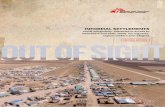

Informal Sector Pollution Control: What Policy Options Do We Have?

Transcript of Informal Sector Pollution Control: What Policy Options Do We Have?

Informal Sector Pollution Control: What Policy

Options Do We Have?

ALLEN BLACKMAN *

Resources for the Future, Washington, DC, USA

Summary. Ð In developing countries, urban clusters of informal ®rms such as brick kilns andleather tanneries can create severe pollution problems. These ®rms are, however, quite di�cult toregulate for a variety of technical and political reasons. Drawing on the literature, this paper ®rstdevelops a list of feasible environmental management policies. It then examines how these policieshave fared in four independent e�orts to control emissions from informal brick kilns in northernMexico. The case studies suggest that: (a) conventional command and control process standardsare generally only enforceable when buttressed by peer monitoring, (b) surprisingly, cleantechnologies can be successfully di�used even when they raise variable costs, in part because earlyadopters have an economic incentive to promote further adoption, (c) boycotts of ``dirty'' goodssold in informal markets are unenforceable, (d) well organized informal ®rms can blockimplementation of costly abatement strategies such as relocation and (e) private sector-ledinitiatives may be best suited for informal sector pollution control. Ó 2000 Elsevier Science Ltd.All rights reserved.

Key words Ð informal sector, environmental policy, Latin America, Mexico

1. INTRODUCTION

In most developing countries, the informalsector has grown swiftly over the last severaldecades as a consequence of populationgrowth, rural±urban migration and regulation.Today, it accounts for over half of nonagri-cultural employment in virtually all LatinAmerican and African countries (Ranis &Stewart, 1994, pp. 18±20). Although oftencharacterized as a collection of streetmerchants, the informal sector actually includesmany pollution-intensive activities such asleather tanning, brick and tile making andmetalworking. Given the sheer number of such®rms in developing countries, the aggregateenvironmental impacts can be very signi®cant.

Controlling pollution created by informal®rms is, however, especially di�cultÐeven bydeveloping country standardsÐfor a number ofreasons. By de®nition, informal ®rms have fewpreexisting ties to the state. In addition, theyare di�cult to monitor since they are small,numerous, and geographically dispersed.Finally, they sustain the poorest of the poor. Asa consequence, they may appear to both regu-lators and the public as less appropriate targetsfor regulation than larger, wealthier ®rms.Given these constraints, the application of

conventional regulatory approaches is boundto be problematic if not completely impractical.

In Mexico, as in developing countries aroundthe world, small-scale traditional brick kilns area notorious informal sector source of urban airpollution. According to one estimate, there areapproximately 20,000 traditional brick kilns inMexico (Johnson, Soto, & Ward, 1994). Manylarge cities support several hundred. The kilnsare ®red with a variety of cheap, highlypolluting fuels such as plastic refuse, used tires,manure, wood scrap, and used motor oil. As aresult, in some cities they are a leading city-wide source of air pollution. In addition, theyare generally a serious local health hazard tothe residents of the poor neighborhoods thattypically host brickyards, as well as to brick-makers themselves (Blackman, Newbold, Shih,& Cook, 2000). E�orts to control pollutionfrom traditional kilns in Mexico have not beencoordinated at the national level. Rather,individual municipalities have implemented a

World Development Vol. 28, No. 12, pp. 2067±2082, 2000Ó 2000 Elsevier Science Ltd. All rights reserved

Printed in Great Britain0305-750X/00/$ - see front matter

PII: S0305-750X(00)00072-3www.elsevier.com/locate/worlddev

* I am grateful to the Tinker Foundation for ®nancial

support, Geo�rey Bannister for invaluable assistance

with ®eld research and primary documents, a referee for

helpful comments, and all of our interviewees in Mexico

and Texas. Final revision accepted: 8 May 2000.

2067

variety of strategies, which have met withdecidedly mixed success. This mixed recordprovides an opportunity to study what types ofpolicies work and what types do not.

Using the existing literature as a startingpoint, this paper ®rst develops a menu offeasible policy options for pollution control inthe informal sector, and then examines howthese policy options have fared in dealing withtraditional Mexican brickmakers. We analyzepollution control e�orts in four cities innorthern Mexico: Cd. Ju�arez, Saltillo, Zacate-cas and Torreon. Our case studies are based oninterviews with brickmakers, regulators andother stakeholders in each city as well as onprimary and secondary documents.

The paper is organized as follows. Section 2provides further background on informalsector polluters and develops a menu of feasiblepolicy options. Section 3 presents the four casestudies. Section 4 distills policy lessons.

2. POLICY OPTIONS

(a) How serious a problem is informal sectorpollution?

Given the heterogeneity of informal sectoractivities, generalizations about their environ-mental impacts are likely to be misleading. Inmost developing countries, the majority ofinformal activities are retail-oriented and createfew environmental problems beyond litter andcongestion (Perera & Amin, 1996). Thoseinformal activities that are polluting may not beleading sources of emissions. For example, inmany urban areas, informal sector air pollutionis dwarfed by vehicular emissions. 1

Certain types of informal activities can,however, create severe pollution problems.Leather tanning, electroplating, metalworking,brick and tile making, printing, auto repair,wood and metal ®nishing, mining, charcoalmaking, textile dyeing, dyestu�s manufacture,and food processing have received the mostattention in the literature (e.g., Bartone &Benavides, 1993; Kent, 1991). Informal ®rmsengaged in these activities can have environ-mental impacts that belie their size for anumber of reasons. Most important, they areoften quite numerousÐmany urban areassupport thousands. Second, some evidencesuggests that informal sources are more pollu-tion-intensive than larger sources since they useinputs relatively ine�ciently, lack pollution

control equipment, lack access to basic sanita-tion services such as sewers and waste disposal,and are operated by persons with little aware-ness of the health and environmental impacts ofpollution (Kent, 1991). Third, as a rule, infor-mal sources are highly competitive (sincebarriers to entry are relatively low) and there-fore are under considerable pressure to cutcosts regardless of the environmental impact.Finally, informal ®rms are usually a signi®cantsource of employment and are often situated inpoor residential areas. As a result, their emis-sions directly a�ect a considerable population.

(b) The standard regulatory instruments: whichare feasible?

Environmental regulatory instruments aretypically categorized according to three criteria:(i) whether they dictate ®rms abatement deci-sions or simply create ®nancial incentives forabatement, (ii) whether they require the regu-lator to monitor emissions, and (iii) whetherthey involve government investment in abate-ment infrastructure. Policies that dictateabatement decisions are known as ``commandand control'' instruments, while those thatcreate ®nancial incentives for abatement arereferred to as ``economic incentive'' instru-ments. Policies that require the regulator tomonitor emissions are called ``direct'' instru-ments, while those that do not are called ``in-direct'' instruments (Eskeland, 1992). Examplesof these di�erent types of policies are given inthe top three rows of Figure 1. In addition tothese standard instruments, a new class of``information-based'' policies have recentlyreceived considerable attention. These policiesrely on disseminating information about ®rms'environmental performance and/or about thehealth impacts of pollution.

Which of these policies are feasible in theinformal sector? In many developing countries,a host of ®nancial, institutional and politicalfactors hamstring environmental regulation:®scal and technical resources for environmentalprotection are generally in short supply; envi-ronmental regulatory institutions as well ascomplementary judicial, legislative and datacollection institutions are much weaker than inindustrialized countries; public sentimentusually favors economic development overenvironmental protection; and environmentaladvocacyÐhistorically a critical stimulus toe�ective environmental regulationÐis generallyless prevalent and less well organized than in

WORLD DEVELOPMENT2068

industrialized countries (DevelopmentResearch Group, World Bank, 1999; Eskeland,1992). Given these constraints, direct economicincentive and command and control instru-ments are generally not practical, even whenapplied to formal ®rms, because regulatorssimply do not have the wherewithal to reliablymeasure emissions and to impose sanctionsaccordingly (Blackman & Harrington, 2000). Ifthese instruments are generally not practical forformal ®rms in developing countries, then theyare clearly not practical for informal ®rmssince, as discussed above, constraints on envi-ronmental regulation in developing countriesare magni®ed in the informal sector. Thus, themenu of policy options for pollution control inthe informal sector include the items in gray inFigure 1: indirect command and control andeconomic incentive policies, governmentinvestment, and information-based policies. Inthe next four sub-sections, we brie¯y discusseach of these options, drawing on the limitedliterature on informal sector pollution control.

(c) Indirect command and control instruments

(i) Technology and process standardsTechnology standards require ®rms to install

and operate certain types of pollution controlequipment. They demand relatively little in theway of monitoring: regulators need only checkto see that the equipment is installed. Even so,such policies may be ine�ective in the informalsector since they generally require ®nanciallystrapped ®rms to pay considerable set-up costs,and since even checking for the installation ofequipment by hundreds of anonymous ®rmsmay be di�cult. Process standards mandate

speci®c elements of the production process. Forexample, a process standard may require ®rmsto substitute clean inputs for dirty ones.Monitoring compliance is generally moreproblematic for process standards than fortechnology standards.

(ii) RelocationRelocating informal ®rms may serve three

purposes: improving their access to communalwaste treatment facilities, reducing the numberof people exposed to their emissions, andproviding secure land tenure which, accordingto some researchers, improves incentives forpollution control (Perera & Amin, 1996;Sethuraman, 1992). Unfortunately, relocationis generally costly, in part because it usuallyincreases ®rms' transportation costs: informal®rms are typically located close to markets andto their owners' residences (Omuta, 1986).

(d) Indirect economic incentive instruments

(i) Green taxesTaxing dirty inputs is a popular policy

recommendation for pollution control incountries where direct instruments are imprac-tical. In general, such taxes are relatively easyto administer since in most cases, reasonablye�ective tax collection agencies already exist(Eskeland, 1996). Taxes have the additionalbene®t of generating revenue that can be usedto defray administration or abatement costs.Unfortunately, environmental taxes have anumber of disadvantages, whether applied inthe formal or informal sector. Most important,since input taxes do not target polluting emis-sions directly, they do not create incentives for

Figure 1. A taxonomy of pollution control instruments. (Notes: aCap on level of emissions. bFee charged per unit ofemissions. cAllowances to emit a speci®ed amount of pollution which may be traded with other ®rms. dRequirement for aspeci®c abatement technology or element of the production process. eTax on dirty inputs or outputs. f Subsidy to cleaninputs or outputs. gResearch and development in pollution preventing technologies. hPublicize information about ®rms

environmental performance. iPublicize information about pollution generally.)

INFORMAL SECTOR POLLUTION CONTROL 2069

pollution control per se. For example, a tax onhighly polluting variety of coal creates incen-tives for ®rms to switch to cleaner varieties butdoes not create incentives to install pollutionabatement devices. Second, for taxes to bee�ective, ®rms must have access to less-pollut-ing substitutes at reasonable prices. Otherwise,the tax will simply raise producers costs with-out changing their behavior or worse, will causethem to switch to even dirtier inputs (Biller &Quientero, 1995). Third, ubiquitous blackmarkets make it di�cult to target taxes tospeci®c economic activities. As a result, to taxthe use of a dirty input (e.g., chrome) by aspeci®c type of ®rm (e.g., tanneries), regulatorswould have to impose an economy-wide tax onthe input, raising costs to ®rms that use theinput without environmental consequences aswell as those who do not.

(ii) Green subsidiesRather than taxing dirty inputs, policy

makers have the option of subsidizing cleanones. The principal advantage of subsidies isthat they are often more politically palatablethan taxes. Their obvious drawback is that theydrain scarce ®scal resources.

(iii) BoycottsAlthough generally not recognized as such, a

boycott by downstream buyers of intermediateinputs (such as tanned hides or bricks)produced by particularly dirty informal ®rmscan be thought of as a rather drastic indirecteconomic incentive policy. The argument forsuch a policy is that it focuses regulatory e�ortaway from anonymous informal ®rms and ontoformal downstream ®rms (Biller, 1994).

(e) Government investment

(i) Communal treatmentPerhaps the informal sector pollution

control strategy that has received most atten-tion in the literature is the construction ofcommunal treatment facilities for solid andliquid wastes (e.g., Okasaki, 1987; Chiu &Tsang, 1990; O'Connor, 1996). Communaltreatment captures economies of scale intreating wastes and minimizes monitoringe�ort. In addition, it can overcome importantbarriers to private treatment including chronicshortages of ®nancial capital, technologicalknow-how, and physical space. But communaltreatment has a number of disadvantages aswell. Constructing and operating such facilities

is costly. When user fees are instituted to®nance operating costs, polluters may revert toillegal dumping. Even if polluters are notcharged fees, they may still dump wastes sinceusing treatment facilities generally raises laborcosts (O'Connor, 1996). In addition, commu-nal treatment creates no incentives for pollu-tion prevention.

(ii) Clean technologiesWhile clean technological change and process

standards both involve pollution-preventingchanges in the production process, the formergenerally entail more radical changes. In addi-tion, unlike process standards, clean technolo-gies ideally lower ®rm's operating costs. Thus,the hope is that ®rms will adopt them volun-tarily or at least with minimal prodding, easingthe monitoring burden on regulatory authori-ties. We categorize clean technologies as a``government investment'' policy becausepublic sector ®nancing is often required todevelop clean technologies and to subsidize the®xed costs of adopting them.

Clean technologies have received consider-able attention in the literature. For example,O'Connor (1996) describe proposals to convertinformal tanneries in Colombia to processesthat substitute relatively benign chemicals fortoxic ones. Most of the literature argues thatclean technologies will not di�use widelyunless they are privately pro®table. Given thatinformal ®rms generally have slim pro®tmargins and limited access to credit, thisimplies that successful clean technologies mustinvolve low ®xed costs and must reduce vari-able costs (Kent, 1991; Bartone & Benavides,1993). 2

(f) Information-based strategies

In the formal sector, information-basedstrategies are hypothesized to work by mobi-lizing a variety of private sector agents topressure ®rms to improve their environmentalperformance. These agents include ®rm ownersand managers, victims of pollution, tradeorganizations, consumers, suppliers, andcompetitors (Tietenberg, 1998). In the infor-mal sector, information-based strategies areespecially likely to operate through ownerssince they usually work and live in closeproximity to their ®rms' pollution (Biller,1994).

WORLD DEVELOPMENT2070

3. CASE STUDIES

In this section, we examine how the policiesdiscussed above have been used in e�orts tocontrol emissions from traditional brick kilns infour cities in northern Mexico. The discussionis summarized in Table 1.

(a) Ciudad Ju�arez 3

(i) BackgroundA sprawling border city with over one million

permanent inhabitants, Cd. Ju�arez is home toapproximately 350 traditional kilns, which areprincipally ®red with scrap wood. Collectively,these kilns are a signi®cant area-wide source ofair pollution. They have attracted considerableattention because air quality in Cd. Ju�arez andits sister city, El Paso, Texas, is among theworst in North America. 4 The kilns are also aserious local health hazard to those living in thedensely populated residential neighborhoodsthat surround most of the city's brickyards.

In Cd. Ju�arez, as in our other three studycities, a number of factors makes it politicallydi�cult to require brickmakers to bear the fullcosts of pollution control. Brickmaking is asigni®cant source of employment, providingover 2000 jobs directly and 150 jobs indirectlyin transportation and wholesaling. In addition,most brickmakers are impoverished. Theytypically live next to their kilns in rudimentaryhouses with no drainage or running water.Finally, brickmakers are well organized.Approximately two-thirds belong to a tradeassociation or other local organization.

(ii) PoliciesIn 1989, the municipal environmental

authority in Cd. Ju�arez initiated a projectaimed at convincing traditional brickmakers tosubstitute clean-burning propane for dirtyfuels. This strategy is best thought of as cleantechnological change since adopting propaneinvolves signi®cant set-up costs and signi®cantchanges in the production process. In 1990, the``Brickmakers' Project'' as it came to be known,was handed o� to the Federaci�on Mexicana deAsociaciones Privadas de Salud y DesarrolloComunitario (FEMAP), a private nonpro®tsocial services organization based in Cd.Ju�arez, which had expertise in grassrootsorganizing in poor neighborhoods. FEMAPwas able to attract considerable funding andparticipation from both sides of the border.The majority of the funding came from the

Mexican government while key participantsincluded propane companies in Cd. Ju�arez, themunicipal government of Cd. Ju�arez, El PasoNatural Gas, and Los Alamos Natural Labo-ratories.

Participants in the Brickmakers' Project useda broad range of polices to promote propaneadoption. First, they subsidized various costsassociated with adoption. Propane companiesmade tanks and vaporizers available free ofcharge and a number of organizations (includ-ing local propane companies, FEMAP, El PasoNatural Gas, and local universities) providedtraining. In addition, motivated by the fact thatthe cost of propane per unit of energy wasconsiderably higher than the cost of traditionaldirty fuels, engineers from El Paso NaturalGas, Los Alamos National Laboratories andFEMAP devoted considerable e�ort to devel-oping new energy-e�cient kilns. Most of theirdesigns, however, involved completely rebuild-ing existing kilns, a prohibitively expensiveproposition for most brickmakers. Engineersalso worked to develop low-cost measures forimproving fuel e�ciency such as optimizing thefuel mixture, the manner in which bricks arestacked, and the way that the kiln opening iscovered.

Second, project leaders worked to put inplace and enforce process standards prohibitingthe use of dirty fuels. In 1992, a newly electedmunicipal government banned the use ofcertain fuels. To facilitate enforcement, the newadministration relied on peer monitoring. Atelephone hotline was set up to registercomplaints about brickmakers violating theban. Enforcement teams with the power to jailand ®ne violators were dispatched in responseto complaints. Project organizers also encour-aged local trade unions and neighborhoodorganizations in communities surroundingbrickyards to pressure brickmakers to switch topropane. The brickmaker organizations a�li-ated with the dominant national political party(the PRI) were in general quite cooperative,enforcing strict rules on permissible fuels insome brickyards.

Third, FEMAP initiated a campaign to raisebrickmakers' awareness of the health hazardsassociated with dirty fuels. Among the mecha-nisms it used were one-on-one discussions withindividual brickmakers, organized trainingsessions, and an educational comic-book.

Finally, project leaders tried to reducecompetitive pressures for brickmakers to usecheap dirty fuels by intervening in the market

INFORMAL SECTOR POLLUTION CONTROL 2071

Tab

le1.

Sum

mary

of

case

studie

s

Cd

.Ju

� arez

Salt

illo

Zaca

teca

sT

orr

eon

Back

gro

un

dA

pp

rox

ima

ten

um

ber

of

kil

ns

35

0500

60

165

Pri

nci

pal

trad

itio

nal

fuel

Scr

ap

wo

od

Use

dti

res

Scr

ap

wo

od

,u

sed

tire

sS

crap

wo

od

,re

fuse

Lea

din

gso

urc

ea

irp

oll

uti

on

?R

epu

ted

lyR

epu

ted

lyN

oN

oB

rick

mak

ers

wel

lo

rgan

ized

?Y

esY

esN

oY

esM

isce

lla

neo

us

Cro

ssb

ord

erim

pa

cts

Til

eex

po

rter

sp

ow

erfu

lK

iln

sd

eem

edto

uri

stli

ab

ilit

yC

om

pet

itio

nfr

om

nei

gh

bo

rin

gci

ties

Poli

cies

ÐP

riva

tese

cto

r-le

din

itia

-ti

ve

wit

hst

ron

gp

ub

lic

sect

or

sup

po

rt

ÐP

ub

lic

sect

or-

led

init

iati

ve

ÐP

ub

lic

sect

or-

led

init

iati

ve

ÐP

ub

lic

sect

or-

led

init

iati

ve

ÐF

ocu

so

ncl

ean

tech

no

-lo

gic

al

cha

ng

e(c

on

ver

sio

nto

pro

pa

ne)

ÐIn

itia

lfo

cus

on

clea

nte

chn

olo

gic

al

chan

ge

(co

nver

sio

nto

pro

pan

e)

ÐC

lean

tech

no

logic

al

chan

ge

(co

nver

sio

nto

pro

pan

e)

ÐC

lean

tech

no

logic

al

chan

ge

(co

nver

sio

nto

pro

pan

e)p

lus

relo

cati

on

ÐS

ub

sid

ies

to®

xed

ad

op

-ti

on

cost

sÐ

Su

bsi

die

sto

®xed

ad

op

tio

nco

sts

ÐS

ub

sid

ies

to®

xed

ad

op

tio

nco

sts

ÐP

rom

ised

sub

sid

ies

to®

xed

relo

cati

on

an

dad

op

tio

nco

sts

ÐR

&D

inen

erg

y-e

�ci

ent

kil

ns

ÐR

&D

inen

ergy-e

�ci

ent

kil

ns

ÐP

roce

ss(b

an

on

use

of

tire

s)u

nd

erp

inn

edb

yp

eer

mo

nit

ori

ng

ÐP

roce

ssst

an

dard

s(b

an

on

excl

usi

ve

use

of

tire

s)u

nd

erp

inn

edb

yp

eer

mo

ni-

tori

ng

ÐP

roce

ssst

an

dard

(ban

on

use

of

tire

s)u

nd

erp

inn

edb

yp

eer

mo

nit

ori

ng

an

dre

gis

trati

on

ÐP

rivate

lyen

forc

edp

roce

ssst

an

dard

s(b

an

on

use

of

tire

s,®

rin

gli

mit

s)Ð

Pu

bli

ced

uca

tio

nin

itia

tive

ÐS

ub

sid

ies

tocl

ean

erfu

els

(scr

ap

wo

od

)Ð

Fo

rced

relo

cati

on

of

cert

ain

kil

ns

ÐB

oy

cott

of

bri

cks

®re

dw

ith

dir

tyfu

els

wit

hin

Ju� a

rez

ÐR

igh

tsfo

rcr

eoso

ted

istr

ibu

tio

naw

ard

edto

bri

ckm

ak

ers

un

ion

ÐB

oyco

tto

fb

rick

s®

red

wit

hd

irty

fuel

sfr

om

nei

gh

bo

rin

gto

wn

s

Res

ult

sÐ

50%

ad

op

tio

no

fp

rop

an

eb

efo

rein

crea

ses

inp

rop

an

ep

rice

sle

dto

10

0%

dis

-a

do

pti

on

Ð10%

ad

op

tio

np

rop

an

eb

efo

rein

crea

ses

inp

rop

an

ep

rice

sle

dto

100%

dis

-ad

op

tio

n

Ð100%

ad

op

tio

no

fp

rop

an

eb

efo

rein

crea

ses

inp

rop

an

ep

rice

sle

dto

100%

dis

-ad

op

tio

n

ÐN

ore

loca

tio

no

rco

nver

sio

nto

pro

pan

e

ÐD

rast

icre

du

ctio

nin

use

of

tire

sa

nd

pla

stic

sÐ

Mo

der

ate

red

uct

ion

inu

seo

fti

res,

dra

stic

red

uct

ion

inp

last

ics,

use

dm

oto

ro

il

ÐC

on

tin

ued

part

ial

use

of

pro

pan

ein

som

ek

iln

sÐ

Red

uct

ion

inu

seo

fti

res;

®ri

ng

sch

edu

les

enfo

rced

ÐR

edu

ced

use

of

tire

s

WORLD DEVELOPMENT2072

for bricks. In March 1993, they helped tonegotiate an agreement among leaders of all ofthe major brickmakers' unions to establish aprice ¯oor high enough to allow all brickmak-ers to use propane. The next year, projectleaders obtained a commitment from localconstruction companies and from INFONA-VIT, the federal workers housing agency, toboycott bricks ®red with dirty fuels. Both theprice ¯oor and the boycott were quicklyundone by rampant cheating.

(iii) ResultsThe high water mark of the Brickmakers'

Project probably occurred in the fall of 1993when according to most estimates at least 50%of the brickmakers' in Cd. Ju�arez were usingpropane albeit in (slightly modi®ed) ine�cienttraditional kilns. But during the early 1990s,Mexico's state-run petroleum company was inthe process of phasing out long-standingsubsides on propane. As propane pricescontinued to rise in 1993 and 1994, keyparticipants in the project began to defect: themunicipal government relaxed the ban onburning debris, brickmakers began abandoningpropane in droves, brickmaker organizationsincreasingly dropped out as they were undercutby competitors using dirty fuels, andconstruction companies and the federal work-ers' housing agency gave up the pretense ofboycotting ``dirty'' bricks. By 1995, only ahandful of brickmakers were still usingpropane. Despite the dis-adoption of propane,the Brickmakers' Project has had some lastingimpacts: local organizations and city o�cialscontinue to enforce a ban on the use of thedirtiest fuels, mainly tires and plastics.

Although the di�usion of propane among thebrickmakers in Cd. Ju�arez was limited andtemporary, it nevertheless represents a signi®-cant achievement in view of the obstaclesinvolved, especially the drastic reduction inpropane subsidies. Which of the broad range ofstrategies employed by the project wereresponsible? Statistical analysis of survey datadescribed in detail in Blackman and Bannister(1998) suggests that three factors played a keyrole: peer monitoring applied by neighbors andlocal organizations a�liated with the citygovernment, a growing awareness of the healthrisks associated with burning dirty fuels, andsubsidies to the costs of propane equipmentand training. E�orts to introduce new energye�cient kilns and to intervene in the market forbricks were obviously ine�ective.

(b) Saltillo 5

(i) BackgroundAn industrial city of approximately 425,000

in the southeast corner of the state of Cohuila,Saltillo is home to approximately 500 tradi-tional kilns, the largest collection in any of thefour study cities. The majority of these kilnsproduce more tile than bricks. 6 60±80% of thetile produced in Saltillo is exported to theUnited States, where it is prized as an artisanalproduct. As a result, the political and economicinterests in brick and tile making in Saltillo aresomewhat stronger than in other cities. Themajority of Saltillo's brickmakers belong to asingle union, which has considerable in¯uenceowing to its large membership and ties toexporters.

Brickmakers in Saltillo rely principally onused tires for fuel. According to the CohuilaDepartment of Ecology, Saltillo's kilns burn 50ton of tires per day (El Norte, 1994). Supple-mentary fuels include scrapwood, plastics, usedmotor oil, and garbage. Kiln emissions are anacute problem for the poor residential neigh-borhoods that surround the six principalbrickyards. There is some confusion regardingthe contribution of traditional brick kilns tocity-wide pollution. Newspaper articlesfrequently assert that brick kilns are the leadingsource of Saltillo's air pollution. The cityenvironmental authority claims, however, that®xed industrial sources and a sizable vehicular¯eet are the most important sources.

(ii) PoliciesBy 1992, worsening air pollution and grow-

ing environmental consciousness led to ageneral recognition that kiln emissions were aserious problem. In early 1993, the city envi-ronmental authority initiated an e�ort toconvert traditional kilns to clean-burningpropane, the same clean technology strategyadopted in Cd. Ju�arez. With the ®nancialbacking of NAFIN (a federal developmentbank), the city government commissioned astudy to develop a plan of action. The studyrecommended building new energy-e�cientpropane-burning kilns costing approximately73,000 pesos (US $24,300) each and leasingthem to brickmakers under a rent-to-ownscheme.

Before the rent-to-own plan could be imple-mented, it was cut short by the election of anew mayor in December 1993. Under the newadministration, a number of elements of the

INFORMAL SECTOR POLLUTION CONTROL 2073

program was reformed and extended, so thatultimately, as in Cd. Ju�arez, a multifacetedapproach was adopted. Recognizing thatintroducing expensive new energy-e�cient kilnswould be problematic given brickmakers®nancial constraints, the city decided to focusinstead on simply introducing propane equip-ment that could be used in existing kilns. Usingfunds provided by the state and federalgovernments, it set up a window at theMunicipal Ecology O�ce to provide credit andtechnical extension to brickmakers adoptingpropane. 7 In addition, the city governmentpromulgated process standards. In June 1994, amunicipal ordinance was passed that forbadeburning tires after a six-month grace period andprohibited using a number of other dirty fuelsimmediately (including battery cases, usedmotor oil, plastics, and solvents). The processstandard was to be enforced by requiring allbrickmakers to register with the city govern-ment. Violators were to have their kilns closeddown. There was an attempt to enlist thesupport of brickmaker organizations inenforcing the new rules. Toward this end, thecity government convened several meetingswith leaders of local brickmaker organizations.

For reasons discussed below, Saltillo'spropane initiative failed. Subsequently, the cityfocused on limiting the use of used tires for fuel.It promulgated a regulation that allowedbrickmakers to use a combination of 50% tiresand 50% cleaner fuelsÐeither creosote (a low-grade petroleum distillate) or scrap wood. Peermonitoring was used to enforce this rule.Brickmakers and their neighbors in surround-ing residential communities monitored emis-sions and reported producers who ®red theirkilns exclusively with tires. Violators were®ned. In addition, the city set up an innovativeprogram to subsidize the cost of relatively cleanfuels: local factories provided scrap wood tobrickmakers free of charge. Finally, as a gestureof goodwill, the city funded the construction ofa public square with recreational facilities andmarket stalls for brickmakers.

Eventually, the city hopes to replace all dirtyfuels with creosote. To promote the new fuel,the city has commissioned test ®rings, and hasmade credit available. In addition, it hasawarded a contract for the distribution ofcreosote to the brickmakers' union, hoping theconcession will give the union an incentive topressure its members to adopt the fuel. Still, inJuly 1996, no brickmakers in Saltillo were usingcreosote on a regular basis.

(iii) ResultsDespite the city government's e�orts to

induce brickmakers to switch to propane, only14 ever received credit from the loan fund setup to ®nance new equipment investments andfewer than 40 ever adopted propane. A numberof factors was responsible. Most important, bythe time that the program had been launched inearnest, propane prices had risen dramaticallyrelative to the price of debris due to thenationwide reductions in propane subsidies.Concerns about costs were exacerbated by amacroeconomic recession in Mexico that madeinvesting in a new technology especiallyburdensome and risky. According to the leaderof the brickmakers' union, by the end of 1994,sales of bricks and tile had fallen o� by as muchas 70% compared to the early 1990s. In addi-tion, there was very little enforcement of theJune 1994 prohibition on burning tires, despitethe fact that over 300 out of a total ofapproximately 500 kilns were registered (theholdouts were principally kilns in the brick-yards located on the outskirts of the city).Finally, support for the project among thebrickmakers was dampened by internal divi-sions in the brickmakers' union. In part, thiswas the result of rumors that bricks and tiles®red with clean fuels were of inferior quality.These rumors persisted despite the severalsuccessful test ®rings designed to allay theseconcerns. Although the propane initiativefailed, other components of the city's environ-mental program were more successful. Mostnotably, there was a decline in the use of thedirtiest fuels such as battery cases and usedmotor oil.

(c) Zacatecas 8

(i) BackgroundA colonial city in north central Mexico and

the state capital, the city of Zacatecas is a majordomestic tourist attraction. With a populationof just over of 110,000, it is the smallest city inour sample. It is home to approximately 50small-scale brick kilns, which have traditionallyburned used tires, scrap wood, manure, usedmotor oil, and refuse. There are no unions orother local organizations to speak of among thebrickmakers. Unlike kilns in Cd. Ju�arez andSaltillo, those in Zacatecas are too few innumber to constitute a signi®cant source ofcity-wide pollution. They have attracted atten-tion because they are a health hazard to thosewho live nearby and because municipal

WORLD DEVELOPMENT2074

authorities have deemed a cluster of kilns nearthe entrance of the city to be an eyesore and athreat to tourism.

(ii) PoliciesIn December 1992, the Mayor's o�ce initi-

ated a series of meetings with brickmakers toaddress the problem of kiln emissions. The citysettled on a dual policy. First, 19 kilns near theentrance of the city would be relocated. Thecity committed to ®nding a new site for thesebrickmakers and to providing them with creditto build new kilns. Second, all kilns remainingin the city would be converted to propane. Withthe assistance of two federal credit programs(NAFIN and Solidarity Enterprises), the cityset up a loan fund to ®nance the purchase ofnew propane equipment. It o�ered three-yearinterest-free loans to several groups of brick-makers who were to share equipment. A ®rmwas chosen to supply equipment and technicalextension. To ensure that the propane initiativewas successful, the city registered all of itsbrickmakers and had them sign a pledge toadopt propane as soon as ®nancing could bearranged.

(iii) ResultsBoth of the program's components were

ultimately carried out. The 19 kilns near theentrance to the city were relocated, although ina far more draconian manner than originallyplanned. The city purchased the land wherethese kilns were located and summarily evictedthem. The owners were given the option ofpurchasing land in a new (somewhat remote)site but ®nancing was never made available. Asa result, only six brickmakers from this groupeventually relocated. The others found newemployment.

The propane initiative was completely,although only temporarily, successful. By early1994, 150,000 pesos (US $50,000) in credit hadbeen extended for the purchase of new equip-ment and by the end of the year, every kiln inthe city was being ®red with propane. Theproject was so successful that plans were madeto extend it to all municipalities within 100 kmof Zacatecas. 9

Unfortunately, as in Cd. Ju�arez, the nation-wide removal of subsidies on propane thatbegan in 1992 created strong pressures to revertto burning debris. Although Zacatecas brick-makers did not face competition from brick-makers using cheap fuel inside the city (since allbrickmakers in the city adopted propane), they

did face competition from nonadopters insurrounding municipalities. To ease this pres-sure, the city brie¯y attempted to organize aboycott of bricks ®red with dirty fuels. Theboycott soon collapsed, however, and ulti-mately propane use fell o� dramatically. In thesummer of 1996, several brickmakers continuedto use propane, but only during a brief initialphase of ®ring the kiln.

One positive legacy of the propane initiativeis that brickmakers have reduced their use oftires. As in Saltillo and Cd. Ju�arez, peermonitoring is used to enforce a ban on tires.Generally neighbors and competitors whoobserve violations complain to the municipalpolice who then issue a ®ne and temporarilyclose the o�ending kiln.

(d) Torreon 10

(i) BackgroundA rapidly growing industrial city of 450,000

in the southwest corner of the state of Cohuila,Torreon supports 165 traditional kilns. Mostare in one centrally located neighborhood, ejidoSan Antonio. The brickmakers' principal fuelsare scrap wood, pecan shells, plastics, usedtires, and garbage. Virtually all brickmakersbelong to one of the ®ve local organizations.The brickmakers face sti� competition from thenearby cities of Gomez Palacios and Matamo-ros.

Torreon has poor air quality as a result ofindustrial emissions and a sizable vehicular¯eet. Traditional kilns are considered a signi®-cant contributor to city-wide air pollution, butnot a leading contributor. A more urgentconcern is the threat that the kilns pose to theresidents of the densely populated low-incomecommunities that have grown up around themain brickyard in the last decade.

(ii) PoliciesIn 1994, the O�ce of Economic Develop-

ment in Torreon began to develop a strategyfor reducing emissions from traditional kilns. Itorganized a series of meetings that broughttogether representatives of the brickmakersorganizations, the Municipal Ecology O�ce,the federal environmental authority, andFEMAP, the same nongovernmental organi-zation that organized the propane initiative inCd. Ju�arez. As in Zacatecas, a two-prongedstrategy emerged involving relocation and cleantechnology: brickmakers in ejido San Antonio

INFORMAL SECTOR POLLUTION CONTROL 2075

would be relocated, and clean fuelsÐincludingpropaneÐwould be introduced.

Not surprisingly, the communities sur-rounding ejido San Antonio supported reloca-tion. In the early 1990s, they had organizeddemonstrations protesting kiln emissions andrepeatedly petitioned the city environmentalauthority to address the problem. The ownersof ejido San Antonio also supported relocationbecause they hoped to develop the increasinglyvaluable land used by the brickmakers into anindustrial park.

After a study of the suitability of soils indi�erent locations, the city chose two sitesoutside the city limits to use as new brickyardsand pledged to subsidize relocation. It devel-oped a package of incentives that included ahalf hectare of land, water rights on the land,10,000 pesos (US $3,300) for each brickmaker(for building a new kiln), compensation for allinventory on hand on the eve of the move, andtraining in the use of propane. To spur a shiftaway from dirty fuels, the city passed regula-tions banning the burning of particularly dirtyfuels such as plastics.

(iii) ResultsAs of July 1996, four of the ®ve brickmaker

organizations active in ejido San Antonio hadsigned documents committing their members torelocation, but no brickmakers had actuallyrelocated. The city had not yet secured thefunding for the package of relocation incen-tives. Some brickmakers doubted that the citywould keep its end of the bargain. They viewedthe relocation plan as a political ploy designedto win brickmakers' votes.

Like the relocation e�ort, the city's cleanfuels initiative has involved more talk thanaction. The city regulations banning dirty fuelsare infrequently enforced. Not surprisingly, thecity's plans to introduce propane were shelvedfollowing nationwide reductions in propanesubsidies.

The communities surrounding ejido SanAntonio have had a more signi®cant impact onkiln emissions than has the city government.After repeated protests, these communitieshave managed to get the brickmakers to agreeto stop burning tires, to ®re only at night (whenemissions from other sources are at a mini-mum), and to limit the number of kilns that are®red at any given time. In addition, three of the®ve brickmaker organizations now enforce aprohibition on the burning of tires.

4. CONCLUSION

This section distills policy lessons from thefour case studies. It makes three generalobservations about environmental manage-ment in the informal sector and then evaluatesthe performance of the pollution control poli-cies discussed in Section 2. The main points ofthe discussion are summarized in Table 2.

(a) The political economy of policy choice

Some pollution control policies imposegreater costs on ®rms than others. For example,relocation and clean technological change arerelatively costly to ®rms compared to educa-tional programs. Of course, subsidies can beused to reduce the costs of any policy. Forexample, the costs of a clean technology strat-egy can be reduced by subsidizing technicalextension, credit, and equipment.

In each of our study cities, the ability ofpolicy makers to pursue pollution controlstrategies that imposed signi®cant costs onbrickmakers depended critically on the brick-makers' political power. In both Cd. Ju�arez andSaltillo, brickmakers were numerous and wellorganized and, as a result, they were able toblock costly strategies. In Cd. Ju�arez, althoughpollution control e�orts focused on cleantechnological changeÐa relatively costly strat-egyÐthey also involved signi®cant subsidies toequipment and technical extension. In Saltillo,regulatory authorities ultimately opted for aprocess standard prohibiting exclusive use oftires as fuelÐa relatively low-cost strategyÐand made e�orts to reduce the costs of thisregulation by providing brickmakers with freescrap wood and subsidizing the cost of recre-ational facilities and market stalls. In Torreonwhich had a relatively small but geographicallyconcentrated and politically active group ofbrickmakers, regulators promoted relocationÐa costly strategy. But, they tried to do this byo�ering a generous incentive package ratherthan by threatening sanctions. Moreover, cityauthorities had limited success with this policy.By contrast, Zacatecas' brickmakers were bothfew in number and completely unorganized.They were unable to either prevent regulatorsfrom pursuing costly abatement strategiesÐrelocation and clean technological changeÐorto convince them to subsidize their expenses.

Thus, our case studies suggest that eventhough informal ®rms might appear to bepolitically ine�ectual, actually they are often

WORLD DEVELOPMENT2076

very capable of blocking costly pollutioncontrol policies. This is especially likely to betrue in cases where informal sector pollutershave signi®cant environmental impacts, simplybecause in such cases they are bound to benumerous. Hence, policy makers grapplingwith serious informal sector pollution problemswill generally be unable to pursue policies thatimpose signi®cant costs on polluters.

(b) The promise of private sector-ledenvironmental initiatives

If we discount the Zacatecas experiencebecause of the relatively small number of kilnsinvolved, then of the remaining three pollutioncontrol initiatives, the most successful was theCd. Ju�arez Brickmakers Project, which mana-ged to convince more than 175 brickmakers toadopt propane, albeit for a limited time. Thise�ort was also the only one in our sample thatwas led by a private sector organization, a factsuggests that private sector-led initiatives hold

considerable promise as a means of addressinginformal sector pollution problems.

Private sector-led initiatives would seem toenjoy a number of advantages over state-runprograms. First, the willingness of the majorityof the brickmakers in Cd. Ju�arez to cooperatewith the project suggests that private sector-ledinitiatives may be best suited to engage ®rmsthat by their nature are bound to be wary ofsustained contact with regulatory authorities.Second, the enthusiasm that the BrickmakersProject generated among funders, participants,and the public at large suggests that privatesector-led projects may be able to draw morefreely on public sympathy for environmental-ism than top±down bureaucratic initiatives.Finally, the projects' success at consensusbuilding among a diverse set of stakeholderssuggests that private sector-led initiatives maybe better able to sidestep the politics andbureaucracy that often plague public sector-ledinitiatives. The city-led initiatives in our samplewere rife with such problems. In Torreon,

Table 2. Lessons from case studies

Policy Lessons

All ÐWhen informal polluters are numerous and/or well organized, they canblock enforcement e�orts. In such cases, only combinations of policieswith low private costs are likely be feasible.

ÐPrivate sector-led initiatives with strong public sector support may bebest suited to informal sector pollution control.

Command and controlProcess standards ÐRegistering informal enterprises and peer monitoring are common

strategies for enhancing enforceability.ÐRegistration alone is not su�cient to facilitate enforcement.ÐPeer monitoring is a necessary condition for enforcement and appears

to be most e�ective when carried out by local organizations.Relocation ÐImposes relatively high costs on polluters and is therefore likely to

meet with considerable resistance.

Economic incentivesGreen subsidies ÐWithout careful monitoring, may simply encourage the resale of

subsidized goods.Boycotts ÐUnlikely to be e�ective because enforcement is highly problematic.

Government investmentClean technologies ÐNeed not be cost-reducing to di�use widely.

ÐSubsidies to early adopters may heighten competitive pressures forfurther adoption.

ÐMust be appropriate: a�ordable and consistent with existing levels oftechnology.

ÐMay be derailed by input price instability.ÐIntertemporal and place-based factors matter: universal solutions are

improbable.

Information-basedEducational programs ÐMay bolster pollution control e�orts.

INFORMAL SECTOR POLLUTION CONTROL 2077

brickmakers belonging to a union a�liatedwith a political party opposed to the municipalgovernment were impelled to oppose the city'sabatement initiative. Even those brickmakerswho supported this initiative were reluctant toput great store in a promised package of relo-cation incentives for fear that it was politicallymotivated. In Saltillo, the propane initiativewas twice disrupted by changes in the munici-pal government, ®rst in December 1993 andagain in December 1996. Finally, in bothZacatecas and Torreon, a di�cult e�ort toforge a consensus among unwieldy bureaucra-cies in neighboring municipalities was needed inorder to promote pollution abatement e�ortsamong brickmakers in each.

The quali®ed success of the Cd. Ju�arezBrickmakers' Project, however, does not implythat informal sector environmental problemsare best be left to private sector organizers. Inall likelihood, the Cd. Ju�arez Brickmakers'Project would not have had as much successwithout unusually strong United States andMexican Federal support and the support ofthe municipal and state governments. Thus, ourcase studies suggest that private sector-ledinitiatives can workÐindeed they may be moree�ective than public sector initiativesÐbut theyrequire strong public sector support.

(c) Combining policies

As Table 1 illustrates, the policy makers inour four study cities used combinations ofseveral of di�erent pollution control policies,rather than simply relying on one or two. Forexample, in Cd. Ju�arez, the key policy wasclearly clean technological change, but thispolicy was buttressed by a program of researchand development, subsidies, an educationalcampaign, a boycott of brickmakers using dirtyfuels, and a command and control prohibitionof dirty fuels. The fact that pollution controlpolicies were not implemented one at a timemakes them di�cult to evaluate. Nevertheless,it is possible to draw some conclusion abouteach.

(d) Command and control process standards

Municipal environmental authorities in eachof our four study cities promulgated commandand control regulations prohibiting the use ofcertain types of fuels. In Cd. Ju�arez andZacatecas, these regulations helped to tempo-rarily dramatically boost propane use, and in

Cd. Ju�arez, Zacatecas and Torreon, they ulti-mately succeeded in permanently eliminatingthe use of particularly dirty fuels such as plas-tics and used tires. Policy makers relied on twostrategies to overcome the di�culty of moni-toring and enforcing these regulations: regis-tration and peer monitoring.

In Saltillo, Zacatecas and Torreon, municipalauthorities compiled registries of informalbrickmakers. In Saltillo, registration wasclearly futile. Brickmakers continued to violateprohibitions on burning tires with impunity. Itis hard to judge the impact that registration hadin Torreon since peer monitoring appears tohave played a strong role in the shift away fromthe dirtiest fuels. By contrast, in Zacatecas,registration undoubtedly had a signi®cante�ect. For a short period, all brickmakers in thecity used propane exclusively and there is littleevidence that peer monitoring or other strate-gies were responsible. But the success of theregistration e�ort in Zacatecas was very likelydue to the fact that there were only about 60kilns in the city. As a result, monitoring was notprohibitively costly. Moreover, brickmakersdid not have the political power to blockenforcement.

Thus, our case studies suggest that in general,simply registering informal polluters is notsu�cient to facilitate enforcement of commandand control regulations. Evidently, the fact thatinformal polluters are anonymous is not theprincipal barrier to enforcement. Rather, thekey obstacles are the high cost of monitoringand the political considerations discussedabove. Registering informal ®rms may giveregulators some added leverage by laying thegroundwork for inspections and ®nes, but itdoes not solve the underlying problem of toofew regulatory resources chasing too many®rms.

Perhaps the single most striking ®nding fromour study is that in each study city, enforce-ment of command and control regulationsdepended critically on peer monitoring. In mostcases, local organizations played a key role. Forexample, in Cd. Ju�arez, trade unions andneighborhood associations imposed sanctionson brickmakers who used certain dirty fuels. Inaddition, to enforce a ban on burning debris,the municipal environmental authority reliedon citizen complaints to identify violators. InSaltillo, the enforcement of a prohibition on theexclusive use of tires depended on peer moni-toring and on the cooperation of the brick-makers' union. Similarly, in Zacatecas,

WORLD DEVELOPMENT2078

brickmakers reported violations of the ban onburning tires to the city environmentalauthority. Finally, in Torreon, demonstrationsand petitions organized by residents of thecommunities surrounding the main brickyardhave been instrumental in getting the brick-maker organizations to agree to ®re only atnight, to limit the number of kilns burning atany given time, and to stop burning tires.

Thus, our case studies suggest that peermonitoring is a necessary condition for e�ec-tive command and control regulation in theinformal sector. They also suggest that peermonitoring is most successful when facilitatedby local organizations. It is important to note,however, that the success of this strategy inour study cities depended on the fact thatneighbors could easily see or smell brick kilnemissions. Peer monitoring would probably beless e�ective for other types of polluters (suchas leather tanneries) whose emissions are lessvisible.

(e) Relocation

Relocation is probably the most costlypollution control strategy for brickmakers. Itrequires them to purchase new land and buildnew kilns. In addition, it usually increasestransportation costs since most brickmakerslive next to their kilns and sell their goodslocally. The only city in our sample where kilnswere actually relocated was Zacatecas whichwas also the only city where brickmakers hadvery little political power. Relocation was nevereven seriously discussed in either Cd. Ju�arez orSaltillo, cities where brickmakers have consid-erable political power. Thus, relocation is onlyfeasible when regulatory authorities enjoyconsiderable bargaining power or have theresources to pay signi®cant subsidies.

(f) Green subsidies and taxes

There were no attempts to use green taxes orsubsidies in any of our study cities. The expla-nation most likely has to do with a number ofpractical considerations. First, all of the pollu-tion control e�orts we studied were led eitherby municipal governments or nongovernmentalorganizations. Neither institution is likely tohave the ®scal resources to provide substantialsustained subsidies. Second, the dirty inputsinto brickmaking that are the appropriatetargets for green taxesÐused tires, plasticwastes, and scrap woodÐare sold on informal

markets, where tax collection institutions areabsent and easily avoided. Third, given the levelof poverty among brickmakers, attempts tosubsidize clean inputs (like propane) wouldlikely induce brickmakers to resell these inputsto make quick pro®ts. In fact, according toregulatory authorities in Cd. Ju�arez, one reasonfederal propane subsidies were lifted in theearly 1990s was to squelch a rampant cross-border black market in propane. Thus, our casestudies suggest that, in general, when informalpolluters buy their inputs in informal markets,green taxes are not feasible.

(g) Boycotts

Although green taxes and subsidies wereabsent in our case studies, boycotts of brick-makers using dirty fuels were attempted in twocities: Cd. Ju�arez and Zacatecas. In both cases,they were utter failures. Buyers simply contin-ued to buy bricks from whomever was sellingat the best price. These experiences suggest thatin most cases, contravening market forces inthe informal sector simply does not work;monitoring is too di�cult and cheating is tooeasy.

(h) Clean technological change

In three of our study cities, Cd. Ju�arez,Zacatecas, and Saltillo, policy makers adoptedpollution control strategies that, temporarily atleast, centered around converting kilns topropane, a process that we have arguedconstitutes technological change. In practice,all of the propane initiatives in our study citiesturned out to di�er in an important way fromwhat is conventionally thought of as cleantechnological change: due to reductions inpropane subsidies, conversion to propaneincreased variable costs rather than reducingthem. Nevertheless, the majority of brickmak-ers in two of our study citiesÐCd. Ju�arez andZacatecasÐadopted propane and continued touse it for over a year. This phenomenon runscounter to the conventional wisdom that to beviable, clean technologies must reduce variablecosts.

Part of the explanation for this phenomenonundoubtedly has to do with the e�ectiveness ofregulatory pressure and peer monitoring. Butanother part of the explanation may have to dowith the interplay between competition andpeer monitoring. The market for bricks is

INFORMAL SECTOR POLLUTION CONTROL 2079

highly competitive and, as a result, brickmakerswho use high-cost clean fuels are liable to beundercut by competitors using dirty fuels.Thus, initially, competition in the market forbricks seems to work against the introductionof cost-increasing clean fuels. But, our casestudies suggest that, ironically, once di�usionof the clean fuel has progressed past a certainstage, competition can work in favor di�usionbecause those who have adopted have anincentive to ensure that their competitors adoptas well. Moreover, adopters generally havesome leverage over those of their competitorswho are neighbors and/or fellow unionmembers. This suggests that, in general, if acritical mass of informal ®rms can be convincedby hook or crook to adopt a cost-increasingclean technology, eventually di�usion canbecome self-perpetuating. One would expectthis dynamic to be strongest in situations wherethe ®rms are geographically and politicallyuni®ed and therefore have some in¯uence overa relatively high percentage of their competi-tors, and to be weakest in situations, wherethere are strong jurisdictional or political divi-sions among ®rms. The observed pattern ofadoption in Cd. Ju�arez was consistent with thisstory. Once an initial cadre of brickmakers hadbeen convinced to adopt, neighbors and fellowunion members quickly followed suit. The samedynamic may have been played out in Zacate-cas, speeded by the fact that the entire pool ofbrickmakers was relatively small. The lessonfor policy makers is that subsidies to earlyadopters may heighten pressures to adopt onother ®rms.

The case studies also suggest lessonsconcerning what types of technologies areappropriate in the informal sector. Projectleaders in Cd. Ju�arez and Saltillo attempted todevelop and di�use new energy-e�cient kilns.In both cities, experimental kilns were designedby highly trained engineers, involved radicaldepartures from existing kilns, and would haverequired brickmakers to ®nance sizable invest-ments in new equipment and in training. Thesee�orts were unsuccessful. By contrast, with thebene®t of the Cd. Ju�arez experience, cityauthorities in Zacatecas promoted the use oflow-technology, low-cost methods of ®ringexisting traditional kilns with propane. Theseexperiences illustrate well-established principalsfor introducing new technologies in low-incomesettings. First, to the extent possible, intendedadopters should participate in designing theinnovation. Second, new technologies must be

``appropriate,'' that is both a�ordable andconsistent with existing levels of technology.

Finally, are there any lessons to be learnedfrom the fact that technological change initia-tives in Cd. Ju�arez, Zacatecas and Saltillo wereundermined by nationwide reductions inpropane subsidies? This might be seen as evi-dence of a failure on the part of the Mexicangovernment to coordinate con¯icting policyinitiatives. While the government-funded e�ortsto convert brickmakers to propane (throughSolidarity Enterprises and NAFIN), it simul-taneously pursued an economic liberalizationprogram that undermined these e�orts. But thisliberalization program was part of a broadeconomic reform and the bene®ts of this reformmay well have outweighed the costs, includingthe environmental costs. To reduce the envi-ronmental costs, the Mexican governmentmight have subsidized propane use by thoseconsumers, who were likely to substitute intodirty fuels. But such a policy would have beendi�cult to implement and almost certainlywould have created a black market in subsi-dized propane.

Should the organizers of the propane initia-tives in each city be blamed for failing torecognize that propane was an economicallyunsustainable option? It seems unfair to faultthe organizers of the Cd. Ju�arez program.Propane prices began to rise only in 1992 bywhich time this initiative had completely orga-nized itself around engineering a switch topropane. But the leaders of the Zacatecas andSaltillo programs might have foreseen thedi�culties of promoting propane since theirprojects were not launched until 1993 and 1994.Their failure to do so may have stemmed fromthe fact that in the early 1990s, the Cd. Ju�arezexperience was being widely touted as a modelinitiative by both its leaders and funders. In1994, with federal ®nancing, the Mexicannonpro®t that spearheaded the Cd. Ju�arezproject established ECO-TEC, a ``national''center for brickmaking training and researchthat strongly advocated conversion to propane.

Hence, the demise of the propane initiativesin three of our study cities holds two lessons.First, in developing economies where inputprices are often unstable, market-based tech-nological change initiatives among enterprisesthat are sensitive to variations in these pricesare bound to be somewhat fragile. Second,intertemporal and place-based factors matter:what works at one time and in one place willnot necessarily be a universal solution.

WORLD DEVELOPMENT2080

(i) Education initiatives

In only one study city, Cd. Ju�arez, did projectleaders attempt to use an informationcampaign about the health hazards associatedwith burning dirty fuels to promote a shift tocleaner fuels. Even this campaign was limited inscope and duration. Yet, statistical analysis of

survey data from Cd. Ju�arez reveals a positivecorrelation between awareness of the healthhazards associated with burning dirty fuels andthe adoption of propane (Blackman &Bannister, 1998). This ®nding suggests thatinformation campaigns regarding the healthimpacts of emissions can bolster pollutioncontrol e�orts.

NOTES

1. Some informal activities such as waste collection

and recycling even have environmental bene®ts (Meyer,

1987).

2. Several authors have noted that even if no pro®table

clean technologies are available, simple low-cost ``good

housekeeping'' measures can enhance pro®tability and

reduce pollution (Bartone & Benavides, 1993; Chiu,

1987).

3. This section is based on a July 1995 survey of 95

brickmakers in Cd. Ju�arez, statistical analysis of that

survey data, a variety of primary and secondary docu-

ments, and interviews with Texan and Mexican stake-

holders including representatives of FEMAP, the Cd.

Ju�arez Municipal Ecology O�ce and the Texas Natural

Resources Conservation Commission. It is distilled from

in-depth analyses of the Brickmakers' Project presented

in Blackman and Bannister (1997, 1998), which contain

complete bibliographic information.

4. In 1995, the city of El Paso was classi®ed by the US

Environmental Protection Agency as a ``moderate''

nonattainment area for both carbon monoxide and

particulate matter, and El Paso county was classi®ed as a

``serious'' nonattainment area for ozone.

5. This section is based on interviews with Secretary,

Subdirector and Director of the Municipal Ecology

O�ce of Saltillo (16 and 17 July 1996), documents

provided by these three o�cials and interviews with four

brickmakers in the La Rosa and Guayulera districts

(16 and 17 July 1996).

6. Tiles and bricks are usually ®red simultaneously.

The soil in Saltillo is particularly well suited to tile

making.

7. The city government established a fund of 50,000

pesos (US $17,000). The state government was recruited

to provide matching funds. With the cooperation of

Solidarity Enterprises, the same federal program that

funded the Cd. Ju�arez initiative, this funding was used to

leverage a 1,000,000 pesos (US $333,000) loan fund from

NAFIN, the federal development bank. All of the funds

were earmarked for brickmakers investments in propane

equipment.

8. This section is based on interviews with the Director

of the Solidarity Enterprises o�ce in Zacatecas (19 July

1996), primary documents and newspaper clippings

provided by this o�ce, and interviews with seven

brickmakers in Zacatecas and Guadalupe (18 and 19

July 1996).

9. The municipalities were Jerez, Ojo Caliente, Guada-

lupe, Tlaltenango, and Fesnillo.

10. This section is based on interviews with the

Director General of Economic Development and the

Director General of Public Services and Ecology for the

Municipality of Torreon (23 and 24 July 1996), docu-

ments provided by these o�cials, and interviews with

®ve brickmakers of the ejido San Antonio (23 and 24 July

1996).

REFERENCES

Bartone, C. R., & Benavides, L. (1993). Local manage-ment of hazardous wastes from small-scale and cottageindustries. World Bank, Washington, DC. Paperpresented at the 5th Paci®c Basin Conference onHazardous Waste, Honolulu, Hawaii, 8±12 Novem-ber.

Biller, D. (1994). Informal gold mining and mercurypollution in Brazil. Policy Research Paper 1304.World Bank, Washington, DC.

Biller, D., & Quintero, J. D. (1995). Policy options toaddress informal sector contamination in Latin Amer-ica: the case of leather tanneries in Bogota, Colombia.

INFORMAL SECTOR POLLUTION CONTROL 2081

LATEN Dissemination Note 14, World Bank,Washington, DC.

Blackman, A., & Bannister, G. J. (1997). Pollutioncontrol in the informal sector: the Ciudad Ju�arezBrickmakers' Project. Natural Resources Journal, 37,829±856.

Blackman, A., & Bannister, G. J. (1998). Communitypressure and clean technology in the informalsector: an econometric analysis of the adoption ofpropane by traditional Mexican brickmakers. Jour-nal of Environmental Economics and Management,35, 1±21.

Blackman, A., & Harrington, W. (2000). The use ofeconomic incentives in developing countries: inter-national experience with industrial air pollution.Journal of Environment and Development, 9, 5±44.

Blackman, A., Newbold, S., Shih, J. -S., & Cook, J.(2000). The bene®ts and costs of informal sectorpollution control: traditional Mexican brick kilns.Mimeo, Washington, DC: Resources for the Future.

Chiu, H. (1987). Pollution control: a blessing in disguise?Industry and Environment, 10, 3±5.

Chiu, H., & Tsang, K. (1990). Reduction of treatmentcosts by using communal treatment facilities. WasteManagement and Research, 8, 165±167.

Development Research Group, World Bank. (1999).Greening industry: New roles for communities, mar-kets, and governments. New York: Oxford UniversityPress.

El Norte. (1994). Government seeks to eradicatecontaminating kilns. March 9, C1.

Eskeland, G., & Jimenez, E. (1992). Policy instrumentsfor pollution control in developing countries. WorldBank Research Observer, 7, 145±169.

Eskeland, G., & Devarajan, S. (1996). Taxing bads bytaxing goods: pollution control with presumptivecharges. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Johnson, A., Soto, J. Jr., & Ward, J. B. (1994).Successful modernization of an ancient industry: thebrickmakers of Cd. Ju�arez, Mexico. El Paso NaturalGas, El Paso, TX. Presented at the New MexicoConference on the Environment, April.

Kent, L. (1991). The relationship between small enter-prises and environmental degradation in the developingworld with emphasis on Asia. Washington, DC:USAID.

Meyer, G. (1987). Waste recycling as a livelihood in theinformal sector: the example of refuse collectors inCairo. Applied Geography, 30, 82±92.

O'Connor, D. (1996). Managing the environment withrapid industrialization: lessons from the East Asianexperience. Paris: OECD.

Omuta, G. (1986). The urban informal sector andenvironmental sanitation in Nigeria: the needlesscon¯ict. Habitat International, 10, 179±187.

Okasaki, M. (1987). Pollution abatement and controltechnologies for small and medium scale metal®nishing industry. Industry and Environment, 10,23±28.

Perera, L., & Amin, A. (1996). Accommodating theinformal sector: a strategy for urban environmentalmanagement. Journal of Environmental Management,46, 3±14.

Ranis, G., & Stewart, F. (1994). V-goods and the role ofthe urban informal sector in development. EconomicGrowth Center Discussion Paper No. 724. YaleUniversity, Haven, CT.

Sethuraman, S. V., & Ahmed, A. (1992). Urbanization,employment and the environment. In A. S. Bhalla(Ed.), Environment, employment and development(pp. 121±141). Geneva: ILO.

Tietenberg, T. (1998). Public disclosure for pollutioncontrol. Environmental and Resource Economics, 11,587±602.

WORLD DEVELOPMENT2082