Immanence and Collage Heuristics

Transcript of Immanence and Collage Heuristics

Immanence and Collage Heuristics

Maria-Carolina Cambre

Visual Arts Research, Volume 39, Number 1, Issue 76, Summer 2013,pp. 70-89 (Article)

Published by University of Illinois Press

For additional information about this article

Access provided by Western Ontario, Univ of (26 Sep 2013 11:39 GMT)

http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/var/summary/v039/39.1.cambre.html

70 Visual Arts Research Volume 39, Number 1 Summer 2013

© 2013 by the Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois

Immanence and Collage Heuristics

This paper explores the pedagogical affordances and limitations of the philosophy of im-manence, and by extension, the concepts of multiplicity and the virtual as elaborated by Deleuze and Guattari (1983, 1994) through collage. By elaborating the collage onto-epistemology, and an exercise of looking at collage, I will explore how immanence as well as the virtual are interacting pedagogically to co-create (both forming and inform-ing) the viewer. Thus the paper has three aspects, an interaction with a specific collage and an examination of its onto-epistemic principles. Also I elaborate (with reference to the same piece) on the conceptual level and theorize the salience of the construct of multiplicity as an engagement with the piece. Finally, I offer a teasing out of what the pedagogical implications of understanding collage through this lens might offer.

No education that is not founded on art will ever succeed. —Margaret Mead

When I visually attend to the collage fragment in Figure 1, my imaginative con-sciousness is engaged. Splashing and rubbing colors, primary ones dominating; lines crisscross and overlap; and images exceed the frame not only laterally and horizontally but also vertically, like an opaque palimpsest in layers and covering one another, interrupting each other’s surfaces. Inconsistent drips mark the sur-face. This fragment, photographically ripped from a larger collage, moves, ques-tions, and above all interacts with those who allow themselves to be challenged to immerse themselves, become part of, or participate in its particular assemblage of provocations. Drawn in, I am mentally “filling in” some of the gaps; my eyes are drawn along lines to see what might be beyond their abrupt endings. How many

Maria-Carolina Cambre King’s University College at Western University Ontario

71

layers are there? What is covered, and how do those hidden layers agitate or dis-turb the surface? How am I to see? Immanence, following Deleuze and Guattari’s core epistemological posi-tion, conceives moments as ever-changing flows of forces in relation to one an-other where they gain traction under conditions that provide material evidence of these forces. These forces flow from how they have been previously arranged. For example, a particular knowledge structure such as an understanding of col-lage as an artistic approach with a history and sets of related concepts linked to it, forms and is formed by material objects such as artworks themselves, as well as all the elements that could be included in a work, and the desires of persons such as the viewers and artists who add their particular inflections. Always resist-ing definitions and preferring instead to have their theoretical constructs enact and become through multiple examples, Deleuze and Guattari describe imma-nence in terms of what it is not:

It is not a method, since every method is concerned with concepts and pre-supposes such an image. . . . Nor is it opinions held about thought, about its forms, ends, and means, at a particular moment. The image of thought implies a strict division between fact and right: what pertains to thought as such must

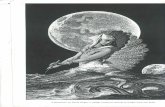

Figure 1. M-C Cambre, Chenigma, fragment 1, 2010 [Mixed media]. Chenigma Fragment plus a number indi-cates a title for each photograph as a separate and standalone piece. All photos are by M.-C. Chambre.

Maria-Carolina Cambre Immanence and Collage Heuristics

72 Visual Arts Research Summer 2013

be distinguished from contingent features of the brain or historical opinion. . . . Are contemplating, reflecting, or communicating anything more than opinions held about thought at a particular time and in a particular civilization? (Deleuze & Guattari, 1994, p. 37)

Thus both discursive and non-discursive elements as well as ruptures and contin-gencies are explored from the onto-epistemological stance afforded by immanence. An immanent exploration complicates and problematizes notions such as art, art-work, artist, teaching, learning, and their development. My argument is that collage is particularly well suited for research that persistently troubles its own existence by acknowledging the virtual forces that both constitute and condition its insights. The collage as assemblage, that is to say “emergent unities that nonetheless respect the heterogeneity of their components,”1 is in many ways a wasp and an orchid, following one of Gilles Deleuze’s preferred examples: Where does one begin and the other end? Are they not always already in a process of becoming or co-creating each other? Just as each fragment in a collage interpellates one’s par-ticipation, wasp-like in seeing or collecting (bringing together) elements and their

Figure 2. M.-C. Cambre, 2010, Chenigma, fragment 2

[Mixed media].

73

interactions that not only manifest once entered but are actually created at that moment as are we in becoming-viewers. The moment of seeing provides temporal traction for cross-fertilization generating wonderings and a space of thoughtful play, or pedagogy where actions are not presumed to be causal. The collage art form requires renewed attention and begs the reconside-ration of the metaphors of “diversity” and “heterogeneity” it so often evokes. It tempts viewers to explicate with a “reading” or a “deconstruction,” since much of academic training relies on these approaches. One would be mistaken, however, to remain within these boundaries. Collage as multiplicity (Deleuze & Guattari, 1983, p. 24) calls for an altogether different response. Similarly, artistic pedagogy emphasizes relational and contextual understandings over atomized information, holism over hierarchies of epistemology, participation over institutionalized exper-tise, and rejects the artificial separation of research and daily life. To this end, I will explore some ontological and epistemological features and challenges of collage. These ideas emerged—or better, were co-created—through a collage making process, in other words, research. Work that in this case manifests itself in a visual and artistic collage, as well as a textual and verbal one, with readings and words from many writers modifying and being re-framed themselves in the process. My particular story of the processes and emergence of a collaborative collage and its correspondence with the process-oriented philosophy of Gilles Deleuze seemed to begin with an investigation of the famous photograph of Che Guevara called the “Guerrillero Heroico.” Consider this essay not an expla-nation of the collage itself but rather an invitation to continue its co-creation. There is only one image of Che Guevara amongst the many that were taken of him that is preferred as a calling card for protesters around the world “seeking affective forms of resistance outside of those determined by the social order itself ” (Sandoval, 2000, p. 45). To some extent, each person creating, modifying, appro-priating or using the Guerrillero Heroico taken by Alberto Korda in 1960, whether in the interests of social justice or not, becomes part of a global collage of Che Guevara portraits. While this global collage is not a concrete unitary entity, it is real, yet virtual, in the sense that every Guevara image that “spins off” the original photograph in some way is linked to all the others and engaged in a visual dia-logue that no one fragment is entirely privy to. Why does this imaging become sa-lient today in so many places? What is its work? What is its becoming? How is it a response? The Deleuzian philosophy of Immanence tells us that it is both one and multiple; that its appearance (its zone of clear distinctions, its actualizations) is al-ways surrounded by the imperceptible mist of the virtual, all the other immaterial images always in dialogue and speaking with/in/through this image, each relating with the role of an-other, and yet indiscernible from it. Virtual, yet real but not concrete: The real as never completely divided is thus immanent.

Maria-Carolina Cambre Immanence and Collage Heuristics

74 Visual Arts Research Summer 2013

The responsive viewer is an effect of the image, that is to say, springs from her participation in the image, receiving what is given and adding something from herself anonymously or where the boundaries where one begins and the other ends are undecidable. This kind of expression of the image helps us conceive the principle of self-differentiation of the one, the expression of the one in the mate-rial world. The emanation is what makes the Deleuzian (and Spinozist) approach to Immanence a philosophy with a long and complex history, an appropriate one. And it is viewers as effects of the image both virtual and concrete at the same time who give the image life. It may flash into conscious awareness, and it may also be-come another rendering, a concretization of that direction taken from the image. It can actually be described as an alchemical process of transformation. Thus, following this image’s movements by learning through the artistic method of collaging, and a conscious surrendering to the creative process, is the experience of the image itself and its community of interlocutors who are my teachers. Additionally, working through artistic methods facilitates a transmuta-tional process of investigation and education: as cultural anthropologist Alfred Gell tells us: “The essential alchemy of art is to make what is not out of what is, and to make what is out of what is not” (as cited in Hazan, 2001, p. 8). The mak-er does not escape from this process of metamorphosis. Creative consciousness evolves and/or erupts in the maker by and through the process of creating the work. Creativity, in a Deleuzian view, “must be understood as being distributed across an immanent plateau of incessantly creative repetitions . . . a wholly inter-dependent, ongoing, and modestly evolving everyday event” (Tiessen, 2012, p. 2) as difference and repetition. In this sense, one might proclaim the end of the artist as agentic individual or at least an end to the artist-genius narrative. What must be recognized is that in this view, every “expression of creativity or creation is an expression of, at the very least, co-creativity or co-creation” (Tiessen, 2012, p. 6) across time and space. The artist is dead. Long live the artist.

Understanding the Collage Form: An Onto-Epistemology

Crucial to the art-making process is the ceding of control and allowing things to happen. When creating/being created by a collage, I notice that different pieces of the fragmented images seem to resonate more strongly with each other than others. Some images and fragments, I notice for the first time, although they have been present from the beginning. When I move them and they occupy a different relation to materials around them, something starts to happen: ideas surface.2 At the same time, other images become less interesting and seem to fade away from my awareness. Throughout, the resonances between fragments and materials are in

75

flux and actively influencing the direction of the work as it progresses. Opportuni-ties are characteristically emergent, as in any creative process, where the surprise of new options are always about to become possible. In the case of collage, however, it seems these choices are exceptionally abundant, with each torn edge having a fractal-like virtual presence inviting responses. Just as the images based on the Guerrillero Heroico are inexhaustible and belong to no one location or identity but still respond to a set of coordinates with respect to meaning-construction, the work of collage has those torn edges calling to the missing pieces while reconfiguring the fragment as part of another image. Collage honors fragments by listening to how they call to one another, and in so doing creates a space of play.3 Ideas are ever-emerging as active documentation, with the ever-present chance they may later be layered over or altered, at the same time a “set of coordinates” is evolving with categories, dimensions/scales, and interpretive possibilities opening through “contextual aptness” and “economy of means” (Brockelman, 2001, p. 224). Collage, intentionally led by experimental and creative practices, assumes certain properties as ontologically essential. The final collage is not always ab-stract although we can see that the composite pieces have been abstracted from their original context. Materials may or may not be pictorial and textual rep-resentations of recognizable objects. For example, a paint chip doesn’t represent a recognizable object; it is the object. When placed next to each other, however, these materials may modify their earlier intimations by creating new constella-tions of possibilities. Thus the connective yet generatively fractal-like principle of multiplicity is the core of the collage onto-epistemology. In Two Regimes of Madness, Deleuze (2006) writes:

Multiplicities are reality itself. They do not presuppose unity of any kind, do not add up to a totality, and do not refer to a subject. Subjectivations, totalizations, and unifications are in fact processes which are produced and appear in multi-plicities. The main features of multiplicities are: their elements, which are singu-larities; their relations, which are becomings; their events, which are haecceities (in other words, subjectless individuations); their space-time, which is smooth spaces and times; their model of actualization, which is the rhizome (as opposed to the tree as model); their plane of composition, which is a plateau (continuous zones of intensity); and the vectors which traverse them, constituting territories and degrees of deterritorialization. (p. 310)

In a collage, each fragment has more than one being, or life, and participates in multiple dialogues. In a sense, each fragment can be said to be heterotopic by providing a space within a space and gesturing to a beyond. But even this spatial conceptualization is exceeded by the heterotemporality infusing its every iteration.

Maria-Carolina Cambre Immanence and Collage Heuristics

76 Visual Arts Research Summer 2013

Non-Closure and Foregrounding Constructedness

Non-closure, in the sense that something can be added or removed without ne-cessarily making the piece look more or less finished, is another core ontological property. The property of non-closure is intimately related to that of multiplicity but is focused more on the possible combinations. When is a collage finished? One might claim it is done when the maker wants, or when it is framed and dis-played and yet, the “indeterminacy of collage, its compositional narrative, does not gel fully. As such, ‘concrescence is, in effect, never finished, however much there may be the illusion of completeness . . . the incongruous effect of . . . co-llage is based directly on its incompleteness, on the sense of perpetual becoming that animates it’” (Kuspit, 1983, pp. 127–128), and thus honors relatedness while still respecting all the absent fragments that correspond to those included in the piece. It challenges our preconceptions of the boundedness of an artwork with a vision of repeatedly renegotiated relationship. It is a way of being that understands relationships as processes of coordination that precede the very concept of a work

Figure 3. M.-C. Cambre, 2010, Chenigma, fragment

3 [Mixed media].

77

or a self as separate. Any gesture toward closure in a collage is an illusion and im-possibility because, following a rhizomatic logic, no fragment exists in a hierarchy above or below any other. It may be that color or size of some element dominates. For example, in the fragment in Figure 3, the cut-out of the woman and man gesturing near the bottom may attract the eye for various reasons, but the interior logic of the piece does not rest comfortably in the unitary. Its multiple elements call for the viewer’s contemplation and compete for her attention. The focus is on its ongoing-ness. While closure is imaginary, since fragments cannot be privileged: meaning-ful possibilities are created between them and only their relations to each other define them. Collage is relational internally and externally, requiring the maker and/or responsive viewer to think or act modally, as one does when engaging in performative speech (such as a vow or promise, to say it is also to do it). Thus, capacities for meaning making or action do not pre-exist their emergence and are “brought into being by relations,” and are at each moment granted their “identifi-able characteristics by unfolding and ongoing processes of relationality” (Tiessen, 2012, p. 7). Because meaning construction with/in collage requires a “metatran-sitive relationship” between agents/affects, acts, and/or effects at once productive of change on one another and “constitutive of a particular kind of agent . . . by means of an action” (White, as cited in Sandoval 2000, p. 155), a specific mode of consciousness can emerge. This consciousness is crucial to interacting with the form of collage as an intervention in social reality: as the agent (viewer/artist/affect/force) provokes expression through a bi-directional action (relation) on the collage and at the same time on oneself, oscillating back and forth. Sandoval (2000) insists “it is only in action and by action that the practitioner can be said to exist”4 (p. 155) or come into being. The agent both acts and is acted upon simul-taneously and “calls up a new morality of form that intervenes in social reality5 through deploying an action that re-creates the agent even as the agent is creating the action—in an ongoing, chiasmic loop of transformation” (Sandoval, 2000, p. 185). Although the artistic process can be more emergent than deliberate, the intu-itive choices are part of the evocative meaning-making structure (Norris, Mbokazi, Rorke, Goba, & Mitchell, 2007, p. 495).

Pedagogical Non-Representation

In Deleuze’s work, one of the central projects is to invent new images of thought to put in place of the classical system of representation of theoretical thought: “[T]his is a pragmatic perspective from which Deleuze never deviated—philosophy aims not at stating the conditions of knowledge qua representation, but at finding and fos-tering the conditions of creative production” (Smith & Protevi, 2011). Heuristically,

Maria-Carolina Cambre Immanence and Collage Heuristics

78 Visual Arts Research Summer 2013

collage never fails to engage the shadow of doubt by resisting representation. Brock-elman (2001) helps us understand this property of resisting representation: “[C]ollage problematizes any view of art as medium for truth [and] is both representa-tional and antirepresentational. . . . On account of its representational peculiarity, collage questions dogmatisms of all kinds” (p. 7). What else does collage drag with it and bring? There is, “in collage a compelling rethinking of philosophical issues of truth and history that has otherwise failed to gain adequate articulation” (p. 8). For example, in World War II Germany, collage emerged as an art form to criticize Adolf Hitler and was recognized as having an anti-fascist political stance. It is widely known that artists such as John Heartfield, and some members of the Berlin Dada group were pioneers in critical collage and photomontage and were forced to flee from Nazi persecution. In an in-depth analysis of the political praxis of John Heart-field’s collage, Spence (1981) writes about how juxtaposed elements set the viewer’s thoughts in motion as she seeks to resolve the enigma they present. This enigma cannot, however, be solved within representation because its solution lies outside the montage in the world of political action and struggle. Drawing on Brecht’s theory of distanciation,6 Stephen Heath views Heartfield as questioning so-called commonsense beliefs by restructuring signs in such a way that he “punctuates ‘rep-resentation’ with ‘formulation,’ a process Brecht refers to as ‘literarization.’ This then is not ‘a form but a mode of analysis, the very mode of understanding . . . where the spectator is placed in a critical position” (Spence, 1981, pp. 5–6). Again, form itself is already a mode of analysis. Additionally, the collage art form, in the vernacular sense I am discussing it here, is one that has emerged worldwide; it has no one nationality, no one home—from flower arrangements to quilts—essentially collage finds home in exile, like its many fragmentary components (who nonetheless call to each other), and like the image of Che himself. Another feature of collage is its foregrounding of its own constructedness and artifice as well as the aspects of non-form vital to the style. Again, it pushes forward the viewer’s necessary par-ticipation in creating meanings from his/her experience. When one creates space by revealing the evidence of surgery, textual scars, or imperfect seals in a piece of writing or art, which is not open in the sense of being lost but has openings, one also makes it possible for something to happen in that space. We can un-derstand, then, the form itself as meaningful and calling upon the viewer to act while creating opportunities to learn. Deleuze (1995) understands this space as a place where meanings can come to be. “Things and thoughts,” he writes, “ad-vance or grow out from the middle, and that’s where you have to get to work, that’s where everything unfolds” (p. 161). The space of the opening is a pres-ent-non-presence, a place of possibility where the impossible can be/come and the reach of the creative arena expanded.

79

Form in its widest meaning, the visible universe that envelops our senses, its counterpart, the invisible one that agitates our mind with visions bred on sense by fancy, are the element and the realm of invention; it discovers, selects, com-bines the possible, the probable, the known, in a mode that strikes with an air of truth and novelty at once. (Hammacher, 1981, p. 45; emphasis added)

Hammacher’s (1981) counterpart to form, invisible and agitating at the same time, always becoming, in process, and in relation to the visible (form) is considered vital to invention.7

Pedagogically, the non-form that is constitutive of collage as a form reminds us of how inextricable form and content are. The creation of relationships is cen-tral and thus, borders between elements that may appear to be separate are blurred by their relationality. It may be stating the obvious, but to underline, the mate-riality of experience is profoundly pedagogical, as Ellsworth (2005) insists when she writes about sensations as vital to learning. As such, the form (relations with time, space, bodies, and objects) must be considered part and parcel of content (learn-ing/knowledge/understanding).

Figure 4. M.-C. Cambre, 2010, Chenigma, fragment 4 [Mixed media].

Maria-Carolina Cambre Immanence and Collage Heuristics

80 Visual Arts Research Summer 2013

Recognizing collage as something not completely open-ended, but resisting closure by containing openings, allows us to attend to non-discursive elements and glean potential, albeit uncertain, meaning from them. These fragments/spaces are like a broken frame through which spirits can enter and perhaps play. A Deleuzian perspective might identify them as conditions for the genesis of possible representa-tional knowledge. In other words, they are the virtual aspect of the real awaiting actualization. Breaks in an image’s continuity disrupt its unison and make viewers stop temporarily, whether to imply emphasis, critique, or to denote a change in di-rection or form. With these ideas in mind, we can examine apparent interruptions and physical dis-unities and ask what is present in the non-presence of these fissures. Thus, the figured aspects become no more or less interesting than the not figured, or not presented. It is important to recognize that the pieces comprising the collage are acting both individually in their own right as well as in relation to the other pieces with which they coexist. Everything is relational and interconnected. Within and be-tween pieces is the idea/act of collage that allows for them to both form and inform each other in productive ways. Additionally, the device of repetition (if used) can function rhetorically as a trope to emphasize something, or it can further the notion of an incomplete discursive space, paradoxically tracing inscriptions and indirectly dismantling the idea of artist as singular. It is also, for Deleuze, fundamentally crea-tive in that each repetition produces a difference that is somehow new or novel. In sum, it is vital to recall the paradox that collage brings together interpret-ability while denying any satisfying explanation because it “demands attention to each of the individual elements as individual. . . . [W]e can’t just look at the pic-ture; instead, we must figure it out” (Brockelman, 2001, p. 134). Viewers of collage are not given direction but space, and they are invited to act: this is a powerful pedagogy. In collage, any figure can function simultaneously as the field for anoth-er figure, positioning can inform the surface, and though certain directions may be privileged, they are never univocal or final. Thus, collage gathers materials from different worlds into a single (yet mul-tiple) composition demanding a fractally multiplying reading of its element. It is a postproduction art form that “testifies to a willingness to inscribe the work of art within a network of signs and significations, instead of considering it an au-tonomous or original form” (Bourriaud, 2005, p. 16). If each element has at least a double reading, then the interpretations of relationships between elements cor-respondingly multiply. It is multi-phonic and borderline, full of intersecting and ruptured lines. Each fragment is a multiplicity (Deleuze & Guattari, 1983, p. 24) under the rubric of the one and the many while simultaneously generating further multiplicities virtually present, and ready to emerge in a co-creative process with a viewer. Philosophically, collage negates all static space for epistemological reflec-tion (Brockelman, 2001, p. 49). No dogmatic static or entrenchment of hierarchies is permitted in the collage as theoretical framework.

81

The multi-phonic possibilities created through collage are rooted in the act of juxtaposition: “mixing up the earnest, eccentric, unpredictable, and ludicrous elements” and “present[ing] juxtapositions of images and gaps, theories and de-scriptions” (Hooke, 2001, pp. 14, 13). It is built on principles of juxtaposition, on the interplay of fragments from multiple sources, whose piecing together creates connections and insights that form the basis of discussion and learning. The very nature of collage is interdisciplinary, juxtaposing multiple fields of endeavor and situating the practitioner and his or her work within and between them (Brockel-man, 2001). Additionally the oscillating dynamic movement between an awareness of fragments and origins on the one hand, and a unified meaning on the other, goes beyond static representation to an animated sense of the relationships be-tween meanings, as when one views a calligram, that is core to the collage experi-ence and the epistemological shift of uncertainty as knowledge. I see this uncertainty as a resistance to the desire to define and pin down a unified meaning of the artwork. It is the ability and willingness to hold uncer-tainty that permits experience to take on a pedagogical aspect. Collage seems to manifest an auto-critique containing its own antagonists in an undisguised strug-gle within itself. By virtue of its very form, collage becomes a way of questioning the idea of representation itself. It is, by nature, political and has a “revolutionary task.” Cubists used collage to reveal an ambivalent attitude toward art as a com-modity and condemn readings that excluded further or multiple interpretations. Viewers are invited to remain working through questions and always in a state of becoming-viewers or co-creators through the collage gesture that contains peda-gogical and oppositional elements so that collage mirrors them in the ambiguity of doubt in a move as fruitful as it is unsettling. In many ways, collage might be the ultimate vernacular form both in terms of its immediacy and its accessibility.8

This Is Not a Conclusion

The art process is not meant to merely illustrate theory but to be a theoretical exploration in and of itself for the becoming-viewer in the process of creation and whose vision is a dynamic, reflexive, and self-critical moment. This appreciation of the embeddedness of ideas or practices in their contexts sets the stage for us to en-counter ideas or practices in their complexity, not their individuality. Thus, I echo Roland Barthes in removing myself from Narrative (Sandoval, 2000, pp. 143–144) when he defiantly describes how he does not define his relations with the objects he observes and studies: the film, the restaurant, the painting. Likewise, however much I may approach or gesture toward understandings of Guevara’s image,9 and learn about it/myself through collage, I do not manage to explicate, define, or manage my relations with it, nor should I. The image always already exceeds any one rendering or relation.

Maria-Carolina Cambre Immanence and Collage Heuristics

82 Visual Arts Research Summer 2013

Approaching the Guerrillero Heroico through collage works as recognition of the thousands that have participated in the virtual global collage that Guevara’s image has become, pays tribute to my desire to witness, through their struggles as well as his. As a mobile oppositional form, the piece plays its own part in the agitation for a revolutionary consciousness that can intervene in the forces of neo-colonizing postmodernism. Because collage embraces the very limits of figura-tion, it participates in a kind of decentred psychic terrain with the potential to be radically pedagogical. Despite this capability, the banality of so many approaches to collage today also show how it can become its own form of domination just like any art form that is rendered superficial and co-opted for mercantile purposes and stripped of its politics. However, the multiplicity foregrounded and made explicit in collage is always working against the rigor mortis of one preferred and commer-cially viable interpretation. Therefore, the question is not about what the collage consists of or what it might mean. Rather, it is about what it does as a form that brings together ontolo-gy and epistemology in the form of an immanent exploration and a visual gesture toward the concept of immanence itself. As an event, collage embodies a rupture in the taken for granted: things, fragments, whether they be cardboard cutouts, paint drips, or found objects, are reconfigured within the collage and yet explicitly exceed it. Its ways of becoming and knowing (or onto-epistemologies) are anti-representational (undecideable and unfinished), generative (always becoming), and pedagogically disjunctive. In these ways, it rewires or redistributes the sensible for different forms of action and reaction. Collage in particular can be seen as an art form that “draws its own audi-ence forth, calls a people into being. . . . [S]uch art is not just made for an existing subject in the world, but to draw forth a new subject from within that which is already in place” (O’Sullivan, 2010, p. 204). Collage provides a unique and powerful tactic evoking a “differential oppo-sitional consciousness” where “one can depend on no (traditional) mode of belief in one’s own subject position or ideology; nevertheless, such positions and beliefs are called up and utilized in order to constitute whatever forms of subjectivity are necessary to act in an also (now obviously) constituted social world” (Sandoval, 2000, p. 31). The differential form of oppositional consciousness fostered by col-lage self-consciously and explicitly generates counter-narratives that work toward a non-narrative mode; that is to say, narrative is an ever-disintegrating means to resist narrative itself and thus encourage viewers to reconsider the constructedness of dominant narratives and their masked fragility. These three ways of being and knowing, anti-representational (undecidea-ble/unfinished), generative (always becoming), and pedagogical disjunction, at the core of collage oblige becoming-viewers into active participation. They are forced

83

to become self-aware of the process of seeing and viewing as performative subjec-tivity. No single notion of representation can settle in as the image. Compelled to imagine links and relations between disparate sites, viewers become what Nicolas Bourriaud (2005) calls “semionauts” who navigate new topologies of knowledge because: “This recycling of sounds, images, and forms implies incessant navigation within the meanderings of cultural history, navigation which itself becomes the subject [and mode] of artistic practice” (p. 18) and of learning. But a compass is necessary for this journey because taken alone, these three aspects of collage are in danger of permitting cooptation, or “the unhinging of consciousness from its political commitment to the differential mode, permits any oppositional practice to become only another version of dominant ideology, another version of suprem-acism” (Sandoval, 2000, p. 183). A fourth imperative and indispensable element must be suffused throughout and provide a point of reference, though not necessarily a static one. I refer here to that specific force of affect described as revolutionary love that Che Guevara so famously identified as the quality necessary to guide a true revolutionary. For Sandoval (2000) this “love is understood as affinity” (p. 170). With this kind of compass then, “subjectivity becomes freed from ideology as it ties and binds reality . . . a mixture that lives through differential movement” (p. 170; original emphasis). Following Tiessen (2012), affect, in this case, is understood as being the affecting power of the encountering itself, “a power that has no location but rather is loca-tion (by providing and conditioning it)” (p. 4). Just as Sandoval’s (2000) technologies for The Methodology of the Oppressed “comprise a hermeneutic for defining and enacting oppositional social action as a mode of ‘love’ in the postmodern world” (p. 147), collage onto-epistemology invites becoming-viewers/artists to emerge differently with this love as their guide. Additionally, assuming that art is always “a collective enunciation and an expres-sion of unknowable forces of differentiation . . . what we refer to as an artist is always an expression or an effect of affective forces of multiple everyday pressures that repetitively differentiate from one moment to the next” (Tiessen, 2012, p. 7). As anti-representational (undecideable/unfinished) form, collage resists representation. It is always the case that something could be added or taken away while still fitting in with the work’s essence. Being thus always broken and in-complete, it transforms a disadvantage into a new benefit. It responds to actual experiences of deprivation and political powerlessness and fragmentation but presents the wound, the break, as a place where critical intervention can occur for anyone; it is fundamentally democratic. Kurt Schwitters,10 recognized as one of the 20th century’s greatest masters of collage, was able to see that “[e]verything had broken down and new things had to be made out of the pieces. Collage was like an image of the revolution within me—not as it was but as it might have been”

Maria-Carolina Cambre Immanence and Collage Heuristics

84 Visual Arts Research Summer 2013

(Dietrich, 1993, pp. 6–7). His revolution is motivated by the kind of hermeneu-tic love Guevara spoke of, one that envisions another world and its possibilities. Brockelman (2001) also detects that, “Schwitters’ . . . conviction that the purpose of collage is not to represent the nature of capitalist phantasmagoria to the viewer . . . rather to transform . . . to [be] an active participant in it” (p. 47) and reinforc-es the anti-representational bent at the root of its being. In refusing to represent any kind of illusory wholeness, collage unmasks the constructed nature of narrative, discourse, and other representational forms. But collage resists in multiple ways, which serve to enhance its efficacy as a form, and so I turn to the second essential onto-epistemological trait of generativity. In Collagemachine, Kerne (2001) tells us that “[t]he findings of creative cognition research indicate that the methods of semiotic collage artists promote emergence and creativity both for the artist and for the audience.” Collage is always becoming because it provides multiple interpretive paths for the viewer’s eyes to follow and one may easily see the same work as completely different on another occasion. Often the artist will show preference for one of these paths, but there is no way to compromise the heterogeneity guaranteed by the very form of collage. Thus, it may imply “that there is a conceptual space for truth but only to the extent that it validates the proposition ‘there is no truth’” but this space of truth “is itself a

Figure 5. M.-C. Cambre, 2010, Chenigma, fragment 5 [Mixed media].

85

generated space” (Brockelman, 2001, p. 54). In the cross-currents of the temporal unfolding of collage, hybrids form and provoke new ways of interpreting infor-mation. The generative trait of collage, as Deleuzian multiplicity, like the quality of undecideability, ensures resistance to representation because it provides a riddle rather than a clear relationship; it is a piece of newspaper as-if a table, but instead of choosing one or the other, it oscillates between them. It rejects dominant “ei-ther/or” alternatives by saying “I stubbornly choose not to choose, I choose drift-ing: I continue” (as cited in Sandoval, 2000, p. 143). So how can these disjunctions be considered pedagogical? How can all this fragmentation be coherent enough at any one moment to permit action? Collage helps us recall that fragmentation is not an experience or a notion specific to an age or era. Just the opposite is true: “The scapegoated, marginalized, enslaved and colonized of every community have also experienced and theorized this shattering, this splitting of signifieds from their signifiers” (Sandoval, 2000, p. 35). The gap, or plane of immanence, provides an uncolonized space, but it cannot be inhabited, only evoked and passed through. The disassociation afforded by the disjunctive discursive strategies of collage is a pedagogical necessity in fostering critical thinking. A collage’s mode of ad-dress resists quick and easy conclusions. The discontinuity of its differing images and ideas indicates a preference for an analytic dialogue versus a communicative one. The oscillating, slippery, and unpredictable characteristics of analytic dia-logue allow for diverse perspectives and unlimited creative possibilities unlike communicative dialogue, which pushes resolution out of a need to pin down meaning (Ellsworth 1997; Garoian & Gaudelius, 2008). Taking up the art form of collage as an iteration of a particular onto-epistemological stance is, as Tiessen (2012) rightly observes,

[t]o acknowledge, then, that how we understand the mechanics of creativity—how art comes into being, for example—always betrays our ontological commit-ments in so far as ontologies are by definition logics we use to understand the nature of being and becoming, the nature of how reality itself is and comes into being. (p. 2)

The ethic guiding the onto-epistemological process behind any hermeneutic of col-lage’s properties of being anti-representational (undecideable/unfinished), generative (always becoming), and pedagogical disjunction is the elective affinity and virtual presence of love. In other words, it is an immanent evaluation (ethic). Sandoval (2000) writes that “love as social movement is enacted by revolutionary, mobile, and global coalitions of citizen-activists who are allied through the apparatus of emanci-pation” (p. 184). Similarly, those choosing to render or reproduce the image of Che Guevara participate in a global collage. Though they may not have expressed it to themselves in that manner, they are also coalescing via this pedagogical encounter

Maria-Carolina Cambre Immanence and Collage Heuristics

86 Visual Arts Research Summer 2013

that materializes as affect, as love. And it is in the acting, marching, or being inter-pellated by this image that one participates in the becoming part of this assemblage, and the consciousness of the so-called subject is transformed. Realizing their subjec-tion to power (that people are the words the social order speaks), viewers cross-fer-tilize the image of Che, and virtualities are actualized in the encounter, which pro-vides a point of reference from which to theorize resistance into focus. Dynamically flickering between visibility and invisibility, transparency and opacity, legibility and indecipherability, consciousness unfolds, and, as Sandoval tells us,

[t]his “open door” of consciousness is a place of crossing, of transition and metamorphosis. At this threshold, meanings are recovered and dispersed through another rhetoric that transfigures all others, and whose movement is its natures. . . . [T]he consciousness it requires reads the variables of meaning, apprehending and caressing their differences; it shuffles their (continual) rear-rangement, while its own parameters queerly shift according to necessity, ethical positioning, and power. (Sandoval, 2000, p. 131)

Using revolutionary love as a point of reference indicated by responsive encoun-ters with the Guerrillero Heroico, in this case, critical collage has the potential to enhance a navigational agility essential to the survival of the oppressed through the ability to perceive dominant-order sign systems in order to move among them. As becoming-viewers/artists, all those people participating in the virtual ever-ex-

Figure 6. M.-C. Cambre, 2010, Chenigma.

87

panding global collage of the Guerrillero Heroico provide ways to “generate access to politically revolutionary love, desire and resistance . . . undo fascism by ground-ing identity differently . . . [and develop] anti-colonial oppositional consciousness and praxis” (Sandoval, 2000, p. 165). To enable this process, becoming-educators/artists must be open to discarding institutionalized pedagogical maps, allowing the emergence of critical points of reference, and embarking on journeys to places of connection that, as Herman Melville’s (1851) Captain Ahab says, are “not down in any map; true places never are.” (A montage of the collage making process can be found here: http://youtu.be/VKul8io5Wbg. While the music provides for an experience foreshortened in time, this montage gives some texture and context to the images in this article.)

Acknowledgments

I am indebted to my anonymous reviewers for helping draw out many needed clarifications and greatly improving this text.

Notes

1. Smith & Protevi (2011).

2. See also Lyotard (1987). “Anamnesis constitutes a painful process of working through, a work of mourning for the conflicting emotions, loves and terrors, associated with these wounds. Perhaps the process is beginning” (10).

3. I use play in the following sense: play does not mean not to be rigorous, but to refuse being paralyzed by the constraints of scholarship . . . shake off rigor mortis hiding the embryonic idea, rework-reword and move things around, do things differently, follow uncharted paths . . . work on coherence . . . co-here, stick together.

4. This type of consciousness finds harmony with the principle of relationality in Indige-nous Research Methodologies (IRMs), or the interconnectedness of all things, and insists on the “transformative nature of research” (Weber-Pillwax, 1999, pp. 31–45).

5. An excellent example can be found in the 1967 Collage of Indignation put together by a group of over 150 New York-based artists to represent their anger at the Vietnam War (R. Smith, 1990).

6. This is a different use of the term from what is generally seen in the social sciences, where distanciation refers to the tendency for relations to grow apart in time and spa-ce, as noted by Anthony Giddens. Brecht’s notion is drawn from an Althusserian frame, where it describes an alienation effect.

7. “Repression of the nonlinear, that is, an alternative consciousness and perception of the world, is the result of the ascendancy of patriarchy and logocentrism that privileges male rationality; see Murphy (1995, p. 75). The non-form that must exist but cannot appear can be usefully conceptualized as the chora (receptacle/place). For Jacques Derrida, cho-ra is in-between the sense and intellect (Brockelman, 2001, p. 88). Similarly, Julia Kristeva explores the chora as a space of ambiguous relationality. The non-form that must exist but cannot appear can be usefully conceptualized as immanence. Essentially, as a space of possibility incarnated by gaps, and the missing elements of the fragments included in a collage, the virtual is never manifested. Brockelman (2001) states: “Chora is neither

Maria-Carolina Cambre Immanence and Collage Heuristics

88 Visual Arts Research Summer 2013

space in general (the universal form of space) nor a place (the specific sensuous ma-terial of myth). It is place, rather, as a relationship that can only be induced, can never directly appear—since every appearance follows either the path of logos or of mythos” (p. 88).

8. Collage can speak to children and youth through its accessibility and immediacy (Norris et al., 2007, p. 484).

9. Granted the famous Che Guevara photograph has been taken up in many ways, often as a watered-down and cliché designer rebellion. But the political import of the image is always present as a virtuality and exceeding the frame.

10. Schwitters’s undogmatic, non-élitist, and democratic collage work conjured up its own magic from the rejected and the discarded: small wonder that the Nazis found Schwit-ters’s art subversive and tried to eradicate it. (See Webster, 2011.)

References

Bourriaud, N. (2005). Postproduction: Culture as screenplay: How art reprograms the world. (J. Her-man, Trans.). New York, NY: Lukas & Sternberg.

Brockelman, T. P. (2001). The frame and the mirror : On collage and the postmodern. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press.

Deleuze, G. (1988). Spinoza: Practical philosophy. San Francisco: City Lights Books.

Deleuze, G. (1994). Difference and repetition. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Deleuze, G. (1995). Negotiations. (M. Joughin, Trans.). New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Deleuze, G. (2006). Two regimes of madness: Texts and interviews 1975–1995. (A. Hodges & M. Taormina, Trans.). New York, NY: Semiotext(e).

Deleuze, G., & Guattari, F. (1983). Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and schizophrenia. Minneapolis: Uni-versity of Minnesota Press.

Deleuze, G., & Guattari, F. (1987). A thousand plateaus: Capitalism and schizophrenia. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Deleuze, G., & Guattari, F. (1994). What is philosophy? (H. Tomlinson & G. Burchell, Trans.). New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Derrida, J. (1987). The truth in painting. (G. Bennington & I. McLeod, Trans.). Chicago, IL: Univer-sity of Chicago Press.

Dietrich, D. (1993). The collages of Kurt Schwitters. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Ells-worth, E. (1997). Teaching positions: Difference, pedagogy, and the power of address. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Ellsworth, E. (2005). The materiality of pedagogy. In Places of learning: media, architecture, peda-gogy (pp. 15–36). New York, NY: Routledge Falmer Press.

Garoian, C. R., & Gaudelius, Y. (2008). Spectacle pedagogy: Art, politics and visual culture. Albany: SUNY Press.

Gell, A. (1998). Art and agency: An anthropological theory. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Given, L. M. (2008). Sage encyclopedia of qualitative research methods (Vol. 1). Los Angeles: Sage.

Hammacher, A.M. (1981). Phantoms of the imagination: Fantasy in art and literature from Blake to Dali. (T. Langham & P. Peters, Trans.). New York, NY: Abrams.

Hazan, S. (2001). The virtual aura—Is there space for enchantment in a technological world? Retrieved from http://www.archimuse.com/mw2001/papers/hazan/hazan.html

89

Hooke, A. E. (2001). Alphonso Lingis’s we—A collage, not a collective. Diacritics, 31(4), 11–21. Retrieved from http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/diacritics/v031/31.4hooke.html

Kerne, A. (2001, September 21–22). CollageMachine: Interest-driven browsing through stream-ing collage. Proceedings of cast01//Living in Mixed Realities, Bonn, Germany. Retrieved from http://cultronix.eserver.org/collagemachine/andruidcultronix.html

Kuspit, D. (1983). Collage: The organizing principle of art in the age of relativity of art. In Donald Kuspit, The New Subjectivism: Art in the 1980s. New York, NY: Da Capo Press,

Lyotard, J.-F. (1987). Ticket to a new decor. (Brian Massumi and W. G. J. Niesluchowski, Trans.). Copyright 1. Retrieved from http://www.egs.edu/faculty/jean-francois-lyotard/articles/ticket-to-a-new-decor/.

Markus, P. (2004). Drawing on experience (Unpublished dissertation), McGill University, Montreal, QB, Canada.

Melville, H. (1851). Moby Dick. Retrieved from http://www.online-literature.com/melville/ mobydick/

Murphy, P. D. (1995). Literature, nature, and other ecofeminist critiques. Albany: State University of New York.

Norris, G., Mbokazi, T., Rorke, F., Goba, S., & Mitchell, C. (2007). Where do we start? Using col-lage to explore very young adolescents’ knowledge about HIV and AIDS in four senior primary classrooms in Kwazulu-Natal. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 11(4), 481–499.

O’Sullivan, S. (2010). From aesthetics to the abstract machine: Deleuze, Guattari, and contem-porary art practice. In S. Zepke & S. O’Sullivan (Eds.), Deleuze and contemporary art (pp. 189–207). Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Phillips, J. (2006). “Agencement/assemblage.” Theory Culture Society, 23(2–3), 108–109.

Sandoval, C. (2000). The methodology of the oppressed. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Smith, D. (2001). The doctrine of univocity: Deleuze’s ontology of immanence. In M. Bryden (Ed.), Deleuze and Religion. New York, NY: Routledge.

Smith, D., & Protevi, J. (2011). Gilles Deleuze. In Edward N. Zalta (Ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved from http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2011/entries/deleuze/

Smith, R. (1990, January 21). Gallery view: The Vietnam War ricochets into the galleries. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/1990/01/21/arts/gallery-view-the -vietnam-war-ricochets-into-the-galleries.html?pagewanted=all&src=pm

Spence, J. (1981). The sign as a site of class struggle: Reflections on works by John Heartfield. Block, 5, 2–13.

Tiessen, M. (2012, May 4–6). Deleuze, relational radicalism, and the persistent ubiquity of crea-tivity (disavowing anthropomorphic residues). Paper presented at Intensities and Lines of Flight: Deleuze, Guattari and the Arts, King’s University College at the University of Western Ontario, London, Canada.

Venn, C. (2006). A note on assemblage. Theory Culture Society, 23(2–3), 107–108.

Weber-Pillwax, C. (1999). Indigenous research methodology: Exploratory discussion of an elu-sive subject. Journal of Educational Thought, 33(1), 31–45.

Webster, G. (2011). Kurt Schwitters (1887–1948)—Biography. Retrieved from http://www.artchive .com/artchive/S/schwitters.html

Wilson, S. (2008). Research is ceremony: Indigenous research methods. Halifax, NS, Canada: Fern-wood.

Maria-Carolina Cambre Immanence and Collage Heuristics