Interactions between ancient Herculaneum and modern Ercolano

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

1 -

download

0

Transcript of Interactions between ancient Herculaneum and modern Ercolano

International Conference “Sustainable Environment in the Mediterranean Region: from Housing to Urban and Land Scale Construction”, Naples 12-13-14 February 2012

1

INTERACTIONS BETWEEN ANCIENT HERCULANEUM AND MODERN

ERCOLANO

Luigi Mollo1, Paola Pesaresi

2, Christian Biggi

3

1Dipartimento di Ingegneria Civile, Seconda Università di Napoli, Via Roma 29, 81031 Aversa (CE)

2Herculaneum Conservation Project, Scavi di Ercolano, Via Mare 44, 80056 Ercolano (NA)

3Herculaneum Centre, Villa Maiuri, Via IV Orologi 23, 80056 Ercolano (NA)

Abstract

Archaeological sites throughout the Mediterranean are important cultural tourism attractions and catalysts for development.

Inevitably, however, development either leads to the growth of the modern town around sites or to the modern being sacrificed in

order to excavate and utilize the heritage. The issue that needs to be faced today is the relationship between these two worlds that

differ in structure and purpose but which are linked by their co-existence and which interact in the context of development.

Approaches which focus either only on site management or instead on modern development risk marginalizing either the site or

the town. Herculaneum in the Bay of Naples, Italy, is a valuable case study for understanding the problems that can result from

parallel, yet independent, development of the ancient and modern towns.

The Herculaneum Conservation Project and the Herculaneum Centre, together with the Civil Engineering Department of the

Second University of Naples, have undertaken urban research in order to understand how to improve interaction between the

archaeological site and the modern town. Particular emphasis has been placed on Via Mare, an 18th C residential district of some

25.000 square metres, which connects the historic centre of modern’ ‘Ercolano’ to the sea and directly abuts the archaeological

site on its north and eastern edges. An array of social, economic and environmental problems have threatened the survival of this

urban area and its close-knit community in recent decades. However, these threats can perhaps be translated into opportunities if

urban regeneration is approached in an integrated way. This paper presents the initial results of this work.

Keywords: urbanism, archaeology, conservation, participation

1. Introduction

The modern town of Ercolano lies immediately south of Mount Vesuvius, near to Naples. It was called Resina until

the 1960s when its name was changed to Ercolano, in honour of the Roman city of Herculaneum, which had been

destroyed by the eruption of AD 79 and over which Ercolano is built. This name change took place at the end of a

long excavation campaign under the archaeologist Amedeo Maiuri (1927-1958) that uncovered about a fifth of the

Roman town, equivalent to about 45,000m2, which has become the archaeological site of Herculaneum [1]. The

process which led to the rediscovery of the ancient town and its presentation to international visitors took place in

parallel to the expansion of the modern town, which, thanks to the post-war economic boom, included an

exponential population increase until it became the ninth most densely inhabited town in the Naples area and one of

the most populous towns in all Italy. These two parallel processes began under a policy of participation, which was

partly spontaneous and partly encouraged by local institutions. However, gradually over time the two separated

leading to a loss of the benefits of a more participatory approach and causing a growing physical and social division

between the two towns. Today Herculaneum is largely unknown by the local community who consider it to be

inaccessible and the site has become a sort of separate town within the town. The site lives its own life due to an

autonomous management system which does not involve local institutions [2] and due to an international community

that has tried to safeguard it and which every year leads to the arrival of hundreds of thousands of visitors [3]. At the

same time, however, ancient Herculaneum which was lost and rediscovered thanks to an enormous human, cultural

and economic investment, has risked being lost again due to indifference and hostility of the places and people

which surround the site. At the same time, modern Ercolano suffers from the urban and social damage caused by the

protracted process of separation. The future sustainability of the archaeological site is, therefore, intrinsically linked

to the area that surrounds it and only the coherent further development of the ancient and modern towns together can

both guarantee heritage conservation and also contribute to social and economic wellbeing. Since 2001 when the

Herculaneum Conservation Project [4] was launched, there has been an attempt to use partnerships between local

institutions, heritage agencies and international partners to establish a process of conservation, maintenance and

sustainability of the archaeological site, based on broadening participation, by using an opposite approach to that

normally taken: one that goes from the international community to the local community. This research stems from

this collaboration and focuses on understanding the local dynamics of the historic centre of Ercolano, where the site

is located, and on their potential influence in the development of integration processes between the ancient and

modern towns.

2. Defining the study area

International Conference “Sustainable Environment in the Mediterranean Region: from Housing to Urban and Land Scale Construction”, Naples 12-13-14 February 2012

2

The modern town of Ercolano

stretches along a narrow north-south

strip from Vesuvius to the sea (8,5

km). The main routes run

perpendicularly to that strip, while

there are only a few winding north-

south routes [5].The historic centre

lies around the so-called Golden

Mile [6], one of the transversal axes

that is known today as Corso Resina

and which runs along the north side

of the archaeological site. The

archaeological site of Herculaneum

lies to the south of Corso Resina.

Access to the site is in line with the

road that connects the local train

station with the entrance to the

archaeological area. The historic

town centre is the most populated

area in the town’s territory, where

average population densities are

among the highest in Europe, with

many families who live on the

poverty line if not under it, and with

the added issue of many young

families who are attracted there by

low rents. The urban fabric is largely in a state of decay and building works without planning permission are

common, in particular extensions for increasing residential space. Decay and illegal building modifications are

particularly noticeable along the main roads, where, during this research, it became clear that 72% of the buildings

are illegally modified in some way and 44% of them are in an advanced state of decay. Moreover, the historic centre,

as was noted in a study carried out by the town council’s Urban Herculaneum programme [7] in the period 2000-

2006, is undergoing a phenomenon of ‘peripheralization’ with the continual decentralization of shops and

businesses. This phenomenon is also a result of the policy of closing the archaeological site off from the town and

the low level of tourism development based on the site itself. Almost all shops are found along the main roads, in

particular on Corso Resina, while the side streets have almost none, even if they are key traffic routes.

Despite the decay phenomena and economic impoverishment, the historic centre enjoys a majority of eighteenth-

century buildings, among which there are many important structures including 22 of the Vesuvian Villas, that are

mainly found along Corso Resina. This road is the main route that has maintained greatest vibrancy and is the

equivalent of the typical ‘piazza’ of a historic centre, in terms of its ability to attract people. It is this economic,

commercial and social vibrancy that contrasts strongly with the side streets that cross it.

2.1 The Via Mare neighbourhood

One of the streets that crosses Corso Resina is Via Mare, the road that is the subject of this research. The Via Mare

that can be found on maps from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries as Vico Mare (not ‘road’ but ‘lane’), is

certainly an older route which connected Corso Resina to the sea. The road, narrow and paved, runs steeply down to

the south, connecting the historic town centre with the sea. The buildings that give onto the street are mostly

eighteenth century, as can be seen by the fact that they already appear on the 1775 map by the Duke of Noja, and

they are laid out around structures known as ‘ramps’ which are an architectural typology that overcome the drop in

ground level to the south and west with a system of ramped arches and embankments. Overall the buildings are in an

advanced state of decay, due to the chronic lack of maintenance. Since the nineteenth-century and twentieth-century

excavations, the eastern side of Via Mare has been expropriated and the buildings demolished. Thanks to Law 640 of

9 August 1954 the clearance area included the remaining area that gives onto the archaeological site and under

which the Roman forum lies. That which is today known as the Via Mare neighbourhood consists of the buildings at

the northern end of the road, where there are numerous residential buildings, even if they are all on the west side, as

the archaeological park lies to the east, which is divided from the road by an imposing boundary wall and a drop of

more than 15m down to the site. Residents’ homes do not just look onto Via Mare, but also onto four ‘ramps’

leading to the west, which are steep lanes or stairways. Data collected for 2008 reveal that there are just under 400

people who live in the Via Mare neighbourhood, residents have an average age of 33 years and there are a large

number of women with school-age children [8]. There are no businesses in the area and there is currently only one

shop. There is a chronic lack of parking spaces, ineffective infrastructures (street lighting, sewers/drainage,

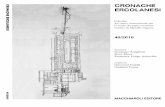

Figure 1. Satellite image of the area. (Image: Google Earth)

International Conference “Sustainable Environment in the Mediterranean Region: from Housing to Urban and Land Scale Construction”, Naples 12-13-14 February 2012

3

electricity and water) and there are no green spaces or recreational areas. In the face of this urban decay, fortunately

the residents have a strong sense of belonging and with the help of the Herculaneum Centre they are creating a

residents’ association. Since 2007, when the town council carried out the demolition of collapsing buildings in order

to guarantee public and private safety, the neighbourhood has seen further architectural and urban changes with the

disappearance of another section of the buildings on its western front. However, the cleared area has not yet become

useable by the local community, but unfinished works means that the site has remained fenced off.

The Via Mare residents, like the rest of the local community, do not have any financial or other incentives to visit the

site, such as reduced ticket prices or events. Only the local schools, thanks to free entry for children organize visits to

the site, and these have recently taken on an added dimension thanks to a initiative organized by the Herculaneum

Centre to provide new material to the schools and which has encouraged their pupils to become ‘ambassadors’ for

their heritage and its protection through a process of promoting greater understanding and sense of ownership [9].

3. The relationship between the modern town of Ercolano and ancient Herculaneum

Historically the periods in which modern Ercolano has thrived have coincided with those of greatest dialogue

between the site and the town, the latter encompassing not just the urban fabric but also its social and cultural aspects

(for example, the Bourbon monarchy’s enormous interest in the site or the Grand Tour visitors). How to connect the

site and the town has been an unresolved issue since early excavation works. This problematic relationship became

worse as the excavation area was extended. From the start of this epic period of excavation, Amedeo Maiuri had

tried to deal with this problem, paying considerable attention to how to relate to the modern town and its residents,

even going as far as to launch collateral initiatives that added land to the coastline in restitution for the area

expropriated for archaeology [10]. Moreover, collective participation in the archaeological campaigns, with many

Ercolano residents involved in the excavation and restoration works, helped create a sense of social involvement, as

has been understood through an oral history project organized by the Herculaneum Centre which also revealed the

close ties this also created between the site, Via Mare and other key points in the town, such as the local market [11].

Half a century later and the oral history project is also attempting to foster intergenerational dialogue between

Ercolano’s senior citizens and the younger generations so that the memory of this enormous undertaking and the

community’s contribution to it will not be forgotten and that a sense of belonging will be reinforced. Afterwards, for

a series of problems that range from the management dynamics of the newly-created site to the heritage authority’s

increased need for security, every portion of land that passed from the town to the archaeological park tore into the

urban and social fabric. From the excavation of the Decumanus Maximus to that of the ancient shoreline in the

1980s and to the Villa of the Papyri [12] excavated in the 1990s, attention to the physical and social boundaries

between the two towns was drastically reduced, while barriers, fencing and boundary walls increased. The limes of

the archaeological area has gradually become a fortified boundary that separates, isolates and protects from that

which is outside. The edges of site were cut into increasingly vertical escarpments in the attempt to gain every

possible metre, maintenance routes along the escarpments were forgotten and partially-excavated archaeological

structures were abandoned because they were too complex to preserve. At the same time, while the heritage

authority changed management model and the contribution of the Ercolano residents decreased, the site underwent a

progressive closure into itself. New models of tourism and socio-economic changes in the town’s population also

had an effect, with exponential increases in population density and significant poverty levels, as did growing levels

of organized crime. Until the early years of the twenty-first century, the archaeological site was managed and visited

in complete isolation from its surroundings. Physical barriers such as boundary walls even deprived local residents

of the view of what should have been considered their heritage, while visitors to the site had little or no contact with

the modern town, and the heritage authority had no dialogue with other local institutions. Local institutions and

community did not participate in site management on any level.

International Conference “Sustainable Environment in the Mediterranean Region: from Housing to Urban and Land Scale Construction”, Naples 12-13-14 February 2012

4

Early on in the twenty-first century, there was a growing need for

the local institutions to collaborate in the development of

Ercolano’s tourism, a greater attention to policies for enhancing

and safeguarding the urban area (in particular, with the creation

of the Urban Herculaneum programme) and the creation of

forums for dialogue, such as the Herculaneum Centre, which

have all led to a changed scenario in the last few years. In

addition, this has highlighted how much the sustainability of a

site such as Herculaneum is closely tied to its relationship with

the surrounding town, and how the potential economic, social and

cultural development of the town must depart from its

relationship with its heritage. The limes of the archaeological area

is beginning to become a limen. The word limen, in fact, though

similar to limes and also related to the concept of a boundary,

properly means ‘threshold’ and in a figurative sense, the

beginning of something. In fact, if limes is usually understood

conceptually to mean a sort of terminus, limen is associated

instead with a principium: it is the threshold, that which allows

entry and, therefore, can be a means of relationship, meeting and

communication. The limes is exclusive, the limen is inclusive.

This evolution in approach, which since 2006 has led to various

collaborative initiatives, such as obtaining co-financing for a new

site entrance and ticket office, along with the public opening of

the avenue between the old and new entrances, has also created

the conditions for a series of ambitious projects for the edges of

site. In the case of a new park at the entrance too, which was

created with European funding in the context of the 2000-2006

Regional Operational Programme for Campania, the heritage

authority signed an agreement with the town council for its

management: in this way the town benefits from new gardens in

the heart of the historic centre with views of the archaeological site. At the same time, thanks to the Herculaneum

Conservation Project the archaeological site’s conservation conditions were brought back to manageable levels with

the consequent reopening of many areas to the public. Since 2006, the Herculaneum Conservation Project’s efforts

have been supported by a sister project, the Herculaneum Centre [13], which also includes the town council among

its partners, and whose objectives include that of improving the relationship between the local community and its

cultural heritage.

4. Research on the Herculaneum’s western limen and its enhancement

The modern road of Via Mare and its surrounding neighbourhood is one of the main routes connecting the modern

and ancient towns. Around this route it seems appropriate to promote some form of urban development that places

the archaeological site back within the town and also the sustainable development of the agricultural areas that lie

between Corso Resina and the sea and surround the archaeological site itself. The results shared in this study are

largely analyses that will inform future phases of work. A study area was identified where the building chronology

of the structures and their state of maintenance was examined (figures 3-6). Next an evaluation was carried out of the

hierarchy of the roads and the location of business activities, along with an evaluation of green and recreational areas

(figures 7-9). This study has provided an overview that encourages and supports plans for enhancing Via Mare and

its neighbourhood as a pilot project for reintegrating the archaeological site and the historic centre and to trial

participatory activities in support of its sustainability and appreciation. In fact, the area’s potential could be

promoted in terms of social (dense population), urban (the unresolved connection between the town and the sea),

architectural and natural (quality of the built environment and the green agricultural areas that could be converted to

urban green spaces) issues. In particular, along Via Mare significant amounts of green space have been identified

which, correctly integrated with the vernacular architecture that is laid out around ramps, could form the basis for the

creation of a park that includes green areas (agricultural park and farm tourism), the built environment and

archaeological areas (cultural park) in a unicum which allows an integral and integrated use of the urban, cultural

and social history of Ercolano.

Figure 2. One of the ‘ramp’ buildings in

Via Mare, as seen in the mid twentieth

century. (Image: Archive of the

Soprintendenza Speciale per i Beni

Archeologici di Napoli e Pompei)

International Conference “Sustainable Environment in the Mediterranean Region: from Housing to Urban and Land Scale Construction”, Naples 12-13-14 February 2012

5

Figure 3. Right: outlined in green is the area in consideration for this study (Image: Google Earth); left: the

chronology of the built environment (Image: Antonio Ronca, Seconda Università di Napoli)

Figure 4. An example of the typological analysis of a building in Via Mare. (Image: Antonio Ronca - Seconda

Università di Napoli)

International Conference “Sustainable Environment in the Mediterranean Region: from Housing to Urban and Land Scale Construction”, Naples 12-13-14 February 2012

6

Figures 5-6. Mapping of the decay of the buildings. (Images: Antonio Ronca –Seconda Università di Napoli)

.

Figures 7-8. Left: the hierarchy of roads; right: green areas. (Images: Antonio Ronca – Seconda Università di

Napoli)

Figure 9. Functions of buildings and areas (Image: Antonio Ronca – Seconda Università di Napoli)

5. Conclusion

International Conference “Sustainable Environment in the Mediterranean Region: from Housing to Urban and Land Scale Construction”, Naples 12-13-14 February 2012

7

The research carried out so far has highlighted how the north-west limen of the archaeological site, while bordering

an area of serious urban and social decay, contains all the potential elements for creating genuine visual and physical

access to the site.

In particular, extensive privately-owned green areas were discovered (hidden from view by the particular topography

of the area), containing greenhouses and old agricultural buildings, which have the potential to become the core of

an urban park/agricultural public park with close links to the archaeological site and the Vesuvius National Park.

The area’s built fabric is unique in the town’s building history and could be perfectly integrated along with the

archaeological site into a cultural park. Within these buildings it would be possible to encourage small businesses

and trades tied to cultural and natural tourism. Such activity would be not only be sustainable from a commercial

point of view but, together with urban improvements, would help readdress the social, economic and environmental

weaknesses which today forbid this neighbourhood to turn threats into opportunities and become a sustainable

community taking the best of the surrounding urban fabric, the archaeological site included, and giving back as

much as it gives.

References

[1] Camardo, D. (2006) Gli scavi ed i restauri di Amedeo Maiuri. Ercolano e l’esperimento di una città museo.

Ocnus: Quaderni della Scuola di Specializzazione in Archeologia 14: 69-81.

[2] Guzzo, P.G. (2003). Pompei 1998-2003: l’esperimento dell’autonomia

[3] See the data in the SANP official web site: http://www.pompeiisites.org/Sezione.jsp?titolo=Given

Visitors&idSezione=1841&idSezioneRif=1703

[4] The Herculaneum Conservation Project (HCP) is an innovative public/private initiative to safeguard and

conserve, to enhance, and to advance the knowledge, understanding and public appreciation of the Archaeological

Site of Herculaneum. The partners of this initiative are: Soprintendenza Speciale per i Beni Archeologici di Napoli e

Pompei (SANP), the British School at Rome (BSR) and Packard Humanities Institute (PHI). For further information

see: http://www.herculaneum.org

Camardo, D. (2007) Archaeology and conservation at Herculaneum: from the Maiuri campaign to the Herculaneum

Conservation Project. Conservation and Management of Archaeological Sites 8.4: 205-214.

Thompson, J. (2007) Conservation and management challenges in a public-private partnership for a large

archaeological site (Herculaneum, Italy). Conservation and Management of Archaeological Sites 8.4: 191-204.

Pesaresi, P. & Martelli Castaldi, M. (2007) Conservation measures for an archaeological site at risk (Herculaneum,

Italy): from emergency to maintenance. Conservation and Management of Archaeological Sites 8.4: 215-236.

Pesaresi, P. & Rizzi, G. (2007) New and existing forms of protective shelter at Herculaneum: towards improving the

continuous care of the site. Conservation and Management of Archaeological Sites 8.4: 237-252.

[5] Buondonno, E. (2007) Indirizzi urbanisitici per la città di Ercolano. Ercolano: Comune di Ercolano.

[6]Masterpieces of the late Baroque period appear one after another along the ancient Via Regia which leads from

Naples to Portici

[7] The URBAN Herculaneum program, launched in 1994 and active until the year 2009, aimed at enhancing the

economic readjustment and the community sense of sharing the area of historic centre. The project focused on the

development of physical, economic and environmental resources by applying the innovative concept of “active

protection”, which implies a local common sense of welfare.

[8] Manzo, L. (2009) Indagine demografica di Via Mare e le sue rampe. Rapporto di stage. Ercolano: HCP.

[9] Matafora, P. et Vignola, L. 2009. Insegnamento del patrimonio culturale: una nuova opportunità per formare

cittadini responsabili. In Strabismo Umanitario -un occhio al vicino ed uno al lontano, Cronache di Pace. UNICEF -

Comitato Regionale Campania.

[10] Thanks to the low n. 640 (august 9th, 1954) most of the area located over the ancient Forum of Herculaneum

was expropriated, the buildings demolished and excavated, with funds by the Cassa del Mezzogiorno, a development

agency active in South Italy. Eighty families were moved to south in new buildings built on purpose by the Italian

Agency for popular Houses.

[11] Matafora, P. 2010. Storia orale, un impegno archeologico. Associazione Italiana di Storia Orale, 2 March 2010.

http://www.aisoitalia.it/2010/03/storia-orale-un-impegno-archeologico/ (accessed 14 November 2010).

[12] Quilici, V. and Longobardi, G.(2007): Ercolano e la Villa dei Papiri: archeologia, città e paesaggio.

[13] The Herculaneum Centre was created by the Associazione Herculaneum whose partners are the Soprintendenza

Speciale per i Beni Archeologici di Napoli e Pompei, the Comune di Ercolano and the British School at Rome; see

Biggi, C. & Court, S (2009) Oltre il sito archeologico: da un progetto di conservazione ad un centro studi. In

Coralini, A (ed.) Vesuviana: archeologie a confronto. Proceedings of the international conference, Bologna, 14-16

January 2008. Bologna, Edizioni Antequem: 277-288.