RECEIVED by MSC 6/2/2022 1:48:54 PM - Michigan Courts

-

Upload

khangminh22 -

Category

Documents

-

view

2 -

download

0

Transcript of RECEIVED by MSC 6/2/2022 1:48:54 PM - Michigan Courts

STATE OF MICHIGAN IN THE SUPREME COURT

MICHAEL JAY MARKEY, JR.,gubernatorial candidate, and THEMICHAEL MARKEY GOVERNORRACE CANDIDATE COMMITTEE (ID:520350), Plaintiffs-Appellants, v MICHIGAN SECRETARY OF STATE,THE BUREAU OF ELECTIONS, andTHE BOARD OF STATE CANVASSERS, Defendants-Appellees.

Supreme Court No: _____________

Court of Appeals No: 361580 Motion For Immediate Consideration:

Respectfully request decision by June 3, 2022

Thaddeus E. Morgan (P47394) Garett Koger (P82115) Paul V. McCord (P61138) Elizabeth Siefker (P83791) Fraser Trebilcock Davis & Dunlap, P.C. 124 W. Allegan, Suite 1000 Lansing, Michigan 48933 Telephone: (517) 482-5800 Fax: (517) 482-0887 Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellants

Heather S. Meingast (P55439) Erik A. Grill (P64713) Assistant Attorneys General Michigan Dep't of Attorney General 525 W Ottawa Street Lansing, MI 48933 (517) 355-7659 [email protected] [email protected] Attorneys for Defendants-Appellees

PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS’ APPLICATION FOR LEAVE TO APPEAL THE

MICHIGAN COURT OF APPEALS’ DENIAL OF THEIR VERIFIED COMPLAINT FOR AN ORDER OF MANDAMUS, DECLARATORY RELIEF,

& INJUNCTIVE RELIEF

THE APPEAL INVOLVES A RULING THAT A PROVISION OF THE CONSTITUTION, A STATUTE, RULE OR REGULATION, OR OTHER

STATE GOVERNMENTAL ACTION IS INVALID

REC

EIVED

by MSC

6/2/2022 1:48:54 PM

i

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

TABLE OF CONTENTS ................................................................................................. i

INDEX OF AUTHORITIES .......................................................................................... ii

STATEMENT OF JURISDICTION ............................................................................. iv

STATEMENT OF QUESTION PRESENTED ............................................................. v

INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 1

STATEMENT OF FACTS AND PROCEDURAL HISTORY ....................................... 2

A. Factual Summary ..................................................................................... 2

B. Procedural Summary ............................................................................. 15

ARGUMENT ................................................................................................................ 16

I. Markey is Entitled to Mandamus and Reversal of the Court of Appeals is Therefore Warranted ............................................................ 17

A. Standard of Review ...................................................................... 18

B. Markey Satisfies the Elements for Mandamus .......................... 18

CONCLUSION & RELIEF REQUESTED ................................................................. 33

REC

EIVED

by MSC

6/2/2022 1:48:54 PM

ii

INDEX OF AUTHORITIES

Page

Cases

Arrowhead Dev. Co. v Livingston Co. Rd. Comm., 413 Mich. 505 (1982) .................. 20

Attorney General v. Board of State Canvassers, 318 Mich App 273 (2008) ....... passim

Barrow v Wayne County Board of Canvasser, ____ Mich App ____, ____ (2022) ........................................................................................................................ 25

Berry v Garrett, 316 Mich App 37 (2016) .................................................................... 18

Citizens Protecting Michigan’s Constitution v Secretary of State, 503 Mich 42 (2018) ........................................................................................................................ 18

Committee to Ban Fracking in Michigan v Bd of State Canvassers, 335 Mich App 384 (2021) ......................................................................................................... 32

Deleeuw v State Bd. of Canvassers, 263 Mich App 497, 504 (2004) ........................... 20

Denton v Dep't of Treasury, 317 Mich App 303 (2016) ............................................... 18

Dep’t of Talent & Economic Development/Unemployment Ins. Agency v Great Oaks Country Club, Inc., 507 Mich 212 (2021) ....................................................... 20

Hillsdale Co. Senior Servs., Inc. v. Hillsdale Co., 494 Mich. 46 (2013) ..................... 29

Jaffe v. Oakland Co. Clerk, 87 Mich. App. 281 (1978) ............................................... 27

Johnson v Bd of State Canvassers, ____ Mich App ____ (2022) (Docket No.361564) .............................................................................................. 16, 30, 31, 32

Martin v Secretary of State Canvassers, 280 Mich App 417 (2008) ........................... 21

Rental Props Owners Ass’n of Kent Co v. Kent Co. Treasurer, 308 Mich App 498 (2014) ................................................................................................................. 18

State Bd of Ed v Houghton Lake Community Sch, 430 Mich 658 (1988) .................. 32

Stumbo v Roe, 332 Mich App 479 (2020) .................................................................... 20

Sweatt v Dep’t of Corrections, 468 Mich 172 (2003) ............................................. 20, 22

TCF Nat’l Bank v. Dep’t of Treasury, 330 Mich App 596 (2019) ................................ 18

REC

EIVED

by MSC

6/2/2022 1:48:54 PM

iii

US ex rel Knauff v Shaughnessy, 338 US 537 (1950) ................................................... 5

Wilcoxon v. City of Detroit Election Com’n, 301 Mich. App. 619 (2013) .................... 27

Statutes

MCL § 168.53 ................................................................................................................. 2

MCL § 168.544c(11)(a) ............................................................................... 21, 22, 27, 32

MCL § 168.544c(11)(b) ..................................................................................... 21, 22, 32

MCL § 168.544f .............................................................................................................. 2

MCL § 168.552 ............................................................................................................. 22

MCL § 168.552(13) ............................................................................................... passim

MCL § 168.552(8) ................................................................................................. passim

Rules

MCR 7.216(A)(7) .......................................................................................................... 19

MCR 7.303(B)(1) ........................................................................................................... iv

MCR 7.305 ..................................................................................................................... iv

MCR 7.305(B)(2) .......................................................................................................... 16

MCR 7.305(B)(3) .......................................................................................................... 16

MCR 7.305(C)(2)(a) ....................................................................................................... iv

MCR 7.316(A)(7) .......................................................................................................... 19

REC

EIVED

by MSC

6/2/2022 1:48:54 PM

iv

STATEMENT OF JURISDICTION

The Michigan Court of Appeals entered its final order denying Plaintiffs-

Appellants’ complaint seeking an order for mandamus against the Michigan

Department of State, the Bureau of Elections, and the State Board of Canvassers on

June 1, 2022. (See Ex. G, 6/1/22 MCOA Ord.) Plaintiffs-Appellants now seek leave

to appeal in this Honorable Court, pursuant to MCR 7.303(B)(1) and MCR 7.305.

Such is timely as the Court of Appeals’ order took immediate effect, and this

application is within forty-two days of that order. See MCR 7.305(C)(2)(a); (Ex. G,

6/1/22 MCOA Ord.).

REC

EIVED

by MSC

6/2/2022 1:48:54 PM

v

STATEMENT OF QUESTION PRESENTED

I. Does the Secretary of State, through the Bureau of Elections, wield plenary authority to unilaterally determine who is on the ballot in any given election notwithstanding statutory parameters?

Plaintiffs-Appellants’ answer: No.

Defendants-Appellees’ answer: Yes.

Court of Appeals’ answer: Yes.

REC

EIVED

by MSC

6/2/2022 1:48:54 PM

Page 1 of 39

INTRODUCTION

Central to Michigan’s democratic process is the notion that voters, not

bureaucrats, decide the outcome of our elections. As such, Michigan law presumes

that a candidate who has satisfied the basic statutory requirements is to be offered

to voters. If the government wants to deprive voters of that choice it must

demonstrate knowing fraud. This statutory presumption then affords Michigan’s

electorate the opportunity to decide whom it deems worthy of November’s general-

election contest. Only in cases where a candidate knowingly engaged in fraud may

s/he be removed from the ballot.

In this case, Gubernatorial Candidate Michael Markey did no such thing.

Rather, Markey submitted the statutorily required documentation for his candidacy,

which included well over the requisite number of nominating-petition signatures.

Markey’s candidacy then received no challenge. Nevertheless, the Bureau of

Elections received complaints on other candidates for allegedly forged signatures on

their nominating petitions. The Bureau of Elections ignored the Legislature’s

statutory requirements to address suspected fraud and created its own never-before-

seen process. This novel approach, which is a product of bureaucratic creativity

rather than law, resulted in roughly eighty percent of Markey’s nominating-petition

signatures being removed without actually having been viewed, which disqualified

Markey from the ballot. Markey learned of this via Twitter rather than from those

responsible. The Bureau of Elections’ extra-statutory process now tees up a novel

REC

EIVED

by MSC

6/2/2022 1:48:54 PM

Page 2 of 39

question for this Court: What limits has the Bureau of Elections to restrict the

electorate’s choices of candidates in a primary election?

STATEMENT OF FACTS AND PROCEDURAL HISTORY

A. Factual Summary

On March 18, 2022, Markey filed the nominating petition to run for the office

of Governor of Michigan, and therefore placement on the August 2, 2022 primary

ballot. To be included on the official primary ballot, a gubernatorial candidate for

nomination must submit nominating petitions with at least 15,000 signatures. See

MCL § 168.53; MCL § 168.544f.1 Markey’s nominating petitions contained 21,804

signatures—6,804, more than required. In conjunction with filing his nominating

petitions, Markey signed a sworn affidavit stating that those signatures were valid

and genuine to the best of his information, knowledge, and belief.

On May 23, 2022, the Bureau of Elections (“the Bureau”) published its Staff

Report on Fraudulent Nominating Petitions (“staff report”) and its Review of

Nominating Petition; Michael Jay Markey, Jr. Republican Candidate for Governor

(“review”) online. (See generally, Ex. A Stf. Rep; Ex. B, Markey Rev.) The staff report

identified alleged widespread petition fraud affecting the nominating petitions of an

unprecedented number of candidates for public office. (See Ex. A, Stf. Rep.) With

respect to Markey, the Bureau alleged that of the 21,804 signatures filed by Markey,

1 A gubernatorial candidate must also have petitions that are “signed by at least 100 registered resident electors in each of at least ½ of the congressional districts of the state.” It is undisputed that Markey satisfies this criteria.

REC

EIVED

by MSC

6/2/2022 1:48:54 PM

Page 3 of 39

79.68% or 17,374 were invalid due to suspected fraud. (See Ex. B, Markey Rev., p 1.)

This is the first time Markey and his team learned of a problem with his nominating

petitions, or that Markey was being publicly accused of a relationship to “fraudulent”

activity by the Bureau. In fact, Markey learned of this through the social media app,

Twitter.

The staff report claims that during its review of the nominating petitions for

the August 2, 2022 primary, the Bureau “identified 36 petition circulators who

submitted fraudulent petition sheets consisting entirely of invalid signatures.” (Ex

A Stf. Rep, p 1.) According to the Bureau, “All petition sheets submitted by these

circulators displayed suspicious patterns indicative of fraud, and staff reviewing

these signatures against the Qualified Voter File (QVF) did not identify any

signatures that appeared to be submitted by a registered voter.” (See Id.)

The Bureau claims that because of the large number of candidates trying to

qualify for the August 2, 2022 primary ballot, “Bureau staff began to review

nominating petitions at the end of March, after several gubernatorial candidates had

submitted nominating petitions.” (Id. at 2.) “During this review, staff noticed that a

large number of petition sheets, submitted by certain circulators, appeared

fraudulent and consisted entirely of invalid signatures.” (Id.) Citing the volume of

allegedly fraudulent signatures as justification, the Bureau directed its staff who

reviewed nominating petitions to implement an ad-hoc procedure by which they

reportedly observed patterns of fraud among certain petition circulators. Staff were

to then flag all nominating petition sheets submitted by these circulators and

REC

EIVED

by MSC

6/2/2022 1:48:54 PM

Page 4 of 39

presume all signatures on all flagged sheets to be fraudulent, in direct contradiction

to Michigan law. (See Ex. A, Stf. Rep., pp 3-5.)

According to the report, these petition sheets “tended to display at least one of

the following patterns: (1) an “unusually large number of petition sheets where every

signature line was completed, or where every line was completed but one or two line

were crossed out”; (2) sheets with “signs of apparent attempts at ‘intentional’

signature invalidity”; (3) an “unusually large number of petition sheets that showed

no evidence of normal wear that accompanies circulation”; (4) sheets that “appeared

to be ‘round tabled’ ”; (5) sheets on which “blank and completed lines were randomly

interspersed,” which apparently indicates “that a sheet had been submitted ‘mid-

round-table’ ”; (6) sheets “where all ten lines had signatures and partial addresses or

dates, but only a random subset were fully completed”; (7) sheets on which every

instance of the handwriting of certain letters was identical across lines, including

signatures; and (8) sheets “where the two or three distinct handwriting styles

appeared on multiple sheets.” (Id. at 2.)

The report claims that these observations led the Bureau staff to begin

comparing signatures to the QVF, which it claims revealed more issues, including:

(1) discrepancies between the petition signatures and the QVF signatures; (2)

signatures corresponding to addresses where the voter was previously registered; (3)

signatures corresponding to formerly registered voters whose registrations were

cancelled due to death; (4) signatures where the name on the petition was spelled

differently than in the QVF, or “where the petition used the voter’s middle name or a

REC

EIVED

by MSC

6/2/2022 1:48:54 PM

Page 5 of 39

diminutive or nickname”; and (5) signatures that listed the mailing address

jurisdiction rather than the actual jurisdiction. (Id. at 3.) The Bureau’s report claims

these issues led Bureau staff, individuals who remain unnamed, to identify

“numerous circulators” who they subjectively believed to be forging signatures while

“utilizing an outdated mailing list obtained from some source.” (Id.)

The Bureau opined its standard, long-standing approach to nominating

petitions has two stages. First, staff ‘face reviews’ every petition sheet and signature

for facial compliance with Michigan’s election law, which entails checking the heading

and circulator certificate; ensuring that the signature is accompanied by address,

date, and name; and checking that the listed city or township is in the county listed

on the heading. (Id. at 3-4.) After this stage, if the candidate has enough facially

valid signatures to qualify for the ballot, the Bureau notes the difference (or

“cushion”) and then “reviews any challenges to the petition’s sufficiency.”2 (Id. at 4)

(emphasis added.) If the cushion exceeds the number of challenges, the Bureau does

not process the challenge. If not, the Bureau processes the challenge to determine

2 For the first time and unknown to Markey since he filed his nominating petitions on March 18, 2022, Defendants-Appellees disclosed in their Answer and Brief in Response filed on June 1, 2022 that a complaint had been lodged against Markey's petitions. However, because the Bureau had apparently already determined that Markey was below the qualifying threshold, "staff did not process the challenge made to Plaintiff's signatures . . . " Defendants-Appellees’ Answer and Brief in Response, at p 11. This is troublesome as, "The plea that evidence of guilt must be secret is abhorrent to free men, because it provides a cloak for the malevolent, the misinformed, the meddlesome, and the corrupt to play the role of informer undetected and uncorrected." US ex rel Knauff v Shaughnessy, 338 US 537, 551 (1950)(Jackson, J, dissenting).

REC

EIVED

by MSC

6/2/2022 1:48:54 PM

Page 6 of 39

whether the candidate has enough signatures to meet the statutorily required

threshold. (Id.)

Significantly, the report admits that “the Bureau has previously not developed

a separate review procedure for fraudulent petition sheets.” (Id.) Thus, “in the past,”

the Bureau “would review sheets and signatures individually if identified during face

review or during a challenge.” (Id.) However, in this case, the Bureau averred that

“because of the unprecedented number of [subjectively] fraudulent petition sheets

consistent of invalid signatures during the initial review of petition sheets . . . it was

not practical to review these sheets individually during the course of ordinary face

review and challenge processing.” (Id.)

In other words, the Bureau recognized its duty under the law, but claimed it

simply hadn’t the resources to carry out that duty and instead the Bureau came up

with a completely new, novel and shortcut process that included “an additional step.”

(Id.) Put simply, the Bureau cut corners: “Prior to face review, staff reviewed each

candidates’ petitions for petitions signed by circulators who were suspected of

submitting fraudulent sheets” and “separated” them from the remaining petition

sheets for each candidate.” (Id.) (emphasis added.)

Then after separating these allegedly fraudulent sheets, the Bureau staff did

not do a comparison of every single signature they contained. Rather, “staff

conducted a targeted signature check of signatures across each circulator’s sheets for

each candidate to confirm that theses circulators’ submissions in fact consisted of

fraudulent sheets with invalid signatures.” (Id. at 4-5.) “Targeted” in Markey’s case

REC

EIVED

by MSC

6/2/2022 1:48:54 PM

Page 7 of 39

seems to mean that merely “ten” out of 21, 804 signatures were checked against the

QVF, however, it now seems Defendants-Appellees have additional information that

they only now disclosed in their response to Markey’s complaint. (Ex. B, Markey

Rev., p 2; see also Def’s 6/1/22 Resp.) After determining “that all reviewed

signatures”—but not all signatures—“appearing on sheets signed by the fraudulent-

petition circulators were invalid,” the Bureau counted up the total number of

signatures on the allegedly fraudulent sheets and subtracted it from the number of

signatures submitted by the candidate. (Ex. B, Markey Rev., p 2, p 5.) If the

candidate still had more than enough signatures to meet the required threshold, “the

petitions were then put through the fact review and challenge process.” (Id. at 5.) If

not, then the Bureau “recommended the Board determine the petition insufficient.”

(Id.)

In all, Bureau compared about seven-thousand of the more than sixty-

eight-thousand signatures at issue against the QVF. Therefore, nearly ninety percent

of signatures were not compared in the flagged sheets to confirm that they consisted

of only fraudulent signatures as suspected across all campaigns vying to get placed

on the August 2, 2022 primary ballot. (See Id., p. 4.) The Bureau’s review of the

portion of the flagged sheets reportedly found that an astonishing none of the

approximately seven-thousand signatures compared against the QVF had “any

redeeming qualities.” (See Ex. A, Stf. Rep., p 5.) Indeed, during its hyper-diligent

review of now all candidates’ nominating petitions—even those like Markey who

received no challenges—the Bureau allegedly uncovered a fraud ring that

REC

EIVED

by MSC

6/2/2022 1:48:54 PM

Page 8 of 39

coincidently implicated five gubernatorial candidates. (See generally, Ex. A, Stf. Rep.)

Based on this unlawful presumption of invalidity described above, the Bureau

unilaterally decided that more than sixty-thousand signatures the Bureau admits it

or its staff did not individually review were categorically invalid for no other reason

than the name of the circulator who had submitted them. This resulted in Markey

(among other candidates) purportedly falling under the fifteen-thousand-signature

threshold. (See Ex. B, Markey Rev., p 1.)

A number of complaints were filed against several candidates’

nominating petitions, two such campaigns that received challenges were other

gubernatorial candidates. (See Id. at 3.) However, unlike the James Craig and Perry

Johnson campaigns, Markey never received a challenge to his nominating petitions.

(See Ex. B, Markey Rep. p 3; c.f. Ex. B, Craig Rep., p 4; Ex. C, Johnson Rep., p 6.)

According to the Bureau’s review, although Markey had submitted a total of

21,804 signatures, the Bureau declared that only 4,430 were considered valid. (See

Ex. B, Markey Rev., p 1.) Because 4,430 signatures is far less than the fifteen-

thousand signature requirement, the Bureau recommended that the Board of

Canvassers (“the Board”) determine Markey’s petition was insufficient to certify him

as a gubernatorial candidate. (Id at 3.) The review identified a total 17,374

signatures the Bureau deemed to be invalid. (Id. at 1.) Specifically, the Bureau

concluded that:

a. Ten signatures were invalid because these ten signatures did not match the QVF.

REC

EIVED

by MSC

6/2/2022 1:48:54 PM

Page 9 of 39

b. Two signatures were invalid because they “had been

cancelled.”

c. The report also identified that these two signatures identified above were also incomplete (“the use of a first name and last initial”) that had been cancelled, eighty-one signatures were invalid because of “[a]ddress errors (no street address or rural route given)”

d. Four signatures were identified as invalid because of

“[c]haracteristics of certain fraudulent-petition circulators” (multiple signatures appear to have been written by the hand)”.

e. 17,374 signatures were invalid because they were “on sheets submitted by fraudulent-petition circulators.” [Id.]

In addition to all the above procedural defects, the Bureau’s review shows

computational errors negatively affecting Markey’s signature count. Based on

records from Markey’s campaign and the staff report, the Bureau wrongly assigned

an extra two-thousand-five-hundred invalid signatures to Markey’s total. (See Id.)

In one instance, the Bureau attributed 1980 invalid signatures to “Indira

Radcliff.” (Id. at 2.) However, Markey’s campaign records reveal that Indira Radcliff

submitted only 470 signatures. As a result, even if all the signatures Radcliff

collected were invalid, the Bureau subtracted an extra 1510 signatures from Markey’s

total number of valid signatures. That’s a roughly eighty-percent-of-Markey’s total

signatures blunder. And the Bureau is making these kinds of allegations with those

kinds of errors in its own documentation. Furthermore, the Bureau also attributed

REC

EIVED

by MSC

6/2/2022 1:48:54 PM

Page 10 of 39

465 invalid signatures to a circulator named “Siarra Brown”—a person who did not

even collect signatures for Markey’s campaign. (See Id. at 1.)

Incredibly, the Bureau used an unprecedented targeting “process” to strike

every single signature from any individual or entity whom it declared to be a

“fraudulent-petition circulator.” In other words, instead of reviewing each signature

for authenticity with the presumption that every signature on every sheet is valid,

the staff indiscriminately struck more than sixty-eight-thousand signatures,

including 17,374 from Markey’s nominating petitions based on the Bureau’s decision

to ignore its statutory duty.

The Bureau described its process for identifying allegedly fraudulent

signatures:

Signatures from the following 24 fraudulent- petition circulators were included in Mr. Markey's submission:

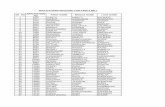

Davon Best 397 signatures Brianna Briggs 883 signatures Siarra Brown 465 signatures Charles Calvin 50 signatures Nicholas Carlton 197 signatures DeShawn Evans 1,529 signatures Justin Garland 1,125 signatures LeVaughn Hearn 338 signatures Briana Heron 1,038 signatures Aaliyah Ingram 393 signatures Danyil Lancaster 755 signatures Teddrick Lee 1,293 signatures Niccolo Mastromatteo 319 signatures Indira Radcliffe 1,980 signatures Aaliyah Render 359 signatures Priya Render 1,535 signatures Giovannee Smith 928 signatures

REC

EIVED

by MSC

6/2/2022 1:48:54 PM

Page 11 of 39

Tremari Smith 474 signatures Ryan Snowden 594 signatures Stephe Tinnin 929 signatures Freddie Toliver 8 signatures Diallo Vaughn 791 signatures Yazmine Vasser 347 signatures William Williams 647 signatures Total 17,374 signatures

The Bureau then asserted that “these circulators submitted signatures with

the patterns consistent with other filings where alleged fraud was discovered. (See

Ex. B, Markey Rev., pp 1-2.) While the Bureau claimed 17,274 signatures on

Markey’s petitions were the product of widespread fraud, the Bureau only specifically

identified fifteen signatures as fraudulent—but only ten were compared to the QVF.

(See Id. at 2-3.) On information and belief, to this day, but for ten signatures, no one

has ever compared each of the remaining 17,264 signatures on Markey’s petition that

were disqualified using the QVF. Of the 21,804 signatures the Bureau reports

Markey having submitted, the Bureau admitted that 17,374 of them were invalid for

having been submitted by “fraudulent circulators.” (Id. at 1.) In other words, the

Bureau presumed that nearly eighty percent of Markey’s signatures were invalid

and affirmed its presumption after reviewing an unknown exact number of these

allegedly fraudulent signatures.

The Bureau recognized that it has no “reason to believe that any specific

candidate or campaigns were aware of the activities of fraudulent-petition

circulators.” (See Ex. A, Stf. Rep., p 5.) Nonetheless, Markey is being punished by

Bureau’s on-the-fly invention of its extra-statutory process to cut corners because the

REC

EIVED

by MSC

6/2/2022 1:48:54 PM

Page 12 of 39

Bureau claims it could not comply with the law. Yet, simultaneously, it expects

everyone else to comply with the Bureau’s own subjective interpretation of the law.

On May 26, 2022, the Board held a public hearing on Markey’s nominating

petitions, although this hearing was rushed and included a number of other

gubernatorial candidates and candidates down the ballot. At the hearing, the

Bureau’s director, Jonathan Brater (“Brater”), admitted that the Bureau

recommended invalidating signatures without checking each of them against the

QVF.

Specifically, the Bureau’s report discussed that of the more than sixty-eight-

thousand signatures submitted by the alleged fraudulent circulators, the Bureau only

compared about seven-thousand of those signatures (a little more than ten percent)

against the QVF. See, Michigan Department of State / Secretary of State (2022, May

26) Board of Canvassers Meeting May 26, 2022, YouTube.

https://www.youtube.com/watch? V=S5njPEX4PVE&t=12864s, at 1:00:55 (9:47:55

AM) (herein after “Meeting Video.”) At no point did Brater ever state how many

signatures on Markey’s petitions were reviewed by the Bureau. Brater certainly

never said he personally reviewed the signatures. But at one point, Brater

maintained that Michigan law does not require the Bureau to check every signature

against the QVF.

The Board then took up the following motion on Markey’s nominating petition:

REC

EIVED

by MSC

6/2/2022 1:48:54 PM

Page 13 of 39

Time Lapse

Speaker Text

@5:06:52: Chair Shinkle: Next item on the agenda is #13 report on Michael Markey.

@ 5:06:56: Vice Chair Gurewitz:

I move that the board accept the staff recommendation and find the nominating petition

filed by Michael Markey, insufficient.

@ 5:07:06: Member Bradshaw:

Support.

@5:07:07 Chair Shinkle: It's been moved and supported to find

...(mumbling) ... support the staff recommendation is insufficient for Michael

Markey, discussion on that motion, seeing none, I'll ask

Adam to call the roll.

@5:07:18 Adam Fracassi taking roll:

Chair Shinkle?

@5:07:19 Chair Shinkle: No.

@5:07:21 Adam Fracassi: Vice Chair Gurewitz?

@5:07:22 Vice Chair Gurewitz:

Yes.

@5:07:23 Adam Fracassi: Member Daunt?

@5:07:24 Member Daunt: No.

@5:05:25 Adam Fracassi: Member Bradshaw?

REC

EIVED

by MSC

6/2/2022 1:48:54 PM

Page 14 of 39

@5:07:26 Member Bradshaw:

Yes.

@5:07:27 Adam Fracassi: Mr. Chair you have 2 yays and 2 nays.

@ 5:07:29 Chair Shinkle: That's the five for the governors right there, my

comments and Tony Daunt's, the reason for my no vote.

As the Board deadlocked two-to-two along partisan lines, the motion to accept the

Bureau’s recommendation and find that Markey’s nominating petitions were

insufficient, did not carry. In other words, having rejected the Bureau’s

recommendation to find Markey’s petition insufficient, Markey seems to have

logically been certified on the ballot. Indeed, Michigan law supports the presumption

of a candidate’s validity unless proven otherwise by the government so as to not

disenfranchise voters.

However, Brater interjected to declare, via mis-characterizations of what the

Board actually voted on, the motion’s disposition as follows:

REC

EIVED

by MSC

6/2/2022 1:48:54 PM

Page 15 of 39

Time Lapse

Speaker Text

@5:10:15 Brater: If I could, just to note, where we are with these candidates

we just voted on just for everyone's information, so

because there was not three votes to place the candidates

on the ballot to find their petition sufficient, that the

disposition of the board is that those eight candidates at this

time are not going on the ballot. So those candidates, ah, if they disagree with that, will

need to file a lawsuit, hopefully promptly.

Thus, no vote was actually taken on whether Markey should be certified for

inclusion on the ballot. Upon information and belief, the Board will not, contrary to

the logical result of the specific vote of the Board, certify Markey for the August 2,

2022 primary ballot by the required three affirmative votes. As a result of the

Bureau’s illegal actions, based on Brater’s decree, Markey has been improperly

excluded from the primary-election ballot.

B. Procedural Summary

On May 29, 2022, Markey filed an original action for mandamus in the Court

of Appeals. (See generally, 5/29/22 Compl.) Markey requested an order requiring

Defendants-Appellees Michigan Department of State (“the Department”), the

Bureau, and the Board to place Markey on the August 2, 2022 primary-election ballot

REC

EIVED

by MSC

6/2/2022 1:48:54 PM

Page 16 of 39

immediately. Defendants-Appellees responded on June 1, 2022, and argued,

basically, that Defendants-Appellees have broad discretion to administer Michigan’s

elections how they see fit within the limits of their resources. (See generally, 6/1/22

Resp. Compl.) The Court of Appeals denied Plaintiffs-Appellants’ complaint for

mandamus, and in so doing cited its newly published opinion in Johnson v Bd of State

Canvassers, ___ Mich App ___ (2022) (Docket No. 361564). (See Ex. G, 6/1/22 MCOA

Ord; Ex. H, 6/1/22 Johnson Opinion.)

ARGUMENT

This Court should grant Plaintiffs-Appellants’ application for leave to appeal

or other appropriate preemptory relief. This case presents issues of significant public

interest, and there is no clear precedential guidance. (See Ex. G, 6/1/22 MCOA Ord.)

(“the instant case involves questions of significant public interest . . . .”.) It also calls

into question the extent of the legal authority that Defendants-Appellees, and the

actors within them in their official capacities, wield when it comes to shaping

Michigan voters’ choices in a primary election. These reasons justify review under

MCR 7.305(B)(2).

Further, the issues presented here involve “legal principle[s] of major

significance to [Michigan’s] jurisprudence.” MCR 7.305(B)(3). Should it stand that

the Bureau of Elections may invent procedure on the fly that results in an

unprecedented number of gubernatorial candidates being thrown off the primary-

election ballot for no wrongdoing of their own, the invitation for tick-for-tack turmoil

in our elections moving forward will be flagrant. Michigan needs clear guidance from

REC

EIVED

by MSC

6/2/2022 1:48:54 PM

Page 17 of 39

this Court so that everyone who decides to run for office in the future will know

exactly what the rules of the game are. Otherwise, there can be no fair process to

bring a robust field of candidates to Michigan’s voters. To permit bureaucratic

creativity to control Michigan’s elections rather than law will forever leave Michigan’s

voters at the mercy of unelected bureaucrats. Thus, Michigan requires this Court’s

wisdom on these significant issues, and it should therefore grant leave. See Id.

* * *

In the event it so grants, Plaintiffs-Appellants offer the following arguments

based on the statutory text and with the backdrop that Michigan courts have

historically resolved such matters in a way that does not disenfranchise its voters:

I. Markey is Entitled to Mandamus and Reversal of the Court of Appeals is Therefore Warranted

This Court should reverse the decision of the Court of the Appeals to deny

Markey’s complaint for mandamus; a subsequent order from this Court to place

Markey on the August 2, 2022 primary-election ballot is then warranted because

Markey is entitled to mandamus. This is because the Bureau ignored its clear legal

duty to presume Markey’s candidacy valid unless and until it received a challenge to

Markey’s nominating petitions, and it could prove Markey knowingly committed

fraud. Because Markey received no challenge and committed no such fraud, as is

undisputed, Markey had the clear legal right to enjoy the statutory presumption that

his candidacy is best left to Michigan’s voters in the primary election. Accordingly,

Defendants-Appellees had the ministerial duty of placing Markey on the primary-

REC

EIVED

by MSC

6/2/2022 1:48:54 PM

Page 18 of 39

election ballot as a choice for Michigan’s electorate. Defendants-Appellees, however,

refuse to perform that ministerial duty based on their rogue and on-the-fly

interpretation of the law. Therefore Markey has no other remedy than mandamus.

The Court of appeals erred in not recognizing this, and reversal of it is therefore

appropriate.

A. Standard of Review

Questions of statutory interpretation are reviewed de novo. TCF Nat’l Bank v.

Dep’t of Treasury, 330 Mich App 596, 605 (2019). While the decision on whether to

grant mandamus is reviewed for abuse of discretion, this Court reviews underlying

questions of law regarding the government’s clear legal duties and its citizens’ clear

legal rights de novo. See Citizens Protecting Michigan’s Constitution v Secretary of

State, 503 Mich 42, 59 (2018); Berry v Garrett, 316 Mich App 37, 41 (2016). “A trial

court abuses its discretion when its decision falls outside the range of reasonable and

principled outcomes.” Rental Props Owners Ass’n of Kent Co v. Kent Co. Treasurer,

308 Mich App 498, 531 (2014) (quotation marks and citation omitted.) “An error of

law necessarily constitutes an abuse of discretion.” Denton v Dep't of Treasury, 317

Mich App 303, 314 (2016).

B. Markey Satisfies the Elements for Mandamus

Markey satisfies the elements for mandamus, and this remedy is appropriate

in this case. “‘Mandamus is the appropriate remedy for a party seeking to compel

action by election officials’” Attorney General v. Board of State Canvassers, 318 Mich

App 273, 283 (2008) . A writ of mandamus is appropriate where Markey satisfies

four elements, and meets additional clarifying criteria:

REC

EIVED

by MSC

6/2/2022 1:48:54 PM

Page 19 of 39

(1) [Markey] has a clear legal right to performance of the specific duty sought, (2) [Defendants-Appellees] ha[ve] the clear legal duty to perform the act requested, (3) the act is ministerial, and (4) no other remedy exists that might achieve the same result.

This Court may also ‘enter any judgment or order or grant further or different relief as the case may require[.]” MCR 7.216(A)(7).[3] The issuance of a writ of mandamus rests within the discretion of this Court. “[Markey] bears the burden of demonstrating entitlement to the extraordinary remedy of a writ of mandamus.’

A clear legal right is a right ‘clearly founded in, or granted by, law; a right which is inferable as a matter of law from uncontroverted facts regardless of the difficulty of the legal question to be decided.’ [State Canvassers, 318 Mich. App. at 248-249 (internal citations omitted).]

There is no dispute that Defendants-Appellees must follow their clear legal statutory

duty. Whether Defendants-Appellees were burdened by a clear legal duty, and

therefore Markey enjoyed the clear legal right provided by that duty, is a matter of

statutory interpretation.

When interpreting statutes related to Michigan election law, the following

principles apply:

When interpreting a statute, this Court's primary goal is to ascertain the intent of the Legislature. We first review the language itself because the words of the statute provide the most reliable evidence of the Legislature's intent. We afford every word and phrase of the statute its plain and ordinary meaning unless otherwise statutorily defined. We may consult a dictionary to give words their common and ordinary meanings. If the statute's language is clear and unambiguous, we may not engage in judicial construction. When interpreting law governing elections, we must construe the statutes ‘as far as possible in a way which prevents the disenfranchisement of

3 This Court has the same authority MCR 7.316(A)(7).

REC

EIVED

by MSC

6/2/2022 1:48:54 PM

Page 20 of 39

voters through the fraud or mistake of others.’ [State Canvassers, 318 Mich. App. at 250 (internal citations omitted) (emphasis added).]

Additional principles of statutory construction apply:

The words of the statute are the most reliable evidence of the Legislature's intent, and this Court must give each word its plain and ordinary meaning. ‘In interpreting the statute at issue, [this Court] consider[s] both the plain meaning of the critical words or phrase as well as ‘its placement and purpose in the statutory scheme.’ “When a statute's language is unambiguous, the Legislature must have intended the meaning clearly expressed, and the statute must be enforced as written.” [Stumbo v Roe, 332 Mich App 479, 484-485 (2020) (internal citations omitted).]

Central to this Court’s analysis is the placement of words and their contextual

meaning as adopted by the Legislature. See Dep’t of Talent & Economic

Development/Unemployment Ins. Agency v Great Oaks Country Club, Inc., 507 Mich

212, 226-227 (2021). Words used in statutes are not read in a vacuum, but instead

are “’read in context with the entire act, and the words and phrases used there must

be assigned such meanings as are in harmony with the whole of the statute, construed

in the light of history and common sense.,’” Sweatt v Dep’t of Corrections, 468 Mich

172, 179 (2003), quoting Arrowhead Dev. Co. v Livingston Co. Rd. Comm., 413 Mich.

505, 516 (1982) (emphasis added).

Still poignant to this day, “ ‘There is a fundamental difference between actions

taken to get a candidate’s name on the ballot and actions taken to prevent it from

appearing.’ ” Deleeuw v State Bd. of Canvassers, 263 Mich App 497, 504 (2004). In

sum, Deleeuw, stands for the proposition that the interests of the public are better

served by having the names of candidates placed on the ballot rather than by

REC

EIVED

by MSC

6/2/2022 1:48:54 PM

Page 21 of 39

removing them.” Martin v Secretary of State Canvassers, 280 Mich App 417, 429, 504

(2008) (overruled on other grounds), citing Deleeuw, 263 Mich App at 504.

Central to the issue of Defendants-Appellees’ invention of procedure in

violation of their clear legal duty here, which deprived Markey of his clear legal right

is the proper interpretation of the following statute:

If after a canvass and a hearing on a petition under section 476 or 552 the board of state canvassers determines that an individual has knowingly and intentionally failed to comply with subsection (8) or (10), the board of state canvassers may impose 1 or more of the following sanctions:

(a) Disqualify obviously fraudulent signatures on a petition form on which the violation of subsection (8) or (10) occurred, without checking the signatures against local registration records.

(b) Disqualify from the ballot a candidate who committed, aided or

abetted, or knowingly allowed the violation of subsection (8) or (10) on a petition to nominate that candidate. [MCL § 168.544c(11)(a-b) (emphasis added).]

The operative word here is “obviously.” Indeed, turning to a dictionary, it means “as

plainly evident” to all. Merriam-Webster’s Dictionary Online (2022). As used in the

statute, something cannot be “obvious” if it’s not specifically looked at, or viewed by

an examining human being. MCL § 168.544c(11)(a). This means each signature must

be reviewed in order to determine whether it is obviously fraudulent. Only in so doing

may MCL § 168.544c(11)’s express requirement that only obviously fraudulent

signatures be struck from a petition form be met. Indeed, the qualifier, “obviously,”

serves as clarification that not only fraudulent signatures may be stricken—but only

those that are obviously so. See MCL § 168.544c(11)(a). This is the “common-sense”

reading of MCL § 168.544c(11)(a)’s plain language, read within the context of

REC

EIVED

by MSC

6/2/2022 1:48:54 PM

Page 22 of 39

Michigan election law so as to not disenfranchise Michigan voters. See Sweatt, 468

Mich. at 179; State Canvassers, 318 Mich. App. at 250. Were this not the case, the

Legislature would have written MCL § 168.544c(11)(a) to read something like, “the

Bureau may strike any petition signatures it deems to be fraudulent.” However, the

Legislature instead required fraudulent signatures to be “obviously fraudulent”

before they could be excluded without verification from the local voters’ records.

What is more, MCL § 168.544c(11) and its Sub (b) require that an “individual”

and a “candidate” knowingly and intentionally submit fraudulent signatures on a

nominating petition before the candidate can be removed from the ballot. In short,

these statutory provisions, read as a harmonious whole, permit the extreme sanction

of kicking a candidate off the ballot altogether be as a result of the candidate’s

knowing and intentional participation in fraud. See MCL § 168.544c(11), (b); Sweatt,

468 Mich at 179. If there is no evidence of a candidate’s knowing participation with

fraud, then the presumption is that the candidate is on the ballot so long as the

facially-sufficient nominating petitions have been submitted. See e.g. Id.

This comports with MCL § 168.544c(11)’s express incorporation of MCL §

168.552:

Upon the filing of nominating petitions with the secretary of state, the secretary of state shall notify the board of state canvassers within 5 days after the last day for filing the petitions. The notification shall be by first-class mail. Upon the receipt of the nominating petitions, the board of state canvassers shall canvass the petitions to ascertain if the petitions have been signed by the requisite number of qualified and registered electors. Subject to subsection (13), for the purpose of determining the validity of the signatures, the board of state canvassers may cause a doubtful signature to be checked against

REC

EIVED

by MSC

6/2/2022 1:48:54 PM

Page 23 of 39

the qualified voter file or the registration records by the clerk of a political subdivision in which the petitions were circulated. [MCL § 168.552(8) (emphasis added).]

In the event the Board considers a specific signature’s validity to be called into

question, the process in such circumstance is unambiguous. The QVF must be

utilized. If the QVF does not contain a digitized signature, the township clerk shall

compare the petition signature to the signatures contained on the master card:

The qualified voter file may be used to determine the validity of petition signatures by verifying the registration of signers. If the qualified voter file indicates that, on the date the elector signed the petition, the elector was not registered to vote, there is a rebuttable presumption that the signature is invalid. If the qualified voter file indicates that, on the date the elector signed the petition, the elector was not registered to vote in the city or township designated on the petition, there is a rebuttable presumption that the signature is invalid. The qualified voter file shall be used to determine the genuineness of a signature on a petition. Signature comparisons shall be made with the digitized signatures in the qualified voter file. The county clerk or the board of state canvassers shall conduct the signature comparison using digitized signatures contained in the qualified voter file for their respective investigations. If the qualified voter file does not contain a digitized signature of an elector, the city or the township clerk shall compare the petition signature to the signature contained on the master card. [MCL § 168.552(13) (emphasis added).]

The Legislature puts further restrictions on any bureaucratic creativity when a

candidate’s nominating petitions are challenged directly:

If the board of state canvassers receives a sworn complaint, in writing, questioning the registration of or the genuineness of the signature of the circulator or of a person signing a nominating petition filed with the secretary of state, the board of state canvassers shall commence an investigation. Subject to subsection (13) [above], the board of state canvassers shall verify the registration or the genuineness of a signature as required by subsection (13). If the board is unable to verify the genuineness of a signature on a petition, the board shall cause the petition to be forwarded to the proper city clerk or township clerk to

REC

EIVED

by MSC

6/2/2022 1:48:54 PM

Page 24 of 39

compare the signatures on the petition with the signatures on the registration record, or in some other manner determine whether the signatures on the petition are valid and genuine. The board of state canvassers is not required to act on a complaint respecting the validity and genuineness of signatures on a petition unless the complaint sets forth the specific signatures claimed to be invalid and the specific petition for which the complaint questions the validity and genuineness of the signature or the registration of the circulator, and unless the complaint is received by the board of state canvassers within 7 days after the deadline for filing the nominating petitions. After receiving a request from the board of state canvassers under this subsection, the clerk of a political subdivision shall cooperate fully in determining the validity of doubtful signatures by rechecking the signatures against registration records in an expeditious and proper manner. The board of state canvassers may extend the 7-day challenge period if it finds that the challenger did not receive a copy of each petition sheet that the challenger requested from the secretary of state. The extension of the challenge deadline under this subsection does not extend another deadline under this section. [MCL § 168.552(8) (emphasis added).]

To tie it all together, MCL § 168.544c(11)’s sanctions are unavailable to the

Bureau and the Board unless and until they follow MCL § 168.552(8)’s clear

procedure, as tempered by MCL § 168.552(13). These two statutes working in

conjunction is what provides each candidate due process, and expressly imparts the

presumption of validity to a candidate’s nominating petitions unless each signature

is verified at the county level or against the QVF, or a challenge is received within

seven days from submission and a proper investigation as to the credibility of the

complaint is conducted. See MCL § 168.552(8), (13). Unless and until these clear

statutory triggers are made, the Board and the Bureau have the clear—as outlined

above—legal duty to certify nominating petitions for the primary-election ballot.

And, again, the extreme sanction of barring a candidate from the ballot is only

available if the Board first completes its investigative duties under Section 552 and

REC

EIVED

by MSC

6/2/2022 1:48:54 PM

Page 25 of 39

after a meaningful hearing where a candidate may rebut allegations of fraudulent

signatures. See MCL § 168.544c(11) (If after a canvass and a hearing on a petition

under section . . . 552 . . . .”).

Here, virtually none of that happened. Indeed, the Bureau claimed that it

experienced more volume with regard to nominating petitions in this election cycle

than ever before, which it claimed called for bureaucratic creativity. (See Ex. D, Stf.

Rep., pp 3-5.) As such, and instead of following its own long-standing enumerated

procedures, the Bureau invented a new procedure that violated the above statutory

procedures. Defendants-Appellees admit staff at the Bureau only “spot checked the

sheets that they thought were fraudulent by checking about ‘seven-thousand’

signatures against the QVF. Of the seven-thousand that they checked, not one was

verifiable.” (See MI Senate TV at 9:47:55 AM (1:00:53).) Bureau of Elections Director

Jonathan Brater claimed, “”We did look at every single line. What we were not able

to do with the time we had available, was to look every single one up in QVF. So

instead we looked at as many as we could.” (See Id. at 1:11:09.)

Importantly, while the statute may leave some ambiguity on exactly how the

Board, while perhaps practically using the Bureau as its investigative arm, is to

conduct its investigation into challenged nominating-petition signatures, see Barrow

v Wayne County Board of Canvasser, ____ Mich App ____, ____ (2022), slip op at 6,

but the Board does not have discretion on the process laid out by statute in that it

must verify questionable signatures in either the QVF or at the county level. See

MCL §§ 168.544c(11), 168.552(8), (13). In other words, Defendants-Appellants have

REC

EIVED

by MSC

6/2/2022 1:48:54 PM

Page 26 of 39

the clear legal duty to follow the process laid out by the Legislature notwithstanding

time constraints or difficulties; such is the nature of a duty, it’s often very

inconvenient. Because Defendants-Appellees effectively admit to violating their clear

legal duty, as outlined in the above-cited statutes, Mandamus’ first element is

satisfied. See State Canvassers, 318 Mich. App. at 248-249.

This clear legal duty imparted on Defendants-Appellees granted Markey the

clear legal right to enjoy the due process laid out by statute with regard to Markey’s

nominating petitions. See MCL §§ 168.544c(11), 168.552(8), (13). Indeed, “Upon the

filing of nominating petitions with the secretary of state, the board of state canvassers

shall canvass the petitions to ascertain if the petitions have been signed by the

requisite number of qualified and registered electors.” MCL § 168.552(8). This

review is to take place “[s]ubject to subsection (13),” which demands “[t]he qualified

voter file shall be used to determine the genuineness of a signature on a petition.

Signature comparisons shall be made with the digitized signatures in the qualified

voter file. The county clerk or the board of state canvassers shall conduct the

signature comparison using digitized signatures contained in the qualified voter file

for their respective investigations.” MCL § 168.552(13).

In other words, Defendants-Appellants must afford Markey the benefit of the

doubt on every single signature, and may only strike individual signatures that do

not match up with the QVF during. See Id. Because it is undisputed that Defendants-

Appellees did no such thing here, Markey is entitled to the clear legal right to the

presumption of validity regarding his nominating petitions. See e.g. Wilcoxon v. City

REC

EIVED

by MSC

6/2/2022 1:48:54 PM

Page 27 of 39

of Detroit Election Com’n, 301 Mich. App. 619, 640 (2013) (electors’ undated

signatures on nominating petitions for city clerk were presumed to be valid); Jaffe v.

Oakland Co. Clerk, 87 Mich. App. 281, 285 (1978) (“Signatures appearing on petitions

filed with the Secretary of State for initiative and referendum are presumed valid,

and the burden is on the protestant to establish their invalidity by clear, convincing

and competent evidence.”). Indeed, the only way Defendants-Appellees are permitted

to exclude any signatures under MCL § 168.544c(11)(a)) is if they are “obviously

fraudulent,” which as previously discussed requires an examination of the QVF. This

subsection allows signatures to be excluded without checking the local records, but it

does not excuse the requirement that the signatures be checked against the digitized

signatures in the QVF. Presumably if the Legislature had intended to excuse

compliance with that requirement, it would have said so by use of language

appropriately signifying that intent. It did not do so and, thus, such an intent should

not be discovered based upon language inserted by judicial fiat.

This notion of the presumption of validity is further parroted in the

Department’s own manual, which one would presume the Bureau would need to

follow. (See Ex. E, SOS Man., pp 12-13.) In other words, according to both the

Department and Michigan law, unless a signature is so obviously fraudulent that,

upon actual inspection, it has absolutely no redeeming qualities—it is to be counted

towards the fifteen-thousand-signature threshold Markey was required to meet for

governor. See MCL § 168.544c(11)(a); (Ex. E, Nm. & Qual. Pet. Man., pp 12-13.) And

rightly so because, in addition to being contrary to the above cited statutory authority,

REC

EIVED

by MSC

6/2/2022 1:48:54 PM

Page 28 of 39

the outcome of a decision to disqualify him would unjustly punish Markey, and

disenfranchise Michigan’s voters based on the acts of the criminals who committed

the allegedly fraudulent acts. See Id; State Canvassers, 318 Mich App at 250 (“When

interpreting law governing elections, we must construe the statutes ‘as far as possible

in a way which prevents the disenfranchisement of voters through the fraud or

mistake of others.’”). Construing any statute to limit the right of Michigan’s voters

to enjoy a robust field of candidates to any office would be to disenfranchise voters by

removing their options. This is something Michigan’s long-standing jurisprudence

prohibits, and the Department’s own manual instructs against.

Moreover, the vote at the May 26, 2022 hearing was to “accept the staff

recommendation and find the nominating petition filed Michael Markey,

insufficient.” (Id., at 5:06:52 – 5:07:02.) The vote on this motion did not pass due to

partisan deadlock. (See Id.) Therefore, the Bureau’s recommendation to deem

Markey’s nominating petition was rejected. (See Id.) Brater then interjected by

declaring Markey was off the ballot. (See Id.) However, this does make logical sense,

and Brater has no authority to override the Board’s vote. Nor did Brater have any

authority to declare action by the Board did not take. There has not been a vote by

the Board as to whether Markey should be placed on the ballot. Thus, Markey has

the legal right to enjoy the benefit of the Board’s vote with respect to the actual motion

that was before it. As such, the second element of mandamus is doubly met. See

State Canvassers, 318 Mich. App. at 248-249.

REC

EIVED

by MSC

6/2/2022 1:48:54 PM

Page 29 of 39

Moving on, the third element for mandamus requires the act in question to be

“ministerial.” “A ministerial act is one in which the law prescribes and defines the

duty to be performed with such precision and certainty as to leave nothing to the

exercise of discretion or judgment.” Hillsdale Co. Senior Servs., Inc. v. Hillsdale

Co., 494 Mich. 46, 58 n. 11 (2013) (quotation marks and citation omitted). There is

no question that, when no challenges have been brought to a candidate’s nominating

petitions, placement of the candidate on the primary ballot is “ministerial.” Indeed,

when a sufficient number of signatures are obtained for a nominating petition, and

there has been no lawful showing that the signatures are invalid, see MCL §§

168.544c(11), 168.552(8), (13), the Board’s duty to place the proposal or candidate on

the ballot is a ministerial function. See Citizens for Protection of Marriage v. Board

of State Canvassers, 263 Mich. App. 487, 492-493 (2004) (internal citations omitted).

In this case, it is undisputed that Markey’s petition for inclusion on the ballot was

supported by a more-than sufficient number of facially valid signatures. And there

has been no legally sufficient basis to conclude that any more than ten of those

signatures were legally invalid. Thus, Defendants’ ministerial duty is clear, and

mandamus’ third element is satisfied. See State Canvassers, 318 Mich. App. at 248-

249.

Finally, mandamus’ fourth element demands that there is no other remedy

that exists that is capable of achieving Markey’s presence on the August 2, 2022

primary ballot. Indeed, there is no other way, both legally and practically speaking,

REC

EIVED

by MSC

6/2/2022 1:48:54 PM

Page 30 of 39

for Markey to be placed on the ballot other than a writ of mandamus. Markey

satisfies the fourth element.

The elements of mandamus are met for the reasons stated above, and an order

to Defendants-Appellees requiring them to perform their ministerial duties of placing

Markey on the ballot should issue.

* * *

However, the Court of Appeals did not agree. On June 1, 2022, it entered an

opinion for publication finding that gubernatorial candidate Perry Johnson could not

satisfy mandamus and thereby appear on the August 2, 2022 primary-election ballot.

See Johnson v Bd of State Canvassers, ____ Mich App ____ (2022) (Docket No.361564).

The Court of Appeals subsequently entered its order denying Markey’s complaint for

mandamus citing “the same essential reasons set forth in Johnson v Bd of State

Canvassers[.]” (Ex. G, 6/1/22 MCOA Ord.). Respectfully, the Court of Appeals erred

in its decision because, contrary to its assertion, Defendants-Appellees do not enjoy

discretion on the procedure required in reviewing a candidate’s facially valid

nominating-petition signatures.

Importantly, the facts in Markey’s case are fundamentally different than the

facts in Johnson. Unlike Johnson, Markey’s petitions were never challenged, and

nearly no line-by-line scrutiny was given Markey’s signatures. Markey also, unlike

Johnson, found out about purported issues with his signatures via Twitter a couple

days before the May 26, 2022 hearing where Markey’s placement on the primary-

REC

EIVED

by MSC

6/2/2022 1:48:54 PM

Page 31 of 39

election ballot was supposed to be a foregone conclusion based on the lack of

challenges against him.

Nevertheless, the Johnson opinion’s fatal flaw is in its conclusion that

Defendants-Appellees wield discretion in how they are to invalidate nominating-

petition signatures. (See Ex. H, Johnson Op., p 9.) (“Likewise, because the Board had

the discretion to not check each and every signature submitted by the fraudulent-

petition circulators, the act Johnson is seeking to compel defendants to perform is not

ministerial in nature.”) Based on the explicit procedure in verifying the individual

signatures via the QVF and/or the local county records, invalidation of signatures is

a ministerial act and not a discretionary one. See MCL §§ 168.544c(11), 168.552(8),

(13). Indeed, the Court of Appeals cited the precise language in its opinion: “The

qualified voter file shall be used to determine the genuineness of a signature on a

petition.” (See Ex. H, Johnson Op., p 9), quoting MCL § 168.552(13) (emphasis in

original).)

To the extent the Court of Appeals focused on the word “may” in the beginning

of MCL § 168.552(13) to conclude this function is discretionary in this context,

Plaintiffs-Appellants aver that a fair reading of the entire provision as a harmonious

whole reveals signatures can only be invalidated using the QVF. See Id. Thus, the

“may” here best fits within the statutory scheme if read as clarification as to how the

Board is to go about reviewing signatures suspected of being fraudulent. See Id. This

would not be the first time the word “may” has been understood not to be permissive,

but in a mandatory manner when read in the specific context of petitions. See e.g.

REC

EIVED

by MSC

6/2/2022 1:48:54 PM

Page 32 of 39

Committee to Ban Fracking in Michigan v Bd of State Canvassers, 335 Mich App 384,

396 (2021) (internal citations omitted).

Indeed, when reading the word “may” as having a permissive meaning “would

clearly frustrate legislative intent as evidenced by other statutory language or by

reading the statute as a whole,” it should not be read in such a way. Id. And as it

relates to MCL § 168.552(13), given the multiple “shalls” that follow the first “may,”

it is clear the statutory intent here is to require signatures to be invalidated only via

the QVF—an official record. This is bolstered by the presumption of validity, as

explained above, that is also built into the statutory scheme. And the fact that

sanctions for fraud require knowledge and intent before the Board may impose

sanctions. See MCL §§ 168.544c(11)(a-b) . Without an official file like the QVF to

reference, it would be impossible to prove fraudulent signatures were intentionally

or knowingly submitted.

It is clear that these legal questions are challenging, and are made more so by

the extreme time crunch placed on the courts to decide these matters. However, this

Court can correct this error by reversing the Court of Appeals for the foregoing

reasons. This is necessary because, as the Court of Appeals eloquently stated, “ ‘The

primary purpose of the writ of mandamus is to enforce duties created by law, where

the law has established no specific remedy and where, in justice and good

government, there should be one.’ ” (See Ex. H, Johnson Op., p 9), quoting State Bd

of Ed v Houghton Lake Community Sch, 430 Mich 658, 667 (1988).) Markey agrees,

REC

EIVED

by MSC

6/2/2022 1:48:54 PM

Page 33 of 39

and justice and good government should now be served by issuance of the requested

writ of mandamus.

CONCLUSION & RELIEF REQUESTED

For the foregoing reasons, this Honorable Court should grant immediate

consideration of this application for leave to appeal. It should then issue the

requested the writ of mandamus requesting Defendants-Appellees to include Markey

on the August 2, 2022 primary-election ballot. Alternatively, grant leave to appeal

and enjoin the printing of the ballots pending disposition of this matter by this

Honorable Court.

Respectfully submitted, FRASER TREBILCOCK DAVIS & DUNLAP, PC Attorneys for Plaintiff

By: /s/ Garett L. Koger Garett L. Koger (P82115)

Thaddeus E. Morgan (P47394) Paul V. McCord (P61138)

Elizabeth Siefker (P83791)

Dated: June 2, 2022

REC

EIVED

by MSC

6/2/2022 1:48:54 PM