The breeds of the Kingdom. An unpublished manuscript by Federico Grisone

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

3 -

download

0

Transcript of The breeds of the Kingdom. An unpublished manuscript by Federico Grisone

The breeds of the Kingdom An unpublished manuscript

by Federico Grisone

Giovanni Battista Tomassini

The bay Stella, one of the horses portrayed on the walls of Enrico Pandone’s Castle in Venafro (Is), sent as a gift to Annibale Caracciolo in 1524

(Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Activities and Tourism Soprintendenza per i beni storici, artistici ed etnoantropoligici del Molise)

Giovanni Battista Tomassini 2

Published on WORKSOFCHIVALRY.COM 18th July 2014

Mariano Téllez-Girón y Beaufort Spontin’s standard of living became a legend. Within a few decades, the twelfth Duke of Osuna (1814-1882) was able to squander the immense patrimony of the most important and wealthy family in Spain. As Ambassador in Russia, he traveled across Europe on his private train, indulging in every extravagance. It is said that his horses were shod with silver alloy horseshoes. When his years came to an end, he had already accumulated a colossal debt and, therefore, a committee was formed of his creditors that put together an inventory and handled the sale of his assets. In three centuries, the Dukes of Osuna, in addition to having amassed an impressive number of titles of nobility, had put together a wonderful library of about twenty thousand volumes of printed books and manuscripts. In order not to disperse this important cultural heritage, in 1884, the collection was bought by the State and it was decided to distribute it among the libraries of the kingdom. Most of the books were incorporated to the Biblioteca Nacional in Madrid, while the rest went to the library of the Senate and to some of the leading universities in Spain.

The Osuna Fund is still one of the finest collections of the Biblioteca Nacional de España, in particular with regard to the manuscripts. The collection of volumes of the Dukes of Osuna was formed based on the personal tastes of each duke and also by their individual political and military obligations. It is therefore not surprising that in the property of a family that included two Viceroys of the Kingdom of Naples (the first and the third Duke of Osuna were appointed to this position, respectively from 1582 to1586 and from 1616 to 1620), we find many texts and manuscripts of Italian origin. Among them, several relate to the practice of horsemanship and to the care and breeding of horses and are a real treasure trove for the history of equestrian disciplines. These are works hitherto unpublished and largely unknown to the main equestrian bibliographies, such as those of Menessier de la Lance and Frederick H. Hutt. I owe this discovery to Sabina De Cavi, brilliant Italian researcher who works at the University of Córdoba and that, although she only partially covers matters concerning the equestrian culture, pointed me to the richness and importance of this heritage.

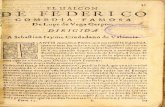

The most valuable and curious piece for historians and equestrian literature enthusiasts is a pergameneous manuscript of the sixteenth century, marked with the number 9246. On the recto of the first card it contains the following header:

Razze del Regno / raccolte in questo volume/ brevemente da federigo grisone gentilhuomo napoletano / Ove appresso dona

Giovanni Battista Tomassini 3

Published on WORKSOFCHIVALRY.COM 18th July 2014

molti belli / avisi convenienti alla cognitione de, i, polletri et al governo et reggere / di ogni cavallo.1

In short, it would be a work hitherto unknown from the famous

Neapolitan gentleman who in 1550 published his treatise, Gli ordini del cavalcare (The Orders of Riding), the first book devoted to horseback riding in print. The Orders had an immediate and extraordinary success, becoming the true founding act of the new literary genre of the equestrian treatise and earning Federico Grisone the title of “father of the equestrian art” (Podhajasky, 1967, p. 18). Suffice it to say that, between 1550 and 1623, there were twenty-one printed editions in Italian, fifteen French translations, six in English, seven in German and one in Spanish. Not to mention the numerous manuscript versions, one of which is in Portuguese.

1 “Breeds of the Kingdom / collected in this volume / shortly by Federigo Grisone Neapolitan

gentleman / Where below gives many beautiful / advices suitable to the knowledge of foals and the care and ownership / of each horse.”

Federico Grisone, Razze del Regno, manuscript 9246, p. 1 Biblioteca Nacional de España – Madrid

Giovanni Battista Tomassini 4

Published on WORKSOFCHIVALRY.COM 18th July 2014

The work contained in the manuscript of the Biblioteca Nacional is a sort of catalog of the best breeding farms (called razze, i.e. “breeds”) in the Kingdom of Naples, which are listed, showing illustrations of their brands and detailing some essential information on the property and, when possible, on the quality of the horses produced. The work is supplemented by a list of names of horses and by some guidelines for choosing the foals, the management of the stables and the feeding of horses. From the linguistic point of view, even if it is simpler and more basic, the text is written in the same style of the Orders of Riding, which is explicitly mentioned. From these aspects, it seems quite possible to attribute the work to Grisone.

Since this is a work hitherto unpublished and entirely unknown to the historians and lovers of horseback riding, I decided to dedicate to it a detailed discussion. For this I have divided this article into two parts, so as not to exceed the size of the normal posts of this blog. In this first part, then, we will focus on the catalog of the breeding farms, while in a subsequent article I will cover the information on the evaluation criteria for the foals and the precepts concerning the stables and the feeding of the horses.

The publication of directories of brands similar to the one presented in this manuscript is well known. Works such as the Libro de marchi de cavalli (The Book of the horses’ brands), published anonymously in Venice in 1569 and then reissued in 1588 and, above all, the remarkable La perfettione del Cavallo (The Perfection of Horse) by Francesco Liberati, published in Rome in 1639. Grisone’s manuscript is

Neapolitan Horse, in baron D’Eisenberg, Description du Manege Moderne dans sa perfection, Paris, 1727, plate IV

Giovanni Battista Tomassini 5

Published on WORKSOFCHIVALRY.COM 18th July 2014

more like the first one, as the one by Liberati is far more wide-ranging. At the beginning of text, the author makes his eminently pragmatic purpose immediately clear: he wants to provide to anyone looking for good horses a clear picture of the best breeding farms where it is possible to obtain them.

Il Regno di Napole, è, situato nella più abbondante, fruttifera e dilettevole parte della Italia nel qual sono millecinquecento città, terre et castelle murate, et infinite altre ville et casali habitati. […] La onde per tante comodità che tiene di herbaggi, di Piani, Monti, Valli et acque sono molte razze per le quali, et sì conveniente il paese, che vi nascono cavalli gagliardissimi, robusti, et di lunga vita, Et con disposizione et mirabile attitudine. Per tanto volendo io darvi cognizione di alcune di esse, per utilità di tutti privati cavalieri et Prencepi che cercano di haver cavalli boni scriverò il nome degli patroni di quelle, et con la loro figura del merco. (1r)2

The description of the breeding farms begins from the royal breed, the so-called Breed of the King, which was the largest and was divided between two provinces: Apulia and Calabria. The horses of the breeding farms in Apulia were branded on the right thigh, while those coming from Calabria were branded on the left. The breeding farms of Apulia produced eight different varieties, or “partite” (parcels), of horses: the Great; the Imperial, the Royal, the Gentle, the Favorite, the Elected, the Small and the one of the Jennets. These were identified by an additional mark stamped on the right cheek of the animal. In the farms of Calabria, five “parcels” were instead distinguished as: the Great, the Medium, the Common, the Small, and that of the Jennets. These were identified by a brand on the left cheek.

The author then explains the intention to list the main breeding farms in the Kingdom. For each he says he will indicate the owner’s name and location. He will then add some notes about those of which he has been able to “have some good cognition” (3r). However, he warns the readers that “generous horses” may also come from the breeding

2 “The Kingdom of Naples is located in the most abundant, fertile and enjoyable part of Italy in which

there are fifteen hundred cities, lands and castles surrounded by walls, and endless other villas and inhabited farmhouses. [...] And having so many pastures, Plains, Mountains, Valleys and waters there are many breeding farms for which the country is so suitable that there born are horses who are very vigorous, robust, and of long life, and with admirable disposition and attitude. Therefore, as I want to give you knowledge of some of them to help all private riders and Princes looking to have good horses, I will write the name of their owners, and with the drawing of the brand.”

Giovanni Battista Tomassini 6

Published on WORKSOFCHIVALRY.COM 18th July 2014

farms of which he cannot provide more information. In the same way, he cautions the readers saying that:

le razze perfette per mancamento di stalloni ponno devenire al fine, o, vero in poco pregio. Et ugualmente le cattive, per aiuto di eccellenti cavalli, si ponno affinare et arrivare in estima grande. Così come anchora da giorno in giorno se ne potrebbero fare altre di maggiore valore, delle quali lasciarò il pensiero a quelli che verranno appresso, à farne memoria. (3r)3

The drawings of the brands of 136 breeding farms follow. The enclosed annotations are, for the most part, very concise. In most cases, the notes specify any variation in the branding of the different “parcels” of the breeding farm, or summarize brief judgments, such as “Brand of the Breed of the Queen of Poland in the territory of Bari4, which breed is good and perfect” (5v), or “Brand of the Breed of the Prince of Salerno. In Basilicata, which Breed generally gives birth to Jennets of good size and of admirable virtue” (7r). There are, however, also critical remarks, such as, for example, in the case of the breeding farm of the Duke of Santo Pietro, in the Territory of Otranto: “the horses of this breed are good runners and dexterous but are of little strength”(12r). Or, as in the case of the Breed of the Marquis of Lucito, in Apulia, “from which come excellent horses although in general before it had more value” (14v).

A note that is more interesting from an historical point, is the one about a breeding farm in Basilicata. To this herd would belong the horse ridden by Francis I (1494-1547), King of France, in the fateful Battle of Marignano (13-14 September 1515), with which the French took possession of the Duchy of Milan.

Merco della razza di Angeluzzo dello Tito. In basilicata. Mandatogli dal re francesco da francia, per caggione che nella giornata di marignano si trovò sopra un cavallo di tal razza et servendolo molto bene hebbe la vittoria. Talché ogn’anno

3 “The perfect breeding farms may end, or deteriorate, for lack of stallions. And, by means of the help

of excellent horses, the bad ones can likewise improve and get to be very esteemed. As well as new one of a greater value could be made day by day, but I will leave the task to think and remind these latter to those who will come after me.”

4 Bona Sforza was consort queen of Poland, consort Grand Duchess of Lithuania from 1518, and sovereign Duchess of Bari from 1524.

Giovanni Battista Tomassini 7

Published on WORKSOFCHIVALRY.COM 18th July 2014

mandava a comprarne polletri. Benchè hora, dopo la morte di Angeluccio, non sia di tanta perfettione. (51v)5

After presenting the brands of the main breeding farms, Grisone reaffirms that the herds of the Kingdom of Naples which give birth “to perfect and marvelous horses (“a cavalli perfetti et meravigliosi”, 71r) are many more of those than he mentioned, but that he decided not to talk about some of them because they often change their brand, or because they have a few mares.

Just as it still happens today, as even during the Renaissance, to

contact the best breeding farms, and perhaps even spend a lot of money,

5 “Brand of the Breed of Angeluzzo dello Tito. In Basilicata. Sent to him by the king Francis from

France, due to the fact that in the day of Marignano he found himself on a horse of this breeding farm that served him so well as to bring him to victory. For this reason every year he sent someone to buy foals of this herd. Though now, after the death of Angeluccio, is no longer with such perfection.”

Federico Grisone, Razze del Regno, manuscript 9246, p. 5v Biblioteca Nacional de España – Madrid

Giovanni Battista Tomassini 8

Published on WORKSOFCHIVALRY.COM 18th July 2014

did not guarantee the purchase of a good horse. After listing and showing the brands of the most renowned breeding farms of the Kingdom of Naples, Grisone states that, even if in those breeding farms can “have horses of such a great a value, that they will surpass all the others that can be found in the world” (“haver cavalli di sì gran valore, che supereranno tutti gli altri che nel mondo si trovano”, 71r), one should, in addition, know how to chose the foals. Because even in the most perfect breeding farms, he says, there are “worthless” horses. Therefore, Grisone recommends to make sure that the selected foals have

il pelo e i segni et la disposizione, et le fattezze de i membri, della maniera che ne ho parlato nel primo libro degli ordini di cavalcare (71v),6

but also to give preference to

quello che tra i polletri va con più ardire, et animo, et leggerezza, a guisa di gatto, ch’entrando et uscendo da mezzo di loro si fa strada, sforzandogli sempre con la sua dilantera. (71v)7

While even following this guideline, he then warns that this is not a set rule and that

alcun di quelli che anderà più lento et pigro potrebbe essere il migliore. La onde bisogna accorgimento grande. Informandovi della buona qualità del patre, et dell’uno, et dell’altro avo, et del fratello di sua matre, et havendo poi gli segni buoni, col manto perfetto et le fattioni ben fatte, benché non dimostrasse quella sollecitudine, si potrebbe, pure, liberamente pigliare perché molte fiate il polletro suole essere simile ad alcuni degli avoli, o veramente al fratello della giomenta sua matre. (71V)8

6 “The hair and the marks [such as stockings, whorls, blazes] and the placing and features of the limbs,

in the way that I explained in the first book of the orders of riding.” 7 “The one who between the foals goes with more boldness and courage, and lightness, like a cat that

going in and out of the midst of the herd makes his way with the power of his chest.” 8 “Some of those who move more slowly and look lazy might be the best. So great care is needed. You

must inquire of the good quality of the father and of the other ancestors, and of his mother's brother, and then having the good marks, with a perfect coat and the appropriate features, although he does not demonstrate that promptness, you could feel free to chose him because in many cases the foal is similar to some of his ancestors, or to the brother of his mother.”

Giovanni Battista Tomassini 9

Published on WORKSOFCHIVALRY.COM 18th July 2014

The blood relationships are seen as particularly important. Grisone says that it is important also to inquire about the docility and the good will of the father of the foal, because from an undisciplined stallion, even if he is beautiful and physically perfect, rarely come foals who will become a success. He also suggests to favor animals raised in rugged and mountainous country, with good pastures, but far from water sources, so that to nourish and drink the horses have to move over the distance and thus they become more robust and enduring. In the assessment of a foal one must also make sure that he has good eyesight and, to do this Grisone suggests, observe how he moves his ears while walking. If the foal moves them often, turning them over one at a time, it is generally a sign of poor eyesight, but in some cases, the author says, this attitude is only due to his inexperience and the fear of the environment that surrounds him. According to Grisone, poor sight is produced by some defect in the semen from which the animal was procreated, or by the fact that he ate some toxic weed in the pasture. He also suggests that it could be because he is the son of a stallion who is too old. According to the author, the reproductive age goes from five years up to twelve for the stallions and from three to twelve for the mares.

Grisone then evokes the splendor of the Aragonese cavalry:

Ben mi pare dichiararvi che in niuna età sia stata in maggior prezzo la cavallaria, così come fù nel tempo del Re Alfonso di aragona et del Re Ferrante vecchio, et del giovene, che non solo per la cura che in essa tenevano, gli cavalli erano dotati di bella disposizione et mirabile attitudine, ma ornati di bel nome. (73v)9

While speaking of the names of the horses, he explains that at that time although a name was given to each foal at the moment of his birth, when the foal began to be ridden usually this name was changed, according to his beauty, his value and his virtues, so that the name was a better match to his actual qualities. Grisone agrees with this habit and he then lists 283 horses’ names, so that the readers can chose between them those that fit their horses better. Otherwise, he suggests to give them the surnames of the owners of the breeding farms, or, if these latter are noble, the name of the city which they hold. The names listed range from the classic Bucephalus to the magniloquent Monarca (i.e. Monarch),

9 “It seems well to me to declare that in no age did cavalry have a greater value than in the time of the

King Alfonso of Aragon and of the Kings Ferrante the elder and the younger, during which, for the care that they held in it, the horses were provided with a nice disposition and a wonderful attitude, but adorned with a beautiful name.”

Giovanni Battista Tomassini 10

Published on WORKSOFCHIVALRY.COM 18th July 2014

Sangiorgio (San George) and Nobile (Noble), and to more common names like Gentile (Gentle), Thesoro (Treasure), Scacciapensiero (Worries dispeller) and Portabene (Lucky charmer), up to the sinister Scorpione (Scorpion) and Furiainfernale (Infernal fury).

Grisone then goes on describing how the stable should be maintained. It should be neither too hot in summer nor too cold in winter, but above all not moist and not exposed to wind. At that time, the horses were kept in “posts”, that is to say, in stalls where they were tied to the manger, separated by partitions. The stall could be paved with bricks or boards, but the pavement should not reach the distance along the floor to the front legs. In fact, it was believed that the front hooves should stand on the bare ground,

According to Grisone this was the brand of the horse ridden by Francis I during the battle of Marignano

Federico Grisone, Razze del Regno, manuscript 9246, p. 51v

Giovanni Battista Tomassini 11

Published on WORKSOFCHIVALRY.COM 18th July 2014

altrimente si diseccarebbeno le ungne, di esse, onde facilmente per tale cagione verrebbe al loro qualche spetie di setula o veramente di quarto. (83r)10

The author also prescribes building the manger quite low. Both,

because in this way, the horse does not run the risk of knocking against it, injuring his chest, but also because it is typical of quadrupeds to eat with their head down. So much so, he adds, that in some cases, when the horse’s shoulders are soared, it is enough to let him graze a few days to heal. The horses were not only kept tied to the manger, but during the day their hind and one front leg were tethered. Grisone also recommends preventing all those who work and visit the barn from relieving themselves inside the stable, as the smell of human dejections would cause the horses to lose weight and to incur serious diseases.

Et guardasi il Cavaliero consentire che nella cavallerizza, o privata stalla, vi sia il destro, che non è cosa che mantenghi

10 “Otherwise the hooves would dry, and for that reason they would have easily some sort of hoof

crack, or quarter.”

Neapolitan courser William Cavendish of Newcastle, Méthode et invention nouvelle

dans l’art de dresser les chevaux, 1658

Giovanni Battista Tomassini 12

Published on WORKSOFCHIVALRY.COM 18th July 2014

più magri i cavalli et che gli consuma la vita, con infirmità grandi et mortali, come la puzza del secesso et sterco dell’huomo. (83r-83v)11

According to Grisone the stable must be illuminated at night and should have skilled and solicitous grooms, each of who must care for no more than four or five horses, given the fact that every animal should be curried for at least half an hour a day. The cleaning of the stables must begin at sunrise in summer and at least one hour before sunrise in winter. The horse should receive first of all the fodder, then the water, and then the grain. The ration of oats, or barley, was given in the morning and in the evening, but the author praises that in the summer, it was also given a supplementary ration at noon. According to Grisone, the fodder must be given at least three or four times throughout the day: straw in the summer and hay in winter. Even if, in his opinion, after the fifth year of age, the best thing is to feed the horses always with straw:

Che ben si dice ragionevolmente, Caval di orgio e paglia cavallo di battaglia. (84r)12

The diet of adult horses was mostly based on dry forage. While Grisone recommends giving grass to the foals up to five years, particularly during the months of April and May. In June, instead the diet may be supplemented by stubble, accompanied by the ordinary oats. Grisone advises against giving grass to the horses in March and recommends to gradually accustom the animals to fresh forage and to bleed them when they enter in the new diet regimen, after about ten days, and again before moving on to eat stubble. However, in the case of young foals or of particularly thin horses, the blood-lettings can be reduced to only two. To accustom the horses to dry forage again during the summer, Grisone suggests mixing a few bunches of chicory into the straw, or mauve, or vine-shoots, or willow buds. In December, he recommends instead to mix lupines into the straw, or hay, while having the foresight to dry them first for a few days and gradually accustom the animals to avoid the risk of colic.

The text ends rather abruptly with the promise to expand the discussion afterwards to cover the criteria of proper breeding and of the care of diseases:

11 “And the Rider beware of allowing that in the stable, or private barn, there are human excrements,

because there is nothing that keep horses more thin and consumes their lives, causing large and deadly diseases, such as the smell of human dung.”

12 “That is reasonably said: horse of barley and straw horse for war” (unfortunately in the translation we lose the rhyme of this proverb).

Giovanni Battista Tomassini 13

Published on WORKSOFCHIVALRY.COM 18th July 2014

Hora tacendo non bisogna dirne più oltre, reservandomi appresso con la voluntà et aiuto dell’eterno Iddio parlarne più diffusamente et non solo di alcuni particolari che accadeno alle cose ragionate, ma dell’ordine di mantinere le Razze. Et in ultimo di curare i cavalli delle loro infermità, cosi come conviene usarsi da ogni cavaliero. (87r)13

The presence of this and of other manuscripts about equestrian topics in the Osuna Fund of the Biblioteca Nacional de España in Madrid (which we will further cover in future articles) shows that, contrary to what has so far been considered, the printing of the first equestrian treatises in the mid-Sixteenth century, was not a radical innovation. Between the Fifteenth and Sixteenth centuries the circulation of texts devoted to horseback riding, as well as to the care and breeding of the horse, was certainly not limited to the most famous works, which have easily reached us, because they were spread into a greater number of specimens through printing. It is evident that several other works devoted to horseback riding circulated in manuscript form and this limited their reproduction and dissemination. Many of these are likely to be lost, and many, such as the Razze del Regno by Federico Grisone, must be rediscovered and deserve the attention of scholars and enthusiasts because they enrich our knowledge of the equestrian tradition.

Bibliography

ANONIMO, Libro de' marchi de' caualli, con li nomi de tutti li principi et priuati signori che hanno razza di caualli, In Venetia, appresso Nicolò Nelli, 1569.

DE CAVI, Sabina, Emblematica cittadina: il cavallo e i Seggi di Napoli in epoca spagnuola (XVI-XVII sec.), in AA. VV. Dal cavallo alle scuderie. Visioni iconografiche e rilevamenti architettonici, atti del convegno internazionale (Frascati, 12 aprile 2013), a cura di M. Fratarcangeli, Roma, Campisano Editore, 2014, pp. 43-53..

HUTT, Frederick Henry, Works on horses and equitation. A bibliographical record of hippology, London, Bernard Quaritch, 1887.

13 “Now keeping silence I should not say more, putting off, with the will and help of the eternal God,

to talk about it in more detail later, and not just about few details of what I discussed here, but also of the order of how to keep the breeding farms. And finally about how to cure horses of their infirmities, as well as it should be of use to every rider.”

Giovanni Battista Tomassini 14

Published on WORKSOFCHIVALRY.COM 18th July 2014

LIBERATI, Francesco, La Perfettione del cavallo, Roma, per Michele Hercole, 1639.

MENNESSIER DE LA LANCE, Gabriel-René, Essai de Bibliographie Hippique donnant la description détaillée des ouvrages publiés ou traduits en latin et en français sur le Cheval et la Cavalerie avec de nombreuses biographies d’auteurs hippiques, Paris, Lucien Dorbon, 1915-21.

PODHAJASKY, Alois, The complete training of Horse and Rider. In the principles of classical Horsemanship, Chatsworth, Wilshire books Company, 1967.

TOBAR, María Luisa, Fondo Osuna en la Biblioteca nacional de Madrid, in AA.VV., Cultura della guerra e arti della pace: il 3° Duca di Osuna in Sicilia e a Napoli, (1611-1620), diretto da Encarnacion Sanchez Garcia; a cura di Encarnacion Sanchez Garcia e Caterina Ruta, Napoli, Pironti, 2012, pp. 97-122.