Roman et al 2013 El yacimiento Epimagdaleniense de la Finca de Doña Martina

“Places of Renaissance Mapping” in Herrschaft verorten Politische Kartographie des Mittelalters...

Transcript of “Places of Renaissance Mapping” in Herrschaft verorten Politische Kartographie des Mittelalters...

Medienwandel – Medienwechsel – Medienwissen

Veröffentlichungen des Nationalen Forschungsschwerpunkts»Medienwandel – Medienwechsel – Medienwissen.

Historische Perspektiven«

Herausgegeben von christian kiening und martina stercken

in Verbindung mit jürg glauser, barbara naumann, andreas thier und margrit tröhler

Band 19

ingrid baumgärtner und martina stercken (hg.)

Herrschaft verorten

Politische Kartographie im Mittelalter und in der frühen Neuzeit

Informationen zum Verlagsprogramm:www.chronos-verlag.ch

Umschlagabbildung aus: Georges Grosjean (Hg.), Mapamundi. The Catalan Atlas of the Year 1375, Zürich 1978, Ausschnitt© 2012 Chronos Verlag, ZürichISBN 978-3-0340-1019-1

Publiziert mit Unterstützung des Schweizerischen Nationalfonds zur Förderung der wissenschaftlichen Forschung, der Universität Zürich und der Universität Kassel.

5

Inhalt

ingrid baumgärtner und martina stercken Vorwort 7

martina stercken

Herrschaft verorten. Einführung 9

Politische Räume

ingrid baumgärtner

Das Heilige Land kartieren und beherrschen 27

keith d. lilley

Mapping Plantagenet Rule Through the Gough Map of Great Britain 77

dietrich erben

Anthropomorphe Europa-Karten des 16. Jahrhunderts. Medialität, Ikonographie und Formtypus 99

francesca fiorani

Places of Renaissance Mapping 125

laura federzoni

Cartography, Politics, and Culture in Ferrara at the End of the 16th Century 143

bernd giesen

Verortungen der Eidgenossenschaft im 15. und 16. Jahrhundert 165

6 Persönlicher AutorInnen-Beleg © 2013 Chronos Verlag, Zürich

Strategien der Verortung

yossef rapoport

Reflections of Fatimid Power in the Maps of Island Cities in the ‘Book of Curiosities’ 183

hanna vorholt

Herrschaft über Jerusalem und die Kartographie der heiligen Stadt 211

philipp billion

Die Funktion von Herrschaftszeichen auf mittelalterlichen Portolankarten 229

felicitas schmieder

Anspruch auf christliche Weltherrschaft. Die Velletri/Borgia-Karte (15. Jahrhundert) in ihrem ideengeschichtlichen und politischen Kontext 253

ralph a. ruch

Kartographie und Konflikt im städtischen Kontext. Der ›Plan Bolomier‹ (1429/30) 273

yigit topkaya

Kulturelle Praktiken der Herrschaftsrepräsentation und ihre Zirkulationsräume. Panorama einer historischen Belagerung 293

Wissen und Zeichen

stefan schröder

Wissenstransfer und Kartieren von Herrschaft? Zum Verhältnis von Wissen und Macht bei al-Idrīsī und Marino Sanudo 313

winfried nöth

Medieval Maps: Hybrid Ideographic and Geographic Sign Systems 335

franco farinelli

The Power, the Map, and Graphic Semiotics: The Origin 355

Autorinnen und Autoren 363

125

francesca fiorani

Places of Renaissance Mapping

Renaissance monarchs, city governments, and popes, who were acutely aware of the power of images, grasped quickly the potentials of cartography to articulate their political aspirations. These Renaissance rulers made maps part and parcel of their political iconography, just as they routinely used statues, medals, build-ings, emblems, portraits, rituals, paintings, and scientific instruments as political metaphors, dynastic claims, and mythmaking. Maps and globes appeared in of-ficial portraits as well as in the halls of power of kings and popes, in the audience chambers of civic authorities, in the studies of scholars and merchants, and in the libraries and collections across Europe. Governing bodies, from emperors to popes and kings, as well as republics and rulers of small states, came to regard the patronage of national atlases as one of their duties to control their land lit-erally and symbolically, commissioning new surveys, maps, and views of their dominions. But they were also patrons of cartographic projects that mapped areas that extended well beyond the borders of their jurisdiction, imagining areas of geographical influence that did not correspond to any political unity. Maps of the Old and New World were imaginatively combined with views of important cities, historical scenes of different periods, inscriptions, and landscape details, as well as images of plants and animals in order to articulate the aspirations, dreams, and utopias of their patrons. The cartographic content and meaning of maps varied greatly from place to place and from patron to patron, while the significance of each cartographic project was grounded within the context of its production, the circumstances of its viewing, and the accuracy of its cartographic sources. But generally they answered two related needs: to visualize the real or aspired extent of the political, administrative, and commercial power of their patron and, at the same time, to serve administrative purposes, such as taxation, distribution of resources, and the supply of water. 1

1 For a general introduction to Renaissance cartography see David Woodward (ed.), The History of Cartography, vol. 3: Cartography in the European Renaissance, Chicago 2007, which con-tains important essays on various aspects of Renaissance cartography, including cosmography, nautical charts, star maps, cadastral maps, city views, maps and literature, printing, collecting, technique of mapmaking and projections, national cartographic projects in Italy, Portugal, Spain, German Lands, Low Countries, British Isles, Scandinavia, East-Central Europe, and Russia.

126 Persönlicher AutorInnen-Beleg © 2013 Chronos Verlag, Zürich

Such predilection for cartographic images in the political iconography of Renais-sance rulers can be related to the general interest in modern voyages, the grow-ing availability of printed maps, and the increased use of maps for such diverse activities as learning the classics, calculating the freight of merchandise, reading the Bible, estimating the daily reports on European wars, and administering to the state. But I would argue that the pervasive role of maps in Renaissance political imagery deeply relates also to the cartographic language of the maps themselves, quite literally how places came to be represented the way they did. This close rela-tion between the language of Renaissance maps and the construction of political imagery emerges from an investigation that combines the contextual analysis of the maps, which is generally employed in the study of cartography, with notions of phenomenological philosophy, which instead are rarely applied to maps. The maps of my analysis are printed maps intended for a wide audience and cir-culation, such as the map ‘Russia et Moscovia’ printed by the Dutch cartographer Abraham Ortelius in Antwerp in 1570 (Fig. 1).2 But I also concentrate on painted maps that not only share the cartographic language of printed maps, on which in fact they are based, but often magnify it, such as the fresco map ‘Flaminia’ painted by the Italian mapmaker Egnazio Danti for Pope Gregory XIII around 1580 (Fig. 2).3

Particularly relevant to the political use of cartography are the essays by Richard L. Kagan and Benjamin Schmidt, Maps and the Early Modern State. Official Cartography, pp. 661–679; Roger J. P. Kain, Maps and Rural Management in Early Modern Europe, pp. 705–718; John Hale, Warfare and Cartography, ca. 1450 to ca. 1640, pp. 719–737; Felipe Fernandez-Armesto, Maps and Explorations in the Sixteenth and Early Seventeenth Century, pp. 738–772. On the use of maps in the political iconography of Renaissance rulers see David Buisseret (ed.), Monarchs, Ministers, and Maps. The Emergence of Cartography as a Tool of Government in Early Modern Europe, Chicago 1992; Peter M. Barber, Maps and Monarchs in Europe 1550–1800, in: Robert Oresko, Graham C. Gibbs and Hamish M. Scott (eds.), Royal and Republican Sovereignty in Early Modern Europe. Essays in Memory of Ragnhild Hatton, Cambridge 1997, pp. 75–124; Kristen Lippincott, Power and Politics. The Use of the Globe in Renaissance Portraiture, in: Globe Studies 49–50 (2002), pp. 3–20; Francesca Fiorani, The Marvel of Maps. Art, Cartography and Politics in Renaissance Italy, New Haven/CT 2005.

2 On Ortelius’s map Russia et Moscovia, which was based on the map Russia et Moscovia (London, 1562) made by the English traveler Anthony Jenkinson after his journey to Muscovy in 1557, see Robert W. Karrow, Jr., Mapmakers of the Sixteenth Century and their Maps. Bio-Bibliography of the Cartographers of Abraham Ortelius, 1570, Chicago 1993, pp. 317–320. On the mapping of Russia in the 16th century see Ettore Paratore, La Moscovia nelle carte italiane della rinascenza (Pubblicazioni dell’Istituto di Geografia, serie B, Geostorica), Rome 1976; Patrizia Licini, La Moscovia rappresentata. L’immagine capovolta della Russia nella cartografia rinascimentale europea, Milan 1988; Numa Broc, La geografia del Rinascimento, Modena 1989, pp. 72–75; Fiorani, Marvel (as in fn. 1), pp. 110 f.

3 On Danti’s map Flaminia see Lucio Gambi and Antonio Pinelli (eds.), La Galleria delle Carte Geografiche, 3 vols., Modena 1994, here vol. 1, pp. 305–313; Fiorani, Marvel (as in fn. 1), pp. 157–170.

127

Fig. 1: Abraham Ortelius, Map of Muscovy (‘Russia et Moscovia’), originally published by Anthony Jenkinson in London in 1562, in: Abraham Ortelius, Theatrum orbis terrarum, Antwerp 1570, plate 46.

These printed and painted maps combine imaginatively different systems of rep-resentation (the plan view, the perspective view, and the bird’s-eye view), different modes of description (verbal and visual, cartographic and historical, mathemati-cal and literary), and different signs (indexical, iconic, and symbolic signs). They commingle features of medieval cartography, such as vignettes, writings and other non-mathematical elements, with the Ptolemaic grid, which instead is the quintessential feature of modern cartography.How can we account for the ways in which the cartographic language of these maps constructed a political possession for their patrons and viewers? A contex-tual study would differentiate Ortelius’s and Danti’s maps in terms of authorship, patronage, production, technique, circulation, and reception. It would subsume each map within its cultural, social, political, and religious context and derive its political meaning from the context itself. An unwelcome result of such a study is that the maps themselves, their physicality, their space and their role in the ar-ticulation of the political are lost. The maps are reduced to mirrors of a political construction determined by outside forces, while minimal attention is paid to the mechanisms of communication that make it possible to articulate their political

128 Persönlicher AutorInnen-Beleg © 2013 Chronos Verlag, Zürich

meaning so compellingly. More importantly, a contextual study would elude the explanation of why the maps are the way they are, let alone explain why the world was represented so similarly north and south of the Alps. Equally ineffective would be an explanation based on period labels, formal definitions, differences of artistic genres, or geographical distinctions, since these traditional parameters of history and art history would separate what ostensibly coexists in these im-ages. Even established dichotomies, such as art and cartography, resemblance and difference, similitude and identity as well as pictorial description and geometric abstraction, are surely too rigid to grasp the manifold ways in which the world was represented in Renaissance maps.Phenomenological philosophy offers a rich terminology to describe the spatial dimension of Renaissance maps, how they articulate political meanings, as well as how maps as objects relate to the spaces that contain them (a book, a corridor, a cabinet). It also provides a broad theoretical and rigorous framework to address the relations between maps and the subjects that perceive them, be they mapmakers, patrons, viewers, or modern historians. As a theory of knowledge that describes experience subjectively (that is, from the point of view of the subject) and ex-ternally (that is, outside of experience itself), the phenomenological standpoint is grounded in two foundational notions: the intentionality between subject and object (that is, the cognitive relation between subject and object) and the embodied subject (that is, the indissoluble connection between mind and body).4 Discussed at length in the work of Husserl, Merleau Ponty, and Heidegger, these notions and their related phenomenological problems have been influential in historical and art historical studies, although they have been rarely applied to the experience of making and viewing Renaissance maps.5 Intentionality and the embodiment

4 For an introduction to the phenomenological standpoint see Robert Sokolowsky, Introduction to Phenomenology, Cambridge/UK 1999; Dermot Moran, Introduction to Phenomenology, London 2000; Tim Mooney and Dermot Moran (eds.), The Phenomenological Reader, London 2002; Maurice Merleau-Ponty, The Phenomenology of Perception, London 2002 (first French edition: Paris 1945); Maurice Merleau-Ponty, The Primacy of Perception and Other Essays on Phenomenological Psychology, the Philosophy of Art, History and Politics, ed. by James M. Edie, Everston/IL 1964; Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Aesthetics Reader. Philosophy and Painting, ed. by Galen A. Johnson, Evanston 1993; Edward S. Casey, Representing Place. Landscape Painting and Maps, Minneapolis/MI 2002, is the only major study that applies the phenomenological standpoint to cartography. Casey’s work is discussed below.

5 Among the most compelling application of the phenomenological standpoint to art history the following should be mentioned: David Freedberg, The Power of Images. Studies in the History and Theory of Response, Chicago 1989; Barbara M. Stafford, Visual Analogy. Consciousness as the Art of Connecting, Cambridge/MA 1999; Alex Pott, The Sculptural Imagination. Figurative, Modernist, Minimalist, New Haven – London 2000; David Rosand, Drawing Acts. Studies in Graphic Expression and Representation, Cambridge/UK 2002; David Summers, Real Spaces. World Art History and the Rise of Western Modernism, London 2003; Barbara M. Stafford, Echo Objects. The Cognitive Work of Images, Chicago 2007; Paul Crowther, Phenomenology of the Visual Arts (even the Frame), Stanford/CA 2009.

129

Fig. 2: Egnazio Danti, Flaminia, c.1580, fresco (Gallery of Maps, Vatican Palace).

of the subject, however, may be particularly helpful to a history of cartography interested in the spatial dimension of maps.In the course of the 20th century phenomenological problems developed in many different ways, but generally an experience is regarded as an intentional act of consciousness that is directed towards an object, or a phenomenon, which can be an artifact, a text, a mathematical entity, a memory, an emotion, an imagined object, other subjects or social conventions. In a phenomenological approach it is recognized that the way in which things appear is part of their own being. Thus the intentionality between subject and object is specifically addressed, as is how they relate to each other in specific moments in time and space and in defined cultural contexts. The notion of intentionality can be rigorously applied to the understanding of the correlation between an artifact and its maker, including a map and a mapmaker. As both Heidegger and Merleau-Ponty fully recognized,

130 Persönlicher AutorInnen-Beleg © 2013 Chronos Verlag, Zürich

art – and cartography, one might add – is a phenomenological investigation of the world in its own right, for art discloses the truth of things as that truth is given to the artist (or to the mapmaker) in a culturally defined context. The artifact (a work of art or a map) is the way it is because of the intentionality of its maker and it bears physical traces of its own being made. Thus, it is possible to infer from the work itself traces of its own making, its intended use, and its function, as art historian Michael Baxandall has shown.6 The phenomenological standpoint complements Baxandall’s inferential criticism, providing a rigorous framework in which to correlate artifact to intentionality, first to the intentionality of the artist, but then also to the intentionality of viewers, users, and historians. In this respect, intentionality is a helpful notion, especially in the analysis of artifacts, including maps, which were meant to serve specific purposes for specific subjects, but for which no external documentation survived. A fundamental condition of the correlation between subject and object is the embodiment of the subject, who moves in space and experiences emotions. The body and its physicality – top/bottom, left/right, front/back but also touch, senses, and the wiring of the brain – define the subjective experience of the world, how things are given to a subject as well as how the subject moves in space and reacts to things. For the study of Renaissance maps, revealing is the phenomenological place within which the embodied subject moves. Defined in the works of Husserl, Merleau-Ponty, and Heidegger, place has been recently submitted to a rigorous analysis by the philosopher Edward Casey who, in a series of three books, studied the experience of place as an intentional act of consciousness, just as others have analyzed different acts of consciousness directed towards different phenomena.7 Phenomenological space is not the abstract, infinite, and dimensionless entity of Kantian philosophy, but rather a finite and limited one. Like Kantian space, place is one of the conditions of our being in the world but, unlike Kantian space, it maintains some elements of corporeality and refers to an individual locale with its unique characteristics. In this respect, place also differs from site, which “is a place reduced to location and position in space.”8 A site is thus a place that is mapped

6 Michael Baxandall, Patterns of Intention. On the Historical Interpretation of Pictures, New Haven – London 1985.

7 The first book, Edward S. Casey, Getting Back Into Place. Toward a Renewed Understanding of the Place-World, Bloomington 1993, is a perceptive analysis of the pervasiveness of place in our everyday lives; as Casey himself explained, place specifies “its power to direct and stabilize us, to memorialize and identify us, to tell us who and what we are in terms of where we are (as well as where we are not)” (p. xv). The second book, Edward S. Casey, The Fate of Place. A Philosophical History, Berkeley – Los Angeles 1997, uncovers the history of place in western and non-western philosophy from Plato to today. The third book, Edward S. Casey, Representing Place. Landscape Painting and Maps, Minneapolis 2002, specifically relates the notion of place to landscape painting and cartography.

8 Casey, Representing Place (as in fn. 7), p. 353.

131

on a mathematical grid and deprived of its individual characteristics. Place instead is social and inhabited by subjects. These subjects explain the world from differ-ent points of view, which they cannot share with others, although they do share norms of behavior, customs, and rules of a place. Place, therefore is corporeal, intersubjective, social, and culturally defined. In Casey’s analysis place pertains to landscape painting while space and site pertain to mapping. But it is worthwhile to consider these three notions – space, place and site – simultaneously in relation to cartography. In Renaissance maps, such as Danti’s ‘Flaminia’, a locale is not only positioned mathematically on the cartographic grid but also described with a plethora of qualitative details. The cartographic grid, mathematical and quantitative, establishes the univocal cor-respondence between sites on the globe of the earth and sites on the surface of the map. The grid also measures incorporeal space, since it entails a disembodied viewer with no fixed place on the map and no fixed viewpoint. But the carto-graphic grid coexists with the perspectival views of mountains, cities, and people, which instead are qualitative, descriptive, and corporeal: The viewer has acquired a fixed place, a point of view from which to measure distances, judge directions, and evaluate sizes. These other features of the map extend the representation of the site as location to the site as place. The map responds to the double, divergent, but not incompatible view of a mathematical space and a highly qualified place. What might look to our modern eye as an unresolved combination of different systems of representation and modes of description was in fact a more encom-passing representation of space: bodiless and corporeal, absolute and limited, quantitative and qualitative.It is this notion of place that makes it possible to account for the expanded no-tion of the geographical description of Renaissance maps, a description that does not only include the mathematical location of a place, as Ptolemy had suggested, but also whatever that place contains, namely people, animals, plants, rocks, and vestiges of the ancient past, as Pliny, Strabo, and Mela had narrated. In the selective cultural process that determines what to include and what to omit in a cartographic image, it is this notion of place that clarifies why maps became such uncontested protagonists of political iconography in Renaissance Europe.In his map ‘Flaminia’, then a papal province, Danti was able to record accurately the geographical position of fortresses, villas, bridges, and water springs. He marked the benefices that the Camera Apostolica owned in the territory, the status of feudal properties, and the network of bishoprics and archbishoprics. As a visual aid to the administration of this papal province, the map represented borders, taxation systems, and ownership, which required accurate positioning, but it also merged the spatial distribution of papal resources and ecclesiastical hierarchy with the representation of landscape, the depiction of historical events relevant to the affirmation of papal

132 Persönlicher AutorInnen-Beleg © 2013 Chronos Verlag, Zürich

authority, and the descriptions of ancient and modern writers. In short, the specific cartographic language of the map, coupled with its physical surface as an artifact and its distinct texture as a mural, contributed to the efficacy of this all-encompassing representation of papal dominion.Similarly, in his map of Russia, a land still relatively unknown to 16th-century Europeans, Ortelius updated the geography of the region according to the recent voyage of the English traveler Anthony Jenkinson who, in 1557, searched for a trading route from Moscow to Persia and China. This route was an old fixation of European merchants and an obsession of English and Dutch traders trying to catch up with the Portuguese and Spanish trade in the East Indies. Ortelius revised the location of some mythical places, such as the Mountains of Hyperborea, which Ptolemy had placed in Russia, but kept other classical features such as the land of the Amazons, which he still firmly located according to Strabo. He singled out the Tartars for their non-western habits, representing their dwellings – tents and carriages – in out-of-scale vignettes on his map, and recorded in inscriptions their scandalous familial habits, such as the fact that men could not have concubines but their women were encouraged to have lovers who were called ‘helpers in procrea-tion’ (aiutatori alla generatione). Ortelius’s map resonated with the imagination of European readers, who fantasized about the richness of Russian products and the stellar gains derived from a possible northern trading route, while reassuring them of their right to dominion and exploitation of non-western people. If the notion of place illuminates the construction of political and economic enti-ties – real and imaginary – then equally fundamental to the language of Renais-sance maps is the way through which we experience place. In phenomenological philosophy the primary mediator between place and the embodied subject is the mundane activity of walking.9 By walking a coherent world is built up out of the fragmentary appearances that, taken in isolated groupings, would be merely kalei-doscopic. These appearances are both familiar and unfamiliar, near and unknown but, brought together by the basic action of walking, they make a subject feel as a coherent organism. In maps, partial, fragmentary, and contradictory views of places and people reconcile, indeed transform, into a coherent, perceptible totality – be it the Russian land, a papal region, or the earth itself. As the primary means for expe-riencing place, walking is also a foundational act for its representation, knowledge, and possession. To dominate a place is to walk over it, literally or imaginatively. Indeed, the activity of walking through a place is implied in the spatial configuration of every cartographic image, Renaissance or otherwise. The represented territory, whether large or small, is mapped by imagining the viewer walking through its roads, mountains, and places. In two-dimensional maps, the bodily movement of walking through the mapped territory is either reduced to the movement of a finger on the

9 On walking see Casey, Representing Place (as in fn. 7), pp. 227–230, 300–320.

133

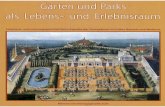

surface of the map, or further limited to the movement of the eyes over the image. Exploring the map means, in most cases, equating the actual movement of fingers and eyes to the imagined movement of the entire body. In some cases, such as the Gallery of Maps in the Vatican Palace, the experience is made vivid and concrete by actually walking through the architectural spaces, in which the maps are displayed (Fig. 3).10 In the Vatican corridor the illusion of the three-dimensionality of the earth is enhanced by the display of the maps them-selves in a specific architectural space: The walk along the corridor reveals that the maps have been arranged as they would appear in an imaginary walk along the Apennine spine of the Italian peninsula. The maps progress from north to south, depicting the regions of Italy from above. The regional maps on the corridor’s walls are subtly adjusted in their orientation to the imaginary trip from north to south. The maps on the left, which represent the regions along the Adriatic Sea, depict north on top, as was customary in Renaissance maps, whereas the maps on the right, which represent regions along the Tyrrhenian Sea, show north at

10 This interpretation of the Gallery of Maps in the Vatican Palace is fully presented in Fiorani, Marvel (as in fn. 1), pp. 171–252. For a complete set of illustrations of the Gallery of Maps and bibliographical information on each map and image see Gambi/Pinelli, Galleria (as in fn. 3).

Fig. 3: Vatican Palace, Gallery of Maps, c. 1580.

134 Persönlicher AutorInnen-Beleg © 2013 Chronos Verlag, Zürich

the bottom, so that the orientation of the maps is defined not by cartographic conventions but by the projected movement along the corridor and the Apennine spine. Not only are the maps inextricably connected to their original location, but they were also conceived, ordered, and displayed in relation to that physical place. Viewers are meant to enter the corridor and literally walk into the assem-blage of maps. The three-dimensionality of the architectural space represented the three-dimensionality of the earth itself, so that the representation of the earth acquired a spatial dimension not afforded in two-dimensional maps. In contrast to the comprehension of two-dimensional maps, the cognitive function of the body in this corridor is not only mediated through the metonymical movement of eyes and fingers on the surface of the map, but it is also enhanced by the actual movement of walking through the real architectural space occupied by the maps as objects. The movement of walking along the corridor mimics the movement of the entire body through the world. Conversely, the different parts of the map cycle are organized not only in relation to each other, but also in relation to the viewer’s body and its position.More importantly, only by walking along the corridor is it possible to grasp the full political meaning of the maps, which is built on connections and analogies, primarily visual analogies, that are not spelled out in books or inscriptions, but are made possible, indeed encouraged, by the very layout and display of the maps themselves. Only by walking through the maps and the corridor that contains them is it possible to grasp how the construction of meanings is achieved through the intermingling of maps and other images of history, mythology, zoology, botany, and religion. The experience of the place facilitates the understanding of the intentionality that correlates maps with artist, patron, and viewers. As view-ers, we bring to the experience of the corridor our knowledge of earlier maps, Renaissance culture, science, art, politics, and much more. We apply to the maps a full array of interpretative tools, inserting them within artistic traditions, pictorial conventions, artistic genres, and period labels. As cultural historians we also know that the broad cultural context shaped the representation of political structures, national borders, trading routes, settlements, religious organization, economic resources, history, and devotion. But only the joint consideration of mapped places and architectural space makes it possible to explain why the Gallery of Maps looks the way it does, why and how meanings are constructed by intermingling an unprecedented cartographic rendition of places in Italy with other images, for the benefit of a papal patron in a defined cultural context. The analysis of place in the Gallery of Maps contributes also to traditional histori-cal concerns, such as the identification of the inventor of this iconography or, to say in phenomenological terminology, the intentionality between the Vatican map murals and their maker. While a contextual study would reveal that the mapped

135

places offered a cartographic rendition of Italy that did not previously exist – the Gallery of Maps was after all a cartographic enterprise – the joint analysis of context and place reveals that the very idea of adapting the geography of Italy to the three-dimensional space of the corridor could come only to a mapmaker trained in the visual arts.11 Similarly, the analysis of mapped places within their spatial context helps to retrieve the perspective of contemporary viewers. If the first enthusiastic viewer of the Gallery of Maps was its patron, Pope Gregory XIII, who – sources tell us – enjoyed contemplating his Church of Italy while literally walking on its Apennine spine, others were called to participate and identify with the papal walk, as if they were overseeing papal possessions and sharing, at least for the brief moments of the visit to the corridor, the papal triumphalistic view of church history. Whatever their belief and creed, they were called to activate and relate to this imagined entity as if it were a reality. Educated members of the papal court would not have failed to realize that the painted maps through which they were walking were inextricably connected to episodes of church history painted on the ceiling. Those well-informed of the politics and diplomacy of the post-Tridentine papacy would have also understood that the Gallery of Maps triumphantly represented the privileged place of Italy, its cities, and islands within the universal church of the early modern papacy. Clergymen would have also understood the relation between map murals and the 24 sacrificial scenes taken from the books of Genesis, Exodus, and Leviticus on the ceiling. Our modern, untrained eye makes no sense of them but they are yet another instance of papal dominion on the peninsula. Connected to the maps of Italy, these biblical sacrifices suggest that the Vatican corridor mapped the geographical boundaries of the lands where ecclesiastical revenues were largely collected. Although the papal claim for the sacramental tithe to sustain the clergy was universal, it was in Italy rather than in the larger Catholic world that the pope collected it. Finally, from this consideration of place also the wide-ranging intertextuality of the corridor emerges, which interacts not only with the generic discourse of do-minion and power, which is inherent in the very act of mapping (the possession of the land through walking and representation), but it also specifically interacts with and transforms famous books dedicated to mapping, such as Ptolemy, Strabo and Mela’s geographical texts, Flavio Biondo’s antiquarian pamphlets, Leandro Alberti’s chorography of Italy, Carlo Sigonio and Cesare Baronio’s history of the

11 On the inventor of the original iconography of the Gallery of Maps see Fiorani, Marvel (as in fn. 1), pp. 182–187; for a different interpretation see Antonio Pinelli, Sopra la terra, il cielo. Geografia, storia, e teologia. Il programma iconografico della volta, in: Gambi/Pinelli, Galleria (as in fn. 3), vol. 1, pp. 125–153.

136 Persönlicher AutorInnen-Beleg © 2013 Chronos Verlag, Zürich

church, and the Bible itself.12 An original cartographic enterprise in its own right, the Gallery of Maps represented the boundaries of the western church that had more readily submitted to papal ecclesiastical authority by integrating places with local history and antiquarianism. In the cartography of this imagined ecclesiastical unit, the representation of bishops’ sees, feudal properties, and church history were elements to define the representation of geographical coordinates and landscape. Similar considerations are pertinent to Renaissance printed maps, such as the map ‘Russia et Moscovia’ included by Ortelius in his original book, ‘Theatrum orbis terrarum’ (Antwerp, 1570), which is usually regarded as the first modern atlas but which is also a pillar of European expansion and superiority. For this pathbreaking book Ortelius chose the traditional title for 16th-century compendia, suggesting that the book was an encyclopedic, albeit brief, description of the entire world.13 In Ortelius’s ‘Theatrum’ the borders of nations and states are sparsely marked but the map book is equally imbued with political meaning, albeit one that was meant to appeal to a wide European audience. Page after page, readers across Europe moved from the general to the particular, from the map of the world to the maps of continents and regions. In so doing, they followed the order of the

12 The sources cited in the text are the following (all references are to the first printed edition): Ptolemy, Cosmographia, Bologna 1477; Strabo, Geographia, Venice 1472; Pomponius Mela, Cosmographia, Milan 1471; Flavio Biondo, Roma restaurata et Italia illustrata, Rome 1453; Leandro Alberti, Descrittione di tutta l’Italia / isole pertinenti ad essa, Bologna 1577 (1st edition in Italian); Carlo Sigonio, De regno Italiae, Venice 1574; Cesare Baronio, Annales ecclesiastici, 12 vols., Cologne 1624.

13 The bibliography on Abraham Ortelius’s ‘Theatrum orbis terrarum’ is extensive, but special attention should be given to the following studies: Cornelius Koeman, The History of Abraham Ortelius and his Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, New York 1964; Karrow, Mapmakers (as in fn. 2); James R. Akerman, From Books with Maps to Books as Maps. The Editor in the Creation of the Atlas Idea, in: Joan Winearls (ed.), Editing Early and Historical Atlases, Papers given at the Twenty-Ninth Annual Conference on Editorial Problems, University of Toronto, 5–6 November 1993, Toronto – Buffalo – London 1995, pp. 3–48; James R. Akerman, Atlas, Birth of a Title, in: Marcel Watelet (ed.), The Mercator Atlas of Europe. Facsimile Edition of the Maps by Gerard Mercator Contained in the Atlas of Europe, circa 1570–1572, Pleasant Hill/OR 1998, pp. 15–29; Marcel van den Broecke, Peter van der Krogt and Peter Meurer (eds.), Abraham Ortelius and the First Atlas. Essays Commemorating the Quadricentennial of his Death, 1598–1998, Utrecht 1998; Giorgio Mangani, Il mondo di Abramo Ortelius. Misticismo, geografia e collezionismo nel Rinascimento dei Paesi Bassi, Modena 1998; Walter S. Melion, Ad ductum itineris et dispositionem mansionum ostendendam. Meditation, Vocation, and Sacred History in Abraham Ortelius’s Parergon, in: The Journal of the Walters Art Gallery 57 (1999), pp. 49–72. On the theme of the ‘theater of the world’ see Walter J. Ong, S.J., Ramus and the Decay of Dialogue. From the Art of Discourse to the Art of Reason, Cambridge 1958; Ann Blair, The Theater of Nature. Jean Bodin and Renaissance Science, Princeton 1997. On the political implications of Ortelius’s ‘Theatrum’ see Walter D. Mignolo, The Darker Side of the Renaissance. Literacy, Territoriality and Colonization, Ann Arbor 1995, pp. 219–334; John M. Headley, The Europeanization of the World. On the Origins of Human Rights and Democracy, Princeton 2007, part 1; Elisabeth Neumann, Imagining European Community on the Title Page of Ortelius’s ‘Theatrum Orbis Terrarum’ (1570), in: Word and Image 25, 4 (2009), pp. 427–442.

137

world according to the continents that Ptolemy had established in the first century and that Ortelius had adapted to the enlarged globe of the 16th century. And they complemented the viewing of maps with the reading of brief descriptions printed on the back of the maps.

But the experience of Ortelius’s atlas and the understanding of its political mean-ing was guided by the map that Ortelius had placed at the very beginning of his volume: an unbroken panorama of the earth from America to Asia offered to the human eye from a point of view that no one, not even God, could enjoy from the heavens (Fig. 4). The globe was divided into two hemispheres: one, at the center, representing Europe and Africa and the other, divided into two crescents attached to the sides, representing Asia and America. Even though in Ortelius’s ‘Map of the World’ locations are rendered primarily as sites rather than places, his world map is unequivocal in its message of dominion, a fact that becomes clear once we recall the origin of his image of the globe. In 1507, the Florentine Francesco Rosselli published a small copper engraving in Venice, possibly in relation to a pocket edition of Ptolemy’s ‘Geography’, which

Fig. 4: Abraham Ortelius, World Map (‘Typus orbis terrarum’), in: Abraham Ortelius, Theatrum orbis terrarum, Antwerp 1570, plate 1.

138 Persönlicher AutorInnen-Beleg © 2013 Chronos Verlag, Zürich

was never realized (Fig. 5).14 Based on the Ptolemaic cartographic grid, the map recorded modern discoveries approximately but aimed to reach a wide interna-tional public, as suggested by its Latin inscriptions. As illuminator, engraver and the owner of a successful print shop in Florence, Francesco Rosselli created for his panoramic view of the world a new oval projection that minimized lateral distortions and based it on heterogeneous sources: modern travel reports, ancient texts, and religious writings. It is this new projection that Ortelius later adopted. A masterful synthesis of conflicting opinions and claims for expansion is the label that Rosselli used to identify the West Indies, “The Holy Land of the Cross or the New World” (Terra Sancta Crucis sive Mondus Novus). The traveler Pedro Alvares Cabral, who landed in Brazil in 1500, had named it “Land of the Cross” (Terra Crucis). Cabral’s patron, King Manuel of Portugal, added the adjective “Holy” (Santa), while the alternative name “New World” (Mundus Novus) re-ferred to the title of Amerigo Vespucci’s printed travel report of 1505, in which he had suggested that Brazil was located in a different continent. Rosselli’s am-bivalence about the status of the West Indies appears throughout the map. Unable to decide whether the West Indies were in Asia, as Columbus believed, or in a different continent, as Vespucci suggested, he combined both options in his map: He accepted Vespucci’s name Mundus Novus, but he also labeled places in Asia with the names that Columbus had assigned to the new lands he had discovered, which were in the new continent but which Columbus believed throughout his life were located in Asia. Finally, in this newly discovered land, Rosselli placed four large rivers, which perhaps represent schematically the large rivers of South America but which, in their symmetrical convergence, recall too closely the four rivers of Paradise. Indeed, having lost a place in the old world, Paradise seems to have been relocated in the newly discovered one.In 1561, the Piemontese Giacomo Gastaldi adopted Rosselli’s oval projection for his ‘Cosmographia universalis’ (Venice, 1561), a magnificent nine-sheet woodcut representing the earth’s globe (Fig. 6).15 At the top of the map, portraits of Strabo and Ptolemy stand symbolically for mathematical and descriptive geography, the two branches of ancient geography that were reunited in Renaissance maps, while

14 On Francesco Rosselli’s world map see David Woodward, Starting with the Map. The Rosselli Map of the World, ca. 1508, in: David Woodward, Catherine Delano-Smith and Cordell D. K. Yee (eds.), Approaches and Challenges in a Worldwide History of Cartography, Barcelona 2001, pp. 71–90; Suzanne Boorsch, The Case of Francesco Rosselli as the Engraver of Berlinghieri’s Geographia, in: Imago Mundi 56, 2 (2004), pp. 152–169.

15 On Giacomo Gastaldi’s ‘Cosmographia universalis’ (Venice, 1561) see Rodney Shirley, The Mapping of the World. Early Printed World Maps, 1472–1700, London 1983, pp. 122 f.; Karrow, Mapmakers (as in fn. 2), pp. 240 f. Gastaldi’s world map is known only through a 17th-century reprint, now at the British Library, London, but the booklet that accompanied it survives in numerous copies.

139

personifications of cosmography and astronomy hold their respective instruments, an armillary sphere and a globe (Fig. 7). Terrestrial globes and celestial charts adorn the corners, relating geography to cosmography. Gastaldi ordered this cosmographical representation of the world around the city of Venice, which was represented by an allegorical personification and the lion of St. Mark, the symbol of the city’s patron saint. Compiled from a multitude of published and unpublished sources, the map was made available to the large public coasts and islands mapped by Portuguese and Spanish sailors, relating them to ancient geographical knowledge. Gastaldi filled the world map with a plethora of qualitative details. Philip II’s imperial ship crosses the Atlantic, marking Spanish ownership of Atlantic routes (Fig. 8), while the Strait of Anian, a fictional sea passage between Asia and Africa, is prominently displayed for the first time (it will reappear in numerous maps).Legends, cartouches, and inscriptions inform the viewer of the main geographic features of the mapped territory, the coordinates of its major cities, the main riv-ers and lakes, the mountain chains, and the flat lands as well as the ethnography and history of people, their habits and beliefs, and the look of their dwellings and their costumes. These descriptive elements are represented at a larger scale than the mapped territory and are represented in perspective rather than in or-thographic view.

Fig. 5: Francesco Rosselli, World Map, 1507, handpainted engraving (Greenwich, National Maritime Museum, G201. 1/53A).

140 Persönlicher AutorInnen-Beleg © 2013 Chronos Verlag, Zürich

Fig.

6: G

iaco

mo

Gas

tald

i, W

orld

Map

(‘C

osm

ogra

phia

uni

vers

alis’

), 17

thc

entu

ry r

epri

nt o

f the

ori

gina

l map

pub

lishe

d in

156

1 (L

ondo

n,

The

Bri

tish

Lib

rary

, Map

s C.1

8.n.

1).

141

Fig. 7: Detail of fig. 6.

The process at the core of Renaissance mapping was untidy, contradictory, and yet captivating. Rosselli’s oval map of the world, celebrating the potential conquest of the globe, indeed making it graspable and recognizable by representing it as a unity within a new oval projection, was geographically updated by Gastaldi in his ‘Cosmographia universalis’, but he subsumed the world under the aegis and influence of Venice. Ortelius instead surrounded the same oval map with neo-stoic quotations pondering on the insignificance of territorial conquests in front of the vastness of the universe.The maps I examined differ in terms of purpose, medium, context, and technique, but nonetheless share a hybrid language that combines the representation of places and sites, mathematics and humanism. The maps themselves were a phenomenological investigation of the world: The mapmaker intended places by walking, measuring, and observing them, and he recorded them in a cartographic image, which became, for him and for others, an interpretation of the world, or of its parts, that did not exist before. Like modern mapmakers, Renaissance cartographers knew well that their maps resulted from the myriad selections they operated in deciding what to include and what to omit. They knew that the Ptolemaic grid reduced the globe to a

142 Persönlicher AutorInnen-Beleg © 2013 Chronos Verlag, Zürich

Fig. 8: Detail of fig. 6.

sequence of sites. And yet they never abandoned the wish for an encompassing rep-resentation of the globe, a representation that combined sites with places, toponymy with history, geography with mythology, plants with animals, people with cities, beliefs, and customs. Maps provided a structure to make sense of the variety of people and things that populate the earth’s globe, indeed a conceptual and visual system to organize the experience of the world. Such an encompassing description of the world resonated deeply with the articulation of political aspirations, be they those of a republic, a monarch, or, more generally, European readers. Because of their language, maps were uniquely suitable for the construction of political pos-sessions, transforming fragments and parts into a graspable totality, and making visible dominions that emerged from contradictory aims and contested aspirations.

![Schlesische Ritterburgen des späten Mittelalters und frühen Neuzeit im Lichte der archäologischen Quellen, [w:] F. Biermann, T. Kersting, A. Klamt (red.), Soziale Gruppen und Gesellschaftsstrukturen](https://static.fdokumen.com/doc/165x107/632068d518429976e406313b/schlesische-ritterburgen-des-spaeten-mittelalters-und-fruehen-neuzeit-im-lichte.jpg)