K. Ryholt, The Petese Stories II. The Carlsberg Papyri 6/CNI Publications 29. Copenhagen: Museum...

Transcript of K. Ryholt, The Petese Stories II. The Carlsberg Papyri 6/CNI Publications 29. Copenhagen: Museum...

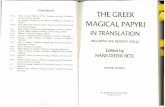

CNI Publications 29

THE CARLSBERG PAPYRI 6

THE PETESE STORIES 11

CP. PETESE 11)

KIM RYHOLT

..

THE CARSTEN NIEBUHR INSTITUTE OF NEAR EASTERN STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF COPENHAGEN 2006 • MUSEUM TUSCULANUM PRESS

CNI Publications 29 The Carlsberg Papyri 6 The Petese Stories 11 © K. Ryholt and Museum Tusculanum Press, 2005 Cover design by Thora Fisker Set in Charter by the author Printed in Denmark by Special-Trykkeriet Viborg als

ISBN 87 635 04049

ISSN 0907-8118 (The Carlsberg Papyri) ISSN 0902-5499 (Carsten Niebuhr Publication)

Editorial board of The Carsten Niebuhr Institute Publications Paul John Frandsen D. T.Potts Aage Westenholz

Editor of The Carlsberg Papyri Kim Ryholt

The publication of this book was made possible by a grant from The Carlsberg Foundation

Published and distributed by Museum Tusculanum Press University of Copenhagen Njalsgade 94 DK-2300 Copenhagen S

www.mtp.dk

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements .................................... page vii Abbreviations and symbols . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .. ix Concordance of fragments .................................. xiii List of plates . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .. xiv Introduction ... . ........................................... 1 Description of the manuscript ................................. 20 Edition of P. Petese Tebt. C .................................. 29

The Blinding of Pharaoh (fragment Cl) ............... . .......... . .. 31 The Prince and the Kalasiris (fragment Cl) ...................... . ... 47 The Crocodile Story (fragment C2) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 59 Fragments mentioning Heliopolis (fragments C3-7) ................... 62 Fragments mentioning Pnebhetep (fragments C8-9) ........... . ....... 66 Unsorted fragments (fragments C10-74) ... . ........................ 69

Edition of P. Petese Tebt. D . ................................. 99 The Rape of Hatmehit (fragment D1) . .. ........................... 101 A Story of Adultery and the Royal Harem (fragment D2) .............. J 08 The Avaricious Merchant (fragments D2-6) . .. . ....... . ... ... . ..... . ] 11 Story featuring a Prophet and His Child{en (fragment D7) ......... .. .. 120 Buried Alive (fragments D7-8) .. . ................................ 122 Story mentioning bartering in Egypt (fragment D9) .................. 128 Unsorted fragments with writing on reverse (fragments DlO-24) . . ...... 130 Unsorted fragments without writing on reverse (fragments D25-51) ..... 137

Additional notes on P. Petese Tebt. A .......................... 147 Bibliography ............................................. 155 Glossary . ............................................... 163 Index of texts cited ........................................ 205 Plates ......... . ........................................ 211

v

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

At the outset of the present volume, it is my pleasant duty to thank the curators in whose collections I have found parts of the papyrus manuscript here published, both for permission to indude their material and for the kind hospitality which they have shown me during my visits. I am particularly grateful to Dr. Isabella Andorlini, Prof. Guido Bastianini, and Prof. Manfredo Manfredi of Istituto Papirologico 'G. Vitelli', Florence, a collection with which I have had a dose and very fruitful collaboration over many years now. I am also very grateful to Prof. Traianos Gagos, Dr. Nikos Litinas and Thorolf Christensen at The University of Michigan Papyrus Collection, Ann Arbor; Dr. Bob Babcock at the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, New Haven; and Dr. Ingeborg Müller at the Papyrussammlung, Ägyptisches Museum, Berlin. The plates at the end of this volume were prepared from a mixture of scans of the Copenhagen, Florence, and Yale fragments, digital photographs of the Michigan fragments, and photographs of the Berlin fragments, the latter made by Margarete Büsing. The images of the individual fragments are reproduced by courtesy of the collections to which they belong (cf. the concordance of fragments, p. xiii).

Aspects of the new Petese Stories were presented at the 3rd Demotic Summer School in Trier, 2001, and the 8th International Conference of Demotic Studies in Würzburg, 2002, and I have benefitted from comments and discussions on both occasions. In addition I would like to thank Frank Feder, Hans-Werner Fischer-EIfert, Richard Jasnow, Paul John Frandsen, Cary Martin, Jürgen Osing, Joachim Quack, and Günter Vittmann for invaluable help and suggestions, and my former student Rikke Jensen for checking the references to Story of Petese in the index of citations. I am particular indebted to Cary Martin for also correcting my English.

In condusion I should like to express my deep gratitude to The Carlsberg Foundation for generously providing all the necessary funds for my research travel and the publication of the present volume.

vii

Kim Ryholt August 2005

ABBREVIATIONS AND SYMBOLS

Full details of all publications eited below are provided in the Bibliography. The abbreviations for journals used in the Bibliography follow W. Helck und W. Westendorf Ceds.), Lexikon der Ägyptologie, Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 1975-92.

Copt. Dict.

Copt. Etym. Dict.

Glossar

LSJ Story of Petese

Wb.

TITLES OF BOOKS

Crum, A Coptic Dictionary.

Cerny, Coptic Etymological Dictionary.

Erichsen, Demotisches Glossar.

Liddell, Scott, and Jones, A Greek-English Lexicon.

Ryholt, The Story of Petese, Son of Pe te tu m, and Seventy Other

Good and Bad Stories.

Erman and Grapow, Wörterbuch der ägyptischen Sprache.

NAMES AND DESIGNATIONS OF TEXTS

The following list provides references to published texts that are eited more than on ce and brief descriptions of eited texts that have not yet been published. As it will be clear from the list, the rich but mostly still unpublished literary material from the Tebtunis temple library in the Papyrus Carlsberg Collection has been extensively used in the preparation of the present work. There are fragments of most of these manuscripts in other collections, but these are gene rally rather sm all and I have not found it necessary to refer to them. CA single exception is P. Carlsberg 422.) For this reason, and because the number of identified fragments in other collections has grown so large over the years, I have deeided not to make a note of the joins in the present volume although I did so in Story of Petese. In the case of the many unpublished texts whose fragments have still to be sorted and arranged, it has naturally not been possible to eite them by fragment, column, and line numbers.

1. Demotic Amasis and the Sailor P. BibI. Nat. 215, verso, coI. a: Spiegelberg, Die sogenannte

demotische Chronik, pp. 26-8. Recent translation with further literature: Ritner, in The Literature of Ancient Egype Ced. Simpson), pp. 450-2.

ix

Demotic Chronicle

Harpist Inaros Epic

ABBREVIATIONS AND SYMBOLS

P. BibI. Nat. 215, recte: Spiegelberg, Die sogenannte demotische

Chronik. Recent translation with further literature: Felber, in Apokalyptik und Ägypten, pp. 65-111. P. Vienna KM 3877: Thissen, Der verkommene Harfenspieler.

Unpublished narrative preserved in several manuscripts, including P. Carlsberg 80. Preliminary description: Ryholt, in Studies Larsen, pp. 492-5, with further references.

Khamwase and Naneferkaptah P. Cairo CG 30646: Griffith, Stories of the High Priests of

Khamwase and Siosiris Krugtext A-C Onch-Sheshonqy

Onch-Sheshonqy Tebt.

P. Berlin P 13588 P. Berlin P 15531 P. Carlsberg 2 P. Carlsberg 9

P. Carlsberg 12 P. Carlsberg 14 P. Carlsberg 69

P. Carlsberg 75 P. Carlsberg 80

P. Carlsberg 85

P. Carlsberg 129

P. Carlsberg 158

P. Carlsberg 159 P. Carlsberg 205

Memphis. P. BM 10822: Griffith, Stories of the High Priests of Memphis.

w. Spiegelberg, Demotische Texte auf Krügen. P. BM 10508: Glanville, The Instructions of 'Onchsheshonqy, and re-edition of the introduction in Smith, Serapis 6 (1980), pp. 133-56. Recent translation with further literature : Ritner, in The Literature of Ancient Egypt3 (ed. Simpson), pp. 497-529. P. Carlsberg 304 + PSI inv. D 5 + P. CtYBR 4512 + P. Berlin P 30489: Ryholt, in The Carlsberg Papyri 3, pp. 113-43. Erichsen, Eine neue demotische Erzählung. Unpublished copy of the Book of Thoth. Volten, Kopenhagener Texte zum demotischen Weisheitsbuch. Neugebauer and Parker, Egyptian Astronomical Texts III, pp. 220-5, pI. 65. Volten, Archfv Orientcilni 20 (1952), pp. 496-508. Volten, Demotische Traumdeutung. Unpublished literary text from the Tebtunis temple library. Preliminary descriptions in Zauzich, in The Carlsberg Papyri 1, p. 6, and Ryholt and Quack, Papyrus 16.1 (1996), pp. 21-23 (in Danish). Unpublished narrative from the Tebtunis temple library. Unpublished narrative from the Tebtunis temple library; a copy of The Inaros Epic, q.v. Formerly designated P. Tebt. XI. Unpublished narrative from the Tebtunis temple library. Preliminary description: Ryholt, in Studies Larsen, pp. 500-2. Unpublished narrative from the Tebtunis temple library. Formerly designated P. Tebt. VIII. Unpublished mythological narrative from the Tebtunis temple library. Unpublished narrative from the Tebtunis temple library. Unpublished narrative from the Tebtunis temple library; an Inaros story. Preliminary descriptions in Volten, Archfv Orientcilni

19 (1951) , p. 73, and idem, in Akten des VIII. Int. Kongr. für Papyrologie, p. 150. Formerly designated P. Tebt. XII.

x

P. Carlsberg 207

ABBREVIATIONS AND SYMBOLS

Tait, in The CarLsberg Papyri 1, pp. 19-46, with additional readings in Quack and Ryholt, in The CarLsberg Papyri 3, pp. 141-63.

P. Carlsberg 230 Tait, in The CarLsberg Papyri 1, pp. 47-92. P. Carlsberg 399 + PSI inv. D 17 + P. Tebt. Tait 13 Quack, in Apokalyptik und Ägypten,

pp. 253-74. P. Carlsberg 400

P. Carlsberg 412

Unpublished narrative from the Tebtunis temple library. Preliminary description: Ryholt, in Studies Larsen, pp. 504-5. Unpublished narrative from the Tebtunis temple library. Preliminary description by Widmer, in Acts of the Seventh Int. Conf of Demotic Studies, pp. 387-93.

P. Carlsberg 421 Unpublished narrative from the Tebtunis temple library. P. Carlsberg 422 + PSI inv. D 11 + Location unknown Unpublished narrative from

P. Carlsberg 448 P. Carlsberg 456

P. Carlsberg 460

P. Carlsberg 465 P. Carlsberg 470 P. Carlsberg 483

P. Carlsberg 562 P. Carlsberg 606 P. Carlsberg 614 P. CtYBR422 P. Dem. Saq. 1-27 P.Insinger

P.Krall

P. Louvre 2377 verso P. Mag. LL.

P. Mythus Leiden

P. Mythus Lille

P. Rylands 9

the Tebtunis temple library. Preliminary description: Ryholt, in Acts of the Seventh Int. Conf of Demotic Studies, pp. 361-6. Unpublished narrative from the Tebtunis temple library. Ryholt, JEA 84 (1998), pp. 151-69. Formerly designated P. Tebt. IX. Unpublished mythological narrative from the Tebtunis temple library. Unpublished narrative from the Tebtunis temple library. Unpublished narrative of unknown provenance. Unpublished narrative from the Tebtunis temple library; a parallel to P. Spiegelberg. Formerly designated P. Tebt. III. Ryholt, ZPE 122 (1998), pp. 197-200. Unpublished narrative from the Tebtunis temple library. Unpublished narrative from the Tebtunis temple library. Unpublished narrative from the Tebtunis temple library. Smith and Tait, Saqqara Demotic Papyri I.

Lexa, Papyrus Insinger. More recent translation with further literature: Lichtheim, Ancient EgyptianLiterature 111, pp. 184-217. P. Vindob. 6521-6609: Hoffrnann, Der Kampf um den Panzer des Inaros.

Williams, in Studies Hughes, pp. 264-266. P. Lugd. Bat. J 383 + P. BM 10070: Griffith and Thompson, The

Demotic Magical Papyrus of London and Leiden. P. Dem. Lugd. Bat. J 384: Spiegelberg, Der ägyptische Mythus vom Sonnenauge.

P. dem. Lille 31: de Cenival, CRIPEL 7 (1985), pp. 95-115; idem, CRIPEL 9 (1987), pp. 55-70. Griffith, Catalogue of the Demotic Papyri in the John Rylands

Library; Vittmann, Der demotische Papyrus Rylands 9.

xi

P. Spiegelberg

P. Tebt. Tait 1-53 P. Vindob. D 6321: Myth of the Sun's Eye

Drade of the Lamb

Petekhons and Sarpot

ABBREVIATIONS AND SYMBOLS

Spiegelberg, Der Sagenkreis des Königs Petubastis. The beginning of the papyrus is reconstructed by Hoffmann, in Hundred-Gated Thebes, pp. 43-60, and idem, Enchoria 22 (1995), pp. 30-9. Tait, Papyri from Tebtunis in Egyptian and in Greek. Reymond, FromAncient Egyptian Hermetic Writings, pp. 111-6. Preserved in several manuscripts, including P. Mythus Leiden and P. Mythus Lille, q.v. A concise description is Smith, IÄ 5

(1984), cols. 1082-7. P. Vindob. D 10000: Zauzich, in Festschrift Papyrus Erzherzog Rainer, pp. 165-74. P. Vindob. 6165 and P. Vindob. 6165a: Hoffmann, Ägypter und Amazonen.

The Swallow and the Sea Pot Berlin P 12845 = Krugtext A, 16-23: Collombert, in Acts of the Seventh Int. Conf Dem. Studies, p. 59-76.

2. Hieratic Merire and Sisobk Two Brothers

[ ]

[[ ]]

( ) r 1

{ }

( )

« »

P. Vandier: Posener, Le papyrus Vandier. P. BM 10183 (P. D'Orbiney): Gardiner, Late-Egyptian Stories, pp. 9-29. Recent translation: Wente, in The Literature of Ancient Egypt3 (ed. Simpson), pp. 80-90.

SYMBOLS

Restorations by the present writer

Words or signs erased by the ancient scribe

Words supplied by the present writer to make the sense clear

Damaged words or signs the reading of which is not quite certain

Words or signs regarded as incorrect

Words or signs omitted by the ancient scribe

Emendations by the present writer

Words or signs added above the line by the ancient scribe

Words or signs added below the line by the ancient scribe

Words or signs struck out by the ancient scribe

xii

CONCORDANCEOFFRAGMENTS

P. Petese Tebt. C

Location PSI inv. D 8:

P. Carlsberg 324:

P. Berlin P 14.467(e): P. Berlin P 30.022: P. Mich. 6391(g): P. Mich. 6397(r):

P. Petese Tebt. D

Location PSI inv. D 9:

P. Carls berg 394: P. CtYBR 889: P. CtYBR 4100/5: P. CtYBR 4947/3:

Fragment number 1 (part; 9 frs.), 2 (2 frs.), 3 (2 frs.), 4-9, 10 (2 frs.), 12-18, 19 (2 frs.), 21 (2 frs.), 22 (2 frs.), 23, 25 (2 frs.), 26, 28, 30-32, 36-38, 40-42, 47, 49-53,58-59, 61-64, 66, 68, 71-72, 74. 1 (part; 28 frs.), 11, 24, 27, 33-35, 39, 43-44, 46, 48, 54-57, 60, 65, 67, 69-70, 73 29 1 (part; 1 fr.) 45 20

Fragment number 2 (8 frs.), 3, (2 frs.), 4-6, 7 (part; 1 fr.), 8-12, 14, 16-23, 25-26, 28, 30-32, 34-35, 37-40, 42-49, 51 1 (3 frs.), 7 (part; 4 frs.), 13, 15,24,27,29, 33,41 50 13 36

P. Petese Tebt. A, new fragments

Location P. Carlsberg 165

Fragment number 19-26

xiii

LIST OF PLATES

P. Petese Tebt. C

PI. 1 PI. 2 PI. 3 PI. 4 PI. 5 PI. 6 PI. 7 PI. 8 PI. 9 PI. 10 PI. 11

Fragment Cl, overview Fragment Cl, I Fragment Cl, 11 Fragment Cl, 111 Fragments C2-7 Fragments C8-18 Fragments C19-22 Fragments C23-32 Fragments C33-47 Fragments C48-67 Fragments C6 7 -74

P. Petese Tebt. D

PI. 12 PI. 13 PI. 14 PI. 15 PI. 16 PI. 17 PI. 18 PI. 19 PI. 20 PI. 21

.. Fragment D1 Fragment D2, overview Fragment D2, 1-11 Fragments D2, III, and D3-6 Fragment D7, I Fragment D7, 11, and D8 Fragments D9-12 Fragments D13-24 Fragments D25-35 Fragments D36-51

Example of the account on revese of P. Petese lebt. CD

PI. 22 Fragment Cl, 111, verso

P. Petese Tebt. A, new fragments

PI. 11 Fragments A19-26, lost fragment of column 2, and new fragment of column 4

xiv

INTRODUCTION

Five years ago I published the fourth volume of the Carlsberg Papyri, entitled The Story of

Petese san of Petetum and Seventy Gther Good and Bad Stories. This volume contained the edition of the remains of three manuscripts inscribed with a lengthy literary work which I now refer to simply as The Petese Stories. Less than a year after this publication, it became clear to me that a further group of mostly very small fragments in fact preserved other parts of the same text and, moreover, that the manuscript to which they belong had all the indications of being a continuation and companion to the main manuscript, P. Petese Tebt. A. I It is regrettable that the new material had not been identified before the first volume was published, since it sheds considerable light on the nature of the text as a whole. It would also have allowed a better understanding of the main manuscript and saved me from a number of incorrect conclusions.

The new manuscript edited he re is in a sad state of preservation. It consists of a great number of small fragments which probably represent less than 10% of the original. It has been a painstaking process to make sense of the fragments, and the most time-consuming task has been the attempt to join fragments into larger pieces and the reading of traces of damaged signs in order to squeeze as much information as possible out of what remains. Despite the fragmentary state of the manuscrjpt and the far too many hours spent onjoins and traces, I have found the edition of the manuscript worth the effort. It preserves aseries of further short stories, out of the seventy that the work is said to have comprised, and these have advanced the understanding of the complex composition immensely. I think it is safe to say that the brief remarks on the status of The Petese Stories made in the first edition (Story of Petese, p. 91) were not far from the point.

Brief Description of the Petese Stories

The Petese Stories are a collection of stories about the virtues and vices of women. The overall structural pattern is very similar to the Arabian Nights. A frame story forms the introduction as weIl as the fabric into which a long series of shorter tales are woven. It is not just a story in its own right, but also explains how and why the work as a whole was

1. Fragments of the new manuscript had in fact already been cited several times in Story of Petese, and it was noted both that P. Carlsberg 324 + PSI inv. D 8 was written by the same scribe as P. Pe te se Tebt. A (Story of Petese, p. 9) and that there were certain interesting parallels in P. Carlsberg 394 + PSI inv. D 9, i.e. the phrase sbfs~m.t (Story ofPetese, pp. 23,72, referring to fragment D25) and the baboon addressing Sakhminofret (Story of Petese, p. 72, note 54, referring to fragment D7).

Preliminary re ports on the new manuscript have been published in Papyrus 19.2 (1999), and Carlsbergfondet Arsskrift 2003, pp. 56-7, the latter including a color photograph of fragment D1. Both re ports are in Danish.

1

INTRODUCTION

composed. In the light of the new manuscript published here, the discussion of the frame story published in the first volume can be improved in several respects, and for this reason an updated outline is presented here.2

The Frame Story

The main characters of the frame story are Petese, prophet of Atum in the temple of Heliopolis, and his wife Sakhminofret. The beginning is lost, and the extant parts commence in the middle of a discussion between Petese and a ghost. Petese wishes to learn how long he has left to live, and after some time he is able, through the use of magie, to force the ghost to reveal the answer. He is told that he has only forty days left, and that he has already been entered into the day-book before the lord of the gods, Le. the list of those who are about to enter the realm of the dead. It is not clear why Petese suddenly faces death. He returns horne in a sad state of mind. His wife asks hirn what is wrong, but he decides not to tell her. At this point he apparently makes adecision to put his worries aside and to spend the remaining days of his life 'making holiday' with his wife.

Things turn out somewhat different, at least to begin with. Petese contacts his fellow priests at the temple of Heliopolis, and refers to hidden books in the temple and its prestige. He then asks for five hundred silver pieces from the treasuries of the sun-god, whieh was a considerable sum of money. Just possibly he is proposing to enhance the renown of the temple by revealing or explaining a number of books whieh, it may be assumed, contain arcane knowledge. The ~ concept of rewards granted in return for knowledge about ancient and arcane writings is attested in two other contemporary texts. One in fact seems to concern our Petese, and it relates how a pharaoh once summoned and rewarded hirn after he had successfully deciphered an ancient book on astrology that had been discovered in the temple of Heliopolis.3 The other is Khamwase and Naneferkaptah, 111.10-20, where a priest demands one hundred silver pieces to reveal the whereabouts of the book of Thoth.

The priests all agree to Petese's proposal except for Hareus son of Tjainefer, who is the lesonis at the temple. Petese returns horne empty-handed and decides to force his will upon the lesonis. Once again this entails the use of magie. He creates a cat and a falcon out of wax, and somehow manages to intimidate Hareus into submission with the aid of these creatures. The lesonis personally brings five hundred silver pieces to Petese and apologizes, and he promises to provide hirn with yet another five hundred silver pieces from the treasuries of the sun-god.

A very damaged section follows whieh mentions books and preparations for a burial. In view of the context, we may assume that Petese here lives up to his end of the bargain concerning the aforementioned books, and that the preparations for his burial has begun. These preparations continue where the text again becomes more coherent. Petese once more uses his magical abilities and creates out of wax the personnel necessary to

2. Story of Petese, pp. 69-83. The main textual improvements are discussed pp. 147-51 below.

3. P. CtYBR 422; see description pp. 13-5 below.

2

INTRODUCTION

undertake the funerary rites. First he creates an exorcist (?) and a lector-priest who are given assignments.4 He then creates another four persons, including a scribe of the god's book and a pastophoros. These are handed certain books, presumably of a funerary nature, and it is told that they did something comparable to what is done for a pharaoh, nothing being left undone.

We now reach a crucial part of the tale. This describes why and how The Petese Stories were composed, and it thus essentially turns the story into a tale of its own creation. Having settled for now the affairs relating to his funeral, Petese creates two baboons out of wax and brings them to life. He orders them to do something daily that will result in 'thirty-five stories of vice and thirty-five of virtue'. The exact wording of the assignment is lost, but the purpose is clearly for the baboons to seek out and collect the stories in question. The two baboons are then handed the usual scribal tools, papyrus and palette, that they may write down the stories. There is no doubt that the stories of vice and virtue refer to the many short tales that follow, since the latter are explicitly classified as 'stories of scom of women' and 'stories of praise of women'.

The literary work which the baboons are ordered to compose is specifically referred to as 'books which will be found after hirn in another time'. This indicates that the purpose of the compilation was to represent some form of literary testament in honor of Petese, a manner of perpetuating his memory. The funerary symbolism of the total number of stories, seventy, is evident; seventy days was the ideal time it took to perform an embalmment. The explicitly stated intention that the work might be discovered after Petese's death, in another time, is significant. We have here a clear allusion to the discovery of ancient writings in temples, which was a topos in the introduction to religious, scientific and didactic texts. It is in this respect noteworthy that Petese hirnself is also attested in relation to this topos. In another text from the temple library, he is said to be the interpreter of an ancient, scientific treatise written by Imhotep that had been discovered in the temple of Heliopolis. 5 His aim with the compilation of The Petese Stories may therefore be seen as adesire to be placed on a par with Imhotep, the greatest sage of all in Egyptian literary tradition. The actual author of Petese could scarcely have imagined that this work would in fact be rediscovered after more than two millennia which, by a curious coincidence, is about the same length of time that separates Imhotep and Petese.

Having made all the preparations for his burial and his literary testament, it is told that Petese spent 'the rest of the forty days making holiday with Sakhminofret, his wife, and he did everything which he pleased'. The fortieth day arrives, and Petese reminds his wife to do what he has told her. He then apparently dies. The next day Sakhminofret goes to his storehouse, and she bums myrrh, frankincense, and kyphi on the brazier, as one does for the sun-god. She prays that he will save her husband, and the sun-god then manifests hirnself and speaks to her with the speech of Petese.6

4. For the possible reading ssr, 'exorcist', see p. 15l.

5. P. CtYBR 422; see description pp. 13-5 below.

6. The manner in which Sakhminofret makes contact with the divine should perhaps be understood as an act of 'divine consultation' (ph-ntr), a term that occurs again in two ofthe short stories here edited, cf. fragments C21, II.x+6, and D2, II.2. Significantly it is also a woman who performs the p~-ntr in the latter story.

3

INTRODUCTION

Here the frame story breaks off, and the rest of the part that preceded the embedded stories is lost. It is clear, however, that the frame story continued in very brief installments between the numerous embedded stories, but virtually nothing of these installments is preserved.

The Embedding of the Short Stories

The main part of the frame story is followed by the seventy short stories on the virtues and vices of women. The specific contents of the individual stories will not be discussed here; for these I refer to the commentaries. The following will instead concentrate on the manner in which they are embedded and their nature.

To judge from the extant fragments, most - if not all - of the short stories are introduced and told to Sakhminofret by a baboon.7 This is highly significant. Baboons were regarded as the ideal worshiper of the sun because of their behavior in the morning when they dance and chant (so the Egyptian point of view) at the coming of the first sun-rays, and their utterances were believed to represent the divine language.8 For this reason the baboon was closely associated with the cult of the sun, and is well-attested as a manifestation of the sun-god. In effect, it may therefore be the sun-god hirnself who speaks to Sakhminofret. This would make excellent sense, since Sakhminofret presents offerings and prays to the sun-god concerning her husband Petese in the final part of the main story. The sun-god answers her with the 'speech' of her husband, which may indicate a familiar human voice, and the numerous stories which follow may be interpreted as the reply or response to her prayer. As in the case of The Myth of the Sun's Eye, one or more of the stories might then contain a moral which inspires or enables Sakhminofret to accomplish what Petese desires of her.9 They would, in other words, lead to the eventual resurrection of Petese or some other spectacular outcome.

At the same time the baboon which tells the stories must surely be identical with the baboons created by Petese earlier on with the explicit purpose of committing the stories into writing. 10 This demonstrates a considerable degree of complexity since Petese, with this interpretation, has clearly anticipated events. He has created the baboons, through which the sun-god will manifest hirnself, as well as the stories with which the sun-god will provide Sakhminofret with an answer. This could also explain why the sun-god is said to speak to Sakhminofret specifically with the speech of Petese; what the sun-god relates to

7. The narrator is eonsistently referred to as 'the baboon' exeept onee, in P. Petese Tebt. A, '8'.4, where he is deseribed as is a [ ... ] ntr, '". of god'. It eannot be excluded that this might still be a referenee to the baboon by some other name or epithet.

8. The eoneept of the language of the baboons is diseussed by te Velde, in Essays van Voss, pp. 129·37. For the divine language in general, also with referenee to the baboons, see Hornung, Eranos 4 (1996), pp. 159-86.

9. The relationship between The Petese Stories and The Myth ofthe Sun's Eye is explored in more detail below, pp. 9·10.

10. The ereation of a pair of baboons, rather than just one, presumably re fleets the duality of the stories themselves, the implieation being that one baboon would be responsible for the stories of virtue and another for the stories of viee. The baboon that teIls the stories may therefore be representative of both, or perhaps the two baboons take turns.

4

INTRODUCTION

her through his manifestation as a baboon is the stories that are Petese's own creation and therefore, in effect, his words. 11

Each of the embedded stories is introduced by the words 'The baboon said: 0 my sister Sakhminofret' .12 The baboon then states the number of the story that follows and the category to which it belongs. Each story seems to have had an individual number, although only three are actually preserved. The systematization of the contents of larger literary texts seems typical of Egyptian literature from Roman times, although it might have been introduced at an earlier date. Other contemporary examples of numbered contents include the maxims in the Insinger wisdom text and the herbs in the herbai P. Carlsberg 230. The purpose of the numbering may have been an attempt to protect the integrity of the works in question.

The stories are divided into two categories, stories of scorn of women (srjy n sb! s~m. t) and stories of praise of women (srjy n ~s s~m. t) .13 The antithetical arrangement of sb! and ~s in relation to women is also attested in Onch-Sheshonqy, XXII.lOf, where m-ir rjd p? bft s~m.t mr.l, 'Do not mention the scorn of a beloved woman', is followed by m-ir rjd p? ~s s~m.t mst,J,

'Do not mention the praise of ahated woman'. The two terms are also found as elements in titles in The Myth oi the Sun's Eye. The two titles in question read n? sm.w n bsf, 'the small ones of scorn', and n? sm.w (n) ~s, 'the sm all ones ofpraise' (P. Mythus Leiden, V.21, 29), and form part of aseries formed on the pattern n? bm.w n ... , 'the small .. .'.14 Again they seem to form an antithetical couplet with n? sm.w (n) ~s following n? sm.w nbsfIS

After the brief introduction the story itself follows. It is concluded with the same words as it was introduced, Le. 'The baboon said: 0 my sister Sakhminofret'. As far as I am able to reconstruct, this is usually followed by the statement 'this is the story of X' (p? srjy n X p?y) ,

which corresponds more or less to a title. Unfortunately the latter is never preserved intact. Before the next story, we return briefly to the frame story. This section is also nowhere

preserved intact. Apparently it is mostly just related that the story for the following day (pa rsty) was completed, and that Sakhminofret, the next morning, either 'came according to her daily habit' or 'acted according to her daily habit'. This indicates that Petese's wife visits the baboon on a daily basis. Thereafter a new story follows.

The stories of praise and scorn seem to alternate, which is not surprising since there is an equal number of each. Two stories whose numbers are known further indicate that the unevenly numbered ones belong to the former category and the unevenly to the latter. 16

11. It is perhaps not without significance that the text uses the word ~spy, Copt. ",cne:, 'language, speech', rather than bnv, Copt. ,pooy, 'voice, sound'.

12. ünce, in fragment CID, x+6, the text reads simply t~ sn.t instead of t~y;y sn.t. This is either amistake or a slight variation.

13. The implication of the terms 'praise of women' and 'scorn of women' is discussed below.

14. A whole series of titles on this pattern are preserved in the table of contents of the Lilie version of the myth; see discussion by de Cenival, CRIPEL 11 (1989), pp. 141-6. A small unpublished P. Carlsberg fragment seems to preserve part of the same table of contents, but it is evidently from another manuscript.

15. Spiegelberg, Mythus vom Sonnenauge, p. 21, and Cenival, Mythe de l'oeil du soleil, p. 15; idem, CRIPEL 11 (1989), p. 143, understand ~s as 'Leider', 'couplets', and bsfas 'Tadel' and 'ripostes'.

16. The 18th story concludes with a women being thrown out of the royal harem, suggesting that it was a story of scorn of women. The following, 19th story concerns a greedy merchant and this story is explicitly said to be a story of praise of women.

5

INTRODUCTION

Classification of Story

Al The baboon said: My sister, Sakhminofret! (}d p3 "n t3y=y sn.t Sbmy.t-njr.t

A2 a. The x'th story; it is the story of scorn of wornen p3 sgy ml}-x p3 sgy n sb[ sl}m.t p3y

b. The x'th story; it is the story of praise of wornen p3 sgy ml}-xp3 sgy n I}s sl}m.t p3y

Introduction of Story

B The baboon said: My sister, Sakhminofret! gd p3 "n t3y=y sn.t Sbmy.t-nfr.t

[The Embedded Story] ,

Conclusion of Story

Cl The baboon said: My sister, Sakhminofret! gd p3 "n t3y=y sn.t Sbmy.t-nfr.t

C2 This was the story of [keyword] p3 sgy n [keyword] p3y

Brief Return to the Frame Story

DI Completion of next day's story, passing of time (various phrased)

D2 Sakhminofret carne according to her daily habit. Sbmy.t-nfr.t iw r-lJ p3y=s smt mny

I var. She acted according to her daily habit. var. ir=s r-lJ p3y=s smt mny

Fig. 1. The Ernbedding of the Short Stories.

The Nature of The Petese Stories

The Petese Stories is a cornpilation of short stories concerning the virtues and vices of wornen or, in other words, a rnoralistic cornposition. The nature of the stories is explicitly stated within the text itself. The introduction to the stories as a whole, the frame story, relates that the work was to consist of thirty-five stories of virtue (mnb) and thirty-five of vice (wyhy).17 Moreover, as I have already rnentioned, the brief introduction to each individual story contains a dassification scherne according to which every story is either categorized as a 'story of praise of wornen' (sgy n bs n sbm. t) or a 'story of scorn of wornen' (sgy n sbfn sbm.t) . The parallelisrn between virtue and praise on one hand, and vice and scorn on the other, is dear.

The concepts mnb and wyhy are crucial in relation to The Petese Stories, and since their basic sense is not precisely defined by the dictionaries, a few rernarks rnay be offered here. 18 The adjective mnb designates the quality of living entirely up to a purpose, while wyhy, its antonym, designates the failure to do so. The words rnay be used in reference to beings as weIl as objects and ideas. Exarnples of mnb are abundant, particularly with reference to the king and his plans as part of the royal ideology. An excellent exarnple of dernotic why occurs in relation to a father who has failed to take care of his children and

17. P. Pe te se Tebt. A, '5'.9

18. Cf. also the discussion of the adjective mnb in the description of officials during the 18th Dynasty in Guksch, Königsdienst, pp. 78-84, who translates it with 'Tüchtigkeit'. This rendering is highly contextual.

6

INTRODUCTION

mistreats them. 19 Like many other concepts, they are difficult to translate by a single word. To some extent mnb corresponds to 'good' in the sense of 'having the right or desired qualities' and wyhy to 'bad' in the sense 'inadequate, defective'.20 The concepts are often used in a moral sense when applied to people. In this context, mnb can mostly be translated 'virtuous' or 'perfect' and why by 'wicked' or 'incompetent', while the nominal forms may be rendered as 'virtue' and 'vice' respectively.21 The moral application of the concepts is weIl illustrated by reference to the judgement of the dead, where the virtues (mnb.w) of the deceased are weighed against the vices (why.W).22 Here mnb.w and why.w

describe instances of having lived correctly and having failed to do so respectively. The concepts are also used in the wisdom literature, and Onch-Sheshonqy explicitly stresses the antithesis between mnb and why on two occasions.23

The description of the subject matter as stories about the virtues and vices of women is confirmed by the actual contents of the extant fragments which are centered on the behavior of women in various situations. Two stories even make direct use of the terms mnb and wyhy,

the former in relation to the difficulty of finding a virtuous woman (fragment Cl, II), while the latter unfortunately occurs in a damaged context (fragment D7, I).

Having dassified The Petese Stories as compilation of stories about the virtues and vices of women, the question presents itself exactly how women are portrayed and what aspects of their lives receive special focus. Unfortunately neither a detailed nor even a general assessment is possible because of the exceedingly fragmentary state of the text, and I shall therefore only venture to make a few remarks. It is weIl-known that Egypt was no stranger to misogynistic literat ure of which a prime example is the tale of Two Brothers. The possibility that Petese might be dassified as such can be rejected with some certainty. The compilation indudes material about both the vices and virtues of women and, significantly, precisely the same number of stories are devoted to each of the two aspects. If anything, the larger frame story causes the positive aspect of women to dominate, since the wife of Petese can hardly be described as other than a virtuous woman, and since she makes an appearance between each of the short stories, apparently fulfilling her role towards her husband.

As to the aspects of women described in the stories, it is perhaps not surprising that sexuality plays a significant role and perhaps even a dominant one. Women commit adultery, and not just wives, but also a mother, a single member of the royal harem or even an entire royal harem consisting of forty women. Other women are victims of sexual aggression. Several times the exceptional beauty of a woman is described, but to what extent it has actual significance for the story in question is never quite dear. The

19. Letter to the gods (P. BM EA 10845) published by Hughes, in Studies Wilson, pp. 43-56, cf. also Migahid, Demotische Briefe an Götter, I, pp. 115-21.

20. Definitions of good and bad quoted from The Oxford Concise Dictionary.

21. The two terms are not discussion in Lichtheim, Moral Values, apart from abrief mention of mnb (pp. 83-4).

22. Cf. Khamwase and Siosiris, 1I.6ff, as well as the mummy-board BM EA 35464, lines 24ff, published by Vittmann, ZÄs 117 (1990), pp. 79-88. See also Khamwase and Siosiris, 1I.2H.

23. Onch-Sheshonqy, XVIII .5, XXI .12. Interpretations of the two passages vary.

7

INTRODUCTION

dedieation of women towards their husbands is described in two stories, while a third describes the very opposite, a husband who has fallen in love with another and attempts to murder his wife. Perhaps by coincidence other female roles, such as that of the mother towards her children or the wise or foolish woman, do not seem to be attested. These are topies that are covered in the portrayal of women in the contemporary wisdom texts, but one should not necessarily expect a correlation between different literary genres or even individual texts of the same genre.24 However this may be, it is worth nothing that while the present state of The Petese Stories only allows us to draw a sketchy image of its actual contents, these seem to confirm the impression that women are presented in a balanced manner with equal focus on the wicked and the virtuous.

The Petese Stories and Early Egyptian Narrative Literature

The Petese Stories was based on a literary tradition that goes back two millennia. Although the extant Middle and Late Egyptian material is relatively limited, its relationship with earlier narrative literature can be seen to be everything but vague. Above all, Petese

displays striking similarities to The Tale of the Court of King Cheops, whieh was written in Middle Egyptian and composed no later than the 16th century Be. The similarities concern structure as weIl as content. Both compositions are frame stories, employing the literary device of embedding shorter tales within a main story. Moreover, adultery, magie, and prodigal children are prominent topics in Cheops' Court as weIl as Petese, while neither shows much interest in physieal strength and soldiery.25

Another property that Petese shares with some of the earliest Egyptian literature is that it relates how it came to be committed to writing and thus comments upon its own creation. The same notable feature is found in The Prophecy of Neferti and The Tale of the

Eloquent Peasant. 26 In both these texts it is the will of the king that they should be recorded in writing; the king gives explicit orders for the eloquent speech of the peasant to be recorded, while in the case of the prophecy he even re cords it personally. Representations of writing kings are exceedingly rare, whieh implies and emphasizes the importance of the prophecy and hence of the text as a whole.27 We are clearly dealing with a literary device aimed at enhancing the status of the texts, the message being that these texts were sanctioned by the king. At the same time the novelty of literature in manuscript form may also have been feIt to require comment in these two early texts.

24. For the representation of women in demotic wisdom literature, see now the detailed investigation by Dieleman, SAK 25 (1998), pp. 7-46.

25. A duel is described in Petese, the story of The Prince and the Kalasiris, but it is related in the briefest possible mann er which marks a striking contrast to the much more elaborate descriptions found in the contemporary Inaros stories and other related literature.

26. For translations and comments on these two texts, see Parkinson, The Tale of Sinuhe, pp. 54·88, 131-43, and idem, Poetry and Culrure, pp. 168-82, 193-200.

27. The lack of such representations of the king in visual art is noted by Morenz, Beiträge zur Schriftlichkeitskultur, p. 25.

8

INTRODUCTION

The Relationship between The Petese Stories and The Myth of the Sun's Eye

The dosest contemporary parallel to The Petese Stories, as far as the literary structure is concerned, is The Myth of the Sun's Eye. Like a number of other demotic stories, it too shares the literary device of a frame story, but it is only in Petese and The Myth that the individual stories or elements have explicit designations.28 The similarities between the two compositions, which both enjoyed a considerable popularity, is hardly accidental. On the contrary, there are indications that Petese to some extant was deliberately modeled after the myth. Some similarities with the myth have already been described above, but they may go even deeper.

In The Myth of the Sun's Eye, Thoth tries to persuade the daughter or eye of the sun-god to return horne to Egypt which she has abandoned, and along with his arguments he teIls a number of stories. Thoth appears in the guise of a 'little dog ape' (bm n wns gwj), Le. a cynocephalus, while the goddess is mostly designated 'the Ethiopian cat' (imy.t iks.t).

Richard Jasnow has made the very interesting suggestion to me that Sakhminofret and the baboon, who are the main characters in the brief interludes between the stories in the manuscript published here, might be an allusion to the two main characters of the myth. The baboon would represent Thoth, while Sakhminofret plays the role of the daughter or eye of the sun-god. Inasmuch as the mood of the goddess oscillates between joy and rage, the name Sakhminofret ('the good Sakhmet') could even be taken to indicate that she represents the peaceful aspect of the character. With this interpretation, it is conceivable that the baboon plays the same role vis-a-vis Sakhminofret as Thoth does in relation to the daughter of the sun-god, Le. that he tries to persuade her to do what is right in relation to some matter. Perhaps at some point during the course of the story, Sakhminofret is on the verge of abandoning the tasks that her husband Petese has laid upon her, and on which he is apparently dependent, and the baboon hopes to coax her into fulfilling them by telling her stories suitable for that purpose. Just as Thoth succeeds in persuading the goddess to do what is right, it might then be assumed that the baboon manages to convey a specific message to Sakhminofret as weIl.

The third character in the constellation of the myth is the sun-god hirnself who is absent during Thoth's attempt to persuade the goddess. In Petese, this role is assumed by Petese. Petese plays a role at the beginning of the text, but once the main story is over and the short stories begin, we hear little or nothing more about hirn. It is, however, on his behalf that the baboon teIls the stories, just as Thoth is the messenger of the sun-god in the myth. The association is further supported by the fact that Petese is actually a prophet of the sungod, and at one point the two merge in the sense that the sun-god speaks to Sakhminofret with the speech of Petese.

Finally, The Petese Stories and The Myth ofthe Sun's Eye are both attested in the Tebtunis temple library, where each is represented by several papyrL29 Furthermore, parts of both

28. For the titles in The Myth ofthe Sun's Eye, see de Cenival, CRlPEL 11 (1989), pp. 141-6.

29. No less than six papyri preserve parts of The Myth of the Sun's Eye, while three preserve parts of The Petese Stories.

9

INTRODUCTION

texts are known to have been translated and adapted into Greek, although under different circumstances and probably for different purposes.

Literate baboons and baboons as entertainers

The notion of literate baboons in Petese is by no means unique. An interesting parallel to the association between baboons and specific writings occurs in the Oracular Arnuletic Decrees from around the turn ofthe first millennium BC.30 According to these texts, a pair of baboons referred to as Khons-wn-nbn and Khons-p.?-i. ir-sbr. w were associated with books of life and death. Also these baboons form a pair, and again this can be explained with reference to the duality of the writings in question, life vs. death. It cannot be excluded that this pair of baboons might, to some extent, have served as inspiration for those in Petese. They still played a role in the Hellenistic period as shown e.g. by their depiction on a gate from the reign of Ptolemy III, and they came to be regarded as the eyes and ears of the sun-god.31 Moreover, their association with writings of life and death might be seen as parallel to the Petese baboons and the writings of virtue and vice. We learn from Khamwase and Siosiris, Il.6ff, that virtue leads to life after death, whereas vice leads to destruction of the soul. There are, however, also essential differences. Khons-wn-nbn and Khons-p?-i. ir-sbr. w neither write nor entertain. It is Thoth who reco-rds the life-time of the individual in the amuletic decrees. The role of the baboons is to bring forth the re cords and proclaim life and death, and for this reason they are said to be the ones who 'give breath' and who 'take breath away'.

Another interesting statement with reference to the notion of literate baboons is found in Horapollo, Hieroglyphika 1.14, where it is explained why a baboon, among other things, may signify letters:

'Schrift: weil es eine Art Hundskopfaffen gibt, die die ägyptische Schrift kennen. Deswegen hält der Priester, wenn ein Hundskopfaffe zum ersten Mal in den Tempel gebracht wird, ihm eine Schreibpalette, eine Binse und Tinte hin und prüft, ob er zu der Art gehört, die die Schrift kennt und ob er schreibt. Außerdem wird das Tier dem Hermes zugestellt, der von allen Schriften Kenntnis hat.,32

The description of a priest who hands writing materials to a baboon is closely parallel to that of Petese who hands papyrus and scribal-palette to the two baboons and who is also a priest.33 However, while the act described by Horapollo was undertaken in the remote past in order to discover whether baboons were in fact literate, Petese has no such doubt.

30. Edwards, Oracular Amuletic Decrees of the Late New Kingdom. The relevance of these texts was kindly pointed out to me by H. W. Fischer-EIfert.

31. For Khons-wn-nbn and Khons-ps-!. !r-sbr. w, see Posener, Annuaire du College de France 67 (1967/ 68), pp. 345-9; idem, Annuaire du College de France 70 (1970/71), pp. 391-6; and Brunner-Traut, in Fragen an die altägyptische Literatur, pp. 125-45, esp. pp. 139-40.

32. Translation from Thissen, Des Niloten Horapollon Hieroglyphenbuch 1, pp. 14-5.

33. P. Petese Tebt. A, '5'.8ff.

10

INTRODUCTION

A noteworthy description of baboons also occurs in Aelian, On the Characteristics of Animals 6.10:

'Under the Ptolemies the Egyptians taught baboons their letters, how to dan ce, how to play the flute and the harp. And a baboon would demand money for these accomplishments, and would put what was given hirn into a bag which he carried attached to his person, just like professional beggars.'34

Although Aelian does not rnention story-telling, he does describe baboons that were both litera te and perforrned as entertainers, wh ich is the role they play in Petese.

Allusions to The Petese Stories in Other Contemporary Literary Texts?

In two conternporary literary texts there is reference to writings referred to as bsf n

s~m. t. This is precisely the same phrase which is used to describe the thirty-five stories of vice in The Petese Stories, and it raises the possibility that we rnight have he re a direct reference to these stories.35

The texts in question are the Insinger wisdorn text and the invective about the seedy harpist Harwedja CHarpist, N.9). The latter relates how the harpist, once drunk, 'sings anew of "the scorn of the wornen'" Cwhm tjd n ns bsfw n ns s~m.tw). This is one of rnany exarnples about his inappropriate behavior, and it is clear frorn the context that he sings about the sort of thing that earns wornen scorn. The other reference occurs in the Insinger wisdorn text as part of the ninth instruction which concerns wornen. It is sornewhat more difficult since it occurs in two versions that have been very differently interpreted.

P. Insinger, VIII. 10: P. Carlsberg 2, N.lO:

wn ts nty-iw iw=y ir-rb st br ps bsfn s~m. t bn

wn ns mtw hn n~ sh.w bn ns bsfn s[~m.t

The Insinger passage rnay be translated 'There is she whorn I know frorn "the scorn of evil wornen"', while the Carlsberg version reads 'There are those who are in the writings arnong "the scorn of wornen".' It is not clear which is better. The text of the Insinger papyrus is 'replete with omissions, transpositions, rnisunderstandings, and other kinds of errors'. 36

The Carlsberg papyrus often seerns more reliable, but it too suffers frorn corruption. What is irnportant, however, is that the Carlsberg papyrus explicitly understood the phrase 'the scorn of wornen' to represent sorne form of literature.

This was already recognized byVolten who cornrnents: 'Es wird hier ein Buch genannt, das auch im Harfenspieler 69 erwähnt wird C ... ). Nachdem der Verfasser in Ins. 8.8-9 die guten Frauen besprochen hat, begnügt er sich betreffs der schlechten mit einer Literaturhinweisung.>37 Lichtheim later suggested that the phrase, rather than referring to a specific work, represents 'the title of the Dernotic literary treatment of the topos [of good

34. Translation from Scholfield, On the Characteristics of Animals 11, p. 2l.

35. For os! as the older writing of sbJ, Coptic CWqIq, see Story of Petese, p. 23, note on line 13.

36. Lichtheim, Ancient Egyptian Literature III, p. 185.

37. Volten, Das Demotische Weisheitsbuch, p. 49.

11

INTRODUCTION

and bad women], probably in groups of aphorisms.'38 This suggestion is followed by Thissen, who argues that the phrase is a translation of \jI6yo~ YUVUlKWV which is used to describe an excerpt from Euripides' Hippolytus (664-8) in a gnomology on women and marriage.39

The Petese Stories allows us see the phrase in a different light. Here it is clearly used to describe the treatment of bad women in narrative form rather than aphorisms. No collection of demotic aphorisms on bad women is in fact known so far, with or without the title under discussion, and it is hardly conceivable that the two demotic texts refer to Greek literature in this manner. Petese, on the other hand, includes a whole series of stories on the topic of bad women, each specifically entitled 'the scorn of women', and this corresponds perfectly with the wording in P. Carlsberg 2, which refers to texts - in the plural - from among those entitled 'the scorn of women,.40 There are, moreover, indications that Petese was transmitted over several centuries and enjoyed considerable popularity. It is particularly noteworthy that the Tebtunis temple library included copies of both the Insinger wisdom text and Petese, since the two texts are here shown to be contemporary and to occur within the same physical context. In the case of the temple library, it may therefore be reasonably assumed that the reader of the Insinger wisdom text would in fact also be acquainted with The Petese Stories.

In view of these points, it seems to me likely that the title mentioned in the Insinger wisdom text and the harpist invective do indeed refer directly to the collection of texts concerning bad women that form half of The Petese Stories.41

~

The Theme of Good and Bad Women

The description of women in terms of good and bad is discussed by Lichtheim in relation to demotic wisdom literature.42 She notes that this was a Hellenistic literary topos and refers, La., to papyri containing 'florilegia of poetic sayings alternatingly denouncing and defending women and marriage'. 43 While the distinction between good and bad women in fact has a long tradition in Egypt, being already attested in The Teaching of Ptahhotep from the Middle Kingdom, the antithetical treatment of good and bad women in these florilegia is very similar to the structure of The Petese Stories. 44 There are, moreover, indications that Petese might not have existed in its present form prior to the Hellenistic period. This raises the question of a possible relationship, but it is not one that will be further pursued on this occasion. The question of the relationship between Egyptian

38. Lichtheim, Late Egyptian Wisdom Literature, p. 161.

39. Thissen, Enchoria l4 (1986), pp. 159-60.

40. The preposition bn is used in the partitive sense.

41. If this interpretation is correct, then P. Carlsberg 2, IV.10, rnay be understood thus: There are the kind of wornen who are known frorn sorne of the stories arnong those labeled 'the scorn of wornen'. Or, in other words, there are actually really wicked wornen like those described in The Petese Stories.

42. Lichtheim, Late Egyptian Wisdom Literature, pp. 48-50, 161-2.

43. Lichtheim, op. cit., p. 51; cf. also Thissen, Enchoria 14 (1986), pp. 159-60.

44. The specific passage in The Teaching of Ptahhotep is discussed by Troy, GM 80 (1984), pp. 77-82.

12

INTRODUCTION

and Greek literature, and which influenced which, involves complex methodological considerations which are better reserved for a more general discussion of the material.45

The Petese Stories and Herodotus

At least one of the individual Petese stories was translated into Greek. While this in itself is quite interesting, the translation assurnes an even greater significance since the identity of the person to whom it was due is known. This was none other than Herodotus who incorporated the story into his dramatic account of Egypt's past. The story in question is the so-called Pheros Story (2.111). The same story occurs in a slightly different version in Diodorus (1.59), and it is also alluded to by Pliny the EIder (Hist. Nat. 36.74). Since 'Pheros' is merely a Greek rendering of pharaoh, I have found The Blinding of Pharaoh a more appropriate designation for the Egyptian version.

A comparison between the Egyptian version and the two Greek versions offers a valuable insight into the manner in which Herodotus and Diodorus dealt with their Egyptian material. Some basic comments on the story are presented in the present volume, but a detailed commentary will be published separately since it is not very likely that it would come to the attention of scholars outside the field of Egyptology if it were hidden away in a demotic text edition.

Petese the Heliopolitan Sage in Egyptian and Greek Literary Tradition

Petese, the main character of the frame story, seems to have enjoyed an outstanding reputation as a Heliopolitan sage in both Egyptian and Greek literary tradition. One of the sources of this tradition is another demotic papyrus from the Tebtunis temple library, now in Yale, which contains the narrative introduction to an astrological work.46 It relates how the text had once been discovered on a papyrus in a specific part of the temple of Heliopolis. It was subsequently brought to the attention of pharaoh, who summoned Petese and asked hirn to explain the nature of the work. Petese informs pharaoh that it contains extensive teachings about certain matters, and he is duly rewarded. The astrological text itself is then introduced with the words 'Here is a copy of the book of Imhotep the Great, son of Ptah, the great god,.47 The authorship is here, as in a number of other demotic astrological papyri, ascribed to Imhotep.

There seems little reason to doubt that Petese in this introduction is the same as the main character in The Petese Stories . Not only do they share the same name, but both men are described as prophets, they are attached to the temple of Heliopolis, they possess arcane knowledge, and they are attested in contemporary literary texts. The names of their fathers are slightly different; one is son of P?-di-ltm, while the other is son of Mr-ltm. Yet

45. The complexity of the question is, to some extent, exemplified by the question of Greek influence on the Inaros stories. See Hoffmann, Ägypter und Amazonen, p. 29, and idem, Der Kampf um den Panzer des Inaros , pp. 49-78,113-20, who seeks to ne gate the possibility, and the rebuttal byThissen, SAK 27 (1999), pp. 369-87.

46. The unpublished P. CtYBR 422. It was briefly mentioned already in Story of Petese, pp. 81-2.

47. Demotic tw-s b.f p? gm r ly-m-htp wr s? Pt~ p? ntr r? (not correctly read in Story of Petese, p. 82) .

13

INTRODUCTION

both contain the divine element Atum, and names are frequently mutated in these late sources. Thus, for instance, in the case of the famous Khamwase, the names of both his wife and son are entirely different in the two main stories, although they indisputably concern the same person.48 It is unfortunate that the beginning of the first line of the Yale papyrus is lost since the partially preserved introductory formula is weIl-attested and known always to contain the name of the pharaoh in whose reign the following story is set.49 Accordingly, it would have provided a valuable clue to the historical setting ofPetese.

The Yale papyrus sheds considerable light on another important source, the Greek P. Rylands 63, and to these two sources should be added further information supplied by Strabo.50 The conclusions are, I think, spectacular. The Rylands papyrus dates to the late 2nd or the 3rd century AD and is therefore more or less contemporary with the Tebtunis temple library. It is merely the last page of a longer text, and it preserves the final twelve lines, followed by the title of the work and the drawing of a coronis. The twelve lines form the end of a dialogue between Plato and a certain Peteesis, who explains various astrological phenomena to the philosopher. The title is incompletely preserved, but the editors cautiously read the first part DAunüVOe; TOD 'A8T)vaiwv qnAocroqnou 1tpOe; TOUe; 1tpo<pfrrae;.

On this basis it may be concluded that the text consisted of dialogues between Plato and a number of prophets of which Peteesis was one. The name Peteesis is simply a Greek writing of Petese, and the similarities between the Greek text and the Yale papyrus are striking. Each teIls the story of an Egyptian prophet who has the name Petese, who has an exceptional knowledge of astrology, and who imparts this knowledge to a third party. Yet one more piece of evidence connects the two prophets. Strabo (17.1.29) states that Plato lived in Heliopolis for thirteen years with Eudoxus, and adds 'for since these priests excelled in their knowledge of the heavenly bodies, albeit secretive and slow to impart it, Plato and Eudoxus prevailed upon them in time and by courting their favour to let them learn some of the principles of their doctrines'.51 The astrological discussions between Plato and Peteesis can thus be placed in Heliopolis with some certainty. The conclusion seems inescapable

48. The wife and son are called Ihwere (1h-wr.t) and Merib (Mr-ib) in Khamwase and Naneferkaptah, but Mehweskhet (M~-wsb. t) and Usimare (Wsy-mn-R~ in Khamwase and Siosiris. For the correct reading of the name of the son in the latter story, see Ritner, in The Literature of Ancient Egypt3 (ed. Simpson), p. 489, n. 46.

49. Cf. Ryholt, ZPE 122 (1998), pp. 198-9.

50. The Rylands papyrus is edited by Johnson, Martin, and Hunt, Catalogue of the Greek Papyri in the John Rylands Library II, pp. 2-3, no. 63. The Platonic dialogues are written on the back (verso) of a papyrus originally inscribed with an 'official account ofland' (edited ibid., p. 410, no. 379). The editors note concerning the latter that 'Antoninus and Verus Caesars ( ... ) are mentioned, and the document was no doubt drawn up in their reign, probably at the end ofit, since the 9th year (A. D. 168-9) is referred to'. For the literary tradition relating to Plato's visit to Egypt, see above all the detailed study by Mathieu, ASAE 71 (1987) , pp. 153-67. Mathieu does not discuss the Rylands papyrus, which is mentioned by Kakosy, in Gedenkschrift Hahn, p. 27, and Quack, CdE 77 (2002), pp. 79-80. The relation between the Rylands papyrus and The Petese Stories was first pointed out in the latter study. It seems to be overlooked, however, that the Yale papyrus apparently provides a direct link between these two sources.

51. Translation from Jones, The Geography of Strabo VIII, pp. 83-5. The traditions about Plato's pursuit of astrology and astronomy in Egypt are discussed by Mathieu, ASAE 71 (1987) , p. 163.

14

INTRODUCTION

that Petese, the sage prophet from Heliopolis in Egyptian literary tradition, is identical with the like-named prophet who instructed Plato in astrology according to this Greek literary tradition.

A Petese was also renowned in antiquity as a scholar of botany and especially alchemy.52 In some late manuscripts he is even described as king of Armenia. This character might be a further development of the Heliopolitan sage and teacher of Plato, but the name itself is exceedingly common and there is no association between the alchemist and astrology or Heliopolis in the available sources.

A further Egyptian literary text that mentions a Petese in relation to Heliopolis is the recently (re)discovered P. Queen's College, which is written in the so-called abnormal hieratic script.53 The date of the manuscript and the historical setting of the story seem to preclude the possibility that it concerns the Heliopolitan sage. The manuscript is dated around 730 or 670 BC on the basis of the witness formula and a 21st regnal-year recorded in the colophon, and the story itself is said to take place during the reign of a king Usimare, who could be king Piye but is more likely to be one of the much earlier kings with this prenomen. Moreover, the man in question is not a prophet and does not seem to play the role of a sage or magician.

The question remains whether Petese, the Heliopolitan sage, is a historical character. There seems to be little doubt that he was regarded as such in both Egyptian and Greek tradition, but this in itself constitutes no proof. More significant is the fact that the demotic narrative literature from the Tebtunis temple library predominantly concerns historical persons.54 This is hardly a mere coincidence, and the possibility that Petese is also a historical character may therefore be regarded as very real, although any positive confirmation is lacking. If Petese were indeed a historical character, he would have lived no later than the end of the 4th century Be. This terminus ante quem is provided by P. Petese Saq. which provides the earliest reference to Petese.55

The claim that he instructed Plato in astrology would narrow down his date to the late 5th or early 4th century BC, a few generations prior to the Saqqara papyrus. It has been suggested that Plato's visit to Egypt took place specifically in 393 BC when Achoris became king. 56 Confirmation that the visit took place after the end of the Achaemenid occupation in 404 BC might be seen in the above-mentioned Yale papyrus which dates Petese to the reign of a 'virtuous king' (nsw mnb). It is hardly conceivable that an Achaemenid king would be described in this manner after the occupation, and the description almost certainly pertains to a native ruler. However, two serious obstacles present themselves in regard to dating Petese with reference to Plato. Firstly, it is still disputed to what extent

52. See in detail Quack, ceiE 77 (2002), pp. 80-91.

53. Unpublished; preliminary reports are Baines et al. , JEA 84 (1998), pp. 234-6, and Baines, Egyptian Archaeology 14 (1999), pp. 33-4, cf. also Quack, ceiE 77 (2002), pp. 78-9. I thank H.-W. Fischer-EIfert for further comments on the text and for placing a preliminary transliteration at my disposal.

54. See discussion pp. 18-9 below.

55. Cf. Story of Petese, pp. 11, 88.

56. Mathieu, ASAE 71 (1987), pp. 156-7.

15

INTRODUCTION

the account of Greek philosophers' visits to Egypt, wh ich was seen as the most ancient civilization of aIl, represents a literary topos rather than a historical reality.57 Plato's interest in Egypt need not indicate that he ever visited the country. In the case of the Greek poets, it has been convincingly demonstrated that most biographical details were derived from readings of their works. 58 The same might be true of Plato, whose visit to Egypt could have been constructed out of his references to the country and its culture. Secondly, even if Plato did visit Egypt, it is again possible that his encounter with Petese is a later literary tradition. These two points do not refute the possibility that the two might have meet and therefore have been contemporary, but they do advise caution. Should by a stroke of good luck the lost beginning of the Yale papyrus turn up among the thousands of still unpublished fragments from the Tebtunis temple library, we would learn during whose reign Petese lived according to Egyptian tradition. It will, in that case, be interesting to see to what extent this date corresponds to that of Plato.

The Date of The Petese Stories

Petese was regarded as a sage from the past, alongside Imhotep and Khamwase. While he may weIl have been a historical person, there is no compelling reason to accept the claim that he was responsible for the compilation of the seventy stories of female virtue and vice. The attribution of major didactic works (in the broadest sense) to renowned historical characters was a common literary device in ancient Egypt, aimed at lending them

• credibility; mostly - if not always - we are dealing with pseudoepigraphy. Thus, for instance, we must also reject Imhotep as the author of several astrological texts from the Tebtunis temple library attributed to his hand.

In order to date The Petese Stories it is necessary to turn to internal criteria, and the new fragments published he re contain a keyword wh ich might shed light on when the work in its present form was created. This is the reference to a 'royal auction' ('ys n pr-'5) wh ich was a Hellenistic institution and not attested prior to the 3rd century Be. 59 Unfortunately the term occurs in a very small fragment, and the context is not preserved. It is therefore not clear whether the term is central to the story in question or not. If the royal auction plays no major role in the story, it might merely have been a detail added at some point during one of the redactions the material underwent in the course of its transmission. If, on the other, it is important for the plot and not a later addition, we must ass urne that this specific story could not have been composed prior to the Hellenistic period. That in turn would imply that the collection of stories as a whole, and in its present form, cannot predate the 3rd century Be.

57. See Mathieu, ASAE 71 (1987), p. 153, with references. Mathieu argues strongly in favor of a historical visit, amassing a wealth of sources on the basis of which he reconstructs Plato's possible itinerary (pp. 158-60). More recently also Kakosy, in Cedenkschrift Hahn, pp. 25-8, has argued that Egypt was in fact regarded as an intellectual center to which Greek philosophers - including Plato - traveled in the pursuit of knowledge.

58. Lefkowitz, The Lives of the Creek Poets .

59. See the comments on fragment C3, x+2.

16

INTRODUCTION

At the same time it is clear that at least two of the stories go back beyond this date. The

Blinding of Pharaoh was heard and translated into Greek by Herodotus in the mid 5th century BC, and the frame story about Petese hirnself is preserved in P. Dem. Saq. 4, which is believed to date no later than the end of the 4th century Be. In this respect it is significant that the text itself makes no claim that Petese actually composed the stories; the stories were rather collected and committed to writing on his command. This may acknowledge the fact that some of the stories in question already had a tradition of their own and enjoyed some popularity.

The tentative evidence forrned by the term 'royal auction' might therefore indicate that Petese as a whole consists of a number of stories that were integrated into a single work in the Hellenistic period, but that some - perhaps many - of the individual stories date much further back in time.

The Size of The Petese Stories

In view of the fact that The Petese Stories included a frame story followed by apparently no less than seventy shorter stories, its size must once have been quite impressive.60 Most of the text is now lost, but a loose estimate of its original size may nonetheless be ventured. The preserved parts of the frame story occupy four full columns (P. Petese Tebt. A, '2' - '5'), but both its beginning and end are lost. None of the better preserved short stories occupies less than a column, although they are all incomplete; The Blinding of Ph.araoh (fragment Cl, 1-11) occupies nearly two columns in its present state, while The Prince and the Kalasiris (fragment C, III), TheAvaricious Merchant (fragment D2, II-III) and The Prodigal Child (P. Petese Tebt. A, '8') each occupies at least one full column. If these four are representative of the stories as a whole, we can ass urne an average size of perhaps one and a half column per story. This adds up to 105 columns, and with the addition of the frame story itself a total of about 110 columns in all. Also in this respect, The Petese Stories would be comparable to The Myth of the Sun's Eye. An unpublished manuscript from the Tebtunis temple library with dual pagination indicates that the myth in this particular copy might have occupied as many as 124 columns.

The exceptional size of Petese, if correctly estimated, may weIl be the reason why the text was divided between two papyri. The necessity of dividing up the text in this manner might even be anticipated by the introduction to the work, which states that the stories were to be written down not on a single papyrus, but on papyri in the plural (gm(".w). The division of large works between several physical manuscripts is, of course, weIl-known from contemporary Greek literature, where the large texts were formally divided up into numbered books. The Petese Stories would be the first such example to emerge as far as ancient Egyptian narrative literature is concerned.61

60. The following discussion of the size is revised in relation to the much more conservative estimate I presented in Story of Petese, p. 69. The latter was made be fore the manuscript published he re had been identified, and before I had had the opportunity to examine in detail many of the other literary texts from the temple library, above all The Inaros Epic and The Myth of the Sun's Eye.

61. For rare instances of extensive Books of the Dead divided between two papyri, see Quirke, in Studies James, p. 91.

17

INTRODUCTION

Why The Petese Stories?

A fundamental question that remains to be answered is the purpose of The Petese Stories within the Tebtunis temple library. I have argued elsewhere that the narrative literature from the library is very unlikely to represent merely a random collection kept for entertainment purposes.62 Naturally the question cannot be answered without a survey of the literary material from the temple library as a whole, and most of the material still remains unpublished. It is therefore not possible to go into detail on this occasion. Yet having examined much of the material over a number of years, it seems dear that there are some significant, common denominators, and there are two aspects in particular to wh ich I would like to draw attention.

The first concerns the protagonists within the narrative material. Leaving aside the mythological narratives, the stories predominantly concern historical characters.63 Indeed there is not a single narrative that can positively be said to have an entirely fictitious cast of characters. What is more, the protagonist always seems to be a figure of considerable renown. There is no room for the anonymous or low status protagonists that characterize part of the Middle and Late Egyptian narrative material.

The second aspect is the documentary nature of much of the non-narrative literary material, documentary here being used in the sense of factual record. 64 The texts in question contain descriptions that range from time and space, to geography and the characteristics of the individual nomes. The material also indudes, for instance, copies of ancient and historically documented inscriptions.

I regard these two aspects as fundamental for the understanding of the narrative literature, and would argue on this basis that it was primarily kept as a form ofhistorical record. That the narrative literature from the temple library does not represent his tory to us is immaterial in this relation. Much more significant is the fact that narratives like these, and indeed some of these narratives specificaIly, were exploited as source material for the Egyptian histories written by authors such as Herodotus and Manetho. It may, accordingly, be suggested that a primary motivation for the presence of Petese in the temple library was the fact that the work was supposed to have been composed by a renowned sage from the past.

Although I believe that the perceived historical dimension of the narrative literature was a primary factor in the selection, it would hardly have been the only. Other factors are likely to have played a role as weIl, such as the literary merits of a text or its perceived message. The Petese Stories seem to have enjoyed considerable popularity and circulation in their time. It is particularly important that two contemporary works seem to refer explicitly to the many stories about vice, since this would presuppose that their intended

62. Ryholt, in Studies Larsen, pp. 505-6; idem, in Tebtynis und Soknopaiu Nesos, pp. 162-3.

63. These include Inaros I of Athribis, who rebelled against the Assyrians, Imhotep, the chancellor of Djoser, Khamwase, the high-priest in Memphis and son of Ramesses H, as weIl as the kings Djoser, Amenemhet, Sesostris, Ramesses, Necho, Petubastis, and Nectanebos H.

64. The material discussed by Ryholt, in Tebtynis und Soknopaiu Nesos, pp. l41-70.

18

INTRODUCTION

audience was well familiar with them. Unfortunately it is, as always, exceedingly difficuIt to ascertain what precisely contributed to the popularity of a specific piece of literature.

A word of appeal

I shall end this introduction with a word of appeal. Petese is one of the most fragmentary Egyptian narratives published to date, and it is hoped that the reader will bear this in mind if the notes often exceed the text that is actually preserved and if discussions are sometimes found wanting. The first volume included about 85 fragments belonging to the main manuscript, P. Petese Tebt. A, and the present volume adds another 184 fragments of its companion, P. Petese Tebt. CD. In contrast to the fragments originally published, where most could be assembled into aseries of columns, the majority of the fragments here edited are 'floating', Le. without a fixed position, and whichever text they contain is therefore all the more difficult to grasp.