Chemical profiling and antioxidant activity of Bolivian propolis

Death in the Bolivian High Plateau: Burials and Tiwanaku Society

Transcript of Death in the Bolivian High Plateau: Burials and Tiwanaku Society

Acknowledgements

Chapter 1: Introduction 1 Endnote 3

Chapter 2: Archaeological burial data as a reflection of past societies 5 2.1.Introduction 5 2.2.Burialsandtheearlyyearsofarchaeology 5 2.3.TheprocessualapproachI:BinfordandSaxe 6 2.4.TheprocessualapproachII:The1970sandearly1980s 8 2.5.Postprocessualandcontextualcriticismofprocessualmortuarystudies 10 2.6.Theprocessualismofthe1990sandtheearly21stcentury 12 2.7.Someadditionalconsiderations 13 2.8.Discussion:thearchaeologyofdeathandtheTiwanakuState 14 Endnotes 15

Chapter 3: Central Andean mortuary practices and social differentiation in the light of the written sources of the 16th and early 17th centuries 17 3.1.Introduction 17 3.2.Didpronouncedsocialhierarchyexistinthepre-ConquestAndes? 18 3.3.Onthewaysinwhichthesocialpositionofapersonwasmanifestedinthepre-ConquestCentralAndes 19 3.4.ThefuneralritualsandancestorcultoftheIncarulers 19 3.5.Thefuneralritualsofthenobles 22 3.6.Thefuneralritualsofthecommoners 24 3.7.Deviantfuneralpractices 25 3.8.Thereligiousideologybehindfuneralrituals 26 3.9.InformationrelatedspecificallytotheCollasuyuquarter,theAymarapeople,andtheBolivianaltiplano 27 3.10.Discussion 30 Endnotes 31

Chapter 4: Ethnographic data on indigenous mortuary practices and social hierarchy 39 4.1.Introduction 39 4.2.Aymaramortuarypractices 40 4.3.SomedataonQuechuaandUrumortuaryrituals 47 4.4.AdministrativestructureandsocialhierarchyamongtheAymara 48 4.5.Discussion 49 Endnotes 50

Chapter 5: On the Tiwanaku culture 53 5.1.Introduction 53 5.2.Formativebeginnings 53 5.3.Thecentre:thecityofTiwanaku 55

Contents

Death in the Bolivian High Plateau

5.4.Tiwanakuheartland 63 5.5.TiwanakucoloniesandthenatureoftheTiwanakuState 66 5.6.Raised-fieldagriculture 72 5.7.Tiwanakuartsandcrafts 73 5.8.ThecollapseoftheTiwanakuState 79 Endnotes 80

Chapter 6: Review of archaeologically investigated Tiwanaku cemeteries and burials 85 6.1.Introduction 85 6.2.Tiwanaku–thecapital 85 6.3.Tiwanakuheartland 92 6.4.Theoutlyingprovinces 103 6.5.Discussion 108 Endnotes 110

Chapter 7: The archaeological investigations of the Late Tiwanaku/early post-Tiwanaku cemetery of Tiraska 115 7.1.Introduction 115 7.2.The1998investigations–burials1–7 115 7.3.The2002investigations–burials8–15 120 7.4.The2003investigations–burials16–32 124 7.5.14Cdates 140 7.6.Analysisanddiscussion 142 Endnotes 148

Chapter 8: Conclusions 151 8.1.ProblemsrelatedtotheinterpretationofTiwanakuburialpractices 154 8.2.ReviewofTiwanakuburialpractices 155 8.3.SomecomparisonsbetweentheTiwanakuandtheWari 159 8.4.Theoreticalconsiderations:thecaseoftheNorthCoastofPeru 162 8.5.Epilogue 165 Endnotes 166

References cited 169

�

Chapter �

Introduction

This study presents a multi-disciplinary analysis of the mortuary practices of the Tiwanaku culture of the Bolivian high plateau (i.e. altiplano), situated between the two Andean cordilleras, at an altitude of c. 3800–4000 m above sea level. The Tiwanaku State (Tiwanaku IV and V, c. AD 500–��50) – the heartland of which was situated in the southern Lake Titicaca Basin – was one of the most im-portant pre-Inca civilisations of the South Central Andes. Since the late �950s – and especially since the mid-�980s – our understanding of the Tiwanaku culture has increased rapidly. However, no systematic study of Tiwanaku burial practices – combining older and newer archaeological data with information from historical and ethnographic sources – has been available. My study aims precisely at filling this gap and in so doing at further advancing our understanding concerning the Tiwanaku.

The writings of Lewis Binford (e.g. �972) and Arthur Saxe (�970) in the late �960s and early �970s gave birth to a new socially interested study of prehistoric burial practices. Such North American scholars as Joseph A. Tainter (e.g. �977; �980), Lynne Goldstein (e.g. �98�), and John O’Shea (e.g. �98�; �984) further developed the methodology and theory of this so-called “archaeology of death”. The early years of the archaeology of death were tightly connected with the development of the so-called New Archaeology or processualist school. As a result of this, in the �980s some of its basic assumptions fell under attack by the mostly British/European postprocessualist school. Some of the criticism of the postprocessualists was well-founded, but the socially interested study of prehistoric mortuary practices has remained popular until the present day.

I think that the archaeology of death – in its processual sense – still has a lot to offer to contemporary archaeology. More specifically, I think that the Central Andean region of South America is an area especially suitable for this kind of study: Early historical sources – the great majority of which were written by Spanish conquistadors and clerics

– testify to the existence of multiple social “classes”, often separated by profound status differences. Additionally, the ethnographic writings of the �9th, 20th, and 2�st centuries can help us unravel some of the religious and philosophi-cal issues connected with the pre-Columbian burial practi-ces of the area. Furthermore, “rich” pre-Columbian tombs of, for example, the North Coast of Peru prove that inequa-lities in life were – at least among some Central Andean peoples – also reflected in death.

Mainly due to the richness of the archaeological record, the burials of many parts and periods of pre-Columbian Peru are relatively well known. Unfortunately, the same cannot be said concerning the pre-Columbian burial traditions of the Bolivian altiplano. Very little has been published concerning the burials of the Wankarani, Chiripa, and Tiwanaku cultures; the chullpa burial towers of the Late Intermediate Period/Late Horizon are a little better known. Hundreds of pre-Columbian burials have been excavated, however not all investigations have been adequately re-ported to the Dirección Nacional de Arqueología (from now on, DINAR) of Bolivia. Furthermore, detailed and individualised accounts of excavated burials rarely feature in published excavation reports and studies. All this has led to a situation in which very few “hard” archaeological facts concerning the pre-Columbian burial practices of the Bolivian altiplano are easily available to scholars.

The pre-Columbian burials of the Bolivian altiplano can be characterised as quite “poor” and simple. In the rela-tively humid climate of the high plateau, textiles and other burial offerings of an organic nature have very rarely sur-vived, and not a single one of the Bolivian burials exca-vated so far can compete with the magnificence and wealth of even moderately “rich” Moche and Sicán tombs of the North Coast of Peru. In the case of the Tiwanaku State, this lack of rich burials containing impressive quantities of gold and silver artefacts is particularly perplexing. The only archaeologically known burial approaching anything like a “royal” scale is that of San Sebastián. Enigmatically,

2

Death in the Bolivian High Plateau

this burial – which contained a number of impressive gold objects – came to light in the “provincial” Cochabamba Valley, not in the Tiwanaku heartland.

It could of course be argued that all the richest and most magnificent Tiwanaku burials have been looted during the long centuries of Colonial and Republican rule in Bolivia. Many high-status Tiwanaku tombs have indeed undoubtedly been looted at Tiwanaku and other important centres of the Tiwanaku State. However, had the richness of these burials come even close to that of the “royal” burials of the North Coast of Peru, knowledge of such extraordinary finds would undoubtedly feature in historical records. Furthermore, some of the artefacts uncovered in this manner would probably have ended up in public and private collections in Bolivia and abroad. As we do not possess knowledge of the discovery of spectacularly “rich” burials in the altiplano, and as Tiwanaku gold and silver are rather scarcely represented in public and private collections, the Tiwanaku case seems to differ quite notably from other Central Andean cases. In the Bolivian high plateau, religious beliefs may have differed from those of North and Central Peru, or society may have been organised in a different manner. It may also be that gold and silver simply were not that readily available to the inhabitants of the altiplano, or that for example textiles were considered the most important media for the representation of the status of the deceased.

In addition to this brief introduction, my study includes six long “essays” and a concluding chapter. As this is a mono-graph, there are of course cross textual references between the essays. However, most of them can also be read on their own, separated from the larger context.

Chapter 2 presents the theoretical basis of my study. I discuss Binford and Saxe’s influential writings concern-ing the anthropology and archaeology of death and then examine how these affected the (North American) mortu-ary studies of the �970s and early �980s. I also treat the criticism aimed at processualism by Ian Hodder and his postprocessual followers, before concluding the chapter with a discussion of the contemporary state of processu-ally influenced mortuary research and presenting my own theoretical stance. I am of the opinion that in order to carry out meaningful research related to mortuary practices, one has to take into account not only the burials but the ar-chaeological (and if possible, historical and ethnographic) record as a whole. This provides a “background” against which to project and test one’s hypotheses and results.

Chapter 3 deals with the chronicles and other early his-torical sources written in the �6th and early �7th centuries, following the Spanish Conquest of the Inca Empire. In my reading of these (published) sources I have concen-trated on certain specific issues, such as how strongly Inca society was stratified, how the differences between the

“classes” and statuses were manifested, and what kinds of mortuary practices and religious beliefs related to death and the afterlife were represented? One of the basic points I try to make in chapter 3 is that pronounced social hier-archy undoubtedly existed in the Central Andes before the Conquest – i.e. it is not a purely European concept which we would be trying to project to a totally different social reality. Most of the data contained in the early historical sources concerning the mortuary practices of the Late Horizon/early Colonial period is strongly skewed towards the Cuzco area and Inca aristocracy. However, some data related specifically to the Bolivian altiplano is also avail-able and is discussed at the end of chapter 3.

In chapter 4 I treatise on the ethnographic sources related to the contemporary indigenous peoples inhabiting the Bolivian high plateau – particularly the Aymara. These sources are less “racist” than the writings of the chroniclers, but – on the other hand – the customs and beliefs described in them are separated from the pre-Columbian era by a centuries-long period of cultural change and syncretism. I am quite critical of the tendency of many Andeanists to quite indiscriminately project historical and ethnographic data onto the pre-Columbian past. However, used with due caution, these sources can help us in our interpretation of the archaeological record – in this case Tiwanaku mortu-ary practices.

The archaeological part of this study begins with chapter 5, in which I present a fairly detailed analysis of the Tiwanaku culture. Even if much of this data does not directly concern burials, for the correct interpretation and contextualisation of mortuary practices it is very important to be aware of the “bigger picture”. One of the more specific aims of chapter 5 is to prove that many facets of the archaeological record point to the existence of rather marked social stratification within the Tiwanaku State.

In chapter 6 I have tried to collect and present as much information related to previously excavated and published Tiwanaku cemeteries and burials as is presently available. The chapter is organised geographically in the sense that at first I discuss burials excavated at Tiwanaku, then the burials of the immediate Tiwanaku heartland, and finally burial data from more faraway areas under Tiwanaku control/influence. The level of detail of the data available for study differs widely from site to site and excavation to excavation, and chronological control is often poor. However, I am convinced that chapter 6 offers a fairly accurate picture of the social, contextual, and geographical variation apparent in excavated (and published) Tiwanaku burials. Furthermore, the collected data will hopefully offer a firm basis from which scholars can plan and undertake further studies related to Tiwanaku mortuary practices.

In chapter 7 I present my own archaeological research at the Late Tiwanaku/early post-Tiwanaku cemetery of

3

1 • Introduction

Tiraska. This cemetery – situated on the island of Cumana near the south-eastern shore of Lake Titicaca – acciden-tally came to the attention of archaeologists in �998. That same year, seven burials were excavated. The investiga-tions at Tiraska were continued in 2002 and 2003. My colleagues and I have excavated altogether 32 burials at Tiraska – making the site one of the very few more or less comprehensively investigated Tiwanaku cemeter-ies in the altiplano. The (surviving) grave goods – from zero to two rather “Decadent” ceramic vessels per tomb – were not by any means “spectacular”. However, in many cases the preservation of human bone was good enough to enable osteological analyses and �4C dating – even up to DNA analyses(�). In chapter 7 I discuss each tomb exca-vated at Tiraska individually. I also describe and analyse the ceramic and other finds. Furthermore, I present and discuss Tiraska’s �2 radiocarbon dates. At the end of the chapter, I present my interpretation of the archaeological contexts of Tiraska.

Chapter 8 sums up the research presented in this study. Many chronological and otherwise problematic hindrances arise in the objective interpretation of Tiwanaku mortuary practices. However, I am of the opinion that I have arrived at some rather important insights. For one thing, significant regional differences characterise the Tiwanaku burial record, probably testifying to the existence of different ethnic (or other) groups, each with their own beliefs and customs regarding death and the afterlife. Furthermore, despite the marked stratification characterising Tiwanaku society, no magnificently rich “royal” tombs featuring a

host of sacrificial victims seem to have existed. In this sense, the Tiwanaku case offers a warning against drawing conclusions concerning the structure of any particular society solely on the basis of burial data.

Some terminology has to be defined here. In my mind, the Tiwanaku ceramic styles (as defined by Wendell C. Bennett in 1934) and cultural phases (as defined by Carlos Ponce Sanginés and most recently redefined by Alan L. Kolata and John W. Janusek) do not correlate in a satisfactory way. For this reason, I use the term style to refer specifically to the ceramic sequence and the term phase to refer to the socio-cultural sequence.

For me a cist is a stone-lined subterranean burial facil-ity – very often incorporating at least some upright stone slabs in its walls. I refer to burials without apparent struc-ture (apart from the burial pit) as (simple) pit burials. I apply the terms burial, tomb, and grave interchangeably – i.e. they do not carry any special nuances. For me, a burial or a tomb is a single burial facility and/or context. Consequently, a pit into which three deceased were buried counts as one single burial. By the term individual burial I refer to a tomb into which only a single deceased was buried. Conversely, a tomb containing the remains of two or more persons is a collective burial. By primary burial I refer to the burial of a corpse without much physical manipulation – in most cases quite soon after death. In the case of a secondary burial an incomplete corpse was buried. It was manipulated prior to its (final) interment, for example by removing the soft tissues and only burying (some of) the bones.

Endnote

�. In 200�–02, Ville Pimenoff of the Department of Forensic Medicine at the University of Helsinki tested whether it would be possible to extract ancient mitochondrial DNA from Tiraska bone samples. He concluded that sufficiently well-preserved ancient mtDNA was indeed present. (Pimenoff & Korpisaari 2002.) However, the mtDNA research had to be discontinued because of lack of funding.

114

Death in the Bolivian High Plateau

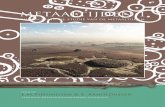

Fig 7.1. AerialviewofthevillageofTiraskaanditssurroundings.NotetheextensivefieldterracesliningMountTiraska.PhotocourtesyoftheInstitutoGeográficoMilitarofBolivia.

115

Chapter 7

The archaeological investigations of the Late Tiwanaku/early post-Tiwanaku cemetery of Tiraska

7.1. Introduction

The Late Tiwanaku/early post-Tiwanaku cemetery of Tiraska – located at the coordinates S 16º19’26.8” – W 68º42’50.5”, on the south-eastern shore of Lake Titicaca (Figs. 5.11, 6.9, and 7.1–7.3) – was discovered in July 1998, when three cist tombs accidentally came to light in the course of construction work. At that time, the Finnish-Bolivian “Chullpa Pacha” project was carry-ing out fieldwork in the neighbouring village of Qiwaya. Fortunately, our group was notified of the discovery of the above-mentioned tombs, and we proceeded to ex-cavate seven burial contexts at Tiraska during the 1998 field season. Four years later, in 2002, the funding of the “The Amazonian Interests of the Incas” project, financed by the University of Helsinki, enabled my team and I to return briefly to Tiraska in order to investigate eight more burials. In December 2002, the University of Helsinki granted funding for a new project titled “Formations and Transformations of Ethnic Identities in the South Central Andes, AD 700–1825”. During its first field season – 2003 – this archaeological-historical project carried out further archaeological investigations at Tiraska.(1)

In the three following subchapters, I give a detailed account of the 1998, 2002, and 2003 excavations at Tiraska. Later on, I discuss the 14C dates. At the end of the chapter, I will analyse the archaeological material recovered in the course of the investigations.

7.2. The 1998 investigations – burials 1–7

7.2.1. Introduction

On July 10th, 1998, the “Chullpa Pacha” project staff was preparing for a normal day of fieldwork at Qiwaya, when Sr. Sabino Lima – a resident of the neighbouring village of Tiraska – approached us. He told us that something ancient

had come to light in his village and offered to lead us to the place of discovery. The archaeologists and anthropologists in our multi-disciplinary team decided to visit Tiraska – located only some 500 m to the north of Qiwaya – at once. In Tiraska, we were guided to a spot some 40 m east of the village’s Catholic church. The owner of this plot, Sr. José Quisbert Coronel, had decided to even out his courtyard and had contracted men from La Paz to do the digging. Not long after the work had begun, an interesting stone construction had come to light. Following the discovery, the plot owner had halted the work and sent Sr. Lima to fetch us.

Between the uncovered structure’s stones we could see a cavity, at the bottom of which was some human bone. It was clear that the workers had stumbled upon a pre-Columbian cist tomb. To the north of this first burial, we could discern the superstructures of two other cists. The plot owner was anxious for the work on his courtyard to proceed as quickly as possible, but we were able to nego-tiate one day for the archaeological investigation of the three accidentally discovered cists (burials 1–3). As the day proceeded, a fourth burial context – this time a collec-tion of human remains and broken ceramic vessels with no apparent burial architecture attached – came to light, also requiring investigation. Although we managed to study the four burial contexts in the allotted time of one day, un-fortunately the hurry we were in meant that the level of documentation was often far from satisfactory.

The following day, a fourth cist (burial 5) was excavated close to burials 1–3. On October 20th, 1998, archaeological work continued at Tiraska. This time, a test pit of 1.5 m x 1.5 m was opened on an artificial terrace situated above the Catholic church of the village, c. 30 m to the west of the first accidentally discovered cists. The excavation of this pit led to the discovery of two more burials. Burial 6 – a large chamber tomb – was situated in the south-western part of the test pit, burial 7 – a smaller cist tomb – in the eastern part of the pit. (Sagárnaga 1999: 46-48.)

116

Death in the Bolivian High Plateau

Fig. 7.3. ThegeneralmapoftheLateTiwanaku/earlypost-TiwanakucemeteryofTiraska.Thelocationsofburials1–5areapproximations.

Fig. 7.2. ThevillageofTiraskaseenfromthesouth(photoRistoKesseli).

117

7 • The archaeological investigations of the cemetery of Tiraska

The seven burials investigated in 1998 are described in greater detail below.

7.2.2. Burials 1–7

Burial 1 (Figs. 7.4–7.5)

This burial was the southernmost of the three cists (burials 1–3) situated in a row close to each other. The cist’s cap lay c. 20 cm below present ground surface. The cap was formed by three longish stone slabs, the longest of which measured 72 cm. The grave chamber was hexagonal in plan. The chamber’s maximum inner diameter was 50 cm, and its walls were formed by irregularly set stones. In the course of the centuries, some soil had filtered into the cist, but c. 70 cm of space still separated the soil lying at the bottom of the chamber from the capstones. As the removal of the soil proceeded, the more or less normally preserved remains of a 10–15-year-old possible female(2) (Villamor 1999) soon came to light. The deceased had been buried in a seated, flexed position, with her back against the chamber’s north wall and her face towards the south. (Sagárnaga 1999: 41-44.)

The only (surviving) grave goods encountered were two ceramic vessels – a tazon and a vasija – which lay to the southwest of the deceased. The vasija was found inside of the tazon.(3) (Sagárnaga 1999: 44.) On its exterior surface the tazon (base diameter 92 mm, rim diameter 147 mm, height 77 mm) features decoration in black and white on

red. A small piece is missing from the vessel’s rim, which also shows other signs of wear. The one-handled vasija (base diameter 60 mm, rim diameter c. 60 mm, height 94 mm) features decoration in dark brown and white on light brown on its exterior surface and inside its rim. As is the case with the tazon, the vasija’s rim also shows signs of wear. The giving of worn and even broken ceramic vessels as grave goods was frequent at Tiraska, and will be dis-cussed in more detail below.

Burial 2 (Fig. 7.5)

This was the middle burial of the three cists (burials 1–3) situated in a row close to each other. Unfortunately, very little information is available concerning its inves-tigation. The cist’s cap lay c. 20 cm below the present ground surface. The tomb’s structure was rather irregular. The burial chamber contained the quite poorly preserved remains of a 30–45-year-old individual of undetermined sex. This deceased had been buried in a seated, flexed po-sition. A single ceramic vessel accompanied the deceased. (Villamor 1999.) Originally, this vasija (base diameter 76 mm, rim diameter 86 mm, height 127 mm) featured elabo-rate decoration in black on red over its exterior surface. Unfortunately, most of this decoration has now been lost due to the erosion of extensive areas of the slip once cover-ing the vessel’s exterior and the interior of its rim. A wavy line painted in black circles the interior of the vessel’s rim. The vasija’s spouted handle is missing. As it was not found in the excavation, it had very probably broken off before the vessel was placed in the cist.

Fig. 7.4. Burial1.Notethehumanremainsandthetwoceramicvessels.(PhotoRistoKesseli.)

Fig. 7.5. The tazon (no.1,height77mm)andvasija(no.2,height94mm)ofburial1andthevasija(no.3,height127mm)ofburial2(drawingAnttiKorpisaari).

118

Death in the Bolivian High Plateau

Burial 3 (Figs. 7.6–7.7)

This burial was the northernmost of the three cists (burials 1–3) situated in a row close to each other. Burial 3 was situated only 2 m to the south of the corner of the modern house depicted in the general plan of the site (Fig. 7.3). As in the two previous cases, the cist’s cap lay c. 20 cm below the present ground surface. The cap was formed by two longish stone slabs – each measuring c. 65 cm x 30 cm x 10 cm – and several smaller stones. Although some soil had fil-tered into the cist, at the time of the opening of the chamber c. 60 cm of space still separated the soil lying at its bottom from the capstones. The chamber’s total depth was c. 80 cm. The burial chamber was hexagonal in plan and had the inner diameter of c. 60 cm. The cist’s structure was quite elaborate; large upright stone slabs formed the bases of the walls, while their upper parts consisted of 3–4 courses of smaller stones. The cist housed the well preserved remains of a 30–35-year-old male(4) (Villamor 1999). He had been buried in a seated, flexed position, facing south or south-east, in the north-western part of the cist.(5) Two ceramic vessels – a kero and a sahumador – rested in the southern part of the chamber, at the deceased’s feet.

The kero (base diameter 88 mm, rim diameter 148 mm, height 148 mm) features decoration in black on orange on its exterior surface, in addition to which a wavy line painted in black circles the interior of the vessel’s rim. The kero also features a very slightly protruding exterior torus. The vessel’s rim shows signs of wear. The two-handled sahumador (base diameter 99 mm, rim diameter 170 mm, height 94 mm) is un-slipped and totally lacking in decoration. A small piece is missing from its rim, and was not found in the cist.

Burial 4 (Fig. 7.8)

In many ways, burial 4 is the most enigmatic burial context encountered at Tiraska. This burial was situated c. 6.5 m to the west-southwest of burial 3, and only c. 1 m south of the wall of the modern house neighbouring burials 1–5. The finds of burial 4 included a large quantity of badly preserved human bone, an almost whole tazon, almost all of the shards of a broken tazon and a broken kero, and two large basal shards of a vasija. The finds rested at the depth of c. 30–45 cm below the present ground surface, in a matrix of loose soil. No cist structure or other kind of burial architecture was related to these finds, which lay in apparent disorder covering an area of c. 1 m2. The most logical explanation for the formation of burial 4 is that the contents of some destroyed Late Tiwanaku/early post-Tiwanaku cist tombs would have been dumped and buried here – probably because of the fear caused by ancient human remains and artefacts among the local Aymara. The destruction of these hypothetical tombs may be related to the building of the house neighbouring burials 1–5.(6)

Fig. 7.6. Burial3.Notethehumanremainsandthetwoceramicvessels.(PhotoRistoKesseli.)

Fig. 7.7. Thesahumador(top,height94mm)andkero(bottom,height148mm)ofburial3(drawingAnttiKorpisaari).

119

7 • The archaeological investigations of the cemetery of Tiraska

The almost whole tazon (base diameter 78 mm, rim diameter 126 mm, height 73 mm) – which is only missing one rather large rim shard – is quite sparsely decorated in black on red. In addition to the missing shard, the vessel’s rim also shows other signs of wear. However, as this and the other vessels of burial 4 had probably been looted and reburied, it is not clear whether they were already worn and/or broken when originally buried. It has been possible to reconstruct the broken tazon and kero of burial 4 more or less completely. The tazon (base diameter 81 mm, rim diameter 122 mm, height 64 mm) features decoration in black and orange on red on its exterior surface. The kero (base diameter 67 mm, rim diameter 146 mm, height 145 mm) features elaborate polychrome decoration in black, orange, and white on red on its exterior surface. The upper register is dominated by the depictions of two flamingos, while cross motifs circle the vessel’s lower body. The two decorative fields are separated by a very slightly protruding exterior torus. The reconstructed kero’s rim is extremely worn. The surviving basal part of a vasija (base diameter 76 mm, maximum height of the preserved part 99 mm) is

decorated in black, brown, and light brown on brownish red.

The badly preserved human remains of this burial context belong to three individuals: a c. 30-year-old male, a c. 20-year-old male, and a c. 15-year-old possible female (Villamor 1999). As all of Tiraska’s investigated Late Tiwanaku/early post-Tiwanaku cists were individual burials containing from zero to two ceramic vessels, the presence of the partial remains of three individuals and four Tiwanaku affiliated ceramic vessels in this burial context accords well with a hypothesis according to which burial 4 would represent the reburied contents of three destroyed cists.

Burial 5

This cist tomb was situated a little to the south of burial 1. Its structure was in a state of total disorder, which led its investigator (Sagárnaga) to assume that the burial had been looted prior to investigation. No ceramic grave goods were encountered, which might be interpreted to support Sagárnaga’s opinion. The cist did contain the badly preserved remains of a 20–30-year-old individual of undetermined sex(7). (Sagárnaga 1999: 44; Villamor 1999.)

Burial 6 (Fig. 7.9)

This subterranean chamber tomb was situated on the lower terrace of the cemetery, immediately to the east and c. 5 m above the courtyard of Tiraska’s Catholic church. The chamber’s cap lay quite close to the level of the present ground surface. The beehive-shaped burial chamber was rather spacious. In plan, it was ellipsoidal, measuring 105 cm x 92 cm. The chamber’s depth was 120 cm, and its base was paved.(8) The burial held the poorly preserved remains of a 35–40-year-old male(9) (Villamor 1999). In addition to these human remains, the chamber contained a crude, globular-bodied vasija (base diameter 63 mm, maximum

Fig. 7.8. Thekero(top,height145mm),oneofthetwotazones (centre,height64mm),andthebasalfragmentofavasija(bottom,height99mm)ofburial4(drawingAnttiKorpisaari).

Fig. 7.9. Thesemi-completevasijaofburial6(photoRiikkaVäisänen).

120

Death in the Bolivian High Plateau

height of the preserved part 108 mm), which is missing its neck and handle. Some guinea pig bones were also present. (Sagárnaga 1999: 47.) These might be interpreted as evi-dence of food offered to the deceased and/or of divination.

Burial 7 (Fig. 7.10)

This cist tomb was situated immediately to the east of burial 6. A single stone slab served as the cist’s cap. The burial chamber was notably smaller than that of burial 6.(10) The cist held the poorly preserved remains of a single indi-vidual.(11) This deceased was accompanied by two ceramic vessels – a kero and a tazon. The burial chamber’s base was paved. (Sagárnaga 1999: 48.)

The kero (base diameter 78 mm, rim diameter 143 mm, height 172 mm) features a protruding exterior torus and sparse decoration in black on red on its exterior surface. The tazon (base diameter 96 mm, rim diameter 149 mm, height 96 mm) is decorated in black and cream on red on its exterior surface.

7.3. The 2002 investigations – burials 8–15

7.3.1. Introduction

In August 2002, I was presented with an opportunity to briefly return to Tiraska. During three intensive days of fieldwork (August 14th–16th, 2002), our four-member team excavated and documented eight cist tombs, all of which were situated on the lower terrace of the cemetery. All eight burials investigated were visible on the ground surface, and with the exception of burial 13, all had lost their caps prior to excavation. In addition to the eight burials already men-tioned, we excavated a test pit of 1.5 m x 1.5 m in order

to attempt to locate better preserved burials still covered entirely by soil. Unfortunately, we did not encounter more burials, but we did find hundreds of ceramic shards and other interesting cultural material.

7.3.2. Burials 8–15

Burial 8 (Fig. 7.11)

This burial was situated on a slope and had been almost completely destroyed by erosion and present day human activity. Only a single upright stone slab, which once be-longed to one of the cist’s walls, remained in situ. A kero – missing its rim but otherwise intact – could be partly seen on the present ground surface, where the burial chamber was originally situated. This vessel (base diameter 72 mm, maximum height of the preserved part 109 mm) features polychrome decoration in black, orange, and white/cream on red on its exterior surface. As this vessel was found partly above ground, it is impossible to know whether it was broken already at the time of deposition, or whether it was damaged later. Small bone fragments were spread around the burial. Since this cist had been so completely destroyed, we only collected the above-mentioned finds, without investigating the burial more profoundly. Due to the disturbed burial context and the extremely fragmentary state of the recovered bone material, data on the age and sex of the deceased is not available.

Burial 9 (Fig. 7.11)

Similarly to almost all of the burials investigated in 2002, this small cist had lost its cap, and the tops of the upright slabs forming the walls of the burial chamber rose above the present ground surface. Following the removal of c. 40 cm of soil – which had filled the cist after it had lost

Fig. 7.10. Thekeroandtazonofburial7(photoRiikkaVäisänen).

121

7 • The archaeological investigations of the cemetery of Tiraska

its cap – we encountered two ceramic vessels: a prosopo-morphic kero (base diameter 84 mm, maximum height of the preserved part 101 mm) with polychrome decoration in black, orange, and white/cream on red on its exterior surface and a small tazon (base diameter 78 mm, rim di-ameter 114 mm, height 59 mm) with sparse decoration in black on red on its exterior and interior surfaces. The kero has lost its rim, and as the missing pieces were not found in the cist, it seems that the vessel was broken already at the time of deposition.

The diameter of the cist was only 30–40 cm, which would seem to point to the fact that it had been intended to house a young deceased. Unfortunately, only very fragmentary bone remains could be recovered from this burial, prevent-ing the osteological verification of this assumption. Only one small phalanx was found to be human. Additionally, probable dog vertebras and an upper mandible fragment, as well as some small rodent bones were identified. (Villamor 2002.) A single stone slab formed the floor of the burial chamber.

Fig. 7.11. Thetenceramicvesselsofburials8–14.Vessels1and4fromburial9;vessel2fromburial8;vessels3and10fromburial12;vessel5fromburial10;vessels6and7fromburial14;vessel8fromburial13;vessel9fromburial11.(DrawingAnttiKorpisaariandRistoKesseli.)

122

Death in the Bolivian High Plateau

Burial 10 (Fig. 7.11)

This burial was found in a very poor condition. The cist had lost its roof slab(s) and the upper parts of its walls. The rim of a small escudilla – broken into three large shards – protruded above the present ground surface. It was pos-sible to almost completely reconstruct this vessel (base di-ameter 65 mm, rim diameter 102 mm, height 60 mm). It features quite simple decoration in black and white/cream on red on its exterior surface, as well as decoration in black on red inside its rim. The vessel was probably broken after deposition, and seems to have been in quite good condition when put in the cist. The original diameter of the cist seems to have been about 40–45 cm. Very few human remains were found in this burial, but some long bone fragments and a vertebra probably belonging to an adult of indetermi-nable sex could be identified (Villamor 2002).

Burial 11 (Fig. 7.11)

This cist had lost its roof slab(s), but had otherwise re-mained more or less intact. The burial chamber was framed by three upright stone slabs which enclosed a space with a diameter of 40–55 cm. The cist contained the more or less normally preserved, articulated remains of a 4–6-year-old possible female (Villamor 2002). The position in which these remains were found indicates that she had been tightly flexed and rested on her left side. The deceased was probably originally set in a flexed sitting position in the western part of the chamber (with her face towards the east), and at some point of the decomposition process had fallen onto her side. A single tazon lay to the east of the deceased. This vessel (base diameter 96 mm, rim diameter 144 mm, height 81 mm) features quite simple decoration in black on red on its exterior surface. Below the unpaved

floor of the cist, we encountered a cultural layer containing carbon and quite a lot of fish bones and scales.

Burial 12 (Figs. 7.11–7.12)

This cist, which had lost its capstone(s), was situated directly in between burials 8 and 10. The burial chamber was quite spacious (with a diameter of c. 60 cm). The human remains contained in this burial were found in an advanced state of decay. Judging by a femur fragment, the deceased had been a young person of indeterminable sex (Villamor 2002). Two ceramic vessels accompanied this deceased. The first of these is a tazon (base diameter 97 mm, rim diameter 147 mm, height 71 mm). It features relatively simple decoration in black and cream/white on its exterior surface, in addition to which a rather carelessly painted wavy line circles the interior of the vessel’s rim. The cist also contained a rather crude vasija (base diameter 68 mm, rim diameter 71 mm, height 112 mm) featuring sparse decoration in black on red. As both vessels have partly eroded surfaces, it is hard to tell whether, for example, the rim of the tazon was damaged before or after its deposition in the cist.

Burial 13 (Figs. 7.11 and 7.13–7.15)

Burial 13 was the best preserved of all the burial contexts investigated in 2002. Some of the small stones at the tops of the cist’s walls rose a little above the present ground surface, but the cist’s cap (formed by two long stone slabs) remained intact. Because of this, relatively little soil had filtered into the burial chamber. The structure of this quite spacious cist (with a diameter of c. 60 cm) was impressive: The lower parts of the walls were formed by large upright slabs, on top of which lay 2–3 rows of smaller stones. The two slabs of the cap (each with a length of c. 80 cm) rested on top of the topmost row of wall stones. The depth of the burial chamber was 63 cm.

Fig. 7.12. Burial12.Notethetwoceramicvessels.(PhotoAnttiKorpisaari.)

Fig. 7.13. Thecapofburial13(photoAnttiKorpisaari).

123

7 • The archaeological investigations of the cemetery of Tiraska

The cist housed the quite well preserved and articulated remains of a 30–45-year-old female(12) (Villamor 2002). Judging by the position in which her bones were found, it would seem that she was originally placed in a seated, flexed position against the north wall of the burial chamber (with her face towards the south-southeast), and that later on she had fallen on her side during the process of decom-position. A tazon (base diameter 101 mm, rim diameter 140 mm, height 86 mm) had been placed to the east of the deceased. This vessel, which features crude decoration in black on red, was found in three large shards, but could be completely reconstructed. The tazon is very interesting: before it had been placed in the cist it had broken in two and been repaired – this is evidenced by small drilled holes situated on both sides of the ancient fracture.

Burial 14 (Fig. 7.11)

This small cist (with a diameter of only 30–40 cm) was framed by upright stone slabs, the tops of which rose above the present ground surface. The cap and upper parts of the walls had disappeared. The small burial chamber housed the fragmentary remains of a 4–8-year-old child of indeterminable sex (Villamor 2002). The deceased was accompanied by two ceramic vessels, which lay in the south-eastern part of the burial chamber. The first of these vessels is a small vasija (base diameter 49 mm, maximum height of the preserved part 89 mm) featuring polychrome decoration in black, cream, and white on red. This vessel had lost its rim and neck prior to deposition. The cist also contained a “plate” (base diameter 63–65 mm, maximum height of the preserved part 31 mm) improvised from the basal part of a broken vasija, cuenco, or escudilla. The only surviving decoration on this piece is a part of a hori-zontal band painted in black on red. A stone slab covered a part of the cist’s floor.

Burial 15

This cist had lost its capstone(s), and a huge eucalyptus root had penetrated the burial chamber displacing some of the wall slabs. Because of the destruction caused by the root, the form of the burial chamber was quite irregu-lar (with the chamber’s diameter varying from 40 to 65 cm). The cist contained the regularly preserved remains of a 12–15-year-old juvenile of indeterminable sex. No ceramic vessels were encountered. It is possible that the deceased had not received any ceramics as part of his/her grave goods, but it is also possible that the cist had been looted. Among the fill of the chamber we found a small “stone cone”.

7.3.3. Test pit 1 (2002)

All of the burials described above – investigated in 2002 – were in one way or another visible at the present ground surface. With the intention of locating better preserved burials still covered entirely by soil, we excavated a test pit of 1.5 m x 1.5 m – test pit 1 – two meters to the north of burials 6 and 7. Test pit 1 was excavated in two layers (0–20 cm and 20–30 cm) down to a depth of 30 cm, in addition to which an area of 80 cm x 80 cm in the south-eastern part of the pit was excavated down to a depth of 50 cm (layer 3: 30–50 cm). Unfortunately, we could not locate any new burials. We did, however, find other types of cul-tural material. The plentiful ceramic material (578 shards) from test pit 1 is mostly utilitarian in nature. Decorated shards were quite rare, mostly featuring straight or angular black lines on red. The great majority of this ceramic mate-rial is of the Tiwanaku V style. Tiwanaku IV style shards were very rare, although some were found in layer 1. In addition to ceramic shards, we found lots of bone and four small “stone cones”.

Fig. 7.14. Burial13.Notethehumanremainsandtherimofthebrokentazon.(PhotoAnttiKorpisaari.)

Fig 7.15. Thetazonofburial13.Notethedrilledholestestifyingtopre-Columbianrepairwork.(PhotoAnttiKorpisaari.)

124

Death in the Bolivian High Plateau

7.3.4. Surface collection

In addition to carrying out small-scale excavations, in 2002 we also carried out some unsystematic surface col-lection in the area of the present day village of Tiraska. In the fields situated near the shore of Lake Titicaca (and only some 1–2 m above the present surface of the lake), we located a zone at least 200 m wide with a lot of superficial ceramic shards (dating to the Tiwanaku IV/V phase, the Late Intermediate Period, and the Inca era). We found this superficial cultural material to continue until the second or third terraces situated above the Catholic church of Tiraska (approximately 30–35 m above the present level of the lake). Judging by these observations, it would seem that the area of the present day village of Tiraska was quite intensively (and more or less continuously) inhabited from at least the Tiwanaku V phase (c. AD 800–1150) until the Inca era (c. AD 1450–1532).

7.4. The 2003 investigations – burials 16–32

7.4.1. Introduction

In August-October 2003, I finally got an opportunity to carry out archaeological investigations of a somewhat larger scale in Tiraska. As the excavations of 2002 were very short-term in nature, we had mostly concentrated on investigating isolated burial cists, the outlines of which were visible above the present ground surface. With con-siderably more time and resources at hand in 2003, this strategy was changed into one in which larger (and deeper) units were excavated in order to expose pre-Columbian burials still covered entirely by soil. We began (modestly) with a single unit of 1.6 m x 2 m, unit 1, around which more units (of varying shapes and sizes) were opened as the work progressed. Soil was removed in layers of 20–30 cm, mostly using picks and spades. Only soil from special contexts – such as burials – was sieved.

The 2003 field season proved to be rather successful. We excavated a total area of 57.69 m2. Our main excavation area – situated on the main cemetery terrace immediately above and to the east of the Catholic church of Tiraska, c. 25 m above the present level of Lake Titicaca – had an area of 44.44 m2 (Fig. 7.3). We also excavated an area of 11 m2 on the upper cemetery terrace, close to burials 1–5, and a test pit of 2.25 m2 on a lower terrace, closer to the shore of Lake Titicaca. A total of 17 new burials and some other interesting features were investigated and documented. On both of the two terraces on which we excavated burials, we also encountered deep cultural layers. In the course of our excavations, we collected over 10,000 ceramic shards (about 68 kg of material), c. 10 kg of animal bone, and some bone and stone tools and tool fragments.

Below, each excavation unit, burial, and feature is dis-cussed individually.

7.4.2. Main excavation area (Fig. 7.16)

Unit 1

This unit was 1.6 m (N-S) x 2 m (E-W) in size. It was situ-ated a couple of meters to the east of burials 9 and 13. Three tombs (burials 16, 17, and 19) were encountered in this unit. Additionally, the remains of a human baby (feature 1), severely disturbed by a blow from a workman’s pick, were encountered near the eastern limit of the unit. The first excavation layer was from 0 to 20 cm, the second from 20 to 50 cm, and the third from 50 to c. 60 cm. The finds of layer 1 included 247 ceramic shards (in total, 1817 g) and 77 bone fragments (in total, 183 g). Layer 2 contained 137 shards (1205 g) and 130 bone fragments (309 g). Layer 3 yielded 70 shards (399 g) and 57 bone fragments (116 g).

Burial 16

This 25–30-year-old male(13) (Clavijo 2003) had been buried face down, arms flexed along his sides, the upper part of the legs extended and the lower part of the legs flexed, so that the remains of the feet rested near the level of the pelvis. The length of the burial, oriented WSW-ENE, with the head to WSW, was c. 100 cm. The cranium rested between one large stone and another smaller stone, and a number of other stones rested on top of the body. Excepting the previously-mentioned stones, no burial architecture was associated with this rather superficial burial (situated 10–30 cm below the present ground surface). The outlines of the burial pit could not be defined due to the extreme hardness and dryness of the soil. A piece of llama bone, a possible wichuña (i.e. weaving tool), was found at the level of the pelvis near the deceased’s right side. No other offerings were encountered aside from this possible grave good. The cap of burial 17 rested almost immediately below the cranium and thoracic region of the deceased of burial 16. However, the close association between these two burials may be unintentional.

Burial 17 (Figs. 7.17–7.19)

As was already stated, the cap of this burial rested almost immediately below the cranium and thoracic region of the deceased of burial 16, at a depth of 20–30 cm below the present ground surface. The cap was formed by rather long stone slabs, in between which smaller stones had been inserted. The stone-lined burial chamber had a depth of 60–70 cm and a maximum interior diameter of c. 100 cm. Overall, the chamber was rather spherical in form. In the chamber’s NNW part there was a slightly raised “bench”.

125

7 • The archaeological investigations of the cemetery of Tiraska

Fig. 7.16. Theplanofthe2003mainexcavationareasituatedonthelowerterraceofthecemeteryofTiraska.

126

Death in the Bolivian High Plateau

The base of the chamber – which was situated 23.14 m above the present level of Lake Titicaca – was partly paved.

The human remains contained in this burial were quite poorly preserved, but as fragments of only the cranium and the long bones of the legs were recovered, it is pos-sible that we are dealing here with a secondary burial. The bones rested in the southern part of the chamber. The de-ceased had been a c. 45-year-old male(14) (Clavijo 2003). A little to the north of the human remains, two ceramic vessels were found. One of these vessels was a small one-handled vasija (base diameter 55–59 mm, rim diameter 63 mm, height 124 mm) decorated with geometrical designs painted in black on red on its exterior surface. A large frag-ment is missing from the vessel’s rim, and was not found in the burial. The other vessel was an extremely crudely manufactured undecorated greyish-brown small “cup” (base diameter 74–77 mm, rim diameter c. 80 mm, height 34 mm). Both the human remains and the ceramics were found in the burial chamber itself, not on the “bench”.

Burial 19 (Fig. 7.20)

This burial was situated near the southern limit of unit 1, extending somewhat to unit 3. The burial position of this adult female(15) (Clavijo 2003) is the strangest so far docu-mented in Tiraska: From the waist upwards, the remains of the deceased rested horizontally at a depth of 60–65 cm below the present ground surface, face down, and arms flexed, with the head to the SSW. The bones of the lower legs were, however, found in a nearly vertical position (the bones of the feet were discovered c. 20 cm below the present ground surface). Rather large stones rested near to and on top of the human remains, but these stones would seem to have been thrown into the pit and/or on top of the deceased, and did not represent any kind of regular burial architecture. We did not recover any burial offerings and were unable to discern the outlines of the burial pit.

Feature 1

The quite poorly preserved remains of a human baby were discovered near the south-western corner of unit 1. The context of these rather superficial (c. 20–30 cm below present ground surface) remains was severely damaged by a direct hit from a workman’s pick (for which reason the burial did not receive an “official” number). No burial architecture or grave goods were related to the human remains.

Unit 2

This unit of 2 m x 2 m was situated immediately to the east of unit 1. The most noteworthy features of unit 2 were a

Fig. 7.17. Thecapofburial17(photoAnttiKorpisaari).

Fig. 7.18. Thegravechamberofburial17.Notetheraised“bench” in the top-left corner of the image.(PhotoAnttiKorpisaari.)

Fig. 7.19. Thetwoceramicvesselsofburial17(photoAnttiKorpisaari).

127

7 • The archaeological investigations of the cemetery of Tiraska

simple pit burial (burial 18) located near the northern edge of the unit and a cist tomb (burial 21) situated near the south-eastern corner of the unit. Near the western edge of the unit, there was a large boulder and some smaller stones. A huge boulder covered most of the north-eastern quadrant of the unit. The first excavation layer was from 0 to 20 cm and the second from 20 to 50 cm. The finds of layer 1 included 231 ceramic shards (in total, 1668 g), 72 bone fragments (in total, 125 g), and 1 obsidian flake. Layer 2 contained 403 shards (2911 g), 291 bone fragments (412 g), and 2 obsidian flakes.

Burial 18

This burial was found when parts of a human cranium came to light between a couple of stones 166 cm N and 50 cm E of the south-western corner of unit 2. As the exca-vation of these human remains proceeded, we discovered the rest of the skeleton of a 6–7-year-old child(16) (Clavijo 2003) to the east of the cranium. The deceased had rested either on his/her stomach or back; due to the poor state of preservation of the skeleton, this was hard to determine, but I tend to favour the on-the-stomach position. The de-ceased’s arms were flexed along his/her sides, the legs flexed slightly to one side. The head pointed more or less towards the west. We noted no associated burial architec-ture, and it was impossible to define the limits of the burial pit. No grave goods were found. The burial was very su-perficial, with the last of the human remains situated at the depth of 17 cm below the present ground surface.

Burial 21 (Figs. 7.21–7.22)

This smallish cist was situated just south of a huge boulder which formed a part of the north-western wall of the burial chamber. A single stone slab measuring 58 cm x 30 cm x 10 cm functioned as the cap of the chamber. This cap lay at the depth of c. 40 cm below the present ground surface. The grave chamber was almost rectangular in form, with the longer axis (NW-SE) measuring 40–45 cm, and the shorter one (NE-SW) measuring 25–30 cm. The walls of the chamber were mostly formed by 1–2 larger stone slabs each. The depth of the burial chamber was c. 50 cm. Its base was situated 23.72 m above the present level of Lake Titicaca. The remains of the 9-month-old deceased (Clavijo 2003) were very poorly preserved. Consequently, we could not define the baby’s burial position.

During the centuries, some stones had fallen from the upper parts of the cist, breaking one of the two ceramic vessels deposited in the tomb. However, this vessel – a kero (base diameter 83 mm, height of the preserved part 99 mm) featuring a slightly protruding exterior torus and decorated with horizontal lines in black and orange on red on its exterior surface – seems to have been broken prior to the time of deposition, as its rim shards were not re-

Fig. 7.20. Partialviewofburial19(photoAnttiKorpisaari).

Fig. 7.21. Burial 21. Note the ceramics. (PhotoAnttiKorpisaari.)

covered in the excavation. In addition to the remains of the kero, a tazon (base diameter 90–91 mm, rim diameter 142 mm, height 77 mm) was situated in the north-western corner of the burial chamber. This vessel is decorated with black, white, and orange scroll-motifs on red on its exte-rior surface. Near the base of the vessel, there is a narrow horizontal band in black, and a wavy line painted in black circles the vessel’s interior rim. A part of the tazon’s surface is badly worn. On this same side there is even a small hole, and some small pieces are missing from the vessel’s rim. The tazon may have been broken and/or worn already at the time of deposition, but later damage caused by falling stones and erosion cannot be ruled out.

128

Death in the Bolivian High Plateau

Unit 3

This unit, measuring 1 m (N-S) x 4 m (E-W), was situated immediately to the south of units 1 and 2. The placement and size of this unit were dictated by the fact that some of the wall stones of a cist tomb (burial 20) were discovered in the south-eastern corner of unit 1, and that the remains of the deceased of burial 19 continued into the southern profile of unit 1. The first excavation layer was from 0 to 20 cm and the second from 20 to c. 50 cm. The finds of layer 1 included 248 ceramic shards (in total, 1928 g) and 50 bone fragments (in total, 110 g). Layer 2 contained 492 shards (3490 g) and 215 bone fragments (592 g).

Burial 20 (Fig. 7.23)

The cap of this cist lay c. 45–50 cm below the present ground surface and was formed by three rather irregular-

shaped stone slabs. The stone-lined burial chamber was quadrangular in plan. Large upright stone slabs formed two of the chamber’s walls. A third wall was formed by what appears to be a large rock encountered during the digging of the burial pit and incorporated into the cist construc-tion. Smaller stones formed the fourth wall. Three large stone slabs, situated to the east of the grave chamber, had also been incorporated into the cist construction. With the inclusion of these huge stones, the outer diameter of the structure was increased to c. 160 cm. The interior diameter of the “mouth” of the burial chamber was 47 cm, and the depth of the chamber c. 67 cm. The interior diameter of the base of the chamber varied from c. 45 cm (E-W) to c. 60 cm (N-S). The base of the burial chamber – the southern edge of which was paved – was situated 23.25 m above the present level of Lake Titicaca.

We found the remains of a 10–11-year-old child (Clavijo 2003) in a rather poor state of preservation in the northern

Fig. 7.22. Thetazonandkeroofburial21(photoAnttiKorpisaari).

Fig. 7.23. Thetazonandchallador (upsidedown)ofburial20(photoAnttiKorpisaari).

129

7 • The archaeological investigations of the cemetery of Tiraska

part of the chamber. As the long bones of the legs were found rather vertically flexed near the NNW wall of the cist, the deceased had probably originally rested in a seated, flexed position with his/her back against the mentioned wall. Two ceramic vessels lay to the south of the human remains. The first of these vessels is a small tazon (base diameter 88–89 mm, rim diameter 136 mm, height 76 mm), rather sparsely decorated in black on red on its exterior surface. The other vessel is a so-called challador, a tall cup with a very narrow base (base diameter 33–34 mm, rim diameter 126 mm, height 159 mm). This vessel is the only one of its kind among the Tiraska finds.(17) The upper part of the challador’s exterior surface features step-designs painted in black, orange, and white on red. Both vessels are intact, but their rims show some signs of wear.

Unit 4

This unit was only 1.2 m x 1.2 m in size. It was opened to the north of units 1 and 2 in order to uncover a chamber tomb (burial 22), some of the wall stones of which had been encountered in the north-western corner of unit 2. The first excavation layer was from 0 to 20 cm and the second from 20 to c. 40 cm. The finds of layer 1 included 72 ceramic shards (in total, 568 g) and 81 bone fragments (in total, 146 g). Layer 2 contained 60 shards (613 g) and 57 bone fragments (142 g).

Burial 22 (Fig. 7.24)

About 40–47 cm of soil covered the cap of this chamber tomb, which was formed by three rather long stone slabs, in between which smaller stones had been placed. The grave chamber was smaller than those of the two other

intact chamber tombs excavated at Tiraska (burials 6 and 17). Burial 22 did not feature a “bench” similar to that of burial 17. The walls of the rather hexagonal burial chamber were covered with small stones. The inner diameter of the chamber varied from 50 to 65 cm, with the longest axis running in the direction NW-SE. The depth of the burial chamber was c. 70 cm. Its base – a part of which was covered with a stone slab – was situated 23.19 m above the present level of Lake Titicaca.

In the burial chamber, we discovered the rather poorly preserved remains of a 25–30-year-old female(18) (Clavijo 2003), buried in a seated, flexed position facing E/ESE. Additionally, a small vasija (base diameter 57 mm, rim diameter c. 48 mm, height 101 mm) was encountered in the southern part of the chamber. This crude and undeco-rated vessel was missing its handle and most of its rim. The handle was found in the excavation, but the rim was seemingly damaged before deposition.

Unit 5

This unit of 2 m x 2 m was opened directly to the south of unit 3. Its principal features included a small cist (burial 23) situated near the south-western corner of the unit and a small semi-complete utilitarian ceramic vessel. This vasija had broken on the spot into about a dozen shards and has since been partly reconstructed. The vessel (base diameter c. 36 mm, height of the preserved part 90 mm) (Fig. 7.25) is decorated in black on light brown. The shards of the vasija were found 65 cm N and 0 cm E of the south-western corner of the unit, at a depth of 15–20 cm, i.e. almost directly above burial 23. Additionally, in the south-eastern corner of the unit, at a depth of 29–34 cm below the present ground surface, we encountered a rather

Fig. 7.24. The semi-complete vasija of burial 22(photoAnttiKorpisaari).

Fig. 7.25. Thepartly reconstructedsmallvasijaofunit5(photoAnttiKorpisaari).

130

Death in the Bolivian High Plateau

regular stone pavement, measuring some 100 cm (N-S) x 70 cm (E-W) and continuing into the southern and eastern profiles of the unit.

The first excavation layer was from 0 to 20 cm and the second from 20 to c. 50 cm. The finds of layer 1 included 218 ceramic shards (in total, 1842 g) and 19 bone fragments (in total, 57 g). Layer 2 contained 442 shards (3165 g), 211 bone fragments (503 g), and one half of a perforated stone.

Burial 23 (Figs. 7.26–7.28)

The cap of this small cist lay 35 cm below the present ground surface. It was formed by a single rather quadran-gular stone slab measuring 37 cm x 30 cm x 7 cm. The shape of the burial chamber was rather irregular, with four of its five walls consisting of more than one stone. The inner diameter of the chamber was c. 35 cm, and its depth c. 40 cm. The base of the burial chamber – a part of which was covered with several small stones – was situated 23.65 m above the present level of Lake Titicaca.

Due to the small size of this cist, I initially assumed that the deceased would have been a child. The study of the poorly preserved human remains indicated, however, that they were in fact those of a 25–30-year-old male (Clavijo 2003). In the light of this finding, the small size of the cist and the poor preservation of the human remains might perhaps indicate a burial of a secondary nature. Unfortunately, the advanced state of decay of the human remains prevented any detailed observations concerning the articulation (or disarticulation) of the skeleton. All that can be stated in this regard is that the preserved human remains were con-centrated in the northern part of the burial chamber.

A small “plate” (base diameter 58 mm, height of the pre-served part 35 mm) improvised from the basal part of a broken vasija, cuenco, or escudilla rested near the south-ern edge of the chamber. This undecorated “vessel” resem-bles the “plate” of burial 14.

I find it very probable that this cist and the small utilitarian ceramic vessel, found c. 15 cm above its cap, were related. The small vessel might be interpreted as a final offering (or an offering of remembrance) meant to benefit the departing soul.

Unit 6

This unit of 2 m x 2 m was situated directly to the west of unit 5 (and to the south of unit 3). Extending to a depth

Fig. 7.26. Thecapofburial23(photoAnttiKorpisaari).

Fig. 7.27. Burial23.Notethefragmentaryskullontheleftandtheceramic“plate”ontheright.(PhotoAnttiKorpisaari.)

Fig. 7.28.The“plate”ofburial23(photoAnttiKorpisaari).

131

7 • The archaeological investigations of the cemetery of Tiraska

of c. 50 cm, this unit was remarkably rich in finds. Along with over a thousand (mostly utilitarian) ceramic shards, we found some interesting stone artefacts, such as two bolas weights/maze heads and six small “stone cones”. We also encountered a single cist tomb – burial 24. This small cist was situated near the eastern limit of the unit, cutting slightly into unit 5. In comparison with the more eastern excavation units, unit 6 contained markedly fewer boulders.

The first excavation layer was from 0 to 20 cm and the second from 20 to 50 cm. For the first 20–30 cm excavated, the colour of the soil was noticeably dark. In the western half of the unit, we excavated a third level – from 50 to 70 cm – in order to find out the depth of the cultural layer. In comparison with the two previous layers, this third one was markedly poorer in finds. At a depth of 60–65 cm, we encountered a hard reddish soil, which contained very little cultural material. For this reason, we terminated the excavation at a depth of 70 cm.

The finds of layer 1 included 333 ceramic shards (in total, 3403 g), 158 bone fragments (in total, 298 g), 1 stone bolas weight/maze head, and 4 “stone cones”. Layer 2 contained 749 shards (5651 g), 406 bone fragments (1250 g), 1 stone bolas weight/maze head, 2 “stone cones”, and 2 obsidian flakes. Layer 3 yielded 77 shards (426 g) and 26 bone frag-ments (82 g).

Burial 24 (Fig. 7.29)

This cist was situated only 35 cm to the northwest of burial 23. The cap lay 30–35 cm below the present ground surface. Three stones, the largest of which measured 54 cm x 25 cm x 9 cm, formed the cap. The burial chamber was rather ovoid in shape, with its longest axis (E-W) measur-ing c. 50 cm and the shortest (N-S) measuring 40 cm. The depth of the chamber was 40–45 cm. Most of the chamber’s wall surfaces consisted of rows of small stones, but in the western part some larger stone slabs had also been used. Three small stones rested on the chamber’s base, but these did not form a proper pavement. The chamber’s base was situated 23.48 m above the present level of Lake Titicaca.

The more or less normally preserved remains of a 20-year-old female(19) (Clavijo 2003) rested in the south-western part of the cist. The positioning of the long bones of the legs suggests that the deceased had originally sat here, facing west or northwest. A single ceramic vessel, a rather large one-handled vasija (base diameter 105–109 mm, rim diameter 79 mm, height 124 mm), lay to the east of the human remains. This vessel is missing its handle and large parts of its rim. Once again, the missing pieces were not found in the cist, although all the excavated soil was carefully sieved. The vasija is decorated with rather elabo-rate geometric designs (step and scroll-motifs, spirals, and

wavy lines) painted in black on red on its exterior surface. A wavy line painted in black circles the interior of the ves-sel’s rim. One side of the vessel’s body is severely eroded and even has a small hole.

Unit 7

This unit of 2 m x 2 m was situated directly to the east of unit 5. Unit 7 was opened in order to study how the stone pavement observed in the south-eastern corner of unit 5 continued to the east. The feature was found to continue for c. 50 cm, until it met with a rather straight double-row of large stones, running approximately in the direc-tion NNW-SSE. The function of this stone alignment or “wall” is not clear. At a depth of c. 30 cm below the present ground surface, most of the unit was covered with stones of different sizes and excavation could not proceed much further down. No burials were found in this unit. The first excavation layer was from 0 to 20 cm and the second from 20 to c. 30 cm. The finds of layer 1 included 132 ceramic shards (in total, 1109 g) and 18 bone fragments (in total, 42 g). Layer 2 contained 202 shards (1281 g), 127 bone fragments (231 g), and 1 obsidian flake.

Unit 8

This unit of 2 m (N-S) x 1 m (E-W) was situated to the east of units 2 and 3 and to the north of unit 7. The unit was ex-cavated in order to expose a small cist tomb first observed in the eastern profile of unit 3. Along with this cist (burial 25), large stones – continuing the alignment observed in unit 7 – were uncovered. The first excavation layer was

Fig. 7.29. Thevasijaofburial24(photoAnttiKorpisaari).

132

Death in the Bolivian High Plateau

from 0 to 20 cm and the second from 20 to 50 cm. Because of the presence of some boulders, only parts of the unit could be excavated down to a depth of 50 cm. The finds of layer 1 included 97 ceramic shards (in total, 710 g) and 17 bone fragments (in total, 41 g). Layer 2 contained 166 shards (1249 g), 95 bone fragments (208 g), and 1 “stone cone”.

Burial 25

This cist was situated between the two rows of large stones which formed the above-mentioned stone alignment. Some 50 cm of soil covered the cap, which consisted of a single stone slab (measuring 41 cm x 28 cm x 9 cm) and some small stones. The burial chamber was almost quadrangular in plan [with its interior diameter varying from 22 cm (N-S) to 30 cm (E-W)]. All four walls of the chamber were formed by either large stone slabs or boulders, in addition to which the western wall had a sort of an “extra” interior wall formed by a smaller stone slab. Very interestingly, the huge boulder forming the northern wall of this cist also formed a part of burial 21, situated 85 cm to the NNW of the burial presently discussed. The depth of the chamber was 36 cm, and its base was situated 23.76 m above the present level of Lake Titicaca.

In the burial chamber, we found only a few fragments of the fragile and poorly preserved remains of a baby (Clavijo 2003). Consequently, it was impossible to determine the burial position of the deceased. No ceramics or other sur-viving grave goods were present.

Unit 9

This unit of 1 m (N-S) x 3 m (E-W) was situated to the south of units 5 and 6. At a depth of c. 20 cm, the stone

pavement – first encountered in unit 5 – covered most of the eastern half of this unit. In the central part of the unit, two small, quadrangular stone-lined features (features 2 and 3) – almost like miniature tombs – were discovered rather close to the present ground surface. In order to pre-serve these curious features, the area in question was ex-cavated only down to a depth of 10–15 cm. Along with the discovery of the pavement – which was also left intact – this left only the westernmost area of the unit, 1 m x 1 m in size, to be excavated further down. This area yielded quite a lot of ceramic shards and a small pointed copper/bronze tool (Fig. 7.30). To the west, unit 9 overlapped with test pit 1 of the 2002 excavations by c. 20 cm.

The first excavation layer was from 0 to 20 cm. In the westernmost square meter, the second layer was from 20 to 50 cm and the third from 50 to c. 60 cm. The finds of layer 1 included 427 ceramic shards (in total, 3186 g), 122 bone fragments (in total, 250 g), and 1 obsidian flake. Layer 2 contained 251 shards (1412 g), 176 bone frag-ments (435 g), 2 obsidian flakes, and the above-mentioned small metal artefact. Layer 3 yielded 103 shards (450 g) and 29 bone fragments (86 g).

Feature 2 (Fig. 7.31)

This small, quadrangular stone-lined feature – oriented almost perfectly according to the cardinal directions – was situated 83 cm N and 123 cm E of the south-western corner of unit 9. The soil-filled feature was encountered 10 cm below the present ground surface. Its outer measurements were 20 cm x 23 cm. Its small stone slabs framed an inner area of 14 cm x 15 cm. A short distance down inside the feature, we encountered a rather circular stone slab (with a diameter of 14–18 cm), which may have originally functioned as the cap of the feature. The feature’s depth was 16–17 cm. The only finds inside the feature were a few small fragments of bone and some small ceramic shards. These finds may well have been introduced into the feature along with the fill, and so are not necessarily related to the function of the feature. This feature – along with feature 3 – may represent the “tomb” of a deceased whose body was unavailable for burial (see subchapter 3.9 for an ethno-historical description of such funeral practices). Alternatively, the pair of features may have had a function related to ancestor worship (see subchapter 7.6.3).

Feature 3 (Fig. 7.31)

This small, rectangular stone-lined feature was very similar in shape, size, and orientation to feature 2. It was situated 31 cm N and 140 cm E of the south-western corner of unit 9 – about 33 cm to the south of feature 3. Only c. 5 cm of soil covered this feature, the interior dimensions of which were 13 cm (N-S) x 19 cm (E-W). The feature – which did not have a cap – was c. 15 cm deep and filled with soil. The

Fig. 7.30. ThefourmetalfindsoftheTiraskainvestigations.Thetwotumisaresuperficialfinds.Thepointedtoolontheleftisfromunit9’slevel2,andthepossibletumistemisfromunitA2’slevel3.Allfourfindsareofcopper/bronze.(PhotoAnttiKorpisaari.)

133

7 • The archaeological investigations of the cemetery of Tiraska

fill contained few finds. This feature is probably contem-poraneous with feature 2, and the two undoubtedly once had a similar function.

Unit 10

This unit of 1 m (N-S) x 3 m (E-W) was situated to the south of units 5 and 7. Most of the unit was covered either with the stone pavement – first noted in unit 5 – or rather large boulders. Other than the pavement, no notable features were encountered. The first excavation layer was from 0 to 20 cm. Due to the extensive nature of the pavement – which was left intact – the second layer rarely reached below 30 cm. The finds of layer 1 included 292 ceramic shards (in total, 1924 g), 70 bone fragments (in total, 191 g), and 2 obsidian flakes. Layer 2 contained 152 shards (1079 g), 114 bone fragments (280 g), and 1 obsidian flake.

Unit 11

We opened this unit of 2 m (N-S) x 3 m (E-W) imme-diately to the south of unit 10 in order to find out how

the stone pavement continued towards the south. A large boulder dominated the centre of this unit and was found to form the southern limit of the pavement. We encoun-tered two cist tombs (burials 26 and 27) near the limits of this unit [in order to expose burial 26, we added an extension of 60 cm (N-S) x 20 cm (E-W) to the east of the original unit]. In addition, we located a possible third tomb (feature 4) near the unit’s southern limit. Near the south-eastern corner of the unit and quite near the present ground surface, various large shards belonging to a single kero were found. This vessel (base diameter 62 mm, rim diameter 111 mm, height 122 mm) (Fig. 7.32), decorated in black, orange, and white on brownish red on its exterior surface, could be partly reconstructed. A little to the east of the large boulder, we encountered a partial human mandi-ble at a depth of c. 15–20 cm.

The first excavation layer was from 0 to 20 cm and the second from 20 to c. 30 cm. The finds of layer 1 included 295 ceramic shards (in total, 2356 g), 103 bone fragments (in total, 231 g), 2 “stone cones”, and 1 obsidian flake. Layer 2 contained 29 shards (171 g), 34 bone fragments (51 g), and 1 “stone cone”.

Burial 26

This small cist was situated 147 cm N and 285 cm E of the south-western corner of unit 11. Its cap – covered with only c. 5 cm of soil – was formed by a rather irregular-

Fig. 7.31. Features2 (top)and3 (bottom) (photoAnttiKorpisaari).

Fig. 7.32. Thepartiallyreconstructedkeroofunit11(photoAnttiKorpisaari).

134

Death in the Bolivian High Plateau

shaped single stone slab measuring 45 cm x 42 cm x 13 cm. The diameter of the irregularly-shaped burial chamber varied from c. 20 cm (E-W) to c. 30 cm (N-S). Single, large stone slabs formed two of the chamber’s walls, while the other two walls consisted of various smaller stones. The chamber’s depth was c. 40 cm, and its base was situ-ated 24.02 m above the present level of Lake Titicaca. The remains of the deceased – a 6–12-month-old baby (Clavijo 2003) – were in a poor and fragmentary state. No ceramics or other surviving grave goods were present.

Burial 27

This small cist was situated 43 cm N and 30 cm E of the south-western corner of unit 11. One larger stone slab (measuring 33 cm x 21 cm x 8 cm) and some smaller stones formed the cap, which was located 12–13 cm below the present ground surface. The more or less pentagonal burial chamber was quite shallow (depth 24–27 cm) and half-filled with soil. Low stone slabs, topped by a single row of smaller stones, formed the chamber’s walls. The chamber’s base measured 21 cm (N-S) x 18 cm (E-W) and was situated 23.86 m above the present level of Lake Titicaca. Hardly any human remains had survived, making the assessment of the age and sex of the deceased impossible (Clavijo 2003). However, judging by the extremely small size of the cist, the deceased was probably a very young child. We recovered no ceramics or other grave goods.

Feature 4

This feature, situated 25 cm N and 125 cm E of the south-western corner of unit 11, consisted of some upright stone slabs – resting at a depth of c. 30 cm below the present ground surface – which formed a partial circle. As a large eucalyptus root passed near these stones, it is possible that they were the surviving parts of a small cist tomb, destroyed by the root. This hypothetical cist would have had an interior diameter of c. 20–25 cm. However, as we encountered no bones, bone fragments, teeth, and/or grave goods inside the partial circle of stones, this feature cannot be designated a burial with any certainty. Nevertheless, one has to keep in mind that burials 26 and 27, situated near feature 4, also contained very few bone fragments and no surviving grave goods.

Unit 12

We opened this unit of 1 m (N-S) x 3 m (E-W) immedi-ately to the south of unit 11. Burial 15, excavated in 2002, dominated the western part of the unit. We encountered no further burials or other notable features. The first excava-tion layer was from 0 to 20 cm and the second from 20 to c. 30 cm. The finds of layer 1 included 202 ceramic shards (in total, 1398 g) and 131 bone fragments (in total, 222 g).

Layer 2 contained 54 shards (400 g) and 103 bone frag-ments (178 g).

Unit 13

We opened this unit of 3 m (N-S) x 1 m (E-W) to the east of units 11 and 12. Consequently, this unit assimilated the area of the extension sized 60 cm (N-S) x 20 cm (E-W) which we had earlier added to the east of unit 11 in order to expose burial 26. We encountered no new burials or other notable features. The first excavation layer was from 0 to 20 cm, and the second – only in the northern part of the unit – from 20 to c. 30 cm. The finds of layer 1 included 105 ceramic shards (in total, 637 g), 29 bone fragments (in total, 44 g), and 1 “stone cone”. Layer 2 contained 30 shards (217 g), 17 bone fragments (49 g), and 1 “stone cone”.

7.4.3. Excavations on the upper terrace of the cemetery (Fig. 7.33)

In addition to the above-described 13 units of the main excavation area, in 2003 we also investigated an area of 11 m2 on the upper cemetery terrace, close to burials 1–5. The three excavation units of the upper terrace – along with their most interesting features – are described below.

Unit A1