Consumer decision in the context of a food hazard: the effect of commitment

Transcript of Consumer decision in the context of a food hazard: the effect of commitment

Consumer decision in the context of a food hazard:the effect of commitment

Michele Graffeo Æ Lucia Savadori Æ Katya Tentori ÆNicolao Bonini Æ Rino Rumiati

Received: 17 September 2007 / Accepted: 21 January 2009 / Published online: 12 February 2009

� Fondazione Rosselli 2009

Abstract The European market has faced a series of recurrent food scares, e.g.

mad cow disease, chicken flu, dioxin poisoning in chickens, salmons and recently

also in pigs (Italian newspaper ‘‘Corriere della Sera’’, 07/12/2008). These food

scares have had, in the short term, major socio-economic consequences, eroding

consumer confidence and decreasing the willingness to buy potentially risky food

products. The research reported in this paper considered the role of commitment to a

food product in the context of food scares, and in particular the effect of commit-

ment on the purchasing intentions of consumers, on their attitude towards the

product, and on their trust in the food supply chain. After the initial commitment

had been obtained, a threat scenario evoking a risk associated with a specific food

was presented, and a wider, related request was then made. Finally, a questionnaire

tested the effects of commitment on the participants’ attitude towards the product.

The results showed that previous commitment can increase consumers’ behavioural

intention to purchase and their attitude towards the food product, even in the

presence of a potential hazard.

Keywords Food hazards � Commitment � Attitude � Trust

1 Introduction: commitment and choices

In the past 10 years, Europe has experienced numerous threats related to food (e.g.

mad cow disease, chicken flu, etc.). Alarming news about potential hazards related

M. Graffeo (&) � L. Savadori � K. Tentori � N. Bonini

Decision Research Laboratory, Department of Cognitive and Education Sciences,

University of Trento, Corso Bettini, 31, 38068 Rovereto (Trento), Italy

e-mail: [email protected]

R. Rumiati

Department of Developmental Psychology, University of Padova, Via Venezia 8, 35131 Padua, Italy

123

Mind Soc (2009) 8:59–76

DOI 10.1007/s11299-009-0054-5

to food consumption have scared the population, decreasing their positive attitude

towards products and damaging their trust in the various economic actors involved

in the food chain production. Often, a major effect of such food threats has been an

immediate and drastic fall in demand for the risky products (see Pennings et al.

2002). For example, in Italy, 3 weeks after the European Council Early Warning on

the so called ‘‘chicken flu’’, consumers reacted with a sharp change of their

consumption choices. Chicken meat consumption decreased by 40%, as reported by

the Italian Farmer Association Coldiretti (Panorama, October 27 2005, p. 43). The

producers and sellers of food products have devised a variety of strategies to counter

the effects of these crises. For example, during the mad cow crisis, butchers’

associations in various parts of Italy organized a series of public events where

butchers prepared cuts of beef, ate them and offered them to passers-by for free. The

message implicit in these public initiatives was simple: ‘Italian beef is safe’, and the

consumers who ate the meat offered to them probably agreed with this message.

This marketing strategy reminds of a well-known psychological mechanism:

‘commitment’. People tend to take account of their previous actions as an important

element in their future behaviour, and the desire for action consistency is a well-

known facet of human behaviour. Even during a food crisis, consumers who on one

occasion consider a certain food to be not dangerous will probably maintain this

stance also in the future.

In social psychology, the term commitment is used to indicate a pledging orbinding of the individual to behavioural acts (Kiesler and Sakumura 1966).

Individuals bound or committed to an act tend to avoid behaviours that contradict

their initial commitment. At the same time they are willing to take actions coherent

with their commitment, even when they are aware of the cost inherent in this course

of action. A sense of commitment may be induced in various ways. Early studies on

commitment typically described a very simple form of manipulation: subjects were

requested to perform a simple and effortless act, and to do so only once. They were

then requested to perform another act, which was coherent with the first one but

more demanding. Those who complied with the initial, simple request showed a

higher propensity to comply with the following, effortful request as well. The

second act may have implied an increased effort or the spending of money, or it

might even have endangered the person’s well-being. People may feel committed to

their choices even if they merely agree to do something without carrying out any

action. For example, Freedman and Fraser (1966) asked a group of housewives to

fill in a questionnaire about the soaps they used, but they did not have the chance to

actually do so. The intention to comply with this lesser request—without any real

action—was sufficient to raise the rate of compliance with a larger request, an in-

depth investigation of all the cleaning products in the household.

Freedman and Fraser (1966) applied commitment to a persuasion technique

named ‘‘foot-in-the-door’’. First a small request was made (e.g. ‘‘please put a small

sign on your car’’). Many people complied with such a trivial request (‘‘the foot is

placed in the door’’). Then a larger request, which was the real goal of the

persuasion technique, was made (e.g. ‘‘please install a big sign in your yard’’).

Those who accepted the initial request felt committed to their previous action and

often agreed to the following request as well, and ‘‘the door opens completely’’.

60 M. Graffeo et al.

123

Other effects of commitment have been shown by Cialdini et al. (1978). A first

group of students was asked to participate in an experiment, and only after they had

agreed were they informed that the experiment would be run at 7 o’clock in the

morning. The majority of the students confirmed their choice even after realizing the

full cost of their decision. A second group was informed from the outset that

the experiment would be run in the early morning, and only a minority agreed to

participate.

Joule (1987) used different forms of commitment manipulation to convince

students to quit smoking for at least 18 h. For example, he asked students to quit

smoking for 2 h, and then the students filled in a questionnaire related to the

decision to stop smoking. Alternatively, students were informed of the full cost of

their decision (they had to refrain from smoking for 18 h) only after they had

agreed to quit smoking for a period of time. In both cases (escalation of requests

or initial agreement followed by full information), the manipulation of

commitment was highly successful: the behavioural compliance with the major

request was significantly higher in the committed subjects compared to the

control ones.

Commitment may influence choices even in a risky context. Moriarty (1975)

compared the reaction of two groups of people who saw a thief steal a radio on a

beach. Despite the risk associated with following a thief, people who had agreed

with the owner of the radio to ‘‘watch his things’’ were much more likely to run after

the thief than those who had not been asked to watch the radio.

Finally, commitment has also been applied to food consumption. Brehm (1960)

invited a group of students to eat some vegetables which he knew they did not like.

After eating the vegetables, the students reported a significantly more positive

attitude towards the disliked vegetables.

The formation of commitment depends on many different factors. For example,

increasing the level of publicness of an act fosters the creation of commitment.

Whenever people publicly take a stance, they also feel a need to maintain their

initial choice in order to appear consistent (Cialdini 1993). If people have perceived

the initial choice as their own, they feel more compelled to be coherent with their

acts (Kiesler and Sakumura 1966; Joule and Azdia 2003). Also the importance and

the number of the acts performed by the person influence the level of commitment;

but even trivial choices performed only once may create a commitment, as shown

by the previous examples.

Although the study of commitment has attracted the attention of many scholars

since the 1960s, there is no common understanding on the meaning and nature of

commitment. A first perspective (Kiesler and Sakumura 1966) sees commitment as

a consequence of a real change in subjects’ attitudes. This interpretation has its roots

in Festinger’s (1957) Cognitive Dissonance theory. According to this theory, when

people feel a contrast between opposing ‘‘cognitions’’, they experience a discomfort

associated with this inconsistency (a ‘‘psychological dissonance’’). In the attempt to

resolve this inconsistency, people change their previous belief system. For example,

if a person agrees to publicly state an opinion in which they do not believe, then

they will change their personal opinion in order to match their attitude with their

public statement. Hence, the commitment can generate a real change in attitude:

Consumer decision in the context of a food hazard 61

123

individuals who are convinced that they are acting in ways inconsistent with their

attitudes will change them in order to achieve coherence between actions and

beliefs.

An alternative perspective, described by Cialdini et al. (1978), claims that

commitment is an expression of social influence, a form of consistency withprevious decisions that does not necessarily imply a shift in attitude. In this regard,

Cialdini et al. (1978) describe the commitment mechanism used in a selling

technique: the low-ball technique employed by used-car salesmen. First the

salesman proposes a very good deal, for example a large discount. Then, after the

customer has decided to buy the car, the salesman uses an excuse (e.g. an

unmentioned expensive optional) to raise the price. The customer has already

decided to buy the car, and even if one of the interesting features of the deal is now

lacking, the customer is committed to his decision and buys the car anyway.

According to this second perspective, commitment is an expression of social

influence, a consistency with previous decisions that does not necessarily imply an

attitude shift.

The main aim of this paper is to show how commitment can influence choices

about food consumption in a risky context.

We expect that people who decide to eat a particular food product on a given

occasion will show a greater propensity to buy and consume the same product again

even during a food crisis, compared to people who have not made this initial choice.

In particular, a committed consumer may show a tendency towards an ‘escalation of

commitment’ (performing more demanding choices in line with the initial decision)

and may maintain his/her initial stance even when s/he is aware of a potential hazard

related to his/her subsequent choice.

The secondary aim of the paper is to investigate the effect of commitment on two

related variables: the attitude towards food products, and the level of trust in the

various actors in the supply chain of these products. These two variables may be

important predictors of the intention to buy a product in a context of risk. If

commitment to a product improves trust in the various economic actors that make

up a food supply chain, then this increased trust may influence the intention to buy a

specific food product. On this argument, commitment may modify the attitude

towards the food product and the intention to purchase it. However, the relationship

between commitment and attitude is not entirely clear, because different theories put

forward opposite views on the topic. These different theories will be discussed in

the following sections. Nor is the relationship between commitment and trust clear,

so that we do not make specific claims in regard to the effect of commitment on

attitude and trust—the study is mainly exploratory in respect of these two variables.

1.1 The emotional and instrumental components of attitude

For Ajzen (2001), attitude is a concise evaluation of a psychological object, e.g.

behaviour or a specific event. This evaluation may be expressed in very broad terms,

which are usually enclosed within positive versus negative extremes. An attitude

brings together different qualities, such as good–bad, beneficial–harmful, pleasant–

unpleasant (Ajzen and Fishbein 2000; Eagley and Chaiken 1993). Many studies

62 M. Graffeo et al.

123

have been carried out to gain better understanding of the components of attitude,

and there is broad consensus on the distinction between the cognitive versus

emotional attitude. The prevalence of certain kind of information may give the

attitude a mainly emotional character (e.g. ‘‘giving blood scares me’’) or a cognitive

character (e.g. ‘‘abortion is dangerous’’) (Huskinson and Haddock 2004). Attitude,

together with other definitions, was used in the theory of planned behaviour (Ajzen

1991) to describe and predict the forming of intentions of individuals and their

actions. In Kahneman et al. (1999), attitude is used to explain how jurors establish

the amount of punitive damages to award.

The evaluation of attitude has also been applied to the consumption of food. For

example, Frewer et al. (1996) describe the case of cheese production with new

technologies (genetic modification of the micro-organisms necessary for the

production of cheese). The public may not be enthusiastic about a product that is

seen to be ‘unnatural’, but if the producer links positive information with the

product, e.g. a lower price, a positive attitude may be created which makes the

product more attractive.

Finally, attitude has been used to predict how willing an individual is to follow a

specific diet. A more positive attitude towards healthy foods increases the

probability of following a diet based on such foods (Tepper et al. 1997). Cook

et al. (2002) showed that the attitude towards genetically modified food is a reliable

predictor of the intention to purchase it.

Overall, attitude is considered to be a key element in the decision process, and a

change in the attitude towards a food product may predict future purchase decisions.

1.2 Trust

Trust is present in personal relationships in different contexts, and it can manifest

itself in many ways. The study of trust has proved to be rather complex and there is

a general difficulty in identifying its essential features. A thorough definition is

needed to deal with this problem: according to Mayer et al. (1995), trust is ‘‘the

willingness of a party to be vulnerable to the actions of another party [trustee] based

on the expectation that the other will perform a particular action important to the

trustor, irrespective of the ability to monitor or control the other party’’. Mayer et al.

(1995) consider trust to be the sum of three distinct components: the level of trust in

the ability of the trustee (competence), the opinion about how much the trustee is

willing to help the trustor (benevolence), and how much trustor and trustee share the

same moral values (values sharing). In our study, trust in the actors in the food

supply chain will be investigated along these dimensions.

There is also a link between perception of risk and trust. Various studies

(Kimenju and De Groote 2008; Mazzocchi et al. 2008; Siegrist 2000; Siegrist and

Cvetkovich 2000; Siegrist et al. 2007) show that risk perception is directly affected

by trust in the information provided by the food chain actors, by experts and by

alternative sources such as consumer, environmental and animal welfare organi-

sations. For this reason we investigated the relationship between intention to

purchase and trust in three different actors in the food supply chain: breeders,

suppliers, and control authorities.

Consumer decision in the context of a food hazard 63

123

1.3 Goal of the experiment

The goal of the experiment reported here was to determine whether a small

commitment to a particular food product is enough to increase consumers’

willingness to buy it in a condition of food hazard. Moreover, we were interested in

how commitment impacts on consumers’ trust in the actors in the food production

chain, and on their attitude towards food consumption.

The experiment tested this hypothesis on two different products: salmon and

chicken. We chose salmon and chicken because we wanted to observe the effect of

commitment on two different categories of food products. In particular, salmon and

chicken have very different price levels in Italy, and different frequencies of

consumption, with salmon but not chicken being considered a luxury item. At the

same time, in the past few years both products have been subject to serious cases of

dioxin poisoning in Europe, so that it was possible to apply the same ‘food scare’ to

them.1 Both events had major economic consequences, but the chicken crisis

received much greater media coverage and its consequences lasted longer than did

the effects of the salmon fishing ban.

2 Method

2.1 Participants

One hundred and sixty adults were asked to participate voluntarily in the study. All

participants lived in Trento (Italy) and they were contacted in supermarkets or

through advertisements. The interviews were held in two supermarkets, one in the

city center and the other in the suburbs of Trento. Participants received a fee of €10

in cash. The mean age was 36 years old (SD 14). Forty-eight percent of the

participants were males and 52% were females. Fifty-four percent of the subjects in

the sample were single, 40% were married, and 7% were separated, divorced or

widowed. Eleven percent of the participants had completed lower-secondary school,

59% had completed upper-secondary school, and 30% had university degrees.

2.2 Procedure and Material

Each participant was asked to read and fill in a questionnaire. A general introduction

described the study as a general investigation into consumer preferences, and

assured the participants that their answers would remain anonymous and would be

used only for scientific purposes.

The participants were randomly assigned to one of three groups (group

‘‘commitment to salmon’’ N = 50, group ‘‘commitment to chicken’’ N = 54,

control group N = 56). The procedure was composed of four phases (see Table 1).

1 A notorious case of dioxin contamination in chicken was reported in Belgium in 1999 (‘‘La

Repubblica’’, 23/07/1999). Salmon fishing was halted in Denmark owing to high levels of dioxin

concentration (‘‘Corriere della Sera’’, 01/04/2004).

64 M. Graffeo et al.

123

2.2.1 Phase 1

In the first phase, participants in Group 1 and 2 were presented with an initial

question that could commit them, respectively, to the consumption of chicken or

salmon. Group 3 served as a control, and no commitment question was put to it. The

committing questions for Groups 1 and 2 were respectively:

Imagine that your usual fishmonger [butcher] offers you a salmon fillet

[chicken] for free to celebrate the refurbishment of the store. What do you do?

Participants were asked to choose between the two options:

‘‘You eat the salmon fillet’’ [chicken] vs. ‘‘You do not eat the salmon fillet

[chicken]’’.

The free offering of a product as a form of manipulation of commitment has been

used to ensure a high rate of acceptance, so that a high percentage of participants

may feel commitment to salmon [chicken] consumption. Note that the question was

framed in a form designed to focus the participants’ attention (and consequently

their possible commitment) on the action of eating the specific product offered.

2.2.2 Phase 2

In the second phase, participants in all the groups were presented with a food hazard

scenario describing the dangers of dioxin. Group 3 began the procedure at this point.

The food hazard scenario gave them information about dioxin and its risk to the

health. The aim was to create alarm and concern about eating the two products. The

food hazard scenario read as follows:

DIOXIN: A REAL PROBLEM FOR HEALTH. A considerable threat to our

health, disappointingly very seldom detected, is the risk raised by the

consumption of food contaminated by dioxin. Dioxin is extremely toxic and it

Table 1 Description of the phases of the experiment

Phase Group 1:

commitment

on salmon

Group 2:

commitment

on chicken

Group 3:

(control)

no commitment

1 Commitment question Would you eat the free salmon

fillet?

Would you eat the free

chicken?

–

2 Food hazard scenario Description of the dioxin threat and how dioxin

can contaminate food, specifically salmon or chicken

3 Choices in a context

of food hazard

Participants answer distinct questions:

• Whether to serve salmon at a family dinner

• Whether to serve chicken at a family dinner

The order of presentation is counterbalanced

4 Final questionnaire Questionnaire on perceived trust in the various actors

in the salmon and chicken supply chains and also

on attitude towards the two products

Consumer decision in the context of a food hazard 65

123

is used especially as an additive in oils for engines and condensers. Disposing

of old machinery that has used dioxin is difficult and costly. For this reason, in

the absence of effective controls by the authorities, unscrupulous people will

continue to dump it in the environment. Once it has been abandoned in the

environment, dioxin will deposit in vegetables and forage. These products

then become fodder for a large range of breeding animals. The main risk

raised by dioxin is due to its tendency to accumulate in animal fat, so that

lower initial concentrations in the fodder increase at every processing stage,

ultimately reaching high levels of risk in breeding animals. Researchers have

demonstrated a large variety of effects on the human body. Among the organs

most at risk are the liver, the reproductive and neurological apparatus and the

immunity system. The EPA (Agency for the protection of environment) has

classified dioxin as a probable cancerous substance [Source: Review

Altroconsumo; No 152 September 2002]’’.2

2.2.3 Phase 3

In the third phase participants were reminded that in Triveneto, the region of Italy

where they live, there were past cases of salmons and chickens poisoned by dioxin.

In addition, participants were informed of the potential danger of consuming

poisoned salmon and chicken. The order of presentation of the two scaring scenarios

(salmon and chicken) was counterbalanced across participants. After the food

hazard scenario had been presented, participants were asked two questions about

their purchasing intentions in regard to both chicken and salmon consumption (the

order of presentation was balanced):

Imagine that a family dinner you have organized is scheduled for next week.

You need to think about what to buy for the dinner. You know that your

family enjoys eating salmon [chicken]. What do you do?

Participants had to choose between two options:

‘‘You buy salmon [chicken] for the dinner’’ vs. ‘‘You do not buy salmon

[chicken] for the dinner.’’

Note that participants always stated their intention to buy salmon [chicken] after the

dioxin threat description, so they were well aware of the risk involved in their

decision.

2.2.4 Phase 4

Finally, the fourth phase of the procedure was a questionnaire concerning different

dimensions of trust in the actors in the food supply chain and the attitude towards

the two products (see the Appendix A). The questions were designed to test the

2 The description of the dioxin cycle is based on actual scientific information, adapted from an article in

the journal Altroconsumo. The journal Altroconsumo is published by the consumer association of the

same name.

66 M. Graffeo et al.

123

attitude to salmon and chicken consumption and trust in the actors of the salmon and

chicken supply chain. The questions about competence, benevolence and shared

values of the actors were derived from the model of trust developed by Mayer et al.

(1995), from other studies on trust (Mayer and Davis 1999; Selnes 1998) and from

the Eurobarometer survey 52.1.3 After the questions on trust, we measured the

attitude towards the food product (Q16). Following the semantic differential

structure, the attitude on the food product was investigated by using a set of eighteen

bipolar scales adapted from Osgood et al. (1957) and Maio and Olson (1998).

Finally, socio-demographic data were collected.

This experimental design enabled us to check for the effect of commitment on

purchase intention, trust and attitude judgments. As reported in the literature on

commitment (see Cialdini 1993, for a review), people are more likely to take a

specific course of action when they are previously committed to a similar behavior.

The research hypothesis was therefore that people will be more likely to purchase a

food product in the context of a food hazard once they have committed to it.

3 Results

The results of Phase 1 show that most of the people agreed to eat the salmon (90%)

and the chicken (89%) when they were offered for free. Thus, the commitment

manipulation proved to be successful.

We now consider the effect of commitment on the purchase intention and the

trust-attitude judgments in the context of a food hazard.

3.1 The effect of commitment on the purchase intention

Tables 2 and 3 show the percentage of people willing to buy salmon [chicken] after

being exposed to food hazard information. Groups 1 and 2 (participants with

commitment to the product) are compared with Group 3 (participants with no

commitment).

The percentage of people willing to buy the salmon is higher (60% vs. 30%) in

Group 1 (‘‘committed to salmon consumption’’) than in Group 3 (control: no

commitment)—Chi-square (1) = 9.41, p \ 0.01. In particular, the odds ratio

between people who buy salmon and people who do not is three times higher in the

group with commitment to salmon, compared with the group without commitment.

The difference between Group 2 (‘‘committed to chicken consumption’’) and Group

3 goes in the same direction but is not statistically significant.

To control for the effect of commitment on the purchase intention, we conducted

another analysis in which trust, attitude and socio-demographic variables were also

considered. This analysis shows the relative impact of the commitment on the other

variables. Two logit regressions were performed: one on the intention to buy

salmon; the other on the intention to buy chicken. The variables simultaneously

3 Eurobarometer report number 52.1 ‘‘The Europeans and biotechnology’’, from the Public Opinion

Analysis unit of the European Commission, published on 15th March, 2000.

Consumer decision in the context of a food hazard 67

123

inserted in the logit regression equations were: status, education, age, sex, trust in

the food chain, attitude towards the food product, and previous commitment to the

food product. The categorical variables were coded in the following way: ‘‘status’’

(single versus married versus separated/widow), ‘‘education’’ (lower-secondary

versus upper-secondary school versus university degree), ‘‘gender’’ (male versus

female) and ‘‘commitment’’ (commitment to the food product versus absence of

commitment). The other variables were the ‘‘age’’ of the respondent, the ‘‘trust in

the food chain’’ (the average trust judgment, from Q1 to Q15, across the three main

actors in the food chain), and the ‘‘attitude to the food product’’ (the average attitude

judgment across the 18 bipolar scales).

The results of the logit regression on the intention to buy the salmon showed that

‘‘commitment’’ (Wald Chi-square (1) = 4.408, p \ 0.05, B = 0.852) and ‘‘atti-

tude’’ (Wald Chi-square (1) = 16.034, p \ 0.01, B = -1.033) were the statistically

reliable predictors. The logit regression on the intention to buy the chicken showed

that ‘‘attitude’’ (Wald Chi-square (1) = 6.315, p \ 0.05, B = -0.665) and ‘‘age’’

(Wald Chi-square (1) = 4.881, p \ 0.05, B = -0.045) were the statistically

reliable predictors. Again the effect of commitment was reported only with the

salmon. The attitude variable affected the intention to buy both salmon and chicken.

Specifically, corresponding to a more positive attitude towards the food product was

a stronger intention to buy it in the context of a food hazard.

3.2 The effect of commitment on the attitude

As shown in the Appendix A, the attitude to salmon and chicken consumption was

measured by a set of eighteen bipolar scales (Q16). The attitude scales were

analyzed as usually done in the standard literature by submitting all scales to a

factor analysis and using the mean of the scales loading on each factor as dependent

Table 3 Decision to purchase the chicken between the two groups

Purchase decision in the

context of food hazard information

Group 2: commitment

on chicken

Group 3: (control)

no commitment

Total

Yes 28 (52%) 25 (46%) 53

No 26 30 56

54 55 109

Chi-square (1) \ 1, p = 0.50

Table 2 Decision to purchase the salmon between the two groups

Purchase decision in the

context of food hazard information

Group 1: commitment

on salmon

Group 3: (control)

no commitment

Total

Yes 30 (60%) 17 (30%) 47

No 20 39 59

50 56 106

Chi-square (1) = 9.41, p \ 0.01

68 M. Graffeo et al.

123

variables. Two factorial analyses were performed on the scales (one for salmon and

one for chicken) to extrapolate the dimensions of attitude. The extraction algorithm

used the principal components method and the matrix was rotated using Varimax

method with Kaiser Normalization. The number of factors to be extracted was not

predefined; therefore the factors extracted were those with an eigenvalue above one.

Rotation converged in five iterations for salmon and in six for chicken. The attitude

scales loaded in three components both for salmon and for chicken. The components

were rather similar in the two analyses, but some scales loaded on different

components. These differences were not levelled prior to computing a mean scale

value for each component because they described our sample’s distinctive

perception of the components of each single dimension underlying the attitude to

the two types of food. Even though the factors describing the attitude toward salmon

were not identical to those describing the attitude toward chicken we used the same

names to define the factors, because the subscales were highly similar (see

Appendix B for factor loadings). For example, the scales ‘‘Bad–Good’’; ‘‘Negative–

Positive’’; ‘‘Disagreeable–Agreeable’’; ‘‘Unpleasant–Pleasant’’ and ‘‘Harmful–Ben-

eficial’’ all load highly on the same factor (named ‘‘hedonic’’) for both products.

The results of the factor analysis confirm by and large for both products the

standard factor structure of attitude, by showing the presence of a more rational

component (we named it ‘‘instrumental’’) and a more affective component (we

called it ‘‘hedonic’’). The analysis also showed a third component that we called

‘‘moral’’. The ‘‘instrumental component’’ captures the idea that eating salmon or

chicken is convenient and opportune. The ‘‘hedonic component’’ denotes the belief

that eating the two products is pleasant and good behaviour. Finally, the ‘‘moral

component’’ represents the belief that eating salmon or chicken is right and

admirable.

A mean value of the scales loading on each component was computed. The mean

values are reported in Table 4.

3.2.1 Attitude to salmon

The effect of commitment on attitude was tested by means of two independent

MANOVAs: commitment to the product was the independent variable, and the

Table 4 Mean (and standard deviation) of the attitude scales loading on each attitude factor for salmon

and chicken consumption in the two groups

Attitude

factors

Salmon Chicken

Commitment No

commitment

Both conditions Commitment No

commitment

Both

conditions

Instrumental 0.07 (0.85) 0.03 (1.23) 0.05 (1.06) 0.14 (1.14) 0.34 (1.07) 0.24 (1.10)

Hedonic 1.03 (0.99) 0.54 (1.09) 0.77 (1.07) 0.77 (0.98) 0.96 (1.03) 0.87 (1.01)

Moral 0.45 (0.74) 0.18 (0.92) 0.30 (0.85) 0.27 (0.84) 0.28 (0.86) 0.28 (0.84)

Totals 0.59 (0.76) 0.29 (0.97) 0.43 (0.89) 0.36 (0.89) 0.49 (0.90) 0.43 (0.89)

Attitude ranged from -3 (very negative) to ?3 (very positive)

Consumer decision in the context of a food hazard 69

123

mean values of the scales loading on each component of attitude toward the product

(instrumental, hedonic and moral) were the dependent variables.

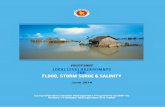

The results showed that commitment to salmon has a significant effect on the

attitude towards salmon, Hotelling’s F(3, 102) = 3.547; p = 0.017. One-way

comparisons showed that commitment significantly affects the hedonic component,

F(1, 104) = 5.703; p = 0.019, but not the moral component, F(1, 104) = 2.667;

n.s. and the instrumental component, F(1, 104) = 0.043; n.s. The effect of

commitment on the mean value of the three dimensions of attitude is shown in

Fig. 1.

3.2.2 Attitude to chicken

The effect of commitment on chicken was tested on the attitude towards chicken

consumption by means of a MANOVA with commitment as the independent

variable and the mean values of the scales loading on each component

(instrumental, hedonic and moral), as dependent variables. The results showed that

commitment to chicken does not have a significant effect on attitude, Hotelling’s

F(3, 106) = 0.705; n.s.

3.3 The effect of commitment on trust

To investigate the effect of commitment on trust two separated MANOVAs were

run, one for the actors of the salmon supply chain and one for the actors of the

chicken supply chain. Commitment was the independent variable and the level of

trust in authority, breeders and suppliers were the dependent variables. The results

showed that commitment does not have a significant effect on trust (analysis on

Fig. 1 Effect of commitment to salmon on the mean values of three dimensions of attitude towardssalmon consumption

70 M. Graffeo et al.

123

salmon: Hotelling’s F(3, 102) = 0.972; n.s. analysis on chicken: Hotelling’s F(3,

106) = 0.101; n.s).

4 General discussion

The reported findings show that previous commitment to a food product may affect

its purchase likelihood in the context of a food hazard. However, this effect seems to

be selective, given that it was reported only for one type of food, salmon, but not for

the second product, chicken.

The effect of commitment on salmon was strong, and it affected both the

likelihood of the intention to purchase and the attitude towards salmon consump-

tion. In particular, the percentage of consumers willing to buy salmon—during a

potential food hazard crisis—was 30% higher in the commitment group than in the

no commitment group. The difference between the two groups is substantial,

especially if one considers that the decline in UK beef consumption during the mad

cow crisis was about 34% (this being the difference between the consumption in

1985 and in 1996).4

Commitment was not the only statistically reliable predictor of the disposition to

buy salmon: the level of attitude towards salmon consumption also influenced the

willingness to eat salmon. In addition, commitment had an effect on the attitude

towards food consumption. For all the three attitude dimensions, consumers who

were exposed to commitment reported a more positive attitude toward salmon

consumption compared to consumers who were not, although only the hedonic

attitude dimension proved statistically reliable.

Altogether, the reported findings suggest that the effect of commitment is

mediated by a change in the attitude of the consumer, and that it does not simply

concern a desire for behavioral consistency. This finding is congruent with the

theory put forward by Kiesler and Sakumura (1966). Commitment seems to affect

the intention to eat salmon through a change in the hedonic attitude towards the

product.

The experimental manipulation of commitment did not affect the intention to

buy chicken. Two factors may explain this result. Firstly, the food crisis due to

dioxin-poisoned chicken received much wider media coverage than similar events

concerning salmon poisoning. People had already received a great deal of

information about the risks related to eating chicken and they may have been

already accustomed to this kind of threat. If this was the case, participants in the

‘‘no commitment’’ group may have discounted the alarming information as a

repetition of a previous crisis which posed low actual health risks. As a

consequence, the experimental manipulation could not exert a major impact on

their intention to buy chicken. Secondly, the participants may have perceived the

choice to eat the free offered chicken as a decision very similar to their customary

4 Data published by the UK Meat and Livestock Commission. Note the 1996 was one of the most

dramatic years of ‘‘mad cow’’ crisis and that other concomitant factors may have contributed to this

decrease.

Consumer decision in the context of a food hazard 71

123

consumption choice, since chicken is a frequently consumed food. Since the

committing action is very similar to a habitual choice, the effect of commitment

may have been weakened. In this regard, to be noted is that Joule and Azdia

(2003) proved that additional commitment actions do not always produce a further

increase of attitude.

The attitude change that we report may be explained as a reaction to the cognitive

dissonance (see Festinger 1957) created by the distance between the decision (eat

salmon or chicken in a condition of food hazard) and the initial attitude. The attitude

change may be described also through the ‘‘attribution theory’’. Attribution theory

(see for example Kelley 1973) studies how people attribute causes to various events.

In our experiment people decide whether to eat or not a food product, then they rate

their attitude toward the product. If people don’t have a precise reason for their

decision they may attribute their choice to a (previously unknown) preference

toward the product. After they have decided if they want to eat the product or not,

they may infer their preference through their choices, as they would do observing

the choice of another person (see Bem 1967).

The reported findings indicate that—under certain conditions—commitment may

be an effective marketing/public policy strategy to cope with the short term effects

of potential food crises (see Flynn et al. 2001, for a discussion on food crises). A

policy that seeks to minimize the negative impact due to the spread of information

on food hazards may be based on the creation of a commitment to the food products

and on strengthening the positive consumption experience. For example, people

who eat food products during a public event probably perceive their decision as

being a public act of their own choice, developing a strong sense of commitment. If

this is the case, they will probably show a more positive attitude towards the product

and a stronger intention to buy the product again. In addition, customers committed

to the consumption of a product are more resistant to the discouraging effect of

information about a food hazard, and they tend to maintain their usual consumption

behaviour even during a food crisis. For these reasons, we believe that commitment

may be an effective strategy to counter the depressing short term effect of a food

crisis, especially for products that generate a strong hedonic attitude (e.g. a salmon

fillet).5

Acknowledgments This research was supported by the European Commission, Quality of Life

Programme, Key Action 1—Food, Nutrition, and Health, Research Project ‘‘Food Risk Communication

and Consumers’ Trust in the Food Supply Chain—TRUST’’ (Contract no. QLK1-CT-2002-02343).

Principal investigator of the University of Trento Unit: Prof. Nicolao Bonini. Furthermore, we would like

to thank Dr. Luigi Lombardi for his helpful comments on the various statistical analyses.

5 In an independent study we found a strong hedonic attitude for salmon and this effect was significantly

higher compared to the hedonic attitude for chicken.

72 M. Graffeo et al.

123

Appendix A: Questions on trust and attitude

(Q1) (TRUST) To what extent do you trust Italian salmon [chicken] breeders?

(1 = not at all; 5 = completely)

(Q2) (TRUST) To what extent do you trust Italian salmon [chicken] suppliers?

(1 = not at all; 5 = completely)

(Q3) (TRUST) To what extent do you trust Italian authorities in charge of fish

[meat] products safety? (1 = not at all; 5 = completely)

(Q4) (COMPETENCE) How much do you think that Italian salmon [chicken]

breeders are competent in their work? (1 = not at all; 5 = completely)

(Q5) (COMPETENCE) How much do you think that Italian salmon [chicken]

suppliers are competent in their work? (1 = not at all; 5 = completely)

(Q6) (COMPETENCE) How much do you think that Italian authorities in charge

of fish [meat] products safety are competent in their work? (1 = not at all;

5 = completely)

(Q7) (BENEVOLENCE) How much do you think that Italian salmon [chicken]

breeders are concerned about your health? (1 = not at all; 5 = completely)

(Q8) (BENEVOLENCE) How much do you think that Italian salmon [chicken]

suppliers are concerned about your health? (1 = not at all; 5 = completely)

(Q9) (BENEVOLENCE) How much do you think that Italian authorities in charge

of fish [meat] products safety are concerned about your health? (1 = not at

all; 5 = completely)

(Q10) (SHARED VALUES) How much do you think that Italian salmon

[chicken] breeders share your same values? (1 = not at all;

5 = completely)

(Q11) (SHARED VALUES) How much do you think that Italian salmon

[chicken] suppliers share your same values? (1 = not at all;

5 = completely)

(Q12) (SHARED VALUES) How much do you think that Italian authorities in

charge of fish [meat] safety share your same values? (1 = not at all;

5 = completely)

(Q13) (TRUTHFULNESS OF INFORMATION) How much do you trust Italian

salmon [chicken] breeders to tell the truth about chicken meat? (1 = not at

all; 5 = completely)

(Q14) (TRUTHFULNESS OF INFORMATION) How much do you trust Italian

salmon [chicken] suppliers to tell the truth about chicken meat? (1 = not at

all; 5 = completely)

(Q15) (TRUTHFULNESS OF INFORMATION) How much do you trust Italian

authorities in charge of fish [meat] safety to tell the truth about chicken

meat? (1 = not at all; 5 = completely)

(Q16) (ATTITUDE) Personally, do you think that salmon [chicken] consumption

is a __?__ behavior:

Consumer decision in the context of a food hazard 73

123

-3 -2 -1 0 +1 +2 +3Bad |----------|----------|----------|----------|----------|----------| Good

Negative |----------|----------|----------|----------|----------|----------| Positive

Unpleasant |----------|----------|----------|----------|----------|----------| Pleasant

Harmful |----------|----------|----------|----------|----------|----------| Beneficial

Foolish |----------|----------|----------|----------|----------|----------| Wise

Unreasonable |----------|----------|----------|----------|----------|----------| Reasonable

Risky |----------|----------|----------|----------|----------|----------| Safe

Disagreeable |----------|----------|----------|----------|----------|----------| Agreeable

Ugly |----------|----------|----------|----------|----------|----------| Nice

Boring |----------|----------|----------|----------|----------|----------| Exciting

Wrong |----------|----------|----------|----------|----------|----------| Right

Ignoble |----------|----------|----------|----------|----------|----------| Noble

Despicable |----------|----------|----------|----------|----------|----------| Admirable

Shameful |----------|----------|----------|----------|----------|----------| Laudable

Disadvantageous |----------|----------|----------|----------|----------|----------| Advantageous

Inopportune |----------|----------|----------|----------|----------|----------| Opportune

Inconvenient |----------|----------|----------|----------|----------|----------| Convenient

Useless |----------|----------|----------|----------|----------|----------| Useful

Appendix B: Factors loadings of the attitude scales for salmon and chickenconsumption

Salmon Chicken

1—MF

(26% of

variance)

2—HF

(25% of

variance)

3—IF

(18% of

variance)

1—IF

(26% of

variance)

2—MF

(25% of

variance)

3—HF

(20% of

variance)

Ignoble–noble 0.878 0.124 0.046 0.155 0.890 0.108

Despicable–admirable 0.864 0.117 0.214 0.185 0.833 0.163

Shameful–laudable 0.680 0.292 0.367 0.601 0.584 0.267

Wrong–right 0.665 0.401 0.394 0.423 0.682 0.299

Useless–useful 0.629 0.287 0.321 0.481 0.607 0.226

Boring–exciting 0.591 0.361 –0.090 0.263 0.664 0.318

Ugly–nice 0.490 0.443 0.354 0.178 0.673 0.352

74 M. Graffeo et al.

123

Appendix continued

Salmon Chicken

1—MF

(26% of

variance)

2—HF

(25% of

variance)

3—IF

(18% of

variance)

1—IF

(26% of

variance)

2—MF

(25% of

variance)

3—HF

(20% of

variance)

Bad–good 0.055 0.834 0.150 0.298 0.191 0.748

Negative–positive 0.219 0.793 0.329 0.359 0.181 0.813

Disagreeable–agreeable 0.302 0.727 0.122 0.297 0.351 0.621

Unpleasant–pleasant 0.277 0.676 0.228 0.127 0.262 0.761

Harmful–beneficial 0.413 0.617 0.360 0.532 0.200 0.660

Foolish–wise 0.521 0.592 0.340 0.608 0.459 0.390

Unreasonable–reasonable 0.478 0.548 0.421 0.712 0.402 0.352

Inconvenient–convenient 0.133 0.156 0.839 0.746 0.279 0.301

Disadvantageous–advantageous 0.083 0.242 0.836 0.715 0.355 0.344

Inopportune–opportune 0.498 0.358 0.630 0.720 0.386 0.271

Risky–safe 0.301 0.444 0.498 0.806 0.032 0.184

MF Moral factor, HF Hedonic factor, IF Instrumental factor

References

Ajzen I (1991) The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Dec 50(2):179–211

Ajzen I (2001) Nature and operation of attitudes. Annu Rev Psychol 52:27–58

Ajzen I, Fishbein M (2000) Attitudes and the attitude—behaviour relation: reasoned and automatic

processes. In: Stroebe W, Hewstone M (eds) European review of social psychology. Wiley,

Chichester, pp 1–33

Bem DJ (1967) Self-perception: an alternative interpretation of cognitive dissonance phenomena. Psychol

Rev 74(3):183–200

Brehm JW (1960) Attitudinal consequences of commitment to unpleasant behavior. J Abnorm Soc Psych

60(3):379–383

Cialdini RB (1993) Influence: science and practice, 3rd edn. HarperCollins College Publishers, New York

Cialdini RB, Bassett R, Cacioppo JT, Miller JA (1978) Low-ball procedure for producing compliance:

commitment then cost. J Pers Soc Psychol 36(5):463–476

Cook AJ, Kerr GN, Moore K (2002) Attitudes and intentions towards purchasing GM food. J Econ

Psychol 23(5):557–572

Eagley AH, Chaiken S (1993) The psychology of attitudes. Harcourt Brace, Fort Worth

Festinger L (1957) A theory of cognitive dissonance. Peterson, Oxford

Flynn J, Slovic P, Kunreuther H (2001) Risk, media and stigma: understanding public challenges to

modern science and technology. Earthscan, London

Freedman JL, Fraser SC (1966) Compliance without pressure: the foot-in-the-door technique. J Pers Soc

Psychol 4(2):195–202

Frewer LJ, Howard C, Hedderley D, Shepherd R (1996) What determines trust in information about food

related risk? Underlying psychological constructs. Risk Anal 16(4):473–486

Huskinson TLH, Haddock G (2004) Individual differences in attitude structure: variance in the chronic

reliance on affective and cognitive information. J Exp Soc Psychol 40(1):82–90

Consumer decision in the context of a food hazard 75

123

Joule RB (1987) Tobacco deprivation: the foot-in-the-door technique versus the low-ball technique. Eur J

Soc Psychol 17(3):361–365

Joule RB, Azdia T (2003) Cognitive dissonance, double forced compliance, and commitment. Eur J Soc

Psychol 33(3):565–571

Kahneman D, Ritov I, Schkade D (1999) Economic preferences or attitude expressions? An analysis of

dollar responses to public issues. J Risk Uncertain 19(1):223–235

Kelley HH (1973) The process of causal attribution. Am Psychol 28(2):107–128

Kiesler CA, Sakumura J (1966) A test of a model for commitment. J Pers Soc Psychol 3(3):349–353

Kimenju SC, De Groote H (2008) Consumer willingness to pay for genetically modified food in Kenya.

Agr Econ 38(1):35–46

Maio GR, Olson JM (1998) Attitude dissimulation and persuasion. J Exp Soc Psychol 34(2):182–201

Mayer RC, Davis JH (1999) The effect of the performance appraisal system on trust for management: a

field quasi-experiment. J Appl Psychol 84(1):123–136

Mayer RC, Davis JH, Schoorman FD (1995) An integrative model of organizational trust. Acad Manage

Rev 20(3):709–734

Mazzocchi M, Lobb A, Traill WB, Cavicchi A (2008) Food scares and trust: a European study. J Agr

Econ 59(1):2–24

Moriarty T (1975) Crime, commitment, and the responsive bystander: two field experiments. J Pers Soc

Psychol 31(2):370–376

Osgood CE, Suci GJ, Tannenbaum PH (1957) The measurement of meaning. University of Illinois Press,

Champaign

Pennings JME, Wansink B, Meulenberg MTG (2002) A note on modelling consumer reactions to a crisis:

the case of the mad cow disease. Int J Res Mark 19(1):91–100

Selnes F (1998) Antecedents and consequences of trust and satisfaction in buyer-seller relationships. Eur J

Mark 32(3–4):305–322

Siegrist M (2000) The influence of trust and perceptions of risks and benefits on the acceptance of gene

technology. Risk Anal 20(2):195–203

Siegrist M, Cvetkovich G (2000) Perception of hazards: the role of social trust and knowledge. Risk Anal

20(5):713–719

Siegrist M, Cousin M, Kastenholz H, Wiek A (2007) Public acceptance of nanotechnology foods and food

packaging: the influence of affect and trust. Appetite 49(2):459–466

Tepper BJ, Choi Y, Nayga RMJR (1997) Understanding food choice in adult men: influence of nutrition

knowledge, food beliefs and dietary restraint. Food Qual Prefer 8(4):307–317

76 M. Graffeo et al.

123