Southern Sudan: an opportunity for NTD control and elimination?

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

5 -

download

0

Transcript of Southern Sudan: an opportunity for NTD control and elimination?

Southern Sudan: An opportunity for NTD control andelimination?

John Rumunu1, Simon Brooker2,3, Adrian Hopkins4, Paul Emerson5, Fasil Chane6,7, andJan Kolaczinski2,8,*

1 Ministry of Health, Government of Southern Sudan 2 Department of Infectious & TropicalDiseases, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, London, United Kingdom. 3 MalariaPublic Health and Epidemiology Group, KEMRI/Wellcome Trust Collaborative Programme,Nairobi, Kenya 4 Mectizan Donation Program, Decatur, Georgia, USA 5 The Carter Center,Atlanta, Georgia, USA 6 Christoffel Blindenmission (CBM), Southern Sudan 7 Southern SudanOnchocerciasis Task Force, Rumbek, Southern Sudan 8 Malaria Consortium Africa, Kampala,Uganda

AbstractSouthern Sudan has been ravaged by decades of conflict and is thought to have one of the highestburdens of neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) in the world. Health care delivery, including effortsto control or eliminate NTDs, is severely hampered by a lack of infrastructure and health systems.However, the post-conflict environment and Southern Sudan's emerging health sector provide theunprecedented opportunity to build new, innovative programmes targeting NTDs. This articledescribes the current status of NTDs and their control in Southern Sudan and outlines theopportunities for the development of evidence-based, innovative implementation of NTD control.

Keywordsneglected tropical diseases; control; elimination; post-conflict; Southern Sudan

An opportunity for coordinated controlNeglected tropical diseases (NTDs) are a range of diseases that occur in conditions ofpoverty and frequently overlap in endemic countries [http://www.who.int/neglected_diseases/en]. Funding for their control and elimination has recently seen adramatic expansion, with an emphasis on co-administration of preventive chemotherapy(PCT) [1]. However, operational experience in delivering PCT packages has, to date, beenfrom countries with relatively well-established health systems [e.g. 2-5]. Little is knownabout implementation in post-emergency settings, where delivery structures are lessdeveloped or absent. One such setting is Southern Sudan which, until recently, was plaguedby a series of conflicts since independence in 1956 [6]. The cessation of conflict coupledwith the commitment of the Ministry of Health (MoH) of the Government of SouthernSudan (GoSS) has yielded new opportunities and funding for NTD control, notably supportfrom the US Agency for International Development to develop an integrated NTD controlprogramme. There exists therefore a unique opportunity to develop an integrated programmefrom scratch, and to generate crucial evidence on cost and cost-effectiveness in the process.

* Corresponding author: Malaria Consortium Africa, Plot 2A, Sturrock Road, Kololo, Kampala, Uganda, PO Box 8045;[email protected], Phone: (256-0312) 300430, Fax: (256-0312) 300425.

Europe PMC Funders GroupAuthor ManuscriptTrends Parasitol. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2009 August 19.

Published in final edited form as:Trends Parasitol. 2009 July ; 25(7): 301–307. doi:10.1016/j.pt.2009.03.011.

Europe PM

C Funders A

uthor Manuscripts

Europe PM

C Funders A

uthor Manuscripts

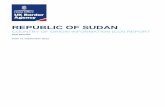

Post-conflict progress and challengesSouthern Sudan and the Khartoum Government signed on 9 January 2005 theComprehensive Peace Agreement, ending decades of civil war. Health systems are nowbeing rebuilt, providing opportunities and funding to integrate the control of multiple NTDs.However, the country's recent history, as well as its sheer size, also pose several challenges[7]. Southern Sudan covers an area of 231,177 square miles (Figure 1) but has an estimatedpopulation of 11 million at the most, which equates to 47 people per square mile. Migrantpopulations and the return of refugees and internally displaced persons result in constantlyfluctuating population figures. In 2004, 98% of the population lived in rural areas [Factsabout South Sudan (http://www.codecan.org/media/PLS-%20Facts%20about%20South%20Sudan%202008.pdf)]. Physical, health and education infrastructure is largely absent andmany areas are only accessible by plane, boat, four-wheel drive, or foot, especially duringthe rainy season. The proportion of the population with access to a health facility has beenestimated below 25% [7,8], while in 2002 just over 20% of school-age children wereenrolled in schools [Towards a baseline: Best estimates of social indicators for SouthernSudan (http://www.unicef.org/media/media_21825.html)].

Notwithstanding such challenges, the ongoing transition towards development and itsassociated lack of entrenched government structures and processes provide greatopportunities to improve public health, including NTD control. For such improvements totake place, it is essential to build up a credible evidence-base to understand theepidemiology of infection and disease, and develop, as well as appropriately implement,intervention strategies.

Neglected tropical diseases in Southern SudanTwelve NTDs are endemic to Southern Sudan (Table 1) [Neglected Tropical Disease inSouthern Sudan (http://www.malariaconsortium.org/data/files/pages/ntds_southern_sudan.pdf)]. However, as in all post-conflict settings, reliable diseasesurveillance data are sparse. Estimates of incidence or prevalence are based either on passivecase-detection [9,10] or localized surveys undertaken in areas where specific NTDs areknown or suspected to occur [11-14]. Although comprehensive empirical data are few, thosethat do exist indicate that lymphatic filariasis (LF), schistosomiasis, soil-transmittedhelminth (STH) and trachoma are endemic over large areas, whereas visceral leishmaniasis(VL), human African trypanosomiasis (HAT), Buruli ulcer and leprosy occur more focally.To date, comprehensive epidemiological mapping has been undertaken for onlyonchocerciasis, loiasis and Guinea worm. Determining the prevalence and distribution of theother NTDs remains an important operational necessity, because NTD transmission isheterogeneous and scarce resources for control need to be geographically targeted [15].

Current NTD control strategiesDespite decades of civil unrest, progress has been made with the control of some NTDs(Table 2). These efforts can be broadly categorised as: (i) large-scale programmes targetingat least 10% of the population (onchocerciasis and Guinea worm; see Figure 1); (ii) smaller,ad-hoc public health campaigns (STH and trachoma); and (iii) treatment provided, tovarying degrees, by health facilities on an in-patient basis (VL, HAT) and through outreach(Buruli ulcer, leprosy). Since the populations at risk are not precisely known, it is generallynot possible to reliably estimate coverage rates or their change over recent years.

Implementation of both onchocerciasis and Guinea worm control is through community-based structures, utilizing volunteers for community-directed treatment with ivermectin(CDTI) and for distribution of water filters and surveillance, respectively. Trachoma control

Rumunu et al. Page 2

Trends Parasitol. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2009 August 19.

Europe PM

C Funders A

uthor Manuscripts

Europe PM

C Funders A

uthor Manuscripts

is currently integrated with the Guinea worm eradication program in Eastern Equatoria andJonglei States, and consists of the SAFE strategy with its four components of eyelid surgery(S), antibiotics to treat the community pool of infection (A), facial cleanliness (F), andenvironmental changes (E). To date, deworming against STH has been carried out duringnational immunization days and schistosomiasis treatment is being provided by some healthfacilities.

Treatments for VL, HAT, leprosy and Buruli ulcer are considered too toxic, lengthy ordifficult to be delivered through community-based mechanisms, and are only available athealth facilities or through outreach, if at all. Historically, treatment services for VL andHAT were provided by non-governmental organizations during epidemics (see, for example,Ref [16]), allowing temporary expansion of service coverage [17,18]. Activities werescaled-back shortly after the disease was considered to be under control, leaving opportunityfor disease resurgence [19-21]. Current access to and quality of treatment to VL and HAT,as well as leprosy and Buruli ulcer, remains inadequate [10].

Building on existing MDA structuresOngoing post-conflict reconstruction provides a number of key opportunities to improve oncurrent NTD control, which are outlined below and in Box 1. An immediate opportunity forexpanding NTD control is through integration of PCT delivery into the CDTI onchocerciasisnetwork. Delivery of albendazole can readily be added to annual ivermectin distribution inareas where onchocerciasis and LF are co-endemic, with the collateral benefit of controllingSTH, scabies and lice [22]. Southern Sudan will start co-administration of ivermectin andalbendazole through CDTI structures in 2009.

In some Guinea worm endemic areas, health education and distribution of antibiotics fortrachoma control have been integrated into the community-based Guinea worm activities.Anecdotal reports suggest that this has been popular with the communities. Once thetransmission of Guinea worm has been interrupted and the network needs to be maintainedfor surveillance, Southern Sudan will have the opportunity to expand the existingintegration, both geographically and in scope.

Together the CDTI and Guinea worm network provide about 80% geographic coverage(Figure 1). This means that other mechanisms are required to deliver PCT to parts of thecountry where neither onchocerciasis nor Guinea worm are endemic, as well as withinadministrative units where distribution of these two diseases is focal and where the existingnetworks do not reach all individuals eligible for other treatments. This is particularlyrelevant for elimination of LF, a disease that tends to be endemic over large areas [23]. Co-administration through the expanded programme on immunization provides one alternativedelivery structure, as it was successfully used in 2006 and 2007 for mass de-worming withalbendazole. Another option may be de-worming for schistosomiasis and STH throughschools; an approach that is already well established elsewhere in the region [24-26].However, distribution through schools, as well as modification of the curriculum to improveknowledge, attitudes and practices related to NTD control, will only become viable oncerebuilding of infrastructure has progressed and school attendance has substantiallyincreased. Meanwhile, ongoing campaigns for distribution of long-lasting insecticidal nets(LLINs) present an interim opportunity for PCT distribution until LLIN coverage has beenscaled-up [3].

In the medium-term, Southern Sudan will have the opportunity to develop an innovativeplatform for community directed delivery of PCT and other interventions (e.g. LLINs andvitamin A supplementation). Building on a recent TDR study [Community DirectedInterventions for major health problems in Africa (http://www.who.int/tdr/svc/publications/

Rumunu et al. Page 3

Trends Parasitol. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2009 August 19.

Europe PM

C Funders A

uthor Manuscripts

Europe PM

C Funders A

uthor Manuscripts

tdr-research-publications/community-directed-interventions-health-problems)], astandardized delivery platform could be developed. A common set of interventions could beidentified that address Southern Sudan's needs and are suitable for integration, and donorswould then be asked to invest into the platform, instead of supporting specific diseases. Thedelivery platform could be part of a health facility – community linkage, and pre-servicetraining of the country's new nurses and doctors could emphasize supervision andmanagement of the platform as a central part of their job. To inform the development ofsuch platform, more in-country experience with integration will be needed.

For VL, HAT, leprosy and Buruli ulcer, where confirmative diagnosis is required beforeinfected individuals receive treatment [27-30], the existence of community-based MDAstructures cannot be harnessed to provide mass treatment, but presents an opportunity toimprove treatment outcomes and to reduce transmission through prevention. CDDs can betrained to provide health education, case identification, early referral and community follow-up.

Integration into multi-functional health care deliveryFor those NTDs not suitable for MDA, both diagnosis and treatment are only available at afew facilities, often many hours if not days away from endemic communities. As a result,infected individuals generally present late or not at all, resulting in high morbidity andmortality [e.g. 31]. With Southern Sudan having the highest caseload of VL in Africa [32]and being among the top three endemic countries for HAT [21] there is an obvious andurgent need for improvement. As mentioned above, such improvement should involve theaffected communities where feasible, but also requires better and more accessible case-management. Ongoing upgrading of facility-based health care undertaken by the MoH-GoSS and partners provides an important opportunity to ensure that the skills and supplies toprovide routine NTD diagnosis and treatment are put in place, and that a link between thefacilities and the communities is being established. Initial steps to do so have been taken bythe MoH-GoSS with considerable support from WHO and other agencies. The requireddrugs and other supplies have been included in the essential drug kit list and training ofnational staff, including those operating at the periphery, on diagnostic and treatmentprocedures is ongoing.

New policies and strategiesUntil 2005, communicable diseases in Southern Sudan were either managed using strategiesdeveloped by the Khartoum Government or according to the protocols of individual aidagencies. Since then, the MoH-GoSS has put in place a number of new or revised strategieswith the aims of: i) standardizing diagnosis, treatment and prevention among implementingpartners operating in the South, and ii) providing a framework for the MoH-GoSS and otherdevelopment partners to allocate funding. The most recently addition specifically addressesintegrated NTD control [Integrated Control of Neglected Tropical Diseases (http://www.malariaconsortium.org/data/files/ntd_ss_strategic_plan_june_2008_final.doc).

Revision or development of new strategies continues to provide opportunities to include newevidence and to identify specific areas requiring further in-country research (see below).Due to the absence of large government bureaucracies such strategic planning processes canbe undertaken relatively quickly and with extensive consultation. This dynamic environmentalso allows for specific implementation needs, such as a strong government commitment tocommunity-based delivery, to be readily incorporated into emerging health policies.

More generally, improvements in environmental hygiene are the ultimate answer to thecontrol and elimination of many NTDs, but for Southern Sudan as for many low-income

Rumunu et al. Page 4

Trends Parasitol. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2009 August 19.

Europe PM

C Funders A

uthor Manuscripts

Europe PM

C Funders A

uthor Manuscripts

countries these are expensive and represent long-term objectives. Multiple agencies areworking with the GoSS to strengthen water, hygiene and sanitation infrastructure, andefforts should be made to ensure integration between NTD control and governmentdepartments coordinating the provision of water and sanitation. Here there is opportunity forcross-sectoral collaboration and influencing strategies and policies, for example to formulatestandardised, rather than disease-specific, education on water and sanitation and to target theconstruction of new boreholes and latrines to areas with high population densities and a highrisk of specific NTDs.

Strengthening the evidence-baseIntegrated NTD control has now been initiated in at least ten African countries, although todate, there are few empirical data on the health benefits and cost savings of an integratedapproach over and above single-disease control programmes [4,33,34]. There thus remainsan urgent need to strengthen the evidence-base for integrated control. Southern Sudanprovides particular opportunities to do so, because all of the targeted NTDs are endemic andmost of them have not been mapped. This means that extensive epidemiological surveys areneeded. With the aim of saving time and money, the feasibility of an integrated survey toolcovering a range of NTDs is being investigated. Integrated surveys will need to overcome anumber of important difference in epidemiologies and survey methodologies of NTDs[15,35], and thus generate useful information to guide similar undertakings elsewhere.

It is also apparent that the commonly quoted annual MDA cost of US$ 0.4 – 0.5 per person[36,37] are not applicable in Southern Sudan. Actual cost data is thus being collected andwill be used to generate evidence on cost and cost-effectiveness of this approach. Themethodology and costing templates used will be available for similar data collectionelsewhere, providing an opportunity to generate figures that can be readily comparedbetween countries.

Lastly, the planned expansion of co-administration of PCT through community-basedstructures and campaigns will require exploration of new and innovative deliveryapproaches, to ensure that full coverage (both geographically and of the eligible population)is achieved and can be retained. Amongst others, this will provide opportunities tocontribute to the evidence-base on recruitment, training, supervision and retention ofcommunity drug distributors (CDDs), and on factors associated with coverage. At present,the Southern Sudan Onchocerciasis Task Force already faces the challenge that about 30%of CDDs discontinue their involvement in CDTI every year, resulting in considerable costsfor recruitment and training of new volunteers. Useful insight on improving CDD retentionhas been gained from other countries with well-established onchocerciasis controlprogrammes [e.g. 42], as has been on factors associated with coverage [e.g. 43]. However,there is as yet limited evidence on how best to address these issues once a package of drugsor other interventions is delivered through community-based mechanisms, though TDR andothers have recently started to fill this knowledge gap [44, Community DirectedInterventions for major health problems in Africa (http://www.who.int/tdr/svc/publications/tdr-research-publications/community-directed-interventions-health-problems)].

Concluding remarksInformation on the distribution and burden of NTDs in Southern Sudan is limited, butexisting data consistently indicate that this is a country with a high burden and great need. Initself, this is not unlike many other developing countries. What sets Southern Sudan apart isthat most NTDs are endemic, that most of them have benefited from little control and thatinfrastructure and systems are practically absent. Though this presents great challenges, italso offers great potential to increase treatment coverage for co-endemic NTDs, integrate

Rumunu et al. Page 5

Trends Parasitol. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2009 August 19.

Europe PM

C Funders A

uthor Manuscripts

Europe PM

C Funders A

uthor Manuscripts

more complex case-management into facility-based health care delivery and strengthen thelink between communities and health facilities. This unprecedented opportunity to buildevidence-based systems for NTD control or elimination needs to be maximised now whilerebuilding of the health sector is ongoing.

Box 1

Key opportunities and outstanding key questions for Southern Sudan

Opportunities1. To build on existing solid structures for MDA delivery developed during the

war, and expand their scope and geographical coverage at a unique time ofhealth sector rebuilding. In the medium term, a common delivery platform forPCT and other interventions (e.g. LLINs, vitamin A supplementation) couldbe developed as part of a health facility – community linkage.

2. To address the control of NTDs not suitable for MDA through appropriateintegration into multi-functional health care delivery at facility level, andthrough strengthening of the link between communities and health facilities.

3. To ensure that new policies and strategies incorporate MDA of PCT andother NTDs treatment and prevention as part of Primary Health Care.

4. To generate essential evidence that may allow better coordination/integrationof mapping and MDA activities, thus reducing time and costs associated withoperating in very difficult terrain, as well as contributing to the internationalunderstanding of the cost and cost-effectiveness of NTD control/elimination.

Questions1. Which NTDs are endemic where? Both MDA and health facility based NTD

interventions need to be targeted based on disease prevalence. For the majorityof NTDs this information is not available in sufficient detail.

2. How best to integrate the various criteria for NTD mapping? Trachoma, inparticular, requires costly and detailed epidemiological surveys beforeazithromycin donation can be requested. There is an urgent need to developsimplified mapping procedures for trachoma and to establish how best tointegrate survey procedures for LF, schistosomiasis, and STH, as well astrachoma.

3. What is the actual cost of conducting MDA of PCT? Few cost data fordelivery of integrated MDA are currently available. A cost analysis, followingguidelines for economic evaluation of health care programmes, will be requiredto allow appropriate budgeting and to be used in the cost-effectivenessevaluation of integrated MDA.

4. What is/are the vector(s) of lymphatic filariasis and what is the vectorialcapacity? It is assumed that Anopheles gambiae and A. funestus mosquitoes areresponsible for LF transmission in Southern Sudan, based on data fromneighboring Uganda [38]. Whether this is the case and what the competence ofthe vector(s) is should be determined, as it is an important determinant of thenumber of MDAs required and hence of the overall cost of LF elimination [39].

5. How to monitor and evaluate the integrated NTD programme? Standardizedtool for monitoring and evaluation are need that address issues such as: i) Howbest to collect data, particularly once prevalence decreases, ii) Which datacollection methods can be integrated, and iii) How frequently data need to be

Rumunu et al. Page 6

Trends Parasitol. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2009 August 19.

Europe PM

C Funders A

uthor Manuscripts

Europe PM

C Funders A

uthor Manuscripts

collected, particularly in areas where communications are poorly developed andwhere population access is intermittent and expensive.

AcknowledgmentsWe wish to thank all the individuals and organizations that have contributed to the control of NTDs in SouthernSudan over the last decades. Without their dedication, many lives would have been lost and many people would nothave been cured from disabilities.

The information presented in this publication was collated for a comprehensive situation analysis on NTDs recentlypublished by the Ministry of Health, Government of Southern Sudan (http://www.malariaconsortium.org/data/files/pages/ntds_southern_sudan.pdf). Major contributions to the analysis were made by Jose Ruiz, Michaleen Richer,Samson Baba, Lasu Hickson, Karinya Lewis, Steven Becknell and Samuel Makoy. Development of the situationanalysis was led by Malaria Consortium [http://www.malariaconsortium.org] and funded by COMDIS, a ResearchProgramme Consortium coordinated by the Nuffield Centre for International Health and Development, Universityof Leeds, with funds from the Department for International Development, UK. COMDIS also funded MalariaConsortium to lead writing of this publication. Simon Brooker is supported by a Wellcome Trust CareerDevelopment Fellowship (081673). Current scale-up of integrated NTD control in Southern Sudan is funded by theUS Agency for International Development, through RTI International.

References1. Lawrence D. Bush's plan for tackling parasitic diseases set out. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2008; 8:743.

2. Hopkins DR, et al. Lymphatic filariasis elimination and schistosomiasis control in combination withonchocerciasis control in Nigeria. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2002; 67:266–272. [PubMed: 12408665]

3. Blackburn BG, et al. Successful integration of insecticide-treated bed net distribution with massdrug administration in central Nigeria. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2006; 75:650–655. [PubMed:17038688]

4. Kolaczinski JH, et al. Neglected tropical diseases in Uganda: the prospect and challenge ofintegrated control. Trends Parasitol. 2007; 23:485–493. [PubMed: 17826335]

5. Mohammed KA, et al. Triple co-administration of ivermectin, albendazole and praziquantel inZanzibar: A safety study. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2008; 2:e171. [PubMed: 18235853]

6. Stephen, MJ.; de Waal, A. Can Sudan Escape its Intractability?. In: Crocker; Chester, A.; Hampson,Fen Osler; Aall, Pamel, editors. Grasping the Nettle: Analyzing Cases of Intractable Conflict.United States Institute of Peace; Washington, D.C.: 2005. p. 161-182.

7. Wakabi W. Peace has come to southern Sudan, but challenges remain. Lancet. 2006; 368:829–830.[PubMed: 16958158]

8. Moszynski P. Lack of trained personnel thwarts Sudan's plans to rebuild health services. BMJ. 2008;337:a2954. [PubMed: 19074225]

9. Collin SM, et al. Conflict and kala-azar: Determinants of adverse outcomes of kala-azar amongpatients in Southern Sudan. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2004; 38:612–619. [PubMed: 14986243]

10. Kolaczinski JH, et al. Kala-azar epidemiology and control, Southern Sudan. Emerg. Infect. Dis.2008; 14:664–666. [PubMed: 18394290]

11. Ngondi J, et al. The epidemiology of trachoma in Eastern Equatoria and Upper Nile States,Southern Sudan. Bull. WHO. 2005; 83:904–912. [PubMed: 16462982]

12. Ngondi J, et al. Prevalence and cause of blindness and low vision in Southern Sudan. PLoS Med.2006; 3:e477. [PubMed: 17177596]

13. King JD, et al. The burden of trachoma in Ayod county of Southern Sudan. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis.2008; 2:e299. [PubMed: 18820746]

14. Deganello R, et al. Schistosoma haematobium and S. mansoni among children, Southern Sudan.Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2007; 13:1504–1506. [PubMed: 18257996]

15. Brooker S, et al. Rapid mapping of schistosomiasis and other neglected tropical diseases in thecontext of integrated control programmes in Africa. Parasitology. 2009 in press.

16. Seaman J, et al. The epidemic of visceral leishmaniasis in Western Upper Nile, Southern Sudan:course and impact from 1984-1994. Int. J. Epidemiol. 1996; 25:862–871. [PubMed: 8921468]

Rumunu et al. Page 7

Trends Parasitol. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2009 August 19.

Europe PM

C Funders A

uthor Manuscripts

Europe PM

C Funders A

uthor Manuscripts

17. Ritmeijer K, Davidson R. Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene Joint Meeting withMédecins Sans Frontières at Manson House, London, 20 March 2003. Field research inhumanitarian medical programmes. Médecins Sans Frontières interventions against kala-azar inthe Sudan, 1989-2003. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2003; 97:609–613. [PubMed: 16134257]

18. Balasegaram M, et al. Examples of tropical disease control in the humanitarian medicalprogrammes of MSF and Merlin. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2006; 100:327–334. [PubMed:16289631]

19. Moore A, et al. Resurgence of sleeping sickness in Tambura county, Sudan. Am. J. Trop. Med.Hyg. 1999; 61:315–318. [PubMed: 10463686]

20. Moore A, Richer M. Re-emergence of epidemic sleeping sickness in Southern Sudan. Trop. Med.Int. Health. 2001; 6:342–347. [PubMed: 11348529]

21. Simarro PP, et al. Eliminating human African trypanosomiasis: where do we stand and what comesnext? PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2008; 5:e55.

22. Ottesen EA, et al. The Global Programme to Eliminate Lymphatic Filariasis: Health impact after 8years. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2008; 2:e317. [PubMed: 18841205]

23. Gyapong JO, Remme JH. The use of grid sampling methodology for rapid assessment of thedistribution of bancroftian filariasis. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2001; 95:681–686. [PubMed:11816445]

24. Guyatt HL, et al. Evaluation of efficacy of school-based anthelmintic treatments against anaemia inchildren in the United Republic of Tanzania. Bull. WHO. 2001; 79:695–703. [PubMed: 11545325]

25. Kabatereine NB, et al. Impact of a national helminth control programme on infection andmorbidity in Ugandan schoolchildren. Bull. WHO. 2007; 85:91–99. [PubMed: 17308729]

26. Brooker S, et al. Cost and cost-effectiveness of nationwide school-based helminth control inUganda: intra-country variation and effects of scaling-up. Health Policy Plan. 2008; 23:24–35.[PubMed: 18024966]

27. Walker SL, Lockwood DNJ. Leprosy. Clin. Dermatol. 2007; 25:165–172. [PubMed: 17350495]

28. Chappuis F, et al. Visceral leishmaniasis: what are the needs for diagnosis, treatment and control?Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2007; 5:873–882. [PubMed: 17938629]

29. Fèvre EM, et al. Human African trypanosomiasis: Epidemiology and control. Adv. Parasitol. 2006;61:167–221. [PubMed: 16735165]

30. Wansbrough-Jones M, Phillips R. Buruli ulcer: emerging from obscurity. Lancet. 2006; 367:1849–1858. [PubMed: 16753488]

31. Collin SM, et al. Unseen Kala-Azar Deaths in Southern Sudan (1999-2002). Trop. Med. Int.Health. 2006; 2:509–512. [PubMed: 16553934]

32. Reithinger R, et al. Visceral leishmaniasis in eastern Africa - current status. Trans. R. Soc. Trop.Med. Hyg. 2007; 101:1169–1170. [PubMed: 17632193]

33. Brady P, et al. Projected benefits from integrating NTD programs in sub-Saharan Africa. TrendsParasitol. 2006; 22:285–291. [PubMed: 16730230]

34. Lammie PJ. A blueprint for success: integration of neglected tropical disease control programmes.Trends Parasitol. 2006; 22:313–321. [PubMed: 16713738]

35. Brooker S, Utzinger J. Integrated disease mapping in a polyparasitic world. Geospatial Health.2007; 2:141–146. [PubMed: 18686239]

36. Fenwick A, et al. Achieving the millennium development goals. Lancet. 2005; 365:1029–1030.[PubMed: 15781095]

37. Champagna A, et al. Neglected Tropical Diseases: Challenges, progress, and hope. Minn. Med.2008; 91:42–44.

38. Onapa A, et al. Lymphatic filariasis in Uganda: Baseline investigation in Lira, Soroti and Katakwidistricts. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2001; 95:161–167. [PubMed: 11355548]

39. Kyelem D, et al. Determinants of success in national programs to eliminate lymphatic filariasis: Aperspective identifying essential elements and research needs. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2008;79:480–484. [PubMed: 18840733]

40. Mukhtar MM, et al. The burden of Onchocerca volvulus in Sudan. Ann. Trop. Med. Parasitol.1998; 92(Suppl. 1):S129–S131. [PubMed: 9861278]

Rumunu et al. Page 8

Trends Parasitol. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2009 August 19.

Europe PM

C Funders A

uthor Manuscripts

Europe PM

C Funders A

uthor Manuscripts

41. Hopkins DR, et al. Dracunculiasis eradication: neglected no longer. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2008;79:474–479. [PubMed: 18840732]

42. Katabarwa, et al. In rural Ugandan communities the traditional kinship/clan system is vital to thesuccess and sustainment of the African Programme for Onchocerciasis Control. Ann. Trop. Med.Parasitol. 2000; 94:485–495. [PubMed: 10983561]

43. Brieger, et al. Factors associated with coverage in community-directed treatment with ivermectinfor onchocerciasis control in Oyo State, Nigeria. Trop. Med. Int. Health. 2002; 7:11–18. [PubMed:11851950]

44. Ndyomugyenyi R, Kabatereine N. Integrated community-directed treatment for the control ofonchocerciasis, schistosomiasis and intestinal helminths infections in Uganda: advantages anddisadvantages. Trop. Med. Int. Health. 2003; 8:997–1004. [PubMed: 14629766]

Rumunu et al. Page 9

Trends Parasitol. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2009 August 19.

Europe PM

C Funders A

uthor Manuscripts

Europe PM

C Funders A

uthor Manuscripts

Figure 1.Maps showing (a) the location of Southern Sudan in Africa, its ten states and major towns,highlighting its large size and low population density, (b) areas of Southern Sudan withstructures for onchocerciasis control, either in the form of community-drug distributors (red,hatched) or supervision centres for community-directed treatment with ivermectin (red, nothatched), (c) areas covered by the community-based network for Guinea worm eradication,and (d) trachoma-endemic areas already targeted with the SAFE strategy through the Guineaworm network. Both community-based structures shown in (b) and (c) are suitable foradditional mass drug administration (MDA) of preventive chemotherapy (PCT).

Rumunu et al. Page 10

Trends Parasitol. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2009 August 19.

Europe PM

C Funders A

uthor Manuscripts

Europe PM

C Funders A

uthor Manuscripts

Europe PM

C Funders A

uthor Manuscripts

Europe PM

C Funders A

uthor Manuscripts

Rumunu et al. Page 11

Tabl

e 1

NT

Ds

in S

outh

ern

Suda

n

Par

asit

eD

isea

seE

tiol

ogic

Age

ntD

istr

ibut

iona

Bur

den

Ref

eren

ce

Prot

ozoa

nV

isce

ral

Lei

shm

ania

sis

Lei

shm

ania

don

ovan

iU

nity

, Jon

glei

, UN

and

EE

Cyc

lic: 5

00–

9000

cas

espe

r ye

ar10

Hum

an A

fric

anT

rypa

noso

mia

sis

Try

pano

som

a br

ucei

gam

bien

seW

E, C

E, i

sola

ted

foci

in E

E1

– 2

mill

ion

peop

le a

tri

sk21

, b, c

T.b

. rho

desi

ense

His

tori

cal r

epor

ts in

Jon

glei

and

EE

No

rece

nt r

epor

ts

Bac

teri

alT

rach

oma

Chl

amyd

ia tr

acho

mat

isSu

rvey

ed a

reas

incl

ude

coun

ties

in E

E, C

E, J

ongl

ei,

UN

and

one

cou

nty

inN

BE

G

At l

east

3.9

mill

ion

11-1

3

Bur

uli u

lcer

Myc

obac

teri

um u

lcer

ans

WE

1000

+ c

ases

c

Lep

rosy

Myc

obac

teri

um le

prae

Popu

latio

n in

all

10 s

tate

s at

risk

In 2

006,

1,0

60 n

ew c

ases

wer

e re

port

edc

Hel

min

ths

Soil

- T

rans

mitt

edH

elm

inth

sA

scar

is lu

mbr

icoi

des,

Tri

chur

is tr

ichi

ura,

Hoo

kwor

m (

Spec

ies

unco

nfir

med

)

Prob

ably

all

10 s

tate

s,es

peci

ally

EE

, CE

and

WE

Unk

now

nc

Lym

phat

ic f

ilari

asis

Wuc

here

ria

banc

roft

iM

appi

ng n

ot c

ompl

eted

, but

prob

ably

all

10 s

tate

sU

nkno

wn

c

Loi

asis

Loa

loa

Equ

ator

ia r

egio

n;pr

edom

inan

tly W

EU

nkno

wn

d

Onc

hoce

rcia

sis

Onc

hoce

rca

volv

ulus

Hyp

eren

dem

ic in

WB

EG

,N

BE

G, W

arra

b, L

akes

, WE

,C

E a

nd p

arts

EE

; Par

ts o

fU

nity

bor

deri

ng W

arra

b; in

Jong

lei b

orde

r w

ithE

thio

pia;

UN

on

bord

erw

ith B

N

4.1

mill

ion

at r

isk,

of

whi

ch 3

.6 m

illio

nel

igib

le f

or tr

eatm

ent

40, c

Dra

cunc

ulia

sis

Dra

cunc

ulus

med

inen

sis

All

stat

es e

xcep

t WE

and

Uni

ty3,

618

case

s in

200

8,do

wn

from

5,8

15 c

ases

in 2

007

41, e

Schi

stos

omia

sis

Schi

stos

oma

haem

atob

ium

Prob

ably

War

rab,

Lak

es,

Uni

ty &

UN

Unk

now

nc,

f

S. m

anso

niE

E, C

E a

nd W

E, P

roba

bly

Jong

lei,

War

rab

and

Lak

esU

nkno

wn

a Abb

revi

atio

n of

Sta

tes:

BN

= B

lue

Nile

, CE

= C

entr

al E

quat

oria

, EE

= E

aste

rn E

quat

oria

, NB

EG

= N

orth

Bah

r el

Gha

zal,

UN

= U

pper

Nile

, WB

EG

= W

este

rn B

ahr

el G

haza

l, W

E =

Wes

tern

Equ

ator

ia

Trends Parasitol. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2009 August 19.

Europe PM

C Funders A

uthor Manuscripts

Europe PM

C Funders A

uthor Manuscripts

Rumunu et al. Page 12b H

uman

Afr

ican

Try

pano

som

iasi

s (s

leep

ing

sick

ness

): E

pide

mio

logi

cal u

pdat

e. h

ttp://

ww

w.w

ho.in

t/wer

/200

6/w

er81

08.p

df

c Neg

lect

ed T

ropi

cal D

isea

se in

Sou

ther

n Su

dan:

Situ

atio

n A

naly

sis,

Gap

Ana

lysi

s an

d In

terv

entio

n O

ptio

ns A

ppra

isal

. http

://w

ww

.mal

aria

cons

ortiu

m.o

rg/d

ata/

file

s/pa

ges/

ntds

_sou

ther

n_su

dan.

d APO

C (

2005

) R

apid

ass

essm

ent o

f lo

iasi

s an

d on

choc

erci

asis

in E

quat

oria

reg

ion

of S

outh

ern

Suda

n. M

issi

on R

epor

t, A

fric

an P

rogr

amm

e fo

r O

ncho

cerc

iasi

s C

ontr

ol, 4

– 2

4 A

pril

2005

.

e Sout

hern

Sud

an G

uine

a W

orm

Era

dica

tion

Prog

ram

, Min

istr

y of

Hea

lth, G

over

nmen

t of

Sout

hern

Sud

an, F

inal

Rep

ort,

2008

f Atla

s of

the

Glo

bal D

istr

ibut

ion

of S

chis

toso

mia

sis.

http

://w

ww

.who

.int/w

orm

cont

rol/d

ocum

ents

/map

s/en

/

Trends Parasitol. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2009 August 19.

Europe PM

C Funders A

uthor Manuscripts

Europe PM

C Funders A

uthor Manuscripts

Rumunu et al. Page 13

Table 2

Current NTD control strategies in Southern Sudanf

Disease Primary InterventionsCurrentlyUsed

Progress to date Limitation of CurrentIntervention

Suitablefor MDA?

Onchocerciasis Annual CDTI implementedsince1995

1.3 million individuals (36% ofeligible population) treated in 2007

Incomplete coverage; high attritionrate of CDDs

Yes

Dracunculiasis Active case surveillance,detectionand containment, andpreventionactivities including waterfiltration,provision of safe water,treatmentof water sources and healtheducation

In 2008, 89% of endemic villageswere providing regular reports,49% of cases were contained, andcases were reduced by 38% whencompared to 2007

Incomplete coverage ofsurveillance and interventions

No

Soil-transmittedhelminths

Single dose albendazole,distributed alongside NIDs

2.5 million doses distributed in allten states in 2006, reaching 87% ofthe targeted 1-5 year oldsSimilar coverage achieved in 2007

Lack of prevalence data andintervention strategy

Yes

Schistosomiasis No large scale campaigns forschistosomiasis control havebeenundertaken to date. Praziquantelisrarely available at healthfacilities

Small, ad-hoc treatment campaigns Insufficient prevalence data andlack of large-scale interventionstrategy

Yes

Lymphaticfilariasis

No targeted interventions todate

Regular distribution of ivermectinin CDTI areas will have reducedinfection levels in areas where LFand onchocerciasis are co-endemic

Lack of prevalence data; limitedfunds for surveys and to conductMDA; no palliative care; co-endemicity of L. loa in Equatoriaregion

Yes

Loiasis No targeted interventions todate.Pathology not considered worthtreatment at the present time.Important because co-infectionwith onchocerciasis can provokeSAEs

Regular distribution of ivermectinin CDTI areas will have reducedinfection levels in areas where Loaloa and onchocerciasis are co-endemic, but may have causedSAEs

Boundaries of loiasis endemic areanot clearly delineated. Notreatment suitable for MDA

No

Trachoma SAFE strategy consisting of:trichiasis surgery, antibiotics foractive trachoma, facialcleanlinessand environmentalimprovements

SAFE is being delivered as anintegrated component of theGuinea worm eradication programin parts of Eastern Equatoria andJonglei States

Limited coverage and varyinguptake of interventions bycommunities

Yes

Visceralleishmaniasis

Passive case detection at a fewhealth facilities equipped totreatthe disease; treatment withpentavalent antimonials

Case-management and supplychain of drug and diagnosticsupplies improved

Limited number of facilities withequipment and skills for diagnosisand treatment; cost of drugs;emerging drug resistance; lack ofawareness and prevention (LLINs)in affected communities

No

Human AfricanTrypanosomiasis

Passive case detection at a fewhealth facilities; treatment withpentamidine, eflornithine andmelarsoprol

Number of cases reported havedecreased as a result ofinterventions carried out since2003 [21]

Inadequate surveillance, limitednumber of treatment facilities andtrained health workers

No

Buruli Ulcer Antibiotic treatment using, forexample, rifampicin andaminoglycoside

Some interventions (treatment,awareness campaigns, healtheducation) have been carried outover the last years

Disease distribution not clearlyestablished, limited access totreatment and surgery

No

Leprosy MDT blisterpacks provided freeofcharge by WHO

Some interventions (treatment,awareness campaigns, healtheducation) have been carried out

Limited MDT coverage No

Trends Parasitol. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2009 August 19.

Europe PM

C Funders A

uthor Manuscripts

Europe PM

C Funders A

uthor Manuscripts

Rumunu et al. Page 14

Disease Primary InterventionsCurrentlyUsed

Progress to date Limitation of CurrentIntervention

Suitablefor MDA?

over the last years

fAbbreviations: CDD, community drug distributor; CDTI, community-directed treatment with ivermectin; LF, lymphatic filariasis; LLIN, long-

lasting insecticidal net; MDA, mass drug administration; MDT, multi-drug therapy; NID, national immunization day; SAE, severe adverse event;SAFE, strategy for trachoma control consisting of eyelid surgery (S), antibiotics to treat the community pool of infection (A), facial cleanliness (F),and environmental changes (E).

Trends Parasitol. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2009 August 19.