Literary Evocations of Herculaneum in the Nineteenth Century, in C.C. Mattusch (ed.), Rediscovering...

Transcript of Literary Evocations of Herculaneum in the Nineteenth Century, in C.C. Mattusch (ed.), Rediscovering...

J121

0041

Siz

e: W

:9”X

11”

175L

189No.06

7623C

Literary Evocations of Herculaneum

in the Nineteenth Century

eric m. moormann

C B

M Y

No.005

J121

0041

Siz

e: W

:9”X

11”

175L

191

191 moormann Literary Evocations of Herculaneum in the Nineteenth Century

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Portrait of Joseph-François-Stanislas Maizony de Lauréal, c. 1813, pen and ink

Musée Bonnat, Bayonne

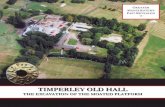

In many aspects Herculaneum must be considered the Cinderella of the ancient sites on the Bay of Naples, and this is true

not only of literary evocations. For many decades both scholarship on and care of the monuments was insufficient, and it is thanks in part to the direction and help of the David and Lucile Packard Foundation that much has changed in a positive way. Luciana Jaco-belli has explained the enormous difference between postherculanensia and postpompei-ana by comparing the excavations of Hercu-laneum, which have a museumlike character, with those of Pompeii, a site that is easily accessible from all sides.1 The first site in Herculaneum to be uncovered in an open-air excavation, the House of Argus, was not excavated until the 1820s (fig. 1). Today Her-culaneum is a crater within the modern town formerly called Resina (since 1969, Ercolano) and can be seen only after a deep descent. In contrast, Pompeii sits and is visible at mod-ern-day ground level, and visitors immedi-ately proceed into the antique realm.

This does not mean that Herculaneum has no Nachleben in literature. The number of references, excluding scholarly texts, is large in the first decades of the state-directed exca-vation history, from 1739 to approximately 1770, but in travel accounts only, whereas poems and fiction speedily tended toward a Pompeii-centric image of the entire Vesuvian area. The mining-like explorations of Hercu-laneum under more than twenty meters of volcanic material were never favorable to mass visits, and at Herculaneum even the few tourists who reached the small township around which were scattered the pleasant Vesuvian villas and the new palace of the Bourbon king at Portici had to exert great effort in obtaining permits to descend into

the galleries cut out by forced labor. More-over, these galleries did not expand during the explorations but remained limited, since the excavators backfilled the areas explored, apart from the theater and its immediate sur-roundings. A few sentences illustrate the dan-gers that had to be surpassed.

In a rarely cited letter published in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, George Knapton (1698 – 1778) wrote to his brother Charles that he had heard from an “old Man, living next Door to the Well” (the access to the excava-tions) that digging had taken place there twenty-seven years before, that is, in 1713. He described his difficulties with the inhabit-ants of Resina:

Having given you some Account of what is taken out of

this subterraneous City, I shall now proceed to what

remains in it, and our Journey down to it. At our coming

to the Well, which is in a small Square, surrounded with

miserable Houses, filled with miserable ugly old Women,

they soon gathered about us wondering what brought us

thither; but when the Men who were with us, broke away

the paltry Machine with which they used to draw up

small Buckets of Water, I thought we should have been

stoned by them: Till, perceiving one more furious than

the rest, whom we found to be Padrona of the Well, by

applying a small Bit of Money to her, we made a shift to

quiet the Tumult. Our having all the Tackle for descend-

ing to seek, gave Time for all the Town to gather round

us, which was very troublesome: For, when any one

offered to go down, he was prevented either by a Wife or

a Mother; so that we were forced to seek a motherless

Batchelor [sic] to go first. It being very difficult for the

First to get in, the Well being very broad at that Part, so

that they were obliged to swing him in, and the People

above making such a Noise, that the Man in the Well

could not be heard, obliged our Company to draw their

Swords, and threaten any who spoke with Death. This

caused a Silence, after which our Guide was soon landed

safe, who pulled us in by the Legs, as we came down.

C B

M Y

No.005

J121

0041

Siz

e: W

:9”X

11”

175L

192

192 rediscovering the ancient world on the bay of naples

The Entrance is 82 Feet from the Top of the Well: It is

large and branches out into many Ways, which they

have cut. We were forced to mark with Chalk, when we

came to any Turning, to prevent losing ourselves. It gives

us a perfect Idea of a City destroyed in that Manner.2

We must keep in mind the difficult lives of the inhabitants of Resina in contrast with those of travelers who had money to spend and wanted help in making the descent for a reasonable price. Moreover, the locals were struck by terror when their husbands or sons went down the shafts like miners. Many of those who did — forced laborers and convicts, since no one worked there voluntarily — had died. But our gentlemen managed to descend the twenty-seven meters.

When King Charles decided to stop the tunnel excavations in the 1760s in favor of the open-air method employed in the excava-tions at Pompeii and its surroundings, Her-culaneum lost its attraction, although there would always be those courageous enough to go down to the theater for a couple of hours. A handful of prose works and many more poems are witness to the fascination for the town that was still, for the most part, hidden under both the volcanic remains and the modern town of Ercolano. I leave out prose texts3 and give a few examples of poems

before focusing on an epic about the destruc-tion of Herculaneum by Joseph-François-Stanislas Maizony de Lauréal. Like Maizony de Lauréal’s L’Héracléade, most of the poems date from the nineteenth century.

Herculaneum in Eighteenth- and Nineteenth-

Century Poetry

In the eighteenth century we find a great number of poems that hail the ancient city of Herculaneum, which had slept for so long and now been awakened by the king of Naples. Praise for the explorations makes it clear that an old civilization hidden under the modern kingdom of Naples can be seen as the foundation of its civilization. No author asks why the Neapolitans had never before attempted to explore these towns on top of which they had lived for centuries. Nor did any writer draw a comparison with Rome, where the study of antiquity had been flourishing from the early Renaissance onward.

Some texts refer to the papyri discovered in the Villa dei Papiri in the 1750s, which were increasingly famous. I single out one example of this genre, Thomas Gisborne’s poem Herculaneum. Gisborne (1758 – 1846) was a country parson and poet who had been educated at St. John’s College, Cam-bridge.4 As far as I know he never traveled to southern Italy. His Latin ode on Hercula-neum was recited in the Senate House at Cambridge in 1777, but I do not know whether it was published in Latin. A good English verse translation or re-elaboration was published in 1833.5 According to this poem, it is thanks to the king of Naples that the ancient city has come to light. Earth must accept that people enter into her to reveal old treasures. An entire city is reemerging, although in silence. It is no longer vivid, but it is apparent that the inhabitants made music and went to the theater. We also see tombs. The poet incorporates the idea, handed down by the historian Dio Cassius, that the Herculaneans were in the theater at the moment of the eruption.6 He suggests that modern visitors may admire wall paint-

1. Ernest François Pierre Hippolyte Breton, House of Argus, Hercula-neum, etching, Pompeia décrite et dessinée (Paris, 1855), plate 9

Author collection

C B

M Y

No.005

J121

0041

Siz

e: W

:9”X

11”

175L

193

193 moormann Literary Evocations of Herculaneum in the Nineteenth Century

ings equal to the lost works of Zeuxis and Parrhasios and expresses hope that the papy-rus rolls will deliver texts by famous poets from antiquity. A few passages may suffice. He begins with the following verses, wonder-ing about the long sleep of the city under the masses of volcanic material:

Herculaneum

Where had thy lingering steps delay’d,

Why distant was thy guardian aid,

Monarch! whom Votaries deem’d divine

At Herculaneum’s holy shrine?

Why to th’ impetuous storm’s career

Didst thou, dread Genius, close thine ear,

And from destruction’s yawning grave

Thy menac’d City fail to save?

Where slept thy giant might, when first

O’er thy lov’d walls the tempest burst;

When first Vesuvius far and wide

Pour’d the red lava’s burning tide,

And earth with fearful shock was rent

Beneath the o’erwhelming element?

The eruption caused the destruction of tem-ples, theaters, and houses regardless of the status of the buildings, but, as a result of the Neapolitans’ explorations, we now possess almost unharmed sculptures, paintings, and papyri. As to the last of these, Gisborne hopes that more texts of the great Latin poets will come to light. He apparently has not the taste for Greek texts that he has for Greek art:

O lead me where the eye may dwell

On forms, by Sculpture’s magic spell

Redeem’d from death; where still can frown,

Enwreath’d with conquest’s laurel crown,

The Chief, whose arms of sinewy mould

The fragment of a rock uphold,

And from the meteors of whose eye

A routed legion seems to fly,

Works of the olden-time we trace,

Relics of Grecian art and grace;

Marble and ivory proclaim

Alike Italian skill and fame.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Nor yet hath envious age defac’d

The breathing forms that Zeuxis trac’d;

Surviving still Time’s awful doom,

The colours of Parrhasius bloom.

Sketch’d on the wall with skilful care,

The pencill’d figure still is there;

Preserving still its glowing hue,

Each faultless limb attracts the view;

Still deck’d in smiles each feature seems,

Still darts the eye its sparkling beams.

And ye, amidst the wreck secur’d,

Too long in darkest night immur’d,

That kindlier fates to light restore,

Hail! sacred mines of classic lore,

Hail, rescued volumes! though the strain

Of Horace lives not here again,

Though vainly may the Muse desire

The thunders of a Virgil’s lyre;

Yet may perchance new Bards arise,

Where Herculaneum buried lies;

Some new Catullus prove his heart

The prey of Love’s envenom’d dart:

There may some new Propertius tell

The wily God’s o’erpowering spell,

And in sweet plaintive measures mourn

The beauteous Nymph’s unbending scorn.

As we will see, these papyri became a source of inspiration for other authors as well, here to be represented by the fictitious papyrus of Maizony de Lauréal.

In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, poetry shows more personal expressions of fascination with the ancient city. Again, I present one example, “September, 1819” by William Wordsworth (1770 – 1850).7 At the age of forty-nine, the poet sees life slowly vanishing. But aging poets no longer have to write about passions, and their verses are all the more enduring. Inspiring examples of eternal fame can be found in antiquity, first of all Alcaeus and Sappho. In the last two stanzas of his poem — the second of a set with the same title — is an allusion to trea-sures possibly hidden in the library of the Villa dei Papiri. Wordsworth shares the eagerness of authors like Johann Joachim Winckelmann to possess great lost poetic texts from antiquity instead of the treatises of the Stoic philosopher Philodemos of Gadara, discovered at the villa:

C B

M Y

No.005

J121

0041

Siz

e: W

:9”X

11”

175L

194

194 rediscovering the ancient world on the bay of naples

September, 1819

Departing summer hath assumed

An aspect tenderly illumed,

The gentlest look of Spring;

That calls from yonder leafy shade

Unfaded, yet prepared to fade,

A timely carolling.

No faint and hesitating trill

Such tribute as to Winter chill

The lonely Redbreast pays!

Clear, loud, and lively is the din,

From social warblers gathering in

Their harvest of sweet lays.

Nor doth the example fail to cheer

Me, conscious that my leaf is sere,

And yellow on the bough: —

Fall, rosy garlands, from my head!

Ye myrtle wreaths, your fragrance shed

Around a younger brow!

Yet will I temperately rejoice;

Wide is the range, and free the choice

Of undiscordant themes;

Which, haply, kindred souls may prize

Not less than vernal ecstasies,

And passion’s feverish dreams.

For deathless powers to verse belong,

And they like Demigods are strong

On whom the Muses smile;

But some their function have disclaimed,

Best pleased with what is aptliest framed

To enervate and defile.

Not such the initiatory strains

Committed to the silent plains

In Britain’s earliest dawn:

Trembled the groves, the stars grew pale,

While all-too-daringly the veil

Of nature was withdrawn!

Nor such the spirit-stirring note

When the live chords Alcaeus smote,

Inflamed by sense of wrong;

Woe! woe to Tyrants! from the lyre

Broke threateningly, in sparkles dire

Of fierce vindictive song.

And not unhallowed was the page

By wingèd Love inscribed, to assuage

The pangs of vain pursuit;

Love listening while the Lesbian Maid

With finest touch of passion swayed

Her own Aeolian lute.

O ye, who patiently explore

The wreck of Herculanean lore,

What rapture! could ye seize

Some Theban fragment, or unroll

One precious, tender-hearted scroll

Of pure Simonides.

That were, indeed, a genuine birth

Of poesy; a bursting forth

Of genius from the dust!

What Horace gloried to behold,

What Maro loved, shall we enfold?

Can haughty Time be just?

I shall only briefly recall the work of the great Italian poet Giacomo Leopardi (1798 – 1837), about whom I have written elsewhere.8 His Paralipomeni della Batraco-miomachia, a sort of continuation of the pseudo-Homeric Batrachomyomachia (war between frogs and mice, but with crabs added to the mix), was written at Torre del Greco and Naples. It was unfinished upon Leopardi’s death, but his friend Antonio Ranieri published it in 1842 in Paris.9 The epyllion describes the realm of the mice under the earth: they have all the elements of a city — palaces, statues, colonnades — but do not need light (III, 2, 6 – 10). Their resi-dence, therefore, is like the hidden treasures at Herculaneum (III, 2, 11 – 14). Underlying this device is a polemic against the Neapoli-tan intelligentsia, in particular because of their inclination to be dreamers (spiritualisti). In the description of the subterranean galler-ies of Topaia (City of Mice), Leopardi seems to recall a visit to Pompeii by night, which in fact was possible with a special permit. The long gallery of the poem may have been the tunnel connecting Naples to Pozzuoli or even, I venture to suggest, the one described in Jacopo Sannazaro’s Arcadia (see below). One may, like Knapton, descend into the ruins under the miserable houses of modern Resina.10 If the monuments had been on Brit-ish or German soil, Herculaneum would have been unearthed extensively like Pompeii. According to him, it is a shameful reflection, not so much on Italy as on those who would exert no efforts to extract these treasures from the earth. Foreigners appreciate Italian culture more than Italians do and understand Italy’s bounty. He briefly refers to the study

C B

M Y

No.005

J121

0041

Siz

e: W

:9”X

11”

175L

195

195 moormann Literary Evocations of Herculaneum in the Nineteenth Century

of the papyri, another point about which we can both laugh and fume. Europe is asking for their contents and Italians are not suffi-ciently concerned about them. Those who study them are accused of satisfying personal vanity rather than a sense of public duty.11

Herculaneum Destroyed

In the following, I concentrate on an exam-ple of a genre that was extremely popular after the discovery of the papyri in Hercula-neum: a hoax manuscript reportedly found in the excavations. This is a curious French epic, L’Héracléade ou Herculanum enseveli sous la lave du Vésuve, poëme de L. A. Flo-rus by Joseph-François-Stanislas Maizony de Lauréal (Paris, 1837). I was unable to find much information about the author, whose portrait was drawn by Jean-Auguste-Domi-nique Ingres in Rome around 1813 (see essay frontispiece).12 He worked for the Napole-onic government in Rome as a sort of solici-tor general and must have known Italy well. It is said that he was the natural son of count André Joseph Abrial, pair de France and active in Lyons under Napoleon. As indi-cated on the title page of L’Héracléade, Maizony was a member of the Accademia Pontaniana in Naples (fig. 2).13

In L’Héracléade Maizony presents the translation of an ancient manuscript pur-portedly found in Naples in 1812 – 1813 (significantly, the French period) and subse-quently stolen by some Neapolitan ruffian.14 One would expect a manuscript from Naples to be a papyrus from the Villa dei Papiri in the collection of the Officina dei Papiri, but this work was supposed to have been written some decades after the eruption of 79 CE and so could not have been found in the villa. L’Héracléade is dedicated to Pliny the Younger, and the “author” — not indicated, except on the title page of the publication — is assumed to be Florus, a his-torian who lived at the beginning of the sec-ond century CE. The “editor” mixes various elements of the “lost manuscript” genre. He publishes a poetic translation made after the original prose of the now lost manuscript

and supplies a voluminous commentary. The result is a poetic elaboration of the supposed original prose version consisting of ten chants (cantos) in alexandrines with the rhyme scheme AA-BB-CC. To my knowledge this manuscript, if real, would have con-tained the only mythological explanation of why Herculaneum and Pompeii were destroyed by Vesuvius.

The first canto, starting with an appeal to the Muses and the aforementioned dedica-tion to Pliny, tells about the Gigantomachia — the cosmic struggle in which the Olympians, with the aid of Hercules, defeated the Giants, or forces of chaos — and the foundation of Herculaneum by Hercules. In our days — those of “Flavius,” who is none other than the emperor Vespasian — the town has rebuilt the Temple of Cybele. Nevertheless, Cybele hates the people because of their impiety:

Mais Flavius, poussé d’un religieux zèle,

A peine a rétabli le temple de Cybèle,

Qu’à l’approche des jeux où doit être honoré

Des murs d’Herculanum le fondateur sacré,

La déesse, agitant sa couronne hautaine,

Dit: “Cette ville en butte à ma constante haine,

Déjà de sa mémoire effaçant la terreur,

Croit avoir epuisé ma féconde fureur.

Ses toits sont réparés, et partout ses statues

Ont relevé dans l’air leur faces abattues. . . .”15

(But Flavius, impelled by religious ardor, had just rebuilt

the temple of Cybele, when, upon the arrival of the

games honoring the holy founder of Herculaneum’s

walls, the goddess said, moving her haughty crown:

“This city, object of my constant hatred, already erasing

terror from its memory, believes itself to have extin-

guished my strong anger. Its roofs have been repaired

and everywhere its statues have raised their dejected

faces to the air.”)

The poem invokes old enemies of Hercules. Every god’s story, for instance those of Vul-can and Neptune, is told at length. The latter is offended by the settlements of houses on the shores of Campania, which are his shoulders:

Aux habitants du golfe un jour je dois reprendre

Le rivage usurpé que leur luxe ose étendre,

C B

M Y

No.005

J121

0041

Siz

e: W

:9”X

11”

175L

196

196 rediscovering the ancient world on the bay of naples

Et sur les fondements des plus fermes palais

Le pêcheur conduira sa barque et ses filets.16

(One day I must take back from the inhabitants of the

Bay the usurped coast that their luxury dares to extend.

Then the fisherman will move his boat and his nets over

the foundations of the strongest palaces.)

In the second canto the reader attends a feast in honor of Ceres in Sicily. Vulcan starts constructing a tunnel to connect Etna with Vesuvius. The rumors and shaking of the sea bottom impel the sea god Nereus to placate his nymphs. The winds, guided by Boreas, want to assist Cybele’s party, as they were treated badly by Hercules during the Argo-nauts’ expedition. Hercules, in the meantime, has become effeminate under the influence of Omphale and the nymphs. In canto 3 other collaborating gods are introduced. So Cybele goes to Vesuvius, and

Aux entrailles du mont Cybèle même arrache

Les pierres et l’argille et les poudreux monceaux

Que l’immortelle artiste entasse en ses fourneaux

Et forge en traits sans nombre, où son art amalgame

L’onde, le soufre actif, le nitre qui l’enflamme,

Le bitume tenace et qui s’enfle allumé,

Et le métal qui coule en ruissaux transformé.

Ainsi les durs métaux et les marbres solides,

Assujettis par l’homme à ses besoins avides,

Ici, des éléments pernicieux rivaux,

S’unissent pour détruire et l’homme et ses traveaux!17

(From the bowels of the mountain Cybele extracts

stones, clay, and dusty heaps, which the immortal artist

piles in his furnaces and forges in works without number

in which he artfully melts water, active sulfur, enflaming

saltpeter, viscous bitumen that swells if kindled, and

metal that, transformed, streams in rivulets. Thus, the

hard metals and the solid marbles, subjected by man to

his rapacious needs, here, from dangerous rival ele-

ments come together to destroy man and his works!)

Cybele asks for help from the Giants, who have their own reasons to destroy Hercula-neum, since they had been defeated by Her-cules in the Gigantomachia.

In canto 4, Herculaneum is feasting in honor of Hercules. Maizony starts with an evocation of the half-round bench, or schola, in the Street of Tombs in Pompeii at what was in his time the main entrance to the excavations (fig. 3):

Pompéia, non sans crainte, entend sous le tombeau

Soupirer Mamia, sa publique prêtresse;

Ses murs mal raffermis accroissent sa détresse;

D’une timide mer elle répare encore

Son forum mutilé, morne et vaste trésor

De colonnes sans base, et d’insignes statues

Sur la dalle en débris par Cybèle abattues.18

(Not without fear, Pompeii hears Mamia, its public

priestess, sighing under the tomb; its badly reinforced

walls increase her distress; still Pompeii protects against

a timid sea its ruined forum, a vast and gloomy treasure

of columns without bases and of remarkable statues,

smashed to debris on the pavement by Cybele.)

In front of the temple of Hercules at Hercu-laneum, which contains painted depictions of his deeds, people offer a mooing cow (“la mugissante offrande”), and a priest praises the greatness of the hero who played a major role in the Gigantomachia.19 In canto 5, a production of Euripides’ Alcestis, in which Hercules is an important character, is staged.

2. Title page, L’Héracléade ou Herculanum enseveli sous la lave du Vésuve, poëme de L. A. Florus (Paris, 1837)

Author collection

No.005

J121

0041

Siz

e: W

:9”X

11”

175L

197

C B

M Y

197 moormann Literary Evocations of Herculaneum in the Nineteenth Century

The poet sings to Calliope and records Her-cules as the leader of the Muses (Hercules Musarum or Musagetes), but:

Si ta Muse pouvait, de miracles prodigue,

Défendre Herculanum d’une invisible ligue,

Cette illustre cité, qui d’Athènes autrefois

Reçut la colonie et garde encor les lois,

Qui s’enivre, déjà vers la tombe penchée,

D’une source de pleurs de ton âme épanchée,

Tu serais de ses murs le second fondateur.20

(If your Muse, prodigal with miracles, could defend

Herculaneum against an invisible collusion this illustri-

ous city, which long ago was a colony of Athens and still

keeps its laws, and already inclines toward the tomb,

inebriated from a spring of tears pouring forth from your

soul, you would be the second founder of its walls.)

In canto 6 the explosion of Vesuvius causes chaos. People try to escape, and Pliny the Elder addresses the Muse:

La nuit funeste augmente, et déjà m’enveloppe.

Muse, à mes yeux troublés fais voir que Calliope

Aussi bien que Diane est la soeur d’Apollon,

Et répands sur ma route un lumineux sillon.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Tu m’exauces, déesse: à travers les ténèbres

Je découvre, grands dieux! quelles scènes funèbres!21

(The deadly night increases and already surrounds me.

Muse, show my troubled eyes that Calliope is as much

Apollo’s sister as Diana, and spread on my way a lumi-

nous track. . . . You help me, goddess: throughout the

darkness I discover, great gods! Such deadly scenes!)

This drama is worse than war. Witness a suffering family:

L’enfant qu’à son sein nu cette mère suspend

Avec elle gémit, mais les pleurs qu’il répand

Ne sont point pour des maux qu’il ne saurait connaître,

Les sanglots de sa mère, hélas! seuls les font naître;

Elle pleure un époux qui, s’immolant pour eux,

En roidissant sa tête et ses bras vigoureux

Pour soutenir d’un toit la terrasse écroulée,

A plongé sous le faix. . . .22

(The child that his mother holds at her bare breast

weeps with her, but the tears he sheds are not for the

misfortunes he could not know; they are, alas! for the

sobs of his mother. She cries over a husband who, sacri-

ficing himself for them by forcing his head and vigorous

arms to sustain the crumbled terrace of a roof, has fallen

under the load.)

People scream, pray, look for shelter and pre-pare meals for the dead. Pliny is reckless (‘téméraire’)23 in pursuit of his research and leaves his son [sic] to read Livy. In canto 7 he is on the beach, watching a new eruption, for which he seeks an explanation. Pliny’s death is compared to that of the Greek philosopher Empedocles, who jumped into the crater of Etna. Even Nature halts a moment, but only to continue more furiously. There follows a long description of the Giants. Next, in canto 8, the spirits of the dead rise from their tombs. Edifices collapse from the tremors of

3. Johann Heinrich Wilhelm Tisch-bein, Portrait of Anna Amalia of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach (showing the Bench of Mamia in the Street of Tombs, Pompeii), 1788 / 1790, oil on canvas

Klassik Stiftung Weimar

C B

M Y

No.005

J121

0041

Siz

e: W

:9”X

11”

175L

198

198 rediscovering the ancient world on the bay of naples

the earth. Even Hades is shaken, and Pluto can no longer exercise his powers:

Pluton, près d’énoncer le jugement fatal,

De son trône s’élance, et d’une voix émue

S’écrie en pâlissant: “Quelle cause imprévue,

Ou plutôt quel pouvoir, de mon sceptre envieux,

Trouble ainsi le silence et la nuit de ces lieux? . . .”24

(Pluto, at the point of declaring the final judgment,

jumps from his throne and exclaims in an agitated voice,

growing pale: “What unforeseen cause, or rather what

power envious of my scepter disturbs in this way the

silence and night of this place?”)

Father Jupiter explains that the oracular prophecy has come true. The ancient city will never suffer future wars. In these lines near the end of the poem, a new — archaeologi-cal — splendor is announced and reference is made to the open-air excavations in progress at this time. And to Hercules he declares, You, my son, will be satisfied. Pompeii will reappear as well and all nations will hail us:

Dévoilée à l’éclat de leur flambeau magique

Ta ville secouera sa cendre léthargique,

Et reverra le jour, mon fils, et son tombeau

De ses murs rajeunis deviendra le berceau.

Pompéia, qui subit le destin d’Héraclée,

Comme elle à la lumière en ces temps rappelée,

Vivante sortira de son sépulcre épais;

Et de toute insolence affranchis désormais,

Nos temples radieux, peuplés de leurs images.

Du monde émerveillé recevront les hommages,

Et les peuples divers et leurs pasteurs pieux

De Rome triomphant adoreront les dieux.25

(Unveiled under the beams of their magic torch your

town will shake off its lethargic ashes and will see the

light of day, my son, and the tomb of its rejuvenated

walls will become its cradle. Pompeii, which suffered the

fate of Herculaneum, is recalled to the light in these days

in the same way, and, living, will leave its heavy tomb;

and from now on our shining temples filled with images

will be freed of all arrogance. They will receive honor

from the astonished world and the diverse peoples of

triumphant Rome and their pious priests will worship

the gods.)

The theme of this epic — the revenge of the Giants and their friends for the defeat they suffered in the Gigantomachia — won by the gods only with the help of (mortal) Hercu-

les — is unique within fiction about Pompeii and Herculaneum. An inspiration for its theme could have been a rumor recorded by Dio Cassius about the beginning of the erup-tion, a story that was repeated in various travel accounts:

Numbers of huge men quite surpassing any human

stature — such creatures, in fact, as the Giants are

pictured to have been — appeared now on the mountain.

Now in the surrounding country, and again in the cities,

wandering over the earth day and night and also flitting

through the air.26

Maizony did his best to fit his poem into the tradition of learned epic poetry in both Latin and Greek. His main source of inspiration was the anonymous poem Aetna, ascribed to Virgil from the second century onward, to the late antique Claudius Claudianus, and to Lucilius, the addressee of Seneca’s letters (his letter 79 mentions it). It traces the natural phenomenon of vulcanology through the leads of mythological figures like the Giants (and their riot) and the Winds. As Vesuvius is not mentioned, dating the text to before 79 CE may have seemed plausible. The Giants were a popular subject of Roman poetry, and Maizony may have taken bits and pieces from various sources.27 Other literary inspi-rations, such as Virgil’s voyage through Hell in Dante’s Divina Commedia, cannot be disregarded.

In 1504 the learned Neapolitan Renais-sance poet Iacopo Sannazaro (1458 – 1530) published Arcadia, which contains one of the first references to Pompeii since antiquity. A nymph brings the storyteller Sincero from Arcadia to his native city of Naples by a sub-terranean route. In chapter 12 they see the Giants sweating under Mount Etna, and a tunnel leads them underground to Vesuvius. There they pass under Pompeii:

La pene de’ fulminanti Giganti, che volsero assalire il

cielo, son di questo cagione; i quali, oppressi da gravis-

sime montagne, spirano ancora il celeste fuoco, con che

furono consumati. Onde avviene che sì come in altre

parti le caverne abondano di liquide acque, in queste

ardeno sempre di vive fiamme. E se non che io temo che

forse troppo spavento prenderesti, io ti farei vedere il

C B

M Y

No.005

J121

0041

Siz

e: W

:9”X

11”

175L

199

199 moormann Literary Evocations of Herculaneum in the Nineteenth Century

superbo Encelado disteso sotto la gran Trinacria eruttar

fuoco per le rotture di Mongibello; e similmente la

ardente fucina di Vulcano, ove gli ignudi Ciclopi sovra le

sonanti ancudini battono i tuoni a Giove; et appresso poi

sotto la famosa Enaria, la quale voi mortali chiamate

Ischia, ti mostrarei il furioso Tifeo, dal quale le estenuanti

acque di Baia e i vostri monti del solfo prendono il lor

calore. Così ancora sotto il gran Vesevo ti farei sentire li

spaventevoli muggiti del gigante Alcioneo; benché questi

credo gli sentirai, quando ne avvicinaremo al tuo Sebeto.

Tempo ben fu che con lor danno tutti i finitimi li sentirono,

quando con tempestose fiamme e con cenere colperse i

circonstanti paesi, sì come ancora i sassi liquefatti et arsi

testificano chiaramente a chi gli vede. Sotto ai quali chi

sarà mai che creda e populi e ville e città nobilissime

siano sepolte? Come veramente vi sono, non solo quelle

che da le arse pomici e da la ruina del monte furono

coperte, ma questa che dinanzi ne vedemo, la quale

senza alcun dubbio celebre città un tempo nei tuoi paesi,

chiamata Pompei, et irrigata da le onde del freddissimo

Sarno, fu per sùbito terremoto inghiottita da la terra,

mancandoli credo sotto ai piedi il firmamento ove fun-

data era. Strana per certo et orrenda maniera di morte, le

genti vive vedersi in un punto tòrre dal numero de’ vivi!

Se non che finalmente sempre si arriva ad un termino, né

più in là che a la morte si puote andare. —

E già in queste parole eramo ben presso a la città che lei

dicea, de la quale e le torri e le case e i teatri e i templi si

poteano quasi integri discernere. Meravigliaimi io del

nostro veloce andare, che in sì breve spazio di tempo

potessemo da Arcadia insino qui essere arrivati; ma si

potea chiaramente conoscere che da potenzia maggiore

che umana eravamo sospinti.28

(The punishments of the lightning-stricken Giants who

meant to storm the heavens are the cause of this; they,

weighted down with most ponderous mountain masses,

are breathing forth still the heavenly fire with which they

were consumed. Hence it comes, just as in other regions

the caves abound with flowing waters, in these they

always burn with living flames. And except that I fear

that perhaps you would receive too great a fright, I

would cause you to see proud Enceladus, stretched out

under mighty Triacria [Sicily], belching flame through

the fissures of Mongibello; and likewise Vulcan’s fiery

forge, where the naked Cyclopes hammer out thunder-

bolts for Jupiter upon their ringing anvils; and after that

beneath renowned Enaria — which you mortals call

Ischia — I would show you rabid Typhœus, from whom

the warm baths of Baiae and your sulfurous mountains

receive their heat. So also under lofty Vesuvius I would

make you hear the fearful groanings of the giant Alcyon;

though these, I believe, you will hear when we draw nigh

to your Sebeto. Time was indeed, that all the neighbor-

ing populace heard them, to their hurt, when he covered

the surrounding countryside with tempestuous flames

and with ashes, as the liquefied and blackened rocks

clearly testify to him who sees them: who will there ever

be who could believe that under these, peoples and

villas and most noble cities are buried? As truly they are,

not only those that were covered by pumice ash and by

the ruin of the mountain, but this that we see before us,

which without any doubt (being at one time a famous

city in your region, called Pompeii, and washed by the

waves of the coldest Sarno) by sudden quake was swal-

lowed by the earth, the firmament whereon it was

founded failing, I understand, from under men’s feet.

Surely, a strange and horrible kind of death, living people

to see themselves stricken in a moment from the num-

ber of the living! Save that ultimately one always arrives

at one destination, nor is there any travelling on from

there except to death. —

And speaking these words, we already were next to the

town she mentioned of which we could see the towers,

houses, theaters, and temples almost complete. For our

swift pace I wondered whether we could have arrived

here in so brief a time from Arcadia, but one could

clearly acknowledge that we were driven by a greater

force than a human one.)

Sannazaro was widely read; his work was translated into various languages and enjoyed a host of literary imitators. Maizony quotes him in his commentary and may have been influenced by him directly.29 This is probably not the case for the following two poems. Well known in Germanic countries, Martin Opitz (1597 – 1639) was seen as an outstanding poet, not least for his poem Vesuvius, of 1633, intended to explain the phenomenon of volcanism. This work is peculiar in that it neither describes nor hints at the recent disaster, that is, the tremendous eruption of Vesuvius in 1631, but tries to discover the principles of volcanology and the possible role of God.30 The greater part is intermingled with excurses in prose in which Opitz shows a complete command of the ancient sources on volcanoes. He is the first modern poet to describe the eruption in 79 CE in a way that reconstructs the cata-clysm that struck Herculaneum and its surroundings; Pompeii is not mentioned. A few passages must suffice to give an impres-sion of Opitz’ powerful work. He starts by

C B

M Y

No.005

J121

0041

Siz

e: W

:9”X

11”

175L

200

200 rediscovering the ancient world on the bay of naples

Der kan sein trewes Weib und Kinder nicht verlassen

Und jeglicher bemüht mit sich etwas zu fassen

Das ihm für allen lieb: doch folgt der Raub nicht gar

und mancher kompt durch Geitz in Jammer und Gefahr

Bleibt selber wo sein Geld. . . .

(Old Herculaneum, pleasant castle called Octavian

[Ottaviano], many fields laden with fruit and villages

burn, waters flee fearfully from the land. Those who

have not yet suffocated and been snatched away come

out breathless and robbed of force, lame, naked, and

half-dead, and fill with plaints and wailings the entire

heaven, which also cries with them and suffers. They

are like a soldier who, in the face of the enemy and

death, has blinding dust in his eyes, is burning with

fever, and runs into them, thinking himself to be out of

danger. In the same way they run over wood and stone,

blind from fear and ashes. One lets his walls burn,

another drags his poor father who, old and weak, barely

knows how to follow and lugs his staff along. Another

cannot leave his loyal wife and children. Everyone is

occupied with something that is beloved above all but

which he does not succeed in taking away, and some

come to misery and danger through greed, remaining

with their money.)

David Mallet (1705 – 1765) displays a similar fascination for volcanoes in The Excursion of 1728, in which nature and man-made towns disappear during an eruption of liq-uids boiling and moving under the earth:

. . . the fluid lake that works below,

Bitumen, sulphur, salt, and iron scum,

Heaves up it’s [sic] boiling tide. The lab’ring mount

Is torn with agonizing throes. At once,

Forth from its side disparted, blazing pours

A mighty river; burning in prone waves,

That glimmer thro the night, to yonder plain.

Divided there, a hundred torrent-streams,

Each ploughing up it’s bed, roll dreadful on,

Resistless. Villages, and woods, and rocks,

Fall flat before their sweep. The region round,

Where myrtle-walks and groves of golden fruit

Rose fair; where harvest wav’d in all it’s pride;

And where the vineyard spread its purple store,

Maturing into nectar; now despoil’d

Of herb, leaf, fruit, or flower, from end to end,

Lies buried under fire, a glowing sea.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Ruin ensues: towers, temples, palaces,

Flung from their deep foundations, roof on roof

Crush’d horrible, and pile on pile o’erturn’d,

Fall total — In that universal groan,

saying that the disaster seemed to come of a sudden, for the volcano looked serene, as does nature generally:

Die Welt liegt unbesorgt mit sanffter Ruh ummgeben,

Als alles Landt umbher beginnet zu erheben

Sich selbst und was es trägt; es giebt der grossen Last

Mit Furcht und zittern nach; das arme Volck verblast

Der Häuser Rücken bebt

die See wird auch erreget

Biß daß Aurora kompt noch bleicher als sie pfleget

Und ihren weissen Zug fast hinter sich läst gehen

Dieweil sie umb den Berg sieht eine Wolcken stehn

Dardurch ich heller Glantz mit allen seinen Strahlen

Zu dringen nicht vermag / noch weiters weiß zu mahlen

Das gantz betrübte Feldt. . . .31

(Untroubled, the world lies shrouded in rest, when the

entire land around starts to move itself and what it

supports. It lets fall the great weight with fear and trem-

bling. The poor people become pale, the back walls of

the houses tremble and the sea is also moved until

Aurora comes, even paler than usual, and almost leaves

her white train behind her, for she sees a cloud sur-

rounding the mountain, through which her radiance

cannot penetrate with all its beams, let alone paint white

the entire sad field.)

Everything is taken by the fire, Hercula-neum, Ottaviano, and other villages, and people react in fear and panic. Families try to flee together, and some avaricious persons die because of their foolish wish to keep their money:

. . . das alte Herculan

Das lustige Castell genandt Octavian

Viel Flecken voller Frucht und Dörffer stehn im Brande

Die Wässer fürchten sich und fliehen von dem Lande

Das Volck so nicht erstickt und gar wird fortgerafft

Kompt Athemloß daher, beraubet aller Krafft

Lahm / nackend und halb todt

und füllt mit Wehe und Zagen

Den gantzen Himmel an / der gleichsam mit ihm klagen

Und auch sich kümmern muß. Wie etwan ein Soldat

Wann daß er Feind und Todt vor seinen Fäusten hat

Und ihm der blinde Staub gleich under Augen stehet

Erhitzet Fewer giebt / und da er meynt er gehet

In dessen auß Gefahr / so rennt er mehr hinein:

Nicht anders lauffen sie auch ober Stock und Stein

Von Angst und Asche blind: der giebet seinen Wänden

So brennen gute Nacht; der reißt mit beiden Händen

Den armen Vatter fort / der nunmehr alt und schwach

Gar kaum zu folgen weiß / und zeucht den Stab hernach;

C B

M Y

No.005

J121

0041

Siz

e: W

:9”X

11”

175L

201

201 moormann Literary Evocations of Herculaneum in the Nineteenth Century

Sounding to heaven, expir’d a thousand lives,

O’erwhelm’d at once, one undistinguish’d wreck!32

In this work, Mallet demonstrates our tran-sience in a thrilling and dramatic way. The appearance of the volcano is deceptive:

Yon neighbouring Mountain rising blank and bare,

It’s double top in steril ashes hid,

But green around it’s base with oil and wine,

Gives sign of storm and desolation near:

Store-house of fate! from whose infernal womb,

With firey minerals and metallic ore

Pernicious fraught, ascends eternal smoke: . . .

Returning now to Maizony’s epic, the poem is clearly a hoax, as was noted as early as 1854 in an essay on French literature by an anonymous American writer: “So late as 1837, Maizony de Lauréal presented to the public a French translation of a poem by the Roman Florus, upon the destruction of Her-culaneum; but, unfortunately, he has hitherto omitted to produce the Latin original, and consequently the general opinion is that the whole affair is a hoax.”33 His attribution of the found but later stolen manuscript to Flo-rus is unconvincing.34 He should have chosen another writer of the silver age of Latin, such as Statius, a poet from Neapolis, who had much success with his epic poems in the last decade of the first century CE. Apparently, the French poet wanted to link L’Héracléade to Pliny the Younger, who had described the eruption so forcefully in his letters. The strange mistake — referring to the two Plinys as father and son in the poem — can be explained as the result of a desire to empha-size their affectionate bond and to enhance the drama. The allusion to peace for Hercu-laneum under the earth reflects the many wars in the period previous to the 1837 pub-lication date, but also the decay of ancient monuments in cities like Rome, always visi-ble outdoors while suffering the devastating forces of nature and man. It is worth noting that Leopardi offers similar solace in his work and alludes to a fortunate future.

Maizony’s interest in Vesuvius follows a strong tradition in French letters. Mme. de

Staël wrote of the mountain in Corinne and in her Carnets de voyage.35 More important, in form Maizony’s work is entirely French. After looking in vain for correspondences in seventeenth-century classics, I turned to Vol-taire’s Henriade, published in the same year as Mallet’s small epic. Voltaire’s is a work for which Maizony de Lauréal wrote an addition, La petite Henriade, ou l’enfance d’Henri IV.36 But taking Voltaire’s poem together with Maizony’s, it is not difficult to find a series of correspondences: form, language, and style in the first place, but also the use of gods and personifications, the force of nature (more logical in L’Héracléade than in Voltaire’s his-torical account of Henri) and the way dia-logues are composed. The form of ten cantos, with a synopsis (argomento), and the learned commentary at the end are other examples of congruence. As in the great predecessors, both poets insert long stories to give founda-tions to their own narratives. The most strik-ing use of a sort of allegory is the image of Discord flying to Rome, in canto 4, to seek help against Henri for the fighting but weak-ened general, the duc d’Aumale, in canto 4:

La Discorde le vit, et trembla pour d’Aumale:

La barbare qu’elle est a besoin de ses jours:

Elle s’éleve en l’air, et vole à son secours.37

(Discord saw him and feared for d’Aumale. She, though a

barbarian, fears to lose a life so dear: she rises in the air

and flies to the rescue.)

Cybele seems a figure similar to Voltaire’s Discord.38 Just as, in canto 7 of the Henriade, Henri is encouraged by King Louis XII in a dream, in L’Héracléade Hercules receives good words from his father Jupiter. There is, in fact, a constant traffic of messengers and gods imploring colleagues to help them.39 The hell described in Voltaire’s canto 7 also showed Maizony how to evoke the under-world, whereas canto 9 describes the beauti-ful land of Love, which would correspond to the description of Campania. Here is Hell:

Henri dans ce moment, d’un vol précipité

Est par un tourbillon dans l’espace emporté

Vers un séjour informe, aride, affreux, sauvage,

C B

M Y

No.005

J121

0041

Siz

e: W

:9”X

11”

175L

202

202 rediscovering the ancient world on the bay of naples

De l’antique chaos abominable image,

Impénétrable aux traits de ces soleils brillants,

Chefs-d’oeuvre du Très-Haut, comme lui bienfaisants.

Sur cette terre horrible, et des anges haïe,

Dieu n’a point répandu le germe de la vie,

La Mort, l’affreuse Mort, et la Confusion,

Y semblent établir leur domination.

“Quelles clameurs, ô Dieu! quels cris épouvantables!

Quels torrents de fumée! et quels feux effroyables!

Quels monstres . . . volent dans ces climats!

Quels gouffres enflammés s’entr’ouvrent sous

mes pas!”40

(At this moment Henri is suddenly taken by a whirlwind

toward a shapeless, dry, terrible, and wild place, an

appalling image of ancient chaos, impenetrable to the

rays of these brilliant suns, masterworks of the Almighty,

beneficent like him. On this horrible ground, hated by

the angels, God has not yet disseminated the germs of

life. Death, dreadful Death and Confusion seem to

establish here their dominion. “What clamors, O Lord,

what awful cries! What torrents of smoke! and what

terrifying fires! What monsters . . . fly in these airs! What

inflamed abysses open under my steps!”)

Conclusion

The few examples of literary evocations of Herculaneum presented in this essay show the great interest the ruins awoke among vis-itors from Europe from the start of the exca-vations. The expressions range from initial wonder and bewilderment to the subsequent evocation of a fantastic realm and are inter-mingled with emotional reactions to decay and death. The kings of Naples received great praise for their tunnel excavations in the eighteenth century but encountered criti-cism because of the extraction of all objects, mosaics, and wall paintings, and — still more — the refusal to lay these treasures bare to the light of day. Therefore, acclaim was expressed in the nineteenth century for open-air excavations, however limited.

In the interest Herculaneum aroused, another focal point was the library of the Villa dei Papiri. Because the decipherment of the papyrus scrolls progressed too slowly in the eyes of impatient visitors to Naples, these manuscripts stimulated the compilation of

“authentic” texts, mock manuscripts suppos-edly found in the excavations. Another factor

was the absence of great masterpieces, lacu-nae within the corpus of classical texts — and to this day we regret the lack of such works. Various authors thus practiced imitation and emulation by compiling manuscripts of their own. I have discussed Maizony de Lauréal’s L’Héracléade, allegedly a text by the Roman author Florus found under the ashes spread by Vesuvius, as an example of this fashion. The description of the destruction of Hercu-laneum by the Giants, instigated by Cybele, is unique as an explanation of the fall of the Vesuvian towns. Maizony, however, fits into an established tradition of poems on volca-noes, some of which I see as predecessors of his work. In form, the work is an adaptation of a popular work by Voltaire.

In all literary works Herculaneum is an exemplar of drama rather than an archaeo-logical resource from which we can glean knowledge about ancient society. Buildings and objects rarely play a concrete role in the evocation of this small Mediterranean town swallowed by Vesuvius. Herculaneum becomes an intellectual or literary construct. The ruins themselves do not come to life as do those of Pompeii with their human remains and easily accessible houses, temples, and public buildings. Recent excavations in the Villa dei Papiri seem to have stimulated a new generation of authors to play with the motif of lost manuscripts, but that must be the topic of another study.

C B

M Y

No.005

J121

0041

Siz

e: W

:9”X

11”

175L

203

203 moormann Literary Evocations of Herculaneum in the Nineteenth Century

notes

1. Luciana Jacobelli, Pompei: La costruzione di un mito (Rome, 2008), 7 – 8. On the restoration project, see Andrew Wallace-Hadrill, Herculaneum: Past and Future (London, 2011). See also the essay by Eugene J. Dwyer,

“Pompeii versus Herculaneum,” in this volume.

2. George Knapton, letter to Charles Knapton, extract in Philosophical Transactions, Giving Some Account of the Present Undertakings, Studies, and Labours, of the Inge-nious in Many Considerable Parts of the World 41 (1744, for the years 1739 – 1741): 489 – 493. The two quotations are from 490 – 491. On Knapton see Bruce Redford, Dilettanti: The Antic and the Antique in Eigh-teenth-Century England (Los Angeles, 2008), 13 – 43, and Laurentino García y García, Nova bibliotheca pom-peiana: 250 anni di bibliografia archeologica (Rome, 1998), no. 7440.

3. I know of three modern novels about Herculaneum. Richard Llewellyn, The Flame of Hercules (Garden City, NY, 1955) is about a fugitive slave’s adventures in Her-culaneum shortly before the eruption. Two recent works were inspired by the 1990s excavations in the Villa dei Papiri. The first, Michela Ascione, La Villa dei Papiri (Imperia, 2007), is about an illegal dig, with elements of a detective thriller, in a modern Neapolitan setting of university and state archaeological service. The second, Carol Goodman, The Night Villa (New York, 2008) describes a search for supposedly antique manuscripts by Pythagoras, sought after by a religious sect in the United States, focusing on a Bill Gates – like mogul and a group of religious fanatics amid more or less serious classicists and archaeologists from the University of Texas. In both works the ancient town of Herculaneum is little more than a backdrop, whereas the Hercula-neum of Llewellyn is entirely fictitious.

4. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford, 2004), s.v. “Gisborne, Thomas,” by Robert Hole, 356 – 357.

5. Thomas Gisborne, “Herculaneum,” in Translations of the Oxford and Cambridge Latin Prize Poems, 2nd series, trans. Nicholas Lee Torre (London, 1833), 61–71. Not in García y García 1998.

6. Dio Cassius, Roman History 66.23; for an English translation, see Dio’s Roman History, with an English Translation, trans. Earnest Cary and Herbert Baldwin Foster, vol. 8 (London, 1955).

7. The Poems of William Wordsworth, ed. Nowell Charles Smith (London, 1908), 361 – 362, from Poems of Sentiment and Reflection, no. 28; The Poems, ed. John Olin Hayden (New Haven, 1977), 401 – 402. There are short references in Curt Dahl, “Recreations of Pom-peii,” Archaeology 9 (1956): 182 – 191, especially 186, and Wolfgang Leppmann, Pompeji: Eine Stadt in Litera-tur und Leben (Munich, 1966), 129, 148, who stresses Wordsworth’s love for northern Italy. Wordsworth vis-ited Italy in 1822 (see his Memoirs of a Tour on the Continent of 1822) and 1842. His unrelated namesake (1835 – 1917), a fellow of Balliol College, Oxford, would publish two poems about Pompeii as works of the older Wordsworth in Gleanings of Verse (privately printed, London, 1899), 38 – 39. García y García 1998,

no. 14.453. Many of the poems in this volume had been published previously in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine.

8. Eric M. Moormann, “Una città mummificata: Qual-che aspetto della fortuna di Pompei nella letteratura europea ed americana,” in Pompei: Scienza e società, ed. Pier Giovanni Guzzo (Milan, 2001), 9 – 18; Moormann,

“Evocazioni letterarie dell’antica Pompei,” in Storie da un’eruzione: Pompei, Ercolano, Oplontis, ed. Pier Giovanni Guzzo (Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Naples; Milan, 2003), 15 – 33 (also in English, German, French, and Dutch editions).

9. Antonio Sogliano, Pompei nella letteratura (Naples, 1888), 30; see also notes 10 – 11 and Moormann 2001 and 2003. García y García 1998, no. 7927.

10. Vincenzo Bracco, “Leopardi e le antichità napole-tane,” in Leopardi e il mondo antico: Atti del V Con-vegno Internazionale di studi leopardini, Recanati, 22 – 25 settembre, 1980 (Florence, 1982), 301 – 319, especially 316 – 318. Compare Moormann 2001, 16. Leopardi knew Sannazaro’s work very well, as is evident in his Zibaldone di pensieri, ed. Giuseppe Pacella, 3 vols. (Milan, 1991), 3:1458, s.v. “Sannazaro.”

11. See also Sabine Rothemann, “Als baute der Mensch im Hinblick auf die Ruinen: Pompeji als literarisches Motiv,” in Protomoderne: Künstlerische Formen über-lieferter Gegenwart, ed. Carola Hilmes and Dietrich Mathy (Bielefeld, 1996), 71 – 86, especially 74 and 77 – 78.

12. Drawing in Musée Bonnat, Bayonne. According to the museum’s catalogue entry, Maizony de Lauréal was a clerk of the imperial court in Bayonnne, where he and his wife held a salon frequented by French artists, among them Ingres. See http://www.museebonnat .bayonne.fr/index.php?rub=recherche&fiche=95CE17291&typ=2&type=3&fiche=95CE7364 (accessed Decem-ber 22, 2011).

13. Joseph-François-Stanislas Maizony de Lauréal, L’Héracléade, ou Herculanum enseveli sous la lave du Vésuve, poëme de L. A. Florus (Paris, 1837). See http://www.vialibri.net/cgi-bin/book_search.php?refer=start& authword=maizony+de+laureal&wt=20&fr=s&sort=yr&order=asc&lang=en&act=search&cty=US&hi_lo =hi&curr=USD&y=8250 (accessed June 22, 2012); according to this entry Maizony worked in Florence. He also wrote La petite Henriade, ou l’enfance d’Henri IV, poème en trois chants avec des notes historiques et litté-raires, présenté à S.A.R. Mgr le Duc de Bordeaux, to be discussed later in this essay (Paris, 1824), also quoted in Maizony de Lauréal 1837, xii. Mark Everist, Music Drama at the Paris Odéon, 1824 – 1828 (Berkeley, 2002), 108, recalls him as the libretto writer of Louis XII ou La Route de Reims (1825) by Alphonse Vergne, on which work see his pages 158 – 167 and 169.

14. García y García 1998, no. 3949.

15. Maizony de Lauréal 1837, 13. This and the follow-ing translations are mine.

16. Maizony de Lauréal 1837, 23.

17. Maizony de Lauréal 1837, 61.

C B

M Y

No.005

J121

0041

Siz

e: W

:9”X

11”

175L

204

204 rediscovering the ancient world on the bay of naples

32. David Mallet, The Excursion: A Poem in Two Can-tos (London, 1728). Here quoted from The Works of D. Mallet (London, 1759), 6 – 110, reprinted in Heinz Gäumann, David Mallet: The Excursion; Mit einem Überblick über das dichterische Gesamtwerk, published PhD diss. (Zürich, 1977). García y García 1998, no. 8675. Mallet is not mentioned in Von der Thüsen 2008 or Williams 2008.

33. Anonymous, “Literary Impostures,” North American Review 78 (1854): 305 – 345, quotation, 314. I owe this reference to Thomas Willette, who also remembered the inclusion of the Héracléade in Friedrich Furchheim, Bibliografia di Pompei, Ercolano e Stabia (Naples, 1891), xxiii and 23, as a scholarly publication.

34. As to Florus, there is some confusion of identity among the poet Annius Florus, the orator P. Annius Florus and / or the historian L. Annaeus Florus (or Julius Florus), all of whom may be the same person. See Michael von Albrecht, A History of Roman Literature, from Livius Andronicus to Boethius, 2 vols. (Leiden, 1997), 2:1411 – 1420, especially 1411 n. 1. In Maizony de Lauréal 1837, vii, the form is Annaeus Florus. Florus’ remarks on the Vesuvian cities are in his Epitome of Roman History 1.11.3 – 6 and 2.8.45, but they do not pertain to the eruption.

35. Anne Louise Germaine Necker, baronne de Staël, Corinne ou l’Italie (Paris, 1807), book 13, “Le Vésuve et la Campagne de Naples,” ch. 1, and Les carnets de voy-age de Madame de Staël: Contributions à la genèse de ses œuvres, ed. Simone Balayé (Geneva, 1971), 120. Compare Franc Schuerewegen, “Volcans: Mme de Staël, Gobineau, Gautier,” Les lettres romaines 45 (1991): 319 – 328. See the many references to the eruption in Pierre Larousse, Grand dictionnaire universel du XIXe siècle (Paris, 1866 – 1890), 267 – 268, s.v. “Lave”; 963 – 964, s.v. “Vésuve”; 964, s.v. “Vésuvien, -ienne”; 1169 – 1170, s.v. “Volcan.”

36. See note 13.

37. Voltaire, Complete Works of Voltaire / Les œuvres complètes de Voltaire, vol. 2., La Henriade, ed. Owen R. Taylor (Paris, 1970; 1st ed., London, 1728), 445 (canto 4, lines 96 – 98). The translations are mine.

38. Compare the fragment quoted above (Maizony de Lauréal 1837), 61 with canto 4, lines 157 – 166 (Voltaire 1970, 447 – 448), on Discord’s devastating work: “La Discorde aussitôt, plus prompte qu’un éclair, / Fend d’un vol assuré les campagnes de l’air. / Partout chez les Fran-çais le trouble et les alarmes / Présentent à ses yeux des objets plains de charmes : / Son haleine en cent lieux répand l’aridité ; / Le fruit meurt en naissant, dans son germe infecté : / Les épis renversés sur la terre languis-sent ; / Le ciel s’en obscurcit, les astres en pâlissent ; / Et la foudre en éclats, qui gronde sous ses pieds, / Semble annoncer la mort aux peuples effrayés.”

39. Voltaire singles out this and other literary devices that interrupt the historical narrative in “Idée de la Hen-riade,” a brief essay preceding the poem.

40. Canto 7, lines 127 – 140 (Voltaire 1970, 517 – 518).

18. Maizony de Lauréal 1837, 78.

19. Maizony de Lauréal 1837, 88. The temple and its paintings: this is the so-called Basilica of Herculaneum, a shrine of the emperor’s cult in which many scenes involving Hercules were painted.

20. Maizony de Lauréal 1837, 101.

21. Maizony de Lauréal 1837, 121, beginning of the canto.

22. Maizony de Lauréal 1837, 131.

23. Maizony de Lauréal 1837, 138.

24. Maizony de Lauréal 1837, 180.

25. Maizony de Lauréal 1837, 255, with a reference to the 1828 excavations in the commentary on p. 433.

26. Dio Cassius, Roman History 66.22.2; see Cary and Foster 1955, 8:305.

27. Maizony’s commentary contains a dense collection of quotations from ancient and modern texts that shows his command of the relevant literature. For a good over-view of Roman evocations see F. Vian, “Gigantes,” in Lexicon iconographicum mythologiae classicae (Zürich, 1981 – ), 4:193 – 196; Patricia A. Johnston, “Volcanoes in Classical Mythology,” in Cultural Responses to the Vol-canic Landscape: The Mediterranean and Beyond, ed. Miriam S. Balmuth et al. (Boston, 2005), 296 – 310, especially 298 – 300; Johannes J. L. Smolenaars, “Earth-quakes and Volcanic Eruptions in Latin Literature: Reflections and Emotional Responses,” in Balmuth et al. 2005, 311 – 329.

28. Jacopo Sannazaro, Arcadia, ch. 12, 28 – 34, in Opere volgari (Bari, 1961), 115 – 116; Jacopo Sannazaro, Arcadia, ed. Francesco Erspamer (Milan, 1990), 218 – 219. García y García 1998, no. 11.918. Transla-tion by Ralph Nash in Jacopo Sannazaro, Arcadia and Piscatorial Eclogues (Detroit, 1966), 137 – 138.

29. See Alfredo Mauro in Sannazaro 1961, 427 – 430. Compare Sogliano 1882, 14 – 15; Leppmann 1966, 59; García y García 1998, 61. Félix Fernández Murga, in

“Pompeya en la literatura española,” Annali dell’Istituto Universitario Orientale: Sezione Romanza 7 (1965): 7, mentions Spanish re-elaborations. Maizony de Lauréal (1837, 311 – 312, 415) quotes Sannazaro, respectively Ecloga 4 of Piscatoriae eclogae and Arcadia.

30. Martin Opitz, Weltliche Poemata, 2 vols. (Frankfurt am Main, 1644), 1:43 – 84. About this edition, which was posthumous although prepared by Opitz, see Erich Trunz in the facsimile edition of this work (Tübingen, 1967), 3* – 9*. The first edition of this poem, dedicated to Duke Johann Christian von Brieg, was published in Breslau in 1633 (Opitz 1967, 18*, 27*). Opitz is not mentioned in the rich chapter on the seventeenth cen-tury in Joachim von der Thüsen, Schönheit und Schrecken der Vulkane: Zur Kulturgeschichte des Vulkanismus (Darmstadt, 2008), 20 – 40. He is also unmentioned in Rosalind H. Williams, Notes on the Underground: An Essay on Technology, Society, and the Imagination, 2nd ed. (Cambridge, MA, 2008).

31. Opitz 1644, 56, 57 (quotations); description of the disaster, 56 – 61. The translations are mine.