An analysis of the business environment of China’s Automobile Industry: the Case of Chery...

Transcript of An analysis of the business environment of China’s Automobile Industry: the Case of Chery...

An analysis of the business environment of China’s

Automobile Industry: the Case of Chery Automobile Company

By

Salisu Alhaji Uba

Aberdeen Business School, Aberdeen

Executive Summary

The aim of this report is to evaluate the business environment of

the Chinese automobile industry with particular reference to

Chery automobile company. These gives a brief review of BRICS

(acronyms for Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa).

Then an analysis of the Chinese automobile industry’s external

environment using the PESTEL was conducted. The study further

used Porter’s five forces to compare the industry’s

competitiveness in the global automobile market, also

organisational culture theory are discuss in analysing the

internal environment of Chery automobile with the view of

assessing it. Conclusion and recommendation were given on

strategic option opens to Chery automobile in its drive toward

globalisation.

The study found that the BRICS countries are forces to be

reckoned with in the global automobile sector. It also found that

there are sufficient evidences suggesting that the BRICS economy

with surpass that of the United States and Europe by the year

2050. In relation to Chery, the analysis revealed that it is one

of the leading automaker in China and it rate of globalisation is

very fast. The company’s corporate culture has also worked well.

Based on the analysis conducted it is recommended that among the

strategic options open to Chery in its globalisation pursue is

contract manufacturing, joint venture manufacturing, strategic

alliance and licensing.

Key words: BRICS, China Automobile Industry, Chery Motors.

1.0 Introduction

One of the topical business issues that have captured the

attention of the world today is globalisation. Globalisation,

according to Albrow et al (1990:8), is “all those processes by

which the peoples of the world are incorporated into a single

world society”. In relation to business, the IMF (2002), sees

globalisation as the increasing integration of economies across

the globe as a result of trade and financial flows.

Today, globalisation has played a major role in positioning

global trading blocs in the world economy. In particular,

globalisation has impacted on the origin, strategic direction and

composition of both the BRICS and businesses inside it.

BRICS, as a concept, was first floated in 2001 by Goldman Sachs

as an attempt to forecast global economic trends over the next

half a century (Jim 2001). It was found that BRIC (now BRICS)

would play an important role in shaping the world economy. Two

years later, Goldman Sachs predicted that by the year 2050 BRIC

economies could become a reckoning force in the global economy

(Dominic and Roopa 2003).

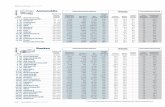

Table 1.1: Economic and Demographic Characteristics of BRICS and

the USA

Country

Population

(in

Millions)

GDP

($

trillion

)

GDP/Capita

($)

GDP Annual

growth rate

(%)

Life expectancy

at birth

(Country rank)

Brazil 198 2.01 10,100 -0.2 123

Russia 141 2.10 15,100 -7.9 163

India 1,156 3.57 3,100 7.6 161

China 1,338 8.75 6,600 9.0 108

USA 307 14.14 46,000 -2.6 49

Source: CIA (2011) cited in Ardichvili et al. (2011)

Table 1.1 below illustrates the economics position of the BRICS

countries (excluding South Africa) in comparison to the United

States (US). The global economic dynamics have since suggested

that come 2050 BRICS, as predicted, will be a force to reckon

with. For example, between the years 2001 to 2010, significant

economic progress was recorded by the BRICS countries.

Collectively these countries accounted for more than 40% of the

global population and about 25% of the global GDP in purchasing

power parity as against 16% in 2000 (BRICS 2012). Of recent the

UN (2013) has predicted that the economy of BRICS is in its way

to overtake that of the long standing Western super powers. The

UN puts it this way:

“By 2020, according to projections developed for this Report, the combined economic

output of three leading developing countries alone—Brazil, China and India—will

surpass the aggregate production of Canada, France, Germany, Italy, the United

Kingdom and the United States”.

Strategically, BRICS is positioned as a platform for dialogue and

cooperation among member countries. Its aim is to promote peace,

security and development in today’s globalised world. BRICS

countries are highly committed toward building a harmonious world

order rooted on long-lasting peace and prosperity. Specifically,

have common interests in four main areas. These areas are i)

desire to reform out of date financial and economic building

block of the world which underestimate or at worse ignores the

rising influence of BRICS, ii) common commitment to principles

and norms of international law, rejection of policies of armed

pressure and violation of the sovereignty of other nations, iii)

common commitment to challenges and problems related to the needs

of modernisation of economy and social life, and iv) mutual

complementary of a wide range of sectors of national economies.

As a result of the marriage between global capital and cheap

labour, brought about by the integration of non-capitalist

countries into the global capitalist system, BRICS have been one

of the main beneficiaries of globalisation (Walden 2014).

However, Walden (2014) further noted, the incorporation of the

BRICS into the global economy has been noticeable by a

multifaceted relationship with the traditional European economies

and the United States, with some of them, particularly China,

developing investment systems that are highly friendly to

overseas capital. This effectively depresses their domestic

demand and thus creates disruptions in the domestic market.

While depression in domestic market is seen by some analyst as a

serious threat to the future of the BRICS, others are more

concern of the differences in political systems and population

dynamics amongst the BRICS countries. All these factors made

Daniel (2013) to conclude as thus:

“The grouping doesn’t make much sense, and any expectation that these countries will

form a new geopolitical bloc is outside of O’Neill’s original intent”.

Whatever the arguments about the future of the BRICS, the fact

remains that at the moment BRICS is a reckoning force in shaping

the global economy.

The aim of this study is to evaluate the business environment of

China’s automobile industry with particular reference to Chery

Automobile Company. The rest of the study is divided into four

sections. The first section presents a critical analysis of the

external environment of the automobile industry in China. This is

followed by a critical discussion of the competitiveness of the

automobile industry in China in the global market environment in

section two. Section three gives a critical analysis of the

internal environment of Chery. Section four presents conclusion

and recommendation.

2.0 Critical analysis of the External Environment of China’s

Automobile Industry

The development of the automobile industry in China is no doubt

shaped by the wider Chinese economy and the relative position of

China in the global economic environment. Since its market

reforms of 1978, the Peoples Republic of China has dramatically

shifted from a centrally planned economy to a market-based

economy. China has now achieved significant economic and social

development. With a Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth of almost

10% yearly, China has succeeded in bringing out more than 500

million Chinese out of poverty (World Bank 2014). With a total

population of about 1.3 billion, the World Bank (2014) confirms

China as the world’s second largest economy.

Figure 1: Auto component Import Breakdown

In spite of being the world’s second largest economy, China still

remains a developing country. Official data, according to the

World Bank (2014), indicates that about 100 million people still

lived below China’s poverty line of RMB 2300 per annum at the end

of 2012. Similarly, China’s global economic dominance has brought

many challenges to it, which the World Bank (2014) identified to

include high inequality amongst its populace, growing rate of

urbanisation, environmental sustainability challenges, and

external imbalances. China’s aging population is also likely to

put more demographic pressure on it.

The automobile industry in China is greatly subsidised and

dominated by the thirteen main state-owned companies (Chen 2001).

Together, these thirteen government-controlled companies

accounted for about 90% of the automotive market (Lin 2001).

Strategically, Lin (2001) further noted, the automobile industry

in China is grouped into two. The first group[1] attempts to

position in the domestic market by forming joint venture with

local companies. The group’s strategy is to maximise their

domestic market share. The second group[2], whose strategy is to

export their finished products to China, take cautious approach

but are largely open to major commitment in the future.

The open-door economic policy of the Chinese government opens the

window for the globalisation of China’s automobile industry.

Today, the interaction of many forces, including market

competition, changes in technology and environmental regulations,

have changed the Chinese automobile industry from local to

global.

Analysis of the environment external to the automobile industry

in China can be expressed by the acronym PESTEL, which stands for

political, economic, social/cultural, technological,

environmental, and legal factors. PESTEL analysis is very helpful

tool for assessing the forces which influence an industry or a

firm in the long run (Janet 2002).

1. a) Political environment:

In order to woo investments, the Chinese government provided

sufficient protection and incentives to automakers. These

incentives include strong support for automobile’s R&D projects,

encouragement for innovation capacities and protection for

intellectual property rights (Zhang and Xiajing 2013). In

addition to these incentives, the automobile industry, as

mentioned above, is highly subsidised. All these measures are

good for the future of the industry. However, the fact that China

does not practice democracy, many question of the sustainability

of these policy measures (VIJ and KAPOOR 2007).

1. b) Economic environment

China’s speedy economic growth has and will continue to impact on

the development of the automobile industry in a number of ways.

Firstly, evidences have shown that the disposable income of the

people have been on the increase, with more people capable to buy

personal cars (China Daily 2006). Secondly, the strong economic

performance of the Chinese economy couple with the country’s

large population has seen many international automakers including

Mercedes Benz, BMW, Volvo, and Peugeot operating in the Chinese

market. The resultant effect is that the indigenous automakers

will learn from technological know-how of these foreign companies

and become competitive in the global auto market in the future.

On the other hand, the continues dominance of the Chinese

automobile industry by international automakers will be at the

disadvantage of the local automakers as they do not have the

technical capacity to compete with these foreign companies (Bao

et al. 2011).

1. c) Social-cultural environment

Cultural differences are a major factor that influences business

practices of a country. With a population of well over 1.3

billion, China has diverse cultures and traditions that

significantly differ from what is obtained in the Western world.

The implication is that international automakers coming to

operate in China must recognise these cultures and work out

strategies of tackling them when investing in China.

The business ethics and organisational behaviour by the Chinese

concept of relationship called “guanxi” and is completely

different from the western concept of relationship. Therefore,

companies can gain competitive advantages by developing their

networks of guanxi. Consequently, many of the multinational

automobile manufacturers are choose joint venture as their entry

mode where it can ease the process in both administrative and

political processes, yet, cultural differences may become the

obstacles from them to handle (Luong 2013).

1. d) Technological environment

As mentioned above, the Chinese government has provided

sufficient incentives to the domestic companies towards

technological development in the automobile industry. This has

led to huge investment by local automakers in terms of production

facilities, product design, and health and safety technology thus

making them independent from the overseas companies (Nadezhda

2011). Similarly, in its drive toward emission control, the

Chinese government is making serious effort in order to ensure

that the gap between the desire for economic development and

environmental protection is reduced to an acceptable level (Gan

2003).

The technology in automobile industry are keeps upgrading, this

is to say automobile makers are now designing a car with

environmental consciousness in order to protect the environment

and they comes up with hybrid cars. Although the government’s

effort toward emission control is laudable, the government is,

nevertheless, faced by a lot of challenges. Such challenges, Gan

(2003) noted, include high cost of producing green cars and the

minimal benefits of producing such cars to the customers as well

as the automakers, among others.

1. e) Environmental factors

China is one of the countries with the highest amount of carbon

emission in the world. Against this background, the government is

encouraging the manufacture of environmentally friendly cars.

While this attempt is laudable, there are other factors which are

worthy of consideration growing phase of China’s automobile

industry. These factors include higher consumption rate of

petroleum, increasing traffic noise in big cities, and lack of

parking space for motorists, among others (Pao and Tsai 2010).

1. f) Legal environment

As discussed above, there are sufficient legislations regulating

and supporting the Chinese automobile industry. However, the

lingering problem is that of implementation. The government have

been accused of being inconsistent and bias in its enforcement of

many of the regulations (Nadezhda 2011). The consequence is that

if this is not corrected, it is likely that China would fail to

meet its projected Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) as potential

investors would not like to come in.

1. G) Market Growth of China’s Automobile Industry.

The market are fuelled by domestic and partly by foreign demand,

china’s rapidly expanding automotive industry has outpaced the

nation’s already impressive GDP growth rates in recent years

(Nadezhda 2011). Domestically, rising incomes and encouragement

from Chinese government for the urban population to obtain

drivers licenses have spurred the demand for passenger vehicles.

The booming passenger vehicle market has led to a soaring demand

for automobile margins components. Internationally, automobile

manufactures faced with decreasing margins and profitability have

sought out more affordable supply chain solutions, looking to

China as a potential source for lower cost automobile components

(CAAM 2010).

3.0 Critical analysis of China’s Automobile industry

competitiveness in the global market

The 2008 economic meltdown has severely hit the global automobile

industry with automakers in United States experiencing

significant decline in sales (Yu and Mu 2010). In sharp contrast,

the China’s automobile industry has continued to grow recording

total sales of about 2.65 million in the first quarter of 2009 as

against 2.2 million recorded by the United States (Yu and Mu

2010).

The Chinese automobile industry is force to be reckoned with in

the global market. There are many tools that can be used to

analyse the relative position of China’s automobile industry in

the global automobile industry. One such tool is the Porter’s

Five Forces Model (Porter 1990).

Figure 2: Porter’s Five Forces Model

Threat of new entrants

One of the reasons why the Chinese automobile industry is

competitive in the global market is the ease at which new comers

enter into the market. Barrier to entry into the market has been

drastically lowered as a result of government polity of

attracting FDI. As discussed earlier, government has put in place

sufficient measures of wooing foreign investors. As at now the

number of automakers in China is around 170 with more are willing

to join.

Apart from the incentives for entry, the cost of investment in

the automobile industry also influences entry. Setting up a

company and putting up all the require logistics to meet the

demand of a large economy as China require huge amount of money

(Brekelmans And Chen 2014).

Furthermore, brand loyalty is also, to a lesser extent, a barrier

to entry in China. Brand names such as Toyota and General Motors

have become a household name in China and are very difficult for

any automaker to enter into the market with the aim of beating

their sales record.

Bargaining Powers of Buyers

Prior to the 1990s the automotive industry in China was highly

protected by high levies and stringent import rations. Then

customers were largely government and its agencies. Although

consumers were government and its agencies, bargaining power did

not exist between the customers and the automakers because prices

were determined by government plans rather than the forces of

demand and supply. The situation changed in the 1990s when demand

for private automobiles began. The industry saw decline in

tariffs and expansion in import quotas (Larry 2005). This trend

couple with the growing number of automakers in the industry give

the customers bargaining powers and choices to make. This

situation is positive to the industry because it has led to the

increase in the sales of automobile as noted above (Peters and

Waterman 1982).

Bargaining Powers of Suppliers

The automobile industry comprises of both the finished products

(for example trucks and cars) and intermediate products (example

parts and components). Suppliers of parts and components have

bargaining power in the Chinese automobile industry because of

the number of automakers.

Most of the parts and components used in the Chinese automobile

industry are imported from abroad. Over the years the parts and

components sub-industry is moving in tandem with automobile

output. At least two reasons have accounted for this trend.

First, the local content rules, and second the importance of

Just-In-time (JIT) production system in the automobile industry.

As at 2004, 35 out of the world largest 50 parts and components

producers were in China in joint venture with local companies

(Larry 2005).

Rivalry among existing firms

The Chinese automobile industry is marked with stiff competition

among automakers. This competitive situation can be attributed to

the presence of three different kinds of enterprises in the

industry, namely; foreign financed, state-owned and private-owned

manufacturers. The competition among these three forms of

enterprises helps to reduce prices for automobile, which is an

advantage China has over the rest of the world.

Similarly, the Chinese automobile industry is large that it

allows multiple automakers to do well without having to take

market share from each other. This might be one of the reasons

why there are more that 170 auto makers in China compared to the

United States that has long standing three local car makers (Rose

2014).

Threats of Substitutes Products

There are many factors that affect the demand for automobile.

These factors include income level, government regulations,

quality of product, and conditions of roads, among others. Demand

is also affected by the availability of substitutes such as

Bicycles, Motorcycles, Rail transport, and Taxis (Oh 2014).

One of the factors that pose the strongest challenge for

automobile is the relative cheapness of these other means of

transport to automobile. Not many people can afford to buy a car

and as such many people in China go for Bicycles and Motorcycles.

This has the effect of lowering the total sales of automobile.

Similarly, people sometimes prefer public transport system

instead of having a car (Luong 2013).

4.0 Critical analysis of the internal environment of Chery

Automobile China

Chery Automobile is a Chinese company that manufactures

automobile whose headquarters is in Wuhu, China. The company,

which is also called “Qirui”, is state-owned founded in 1997. It

main products are SUVs, Minivans and passenger cars. Chery

started production in 1999 and has remain China’s largest

exporter of cars since 2003 (The Global Times 2012). Today, Chery

is not confined to China’s domestic market. It is a global

company selling in many countries including Ukraine, Turkey,

Belarus, South Africa, and Iran. At present Chery is one of the

biggest companies that sell Chinese car brands and is now ranked

among the top 10 automobile companies that are based in China

(Chery 2014). Chery is stepping up its overseas operations and

investments in order to achieve it globalisation strategy of

technical cooperation with foreign companies, car exportations,

foreign assembly plants, and joint venture. Chery is now

synonymous with “well-made, well-appointed cars at the right

time” in some of the world, particularly Australia (Chery 2014).

Nothing made it so global that it’s organisational culture.

Organisational culture is one of the issues that receive

attention when exploring the internal environment of

organisations. Organisational culture, according to Schein

(2001:9):

“is a set of basic assumptions that a group has devised, discovered or developed on

learning how to deal with external adaptation problems and that have worked

sufficiently well to be considered valid and taught to new members as the right way to

perceive, think and feel vis-à-vis these problems”

The idea of organisational culture can be seen from many

perspectives. Beil-Hildebrand (2002) view organisational culture

as total quality management, empowerment, or institutional

excellence. Linstead and Grafton-Small (1992), on the other hand,

considers organisational culture as company or corporate culture.

However organisational culture is viewed, it is nevertheless an

important tool for not only improving productivity and

performance but also relationship at work as Peters and Waterman

(1982: 75) put it thus:

“Without exception, the dominance and coherence of culture proved to be an essential

quality of the excellence of companies. Moreover, the stronger the culture and the more

it was directed toward the marketplace, the less need was there for policy manuals,

organisation charts, or detailed procedures and rules”

Realising this importance, many organisations establish and adopt

organisational culture consistent with their strategic direction.

In the case of Chery, because of the continuous opposition and

barriers it faced over the past 10 years, Gao (2008) noted that

the company developed a kind of “can do” fighting spirit culture

which Mr. Yin, its CEO described as: “Every time we hit a wall,

we just reoriented and moved on”.

Over the years, Chery’s proposals for partnership and joint

venture arrangements were repeatedly turn down by automobile

companies both within and outside China. This worked out well for

because it developed a culture of independence within the

company. This gives it the confidence that it can succeed without

external help. Available statistics shows that in the year 2007,

Chery was fourth in domestic market with a market share of 6.6%

in China’s automobile industry (Snapshot 2008). Similarly, with

overseas sales of 120,000 vehicles in almost 70 countries, Chery

recorded gross revenue of $2.86 billion in the year 2007 (Gao

2008). In 2009 Chery became the leading Chinese auto brand seller

of passenger vehicles (Chery 2014). Inspite of all this

achievement, Chery still has a long way to go in terms of

research and Development (R&D) and product quality compared to

big automobile companies like Ford, Toyota and General Motors

(Xhang and Xiajing 2013).

Similarly, its initial experience of its inability to attract

qualified professionals has made Chery to developed corporate

culture of “learning by doing” (Fairclough 2007). Majority of

Chery’s employees learned from practice. This, according to

Fairclough (2007), underscores the reason why Chery’s CEO states

thus: “we didn’t get to learn from books. We have to learn

everything by doing it”. Today Chery is boasting of having

experienced work force that has the right skills to achieve its

desired targets. While this has worked well for the company, it

is likely to continue this way especially now that its

globalisation drive is ever increasing.

Chery also adopts an organisation culture that centres on the

“merit of hard work and self critique”. The company encourages

employees not to rest on their success and desist from

considering themselves privileged or special because of their

past achievements. This makes Chery a flexible company that is

dynamic and growing. However, this type culture has the tendency

of demotivating senior qualified staff that have vast experience

from joining the company. This is culture is best described by

Fairclough (2007) as thus:

“The corporate culture they spawned is an odd hybrid of Communist state enterprise

and entrepreneurial start-up. Party propaganda posters hang on factory walls. "Know

plain living and hard struggle," one poster exhorts workers, "do not wallow in luxuries

and pleasures." In another part of the plant, bulletin boards display quality-survey data

from J.D. Power & Associates comparing Chery's cars with those of its rivals.”

Chery automobile has adopted an information management system

that integrates its tangible, intangible and human resources

together and calls it “Chery Production System” (CPS). In terms

of tangible resources, CPS actively monitors production

facilities so as to raise efficiency. Intangible resources are

monitored toward creating a corporate culture that is aimed at

optimisation. In relation to human resources, attention is toward

creating efficiency in the flow of operation. The aim of the

integration of these resources is to structure the CPS toward

lean management. However, evidences have shown that Chery has not

been able to implement the management system efficiently. For

example, it takes Chery nearly 120 seconds to couple a car while

its competitors in United States take just about 60 minutes

(Joann and Fara 2007).

5.0 Conclusion and recommendations

The analysis above have shown that BRICS is a force to reckon

with in global business environment and predictions have

indicated that in next ten to fifteen years BRICS will overtake

the leading economic countries of United States and Europe. It is

also evident from the analysis that the automobile industries in

the BRICS countries, particularly China have developed

significantly. Chery automobile company, one of the automobile

companies in China, has raised form a very small company to a

leading automaker in China and the world at large.

While it is clear that China and, in particular Chery have shown

to be visible in the global auto market, there are quite a number

of options open to them to consolidate their position in the

global automobile industry, which include the following

Contract manufacturing. This has the benefits lower

political risk and very quick access to the market. One of

its disadvantages is that in the long run the contractor may

become future competitor.

Joint venture acquisition: this option has the benefit of

bringing high rate of return and more control of operations

but it is likely that conflicts in terms of matters such as

resource allocation and transfer pricing might arise

Wholly owned subsidiary: this leads to greater control and

profit and at the same time allows owners to manage

production and marketing. There is however the risk of

nationalisation

Strategic alliances: this might take the form of licensing

agreement or operation based alliance.

Licensing: in this case appeal is made to small companies

that lack the resources stand. This result in quick access

to the market. There is however the risk of opportunism.

References

ALBROW, M. AND ELIZABETH, K., eds., 1990. Globalization, knowledge and

society. London Sage.

ARDICHVILI ET AL. 2011. Ethical Cultures in Large Business

organisations in Brazil Russia, India and China. Netherlands,

Journal of Business and Ethics, Netherlands, pp. 415-428.

BAO, S. et al., 2011. The Regulation of Migration in a Transition

Economy: China's Hukou System. Contemporary Economic Policy, 29(4), pp.

564-579

BEIL-HILDEBRAND, M. B., 2002. Theorising culture and culture in

context: institutional excellence and control." Nursing Inquiry,

9(4), pp. 257-274.

BREKELMANS, M. and CHEN, L., 2014. China's Automotive

Aftermarket: A Strategic Opportunity. China Business Review, , pp. 2-2

BRICS, 2012. The BRICS Report 2012. New Delhi: Oxford University

Press.

CHAN, L. and DAIM, T., 2012. Exploring the impact of technology

foresight studies on innovation: Case of BRIC

countries. Futures, 44(6), pp. 618-630

CHEN, Q., 2001. Review of China’s Automobile Industrial Development, draft

report. [online]. Place of pub.: Publisher. Available from:

http://www. [Accessed 17 December 2014].

CHERY AUTOMOBILE, 2014. About Chery. [online]. Wuhu, China: Chery

Automobiles. Available from: www.cheryinternational.com [Accessed

10th December 2014].

CHINA DAILY. 2006, Car makers see Surge in First-half China

Sales.

DOMINIC, W. AND ROOPA, P., 2003. Dreaming With BRICs: The Path to 2050,

Global Economics, Paper No. 99.

FAIRCLOUGH, G., 2007. Accelerating Growth: In China, Chery

Automobile Drives an industry shift; Low Costs, High Output

Attract Global Partners; Chrysler’s Leap of Faith. The Wall

Street Journal.

GAN, L., 2001. Globalization of the automobile industry in China:

Dynamics and barriers in the greening of road transportation,

CICERO Working Paper 2001: 09.

GAO, P., 2008. Selling China’s Cars to the World: An Interview with Chery’s CEO.

[Online] Available from: http://www.mckinseyquarterly.com

[Accessed: 12th December 2014].

GRYCZKA, M., 2010. Changing role of BRIC countries in technology

driven international division of labor. Business & Economic

Horizons, 2(2), pp. 89-97

KHANNA, T., 2007. CHINA + INDIA The Power of Two. Harvard business

review, 85(12), pp. 60-69

IMF, 2002. Globalization: Threat or Opportunity? [Online]

Available from:

http://www.imf.org/external/np/exr/ib/2000/041200to.htm#II

[Accessed 2nd December, 2014].

JANET, M., 2002. The international business environment. Bath:

Palgrave Macmillan.

JOANN, M., AND FARA, W., 2007. Ready to buy a Chinese Car?

Forbes, as presented in the EBSCO host database

LARRY, D. Q., 2005. China’s Automobile Industry. [Online]

Available from: www.bm.ust.hk/ContentPages/18112598 [Accessed

11th December 2014].

LUONG, T.A., 2013. Does Learning by Exporting Happen? Evidence

from the Automobile Industry in China. Review of Development

Economics, 17(3), pp. 461-473

LINSTEAD, S. AND GRAFTON-SMALL, R., (1992) On Reading

Organizational Culture Organization Studies 13(3): 331-355.

NADEZHDA, A., 2011. Foreign Investments in the Chinese Automobile

Industry: Analysis of Drivers, Distance Determinants and

Sustainable Trends [Online] Denmark: Research and Talent

http://pure.au.dk/portal/files/39889345/master_thesis_nadezhda_an

astasova_and_martin_nenovski.pdf Accessed [14th December 2014].

OH, S., 2014. Shifting gears: industrial policy and automotive

industry after the 2008 financial crisis. Business & Politics, 16(4),

pp. 641-665

O'NEILL, J. 2001. Building Better Global Economic BRICs, Global

Economics Paper No: 66. Goldman Sachs.

PAO, H. and TSAI, C., 2010. CO2 emissions, energy consumption and

economic growth in BRIC countries. Energy Policy, 38(12), pp. 7850-

7860

PAO, H. and TSAI, C., 2011. Multivariate Granger causality

between CO2 emissions, energy consumption, FDI (foreign direct

investment) and GDP (gross domestic product): Evidence from a

panel of BRIC (Brazil, Russian Federation, India, and China)

countries. Energy, 36(1), pp. 685-693

PETERS, T. J. AND WATERMAN, R. H., 1982. In search of excellence:

lessons from America's best-run companies New York, Harper and Row.

PORTER, M.E., 1990. The Competitive Advantage of Nations. (cover

story). Harvard business review, 68(2), pp. 73-93

PRATER, E., SWAFFORD, P.M. and YELLEPEDDI, S., 2009. Emerging

Economies: Operational Issues in China and India. Journal of Marketing

Channels, 16(2), pp. 169-187

ROSE, Y. 2014. Chinese Dilemma: 170 Auto Makers. [Online] China,

Available from:

http://carpenterstrategytoolbox.com/2013/04/12/chinese-dilemma-

170-auto-makers-wsj/ [Accessed 13th December 2014].

SCHEIN, E. H., 2001. Guia de sobrevivência da cultural

corporativa.Rio de Janeiro: José Olympio,

Snapshots 2008. Market shares by volume, Snapshot international Ltd.

SUNDHARAN, S., 2013. Structure, Growth and performance of IT-BPO

Industry. International Journal of Economics, commerce and management, 1(2),

pp. 1-17

The Global Times (2012) Geely aims to become China’s largest auto

exporters. Available from:

http://www.globaltimes.cn/content/703915.shtml [Accessed 9th

December, 2014].

UN (2013) Human Development Report, Available From:

http://hdr.undp.org/en/2013-report [Accessed: 10th December,

2014].

VIJ, M. and KAPOOR, M.C., 2007. Country Risk Analysis. Journal of

Management Research (09725814), 7(2), pp. 87-102

WALDEN, B., 2014. The BRICS: Challengers to the Global Status Quo.

[online]. New York: The Nation. Available From

http://www.thenation/blog.181481/brics-challengers-global-status-

quo [Accessed 11th December 2014].

WANG, L. et al., 2013. Changing Dynamics of Foreign Direct

Investment in China's Automotive Industry. EMAJ: Emerging Markets

Journal, 3(2), pp. 69-96

WORLD BANK, 2014. China Overview. [Online] Washington DC: World

Bank. Available from:

http://www.worldbank.org/en/country/china/overview [Accessed 8th

December, 2014].

YU, H. AND MU, Y., 2010. China’s Automobile Industry: an Update. EAI

background Brief No. 500. [Online]. Singapore: National

University of Singapore, East Asian Institute. Available from:

www.eainus.edu.sg/BB500.pdf [Accessed 16th December 2014].

ZHANG, J. AND XIAJING, D. 2013 Marketing Strategies for Chery

Automobile Corporation. Canadian Social Science, 9(4), pp. 177-183.

ZHAO, S. et al., 2012. Changing employment relations in China: a comparative

study of the auto and banking industries. Routledge.