Chandra Prakash Bhongir, Civil Engr, May04 - TTU DSpace Home

-

Upload

khangminh22 -

Category

Documents

-

view

1 -

download

0

Transcript of Chandra Prakash Bhongir, Civil Engr, May04 - TTU DSpace Home

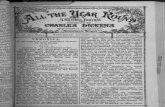

HISTORICAL AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL RESEARCH INTO

THE SINGER STORE, A FRONTIER LUBBOCK

COMMERCIAL VENTURE

by

KAREN KAYE BILBREY HICKS, B.A.

A THESIS

IN

INTERDISCIPLINARY STUDIES

Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in

Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for

the Degree of

MASTER OF ARTS

Approved

Eileen Johnson Chairperson of the Committee

Gary Elbow

John White

Accepted

John Borrelli Dean of the Graduate School

December, 2005

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

My efforts to expand understanding of the history of the Singer Store were

greatly facilitated by assistance from many parties. I am deeply grateful for the

support and guidance afforded me by Dr. Eileen Johnson. Not only did she

provide the opportunity, direction, and encouragement necessary for completion

of the research, but it is largely through her efforts that the Lubbock Lake

Landmark has become the world renowned research center that it is today. I am

also indebted to committee members John White and Dr. Gary Elbow for their

patience and interest in the project.

The archaeological aspect of the Singer research was entirely dependent

on the dedicated and cheerful work of the 1996-1998 field crews. I benefited not

only from their efforts in the field but from their camaraderie and shared

experience as well. Other technical support was provided by Lubbock Lake

Landmark and Museum of Texas Tech University staff members. Field

photography and artifact photographs were provided by Rebecca Hinrichs Lewis,

Dr. Mary Lee Bartlett, and Tara Johnson. Assistance with artifact analysis is

credited to Susan Baxevanis, Terri Carnes, and Jennifer Torres. Finishing detail

for some of the maps and figures was provided by draftsmen Scott Malone and

Marcus Hamilton. James Johnson of the Blackwell Museum, Felix Barbosa-

Retana, and Max Winn, provided insight that aided artifact identification.

ii

The field research was conducted under Texas Historical Commission

Permit for Archeological Investigations #1515 and supported by funding from the

Museum of Texas Tech University, Museum of Texas Tech University

Association, Office of the President of Texas Tech University, Southwestern Bell,

Summerlee Foundation, Plum Foundation, and Center for Field Research

(EARTHWATCH). Recovered artifacts were accessioned and cataloged and are

held with their associated documentation (field notes, photodocuments,

drawings) in the Anthropology Division of the Museum of Texas Tech University.

Among those assisting with the historical research, I am in debt to Dessie

Redwine and George Hawkins who shared with me their personal histories. The

archival research into the Singer history was facilitated by the staff of the

Southwest Collection, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, Texas; the Research

Center at Panhandle Plains Museum, Canyon, Texas; the Haley Memorial

Library and History Center, Midland, Texas; General Land Office of the State of

Texas, Austin; and the Reference Staff of the Chicago Public Library.

Finally, I am most deeply grateful for the enduring support and patience of

my family and their continuous encouragement.

iii

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS......................................................................................ii

LIST OF TABLES .................................................................................................vi

LIST OF FIGURES .............................................................................................vii

CHAPTER

I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................... 1

II. THEORY............................................................................................ 7

III. BACKGROUND ............................................................................... 11

Environmental Context ............................................................ 12

Societal Context....................................................................... 21

Concluding Statement ............................................................. 31

IV. HISTORIC CONTEXT ..................................................................... 33

Concluding Statement ............................................................. 47

V. ARCHAEOLOGICAL RESEARCH................................................... 48

1996 Archaeological Survey .................................................... 50

Excavation ............................................................................... 57

Concluding Statement ............................................................. 85

VI. ARTIFACT ANALYSIS..................................................................... 87

Glass ....................................................................................... 87

Ceramic ................................................................................... 94

Metal........................................................................................ 98

iv

Miscellaneous Artifacts .......................................................... 138

Faunal Remains..................................................................... 145

Concluding Statement ........................................................... 148

VII. DISCUSSION ................................................................................ 149

Archaeological Findings......................................................... 150

Historic Association ............................................................... 160

Findings Summary................................................................. 162

Regional Comparisons .......................................................... 165

Concluding Statement ........................................................... 181

VIII. CONCLUSION............................................................................... 182

REFERENCES................................................................................................. 187

v

LIST OF TABLES

3.1 Species represented in material recovered from stratum 5, Lubbock Lake Landmark.......................................................................... 21 5.1 Artifacts recovered from the 1996 survey in the southwestern quadrant of the Lubbock Lake Landmark................................................. 56 5.2 Artifacts recovered from the 1997 test excavation at 41LU31 in the

southwestern quadrant of the Lubbock Lake Landmark .......................... 61 5.3 Artifacts recovered from Unit 53S8E during 1997 test excavation at 41LU1 Area 8 in the southwestern quadrant of the Lubbock Lake

Landmark................................................................................................. 69 5.4 Artifacts recovered from Unit 41S10E during 1997 test excavation at

41LU1 Area 8 in the southwestern quadrant of the Lubbock Lake Landmark................................................................................................. 69

5.5 Artifacts recovered from Unit 37S0E during 1997 test excavation at 41LU1 Area 8 in the southwestern quadrant of the Lubbock Lake

Landmark................................................................................................. 70 5.6 Artifacts recovered from Unit 35S10E during 1997 test excavation at

41LU1 Area 8 in the southwestern quadrant of the Lubbock Lake Landmark................................................................................................. 70

5.7 Artifacts recovered from Unit 27N1E during 1997 test excavation at 41LU1 Area 8 in the southwestern quadrant of the Lubbock Lake

Landmark................................................................................................. 71 5.8 Artifacts recovered from 1998 block excavation at 41LU1 Area 8 in the southwestern quadrant of the Lubbock Lake Landmark .................... 78 6.1 Bone recovered from 1997 and 1998 excavations at 41LU1 Area 8 in the southwestern quadrant of the Lubbock Lake Landmark............... 147

vi

LIST OF FIGURES

1.1 The marker commemorating the Singer Store is located in the southwest portion of the Lubbock Lake Landmark..................................... 3 3.1 Location of Southern High Plains in relation to Texas and the Great Plains ............................................................................................. 13 4.1 Map showing location of Estacado and Lubbock Lake Landmark in

Lubbock County....................................................................................... 35 4.2 The Plains Museum Society installed an historical marker at the site Of the Singer Store in 1932. Photograph courtesy of the Southwest

Collection/Special Collections Libraries, Texas Tech University, SWCPC 57(K)-E11 .................................................................................. 38 4.3 Roughly shaped caliche used as house foundation for early Lubbock

home. Photograph courtesy of the Southwest Collection/Special Collection Libraries, Texas Tech University, Dorothy Rylander

Photograph Collection, SWCPC 332-E1 #2............................................. 39 4.4 Receipt from Singer Store for goods purchased by XIT cowboys. XIT Ranch Collection, Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum Research Center, Canyon, Texas............................................................ 41 4.5 Image of Dequasie’s application for first Lubbock Post Office. Records of the Post Office Department, National Archives, Washington, D.C...................................................................................... 42 4.6. George Singer wrote this letter to Hank Smith asking for payment on his account. Hank Smith Papers, Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum Research Center, Canyon, Texas ............................................. 43 4.7 Map showing location of Lubbock Lake Landmark relative to first post office (Historic Marker) and to land claimed by George W. and Rachel Singer .......................................................................................... 44 4.8 The Singer Store in the original town of Lubbock was located at the corner of Singer Street and North First Street (now Buddy Holly Avenue and Main Street) ......................................................................... 46

vii

5.1 Areas of Lubbock Lake Landmark addressed in the Singer Store Research ................................................................................................. 51 5.2 Portion of Lubbock Lake Landmark covered in 1996 pedestrian Survey...................................................................................................... 52 5.3 Distribution of artifacts and remote sensing targets piece-point plotted during the 1996 field season Singer Store research survey at the Lubbock Lake Landmark................................................................ 53 5.4 Distribution of diagnostic historic artifacts located during the 1996 field season Singer Store research survey at the Lubbock Lake Landmark................................................................................................. 55 5.5 Plan view of excavation units opened during the test excavation at

41LU31 .................................................................................................... 60 5.6 Location of test units opened during the 1997 field season test excavation at 41LU1 Area 70................................................................... 63 5.7 Location of test excavation units opened during the 1997 field season at 41LU1 Area 8 .......................................................................... 66 5.8 Close-up of plan view of test excavation units opened during the 1997 field season at 41LU1 Area 8.......................................................... 68 5.9 Location of excavation units opened during the 1997 and 1998 field

seasons at 41LU1 Area 8 ........................................................................ 73 5.10 Profile of the north wall of units 2S4E to 2S10E during the 1998 field

season block excavation at 41LU1 Area 8............................................... 74 5.11 Horizontal distribution of artifacts from feature FA8-16 recovered during the 1997-1998 field season excavation at 41LU1 Area 8.............. 75 5.12 Detailed location of excavation units opened during the 1997 and 1998 field seasons at 41LU1 Area 8........................................................ 76 5.13 Close up view of artifact distribution in group A showing artifact

concentration in the area of anomalous sediment in units 4S0E, 5S0E, and 4S1E ...................................................................................... 80 5.14 Close-up of charcoal concentration in the northwest quadrant of unit 2N3E........................................................................................................ 82

viii

5.15 Vertical distribution of artifacts recovered from FA8-16 (historic debris scatter) during the 1998 field season block excavation at 41LU1 Area 8. Scale is not proportional ................................................. 84 6.1 Segments of a panel bottle (TTU-A93111, TTU-A93112, TTU-A93113, TTU-A93114, TTU-A93115) further broken in situ recovered from 1998 block excavation at 41LU1 Area 8 in the

southwestern quadrant of the Lubbock Lake Landmark ........................ 88 6.2 Distribution of melted glass shards recovered from 1997 and 1998

excavations at 41LU1 Area 8 in the southwestern quadrant of the Lubbock Lake Landmark.......................................................................... 92 6.3 Distribution of unmelted glass shards recovered from 1997 and 1998

excavations at 41LU1 Area 8 in the southwestern quadrant of the Lubbock Lake Landmark.......................................................................... 93 6.4 Distribution of ceramic sherds recovered from 1997 and 1998 excavations at 41LU1 Area 8 in the southwestern quadrant of the Lubbock Lake Landmark.......................................................................... 94 6.5 Two segments of a porcelain doorknob (TTU-93716, TTU-A 94161)

recovered from 1998 block excavation at 41LU1 Area 8 in the southwestern quadrant of Lubbock Lake Landmark ................................ 95

6.6 Very faint maker’s mark visible on right half of ceramic sherd TTU-A73384 recovered from 1998 block excavation at 41LU1 Area 8 in the southwestern quadrant of Lubbock Lake Landmark.................... 96 6.7 A “pie-crust” prosser button (TTU-A96340) recovered from 1998 block

excavation at 41LU1 Area 8 in the southwestern quadrant of the Lubbock Lake Landmark.......................................................................... 97 6.8 Cartridge casings (TTU-A90646, TTU-A95911, TTU-A95941, TTU-

A73495, TTU-A94799) recovered from 1998 block excavation at 41LU1 Area 8 in the southwestern quadrant of the Lubbock Lake

Landmark................................................................................................. 99 6.9 Distribution of cartridges recovered from central units of 1997 and 1998 excavations at 41LU1 Area 8 in the southwestern quadrant of the Lubbock Lake Landmark.................................................................. 100

ix

6.10 Distribution by caliber of cartridge casings recovered from 1997 and 1998 excavation at 41LU1 Area 8 in the southwestern quadrant of the Lubbock Lake Landmark.................................................................. 103

6.11 Remains of burned ammunition recovered from 1998 block excavation at 41LU1 Area 8 in the southwestern quadrant of the

Lubbock Lake Landmark........................................................................ 102 6.12 Hole-in-cap can (TTU-A85755) recovered during the 1996 survey of the southwestern quadrant of the Lubbock Lake Landmark .............. 104 6.13 Diagram showing horizontal distribution of all whole and fragmentary square nails recovered from 1997 and 1998 excavations at

41LU1 Area 8 in the Southwestern quadrant of the Lubbock Lake Landmark............................................................................................... 107 6.14 Type and size of whole nails recovered from 1997 and 1998 excavations at 41LU1 Area 8 in the southwestern quadrant of the Lubbock Lake Landmark.................................................................. 109 6.15 Distribution of shoe nails recovered from 1997 and 1998 excavations at 41LU1 Area 8 in the southwestern quadrant of the

Lubbock Lake Landmark........................................................................ 111 6.16 Screws (TTU-A94216, TTU-A94963, TTU-A73425, TTU-A93811, TTU-A94483) recovered from 1997 and 1998 excavations at 41LU1 Area 8 in the southwestern quadrant of the Lubbock Lake

Landmark............................................................................................... 113 6.17 Examples of Frentress’ Diamond barbs (TTU-A94880, TTU-A94881, TTU-A96104) recovered from 1997 and 1998 excavations at

41LU1 Area 8 in the southwestern quadrant of the Lubbock Lake Landmark............................................................................................... 115

6.18 Distribution of barbs recovered from 1997 and 1998 excavations at

41LU1 Area 8 in the southwestern quadrant of the Lubbock Lake Landmark............................................................................................... 116

6.19 Distribution of fence staples recovered from 1997 and 1998 excavations at 41LU1 Area 8 in the southwestern quadrant of the Lubbock Lake Landmark........................................................................ 118

x

6.20 Brass straight pins (TTU-A94336, TTU-A93845) recovered from 1997 and 1998 excavations at 41LU1 Area 8 in the southwestern quadrant of the Lubbock Lake Landmark............................................... 119 6.21 Horizontal distribution of brass straight pins recovered from 1997 and 1998 excavations at 41LU1 Area 8 in the southwestern quadrant of the Lubbock Lake Landmark............................................... 119 6.22 Pen nibs (TTU-A90799, TTU-A94187, TTU-A95720) recovered from 1997 and 1998 excavations at 41LU1 Area 8 in the southwestern quadrant of the Lubbock Lake Landmark ........................ 120 6.23 Horizontal distribution of rivets and rivet burrs recovered from 1997 and 1998 excavations at 41LU1 Area 8 in the southwestern quadrant of the Lubbock Lake Landmark............................................... 121 6.24 Horizontal distribution of metal buttons recovered from 1997 and 1998 excavations at 41LU1 Area 8 in the southwestern quadrant of the Lubbock Lake Landmark.............................................................. 123 6.25 Shield Nickel (TTU-A94855) recovered from 1998 block excavation at 41LU1 Area 8 in the southwestern quadrant of the Lubbock Lake

Landmark............................................................................................... 124 6.26. Selection of cast iron objects (TTU-A93788, TTU-A93006, TTU- A96288, TTU-A94853) recovered from 1998 block excavation at 41LU1 Area 8 in the southwestern quadrant of the Lubbock Lake

Landmark............................................................................................... 125 6.27 Diagram depicting artifact TTU-A94311 and an example of a platform scale showing the support element.......................................... 126 6.28 Both sides of an unidentified cast iron artifact (TTU-A94186) recovered from 1998 block excavation at 41LU1 Area 8 in the

southwestern quadrant of the Lubbock Lake Landmark ........................ 127 6.29 Adjacent cast iron corner fragments TTU-A90567 and TTU-A92907

recovered from 1997 and 1998 excavation at 41LU1 Area 8 in the southwestern quadrant of the Lubbock Lake Landmark, as seen

from the underside................................................................................. 127

xi

6.30 Bolt (TTU-A90577), cast iron (TTU-A90567), and square nail (TTU-A90582) recovered from unit 2S4E during 1997 test excavation at

41LU1 Area 8 in the southwestern quadrant of the Lubbock Lake Landmark............................................................................................... 128

6.31 Both sides of a knife (TTU-A85756) recovered during the 1996 survey of 41LU1 Area 8 at the Lubbock Lake Landmark ....................... 129 6.32 Flattened bell portion of brass funnel TTU-A94966 recovered from 1998 block excavation at 41LU1 Area 8 in the southwestern quadrant of the Lubbock Lake Landmark............................................... 130 6.33 Wire (TTU-A94932) resembling a hairpin recovered from 1998 block

excavation at 41LU1 Area 8 in the southwestern quadrant of the Lubbock Lake Landmark........................................................................ 131 6.34 Spoon bowl (TTU-A73390) recovered from 1998 block excavation at

41LU1 Area 8 in the southwestern quadrant of the Lubbock Lake Landmark............................................................................................... 131

6.35 Metal ring (TTU-A92039) recovered from unit 37S0E during 1997 test excavation at 41LU1 Area 8 in the southwestern quadrant of the Lubbock Lake Landmark........................................................................ 132 6.36 A T-shaped brass brad (TTU-A93823) recovered during 1998 block

excavation at 41LU1 Area 8 in the southwestern quadrant of the Lubbock Lake Landmark........................................................................ 133 6.37 Horseshoe remnant (TTU-A93719) recovered from unit 2S9E during 1998 block excavation at 41LU1 Area 8 in the southwestern quadrant of the Lubbock Lake Landmark............................................... 133 6.38 Buckles and a D-ring recovered during excavation at 41LU1 Area 8 in the southwestern quadrant of the Lubbock Lake Landmark............... 135 6.39 Chain fragment TTU-A94176 recovered during 1998 block excavation at 41LU1 Area 8 in the southwestern quadrant of the Lubbock Lake Landmark........................................................................ 136 6.40 Probable handles recovered during 1998 block excavation at 41LU1 Area 8 in the southwestern quadrant of the Lubbock Lake Landmark............................................................................................... 136

xii

6.41 Artifacts with “corkscrew” components recovered from 4S2E during 1998 block excavation at 41LU1 Area 8 in the southwestern quadrant of the Lubbock Lake Landmark............................................... 137 6.42 Unidentified iron artifact (TTU-A94533) recovered during 1998 block

excavation at 41LU1 Area 8 in the southwestern quadrant of the Lubbock Lake Landmark........................................................................ 138 6.43 Distribution of slate pencil fragments recovered from 1997 and 1998

excavations at 41LU1 Area 8 in the southwestern quadrant of the Lubbock Lake Landmark........................................................................ 139 6.44 Distribution of rubber artifacts recovered from 1997 and 1998 excavations at 41LU1 Area 8 in the southwestern quadrant of the Lubbock Lake Landmark........................................................................ 141 6.45 Distribution of caliche recovered from 1997 and 1998 excavations at

41LU1 Area 8 in the southwestern quadrant of the Lubbock Lake Landmark............................................................................................... 143

6.46 Unknown artifact TTU-A94623 that appears to be a fragment broken off of the original Singer Store Historical Marker........................ 146 7.1 Horizontal distribution of structure related artifacts recovered from 1997 and 1998 excavations at 41LU1 Area 8 in the southwestern quadrant of the Lubbock Lake Landmark............................................... 152 7.2 Horizontal distribution of ammunition related artifacts recovered from 1997 and 1998 excavations at 41LU1 Area 8 in the southwestern quadrant of the Lubbock Lake Landmark ........................ 156 7.3 Distribution of melted and unmelted glass recovered from 1997 and 1998 excavations at 41LU1 Area 8 in the southwestern quadrant of the Lubbock Lake Landmark.................................................................. 159 7.4 Topographic map of portion of the Lubbock Lake Landmark prepared by Green and depicting location of a small drainage below

railroad trestle along the southern edge (Kazcor, 1978) ........................ 163 7.5 Photograph of early Lubbock. The second building from the right is

reportedly the Singer Store (Bronwell, 1980). Photograph courtesy of the Southwest Collection/Special Collections Library, Texas Tech

University, Lubbock, Texas, Museum Photograph Collection, Box 1, Accession number 1948-7-9 .................................................................. 176

xiii

CHAPTER I

INTRODUCTION

The United States frontier reached the Southern High Plains of Texas only

in the latter part of the 19th century (Holden, 1936; 1962a). Since this time, the

area has undergone widespread agricultural development and local urbanization.

County histories, memoirs, and anecdotal accounts have preserved general

information and some details of settlement across this region. However,

cultivation and building activities have destroyed much of the physical fabric of

history (Sasser, 1993). Features such as dugouts, houses and other structures,

and the once ubiquitous windmill, largely have disappeared from the landscape

along with many artifacts. The Singer Store is one such element.

The Singer Store was an important component of the United States early

history on the Southern High Plains of Texas. Some considered the store, as an

early commercial venture, to be the beginning of the community of Lubbock

(Conner, 1962a; Johnson and Holliday, 1987). The young Singer family

represented the first American settlers to make the local area their home. They

arrived in the central portion of Lubbock County in the early 1880s and remained

at this location until 1886 when their store building burned. The Singers rebuilt

the store in a different location, and eventually moved to the new town of

Lubbock.

1

The story of the Singers and the Singer Store represents one phase of the

United States frontier as it developed on the Southern High Plains of Texas.

Information regarding the Singer occupation relates to the progression of the

frontier from the open-range ranching era to settlement. However, the historic

record of the Singers and the store is limited. Details such as the exact location

and the date when the Singers first arrived are in question. One reported

location of the store is on the southwest side of a small lake (Burns, 1923)

nestled in a meander of Yellowhouse Draw. A historic marker erected in 1932

commemorates the store at this reported location (Fig. 1.1). However, other

historic accounts (Truett, 1982) described another location for the store.

The historic marker location is now within the boundaries of Lubbock Lake

National Historic and State Archeological Landmark (Lubbock Lake Landmark),

an archaeological and natural history preserve (Johnson, 1987; Johnson and

Holliday, 1989). This circumstance affords a unique opportunity to apply

archaeological and historical investigation to reports of the Singer Store. The

primary research hypothesis of the study is that a 19th century Singer Store

located at the present-day Lubbock Lake Landmark would be represented in the

preserved archaeological record and that recoverable data would correlate to

historic accounts of the Singer Store. Previous archaeological investigations at

the Lubbock Lake Landmark have recovered limited 19th century material (Green,

1962; Kelley, 1974; Sierchula, 1974; Denton, 1977; Kazcor, 1978) in an area

(41LU1 Area 8) that would have been on the southwest side of the lake.

2

Figure 1.1. The marker commemorating the Singer Store is located in the

southwest portion of the Lubbock Lake Landmark.

3

The main research objective is the establishment of a definite location of

the store, chronology of the store’s history, and details regarding the specific

nature (i.e., stocked merchandise) of the store. The information will contribute to

the goal of understanding the Singer Store in relation to the progression of the

frontier. That understanding will in turn contribute to the formation of a database

for further study of the United States frontier on the Southern High Plains of

Texas. Information about the development of the frontier in this unique physical

and temporal environment constitutes a case study in comparative frontier

investigations that seek to understand the behavioral aspects of such processes

as modernization, globalization, industrialism, and the expansion of western

nations and their institutions. Information from this unique frontier can help

illustrate how the character of the core society is reflected in the frontier. In

combination with data from other sites on a regional scale, investigation of the

Singer Store can help examine frontier processes and document how the frontier

differs from the societal core (or cores) as well as how material culture within the

frontier changes as settlement, economies, and transportation systems develop.

The archaeological record is an important resource in examining change,

continuity, and interactions between social groups within a frontier setting (Orser

and Fagan, 1995). The archaeological focus area for the study is the

southwestern portion of the Lubbock Lake Landmark, encompassing both valley

margin and upland topography around a meander in Yellowhouse Draw where a

lake was located. Research has concentrated on this part of the Landmark due

4

to historic accounts describing the store’s location and the presence of 19th

century material in 41LU1 Area 8.

Archaeological work conducted during the Lubbock Lake Landmark

summer field seasons from 1996 through 1998 progressed through three phases

of investigation: pedestrian survey, subsurface testing, and block excavation.

Evidence recovered included artifacts and spatial information from the field that

underwent further analysis in the lab. Also uncovered were features that merit

future investigation in the field.

Research of text resources, including historic records, accounts, and oral

histories, assisted and expanded on information recovered from archaeological

work. An examination of Lubbock County deed records sought information that

would constrict further the area of archaeological investigation and a search was

made to find a map showing the location of the store. Accounts and oral

histories, while inherently limited by their subjective nature, contained

descriptions of the store and its contents that were significant in interpreting

recovered archaeological data.

Specific research questions addressed include whether appropriate 19th

century material persists in the archaeological record and, if so, whether the

material is in accord with historic accounts of the store’s construction,

dimensions, and contents. Evidence of store merchandise should reflect a

limited and specialized clientele specific to hunting and ranching frontiers.

Similarly, recovered information should be characteristic of a frontier tied to an

5

industrial society with an expanding transportation system, but one in which

conditions such as isolation and scarcity of goods persist as factors to be dealt

with by settlers.

6

CHAPTER II

THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

Expansion into new territories and habitats is a fundamental human

behavior, as evidenced by the global human presence. With this movement, the

boundaries (or frontier of a society) expand, often bringing the society into

contact with environments containing previously unknown elements, including

other societies. American expansion on the Southern High Plains represents a

frontier developing in a unique environment characterized by distinct social,

technological, and economic conditions. Frontier is a term applied to a specific

period within the continuum of development that moves through colonization,

settlement, and, sometimes, depopulation.

Frontier studies seek to understand the processes and patterns of human

behavior inherent in both the causes and consequences of such expansion

(Green and Perlman, 1985). Research on the Singer Store should make

available information about frontier conditions and responses on the Southern

High Plains. This information can contribute to comparisons with frontiers that

have developed in similar physical or sociological environments and serve to

assess the role of such factors in shaping frontier societies. In addition, data

specific to the Southern High Plains frontier can be compared to frontiers of

dissimilar environments in seeking developments that are independent of

environment.

7

Compared to the core society, the frontier region is less complex socially,

economically, and politically (Harris, 1977). The basic cultural assumption is that

inferences concerning the development from frontier to settled Anglo-American

society can be made from analysis of evidence inherent in artifacts and historic

documents.

Frontiers develop in systems composed of a number of components

(Wells, 1973) through several processes (Hardesty, 1985) including competition

with native people, animals, or plant communities, colonization, acculturation,

and adaptation. The basic component is a society that is engaged in expansion

into new territories. The expanding society includes elements such as

communication systems, economic systems, ideological systems, and

technology. Another component is the territory into which the society is

expanding. This territory comprises the physical environment and indigenous

societies as well as other expanding societies and factors subsumed within those

societies. These components are inherently complex as separate entities and

their interaction within a frontier also is complex.

The frontier itself is the area of expansion within which constituents of the

expanding society, any indigenous societies, and the environment interact. As

frontiers are open systems (Green and Perlman, 1985), outcomes from these

interactions will affect even the components outside of the actual area of

expansion including the core society. Characteristics of different frontiers derive

in part from specific factors within the societies involved (e.g., economic

8

conditions or technological abilities) and the environment (e.g., environmental

resources or difficult terrain).

Frontiers in different settings vary in character. This quality has led

researchers to designate various categories and types of frontiers, usually based

on economic characteristics (e.g., ranching or mining) (Steffen, 1979; Lewis,

1984; Hardesty, 1985). Steffen (1979, 1980), in examining change and

continuity on the Anglo-American frontier, distinguishes two categories of frontier,

that of insular and cosmopolitan. Insular frontiers are those with limited ties or

links to the core society. This isolation minimizes ameliorating support from the

core society and thus emphasizes the importance of adaptation to the local

environment in achieving success. The necessity to adapt to the local

environment combined with minimal influence from the core society results in

fundamental ideological change.

In contrast to insular frontiers are cosmopolitan frontiers in which change

is superficial, with the underlying ideological bases (e.g., economic, political, and

social views) remaining the same as those of the core society. Steffen (1980)

questions whether settlement on the Great Plains of North America should be

considered a frontier at all as he sees no fundamental change resulting from that

settlement. However, the qualifying conditions of insularity that engender

fundamental, indigenous changes derive from combined environmental and

societal factors (e.g., transportation and/or communication), not from the

processes of expansion and settlement that produce frontiers. Innovations in

9

transportation and communication technologies serve to reduce isolation and

preserve ties between the core society and frontier. Closer ties provide for

participation by the core society in finding solutions to frontier problems as the

core society has an interest in the success of the frontier.

The Singer occupation at Lubbock Lake occurred during the earliest part

of the period of Anglo-American colonization of the Southern High Plains.

Settlement of this region occurred late in the period of United States frontier

development. National territory already extended from the Atlantic to the Pacific

coast and urbanization and industrial development were underway in the East,

Mid-West, and West (Hine, 1984; Paul, 1988). American expansionist activity

preceding settlement on the Llano Estacado included 19th century exploration,

military action to complete the removal of Native Americans from the region, and

the extractive economic practice of buffalo hunting (Holden, 1962a). The battles

and buffalo hunting were also examples of competition with native inhabitants of

the region.

The Singer occupation on the Southern High Plains coincided with that of

the last of the American buffalo hunters, Hispanic sheepherders (pastores), and

finally, American cattle and sheep ranchers. The Singer Store, as a mercantile

venture, represented a specialized activity in its role as a link between the frontier

and the core society. The store served as this link by obtaining and distributing

goods produced in industrial regions and as a Post Office, by providing

communication within the frontier and with the core society.

10

CHAPTER III

BACKGROUND

Human cultures develop, persist, and adapt within a complex network of

components. The components consist of elements of the physical environment

such as landscape and climate as well as elements of the social environment

including relations between separate cultural groups, economic systems,

technologies, and belief systems. Understanding change within a specific human

society requires consideration of as many elements as possible (e.g., Steffen,

1979, 1980; Lewis, 1984; Hardesty, 1985). For frontier research, historic

attributes within the expanding society play a major role influencing frontier

development (Wells, 1973). Therefore, the history of an expanding society as

well as environmental factors provides important context for understanding the

frontier.

The history of the Singer Store unfolds in late 19th century Texas on the

Southern High Plains, a unique environment. United States expansion at this

point in the late 19th century resulted in competition and removal of competing

cultures and fauna from the region, preparing the way for settlement.

11

Environmental Context

The Southern High Plains, also known as the Llano Estacado or Staked

Plains and Caprock, is the southern part of the High Plains (Fig. 3.1; Johnson

and Holliday, 1993). The High Plains, in turn, are the central portion of the vast

Great Plains region of North America (Webb, 1931). Webb (1931:3) identifies

three fundamental features associated with a plains environment: absence of

trees, a sub-humid climate, and a relatively flat or plane surface. Each of these

factors can influence the nature of human/environmental interaction. Although

attributing "the cultural character of the Plains" to any region exhibiting two of the

three features, Webb (1931:4) recognizes the High Plains as the only North

American region characterized by all three factors.

Only the channels of dry riverbeds (draws), ephemeral lakes known as

playas or playa lakes, a few larger salinas or saline lakes, and localized fields of

sand dunes provide relief of the flat Southern High Plains' surface (Holliday,

1995). No extant rivers cross the region today; however, historically, a number of

springs were found along the escarpments, draws, and at salinas (Brune, 1981).

Flowing water was in the lower reaches of most of the draws (Holliday, 1995).

12

Figure 3.1. Location of Southern High Plains in relation to Texas and the Great

Plains. Figure drawn by the author.

13

The Southern High Plains is essentially a large tableland bounded on

three sides by sometimes steep and rugged escarpments rising 50 to 200m

above the surrounding land. Although flat, the land is not level and gently slopes

from a maximum of 1,500m above sea level in the northwest to 750m above sea

level in the southeast (Holliday, 1990). Fluvial erosion is a force that contributed

to the present form of the Southern High Plains. The escarpment to the east has

formed from headward erosion of tributaries of the Red, Colorado, and Brazos

rivers. The Canadian River Valley provides a northern border while similarly, to

the west in New Mexico, is the Pecos River Valley (Holliday, 1990). No well-

defined southern limit occurs. Instead, the High Plains to Edwards Plateau

transition is indicated only by the appearance of Edwards Limestone (Hunt,

1974).

Climate is a major factor influencing the nature of human economy in a

given region, imposing limits on both the natural environment and human use of

the environment. Sub-humid or arid climates are deficient in rainfall needed to

support the same agricultural practices of regions that are more humid (Webb,

1931). For the Southern High Plains, the regional continental climate was

established around 4,500 years ago. Its present expression began about 2,000

years ago (Holliday, 1995) and is classified as semi-arid. Average yearly

precipitation amounts vary from just under 20" (50cm) in the northeast to about

13" (33cm) in the southwest (Haragan, 1983; Bomar, 1995).

14

As important a variable as quantity is the distribution and nature of

precipitation events. The greatest portion of precipitation falls from

thunderstorms during the spring and summer months of May, June, July, and

August. Thunderstorms can deliver large amounts of rain in a short period

creating surface run-off. Thus, a significant portion of the moisture is not

absorbed into the ground (NOAA, 1982) but drains into local playa lakes.

Additionally, total precipitation fluctuates from year to year. Historically, periods

of above average precipitation and drought have played a role in shaping

economic success and settlement on the plains (Brooks and Emel, 2000).

Drought is a well-known and recurring event on the Southern High Plains (NOAA,

1982) with potentially severe environmental and economic consequences.

Average high summer temperatures on the Southern High Plains

generally are into the low 30s°C (90s°F). However, under conditions of

persistent high pressure, temperatures can rise to the upper 30s° (above 100°F).

These excessive high temperatures increase evaporation and suppress rainfall

events that, in dry years, can intensify drought conditions. Low temperatures for

January average about 5° below 0°C (low 20s°F)(Bomar, 1995). Blizzards occur

rarely but can have a devastating effect on the region (NOAA, 1982).

West of 96° longitude, average annual evapotranspiration exceeds annual

average rainfall (NOAA, 1982). Precipitation combined with the variables of

temperature, wind, and humidity yield net soil moisture. On the Southern High

Plains, hot summer temperatures with frequent wind and low humidity serve to

15

increase evaporation. The effect is a deficit of available soil moisture, an

important environmental factor influencing plant and animal communities as well

as viable agricultural technique.

Climate has played a significant role in determining the general soil types

found on the Southern High Plains. Soils primarily have formed within wind-

blown deposits that accumulated over the region during dry periods, blown-in by

high velocity northeast winds. Heavier particles have precipitated out of the

wind-blown material sooner than lighter particles, resulting in sandier soils in the

southern and western parts of the region and soils with higher clay content

occurring in the northern and eastern portions of the Southern High Plains

(Holliday, 1988). This difference in soils contributes to intra-regional variations of

native vegetation and influences human use of resources and settlement

patterns.

In general, the Southern High Plains climate favors native vegetation

dominated by grasses but shrubs and forbs also are part of the regional

vegetation. However, due to the effects of cultivation, urbanization and

development, and overgrazing that occurred since the late 1870s, no pre-

Columbian plant associations and communities remain unaffected and in their

original state. In general, present-day uncultivated land can include stands of

grass varieties including three-awns (Aristida spp.), sweet bluestem

(Bothriochola saccharoides) (Tharp, 1952), sideoats grama (Bouteloua

curtipendula), black grama (B. eriopoda), blue grama (B. gracilis), hairy grama

16

(B. hirsute), buffalograss (Buchlöe dactyloides), and sand or covered-spike

dropseed (Sporobolus cryptandrus) (Choate, 1991). Grass is less dense in the

sandy southern and western parts of the Plains where it can be accompanied by

shin oak (Quercus havardii), mesquite (Prosopsis glandulosa), and sand sage

(Artemisia filifolia) (Choate, 1991).

Historic accounts of 19th century vegetation of the Southern High Plains

were few and limited to local conditions. Charles Goodnight, an early cattle

rancher at the northern edge of the Southern High Plains, described tall western

wheat grass (Agroppyron smithii) growing around and in the playas (Tharp,

1952). Surveyors of the state’s Capitol Reservation land on the Southern High

Plains found much of the land occupied by mesquite, grama, sedge (Carex spp.

and Cyperus spp.), bunch, (little bluestem, three awn, and sand dropseed are

examples of bunch grass – this term describes growth habit), and bluestem

grasses (Spaight, 1882). Similarly, Holden (1962b), an historian acquainted with

some early settlers, described a turf of buffalograss and blue grama growing on

the level uplands with side oats grama, bluestem, and tall switch grass (Panicum

virgatum) growing in moist locations. Mesquite and cat’s claw acacia (Acacia

greggii) were among shrubby plants settlers encountered (Holden, 1962b).

Draws and the escarpment provided the only native timber with hackberry (Celtis

sp.) and cottonwood (Populus spp.) found in the draws (Tharp, 1939; Holden,

1962a; Thompson, 1987). Various junipers (Juniperus spp.) and cedars (Cedrus

spp.) were found along the escarpment (Tharp, 1939; Rathjen, 1973). Moist,

17

shaded areas within the canyons sheltered a number of vines including grapes

(Vitis spp.) and clematis (Clematis spp.) (Tharp, 1939), a flowering vine. Wild

plum (Prunus americana) was also found in the canyons (Tharp, 1939).

These historic accounts are supplemented by results of recent scientific

inquiry. Thompson (1987:33-34), reporting on plant macrofossils recovered from

archaeological investigation at Lubbock Lake Landmark in Yellowhouse Draw,

notes remains of bullrush (Scirpus spp.), devil’s claw (Proboscidea spp.), netleaf

hackberry (Celtus reticulata), prickly poppy (Argemone spp.), nightshade

(Solanum spp.), and mesquite (Prosopis spp.) in the most recent sediments

(stratum 5).

The dominant historic natural vegetation of the Southern High Plains is

grass (Choate, 1991) that supports many large and small herbivores and

associated predators. The grassland of the plains was part of a complex

ecosystem. Prior to 19th century American settlement of the Southern High

Plains when large expanses of grassland remained intact, these extensive

grasslands supported a diverse animal community. Bison (Bison bison) and

pronghorn antelope (Antilocapra americana) were the largest herbivores and

ranged across the Southern High Plains. White-tailed (Odocoileus virginianus)

and black-tailed or mule deer (O. hemionus) were reported from the extreme

northern portions of the Llano Estacado (Romero, 1946). Cottontails (Sylvilagus

spp.), jackrabbits (Lepus californicus), ground squirrels (Spermophilus spp.), and

prairie dogs (Cynomys ludovicianus) were among small animals noted by settlers

18

and hunted by coyotes (Canis latrans), lobo (gray) wolves (C. lupus), and the

swift fox (Vulpes velox). Holden (1962b) recorded two late 19th century

encounters with black bears (Ursus americanus) reported by cowboys working

on the Llano Estacado. Bailey (1905) also recounted a few reports of black

bears near the northeast escarpment or in Palo Duro Canyon. An 1884 letter

from R. J. Michel to Hank Smith in Blanco Canyon refers to a conversation

between Michel and Smith regarding antelope, deer, and bears (Michel, 1884).

Bird varieties included blue quail (Callipepia squamata), bobwhite quail

(Colinus virginianus), prairie chicken (Tympanuchus pallidicinctus), wild turkey

(Meleagris gallopavo), and, at canyon rims and the escarpment, an occasional

eagle (golden eagle - Aquila chysaetos, bald eagle - Haliaetus leucocephalus) or

buzzard (Cathartes aurateter). Ducks (Anatidae) and geese (Branta canadensis)

migrated through the area and some would stay the whole winter. Early settlers

also encountered a number of snakes including the beneficial bull snake

(Pituophis melanoleucus), coach whip (Masticophis flagellum), grass snakes

(possibly Thamnophis spp.), and rattlesnakes (Crotalus spp.) (Holden, 1962b).

The first exotic animals to colonize the Southern High Plains were the

mustangs, or wild horse. The horse herds of the Apache on the Southern High

Plains came from the Santa Fe area through trade and raid. The Comanche in

particular, had sizeable horse herds. The feral horses on the Southern High

Plains most likely descended from this stock as well as being joined by those

19

animals that escaped from the Spanish herds in New Mexico (Worcester, 1944;

Rathjen, 1973; Holden, 1962b; Choate, 1991; Davis and Schmidly, 1994).

Skeletal remains recovered from recent sediments (stratum 5; Table 3.1)

through archaeological investigation at Lubbock Lake supplement historic

accounts of the local Yellowhouse Draw faunal assemblage (Johnson, 1987:50-

63). The box turtle, cottontails, prairie dog, coyote, modern horse, pronghorn

antelope, and modern bison were recovered from lacustrine and valley margin

substrata, with other listed species (Table 3.1) recovered only from lacustrine

substrata.

The region’s lack of natural waterways to facilitate transportation and arid

climate served as limits to the mobility and commerce of potential settlers. To

American explorers unfamiliar with the region, ignorance of water sources lead to

the perception that lack of permanent reliable surface water also constituted a

barrier to 19th century American travel and settlement. Nineteenth century

American explorers who ventured onto the Southern High Plains reported game

to be scarce (Rathjen, 1973), another reason to avoid the region. Later,

however, others who had seen the great buffalo herds understood the region to

hold potential as grazing land for cattle.

20

Table 3.1. Species represented in material recovered from stratum 5, Lubbock Lake Landmark.

Common Name Speciesleopard frog Rana pipiensyellow mud turtle Kinosternon flavescens pond slider Chrysemys scriptabox turtle Terrapene ornataTexas horned lizard Phrynosoma cornutum ground snake Sonora semiannulata checkered garter snake Thamnophis cf. marcianus ribbon snake T. proximuspintail duck Anas acutagadwall duck A. streperaruddy duck Oxyura jamaicensis hawk Buteo spp.American coot Fulica AmericanaSays phoebe cf. Sayornis sayanorthern mocking bird Mimus polyglottisMexican freetail bat Tadarida brasiliensis Audobon cottontail Sylvilagus cf. audobonii cottontail Sylvilagus spp.blacktail jackrabbit Lepus californicusblacktail prairie dog Cynomys ludovicianus hispid pocket mouse Perognathus cf. hispidus pocket mouse Perognathus spp.coyote Canis latransgray wolf C. lupiscommon striped skunk Mephitis mephitismodern horse Equus caballuspronghorn antelope Antilocapra americana modern bison Bison bison

Societal Context

For thousands of years, humans also inhabited the Southern High Plains

(Holden, 1962a; Johnson and Holliday, 1995). These hunter-gatherers left traces

of their activities in the archaeological record. Researchers know little of the

earliest human societies in the region except what they infer from the

21

archaeological record. Much of the material recovered from the record relates to

subsistence, such as products or bi-products of stone tool manufacture or plant

processing technologies. The archaeological record also discloses cultural

constancy or change over time. Interpretations of change in the record include

innovation within a culture, diffusion of new ideas from outside the culture via

travel or trade networks, or displacement.

During the cool, moist late Pleistocene, Paleoindian peoples moved on to

the Southern High Plains, hunting the large mammals of the grassland. Finely

crafted stone implements, especially spear points, characterized Paleoindian

material culture. Environmental change to a warmer, drier climate that began at

the end of the Pleistocene was coincident with cultural change in the

archaeological record. Hunting continued to provide subsistence into the Archaic

period but stone tool technologies were changing and evidence for intense plant

food processing increased. By ca. 4,500 years ago, the climate had ameliorated

and become slightly more humid (Johnson and Holliday, 1995).

New technologies apparent in the archaeological record signal the

beginning of the Ceramic period ca. 2,000 years ago. Pottery and arrow points

attest to technological innovation and/or contact with other culture groups.

Typological change also occurs throughout the Ceramic period, with trade pottery

appearing later in the period (Johnson and Holliday, 1995).

The first precursor of globalization appeared in North America beginning

with late 15th century Spanish contact. On the Southern High Plains, this time

22

marks the start of the Protohistoric period. The Spanish called the native bison

hunters they first encountered in the region the Querechos and the Teyas. The

Querechos probably were the same people later Spaniards referred to as

Apache, and the Teyas may have been a Caddoan group but, more likely, also

were Apache (Newcomb, 1961). Historic accounts place the Apache on the

Southern High Plains by the 16th century (Wedel, 1961; Perry, 1991).

Archaeological evidence indicates an Apache presence before that time, as early

as the mid-15th century (Runkels, 1964; Johnson, et al., 1977).

Direct contact between European and native cultures is not evident in the

Southern High Plains archaeological record until the mid-16th century, although,

due to European expansion, contact and culture change is taking place in other

North American regions. Material yielded by the archaeological record continues

to be indicative of hunter-gatherer subsistence (Johnson and Holliday, 1995).

In 1540, Francisco Vásquez de Coronado began a journey of exploration

that started in Mexico and continued through portions of present-day Arizona,

New Mexico, and Kansas. Although scholars have proposed various routes for

Coronado’s journey across the High Plains (Morris, 1997), recent archaeological

recovery of 16th century Spanish artifacts from Blanco Canyon supports

conjecture of Coronado’s presence on the Southern High Plains (Holden, 1962a;

Blakeslee et al., 1997). This journey was the beginning of continued Spanish

activity in the region as parties occasionally crossed the plains en route between

23

New Mexico and the Concho Valley during the 16th and 17th centuries (Rathjen,

1973).

The Historic period begins on the Southern High Plains about 300 years

ago. Changes evident in the archaeological record of this time include the

appearance in aboriginal contexts of items originating in Europe, such as glass

trade beads, and the butchered remains of modern horse (Johnson and Holliday,

1995).

One significant consequence of Spanish expansion in North America was

the return of the horse and the introduction of horsemanship to native peoples,

especially to the bison-hunting groups of the Great Plains (Rathjen, 1973;

Newcomb, 1961). Apaches on the Southern High Plains acquired horses by the

middle 17th century particularly after the Pueblo Revolt of 1680. By the middle of

the 18th century, bands of Comanche began to migrate to the Southern Plains,

displacing the Apache and continuing to dominate this region until the late 19th

century (Worcherster, 1944; Newcomb, 1961).

Spaniards traveling between settlements in present-day New Mexico and

southern Texas occasionally crossed the Llano Estacado, acquiring some

familiarity with the region. Hispanic activity in the region continued after Mexico

gained its independence from Spain in 1821 (Rathjen, 1973) and included

hispanic buffalo hunters (Ciboleros), traders (Comancheros), and sheepherders

(Pastores) traveling between their homes in present-day New Mexico and the

grasslands of the plains.

24

Comancheros continued the trade between aboriginal peoples of the

Southern Plains and the Rio Grande pueblos (Levine, 1991). The traders,

Spanish settlers from New Mexico, dealt with Southern High Plains people for

buffalo meat and hides. In the mid-19th century, raiding by the Comanche

became an economic venture. The high demand by New Mexican ranchers for

cattle and horses created a lucrative market supplied by livestock stolen by the

Comanche and traded to the Comancheros. The Comanchero trade continued

until the United States removed the Comanche from the Southern High Plains in

the 1870s and placed them on a reservation in Oklahoma (Rathjen, 1973).

Pastores were sheepherders from New Mexico who began utilizing the

grassland of the Canadian River Valley and the Southern High Plains for their

sheep during the late 1870s after the Comanche had been removed from the

region, and the bison herds greatly diminished. Their initial use was seasonal as

they moved their flocks back and forth between Texas and New Mexico. In the

1880s, several pastores groups established settlements known as plazas near

the Canadian River. Pastore-built rock fences and corrals were located in a few

sheltered sites within Southern High Plains drainage systems (Hicks and

Johnson, 2000). The pastores largely abandoned sheep herding along the

Canadian River and drainages of the Southern High Plains during the late 1880s

as they faced increasing pressure and competition from free-range cattle

ranching. Some families returned to New Mexico while others remained in the

plazas and engaged in other business such as freighting (Rathjen, 1973).

25

The 19th century was a period of expansion for the United States. A

series of land acquisitions began early in the century with the purchase from

France of Louisiana. Texas, briefly an independent republic during the mid-19th

century, became a part of the United States in 1845. The addition of present-day

California, Arizona, New Mexico, Utah, and Nevada after the Mexican War

extended the United States territory to the Pacific (Hine, 1984). Explorative

expeditions into the new territory ensued.

Several expeditions followed along the Canadian River Valley at the

northern edge of the Southern High Plains but only briefly ventured onto the

upland surface (Rathjen, 1973). Marcy’s 1852 trek seeking the headwaters of

the Red River again only briefly touched onto the Llano Estacado proper as the

party’s travel was restricted to following the water into what is probably Palo Duro

Canyon. All parties considered the interior of the Southern High Plains to be a

dangerous desert, lacking water, with limited forage, no timber, and under

constant threat from aboriginal attack, with little to offer potential settlers

(Rathjen, 1973).

During the Civil War, United States military activity in the west decreased.

Due to increased Comanche raiding during this period, the frontier in Texas

retreated east about 100 miles (Holden, 1930). Not until the late 1870s would

social, technological, and economic factors develop to overcome the perceived

limitations of the Southern High Plains. National developments following the Civil

War contributed to an atmosphere in which settlement of the Southern High

26

Plains appeared a more attractive prospect. With the divisive issue of slavery

settled, a unified nation turned its interest to the new western lands.

The United States military played a crucial role in opening the Southern

High Plains to American and foreign business interests (Morgan, 1971). It was

through military capture of a Comanchero in 1872 that Americans first learned of

well-watered, passable routes across the Llano Estacado, long known to Native

Americans and hispanic hunters and traders.

Hunters, ranchers, and settlers wanting access to the land and resources

of the region saw Native peoples’ presence and resistance to the increasing

insurgence of Americans as an obstruction. The Red River War of 1874-1875

finally ended the Comanche and Kiowa traditional life on the Southern High

Plains (Rathjen, 1973). The military operations increased familiarity with the

resources of the region and helped establish transportation routes. The vast

herds of bison were now the only remaining obstacle to American ranching

interests.

Buffalo hunters exterminated the huge herds that once grazed across the

plains. The commercial buffalo hide market expanded rapidly in the early 1870s.

Hunters in western Kansas sent an initial shipment of 500 hides to a tannery in

England interested in trying the hides for making leather. A few years later,

hunter John W. Mooar convinced a New England tannery to try hides as well.

The success of the tannery ventures led to orders for as many hides as could be

obtained. The tanneries’ successes fueled a fury of commercial killing (Rathjen,

27

1973). By 1873, hunters moved into the Texas Panhandle in spite of the threat

of attack from native groups. Hunters may have been situated near Palo Duro

Canyon in the northern Southern High Plains in 1874 (Rathjen, 1973). The

Causey brothers established a camp in Yellowhouse Draw in Lamb County in

1876 (Holden, 1962a) where they killed over 7,000 buffaloes during the winter

(Crane, 1925). In just a few years, the hunters effectively depleted the buffalo.

By 1878, only a few small groups remained on the Southern High Plains. A few

captured animals kept by ranchers in the early 1880s constituted the remains of

the great bison herds (Holden, 1930).

The cattle industry in Texas was just beginning to develop at the end of

the Texas Revolution. Although conditions during the Civil War imposed a period

of dormancy on the cattle industry in Texas, the end of hostilities brought

circumstances that encouraged rapid expansion of ranching throughout the state.

A number of national and international factors contributed to the growth of the

cattle industry. The country experienced an increased demand for meat. The

Midwest was developing industrially and commercially, creating a larger market

for food (Paul, 1988). The mining industry was growing in the West, drawing an

increasing number of miners. The North experienced shortages of beef (Holden,

1930). New and distant markets were opened by technological developments of

refrigerated shipping (Holden, 1930; Paul, 1988) and better methods of food

processing such as improved canning techniques (Morgan, 1971). High beef

28

prices helped to promote foreign interest in the American ranching industry

beginning in the 1860s (Paul, 1988).

As with the ranching industry, developments associated with the Civil War

and post-war period played a role in shaping settlement on the Southern High

Plains. During the Civil War, a reduced work force contributed to improvement of

mechanical means of production. The resulting increase in mechanization of

farming techniques made possible cultivation of large tracts of land. Due to

limited moisture of the plains environment, each acre of land might be less

productive but farmers were able to farm more acres (Billington and Ridge,

1982), making the prospect of profitable agriculture more feasible. The federal

government provided homestead land grants to encourage settlement and

development of the Great Plains. Land also was given to railroads to encourage

building of rail lines across the country. As both producers and consumers,

settlers provided a market for railroad services.

By the 1870s, ranchers were operating east of the Llano Estacado

escarpment as well as to the west in New Mexico and Colorado. Many ranches

were owned by large cattle companies, some funded by foreign interests.

Charles Goodnight, moving his herds from Colorado, established the JA Ranch

in Palo Duro Canyon in 1876. Others rapidly followed, taking advantage of the

high profits available from free-range fodder (Haley, 1957). Crews of cowboys

and managers, scattered across the region in remote headquarters and line

29

camps, worked the ranches. Supplies came from Fort Griffin about 150 miles to

the east. In 1876, the nearest railroad was at Fort Worth (Hall, 1947).

Also in 1876, the State legislature passed legislation providing for the

exchange of over 3 million acres of Southern High Plains land for a new capitol

building (Haley, 1957). Results of a survey of this land included findings that

sandier portions of the surveyed land were appropriate for grazing while soil with

higher clay content would support grazing or cultivated agriculture. This land

would become the huge XIT Ranch that began moving cattle up Yellowhouse

Canyon in 1886 (Haley, 1957).

One ranch on the Southern High Plains was The Western Land and

Livestock Company’s IOA Ranch, started in 1884 with purchased and leased

land. The IOA was a large ranch with fenced pastures and windmills. It covered

the southern half of Lubbock County for several years, but failed due to high

expenses, drought, and low prices for cattle. The ranch sold off the last of its

cattle in 1896 and all remaining land by 1901 (Holden, 1962a). Stresses that

contributed to the failure of the IOA also were affecting the whole ranching

industry. Another annoyance for ranchers was growing pressure from those

wanting to settle and start farming.

Texas land laws that favored settlers over ranchers were similar to

homestead incentives enacted by the federal government to encourage

settlement and cultivated agriculture in other parts of the Great Plains. All of the

land of the Southern High Plains was public land retained by the state of Texas

30

upon entry into the United States. Part of this public land was given to railroad

companies as an incentive to build rail lines in Texas. The railroads were

required to sell the land within 12 years. The remaining land was sold by the

state according to the current land law. Because the railroad and state lands

were located in alternating sections, the price set by the state for its lands kept

prices low for all the land (Connor, 1962b). By the 1880s, Texas land laws had

changed to assist settlers’ purchases of Texas public land (Gammel, 1890),

making it more difficult for ranches to access large tracts of land through either

purchase or leasing. Low prices for land were one factor contributing to the influx

of settlers onto the Southern High Plains.

Concluding Statement

In the late 19th century, a number of events served to open the Southern

High Plains of Texas to incursion and settlement by Americans. They

encountered elevated, semi-arid grassland inhabited by a plains community of

plants and animals. In this place, for thousands of years, humans subsisted as

hunter-gatherers with relatively low population densities and limited affect on the

natural resources (Johnson and Holliday, 1995). The advance of the United

States frontier in the last half of the 19th century incorporated a new economy

and new perception of the land as commercial commodity. Wildlife that was

once a food source for Native Americans became perceived as competition, a

nuisance, or a predatory threat to settlers’ interests.

31

The Southern High Plains environment, as a component of frontier

development, served to limit the economy and settlement patterns. Settlers

introduced new economies and technologies to the region that, in turn, had a far-

reaching effect on the Southern High Plains environment.

32

CHAPTER IV

REGIONAL HISTORIC CONTEXT

Developments in late 19th century United States lead to conditions in

which perception of the Southern High Plains frontier shifted from that of an

uninhabitable wasteland to a land of potential prosperity. First ranchers and then

settlers seeking to establish small-scale agricultural endeavors began to look

favorably at the region. Most of the vast rangelands gradually came under

cultivation and, by the end of the 19th century, a number of small towns provided

the foundation for further development.

The first settler in the region was Hank Smith who came into possession

of a ranch in Blanco Canyon in 1877 in lieu of payment of a debt owed to him

(Hall, 1947). Smith completed construction of a house at the ranch, known as

the Rock House. He settled there with his family (Hall, 1947) and stocked the

ranch with a small herd of cattle. It was the first small-scale, individually owned

ranch operation in the region (Hall, 1947). Smith also experimented with

agriculture, planting fruit trees and testing different varieties of grain. In 1879, the

government established a post office at the Smith house (Hall, 1947), creating an

official communication link between the Southern High Plains and the rest of the

country. The Smiths ran a small commissary at their home (Spikes and Ellis,

1952). Hank Smith became an important contact for people wanting information

33

about the region. Paris Cox, a Quaker from Indiana, was among those seeking

Smith’s help (Holden, 1962a; Smythe, 1930; Hall, 1947).

Cox had owned a sawmill in Indiana that he traded for a certificate of

unlocated Texas railroad land. After a visit to the state in 1878, Cox had land in

Crosby County surveyed and recorded as his claim. Smith agreed to break out a

small farm plot and plant some crops for Cox who had returned to Indiana. This

field was the first farm established on the Southern High Plains. The farm and a

well Smith and Charles Hawse dug for Cox were a success and Cox, his

immediate family, and three other families settled on the Southern High Plains in

the fall of 1879 (Holden, 1962a) or spring of 1880 (Smythe, 1930).

Cox envisioned an agricultural society formed of his Quaker brethren “who

needed inexpensive homes and farms” where they could practice their faith

without intrusions (Cox, 1972). Cox arranged with the state to promote land

sales among Quakers (Cox, 1972). The resulting community became the little

town of Maryetta, later called Estacado (Fig. 4.1), the first true Anglo settlement

established on the Southern High Plains of Texas (Holden, 1932a, 1962a;

Smythe, 1930; Hall, 1947; Jenkins, 1951, 1986). The earliest families

experienced success and hardship. Some returned to their former homes, but

Cox and his family remained and were soon joined by others. Among those

arriving in 1880 were Harvey Underhill and his family, including his daughter

Rachel Underhill Singer, her husband George, and his young daughter Arena

(Smythe, 1930; Hall, 1947). The Singers traveled by railroad as far as possible,

34

and bought a wagon and horse or mule teams to complete the journey (Debler,

1959). Previously a schoolteacher, Singer became a shopkeeper in Texas,

operating stores in four different locations, all known as Singer’s Store. He

established the first store at Estacado by 1882 (Crosby County Tax Records,

1882; Singer, 1981; Debler, 1959). A letter dated September 30, 1882 from Mr.

W. M. Pearce (1882) to Hank Smith bears the handwritten heading “Singers

Store.”

Figure 4.1. Map showing location of Estacado and Lubbock Lake Landmark in

Lubbock County. Map by author based on General Highway Map of Lubbock County, Texas. State Department of Highways and Public Transportation, 1983.

35

Singer’s satisfaction with the territory seems evident in an 1882 letter to

the Texas Department of Insurance, Statistics, and History (now separated into

the Texas Department of Insurance and the Texas State Library and Archives

Commission) in which he described the land as good for farming or grazing,

supplying adequate feed for stock with some water available on every section

(Spaight, 1882). Soon, however, a competitor, possibly Charles Holmes, arrived

at Estacado and Singer went searching for a new location for his store. Family

members reported he was looking for where the two military trails crossed

(Singer, 1981; Debler, 1959). Two different military trails crossed at a point on

Yellowhouse Draw known as Long Lake. The crossing is an important

component of the history of the Singer Store.

Recorded accounts by contemporary observers are in conflict regarding

aspects such as the appearance and location of the second of Singer’s stores,

and the date when the store was established. One account by cowboy Rollie

Burns, describes the store situated in Yellowhouse Draw, alongside Long Lake

(now the Lubbock Lake Landmark) in 1879 (Holden, 1932a). Burns (1923;

Holden, 1932a) provides a number of different starting dates for the store, but

always described the location as at the headwaters of Yellowhouse, near a lake.

However, land surveyor W. D. Twichell who visited the store in February of 1886

while on his way to survey for the XIT (Gracy, 1945; Truett, 1982) describes the

store location as “…at the fork of the creek” (Truett, 1982:21) where Yellowhouse

Draw and Blackwater Draw converge (now Mackenzie Park) (Gracy, 1945).

36

Singer descendents believe the store was established in 1880 (Connor, 1962a),

but Rachel Singer’s sister, Lina (Perlina) Underhill Sherman, recalled the family

arriving in Estacado in 1880 and the Lubbock store beginning in 1883 (Sherman,

1935). J. B. Mobley (1927) also gives 1883 as the year Singer built the store.

Lubbock County Tax Records show 1883 as the first year the Singers are in

Lubbock County and include assessment on three hundred dollars worth of

goods and merchandise.

In 1932, the Plains Museum Society erected an historic marker within the

boundaries of the Landmark to mark the location of the Singer Store (Holden,

1932b; Fig. 4.2). Rollie Burns, manager of the IOA Ranch in the 1880s provided

the information on the marker and had marked the store location in 1930 (The

Plains Progress, 1930). A replica of that marker now stands in Area 8 of the