came home after work and was starting to unwind. His wife asks him.] Wife: // r+ ANYthing to DRINK // Husband: // p HMM // Wife: // r+ WELL // Husband: // p YES // p WELL // p OK // Wife: // r+ BEER // p or SAke // Husband: / p BEER // Wife: // r+ with poTAto CHIPS // Husband: // p NO // p THANKS // Wife: // r+ here you ARE // Husband: // p THANK you //

The model dialogue has 14 TUs6. It is consisted of only p (fall) and r+ (rise) tones as for the tone choices. Hence, the subjects’ attempts were to tell which tone out of the five choices was used in each TU in the model dialogue as they listened.

Pre-instruction Result Table 3 is the pre-instruction result of the subjects’ attempt of transcribing the tone choice in the model

dialogue. The dark-shaded columns are the correct transcription of the tone used in each TU. The bold numbers are the most preferred tone transcription by the subjects.

The findings from Table 3 are: (1) Nearly half of the subjects successfully transcribed in most of the TUs; (2) When the p tone was used, most of the subjects guessed it was either p+, p, or o; (3) When the r+ tone was used, most of them guessed it was either r or r+; (4) In spite that there was no o tone used in the model dialogue, all of the TUs expect 1 in Table 3 had quite a few subjects guessed as the o tone (e.g., 9, 11, 12 in Table 3); and (5) Although p+ and r rarely occur in English as Table 2 shows, the subjects could not seem to tell them well (e.g., 6 and 8 for p+, 3 and 13 for r in Table 3).

These findings reflect the Japanese tone preference in Table 1 as follow: Tone preference (based on Table 1)

5 The original textbook shows the context in a picture. 6 In Discourse Intonation Model, a “TU”, transcribed between a set of double slashes, is used as the unit in intonation including one tone choice occurred in one of the prominences. Brazil (1997) stated it as “the stretch of language that carries the systemically-opposed features of intonation” (p. 3). This is equivalent to “intonation unit” in other intonation theories.

TEACHING EFFECT OF CONTRASTING INTONATION SYSTEMS 198

Japanese: p (3/4) > o (1/6) > r+ (1/15) > r > p+. English: p (1/2) > r+ (1/3) > o (1/10) > r (1/15) > p+. Hence, the default tone choice for Japanese EFL learners would be p or o, while they are supposed to learn

the English way of using each tone.

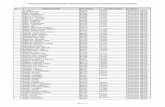

Table 3 Pre-instruction Attempt of Transcribing the Tone Choices in the Model Dialogue No. TUs Tone used p+ (/\) p (\) o (_) r (\/) r+ (/) 1 // anything to drink? // r+ 18 45 2 // hmm. // p 12 40 8 1 2 3 // well? // r+ 1 1 25 34 4 // yes. // p 7 30 17 1 4 5 // well, // p 10 30 21 1 6 // OK. // p 22 23 13 2 3 7 // beer // r+ 6 8 14 34 8 // or sake? // p 23 19 2 4 13 9 // beer. // p 22 32 8 10 // with potato chips? // r+ 2 15 45 11 // no, // p 4 43 12 12 // thanks. // p 2 32 25 13 // here you are. // r+ 4 7 12 26 12 14 // thank you. // p 13 25 18 5 Note. Only the valid answers are counted in this table.

Pre-instruction vs. Post-instruction Figure 1 is the comparison of the numbers of the subjects according to the numbers of correct answers in the

14 TUs in the model dialogue between Pre- and Post-instruction. The data include all the 64 subjects, including four of those marked as n/a because of no answers written down in either Pre- or Post-instruction. The result is categorized into four score groups according to the numbers of correct answers out of 14 TUs as follow:

Four-score groups: score 0-3, score 4-6, score 7 to 10, score 11 to 14

Figure 1. Pre- vs. Post-instruction result (counted by the number of subjects).

TEACHING EFFECT OF CONTRASTING INTONATION SYSTEMS 199

Figure 1 shows the lower-score groups became smaller (from 56% to 42%), and the higher-score groups became larger (from 42% to 53%). This means even one lesson concentrated on intonation was effective.

Teaching Effect Comparison According to the Score in Pre-instruction The author categorized the teaching effect by comparing each subject’s Pre-instruction answer with its

Post-instruction answer per each TU as in Table 4.

Table 4 The Teaching Effect Categories Used in the Analysis Teaching effect Pre-instruction Post-instruction Explanation Positive Incorrect Correct Improved after instruction

Neutral Correct Correct

No change after instruction Incorrect Incorrect

Negative Correct Incorrect Got worse after instruction n/a n/a in either or both of Pre- and Post-instruction INVALID to show the effect

Figure 2 is the teaching effect in total counted by the number of TUs (out of 840 TUs = 14 TUs x 60 valid subjects), using the four categories above. When counted by the numbers of TUs, 22% of the TUs (181 out of 840) showed positive effect. It is notable that 11% showed negative effect, probably because the subjects might have confused until they would fully digest the new knowledge of tone choices.

Figure 2. Teaching effect in total (counted by the number of TUs).

Figure 3 is the teaching effect in total (counted by the number of TUs out of 840 TUs) compared by the score groups as in “Four-score groups: score 0-3, score 4-6, score 7 to 10, score 11 to 14”, using the four categories in Table 4. The top “total” bar is the same as in Figure 2, as reference to each score group.

Figure 3 indicates: (1) All the four-score groups show similar tendencies in teaching effect; (2) The lower-score groups show more of positive teaching effect (24% in 0-3, 26% in 4-6, 18% in 7-10, and 10% in 11-14); and (3) The higher-score groups show less of positive effect, and a little more negative effect instead (7% in 0-3, 12% in 4-6, 13% in 7-10, and 14% in 11-14).

TEACHING EFFECT OF CONTRASTING INTONATION SYSTEMS 200

Figure 3. Teaching effect: by the score groups (counted by the number of TUs)

Therefore, from Figures 2-3, even one lesson concentrated on intonation had positive teaching effect in 22% of the TUs in all the valid subjects, and the positive effect was bigger in the lower-score groups. On the other hand, 11% of the TUs showed negative effect, and it was slightly bigger in the higher-score groups. This implies overt intonation instruction may be more effective in lower intermediate level.

Teaching Effect Comparison Between p and r+ Tones In the 14 TUs in the model dialogue (3), there are nine p TUs and five r+ TUs. The author presents Figures

4-5 to compare the teaching effect between p and r+. Figure 4 is the teaching effect compared between p vs. r+ tones counted by the number of TUs. In Figure 4,

the author counted only the correct answers, and the numbers of correct answers increased in both p and r+ tones after instruction (i.e., 8.5% increase (38.1% 46.6%) in p TUs, 11.3% increase (49.0% 60.3%) in r+ TUs).

Figure 4. Teaching effect: p vs. r+ tones (counted by the number of TUs).

TEACHING EFFECT OF CONTRASTING INTONATION SYSTEMS 201

Figure 5 is the teaching effect rate compared between p vs. r+ tones counted by the number of subjects. The author uses “positive”, “neutral”, and “negative” labels for the teaching effect rate, as in Table 4.

Figure 5. Teaching effect rate: p vs. r+ tones (counted by the number of subjects).

Figure 5 shows: (1) The teaching effect rate results on p TUs and r+ TUs were almost the same; and (2) In both p TUs and r+ TUs, about half of the subjects showed positive effect (50% in p TUs, 48% in r+ TUs).

Therefore, from Figures 4-5, even one lesson concentrated on intonation had positive teaching effect in both p TUs and r+ TUs in all the valid subjects, and both showed very similar tendencies.

Subjects’ Reactions to the Intonation Lesson

After this lesson on discourse intonation, the author asked the subjects if they were aware of the functions of intonation in English before the instruction. Forty-four of them gave valid answers as in Table 5.

Table 5 The Subjects’ Reactions to the Intonation Lesson Were you aware of the functions of intonation in English? Valid answers: 44 Not aware 0 0% Aware but didn’t know the details 38 86.4% Aware but can’t distinguish the differences 5 13.6% Fully aware 0 0%

Table 5 shows the subjects were “aware” of “intonation” as a phenomenon, but did not know “how intonation works”. Examples (1)-(3) represent the subjects’ comments after the lesson (translated from Japanese).

Example (1) It is difficult to listen to the differences between the tone choices. Example (2) I have realised I have been using the tone choices unconsciously. Example (3) I learned the tone choices make differences in what the speaker means.

TEACHING EFFECT OF CONTRASTING INTONATION SYSTEMS 202

Conclusions