Making Markets Work for the Poor: Market-based Approaches to Poverty Alleviation as Institutional...

Transcript of Making Markets Work for the Poor: Market-based Approaches to Poverty Alleviation as Institutional...

Making Markets Work for the Poor:

Market-Based Approaches to Poverty Alleviation as

Institutional Leveraging and Redistribution of Social Control

Kevin McKague

A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies

in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of

Doctor of Philosophy

Graduate Program in Business AdministrationSchulich School of Business

York UniversityToronto, Ontario, Canada

Abstract

Interest in market-based approaches to reduce poverty has grown

substantially in the last decade. To date, however, explanations

in the management literature of how this can be achieved have

focused on viewing the poor as consumers at the base of the

economic pyramid, as microentrepreneurs in need of microfinance

loans, and as potential employees of local small and medium-sized

enterprises. Missing from the core of the management conversation

has been an adequate understanding of the poor as primary

producers and an explanation that situates them within their

broader market and institutional context. Drawing on an in-depth

study of market-based poverty alleviation initiatives for

smallholder farmers by a non-governmental organization in a least

developed economy, this dissertation offers the first theoretical

model to explain the process by which a non-state organization

can strategically enhance market practices in ways that reduce

poverty for poor producers and improve overall market

functioning. Findings suggest that meaningful improvements in

income can be explained by the enhancement of market practices

that redistribute social control toward poor producers in ways that

i

reduce market and government failures. In addition, data revealed

that the effectiveness of market development and poverty

alleviation strategies is moderated by the extent of institutional

leveraging to incentivize market changes in alignment with existing

norms and logics. The model offers an integrated explanation of

how market-based approaches can alleviate poverty and grow

inclusive markets for poor producers. Findings suggest a number

of business implications, including the importance of rebalancing

power relations and enhancing productivity throughout an entire

value chain. In addition, findings contribute to the literatures

on business and poverty alleviation and the literatures on

institutional change.

Epigraphs

“Market society has produced more income, wealth, goods, andservices than any other form of human social organization.”

Neil Fligstein, The Architecture of Markets

ii

“Markets can enable people to lift themselves out of poverty andtransform their lives, but in too many cases the concentration ofpower within markets prevents the benefits of growth from everreaching poor people. Redistributing power in markets at alllevels is essential to making growth work for poor people.”

Duncan Green, From Poverty to Power

“All it would take to eradicate poverty is a 1.3 percent shift inthe global income distribution.”

Aneel Karnani, Fighting Poverty Together

iii

Dedication

To my beloved wife

Rebecca Langstaff

I dedicate this dissertation

To whom much is owed

And to Isaac, Miriam and Bernadette

Their world

iv

Acknowledgements

Many people have made important contributions to bringing

this study and my PhD education to completion. I would first like

to thank my dissertation committee chair, Christine Oliver, for

her intellectual horsepower, mental energy and attention to

detail that she selflessly brought to this research project as

well as her unwavering support for my scholarly and personal

development. I would also like to thank my committee members:

Chris Bell for his enthusiasm and engagement in a promising line

of non-traditional research, and Dirk Matten for his collegial

guidance and feedback attuned to navigating the business of

scholarship in the field of global social issues in management.

Thanks to David Wheeler for creating innumerable

opportunities to pursue common interests together in social and

sustainable enterprise and development with leading researchers,

practitioners and collaborators from Africa, Asia, Latin America,

Europe and North America. Thanks also to Farouk Jiwa for his

skill in connecting people and opportunities and for a tireless

v

commitment to excellence and innovation in market-based

approaches to poverty alleviation. At CARE I would like to thank

Muhammad Siddiquee, Christian Pennotti, Toufique Ahmed, Nick

Southern, Christine Svarer, and Asif Ahmed for their intellectual

curiosity and openness to research collaboration.

The iterative feedback and ongoing support of Schulich

faculty and PhD colleagues helped this research to take shape as

did feedback and encouragement from Samer Abdelnour, Moriah

Meyskens, Lisa Jones-Christensen and Courtenay Sprague. My

dissertation would not have achieved its final form without the

design of the diagrams, editing and formatting by Rebecca

Langstaff as well as the copyediting assistance of Stephanie

Halldorson and Johanna Skelly. The art and rigor with which

Heather Krause applied her deep knowledge of statistical analysis

was invaluable in gleaning insights and answers from the

quantitative data. Financial assistance from the Social Sciences

and Humanities Research Council of Canada, the Ontario Government

and the Schulich School of Business is also gratefully

acknowledged.

vi

I would like to thank my parents for their inspiration,

openness, curiosity and love of the world which has made this

journey possible and enjoyable. And in Bangladesh, I am grateful

for the hundreds of farmers and interviewees from numerous

organizations throughout the dairy sector that generously gave

their time and insights to contribute to this study.

Member of the Jungle Khamar Dairy Producer Group and hisdaughter,

Jungle Khamar, Ullahpara, Sirajganj, Bangladesh

vii

Table of Contents

INTRODUCTION.........................................................1

Research Question and Knowledge Gap.................................2

The Poor as Producers...............................................3

LITERATURE REVIEW....................................................7

Business Approaches to Poverty Alleviation..........................7

Institutional Theory...............................................11

Institutional Change...............................................14

Varieties of Capitalism and Business Systems.......................16

Markets as Institutions............................................18

The Market in Economic Theory......................................19

Market Enhancement in Low-Income Economies.........................22

Views of Market Coordination.......................................24

Ethical Rationale for Poverty Alleviation..........................25

METHOD OF THEORY CONSTRUCTION.......................................28

Theory and Theorizing..............................................28

Qualitative Research Design........................................31Grounded Theory Method..................................................32Case Study..............................................................33Case Selection..........................................................33Single Case Design......................................................36

Empirical Setting..................................................36Bangladesh as a Least Developed Country.................................36Bangladeshi Dairy Sector................................................37Enhancing Market Practices Through a Market-Based Approach..............39

viii

Data Collection....................................................40Interviews..............................................................41Documents...............................................................42Observation.............................................................42Quantitative Data.......................................................44

Qualitative Data Analysis..........................................44Iteration...............................................................44Triangulation...........................................................45Coding..................................................................46Memoing.................................................................48Emergence of Constructs, Relationships and Theory.......................49Closure.................................................................49

Ethical Procedures.................................................49

Validity and Trustworthiness.......................................49

Quantitative Data Analysis.........................................52

FINDINGS............................................................54

How Might Success in Reducing Poverty for Poor Producers Be Explained?.........................................................54

Elements of Social Control.........................................57

Market Practice Enhancements.......................................59Collective Action.......................................................59Participation...........................................................60Capability Enhancement..................................................62Access to Inputs........................................................64Access to Markets.......................................................66Transaction Transparency................................................68

Market Structure Changes...........................................70Increased Productivity..................................................70Restructured Power......................................................71Reduced Information Asymmetries.........................................71Reduced Risk............................................................72

Reduction of Market and Government Failures........................73Market Failures.........................................................73Government Failures.....................................................75

ix

Institutional Leveraging...........................................77Provision of Evidence...................................................80Contextualization of Production Knowledge...............................82Legitimation of Transactions............................................84Expansion of Relationships..............................................87

Learning Strategies of Market Development and Institutionalization.89Needs Assessment........................................................89Performance Measurement.................................................90Continuous Impact Evaluation............................................90

DISCUSSION..........................................................92

Management Implications............................................92

Business Motivations for Inclusion of the Poor in Value Chains.....94

Potential Drawbacks to Market Enhancement..........................95

Theoretical Implications for Market-Based Approaches to Poverty Alleviation........................................................96

Theoretical Implications for Institutional and Market Perspectives105

Limitations.......................................................111

Future Research...................................................112

CONCLUSION.........................................................115

REFERENCES.........................................................117

APPENDICES.........................................................139

APPENDIX A: Bangladesh Dairy Value Chain..........................140

APPENDIX B: Geographic Study Area.................................141

APPENDIX C: Formal Sector Milk Processors.........................143

APPENDIX D: Qualitative Data Sources..............................145

x

APPENDIX E: Quantitative Data Sources.............................148

APPENDIX F: Baseline Survey.......................................192

APPENDIX G: Impact Indicators.....................................196

APPENDIX H: Milk Income and Gender................................197

APPENDIX I: Group Savings.........................................198

APPENDIX J: Milk Income and Knowledge.............................199

APPENDIX K: Milk Income and Access To Inputs......................200

APPENDIX L: Milk Income and Access To Markets.....................201

APPENDIX M: Evidence of Institutional Leveraging..................202

APPENDIX N: Performance Measurement...............................204

xi

INTRODUCTION

Markets and organizations are social innovations that have

created unprecedented wealth where the practices underpinning

them have taken root. As Fligstein (2001: 3) has noted, “Market

society has produced more income, wealth, goods, and services

than any other form of human social organization.” However, the

benefits of markets and wealth creation are not evenly

distributed, many have been left out, and calls for more

inclusive markets and business models are on the rise (Bruton,

2010; Pearce, 2005; Porter & Kramer, 2011; World Economic Forum,

2009). The typical path of market development has been for

functional nation-states to combine market forces with effective

government policy to coordinate the creation and distribution of

value (Hall, 2010). But what of contexts where markets fail and

states are unable to coordinate inclusive market development,

such as in rural areas of least developed economies where poverty

is most acute? In his book The Bottom Billion, Paul Collier (2007)

separates the world’s poor into those who are fortunate enough to

live in countries that respond to traditional approaches to

market development and the reduction of poverty and those who

1

live in countries where such approaches have failed. Despite

enormous investment to reduce global poverty in recent decades,

the number of people living on under $2 per day has increased in

every region of the world except China in the last 30 years, and

currently stands at 2.6 billion or 38 percent of the world’s

population (Karnani, 2011). Poverty severely constrains people’s

ability to afford basic human needs, participate effectively in

society and pursue a life that they value (Sen, 1999). Seventy

percent of the world’s poor live in rural areas where subsistence

methods of agricultural production and exchange persist, with

limited connections to larger national or global economies

despite the increasing price of, and demand for, food (Chen,

Ravallion & Sangraula, 2007; IFAD, 2011). Smallholder farming and

other primary production activities are by far the most prevalent

sources of income for working-age individuals earning under $2

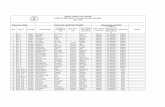

per day, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Primary Occupation of the World’s Poor

2

Source: Adapted from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, Financial Services for the Poor Strategy Overview, November 2010, based on data from the United Nations andthe World Bank.

Research Question and Knowledge Gap

To allow the power of markets to create wealth and reduce

poverty in bottom billion economies, market practices need to be

introduced and institutionalized, even in the absence of

government willingness or ability to do so. Surprisingly, given

studies on poor producers in development studies and

anthropology, little attention in the management literature has

been paid to how non-state organizations contribute to market

development and poverty alleviation in least developed country

contexts among poor producers. Weak states, characterized by

3

institutional voids, lack of support for market institutions,

market failures and widespread poverty are characteristic of

least-developed countries where poverty alleviation is most

challenging (Mair & Marti, 2009; Khanna & Palepu, 2005). Thus, my

research question: How is an organization able to enhance market

practices to make markets work for poor primary producers in

least developed countries?

The Poor as Producers

By poor producers, I mean individuals with incomes under $2

per day engaged in the “primary sector” (Fisher, 1939) of the

economy who make direct use of natural resources including land

for agricultural production of livestock and crops. National

economies can be divided into sectors roughly corresponding to

their relative distance from raw materials, with the primary

sector directly engaged in farming, fishing, herding and other

primary production activities, the secondary sector comprised of

manufacturing, processing and the creation of finished goods and

the tertiary sector consisting of services. Very few individuals

are categorized as primary producers in developed economies

4

whereas in least developed countries primary producers often

account for the majority of the population. Poor primary

producers include the 610 million smallholder farmers and 80

million fishermen and pastoralists who collectively comprise the

largest segment of the working age population earning under $2

per day (see Figure 1). Importantly, I believe that a close

empirical analysis of the poor as producers might provide answers

to some of the challenging problems of strategic implementation

that business, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and other

organizations encounter in attempting to succeed by doing

business with the poor in low income economies.

Although a handful of studies on poor producers from a

market-based perspective are beginning to emerge, few have

studied the phenomena in depth from a theoretical perspective.

Ramachandran, Pant and Pani (2012: 50) produced a typology of

three substantive outcomes – access to market, access to

organization and access to ecosystem – which they found important

for the relationship between low-income handloom artisans and a

major retailing organization in India, but called for more

research on “how the value generated from such economic exchanges

5

is shared.” London, Anupindi and Sheth (2010) identified a model

of constraints to value creation and capture faced by poor

producers and the ventures that aim to serve them. The stream of

literature on subsistence marketplaces has also made important

contributions to understanding “individual, communal, and

cultural factors that influence consumers and entrepreneurs who

live at or near subsistence,” adding insights on consumer

literacy, entrepreneurial literacy and buyer and seller behavior

at the micro-level of economic transactions (Viswanathan & Rosa,

2010: 535). Karnani (2011), in addition to his primary focus on

the provision of employment to reduce poverty, has recognized the

importance of making markets more efficient for poor producers.

Peredo and Chrisman (2006) identify determinants, characteristics

and consequences of community-based enterprise. However, none of

these studies offer a broader explanatory model of the mechanisms

by which market interventions by an organization lead to the

reduction of poverty for poor producers.

Outside the management discipline, the literature on rural

development has described market-oriented poverty alleviation

initiatives by NGOs and other organizations through an inclusive

6

or pro-poor value chain approach (Altenburg, 2007; Humphrey &

Navas-Alemán, 2010; Munir, Ansari & Gregg, 2010). This value

chain approach provides guidance for “understanding how poor

people in rural areas of developing countries can engage, or

improve their terms of engagement with, domestic, regional or

international trade” (Mitchell, Keane & Coles, 2009: iv). This

approach has its roots in Porter’s (1985) emphasis on the

importance of understanding how value is created and distributed

at each step of a product’s transformation and exchange both

inside and outside a firm. A related stream of research on fair

trade has similarly focused on equitable social and economic

relations between developed country consumers and developing

country producers (Moore, 2004; Reynolds, 2000). A value chain

approach focusing on improving market opportunities and practices

for poor producers has been increasingly adopted by multilateral

organizations such as FAO (2012), ILO (Herr & Muzira, 2009) and

UNIDO (2011), major donors such as the Bill and Melinda Gates

Foundation, USAID (2012), DFID (2008), and IDRC (Kaplinsky &

Morris, 2001), and companies such as Unilever (Clay, 2005),

SABMiller (2011) and SC Johnson. The structure and enhancement of

7

a value chain for agricultural products, for example, determine

how value is created and distributed at each point in the chain.

As a result of its practical orientation, much of the literature

on the inclusive and pro-poor value chain approach to poverty

alleviation focuses less on overarching theory and more on

guidance for field workers (Kaplinsky & Morris, 2001; McVay &

Snelgrove, 2008), typologies of strategies for value chain

upgrading (Kaplinsky & Morris, 2001; Mitchell, Keane & Coles,

2009), or evaluations of existing value chain interventions

(Mitchell & Coles, 2011) and remains a field where further theory

development would be welcomed (Altenburg, 2007). My contribution

in this direction is a theoretical explanation of market

enhancement with particular attention to the uneven power

relationships embedded in value chains and the role of a focal

organization as a catalyst for increasing the power of poor

producers. I also seek to add new insight to our understanding of

institutional change by examining how institutional change may be

effected in a resource-constrained environment in ways not

explained by the current institutional literature (DiMaggio and

Powell, 1991; Greenwood, Oliver, Sahlin & Suddaby, 2008; Scott,

8

2008). In particular, I am interested in shining light on one of

the central questions of institutional change, namely the

“paradox of embedded agency” (Battilana, Leca and Boxenbaum,

2009) which asks how it is possible for actors to change the

institutional contexts within which they are constrained and

conditioned (Seo & Creed, 2002).

My work seeks to address these gaps in our understanding of

how market initiatives – at the level of execution – lead to

durable increases in income among poor producers in least

developed country contexts. I examine this gap through the in-

depth study of an NGO, CARE Bangladesh, which has succeeded in

improving the incomes of subsistence-level farmers in the

Bangladeshi dairy sector. CARE has been working in Bangladesh

since 1955 on improving the lives of the extreme poor and

marginalized and currently serves over one million beneficiaries

in the country annually. I chose an NGO as a suitable and

appropriate organization for this study because the innovations

of market-based NGOs have been successfully adopted by for-profit

companies as well as hybrid social purpose businesses and other

NGOs (Chesbrough, Ahern, Finn & Guerraz, 2006; Mendoza and

9

Thelen, 2008; Teegen, Doh, & Vachani, 2004). To anticipate the

results, I found that poverty alleviation for poor producers can

be explained by the redistribution of social control towards the poor in

ways that overcome market and government failures. I argue that

the effectiveness of enhanced market practices is moderated by

the extent of institutional leveraging which positions changes in

market practices relative to existing norms and institutions.

10

LITERATURE REVIEW

In this section I review the literatures relevant to the

interpretation of my results. Reviewed are the literatures on

business and poverty alleviation, institutional theory and

markets as social and economic phenomena. This section concludes

with a discussion of philosophical views of the role of market

coordination in society and the ethical rationale for poverty

alleviation.

Business Approaches to Poverty Alleviation

In the last ten years, the question of how organizations can

contribute to poverty reduction through market-based approaches

has been increasingly explored by management practitioners and

researchers. As a result, diverse streams of enquiry have emerged

exploring different aspects of the phenomena at different levels

of analysis with different focal organizations. This work has

included studies of subsistence marketplaces (Rosa & Viswanathan,

2007; Sridharan & Viswanathan, 2008; Viswanathan & Rosa, 2010),

cross-sector partnerships for poverty alleviation (Rivera-Santos,

11

Rufin & Kolk, 2012; Dahan et al., 2010; London & Anupindi, 2011;

Oetzel & Doh, 2009; Brugman & Prahalad, 2007; Perez-Aleman &

Sandilands, 2008; Kolk, van Tulder & Kostwinder, 2008),

community-based enterprise (Peredo & Chrisman, 2006), social

entrepreneurship focused on poverty alleviation (Seelos & Mair,

2005; Robinson, Mair & Hockerts, 2009), social business (Yunus,

2007; Humberg, 2011), sustainable local enterprise networks

(Wheeler, et al., 2005), inclusive markets (Mendoza & Thelen,

2008) and inclusive business models (Gradl, C. & Knobloch, 2010;

Gradl, Krämer & Amadigi, 2010; Jackman and Breeze, 2010). In

addition to, and substantially overlapping with, these streams of

enquiry, three main approaches have been the most prominent in

the current management conversation on business and poverty

alleviation: the base-of-the-pyramid (BoP) approach, the

microfinance approach and the small and medium sized enterprise

(SME) employment approach.

The base (or bottom) of the pyramid approach popularized the

conversation on business and development into the management

literature by offering a business case for multinationals to view

the poor as an untapped and potentially profitable market

12

opportunity (Prahalad & Hart, 2002; Prahalad, 2005). The core

logic of the base-of-the-pyramid approach is that poverty can be

reduced by companies profitably selling goods and services to the

poor in ways that are more affordable and accessible than

alternative market offerings. Subsequent research has been

conducted on the capabilities, partnerships and business

processes needed to establish new ventures in low-income markets

(Hart, 2010; London & Hart, 2004, 2010). However, recent work to

understand the causes of a number of failed ventures at the base-

of-the-pyramid suggests that more explicit research is needed to

understand the broader nature of market creation and the

relationship between market practices and poverty alleviation

(Simanis, 2010; Simanis & Hart, 2009). Calls have been made from

within this research stream for greater attention to viewing the

poor as producers given the existing focus on the poor as

consumers (London, Anupindi & Sheth, 2010; Ramachandran, Pant &

Pani, 2012). The base-of-the-pyramid literature has also been

criticized for its underlying libertarian ideology and utopian

optimism that large multinationals should play the leading role

in global poverty reduction (Karnani, 2011). Claims that it

13

romanticizes the poor (Banerjee and Duflo, 2007; Karnani, 2009),

marketizes social welfare at the expense of governments and civil

society organizations (Kamal, Ansari & Gregg, 2010) and generates

non-essential consumer needs rather than genuinely serving

essential needs (Davidson, 2009) have led to concerns that if

unchecked, base-of-the-pyramid strategies may be exploitative and

harmful to the poor (Karnani, 2007). These concerns have led to

searches for alternative approaches.

Microfinance has also become a prominent feature of the

management conversation about poverty alleviation and one of the

most readily cited examples of a market-based approach to

development. Microfinance is now undertaken by numerous NGOs and

commercial financial organizations world-wide, serving over 150

million clients (Roodman, 2012). The logic of microfinance

proposes that the provision of small loans to poor individuals

overcomes capital constraints and allows people to start or grow

a microenterprise business that will allow them to work their way

out of poverty (Yunus, 2003; Robinson, 2001). This logic is

focused on reducing particular market failures – missing credit

markets, the lack of information that lenders may possess about

14

borrowers, the high transaction costs of small loans – and

addressing these with a group-lending approach where loans are

guaranteed by social capital and group joint liability rather

than physical collateral. However, as the microfinance industry

has matured and more rigorous randomized controlled studies have

attempted to concretely establish a link between microfinance

provision and poverty reduction, a more mixed picture has begun

to emerge (Banerjee and Duflo, 2011). Most microfinance loans are

taken for purposes of consumption, rather than growing a

business, and most microenterprise businesses run by the poor

lack the differentiation, economies of scale and capacity to

provide a reliable route above the poverty line (Bateman, 2011).

If microfinance is based on a model of entrepreneurship, it may

be limited in its ability to create scale and reduce poverty for

poor producers with low entrepreneurial capacity, market

information or ability to assume significant additional risks.

The third prominent explanation in the management literature

of how organizations can reduce poverty through a market-based

approach focuses on reducing poverty through employment by local

SMEs (Karnani, 2011). The logic of this approach suggests that

15

poverty can best be reduced by SMEs if they can create employment

opportunities for low-skilled, low-income workers, especially in

least developed countries, because local SMEs are more labor-

intensive, less capital-intensive, more flexible and more

geographically dispersed within a country than large businesses

(Karnani, 2011). At the same time, local SMEs are more productive

and competitive than microenterprises. Aneel Karnani has written

extensively on this approach and has frequently emphasized the

importance of viewing the poor as producers, primarily, but not

exclusively, in order to contrast reducing poverty through SME

employment with other approaches focused on selling goods to the

poor. Karnani most commonly equates being a producer with being a

potential employee, arguing that productive employment is the

solution to poverty reduction. And the best way to create

employment opportunities for the poor, he argues, is through

local SMEs. However, this approach tends to assume that

governments will take up their responsibilities to create a

business-enabling environment for SMEs and work to counteract

market failures and enforce necessary regulations. Unfortunately,

this may be unlikely in many least developed countries where

16

poverty is most severe and where the majority of people living on

under $2 per day are likely to be smallholder farmers.

Taken together, the dominant managerial approaches to

poverty reduction in least- developed countries – the base-of-

the-pyramid approach, microfinance, and the SME employment

approach – primarily emphasize the role of the poor as consumers,

microentrepreneurs, and employees, respectively. Notwithstanding

considerable research in related work on development among the

poor (Bebbington, 1999; Chambers, 1983; Nussbaum, 2011; Scoones,

1998), what is missing from the center of the management

conversation is a model that explains how poverty can be

alleviated for the poor as producers by an organization adopting

a comprehensive market-based approach.

Institutional Theory

Institutional theory has been immensely valuable in

conceptualizing markets and market practices as institutions. In

the context of a least developed country where patterns of

production and exchange are often shaped by social forces such as

tradition, informal rules, and social expectations as well as

17

economic incentives, institutional theory offers helpful insights

into the process of market creation and enhancement.

The origins of new institutional theory in management

studies date from the 1970s. By the mid-1970s, by far the

dominant account of social and organizational behavior in the

management literature was one where rational actors in full

control of their actions strategically and freely chose the most

efficient means to meet instrumental organizational objectives

(Scott, 2008). Then, in the late 1970s and early 1980s, Meyer and

Rowan (1977), Zucker (1977), DiMaggio and Powell (1983) and Meyer

and Scott (1983) successfully introduced an institutional

approach into management theory as a challenge to the dominant

rational agency view.

Institutional theory recognizes the various layers of

meaning and logics that individuals and organizations are

embedded in and draw upon and which shape interests, motivations,

strategies, identities and assumptions about markets and market

practices (Scott, 2008). When market practices and market changes

are seen through an institutional lens, the way in which they

derive their legitimacy is highlighted (Barley & Tolbert 1997;

18

Jepperson & Meyer 1991). Institutions in this sense are not types

of organizations (schools, businesses, hospitals) nor broad

social categories (families, religion, the state) but are the

“more-or-less taken-for-granted repetitive social behavior that

is underpinned by normative systems and cognitive understandings

that give meaning to social exchange and thus enable self-

reproducing social order” (Greenwood, Oliver, Sahlin & Suddaby,

2008: 5). Metaphors and images of institutions include logics,

rule systems, social structures, frameworks, orders, patterns and

templates for action. An institution denotes the logics or rule

systems themselves and institutionalization is the process by

which the logics or rules become established and more or less

taken-for-granted (Jepperson, 1991).

From an institutional perspective, behaviors and practices

have both practical and symbolic content. Activities such as

group meetings, certifications, branding, financial accounts, and

contracts involve both real social relationships, through which

instrumental economic ends are accomplished, as well as a

dimension of symbolism and meaning beyond their instrumental

value (Friedland and Alford, 1991). Relationships and symbolic

19

meanings are mutually constituted as illustrated in Fligstein’s

(2001: 48) definition of institutions as the “rules and shared

meanings… that define social relationships.”

Scott’s (2008: 48) integration of the institutional

literature in organization studies produced his often cited

distinction that institutions are comprised of “regulative,

normative and cultural-cognitive elements that, together with

associated activities and resources, provide stability and

meaning to social life.” Institutions can exist at multiple

levels (individual, group, organization, institutional field,

market, society) and their scope can be narrow (covering the

activities of an individual or group) or broad (covering large

portions of a national or global population) (Barley, 2008;

Greenwood, Oliver, Sahlin & Suddaby, 2008). Within institutional

approaches to explaining behavior, various accounts give

differing emphases on different levels of analyses (from micro to

macro), the importance of regulative, normative and cultural-

cognitive elements of institutions, and the accommodation of

individual agency (DiMaggio & Powell, 1991; Scott, 2008).

20

Institutional practices and behaviors can also vary in their

level of institutionalization. The more an activity is

institutionalized, the greater it takes on rule-like status

(Meyer & Rowan, 1977), the more objective and exterior it is seen

to be (Zucker, 1977), the greater the depth and spread of its

acceptance across space and over time (Barley & Tolbert, 1997)

with the greater chance it will be perpetuated, reproduced and

sustained through taken-for-granted activities whose social

origin is ignored (Jepperson, 1991). Taken-for-granted

institutions are perceived to have no appropriate alternatives

(DiMaggio & Powell, 1991) and have widely shared rationales or

explanations that account for them as functional fixtures of

their environment (Jepperson, 1991). Although in some accounts

institutions have been portrayed as totalizing and monolithic,

more often they are viewed as multiple, fragmented and

overlapping (Friedland and Alford, 1991). These multiple

institutional logics are available for individuals and

organizations to draw upon as bases for action (Friedland &

Alford 1991; Thornton & Ocasio, 2008). Institutions arise, are

maintained, and are challenged through ongoing human interaction

21

(Lawrence & Suddaby, 2006) and are in this sense “collective

enterprises” jointly produced and reproduced through ongoing

action and interaction (Barley, 2008: 496).

In summary, an institutional view of social and economic

phenomena extends beyond reductionist assumptions of rational

actor models and offers a purportedly more nuanced treatment of

individuals, markets and organizations as more than utility-

satisfying production machines (Lawrence, Suddaby & Leca, 2009).

An institutional approach examines how interests, identities and

choices are shaped by social forces in the environment such as

meanings, culture, social rules and beliefs. An institutional

approach highlights the interdependent and mutually constituting

nature of social contexts and individual action (Barley &

Tolbert, 1997; Giddens, 1984).

Within institutional theory are several streams of

literature with potential relevance to market enhancement for

poor producers in a least developed country. These literature

streams on institutional change, varieties of capitalism and

markets as institutions are considered next.

22

Institutional Change

Meyer (2008) argues that the institutional perspective is

much better positioned than other organizational theories to

capture and understand societal changes, such as those associated

with the introduction of new market practices. Greenwood and

Hinings’ (1996) framework for understanding institutional change

considers the processes by which organizations adopt or discard

templates for organizing, but does not focus on how actors change

their institutional context. Similarly, in their study of

professional associations, Greenwood, Suddaby and Hinings (2002)

develop a model of institutional change that focuses on the

stages of change, but not on the work of the actors to change

them. In Barley and Tolbert’s (1997) recursive model of change

based on Giddens (1984) concept of structuration, the authors

acknowledge that actors make conscious choices within the options

offered by their institutional context, but do not elaborate on

how actors identify and carry out the changes they pursue. Seo

and Creed’s (2002) dialectical perspective focuses on how

contradictions within institutional fields open up “reflective

23

shifts” in actor consciousness to motivate change processes, but

does not specify how actors go about achieving them.

Lawrence and Suddaby (2006) introduced the concept of

institutional work to explicitly focus greater theoretical and

empirical attention on how actors create institutions. Lawrence

and Suddaby (2006) define institutional work as “the purposive

action of individuals and organizations aimed at creating,

maintaining and disrupting institutions.” This approach extended

beyond the tendency of institutional entrepreneurship studies to

focus primarily on the creation of new institutions to instead

embrace all aspects of institutional change including how

institutions are disrupted or maintained, as well as created.

Although actors’ embeddedness within the institutionally-defined

logics of their fields is recognized, the emphasis in

institutional work studies is placed on how the practical actions

taken from within their context can change aspects of

institutions around them. In this way, the institutional work

approach “suggests culturally competent actors with strong

practical skills and sensibility who creatively navigate within

their organizational fields” (Lawrence & Suddaby, 2006: 219).

24

The emphasis of the institutional work approach therefore

brings to the fore the actions of organizations and individuals

and positions them within the ongoing recursive interaction

between institutions and action which Seo and Creed (2002: 223)

have called “the mutually constituted nature of structure and

agency.” In this view, institutions are simultaneously sources of

prohibitions and constraint as well as practices which can be

maintained and changed through purposive action (Barley &

Tolbert, 1997; Giddens, 1984). From this perspective,

institutions are not uniform, totalistic, homogeneous and

permanent but are heterogeneous and overlapping, dynamically

competing, conflicting and complementing each other (Friedland &

Alford, 1991).

Although institutional theory has begun to consider the role

of power in various institutional practices and changes, DiMaggio

and Powell (1991: 30) have noted that: “Power and interests have

been slighted topics in organizational analysis.” Where power and

control have been considered more generally, studies often focus

on field-level interventions by powerful central actors (with the

state or professions often playing lead roles) and describe

25

conflicts and competition between institutional practices. Little

work from an institutional perspective has looked at the

processes by which actors work with issues of power or control to

enhance market practices, especially in contexts of market

failure associated with least developed countries.

However, given the promise of the institutional work

approach to contributing to understanding how new market

practices emerge and gain traction, Lawrence, Suddaby and Leca

(2009: 10) emphasize, “relatively little is still known about the

concrete practices employed by actors in relation to

institutions.” Where studies have considered the activities and

work of actors to bring about institutional change and the

adoption of new practices, findings are typically presented in

lists such as Fligstein’s (1997) 15 types of social skills or

Aldrich and Fiol’s (1994) eight entrepreneurial strategies to

promote new industry development. Similarly, Lawrence and Suddaby

(2006) identified 17 forms of institutional work which have

subsequently been reconceptualized into seven categories by

Kraatz (2009) and into three overarching types of institutional

work by Lawrence and Suddaby (2006), with Perkmann and Spicer

26

(2008) proposing modifications. To date, a more theoretical

explanation of how purposive actors change institutions by

introducing new market practices remains underdeveloped. At the

same time, although institutional theory has begun to consider

the role of power in various institutional practices and changes,

very little work from an institutional perspective has applied

issues of power or control to market changes and, more

specifically, in contexts of market failure.

Varieties of Capitalism and Business Systems

Related literatures on varieties of capitalism and business

systems (Hall & Soskice, 2001; Whitley, 1999) also focus on how

organizations adapt to their institutional contexts. However,

whereas institutional theory in organization studies has studied

the diffusion of new practices across organizational fields and

national boundaries, the business systems approach pays special

attention to how the adoption of new practices are influenced by

national institutional frameworks (Tempel & Walgenbach, 2007).

The varieties of capitalism and business systems approach make

comparisons between countries because nation-states play an

27

important formal and informal role in influencing the relative

strength of markets and government coordination within their

borders (Morgan, Campbell, Crouch, Pedersen & Whitley, 2010;

Morgan, Whitley & Moen, 2005). National capitalisms are

structured according to the relative balance of power between

capitalists, workers and governments at the time of entry into

modern industrialization to establish and enforce market

institutions such as property rights, rules of exchange,

governance structures and conceptions of control (Fligstein,

2001). Where organizational institutionalism has traditionally

tended to focus on isomorphism and the convergence of practices

(DiMaggio & Powell, 1983), the business systems approach pays

attention to the continued persistence of differences in

practices across countries (Whitley, 1999). The more the

particular national patterns of economic coordination are closely

integrated with other elements of society, such as educational

systems and social norms, the more that new practices introduced

into that context will be affected and shaped by them (Whitley,

1999). The varieties of capitalism approach also tends to

distinguish between two types of national economic coordination:

28

liberal market economies (such as the United States) and more

coordinated market economies (such as Germany) (Djelic, 1998;

Hall & Soskice, 2001). Most advanced capitalist countries combine

the two to a certain extent; however the particular mix

determines a country’s place on a continuum between the two ideal

types (Hall & Gingerich, 2009). The national business system

approach has been successfully used to explain differences in

corporate social responsibility practices across countries

(Matten & Moon, 2008). However, to date, the business system

approach has tended to focus on developed OECD economies rather

than least developed countries. In addition, some have argued

that the business system approach does not adequately account for

the social and political dimensions of institutional change (Hall

& Thelen, 2009). As Hall and Soskice (2001) indicate, the type of

coordination within a country depends on the institutions within

a country to support them. Where market coordination and

coordination by governments or strong private sector actors are

lacking, such as in least developed country contexts, the task of

initial market coordination may fall to non-state intermediary

actors, an under-explained area in the literature.

29

Markets as Institutions

That markets are socially structured, characterized by

social relationships, and infused with social norms is a starting

point for institutional theory and sociological approaches to

understanding markets (Aspers, 2011; Biggart & Beamish, 2003;

Biggart & Delbridge, 2004; Burt, 1992; Fligstein & Dauter, 2007;

Fourcade, 2007; Granovetter, 1985; Swedberg, 2005; Uzzi, 1997;

Uzzi & Lancaster, 2004). Market norms, practices and

relationships include what and how things are done, the scripts

for price setting, and the rules of exchange, cooperation and

competition (Aspers, 2011). My understanding of markets as

institutions is consistent with Coase’s (1988: 8) definition of a

market as a “social institution which facilitates exchange” and

White’s (2002: xiii) understanding of markets as “interactive

social constructions.” I define markets as “not simply an

allocative mechanism but also an institutionally specific

cultural system for generating and measuring value” (Friedland &

Alford, 1991: 234).

30

With an institutional view, even highly instrumental,

efficiency-focused economic interactions and changes are

“enmeshed in and freighted with” the expectations of social

relationships and pressures (Owen-Smith & Powell, 2008: 603).

From an institutional perspective, it is not possible to fully

understand individual, organizational and market practices

without attention to how they are shaped by social and

institutional forces. An extended quote from Thornton & Ocasio

(2008: 119) with reference to the important work of Fligstein

(1996) further captures the concept of markets as institutions:

While markets are economic structures – they are also institutions. They function because of a set of formal laws and normative expectations about them and these normative expectations have changed through time and space. A market in one historical and cultural context is not the same as a market in another (Fligstein, 1996).

The institutional account of market practices argues that

institutionalized rules and logics become social facts which

shape interests and choices by assigning levels of legitimacy or

appropriateness to various options (Meyer & Rowan, 1977; Zucker,

1977). A widespread and deeply held institutional practice within

31

an area of influence will tend to elicit similar responses

leading to isomorphism or similarity (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983).

The Market in Economic Theory

Modern economic theory usually implicitly assumes the market

to be a price-making and resource-allocating mechanism central to

coordinating production and distribution in society. A frequently

cited economic definition of the market that was prevalent in the

19th century and continues to be referenced today is:

“Economists understand by the term Market, not any particular market place in which things are bought and sold,but the whole region in which buyers and sellers are in suchfree intercourse with one another that the prices of the same goods tend to equality easily and quickly.” Cournot (1838/1927) cited by Marshall (1920/1961) cited by Swedberg (1994: 259).

However, around the end of the nineteenth century,

mainstream economic theory rejected social, historical and more

empirical approaches to understanding markets in favor of the

analytical power that was perceived in the study of abstract

exchange markets that were characterized by having perfect

information and perfect competition (Swedberg, 1994). Although

32

this classic economic view is attractive for its reductionist

simplicity, a more sociological approach to markets cautions that

this elegance comes at too high a cost to adequately explain the

reality of complex market and organizational phenomena as it is

empirically observed and experienced (DiMaggio & Powell, 1991).

Similarly, Aspers (2011) argues that economic theory has been too

reductionist, resulting in a theory that is distorted and focused

on modeling. This explanation may account for observations by a

number of contemporary scholars examining the role of markets in

economic theory. For example, economic historian Douglass North

(1977: 710) has noted a common shortcoming regarding more fully-

developed understandings of the market’s role in the economy and

society, stating “it is a peculiar fact that the literature on

economics… contains so little discussion of the central

institution that underlies neo-classical economics – the market.”

Ronald Coase (1988: 7) has made similar observations, stating

that “Although economists claim to study the market… in modern

economic theory the market itself has an even more shadowy role

than the firm.” Similarly, Biggart and Delbridge (2004: 29) have

observed, “modern economists view the market as a price-setting

33

mechanism and have left its workings implied rather than

explicitly discussed.” Since economics tends to take markets as a

given, it overlooks how market transactions are shaped,

structured and influenced by social and institutional contexts,

norms and expectations. As noted by White (2002: 9): “Because the

market is a tangible social construction opaque to tools familiar

to economists… the market has remained a mystification” from the

perspective of mainstream economics.

Theories of social action, such as those based in economics,

accord explanatory primacy to individuals who are endogenously

motivated by utility-maximizing self-interest. These individuals

make rational choices from a wide range of informed options. This

view leaves unexamined the power of social and institutional

forces in shaping interests, rationality and utility in the first

place. Instead, the motivations for action are assumed to be

universal and ahistorical and aligned with modern economic

society. From the rational economic choice perspective,

unconstrained and unquestioned individual choice is the primary

cause of social arrangements; institutions are merely the sum of

34

individual interactions (DiMaggio & Powell, 1991; Friedland &

Alford, 1991).

Economic theory takes markets as natural phenomena that

emerge spontaneously and order themselves to create equilibrium

as an unintended result of individual self-interest within rules

of law, property and contract (Aspers, 2011). Markets from the

perspective of economic theory are taken for granted “givens”,

(Sarasvathy & Dew, 2005) and therefore a starting point “used to

explain other phenomena rather than considered as objects in need

of explanation” (Aspers, 2011: 40). In this view neither the

state nor organizations participate in the making of markets;

indeed, from the perspective of much economic theory,

intervention by the state or other actors is often seen as

inherently reducing the natural ability of markets to reach

equilibrium.

However, in less developed countries, obstacles to the

“natural” formation of markets have been well documented (Datta-

Chaudhuri, 1990; Stiglitz, 1989) and in developed economies,

market failures resulting in economic recession have led to

greater questioning of the assumptions underlying mainstream

35

economic theory (Stiglitz, 2010). Many national economies exist

with badly distorted productive and distributive efforts

(Heilbroner & Milberg, 2008). So it is unusually striking that

markets – for all of their centrality to the promise and

challenges of current prosperity and future development and their

place at the heart of the discourse on economic development –

remain so relatively under-explained from the view of economics.

This is even more so in a world where social arrangements are

becoming more complex, where economic and ecological crises have

called into question the underlying power of rational choice

market models, where individuals and organizations from

developing and emerging economies with diverse institutional

histories are increasingly playing a role in national and global

markets, and where poverty alleviation through market development

is a high priority for many organizations.

To summarize, although economic perspectives have

contributed important insights to understanding markets, there is

still much to be learned about how they work and how their

functioning is enhanced. I have therefore adopted an

institutional view which is particularly appropriate in

36

understanding markets in the different institutional context of

low-income subsistence marketplaces.

Market Enhancement in Low-Income Economies

The process of market development or market creation refers

to expanding and formalizing a “nascent” but potentially viable

market by institutionalizing market practices. “Nascent markets

constitute unstructured settings with extreme ambiguity…ambiguity

arises from unknown cause-effect relations and lack of recurrent,

institutionalized patterns of relations and actions” (Santos &

Eisenhardt, 2009: 644). Institutionalized beliefs about what is a

viable market define the meaning of acceptable economic exchange

and dictate the extent to which local actors will even entertain

the possibility of market transaction (Oliver, 1996). I share

Biggart and Beamish’s (2003: 448) assumption that

“‘institutionalized’ understandings and arrangements facilitate

economic action by providing agreed-upon, often tacit, ways of

conducting business” and that markets tend to be socially

constructed by those most influenced by and engaged in them.

37

Essential prerequisites for market order are rules governing

what to do and what not to do in the market, encompassing the

beliefs, norms, culture and appropriate practices relating to

production, competition and exchange (Aspers, 2011). Objects of

trade and the rules for exchange of property rights must be

morally legitimate. Market exchange must be voluntary, with

actors getting something in return for that which they give up. A

viable market is one that possesses a product (or service),

demand for and supply of that product and the potential for

efficient exchange. Markets need institutions to enhance trust,

information, certainty, shared cognitive frameworks, rules,

competition and a balance of power. We can also gauge the

viability of a market by what it is not. If the terms of exchange

are involuntary, unclear, and unpredictable or exclude openness

to new market participants, if property rights, transaction

transparency and rule of law are lacking, and if market and price

information is unattainable, too costly or unreliable, these

exchange forums are generally classified as non-viable markets

(Menard, 1995). Nascent markets are characterized by

significantly compromised efficiency between buyers and sellers

38

and low levels of productivity by producers. For a market to

function properly, the institutions underpinning them have to be

created or enhanced. However, as Aspers (2011: 63) reinforces,

“there are few recipes” for the process of market creation.

Questions about the emergence of collective enterprises such as

markets and organizations are generally understudied. Even more

so, insufficient research has been conducted on market creation

or on how intermediary organizations navigate the subtleties of

institutionalized beliefs and values in establishing new markets

in least developed country contexts.

Traditionally, questions about market development have been

focused at the macro level of analysis in the disciplines of

economics, sociology and political science. These approaches have

emphasized the importance of the state in regulating and creating

the enabling environment for markets and how new market practices

emerge as a result of political or regulatory changes (Sarasvathy

& Dew, 2005). The emergence of new market practices has also been

explained by opportunities opening up as a result of new

technologies or scientific discoveries (Fligstein & Dauter,

2007). However, these lines of inquiry have shed little light on

39

the emergence of market practices as a result of organizational

actions in the absence of functioning or effective governments in

some of the least developed countries. My study therefore looks

at how an organization can take action to enhance and develop a

market for the benefit of poor producers.

Views of Market Coordination

In addition to the specific question about organizational-

level approaches to enhancing market practices in a specific

industry, more abstract theoretical questions could be raised

about how the growth of market systems and coordination by market

mechanisms impact a society in broader terms. If smallholder

farmers are transitioning from more traditional subsistence

methods of production and exchange to a more formalized and

efficient market, how are markets (and the assumptions that go

along with them) likely to impact communities and society more

generally? What are the implications of a greater presence of

markets in rural Bangladeshi society?

An evaluation of the moral and cultural implications of

market-based methods of coordination, production and exchange

usually depends on whom a market is seen to benefit and how

40

inequalities are distributed. Longstanding debates about the

positive and negative role of markets in society have been

ongoing for at least the last 300 years (Fourcade & Healy, 2007;

Muller, 2002). Critics of markets emphasize their potential

negative effects such as alienation and exploitation of workers

and producers (Marx, 1867), conspicuous consumption (Veblen,

1899), inequality (Polanyi, 1944) and the fostering of negative

virtues such as greed, self-interest and competitiveness

(Bordieu, 1984). On the other hand, however, equally persuasive

arguments have been put forward for the positive influences of

markets on society such as satisfying individual needs (Smith,

1776), the efficient allocation of resources (Walras, 1874),

nurturing the virtues of honesty, integrity and cooperation

(Smith, 1776), enhancing individual and political freedom (Hayek,

1944) and supporting creativity and innovation (Schumpeter,

1944). Contributing to this longstanding philosophical debate is

beyond the scope of the current study. However, a series of

recent experiments in 15 small-scale societies around the world –

primarily agricultural, fishing and nomadic peoples – found that

the more that markets played a role in their lives, the greater

41

those communities developed a sense of fairness with respect to

their interactions with others (Henrich et al., 2010).

Ethical Rationale for Poverty Alleviation

The ethical rationale for poverty alleviation recognizes

“the essential needs of the world’s poor, to which overriding

priority should be given” (Bruntdland, 1987: 43). The normative

imperative for poverty alleviation rests on a number of ethical

foundations. One foundation is Kant’s (1785/1993: 30) categorical

imperative to: “Act only according to that maxim whereby you can

at the same time will that it should become a universal law.”

This principle calls for the duty that all individuals have as

moral individuals to take action to benefit others as they

themselves would hope to receive assistance if in need. In this

way, Kant’s categorical imperative is consistent with “the golden

rule” principle found in many religions such as Christianity,

Islam, Buddhism, Hinduism, Judaism, Confucianism and First

Nations spirituality amongst others (Crane & Matten, 2010). The

difference between Kant’s categorical imperative and religious

principles is that religion grounds the golden rule in the

42

supreme authority of an ultimate eternal divinity, whereas Kant’s

approach is based on his assumption that humans are capable of

understanding what would be morally right and wrong in a given

situation without recourse to divine authority (Crane & Matten,

2010).

The ethical rationale for poverty alleviation also rests on

Rawls’ (1971: 302) theory of justice, especially as set out in

his second principle to determine if an action can be understood

as just: “Social and economic inequalities are to be arranged so

that they are… to the greatest benefit of the least advantaged.”

Rawls’ theory of justice acknowledges that in a free and

competitive society, inequality can be acceptable as it allows

effort, merit and capability to be compensated and incentivized

given equal opportunities for all, but also ensures that any

inequalities take special consideration to benefit the least

advantaged (Hahn, 2009).

Consistent with Rawls theory of justice, the UN’s Universal

Declaration of Human Rights (1948) enshrines basic fundamental

human rights as “natural rights” (Locke, 1690): unalienable

entitlements that should be upheld and protected in all

43

circumstances. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UN,

1948) states that:

Article 3: Everyone has the right to life, liberty and security of person.Article 22: Everyone, as a member of society, has the right to social security.Article 25: Everyone has the right to a standard of

living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family, including food, clothing,housing and medical care and necessary social services.

The universal rights set forth in the UN declaration set a

global minimum standard which is still not met for most

individuals living in poverty around the world. Approximately 50

percent of the 852 million people in the world who are

chronically hungry and malnourished are smallholder farming

households unable to grow or buy enough food to meet their

family’s nutritional requirements (Sanchez & Swaminathan, 2005).

An additional twenty percent of the hungry are rural landless

households with 10 percent of the hungry being pastoralists and

fishermen. The remaining 20 percent of the hungry live in urban

areas. Hunger, like poverty, is concentrated in rural areas where

subsistence methods of agriculture persist with limited

44

opportunities for increased access to productivity and market

opportunities (IFAD, 2010). Poverty is a multidimensional

concept, encompassing material incomes and assets as well as

social factors such as marginalization, vulnerability,

insecurity, lack of opportunity and disempowerment (Bourguignon &

Chakravarty, 2003). As described by the World Bank:

Poverty is hunger. Poverty is lack of shelter. Poverty is being sick and not being able to see a doctor. Poverty is not being able to go to school and not knowing how to read. Poverty is not having a job, is fear for the future, living one day at a time. Poverty is losing a child to illness brought about by unclean water. Poverty is powerlessness, lack of representation and freedom. (WBCSD 2004: 11).

With the current global reality of over one third of the

world’s people earning under $2 per day and the situation not yet

up to the standards of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights,

from a Kantian perspective this reinforces the duty that all

people have, based on their inherent capabilities for rational

and moral thought, to take action to assist the poor in securing

their basic rights, opportunities and freedoms.

However, to what extent are organizations that are

structured as for-profit companies obligated to create

opportunities to assist the poor in meeting their basic human

45

needs? The preamble to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights

calls on “every organ of society… to promote respect for these

rights and freedoms” thus including private sector organizations.

Indeed, companies may have greater obligations to see that basic

human rights and freedoms are realized for the poor within their

sphere of influence due to their growing power in regions where

poverty is prevalent, growing social expectations on companies to

demonstrate corporate citizenship and sustainability and

instances of governments unable or unwilling to uphold their

obligations to improve the lives of their poorest citizens (Crane

& Matten, 2010; Hahn, 2009; Matten & Crane, 2005).

46

METHOD OF THEORY CONSTRUCTION

Theory and Theorizing

Theories arise from our human need to order and make sense

of our complex world (Dubin, 1969; Weick, 1989). A theory informs

and aids judgement. Theories are developed so we don’t have to

start from scratch in answering questions. A theory answers

questions about how something unfolds (Langley, 1999) or why

something is (Sutton & Staw, 1995). Theories are “the base for

knowledge and understanding of important relationships” and

constructs (Hitt & Smith, 2005a: 1). Theories are explanations.

They help us understand phenomena. Theories explain relationships

and offer meaning, cohesion and stability in the face of

ambiguity (Czarniawska, 1997). Theories create and reflect our

expectations of the world and its myriad phenomena and therefore

provide practical guidelines for thought and action (Van de Ven,

1989). Making a theoretical contribution clarifies or enhances

current explanations and answers to questions. New explanations

that are interesting challenge our conventional ways of thinking

47

and add value to existing ideas (Weick, 1989). Good theory should

allow someone to see the world with new eyes (DiMaggio, 1995).

The occasion for theorizing can be a problem, a gap in

knowledge, an unanswered question, a puzzle, a paradox, a

contradiction, an anomaly, or something that does not make sense

given current assumptions (Weick, 1989). Theories are

“approximations” (Weick, 1995). They are approximations of the

world around us wherever we may fall on the ontological continuum

between believing that an objective external reality is knowable

or believing it is socially constructed (Morgan & Smircich,

1980). Theories are abstractions – the pictures we paint or the

maps we draw to represent the world that we experience from our

particular frame of reference (Burrell & Morgan, 1979).

Although a substantive review of the perspectives of leading

management theorists concluded that “there is a substantial

amount of variation in viewpoints among scholars about what good

theory is and how it should be developed” (Hitt & Smith, 2005b:

587), a number of distinctions have been made. Distinctions can

be drawn between description – answering the question of what is

happening – and explanation – answering the question of how or

48

why something is happening. Most often, description is not

considered the focus of theory (Bacharach, 1989; Sutton & Staw,

1995). However, description can aid in understanding a phenomenon

by reducing it to its component parts (Bernard, 1988) and can

combine with explanation to form a theory (Whetten, 1989). Theory

then provides an answer to how and why the parts fit together and

are interrelated (Miles & Huberman, 1994). Distinctions can also

be made between theorizing at the level of grand theory, such as

the work of Marx, Smith, Darwin or Freud, and theorizing at the

mid-range level which would encompass many of the more modest

theories of management and organizations (Miles & Huberman,

1994).

In organization and management studies, various approaches

to understanding the process of theorizing have been put forward.

Drawing on Weber’s (1949) concept of ideal types, it is possible

to outline two general approaches to theorizing summarized in

Table 1 below.

Table 1: Two Stylized Ideal Types of Approaches to Theorizing

Strategy of Developing Predictions in Closed Systems

Strategy of Developing Generalizations in Open Systems

Source of Distinction

49

Variance Process Mohr, 1982Problem solving Sensemaking Weick, 1989Covering laws Narrative DiMaggio, 1995Analytical Synthetic Werner & Schoepfle, 1987Variable-oriented Case-oriented Ragin, 1987Cause Pattern Weick, 1999Matrix display Network display Miles & Huberman, 1994Deductive Inductive Weick, 1989

Although these two types are necessarily and perhaps overly

simplified, the first column represents what Weick (1989: 518)

describes as “a strategy of developing predictions in

hypothetical or artificial closed systems” with the second column

a “strategy of developing generalizations in open systems through

the use of inductive abstraction.” The first approach is often

associated with testing and confirming existing theory, while the

second can be employed to explore emerging phenomenon and develop

new theory (Miles & Huberman, 1994). Hitt and Smith (2005b)

suggest that the first column may be more suitable for

theoretical concepts that are more easily measured, while the

second column may be more applicable when theoretical concepts

are harder to measure. The second column assumes a world of

complexity and ambiguity. The first column tends to assume a

50

world of pre-existing and universal scientific laws of social

phenomena that represent an independent external reality. The

second column reflects an ontological assumption of reality as

subjectively constructed by individuals engaged in a common

project of interpretation and sensemaking. Although these

generalized ideal types of theory-building can be distinguished,

they are often usefully combined in the theory development

process (DiMaggio, 1995; Miles & Huberman, 1994).

Any theory, however, has to necessarily balance trade-offs

between generalizability, accuracy and simplicity (Weick, 1999).

A theory that satisfies any two of these characteristics is least

able to satisfy the third. And, it may be helpful to note that

theory construction is not the only way to develop new knowledge.

“Thick and rich description, case analysis, bringing about change

in a difficult situation, and telling a story are all valid

reasons for doing research” (Corbin and Strauss, 2008: ix).

Theory can serve multiple purposes including serving as an

intermediate step to another theory (Mintzberg, 2005) or serving

as a generator of debate and discussion (Barney, 2005). Karl

Weick reminds us that theory is a dimension rather than a

51

category – that the more an explanation satisfies the criteria of

a theory, the more it deserves the label (Weick, 1989; 2005).

My motivation for theorizing is to generate concepts and an

explanatory model that can further the conversation about market-

based approaches to poverty alleviation and explain the key

concepts and their interrelationships to advance knowledge in

both organization studies and the practice of management (Simon,

1967; Van de Ven, 1989).

Qualitative Research Design

To answer my research question about how an organization is

able to enhance market practices to make markets work for poor

primary producers in least developed countries, I chose an in-

depth qualitative research design, suitable for understanding

patterns and relationships in complex market settings. Although

the research question focused on the organizational level of

analysis, a qualitative approach allowed a close examination of

interrelationships among actors in the dairy value chain and how

they were embedded within multiple levels of their social,