Final Baseline Report West Africa Frontline Grassroots , Land ...

-

Upload

khangminh22 -

Category

Documents

-

view

0 -

download

0

Transcript of Final Baseline Report West Africa Frontline Grassroots , Land ...

1

Securing the Firewall and Connecting the

Unconnected: Frontline Defenders Across West

Africa

Final Baseline Report

West Africa

Frontline Grassroots , Land, Environmental and Human Rights Defender (HRD) Baseline report

focusing on Economic Social & Cultural Rights (ESCR) issues

Green Advocates International Liberia, West Africa

January 2021

Acronyms ESCR Economic, Social and Cultural Rights MRU Mano River Union NHRI National Human Rights Institutions OHCHR Office of the High Commission for Human Rights PILIWA Public Lawyering in West Africa UN United Nations

2

Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................ 5

Background ................................................................................................................ 6

Policy Details .......................................................................................................... 6

Cotonou Declaration ............................................................................................... 7

Background: West Africa Context ........................................................................... 8

Methodology and Limitations ...................................................................................... 9

Methods and Data collection ................................................................................... 9

Situational Analysis of all HRDs in West Africa ......................................................... 10

National HRD Organizations ................................................................................. 12

Working environment for National HRDs ............................................................... 12

Frontline Grassroots HRDs....................................................................................... 19

Communities face multiple human rights violations by Industry ............................. 21

Women HRD ......................................................................................................... 25

Gender dimension of ESC rights violations........................................................ 27

Governments, Multinational, and corrupt community leadership ............................... 27

Risks to National HRDs ........................................................................................ 27

Remedies at the community, national, regional, and international level .................... 29

Individual Level ..................................................................................................... 29

Office and Data Security ....................................................................................... 31

Data security ......................................................................................................... 31

Data Security Summary: .................................................................................... 32

Psycho-Social Support .......................................................................................... 32

Community Level Judicial Mechanisms................................................................. 32

Formal Judicial Mechanisms ............................................................................. 32

Informal Judicial Mechanisms............................................................................ 33

Using local traditional and cultural practices for disruption................................. 33

Community based assessment protocols .......................................................... 33

National level ........................................................................................................ 34

Formal ............................................................................................................... 34

Legal and Policy Framework ............................................................................. 34

Laws .................................................................................................................. 34

3

National Courts ..................................................................................................... 36

National Human Rights Institutions (NHRIs).......................................................... 36

Informal processes................................................................................................ 38

Coalitions Across the Region............................................................................. 38

Regional and Pan African ..................................................................................... 40

Formal ............................................................................................................... 40

Pan African Level .............................................................................................. 41

Informal ............................................................................................................. 43

International Level .................................................................................................... 47

Formal .................................................................................................................. 47

Informal ................................................................................................................. 50

Conclusions .............................................................................................................. 53

Annexes ................................................................................................................... 55

Annex 1: Legal and Policy Recommendations ...................................................... 55

Background ....................................................................................................... 55

Purpose of the Policy Recommendations .......................................................... 56

Current Legal Status of HRD’s Across West Africa ............................................ 56

Trending Legal, Policy and Situational Analysis of HRDs by country ................. 59

Overall recommendations and polices for all ......................................................... 81

Annex 2: Community Based Human Rights Protection Protocol .............................. 89

Introduction and Background ................................................................................ 89

Methodology ......................................................................................................... 89

Purpose/Goal and overview of this section ........................................................... 89

Case Studies ........................................................................................................ 90

Case Study: Developing protection checklists to keep communities in check .... 90

Case study: Developing a security risk assessment and protocol to keep individual and staff safe including contingency planning for worst case scenarios: ............ 90

Protections strategies for the collective ............................................................. 91

Case Study: Women Working Together in Coalition as a Form of Protection .... 92

Case study: Use peaceful methods first ............................................................ 92

Stories: Strategies for engaging with government agencies .................................. 93

Case study: Example use of policy analysis a weapon to engage and hold government to account ...................................................................................... 94

Case study: Using community-based assessment tool ...................................... 95

Case study: The importance of community unity ............................................... 96

Case study: Sharing experiences and networking. ............................................ 97

4

Case Study: Bringing cases to court at the national and regional level. ............. 97

Strengthening the legal framework to protect HRDs throughout the country. ..... 99

Checklist: Determining whether the NHRI is equipped for community protection ........................................................................................................................ 101

Annex 3: Strategic Plan for Next Steps ................................................................... 113

Introduction ......................................................................................................... 113

Methodology and its limitations ........................................................................... 113

Purpose, Goals and Objectives of the Strategic plan .......................................... 113

Main Findings ..................................................................................................... 114

Funding at the global level ............................................................................... 114

Private Funding ............................................................................................... 114

Private Regional funding options ..................................................................... 115

Funding from Participating in Coalitions. ......................................................... 115

Links with INGOs ............................................................................................. 116

5

Introduction

The West Africa Frontline Grassroots Environmental and Human Rights Defender (HRD) Baseline report focuses on Economic Social and Cultural Rights (ESCR) issues). It summarizes the status of HRD, which focus on ESC rights, specifically land and environmental rights on the frontline in communities in West Africa. This report draws on interviews and desk research completed in the first half of 2020. This document was planned to be presented at a conference in Liberia in June 2020, but, due to Covid 19, the conference will be held online and is scheduled for March 2021. The conference will bring together HRDs from West Africa and Equatorial Guinea with key donors and others to discuss the work and challenges faced by Frontline Grassroots HRDs in West Africa.1 Green Advocates International works closely with the Mano River Union Civil Society Natural Resources Rights and Governance Platform, who serve as the anchor and platform for Frontline Grassroots HRDs in West Africa. Alfred Brownell,2 the founder and lead campaigner at Green Advocates, serves as the strategic policy advisor and supervisor of the baseline assessment (described below) and the conference. Francis Colee, Head of Programs at Green Advocates International, is helping to coordinate this project. Peter Quaqua, the head of the Secretariat of the Mano River Union Civil Society Natural Resources Rights and Governance Platform, is overseeing the conference preparations and beyond. This baseline assessment summarizes the situation of HRDs in West Africa, focusing on frontline workers in communities across the region. It addresses:

✓ Who they are, and the types of violations they endure ✓ Who the perpetrators are, and how they operate ✓ The strategies used by National and Frontline Grassroots HRDs to keep

themselves safe, ✓ The mechanisms that are available to individuals at the local, community,

national, regional, and international levels for protection ✓ Where the gaps are

Once these steps are taken it is important to expand on existing approaches and to provide Frontline Grassroots HRDs with technical capacity, funding, tools, and strategies that are easy to use, effective, accessible, and sustainable. This baseline assessment highlights the work of HRDs, focusing on the climate crisis and environmental and social impacts related to the operations of multinational corporations, and how these collectively have escalated the already-precarious situation. It is important to briefly mention the impacts of climate change, including droughts, food insecurity, floods, and sea level changes - and the resulting impact on communities across West Africa, which has intensified conflicts between pastoralists and farmers; artisanal small-scale miners and large-scale commercial mining

1 The HRDs who are the focus of this report are divided into National and Frontline Grassroots HRDs that are described in detail in the next section. 2 Alfred Brownell is Liberian and currently based in the US. In addition to his role at Green Advocates International he is also an Associate Research Professor, North-eastern University School of law and currently a Visiting Faculty Scholar at Yale Law school

6

operators; artisanal fisherfolk and industrial commercial fisheries; and the protection and insecurity issues caused by these conflicts.

Background

Human Rights Defenders (HRDs) are on the frontlines of the struggle to ensure that the principles and rights laid out in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) and subsequent human rights conventions are upheld around the world. The United Nations Declaration on Human Rights Defenders, a protocol designed to protect HRDs worldwide, was created in 2000. Subsequently, many polices and protocols have been developed, as summarized in Table 1 below.3

Table 1 Summary: Existing International and regional policies aimed to protect HRDs

Date Polices aimed at protecting HRDs

2000 UN Declaration on Human Rights Defenders

2014 Special Procedures mandate that led to the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights), Working Group on Business and Human Rights and now the OEIGWG Treaty4.

2017 Human Rights Defenders and Civic Space: Business and Human Rights5

2017 The Cotonou Declaration on strengthening and expanding the protection of all Human Rights Defenders in Africa 6

2018 2018 Global assessment carried by the UN Special Rapporteur about Human Rights Defenders

2019 Landmark Resolution to protect environmental HRDs

2019 Advisory note to the African group in Geneva on the legally binding instrument to regulate in international human rights law, the activities of transnational corporations and other business enterprises7

2021 EU Commissioner for Justice commits to legislation on mandatory due diligence for companies8

Policy Details

The 2000 United Nations Declaration of Human Rights Defenders holds governments responsible for implementing and respecting provisions, particularly the duty to protect HRDs from harm because of their work. In 2011 a Commentary to the Declaration on HRDs mapped out the rights defined in the Declaration.9 In 2014 the Special Procedures mandate led to the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights and the Working Group on Business and Human Rights and, now, the Open-ended intergovernmental working group on transnational corporations and other business enterprises with respect to human rights. 10

3 https://www.ohchr.org/EN/Issues/SRHRDefenders/Pages/Declaration.aspx 4 OHCHR | WGTransCorp IGWG on TNCs and Human Rights 5 https://www.ohchr.org/EN/Issues/Business/Pages/HRDefendersCivicSpace.aspx 6 https://www.achpr.org/news/viewdetail?id=31 7 file:///C:/Users/Tmber/Downloads/Advisory%20note%20Africa%20Group%20UN%20Treaty.ENG%20(2).pdf 8https://www.business-humanrights.org/en/eu-commissioner-for-justice-commits-to-legislation-on-mandatory-due-diligence-for-companies 9 https://www.ohchr.org/EN/Issues/SRHRDefenders/Pages/Declaration.aspx 10 OHCHR | WGTransCorp IGWG on TNCs and Human Rights

7

The 2016 Special Rapporteur for situation of Human Rights Defenders report documented good practices and policies in the protection of HRDs and made concrete recommendations to states, business enterprises, NHRI, donors, civil society organizations and other stakeholders focused on creating a safe and enabling environment for HRDs. The report articulates seven key principles that should inform the development and implementation of any measures to support and protect HRDs.

Other guidance: the UN Human Rights Council (HRC) unanimously adopted a landmark resolution to protect environmental HRDs following reports of increased cases of human rights violations against HRDs globally.11 This new resolution calls on governments to create a safe and enabling environment for HRDs, and to ensure effective remedies for addressing human rights violations and combating impunity. It recognizes:

• The important, legitimate role of environmental HRDs in protecting the environment, and the high levels of risk they face in their work.

• The need to develop mechanisms to protect the intersecting violations suffered by WHRDs, indigenous peoples, and rural and marginalized communities.

• The responsibilities of corporations, and calls on them to respect human rights in accordance with the voluntary Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs).

Cotonou Declaration

The Cotonou Declaration on strengthening and expanding the protection of all HRD in Africa was adopted regionally in 2017. The Declaration highlights special groups of HRDs who are specifically at risk, such as WHRDs, human rights activists working in conflict and post conflict states, on issues related to land, health, HIV, sexual orientation and gender identity and expression, and sexual and reproductive health rights. Like the UN Declaration, it calls on civil society organizations, NHRIs, and governments across Africa, to ensure the promotion and protection of all human rights at local, national, and regional levels.12 Despite this global recognition of the problem and policies and conventions aimed to address the issues, there remain serious challenges to implementation, as attacks on HRDs in West Africa, especially Frontline Grassroots HRDs continue “under the radar.” There is a troubling regional trend toward shrinking civilian space, criminalization, militarization, stigmatization, and the cumbersome registration procedures that make it challenging for HRDs to operate independently. The HRDs are being killed, threatened, stigmatized, harassed and subject to increased government surveillance both online and physically.

11 The cases where largely from Latin America and the Philippines. 12 Noting with appreciation the work of the Special Rapporteur on Human Rights Defenders in Africa and that of the Study Group on Freedom of Association and Assembly in Africa, as well as the work of the UN Human Rights Mechanisms in protecting human rights defenders in Africa, in particular the contribution of the UN Special Rapporteur about human rights defenders and the UN Special Rapporteur on the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and of association.

8

Thus, the deteriorating situation in West Africa reflects a lack of adequate protection for HRDs in the current context. In many instances, HRD’s face arbitrary arrest and detention, frivolous criminal charges, false accusations, unfair trials, and conviction. In the 2018 report, the UN Special Rapporteur recommended that West African countries review, amend and repeal laws that restrict the right to freedom of opinion, expression, association, and assembly and take measures to ensure that HRDs can exercise these rights without interference.13

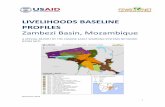

Background: West Africa Context

West Africa comprises 16 countries, including five anglophone, nine francophone and two Portuguese speaking countries.14 Equatorial Guinea is included in this study, although it is not part of West Africa nor a member of ECOWAS. Mauritania is also included, but is not a member of ECOWAS. Historical and current political, social, and economic factors in the region have impacted the status of frontline grassroots defenders of environmental, land, and human rights. The post-independence decades have been characterized by violent civil, political, ethnic, and religious conflicts, including military coups. Despite these challenges, there has also been progress in the peaceful resolution of conflicts. For example, Ghana, Nigeria, Togo, Burkina Faso, Mali, Sierra Leone, Liberia, Cote D’Ivoire, Guinea Bissau and Guinea have participated in elections and the relatively peaceful passing of power from a ruling party to an opposition political party. However, much remains to be done. Violent extremist organizations, such as Boko Haram and Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) also exist in Nigeria, Niger, Burkina Faso, and Mauritania. Throughout the region, any perceived threat to political leaders’ power or access to resources is a major flashpoint for conflict, with elections often igniting violence and strife. Climate change and environmental impacts are evident across the region, and conflict continues to be driven by disputes over natural resources, ethnic divisions, and economic and social disenfranchisement and exclusion. The West African sub-region is rich in natural resources, yet the people and countries in the region are among some of the poorest and least developed in the world. Human rights violations, corruption, and violence continue to characterize much of the region. For example, even though most West African governments invite direct foreign investment in to boost their economies and create jobs, it does not appear that most multinational enterprises are contributing to the positive development of the countries. Rather, the communities in which they are operating are becoming more disenfranchised and poorer while the multinationals - some within the government leadership - appear to be making profits. Various accounts have shown how foreign companies, with the backing of their host and home governments, violate local community rights with impunity. As a result, poor people suffer from a range of human rights violations including displacement, denial of their livelihoods and

13 https://www.business-humanrights.org/sites/default/files/documents/UNSR%20HRDs-%20World%20report%202018.pdf 14 Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, Côte d’Ivoire, the Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Liberia, Mali, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra Leone, and Togo are all members of Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS). Mauritania is considered part of West Africa but not a member of ECOWAS.

9

destruction of property. The situation across the region creates risk for the National HRDs and Frontline Grassroots HRDs who focus on protecting these rights.

Methodology and Limitations

A mixed methods approach was used, relying largely on interviews and desk review to feed into the draft report. During the online conference, feedback and a validation of the information will be done on the various components of the baseline, which will be incorporated into and feed into final report.

Methods and Data collection

Overall, over 35 key informant interviews (KII) were done. These included seven (7) WHRDs and 23 HRDs from all the 17 countries. There were also detailed interviews done with Frontline Grassroots Environmental, Land and Human Rights Defenders by focal persons from organizations who support the work of Frontline Defenders in the region. A total of Seventy-Eight (78) Frontline Defenders were interviewed and profiled. The data collected from the interview of the Frontline Defenders were then used to create a confidential profile of these defenders from Liberia, Sierra Leone, Guinea, La Cote D’ Ivoire, Ghana, Niger, Nigeria, Mali, Burkina Faso, Benin, Gambia, Togo, Senegal, Guinea Bissau, Cape Verde and Mauritania. Anonymized data from those profiled were also included in this report without attributions to the Frontline Grassroots HRDs. While the questionnaire used for the interviews is attached as Annex 2, a list of those interviewed is on file with the authors of this report to protect their security and privacy. An extensive Desk Review was done to compliment and corroborate the information gathered in the interviews. One key reference was a conference report from the Peoples Summit held in Makeni Sierra Leone in 2019, where HRDs from the region shared experiences. The forum brought together over fifty participants from MRU and ECOWAS countries, Central Africa, UK, and the USA. There were representatives from Sierra Leone, Liberia, Ghana, Nigeria, Mali, D.R. of the Congo, Ivory Coast, Guinea, and Niger. The forum was organized by Green Advocates International in Liberia, funded by the Fund for Global Human Rights (FGHR), and hosted by the Network Movement for Justice and Development (NMJD) and the Sierra Leone Network on the Right to Food (SiLNoRF). Limitations to the data collection and research As the research questions were quite broad, it was important to limit the scope to make the task feasible and manageable. Therefore, it is not an exhaustive study of every HRD who is at risk, or every law that violates the rights of HRDs, nor every remedy and organization that is operating in West Africa. Its goal is to highlight both National and Frontline Grassroots HRDs that are dealing with issues related to lack of access to land and livelihood, the consequences of resettlement once multinationals move in, and environmental rights. It highlights the most sensitive ESCR in each country, as identified through the interviews. Data Privacy and Protection

10

Consideration has been given to protecting the confidentiality and privacy of those who were interviewed and all information gathered. As a precaution, no specific names of individuals are used in the report. The names of those interviewed are provided in an annex that will not be made public. To protect the confidentiality of all parties, alleged perpetrators are not named individually, and companies are not identified by name. Names are only used in circumstances where the information is already in the public domain, such as in secondary sources. The organization of the report The West Africa Frontline Grassroots ESCR baseline assessment is divided into three parts. The first part provides an overview of the HRDs, distinguishing between National and Frontline Grassroots HRDs, including who they are, what they do, and the risks they face. It also provides a broader situational analysis of the main alleged perpetrators and the types of violations being perpetrated. The second part provides an overview of the remedies from the individual prevention level, to the community, national, regional, and international levels and includes an overview of the key players that support the protection of HRDs. The third part includes three annexes that draw from the baseline report to include:

• A set of policy recommendations are aimed at building upon existing policies that are relevant to the situation of HRDs. Policy recommendation are directed towards regional, international, and non-state actors who work and engage in West Africa. National recommendations by country are also included. It also highlights how international support can be sought to put pressure on West African entities to implement policy recommendations.

• The community protection protocol defines the different HRDs that the protection protocol aims to address, highlights the risks they face, and summarizes current remedies available at the various levels, from the community through the international level, and provides examples of remedies that have been used by HRDs interviewed.

• Funding strategy outlines the donors that are currently engaged and the range of activities that need funding, highlights the gaps, and suggests how to think about moving forward.

Situational Analysis of all HRDs in West Africa

National and Frontline Grassroots HRDs are on the frontline of the struggle to ensure that the principles and rights laid out in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) and subsequent human rights conventions are upheld around the world.15 HRDs play various roles, working as journalists, environmentalists, women and gender activists, indigenous peoples and land rights advocates, whistle-blowers, trade unionists, lawyers, teachers, housing campaigners or individuals acting alone. Some act individually or with others, to promote or protect human rights as part of their jobs or as volunteers. As a result of their activities, they are subject to reprisals

15 https://www.ohchr.org/EN/Issues/SRHRDefenders/Pages/Defender.aspx

11

and attacks of all kinds, including smears, surveillance, harassment, false charges, arbitrary detention, restrictions on freedom of association, physical attacks and even death.16 This report also refers to other, more specific definitions of HRDs. First, we make an important distinction between two types of HRDs at risk in West Africa that are the focus of this study. First, we refer to National HRDs,17 which often lead organizations and coalitions and are known within their countries as fighting on behalf of ESCR issues, especially those linked to land, natural resources, the environment, and indigenous communities. Second, there are Frontline Grassroots HRD’s working at the community level that are largely unknown outside of their communities, but are fighting for their rights to a clean and healthy environment, rights to their land and natural resources, and the ESCRs of those in their communities. Frontline Grassroots HRDs serve to protect communities against human rights abuses. Table 2 below summarizes who they are, what they do, how they do it, and the risks they face. Table 2: Two types of HRDs and the main differences between them

National HRD Grassroot Frontline HRDs

Who they are: Known to the international community, well known in civil society, participates at the regional and international level. Leaders of organizations and coalitions, lawyers, journalists. Professionally trained. Based in national or regional hubs in their country, well known by others in country.

Who they are: Does not identify himself/herself as an HRD. Works within their community, unknown outside of their community. Known within their community i.e., official community leader, or self-appointed director or chairman of CBO, staff of CBO, active community member, farmer, head of a natural resource user group, a youth leader, a women’s leader, head of a migrant community, a community radio talk show host, a local internet blogger, etc.

What they do: Work on behalf of organization or coalition at the community level, defending the rights of vulnerable groups. especially communities and community HRDs for the entire range of rights including land, environmental, cultural, political, and civil rights.

What they do: Work to protect individual and community rights to land, cultural rights, or environmental rights that are being violated by government or other third party.

How they do it: Writing reports, protesting at the national level, engaging with UN mechanisms, engaging with international partners, leading strategic litigation, exposing issues on social media or through engaging journalists, providing community legal aid, engaging with government or companies directly or in support of community groups.

How they do it: Engaging with company or government, educating community about company activities, organizing communities, taking direct action: sometimes illegal and violent, sometimes peaceful and patient.

Main risks: Unlawful arrest, arbitrary detention, being fined, reputational risk (e.g., accusation of being anti-development), national-level restrictions that inhibit inability to carry out work, shut-down of organization.

Main risks: Environmental degradation; loss of land, water, property rights, access to livelihood and cultural sites, health risks. Some people are at risk of being arrested, detained, assaulted, losing the respect of their families or communities, or losing their life.

16 Ibid. 17 Frontline Grassroots HRD and National HRD are not officially recognized titles they are and only referred to in this report.

12

National HRD Organizations

The National HRDs interviewed were all college educated and professionally trained lawyers, journalists, community mobilizers, advocates, or researchers. They are heads of organizations and belong to, or head, coalitions. Table 2 below highlights some key organizations and coalitions in West Africa that are run by the National HRD. These organizations and coalitions work on behalf of the communities related to protecting ESCR, especially related to land, the environment, business, and human rights. These HRDs are well-known in their own countries, and many are well-known to the international communities within their countries. Many also participate in regional and international meetings.

Table 3: National HRD organizations

Country Executive Director

Organization/Coalition

Liberia Alfred Brownell

Green Advocates International (GIA) works in Liberia and across the region to support grassroots communities

Cote d’Ivoire

Michel Youboue

Groupe de Recherche et de Plaidoyer sur les Industries Extractive (GRPIE) works throughout Cote d’ Ivoire and in four other countries in the region

Sierra Leone

Abu Brima Network Movement for Justice and Development (NMJD) leads coalitions within Sierra Leone, has been working in the country for three decades, has regional offices throughout Sierra Leone

Guinea Aboubacar Diallo

The Centre for Commerce and International Development (CECIDE) in Guinea works across the country, carries important research and supports communities

Nigeria Chima Williams

Environmental Rights Action (Friends of the Earth Nigeria) focuses on human rights and environmental law in defense of communities and people who have been impacted by multinational companies and other government actors.

Ghana Augustine Niber

The Center for Public Interest Law (CEPIL)18 was created after research in mining communities showed the need for greater representation from communities living in these areas facing large-scale violations against them. CEPIL responded to these communities by expanding to public interest law litigation.

In addition, these National HRDs work together in coalitions such as PILIWA and MRU, as discussed at length later in the report. Several of these HRDs are doing ground-breaking work in support of communities across the region. As highlighted above, all of these organizations are working in their own countries supporting communities to fight for ESCR rights.

Working environment for National HRDs

In sharing their experiences, National HRDs largely described a shrinking environment for human rights activism and respect for the rule of law. There were

13

some exceptions within West Africa. For example, as a result of the 2016 election in The Gambia, HRDs were put in danger by the criminalisation of HRDs, repressive laws and anti-development rhetoric. Table 4 highlights characteristics of the working environment that was experienced by National HRDs. Table 4: Characteristics of the working environment for National HRDs

Working Environment Characteristics Countries

Extra-judicial killings take place, and at least one HRD murdered

All countries

Human Rights violations faced by many HRDs in the region, including unlawful arrests, unlawful detention, incommunicado detention, judicial threats, false charges, being forced into exile or relocation, forcibly displaced, murdered

All countries except for Cape Verde

Under-reporting murders due to a lack of a clear definition of HRDs due to the nexus of non-state actors and mainly extremist organizations and criminal gangs

Mali, Burkina, Nigeria, Niger, Mauritania

Shrinking of civic spaces includes criminalization, militarization, stigmatization, and limits to the freedoms of press, expression, and association

Almost all countries highlighted except for Cape Verde and The Gambia

Non-state actors – mainly extremist organizations and criminal gangs - also present a major threat to HRDs

Mali, Burkina, Nigeria, Niger, Mauritania

HRDs are characterised as traitors and anti-development, anti-government, anti-investment, anti-country actors. Broader society does not understand the role of HRDs in society

All countries except Cape Verde and Guinea Bissau

A shrinking of civic space starts with laws and normative frameworks like criminal law, regulations against terrorism, a criminal provision contained in administrative or labour laws that restrict, impede, and are used in pursuing political goals against HRDs. In some West African countries, it is manifested through restrictions on freedom of association, freedom of expression, and freedom of the press. In Liberia, sedition laws are used to impede HRDs.

• In one case in Liberia a HRD activist in February 2016 was arrested and indicted for sedition and criminal libel against the then President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf as he had reportedly called for accountability for the killings of human rights activists in Liberia. Several months later in May the charges were dropped.19

19 Liberian activist freed as sedition charges dropped - CIVICUS - Tracking conditions for citizen action

14

• In Senegal there is a law that prohibits protests from taking place in the capital, which limits the ability of civil society to express themselves directly to government.

• In Cote d’Ivoire, a new criminal code criminalizes the act of offending the head of state, which threatens to further undermine the right to free expression.

• In Burkina Faso, the criminal code was amended to include overly broad offences that could be used to restrict access to information and further restrict HRDs.

• In Benin, an article in the penal code prevents peaceful demonstrations, making it easy accuse and charge a person with any crime. Also, in Benin a recent law related to the use of social media effectively curbs both freedom of

15

speech and expression.20 One HRD from Benin shared, “The punishment is a large fine and you can face imprisonment of six months to one year. The major concern is that these laws completely silence HRDs within Benin and only those living outside the country feel confident even posting on social media or to say anything.21

• Nigeria is one of the most legally repressive states in the region. For example, online freedom of expression is restricted by a 2015 cyber-crime law that is widely used to arrest and prosecute journalists and bloggers in an arbitrary manner.22

• Terrorism laws in Guinea and Burkina Faso have played a role in limiting civic space. Guinea’s law for prevention and repression of terrorism contains provisions that could be used to criminalize the legitimate exercise of the right to freedom of expression. In Burkina Faso the National Assembly voted for a new law in 2019 allowing that the state of emergency can be declared in a situation of ‘permanent crisis.’ These actions are considered justified by HRDs as a measure to fight ‘Islamic terrorism’ considering the threat. In December 2020, the UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights Defenders recognized this as a global issue, highlighting that many countries are using ‘anti-terrorism’ laws to silence HRDs. HRDs suspect that the law is used in bad faith to restrict their work or to justify the excessive use of force against enemies, HRDs or communities.23

Table 5 Example laws limiting rights in some of the countries across the region

20 According to Amnesty International in less than two years, at least 17 journalists, bloggers and political activists have been prosecuted under Law No. 2017-20 of 20 April 2018, which sets out repressive measures that restrict rights to freedom of speech and freedom of the press in Benin. The Benin authorities last year expelled the European Union Ambassador for alleged interference in internal affairs and further elaborated in https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2020/04/benin-le-retrait-aux-individus-du-droit-de-saisir-la-cour-africaine-est-un-recul-dangereux/ I 24 On June 20, 2019, Burkina Faso’s Parliament amended the country’s Penal Code to introduce a series of new offenses that aim to fight terrorism and organized crime, fight the spread of “fake news,” and suppress efforts to “demoralize” the Burkinabe armed forces. Many journalists and NGOs have denounced the newly created offenses, particularly those that restrict the activities of the media, as serious infringements on freedom. The new law, which was deemed to be consistent with the Burkinabe Constitution by the Constitutional Council (the high court tasked with evaluating the constitutionality of legislation), was signed by Burkina Faso’s President on July 31, 2019, and officially published on August 1. These amendments to the Penal Code have given rise to concerns that they would muzzle the Burkinabe press. Numerous professional media organizations have condemned the law for the severity of the penalties it imposes and the vagueness of the offenses it creates. The law will “grant to the state much greater control over information,” according to the director of the West African Bureau of Reporters Without Borders, and will “introduce extremely grave restrictions on the freedom to inform in a country that, until now, was considered exemplary.” Amnesty International has also expressed its opposition to the new Penal Code, writing that articles 312-14 and 312-15 “jeopardize the legitimate exercise of the right to freedom of information protected by the Constitution of Burkina Faso and the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights.” For more information see Burkina Faso: Parliament Amends Penal Code | Global Legal Monitor (loc.gov) 25 Guinea’s National Assembly passed a law proposed by the government on the use of arms by the gendarmerie on June 25,

2019. The law sets out several justifications for the use of force – including to defend positions gendarmes occupy – without

Country New laws limiting rights

Burkina Faso Amendments to the penal code in 2019 aimed at fighting terrorism and organized crime have been criticized for limiting free speech and press24

Guinea In 2019 the government passed a law on the use of arms by gendarmerie justifying the use of force, raising concern that it could be used against peaceful protesters25

16

In Mali, the HRDs describe how the instability in northern Mali severely affects their work and the capacity of HRDs. The HRDs claim that the climate of fear and insecurity is pervasive largely because of the presence of non-state armed groups. There is also a question whether extremist groups may exist as a response to governments’ lack of respect for the rule of law and human rights.26 The question was raised whether groups such as the Fulani or Tuareg may have turned to extremist measures to defend their land and livelihood. If so, there could there be a major undercount of the numbers of individuals impacted and killed defending themselves, their lands, and livelihood.27 A law in Mauritania from 1964 requires civil society organizations to register with the Ministry of the Interior, giving this office the power to accept or reject organizations. As a result of this outdated law, some organizations work illegally - preferring not to register with the Ministry of Interior. Another Mauritanian law requires a permit to hold a demonstration, on the pretext that demonstrations can create riots, which makes it exceedingly difficult for protests to take place at all. An HRD from Mauritania shared,

“So, if you do not have permission, the demonstration is perceived as illegal and you can be subjected to repression. In fact, the people here are very peaceful, it is the police who create problems. As there are always young

making clear that firearms can only be used when there is an imminent threat of death or serious injury. The law’s explanatory note also notes the need to protect gendarmes who resort to force from vengeful prosecutions, raising concern that it will be used to prevent judicial oversight of law enforcement. For more information see Guinea: New Law Could Shield Police from Prosecution | Human Rights Watch (hrw.org) 23 The Minister of Territorial Administration, the Minister of Security, and the Governor of the respective region are enabled to prohibit circulation of people and vehicles at times they decide on; public prosecution and police can search private houses at any time; publications and assemblies that are suspected of promoting ‘radicalization and violent extremism’ can be prohibited. 24 On June 20, 2019, Burkina Faso’s Parliament amended the country’s Penal Code to introduce a series of new offenses that aim to fight terrorism and organized crime, fight the spread of “fake news,” and suppress efforts to “demoralize” the Burkinabe armed forces. Many journalists and NGOs have denounced the newly created offenses, particularly those that restrict the activities of the media, as serious infringements on freedom. The new law, which was deemed to be consistent with the Burkinabe Constitution by the Constitutional Council (the high court tasked with evaluating the constitutionality of legislation), was signed by Burkina Faso’s President on July 31, 2019, and officially published on August 1. These amendments to the Penal Code have given rise to concerns that they would muzzle the Burkinabe press. Numerous professional media organizations have condemned the law for the severity of the penalties it imposes and the vagueness of the offenses it creates. The law will “grant to the state much greater control over information,” according to the director of the West African Bureau of Reporters Without Borders, and will “introduce extremely grave restrictions on the freedom to inform in a country that, until now, was considered exemplary.” Amnesty International has also expressed its opposition to the new Penal Code, writing that articles 312-14 and 312-15 “jeopardize the legitimate exercise of the right to freedom of information protected by the Constitution of Burkina Faso and the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights.” For more information see Burkina Faso: Parliament Amends Penal Code | Global Legal Monitor (loc.gov) 25 Guinea’s National Assembly passed a law proposed by the government on the use of arms by the gendarmerie on June 25,

2019. The law sets out several justifications for the use of force – including to defend positions gendarmes occupy – without making clear that firearms can only be used when there is an imminent threat of death or serious injury. The law’s explanatory note also notes the need to protect gendarmes who resort to force from vengeful prosecutions, raising concern that it will be used to prevent judicial oversight of law enforcement. For more information see Guinea: New Law Could Shield Police from Prosecution | Human Rights Watch (hrw.org) 26 This issue was brought up as a comment and would be ideal to bring to the discussion at the webinar with individuals from the Sahel. 27

Nigeria 2015 Cybercrime law used largely to limit journalists

Mauritania Law requiring permit to demonstrate, thus stifling freedom of expression

17

protesters, this creates clashes. So, there are arbitrary arrests, even if the detention does not last, it's really hard to protest”.

HRDs are being labelled anti-development, anti-country, and anti-investment. Across the region HRDs who focus on land rights or environmental issues or highlight corruption are often labelled “anti-development.” There are reports that when they raise concerns around contracts between governments and multinational companies in the mining, logging, and mineral sectors they have been labelled ‘mercenaries,’ ‘antidevelopment,’ or ‘blamed for speaking badly about their country internationally.’ For example, in Benin during a highly publicized anniversary celebration the president famously said, “We must sacrifice freedoms to go to development.” Another HRD from Benin working on business and human rights issues is labelled a “mercenary” and is prevented from travelling.

“We are called mercenaries as soon as we touch on important rights that do not promote the neoliberal agenda. We are isolated, we are sometimes prevented from going to international meetings.”

In Liberia, the HRDs who are most at risk are those who criticize private sector activities, as the government seeks to attract foreign direct investment. Such HRDs are considered anti-development, anti-country, and anti-investment. For example, in the previous administration’s annual message to the Liberian legislature in January 2014, the Liberian President stated that NGOs are undermining the sovereignty of Liberia. This seems to have improved slightly with the current administration, but the government’s desire to attract foreign direct investment remains strong. Anti-development rhetoric, especially coming from the top levels in government, contributes to an increasingly dangerous working environment that has compromised the safety and security of HRDs. In Liberia, journalists who criticise government officials or who express their political opinions are frequently harassed, detained, charged spurious fines, called terrorists, and their work is restricted by the government. In Mauritania, the law against racial discrimination is a double-edged sword.

“If someone claims discrimination, they could be arrested for speaking out against national unity limiting their ability to claim being discriminated against out of fear of being arrested for another crime.” He added, “It makes it very difficult to realize this right for fear of not showing loyalty to the country. These rights are in contradiction to one another”

The “anti-development” rhetoric puts HRDs under threat not only as a justification of the government to act against them, but also from the larger population who may not have a full understanding of the role of an HRD in society. It may put an HRD’s family at risk or turn family members against HRDs. The situation in the countries in the Sahel28

28 https://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=22370&LangID=E https://www.un.org/africarenewal/magazine/august-november-2018/strengthening-bonds-sahel

18

The Sahel part of West Africa includes northern Senegal, southern Mauritania, central Mali, northern Burkina Faso, Niger, and the extreme north of Nigeria. These countries face issues related to non-state groups. Even though thousands of people are being murdered annually and millions are displaced, most of whom could well qualify as Frontline Grassroots Environmental, Land and Human Rights Defenders, increasingly, the findings point to the fact that the Sahel’s underlying conflicts, the mass killings and the human rights and humanitarian crisis may not necessarily be limited to only religion and a violent ideology. Largely it is becoming clearer that youth gravitate toward armed movements because they lack jobs or other means of making a living, others join because of ethnic, social, and political conflicts. The Climate crisis has increased stress levels on existing scarce resources- dwindling water tables, erratic temperatures, droughts, increased in populations-driving needs for more farm lands and grazing corridors. In the north of Mali, Tuareg groups have fought for regional autonomy. For instance, in 2012 some Islamist movements took advantage of the conflict in Mali to occupy areas in the north, but they were pushed back the following year by a French African intervention force. Today the Malian government is seeking to accommodate Tuareg concerns, while simultaneously combating Islamist insurgents. Central Mali, meanwhile, has erupted into serious ethnic fighting, often originating in land conflicts between Fulani livestock herders and farmers of other ethnic groups. Seeking to restore peace, Fulani and Dogon youth associations are now taking steps to promote intercommunity dialogue. In the countries in the Sahel which include several from West Africa, several National Human Rights Defenders interviewed as well as Front line Defenders profiled expressed troubling concerns that the lack of respect for human rights and the environment, as well as ignoring the brutal impacts of the climate crisis, is a fundamental cornerstone undermining the fight against terrorism and resolving the herder- farmers conflicts in the region. This, unfortunately, is the opinion of the Special Representative of the United Nation Secretary General to United Nations Office for West Africa and the Sahel (UNOWAS).29 Human rights violations against HRDs Unlawful arrests, detention, and intimidation were the most common tactics used by government to punish HRDs at the national level (see Table 3 above). In Nigeria one HRD shared that “Unlawful arrest is a common thing. Often those arrested are not charged to court. It is a tactic of intimidation.” During or shortly before elections or referendums, criticism around corruption or a threat of losing power - especially

29 See Report from the Special Representative of the United Nation Secretary General to United Nations Office for West Africa and the Sahel (UNOWAS)

. https://www.un.org/press/en/2020/sc14245.doc.htm and https://undocs.org/s/2020/585 . “Describing the security conditions as “extremely volatile”. In Burkina Faso alone, as

of June, 921,000 people have been forced to flee, representing a 92 per cent rise over 2019 figures. In Mali, nearly 240,000 people are internally displaced — 54 per cent of them women — while in

Niger, 489,000 people were forced to flee, including Nigerian and Malian refugees. In Nigeria, 7.7 million people will need emergency assistance in 2020. He said that as national and multinational

forces intensify their operations to counter the violence, communities have organized volunteer groups and self-defenses militias. Rights groups have raised concerns over reports of alleged abuses by

these militias, as well as by security and defense forces.” Systematic attacks by violent extremists on civilians; intercommunal and electoral violence; the excessive and

disproportionate use of force by security forces; and restrictions on the freedoms of assembly and of the press, in a climate of impunity, affected respect for human rights and the rule of law in West Africa and the Sahel. Notwithstanding increased pressure from defense and security forces, violent extremists continued to carry out fatal attacks on civilians. On 10 February, 30 persons, including a pregnant woman and a baby, were killed when Boko Haram set ablaze 18 vehicles and their occupants in Auno, about 20 km from Maiduguri, Borno state. The United Nations continued to receive reports of human rights violations when counter-terrorism operations are conducted. They included the alleged burning down of houses in Borno state by Nigerian security forces on 3 and 4 January, the alleged killing of civilians by Malian defense forces between January and April, the alleged killing of civilians by Nigerien security forces between 27 March and 2 April and the alleged killing of 31 men by the security forces of Burkina Faso on 9 April in the town of Djibo, 200 km north of Ouagadougou

19

power over resources - can result in arrests and prolonged detention. People under arrest are often held incommunicado without access to a lawyer or family members, and charges are either unclear or non-existent. In some instances, governments have taken deadly action against the population during these periods. In Guinea between January 2015 and October 2019, at least 70 protesters and bystanders have been killed in actions linked to rising political tensions related to the threat to presidential power.30

HRDs in Mali have been arbitrarily detained and threatened for working on cases of government business and corruption within government ranks. HRDs who document and report on issues of human rights abuses face threats, intimidation, and physical attacks. HRDs who have accused government forces of human rights violations are particularly at risk. Journalists find it hard to access information about the human rights situation and are dissuaded from covering difficult topics through threats and harassment. In Equatorial Guinea, under the same president for almost 40 years, HRDs regularly face interventions in their communications. HRDs that are considered “too active” face severe restrictions on their work, and the constant threat that their activities will be suspended. HRDs face social and economic exclusion, including dismissal from work, ill-treatment or torture, suspension of the NGO’s activities or the NGO itself, arbitrary detention, or political trial for conspiring against the power. The government has absolute impunity, and there is no protection for NGO’s. In the Gambia, even though the situation has improved since a new president was elected in 2016, an increasing number of people who challenge government actions are being arrested and detained without charges.31 Several of the HRDs interviewed have faced threat of arrest or detention, and at least five of those interviewed have had to leave their country, in some cases for indefinite periods. This is further elaborated on in the next section.

Frontline Grassroots HRDs

The Frontline Grassroots Defenders, described in more detail in the Table 1 above, are HRDs that are often considered first responders. They work in their community, may not refer to themselves as HRDs, and they focus on the environment, land rights, indigenous rights, and business and human rights. As highlighted in the table below, these include Environmental Rights HRDs, Land Rights HRDs, Indigenous People HRDs, and Business and Human Rights HRDs. Additionally, identifying them in this way subjects them to more types of judicial and non-judicial recourse that will be covered further in the report. Table 6 Types and Definition of HRDs relevant to this study

30https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2019/11/guinea-human-rights-red-flags-ahead-of-presidential-election/ 31 In January 2020, Omar Touray a member of the former ruling party was arrested and detained for five days without being presented before a judge. Other cases of arrests and detentions include the case of Dr Ismaila Ceesay who was arrested in January 2018 after he gave an interview to a newspaper where he reportedly criticized the president. He was later released and charges against him dropped. In June 2017, youth activist and journalist Baboucarr Sey were subjected to arbitrary arrest and detention for leading a community initiative to protest the acquisition of a football field by a private company.

20

HRD Type Definition

Environmental HRDs

Individuals and groups who, in their personal capacity and in a peaceful manner, strive to protect and promote human rights related to environment, including water, air, land, flora, and fauna. They may face threats from both governmental and non-governmental bodies.

Land Rights HRDs

Many are indigenous rights Defenders who face threats from governmental, non-governmental, and corporate bodies, including defamation, physical attacks, judicial harassment, and killings.

Women Human rights Defenders

WHRD are subject to the same types of risks as any HRD, but as women, they are also targeted for or exposed to gender-specific threats and gender-specific violence. The reasons behind the targeting of WHRDs are multi-faceted and complex, and depend on the specific context in which the individual WHRD is working.

Indigenous People HRDs

Indigenous people face violence and brutality, continuing assimilation policies, marginalization, dispossession of land, forced removal or relocation, denial of land rights, impacts of large-scale development, abuses by military forces and armed conflict, and a host of other abuses. Indigenous people defending their rights and their lands, territories and communities are most at risk.32 The Tuareg and Fulani communities, sometimes called “terrorists” for defending their land, could also fit into the category of indigenous people. 33

Business and Human Rights HRDS

The growing reach and impact of business enterprises have given rise to a debate about the roles and responsibilities of such actors regarding human rights, and have led to the international community becoming involved.

Frontline Grassroots HRD research has found that environmental HRDs are three times as likely to suffer attacks than other HRDS. Research shows that 77% of HRDs who were killed in 2018 worked on land, indigenous peoples, or environmental rights globally.34 Although there are few clear statistics with regard to the threats that West Africa Frontline Grassroots HRDs, anecdotal evidence suggests that they often face a range of rights violations including lack of access to land, livelihood, and environmental concerns. In the defence of these rights, they are also at risk of their political and civil rights being violated. Table 7 below highlights the threats faced by Frontline Grassroots HRDs. Table 7: Threats faced by Frontline Grassroots HRD’s

32 LGBTQ rights were highlighted across the board as the most serious human rights issue however they are not dealt with at all in this report. 33 : A 2018 report by the Special Rapporteur for indigenous people’s rights highlights the risk of indigenous people’s rights and the risks that they face. Although West Africa is not explicitly mentioned the range of risks faced by indigenous people globally include the violation of a whole range of human rights from murder, environmental rights to forced evictions. More information can be found here: Microsoft Word - A HRC 39 17_AEV.docx (ohchr.org) 34 See Frontline Defenders for more information: Publications | Front Line Defenders

21

Threats Countries affected

Political and civil such as arrest, detention, harassment, frivolous criminal charges, media attack, stigmatization, and murder

All countries except Cape Verde

Economic, social, and cultural rights such as loss of land, property, and environmental rights

All countries except for Cape Verde and Burkina Faso

A combination of rights including economic, social, and cultural rights such as land or environmental rights. Their political and civil rights have come under attack including being arrested and held without charge, prolonged detention, job loss, and being murdered.

Across the region but highlighted especially in Liberia, Sierra Leone, Guinea, Ghana, Niger, Nigeria, and Ivory Coast.

Communities face multiple human rights violations by Industry

In resource-rich communities, mining, logging, rubber companies enter and take over land through deals with the national or local government or local community leader. Across the board, HRDs explained that, throughout West Africa, companies come into communities with no consultation with community members. These companies do not provide community members with full information about concessions or contracts, and community members are rarely, if ever, consulted. When companies are confronted, they often make promises to build schools, roads, clinics and provide jobs. Even if there are existing laws and policies related to mining, land, and the environment, they are not community-friendly. Communities are not part of the deals that governments make with companies: often deals are struck, and land is taken away without any discussion or consent. When promises are not kept, communities do not have any clear recourse to get their land back or tp ensure development projects are carried out. These issues were highlighted across the region with multiple examples from Liberia, Sierra Leone, Guinea, Ghana, Niger, Nigeria, and Ivory Coast. Relocations or resettlements of communities are often done improperly, and can result in numerous violations of communities’ rights. In Guinea one National HRD shared the following:

“We work on displacement—and with displacement there are so many other rights that are violated. People are losing their land which means they are losing their livelihood. Losing their means of living—they do not have clean water; they don’t have schools. There are so many human rights violations that result from displacement of the communities. What is worse is that where the communities are resettled to are not adequate there are no proper land, jobs, or access to medical care.”

The Guinean HRD stated that his job is not to stop the displacement, but to make sure that communities’ rights are being adequately addressed where they are relocated. He emphasized, “We are not against the displacement - just how it is done”.

22

HRDs from Sierra Leone, Nigeria, Senegal, Guinea, and Liberia highlighted that laws and policies around mining, land, and the environment are often unclear, unknown to the community, or pro-business. In Sierra Leone, the mining law is particularly problematic for communities. Even if laws do exist, communities are often unaware. An HRD from Senegal highlighted that.

“Communities don’t know their rights” Communities are not part of the deals that governments have with companies. Once deals are made, land is taken away without any discussion or consent. Often promises are not kept, but communities do not have any clear recourse to get their land back or ensure development projects are carried out.”

One HRD from Sierra Leone also shared the contradiction about government preaching development when, in fact, it does nothing to help communities. The Sierra Leonean HRD said:

“There are so many issues related to mining as it is supposed to be contributing to development but in the end, it does the opposite. Companies may make promises to build schools, roads, clinics and provide jobs. However rarely do they follow through leaving communities in an impossible position.”

Testimonies from Liberia, Sierra Leone, Guinea, Ghana, Niger, Nigeria Mauritania, and Ivory Coast highlighted these types of challenges. Efforts by communities to get information about contracts, or in some instances, to fight back, have resulted in further violations, and even death in some cases. Peaceful efforts by community leaders to seek out information from the government or company representatives are often ignored. For example, when a mining company came to a town in southeast Liberia, the Town Chief, responsible for administering land in communities, only learned about the appropriation of the land in a meeting hosted by the Liberian County Superintendent. When the Town Chief tried to get details of the concession agreement, he was threatened with dismissal by the local government, and later his brother and three other men in his community were arrested without cause and detained overnight in jail, but were never charged. The lack of recourse forces communities to either accept conditions and watch their land and livelihood slip away, or take some sort of action. Frontline Grassroots Defenders in Liberia and Guinea used different methods to address the situation. In some cases, the strategies bought them more time to plan, and in others there was intense backlash from the government or multinational. For example, in Liberia, the Frontline Grassroots HRD has tried to bring attention to the actions of the company or local government authority, including putting up a roadblock to prevent staff from entering or exiting the premises of the palm oil company where they work. This community action had a promising short-term benefit

23

in bringing the palm oil company to the table to negotiate the provision of jobs for at least one member of each family in the communities that were impacted. It was a huge win for the affected communities to gain employment. But the win was short-lived, as the action led to divisions in the community, and the Frontline Grassroots HRD was alienated from the community. Eventually the community realized that the division did not make sense and welcomed him back and chose unity within the community moving forward.

Stories shared by those interviewed in Liberia demonstrate that, whether the companies are extracting oil and gas,

minerals, rubber, timber, or palm oil, the impact on the Frontline Grassroots HRDs is surprisingly similar. There appears to be a pattern of land and livelihood being taken away, environment polluted and cultural sites desecrated, with a total lack of consultation with the community. Often when Frontline Grassroots HRDs try to act, they have faced further hardship and violation including loss of jobs, arrests, detention, and in some instances have been abandoned by family and community members - essentially losing everything. In Liberia, beginning in May 2015 following a protest of a palm oil company in a community in southwest Liberia, the Liberian police charged 23 people with a wide range of offences including economic sabotage, armed robbery, criminal attempt to commit murder, aggravated assault, terroristic threats, criminal mischief, criminal conspiracy, theft, burglary, kidnapping, felonious restraint, and disorderly conduct. These charges did not match the actions of a community peacefully protesting the actions of the oil company. This level of intimidation and threat can have a chilling effect on individuals and the community. The Frontline Grassroots HRD in Mali reported violations of rights to clean water, and environmental contamination that led to health problems, including an increase in lung diseases and miscarriages. This was the result of Mali’s two main gold operations being too close to communities. While they had set up a community development fund, apparently that fund was being used by the local government to pay police salaries, rather than community development.35 In Guinea, the main cause of violations against individual HDR’s is the lack of consultation between multinationals and the government, regarding relocation and resettlement of communities. In 2016 Kintinian, a community in Guinea, referred to as Area One, organized a peaceful protest in response to their relocation. In response, the Guinean army, who were financially and logistically supported by the multinational, responded by violating the rights of protesters.36 Thus, the local government and multi-national company turned on the community.37 A Frontline

35 Mano River Union Civil Society Natural Resources Rights and Governance Platform First Peoples’ Forum on Corporate Accountability: Final Report. 36 Guinea: Grassroots Frontline Human Rights Defender’s Profiles 37 Guinea: Grassroots Frontline Human Rights Defender’s Profiles

Frontline Grassroots HRDs often face a situation of multiple violations as not only are their land or environmental rights being violated, but often when they take action to fight for these rights their political and civil rights are also violated.

24

Grassroots WHRD, also from Kintinian, lamented that since the arrival of the multinational, the government had sent in an elite security force that had wreaked havoc on their community. She said,

“Before the white people company came, we had our farms, land, water, and fishes in our creeks. Now the land is empty. They destroyed the forest, no trees, they spoiled the creek, no water and fish and the land are polluted, we cannot farm so we do not have (sic) job and the white people say they will not give us (sic) job. We are finished.”38

In 2017 in another Guinea community, Sangaredi, a multinational mining company had taken over the land without proper consultation with the community. A riot broke out, resulting in mass arrest and detention by the police and the army.39 In 2019 following the eviction and relocation of communities in the suburbs of Kaporo rail, a complaint was filed with the Ministry of Town and Regional Planning Code, which led to a temporary stop in evicting the community. As a direct result, three Frontline Grassroots HRDs were arrested and detained. Some instances have turned deadly, with Frontline Grassroots HRDs either targeted or caught in the crossfire. In May 2019, two well-known HRDs of the Democratic Youth Organisation of Burkina Faso were killed in an apparent assassination in the province of Yagha in the northeast, bordering Niger. According to Amnesty International, Fahadou Cissé and Hama Balima were on route to a meeting with the high commissioner of the province, Adama Conseiga, in the provincial capital Sebba but never reached their destination. They were found dead, riddled with bullets, about five kilometres away from the town. A third body of an unidentified person (possibly an uninvolved witness) was lying a few hundred metres next to them. The place had obviously been ‘cleaned up,’ as not a single bullet casing was left at the scene.40 Numerous Frontline Grassroots HRDs shared their efforts to raise issues in a peaceful way. These efforts largely went unheeded by government or the multinationals. For example, in response to a multinational company arriving in a village in Cote d’Ivoire, disrupting village life and livelihood and forcing villagers to relocate, two Frontline Grassroots HRDs carried out awareness-raising and sensitization meetings to encourage the government to act. Despite the peaceful efforts of the Frontline Grassroots HRDs, the government and the multinational continued to supress, harass, intimidate, and arrest them. 41 Frontline Grassroots HRDs have also been killed across the region in protests related to issues around land and community rights. In Burkina Faso and in Yagha village, residents and protesting miners were reportedly shot, leaving five people dead in

38 Mano River Union Civil Society Natural Resources Rights and Governance Platform First Peoples’ Forum on Corporate Accountability: Final Report. 39 Mano River Union Civil Society Natural Resources Rights and Governance Platform First Peoples’ Forum on Corporate Accountability: Final Report. 40 Amnesty International, BRAVE Human Rights Defender for more information: Deadly but preventable attacks killings and enforced

disappearances of those who defend human rights (amnesty.org) 41 Mano River Union Civil Society Natural Resources Rights and Governance Platform First Peoples’ Forum on Corporate

Accountability: Final Report.

25

2014.42 In the Gambia in June 2018, three peaceful protestors were killed, and many others injured when armed policemen opened fire in the village of Faraba, 40 km outside of Banjul. Community members had been protesting because they thought a contract had been awarded to a company to conduct sand mining operations without consulting the local village council and stakeholders in the project, but the information was not received in time.43 In Bumbuna Sierra Leone in 2007 one person was killed by the police reportedly on the instruction of the mining company. During that same period 144 members of the community were reportedly falsely imprisoned in Makeni. One Frontline Grassroots HRD who wrote about it on social media was banished from the community by the paramount chief.44 In January 2019, two civilians were killed in a raid of local communities by military personnel who were protecting the palm oil plantations for a multinational company.45 One Frontline Grassroots Woman HRD who was also present when the two people were killed highlighted that the individuals were shot by military personnel, and 18 members of a landowners/user’s association were arrested, imprisoned, and had to go to trial. 46

Women HRD47

The Special Rapporteur of the situation of Human Rights Defenders defines WHRD as female HRDs, and any other HRDs who work in the defense of women’s rights or on gender issues. In the last few years, like with environmental and land rights, and indigenous HRDs, there has been increasing recognition of the need for greater protection of WHRDs.48 There is increasing recognition of the risks and vulnerabilities faced by WHRDs working on environmental issues, the rights of minorities, including indigenous and Dalit people, LGBTI rights, and sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHRs). Specific challenges include physical assaults, denial of medical treatment, degrading searches, threats to their families and communities, public defamation and attacks against their “honor,” arbitrary detention, sexual and gender-based violence, and killings. WHRDs are also at risk of being rejected by their communities and of being revictimized if they report acts of violence.49

42 Amnesty International, BRAVE Human Rights Defender for more information: Deadly but preventable attacks killings and enforced disappearances of those who defend human rights (amnesty.org) 43 In 2018 in the town of Faraba Banta, 50km south of Banjul, a contract was awarded to the Julakey Company to conduct sand mining operations in the area. Accusations were levelled that the contract had been awarded without consulting the local village council and stakeholders in the project. The week prior to the shooting, the National Assembly's Committee on the Environment had ordered the Julakey Company to cease operations pending the outcome of an investigation into their operations. However, due to complications in communications, by the day of the incident the company had yet to receive an official letter from the committee asking them to do so.[2]A commission of inquiry that was set up to investigate the deadly incident recommended that suspected perpetrators should be brought to justice, but they were pardoned by the President. https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2020/01/gambia-mass-arrests-risk-fuelling-tensions/, 44 Mano River Union Civil Society Natural Resources Rights and Governance Platform First Peoples’ Forum on Corporate

Accountability: Final Report. 45Further 15 people were arrested, including a member of parliament, and more than 2,500 people were forcibly displaced.https://www.escr-net.org/news/2019/sierra-leone-protect-land-rights-defenders 46 Mano River Union Civil Society Natural Resources Rights and Governance Platform First Peoples’ Forum on Corporate