PEST MANAGEMENT PRACTICES OF COTTON GROWERS IN GUNTUR DISTRICT - AN EXPLORATIVE STUDY

Transcript of PEST MANAGEMENT PRACTICES OF COTTON GROWERS IN GUNTUR DISTRICT - AN EXPLORATIVE STUDY

PEST MANAGEMENT PRACTICES OF COTTON GROWERS INGUNTUR DISTRICT - AN EXPLORATIVE STUDY

M.Srinivasa Reddy

PESTICIDES USE-THE LARGER DILEMMA

Use of chemical pesticides and insecticides are the main

component of pest and disease management practices. But heavy and

unscientific dosages of chemical pesticides and application

practices seriously affect the ecological and environmental

balance. Pesticide usages also cause irreparable damage to human

beings, either directly or indirectly. Seepage of heavy pesticide

residues into water and soil makes the water polluted and soil

diseased. Pollution makes the water un-potable, lowers fish

production and contaminates the food. The effluents discharged by

the pesticide manufacturing plants also get into the ‘food

chain’.

In Indian context, food commodities, for these reasons, right

from wheat and rice to milk and milk-products are found to

contain high levels of pesticide residues of DDT, BHC, Diledrin

and Malathion. On an average an Indian’s body has the highest DDT

levels in the world varying from 12.8 to 3.1 PPM. Further, WHO

Centre for Economic and Social Studies, N.O. Campus, Begumpet, Hyderabad-500016. I indeed thankful to prof. V. Reddappa Reddy for his valuable comments and suggestions.

has graded most of the pesticides used by Indian farmers as

hazardous (Ravi and Thimmaiah 1999:51). It was also established

that, usage of hazardous pesticides leads to asthma and skin

disorders, enlargement of liver, psychological problems and to

some extent, even degeneration of nerves, often resulting in

paralysis. It was further reported that pesticides poisoning is

causing large casualties (Parvinder 1997:50).

Apart from human dimension, the pesticides have also persisted

and accumulated in the environment and have harmed or

contaminated numerous animals or plants, not intended to be

targets (Charles 1976:44). Excessive use of chemical pesticides

is also resulting in resistance development, sudden resurgence of

target pests and induced outbreak of secondary pests. In fact,

the number of insect pests, resistant to insecticides, has shot

up from 12 in 1950 to more than 500 in 1990 (Ravi and Thimmaiah

1995:51). Worse still, the insect species turned resistant to the

pesticides. And, the same species need far more powerful

chemicals now to destroy them (Parvinder 1997:51). Pesticides

have not only killed the pests but also a host of natural

predators that normally keep the pests in check. Thus, by a

strange connivance, pesticides actually made it easier for the

pests to survive by destroying the opposition. Not only that,

pesticides use cannot be expected to give better harvest for

several years, and growing unwanted side effects may out- weigh

the positive results, as happened in Europe in early 70s (Ravi

2

and Thimmaiah 1995:51). If the problems of pest application are

such multi-faceted and destructive, does it rally worth

continuing the heavy pesticide application.

THE PROBLEM

Cotton is not only highly ‘pest attractive’ but also ‘pest

sensitive’. There fore, pest management has been an important

functional component of cotton farming. In fact, of the total

pesticides used farming, cotton alone accounts for 52-55 per cent

in Andhra Pradesh (Ravi and Thimmaiah 1995:50), indicating a

larger share of the total input cost. It was estimated that, the

plant protection alone accounts for 70 per cent of the total cost

of cotton cultivation (AICC 1989). Another estimate is that, the

cost of pesticides and labour charges in pesticide application to

about 40 per cent of total cost of cultivation (DAIC 1990: IV).

Which means, cotton cultivation has been capital intensive. Then,

Indian farmers being in usual debt trap, the capital requirements

of cotton cultivation are to be met with newer borrowings. But

cotton raising has become highly risky proposition, particularly,

owing to heavy pest problem. And, the pest menace has been

reported at regular intervals. One such instance plunges the

farmers family into an un-recoupable debt trap. And, the recent

multiple suicides of cotton farmers in south India reflect that.

To avoid such a devastation, economically available and ‘ less-

pesticide-intensive’ cultural methods are to be adopted. To

3

adopts such cultural practices, farmers must be well informed in

identifying different pests and diseases, understanding the

impact of each of one of them, knowledge of ‘Economic Threshold

Levels’ (ETLS) of different pests, cost benefit analysis of

pesticide application and application of right pesticide in right

dosage and at right time schedules. If farmers are not well

informed of these issues, that leads, normally, to either un-use

or under-use or over-use or mis-use of pesticides.

It is in this context, the present paper tries to assess the

knowledge of farmers in ‘less-pesticide-intensive’ methods. And,

whether are they adopting such methods. Adoption of ‘Integrated

Pest Management’ (IPM) on cotton was considered to be the ‘less –

pesticide-intensive’ method. The present paper tries to

understand, how far away the farmers are, in practice, from the

suggested ‘less –pesticide-intensive’ i.e. IPM methods.

INTEGRATED PEST MANAGEMENT EXPLAINED

Continuous pest problem on cotton crop between 1984 and 1988, has

broken the back-bone of agriculture of Gunter district. While

assessing the problem, Deputy Governor of Reserve Bank of India

and his team has enlisted six important reasons for the crisis in

the district. They are mono-cropping, excessive use of

nitrogenious fertilizers, indiscriminate use of synthetic

pyrethroids, use of sub-lethal doses and mixing of two or more

4

chemicals, improper coverage of spray fluid on the crop and use

of ineffective appliances. Based on this Report, Department of

Agriculture, Government of Andhra Pradesh has involved cotton

growers, scientists, extension staff and pesticide traders and

evolved an adaptable strategy. This strategy was allowed during

1988, 1989 and 1990 (DAIR 1990).

Subsequently, IPM practices were promoted, since 1990, to

minimize the usage of chemical pesticides, reduce the cost of

pesticide application, involving non-chemical component in pest

control and reduce the pollution levels. the IPM is a “pest

management system that in the context of the associated

environment and the population dynamics of the pest species,

utilizes all suitable techniques and methods in an compatible

manner as possible and maintains the pest population at levels

below those causing economic injury” (DPPQ&S:1). The IPM evolved

into a serious of activities. ‘Growing healthy crops, visiting

crops in fields regularly, under-standing biological control

agents and the agro-eco system and making farmers IPM experts’

are recognized as the main components of the programme (Peter E

1995:44).

OBJECTIVES

It is almost eight years since IPM was introduced. This time is

sufficient to understand different aspects of IPM by farmers.

More over, training centres are functioning to train the farmers.

5

It is time to review the programme and, if need be, to make

modifications. A study of this nature is expected to help here.

A centrally sponsored ‘intensive Cotton Development Programme’

(ICDP) was lunched on the basis of 75- 25 contribution between

Centre and State since 1992-93 (DOA Guntur 1995:85-90). A major

component of this is the pest management with minimum chemical

use. Impact of such programme needs an assessment.

The present paper aims at analyzing the pest management practices

of cotton growers in Guntur district with the following

objectives; 1) To examine the knowledge levels of farmers on IPM,

2) to assess the rate of adoption of IPM in pest management

practices, and 3) to understand the gap between the pest

management practices recommended in IPM and the field adopted

practices.

METHODOLOGY

The study was conducted in a cotton prominent village, Vemavaram,

in Guntur district. The village was selected by following a

simple random method. A sample of hundred cotton growers was

selected from the village, again by following simple random

sampling. A schedules was canvassed to get necessary information.

6

The sample represents various castes and farm size categories.

Nearly 78 per cent of the sample respondents are literate. As

many as 72 per cent are owner cultivators and the rest tenants.

Twenty per cent are landless and 21 per cent have more than 10

acres of land. The tenants and small and marginal farmers are

mostly from Scheduled Castes and Tribes. The value of average

household and other assets owned by the respondent household was

Rs. 20,520. The average income per household was Rs. 15,615. The

land, household assets and income are distributed in fovour of

forward castes. The debts were more among forward caste

respondents as compared others.

The data and information was gathered on farming practices

staring from tilling of the land to harvesting of the crop. The

relevant areas covered are pest management methods adopted

through out the crop growth. To collect information, farmers are

mostly interviewed on the fileds using live specimens of pests

and insecticides. Farmers are also taken to the deceased plants.

In cases of need, both insects and affected plants are taken to

the farmers’ households for identification of insects and related

diseases.

The analysis was done by taking caste as an important factor. The

respondents are classified into four groups, namely, Forward

Caste, Backward Caste, Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes.1

7

We have good number of reasons for conducting the analysis by

taken caste as a factor.

The IPM is knowledge intensive and skill oriented, as could be

seen from the various steps involved in it. Any issue which is

knowledge intensive and skill oriented can hardly be scale and

caste neutral. Further, it must be remembered that, caste and

class go together, more or less, in rural India. Caste and class

hierarchy determines, emphatically, the access to knowledge and

resources. This access allows few to use modern agro-technology

profitably.

When IPM is knowledge intensive, it demands fair level of

literacy. And, the level of literacy was better among the upper

castes as compared to Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes. The

learning capacity at and advanced age was also more pronounced

among upper caste learners as compared to others. Which means,

the IPM programme particulars could be more easily conveyed to

upper caste farmers as compared to all other caste groups.

Apart from literacy, social awareness and functional education

are the important factors that decide the rate of adoption of

IPM. However, as is the case of literacy, social awareness is

also influenced by caste of the learners. It was observed that,

the forward caste learners achieved fair scores in social

awareness when compared to Scheduled Caste. Scheduled Tribes and

8

backward castes. The relationship between caste of the learners

and level of functionality also indicated that the forward caste

learners achieved fair scores, when compared to other caste

groups (Govindappa 1977).

While assessing the pest management practices, the chronological

order of crop growth are taken into account in the analysis, i.e.

from the stage of land preparation to crop harvesting. The IPM

practices suggested are taken as recommended practices. Any

deviation from these practices indicate the gap between the

optimum and adopted practices. The analysis was done under four

sections. Section-I deals with land preparation, seed treatment,

inter-cropping, crop rotation and contiguity of crop raising.

Section-II analysis the pest management practices to control

insects during the early stages of crop growth. Between early and

boll formation stages, eight different pests cause serious damage

to the cotton crop. Important aspects of these pest problems are

dealt in Section-III. Boll warms are the dangerous pests during

final stages of the crop growth. Major management practices in

their control are dealt in Section-IV.

SECTION – 1

LAND PREPARATION

Any serious attempt in pest management has to start from land

preparatory stage, and proposed land should be made pest free

before sowing. To achieve this, three important steps are

9

necessary. Firstly, any crop residues of the previous season left

on the field are to be removed. Cotton crop residues like stalk,

bolls, flowers and leaves of the previous season may contain

pests and diseases. Such residues in field help the completion of

life cycle of pests and insects and their multiplication. If the

crop residues of last year are completely removed and destroyed,

the pest impact can be reduced. Second aspect here is deep

ploughing of proposed land during summer. Normally, harvesting of

cotton crop ends during April every year. Deep ploughing of soils

immediately after the harvest has few significant advantages. It

exposes the pest residues of previous season, including

nematodes, to hot sun and also controls weed growth. Thirdly,

removal of pest friendly weeds is important. Uncontrolled weeds

during post-harvest period become the hosts fro pests and help

their survival. As a result, the next fresh crop raised in the

field attracts pests along with sprouting, since pest residues

are already living on the weeds. The control of weeds either by

deep ploughing or manual removal or by application of weedicides

during post-harvest season and pre-sowing days is necessary to

break the continuity of pest life in the lands. Table – 1 depicts

the practices adopted by sample households in land preparation.

Deep ploughing during summer was done only by 29 per cent of

the respondents. Adoption of this practice was more

pronounced among forward caste respondents as compared to

others.

10

A major problem in adopting deep ploughing, during summer,

seems to be owner ship of the land. About 75.0 per cent of

the Scheduled Caste, 80.0 per cent of backward caste

respondents are tenants. In the absence of legal agreement,

the tenancy ceases by the end of each crop season. Hence,

tenants evinced little interest in taking up tilling work

during summer. Further, by the time the tenancy agreement is

arrived for new crop, the sowing season (rainy season)was

already there. As a consequence deep ploughing was not done.

Removal of the crop residues was taken up by only 45.0 per

cent and it was more among forward castes as compared to

others. The forward castes complain of labour shortage for

residue removal. Tenants are not sure of tenancy for next

year , hence, they care a little for the removal of the

residues. Further, as already told, the unwritten tenancy

agreements are arrived only at the neck of the season and

the rush for immediate sowing comes in the way of removal of

the crop residues.

Pre-sowing weed removal was done, either through manual

removal or weedicides application, was done by only 25.0 per

cent of the respondents. All of them are from forward

castes. The important reasons reported for non-application

of weedicides by others were lack of awareness about the

usage of weedicides among poorer sections and financial

problems.

11

SEED TREATMENT

The treatment purifies the seed and protects the crop from seed-

born diseases. Three options are available for farmers with

regard to seed treatment. Certain companies of national base are

supplying crossed, treated and certified seeds. There are few

other small companies of local base that supply locally treated,

but uncertified seeds. Some of the farmers themselves adopt seed

treatment practices. The usage and adoption of seed treatment

practices by the farmers are presented in table 1.

Only 38.0 per cent of the sample households are using

crossed, treated and certified seeds. Nine per cent are

using un crossed , untreated and uncertified seeds. The rest

53.0 per cent are adopting , but , only doubtful and their

own seed treatment practices.

Use of crossed, treated and certified seeds was more

authentic among forward caste farmers as compared to all

others.

INTER – CROPPING

Good sowing practices are expected to minimize the impact of

pests and diseases. The recommended inter-cropping practices

help the multiplication of ‘crop friendly’ insects and

development of pest and insect predators.2

12

However, only 9.0 per cent of the sample farmers have

adopted pulses as an inter-crop along with cotton, and all

of them belong to forward castes.

Only red gram, one of the many pulses suggested, was adopted

as n inter – crop even by this small per cent age.

CROP ROTATION

Mono-cropping or intensive cultivation of cotton causes pest

outbreak easily. Intensive cropping and heavy fertilization

caused severe outbreak of white-fly on cotton during 1985

season, and this problem continued up to 1989 ( Rao 1992:10). A

more remunerative and ecologically suitable cropping system, that

help the balance of insect predators and parasites, was suggested

by their experts (AICC 1989:3). Instead of mono-cropping of

cotton, less preferred crops such as sesame, sorghum, soybean,

maize, groundnut and chilli are suggested as alternate crops

(CICR RS 1990:52). For crop rotation in irrigated tracts, rice,

wheat and jowar are recommended. For rain-fed areas groundnut

and jowar are suggested (cicr rs 1990 :35).

Farmers are enquired to state, since how long they are raising

only cotton, without any interruption, with an alternative crop,

between two crop seasons (TABLE 1)

13

Only 17.0 per cent have taken up cotton cultivation either

on new farms or on farms that had a minimum of ‘one crop

season gap’ (one year) in cotton growing.

About 67 per cent are raising cotton continuously on the

same fields for more than three crop seasons.

Scheduled Caste and tribe farmers are more prone to this

practice of same crop continuity

AVOIDANCE OF CINTIGUOUS COTTON FIELDS

Sowing of contiguous and large tracts of cotton helps the spread

of pest, insect and diseases on to every nook and corner of the

fields. The contiguity may be within own fields of a farmer

and/or neighbours ’ fields too. As such, it is being enquired

that, how many sample farmers have avoided the cotton raising on

contiguous fields (Table 1.)

More than three-fourths of the respondents have their

cotton crop surrounded by cotton itself.

Only 10.0 per cent of the household have no cotton crop

around their cotton fields.

SECTION – II

INSECTS DURING EARLLY STAGES OF THE CROP

14

The insect problem starts on cotton along with the spouting of

baby plant. Among 162 species of insects that are associated with

cotton, about 12 are of major importance, accounting for 50-60

per cent loss in production (CICR RS 1990 :39). However in Guntur

district, , jassids, aphids, thrips, white fly, red spider mite

and mealy bug are the six important insects.

Firstly, farmers must identify the insects, based on either the

features of insects or the features of affected plants. Later

suitable measure are to be adopted for their control. Mis-

identification, if any, leads to the application of unsuitable

insecticides causing to three important problems. (1) Existing

insects will not disappear and may continue to destroy the cop.

(2) Misuse or under use insecticides result in the development of

resisitance in insects, apart from destroying insect predactors,

environment and ecology. (3) The amount of money used on the

control of these insects also go waste. Hence, farmers were asked

to identify insects that cause damage to crops at early stage

(Table 2).

Jassids, aphids, thrips and whitefly are easily identified

by the farmers. There was only a very small number who could

not identify these four insects.

Red spider mire and mealy bugs are the two important insects

not identified by the farmers. In fact, 43.0 per cent are

mis-identified red spider mite and 56.0 mis-identified mealy

15

bugs. The mis-identification was more among Scheduled Caste

and Tribe farmers.

ECONOMIC THRESHOLD LEVELS OF PESTS

The ETL is “that level of pest population which indicates that

control tactics should be used to stop pest numbers from

increasing further, thereby prevent economic losses to the host

crop” (DPPQ&S:1).When the pests and diseases cross the economic

injury level, then only control measures are to be resorted to.

Otherwise, economic cost of pest management would be more, as

compared to the crop loss. Unless farmers are aware of ETLs there

is bound to be over-use of pesticides when not called for, and

under-use when there is a need. The farmers are required to

state the ETLs of five important crops.3

The recommended ETLs seem to be not within the grasp of

farmers. Only 14.0 per cent knew the ETLs for jassids and

aphids. In the case of thrips, white fly and red spider mite

only 10.0 per cent knew the ETLs (Table-3).

PEST CONTROL AND CHEMICAL APPLICATION

16

Suitable chemicals for different pests, timings of application,

their dosages and application practices are recommended by

different agencies.4 In the early stages of crop growth sucking

pests are the major problem. To control them, granule application

in the soils and spraying of chemicals on the crop are suggested

(Rao:32-33). Granule application is the best measure to control

all types of sucking pests at early stages. This will help in

following the ‘cradle to grave’ principle, and pests are killed

before they affect the crop. Knowledge and application are the

two important aspects in granule use. Farmers must have the

knowledge on ‘need for’ and ‘usefulness’ of granule application.

Farmers are enquired to state the need for granule application

their dosage levels, time schedule and actual practices of

granule application (table - 4).

Only 10.0 per cent know the purpose, dosages and time

schedule of the granule application. Even this poor per

centage is mostly represented from forward caste farmers.

Though only 10.0 per cent have the complete knowledge of

application, as many as 30.0 per cent have applied granules.

Less than half of this 30.0 per cent have applied the

granules in correct dosages and time schedule. The rest

have applied, but, neither in correct dosage nor in time

schedule.

Pests like jassids, aphids, thrips and white-fly can be

controlled by applying chemicals of recommended pesticides and

17

insecticides, methods, dosages and timings (Rao 1991: 32-33).

Farmers are enquired to state correct dosages of different

chemicals, time schedule and methods of application of chemicals

(Table - 5).

Only 32.0 per cent have clearly identified the right name

(popular name) of the suitable chemicals. Only 22.0 per

cent have the knowledge about right dosages and time

schedule.

Only 20.0 per cent have applied chemicals in right

dosages, timings and methods.

All other 80.0 per cent applied chemicals, but, some did

not apply the right dosages (48), few did not apply at

right time (20) and few others did not apply in the

method suggested (12). All this indicate the application

of chemicals, but mostly in under dosage, over dosage,

wrong timings, wrong methods and some times even wrong

chemicals.

SECTION – III

PEST PROBLEM DURING GROWING STAGES

Apart from the six insects, referred above, there are eight

more diseases that destroy the crop at a later age. They are

alternaria leaf spot, cercospora leaf spot, helmenthosporium leaf

spot, grey mildew, boll rot, wet weather blight (black arm) and

18

wilt (GCR 1991:39-41). Knowledge of the farmers on these pests

was studied and the results were presented in Table: 6.

More than 80.0 per cent have identified all eight

important diseases, except wilt.

About 50.0 per cent have correctly identified the

symptoms and correct control measures for each of the

seven pests. But in the case of wilt, the knowledge was

poor.

Caste continues to be an important factor in proper

identification of these diseases.

SECTION – IV

CONTROL OF BOLL WORMS

Boll worms create the real and critical pest problem. They

attack the crop, when it is nearer to the harvest. The loss due

to these pests would cost the farmer everything. Every thing in

this context includes, investment over one year on seeds, land

preparation, seeding, weeding, granule and its application,

pesticides and their application, water charges and returns for

the household labour and expected profits on one years’ crop.

The important boll worms on cotton are spotted boll worm,

heliothesis boll worm, spodeptera boll worm and pink boll worm.

19

Features of these boll worms and marks of their identification,

impact of the boll worms, chemicals for their control, dosages of

their control, and time schedules of chemical application are

provided by experts (Rao 1994:37 and GCR 1990:39-41). The

knowledge of farmers on different boll worms, their impact and

control measures adopted by farmers are presented in Table – 7.

All the respondents have identified the spotted boll

worm. As many as 74.0 per cent have correctly described

the impact of this worm. No less than 65.0 per cent has

correctly explained the control measures. All the

respondents have applied chemicals to control the worm.

Compared to the above encouraging picture, only 49.0 per

cent applied correct chemicals. The rest 51.0 per cent

applied, but only lost their money due to the misuse of

chemicals. Over dosage, mixing of more than one chemical

and use of synthetic pyrethroids, that are harmful to

crop growth, are the important problems.

Heliothis boll worm was also identified by all the

respondents. As many as 78.0 per cent have clearly

understood the impact of this worm and 62.0 per cent have

identified correct chemical control measures. In case of

this worm also, over dosage, mixing of more than one

chemical and usage of sythetic pyrethroids was reported.

All the sample identified the spodeptera boll worm, 78.0

per cent correctly explained impact and 67.0 per cent

20

correctly reported the control measures. Only 31.0 per

cent adopted recommended measures for its control. The

rest 69.0 per cent have adopted either overdose, mixing

of two or more chemicals and over usage of synthetic

pyrethroids. In fact, some of them have adopted even all

these three misuses together.

Identification of pink boll worm was done by 81.0 per

cent of the sample, impact was correctly reported by 64.0

per cent and 59.0 per cent knew the right measures of

chemical control. Only 52.0 per cent have adopted the

right control measures and 48.0 per cent have adopted

chemicals of false quantity, mixing and non-suitable

chemicals.

Sample farmers belonging to Scheduled Castes and Tribes

have some knowledge about the boll worms, but chemical

application practices adopted by them are very poor as

compared to others.

POLICY IMPLICATIONS

Based on the results of the study the following policy

implications may be arrived at: (1) Advantages of early tenancy

agreements be brought to the notice of both tenants and

landlords. (2)Alternative employment opportunities to

agricultural labourers are minimized during pre-sowing days, to

facilitate labour availability for crop residue and weed removal.

21

(3) Direct the IPM campaign more vigorously at Scheduled Castes

and Tribes, who matter most as tenants. (4) Economic Threshold

Levels should become part of the farmer’s education in IPM. (5)

Training of farmers on IPM should be field and live specimen

based, while explaining the pests and diseases rather than

training center based. (6) Instead of training farmers about all

the pests and diseases in one package at one time, seasonally in

training be followed at intervals on the need. For example,

training of farmers on deep ploughing summer and on granule

application immediately after the sowings completed.

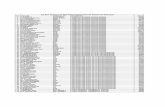

TABLE – 1

PRE-SOWING PRACTICES BY COTTON GROWERS-PEST MANAGEMENTActivity Schedul

edCaste(N =20)

ScheduledTribe(N = 5)

BackwardCaste(N = 25)

ForwardCaste(N =50)

Total(N =100)

22

LAND PREPARATIONRespondents adoptingdeep ploughing duringsummer

3(15.0)

1(20.0)

5(20.0)

20(40.0)

29

Respondents adoptingremoval of cropresidues

6(30.0)

1(20.0)

6(24.0)

32(64.0)

45

Respondents applyingweedicides/removingweeds

- - - 25(50.0)

25

SEED TREATMENTSowing crossed,treated and certifiedseeds

- 1 5 32 38

Sowing treated,uncertified andtruthful labeledseeds

5 2 15 6 28

Seed purchasedlocally, appliedcattle dung to removecoir on the seed andappliedBHC/pesticides

10 2 3 10 25

Seed purchasedlocally and appliedcattle dung to removecoir

5 - 2 2 9

CONTIGUITY OF COTTON FIELDS

All four sides only cotton 18 2 20 37 77

Two or three sides cotton 1 1 2 4 8One side cotton

1 1 1 2 5No cotton around the field - 1 2 7 10

MONO CROPPING

23

Since one season- 1 3 13 17

Since two seasons 2 - 2 12 16

Since 3-4 seasons 10 2 14 25 51Since 5 and above seasons 8 2 6 - 16

TABLE – 2

IDENTIFICATION OF PESTS BY THE SAMPLE FARMERSPest Identification Scheduled

Caste(N = 20)

ScheduledTribe(N = 5)

BackwardCaste

(N = 25)

ForwardCaste

(N = 50)Total

JASSIDS

Identified 17 4 23 50 94Not identified 3 1 2 - 6Mis-identified - - - - -

APHIDSIdentified 19 4 23 50 96Not identified 1 1 2 - 4Mis-identified - - - - -

THRIPSIdentified 17 4 21 50 92Not identified 3 1 4 - 8Mis-identified - - - - -

WHITE FLYIdentified 20 5 25 50 100Not identified - - - - -Mis-identified - - - - -

24

RED SPIDER MITEIdentified - - - 25 25Not identified 6 1 11 14 32Mis-identified 14 4 14 11 43

MEALY BUGIdentified - - 2 26 28Not identified 1 1 2 12 16Mis-identified 19 4 21 12 56

TABLE – 3

NUMBER OF THE RESPONDENTS CORRECTLY IDENTIFIED ETLs OF PESTS

Caste Jassids Aphid Thrips White Fly Red

Spider

MiteScheduledCaste(N = 20) 2 2 - - -

ScheduledTribe(N = 5) - - - - -

BackwardCaste(N = 25)

2 2 - - -

ForwardCaste(N = 50) 10 10 10 10 10

25

TOTAL(N = 100) 14 14 10 10 10

TABLE – 4KNOWLEDGE OF GRANULE APPLICATION AND METHODS OF APPLICATION TO CONTROL PESTS

Knowledge &

Application

ScheduledCaste

(N = 20)

ScheduledTribe(N = 5)

BackwardCaste

(N = 25)

ForwardCaste

(N = 50)Total

(N = 100)

KNOWLEDGE ON GRANULE USE

26

Respondents correctly knowing the need for granule application

- - 2 8 10

Respondents correctly knowing the dosages of granule application

- - 2 8 10

Respondents correctly knowing the time scheduleof granule application

- - 2 8 10

APPLICATION OF GRANULE

Respondents applied the correct quantity and in time schedule

- - 5 7 12

Respondents applied but did not follow the recommended quantity

1

-

1 2 4

Respondents applied but not followed the recommended time schedule

1 - 4 9 14

27

TABLE – 5

KNOWLEDGE AND APPLICATION OF CHEMICALS TO CONTROL INSECTS

Knowledge & Adoption

Scheduled

Caste(N = 20)

ScheduledTribe(N = 5)

Backward

Caste(N =25)

ForwardCaste

(N = 50)Total(N =100)

KNOWLEDGE DETAILS

Respondents correctly knowing the chemicals 3 1 7 21 32

Respondents correctly knowing the dosages 1 - 2 19 22

Respondents correctly knowing the time schedule - - 1 19 20

APPLICATION DETAILS

Respondents applied correct chemicals, dosageand timing

- - 1 19 20

Respondents applied correct chemicals and 11 3 16 18 48

28

dosage

Respondents applied but not in the time schedule suggested

2 1 6 11 20

TABLE – 6

IDENTIFICATION, SYMPTOMS AND CONTROL MEASURES OF VARIOUS DISEASES

Identification ScheduledCaste

(N = 20)

ScheduledTribe(N = 5)

BackwardCaste

(N = 25)

ForwardCaste(N =50)

Total(N =100)

ALTERNARIA LEAF SPOTCorrectly identified by name 15 3 20 45 83Symptoms correctlygiven

10 1 12 30 53

Control measures correctly suggested

10 1 12 30 53

CERCOSPORA LEAF SPOTCorrectly identified by name 15 3 20 45 83

29

Symptoms correctlygiven

10 1 12 30 53

Control measures correctly suggested

10 1 12 30 53

HELMENTHOSPORIUM LEAF SPOTCorrectly identified by name 15 3 20 45 83Symptoms correctlygiven

10 1 12 30 53

Control measures correctly suggested

10 1 12 30 53

GREW MILDOWCorrectly identified by name 13 3 20 48 84Symptoms correctlygiven

9 1 10 30 50

Control measures correctly suggested

7 1 7 25 40

BOLL ROTCorrectly identified by name 13 3 20 45 81Symptoms correctlygiven

9 1 12 30 52

Control measures correctly suggested

7 1 10 29 47

WET WEATHER BLIGHTCorrectly identified by name 13 3 22 45 85Symptoms correctlygiven

9 1 11 39 52

Control measures correctly suggested

7 1 10 29 47

WILTCorrectly identified by name 7 1 13 30 51Symptoms correctlygiven

- - 5 13 18

Control measures correctly suggested

- - - -

-

BACTERIAL BLIGHT

30

Correctly identified by name 17 4 24 43 88Symptoms correctlygiven

10 1 13 29 88

Control measures correctly suggested

7 1 10 22 40

TABLE - 7

IDENTIFICATION OF BOLL WORMS AND ADOPTION OF CONTROL MEASURES

Misuse of chemicals incontrol measures

Caste Identified by Name

Correctly

Impacton crop

correctlyexpressed

Controlmeasurescorrectlyexpressed

Controlmeasurescorrectlyexpressed

Controlmeasures

notcorrectlyadopted

Mixingtwo ormore

chemicals

Usage ofSyntheticPyrethroid

s

Over dosage of recommendedChemicals

SPOTTED BOLL WORMSchedul

edCaste

20 14 12 8 12 12 12 12

Scheduled

Tribe

5 2 1 1 4 3 3 4

Backward Caste

25 19 17 10 15 13 12 15

ForwardCaste

50 39 35 30 20 15 12 20

TOTAL 100 74 65 49 51 43 39 51

HELIOTHIS BOLL WORMSchedul

edCaste

20 15 12 8 12 11 10 10

Scheduled

Tribe

5 3 1 1 4 3 3 3

Backward Caste

25 20 17 12 13 14 19 13

ForwardCaste

50 40 32 27 23 17 40 15

TOTAL 100 78 62 48 52 45 72 41

SPODOPTERA BOLL WORM

31

Scheduled

Caste

20 15 11 8 12 10 11 10

Scheduled

Tribe

5 3 1 1 4 3 4 3

Backward Caste

25 20 16 12 13 14 15 12

ForwardCaste

50 40 39 30 20 16 17 15

TOTAL 100 78 67 51 49 43 47 40

PINK BOLL WORMSchedul

edCaste

15 11 10 8 12 11 8 12

Scheduled

Tribe

3 2 2 1 4 3 2 3

Backward Caste

20 14 12 11 14 14 16 12

ForwardCaste

43 37 35 32 18 17 30 17

TOTAL 81 64 59 52 48 45 56 44

NOTES:

1. This four way classification was followed based on thesegregation of society adopted by Government of AndhraPradesh in adopting its development and welfare measures.The scheduled caste and tribes are very poor by anyreckoning. Backward castes represent a section of theSociety who are poorer as compared to the forward castes,but are above scheduled castes and tribes. Forwardcastes represent a richer section as compared to theother three sections. These castes represent divergenteconomic levels and, as corollary, various investment andexpenditure capabilities. The investment capabilitiesindicates the expenditure on pesticides also. It is forthis reason only, this four way classification wasfollowed. Further, the existing social stratification

32

allows a lower level access to knowledge to scheduledcaste and tribes as compared to forward castes. Thisaccess allows the forward castes for more information onpest and diseases and the management practices. This isexpected to have considerable Impact on the pestmanagement practices of cotton growers.

2. The following reports, referred in this study, havesuggested various inter-crop methods: (1) Manual onIntegrated Pest Management on Cotton, (2) Technology forIncreasing Cotton Production in India, and (3) Cotton

3. ETLs for different diseases are presented in GunturCotton Report – 1990. District Agricultural InformationUnit, Department of Agriculture, Guntur District, p. 26(for jassids: 1 to 2 nymphs per leaf when two middleleaves per plant are observed, aphids: 15 to 20 per centplants infected, thrips: 1 to 2 nymphs adults per leaf,white fly: 5 to 10 flies per leaf when two top leaves andtwo middle leaves are observed and red spider mite: 10mites per square centimetre).

4. The important agencies that are working in these fieldsare: (1) The Central Pest Surveillance Centre, Nizamabad,(2) Andhra Pradesh Agricultural University, Hyderabad andits various affiliated colleges and research centers.(3) Indian Council of Agricultural Research, (4)Central Institute of Cotton Research, Coimbatore, and (5)All Indian Co-ordinated Cotton Improvement Project,Coimbatore.

REFERENCES

AICC (Agricultural Information & Communication Centre), Cotton,Andhra Pradesh Agricultural University, Rajendranagar, Hyderabad.

CICR (Central Institute for Cotton Research), Regional Station,Technology for Increasing Cotton Production in India, All India CoordinatedCotton Improvement Project, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu, 1990.

33

Charles H Southwick, Ecology and the Quality of Our Environment, The JohnHopkins University, New York, 1976.

DOA (Department of Agriculture), Guidelines for Implementation ofC.G.S. Intensive Cotton Development Programme: During 1995-96 inGuntur District, Kharif Crop Production Plan 1995, Guntur District.

DPPQ&S : (Directorate of Plant Protection Quarantine andStorage), Manual on Integrated Pest Management in Cotton, Department ofAgriculture & Cooperation, Ministry of Agriculture, Government ofIndia.

District Agricultural Information Unit, The Guntur Cotton Report -1990, Department of Agriculture, Guntur District.

Govindappa K, Adult Education in Anantapur District : A Study on the Impact ofNational Literacy Mission (Ph.D Thesis submitted to S. K. University,Anantapur, 1994).

Parvinder Chawla, “Tackling Insects Pests”, Science Reporter, June 1997.

Peter E Kenmore etal, “Empowering Farmers: Experiences with Integrated PestManagement”, Agriculture and Rural Development, Vol. 2, No. 2/1995.

Ravi Kumar A and Thimmaiah A, “Pesticides: The Million Dollar Question”, Kurukshetra, May-June 1995.

- 0 - - 0 -

34