Temporal variations of river basin waters from Topex/Poseidon satellite altimetry. Application to...

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

2 -

download

0

Transcript of Temporal variations of river basin waters from Topex/Poseidon satellite altimetry. Application to...

C. R. Acad. Sci. Paris, Sciences de la Terre et des planètes / Earth and Planetary Sciences 333 (2001) 633–643 2001 Académie des sciences / Éditions scientifiques et médicales Elsevier SAS. Tous droits réservésS1251-8050(01)01688-3/FLA

Géosciences de surface / Surface Geosciences(Hydrologie–Hydrogéologie / Hydrology–Hydrogeology)

Temporal variations of river basin waters fromTopex/Poseidon satellite altimetry. Application tothe Amazon basinIlce de Oliveira Camposa,b, Franck Merciera, Caroline Maheua, Gérard Cochonneauc, Pascal Kosuthc,Denizar Blitzkowb, Anny Cazenavea,∗a Legos–GRGS/Cnes, Observatoire Midi-Pyrénées, 18, av. Édouard-Belin, 31400 Toulouse, Franceb EP–University of São Paulo, Brazilc LMTG IRD, Lago Sul Brasilia, Brazil

Received 23 July 2001; accepted 18 September 2001

Communicated by Gérard Mégie

Abstract – Although developed and optimised for open oceans, satellite altimetry has thepotential to monitor level variations of inland surface waters such as lakes and rivers. Herewe present results of water level variations of the Amazon River based on eight years (1993–2000) of altimetry data of the Topex/Poseidon satellite. We first discuss methods to detectwet surfaces from the altimetric measurements, discriminate between water and dry land,and quantify the accuracy of altimetric measurements over water. Then we show waterlevel fluctuations at selected locations where the satellite crosses the Amazon River. Thedominant signal is seasonal, mostly annual, with an amplitude of up to 10–15 m peak topeak. Comparison with in situ measurements indicates that water levels are well measuredby Topex/Poseidon during high-water season, unlike low-water season, which suffers fromdata gaps. We further discuss the interannual component of the signal, which shows twomarked minima in 1995 and 1998. The 1998 minimum is interpreted as an effect of the1997–1998 ENSO event, causing rainfall deficit in the central part of the Amazon basin,hence decrease in water levels. An EOF analysis of precipitation fields over the basin duringthe 1993–1999 period confirms the rainfall minimum by the end of 1997 for this region. 2001 Académie des sciences / Éditions scientifiques et médicales Elsevier SAS

satellite altimetry / Amazon basin / regional hydrology

Résumé – Suivi des variations temporelles des niveaux d’eau des fleuves à partir de mesuresaltimétriques de Topex/Poseidon. Application au bassin de l’Amazone.Bien que développée etoptimisée pour le plein océan, l’altimétrie spatiale s’avère être un outil très utile pour étudier lesfluctuations temporelles des niveaux d’eau sur les continents, en particulier les niveaux des lacs etdes grands fleuves. Dans cette note, nous présentons des séries temporelles de niveaux d’eau surl’Amazone issues de mesures altimétriques de Topex/Poseidon entre 1993 et 2000. Nous discutonsen premier lieu les méthodes permettant de distinguer, dans le signal altimétrique, l’eau des solssecs et de la végétation, ainsi que de quantifier la précision de la mesure altimétrique. Les niveauxde l’Amazone mesurés par Topex/Poseidon sur différents sites présentent une signature saisonnière(principalement annuelle) dominante, avec une amplitude pouvant atteindre 10–15 m pic à pic.Des comparaisons avec des mesures in situ indiquent que Topex/Poseidon restitue correctementles niveaux en période de hautes eaux, ce qui n’est pas toujours le cas en période de basses eaux,quand les mesures valides sont peu nombreuses. Ceci empêche de décrire avec précision le cycle

∗ Correspondence and reprints.E-mail addresses: [email protected] (C. Maheu), [email protected] (A. Cazenave).

633

I. de Oliveira Campos et al. / C. R. Acad. Sci. Paris, Sciences de la Terre et des planètes / Earth and Planetary Sciences 333 (2001) 633–643

saisonnier en certaines zones du fleuve. La composante interannuelle du niveau d’eau présente deuxminima marqués, en 1995 et 1998. Celui de 1998 constitue un effet de l’événement ENSO de 1997–1998, dont une des conséquences est un déficit de précipitations au Centre du Bassin amazonien.Une analyse en EOF des champs de pluie sur la période 1993–1999 confirme cette observation. 2001 Académie des sciences / Éditions scientifiques et médicales Elsevier SAS

altimétrie spatiale / Amazone / hydrologie régionale

Version abrégée

1. Introduction

Le suivi des variations temporelles des niveaux d’eaudes fleuves est classiquement réalisé par des enregistre-ments in situ. Ces variations de niveau peuvent ensuiteêtre exprimées en débits, paramètres intéressants pour l’hy-drologue, à l’aide de courbes d’étalonnage. Cependant, laplupart des grands bassins fluviaux couvrent des régionsd’accès difficile, ce qui limite considérablement l’installa-tion de réseaux opérationnels de stations hydrographiquesin situ. L’altimétrie spatiale offre une alternative intéres-sante à la mesure régulière des niveaux d’eau des réser-voirs continentaux. Plusieurs études ont montré que cettetechnique possède le potentiel pour mesurer les fluctua-tions spatio-temporelles des niveaux d’eau sur les mers in-térieures, les lacs, les fleuves et mêmes les zones d’inonda-tion permanentes et temporaires [2–4, 6, 13, 15–18]. Danscette note, nous présentons des séries temporelles de niveaud’eau de l’Amazone, basées sur les mesures altimétriquesdu satellite Topex/Poseidon entre janvier 1993 et décembre2000.

2. Le bassin amazonien

Le Bassin amazonien est le plus grand bassin hydrogra-phique du monde, tant en terme de superficie (∼ 6 000 000km2) que de débit annuel moyen (∼ 200 000 m3·s−1). Lavariabilité du niveau de l’Amazone, de ses affluents et deszones d’inondation est dominée par un cycle saisonnier,conséquence de l’oscillation saisonnière des précipitationssur le bassin. À l’échelle de temps inter-annuelle, la varia-bilité dominante est associée aux événements ENSO, quiprovoquent un déficit de pluie sur la partie centrale du bas-sin [1, 7–9, 12, 14, 21].

3. Analyse des mesures altimétriques deTopex/Poseidon

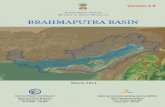

Nous avons analysé huit années complètes (de janvier1993 à décembre 2000) de mesures altimétriques deTopex/Poseidon [1]. Lafigure 1 montre la couverturedes traces de Topex/Poseidon sur le Bassin amazonien.Les mesures altimétriques sont d’abord corrigées desdifférentes erreurs dues à la propagation dans l’ionosphèreet la troposphère sèche ainsi que des effets de maréessolides. Certaines corrections, nécessaires pour le pleinocéan, ne sont pas appliquées ici. La correction appelée« troposphérique humide » due à la présence de vapeur

d’eau dans la basse atmosphère n’est malheureusementpas disponible sur les surfaces continentales et n’est doncpas appliquée. Celle-ci peut atteindre 20–30 cm dans lesrégions tropicales et varie de façon saisonnière (amplitudede l’ordre de 10 cm). Ceci constitue une source d’erreurnotable dans notre analyse.

Pour estimer la répétabilité des hauteurs d’eau mesu-rées, nous avons comparé les séries temporelles de niveauau voisinage d’un point de croisement issues d’une tracemontante et d’une trace descendante. Pour être fiable, cettecomparaison devrait se faire en un point de croisementsitué sur l’eau. Or, une telle situation n’existe pas. Nousavons donc comparé les niveaux d’eau en deux points dis-tants de 15 km (indiqués par des cercles sur lafigure 2a).Les séries temporelles correspondantes sont présentées surla figure 2b, ainsi que les différences. L’écart type des dif-férences est de 82 cm (55 cm lorsque celles-ci sont moyen-nées sur 150 jours), valeur qui inclut l’incertitude sur lamesure ainsi que la différence des signaux saisonniers entreles deux points. Pour estimer l’exactitude, nous avons com-paré les séries temporelles continues de niveau d’eau dé-duites des mesures Topex/Poseidon avec des mesures insitu issues de stations hydrographiques. Deux exemplessont présentés sur lesfigures 3a (trace 63) et3b (trace139). Sur lafigure 3a, on note un bon accord entre les deuxcourbes. L’écart type des différences est de 45 cm. Lafi-gure 3b montre un exemple où Topex/Poseidon ne fournitpas de mesures valides en basses eaux, pour des raisons di-verses (réflexions parasites dues aux berges, par exemple).Dans ce cas, le signal saisonnier est mal décrit, en raisonde l’absence de mesures en basses eaux.

La figure 4 présente les séries temporelles de hauteurd’eau de l’Amazone en deux sites (trace 102 et trace 63).Chaque série est construite en moyennant les mesures del’intersection d’une trace Topex/Poseidon avec le fleuve.On note un signal saisonnier dominant, atteignant 10–15 mpic à pic dans la partie centrale du bassin.

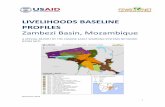

Nous avons étudié la variation inter-annuelle des ni-veaux en utilisant la hauteur maximale annuelle, correcte-ment mesurée par Topex/Poseidon, pour neuf traces répar-ties le long de l’axe principal de l’Amazone (figure 5). Surles courbes de lafigure 5, on note deux minima marquésen 1995 et 1998. Le minimum de 1998, uniquement vi-sible sur la partie centrale du bassin, est la conséquence dudéficit de précipitation typique des événements ENSO [5,7, 10, 21]. Une décomposition des champs de précipita-tion [24] en EOF (Empirical Orthogonal Functions) [19,22] a été effectuée pour la période 1993–1999. Sur la cartede la structure spatiale du mode 1 (figure 6), on note une ré-

634

I. de Oliveira Campos et al. / C. R. Acad. Sci. Paris, Sciences de la Terre et des planètes / Earth and Planetary Sciences 333 (2001) 633–643

gion à très fort déficit pluviométrique en 1997–1998 (partiecentrale du bassin), en accord avec les analyses des don-nées de pluie lors des événements ENSO antérieurs [5, 7,9, 10, 14, 21].

4. Conclusion

Cette étude montre la capacité de l’altimétrie radar àfournir une information pertinente sur les niveaux d’eaudans les grands bassins hydrographiques. Les principaleslimitations de la technique apparaissent liées à l’espace-ment minimal des mesures le long de la trace (de l’ordre de0,5 km) et à de fréquentes lacunes en matière de mesures

en basses eaux. Des améliorations sensibles devraient êtreobtenues après correction de la perturbation liée à la tro-posphère humide, ainsi que par l’exploitation des donnéesaltimétriques des satellites ERS-1 et ERS-2, qui offrent unecouverture spatiale plus dense que Topex/Poseidon. Les ap-plications incluront l’identification des zones inondées enbasses eaux et en hautes eaux, l’estimation des variationssaisonnières du volume d’eau stocké en surface du bassin,l’estimation des débits lorsque les courbes hauteur–débitsont connues, l’établissement de référentiels altimétriqueshomogènes sur les bassins. Au-delà du bassin de l’Ama-zone, ces applications constituent un enjeu important pourtous les grands bassins fluviaux de la planète.

1. Introduction

Water balance of large river basins relates changesin water stored in soils, aquifers, rivers, floodplainsand wetlands with fluxes like precipitation, evapora-tion and river runoff. It is thus a measure of regionalclimate variation, even if anthropogenic factors, suchas change in land use, deforestation, irrigation, dambuilding, etc., may also contribute to the budget. Riverrunoff (and surface water levels) represents an im-portant component of the total water budget over thebasin. Being less spatially heterogeneous than precip-itation, the runoff signal integrates changes in hydro-logic characteristics over a large area and is a partic-ularly valuable indicator of regional climate changeover a drainage basin both at seasonal and interannualtime scales [17].

Monitoring of river water level is traditionallybased on in situ river gauging stations. These levelmeasurements are further expressed in terms of dis-charge rates that are the hydrologic parameters of in-terest. However, most of the large river basins arelocated in remote areas where recording stations arevery scarce or even inexistent, a result of either inac-cessibility or economical/political restrictions in de-veloping countries. Satellite-based sensors, in par-ticular satellite altimetry, offer a promising alterna-tive for monitoring surface water levels in remote ar-eas. Although satellite altimetry has been developedand optimised for open oceans, several studies havedemonstrated its capability of measuring water levelchange of continental surface reservoirs such as in-land seas and lakes [2, 3, 6, 13, 15, 16, 18]. The ques-tion of using satellite altimetry for monitoring waterlevel of rivers, floodplains and wetlands has been alsoaddressed [4, 11]. Birkett [4] showed that, in spiteof technical limitations, level change of the world’slargest rivers could be monitored by satellite altimetrywith a few decimetres precision, from intraseasonal tointerannual time scales.

In this paper, we present results of surface waterlevel fluctuations in the Amazon basin based onaltimetry data of the Topex/Poseidon satellite over an8-year time span. One of the limitations in using radaraltimetry to monitor river levels is the ground trackresolution (for Topex/Poseidon, the minimal along-track ground spacing is∼ 580 m between each radarecho), preventing narrow rivers to be observed. Inaddition, vegetation canopy of surrounding terrainsand presence of rough topography produce parasitereflections that deteriorate radar echoes, so that unlikein the oceanic domain, the first task here is to identifywater reflection in the signal. In this paper, we firstdiscuss the methodology developed for detection ofwater surfaces. Then we present results of water leveltime series constructed at selected locations alongthe Amazon River. Finally, we discuss the observedseasonal and interannual signal, and the relation of thelatter with the 1997–1998 ENSO event.

2. Amazon basin

The Amazon basin is the largest hydrographic basinin the world, both in terms of area (∼ 6 million km2)and mean annual discharge (∼ 200000 m3·s−1) thatis equivalent to about 20 % of the world’s rivers in-put to the oceans. The variability of water level ofthe Amazon River, tributaries and floodplains is dom-inated by the annual cycle. This seasonal variability ismainly driven by the annual variation in rainfall, itselflinked to the variation of atmospheric circulation overSouth America [20]. Precipitation patterns over theAmazon basin exhibit strong variations from year toyear [8, 12]. River flow is mainly the result of rainfalland evaporation with rainfall being the dominant com-ponent (e.g., [7]), although relations between runoffand precipitation is complicated by ‘basin memory ef-fects’ in large catchment basins such as the Amazonbasin (e.g., [21]). Thus, rainfall variability over theAmazon basin causes changes in surface water levels

635

I. de Oliveira Campos et al. / C. R. Acad. Sci. Paris, Sciences de la Terre et des planètes / Earth and Planetary Sciences 333 (2001) 633–643

and river discharges. Water vapour flux over the Ama-zon basin originates predominantly from the equator-ial Atlantic Ocean. However, several studies have re-ported that the predominant interannual variability inthe hydrographic parameters (e.g., water level, dis-charge) in the Amazon basin (mainly northern Ama-zon Basin) is related to ENSO events [7–9, 12, 14,21]. Indeed, in most parts of the basin, ENSO yearsgive rise to rainfall deficit and reduced discharges.The only exception is the Madeira basin, located inthe southwest of the Amazon Basin, which shows anopposite behaviour, i.e., rainfall excess, during ENSOyears [14]. The relation between ENSO and the Ama-zon basin hydrology should result from modificationsin atmospheric circulations and in sea surface temper-ature distributions in the tropical Pacific [8] that mod-ify the precipitation pattern over the Amazon basin,hence discharge rate of the Amazon river. It is worthmentioning that scarcity of data concerning groundwater dynamics over the Amazon basin prevents anyestimate of their contribution to river runoff variationthrough time. Ground waters could indeed partiallycompensate or damp interannual variability of precip-itations.

3. Altimetry data analysis

3.1. Topex/Poseidon data

Radar altimetry from space consists of verticalrange measurements between the satellite and wa-ter level. Difference between the satellite altitudeabove a reference surface (usually a conventional el-lipsoid), determined through precise orbit computa-tion, and satellite-water surface distance, providesmeasurements of water level above the reference sur-face. Placed onto a repeat orbit, the altimeter satel-lite overflies a given region at regular time intervals(called the orbital cycle), during which a completecoverage of the Earth is performed. Here we use al-timetry data from the Topex/Poseidon (T/P) satellite(launched in August 1992) to investigate the capabil-ity of the altimetric technique to monitor water lev-els in large hydrographic basins. The temporal reso-lution of the T/P data is 10 days (the duration of anorbital cycle). Its ground track coverage is 315 kmin equatorial regions. Although not as dense as forthe ERS-1/2 coverage (about 4 times denser), theexisting T/P database has the advantage of provid-ing directly altimetric height measurements over land,unlike the ERS-1/2 missions for which only wave-forms are available. We have analysed eight yearsof Topex/Poseidon altimetry data from January 1993to December 2000, using the most upgraded GDRs(Geophysical Data Records) made available by theTopex/Poseidon AVISO/Altimetry Data Centre [1].

The GDRs contain range values derived from aver-aged radar echoes at 100 ms and 1 s interval, whichcorresponds to along-track ground spacing of 580 mand 5.8 km, respectively. We used both data sets. Inaddition to the altimetric heights and radial orbit com-ponent, the data set includes a series of environmentaland geophysical corrections. Over open ocean thesecorrections include: ionospheric correction, dry andwet tropospheric correction, solid Earth, ocean andpole tides, ocean tide loading, inverted barometer ef-fect and sea state bias. Models for these correctionshave been improved continuously along the T/P life-time to increase the precision of sea surface heightsfor open ocean studies, which is currently at the 1-cmlevel for a single measurement.

However, for continental water studies, correctionmodels optimised for open oceans are not necessarilyadequate. More problematic is the fact that over con-tinents, some corrections such as the wet troposphericcorrection may be simply missing. This problem,along with ground resolution, is the most serious lim-itation when using the altimetry data for continentalwater level monitoring.

In the present study, we applied the ionospheric,dry tropospheric and solid Earth tide corrections. Poletide, ocean tide, ocean tide loading, inverted barom-eter and sea state bias are ocean effects, thus are ne-glected here. We also corrected the T/P measurementsfor instrumental drifts and bias as recommended bythe T/P project. The ionospheric correction is basedon the onboard DORIS measurement of the electroniccontent. The dry tropospheric correction is accu-rately computed from ECMWF (European Centre forMedium Range Weather Forecast) surface pressurefields. The wet tropospheric correction derived fromthe onboard Topex Microwave Radiometer (TMR)over oceans, is generally missing over land. The TMRinstrument has a large footprint (43.4 km in diameterfor the 18 GHz channel). When the satellite overfliesrivers, the TMR footprint always encompasses sur-rounding lands, making the atmospheric water vapourmeasurement unusable. Over land, the troposphericcorrection is in principle available from outputs ofglobal circulation models such as the ECMWF opera-tional analysis. Unfortunately, in the AVISO database,this data is missing over most of the land surfaces, inparticular over the Amazon basin. We looked at thePODAAC database (the U.S. equivalent of AVISO forthe T/P project) that provides the ECMWF-based tro-pospheric correction as a backup to the TMR correc-tion. However, we noted that along the T/P tracks, thiscorrection is set to a constant value over several thou-sands kilometres, with in some cases abrupt discon-tinuities between the constants. The reason for suchbehaviour is unclear. Considering the suspicious tro-pospheric correction given by the PODAAC database

636

I. de Oliveira Campos et al. / C. R. Acad. Sci. Paris, Sciences de la Terre et des planètes / Earth and Planetary Sciences 333 (2001) 633–643

over the Amazon basin, we decided not to apply it.Not correcting for the wet tropospheric effect intro-duces a systematic bias up to 20–30 cm in tropical re-gions, plus a seasonal error of about 10 cm amplitude.The systematic bias is not problematic here, becausewe are studying relative water level time series. Thisis unlike the seasonal error, which represents a seriouslimitation to the results so far obtained.

3.2. Methodology for detecting and measuringopen water bodies in the Amazon basin

Radar echoes over land surfaces are hamperedby interfering reflections due to water, vegetationcanopy and rough topography. As a consequence,waveforms (e.g., the power distribution of the radarecho within the range window) may not have thesimple broad-peaked shape seen over ocean surfaces,but can be complex, multi-peaked, preventing fromprecise determination of the altimetric height. Inthe case of the Amazon basin, which is extremelyflat, problems may arise from interference betweenthe vegetation canopy and water from wetlands,floodplains, tributaries and main river. Outside wetareas, most radar echoes are rejected automatically.Thus to discriminate between water surface and dryland, we considered a series of tests.– Test 1 (‘measurement density’ test): along a givensatellite track, we considered the whole set of 10-dayrepeat passes over the eight years; at the mean posi-tion of each along track 1 s measurement, we countedthe total number of valid data; for that purpose, weconsidered all available measurements (at 10-day in-tervals over the eight years) inside successive circlesof 3-km radius; points (i.e., circles) with less than50 % valid measurements were rejected.– Test 2 (‘water level fluctuation’ test): over someselected tracks, we constructed surface level timeseries over the 8-year time span. Points with clearseasonal signal (annual amplitude at least of 1 m)allow mapping open water bodies as intersected byT/P tracks, while dry/vegetated surfaces do not exhibitany detectable seasonal height variation.– Test 3 (‘backscatter coefficient’ test): at each lo-cation along the track, we constructed time series ofthe radar backscatter coefficient (denoted byσ0); wetsurfaces have typically radar backscatter coefficientshigher than 20 dB [4] and we used this threshold toselect wet areas.

Test 1 (‘measurement density’ test) enlightened ageneral trend of lower response density over riversthan over surrounding wetlands. The reason for thisphenomenon is still under investigation and couldbe linked to saturation of the onboard altimeterinstrument by high intensity echo. Until now this

test does not allow a reliable mapping of open waterbodies in the Amazon basin.

Tests 2 and 3 give more reliable results in termsof detection of open water surfaces. Infigure 1, thewet areas detected by T/P using the ‘backscattercoefficient’ test are depicted by yellow/red colours.These wet areas include not only main river andtributaries, but also flooded areas in high water seasonand permanent wetlands. It is worth mentioning thatin some cases, valid data at main river-T/P trackintersections are lacking (seefigure 1). It would benecessary to examine the raw radar data (waveforms)to understand why altimetric measurements have beendeleted over the river. A possible explanation is thespecular nature of the reflection over the river, leadingto a Dirac-type returned waveform that on onboardtracking algorithm is unable to identify as a validmeasurement. This will be the object of a futureinvestigation.

4. Water level time series along theAmazon River

4.1. Validation of the T/P-derived water levelseries; comparison with in situ level gauging data

Validation of the T/P time series was performedby: (1) comparison of water level time series nearbya crossover point between ascending and descendingprofiles, and (2) comparison with ground-based waterlevel data from gauge stations.

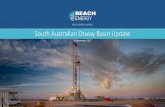

Crossover comparison between ascending and de-scending profiles is a classical method to estimate in-ternal precision of altimetric heights over ocean sur-faces. However, it must be underlined that such mea-surements by ascending and descending profiles oc-cur with a 1- to 5-day lag time and river water levelhas evolved between theses two measurements. Ap-plying the method to T/P data in the Amazon basinrequires the crossover to be located over a wet sur-face. A single crossover meets (approximately) thiscondition.Figure 2a shows the position of the crossover nearby the Japurá River. It is not exactly locatedover the river, but about 10 km north on land. Wethus decided to compare the water level time seriesat locations where the two T/P tracks cross the river(distant by about 15 km). Infigure 2b are shown thetwo T/P water level measurement time series. Theysuperimpose quite well. However the rms differencecalculated for all 134 common measurement dates is82 cm. This rms difference can be interpreted as theT/P instantaneous measurement mean error on thissection of the Japurá River, whose high value is prob-ably due to the narrowness of the river (500 m). Forlonger time spans, the mean error will be lower. If

637

I. de Oliveira Campos et al. / C. R. Acad. Sci. Paris, Sciences de la Terre et des planètes / Earth and Planetary Sciences 333 (2001) 633–643

Figure 1. Topographic map of the Amazon basin on which are superimposed the Topex/Poseidon satellite tracks (identified by their number). Thecolor variation along the tracks represents the backscatter coefficient (σ0) intensity (in dB). Water detection is supposed to correspond to colorother than blue. The highest values ofσ0 (red color) coincide in general with the main river and tributaries. When away from rivers, highσ0 valuesallow detection of flooded plains and wetlands. Yellow boxes correspond to areas selected in the present analysis. Black dots show the position ofthe in situ water gauges: stations of Tabatinga (box 1), Itapeua (box 3), Manacapuru and Manaus (west and east respectively; box 4) and Parintins(box 5).

Figure 1.Carte du bassin amazonien et traces de Topex/Poseidon. Les couleurs le long des traces indiquent l’intensité du paramètre de rétrodiffusiondu signal radar. Les cercles noirs indiquent la position des stations in situ : stations de Tabatinga (région 1), Itapeua (région 3), Manacapuru etManaus (d’ouest en est ; région 4) et Parintins (région 5).

smoothed through a 150-day running average, the dif-ference time series has indeed a lower rms, of 55 cm.

In situ measurement comparison used data from thepermanent network of more than 200 gauging stationsimplemented by ANEEL (Agência Nacional de Ener-gia Elétrica, Brazil) along the main river and tribu-taries of the Amazon basin since the early 1970s. Fullcircles infigure 1 indicate positions of the gauging sta-tions used in this study. The gauging level measure-ments are referred to some arbitrary reference whilethe T/P level measurements are relative to the ellip-soid. Two methods were developed to compare rawT/P measurements (every 10 days) with gauging sta-tions measurements (every day). First method consistsof removing to each time series its 8-year average andthen comparing resulting ‘zero mean’ T/P and in situ

time series. This method presents two drawbacks: theT/P measurement density is higher during high flowperiod than during low flow period, which leads toan overestimation in the mean T/P water level; thegauging station can be far from the T/P track inter-section, resulting in a difference in signal amplitude(annual water level fluctuations). A second methodwas developed to minimize these drawbacks: it recon-structs an ‘in situ’ continuous time series of water lev-els on the T/P track using a linear regression betweenT/P measurements and the selected gauging station.This allows us comparing raw T/P series and recon-structed in-situ series. For both methods the rms er-ror between T/P measurements and the in situ series(observed or reconstructed) quantifies the dispersionof T/P measurements and can be interpreted as the

638

I. de Oliveira Campos et al. / C. R. Acad. Sci. Paris, Sciences de la Terre et des planètes / Earth and Planetary Sciences 333 (2001) 633–643

(a) (b)

Figure 2. a. Map showing the position of a crossover between ascending and descending T/P track.b. Comparison of the two T/P-based waterlevel time series at the positions identified by the white circles. The residual time series is also shown.

Figure 2. a.Point d’intersection d’une trace montante et descendante au voisinage du fleuve Japura.b. Séries temporelles de niveau d’eau, mesuréespar T/P aux points indiqués par les cercles blancs sur lafigure 2a. La courbe des différences est aussi présentée.

(a) (b)

Figure 3. Comparison of the T/P-derived water level time series (dots) and reconstructed time series from the in situ gauging information (solidcurve).a. Track 63, box 4 (the difference time series is also shown).b. Track 139, box 5.

Figure 3. Séries temporelles de niveau d’eau de l’Amazone, mesurées par T/P (points) et reconstruites à partir de mesures in situ (courbe en traitplein).a. Trace 63 (la courbe des différences est aussi présentée).b. Trace 139.

accuracy of T/P measurements. We have comparedthe T/P-derived and the reconstructed (i.e., based onmethod 2) continuous time series, at two locations:track 63 (box 4,figure 3a) and track 139 (box 5,fig-ure 3b). Figure 3a presents the water level time seriesat the intersection between the Amazon River and theT/P track numbered 63, re-built from the gauging sta-tion information located 8.5 km upstream in Manaus

(solid curve), the T/P measurements (data at 1 s), andthe difference time series. The computed rms of thedifferences is 45 cm. Except for the site of Tabatinga(290◦E, 4◦S; box 1), where the rms accuracy is poorer(∼ 80 cm), similar rms values are found at the othertwo sites: Itapeua (297◦E, 4◦S; box 3) and Manaca-puru (299.5◦E, 3.5◦S; box 4). In the latter two cases,the distances between T/P track intersection and in

639

I. de Oliveira Campos et al. / C. R. Acad. Sci. Paris, Sciences de la Terre et des planètes / Earth and Planetary Sciences 333 (2001) 633–643

Figure 4. Amazon River water level time series derived from the T/Pdata at two sites: track 102 and 63 (in m). Dots are T/P data at 10-dayintervals spatially averaged over the river width while the solid curveis constructed by interpolation with a Spline function.

Figure 4.Séries temporelles de niveau d’eau de l’Amazone, mesuréespar T/P (traces 102 et 63). Les points représentent les hauteurs T/P parcycle, moyennées sur la largeur du fleuve. La courbe en trait plein estobtenue par interpolation par une fonction Spline.

situ station are 7 and 70 km, respectively. Consideringthe large annual amplitude of the river level variation(10 to 15 m peak to peak), a half-meter accuracy of theT/P data is very encouraging. The estimated rms accu-racy is fully consistent with previous estimates madeby Birkett [4] with 3.7 years of data. She reported anrms accuracy of 60 cm at three comparison sites. Itis worth noting that the rms accuracy is higher overfloodplains (on the order of 20 cm) than over the river(see [4]). The reason for this is unclear and currentlyunder investigation.Figure 3b presents another exam-ple at the intersection between main river and tracknumbered 139. In this case, we clearly see the inad-equacy of T/P in providing data in low water season.The reason for this failure is not yet understood, as theriver width does not change significantly between lowflow and high flow periods. Inspection of T/P wave-forms may help clarifying why data are lacking in lowwater season at some locations.

4.2. Seasonal variations of the T/P-derived waterlevel time series

Here we present water level time series for twoselected tracks (track 102, box 1 and track 63, box4) along the main river where T/P measurementsconsistently cover the seasonal cycle.Figure 4 showsthe T/P-derived water level time series at the T/Ptrack intersections. Dots represent spatial averagesover the river width at 10-day interval. A solid curveis obtained by interpolation with a Spline function.The curves exhibit a clear seasonal signal, mostlyannual, of up to 10–15 m peak-to-peak amplitude.Maximum signal is observed from May to July,

Figure 5. Interannual water level time series derived from the T/Pdata in high water season at the intersection of nine selected tracks(identified by number) (in m).

Figure 5. Variations interannuelles du niveau de l’Amazone enpériodes de hautes eaux pour neuf sites.

which corresponds to the maximum flood period.This high water period follows the main rainy seasonby about three months. The most upstream curve(box 1) presents a mostly unimodal seasonal cyclewith a slight secondary maximum, occurring by theend of the year. The water level curve for track 63(box 4) shows a single maximum, with a regularannual cycle. These results are fully consistent withinformation given by the gauging stations. At siteswhere T/P succeeds in measuring water level inlow water season, the whole seasonal cycle can becorrectly described.

4.3. Interannual variations

To study the interannual signal, we considered thelocal series of maximum annual water levels, whichare well detected by nine different T/P tracks alongthe main stream of the Amazon River. To constructthe interannual time series we averaged over six suc-cessive T/P cycles, water level data on both sides ofthe seasonal maximum. This procedure leads to a sin-gle water level value per year. Corresponding time se-ries are shown infigure 5. Looking atfigure 5, twomain features are visible: (1) there is a well markeddeficit in year 1995, particularly intense in the west-ern portion of the river, and (2) a clear deficit in waterlevel can be observed in 1998 downstream from theconfluence of the Negro and Solimões Rivers. The lat-ter minimum can be related to the major 1997–1998ENSO event. Indeed several studies have establishedthat changes in atmospheric circulation over the trop-ical Pacific associated with ENSO cause variation inthe atmospheric circulation and precipitation regimeover South America, hence in Amazon River dis-charge [10, 13, 15]. In particular major ENSO events

640

I. de Oliveira Campos et al. / C. R. Acad. Sci. Paris, Sciences de la Terre et des planètes / Earth and Planetary Sciences 333 (2001) 633–643

produce pronounced low discharge over the centralportion of the Amazon River [21]. This will be dis-cussed in more details in the next section.

5. Precipitation over the Amazon basin

The water balance in a river basin can be describedby the water budget equation [23]:∂S/∂t = P–E–R,which links fluxes with changes in storage.R is thetotal discharge across the basin boundary (positive fornet outflow).R is usually taken to be river discharge atthe basin outlet.P is precipitation,E is evapotranspi-ration from the land surface andS represents the waterstored in the basin, which includes vegetation mois-ture, soil moisture, groundwater storage and surfacestorage (lakes, rivers, flooded areas and snow whereappropriate).t is the time.R andP are the most eas-ily quantifiable variables in the equation above.

Water level time series over the Amazon basin carryinformation on both superficial storage in open wa-ter bodies (lakes, rivers and flooded areas) and riverdischarges, as water level in a river section is relatedto river discharge in this section. In most river basins,and in particular in the Amazon basin, site discharge ismeasured directly, as frequently as possible, in orderto establish and update specific level–discharge rela-tionship (rating curve). Discharge time series are thendeduced from continuously measured water level timeseries, using the rating curve. Unfortunately the wa-ter level time series derived from T/P altimetry can-not be expressed in terms of discharge records, dueto the lack of field calibration at the correspondingsites. However, these water levels give valuable andappropriate spatial and temporal information on rela-tive discharge variations, since at first order the ratingcurve can be approximated by a linear relation.

On the assumption that streamflow records inte-grate spatial hydrological variability within the catch-ment basin, several studies have compared precipi-tation records to Amazon River discharge to detectcommon temporal variability patterns of climatic ori-gin [5, 21]. In order to get some insight into the pre-cipitation variability in the region and its possible in-fluence on the Amazon River level, we analysed pre-cipitation fields from Xie and Arkin [24] over the timespan 1993–1999. Note that over a basin as large as theAmazon basin, stream flow results from the integratedcontribution of precipitation over the catchment basin.The precipitation data set consists of monthly precip-itation grids (mesh size of 2.5◦ × 2.5◦). To highlightboth temporal and spatial variability, we applied anEmpirical Orthogonal Function (EOF) analysis [19,22] to the gridded precipitation fields. At each gridmesh, the seasonal signal (annual and semi annual cy-cles) has been removed in order to show up the in-terannual fluctuations. The EOF method is based on

a decomposition of a spatio-temporal varying field(here precipitation) into an uncorrelated linear com-bination of functions of the original variables, rankedby variance. The method implicitly assumes that thefirst few modes of the EOF decomposition define thedominant patterns of the signal.Figure 6 shows thespatial pattern and temporal evolution of the first EOFmode of precipitation in the Amazon basin. It ex-plains 42 % of the total variance. The temporal curveexhibits a very strong minimum at the end of 1997corresponding to the 1997–1998 ENSO. Accordingto the spatial map, the largest rainfall deficit is ob-served in the north-central part of the basin, east of theNegro and Solimoes confluence. It is precisely alongthe Amazon River portion extending between Manaus(300◦E, 3◦S) and Obidos (304◦E, 2◦S) that the T/P-derived water levels show a marked minimum in 1998(note that curves shown infigure 5 are based on singleyearly values). The T/P-based results are in full agree-ment with previous observations of hydrographic pa-rameters (water level, discharge) showing interannualvariability coupled to ENSO events. These oscilla-tions in river discharge are explained by the eastwardshift of the descending branch of the zonal circulationover the equatorial Pacific during ENSO years, lead-ing to a suppression of convection hence precipitationover the central Amazon basin [21]. The second mode(20 % of the total variance; not shown) presents an ex-tremum in 1995 in its temporal curve, correspondingto a minimum of precipitation over the Amazon Riverwest of longitude 305◦E. Again, this corresponds tothe observed 1995 water level minimum seen in theT/P data.

6. Discussion

This study has shown that satellite altimetry, in par-ticular the T/P mission, has the capability to moni-tor temporal variations in surface water level for largeriver basins, provided that the water area is largeenough for parasite land signal not to contaminatethe altimetric measurement. The main limitation ofthe altimetric techniques over the Amazon basin ap-pears to be the lack of water detection during low-water season. We have also indicated that presentwater height measurements are not optimised due tothe fact that the wet troposphere correction is lack-ing. This can be improved however by collecting inte-grated water vapour data from outputs of operationalglobal circulation models (or their re-analyses). Al-though very demanding, this would significantly im-prove the accuracy of continental water height mea-surements. Other interesting perspectives can be en-visaged to the future. They concern the use of ERS-1 and ERS-2 data whose spatial coverage is about

641

I. de Oliveira Campos et al. / C. R. Acad. Sci. Paris, Sciences de la Terre et des planètes / Earth and Planetary Sciences 333 (2001) 633–643

Figure 6. First mode of the EOF decomposition of precipitation anomalies over the Amazon basin (seasonal terms removed). Top: map of thespatial pattern (amplitude in mm·d−1). Bottom: temporal curve for 1993–1999.

Figure 6. Mode 1 de la décomposition en EOF des anomalies de précipitation sur le bassin amazonien entre 1993 et 1999 (après retrait desvariations saisonnières). En haut, carte spatiale (amplitude en mm·j−1) ; en bas, courbe temporelle.

four times denser than T/P (although their temporalresolution is 35 days instead of 10 days). As men-tioned above, altimetric heights were not providedover land. They can be computed however by retrack-ing waveforms. We are currently analysing wave-forms from the whole ERS-1 and ERS-2 missionsto provide a height database over continental sur-faces. This 10-year long time series will be soon ex-

tended with the observations of ENVISAT, sched-uled to be launched in early 2002 on the same or-bit as ERS-1 and ERS-2, i.e., with the same spatio-temporal coverage. With such a data set, it will bepossible to monitor the spatio-temporal water levelvariations over rivers, floodplains and wetlands, witha ground resolution of about 50 km. The applica-tions include automatic detection of water over the

642

I. de Oliveira Campos et al. / C. R. Acad. Sci. Paris, Sciences de la Terre et des planètes / Earth and Planetary Sciences 333 (2001) 633–643

drainage basin and systematic mapping of wet areasin low and high water seasons, the estimate of sea-sonal and interannual water mass change involved insurface water level fluctuations with inference on theregional water balance and hydrology, and the esti-

mate of discharge rate from altimetry-derived waterlevels when rating curves are established. These per-spectives are not only of interest for the Amazon basinbut more generally for other major river basins in theworld.

Acknowledgements. This work was supported by the University of São Paulo and the Federal University of Uberlândia (Brazil), CNES, CNRS,IRD, the University of Toulouse and ANEEL through the HiBAm Programme. It received significant support from CAPES–Cofecub (Collaborationuniversitaire franco-brésilienne) and PNTS (Programme national de télédétection spatiale). We thank P. Vincent, F. Rémy, and N. Mognard-Campbell for useful discussions on the T/P data processing over land. We also thank J.-L. Guyot and N. Filizola for helpful informations about theAmazon Basin. Finally we are grateful to P. Ribstein for careful review of the original manuscript.

References

[1] AVISO/Altimetry, AVISO user handbook for mergedTopex/Poseidon products, AVI-NT-02-101, Edition 3.0, Centrenational d’études spatiales, France, 1996, 195 p.

[2] Birkett C.M., Radar altimetry: a new concept in monitoringlake level changes, EOS Trans., AGU 75 (24) (1994) 273–275.

[3] Birkett C.M., The contribution of Topex/Poseidon to the globalmonitoring of climatically sensitive lakes, J. Geophys. Res. 100(1995) 25179–25204.

[4] Birkett C.M., Contribution of the Topex NASA radar altimeterto the global monitoring of large rivers and wetlands, Water Resour.Res. 34 (5) (1998) 1223–1239.

[5] Cauduro Dias de Paiva E.M., Clarke R.T., Time trends inrainfall records in Amazonia, Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 76 (1995)2203–2211.

[6] Cazenave A., Bonnefond P., DoMinh K., Caspian sea levelfrom Topex/Poseidon altimetry: level now falling, Geophys. Res.Lett. 24 (1997) 881–884.

[7] Costa M.H., Foley J.A., A comparison of precipitation data setsfor the Amazon basin, Geophys. Res. Lett. 25 (1998) 155–158.

[8] Costa M.H., Foley J.A., Trends in the hydrological cycle of theAmazon basin, J. Geophys. Res. 104 (1999) 14189–14198.

[9] Guyot J.-L., Callede J., Molinier M., Guimaraes V.,Oliveira E. de, La variabilité hydrologique actuelle du bassin de l’A-mazone ; conséquences climatiques et hydrologiques des événementsENSO à l’échelle régionale et locale, Inamhi–Orstom, Quito, 1997.

[10] Guyot J.-L. et al., Hydrological characteristics of the AmazonBasin, Hydrol. Process. (submitted).

[11] Koblensky C.J., Clarke R.T., Brenner A.C., Frey H., Measure-ment of river level variations with satellite altimetry, Water Resour.Res. 29 (1993) 1839–1848.

[12] Marengo J., Tomasella J., Uvo C.R., Trends in stream flowand rainfall in tropical South America: Amazonia, eastern Brasil andNorthwestern Peru, J. Geophys. Res. 103 (1998) 1175–1783.

[13] Mercier F., Cazenave A., Maheu C., Interannual lake levelvariations in Africa from Topex–Poseidon satellite altimetry, GlobalPlanet. Change (in press).

[14] Molinier M., Guyot J.-L., Cochonneau G., Guimaraes V.,La variabilité hydrologique du bassin amazonien et la circulationatmosphérique océanique, Hydrological and geochemical processesin large scale river basins, Manaus, 1999.

[15] Morris C.S., Gill S.K., Evaluation of the Topex/Poseidonaltimeter system over the Great Lakes, J. Geophys. Res. 99 (1994)24527–24539.

[16] Morris C.S., Gill S.K., Variation of Great Lakes waters fromGeosat altimetry, Water Resour. Res. 30 (1994) 1009–1017.

[17] National Water Assessment Group, Water, the potential con-sequences of climate variability and change, US Department of theInterior, Washington DC, 2001.

[18] Ponchaut F., Cazenave A., Continental lake level variationsfrom Topex/Poseidon (1993–1996), C. R. Acad. Sci. Paris, sérieIIa 326 (1998) 13–20.

[19] Preisendorfer R.W., in: Mobley C. (Ed.), Principal componentanalysis in meteorology and oceanography, Elsevier, New York,1998, 418 p.

[20] Rao V.B., Cavalcanti I.F.A., Hada K., Annual variation ofrainfall over Brazil and water vapor characteristics over SouthAmerica, J. Geophys. Res. 101 (1996) 26539–26551.

[21] Richey J.E., Nobre C., Deser C., Amazon River discharge andclimate variability, Science 246 (1989) 101–102.

[22] Toumazou V., Cretaux J.-F., Using a Lanczos eigen solver inthe computation of Empirical Orthogonal Functions, Mon. WeatherRev. 129 (5) (2001) 1243–1250.

[23] Wood E.F., Lettenmaier D., Liang X., Nijssen B, Wetzel S.W.,Hydrological modeling of continental-scale basins, Annu. Rev. EarthPlanet. Sci. 25 (1997) 279–300.

[24] Xie P., Arkin P.A., An intercomparison of gauge observationsand satellite estimates of monthly precipitation, J. Appl. Meteorol. 34(1995) 1143–1160.

643