The Tabula Peutingeriana - Its Roadmap to Borderland Settlements in Iudaea-Palestina, with Special...

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

0 -

download

0

Transcript of The Tabula Peutingeriana - Its Roadmap to Borderland Settlements in Iudaea-Palestina, with Special...

36 NEAR EASTERN ARCHAEOLOGY 75:1 (2012)

IntroductionOne nineteenth-century geographer eloquently described

the western slopes of the Judean hill country as “that natu-ral rampart” which formed the best defense for the highland cultures (Ritter 1866, 246). At the base of this topographical feature, the ancient town at Tel Zayit (figs. 1–2) lay on a road running through the Nahal Guvrin out to the large port at Ashkelon and thereby guarded access from an important sec-tor of the southern coast to highland interchanges between Jerusalem and Hebron. The 30-dunam site held a strategic position at the mouth of the Guvrin Valley: 1.76 km west and 7.06 km north of Lachish; 1.66 km west and 8.09 km south of Tell es-Sâfi; 26.96 km east and .74 km south of Ashkelon; and 4.1 km due west of Tell Bûrnah (fig. 3).1 Moreover, Tel Zayit was located only 6.15 km west of Eleutheropolis (Beit Jibrîn, modern Beth Guvrin), the reference point from which both the Romans (judging from extant milestones and the Tabula Peutingeriana [hereafter TP]; Weber 1976; Miller 1916; Talbert

2010) and Eusebius of Caesarea (Onomasticon) gauged dis-tances and located towns throughout the general region.

When viewed through the lens of historical and comparative methods espoused by the Annales school of historiography (compare Braudel 1972; 1980, 25–54; Bloch 1953; 1974; 1995), the remains thus far exposed at Tel Zayit speak to the enduring status of the town’s strategic position as a borderland commu-nity. Consideration of the interplay between coastal sites and those in the lowlands plus the inland valleys they protected proves especially relevant to the history of a site such as Tel Zayit. Five illustrative snapshots taken from the 3,500-year depositional history of the tell amply demonstrate the limin-ality of daily life that the inhabitants surely understood. The collage includes: (1) Tel Zayit’s shifting allegiances during the tenth and ninth centuries b.c.e.; (2) its resultant participation in an economic network that bridged the highland and coastal cultures; (3) its fate in the wake of Sennacherib’s Third Cam-paign in 701 b.c.e.; (4) its service to the Romans as a fortified

Ron E. Tappy

The Tabula PeutingerianaIts Roadmap to Borderland

Settlements in Iudaea-Palestina

With Special Reference to Tel Zayit in the Late Roman Period

To Gabriel Barkay — Teacher, Colleague, FriendThe one exclusive sign of a thorough knowledge is the power of teaching. —Aristotle

NEAR EASTERN ARCHAEOLOGY 75:1 (2012) 37

outpost; and (5) the bearing of its political compass during the Turkish-Ottoman and British-Mandate periods. Since I have elsewhere provided a full discussion of the liminal-zone con-cept (Tappy 2008c) and, in separate studies, addressed the first three topics in this list (Tappy 2000; 2008a; 2008b; Tappy et al. 2006), I shall now supplement those analyses by taking a long-range view that follows the theme of borderland communities through the classical and postmedieval periods, particularly as that theme relates to Tel Zayit.

The Local Physical Setting: Evolution of the Tell and Related Scholarship

Tel Zayit made its debut in modern scholarship during the nineteenth-century British surveys. Conder and Kitchener (1998, 258) noticed the tell in their March 1875 Survey of Western Palestine (figs. 4–5) but recorded seeing only “a little

hamlet of mud in a valley, with low hills on either side” and “a well to the north.” The direct ancestor of this modern vil-lage had established itself on the southern bank of the Nahal Guvrin as early as the late sixteenth century c.e. More recent surveys suggested that beneath this erstwhile “hamlet of mud” lay the remains of a succession of ancient towns which, at vari-ous periods, held this strategic position at a principal access to Judah’s hill country.

Eighty years after the British survey, during a brief visit to the area in 1954, Y. Aharoni and R. Amiran also noticed the small but rather high tell situated immediately north of Route 353 and known locally as Khirbet Zeita el-Kharab. Later that year, their brief statement in a bulletin from the Israel Explora-tion Society recorded that the mound rose up in two stages, with the southernmost section rising higher (Aharoni and Amiran 1954, 224). Though their meager collection of surface

pottery ranged from the Late Bronze Age to the Arabic period, they attributed the bulk of their ceramic evidence to the Iron Age and concluded that the site represented a primarily Judahite settlement on the border of Philistia.

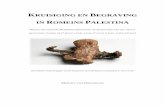

Figure 2 (right). View of Tel Zayit, looking south. Photograph by Ron E. Tappy.

Figure 1 (left). View of Tel Zayit, looking south. Photograph by Ron E. Tappy.

38 NEAR EASTERN ARCHAEOLOGY 75:1 (2012)

Supplementary surveys of the Shephelah from the late 1970s to the present extended the chronological range of pottery surviving on the tell’s surface from the Middle Bronze Age to the Late Ottoman period. In addition, they recorded traces of a burnt mudbrick wall on the eastern side of the mound plus a well on the northwestern edge of the occupation area (both features now confirmed by our excavations), expanded the repertoire of LBA pottery (which included a faience bowl), and published a scarab from Dynasty XIX or XX (Archaeo-logical News 1979, 31; Dagan 1992; Tappy 2000). Dagan (1992, 153) estimated the overall habitation area of Tel Zayit to cover at least 25 dunams, an area much larger than earlier assess-ments of 15 dunams. Dagan also recognized four pillars of stone (worked monoliths) rising to a height of 1.2 m in a lower settlement at the northwestern foot of the mound.

Since 1998, archaeological exploration at Tel Zayit has pro-ceeded under the direction of Ron E. Tappy and the spon-sorship of Pittsburgh Theological Seminary.2 Thus far, the project has exposed occupational levels ranging from LBA I through the Late Ottoman period. The overall town planning remained constant in each successive building phase; virtu-ally all architectural elements, regardless of their date, follow the same northwest-to-southeast orientation. Nowhere do the buildings or walls on the summit meet the existing slope of

the tell at a perpendicular angle or run parallel to the line of its shoulders. Even on the mound’s eastern shoulder and slope, where fieldwork has opened the greatest exposure, no trace of a fortification system (city wall or rampart) has yet appeared. Instead, all architectural features exposed in this area run diagonally to the edge of the existing tell, where they are then cut off as a result of later disturbances. It seems, therefore, that the present-day slope, at least on the eastern side of the site, reflects neither the contours nor the extent of the ancient site. Rather, this location likely lay a considerable distance insidethe ancient town. Today, local citizens preserve oral tradition that throughout modern memory residents around the tell harvested substantial quantities of agricultural soil from this side of the mound. (Dagan’s survey noted evidence of clan-destine digging at the site.) Consequently, an undetermined portion of the site is now missing, and the original town limits apparently extended much farther to the east than the current slope suggests. This circumstance dramatically alters the over-all portrait of the site from that of a relatively small village to one of a sizeable town or city, presumably one of much greater political and economic import.

The modern robbing of soil from the eastern side of the mound created a very steep grade down which a significant volume of water has drained in a northeasterly direction

Figure 3. Valleys and selected sites in the Judahite Shephelah and the Plain of Philistia.

NEAR EASTERN ARCHAEOLOGY 75:1 (2012) 39

Figure 4 (above). SWP Sheet 20. Figure 5 (below). SWP Sheets 19–20: Regions from Beth Guvrin to Ashkelon and Gaza. Ashkelon is at the top-left of the map and Gaza at the lower-left. Both figures courtesy of Todd Bolen, BiblePlaces.com.

40 NEAR EASTERN ARCHAEOLOGY 75:1 (2012)

(fig. 6). This runoff activity has cut away portions of occupational levels on the eastern shoulder of the site (Squares O18-O19-O20; see fig. 7). Remains as early as the eighth and ninth centuries b.c.e. sur-vive intact only in the western half of those squares, while the deeper, tenth-century levels are preserved across the entire breadth of the excavation area and at least 2–3 m farther east. Figures 8–9 show the ero-sion line around the eastern and southeastern edges of the mound, and the slicing away of eighth- and late ninth-century levels is clearly visible in all the relevant latitudinal baulks (figs. 10–11). Hence an understanding of nature’s impact on the site since the artificial cutting of the eastern slope is clearly a prerequisite to any analysis of the tell’s depositional history.

The Regional Physical Setting: Tel Zayit in Situ

Whatever the original size of ancient Tel Zayit, one must recognize the site’s location—along the fluid border between Judah and Philistia—as the principal contributing factor to its political and cultural signifi-cance. Thus a close look at Tel Zayit’s broader regional setting, with its varied topographical features, consti-tutes a second requirement for proper appreciation of the site’s extended history. For studying ancient settlement patterns of borderland towns, one can

hardly imagine a better topo-geographical arrangement than the southern highlands, lowlands, and coastal plains of biblical Judah and Philistia, where multiple east-west valley systems spawned ancient roadways that connected the various areas.

From Jerusalem south, six transverse valleys or basins descend from the hill country to the inner coastal plain (see fig. 3 above). Besides the Nahal Sorek-Refa‘im system (Nahar Rubin), which bisects the hills immediately west of Jerusa-lem, the Nahal HaElah (Wâdī es-Sunt), Nahal Guvrin (Val-ley of Zephatha or Wâdī el-Museijid), Nahal Lachish (Wâdī Qubeibeh), Nahal Shiqma-Adorayim (Wâdī el-Hesi), and Nahal Besor-Gerar (Wâdī Ghazzeh) accommodate the runoff on the seaward slopes of the Judean highlands as far south as the Beersheba Basin. Once the network of capillary streams in each natural regime leaves the inland areas and reaches the inner coastal plain, the principal tributaries merge into single, independent outlets (shown in italics in the previous list) before proceeding to the shoreline and emptying into the Mediterranean Sea. For example, the Shiqma and Adorayim branches of the Wâdī el-Hesi approach the coast as one trunk

Figure 6. Area T: Step-Trench down the Steep Eastern Slope of the Mound (tilted toward the northeast). Photograph by Ron E. Tappy.

Figure 7. Tel Zayit site plan. Squares O18-O19-O20 can be seen in the lower right quarter of the plan, on the eastern shoulder of the site.

NEAR EASTERN ARCHAEOLOGY 75:1 (2012) 41

channel approximately 7.5 km south of Ashkelon, and the Wâdī Ghazzeh outlet for the confluence of the Besor-Gerar streams lies even farther to the south. Similarly, the three streams from the HaElah, Guvrin, and Lachish valleys converge sequentially in the Wâdī Suqreir before reaching the shore approximately 22 km north of Ashkelon.3

Regional survey data have also shown that the three prin-cipal east-west routes linking the coastal centers with the interior hill country exploited the natural landscape of the HaElah-Guvrin-Lachish systems just mentioned (Dorsey 1991, 182 map 13, 194 map 14). In the northerly Nahal HaElah, a road connected the port center at Ashkelon with Tell es-S âfi and proceeded past Azekah before forking, with one branch leading up to the Judahite highlands between Bethlehem and Jerusalem while the other turnoff ran to the northeast and led toward the Ramah-Mizpah area, north of Jerusalem. To the south, in Nahal Lachish, another route from Ashkelon split at Tell el-‘Areini on the inner coastal plain and continued through the valley both to Lachish and Mareshah (Tell S andahannah, farther east through the Nahal Mareshah) and then into the hill country, with the Lachish branch pass-ing through Khirbet el-Qom and Adorayim before reaching the Jutta-Ziph area south of Hebron.

Tel Zayit lay at the western entrance to the central valley,

Nahal Guvrin. Only a short distance (ca. 7 km) separated Lachish and Tel Zayit and the two valleys to which they belong. The road through the Guvrin Valley advanced almost due east from Ashkelon and passed by Tel Zayit, Tell Bûrnah, Tell Judeidah (modern Tel Goded = ancient Moresheth-Gath, home of the prophet Micah), and both Adullam and Khirbet el-Beida as it ascended to Khirbet Jedur (biblical Gedor) and Beth-zur south of Bethlehem. Here it connected with the main north-south passageway stretching along the watershed ridge between Jerusalem and Hebron.

In addition to these three east-west routes, at least three longitudinal roadways served the lowlands of Judah and, in fact, converged somewhere near Tel Zayit in the Iron Age (Dorsey 1991, 58, map 1; 67–70; also 182, map 13; 189–92, 196; and 194 map 14). Three millennia later, even the late nineteenth-century village at Zeitah lay at the juncture of at least seven regional roadways (fig. 12) and thereby distin-guished itself from nearby Tell Bûrnah. Running east of and parallel to the main coastal highway that connected Egypt and the northern Sinai Peninsula with the southernmost Philistine capital at Gaza, the three Iron Age byways passed through the important centers of Tell Jemma (likely ancient Yurza) and Tell el-Far‘ah (S)—major sites that, together with Tell Haror and other mostly unidentified towns, protected the southern

Figure 9 ( r ight ) . Eastern shoulder of the mound, with erosion . Photograph by Sky View Photography.

F i g u re 8 ( l e f t ) . A e r i a l View of Area T Trench. Photograph by Sky View Photography.

42 NEAR EASTERN ARCHAEOLOGY 75:1 (2012)

accesses around Philistia and into Judah and established the Besor Basin area as a natural border (Dorsey 1991, 67–70). As these routes continued northward, they entered the lower Shephelah and actually began to merge north of the Tell el-Hesi–Lachish line before con-tinuing as a single highway to urban centers at Tell es-Sâfi (Philistine Gath) and Tel Miqne (Philistine Ekron).4

When considering the network of roads and highways through the Elah, Guvrin, and Lachish valleys, a picture emerges that seems quite consistent with the topography and archaeological his-tory of these regions and that correlates well with the outline given in Joshua 15:33–44 of the districts and cities belonging to Judah. From verse 33 through the first site listed in verse 35 (Jarmuth), the roster names eight sites in the Sorek and related valleys before moving to the Nahal HaElah, for which it lists seven sites, though an eighth town, Beth-shemesh, may somehow have dropped from the lineup (Rainey 1983, 7). In the heart of the Shephelah or “lowlands” area, the settlements fall into three geographical groups that follow roughly the Elah (15:35–36 = District 2), Lachish (15:37–41 = District 3), and Guvrin (15:42–44 = District 4) systems.5 The list appears to identify each physical environment by naming its princi-pal (and, in the case of District 4, westernmost) municipal-ity together with some of its satellite sites. Since the town of Libnah introduces the Guvrin group in District 4, one may reasonably refer to this area as the “Libnah District,” just as the next valley to the south became the “Lachish District.”

The overall roster of Elah, Guvrin/Libnah, and Lachish sites includes seven of the eight cities listed elsewhere as consti-tuting the western edge of Rehoboam’s defensive network of fortresses (Lachish [in District 3]; Mareshah [District 4]; Adul-lam, Socoh, Azekah, Zorah [all in District 2]; and, just north

of District 2, Aijalon). The Joshua 15 catalogue omits only Moresheth-Gath from the Libnah District 4 (see 2 Chr 11:5–12 and the discussion in Aharoni 1979, 330–33 and map 25). In District 4, two towns—Libnah and Ether—lay west of this line of forts (in the general area of Tel Zayit and Tell Bûrnah). One should not infer, however, that these areas lay outside Judah’s power. If, as seems likely, Rehoboam’s action occurred as a response to Shishak’s maneuvers, the line of Judahite sway in the Shephelah must have contracted eastward in the wake of the Egyptian incursion. The fact that sometime in the early ninth century Judah reportedly halted another charge by the enigmatic Ethiopian Zerah and pursued his army as far as Gerar (Tell Haror) indicates the kingdom’s comfort at mov-ing west of its established border and into the liminal zone that extended out to Tel Batash, Tel Zayit, Tell-el Hesi, Tell esh-Shari‘ah (probably biblical Ziklag), and Tel Haror. The last site (Tell Abu Hureireh) likely marked the transition from the southwestern corner of Philistia proper to the western Negev (see Stager 1995, 342–43, who even suggests Haror versus Tell es-Sâfi as Philistine Gath). In like manner, Judah’s two most westerly Levitical cities, Beth-shemesh and Libnah (Josh 21; 1 Chr 6:54–81 [MT 6:39–66]), were situated in the frontier of Districts 2 and 4, respectively. It seems reasonable to conclude,

Figure 10 (left). Square O19: Northeastern baulk. Photograph by Ron E. Tappy.

Figure 11 (below). Squares O19–20: Northern baulks with continuous eighth-century destruction level. Photograph by Ron E. Tappy.

NEAR EASTERN ARCHAEOLOGY 75:1 (2012) 43

then, that the Shishak raid wrested from Judah significant influence over the lower Shephelah region around Tell Bûrnah and Tel Zayit. A similar loss of this vulnerable zone recurred at the hands of Sennacherib in 701 b.c.e.

Since Tel Zayit represents a site in the westerly Guvrin Val-ley that has shown clear affinities with highland culture in certain periods and coastal culture in other periods, and since it lies roughly halfway between Philistine Gath to the north and Judahite Lachish to the south, it seems that the town faced a borderland area in every direction. Tel Zayit’s location at the mouth of Nahal Guvrin placed it squarely at a topo-graphical and cultural (in the broadest sense of that word) interface that afforded certain advantages. But it also situated the inhabitants in a somewhat complicated position, for their home lay betwixt and between at least two competing political and social cores: Judah to the east and Philistia to the west. Along with certain other sites (such as Tell el-Hesi and Tell el-‘Areini to the south, Tel Batash-Timnah and even, in cer-tain ways, Tell es-S âfi-Gath to the north), Tel Zayit lay in the liminal zone that straddled the cultural boundaries of both of these polities.

Life in the Borderlands: Taking the Long ViewAs the centuries passed after Sennacherib’s devastating

assault against the region in 701 b.c.e., Tel Zayit continued to live out its life in the liminal zone between larger cultural spheres. Following its occupation in the Persian and Helle-nistic periods, the town experienced at least three phases of building during the Early Roman era. Then, in the Late Roman

period, a substantial fortress commanded a view from the summit (figs. 13–14). As a detailed but highly schematized presentation perhaps based on the cursus publicus (the roads and staging posts of the Roman postal system),6 the Tabula Peutingeriana (an illustrated itinerarium copied during medi-eval times from a second- or third-century c.e. Roman fore-runner) confirms the strategic value in this period of the bor-derlands around Tel Zayit.

The Tabula Peutingeriana and the Outskirts of Iudaea-Palaestina

Considering the odd size of the TP (33 x 672 cm, or roughly 13 inches high by 22 feet in length),7 it seems likely that the original—a composite of a number of related maps—served as a display piece somewhere in Rome sometime before 300 c.e.8 The map offered an impressive, public exhibition of terrestrial routes that stitched together the imperium Romanum, that immense portion of the inhabited world which Rome domi-nated, from the Atlantic Ocean to India.9 As such, this display functioned as much more than a utilitarian map for travelers, couriers, and military officers (Talbert 2010, 142–57).10

To include the entire orbis Romanus (in Ptolemy’s words, “that part of the earth which is inhabited by us,” Geographia 5.5.2) in a work of such short height, the mapmaker had to make serious concessions (for a full discussion of the shape and scope of the map, see Talbert 2010, 87–95). He often sac-rificed desired attributes such as longitudinal depth, proper compass orientation, precision with regard to meridians and parallels, and nautical and terrestrial accuracy via a uniform

Figure 12. SWP Sheet 20: Nahal Guvrin from Beth Guvrin to Tel Zayit (Zeita) to el Fâlûjeh (modern-day Pelugot Junc-tion). Courtesy of Todd Bolen, BiblePlaces.com.

44 NEAR EASTERN ARCHAEOLOGY 75:1 (2012)

scale, while allowing here and there for strange juxtapositions and the separation of mutually relative points. Discrimina-tory choices had to attend even the selection of places and features to represent. Italy appears stretched to a dispropor-

tionately large size (over 2 m.) and lies horizontally between two exceedingly thin strips of water depicting the Mediterra-nean and Adriatic Seas (fig. 15)—perhaps to grant the country and its capital a more central position within the map’s long span. Consequently, other locales to the east (e.g., the Rhine and Danube frontiers) suffered dramatic compression. The depiction of Greece endured so much shrinkage that the pan-

Figure 15. Tabula Peutingeriana: Italy and Rome. This nineteenth-century copy is presented here because the more vibrant and consistent color greatly enhances reading.

Figure 13 (left). Square K20: Levels exposed from the Persian period through Late Roman period. Photograph by Sky View Photography.

Figure 14 (right). Aerial views toward the coastal plain (Ashkelon) from Tel Zayit. Photograph by Sky View Photography.

NEAR EASTERN ARCHAEOLOGY 75:1 (2012) 45

Hellenic precinct at Delphi is omitted entirely. Thrace appears below rather than west of the Black Sea, itself portrayed only as a narrow, horizontal channel. The western and southern coasts of Anatolia/Asia Minor are drawn as one and the same, with the latter running to roughly half the length of the former (Tal-bert 2010, 91–93); together they delineate the northern limits of the eastern Mediterranean Sea. South of Thrace, the Great Sea widens slightly to allow for oversized representations of Crete and, farther east, Cyprus.

The mapmaker featured the fan of the Nile Delta (from Alex-andria—identified only by its famous Pharos lighthouse and not by name—eastward to the Pelusiac Branch) and Antioch as the most prominent places in the eastern Mediterranean region (fig. 16). (Even though Constantinople appears on this map, the more impressive depiction of Antioch [see figs. 17a–c] may recall an earlier time when that locale represented the leading eastern city; see Matthews 2006, 72, 77–88; Dilke 1985, 116; also n. 8 above and n. 12 below; in any event, Talbert [2010, 124] understands the exceptional depiction of Antioch as a copyist’s later addition.) On the distorted map, however, the Delta lies not toward the eastern end of the Mediterranean but well out along its southern coast. The spatial allowance for Cyprus necessarily pushed Palestine and Sinai, along with the Delta, far to the west—so much so that the Dead Sea, Sinai Peninsula, and Egyptian Delta lie west of Rhodes, and, still farther west, Carthage sits almost directly south of Rome—just across a very narrow Mediterranean Sea.

Features on the northern and southern sides of the Mediter-ranean are oriented in opposite directions. Whereas horizontal Italy lies with its north to the left and its southern boot heel to the right, the Nile appears as though flowing horizontally from left (south) to right (northern Delta). Similarly, Pales-tine—also positioned below the Mediterranean—shows the Dead Sea (south) on the left and the Sea of Galilee (north) on the right. Moreover, the stretch from the Egyptian Delta through Palestine to Antioch falsely appears to have consti-tuted the easternmost portion of the Mediterranean’s southern coastline versus the eastern Mediterranean littoral. Antioch

is situated far to the right of both Damascus and the Sea of Galilee. Beyond Antioch the level of detail declines sharply, although at least nine parallel desert routes run to the right (i.e., eastward) from Damascus-Antioch to Palmyra and on to the civil metropolis at Samosata (one-time home of the Legio VI Ferrata; see below) on the western bank of the Euphrates. From there, the compression and resultant distortion become even more pronounced.

Given the striking economy of vertical space and the dra-matic compression of the entire Mediterranean basin, rela-tively small Palestine (fig. 16) on the eastern littoral might easily have received only cursory attention. But by the time the Roman cartographer made his map, the province of Syria-Palaestina (formerly Iudaea) had garnered significant, albeit negative, attention within Rome’s imperial system. Between the period of provincial prefects and procurators (ca. 6–70 c.e.) and the relatively peaceful but internally unstable Severan Dynasty (193–235 c.e.), at least five major historical cycles necessitated the development of an impressive road network in Palestine. These watershed events include: (1) the suppression of the First Jewish Revolt (66–70 c.e.); (2) Trajan’s (98–117 c.e.) establishment of the Provincia Arabia (106 c.e.); (3) the so-called Kitos War (115–117 c.e.), which started during the Parthian War in Mesopotamia but spread through Cyrenaica, Egypt, Cyprus, and into Palestine before Lusius Quietus dealt a decisive blow to Jewish rebels in Lydda; (4) Hadrian’s personal tour of Judea (130 c.e.), when he rebuilt Jerusalem as Aelia Capitolina, prohibited Jewish citizens from entering the city, and issued decrees outlawing other Jewish practices; and, ulti-mately, (5) the Bar Kokhba Revolt (132–135 c.e.). Thus politi-cal and military affairs that unfolded over a sixty-year period and that focused on troubles in the greater eastern Mediterra-nean prompted the evolution in Palestine of a well-developed and maintained system of roads, caravanserai, water facilities, guard posts, milestones, and so forth, by which the Romans both met their need for access and control and publicized their symbols of power (a goal admirably abetted by the milestones themselves; see Roll 1983, 153). Not coincidentally, this period

46 NEAR EASTERN ARCHAEOLOGY 75:1 (2012)

represents the floruit of Roman mapmaking and, judging from the surviving exemplars, cartography from the late empire on reflects somewhat of a decline in standards (Dilke 1985, 167).

Perhaps more than any other single factor, the Bar Kokhba rebellion forced the Romans to expand their already extensive presence in Palaestina. Even after the First Revolt, the Roman army had increased its size by sixty thousand soldiers and established bases at Caesarea, Ptolemais/Acco, Scythopolis, Emmaus, Jericho, and Gophna (Josephus, War 3.64; 4.440, 550–555; 5.40–42, 50–53, 67–70). Vespasian then scattered throughout this framework centurions in smaller cities and decurions in villages (4.442). Later, when Trajan established the Provincia Arabia in Transjordan (the former Nabataean kingdom) in 106 c.e., highways from the Mediterranean through Palestine gained even greater strategic value. But, with renewed trouble in Galilee early in the rule of Hadrian (117–138 c.e.), a new legion arrived at Kfar Otnay, near Megiddo. Further, Bar Kokhba’s selection of Betar (Khirbet el Yahud, near Battir; see Tsafrir et al. 1994, 86), on the southwestern border of the municipal territory belonging to Jerusalem (in the direction of Nahal Guvrin/Tel Zayit but still east of Chesa-lon and the Eshtaol–Jarmuth–Enadab line; Rainey and Notley 2006, 12), as his principal stronghold drew Roman attention to this area. By the early Severan period (199/200 c.e.), the city at Beth Guvrin/Beit Jibrîn received the new name Eleuthero-polis and became the most important center in the foothills of Judah. That the TP mapmaker already knew Jerusalem as Aelia Capitolina (the name that appears on the TP along with the notation “previously called Jerusalem”) but Eleutheropolis only as Betogabri suggests that he created his map before the close of the second century c.e. (see below). During this time, both demographic and economic growth in Palestine became possible largely because of the emerging, far-reaching network of Roman roads and highways, which collectively ran to nearly 1,000 Roman miles (ca. 1,500 km; Roll 1983, 136–37) and linked all the major cities and towns throughout the region.

Rather than treating Palestine as an insignificant part of the eastern empire, then, the creator of the TP acknowl-edged the area’s accrued status by providing consid-

erable and significant detail for towns and itineraries in the region. The principal north-south roads include (see fig. 18): (1) a coastal route, extending from the Egyptian Delta across northern Sinai and through Philistia (Ashkelon), Jaffa, Caesarea, and Ptolemais/Acco before proceeding northward through Tyre and Byblos en route to Antioch; and (2) a Jordan River Valley route, from Tiberias through Scythopolis to Jeri-cho, the capital of the Jordon Valley district and an episcopal see beginning in the fourth century. In the lowlands between the coast and the highlands, the mapmaker recognized three important cities that lay east of the primary coastal artery: Luddis (Lydda), Amavante (Emmaus), and Betogabri (Beth Guvrin, Ptolemy’s βαιτογάβρα), from north to south. Dur-ing the Severan rule (193–235 c.e.), these locations became Roman centers and received the names Diospolis, Nicopolis, and Eleutheropolis, respectively. As he did with Betogabri, the mapmaker identified Diospolis and Nicopolis only by their older names (as had Ptolemy in his earlier Geographia 5.16.5–7). By the early third century c.e., on the other hand, the non-pictorial Itinerarium Antonini already employed the name “Diospolis” for Lydda and “Eleuteropoli” for Beth Guvrin (Cuntz 1990, 21, 150.3; 27, 199.3).11 In addition, while the TP cartographer drew a road between Lydda and Emmaus, he did not indicate its continuation along the borderlands to Beth Guvrin via the two Gaths, that is, the old Danite town of Gath-rimmon/Gittaim (twelve miles south of Lydda; Eusebius, Onom. 70.14–16, 71.15–17) and the larger center at Philistine Gath (ca. 5 five miles before reaching Eleutheropolis; Onom. 68.4–7; see Rainey and Notley 2006, 154–55). Collectively, these facts provide further clues to the pre-Severan date of the original map, and Roll (1983, 144) has observed that the road network presented here resembles closely the distribution of milestones dating to the year 162 c.e. That said, a clear date for the production of the original map remains impossible to determine.12 Broadly, the net result from numerous studies allows for the map’s creation sometime between the reigns of

Figure 16. Tabula Peutingeriana: Nile Delta to Antioch.

NEAR EASTERN ARCHAEOLOGY 75:1 (2012) 47

Hadrian and Constantine, that is, from the mid-second century to the begin-ning of the fourth century c.e. (see nn. 8 and 12).

Although at least nine major latitu-dinal routes traversed Palestine by the third century c.e. (Roll 1983, 145), the TP appears—at first glance (but see below)—to show only four thorough-fares in the area between the Sea of Galilee and the Dead Sea. Three of the map’s roadways cross the northern and central portions of the region, while only one passes through the Judean Shephelah. In the north, a road ran from Scythopolis through Capercot-nei (Kefar ‘Otnay) and then southwest-ward to Caesarea, a total distance of approximately 50 miles (the TP records 24 + 28 = 52 Roman miles). Following the Bar Kokhba Revolt, when a new Roman legion—the Legio VI Ferrata, or “Ironsides”—encamped at Caper-cotnei on the western border of the Jezreel Valley near Megiddo, the town became known simply as Legio.13 But while the principal mission of Legio VI Ferrata entailed pacifying and holding the Esdraelon area, detachments from it also apparently assisted in construc-tion activities in the Guvrin Valley, as suggested by the discovery near Eleu-theropolis of a building inscription in the form of tabula ansata (Iliffe 1933, 121–22).

In central Palaestina, another road connected Jerusalem/Aelia Capitolina to Caesarea by starting north and pass-ing through Gophna, the head of the second-most important toparchy in Judea (Josephus, War 3.55), and then Neapolis (modern Nablus), a town established by Vespasian in 72 c.e. just 2 km west of biblical Shechem. As this route descended the seaward slopes of the Ephraimite hills, it likely also accommodated traffic to and from Samaria-Sebaste, which the car-tographer omitted. At Gophna, judg-ing from the TP, an alternative route turned westward and ran to Nicopolis (= Emmaus, identified on this map as Amavante) and on to Lydda, but not as far as coastal Jaffa. However, this line and the mileage figures associated with

it likely represent a conflation of two distinct routes from Jerusalem to the central coast. One road ran directly from Jerusalem to Emmaus and then on to Lydda, thereby avoiding the Gophna Hills. The TP preserves the mileage for this trip and its association with Emmaus but not the actual line of the road itself. The line that the map-maker drew from Gophna to Lydda belongs, instead, to another road that descended from Gophna and passed through Thamna (Khirbet Tibneh), a large fourth-century village in the Lydda district, on its way to Antipa-tris (Aphek) in the Sharon Plain (see Isaac and Roll 1982, 120, fig. 3; for a study of all the roads linking Jerusa-lem–Lydda–Jaffa in Roman-Byzantine times, see Fischer et al. 1996). Thus the information preserved on this map conflates two separate routings: Jerusalem–Emmaus–Lydda and Jeru-salem–Gophna–Thamna–Antipatris (Finkelstein 1979, 32). The error may have resulted from the fact that the for-mer road also proceeded from Lydda to Antipatris, which does not appear on the TP but which lay roughly half-way along the line from Lydda to Cae-sarea. (Antipatris does appear in Ptol-emy’s Geographia, though it is offset too far east of Lydda.) The discovery of milestones in 1953 and 1970 con-firmed that, from a point just north of Antipatris, at Qalansawa on the Antipatris-Caesarea territorial bor-der, the Romans negotiated their way through the Mousterian sands, kurkarridges, and swampy depressions along the Sharon Plain and constructed a direct route from Antipatris to Cae-sarea. On the TP, the northern half of the Lydda–Ceasarea route likely rep-resents this road (Dar and Applebaum 1973, 98, fig. 4).

Finally, in the south the mapmaker included only one major road that linked Jerusalem to Beth Guvrin via Ceperaria, a road station situated circa 24 miles southwest of Jerusalem (somewhere between Tell Zakariya [Azekah] and Keilah [1 Sam 23:1–13]) and around 8 miles before Beth Guvrin (Avi-Yonah 1976, 47; Tsafrir

Figures 17a–c. Tabula Peutingeriana: Patron goddesses associated with Rome (top), Con-stantinople (middle), and Antioch (bottom). Copyright Österreichische Nationalbiblio-thek. Photos courtesy of Richard J. A. Talbert.

48 NEAR EASTERN ARCHAEOLOGY 75:1 (2012)

et al. 1994, 102; Keilah lay approximately 8 miles east of Beth Guvrin and on the way to Hebron; Eusebius, Onom. 114.16). The author marked the southward transition from the Elah Valley to the Nahal Guvrin by inserting a series of angles in the stretch of road between Ceperaria and Beth Guvrin.

From just north of Beth Guvrin, the route proceeded more or less directly to Ashkelon, which—due to the compression of the map necessitated by its odd shape—appears much farther south than the Dead Sea. The total distance from Jerusalem to Ashkelon, recorded in Roman miles, appears in three units: 24 miles from Jerusalem to Ceperaria, 8 miles from Ceperaria to Betogabri, and 16 miles from Betogabri to Ashkelon, for a total of 48 miles. Tel Zayit lies 26.96 km (16.75 miles) east of Ash-kelon, and Tell Bûrnah another 4.08 km farther east (or 31.04 km = 19.29 miles from Ashkelon). Beth Guvrin, on the other hand, sits at least 33.11 km, or 20.57 miles, east of Ashkelon; in fact, the Antonine Itinerary (which probably originated some-where near the beginning of the third century c.e.) places Ash-kelon 24 miles from Beth Guvrin (see Robinson 1856, 59). So while the distances preserved in the TP make relative sense,14 it is plausible that, due to space constraints on the map between Beth Guvrin and Ashkelon, the mapmaker, or possibly a later editor, omitted the name of an intervening site (probably Lib-nah), in much the same manner that he deleted Antipatris

north of Lydda but retained the original mileage count.In any event, the creator of the TP turned Palestine side-

ways, with north lying to the right, causing the lateral routes to assume a vertical orientation on the map. Although the map’s dimensions allowed precious little height for drawing long vertical lines, the lateral roadways across relatively nar-row Palestine comprised short stretches whose lengths would not have deterred the cartographer from including multiple roads. Similarly, while the mapmaker generally omitted routes that ran down long, pronounced slopes (Talbert 2010, 99), the valley roads leading down the seaward decline of the Judean hills were not all that steep and so did not inherently disqualify themselves from inclusion in the local gazetteer.

With these facts in mind, it seems all the more significant that the Jerusalem–Ceperaria–Beth Guvrin–(Libnah)–Ashkelon passageway represents the single latitudinal route depicted in the area south of Jerusalem. The two terminus towns, Jerusa-lem and Ashkelon, both appear on the map with a pictorial symbol, or vignette: a pair of twin towers with a first-story door and a window in the gabled roof (see fig. 18). Nearly 78 percent (434 of 559) of all symbols utilized by the mapmaker represent some variation of this design (Talbert 2010, 118–19), and of the seven types of symbols that appear on the map (see Levi and Levi 1967, 65–66, 195–211, 225–32), this one seems to have

Figure 18. Tabula Peutingeriana: Palestine. Here and in fig. 17 photographs of the original map show the impact of fading and lack of contrast that has developed over the centuries. Copyright Österreichische Nationalbibliothek. Photo courtesy of Richard J. A. Talbert.

NEAR EASTERN ARCHAEOLOGY 75:1 (2012) 49

indicated “places of administra-tive, commercial, military, or other well-known importance” (Talbert 2010, 121). Significantly, of the ten cities claiming some variant of this vignette in Cis-Jordan (from Tyre to Ashkelon), only Jerusalem and Ashkelon display an image in southern Palaestina (moreover, an identi-cal image [Levi and Levi’s Type A.II.1] that distinguishes these two cities from all others in the region). Even the regional hub at Beth Guvrin appears without an icon of any kind,15 a fact that should raise no surprise if the original map predates the pro-motion of Bethogabri to Eleu-theropolis around 200 c.e.

Tel Zayit in Service to the Romans as a Fortified Out-post

As noted above, by the early fourth century c.e. Bishop Euse-bius of Caesarea (Onomasticon) selected Eleutheropolis (Beit Jibrîn/Beth Guvrin) as the piv-otal reference point from which to gauge distances and locate towns throughout the general region. The descent from Jeru-salem/Aelia Capitolina to Beth Guvrin undoubtedly still began by following longstanding routes through the Elah Valley, and the most direct approach to Ash-kelon from Beth Guvrin contin-ued to pass through the Tell Bûrnah–Tel Zayit area, that is, through the former Libnah/Guvrin District 4 of Joshua 15 (see figs. 3–5; Tsafrir et al. 1994, v map 2; Roll 1983, 139; Fischer et al. 1996, 4, fig. 1). Since Tel Zayit represented the last (i.e., westernmost) town in the Nahal Guvrin and lay squarely at the topographical transition from Shephelah to coastal plain, it would have provided the first point of protection against any unwanted incursion from the coast. It is not surprising, then, that excavation of the site has exposed what appears to be a large Late Roman fortress on the summit of the tell. Pre-liminary analysis of the latest pottery recovered from beneath the principal floors of this stronghold suggests a construction date in the late second or early third century c.e., that is, cer-tainly after the Bar Kokhba rebellion and perhaps not until the rise of Eleutheropolis as a Christian bishopric and regional center (by the Council of Nicaea in 325 c.e.). Interestingly,

the largest group of milestones surviving in Israel dates from the beginning of Marcus Aure-lius’s rule (161–180 c.e.), a fact that identifies these years as one of the most significant periods of Roman road building and repair in Palaestina.16

The imposing fortress at Tel Zayit clearly dominated the entire western portion of the summit (fig. 19), which rose slightly higher than the east-ern half and commanded a coastal view that ranged from Ashdod to Gaza. The build-ing’s thick walls, which became visible only 15 cm beneath the surface of the tell, included a wide entryway into the fortress from the northwest, the area of the lower settlement. Two mas-sive stone piers (2.20 m x 9.40 m) defined the northern and southern sides of the gateway, and the street running between them measured 5.1 m in width. Portions of at least three steps that led up to the gate have survived. The uppermost step offered a relatively broad (1.7 m) landing immediately west of the entrance; it ran from outer edge to outer edge of the two piers, a distance of 9.6 m. A row of large, dressed stones framed the western edge of the step, while the walking surface itself consisted of substantial quanti-

ties of small stones (ca. 10 cm in diameter) set with a mortar of light grey, lime plaster.

Segments of two of the building’s principal enclosure walls appeared in the southwestern quadrant of Square K20 (fig. 20). The full width of these features remains uncertain, however, since both walls extend into baulks. Yet, given the striking scale of the architectural elements thus far revealed, the fortress likely covered a substantial portion of the western summit area during its serviceable life; it must certainly have constituted the dominant feature at the site in this period. Both the scale of the building and the strategic location of the site confirm that the town served as more than a mere guard post with watch tower. Rather, it represented a substantially fortified stronghold situ-ated at a topographical and cultural interface, with a constant water source and unfettered surveillance of all traffic passing through this borderland area. The fortress’s position on the

Figure 19 (above). Western Summit, Squares J21 and K20: Late Roman building and entryway; view toward east. Photograph by W. Simco.

Figure 20 (below). Square K20: Late Roman building. Photograph by W. Simco.

50 NEAR EASTERN ARCHAEOLOGY 75:1 (2012)

western shoulder of Tel Zayit and the western orientation of its primary entryway allowed the occupants to guard against any encroachment from the southern coastal plain.

One of the building’s primary walls ran from the southern pier and in a southwesterly direction for 4.9 m before forming an inside corner with another wall. Both walls again displayed a construction technique (boulder frame with cobble-plas-ter core) consistent with the piers and steps of the gateway. Assuming that a similar design existed beyond the northern pier (an area now mostly eroded away), the interior width of this westerly room would have measured 19.3 m. Many of the original surfaces inside both the gate and the building suffered total destruction from later intrusions, especially across the entire southern half of the square (fig. 20). In the northeast-ern quadrant of K20, however, at least two intact phases of thick (> 20 cm) plaster flooring survived and lapped up to the entryway’s southern pier, confirming their coexistence. The main surface consisted of crushed yellow limestone gravel laid above a 25-cm-thick bed of brown, bricky soil. A stone-lined, bell-shaped well cut through the southerly extension of this surface, and, farther to the east, a portion of a stone-capped, plaster-lined drain survived (fig. 21; for general location, see fig. 13). This channel drained toward the north and either siphoned water to a cistern lying beyond the current excava-tion area or turned westward to conduct water out through the center of the entryway (similar to the much earlier gateway drain at Gezer).

The stratum containing this fortress overlay multiphased levels from the Persian, Hellenistic, and Early Roman peri-ods (fig. 13). A swath of cobblestone floor running diago-nally through the center of the area represented the dominant feature from the Early Roman period. Noticeably, the entire southern extension of this floor is missing and seems to have been intentionally cut off along its current southern edge. The floor’s cobbles, likely looted during the construction of the

Late Roman fortress, became part of the small stone and plaster core found inside the much larger architecture of that build-ing. Moreover, virtually all the fills associ-ated with this fortress (and with all levels from the Persian period on), yielded a sig-nificant quantity of small-sized pottery fragments from the Iron Age. In addition, certain features—such as cup marks, Iron Age chisel marks, and occasional mar-gins around the edges of several blocks with central bosses—occur erratically

across the Late Roman architecture and support the view that these blocks lie in secondary use. It seems that a succession of ancient builders dismantled earlier, Iron Age structures that were themselves very large and impressive public buildings, judging from the size of the reused materials, and pressed the stones of these erstwhile structures into secondary usage. This process naturally churned up much Iron II pottery, which then became part of the later fills.

That Roman-period loci in other excavation areas on the summit yielded stone-cut drinking vessels (fig. 22), valued for purposes of purity (John 2:6), suggests the presence of a religious Jewish community at Tel Zayit in the period leading up to or during the life of this fortress. Following Hadrian’s transformation of Jerusalem to Aelia Capitolina and his ban-ning of Jews from entering the city in 132 c.e., the number of devout Jewish citizens likely increased in outlying areas such as Nahal Guvrin. (Eusebius reports further that Hadrian disal-lowed Jews “from even entering the country about Jerusalem” [Hist. eccl. 4.6].) By the Mishnaic period (ca. 200 c.e.), nearby synagogues existed to the east at Beth Guvrin and Hirbet Midras (Drusias; Ptolemy, Geographia 5.15.5) and to the west at Buriron (Tel Berôr) and Ashkelon (Tsafrir et al. 1994, map 4). By the fourth century c.e., Eleutheropolis also became an episcopal see, and churches or monasteries appeared at Qera-tye (Conder and Kitchener 1998, 278) and ‘Ozem (at Khirbet Beth-M’amim; Cohen 1975, 310), both of which lay in the inner coastal plain just to the west of the Tel Zayit–Lachish area (Tsafrir et al. 1994, map 5). Recently, salvage excavations have uncovered a slightly later basilica on the hillside south of Moshav Tsafririm, just east of Tel Zayit. At least from the late second century on, then, the entire area around Tel Zayit/Nahal Guvrin became quite active in religious affairs and, even in this regard, epitomized a kind of liminal zone that included both Jewish and Christian practitioners.

Thus the Jerusalem–Beth Guvrin–Libnah–Ashkelon route

Figure 21. Stone-capped drain from the Roman period. Photograph by Ron E. Tappy.

NEAR EASTERN ARCHAEOLOGY 75:1 (2012) 51

clearly held strategic value within the imperium Romanum and, consequently, came within the purview of mapmakers in Rome. By the end of the third century c.e., the Romans had divided all of Palestine into a network of municipal areas (Avi-Yonah 2002, 127, 154–55). But already at the turn of the cen-tury (200 c.e.), Septimius Severus established city territories around Diospolis (Lydda) and Eleutheropolis (Betogabris), and by the close of the first quarter of the new era the youth-ful Elagabalus (also known as Heliogabalus) did the same at Nicopolis (Emmaus). Subsequently, but probably before 200 c.e., the maker of the TP traced major routes from Jerusalem specifically through these three emergent territories. When Septimius Severus transformed Beth Guvrin into the munici-pality of Eleutheropolis in 200 c.e., he likely visited the city (and perhaps passed through the Nahal Guvrin corridor) dur-ing his travels to Egypt around that same time. Roman coinage struck with the inscription Lucia Septima Severiana Eleuthero-polis reflects his favorable attitude toward the city, which may have responded by erecting a limestone statue of the emperor in military dress (Clermont-Ganneau 1896, 441–42, 464). In any event, he placed a staggering expanse of land under Beth Guvrin’s jurisdiction. Not only did its territory take in the area west of Aelia Capitolina’s domain and down through the entire Shephelah, but also the region to the south (known as Daromas) that extended all the way to the oasis of Engaddi (‘En-Gedi) at the Dead Sea. Since Tel Zayit lay between the sites of Agla (Khirbet ‘Ajlân, positioned 10 Roman miles from Eleutheropolis toward Gaza; Eusebius, Onom. 48.18–19) and the old Philistine center at Geth (Tell es-Sâfi/Gath; compare Avi-Yonah 2002: 160, map 16; and Rainey and Notley 2006, 128), the new districting clearly affiliated it with the regional center at Beth Guvrin.

Throughout the centuries, the road that left the coast, passed by Tel Zayit, and continued on from Eleutheropolis to Jeru-salem remained a principal artery of military activity, com-mercial exchange, and religious pilgrimage. Repairs made to the road during the early Umayyad period, probably during the reign of Abd al-Malik (685–705 c.e.), bear witness to its enduring value.

Tel Zayit’s Political Compass during the Turkish-Ottoman and British-Mandate Periods

At the close of the sixteenth century c.e., the 165 residents of the small qarya (a permanently settled “village”) known as Khirbat Zayta al-Kharab continued to experience life in a lim-inal zone between the highlands and the coastal plain. In 1596 c.e., the community included social units belonging to thirty hāna (Muslim households of approximately five people, with adult, married men acting as family heads) and/or mujarrad (Muslim households represented by single, adult men; Hüt-teroth and Abdulfattah 1977, 19, 36, 43, 147). While Damascus ultimately presided over the affairs of the region, Zayta itself fell administratively within the liwā’ (“banner,” referring to a province or district) and nāhiya (a smaller district or local township) of Gaza. In the main, the nāhiyas represented purely

fiscal units that constituted the basis of the taxation system (Hütteroth and Abdulfattah 1977, 20). As such, Zayta—one of over two hundred villages in its district—paid taxes to Gaza at the rate of 25 percent of its agricultural production of wheat and, to a lesser extent, barley, but mostly for its yield from various summer crops (including sorghum, melons, beans, vegetables) and fruit trees. The inhabitants also raised goats and kept beehives.

Beit Jibrîn (formerly Eleutheropolis) also lay within the Gaza district at this time, and though it, too, fell within the classification of qarya, the village remained slightly larger than the one at Zayta. The Ottoman registers of 1596 recorded fifty households (hāna and mujarrad) with an agricultural pro-duction of four times more wheat, twice as much barley, and significantly larger holdings of flocks (> 5x) than Zayta. The residents at Jibrîn added sesame to their summer crops, but, interestingly, fruit trees do not appear in their economic inven-tory. Compared to Zayta, the village paid four times more rev-enue to Gaza from punishments, marriage taxes, and the like; in addition, while the two settlements were taxed at the same rate (25 percent), the farmers at Beit Jibrîn provided 2.4 times more in total tax income for the district (Hütteroth and Abdul-fattah 1977, 149). Locally, then, the old political and religious center once known as Eleutheropolis remained a leading town in the Guvrin Valley east of Tel Zayit/Zayta.

But the shifting political and economic attachments main-tained by villagers throughout this valley continued to exhibit bi-directional ties typical to their liminal-zone location. The hamlet at Tel Zayit survived on the edge of the wadi through the nineteenth century, as confirmed by the surveys of Conder and Kitchener in the 1870s. But by the British Mandate in Palestine, the administrative obligations of both this village and the slightly larger Beth Guvrin shifted from the coastal region back to the hill country, with a district capital now at Hebron (see Khalidi 1992, xxvi–xxvii maps 2–3; 204, 209–11, 227). Once again, Tel Zayit and Tell es-Sâfi (with Barqusya between them) lay at the westernmost boundary of a political

Figure 22. Stone-cut cup from the Roman period. Photograph by Ron E. Tappy.

52 NEAR EASTERN ARCHAEOLOGY 75:1 (2012)

unit based in the highlands. At least from the third century c.e. (Rome’s Severan period), a road had connected Hebron to Beth Guvrin. From there, as of old, the route continued west through the Nahal Gurvin, passed Tel Zayit and al-Faluja (el Fâlûjeh in the British survey; today Pelugot Junction), and ran on to the village of al-Majdal (SWP = el Mejdel), founded next to Ashkelon in the sixteenth century and known today as Migdol (figs. 5, 23).17

Because the water in the Nahal Guvrin grew stagnant during the Mandate period, the inhabitants of Khirbet Zayta moved their site 1 km north of the wadi. (During the 1870s, the com-munity at Beit Jibrîn had faced a similar epidemic [Clermont-Ganneau 1896, 440].) Even in this decision, however, they kept within easy access of the roadway connecting Jibrîn to al-Majdal. Toll stations or caravanserais (hāns) had operated along such roads at least since the Mamluk period (Sauvaget 1941, 10–41; cf. figs. 1, 2, 6, 10, and 11; Hütteroth and Abdul-fattah 1977, 33–35), and, though corroborative data remain scant, it seems likely that Tel Zayit may have benefited from this practice in recent centuries.

ConclusionFor more than three millennia, those who lived and died at

Tel Zayit/Zayta understood the challenges and the benefits of calling a borderland community their home. Such an environ-ment fostered and even secured its own longevity by promoting the acculturation rather than rigid assimilation of its residents, whether they originated from a coastal or a highland core. Recent investigations into the appearance and destiny of both the Israelites and the Philistines within the land of Canaan have begun to recognize this important phenomenon (e.g., Stone 1995; Faust and Lev-Tov 2011), but a similar cultural melting pot persisted in later periods as well. Historically, self-interests prompted the inhabitants of this borderland area to exercise their hard-earned autonomy (Tappy 2008c) while maintaining a symbiotic relationship with the cultural cores surrounding them (Tappy 2008a). Both actions typify liminal-zone groups. Occasionally, however, imperial intruders (e.g., the Assyrians [Tappy 2008b], Romans, and British) disrupted local patterns and exploited this strategic region for their own purposes.

Notes1. All fieldwork at Tel Zayit has proceeded in accordance with licenses granted by the Israel Antiquities Authority to Ron E. Tappy, the project director. The Israel-Palestine Grid Coordinates for Tel Zayit are 133960–115260 (Old Israeli Grid) or 183960–615260 (New Israeli Grid); see Map Gat 94. Tel Zayit is also located 13.71 km west and 13.37 km south of Beth-shemesh and 8.66 km west and 25.52 km south of Gezer.2. In addition, this project is affiliated with the American Schools of Oriental Research and the W. F. Albright Institute of Archaeological Research.3. In this sequence, the Nahal Guvrin first meets the Nahal Lachish just north of Sapheir (modern Merkaz Shapira). From there, the two continue as a solitary stream until approaching the main coastal route slightly northeast of Ashdod. Here the Elah Valley effluence also joins this stream as it continues on a northward course for only a short dis-

tance more before turning toward the west, flowing past Tel Mor, and finally reaching the Mediterranean only 14 km south of the Sorek.4. Other longitudinal routes to their east lay farther up in the hill coun-try of Judah and connected such sites as Tel Halif, Tell Beit Mirsim, and Tell Eitun, or still farther east, Khirbet Rabud (biblical Debir), Hebron, and Beth-zur (see Dorsey 1991, 152, map 9).5. For detailed studies of these districts, see Rainey 1980, 194–202; 1983, 1–22.6. In view of the astounding detail of the map, and notwithstanding the inconsistencies contained therein, it remains difficult to accept Salway’s (2001, 47) conclusion that this work grew out of a single compiler’s “personal experience of travel.”7. Most authorities attribute the map’s strange 22:1 ratio to the presump-tion that the creator of the original utilized a papyrus roll (replaced with parchment in the medieval copy), which had an inherently restricted width but which could run to an unlimited length (Dilke 1985, 114; Matthews 2006, 76). Cannot one assume, however, that a Late Roman artist could have easily stitched together multiple papyrus leaves to cre-ate an expanded vertical space as well as an extended horizontal one?8. Talbert (2010, 135–36, 144–45) thinks the map may have been pro-duced as a commemorative display (perhaps as a frieze along a wall in an imperial reception hall) around 300 c.e., while Rainey and Notley (2006, 13) place its origin in the second century c.e. In any event, the map—like the nonpictorial Antonine Itinerary—awards no special prominence to the Holy Land or to the rising tide of Christian influ-ence under Constantine (unless one takes the delineation in red [versus pale brown] of the name and physical location of the Mount of Olives as such an indicator [see n. 12 below], despite the fact that the iconic figures associated with Rome, Constantinople, and Antioch clearly exhibit non-Christian origins; see, e.g., figs. 17a–c). In any event, the PT predates the Madaba mosaic map (ca. mid sixth century c.e.) by more than two centuries.9. One must, of course, acknowledge that travelers also exploited vari-ous waterways and seas, as confirmed by Theophanes’ use of the Nile in the first and final legs of his round-trip journey from Hermopolis to Antioch around 320 c.e. (Salway 2001, 34; Matthews 2006, 47, 57 map 1, 123, 127–30), by maritime itineraries that accompany the terrestrial ones in the Antonine Itinerary (Salway 2001, 42–43), and by the Dura

Figure 23. SWP Sheets 16, 19, 20: Ashkelon Area, Showing Location of el Mejdel (modern Migdol).Courtesy of Todd Bolen, BiblePlaces.com.

NEAR EASTERN ARCHAEOLOGY 75:1 (2012) 53

Shield, which depicts boats moving between various coastal stations along the northern shore of the Black Sea sometime in the first half of the third century c.e. (Brodersen 2001, 15). While omitting open-sea itineraries, the TP itself appears to have preserved a partial record of waterways in northern Italy and south-central Germany and occasion-ally to have transformed other coastal water routes into land-based roadways (Salway 2001, 44; see the comments by Talbert 2010, 127). Interestingly, the Hellenic culture bequeathed to us only maritime itineraries (períploi)—including, it seems, the line work on the Papyrus Artemidorus (see n. 10 below). Terrestrial mapping appears to have arisen in the Roman world (Dilke 1985, 112; Salway 2001, 26).10. With the initial publication (Gallazzi and Kramer 1998, 190–208; Kramer 2001, 115–20) of Artemidorus of Ephesus’s description of the Iberian Peninsula—in the second of eleven books known as Geogra-phoúmena and supposedly dating from the late second or early first century b.c.e.—some scholars saw this work as the archetype of illus-trated mapping with pictorial vignettes (Salway 2001, 29–30). More recently, however, debate has surrounded the authenticity of this geo-graphical text and map (see Talbert 2009, 57–58 and Gallazzi et al. 2008 versus Canfora 2007, 2008, 2009, 2011; for a summary of the argu-ments, see Janko 2009, 403–10).11. In another instance, however, this itinerary preserves the designa-tion “civitas Lidda” (Cuntz 1990, 98, 600.3)12. Suggestions generally range from the first through the fourth or even early fifth centuries c.e. Those favoring the later end of the chron-ological spectrum generally point to the presence and prominence of the name “Constantinopolis,” a city built over the preexisting Byzan-tium and consecrated in 330 c.e. (Salway 2001, 44–47, fig. 3.3). At the same time, the map unexpectedly fails to include the principal fourth-century route from Constantinople to Antioch via Asia Minor. Such discrepancies lead other scholars to view Constantinople as a postorigi-nal and rather clumsily executed insertion in the place of Byzantium (Talbert 2010, 109, 124, 133–36 with n. 11; Matthews 2006, 72). Even some who date the original map to the fourth century wisely recognize the likelihood that this rendition already represented the final of many evolutionary stages in which redactors repeatedly laid emergent details from the Roman Empire over an older map depicting much earlier times (Matthews 2006, 71–72; see Arnaud 1988, 309, for the view that the map’s wide range of apparent chronological indicators points to the diverse sources utilized by one cartographer, not to a series of indi-vidual redactors). 13. See Isaac and Roll 1982; Avi-Yonah 2002, 114, 141, 184; also “Legio” in Tsafrir et al. 1994, 170.14. Today’s mile equates to 1,760 yards, or 1,609.34 meters. According to Talbert (2010, 115 n. 190), the Roman mile corresponded roughly to 1,618 yards = 1,475 meters, or approximately 8 Greek stades.15. Admittedly, the mapmaker was sometimes erratic in his application of symbols, but the basic point remains. While some have understood the symbols as quick guides for travelers seeking knowledge of various services at major stops, Talbert does not think the map “was designed for practical use” (Talbert 2010, 122).16. For an early, classic catalogue of milestones, see Thomsen 1917, 1–103. See also Isaac 1978; Roll 1983.17. Avi-Yonah (1976, 52) associates this site with Ptolemy’s Drusias (Geographia 5.15.5), but see Tsafrir et al. 1994, 114 for Hirbet Midras/Drusias and 183, 200 for el Mejdel/Peleia.

ReferencesAharoni, Y. 1979. The Land of the Bible. Philadelphia: Westminster.Aharoni, Y., and R. Amiran. 1954. A Visit to the Tells of the Shephelah

[Hebrew]. Bulletin of the Israel Exploration Society 19:222–25.

Archaeological News [Hebrew]. 1979. Hadashot Arkheologiyot 72:31.Arnaud, M. P. 1988. L’origine, la date de rédaction et la diffusion de

l’archétype de la Table de Peutinger. Bulletin de la Société nationale des antiquaires de France 1988:302–21.

Avi-Yonah, M. 1976. Gazetteer of Roman Palestine. Qedem 5. Jerusalem: Institute of Archaeology, Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

———. 2002. The Holy Land: A Historical Geography from the Persian to the Arab Conquest (536 B.C.–A.D. 640). Jerusalem: Carta.

Bloch, M. L. B. 1953. The Historian’s Craft. Translated by P. Putnam. New York: Knopf.

———. 1974. Apologie pour l’histoire ou Métier d’historien. Paris: Colin.———. 1995. Histoire et historiens. Paris: Colin.Braudel, F. 1972. The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean World in

the Age of Philip II. New York: Harper & Row.———. 1980. On History. Translated by S. Matthews. Chicago:

University of Chicago Press.Brodersen, K. 2001. The Presentation of Geographical Knowledge for

Travel and Transport in the Roman World. Pp. 7–21 in Travel and Geography in the Roman Empire, ed. C. Adams and R. Laurence. New York: Routledge.

Canfora, L. 2007. The True History of the So-Called Artemidorus Papyrus: With an Interim Text. Bari, Italy: Edizioni di Pagina.

———. 2008. Il Papiro di Artemidoro. Bari, Italy: Editori Laterza.———. 2009. Artemidorus Ephesius: P. Artemid., sive Artemidorus

personatus. Bari, Italy: Edizioni di Pagina.———. 2011. La meravigliosa storia del falso Artemidoro. Palermo:

Sellerio.Clermont-Ganneau, C. 1896. Archaeological Researches in Palestine

during the Years 1873–1874. Vol. 2. London: Palestine Exploration Fund.

Cohen, R. 1975. Churches, Ozem. P. 310 in vol. 1 of Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land, ed. M. Avi-Yonah. Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society; Masada Press.

Conder, C. R., and H. H. Kitchener. 1998. Judaea. Vol. 3 of The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. London: The Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund, 1883. Repr., Archives Edition. London: Palestine Exploration Fund.

Cuntz, O. 1990. Itineraria Romana: Volumen Prius, Itineraria Antonini Augusti et Burdigalense. Stuttgart: Teubner.

Dagan, Y. 1992. The Shephelah during the Period of the Monarchy in Light of Archaeological Excavations and Surveys. Unpublished M.A. thesis. Tel Aviv University.

Dar, S., and S. Applebaum. 1973. The Roman Road from Antipatris to Caesarea. Palestine Exploration Quarterly 105:91–99.

Dilke, O. A. W. 1985. Greek and Roman Maps. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press.

Dorsey, D. 1991. The Roads and Highways of Ancient Israel. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Faust, A., and J. Lev-Tov. 2011. The Constitution of Philistine Identity: Ethnic Dynamics in Twelfth to Tenth Century Philistia. Oxford Journal of Archaeology 30:13–31.

Finkelstein, I. 1979. The Holy Land in the Tabula Peutingeriana: A Historical-Geographical Approach. Palestine Exploration Quarterly 111:27–34, pls. II–III.

Fischer, M., B. Isaac, and I. Roll. 1996. Roman Roads in Judaea II: The Jaffa-Jerusalem Roads. BAR International Series 628. Oxford: Tempus Reparatum.

54 NEAR EASTERN ARCHAEOLOGY 75:1 (2012)

Gallazzi, C., and B. Kramer. 1998. Artemidor im Zeichensaal: Eine Papyrusrolle mit Text, Landkarte und Skizzenbüchern aus späthellenistischer Zeit. Archiv für Papyrusforschung 44:190–208.

Gallazzi, C., B. Kramer, and S. Settis, eds. 2008. Il Papiro di Artemidoro (P. Artemid.). Milan: Edizioni Universitarie di lettere Economia Diritto.

Hütteroth, W.-D., and K. Abdulfattah. 1977. Historical Geography of Palestine, Transjordan and Southern Syria in the Late 16th Century. Erlangen: Fränkische Geographische Gesellschaft.

Iliffe, J. H. 1933. Greek and Latin Inscriptions in the Museum. The Quarterly of the Department of Antiquities in Palestine 2:120–26, pls. XLIV–XLVI.

Isaac, B. 1978. Milestones in Judaea, from Vespasian to Constantine. Palestine Exploration Quarterly 110:47–60.

Isaac, B., and I. Roll. 1982. Roman Roads in Judaea I: The Legio-Scythop-olis Road. BAR International Series 141. Oxford: BAR.

Janko, R. 2009. The Artemidorus Papyrus. The Classical Review 59:403–10.

Khalidi, W., ed. 1992. All That Remains: The Palestinian Villages Occupied and Depopulated by Israel in 1948. Washington, D.C.: Institute for Palestine Studies.

Kramer, B. 2001. The Earliest Known Map of Spain (?) and the Geography of Artemidorus of Ephesus on Papyrus. Imago Mundi 53:115–20.

Levi, A., and M. Levi. 1967. Itineraria Picta: Contributo allo studio della Tabula Peutingeriana. Rome: L’Erma di Bretschneider.

Matthews, J. F. 2006. The Journey of Theophanes: Travel, Business, and Daily Life in the Roman East. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Miller, K. 1916. Die Peutingersche Tafel: Oder, Weltkarte des Castorius. Mit kurzer Erklärung 18 Kartenskizzsen der überlieferten römischen Reisewege aller Länder und der 4 Meter langen Karte in Faksimile. Stuttgart: Strecker & Schröder.

Rainey, A. F. 1980. The Administrative Division of the Shephelah. Tel Aviv 7:194–202.

———. 1983. The Biblical Shephelah of Judah. Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 251:1–22.

Rainey, A. F., and S. Notley. 2006. The Sacred Bridge: Carta’s Atlas of the Biblical World. Jerusalem: Carta.

Ritter, C. 1866. The Comparative Geography of Palestine and the Sinaitic Peninsula. Translated by W. L. Gage. Edinburgh: T&T Clark.

Robinson, E. 1856. Biblical Researches in Palestine, and in the Adjacent Regions: A Journal of Travels in the Year 1838. Vol. 2. Boston: Crocker & Brewster.

Roll, I. 1983. The Roman Road System in Judaea. Pp. 136–61 in The Jerusalem Cathedra: Studies in the History, Archaeology, Geography and Ethnography of the Land of Israel, ed. L. I. Levine. Jerusalem: Yad Izhak Ben-Zvi Institute; Detroit: Wayne State University Press.

Salway, B. 2001. Travel, itineraria and tabellaria. Pp. 22–66 in Travel and Geography in the Roman Empire, ed. C. Adams and R. Laurence. New York: Routledge.

Sauvaget, J. 1941. La Poste aux Chevaux dans l’Empire des Mamelouks. Paris: Librairie d’Amérique et d’Orient.

Stager, L. E. 1995. The Impact of the Sea Peoples (1185–1050 BCE). Pp. 332–48 in The Archaeology of Society in the Holy Land, ed. T. Levy. New York: Fact on File.

Stone, B. 1995. The Philistines and Acculturation: Culture Change and Ethnic Continuity in the Iron Age. Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 298:7–32.

Talbert, R. J. A. 2009. P. Artemid.: The Map. Pp. 57–64, 158–63, figs. 66–70 in Images and Texts on the “Artemidorus Papyrus”: Working papers on P. Artemid. (St. John’s College, Oxford, 2008), ed. K. Brodersen and H. Elsner. Stuttgart: Steiner.

———. 2010. Rome’s World: The Peutinger Map Reconsidered. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tappy, R. E. 2000. The 1998 Preliminary Survey of Khirbet Zeitah el-Kharab (Tel Zayit) in the Shephelah of Judah. Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 319:7–36.

———. 2008a. East of Ashkelon: The Setting and Settling of the Judaean Lowlands in the Iron Age IIA Period. Pp. 449–63 in Exploring the Longue Durée: Essays in Honor of Lawrence E. Stager, ed. J. David Schloen. Winona Lake, Ind.: Eisenbrauns.

———. 2008b. Historical and Geographical Notes on the “Lowland Districts” of Judah in Joshua 15:33–47. Vetus Testamentum 58:381–403.

———. 2008c. Tel Zayit and the Tel Zayit Abecedary in Their Regional Context. Pp. 1–44 in Literate Culture and Tenth-Century Canaan: The Tel Zayit Abecedary in Context, ed. R. E. Tappy and P. Kyle McCarter. Winona Lake, Ind.: Eisenbrauns.

Tappy, R. E., P. K. McCarter, M. J. Lundberg, and B. Zuckerman. 2006. An Abecedary of the Mid-Tenth Century b.c.e. from the Judaean Shephelah. Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 344:5–46.

Thomsen, P. 1917. Die römischen Meilensteine der Provinzen Syria, Arabia und Palaestina. Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins 40:1–103 .

Tsafrir, Y., L. Di Segni, and J. Green 1994. Tabula Imperii Romani. Iudaea, Palaestina: Eretz Israel in the Hellenistic, Roman and Byzantine Periods, Maps and Gazetteer. Jerusalem: Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities.

Weber, E. 1976. Tabula Peutingeriana: Codex Vindobonensis 324. Graz: Akademische Druck & Verlagsanstalt.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Ron Tappy is the G. Albert Shoemaker Professor of Bible and Archaeology at Pittsburgh Theological Seminary, the Director of the James L. Kelso Muse-um, and the Projec t Director of The Zeitah Excavations. He received his AM and PhD from Harvard University. He conducted a sur face survey at Tel Zayit in 1998 and, to date, has completed nine seasons of excavat ion at t he site, where his research focuses on the nature of borderland settlements during the Iron Age.