The Birth of Mediterranean Culture: Claude Lorrain’s Port Scenes Between the Apollonian and the...

Transcript of The Birth of Mediterranean Culture: Claude Lorrain’s Port Scenes Between the Apollonian and the...

MITTEILUNGENDES KUNSTHISTORISCHEN INSTITUTESIN FLORENZ

LVI. BAND — 2014

HEFT 1

Littoral and Liminal SpacesThe Early Modern Mediterranean and Beyond

MITTEILUNGENDES KUNSTHISTORISCHEN INSTITUTESIN FLORENZ

_ 3 _ Hannah Baader - Gerhard WolfA Sea-to-Shore Perspective. Littoral and Liminal Spaces of the Medieval and Early Modern Mediterranean

_ 17 _ Çigdem KafesciogluViewing, walking, mapping Istanbul, ca. 1580

_ 37 _ Stephanie HankeAn der Schwelle zwischen Stadt und Meer: Frühneuzeitliche Uferpromenaden in Messina, Palermo und Neapel

_ 59 _ Itay SapirThe Birth of Mediterranean Culture: Claude Lorrain’s Port Scenes Between the Apollonian and the Dionysian

_ 71 _ Brigitte SölchArchitektur bewegt – Pugets Rathausportal in Toulon oder Schwellenräume als ‘sympathetische’ Interaktionsräume

_ 95 _ Joachim ReesAuf schwankendem Grund. Visuelle Konstruktionen des Litorals in den Bildkünsten der Niederlande und Japans um 1600

_ 113 _ Peter N. MillerFrom Spain to India Becomes A Mediterranean Society. The Braudel-Goitein ‘Correspondence’, Part II

Redaktionskomitee | Comitato di redazioneAlessandro Nova, Gerhard Wolf, Samuel Vitali

Redakteur | RedattoreSamuel Vitali

Editing und Herstellung | Editing e impaginazioneOrtensia Martinez Fucini

Kunsthistorisches Institut in FlorenzMax-Planck-InstitutVia G. Giusti 44, I-50121 FirenzeTel. 055.2491147, Fax [email protected] – [email protected]/publikationen/mitteilungen

Graphik | Progetto graficoRovaiWeber design, Firenze

Produktion | ProduzioneCentro Di edizioni, Firenze

Die Mitteilungen erscheinen jährlich in drei Heften und können im Abonnement oder in Einzelheften bezogen werden durch | Le Mitteilungen escono con cadenza quadrimestrale e possono essere ordinate in abbonamento o singolarmente presso:Centro Di edizioni, Lungarno Serristori 35I-50125 Firenze, Tel. 055.2342666, Fax 055.2342667,[email protected]; www.centrodi.it.

Preis | PrezzoEinzelheft | Fascicolo singolo: € 30 (plus Porto | più costi di spedizione)Jahresabonnement | Abbonamento annuale: € 90 (Italia); € 120 (Ausland | estero)

Die Mitglieder des Vereins zur Förderung des Kunsthistorischen Institutes in Florenz (Max-Planck-Institut) e. V. erhalten die Zeitschrift kostenlos. I membri del Verein zur Förderung des Kunsthistorischen Institutes in Florenz (Max-Planck-Institut) e. V. ricevono la rivista gratuitamente.

Adresse des Vereins | Indirizzo del Verein:c/o Sal. Oppenheim jr. & Cie. AG & Co. KGaA z. H. Frau Cornelia Schurek Odeonsplatz 12, D-80539 Mü[email protected]; www.associazione.de

Die alten Jahrgänge der Mitteilungen sind für Subskribenten online abrufbar über JSTOR (www.jstor.org).Le precedenti annate delle Mitteilungen sono accessibili online su JSTOR (www.jstor.org) per gli abbonati al servizio.

LVI. BAND — 2014

HEFT 1

Littoral and Liminal SpacesThe Early Modern Mediterranean and Beyond

edited by Hannah Baader and Gerhard Wolf

____

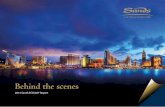

1 Claude Lorrain, The port of Ostia with the embarkation of St. Paula, 1639/40. Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado

| 59

One of the greatest Bildungsromane of Mediterra-nean culture is undoubtedly Friedrich Nietzsche’s The Birth of Tragedy.1 While nominally telling the story of how tragedy emerged from the spirit of music, and programmatically proposing a way to salvation for German culture, Nietzsche’s early text can be construed as an original contribution to the history of Mediter-ranean ideas – both the idea of the Mediterranean and the ideas that formed in that very particular geograph-ical space and which in turn shaped it.

It is perhaps unnecessary to repeat here the leading idea of that enthusiastic, visionary book. After all, even for readers who could not bear the young Nietzsche’s pathos and would stop reading almost straight away – most likely including the older Nietzsche himself – the author facilitates the approach to his text by introduc-

The BIrTh OFMedITerrANeAN CulTure

ClAude lOrrAIN’s POrT sCeNes BeTWeeN The APOllONIAN

ANd The dIONysIAN

Itay Sapir

ing in the very first sentences the binary opposition which will remain the fundamental basis for the rest of the work: the contrast between the Apollonian and the dionysian. If tragedy was born of the spiritual copulation of these two elements, the same is true for Greek culture; and can it not be said that Greece is one of the most important cradles in which Mediterrane-an culture, broadly defined, spent its infancy?

It might seem strange that Greece’s tragic culture, ac-cording to Nietzsche, stemmed from a dialectical pro-cess involving two deities if we consider Nietzschean philosophy as the antidote to hegel’s ambitious and all-pervading idea of the dialectic progression of the spirit. however, as Matthew rampley reminds us in his Nietzsche, Aesthetics and Modernity, the idea of the phi-losopher’s aversion to dialectics should be nuanced.2 In

1 Friedrich Nietzsche, The Birth of Tragedy, trans. by douglas smith, Oxford 2000 (original German ed.: Die Geburt der Tragödie aus dem Geiste der Musik, leip-zig 1872).

2 Matthew rampley, Nietzsche, Aesthetics and Modernity, Cambridge 2000, pp. 3f. see also Martha C. Nussbaum, “The Transfigurations of Intoxica-tion: Nietzsche, schopenhauer, and dionysus”, in: Nietzsche, Philosophy and the

60 | iTay SaPir |

fact, Nietzsche’s philosophizing, not least in The Birth of Tragedy, is highly dialectical, but it is based on the con-stant deferral of dialectical closure,3 and this process is best achieved through art and aesthetics.

The Apollonian and the dionysian are thus only a temporary apotheosis, and their marriage in the tragedy only one potential culmination of an ever-ex-panding abundance of dialectically structured binary oppositions. In other words, they are supposedly strict dichotomies that on a higher level of existence are revealed to be entangled and productively combina-ble. A long list of the sub-categories subsumed under Nietzsche’s Apollonian and dionysian could be made, which would include, for instance, the plastic arts ver-sus music, order versus chaos, dream versus drunken-ness, individuality versus unity, the exorcism of the terrible truth – namely, our meaningless life – versus its merciless exposition, and so on and so forth.4

In fact, it seems that Nietzsche’s oppositions pres-ent a striking family resemblance to the more ge-neric – and, as is clear from the important work of French anthropologist Philippe descola,5 historically specific – contrast of nature and culture. A simplistic identification of the Apollonian with culture’s civi-lizing enterprise in confrontation with nature’s dio-nysian sound and fury will obviously not do: it was precisely one of culture’s greatest achievements, name-ly classical Greek tragedy, that perfectly joined the two elements into a meaningful whole. This is characteristic of dialectical systems: a category combines two former oppositions in order to find itself confronted with a new, emerging ‘other’. The subsumed oppositions

continue to exist, and their productive wrestling is not necessarily – as hegel would have it – rendered useless by the higher level.

Indeed, many Nietzsche scholars have recently em-phasized the philosopher’s important stance on the question of nature and chaos on the one hand and cul-ture, art and knowledge on the other – the latter two also usefully contrasted with each other. Thus, Jürgen söring finds the prehistory of Nietzsche’s opposition between nature and art in hölderlin’s ode Natur und Kunst oder Saturn und Jupiter, where the poem is structured by the tensions between Abgrund and Höhe, Dämmerung and Tag, Bewegung and Ruhe, Anarchie and Gesetz, and Fühlen and Gestalten; to sum up, disorganized, open-ended chaos on the one hand, and cosmos on the other.6 Again, both elements are important in the dionysian and in the Apollonian, so that they are dialectically entangled rath-er than simply opposed. similarly, in her contribution to the same volume on “nature and art in Nietzsche’s thinking”, Babette Babich shows how the Nietzschean term “Chaos” is used for nature in all its contradictory senses, especially the ur-archaic, prototypical feminine aspect.7 here, in contrast to the Genesis myth of “the earth […] without form, and void” or the modern sci-entific concept of entropy, chaos is a positive, poten-tially creative term. In this sense Nietzsche’s chaos is a word for both nature and art, and the contrast between the two is nuanced or even annulled.

For Nietzsche, culture – and Mediterranean cul-ture in particular, for him perhaps the culture par excel-lence – is thus part and parcel, as well as the product, of a complex network of dialectical oppositions. surpris-

Arts, ed. by salim Kemal/Ivan Gaskell/daniel W. Conway, Cambridge 1998, pp. 36–69. 3 Rampley (note 2), p. 134. 4 A list of adjectives associated with each was provided in 1911 by Kurt hildebrandt: “sondernd, tektonisch, denkend, nüchtern, bestimmt, hell, begrenzt” for the Apollonian, and “kontinuierlich, fließend, fühlend, rauschvoll, unbestimmt, dunkel, unendlich” for the dionysian. Quoted in Nietzsche-Handbuch: Leben – Werk – Wirkung, ed. by henning Ottmann, stuttgart 2000, pp. 187f.

5 Philippe descola, Par-delà nature et culture, Paris 2005. 6 Jürgen söring, “Natur und Kunst oder dionysos und Apollo: erwägun-gen zu Nietzsches ‘physiologischer Ästhetik’ ”, in: Natur und Kunst in Nietzsches Denken, proceedings of the conference halle 2000, ed. by harald seubert, Cologne 2002, pp. 113–135. see also the contribution by Peter Pütz, “das spannungsverhältnis von Kunst und erkenntnis bei Nietzsche”, ibidem, pp. 23–36. 7 Babette e. Babich, “Nietzsches Chaos sive natura: Natur-Kunst – Kunst-Natur”, ibidem, pp. 91–111.

| CLaude LOrraiN’S POrT SCeNeS | 61

ingly, perhaps, I would claim that this point of view was shared by an artist who lived two centuries before Nietzsche, and whose artistic temperament, themes, and historical position seem the antipode to those of the German philosopher.8

In fact, to think of Claude lorrain as a pro-to-Nietzschean theoretician of the birth of Medi-terranean culture seems far-fetched given the painter’s reputation as an anti-theoretical artist catering to Bourgeois taste with peaceful, decorative and unprob-lematic compositions.9 Associating Claude with the dionysian seems particularly inappropriate; indeed, in contrast to his contemporary and neighbour Nicolas Poussin, Claude never painted dionysian themes per se. Moreover, while Claude is anything but a seven-teenth-century alter ego of Nietzsche, conversely the latter’s references to the painter are rare and under-whelming: for Nietzsche, Claude is the emblem of a Golden Age artist, calm and simple – typically Apol-lonian, so to speak – rather than expressing the fissures of an age and the tensions underlying the Mediter-ranean space, themes the philosopher was specifically interested in.10

What in Claude – and in the early Baroque cul-ture that saw his ascent to fame – can be compared

to Nietzsche’s dialectics of culture, temporarily cul-minating in the Apollonian-dionysian contrast and combination? In this article, I would like to present the case of Claude’s seaport scenes (Fig. 1) as a se-ries of pictorial essays on the birth of Mediterrane-an culture through a similar dialectical process. each of these scenes – of which there are around twenty spread throughout the painter’s career, with a particu-lar concentration in the 1630s and 1640s – presents us with a binary structure from which we can extract a list of opposed dichotomies. however, after a more careful examination, these pairs are systematically re-vealed to be much more dialectically treated than the simple idea of ‘opposition’ suggests. Moreover, the series of oppositions, based on the fundamental du-ality between land and sea constitutive of any port scene, can be shown to correspond quite closely to the two basic elements of Greek tragic culture according to Nietzsche, the two deities that for the German philoso-pher incarnated and summed up two entire anthropo-logical systems.

Was Claude historically capable of such a dialec-tic comprehension of culture? According to one of the most perceptive scholars of Baroque discourse, complex binaries were a staple of seventeenth-centu-

8 For a rare – and inspired – treatment of the links between Nietzsche and Claude, see Clélia Nau, Claude Lorrain: “scaenographiae solis”, Paris 2009, pp. 149–153. 9 We must also bear in mind damian dombrowski’s warning of direct-ly applying the nineteenth-century Apollonian/dionysian dichotomy to seventeenth-century culture; dombrowski claims that “in der Antike, aber auch noch in renaissance und Barock konnten Apoll und Bacchus sogar als numen mixtum auftreten, wie im Falle eines zwischen 1626 und 1630 datier-ten Gemäldes von Nicolas Poussin” (damian dombrowski, “die häutung des Malers: stil und Identität in Jusepe de riberas Schindung des Marsyas”, in: Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte, lXXII [2009], pp. 215–246). But this warning concerns the more literal application of the dichotomy to depictions of the Marsyas myth, whereas in Claude’s case the allusion is much more indirect and does not require the painter’s conscious use of the terms “Apollonian” and “dionysian”. 10 Among Nietzsche’s references to Claude, see especially the following: “erst Mozart gab dem Zeitalter ludwig des Vierzehnten und der Kunst racines und Claude lorrains in klingendem Golde heraus” (Menschliches, Allzu-menschliches, Munich 1999 [original ed. 1878], p. 450). “die schwerste und

letzte Aufgabe des Künstlers ist die darstellung des Gleichbleibenden, in sich ruhenden, hohen, einfachen, vom einzelreiz weit Absehenden […]. schon der Wunsch nach einem dichterischen Claude lorrain ist ja gegenwärtig eine unbescheidenheit, so sehr einen das herz darnach verlangen heißt” (ibidem, p. 456). “Ich habe nie einen solchen herbst erlebt, auch nie etwas der Art auf erden für möglich gehalten – ein Claude lorrain ins unendliche ge-dacht, jeder Tag von gleicher unbändiger Vollkommenheit” (Ecce Homo, Mu-nich 1999 [original ed. 1889], p. 356). There are also several references to Claude in Nietzsche’s correspondence: see the letters to Peter Gast, 30 Oc-tober 1888: “hier kommt Tag für Tag mit gleicher unbändiger Vollkommen-heit und sonnenfülle herauf: der herrliche Baumwuchs in glühendem Gelb, himmel und der große Fluß zart blau, die luft von höchster reinheit – ein Claude lorrain, wie ich ihn nie geträumt hatte zu sehn”; to Franz Overbeck, 13 November 1888: “hoffentlich wird der Winter entsprechend wie der herbst gewesen ist: wenigstens hier war er ein wahres Wunder von schönheit und lichtfülle – ein Claude lorrain in Permanenz”; and to Meta von salis, 14 November 1888: “der herbst war hier ein Claude Lorrain in Permanenz” (Friedrich Nietzsche: Werke in drei Bänden, III, ed. by Karl schlechta, Munich 1956, pp. 1327, 1330, 1333).

62 | iTay SaPir |

ry european culture. Gérard Genette’s studies on Ba-roque rhetoric show how in France, for instance, the “univers réversible” comprising water and air or sea and sky – and thus also their respective faunas – was a frequent motif.11 What Genette calls an “ingénieux système d’antithèses, de renversements et d’analo-gies”12 is a symptom of a culture highly conscious of alterity, yet often only capable of understanding the latter as a perverted, or masked, identity. An in-finite play of mirrors where “toute différence est une ressemblance par surprise”,13 and the ‘other’ is but a paradoxical state of the ‘same’. Genette himself speaks explicitly of dialectics – for example, between reality and dreams – as constitutive of seventeenth-century culture.

The hugely popular Baroque figure of Narcissus is emblematic in this context. It revolves around the question of mirroring, of reflection in water, and for Genette it symbolizes the Baroque idea of existence: vertige, but conscious and organized.14 The Baroque world is but its own reflection in water. The relevance of this lesson for Claude’s seaside structures is quite easily detected.

Of Genette’s analyses of seventeenth-century culture, the most directly helpful for our reading of Claude’s seaports as anthropological metaphors is to be found in an article entitled “l’or tombe sous le fer”.15 It begins with Genette’s summary of the con-ventional wisdom on Baroque aesthetics, according to which, at the end of the sixteenth century, classical norms of order were replaced by new values of move-ment, fluidity, animation, expansion, and profusion, all modelled on ‘living’ nature and in particular its aquatic elements. The author then turns his attention to contemporary French poetry and finds it surpris-ingly different from the cliché image of the Baroque,

as this poetry is structured around differences and contrasts: “le monde sensible se polarise selon les lois strictes d’une sorte de géométrie matérielle. les élé-ments s’opposent par couples: l’Air et la Terre, la Terre et l’eau, l’eau et le Feu. le Froid et le Chaud, le Clair et le sombre, le solide et le liquide […].”16

Though Genette speaks of poetry, his descrip-tion seems perfectly adapted to Claude’s painted port scenes. After all, as he says, antithesis can be seen as “la figure majeure de la poétique baroque”,17 and po-etics can also be visual. The purpose of this poetics is, again if we follow Genette, “maîtriser un univers démesurément élargi, décentré, et à la lettre désorien-té en recourant aux mirages d’une symétrie rassurante qui fait de l’inconnu le reflet inversé du connu”.18 The world thus becomes both vertiginous and, to its in-habitants’ relief, manageable.

This is also the main function of Claude’s dialec-tics of land and sea, architecture and texture, culture and nature, the finite and the infinite and, indeed, the Apollonian and the dionysian – a series of opposi-tions around which Claude’s seaports can be said to be structured. In an ever-expanding universe which is constantly diversifying astronomically, geographically and anthropologically, Claude’s seaports exorcise the vertiginous threat not by denying it but by careful-ly depicting ambitious, spectacular human creations alongside the immeasurable, incontrollable sea.

One of Claude’s most impressive port scenes, The port of Ostia with the embarkation of St. Paula, was created in 1639/40 for the Buen retiro Palace in Madrid; it is now at the Prado Museum (Fig. 1). Its composition is very typical of the general arrangement of Claude’s seaports – indeed, one of the fascinating things about this series of variations on a theme is that, while they are connected by a clear repeated arrangement, each

11 Gérard Genette, Figures I, Paris 1966, pp. 9–20. 12 Ibidem, p. 20. 13 Ibidem. 14 Ibidem, pp. 21–28.

15 Ibidem, pp. 29–38. 16 Ibidem, p. 30. 17 Ibidem, p. 35. 18 Ibidem, p. 37 (italics by Genette).

| CLaude LOrraiN’S POrT SCeNeS | 63

the dionysian, not to mention the liquidity of diony-sus’ own favourite substance.

As I’ve already intimated, the two elements are far from being mutually exclusive, both in Nietzsche and in Claude. They are entangled to create the complex entity of human culture, our world as human beings. For Nietzsche, it was only by combining both ele-ments that Greek culture obtained the mature summit of art and understanding before the inevitable decline of the victory of logos; for Claude, interest in the port theme lies precisely in the fact that a harbour is the interface between both elements.

This interface is porous. A port is not just a place where two elements confront each other, rather it is a system involving their interaction and interpenetra-tion, a dialectical process just like the one Nietzsche described in The Birth of Tragedy. land and sea con-stantly interfere in each other’s domain giving rise to a whole series of binary oppositions that can be listed in parallel under their headings, separate only in the-ory: man and environment, artifice and nature, finite and infinite, Apollonian and dionysian. In addition are the more politically loaded categories of ethnicity and gender: if buildings are masculine and associated with the ‘self ’, the sea is feminine and ‘other’. Claude, however, knew better than that and, just like his con-temporary poets, he deconstructed these clichés rather than rehearsing them.

Another useful analysis courtesy of Gérard Ge-nette, in the article “le jour, la nuit”,20 reminds us how such dichotomies are structured: just like the op-position between day and night analyzed by Genette, that between land and sea is only deceptively symmet-rical, and in fact slightly biased. Genette demonstrates how, poetically speaking, the night is dependent and somewhat inferior whereas ‘day’ in some cases seems

painting has its own atmosphere, details and formal nuances. however, this painting has an important par-ticularity due to the circumstances of its commission: it is the only port scene by Claude in vertical format.

This verticality, though rare and apparently forced, emphasizes the fundamental characteristics of the other, horizontal variations: it reinforces the spectacu-lar impression given by the magnificent palaces and, through the rigorous linear perspective of those ar-chitectural creations, leads our eyes to the sea at the centre – where the gaze becomes lost in the blurry distance – with more power than ever. The edifices in Claude’s ports, and here in particular, are quintessen-tially Apollonian: all their elements are clearly individu-alized, the order is perfect and appearance is all. like all products of Apollonian culture, these buildings are civilization’s answer to the discontents that might perturb its peace. They are reassuring, at least at a su-perficial glance: solid, classical and proud, like older versions of modern skyscrapers.

The perfect perspective created by the depiction of these palaces draws our eyes towards the vanishing point, but there the promise of stability drowns in the infinite, chaotic black hole of the sea. The sea – which here, narratively speaking, is indeed the Mediterrane-an, but more on that later – represents the opposite pole to the mighty edifices of the port, being both their raison d’être and their nemesis. Whereas the edi-fices are man-made, finite, geometrically reasonable and thus mathematically representable, the sea is hu-mankind’s wildest frontier, where our aspirations and ambitions are cut short.19 It is easy to see that if the architectural framework is indeed Apollonian, the sea corresponds in many ways to Nietzsche’s other ele-ment: the savagery, unpredictability and amorphous-ness of the liquid wilderness is a natural metaphor for

19 On early Modern perception of the sea, see Alain Corbin, The Lure of the Sea: The Discovery of the Seaside in the Western World 1750–1840, trans. by Jocelyn Phelps, london 1995 (original French edition: Le territoire du vide: l’Occident et le désir du ravage, Paris 1988). The chronological scope of this

book is in fact broader than its title declares. see also La mer: terreur et fasci-nation, exh. cat. Paris/Brest 2004/05, ed. by Alain Corbin/hélène richard, Paris 2004. 20 Gérard Genette, Figures II, Paris 1969, pp. 101–122.

64 | iTay SaPir |

22 The inclusion of the inscription is explained by Andrés Úbeda de los Cobos as necessary due to the story’s rarity (Nature et idéal: le paysage à Rome 1600–1650, exh. cat. Paris/Madrid 2011, Paris 2011, p. 204, no. 71).

to include both the nocturnal and the diurnal parts of the 24-hour cycle. Poetic valorisation of the night is “presque toujours sentie comme une réaction, comme une contre-valorisation”, says Genette, and this is defi-nitely true for our ‘land’ and ‘sea’ pair where, for in-stance, the name of the planet, earth, is also the name of the element that makes up its solid component.

Genette goes on to consider the phonetic charac-teristics of the words ‘jour’ and ‘nuit’; painting – and Claude’s seaports in particular – seems to offer us a visual equivalent for the same structure. If we examine the Prado painting, the two elements at first seem to divide the painted surface quite equally; but the sea, in fact, exists only in the negative, as a vacant, absent and undefined entity.

such a visual depiction of water is consistent with the cultural significance of the liquid element elabo-rated upon by Gaston Bachelard in his famous study L’eau et les rêves.21 Although Bachelard gives clear prior-ity to fresh water, most of his materialistic analysis also applies to the salty sea. The transitory character, indefiniteness and softness that underlie the cultural and mythical significance of water are all perceived first and foremost in contrast to the solid elements that represent our constant point of reference.

however, the sea’s negativity, its existence as a space which human grandeur – or, indeed, human mad-ness – has not yet conquered, is active. The wilderness of the sea almost imperceptibly pervades the positive, supposedly solid space of the port. This is true in a very literal sense, and in Claude’s painting it is particu-larly striking how the water and stone are formed like jigsaw pieces, penetrating each other’s space so that the semicircle of stone on which the play of civilization is staged, so to speak, is surrounded by ominously empty water and the cavities of the harbour all correspond

21 Gaston Bachelard, Water and Dreams: An Essay on the Imagination of Matter, trans. by edith r. Farrell, dallas 1999 (original French ed.: L’eau et les rêves: essai sur l’imagination de la matière, Paris 1942).

to similarly shaped protuberances on the other side. This can also be seen in smaller details: the vegetation taking possession of the cracks in the superbly artifi-cial edifices; water meeting stone in a slight but visible burst of foam; and statues on top of buildings that seem to be on the verge of instantly falling down and once again becoming formless pieces of natural stone lying, perhaps, at the bottom of their liquid mortal enemy.

The two parts that make up the port are thus in-termingled just like the two elements that make up Greek tragic culture according to Nietzsche. It is not insignificant, then, that this port, here and in most of Claude’s representations, is ostensibly situated on the Mediterranean coast. Admittedly, there are excep-tions in the painter’s oeuvre: the Queen of sheba in the famous london painting (Seaport with the embarkation of the Queen of Sheba, 1648, london, National Gallery) is seen embarking in a harbour situated in an alto-gether more exotic location, around the red sea; and the unfortunate ursula, leaving for her martyrdom in another National Gallery canvas (Seaport with the embar-kation of St. Ursula, 1641), is supposedly set in Cologne. Nevertheless, quite naturally for a seventeenth-centu-ry artist residing in rome, seaports are essentially a Mediterranean affair. In the Prado painting, in a rare gesture, Claude includes an explicit geographical indi-cation in the composition itself: a slab of stone in the foreground bears an inscription that removes all doubt as to the narrative content represented here.22

In art historical literature there is an ongoing debate on the importance of narrative elements in Claude’s – and indeed, much more often, Poussin’s – “landscapes with X and y (often as tiny figures) doing Z”, which are viewed as a mere excuse, a compositional filling or, on the contrary, the nexus and centre of the

| CLaude LOrraiN’S POrT SCeNeS | 65

23 In this context it is interesting to note that the catalogue of the recent exhibition of roman seventeenth-century landscape painting (held at the louvre and the Museo del Prado) emphasizes the relative importance of the narrative episode in The port of Ostia with the embarkation of St. Paula as compared with its more modest role in later ports painted by Claude in the 1640s (Nature et idéal [note 22], p. 204).

who left the empire’s capital with her mother – begged her to remain in rome with them. We witness – in the text more than in the image – her maternal instincts fighting against her religious fervour and losing the battle, and how, when sailing away from Ostia, she couldn’t look back as she knew, unlike the other pas-sengers, that seeing all she had left behind would cause her terrible suffering. Paula left rome and everything the city represented, for her and more generally for contemporary culture, in favour of a wholly different space and way of life where, we are told, it was as if she were “altered by the waters of faith that she had so much desired”.26 The liquid element on which Paula’s trajectory towards salvation literally took place here becomes a powerful metaphor for her conversion.

Paula’s story is thus, in a nutshell, another Bildungs-roman, or coming-of-age narrative, of european cul-ture; it represents the new direction taken by the West following the era of pagan classicism. In this sense, the story depicted by Claude is a mirror image of the story told by Nietzsche. Paula is a perfect product of roman culture: rich, socially highly respectable, and of course a loyal wife and mother. yet, just like rome itself, she ultimately chooses a different direction. Geo-graphically, the centre of gravity of the Mediterranean space now shifts, at least as far as the spiritual dimen-sion is concerned: after Greece and then rome, it is now to Palestine that the search for the soul of the Mediterranean leads. Paula herself is transformed by this spatial journey into a completely different person. she substitutes frugality for luxury, simplicity and even ugliness for exterior beauty and appearance, and ascetic suffering for laughter and delight. Jerome even recounts that Paula, in moving to Palestine, learned

inanimate views that surround them.23 The truth of the matter, as is often the case, is most likely some-where in the middle. As we will see, Claude’s paintings may appear to be first and foremost descriptive, ac-cording to the meaning svetlana Alpers gave this ad-jective with regard to seventeenth-century painting;24 but the inclusion of narrative episodes – a relatively late development, as Claude’s early ports included only genre scenes – is not without significance. In The port of Ostia with the embarkation of St. Paula, in particular, the story cannot be ignored as the narrated episode sup-plies us at the very least with a defined point in space and time, although the latter is rendered absurd by the inclusion of renaissance and medieval architecture in this supposedly late antique scene.

Geographically speaking, this narrative encompass-es most of the Mediterranean space and encapsulates an exemplary Mediterranean life. st. Paula was an aris-tocratic roman lady of the fourth century Ad who became a disciple of st. Jerome and thus decided, after her husband died, to go on a pilgrimage to the holy land where she stayed for the rest of her life. her bi-ography is included in the Golden Legend of Jacobus de Voragine, but the latter in fact simply quotes a text by Paula’s patron Jerome recounting her life.25 The epi-sode depicted by Claude is perhaps the key moment of the saint’s life: her point of transition from a typ-ical existence in late imperial roman society, centred on the family, to a life wholly dedicated to Christian-ity and to her newfound spiritual community. Indeed, this episode is described at length in Jerome’s text as a terrible moment involving a heartbreaking choice. We are told how Paula’s children – apart from her daugh-ter eustochium who was also a disciple of Jerome and

24 svetlana Alpers, The Art of Describing: Dutch Art in the Seventeenth Century, Chicago 1984. 25 An excellent modern (French) edition of the Golden Legend appeared in the ‘Bibliothèque de la Pléiade’: Jacques de Voragine, La légende dorée, Paris 2004. For Paula’s story, see pp. 164–170. 26 Ibidem, p. 166 (translation by the author).

66 | iTay SaPir |

____

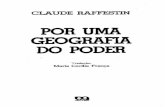

2 Joseph Mallord William Turner,The decline of the Carthaginian empire ‒ rome being determined on the Overthrow of her Hated rival, demanded from her such Terms as might either force her into War, or ruin her by Compliance: The enervated Carthaginians, in their anxiety for Peace, consented to give up even their arms and their Children, 1817. London, Tate Britain

| CLaude LOrraiN’S POrT SCeNeS | 67

___

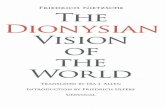

3 Joseph Mallord William Turner, regulus, 1828, reworked 1837. London, Tate Britain

68 | iTay SaPir |

history. The nineteenth-century english painter Joseph Mallord William Turner famously admired Claude and created some paintings that are free versions of the latter’s compositions, notably, indeed, of some of his seaport scenes. significantly, two of the most important pictures that Turner painted after Claude – one of them is permanently exhibited at the london National Gallery in front of its Claudean source of inspiration, following Turner’s explicit request – are entitled, respectively, Dido Building Carthage: or the Rise of the Carthaginian Empire (the one in the National Gal-lery), and The Decline of the Carthaginian Empire – Rome being determined on the Overthrow of her Hated Rival, demanded from her such Terms as might either force her into War, or ruin her by Compliance: The Enervated Carthaginians, in their Anxiety for Peace, consented to give up even their Arms and their Chil-dren (Fig. 2). Thus Turner already considered Claude’s seaports as visual essays on the vicissitudes of histo-ry, on the rise and decline of Mediterranean civiliza-tions. More specifically, the theme of Mediterranean seaports that Turner found so admirably invented by Claude is re-elaborated by the later painter as a ge-ographically defined incarnation of the quintessence and the historical patterns of the mare nostrum. Turner’s later Regulus (Fig. 3) takes to an extreme Claude’s ar-rangement in which solid, concrete, ambitious archi-tecture is rendered somewhat pathetic when its rigid perspective leads the eye to a blinding, glaring vapour impossible to make sense of.

unlike his critical champion John ruskin, who scorned both Claude lorrain’s art and Turner’s re-working of it in the Carthage paintings,27 Turner un-derstood that for Claude, in spite of his reputation as a creator of nothing more than serene, old-fashioned beauty, seaports were not just decorative places or play-ing fields of light and colour. depicted by Claude, in

hebrew easily and perfectly and could speak it – and sing psalms – “without a trace of latin pronuncia-tion”. In passing, we also learn that this roman lady spoke Greek too. In learning hebrew, her geographi-cal and spiritual conversion is thus complemented by a cultural and linguistic metamorphosis.

By including the figure of st. Paula in his port de-piction – or, if we wish to make the narrative the cen-tre of the painting, by choosing a port as the décor for Paula’s story – Claude lorrain gives a double pictorial account of the Mediterranean. On the one hand, he depicts the dialectics of the Mediterranean world be-tween solid coastal cultures and the liquid space that both separates and connects them; on the other hand, he tells the story of a passage through time, from one coastal culture to another, through that very same liquid space. Inevitably he chooses one pregnant moment of the story, namely the episode in which the irreversible transition is on the verge of taking place.

here, if we attempt to apply svetlana Alpers’ aforementioned distinction between description and narration in seventeenth-century painting, it becomes apparent that the reading of Claude’s work as a visual essay on Mediterranean culture depends precisely on the impossibility of distinguishing between the two aspects of this composition: the synchronic, static description and the diachronic, dynamic narrative. Claude’s story of the Mediterranean is encapsulated both in the interpenetrating structure of a port and in the metaphor of a maritime journey across the sea and passage through time.

If it still seems far-fetched to interpret Claude as a pictorial theoretician of Mediterranean culture and its inherent dualities, I wish, in conclusion, to recruit a precious ally, perhaps the greatest admirer and the most perceptive interpreter of Claude in subsequent

27 “Claude had, if it had been cultivated, a fine feeling for beauty of form, and is seldom ungraceful in his foliage; but his picture, when examined with reference to essential truth, is one mass of error from beginning to

end” (John ruskin, Modern painters, I, Part II, sec. I, Ch. VII, quoted from idem, The Lamp of Beauty: Writings on Art, ed. by John evans, london 1959, p. 7).

| CLaude LOrraiN’S POrT SCeNeS | 69

fact, ports in the Mediterranean space are the fulcrum of history, a place where different, antagonistic forces compete and fight for the soul of Mediterranean cul-ture; where Apollo and dionysus, the orderly and the chaotic, the civilized and the wild, the measurable and the eternally elusive, all interact, collide and sometimes intermingle to create the fragile, plural, ambiguous en-tity that is the civilization of the Mediterranean sea.

Abstract

Claude lorrain’s depictions of imaginary seaports can be interpreted as reflecting and narrating the dialectical tension that, according to Nietzsche, had given birth to one of the highest achievements of Mediterranean culture, Greek tragedy: the opposition between the Apollonian and the dionysian. dialectical structures, though rarely associated with Claude, are a staple of Baroque poetics and thus highly relevant to artworks created in rome in the second quarter of the seventeenth century. The binary structure of land and sea, colliding and interpenetrating in Claude’s paintings, is here considered to be a sophisticated pictorial commentary on the vicissitudes of Mediterranean history, supplemented by the diachronic dimension of the narrative content that the mature examples of the seaport series incorporate. Indeed, this is the aspect that J. M. W. Turner, two centuries after Claude, brought to the fore in his own versions of his admired predecessor’s harbour scenes.

Photo credits

© Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado: Fig. 1. – © Tate, London 2014: Figs. 2, 3.