Settlement patterns (JFA 1983)

Transcript of Settlement patterns (JFA 1983)

Board of Trustees, Boston University

Settlements and the Development of "Statelets" in Sonora, MexicoAuthor(s): William E. DoolittleReviewed work(s):Source: Journal of Field Archaeology, Vol. 11, No. 1 (Spring, 1984), pp. 13-24Published by: Boston UniversityStable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/529337 .Accessed: 14/12/2011 17:12

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range ofcontent in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new formsof scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected].

Boston University and Board of Trustees, Boston University are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserveand extend access to Journal of Field Archaeology.

http://www.jstor.org

Introduction

With the exception of the Casas Grandes area, north- ern Mexico has been long perceived as a region occupied during pre-Hispanic times by "barbaric" peoples known collectively as the Chichimecs. ' This generalization, however, well may be a gross oversimplication resulting from the paucity of archaeological work conducted in the region to date. Indeed, a few scholars, such as Sauer and Kelley, have argued that parts of the area were in- habited by people who were both numerous and cultur- ally advanced.2 Most recently, Riley has suggested that pre-Hispanic occupants of one area, the Serrana of east- ern Sonora, attained a modified chiefdom form of social organization that he calls "statelets."3

1. Charles C. DiPeso, "Prehistory: Southern Periphery," in Alfonso Ortiz, ed., Handbook of North American Indians, Vol. 9, The South- west (Smithsonian Institution: Washington 1979) 152-161; Carroll L. Riley and Basil C. Hedrick, eds., Across the Chichimec Sea (Southern Illinois University Press: Carbondale 1978).

2. Carl Sauer, "Aboriginal Populations of Northwest Mexico," Ibe- ro-Americana 10 (University of California Press: Berkeley 1935), 1- 33; J. Charles Kelley, "Archaeology of the Northern Frontier: Za- catecas and Durango," in Robert Wauchope, ed., Handbook of Middle American Indians, Vol. 11, Archaeology of Northern Mesoamerica, Part2 (University of Texas Press: Austin 1971) 768-801.

3. Carroll L. Riley, "Las Casas and the Golden Cities," Ethnohistory (1976) 19-30; idem, "Casas Grandes and the Sonoran Statelets," Paper presented to the Chicago Anthropological Society, Field Mu-

Relying principally on documentary evidence, such as the reports of Castaneda and Jaramillo, chroniclers of Coronado's 1540 expedition, Riley argues that the large population of the Serrana was divided into several au- tonomous political provinces. According to Riley, the nature of their political organization is unknown, but the citizens of these provinces or statelets ''seem to have had a more complex political structure than that of the Pueblo Indians."4 Riley characterizes statelets as having had ranked, rather than egalitarian, societies with a ral- ing class.5 Slavery existed within the statelets, and war- fare between statelets was common; economic life was based on irrigation agriculture and heavily oriented to- ward trade.6 Most notably, statelets were delimited in part by the river valleys they occupied, and they each

seum (1979); idem, "Mesoamerica and the Hohokam: A View from the 16th Century,'' in David Doyel and Fred Plog, eds., Current Issues in Hohokam Prehistory: Proceedings of a Symposium, Arizona State University Anthropological Research Papers 23 (Tempe 1980) 41-48; idem, "The Frontier People: The Greater Southwest in the Protohistoric Period,'' Center for Archaeological Investigations, Oc- casional Paper 1 (Southern Illinois University: Carbondale 1982) 39. Riley carefully avoids using value-laden terms such as "level of de- velopment. ' '

4. Ibid. ( 1980) 42.

5. Riley, 1979 op. cit. (in note 3) 37.

6. Ibid. 40, 42.

Settlements and the Development of "Statelets" in Sonora, Mexico

William E. Doolittle The University of Texas at Austin Austin, Texas

The late prehistoric and protohistoric population of eastern Sonora, Mexico, has been described on the basis of reports by early Spanish explorers, as being organized into modified chiefdoms called "statelets." The development of these small, regionally discrete political units has been seen as the result of Casas Grandes influence. Archaeological data on late prehistoric settle- ment patterns gathered during an intensive survey of the Valley of Sonora and presented here verify that statelets did exist. Data on earlier settlements and settlement-pattern changes, however, are interpreted as meaning that statelets developed without external influence. A growing population and in- creasing local exchange are proffered as the underlying causes for statelet development. Contact and trade with neighboring groups did exist, but prob- ably were consequences rather than causes of changes evident in the settle- ment patterns.

14 Development of "Statelets'' in Sonora, Mexico/Doolittle

contained numerous small settlements and one large set- tlement that functioned as the social, economic, and po- litical center.7 Continuing a well established tradition, Riley considers the statelets to have developed quite late and as a result of migrations from Chihuahua.8 Most recently, he has suggested that this intrusion began ca. 1300 A.C. 9

Discussions and criticisms of, and other explanations for, the existence and the development of statelets have been few, pnncipally because so little archaeological work has been conducted in the area, but also because the idea of a highly developed culture in NW Mexico is not well accepted. For example, Kelley claims that "KNOWN archaeological remains simply do not approach the cul- tural levels described in the ethnohistorical documents by Riley."'° Many points concerning the statelets need to be addressed, and undoubtedly will be in the future, as the volume of work in the area increases. Foremost, however, especially in light of Kelley's comment, is the need for archaeological testing of Riley's suggestions concerning the existence of statelets and their develop- ment. This essay presents the results of such an inves- tigation.

The purpose of this paper is twofold: to provide the first archaeological evidence verifying the existence of the eastern Sonoran statelets; and to demonstrate that statelet development involved a population that was largely independent of people from Chihuahua, espe- cially from Casas Grandes. In the pages that follow after a description of the region and a discussion of previous research, the results of a recent archaeological survey are presented. The settlement data from that survey will then be evaluated in terms of the statelets and their de- velopment. Settlement data are used here because they provide the best available means by which the statelets, as described by Riley, can be archaeologically exam- ined. Other phenomena, such as social organization, are not only difficult to assess under optimal circumstances, but for the statelets no model suitable for comparative purposes has been offered. A settlement pattern, how- ever, is described in the ethnohistorical literature. Set- tlement data thus provide at least one measure by which ideas concerning the statelets can be assessed.

7. Riley, 1982 op. cit. (in note 3) 49, and 1976 op. cit. (in note 3).

8. Donald D. Brand, "Pottery Types in Northwest Mexico," AmAnth 37 (1935) 305; Charles C. DiPeso, Casas Grandes: A Fallen Trading Center of the Gran Chichimeca (Northland Press: Flagstaff 1974) Vol. 3, 799; and Riley, 1980 op. cit. (in note 3) 43.

9. Riley, 1982 op. cit. (in note 3) 39.

10. J. Charles Kelley, ''Discussion of Papers by Plog, Doyel, and Riley," in Doyel and Plog, eds., op. cit. (in note 3) 65.

The Serrana and Settlement Locales The eastern half of the state of Sonora lies in the ex-

treme southern end of the Basin and Range Physio- graphic Province of North America. Known as the Serrana, this region is composed of a series of five N-S trending parallel ranges that form a semiarid ecological transition zone between the coastal plain of the Gulf of California and the Sonoran Desert on the west, and the pine-covered Sierra Madre on the east (FIG. 1). The basins between these ranges are filled with thick alluvial de- posits that have been incised by rivers. These rivers also have formed flood plains that vary from 1 to 4 km in width. Numerous tributary arroyos have dissected the basin still further so as to form series of elongated mesas that extend from the ranges to the flood plains. Because of numerous geological differences, some locales are dissected much more extensively than others. As a re- sult, wide mesas characterize some places while in oth- ers, often only a short distance away, narrow mesas may be more common. Depending on the degree and extent of the dissection, mesas may be numerous or few, and

Figure 1. Sonora, Mexico, the Serrana, and the Valley of Sonora.

Journal of Field Archaeology/Vol. 11, 1984 15

mesas being chosen arbitrarily for investigation; most mesas were never visited.l3 Not suIprisingly, these sur- veys produced only fragmentaw and largely inaccurate information about the prehistory of the region. Although a connection with Casas Grandes was revealed through ceramic analyses, the paucity of data recovered during these endeavors was cited as evidence that the region was a near-lacuna inhabited by a sparse population that lived in small, scattered settlements, and achieved only a limited level of development.l4 Such intexpretations are, of course, inconsistent both with the descriptions of the early explorers and Riley's statelet interpretation.

Rather than attempting to reinvestigate the entire re- gion in a manner similar to that of the early surveyors, Richard Pailes and his research team decided to system- atically investigate every mesa-top locale in one of the five Serrana valleys. I5 The 5 l-km-long Valley of Sonora (FIG. 1) was chosen largely because it was identified by early Spanish explorers as having been inhabited by a large, village-dwelling, agriculturally advanced popula- tion. 16

During the summers of 1977 and 1978, as the surveyor for this large archaeological project funded by the Na- tional Science Foundation, I had the opportunity to ex- amine in detail every mesa in the Valley of Sonora.'7 Notes were talien, a systematic surface collection of cul- tural materials including ceramics and lithics was made, and a sketch map noting the location, size, and com- position of each structure was drawn of each site. Data collected during this survey form the basis for this paper. Numerous excavations by other members of the project provided essential information concerning the identifi- cation and dating of archaeological features.

Settlement Data

In addition to the usual ceramic and lithic debris, pre- historic settlements in the Serrana are easily identified

13. Donald D. Brand, personal communication.

14. E.g., Amsden, op. cit. (in note 12) 40.

15. Richard A. Pailes, "Economic Networks: Mesoamerica and the American Southwest," Research Proposal No. SOC 75-20410, sub- mitted to the National Science Foundation.

16. Carl Sauer, "The Road to Cibola," Ibero-Americana 3 (Univer- sity of California Press: Berkeley 1932) 1-58.

17. The fieldwork was funded by the National Science Foundation, Grant BNS 76-16818, Richard A. Pailes, Principal Investigator; and carried out under the auspices of the Instituto Nacional de Antropol- ogia e Historia, Centro Regional del Noroeste. Richard A. Pailes, B. L. Turner, II, Edward J. Malecki, Daniel T. Reff, Beatriz Braniff C., Carroll L. Riley, James A. Neely, John O'Hear, and Jack D. Elliott, Jr., provided assistance during various stages of the research and writ- ing that is deeply appreciated.

their heights at the flood plain may vary up to 30 m. On the average, however, they are about 20 m higher than the adjacent flood plains.

Overlooking the fertile flood plains and the down- steam ends of the arroyos, the edges of these mesa tops make ideal locations for agricultural villages. In addition to being accessible to the fields, these sites were easily defensible. The visibility provided by their height would have made surprise attacks impossible, and the steep sides would have made siege difficult. As was the case with the early Spanish settlements, both secular and ec- clesiastical, and is still the case with present-day towns, most of the permanently inhabited agricultural settle- ments of the pre-Hispanic occupants were located on these mesas.

Past and Present Surveys

The importance of these mesas as settlement locations has been recognized since Bandelier made the first sur- vey of the region over a century ago.ll The degree to which the mesas were used by aboriginal occupants, however, was underestimated by Bandelier and later sur- veyors, probably because of the nature of their investi- gations. Through the 1960s, archaeological research in the Serrarla consisted mainly of extensive regional sur- veys. Reconnaissance trips by Lumholtz, Amsden, Sauer and Brand, Ekholm, Lehmer, and Wasley were, like Bandelier's, oriented toward discovering large and pre- sumably important sites.l2 By design, these surveys tra- versed several kilometers each day, with relatively few

11. A. F. Bandelier, Final Report of Investigations Among the Indians of the Southwestern United States, Carried on Mainly in the Years from 1880 to 1885, Parts I and II, Papers of the Archaeological Institute of America, American Series III and IV (University Press: Cambridge 1890, 1892) Part I, 71-72; Part II, 486-487.

12. Carl Lumholtz, Unknown Mexico (Charles Scribner's Sons: New York 1902) 6-59; Monroe Amsden, "Archaeological Reconnaissance in Sonora," Southwest Museum Papers 1 (Southwest Museum: Los Angeles 1928); Carl Sauer and Donald Brand, "Prehistoric Settle- ments of Sonora, with Special Reference to Cerros de Trincheras," University of California Publications in Geography 5 (University of California Press: Berkeley 1931) 67-148; Gordon F Ekholm, ''Re- sults of an Archaeological Survey of Sonora and Northern Sinaloa," Revista Mexicana de Estudios Antropologios ( 1939) 7- 19; idem, ' 'The Archaeology of Northern and Western Mexico," in The Maya and Their Neighbors, Clarence L. Hay et al., eds., (D. Appleton-Century: New York 1940) 320-330; Donald J. Lehmer, ''Archaeological Sur- vey of Sonora, Mexico," Chicago Natural History Museum Bulletin (1949) 4-5; William W. Wasley, Field notes from an archaeological survey of eastern Sonora, Mexico in 1967, on file, Arizona State Museum, University of Arizona, Tucson. For a discussion of these surveys see R. A. Pailes, "Prehistoric Cultural Relationships in Northeastern Sonora," in Sonora: Antropologia del Desierto; Primera Reunion de Antropologia e Historia del Noroeste. Coleccion (Sientifica 27 (Centro Regional del Noroeste-INAH: Hermosillo 1976).

16 Development of "Statelets'' in Sonora, MexicolDoolittle

Figure 2. Typical surface evidence of a house-in-pit. The person in Figure 3. Rectangular rows of rocks are the typical surface the photograph is standing at the far edge of the human-made evidence of above-ground, single-story, adobe structures. The depression. person in the photograph is walking along the far side of the

feature.

by rectangular clusters of embedded rocks, mounds of adobe melt, and distinctively human-made surface depressions. These features have long been accepted as being remains of structures that once functioned as houses.l8 Until recently, however, intncacies of their forms, dates of their construction, and penods of their occupation remained unknown.

Excavations during the past decade have demonstrated that these features are the remains of two basic types of structures, houses-in-pits and surface structures.l9 An- cient houses-in-pits are identifiable by the shallow sur- face depressions (FIG. 2) that are sometimes nnged with rocks removed during digging at the time of construc- tion. Such houses were circular, D-shaped, or oval sem- isubterranean stuctures with either earthen or raised floors and mat, jacal, or wattle-and-daub superstructures. The sides of the pits in which such houses were built were not integral parts of the structure; hence these dwellings are actually and literally houses-in-pits rather than pit houses. Surface structures, like most of the houses oc- cupied in the region today, were rectangular, ca. 4 m wide and 5 m long. The number of rooms and the shapes of surface structures vary, but an average size of ca. 20 sq m was usually maintained. Typical ancient founda- tions, or cimientos, were 20-30 cm wide and were made of stones set vertically in adobe (FIG. 3).20 The walls of

18. Ales Hrdlicka, "Notes on the Indians of Sonora, Mexico," AmAnth 6 (1904) 59.

19. Richard A. Pailes, "The Rio Sonora Culture in Prehistoric Trade Systems,'' in Riley and Hedrick, eds., op. cit. (in note 1) 134-143; idem, "The Upper Rio Sonora Valley in Prehistoric Trade," Trans- actions, Illinois State Academy of Science 72.4 (1980) 20-39.

20. Robert J. Drake, "Sonora Building Foundations,'' El Palacio 61

such houses were adobe and the roofs were earth-covered mesquite (Prosopis sp.) timbers.2l

It has long been assumed that residents of the Serrana lived only in single-story surface structures because there was no known archaeological evidence of multistory houses. This assumption is especially cunous because the Spanish explorers in the mid-16th century noted "abandoned houses of two and three stones."22 No mul- tistory structures have been preserved for some time now in Sonora. Nevertheless, there is archaeological evi- dence, albeit tentative, for their existence.23 Most of the surface structures as described previously have founda- tions of single and double rows of rocks (FIG. 3). Adobe walls were constructed on top of these foundations in a manner somewhat similar to that used in the construction of present-day, single-story houses. Because of their rel- ative nairowness, these foundations could not have footed

(1954) 344-346. Similar construction techniques dating to roughly the same time period are found in other Southwestern locales. For example, see Carr Tuthill, The Tres Alamos Site on the San Pedro River, Southeastern Arizona (Amerind Foundation: Dragoon 1947) 18-19; Steven LeBlanc and Ben Nelson, ''The Salado in Southwest- ern New Mexico," Kiva 42 (1976) 76.

21. Robert E. Gasser, "The Rio Sonora Flotation Analysis," unpub- lished MS on file, Department of Anthropology, University of Okla- homa.

22. George P. Hammond and Agapito Rey, eds., trans., Obregon's History of 16th Century Explorations in Western America (Wetzel: Los Angeles 1928) 197.

23. William A. Howard and Thomas M. Griffiths, "Trinchera Dis- tribution in the Sierra Madre Occidental, Mexico," Publications in Geography, Technical Paper 66:1 (University of Denver 1966) 56.

Journal of Field ArchaeologylVol. 11, 1984 17

evldence of probable rnulPt t ows of rocks are the typical surface dark soil for dellneation purposes.

walls of sufficient thickness to support a second, much less a third story. There are, however, a number of foun- dations of multiple-room houses that have three, four, and even five rows of rocks (FIG. 4). Presumably these larger foundations supported the multistory structures observed by the Spanish.24 In addition, many of the sites of large foundations are characterized by an inordinate amount of melted adobe. Although conjectural, it seems logical that melted adobe would be more abundant at the sites of large structures.

The early surveyors noted that it was difficult to dis- tinguish between the foundations of prehistoric and his- toncal surface structures.25 Indeed, they are very similar. Differentiating cntena were therefore established in an attempt to insure that foundations of houses of the his- toncal penod were not included in this study. Surface structures with standing walls or portions of walls were found through excavations not to have been occupied in pre-hispanic times, and were, therefore, excluded from consideration. Similarly, house sites lacking associated prehistoric ceramics and lithics, but containing abundant artifacts of histoncal and recent times, were also ex- cluded.

24 An archaeological parallel supporting this conclusion is found in Emil W. Haury, 'SThe Excavation of Los Muertos and Neighboring Ruins in the Salt River Valley, Arizona," PapPeaMus 24 (1945) 17. An ethnohistorical parallel is found in Drake, op. cit. (in note 20). Interestingly, the prehistoric Sonoran foundations are wide enough to meet the present-day building codes for multistory adobe structures in several locales in the Southwestern U.S., e.g., H. T. Hinrichs, ''New Mexico State Adobe Code," Adobe Today 22 (1981) 4-9; Anony- mous, "Tucson's New Adobe Code," Adobe Today 22 (1981) 13; Anonymous, 4'The E1 Paso City Adobe Code," Adobe Today 23 (1981) 14.

25. Bandelier, 1892 op. cit. (in note 11) 498.

The number of structures evidenced by surficial re- mains, of course, is fewer than the number actually oc- cupied during pre-hispanic times. Subsequent constructions and erosion have contributed to the de- struction of some houses. Although these problems fre- quently restrict research endeavors, in this case they actually pose few difficulties. At worst, house counts can be considered as conservative estimates.

Occupational Sequence The paucity of work done prior to the initiation of this

project made the dating of sites a difficult task. Although a ceramic typology and sequence has yet to be estab- lished, a settlement chronology based on architectural differences was developed. From the excavation of 59 structures on 34 sites, including intensive excavations on one site (Son K:4:24 OU), a seriation of house types and an occupational sequence have been outlined for the Val- ley of Sonora.26

Evidence, including one component dated by radio- carbon to nearly 500 B.C*, and pit-and-groove petro- glyphs (FIG. 5) that have been dated in other areas at 5000-3000 B.C., indicate very early but poorly defined periods of occupation.27 The sequence becomes clearer with the development of permanent dwellings. Houses- in-pits were used exclusively between ca. 1000 A.C. and the end of the 1100s. The entire 13th century and ap- proximately half of the 14th century were transitional times in which the importance of houses-in-pits declined

26. Richard A. Pailes, 1980 op. cit. (in note 19).

27. Robert F. Heizer and Martin A. Baumhoff, Prehistoric Rock Art in Nevada and Eastern California (University of California Press: Berkeley 1962) 234.

18 Development of ''Statelets'' in Sonora, MexicolDoolittle

as adobe surface structures increased in number. Finally, single- and multistoried surface structures, and large- scale public architecture, including ball courts, domi- nated the settlement scene between the mid-1300s and the end of pre-Hispanic times. Houses-in-pits also con- tinued to be used throughout this terminal phase.

Even though there is a considerable amount of con- temporaneity between houses-in-pits and surface struc- tures, a senation of house types is identifiable. Two clear cases of superposition have been found in which surface structures overlie houses-in-pits. There are no known cases where surface structures were constructed dunng early times, or where houses-in-pits overlie surface structures. Houses-in-pits do not appear to have been constructed dunng late pre-Hispanic times, but many earlier ones were rebuilt and used continuously, even past the time of contact wii Europeans. Apparently those houses-in-pits that were used contemporaneously with surface structures were both built and occupied dunng the earlier times. Radiocarbon dates and the results of obsidian hydration analysis venfy this seriation.28 Sim- ilar architectural changes dating to this same half-mil- lennium have been archaeologically documented in other parts of the Southwest; indeed, this change may be a pan-Southwestern phenomenon.29

From these analyses, it is assumed that surface struc- tures were occupied only during late pre-Hispanic times. Houses-in-pits, except those overlain by surface struc- tures, were probably occupied throughout the sequence. In this study, all qualifying ancient houses are considered to date to a late pre-Hispanic phase (ca. 1350-1550 A.C.) while all ancient houses-in-pits are considered to date to either the late phase or an earlier phase (ca. 1000-1200 A.C.). Unfortunately, houses occupied during intervening times are not clearly distinguishable from those of the earlier or later phases at this time. Enough evidence does exist, however, to suggest that architectural and, hence, settlement changes between the two phases were regular and continuous, and not discrete and abrupt.

Dating sites by architectural differences and determin- ing their sizes dunng the respective phases by use of surface evidence are, of course, practices that call for a great deal of caution. Difficulties with contemporaneity,

28. William E. Doolittle, "Obsidian Hydration Dating in Eastern Sonora, Mexico," in Clement W. Meighan and Glenn S. Russell, eds. Obsidian Dates III (Institute of Archaeology, University of Cal- ifornia: Los Angeles 1981) 155-160.

29. E.g., David E. Doyel and Emil W. Haury, eds., "The 1976 Salado Conference," Kiva 42 (1976); Michael E. Whalen. "Cultural Ecological Aspects of the Pithouse-to-Pueblo Transition in a Portion of the Southwest," ArnAnth 46 (1981) 75-92; idem, "An Investiga- tion of Pithouse Village Structure in Western Texas," JFA 8 (1981) 303-311; Tuthill, op. cit. (in note 20), 17, 24-25.

superposition, and disturbance are frequently encoun- tered during archaeological investigations.30 These prob- lems, however, appear to be relatively minimal in eastern Sonora because of the shallowness of artifact deposition, the limited amount of denudation, the durability of ar- tifacts under consideration, especially house founda- tions, and the paucity of post-occupational activity on the sites.3l Of the 59 structures that were excavated, for

30. See, e.g., Thomas Carl Patterson, ''Contemporaneity and Cross- Dating in Archaeological Interpretation," AmAnt 28 (1963) 389-392; J. Eric S Thompson, "Estimates of Maya Population: Deranging Factors," AmAnt 36 (1971) 214-216; Donna C. Roper, "Lateral Dis- placement of Artifacts due to Plowing,'' AmAnt 41 (1976) 372-375 31. Cf. Paul Tolstoy and Susan K. Fish, "Surface and Subsurface Evidence for Community Size at Coapexco, Mexico,'' JFA 2 (1975) 97-104; A. Kirkby and M. J. Kirkby, "Geomorphic Processes and the Surface Survey of Archaeological Sites in Semi-Arid Areas," in A. Davidson and M. L. Schackley, eds., Geoarchaeology (Westview Press: Boulder 1976) 229-253; D. P. Gifford, "Ethnoarchaeological

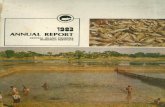

Figure 6. Spatial distribution of late-phase (ca. 1350-1550 A.C.)

settlements in the Valley of Sonora.

Journal of Field ArchaeologylVol. 11, 1984 19

example, two houses-in-pits were obscured by more re- cent surface structures.32 Given the areal limitation of the survey, therefore, it is assumed that most, if not all, visible ancient settlements were located and that evi- dence in the form of ceramics, lithics, and remnants of houses from each phase of occupation was found in rep- resentative amounts on the surface.33

Statelet Settlement Pattern

The most definitive statement that can be made about statelets, and the one most easily assessed, concerns their spatial distributions or patterns. According to Riley, each statelet was characterized by a settlement pattem in which there were numerous small settlements surrounding one large settlement that was the center of cultural activity. No mention has been made of intexlllediate-sized settle- ments, but lack of description does not preclude the exis- tence of such settlements.

The data provided by the surveys indicate that a set- tlement pattern not unlike that suggested by Riley did exist in eastern Sonora during late prehistoric times. Kel- ley's critique of the statelet evidence appears to be no longer appropriate.34 A total of 162 settlements and 1,289 houses were identified for the late phase of occupation (F1G. 6); 130 (80.2%) of the settlements were composed of eight or fewer houses. Because of their small size and scattered distribution, these settlements are classified as rancherias in the traditional Southwestern sense.35 Twenty of these sites contained only fragmentary evi- dence of late occupation, but were classified as ranch- erias because they were located on very small mesas that could not have contained many houses.

Two late-phase sites are classified as regional centers because they are very large and oriented around large- scale public architecture. One site (Son K:4:24 OU) has 60 identifiable foundations and fragmentary evidence of at least 100 others, while the other site (Son K:4:16 OU)

Observations of Natural Processes Affecting Cultural Materials," in R. A. Gould, ed., Explorations in Ethnoarchaeology (University of New Mexico Press: Albuquerque 1978) 77-101; P. J. Hughes and R. J. Lampert, "Occupational Disturbance and Types of Archaeological Deposit, " JAS 4 (1977) 135- 140.

32. Pailes, op. cit. (in note 26) 29, and personal communication.

33. Charles L. Redman and Patty Jo Watson, "Systematic, Intensive Surface Collection," AmAnt 35 (1970) 279-291; Kent V. Flannery, "Sampling by Intensive Surface Collection," in Kent V. Flannery, ed., The Early Mesoamerican Village (Academic Press: New York 1976) 51-62.

34. Kelley, op. cit. (in note 10).

35. Edward H. Spicer, Cycles of Conquest: The Impact of Spain, Mexico, and the United States on Indians of the Southwest, 1533- 1960 (University of Arizona Press: Tucson 1962) 12.

bears evidence of over 200 houses.36 Their size and the presence of public architecture suggest that these sites served some, perhaps several, centalized ifunctions. This suggestion is supported by their locational characteris- tics. Each of these sites is located near the physical cen- ter of a discrete physiographic segment of the valley.37 More importantly, these sites were located exactly at the node, or point of minimum aggregate distarlce to all oier settlements (F1G. 6).38

The nodal locations of the two regional centers among numerous other sites conform to the pattern described in the ethnohistorical documents and by Riley. Further- more, although there has been concern over the appli- cability of some locational models,39 such a pattern has been demonstrated both empirically and through simu- lation studies to be typical of situations where one site serves as a central place, or a settlement that provides goods and services to a surrounding market area.40 It appears, therefore, that the Valley of Sonora was divided into two provinces or statelets, one encompassing the northern half of the valley and the other, the southern half. Each valley segment contained numerous small set- tlements and one very large settlement that presumably was the center of social, political, and economic activity.

In addition to the rancherias and the regional centers, two other settlement categories not suggested in the doc- umentary data are distinguishable in the Valley of Son- ora. Both of these settlement types are based principally on size, or the number of structures, and secondly on internal organization. Hamlets, involving nine to 25 scat-

36. It is highly probable that these figures are conservative, and that more structures actually were in use, because severe erosion is evident on both sites.

37. The entire Rio Sonora Valley is broken into a number of distinc- tive physiographic segments. See, e.g., Sauer and Brand, op. cit. (in note 12) 102-103.

38. Calculation of the node in a one-dimensional region such as a river valley first involves drawing a line through the sites from one end of the region to the other. This line is then scaled and the nu- merical value of each site location is determined. Because the measure involves aggregates, a weighting factor for each site, here the number of houses, is multiplied to the locational value of the site. The mean (X) of all weighted site values is calculated and then mapped on the original scaled line. The location of the mean is the node.

39. Carole L. Crumley, "Three Locational Models: An Epistemo- logical Assessment for Anthropology and Archaeology," in Michael B. Schiffer, ed., Advances in Archaeological Method and Theory II (Academic Press: New York 1979) 141-173.

40. Andrew F. Burghardt, "The Location of River Towns in the Central Lowlands of the United States," AAAG 49 (1959) 305-323; Kent V. Flannery, "Linear Settlement Patterns and Riverside Settle- ment Rules," in Flannery, ed., op. cit. (in note 33) 173-180; Roger W. White, "Dynamic Central Place Theory: Results of the Simulation Approach," Geographical Analysis 9 ( 1977) 226-243.

20 Development of ''Statelets'' in Sonora, MexicolDoolittle

tered houses, account for 26 (16.0%) of the sites occu- pied during the late phase. Four (2.5%) sites containing 26 to 100 loosely arranged or partially laid out structures are classified as nucleated villages. These sites are not found throughout each of the valley segments, as might be expected. Instead, all four of the nucleated villages and more than two thirds of the hamlets are located in the northern segment of the valley. This condition is probably a function of environmental factors. In the northern segment mesa-top locales are few but large. For example, three of the nucleated villages are located on the only mesas that overlook the flood plain for consid- erable distances. These particular mesas are also very large. In the southern segment of the valley, on the other hand, especially along the east side of the river, mesa locales are numerous and moderate in areal extent. Per- haps not surprisingly, harnlets are found uniforrnly spaced throughout this area.

In general, it appears that the late-phase settlement pattern confirms the existence of statelets. Although the site hierarchy is more complex than that recorded in the ethnohistorical documents and described by Riley, a pat- tern in which one site was considerably larger and more centrally and nodally located than the others did exist in late pre-hispanic times. Anomalies in the settlement hi- erarchy seem to reflect environmental rather than cultural factors. Such an interpretation is not inconsistent with descriptions provided by the Spanish chroniclers. These early reporters were more interested in identifying sites of cultural significance than they were in assessing set- tlement patterns. In all likelihood they ignored many larger-than-average sites that were not distinctively cen- ters of regional activity.

Pre-Statelet Settlement Pattern

The paucity of data found by the early surveyors was used to show that few people lived in eastern Sonora and as evidence that occupation was limited to very late pre- historic times. The proposition that people other than small bands of cave dwellers lived in eastern Sonora earlier than the 14th century has been given little atten- tion. Evidence from the early-phase settlements suggests that occupation was earlier than previously thought.

A total of 65 settlements involving 224 houses were identified for the early phase of occupation. Sixty-two (95.5%) of the settlements were rancherias, and of these 25 (40.0So of all early-phase sites) were isolated resi- dences. Rancherias are found scattered throughout both the northern and southern portions of the valley (FIG. 7). The three other settlements are similar to the rancherias in that houses are haphazardly clustered on the sites, but they are distinctive in size. Two (3.0%) settlements with 10 and 12 houses, respectively, are classified as hamlets,

Figure 7. Spatial distribution of early-phase (ca. 1000-1 150 A.C.)

settlements in the Valley of Sonora.

while the largest settlement (Son K:4:24 OU), with 60 identifiable houses-in-pits, is classified as a nucleated village during this phase.41 Of the two hamlets one (Son K:4:32 OU) is located where two arroyos coalesce 3.0 km from the flood plain, and the other (Son K:4:110 OU) is located near the node in the northern segment of the valley. The one nucleated village, perhaps not un- expectedly, is located at the node of the southern valley segment.

Most of the people who resided in the Valley of Son- ora during the early phase lived in the southern segment of the valley. Although less than half (28) of the early- phase settlements were found in this area, nearly two- thirds (62.1%) of all early-phase houses were located there. All the settlements at this time were probably ag-

41. A large number of surface structures dating to the late phase and extensive erosion suggest that many more houses than are evident on the surface were probably occupied during the early phase.

Valley Segment Time Period WestBank EastBank Total

North Early Phase 20 (34.5) 10 (17.3) 30 (51.8) Late Phase 35 (24.7) 31 (22.5) 66 (46.5)

South Early Phase 14 (24.1) 14 (24.1) 28 (48.2) Late Phase 31 (21.8) 45 (31.7) 76 (53.5)

Total Valley Early Phase 34 (58.6) 24 (41.4) 58 (100) Late Phase 66 (45.8) 76 (54.2) 142 (100)

Note. Numbers in parentheses indicate percentages.

Journal of Field ArchaeologylVol. 11, 1984 21

Table 1. Spatial distribution of river-oriented settlements.

ricultural communities. Evidence in the form of numer- ous channel-bottom weir terraces indicates that floodwater farming, runoff farming, water harvesting, and probably dry farming were being practiced in several large arroyos while incipient irrigation was being practiced in the well watered southern segment of the flood plain.42 It is doubtful that any agricultural goods produced at this time were traded outside the valley; the early-phase popula- tion was too small to have invested much effort in pro- ducing both for subsistence and for export. Furthermore, environmental vagaries characteristic of the arid South- west,43 and the marginality of some of the cultivated lands probably resulted in low average yields that varied greatly from field to field annually. Although there is no evidence of large-scale interregional trade at this time, there is tentative evidence of local exchange. The sizes and the nodal locations of the nucleated village and one hamlet imply that some intravalley interaction was cen- tered at these sites. It is highly possible that this inter- action involved the redistribution of food produced in a variety of locations with different techniques to insure adequate harvests under precarious conditions. The set- tlement pattern is, therefore, interpreted as reflecting a largely subsistence economy with perhaps some local exchange. There is no additional evidence, such as pub- lic architecture, of statelets at this time.

Settlement Changes and Statelet Development

The settlement patterns of the early and late phases (FIGS. 6, 7) are sufficiently different to indicate that the Valley of Sonora experienced significant cultural changes. The settlement data demonstrate that the small, scattered population increased and became organized into state- lets. Between the early and late phases the number of settlements increased ca. 150% and the number of houses

42. William E. Doolittle, ''Aboriginal Agricultural Development in the Valley of Sonora, Mexico," GeogRev 70 (1980) 328-342.

43. Jeffrey S. Dean and William J. Robinson, Dendroclimatic Var- iability in the American Southwest, A.D. 680 to 1970, Laboratory of Tree-Ring Research, (University of Arizona Press: Tucson 1977).

increased nearly 450%. Most of this change involved rancherias, and to a lesser extent hamlets, especially in the northern segment of the valley. Eighty-two of the late-phase rancherias (50.6go of all late-phase settle- ments) did not exist during the early phase. This increase resulted in the establishment of settlements in places where few settlements existed previously.44 Although early-phase settlements were by no means disproportion- ately clustered, the increase in settlements tended to equalize the spatial distribution throughout the valley (TABLE 1 ) . By the late phase nearly two-thirds (64 .5 %) of the valley residents lived in the northern segment. Expansion into this area was facilitated by the availabil- ity of irrigable land, nearly twice as much as in the south, and an increased dependency on intensive irrigation ag- riculture.45 The noted increase in the number of settle- ments was, therefore, a probable and logical response to a growing population that required the expansion of ag- riculture into previously little-used lands.46

The increase in settlement sizes, as evidenced by the number of distinctive architectural units (houses and rooms) is at least partially a result of the limited number of mesa locales suitable for occupation by an expanding population. Indeed, with a growing population settle- ments would have had to become larger if they could not become more numerous.

Although increases are noted for every category in the settlement hierarchy (TABLE 2), the growth characteristics of certain categories are especially important in terrns of statelet development. The increase of 68 rancherias was the largest numerical growth of any settlement category. Hamlets also increased in number and percent. Many early-phase rancherias grew sufficiently in size to be

44. Robert G. D. Reynolds, "Linear Settlement Systems on the Up- per Grijalva River: The Application of a Markovian Model," in Flan- nery, ed., op. cit. (in note 33) 180-194.

45. Doolittle, op. cit. (in note 42) 341.

46. Similar cases have been reported elsewhere in the world; see, e.g., Karl W. Butzer, Early Hydraulic Civilization in Egypt: A Study in Cultural Ecology (The University of Chicago Press: Chicago 1976).

Nucleated Regional Rancherfas Hamlets Villages Centers Total

Early Phase Houses 142 (63.4) 22 (9.8) 60 (26.8) 224 (100) Settle- ments 62 (95.5) 2 (3.0) 1 (1.5) 65 (100)

Late Phase Houses 412 (32.0) 318 (24.5) 199 (15.5) 360 (28.0) 1,289 (100) Settle- ments 130 (80.2) 26 (16.0) 4 (2.5) 2 (1.2) 162 (100)

Note. Parentheses indicate percentages.

22 Development of ''Statelets'' in Sonora, MexicolDoolittle

Table 2. Hierarchical distribution of settlements.

classified as hamlets by the late phase, thereby account- ing for the percentage decrease in these settlements, es- pecially isolated house sites. Rancherias, hamlets, and nucleated villages, which also increased in both size and number, were all probably agricultural communities; they contain no public architecture that could be considered as evidence that their sites served some other purpose. Accordingly, the increase noted in settlement sizes was probably a result of a rising population and intensifica- tion of agriculture on land already being cultivated, just as the increase in settlement numbers was a function of population growth and agricultural expansion.

The emergence of a fourth settlement category, re- gional centers, reflects what was perhaps the most sig- nificant settlement change in terms of statelet development. These settlements alone account for 50% more houses than existed in the entire valley during the early phase. Such a quantitative change, when consid- ered with the qualitative addition of public architecture, and their nodal locations indicates that these sites were undoubtedly the centers of extensive intravalley inter- action.

Discussion Exactly where the people who occupied eastern Son-

ora in prehistoric times came from, when they arrived, and the causes of their immigration and later develop- ment into statelets remain unclear. The limited amount of research conducted in the area to date has proven little. Indeed, the bulk of that research, that which saw habitation as both late and brief, has been debunked by the settlement data presented here. Two possible scen- arios do, however, emerge from the remaining body of research.

One scenario is derived from excavations carried out along the Sonora-Chihuahua border during the early 1950s. Lister found evidence that people moved into Mexico and began inhabiting caves in the Sierra Madres

as northern cultures were expanding southward in Mo- gollon III times, before 900 A.C.47 By 1100 A.C., how- ever, these caves were abandoned. Lister suggests their occupants may have moved eastward, contributing to the rise of Casas Grandes.48 This idea is certainly provoca- tive, but it has yet to be substantiated. It is equally as likely that the population growth that led to these peo- ple's migration into the area continued and forced them to move westward and begin living along large arroyos and flood plains in major river valleys. Such a scenario is consistent with settlement evidence of statelet devel- opment just discussed.

The second scenario was proffered on the basis of recently collected ceramic data. Pailes envisions the statelet development as the result of Casas Grandes ex- pansion ca. 1000 A.C.49 According to him, this intrusion was intended to control trade routes between Mesoam- erica and the Southwest.5° Like Lister's, Pailes's sce- naIio is little more ian speculation. lNhe ceramic evidence he presents is entirely too sketchy to draw any firrn con- clusions at this time. Furtherrnore, the population growth indicated by the increase in the number of houses from 224 in the early phase to 1,289 in the late phase need not have involved migration. Elsewhere I have demon- strated that such an increase would have been possible at an annual rate of about 0.5%,51 or approximately the

47. Robert H. Lister, Archaeological Excavations in the Northern Sierra Madre Occidental, Chihuahua and Sonora, Mexico. University of Colorado Studies Series in Anthropology 7 (Boulder 1958).

48. Ibid. 112-115.

49. Pailes, 1980 op. cit. (in note 19) 35.

50. Ibid.

51. William E. Doolittle, 44La Poblacion Serrana de Sonora en Tiem- pos Prehispanicos: La Evidencia de los Asentamientos Antiguous," in Memoria IV Simpsio de Historia de Sonora, Juan Antonio Ruibal Corella, coor. (Instituto de Investigaciones Historicas: Hermosillo 1979) 1-16.

Journal of Field ArchaeologylVol. 11, 1984 23

than external trade.S6 In situations where internal ex- change has always been more important than foreign trade, nodes move and settlements can have their relative status altered significantly. Large settlements can lan- guish while formerly insignificant settlements can be- come large centers of interaction.S7 Such change appears to have taken place in prehistoric times in the Valley of Sonora. Presumably the statelets evolved out of a local redistribution network as the population increased and a variety of lands of different quality were used for agri- culture. Given the changes in the location of the northern segment node, I suggest that some degree of free eco- nomic exchange might have been occurring within the valley at a place convenient to the aggregate population. The node moved as the size, density, and spatial distri- bution of the population changed. Regional centers emerged only when the society was stratified to the point that permanent capital improvements, such as public ar- chitecture, were added to the nodal site or settlement where intravalley exchange was taking place at the time.

Although goods from other areas are known to have been traded in and passed through the Valley of Son- ora,S8 the large settlements and ffie statelets did not emerge because of long-distance trade. The growth of what were to become regional centers preceded any significant large- scale trade. Large settlements were not developed after, or as a function of, existing trading activities. Instead, growing sites became increasingly more atwactive to long- distance traders. This finding is in general agreement with both Riley's and Kelley's ideas concerning the es- tablishment of Mesoamerican-Souffiwestenl wade. A route between these areas probably did not open in Sonora until late in pre-Spanish times. As Kelley states, "in all probability, this new trail was made possible and prof- itable by the development of the Sonoran statelets.''S9 The statelets appear, on the basis of settlement evidence, to have developed as a result of internal or indigenous eventsS independent of other cultures. A population that

56. James E. Vance, Jr., The Merchant's World: The Geography of Wholesaling (Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs 1970) provides an ex- cellent theoretical discussion of models of trade-oriented settlement patterns.

57. For a thorough critique of ideas on changes in settlement hier- archies see Nancy Ettlinger, ''Dependency and Urban Growth: A Crit- ical Review and Reformulation of the Concepts of Primary and Rank- Size," Environment and Planning 13A (1981) 1389-1400.

58. For a discussion of trade through Sonora and surrounding areas, see Carroll L. Riley, ''Sixteenth Century Trade in the Greater South- west," Research Records of the University Museum, Mesoamerican Studies 10 (Southern Illinois University: Carbondale 1976) 1-54.

59. Riley, op. cit. (in note 3); and Kelley, op. cit. (in note 10) 65.

same rate of growth found in the Basin of Mexico during the Terminal Formative Period.s2

The apparently sudden development of an inordinately large settlement has been noted as being one character- istic of settlement patterns that owe their existence to long-distance, interregional trade.S3 Although there are a few settlements in the Valley of Sonora that have such attributes, it is unlikely these sites were established as trading centers. By his own admission, Pailes sees the early-phase nucleated village as functioning as a local redistribution center.S4 Such a conclusion is, of course, borne out by the site's nodal location.

Further evidence for the emergence of the large set- tlements as centers of intravalley interaction rather than as trading centers is found in their absolute and relative locations, and changes therein. Settlements established as trading centers, presumably in response to an impetus provided by a dominant trading partner (such as in a colonial situation not unlike that proposed by Pailes) are not usually found near the physical center of their re- gions. They are usually located near the periphery of the region on the side closest to the trading partner, and they are rarely nodes of internal interaction.Ss

None of the largest sites of the early phase conforms to these conditions in the Valley of Sonora. Not only are the large sites near the physical centers of their respective valley segments, but they are also located at the nodes. Furthermore, as the population grew and sites increased both in size and number, the node in the northern half of the valley shifted upstream 6.0 km (FIGS. 6, 7). By the late phase, a site previously classified as a rancheria had grown into a regional center. This change could only have resulted as a function of intravalley activities, prob- ably increased local exchange. Settlements established as long-distance trading centers usually remain dominant even after internal interaction becomes more important

52. William T. Sanders, "Population, Agricultural History, and So- cietal Evolution in Mesoamerica," in Brian Spooner, ed., Population Growth: Anthropological Implications (MIT Press: Cambridge 1972) 101-135; Jeffrey R. Parsons, Elizabeth Brunfiel, Mary H. Parsons, and David J. Wilson, ''Prehispanic Settlement Patterns in the South- ern Valley of Mexico: The Chalco-Xochimilco Region," MMich- MusAnth 14 (University of Michigan: Ann Arbor 1982) 266.

53. Cesar A. Vapnarsky, ''On Rank-Size Distributions of Cities: An Ecological Approach," Economic Development and Culture Change 17 (1968) 584-595.

54. Pailes, 1980 op. cit. (in note 19) 36.

55. Andrew F. Burghardt, ''A Hypothesis About Gateway Cities," AAAG 61 (1971) 269-285; Kenneth G. Hirth, ''Interregional Trade and the Formation of Prehistoric Gateway Communities," AmAnt 43 (1978) 35-45.

24 Development of ''Statelets" in Sonora, MexicolDoolittle

was increasing without immigration appears to have be- come increasingly dependent on local redistribution probably to insure against spatial variations in crop yields.

William E. Doolittle received his Ph.D. in geography from the University of Oklahoma. His special interests include cultural ecology, agricultural development theory, and prehistoric settlement analysis. An Assistant Professor of Geography at the University of Texas at Austin, he has conducted field work in the American Southwest and in NW Mexico.