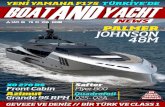

2005. The Herculaneum Boat Project. Unpublished manuscript.

Transcript of 2005. The Herculaneum Boat Project. Unpublished manuscript.

Final Report

Grant #2610-83

THE HERCULANEUM BOAT PROJECT

J. Richard Steffy, Professor Emeritus, Institute of Nautical Archaeology and

Texas A&M University, College Station, Texas 77843.

Mailing Address: P.O. Drawer HG, College Station, Texas 77841-5137. Phone:

409/845-6398

Mr. Steffy is a specialist in wooden ship construction and has been associated

with numerous shipwreck excavations in the United States, Europe, and Asia over

the past twenty years. He was awarded a MacArthur Fellowship in 1985 for his

work in this field. He became a member of the Institute's staff in 1974 and joined

the Texas A&M faculty in 1976, retiring from both positions in 1990.

Steffy - 1

ABSTRACT

THE HERCULANEUM BOAT: EXTERIOR DETAILS

During the summer of 1982, archaeologists uncovered an inverted Roman boat

while excavating an area of the ancient beach near the Suburban Thermae at

Herculaneum. The boat was a victim of the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius in A.D. 79,

whose hot surges and pyroclastic flows carbonized the hull and buried it beneath

23 m of overburden. More than two-thirds of the hull was exposed when this

study was made, the rest of it being in a displaced or fragmentary state.

The vessel is estimated to be 8.6 m long, 2.2 m wide, and about 85 cm

deep. The stem has not been found, but the curved sternpost is preserved

extensively. The keel, sided 7.2 cm and molded 6 cm, was protected by a false

keel 2.1 cm thick. There were eight strakes of bottom planking on the port side

(seven on the starboard side); a wale, side stake, and caprail completed the

planking plan on each side. Planking was about 2.5 cm thick and was edge-joined

by means of closely spaced mortise-and-tenon joints, each locked by a pair of

tapered pegs.

Although the frames are not yet visible, the fastening pattern reveals that

the framing plan consisted of floor timbers alternating with paired half-frames.

Frames were fastened to planks with treenails and bronze nails. A through-beam

penetrated the sides of the stern above the wales.

Steffy - 2

The Herculaneum boat is briefly compared with the Kinneret boat, a well-

preserved hull recently excavated at Lake Kinneret (Sea of Galilee), Israel. Both

boats are similar in size and dating.

Steffy - 3

CAPTIONS FOR ILLUSTRATIONS

Figure 1. Plan of the ancient beach area at Herculaneum, showing the

location of the boat. (From Sigurdsson et al 1985:367)

Figure 2. Stratigraphy surrounding the boat. The boathouse sheltering

the vessel is modern. (From Sigurdsson et al 1985:367)

Figure 3. The boat in situ. The white cords reveal sectional hull shapes

at 50 cm intervals.

Figure 4. The author's tentative reconstruction of the port side of the

Herculaneum boat, showing the planking arrangement and approximate locations

of topside appointments. This is a sketch, not a scaled drawing.

Figure 5. (a) A cross-section of the keel at a location 2 m forward of the

after perpendicular (sternpost rabbet/caprail intersection). (b) Cross-sectional

shape of the port side of the sternpost, about 30 cm below its juncture with the

caprail.

Figure 6. Hull section near amidships, as found. Distortion influences

this shape; the hull probably was narrower and had a harder bilge.

Figure 7. Typical mortise-and-tenon joints.

Figure 8. Wale, side strake, and caprail

arrangement at a point 50 cm from the sternpost on the starboard side. The sketch

at right illustrates the hooding end of the wale at the sternpost.

Steffy - 4

Figure 9. Arrangement of nails and treenails attaching port strake 3 to

frame 5 near the stern; surrounding tenon pegs are also shown. Details of two

typical bronze nails are illustrated below. Their lengths are unknown.

Figure 10. Top and port side view of the through-beam arrangement in

the stern.

Figure 11. Sectional and side views of the patch tenon on starboard

strake 3. The sternpost rabbet is 24 cm to the left.

Figure 12. Staples (or metal shafts resembling parts of staples) and patch

tenons along the seams of port strakes 3, 4, and 6. The stern is toward the right.

Figure 13. The inserted piece in port strake 7.

Figure 14. The author's preliminary lines drawing of the Kinneret boat.

(From Wachsmann et al 1990)

Note: The photograph and all drawings except Figures 1 and 2 are by the author.

Steffy - 5

THE HERCULANEUM BOAT: EXTERIOR DETAILS

J. Richard Steffy

Many of the ships and boats uncovered by archaeologists were victims of violent

events, but few, if any, were wrecked more dramatically than the Herculaneum

boat. First century Herculaneum was a prosperous and luxurious Roman city of

about 5,000. The view from the city must have been magnificent--to the east was

Mt. Vesuvius; to the west, the blue waters of the Bay of Naples lapped at the

shore beneath a bluff, along which a series of arched chambers surrounded the

city's Marine Gate and supported the Sacred Area above (Figure 1). At the

southern end of the row of chambers were the elegant Suburban Thermae, which

could be entered by a stairway from the beach or through a hanging garden above.

THE SITE

The city and all who remained in it (after initial ashfall had sent some

residents fleeing toward safety in Naples) were destroyed on the morning of

August 25, A.D. 79, when Vesuvius unleashed a series of surge clouds and

pyroclastic flows. The eruption and its resulting geological patterns were

documented previously by scientists sponsored by the National Geographic

Society (Sigurdsson et al 1985). Haraldur Sigurdsson, who made an extensive

Steffy - 6

study of the stratigraphy surrounding the boat, deduced that the vessel was on the

beach south of the Thermae before the first surge struck at about 1 a.m. It was not

moved any great distance by this surge, but the first pyroclastic flow that followed

probably engulfed the boat and carried it to its final inverted position about 5 m

west of the seaward wall of the Thermae. Along the way it was rolled over and

battered by timbers and other dislodged materials, causing its sides to separate

and its bow to break and partially fold inside the hull. The boat came to rest atop

the first surge layer and was carbonized by the heat of the pyroclastic flow

(Figure 2). A second surge blasted the exposed bottom of the hull; a second

pyroclastic flow completely buried it. Subsequent surges and flows deposited 23

m of volcanic material in the area.

Archaeologists uncovered the keel and bottom planks of the Herculaneum

boat while excavating this area of the ancient beach in 1982. By the summer of

1983, when most of this information was compiled, two-thirds of the exterior

surface of the hull had been exposed. The seaward one-third of the hull remained

partly unexcavated, including a two-meter-long section that had been folded

under the rest of the structure. Although cracked, distorted, and extremely fragile

due to its carbonized state, most of the excavated part of the hull was preserved

from keel to gunwale (Figure 3). Until the boat's interior and seaward end have

been recorded, some reservation remains concerning the orientation of its bow

and stern. I will henceforth call the inshore end the stern because a through-

Steffy - 7

beam, a bulkhead, and a pair of bitts at that end strongly suggest that a pair of

quarter rudders were mounted there.

The sternpost disappeared into the pyroclastic material at its juncture with

the caprail; its upper end has yet to be excavated. Both sides of the aftermost 2

meters of the hull survived completely except for the lower post and keel.

Forward of this location the sides of the hull had separated from the keel and were

uneven, sometimes with gaps or broken areas caused by the weight of overburden

on randomly supported surfaces. Carbonization had shrunk most of the wood, so

that planking seams were now separated and dimensions were unreliable in some

cases. It also made interpretation, even recognition, of some features difficult.

Furthermore, the interior of the hull, always more important in ancient boat

studies than the exterior surfaces, could not be recorded at all.

Hull shapes were recorded at 50 cm intervals, and I have been informed

that extensive mapping and stereophotography have been done since this

information was compiled. Nevertheless, the nature of the wreck is such that an

extensive reconstruction--hull lines, detailed section drawings, etc.--would be

partly conjectural and probably misleading. After the hull has been removed from

the site, freed of its present protective coatings and completely stabilized, it

should be possible to align the garboards with the keel, smooth out and

reassemble the broken areas, record the interior construction, and develop an

accurate set of hull lines. This report, then, will deal with hull design only

Steffy - 8

superficially and concentrate largely on exterior construction details.

The boat was exposed over a continuous length of 7.6 meters, although the

forward end of the side that had folded under was visible, indicating that nearly

another meter of hull had survived. Since one of these planks appeared to be a

hooding end which fit into the stem rabbet, the suggested overall length of the

Herculaneum boat is calculated tentatively at 8.6 meters. Its beam was about 2.2

meters and its depth from keel to caprail was just under a meter (85 cm in its

current form) near amidships (Figure 4). The wood analysis is being done by

others, although preliminary samples taken in 1982 indicated that the boat was

framed in hardwood and planked in softwood. This was a common feature of

Roman boatbuilding, as was its form of construction in which the planks were

edge-joined and some or all of them were erected before the permanent

framework was installed.

KEEL AND STERNPOST

The keel was sided (wide) 7.2 cm and molded (deep) 6 cm throughout

(Figure 5). Its upper edges were chamfered for the seating of the garboards,

which were attached by means of mortise-and-tenon joints to be described in the

planking section below. No scarfs could be found: the area where it probably was

joined to the sternpost was missing.

The keel was protected by a shoe, or false keel, whose original thickness

Steffy - 9

was determined to be 2.1 cm. Either by wear or manufacture, its sides tapered to

a lower width of 4.9 cm and its lower edges were rounded. About 3.2 m of this

member survived in relatively good condition. It was attached to the keel by

means of tapered hardwood pegs whose heads were flared to a diameter of 1.2 cm

at the bottom surface of the shoe; they are 0.87 cm in diameter in the center of the

piece and 0.6 cm at the keel surface. Although these fastenings were driven at

varying angles, preservation was not sufficient to determine fastening patterns

and spacing.

In Figure 4 the keel is shown to be straight: that is, it follows a level

baseline. Preliminary reconstruction suggests a straight keel, although subsequent

research may well reveal the presence of a longitudinally curved, or rockered,

keel. Excavations of other ancient vessels, along with contemporary illustrative

material, establish the likelihood of a rockered bottom on a boat such as this. At

present the keel is somewhat distorted and is cracked at several locations.

The lower part of the sternpost curvature begins with the same dimensions

as the keel. In the middle of strake 2 the chamfered upper edge gradually changes

into a rabbet to seat the after ends of the planks. Thirty cm below the top of the

hull it is shaped as indicated in the cross-sectional drawing in Figure 5. At the top

of the hull, the fore-and-aft dimension of the post is reduced; whatever shape it

assumed above this point was probably decorative. Nothing is known about the

boat's stem or bow construction at present.

Steffy - 10

PLANKING

There are eight strakes of bottom planking on the port side of the hull and

seven on the starboard side. Only four of them reach the sternpost rabbet on each

side. In addition, each side has a two-piece wale, a single side strake, and a

caprail. Figure 4 shows a side view of the port planking as found and Figure 6

illustrates the port side of the hull in section.

Most of the bottom planking is now between 1.7 and 2 cm thick, although

some thickness may have been lost because of the heat and the blast of volcanic

ash preceding the pyroclastic flow. Measurements taken at nails and protected

areas yielded thicknesses of between 2.1 and 2.7 cm, and one loose nail revealed a

distance of 2.5 cm between its head and inner concretions. I believe that these

latter measurements are more accurate indicators of original planking thickness in

the lower part of the hull. At the after end of the hull, their thicknesses were

reduced nearly a centimeter where their hood ends entered the post rabbet.

None of the strakes exceeded 23 cm at their greatest widths; strake 6A, the

extra portside strake, had a maximum width of 6 cm in the exposed areas of the

hull. Table 1 below indicates starboard planking widths at 50 cm intervals for the

areas exposed in 1983. The locations are distances from the point where the

caprail meets the sternpost rabbet. All values are in cm.

Table 1

Steffy - 11

Sta. S1 S2 S3 S4 S5 S6 S7

1 --- --- 10.2 --- --- 16.5 14.3

2 --- 16.2 15.8 --- --- 16.8 15

3 6* 16.2 17.6 4 --- 16.5 15

4 14 16.1 16.7 11.1 --- 17 16

5 16 17.1 16.4 11.6 7.7 17.2 16.3

6 17 16 17.4 12.8 12.7 17.8 17.2

7 16.5* 17.5 17.6 14.9 16.8 17.5 18

8 15.4* 17.4 17 17.5 19.5 16.8 18

9 19* 16.8 18 18.5 21.3 17 18.8

10 18* 16.3 18.2 20 22.8 17.5 **

11 13.2* 17 17.6 21.1 ** ** **

12 9* 17 14.7 ** ** ** **

* garboard edge is broken along keel

** not cleared of overburden or damaged

Probably all bottom strakes were single planks, since no scarfs or butts

were found on the exposed hull surfaces. Strakes 1, 4, 5, and port strake 6A did

not reach the sternpost rabbet.

The hull planks were edge-joined to the keel and to each other in the

classical fashion by means of pegged mortise-and-tenon joints (Figure 7). Joint

spacing was inconsistent, although measurements taken between the centers of

about 200 tenon pegs resulted in an average spacing of 13.3 cm. The smallest

Steffy - 12

space between joint centers was found near the lower aft end of the port garboard

(at frame 6), where two sets of joints were centered 5.5 cm apart. The greatest

distance between joint centers was 25.7 cm along the upper edge of starboard

strake 7, just aft of the through-beam. There was no concentration (reduced

spacing) of large groups of joints in any particular area. However, the above

tabulations probably represent fewer than one-fourth of all the mortise-and-tenon

joints in the hull.

The few mortises which could be examined averaged 5.1 cm in depth, 5.2

cm in width, and 0.4 to 0.5 cm in thickness, although five mortises along a

detached plank edge in the port bow were only 4.5 cm wide. The only exposed

tenon that could be considered unaltered by carbonization was 4.5 cm wide in a

5.8-cm-wide mortise. It was 0.5 cm shorter than the 5.2 cm mortise depth (Figure

7) but fit tightly in thickness. All tenon pegs were tapered and appeared to have

been driven outward from the inner planking surfaces. They were unusually

large for such small joints, having outer diameters (most were multi-sided rather

than round) varying from 0.6 cm to 1 cm, with an average outer diameter of 0.9

cm. Inner surface diameters, measured on a few detached pieces of planking,

averaged 1.8 cm. Pegs were centered 1.5 cm from seams on the average; many

were not central in their mortises.

The wales were complex, carefully-made strakes (Figure 8). Their lower

edges matched strake 7 in thickness, but 3 cm or less above this seam, depending

Steffy - 13

on location, the wale thickness increased to nearly three times that of the bottom

strakes. The wale was 6 to 9 cm wide, and its cross-sectional angles changed

constantly with hull curvature.

Outer pieces were nailed to the wales at intervals yet to be determined.

Although they appear to have served as rubbing pieces, they added considerable

longitudinal strength as well. Their thicknesses varied from 3.6 to 5.7 cm. A

vertical diagonal scarf was found in the starboard outer wale near the middle of

the hull.

A side plank of approximately the same thickness as the bottom strakes

separated the wale and the uppermost piece, the caprail. The caprails had widths

ranging from 2.8 to 3.5 cm and a thickness of about 6.1 cm. No mortise-and-

tenon joints were observed in association with the caprail, although near the stern

a nail was driven through it into the side strake below. Another nail appeared to

attach it to a frame top about two meters forward of the stern. Both of these

fastenings were found on the starboard side.

The side planks (and probably the caprails) terminated at a point about 3

m forward of the sternpost; they did not reappear within the excavated area, a

distance of more than 2 m. The planking ends appeared to be framed or braced

where they terminated, indicating a deliberate opening here. Most likely this was

a recessed area for oars as seen on some Roman iconography, although further

excavation might reveal another purpose.

Steffy - 14

FRAMES

Little is known about the frames, since most of them were obscured by the

overturned hull. They were attached to the planking by an irregular pattern of

bronze nails and treenails. On a typical 21-cm-wide plank there were two nails

and two treenails per frame; on occasion, only a single nail or treenails was used.

Most nails had head diameters of 1.7 to 2.2 cm (figure 9). One nail fastening the

wale to a frame near the stern had a shaft 0.9 cm square, while a broken planking

nail had a round shaft with a diameter of 1 cm. Nails were not clenched over

inner frame surfaces, as was sometimes done in ancient construction. Treenails

ranged in section from square to round, although most were approximately

hexagonal and averaged 1.5 cm in diameter. Treenails were driven completely

through the frames, but no wedges were found in their ends.

One detached frame fragment and the exposed upper end of another had

sided dimensions of 5 cm and were molded 4.5 cm. Probing between seams

indicated similar dimensions. Just forward of the through-beam, however, a

portside frame continued beyond the caprail and into the pyroclastic flow; it was

sided about 5 cm and molded about 8.5 cm. At the midship termination of the

portside plank and caprail there was a frame whose molded dimension was at

least 7.5 cm. The significance of these apparently special frames will not be fully

understood until excavation is completed.

Steffy - 15

Although the framing pattern was not directly visible, its arrangement

could be interpolated from the rows of external fastenings. Undoubtedly this

framing system was similar to other excavated hulls from the classical period

where floor timbers alternated with paired half-frames (Steffy 1985:84-87). Floor

timbers, as indicated by their fastenings, had arms extending to strakes 4, 5, or the

lower edge of strake 6. Half-frames usually began near the centers of the

garboards and extended to the caprail. What appeared to be a double frame (or at

least double rows of fastenings) coincided with the termination of the side planks

and caprails. One of them may have been the oversized frame mentioned earlier.

A meter or so forward of this double frame were two pairs of adjacent floor

timbers spaced 26 cm apart.

At a broken area on the port side near amidships, a small portion of ceiling

planking could be seen. It was about 2 cm thick and two nails attached the visible

section to a frame. It appeared to line the inside of the hull to a height of about 40

cm below the wale.

THROUGH-BEAM

Exactly one meter forward of the point where the caprail met the stern, a

beam projected through each side of the hull for a distance of 43.5 cm beyond the

wales (Figure 10). It rested on the upper wale surfaces and was 8.1 cm high and

6.1 cm fore-and-aft at the side plank, tapering to 7.5 by 5.4 cm near its rounded

Steffy - 16

outer ends. Nails were driven through the wale and into the beam to fasten it;

probably it was nailed to the frames that crossed its forward edge as well. A

charred rope, about 1 cm thick and of coarse lay, passed beneath the beam and

into the fill. Because of its obvious fragility, this rope was left untouched to await

conservation.

EXTERIOR ODDITIES

Several curiosities found on the exterior of the hull in 1983 remain to be

confirmed. On both sides of the hull, patch tenons (the name was first given to

similar tenons on the Kyrenia ship because they resembled patches) were noted

aft of the through-beam. One was found above the 3/6 seam on the starboard

side, just aft of the bulkhead beneath the steering beam (Figure 11). Three were

found in a row at the same location on the port side, spaced about 12 cm between

centers, and two more were recorded in the port 3/6 seam just forward of the

bulkhead (Figure 12). Such tenons were found on the 4th-century B.C. Kyrenia

ship, where they were used to attach replacement planking (Steffy 1985:84,97).

Whether or not they represent repairs here cannot be confirmed until the inside of

the hull can be examined. It should be noted, however, that on the Kyrenia ship

patch tenons only occurred on exterior surfaces where they coincided with

frames; otherwise, the square heads were located inside the hull. On the

Herculaneum boat, they were found externally between the frames. These joints

Steffy - 17

also differed from their Kyrenia counterparts in that there was a locking peg on on

the patch side of the seam.

Metal fragments, perhaps the remains of bronze staples or a cleat for a

rudder pendant, were found at the aft end of port strake 4 and above the port 3/6

seam just aft of the bulkhead (Figure 12). Only the shafts remained, and these

were rectangles 0.8 x 1.7 cm. At the end of strake 4, however, traces of bronze

survived in a slight depression to suggest that these were the shafts of a 1.7 cm

wide, 6.5 cm long staple.

Yet another curiosity, perhaps an indicator of repair or alteration, should

be mentioned. A 47 cm long, 7 cm wide piece of plank was inserted into the

lower edge of port strake 7 about 70 cm forward of the through-beam (figure 13).

A similar insert, but only 32 cm long, was found at the same location on the

starboard side. Two unexplained nail heads were found in the bottom of the port

wale (but not the starboard) above this inserted piece. Although these inserts may

have been used to close a hole used for some previous assignment, examination of

the interior of the hull will be necessary to clear up the matter.

ANALYSIS

Eventually the Herculaneum boat will be moved to a museum where

conservators will complete their work and the separated sections of the hull can

be joined. Only then will we be able to project reliable hull lines and answer

Steffy - 18

some of the nagging questions about the construction and operation of this small

Roman vessel. But several features are already clear, and others need to be

pondered while we await the project's completion.

The most important question concerns the boat's purpose. Was it a

tugboat, a fishing vessel, or simply a pleasure craft at the disposal of wealthy

patrons of the nearby suburban thermae? Certainly it was not a coastal cargo

vessel or lighter; it seems too shallow and lightly built for that. Undoubtedly it

was intended to be primarily a rowed vessel; the suggested open area, low

freeboard, relatively narrow beam, and what appears to be a poor lateral

resistance for sailing all point to oars as the primary means of propulsion. This

does not mean the vessel could not also have been sailed, however. Those two

closely-spaced floor timbers in the middle of the hull most likely provide the

extra strength required to support the mast step for a square sail. Such a sail

might have been used only to arrive at a work station or to rest the oarsmen. For

these reasons I suspect one of two functions for this vessel--that of a tugboat or of

a fishing vessel used in large seining operations.

ADDENDUM--THE KINNERET BOAT

In the spring of 1986 I examined an extensively preserved boat discovered

along the shore of Lake Kinneret (Sea of Galilee) in Israel (Wachsmann et al

1990). Archaeologists removed the hull intact and immediately placed it in a

Steffy - 19

specially-constructed conservation tank, where it will be preserved in a solution

of polyethylene glycol over the next several years. Because rising Galilee waters

did not permit a thorough in situ study, a more exhaustive analysis can be done

only after conservation treatment is complete. Enough is known, however, to

make some interesting analogies between the Kinneret and Herculaneum boats.

They are more or less contemporary, the Kinneret boat being tentatively dated

from the mid-first century B.C. to about the time of the eruption of Vesuvius.

Both are approximately the same length--the Kinneret boat's length was about 8.2

m--and both were constructed shell-first with similarly-spaced edge joinery and

frames. There were other similarities as described below but, so far as design and

fabrication are concerned, the analogy must end there. Comparing the

Herculaneum boat to the Kinneret boat is like comparing a sleek sports car to a

delivery truck.

The Herculaneum boat was built by a well disciplined boatwright. There

is a lot of good joinery work in evidence, and construction as a whole indicates

plenty of pride and expertise. Our builder obviously had an abundance of good

materials available, too. Planks are broad and, as far as can be determined, run

their full lengths without scarfs. The planking plan is ideal for such a hull. Nails

are bronze and are made well. Those parts of the frames which were visible were

relatively straight and of constant dimension. The wales and sternpost were

works of art; one can only appreciate the expertise required to shape such wales

Steffy - 20

and fit them to adjacent planks with several dozen mortise-and-tenon joints along

each carefully fitted seam. The design is pleasing, too, even in this carbonized,

broken state. This was a strong, graceful hull, a fine example of boatbuilding

expertise in the heart of the empire.

Apparently things were different in the provinces. Not that the boatwright

who constructed the Kinneret vessel was an inferior craftsman. Indeed, I would

say that he was every bit as capable as his counterpart in Herculaneum. It was

just that he had to do so much with so little, and the nature of Galilee maritime

activities probably demanded a much less aesthetically pleasing hull (Wachsmann

et al 1990:29-47).

The Kinneret boat was deeper, broader, and far less graceful (figure 14).

We believe that this hull was used for fishing, freighting, or whatever else was

required of it. Its bottom was relatively flat, it had an unusually sharp turn of the

bilge for this type of construction, and its sides were much deeper than those of

the Herculaneum boat. The wales, beams, upper decks, stem, and sternpost were

all gone, cannibalized for use on a newer boat we believe, but much of the

contrast lies in the planking and frames. The cedar planks of the Kinneret boat

were frequently scarfed to make up strakes, and they were narrow and less well

arranged than on the boat at Herculaneum. The frames were noticeably different,

too, a statement we can make solely on the basis of nail patterns and examination

of a few fragments. The Kinneret builder had to use extremely crooked oak

Steffy - 21

frames to arrive at anything remotely resembling the desired curvatures. In some

cases the frames did not touch the planking and always they were crooked and

crude. Fastenings were solely of iron; there were no treenails or bronze

fastenings. Even the staples--this vessel was repaired with staples--were made of

iron.

When conservation of both hulls is completed and more thorough studies

of them are possible, they should provide the basics of some interesting

technological comparisons between Rome and her provinces.

Steffy - 22

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I am grateful to Giuseppina Cerulli Irelli, Soprintendenza Archaeologica

di Pompei, for permission to record and study the exterior of the boat as well as

for her cooperation and thoughtfulness. Thanks also go to Giuseppe Maggi,

director of Ercolano Scavi at the time, who was especially enthusiastic and

helpful. I appreciate the friendship and instructions in vulcanology and

anthropology by Haraldur Sigurdsson and Sara Bisel, the hospitality of Walter

Silva, and the assistance and cooperation of the staffs of Ercolano Scavi and the

National Geographic Society. I am especially grateful to the National Geographic

Society for providing the financial support for this fieldwork, and to the Institute

of Nautical Archaeology and Texas A&M University for funding and facilities for

laboratory studies.

Steffy - 23

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Sigurdsson, H.; Carey, S.; Cornell, W.; & Pescatore, T.

1985 The eruption of Vesuvius in A.D. 79. National Geographic Research

1(3):332-387.

Steffy, J. R.

1985 The Kyrenia ship: an interim report on its hull construction. American

Journal of Archaeology 89:71-101.

Wachsmann, S.; et al

1990 Excavations of an ancient boat in the Sea of Galilee (Lake Kinneret).

Atiqot (English Series) XIX. The Israel Antiquities Authority, Jerusalem.