Child Burials during the Middle Bronze Age of the South Urals (Sintashta Culture)

Elaborate burials in the Upper Paleolithic

Transcript of Elaborate burials in the Upper Paleolithic

University of Leicester School of Archaeology and Ancient

History

BA (Level 2) in Archaeology by Distance Learning

“Being Human – Evolution and Prehistory”

Module AR2555

Essay Question (Second Assessment)

“What is the significance of the elaborate human burials which

appear in the European Upper Palaeolithic? To what extent are

they a departure from previous periods, and what insights do

they offer into Upper Palaeolithic society?”

William Nichols

Student Number: 099026897

Number of Words: 3167

Submission Date: 8 January 2014

1

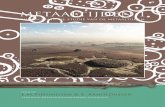

Head-to-head burial from the Upper Palaeolithic period at the

Sunghir site in Russia, 26 kya

(www.geneologyreligion.net/tag/funerals)

“Being Human – Evolution and Prehistory”

Module AR2555

Essay Question (Second Assessment)

“What is the significance of the elaborate human burials which

appear in the European Upper Palaeolithic? To what extent are

they a departure from previous periods, and what insights do

they offer into Upper Palaeolithic society?”

Introduction

This essay uses case studies to suggest that the appearance of

elaborate human burials in the Upper Palaeolithic (40-10 kya)

may be indicative of significant changes taking place in the

cultural patterns of societies across Europe during this time.

Topics presented include what the significance of these

burials are in defining the evolution of cultural behaviours

and the importance attributed to the concepts of the

afterlife, spirituality and how the dead were venerated. The

Upper Palaeolithic is compared to earlier periods exhibiting

2

the differences between these time periods showing not only

that distinction existed but that they appear in definable

progressions. Insights gained into Upper Palaeolithic

societies from these investigations are discussed and their

latest archaeological interpretations proposed. An

appreciation of what occurred during this era is helpful in

providing a greater understanding of the changing nature of

humankind as it moved toward modern human development.

Significance of elaborate human burials in the European Upper

Palaeolithic

The Upper Palaeolithic (ca 40 – 10 kya) witnessed the

appearance of rich human burials across much of Europe.

Amongst other artefacts, grave goods generally consist of

beads made from animal teeth, mobilary art objects, weaponry,

and the use of red ochre. The appearance of these elaborate

mortuary practices likely signal important changes in cultural

development (Dobrovolskaya et al. 2012: 96). An example of these

complex practices is found in the Sunghir site in Russia. This

site contains well preserved remains of three individuals, two

of which are buried head-to-head (as shown on the cover page

of this essay) and contain >13,000 mammoth ivory beads, fox

canine teeth and ivory spears, all covered with red ochre.

Skeletal remains of one of the inhumations show evidence of a

possible violent death while the two others exhibit

pathologies of congenital deformities. These burials are

significant in that they appear to speak of special treatment

3

of certain individuals in what may have been a hierarchical,

rather than egalitarian society, as previously supposed for

Upper Palaeolithic societies (Dobrovolskaya et al. 2012: 97,101).

Radiocarbon techniques using single amino acid on

extracted collagen are producing accurate dating results and a

better understanding of the complexity of burial behaviour in

the Upper Palaeolithic. The Sunghir site produced decorative

grave goods of intentional burials attesting to the

technological sophistication of the inhabitants of this site.

By using these improved dating techniques, a correlation was

developed proving that the Sunghir site (dated to 28-30 kya)

is closely related to the wider European cultures of other

humans of the same period. The rich burial contents of both

Eastern and Western Europe have certain similarities in ritual

and custom (Marom et al 2012: 6878-6880). Human burials, in which

red ochre and ornaments were used as decorations, indicate

that honouring the dead was commonplace and probably that

rituals were conducted as a commemoration or remembrance of

the dead. These types of burials appear first in the Upper

Palaeolithic from at least 29, 000 BP. Two recently found

infant burials in eastern Austria having the same treatment

may indicate that even newborns were considered to be full

members of the community and were treated in death much the

same as the adults (Einwögerer et al. 2006: 285).

The grave of one adult male at Sunghir who was given an

elaborate burial (shown below) presents an ancient mystery.

The skeletal remains suggest that the cause of death was due

to the penetration of a sharp blade or object through the 4

first thoracic vertebra severing the carotid artery. This may

indicate a hunting accident or perhaps a violent confrontation

as the most likely cause of death; however, ritual killing or

even suicide cannot be ruled out. Any of these hypotheses are

possible but some less probable than others, thus the problem

of equifinality (Lewin and Foley 2004: 486-487) challenges the

archaeologist’s deductive imagination. Whatever the cause of

death, this burial was an individual of high standing in the

community as evidence by the abundance of thousands of ivory

beads which must have involved a great expenditure of labour

by tribal members. This could be considered as an early form

of a division of labour or stratification and consequently

veneration for a particular member of the group (Trinkaus and

Buzhilova 2012: 655-666).

Sunghir 1 grave in situ with head and upper thorax

decorated with ivory beads 5

(www.donsmaps.com/sungaes)

The Upper Palaeolithic burial area at Predmostí (ca 27-24

mya) now in the Czech Republic, is located at one of the most

important valley passages in Europe and exhibits a large array

of mammoth and human fossils many of which have undergone

recent re-analysis and new interpretations for this site. The

significance of this excavation lies in speculation that

burials in the Upper Palaeolithic may be explained as a

declaration of rights of ownership of a territory and the

deposition of the remains as ancient claims to that property.

These burials were positioned at strategically important

points along the valley, perhaps in a symbolic purpose of

guarding or protecting the locale. At this site, mammoth

scapulae were used to cover the dead (Svoboda 2008:15, 31-32).

This practice has been observed in other European burial

sites. Mammoth scapulae placed over the heads or bodies of the

deceased are thought to have symbolised an attempt at

protecting and preserving the dead thereby transforming the

body into a cultural object (Gamble 1999: 414).

Elaborate funerary practices recorded in some Upper

Palaeolithic burials may be a reflection of spiritual belief,

and offering some insight into how ancient humans conceived of

the afterlife. For example, a high frequency of multiple

burials, many of which include severely deformed persons and

burial composition by age and sex suggests differential

practices based on status and standing of individuals within

the tribe (Formicola 2007: 446,451). Such respect for deformed6

persons is also shown at the Romito Cave in Italy from circa

11,150 BP in which the skeleton of an adolescent afflicted

with dwarfism rests in the arms of an adult female. The

skeletal remains are in a cave featuring parietal art implying

that the mortuary convention may have been ritual in context

therefore spiritual in nature. This may refer to community

care for the disabled or perhaps reverence for people who were

different from the rest of the group, another indication of

differential regard for certain people (Formicola 2007: 449).

Additionally, the significance of a rich burial may have been

reserved for certain persons who achieved prominent positions

due to the performance of important activities related to the

welfare of the group and were honoured afterwards by a gesture

of tribal respect and rememberance (Formicola 2007: 447).

Upper Palaeolithic burials compared to previous periods

The Upper Palaeolithic is thought to be the era when the Homo

sapiens sapiens (or Cro-Magnons) finally replaced European

Neanderthals, but the impetus for this change, whether it was

cultural or perhaps biological is a matter in dispute (Bar-

Yosef 2002: 361).. Many of the differences between the Middle

versus the Upper Palaeolithic lie in cultural and

technological changes accompanied by corresponding population

increases. Burial goods found in the excavation of elaborate

graves have revealed the following innovations: (1) prismatic

blade production evolved into the manufacture of bladelets and

microlithic stone tools, (2) shifts in core reduction working,

7

(3) the use of bone and antlers as raw materials, (4) grinding

and pounding with stone tools and (5) the systematic use of

body decoration, probably as a method of individual and group

identification (Bar-Yosef 2002: 362-363). Some grave artefacts

affirm that the source of supply of these materials were

several hundred kilometres away, thereby providing evidence of

long-distance exchange. Craved bone and stone objects of

abstract or stylistic features, are also preserved in some

graves, and are thought to be emblematic of early expressions

of symbolic logic and cognitive abilities (Bar-Yosef 2002:

362-367).

The differentiation between the Middle and Upper Palaeolithic

is denoted by the manner in which bodies were positioned and

how the use of red ochre was employed. Objects of perishable

materials were likely once present but have since become

invisible to the archaeological record. These characteristics

illustrate a changing complexity in the environment

communities were experiencing and were expressed in terms of

social changes. Rich burials became more common but appear to

be the exclusive domain for those of special rank within their

respective groups, with each burial having its own uniqueness

(Giacobini 2007: 19-20). The distinction between the Middle

(ca.100 – 40 kya) and the Late Palaeolithic is also

characterised by cultural innovations, denoting a significant

difference in the symbolic and cognitive capabilities of the

both societies. The evidence indicates internal viability and

no particular stereotypical burial norm. Individualistic

adornment and regard for the deceased implies that burial was

8

a unique event and quite important in the cultural context of

the group. In this way the dead were honoured, even though the

funerary ceremony allotted to them was brief brought by the

necessity of burying the dead quickly (Mallegni and Fabbri

1995: 133-134).

The Late Palaeolithic was also a time of climatic change

as temperatures became much cooler. Colder weather patterns

likely contributed to changing technologies as people had to

adjust their societal relationships and their integrations

with one another. This may offer an explanation for the

emergence of rich symbolic art, blade-tool industries and body

ornamentation as people attempted to cope with harsher climes

(Toth and Schick 2007: 1961).The standardised flint blade used

during the Middle Palaeolithic became shaped into an array of

functionally and stylistically diverse tool types during the

Upper Palaeolithic. Lances appearing in graves of this period

seem to usher in an era of projectile weapon, something which

could increase the reach of the thrower in bring down game at

greater distances and consequently with less risk to the

hunter. Safer hunting techniques provided a lower chance of

death and injury to the hunter. Accordingly the assurance of

more game for the community reduced the vulnerability of older

and younger members of the tribe giving them a greater

opportunity for survival (Ambose 2001: 1751).

In comparing the number of female to male grave there is

an unbalanced sex ratio with male inhumations occurring in

greater numbers. Perhaps this indicates a certain status

distinctions amongst populations in the Upper Palaeolithic 9

versus earlier periods however the female graves were just as

rich as the males’ by comparison. What may be more significant

is that cultural complexity and social status were becoming

more pronounced during the Upper Palaeolithic. This is most

exhibited by the evidence for larger communities and more

societal integration (Harrold 1980: 207-208).

Insights gained about society in the Upper Palaeolithic

The viability observed in mortuary conventions points to a

corresponding variability in sociocultural systems (Harrold

1980:196). Insights into how certain members of the society

were treated, such as the amount of labour expended in

mortuary preparations has definite implications in regards to

social stratification (Harrold 1980: 198). One of the most

spectacular burials from the Upper Palaeolithic period is from

a triple inhumation in Dolní Vêstonice in Moravia (c. 26 kya)

which feature three well preserved skeletons but with unusual

funerary signatures which may say something about the society

which interred them. Buried side by side and probably

simultaneously, the middle skeleton shows severe bone

deformity in the form of acute bowing of the limbs likely an

inherited disorder, while the other skeletons are male and

healthy in appearance. The skeletal remains however show a

commonality in genetic material. The male on the left has his

arm extended to the pubic region of the female while the male

on the right is positioned face down. The grave is dated to

26,500 BP in the late phase of the Upper Palaeolithic; a time

10

during which other areas across Europe were becoming rich in

artistic symbolism (Formicola et al 2001: 372). The funerary

pattern at this grave is the object of numerous

interpretations, the most accepted of which centres around the

possible social position of these individuals. Special

treatment after death is evident for persons whose role in

society must have had significance when they were living

(Formicola et al. 2001: 375-378).

The presence of blade technologies with bifacial points

and non-lithic material for tools, such as bone, antler and

ivory, were followed by more advanced technologies such as

hooked spear-throwers and bow and arrows found in some graves.

This is indicative of important advances in hunting and

weaponry (Toth and Schick 2007: 1943-1945, 1959-1960). Better

hunting capabilities made possible such things as the

production of sewed clothing and procurement of hides for

protection against the cold, therefore augmenting

sustainability of the village. The control of fire, as shown

by the increasing number of hearths at village sites means

that the density of populations was expanding. Rich grave

goods showed that symbolism was an important component in the

lives of ancient people and perhaps even emblematic of a

belief in religion. With a boost in population sustained by

changing cultural patterns, including the establishment of

permanent graves, villages may have assumed a sedentary

lifestyle or semi-sedentary at least, becoming more complex

and as reflected in mortuary rituals (Toth and Schick 2007:

1961).

11

Greater food gathering capability translated an enhanced

genetic structure in humans, facilitating intensified

resources utilisation and perhaps the exploitation of higher

latitudes. The Upper Palaeolithic groups were less limited in

their mobility and regional exchange with other people,

producing societies with greater cultural knowledge about the

exploration of natural resources and interaction with other

groups. Territories were expanded and hunting domains enlarged

(Ambose 2001: 1752).

Triple

interment at Dolní Vêstonice

(www.nbcnews.com/dolnivestonich)

One of the ways that scientific techniques shed insight

into the societies of the Upper Palaeolithic populations is

via chemical analysis of skeletal remains in further

determining the nutritional patterns of interred individuals

12

(Dobrovolskaya 2005: 433). Examination of the graves at

Sunghir reveals that a variety of food resources were utilised

consisting not only of mammals and fish but also of the

consumption of plants and invertebrates. This utilisation of

the environment provided a varied diet. Skeletons at this site

show irregular nutrition which is not surprising as diet

patterns are determined by availability of game and the breath

of faunal domains. Most of the dead at the Sunghir site show

healthier chemical composition in their bone structure,

indicating a more balanced and adequate diet was enjoyed by

them. Sunghir graves and chemical analysis are evidence that

these people were engaged in both hunting and gathering. The

relative availability of food sources implies the likelihood

of a higher level of survival making possible a corresponding

diversity in societal hierarchy (Dobrovolskays 2005: 436-437).

Stable isotope analysis of Late Upper Palaeolithic human

remains found at Grotta del Romito in Italy proved that these

individuals had primarily a terrestrial diet. These findings

conflict with studies of earlier communities which existed in

the same vicinity but whose diet at that time was primarily

fresh and salt water fish. This difference argues for an

increase in productivity of faunal gathering and/or perhaps

climate amelioration. The inhabitants may have changed their

foraging from the sea coast to the inland areas where they

specialised in harvesting wild plants and animals, presenting

a mixed and balanced diet with resultant healthier bone

chemistry (Craig et al. 2010: 2511).

13

New insights into the societies of the Upper Palaeolithic

appear at the grotto cave excavations at Romito which show

evidence of interbreeding. Endogamy is present in one of the

graves of an individual with dwarf characteristics attesting

to serious genetic disease caused by inbreeding Perhaps the

consequences of this practice may have become obvious with the

birth of this person and others. Realisation of the affects of

interbreeding was likely to have caused a change in societal

practices with the outlawing of sexual intercourse between

closely related tribal members. The fact that the dwarf seems

to been afforded all the burial honours of other persons

within the group suggests no particular stigma was attached to

his deformity, nevertheless the effects of interbreeding must

have been obvious (Mallegni and Fabbri 1995: 132).

Technological analysis conducted in 2004 on grave goods

from the Saint-Germain-la-Riviére, Upper Palaeolithic

inhumation site; propose that certain traits of the

inhabitants ran counter to what was previously believed about

hunter-gatherer groups. This insight centres about the

presence of perforated red deer canines imported from another

region. They must have been obtained through long-distance

trade and probably had the connotation of prestige items

(Vanhaeren and d’Errico 2005: 117). The presence of rare

objects likely heralded an individual’s membership in a

privileged social order. Rather than societies with equal

standing for its members there were marked divisions of tasks

and another case for social inequality and definite

14

variability in the social organisation (Vanhaeren and d’Errico

2005: 129-131).

Conclusion

The significance of elaborated human burials in the European

Upper Palaeolithic intimate evolving societal complexities

including emergence of group cohesion, individual delineation

symbolic cognition and technological advance. The presence of

grave goods in the residual material of single inhumations and

multiple graves points to cultural distinction between the

Middle and the Upper Palaeolithic. Burials are becoming unique

but at the same time they have a certain commonality,

affirming regional patterns in the manor by which early human

communities honoured their dead. The context of grave goods

from the Upper Palaeolithic can be seen as symbolic in nature

and if so, imply an important step forward in the progression

of humankind with regards to the cognitive capability of these

cultures. Insights gained into the Upper Palaeolithic from

these interpretations show that societies were more stratified

and less egalitarian than previously imagined. The presence of

innovative weaponry means that humankind had the capability to

hunt more productively and with reduced exposure to danger of

death or injury. Excavations of ancient sites suggest

increasing stability of tribal structures and the possible

15

recognition of a spiritual component to their existence. A

reduced risk to the more vulnerable members of the communities

allowed for enhanced population densities and the chance to

increase territories and thus domains for hunting and

gathering. This advantage probably brought them into contact

with other groups and facilitated exchange of finished goods

and raw materials Humankind was exhibiting traits which would

eventually become recognisable as a progression necessary

toward becoming modern humans.

Bibliography

Ambose, S.H. 2001. Palaeolithic Technology and Human

Evolution. Science 291: 1751-1752.

www.doi:10.1126/science.1059487, accessed 30/11/13.

Bar-Yosef, O. 2002. The Upper Palaeolithic Revolution. Annual

Review of Anthropology 31: 362-367. www.jstor.org/stable/4132885,

accessed 1/12/13.

Craig, O.E., Biazzo, M., Colonese, A., Di Giuseppe, Z.,

Martinez-Labarge, C., Lo Vetro, D., Lelli, R., Martini, F. and

Rickards, O. 2010. Stable isotope analysis of Late Upper

Palaeolithic human and faunal remains from Grotta del Romito

(Cosenza) Italy. Journal of Archaeological Science 37: 2511,

www.doi.10.1016/j.jas.2010.05010, accessed 11/12/13.

Dobrovolskaya, M. 2005. Upper Palaeolithic and Late Stone Age

Human Diet. Journal of Physiological Anthropology and Applies Human Science

16

24(4): 433, 436-437. www.jstage.jst.go.jp/browse/jpa ,

accessed 11/12/13.

Dobrovolskaya, M., Richards, M. and Trinkaus, E. 2012. Direct

Radiocarbon Dates for the Mid Upper Palaeolithic (Eastern

Gravettian) Burials from Sunghir, Russia. Bulletin Memorial Society

Anthropological Paris 24: 96, 97, 101, www.doi.10.1007/s132119-011-

0044-4, accessed 10/12/13.

Einwögerer, T., Friesinger, H., Händel, M., Neugebauer-

Maresch, C., Simon, U. and Teschleer-Nicola, M. 2006. Upper

Palaeolithic infant burials. Nature 444: 285.

www.doi.10.1038/444285a, accessed 14/12/13.

Formicola, V., Pontrandolfi, A. and Svoboda, J. 2001. The

Upper Palaeolithic Triple Burial of Dolní Vêstonice: Pathology

and Funerary Behaviour. American Journal of Anthropology 115:372. 375-

378.

www.onlinelibrary.wiley.com.ezproxy3.lib.le.ac.uk/doi/10.1002/

ajpa.1093, accessed 14/12/13.

Formicola, V. 2007. From the Sunghir Children to the Romito

Dwarf: Aspects of the Upper Palaeolithic Funerary Landscape.

Current Anthropology 48 (3) 446-447, 449, 451.

www.jstor.org.ezproxy3.lib.le.ac.uk/stable/10.1086/517592,

accessed 29/11/13.

Gamble, C. 1999. The Palaeolithic Societies of Europe. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

17

Giacobini, G. 2007. Richness and Diversity of Burial Rituals

in the Upper Palaeolithic. Diogenes 54 (19): 19-20.

www.doi:10.1177/0392192107077649, accessed 29/11/13.

Harrold, F.B. 1980. A Comparative Analysis of Eurasian

Palaeolithic Burials. World Archaeology 12 (2): 196, 198, 207-208.

www.jstor.org.ezproxy3.lib.le.ac.uk/stable/124403, accessed

29/11/13.

Lewin, R. and Foley, R.A. 2004. Principles of Human Evolution. Oxford:

Blackwell Publishing Company.

Mallegni, F. and Fabbri, P.F. 1995. Human Skeletal Remains

from the Upper Palaeolithic in Romito Cave (Papasidero,

Cosenza, Italy). Bulletin et mémoieres de la Société d’anthropologie de Paris

7(3): 132, 133-134.

www.persee.fr/web/revues/home/prescript/article/brnsap_0037_89

84, accessed 14/11/13.

Marom, A., McCullagh, J., Higham, G., Sinitsyn, A.A. and

Hedges, R. 2012. Single amino acid radiocarbon dating of Upper

Palaeolithic modern humans. Proceedings of the National Academy of

Science USA 109(18): 6878-6880.

www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.1116328109, accessed

14/11/13.

Svoboda. J. 2008. The Upper Palaeolithic burial area at

Predmostí: ritual and taphonomy. Journal of Human Evolution 54: 15,

31-32. www.doi.10.1016/j.jhevol2007.05.016, accessed 15/11/13.

18

Trinkaus, E. and Buzhilova, A.P. 2012. The Death and Burial of

Sunghir 1. International Journal of Archaeology 22: 655-666.

www.wileyonlinelibrary.doi:10.1002/oa.1227, accessed 15/12/13.

Toth, N. and Schick, K. 2007. Overview of Palaeolithic

Archaeology, in W. Henke and I. Tattersall (eds.) The Handbook of

Palaeoanthropology 12: 1943-1945, 1959-1960, 1961.

www.link.springer.com.ezproxy3.lib.le.ac.uk/book/10.1007/978_3

_540/33761-4, accessed 16/12/13.

Vanhaeren, M. and d’Errico, F. 2005. Grave goods from the

Saint-Germain-la-Rivière burial: Evidence for social

inequality in the Upper Palaeolithic. Journal of Anthropological

Archaeology 24: 117, 129-131. www.doi:10.1016/j.jja.2005.01.001,

accessed 17/12/13.

19