Carlos Vierra: His Role & Influence on the Maya Image - in Briggs, Peter "The Maya Image in the...

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

1 -

download

0

Transcript of Carlos Vierra: His Role & Influence on the Maya Image - in Briggs, Peter "The Maya Image in the...

-21

CARLOS VIERRA:MAYA IMAGE

PETER D. HARRISON

INTRODUCTIONThe perceptions by one culture of another are not

static and seldom are objective. The base line of "our''culture is m<-rst often referred to as the Western Worldbecause of the heritage we have received from severalmillennia of'cultural developments from the Mediter-ranean world. Any culture outside of this main streamis regarded as "exotic." Examination of this view throuqhtime and with ref'erence to one specific exotic culture isvery revealing, as it demonstrates how "world condi-tions," current events, econclmic climates, and above all,levels of'scientific research, education, and hence knowl-edge about the exotic culture all exert a strong infiuenceupon the nature of the image that is formed ol thatculture by our s<-rciety. Put in stronger terms, we are notnearly as objective as we might think we are rvhen itcomes to forming opinions and assessments of'other cul-tures. That this egocentrism has been a self-recognizedfeature of the Western World fbr many decades, has notdeterred its indulgence.

Tracing the evolution of the changing image of theMaya culture is the purpose of the exhibition titled TheMaya Image in the Western WorLd. In brief, this study il-lustrates how the earliest images were highly derogatoryand the attitude of Europeans on first contact was oneof exploitation and satisfaction of economic needs, re-gardless of the costs to the Maya. Changes in attitude(or image) occur from the l6th Century through to the20th Century. Some attitudes which the ancien-t Mayareceived from the Western World include fear of theunknown, curiosity, romanticism and admiration, rec-ognition of a complex society, and more currently, sci-entillc interest hoping to learn about mankind fromanother point of'view. At the same time as scientific in-terests attempt to improve understanding of the exotic,there has been a recent development of the "popularimage," characterized by less laudable interests and bythe use of stereotypes and misconceptions about exoticcultures.

Often the prevalent attitudes are the product of prev-alent philosophies in the world, as well as of the stresses

HIS ROLE AND INFLUENCE ON THE

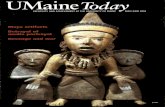

Fig. 1. Carlos Vierra in Studio. Photograph byJesse Nusbaum. Courtesyof the Photo Archives. Mrrseum ol New Mexico.

and strains between nations. Scrutiny of any image ofanother culture must be evaluated in terms of the levelo{'knowledge which was contemporar) with the image.

THE ROLE OF CARLOS VIERRACarlos Vierra was amonff many things, an artist who

lived in Santa Fe, New Mexico, and who was the creatorof a series of images of the Maya through their archi-tecture. To understand the role that Vierra played andthe contribution that he made to the Maya image n'eneed to examine the background of the time in whichhe worked and the nature <-rf the man himself.

Vierra died on December 20, 1937, at age 61, r'ictimof a pneumonia attack that brought a swift and unex-pected demise to lungs already weakened by half a life-time of chronic disease. The obituaries of the day in theSanta Fe l{ew Mexican were effusive in their praise of'hisaccomplishments and expressions of shock at his death.He was described as a sailor, soldier, artist, architect,photographer, aviator and pioneer or even auant gardein several important intellectual areas that had a lastingeffect on the community of Santa Fe. Yet little seems to

22

be remembered of this extraordinary person today' An-thropological interest in his contribution to the qualityof life steins from his creation of six large painted muralsdeoictins Mava cities. These murals were created fbr the

e.iat Pafiuma'-Califbrnia Exposition of 1915 in San Diego,

Ind while they are the subiect of central interest to this

essay. they can only be assFssed in context.Vierra was born on October 3, 1876 in the town of

Moss Landing, near Monterey, Califbrnia. His parents,Cato Vierra a*nd Maria de Fratas were Portuguese fromthe Azores who had immigrated to California' Cato had

been a seaman most of his life and wanted to spare his

own children the hardships which that type of lif'e in-volved. In a large family, Carlos was next to the oldestof six sons. In 1898, after attending school in Monterey,Carlos went to San Francisco where he studied art underGittardo Piazzoni at the Mark Hopkins Institute of Artuntil 190 l. He then left San Francisco by means of an

old wooden ship called the "Roanoke" and heeding thecall of the sea, iailed around the Cape to New York' InNew York City he worked as a marine illustrator andcartoonist for'two years. In 1904 he suffered what was

probably his first nraior atlack oI pneumonia and was

advised ro relocare in a dry climate. Thus. likc manyothers at the time, a condition of weak lungs broughthim to New Mexico. At first he settled in a cabin on thePecos River. However, worsening health forced him tomove into the St. Vincent's Sanitorium in Santa Fe' Thetown and the community became his permanent resi-dence for the remainder of his life. In November of1905, he purchased a photographic studio on the Plaza

in Santa Fe, and added photography to his skills' Thestudio was financially successful and he returned topainting, concentrating on the local landscapes in theSanta F"e region. At thii point he is credited as being thefirst resident artist of the city, and thus hailed as the"founder" of the Santa Fe art colony'

Vierra enlisted in Company F, Ist Regiment of theNew Mexico National Guard, in 1906, his health notpermitting enlistment in the regular armed forces' Hewas an exiellent marksman and held the record for mil-itary rifle marksmanship fbr four years. In 1907 theSchool of American Archaeolow was established in Santa

Fe as an affiliate of'the Archaeological Institute of Amer-ica. Two years later, in 1909, the Museum of New Mexicowas creaied in an agreement with the Territory of Ne-w

Mexico, and Edgar Lee Hewett became Director jointlyof the Museum and the School of American Archaeology'Hewett maintained this Directorship for thirty-seven years'

until his death. Hewett and Vierra were brought to-gether because of the latter's involvement in so manyEo.r.erttt of conservation and aesthetics viewed as im-portant to the future of the Territory. The prec.ise timeind occasion of their meeting is not clear, but by l9l0Vierra had established an informal association with theSchool. This association opened many opportunities forVierra and essentially deiermined the direction of therest of his career. He was brought into contact with artistand archaeologist Kenneth Chapman and notably theHon. Frank Springer, who came to be Vierra's patron

Fig.2. Carlos andAdaVierra, 1932. Photographs by Will Connell. Cour-iesv of the Photo Archives, Museum of New Mexico.

and supporter. In 1910, at age 34., Vierra had begunwhat wai to be a life-long association with one of theforemost archaeological institutions in the nation. Hewas also married that year to Ada Talbert Ogle. In I9l2the associaticln turned into a formal arrangement, andVierra became a staff member of both the Museum ofNew Mexico and the Scho<-rl of American Archaeoiogy.His work now included restoration of the Palace of theGovernors which was scheduled to be torn dou'n. Vierrawas a virulent conservationist with regard to early ar-chitecture and the environment of'Santa Fe. He is cred-ited with spear-heading the salvation of the Palace, theoldest Capitol building in the United States. The workof restoration was supervised by archaeologist and pho-tographerJesse L. Nusbaum, and thus began yet anotherim"poitant-association for Vierra who always seems !9have been in the right place at the right time. In 1912,

his most important work was on the promotion of theso-called "Santa Fe style" of architecture, both in thepreservation of old buildings and the construction oft e* otres in this style. Nusbaum and archaeologist Syl-vanus G. Morley were also active in this movement.

As early as 1910, Hewett had begun an archaeologicalstudy at the ruins of Quiriguii in Guatemala on the Mo-tagua River. By 1912, this project had become associatedwith the plans for the coming Panama-Califbrnia Ex-

t'-

I

.J

position. The excavations were oriented towards a dem-onstration of the high degree of civilization that hadbeen attained in the Americas-a celebration of changein attitude. Excavated pieces from the project were robe exhibited in the Exposition, and copies of the mon-uments which were too large to move were also plannedfor public display. This predilection for collecting andclassifying reflects the dominant intellectual approach ofthe era. It was considered that the collection of artifactsfor museum display was a primary purpose of excava-tion. The time period virtually marks the end of one erain which archaeologists were primarily concerned withdescription and classi{rcation of artifacts and on the brinkof a new interest in chronology. It was a time when thewinds of change were just beginning to mold old con-cepts and introduce new approaches to archaeology.

A report in El Palacio, Vol. l, No. I in November of1913, states that Vierra had begun work on the creationof eight large painted panels of Maya cities for the Ex-position. This was a very large commission for Vierra,and the first major art work he had undertaken. He was37 years old. The original scope of the mural projectwas later reduced to the six panels which were, in fact,produced. The subject matter has been described er-roneously in a number of subsequent reports on theproject, as depicting the selected Maya "Temple" Citiesat their "heyday'." Probably under the influence of Mor-ley, Vierra wisely did not attempt this. Rather he choseto illustrate the sites at a period some time after theirabandonment, which would have quite a varied datespread given the sites chosen. For example, the aban-donment date at Quirigud predates the same events atChich6n ItzAby several hundred years, but this was notknown in 1912. The chosen effect showed some degreeof reconstruction of buildings beyond what was actuallypreserved in 1912, but in a state of decay and partiallyovergrown by bush, though not completely consumedby the jungle.

In 19i4, Vierra was included as a member of the Hew-ett party attending the Quirigud expedition. Reportedlyhe spent five months on this field project, but it is notat all clear which sites, other than Quirigud were visited.The information on this point is not specified in theDirector's reports, nor in the usually thorough com-mentary in El Palacio for the relevant years. Vierra's'svisit to Central America is described whereas "obtainingthe local color," words which likely came from himself.Given the travel routes of the period, by sea from Floridaor New York to Belize, and hence overland to the inre-rior, it seems probable that Vierra did stop over to visitChich6n ltz6 and Uxmal, in Yucatdn, Mexicewhich weretwo of the sites to be painted. It is recorded that someconsiderable time was spent at Quirigud. There is, how-ever, no record of his visiting the sites of Cop6n, Tikal,or Palenque. Journeying to Copdn and Tikal at the timewas a particularly arduous and time-consuming propo-sition, but the lack of such record is not proof that hedid not visit these sites. In November of l9l5 he movedwith his wife to San Diego and remained "for the winter,"undoubtedly to complete the murals and supervise their

Fig. 3. DONALD BEAUREGARD (executed by K. Chapman and C.Vierra), Preaching to the Mays and Aztecs, St. Francis Auditorium,Fine Arts Museum, Santa Fe. Courtesy of the Photo Archives. Mu-seum of New Mexico.

installation. One extant photograph shows Vierra {inish-ing the panel of Palenque on a Gallery above the mainRotunda of the building known then as the CaliforniaBuilding. This magnificent strucrure is now the Museumof Man of Balboa Park.

Throughout the period of preparation of rhe panels,Vierra worked together with Mrs. J. Beman Smith whowas preparing sculptures depicting the lives of the an-cient Maya in bas-relief. Casts of these sculptures wereto be mounted above the Vierra panels. Meanwhile, NewMexico had entered into statehood, and the Second Les-islature of the new state decided to construct an AitMuseum along the same lines as the Exposition building,called the New Mexico Building, which had been de-signed by Jesse Nusbaum. Work on the new Fine ArtsMuseum began in April, 1916, and Vierra is said ro haveexerted a strong influence on the design, although onceagain it was Nusbaum who supervised the work. Defi-nitely known is Vierra's role in creating rhe decorativepanels in the St. Francis Auditorium of the Fine ArtsMuseum. The wall murals were first commissioned tothe artist Donald Beauregard who worked out the orig-inal designs. On Beauregard's death, the work of exe-cution of the murals was turned over to K. Chapmanand Vierra. The content of the three panels worked byVierra is of note: "Columbus at La Rabida," in whichVierra painted a self-portrait as Columbus; "Preachineto the Mayas and Aztecs," which is the only other timehe returned to the theme of the Maya culture; and"Building the Missions of New Mexico," representing thedirection .of his next major interest. However, Vierra'swork on the murals was interrupted by a call to servicefrom the National Guard, in May, 1916. The forays ofPancho Villa against the town of Columbus, New Mexicorequired the Guard's forces. Lieutenant Vierra was sent

24

to train men in small arms use, and while there, he con-structed several crated airplanes used unsuccessfully tolocate Villas forces. Vierra was back at work by .|uly ofthat same year.

The record of Vierra's activities after 1916 becomes alist of art exhibits, both inside and outside New Mexicoand activities related to the preservation of the Missions.Three other events are noteworthy. In 1917 the Schoolof American Archaeology entered into new patents as

the School of American Research, separating itself f romthe expanding museum system. It appears that Vierra'sassociation remained with the museum system, ratherthan the School, in keeping with his activities as an artistand architect from this time forward.

The year of 1918 was a busy time for Vierra. His suiteof fburteen paintings of Spanish Missions were showntogether for the first time in August- This suite remainsone of the accomplishments fbr which he is most oftencited. In the same year he began construction of a hcluseof his own, following his precepts (derived from Puebloand Spanish architecture) of what a house in Santa Fe

should be like. In this endeavor he was sponsored byFrank Springer who paid for the construction, whileVierra supervised the design and construction. He andhis wife lived in this house at 1002 Old Pecos Trail whileit was still under construction. It took three years tocomplete (1918-1920), remains a Santa Fe landmark,and was entered into the Historic Registry in 1979.

In 1929 Vierra flew over Chaco Canyon with OlafEmblem taking photographs of the site from the air.Doing so, he became a pioneer in aerial photography as

an arthaeological technique, having made his flight a

short time before Lindbergh made his reconnaissanceof the Canyon.

On December 20, 1937 Carlos Vierra succumbed to a

last attack of pneumonia, and died leaving an incrediblelegacy of accomplishments to the State of New Mexico.

AN APPRECIATION OF THE MURALSAt the time that Vierra created the six scenes of Maya

cities, there had been a considerable corpus of publi-cations on the subject. W. H. Holmes of the NationalMuseum in Washington hadjust coined the term "Greeksof the New World," and this flowery comparison, andimplication of Classical revivalism, undoubtedly influ-enied Vierra's approach. While the panels were beingprepared, Sylvanus G. Morley was serving both as Cen-iral American Fellow for the School of American Ar-chaeology and also as Research Associate for the CarnegieInstituti,on in Washington. In El Palacio, Vol. 2, No. 3, itis noted that: ". . Morley . . . assisted both Mr. Vierra andMrs. Smith in securing archaeological and historical ver-isimilitude, though without curbing the poetic vision eachhad of the theme."

Publications by Maudslay, Stephens and Catherwood,and from the Peabody Museum at Harvard Universitywere all available. In fact Tozzer's publication of themaps and photos of Tikal appeared in 19l l, a very ti-mely resource for Vierra. The combination of thesesources provided views and maps for almost all of thesites being represented in the series. The modular planpublished by Maudslay closely matches the view takenby Vierra, as does the map of Quirigud in the samevolume (Biologia Centra,liAmericana, Vol. I and II, Plates,1889-1902). Similarly, if the "plan of Uxmal" publishedby Stephens in 1843 is turned upside down, the viewalmost perfectly matches that adopted by Vierra, com-plete with all the same omissions of buildings, such as

ihe Dovecote. However, the Temple of the Dwarf, a ma-jor architectural feature at the site of Uxmal, is presenton Stephen's map but is significantly omitted in Vierra'scomposition. Morley himself had published in 191 I "Ar-chaeological Research at the Ruins of Chich6n ltzi,Yu-cat6n," which may have been the source of the view ofthat site. It is most likely that Maudslay was also thesource for the view of Palenque, reconstructed for Vier-ra's composition from the various plans and elevationsas well as photographs available in the Biologta CentraLiAmericana. The uniformly unusual feature of the Vierrarenditions is that these are not the views of someone whohas drawn from life and ground level, but rather froman imaginary aerial, Iow oblique viewpoint. In addition,structures are shown in a state of semi-reconstruction,unlike the views of Catherwood, who, working with a

camera lucida, rendered the architecture faithfully, as itwas, and from ground view. In further contrast, Cather-wood introduced romantic elements whenever it suitedhim to enhance an image. For example the view of theCastillo at Tulum by Catherwood is rendered with theaddition of high foliage behind the Castillo where in factthe embankment drops off to the sea, and such foliagewas impossible. The addition of vegetation, animals, oratmospheric conditions to enhance the romantic moodis a trademark of Catherwood, a fact which in no way

I

)

n

Fig. 4. CARLOS VIERRA, San Juan Pueblo Mission Courtesy of thePhoto Archives. Museum of New Mexico.

25

*$

t-t,'l':l

i**..:*r,i":-

Fig. 5. CARLOS VIERRA, Ruins of Chich6r? 1tzd. Museum of Man, San Diego.

Fig. 6. CARLOS VIERRA, Ruirc of UxmaL Museum of Man, San Diego.

Fig. 7. CARLOS VIERRA, Ruirn of Quirigud. Museum of Man, San Diego

26

Fig. 8. CARLOS VIERRA, Ruirc of Copdn. Museum of Man, San Diego.

Fig. 9. CARLOS VIERRA, Ruins of Tihal. N{useum of Man, San Diego.

]rwlf:,r1,

S *r*

Fig. 10. CARLOS VIERRA, Ruins of PaLenque. Museum of Man, San Diego.

-----

27

lessens the import of his contribution, but rather indi-cates the difference in attitude, of "image" betrveen him-self and Vierra. The verisimiltude that Morley helpe<1 toachieve shows in the absence of such decorative devices.On the other hand, Vierra did take some liberties. Allthe views except one have long-distance backgrounds,reminiscent of the style of heroic romanticisnitypiliedby Berninghaus, one of Vierra's contemporaries,'of theTaos group. 'fhe one site which does nor employ thelong-distance background is the view of Quirigud, in-terestingly the one site for which Vierra's preience isdocumented. Perhaps he realized that rhis krng obliqueview would not be possible. The remarkable elemenf inVierra's renditions is the desree of accuracy which theycontain relative to the amount of knorvledge available atthe time. The view of Tikal, for example is still impossibletoday, even from a helicopter, as rhe jungle growth doesnot permit so much architecture to be seen at once.

Looking forward to later times it is possible ro examinethe direction that this fbrm of illustraiion took, especiallyin the works of Tatiana Proskouriakoff who was rhe nextto fbllow the work of Vierra. In keeping with the de-velopment of our chaneing image of thi Maya, pros-kouiakoff made the nexr logical step. All elements ofromanticism were eliminated, and the pictures becamepure illustrations, faithful to scale, to reconstruction basedon gathered fact, with no embellishmenrs of foliage, u,ild-life or other such devices. However, even Proskouriakoffdid not always work from life. Her reconsrruction ofTeryple II at Tikal was done from photographs, muchin the same way that Vierra had to work. Pioskouiakoff'slandmark publication, An Album of Maya Architecture waspublished in 1946, but Proskouriakoff did not visir thesite until 1962. 'fhe difference between her work andVierra's is one of style, of'purpose, of imase, influencedby a new interest in objecriviry and belonginr r, an an-alytic period marked by concern for conGxt-and func-tron.

As mentioned earlier, the Exposition murals were anearly work in Vierra's art career, and shor,v somelvhatmore accessibility and clarity than his later landscapesand even architectural renditions. It would seem thatunconsciou_sly he reflected the tenor of his times, beinga person of unusual enersy and receptivity to ideas.

Three of the murals were exhibited temporarily in thePalace of the Governors in Santa Fe in 1914, as theywere ready earlier than the rest. The tll,o murals rvhichare being restored in conjunction with the exhibition TlzeMaya Image in the Western World, have never been exhib-ited in the State of' New Mexico n here they were created.Carlos Vierra's contribution to Maya archaeology was tomark a point in time, a time when illustrarion oi'ancientsites was yielding from romance to science, brideins twoeras in Maya archaeology. Although his contriburion tothis specific field was limited, ir is typical of'the Renais-sance-like range of his abilities, that one contribution ispivotal in the evolution of the Maya Image. Each of theillustrators of Maya architecture menrioned here, Cath-erwood, Vierra, and Proskouiakoff had strengths and

Fig. I 1. FREDERICIK CATHERWOOD, Ruins of Tihat. Courtesy peterD. Harrison.

Fig.- 12. TATIANA PROSKOURIAKOFF, TempLe II, Tihal. peabodyMuseum. Harr ard Lrnir ersiry.

28

weaknesses, but most importantly. they collectively rep-resent a progression in the Maya image. They each havea place in development and refinement of that image.Of the three, Carlos Vierra's role in contributing to arefinement of the Maya image has been the least rec-ognized.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

While conducting research on the life and time of Carlos Vierra a number ofindividuals have been particularly helpful. Without the generous time spent withme in locating the necessary files, photographs and government documents thisessay would not have been possible. I especially wish to thank Phyllis Cohen,Librarian of the Museum of Fine Arts, Museums of New Mexico; Richard Rud-isell, Photographic Archives, Palace of the Governors, Museums of New Mexico;Orlando Romero, Custodian of the History Library, Palace of the Governors;and Al Regensberg, Archivist , State Records Center and Archives. Also I amgrateful to Sandra D'Emilio, Curator of Paintings at the Museum of Fine Artsand Lynn Adkins, Registrar, Museum of New Mexico for their enthusiastic sup-port and interest. At the Maxwell Museum, Katherine Pomonis and Frieda Stew-ar( have been unfailingly supportive.