Commentary: The impact of social networking tools on political change in Egypt’s “Revolution...

Transcript of Commentary: The impact of social networking tools on political change in Egypt’s “Revolution...

Electronic Commerce Research and Applications 10 (2011) 369–374

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Electronic Commerce Research and Applications

journal homepage: www.elsevier .com/locate /ecra

Commentary

Commentary: The impact of social networking tools on political change in Egypt’s‘‘Revolution 2.0’’

Ashraf M. Attia a,⇑, Nergis Aziz a,b,1, Barry Friedman a,b,2, Mahdy F. Elhusseiny c,3

a Marketing and Management Department, School of Business, State University of New York at Oswego, Oswego, NY 13126, United Statesb Faculty of Business and Management, Suleyman Sah University, Istanbul, Turkeyc Department of Accounting and Finance, School of Business and Public Administration, California State University, Bakersfield, United States

a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t

Article history:Received 13 May 2011Received in revised form 17 May 2011Accepted 17 May 2011Available online 21 June 2011

Keywords:EgyptFacebookPolitical changeRevolutionSocial networking toolsSocial networksTwitter

1567-4223/$ - see front matter � 2011 Elsevier B.V. Adoi:10.1016/j.elerap.2011.05.003

⇑ Corresponding author. Tel.: +1 315 312 5741; faxE-mail addresses: [email protected] (A.M. A

(N. Aziz), [email protected] (B. Friedman),Elhusseiny).

1 Tel.: +1 315 395 0266.2 Tel.: +1 315 312 6381.3 Tel.: +1 661 654 3480; fax: +1 661 654 6697.

Social networking is a new driving force that has a significant global impact on political change. Fewresearch studies have been published on the impact of social networking related to political change. Thiscommentary discusses the impacts of social networking tools on the recent political changes in the eigh-teen-day Egyptian ‘‘Revolution 2.0’’ of 2011. We discuss a number of factors related to social networkingthat predisposed the people of Egypt to rise up in a revolt that stunned many observers, given its speedand dramatic outcome. Social network-related factors appear to have had a positive impact on Egyptians’attitudes toward social change, which, in turn, supported their individual and aggregate behavior, leadingto the revolution.

� 2011 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

Social networking now seems to be impacting political and so-cial life across the globe. Social networks have affected politicalelections and induced social changes in the United States and Can-ada (Cook 2010), Iran (Marandi et al. 2010), Pakistan (Shaheen2008), China (Guobin 2010), and Malaysia (Smeltzer and Keddy2010). In the first few months of 2011, Facebook and Twitterplayed a prominent role in the unrest, uprisings and revolutionsin Tunisia, Egypt, Libya, Yemen, Syria, Algeria, and Bahrain. Theimpacts of social networking tools, such as Facebook, Twitter,YouTube and others in social and political environments of coun-tries, are even more interestingly exemplified in Egypt’s recent‘‘Revolution 2.0.’’

According to Ho (2011), the Egyptian revolution made othergovernments consider the appropriateness of censoring social net-works. For example, the Chinese government blocked access to

ll rights reserved.

: +1 315 312 5440.ttia), [email protected]@csub.edu (M.F.

searches for the word ‘‘Egypt’’ on Internet sites in China. TheChinese government apparently feared that the Egyptian protestwould inspire unrest in China. Hodge (2009), however, stated thatin Moldova in southeastern Europe, government Internet censor-ship did not stop the protests, but magnified its effects.

Given the newness and significant impacts of social networkingtools on recent global political changes, there is little research thatdocuments and explain how they support political change, includ-ing uprisings and revolutions. We will discuss the impact of socialnetwork tools on political changes in the recent Egyptianrevolution.

First though, we will offer some insights into Egypt’s political,economic, geographic, religious, and technological infrastructure.We also will discuss the chronology of events that took place dur-ing and after the eighteen-day Egyptian revolution, stressing therole of social networking factors that appear to have predisposedEgypt to the dramatic and transformational events that itexperienced.

2. Egypt’s ‘‘Revolution 2.0’’

To explore the impact of social networks on political change inEgypt’s revolution, a brief perspective of Egypt’s geographic, politi-cal, technological infrastructure is offered. Then we will discussthe nature and background of the Egyptian revolution itself.

370 A.M. Attia et al. / Electronic Commerce Research and Applications 10 (2011) 369–374

2.1. Background on Egypt as a Nation

Egypt has a strategic geopolitical location and is a major eco-nomic power in both Africa and the Arab world (Economy Watch2011). Egypt borders are on the Mediterranean Sea to the north,Libya to the west, the Gaza Strip to the east, and Sudan to thesouth. It has an area of one million square kilometers and a coast-line of 2450 km (Encyclopedia of the Nations 2011). Egypt’s capitalcity, Cairo, is located in the north of the country. It is the 30th larg-est country in the world, with a population of 82 million, mostlyalong the Nile basin. The Egyptian population is young, with amedian age of 24 years. The official language is Arabic, althoughother languages are used, including English and French. The liter-acy and unemployment rates are 71% and 9.7%, respectively. About20% of the population is below the poverty line (Central Intelli-gence Agency 2011). Egypt’s economy is largely dependent on pet-rochemical exports to European nations. The country has traderelations with African nations, the Middle East countries and themembers of the European Union (Economy Watch 2011).

Egypt has long been the driving force for political, economic, reli-gious and social development in the Arab World. Egypt is the firstArab nation to sign a peace treaty with Israel. With its Al-Azhar,the oldest and most prestigious Islamic University in the world,Egypt is in the center of Islamic intellectual thought and learning.Egypt also is an arbiter of peace and force of moderation in the Arabworld and embodies the ideals and values of moderate Islam, reli-gious tolerance and heritage, and cultural diversity (Shokry 2009).

Egypt has been trying to accelerate its technological progress byinvesting in technological parks. Egypt aims to lessen its depen-dence on oil exports and reduce poverty. For example, Egypt’s SmartVillage is starting to attract foreign entrepreneurs and executives toset up their own companies (Al-Shobakky 2007). Microsoft, Oracle,and Hewlett–Packard are among about 120 technology firms thatoperate in Egypt’s Smart Village high-tech park. Egypt has developedan important IT outsourcing business with young, well educated,high-tech savvy and English-speaking population.

Egypt does not rank high among nations with respect to worldgovernance indicators (Kaufman et al. 2008, 2010; World Bank2009). The governance indicators aggregate the views governancequality provided by citizens and expert survey respondents. Egyptranks in the 23rd percentile on voice and accountability, definedthe extent to which a country’s citizens are able to select their gov-ernment, have freedom of speech and association. Egypt ranks inthe 25th percentile in political stability, 40th percentile in govern-ment effectiveness, 48th percentile in regulatory quality and 30thpercentile in control of corruption.

Regarding national cultural identity (Hofstede 2001), religionplays a significant role in everyday life. Large power distance ispredominant in Egypt, which indicates that differences in powerare expected and tolerated among leaders and followers. Egypt isalso ranked high in uncertainty avoidance, indicating that strictrules and procedures dictate behavior in an effort to reduce uncer-tainty. It is not surprising, therefore, that the totalitarian regimeand government of President Hosni Mubarak was kept in powerand used strict laws to control its citizens for so long a time period.Egypt scores very low on individualism, indicating the strong col-lectivist national orientation. The combination of a collectivistsociety long repressed may be fertile ground for political revolu-tion and change.

2.2. Egypt’s ‘‘Revolution 2.0’’: Background and impact of socialnetworks

The Egyptian revolution gained momentum as a result of severalpolitical and social factors. High-level of corruption, bureaucraticlawlessness, high rates of unemployment, and violations of human

rights are the likely precedents. Egypt has high levels of corruption,little voice attributable to its citizen in the country’s affairs, andperceived government ineffectiveness (World Bank 2009). How-ever, Egyptians have lived with these problems for many years. Pa-tience is a cultural feature of Middle Eastern people, making itdifficult for them to mount sufficient social indignation to supportsignificant change and rebellion against power (Yenikeev 2011). In-stead, it was the frustration and anger of young people who wereforced to be apolitical and apathetic for a long period of time thatfinally welled up into widespread social dissent (Daragahi 2011).

Early demonstrations that occurred in the streets of Cairo wererelated to Israel’s December 2008 strike and aggression againstPalestinians in the Gaza Strip. Within hours of that attack, morethan 2000 people went out to the streets and protested. Such pro-tests in Arab cities were not new; however, the protesters cried outwith anger directly at the government of President Mubarak. Egyp-tians protested their government’s diplomatic relationships withIsrael, exports of natural gas to Israel, and limits on movement atEgypt’s border with Gaza. Young people also expressed their angerusing a new venue: social networks, including Facebook (Shapiro2009).

The roots of revolution came from past demonstrations and arerelated to the usage of social networks. Facebook, which is thethird most visited website in Egypt after Google and Yahoo, playedan important role. There were 800,000 users in Egypt in 2009. Lim-ited freedoms of speech and meetings made Facebook a tool ofchoice for Egyptians, especially the younger generation, to freelycommunicate with each other and form groups to oppose Muba-rak’s totalitarian regime and government (Shapiro 2009). Egyptwitnessed a clash of generations between state power and its olderand younger citizens.

January 25, 2011 marks the date when the power of social net-works facilitated the overthrow of the Mubarak dictatorship. Ittook only about 18 days. Facebook executives deny the role of theirsocial network tools in the revolution in Egypt, but it is obviousthat it had a key role in the mix (Kang and Shapira 2011). A chro-nology of the events associated with Egypt’s revolution is pre-sented in Table 1.

Even after the Internet blackout in Egypt, the youth continuedto demonstrate and protest, and their numbers increased. Egyp-tians managed to have their voices be heard through advancedtechnical workarounds and old traditional technologies, includingword-of-mouth and phones (Muscara 2011). President Mubarakwas forced to step down because he did not act in a way that sat-isfied his constituents. After that, the major demand of the revolu-tion was achieved and as demonstrated in Table 2, a high level ofcollaboration between the Egyptian revolutionary leaders and theEgyptian Army Supreme Council occurred as a means to build onthe demands and the gains of the revolution.

People expressed a negative attitude toward the government ofMubarak because of a high level of social distrust. Mortimore(2003) suggests that the attitudes of people can be negative if theydistrust disappointment by failing to vote. Furthermore, the publicis more prone to believe the worst about politicians.

3. The impact of social networking on the political environment

Social networking has been defined as the ‘‘use of specific typesof websites focused on creation and growth of online social net-works which allow users to interact’’ (Coyle and Vaugh 2008,p. 13). There is little consensus on the definition of social network-ing and how to measure the effectiveness of these sites (Hartmannet al. 2008). Social networks supply people with opportunities tobe part of international communities that enable them to commu-nicate their shared thoughts, information, and recommendations.

Table 1A chronology of impact events in the eighteen day 2011 Egypt Revolution 2.0.

Date Action/Event Impact

January 14 The Tunisian Revolutionsucceeded in forcing theTunisian President to flee thecountry, after four weeks ofmassive demonstrations

The Egyptian people’spolitical passion was ignitedby the success of the TunisianRevolution, which wasstrongly facilitated by socialnetworks

January14–24

Calls for Egyptiandemonstrations spreadquickly on Facebook andTwitter

Over 90,000 Facebooksubscribers confirmed theirparticipation in the January25 demonstration

January 25(Day ofRevolt)

Tens of thousands ofEgyptians protested in thestreets of Cairo, and in othercities all over Egypt

The large turnout led to a callon social networks for othermassive demonstrationsacross Egypt on January 28

January26–27

The Egyptian governmentdecided to block Facebook,and cut Internet and cellphone communications forsix days beginning on this day

The Egyptian government’sactions had adverse effects ondemonstrators, leading to adecision on their part todemonstrate day and night inCairo’s Tahrir Square and allover Egypt

January 28(FridayofAnger)

1–2 million people began toexpress their anger, bydemonstrating in many placesacross Egypt

The demonstrations turnedthe uprising into ‘‘Revolution2.0’’ in Egypt. Mubarakaddressed the nation andpromised to form a newgovernment

February 1 Mubarak again addressed thenation, promising not to runfor president again, but healso announced that he wouldstay in power until September

A large number of Egyptianssympathize

February 2(Battleof theCamel)

Also known as BloodyWednesday, on this day pro-government forces brutallybeat and killed many Egyptiandemonstrators

The Egyptian demonstrationsintensified, with 4–5 millionpeople protesting throughoutEgypt

February 4 The demonstrations grew toinclude 20 million peoplecross Egypt

As the size of thedemonstrations escalated, thepeople put forth moredemands

February10

Mubarak refused to stepdown, but delegated hisduties to his vice president

The demonstratorssurrounded the parliament,ministries, and national TV,and vowed to surroundMubarak palaces andresidences

February11

Mubarak stepped down fromthe presidency, and theEgyptian Army SupremeCouncil took over

The major objectives ofEgypt’s ‘‘Revolution 2.0’’ wereachieved by this day

February11–18

Egyptians celebrate thesuccess of their revolution

A high level of collaborationoccurred between theEgyptian revolutionaryleaders and the EgyptianArmy Supreme Council. Thelatter was in charge, andacted as positive broker andguarantor of the Egyptianrevolution’s gains

Table 2Post-Egyptian ‘‘Revolution 2.0’’ remedial political actions and collaboration.

Egypt’s revolution leaders Egypt’s army supreme council

After the revolution, therevolutionary leaderssubsequently encouragedpeaceful demonstrations thatsought to accomplish two keygoals:� Safeguard the accomplishments

of the revolution; and� Reinforce the revolution

demands to be met by positivepressure

Positive actions and decisions weremade by the Egyptian Army SupremeCouncil to meet the demands of therevolution and its leaders to:� Dissolve the parliament, the advi-

sory and local councils and theMubarak-appointed members ofgovernment� Appoint a prime minister, who

appoints a government� Form a committee to revise the

articles of the constitution� Conduct a referendum on the

revised constitution (which hada referendum turnout of 45%)� Dissolve the oppressive national

security police� Free most of the country’s politi-

cal prisoners� Arrest Mubarak, his family, and

members of regime, and put theminto trial� Dissolve the ruling political party� Change most of Egypt’s regional

governors.A number of anticipated changeswere to follow:� Cancellation of the country’s

emergency laws� New parliamentary, advisory, and

local council elections� An election for a new president;

and� Development and ratification of a

new constitution

A.M. Attia et al. / Electronic Commerce Research and Applications 10 (2011) 369–374 371

Web 2.0 technologies are a collection of social media by whichpeople actively form, organize, edit, integrate, and rate Web con-tent. Social networks help people interact by linking blogs, wikis,social networking hubs (Facebook, MySpace), web-based commu-nication modes (chatting rooms), photo-sharing (Flickr), videocasting and sharing (YouTube), audio-sharing (podcasts), virtualworlds, microblogs (Twitter) and others. These technologies sup-port group interaction (Cooke and Buckley 2008).

Hundreds of millions of people, mostly the young and middle-aged population, use different social network tools. Specifically,Facebook alone has more than 500 million subscribers, which rep-

resents the third largest country in terms of population, behindChina and India. The uniqueness and power of Facebook arisesfrom its ability to provide users with an opportunity to tell his orher own story (Vericat 2010).

Political leaders and parties recently began to use social net-working to achieve political objectives. For example, all of the can-didates in the 2008 United States presidential election aggressivelyused information and communication technologies, such asFacebook, MySpace, YouTube and others. The major objectiveswere: (1) to involve voters in ongoing two way communication;(2) to enhance interactions with the campaign; (3) to encouragevoters to form online political societies among themselves; (4) tomake financial contributions to the campaigns (Robertson et al.2010); and (5) to provide a lack of third parties by external inter-ests with a decentralized core (Wills and Reeves 2009).

Iranians went to the voting polls in the 2009 presidential elec-tion. Their voting decision was whether to keep the Iranian presi-dent in power for an additional four years or to choose a liberalreformist. The Iranian reform movement, the majority of whosemembers were young people under 30, attempted to unite behindone candidate, whose campaign was fueled through the use of hightechnology campaign tactics (Bazzi 2009). During the campaign,mobile phone communications were interrupted and access toFacebook was temporary blocked across the country. Such censor-ship was utilized because contenders participating in election wereusing Facebook in their campaigns.

Both the 2008 American and 2009 Iranian presidential electionsshowed the use of mobile marketing to be a strong vehicle for gov-ernments and political parties to mobilize their supporters (Cook2010). Such tools as Facebook, MySpace, Twitter, and YouTubeprovided individuals with a means to become part of the largerpolitical process (Levy 2008). Recently, academicians have startedto conduct studies related to social networking tools, because on-

372 A.M. Attia et al. / Electronic Commerce Research and Applications 10 (2011) 369–374

line social networking seems to affect every aspect of contempo-rary human life. The huge user bases, the important amounts ofdata they provide, and their growing impacts on social and politicallife attracted the attention of social and political researchers (Willsand Reeves 2009). Just a little is known about psychosocial vari-ables that cause people use social networking, however (Pellingand White 2009).

In the last decade, technological advances that were aggres-sively employed to bring drastic political and social change eitherfully or partially succeeded. Several examples of successful politi-cal and social change are noteworthy. For example, the 2004 dem-onstrations organized by text messaging led to the quick ouster ofSpanish Prime Minister, José María Aznar, who had inaccuratelyblamed the Madrid transit bombings on Basque separatists.Another example is the Communist Party, which lost power inMoldova in 2009, when massive protests were coordinated in partthrough text messages, Facebook, and Twitter, in response to per-ceptions of election fraud. A third example is the Boston Globe’s2002 global exposure of sexual abuse in the Catholic Church, whichwent viral online in a matter of hours, and resulted in lawsuitsagainst the church based on charges that it was a safe harbor forchild rapists.

There are examples of partial successes or full-failure tothough. For example, street protests arranged by e-mail failedto oust the president of Belarus in March 2006, and actually madethe president and the government more determined than ever tocontrol social media. Another example occurred during the June2009 Green Movement uprising in Iran. Activists used every pos-sible technological tool to coordinate protests against the mis-counting of votes for Mir-Hossein Mousavi, a reformistpolitician who served as the last prime minister of Iran in the1980s. His efforts to lead the Iranian reform movement were ulti-mately brought to heel by a violent crackdown the conservativegovernment. A third example was the Red Shirt Uprising in Thai-land in 2010, which followed a similar but quicker path. Protest-ers who were savvy with social media occupied downtownBangkok until the Thai government dispersed them, killing doz-ens in the process (Shirky 2011).

Social network tools such as Facebook, Twitter and other mediavehicles play a very important role in social life because theyengender a lot of involvement from consumers and young people.According to the new Media Metrics ranking, consumers are highlyattached to Google search, AOL email, YouTube, Facebook, Ama-zon.com and other social networking tools than they are to tradi-tional media properties, such as television shows, magazines andother more static websites (Steinberg and Forget 2010). In a newAd Age/Ipsos Observer survey of the digital media habits of people,Facebook was the clear winner. 41% of respondents said theywanted to receive communications from marketers on Facebook– more than double any other digital platform. Meanwhile, onein three others responded that Facebook was their preferred plat-form (Carmichael 2011). In addition, when consumers were asked

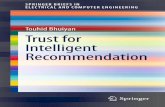

Fig. 1. Social network variables th

via which platforms they want to receive communication frommarketers in general, 41% said Facebook, 18% Twitter, 17%MySpace, 13% others, and 48% none.

4. Facilitating variables for political change

Research shows that a match between people’s interests andthose projected by a website should result in a more powerful tie be-tween the website and the user. Credibility also plays a role ininvolvement, and website credibility seems to be activated by thestrength of ties between it and other sites that are known andtrusted (Brown et al. 2007). We evaluated the social network litera-ture and found that a number of different variables affect people’sbehaviors. They include trust (Lai and Turban 2008, McKnight andChervany 2002), relationships (Coyle and Vaugh 2008, Ellison et al.2007), loyalty (Shen et al. 2010, Lin 2008, Casalo et al. 2010), value(Dholakia et al. 2004, McKenna and Bargh 1999) and word-of-mouth(Bickart and Schindler 2001, Smith et al. 2007) affect people’s behav-iors. Perceptions of trust, relationships, loyalty and value also arelikely to affect individual use of social network tools, attitude forma-tion, and intended and actual behavior toward political change. Tocharacterize this argument, we present Fig. 1.

In the case of the revolution in Egypt, people perceived thatthey could trust the words of others who were calling for the upris-ing. Trust reduces social ambiguity (Gefen and Straub 2004) andpeople’s suspicions related to interactions and relationships(Grabner-Krauter 2002, 2010). Information provided by peers insocial networks is often viewed as credible and trustworthy also(Gil-Or 2010, Smith et al. 2007).

Word-of-mouth communication becomes much more powerfulin a country when its citizens lose their trust in the official state-ments and pronouncements of the government. During the Egyp-tian revolution, users of online social networks such as Facebookand Twitter stopped believing the government. Instead, theytrusted the messages and information they obtained from thesetools, and their widespread popularity reinforced these sentiments.

Users of social networks in Egypt also developed relationshipswith each other in their struggle for change. Research has shownthat people, especially young people, use social networking toolsto maintain existing relationships (Coyle and Vaugh 2008, Ellisonet al. 2007). This often results in increased interpersonal discussionthat fosters, in turn, civic participation and political activism(Zhang et al. 2010). This was the case in Egypt. Cardon et al.(2009) investigated online and offline social ties of social networkwebsite users. They found that social network users in Egypt, a col-lectivist society, had significant social ties with people whom theyhad never met in person. People can have relationships, eventhough they do not have an opportunity to physically meet eachother, and the prevalence of this is related to culturalcharacteristics.

Perceived relationships also affected the preferences ofEgyptians. The need for change led them to develop committed

at facilitate political change.

A.M. Attia et al. / Electronic Commerce Research and Applications 10 (2011) 369–374 373

partnerships that led, in turn, to widespread perceptions of loyaltyand commitment related to the idea of political change. Accordingto Harridge-March and Quinton (2009), social network users maydevelop loyalty among themselves, related to the dimensions oftheir attitudes and behaviors. In addition, social networking toolswere perceived as a resource of value because they provided infor-mation for users. Stephen and Toubia (2010) have argued that so-cial commerce provides economic value for market-owningcompanies and sellers in the marketplace. In the case of the revo-lution in Egypt, the people aggressively used the available socialnetworking tools to understand what was going on in the country,and to support each other in their efforts to bring political change.

When people communicate through social networking tools,they are likely to perceive the suggestions of people whom theyknow as credible and trustworthy (Harridge-March and Quinton2009). Social network users also develop relationships with thosethat have similar interests rather easily (Bickart and Schindler2001), and they show loyalty to the networks they choose to use(Harridge-March and Quinton 2009).

During the Egyptian revolution, people also changed their atti-tudes easily because they were not loyal to the Mubarak govern-ment. If they had been loyal, their attitudes would not havechanged, and there would not have been any uprising at all. Butnew attitudes, confidence, and persistence developed in Egypt dur-ing this time. The result was that people’s attitude toward politicalchange were strong enough to overcome censorship by the govern-ment of the Internet until Mubarak resigned.

Behavioral intentions are indicators that signal whether citizenswill stay with or defect from the government, which means thatbehavioral intention can be favorable or unfavorable (Zeithamlet al. 1996). If Mubarak’s government had provided outstandingservices, its citizens would have favorable intention towards thegovernment. However, Egyptians’ views were suppressed, theywere removed from the political process, and they were not receiv-ing good services. As a result, they held unfavorable behavioralintentions toward the government, which resulted in an uprisingagainst the Mubarak regime. The favorable behavioral intentionof the people toward political change affected their behavior.

5. Conclusion

In the case of Egypt’s ‘‘Revolution 2.0,’’ social networking toolusers showed trust, developed and maintained strong relation-ships, expressed loyalty, obtained value and aggressively usedword-of-mouth to further their cause. All these social networkvariables facilitated the formation of a positive attitude towardspolitical change among Egyptian youth, which gave them positivefeelings toward participating in the uprising and revolting. This ledto positive behavioral intentions to bring change to the country,which subsequently supporting changes in the political conditionsin the country necessary to create and sustain individual and col-lective uprising and revolt.

It was remarkable that young people formed positive attitudestoward political change on the basis of the information obtainedfrom social networks. The communication that occurred showedthat people were giving one another social support. Even censor-ship and controls put on Internet-based communications in thecountry did not prevent people from continuing to communicatewith each other, which made it possible for them to rise up andrevolt.

The revolution brought political and economic instability in theshort term. Businesses were affected, and the protests causedmany of them to have to close. In addition, employees of Egypt’sstock market did not report, causing it to close also. In addition,public safety was undermined when many police officers deserted

their posts, so tourists stayed away which caused the related rev-enues to fall. In addition, the people’s personal property also cameunder attack (e.g., businesses, homes, automobiles, etc.), but manyEgyptians who had ties with their neighbors protected their prop-erty from damage and looting.

In the aftermath of the Egyptian revolution, the indicators sug-gest there will be a favorable long-run outcome, including a morepositive, attractive and stable political and social environment,with opportunities for further growth and economic development.For example, Egypt is expected to rank higher in terms of typicalnational governance indicators, including better government effec-tiveness, higher regulatory quality, and improved control of cor-ruption. A more favorable environment will encourage foreigninvestments in Egypt. In addition, the expectations are that morepeople’s voices will be heard, and there will be more accountabilityfor the government’s actions. This will occur when the governmentallows Egyptians to select their government leaders and exercisefreedom of speech.

References

Al-Shobakky, W. The rise of Middle East technology parks. SciDev Net (March 10,2007). Available at www.scidev.net/en/features/the-rise-of-middle-east-technology-parks.html.

Bazzi, M. Iran elections: latest news. Washington Post (June 12, 2009). Available atwww.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/discussion/2009/06/12/DI2009061202321.html.

Bickart, B., and Schindler, R. M. Internet forums as influential sources of consumerinformation. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 15, 3, 2001, 31–40.

Brown, J., Broderick, A. J., and Lee, N. Word of mouth communication within onlinecommunities: conceptualizing the online social network. Journal of InteractiveMarketing, 21, 3, 2007, 2–20.

Cardon, P. W., Marshall, B., Horris, D. T., Cho, J., Choi, J., Cui, L., Collier, C., El-Shinnaway, M. M., Goreva, N., Nillson, S., North, M., Raungpaka, V., Ravid, G.,Swensson, L., Usluata, A., Valenzuala, J. P., Wang, S., and Whelan, C. Online andoffline social ties of social network website users: an exploratory study ineleven societies. Journal of Computer Information Systems, 50, 1, 2009, 54–64.

Carmichael, M. What consumers want from brands online? Advertising Age, 82, 9,2011, 20.

Casalo, L. V., Flavian, C., and Guinaliu, M. Relationship quality, communitypromotion and brand loyalty in virtual communities: evidence from freesoftware communities. International Journal of Information Management, 30, 4,2010, 357–367.

Central Intelligence Agency. The world factbook. United States Government,Washington, DC (May 15, 2011). Available at www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/eg.html.

Cook, C. Mobile marketing and political activities. International Journal of MobileMarketing, 5, 1, 2010, 154–163.

Cooke, M., and Buckley, N. Web 2.0, social networks and the future of marketresearch. International Journal of Market Research, 50, 2, 2008, 267–292.

Coyle, C. L., and Vaugh, H. Social networking: communication revolution orevolution? Bell Labs Technical Journal, 13, 2, 2008, 13–18.

Daragahi, B. Unrest in Egypt; Arab unity melts fear; watching others rise upempowers the discontented across the region. Los Angeles Times, January 30,2011, A1.

Dholakia, U. M., Bagozzi, R. P., and Klein Pearo, L. A Social influence model ofconsumer participation in network and small-group-based virtualcommunities. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 21, 3, 2004, 241–263.

Economy Watch. Egypt economy (May 15, 2011). Available at www.economywatch.com/world_economy/egypt.

Ellison, N. B., Steinfield, C., and Lampe, C. The benefits of Facebook ‘‘friends:’’ socialcapital and college students’ use of online social network sites. Journal ofComputer-Mediated Communication, 12, 4, 2007, 1143–1168.

Encyclopedia of the Nations. Egypt: country overview (May 15, 2011). Available atwww.nationsencyclopedia.com/economies/Africa/Egypt.html.

Gefen, D., and Straub, D. W. Consumer trust in B2C e-commerce and the importanceof social presence: experiments in e-products and e-services. Omega, 32, 6,2004, 407–424.

Gil-Or, O. The potential of Facebook in creating commercial value for servicecompanies. Advances in Management, 3, 2, 2010, 20–25.

Guobin, Y. Online activism. Journal of Democracy, 20, 3, 2010, 33–36.Grabner-Krauter, S. The role of consumers’ trust in online-shopping. Journal of

Business Ethics, 39, 1, 2002, 43–50.Grabner-Krauter, S. Web 2.0 social networks: the role of trust. Journal of Business

Ethics, 90, 4, 2010, 505–522.Harridge-March, S., and Quinton, S. Virtual snakes and ladders: social networks and

the relationship marketing loyalty ladder. The Marketing Review, 9, 2, 2009,171–181.

374 A.M. Attia et al. / Electronic Commerce Research and Applications 10 (2011) 369–374

Hartmann, R. W., Manchanda, P., Nair, H., Bothner, M., Dodds, P., Godes, D.,Hosanagar, K., and Tucker, C. Modeling social interactions: identification,empirical methods and policy implications. Market Letters, 19, 3–4, 2008, 287–304.

Ho, S. China blocks some Internet reports on Egypt protests. Voice of America News(January 31, 2011). Available at www.voanews.com/english/news/China-Blocks-Some-Internet-Reports-on-Egypt-Protests-114925514.html.

Hodge, N. Inside Molodva’s Twitter revolution. Wired (April 8, 2009). Available atwww.wired.com/dangerroom/2009/04/inside-moldovas.

Hofstede, G. H. Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions, andOrganizations across Nations, 2nd edition. Sage Publications, Beverly Hills, CA,2001.

Kang, C., and Shapira, I. Facebook’s Egypt conondrum. The Washnington Post, 3, 2011,A13.

Kaufmann, D., Kraay, A., and Mastruzzi, M. Governance matters VII: Aggregate andindividual governance indictors, 1996–2007. World Bank policy researchworking paper no. 4654, World Bank, Washington, DC, 2008.

Kaufmann, D., Kraay, A., and Mastruzzi, M. The worldwide governance indicators:methodology and analytical issues. World Bank policy research working paperno. 5430, World Bank, Washington, DC, 2010.

Lai, L. S. L., and Turban, E. Groups formation and operations in the Web 2.0environment and social networks. Group Decision Negotiation, 17, 5, 2008, 387–402.

Levy, J. Beyond boxers or briefs? Phi Kappa Phi Forum, 88, 2, 2008, 14–16.Lin, H. F. Antecedents of virtual community satisfaction and loyalty: an empirical

test of competing theories. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 11, 2, 2008, 138–144.Marandi, E., Little, E., and Hughes, T. Innovation and the children of the revolution.

The Marketing Review, 10, 2, 2010, 169–183.McKenna, K. Y. A., and Bargh, J. A. Causes and consequences of social interaction on

the Internet. Media Psychology, 1, 3, 1999, 249–269.McKnight, H. D., and Chervany, N. L. What trust means in e-commerce customer

relationships: an interdisciplinary conceptual typology. International Journal ofInternational Commerce, 6, 2, 2002, 35–59.

Mortimore, R. Why politics needs marketing. International Journal of Nonprofit andVoluntary Sector Marketing, 8, 2, 2003, 107–121.

Muscara, A. Egypt: a revolution, unplugged. Global Issues (February 1, 2011).Available at www.globalissues.org/news/2011/02/01/8367.

Pelling, E. L., and White, K. M. The theory of planned behavior applied to youngpeople’s use of social networking web sites. Cyber Psychology and Behavior, 12, 6,2009, 755–759.

Robertson, S. P., Vatrapu, R. K., and Medina, R. Off the wall political discourse:facebook use in the 2008 US presidential outlook. Information Polity, 15, 1–2,2010, 11–31.

Shaheen, M. A. Use of social networks and information seeking behavior of studentsduring political crises in Pakistan: a case study. The International Informationand Library Review, 40, 3, 2008, 142–147.

Shapiro, S. M. Can social networking turn disaffected young Egyptians into a forcefor democratic change? New York Times Magazine, 25, 2009, 34–39.

Shen, Y. C., Huang, C. Y., Chu, C. H., and Liao, H. C. Virtual community loyalty: aninterpersonal-interaction perspective. International Journal of ElectronicCommerce, 15, 1, 2010, 49–73.

Shirky, C. The political power of social media. Foreign Affairs, 90, 1, 2011, 28–41.Shokry, S. Choice of speech site affirms Egypt’s importance in world. Modern Egypt

Info (May 18, 2009). Available at www.modernegypt.info/online-newsroom/op-eds/choice-of-speech-site-affirms-egypts-importance-in-world.

Smith, T., Coyle, J. R., Lightfood, E., and Scott, A. Reconsidering models of influence:the relationship between consumer social networks and word-of-moutheffectiveness. Journal of Advertising Research, 47, 4, 2007, 387–397.

Smeltzer, S., and Keddy, D. Won’t you be my (political) friend? The changing face(book) of socio-political contestation in Malaysia. Canadian Journal ofDevelopment Studies, 30, 3-4, 2010, 421–440.

Steinberg, B., and Forget, T. V. today‘s consumers more attached to Google, Amazon.Advertising Age, 81, 34, 2010, 16–17.

Stephen, A. T., and Toubia, O. Deriving value from social commerce networks.Journal of Marketing Research, 47, 2, 2010, 215–228.

Vericat, H. Accidental activists: using Facebook to drive change. Journal ofInternational Affairs, 64, 1, 2010, 177–180.

Wills, D., and Reeves, S. Facebook as a political weapon: information in socialnetworks. British Politics, 4, 2, 2009, 265–281.

World Bank. Worldwide good governance indicators: 1996–2005. Washington, DC,2006. www.worldbank.org/wbi/governance/data. Retrieved April 26, 2009.

Yenikeev, R. Egypt: Mubarak’s surrender to the US. The War among World Centers(January 2, 2011). Available at www.win.ru/school/6427.phtml. Translatedfrom Russian.

Zeithaml, V. A., Berry, L. L., and Parasuraman, A. The behavioral consequences ofservice quality. Journal of Marketing, 60, 2, 1996, 31–46.

Zhang, W., Johnson, T. J., Seltzer, T., and Bichard, S. L. The revolution will benetworked: the influence of social networking sites on political attitudes andbehavior. Social Science Computer Review, 28, 1, 2010, 75–92.